Abstract

INTRODUCTION,

This culturally-tailored enrollment effort aims to determine the feasibility of enrolling 5,000 older Latino adults from California into the Brain Health Registries (BHR) over 2.25-years.

METHODS,

This paper describes 1) the development and deployment of culturally-tailored BHR websites and digital ads, in collaboration with a Latino community science partnership board and a marketing company; 2) an interim feasibility analysis of the enrollment efforts and numbers, and participant characteristics (primary aim); as well as 3) an exploration of module completion and a preliminary efficacy evaluation of the culturally-tailored digital efforts compared to BHR’s standard non-culturally-tailored efforts(secondary aim).

RESULTS,

In 12.5 months, 3,603 older Latino adults were enrolled (71% of the total CAL-BHR initiative enrollment goal). Completion of all BHR modules was low (6%).

DISCUSSION,

Targeted ad placement, culturally-tailored enrollment messaging, and culturally-tailored BHR websites increased enrollment of Latino participants in BHR, but did not translate to increased module completion.

Keywords: Brain Health Registry, Recruitment, Digital Marketing, Social Media, Facebook, Enrollment, Engagement, Alzheimer’s, Dementia, Latino, Ethnicity, Diversity

1. Background

In the United States (U.S.), the number of Latino older adults diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) is expected to grow by >800% (approximately 3.5 million affected individuals by 2060)1. Compared to non-Latino White individuals, incidence and prevalence of ADRD is higher in some U.S. Latino ethnic groups2–4,5, 6. The cause of ADRD disparities in older Latino individuals is likely related to differences in environmental and contextual influences, as well as social, psychological, behavioral and health factors7–14.

Our understanding of ADRD disparities is hindered by the failure of many research studies to recruit and retain Latino participants15–21. For example, compared to non-Latino White research participants, Latino participants were less likely to have genetic samples available22, less willing to participate in complex or invasive research23, and less likely to complete brain donations24. Participation of Latino adults in ADRD research is crucial for developing effective interventions9.

Many traditional enrollment strategies have not been successful in recruiting Latino individuals in ADRD research25, 26. The science of recruitment and enrollment in ADRD, especially for typically under-included populations, is still in its infancy. So far, multifaceted efforts which included community outreach components have been most successful in recruiting Latino participants16, 27. In the U.S., a variety of national and local ADRD-related research registries have been developed for efficient prescreening and referral to studies 28, 29. They differ in purpose, format, and target population30–36, but most underrepresent Latino adults32, 33, 35. Evidence about effective registry enrollment strategies for Latino individuals is lacking16, 37. With increasing technology adoption and internet use in the Latino community38, online recruitment offers an avenue to reach potential research participants39. Culturally-tailored online advertising and website improvements might increase enrollment of Latino participants in online registries. Approximately 72% of U.S. Latino individuals use Facebook40, which allows researchers to tailor advertisements using factors like age, location, and language. Facebook has previously been found to be successful in recruiting older adults for health research41 42. However, with a limited amount of research investigating Latino and older adult online recruitment to ADRD-related research and registries, studies are needed to add knowledge.

The UC San Francisco Brain Health Registry (BHR)35 is a public online ADRD-related registry with over 95,000 participants which assesses cognition, function, and health longitudinally. Compared to the U.S. Census data, the BHR underrepresents Latino individuals35,43. To increase enrollment of Latino individuals in BHR we undertook a community-engaged research approach, that included establishing and working closely with a community science partnership board (CSPB) and collaborating with marketing professionals experienced in promoting clinical research participation and marketing for Latino individuals to develop culturally-tailored digital enrollment campaign. The overall goal of this enrollment effort, the California Latino Brain Health Registry (CAL-BHR), was to determine the feasibility of enrolling 5,000 older adults (55+ years) that self-identify as Latino and are from California into BHR over a 2.25-year period. The purpose of this manuscript is 1) to describe the CAL-BHR initiative, including how we developed and implemented the culturally-tailored digital enrollment efforts and 2) to report results from an interim feasibility analysis of the CAL-BHR culturally-tailored digital enrollment efforts after one year. In terms of the interim results, the primary aim was to report on digital marketing efforts, BHR enrollment numbers, demographics characteristics of enrolled participants. In terms of the interim results, the primary aim was to report on digital marketing efforts, BHR enrollment numbers, and demographics characteristics of enrolled participants. The secondary aims were an exploration of BHR module completion and a preliminary evaluation of the efficacy of the culturally-tailored CAL-BHR digital enrollment efforts in enrolling and engaging Latino adults in the BHR compared to BHR’s standard nonculturally-tailored enrollment efforts.

2. Methods

The goal of the CAL-BHR effort was to increase the enrollment of older Latino adults into the BHR. Funding for this initiative, including the culturally-tailored digital advertising, was obtained from the California Department of Public Health Alzheimer’s Disease Program funding from the 2019 California Budget Act [RFA19–10616]. The current study is an interim feasibility analysis of CAL-BHR culturally-tailored digital enrollment efforts after one year.

2.1. The Brain Health Registry experience

The BHR is a public online registry to recruit, screen, and longitudinally monitor participants for aging and cognitive-related research, as well as to refer enrolled participants to other studies35, 44, 45. Anyone over the age of 18 is eligible to participate. BHR includes online consent, self-administered neuropsychological tests (NPTs), self-report questionnaires, and study partner enrollment and questionnaires (see S1 for more details). The questionnaires collect demographic, health, cognitive, and lifestyle data. Participants are asked to complete questionnaires and NPTs every six months. Participants do not receive feedback about their questionnaire replies or NPT results.

2.2. Enrollment efforts

2.2.1. Standard nonculturally-tailored enrollment efforts

For BHR’s standard nonculturally-tailored enrollment efforts, BHR participants are enrolled from different sources. This includes owned, paid, and earned media. Please see Table 1 and Weiner et al. 201835 for a detailed description of the standard BHR enrollment efforts. The overall messaging was nonculturally-tailored and focused on all adults over the age of 18. For these analyses, we refer to participants who enrolled in BHR through those efforts as coming from “standard nonculturally-tailored efforts”.

Table 1.

BHR enrollment effort methods

| Effort | Enrollment effort period | Enrollment effort population focus* | Enrollment effort source | Enrollment effort funding and finances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (nonculturally-tailored) BHR enrollment efforts | BHR inception in 2014 - Sept 16th 2021 | Any adults (18+ years old) | Paid (e.g., digital media, direct mail, traditional) Owned (e.g., BHR website, emails, BHR online networks, BHR press releases) Earned (e.g., news publicity, influencers, word-of mouth) Refer to paper |

The BHR is funded by grants and donations. Both were used to pay for the development of BHR and any BHR enrollment effort-related contents and efforts. |

| Culturally-tailored enrollment efforts (CAL-BHR) | Aug 26th 2020 - Sept 16th 2021 | Latinos age 55+ living in California | Paid digital media: - YouTube - Bing Owned (e.g., culturally-tailored landing pages, simplified BHR enrollment process, revised/culturally-tailored BHR reminder emails) |

Funded by the California Department of Public Health Alzheimer’s Disease Program funding from the 2019 California Budget Act [RFA19–10616]. This grant supported a marketing company to develop the content (ads, landing pages) and payment to digital advertisement platforms. It also provided payment to CSPB members for participating in CSPB meetings. |

Note.

This was the focus of the enrollment effort and not an eligibility criterion. The only BHR eligibility criterion is being 18+ years old. Limiting the focus to CA was a requirement of the grant.

2.2.2. CAL-BHR culturally-tailored enrollment efforts

For the CAL-BHR enrollment efforts (see Table 1), BHR participants are enrolled from different sources, including paid and earned media. The focus of this enrollment effort was on older (55+ years) Latino adults living in California (the focus on California CA was a requirement of the grant), but anyone over the age of 18 was eligible to join the BHR. With the goal to create culturally-tailored BHR enrollment campaigns for older Latino adults (including websites, digital media ads, emails, and engagement on social media), we established a CSPB and also collaborated with marketing professionals experienced in promoting enrollment in clinical research for Latino adults.

2.2.2.1. CSPB Members and Role

Currently the CAL-BHR CSPB has a total of 20 members consisting of seven academics/professional researchers, two Latino marketing/recruitment experts, and 11 Latino community leaders/stakeholders and/or BHR participants. So far, CSPB has met bi-annually and has advised on multiple aspects (e.g., digital advertising themes and messaging, social media and participant communication strategies, Spanish translation).

2.2.2.2. CAL-BHR website improvements

In collaboration with the CSPB and the BHR team, the marketing company created two new culturally-tailored landing pages for the BHR website for two different Latino populations: (1) younger Latino individuals that are more likely to be U.S.-born, and (2) middle-aged Latino individuals that are more likely to be U.S. immigrants. Landing pages are websites, which individuals see in response to clicking on a digital advertisement, where the call to action to enroll is predominant and includes an enrollment form. The two landing pages used culturally-tailored images and themes designed to appeal to the audience in terms of ethnicity, age-group, and language. The landing page designed for middle-aged Latino also blended in some Spanish words/phrases with English messaging. See Supplement S2 and S3 for screenshots of the landing pages. In addition, BHR’s overall enrollment process was simplified to reduce the number of steps needed for sign-up, account, and consent. Aside from culturally-tailored landing pages, participants enrolled through the CAL-BHR effort underwent the same registration process and eligibility criterion (age 18+) and were presented with the same BHR experience in terms of design, questionnaires, and NPTs as participants recruited through other efforts. Emails sent to individuals who did not complete enrollment were revised to include culturally-tailored messaging, similar to the language used in ads and the two landing pages.

2.2.2.3. CAL-BHR digital marketing campaign

A culturally-tailored digital advertising campaign was devised, which included Facebook, YouTube, Google, and Bing which are popular among Latino adults.40 Enrollment messaging and imagery was developed based on a review of the literature, expertise of the marketing team with the Latino population, as well as input from the CSPB. The content was tailored to the Latino population to align with values and beliefs, which included imagery that depicted Latino people and other creative concepts that appealed to the Latino community (see S4 for an example of a Facebook ad and S5 for a more detailed description of the development enrollment messaging). Messaging was limited to English language and English language with some Spanish since BHR was not yet available in Spanish at the time. The digital ads considered age, geography (CA zip codes in metropolitan/suburban areas with large Latino populations), and user interest matching (e.g., Latino music). Digital advertising techniques including “look-alike” audiences (i.e., audiences with the closet match to the seed audience, for example, same music preference)21 and retargeting (i.e., individuals who clicked on the ad get served the retargeting ads)46 were also employed. Each digital ad included a campaign-specific, unique hyperlink, which was created by adding Urchin Tracking Modules to the end of a landing page web address. Utilization of this tracking allowed researchers to identify the ad(s) that led each person to sign-up and/or enroll. Yet, when an individual does not click the link in a digital ad and instead types the BHR web address into a web browser, it is difficult to determine if/which digital ad led an individual to enroll. In these cases, we don’t attribute any advertising platform with the enrollment and instead say the source is other/unknown.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

2.3.1. Advertisement metrics

Facebook, YouTube, Bing, and Google Analytics were used to obtain data on the performance of the advertisement campaign. Metrics included total cost of the marketing campaigns, reach (defined as the number of unique people who were shown digital ads), impressions (defined as the total number of times the ads were displayed to an individual), link clicks (link to a BHR landing page) and the click-through rate (defined as clicks/impressions), as well as measures of ad engagement (reactions, comments, shares, saves) for Facebook ads.

2.3.2. Enrollment metrics

All potential BHR participants must complete a sign-up form first, then create an account, and lastly review and agree to an online informed consent form. We recorded the number of sign-ups (someone who started the enrollment process by providing their email on the sign-up form), the number of enrollments (completing the online consent form), as well as the number of participants who declined to participate or withdrew after enrollment. We used enrollment as an important outcome metric for 2 reasons: 1) BHR in itself is cohort study and 2) refers to other studies. We further recorded entire cost of CAL-BHR, which includes costs for the marketing team and the advertisements on the digital platforms, as well as the cost per enrollment (defined as the total USD spend on digital advertising by the total number of enrolled participants) in $USD.

2.3.3. Participant metrics

After enrollment, participants complete a questionnaire, which asks them to self-report sociodemographic information. This analysis focused on the following variables: age (continuous), gender (male, female, other, Prefer not to say), race (Asian, African American/ Black, Caucasian/White, Native American, Pacific Islander, other, decline to state), ethnicity (Latino, non-Latino, declined to state), endorsement of subjective memory concern (“Are you concerned that you have a memory problem?”), family history of AD/dementia, and education attainment (categorical), and birth region (USA, USA Territory, Outside USA, Don’t know, Prefer not to say). The categorical variable education attainment was converted into a continuous variable called years of education, ranging from 6–20 years. We also created a new race variable which in addition to the categories listed above also contains the category “multiracial” which included individuals who self-identified with more than one race. For the variables gender, ethnicity, and race, we added a category “unknown” if the information was missing. BHR only recently started collecting information about birth region from Latino participants (02/24/2021). A total of 995 participants completed the survey including birth region. We have therefore included an additional category “no data collected”.

2.3.4. BHR module completion metrics

Metrics of module completion were measured during participants’ baseline BHR visit and included whether they completed at least the core BHR module (the first questionnaire in the BHR experience which includes questions about demographic information, family history of AD, memory, mood, health, and medications) (yes, no), completed all baseline BHR modules (yes, no), completed at least one NPT (yes, no), tried an NPT but had technical difficulties (yes, no), and whether they have an enrolled study partner through the BHR Caregiver and Study Partner Portal44. Participants were considered to have an enrolled study partner if their potential study partner completed online informed consent (yes/no) (see S5 for more information about study partner enrollment).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Total frequencies of advertisement metrics were tabulated for Facebook, YouTube, Google, Bing, and across platforms. Summary statistics of participant characteristics were tabulated (for categorical variables: frequencies, percentages; for continuous variables: mean, standard deviation (SD), and range). We compared characteristics of participants who were recruited through culturally-tailored CAL-BHR efforts to characteristics of those recruited through BHR’s standard non culturally-tailored efforts using Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. For all participants self-identifying as Latino enrolled through the culturally-tailored efforts, the frequencies and percentages of the completion metrics are presented and statistically compared to BHR participants self-identifying as Latino not recruited through the standard non culturally-tailored efforts. All analyses were done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

3. Results

3.1. Advertising results

Table 2 provides an overview of the advertising metrics for four online platforms (Facebook, YouTube, Google, Bing). All four were piloted, but YouTube, Google and Bing were discontinued after 1–5 months as the cost per enrollment were deemed as too high and thus, we shifted our efforts to Facebook only which provided us with the most amount of enrollments for our budget. Between August 2020 (26th) and September 2021 (16th), there were a total of 321 Facebook ads which resulted in 8,006,240 impressions and reached 1,237,569 Facebook users. Across all Facebook advertisements, there were 20,538 reactions, 667 shares, 1,829 comments, and 2,136 saves. The total cost for Facebook ads were USD $222,082.54. Across all four digital advertisement platforms, the links were clicked 134,387 times (1.25% click-through-rate).

Table 2.

Advertising results by digital advertisement platform

| YouTube | Bing | Other/ unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Aug 26th 2020 –Sept 16th 2021 | Feb 2021 | Sept 2020 – Jan 2021 | Nov 2020 – Mar 2021 | Aug 26th 2020 – Sept 16th 2021 | Aug 26th 2020-Sept 16th 2021 |

| Cost, US$ | $222,082.54 | $3,426.90 | $25,177.99 | $1,169.13 | N/A | $251,856.56 |

| Impressions | 8,006,240 | 301,837 | 2,402,082 | 17,119 | N/A | 10,727,278 |

| Link clicks | 90,338 | 2,879 | 39,872 | 1,298 | N/A | 134,387 |

| Click-through rate, % | 1.13% | 0.95% | 1.66% | 7.58% | N/A | 1.25% |

| Enrollment | 6,181 | 6 | 341 | 33 | 792 | 7,353 |

3.2. Enrollment

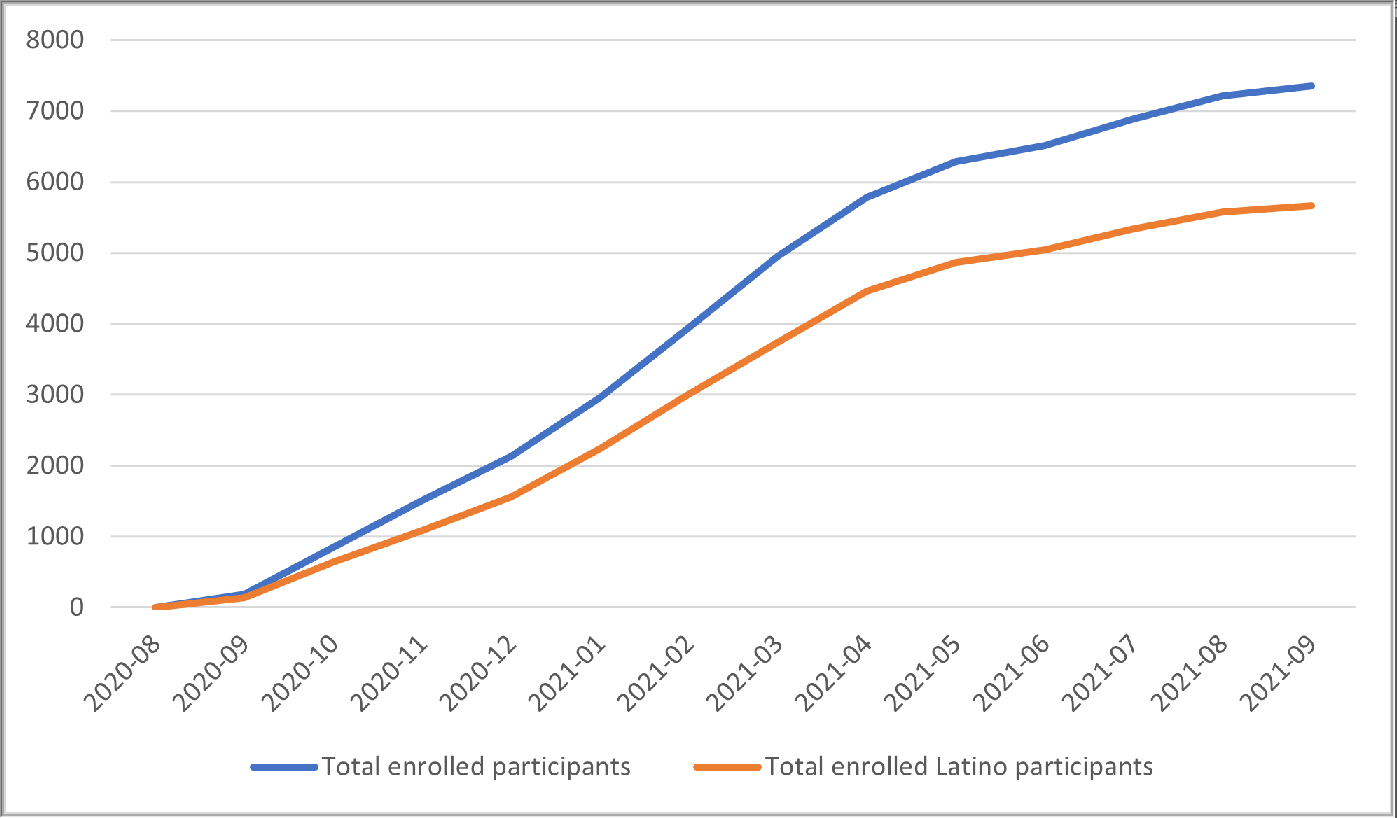

A total of 15,575 individuals coming from CAL-BHR efforts completed BHR’s sign-up form. Of those, six participants had previously enrolled in BHR through another effort, but tried to re-enroll after seeing a digital ad. Of the total 15,575 sign-ups, 7,582 (48.7%) did not proceed to the consent page, 640 (4.1%) declined invitation to enroll after signing up, and 7,353 (47.2%) fully enrolled by consenting to participate in BHR. Of all fully enrolled participants, 77% self-identified as Latino, and 53.6% of those who self-identified as Latino were age 55+. Figure 1 shows the cumulative and monthly enrollment of all CAL-BHR participants and CAL-BHR participants self-identifying as Latino over time. An average of 404.4 (SD=257.77) Latino participants enrolled in BHR per month. A total of 41 (0.6%) participants withdrew from the study after enrolling. Within one year, we were able to recruit 3,603 older adults who self-identify as Latino into the BHR, which is 71.1% of the total enrollment goal of 5,000 older adults who self-identify as Latino within a 2.25-year enrollment period. Overall, the CAL-BHR efforts increased the precent of Latino BHR participants from 6% to 12.2%, which is a 122.7% increase.

Figure 1.

Cumulative number of enrollments over time

The total cost so far was $421,188, which included $119,332 for the marketing agency, $50,000 for websites and other materials and creative, and $251,856 for digital advertising. Across all platforms (Facebook, YouTube, Google, and Bing), the cost per enrollment was USD $34.25. The cost per enrolled Latino participant was USD $44.48 and the cost per enrolled Latino participant 55 years and older was USD $69.90.

3.3. Participants characteristics

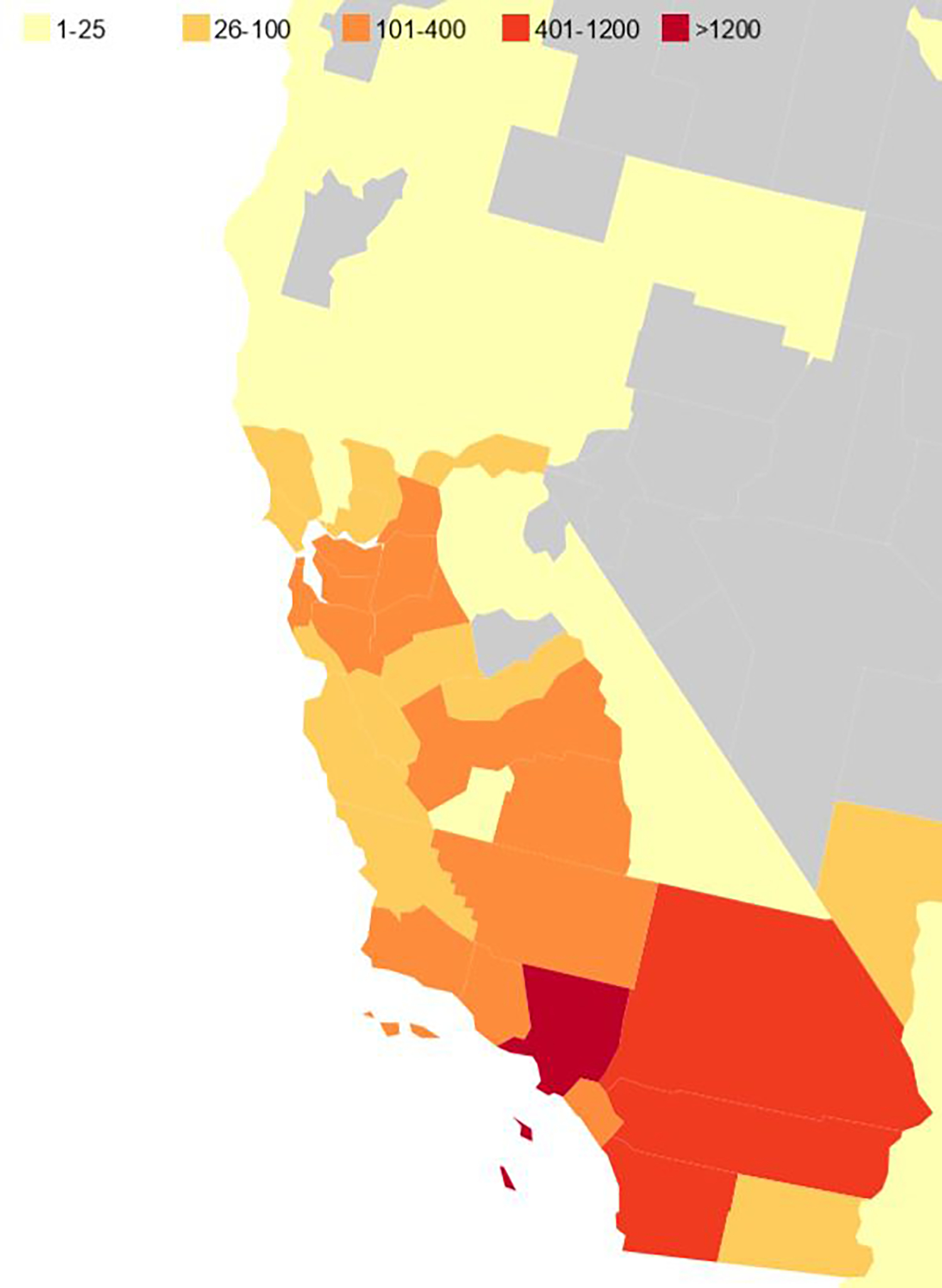

Characteristics of participants by enrollment source (culturally-tailored CAL-BHR efforts versus standard nonculturally-tailored efforts) are presented in Table 3. Compared to those enrolled through standard nonculturally-tailored BHR enrollment efforts, participants recruited through the culturally-tailored efforts reported fewer mean years of education (14.3 vs 15.9), self-identified more as female (79.8% vs 73.3%), Latino (77.0% vs 5.9%), and less as White (44.3% vs 79.1%), reported more memory concerns (55.0% vs 48.5%) and less family history of AD (25.2% vs 28.8%) (all p<.0001). Figure 2 shows an enrollment heatmap of participant residence by county in California. The enrollment campaign was targeted specifically at Latino individuals living in California, yet participants enrolled from across the U.S. with 69.8% coming from California.

Table 3.

Characteristics of enrolled participants

| Enrollment from standard nonculturally-tailored efforts (N=76845) |

Enrollment from CAL-BHR culturally-tailored efforts (N=7353) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M(SD) Range |

57 (14.1) 18–90 |

57.3 (10.7) 18–90 |

<.0001 1 |

| Years education, M(SD) Range |

15.9 (2.47) 6–20 |

14.3 (2.42) 6–20 |

<.0001 1 |

| Gender, n(%) | <.0001 2 | ||

| Male | 19532 (25.4%) | 869 (11.8%) | |

| Female | 56356 (73.3%) | 5871 (79.8%) | |

| Other | 12 (0.0%) | 3 (0.0%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (0.0%) | 6 (0.1%) | |

| Unknown | 933 (1.2%) | 604 (8.2%) | |

| Ethnicity, n(%) | <.0001 2 | ||

| Latino | 4539 (5.9%) | 5662 (77.0%) | |

| Non-Latino | 66566 (86.5%) | 658 (8.9%) | |

| Declined to state | 2229 (2.9%) | 148 (2.0%) | |

| Unknown | 3511 (4.6%) | 885 (12.0%) | |

| Race, n(%) | <.0001 2 | ||

| African American/Black | 3283 (4.3%) | 77 (1.0%) | |

| Asian | 2305 (3.0%) | 54 (0.7%) | |

| Native American | 331 (0.4%) | 392 (5.3%) | |

| Pacific Islander | 120 (0.2%) | 32 (0.4%) | |

| Two or more races | 2703 (3.5%) | 470 (6.4%) | |

| Other | 2473 (3.2%) | 1889 (25.7%) | |

| White | 60883 (79.1%) | 3261 (44.3%) | |

| Declined to state | 1270 (1.7%) | 293 (4.0%) | |

| Unknown | 3510 (4.6%) | 885 (12.0%) | |

| Self-report memory concern, n (%) | 37249 (48.5%) | 4045 (55.0%) | <.0001 2 |

| Report family history of AD, n (%) | 22157 (28.8%) | 1856 (25.2%) | <.0001 2 |

Note.

=based on Mann-Whitney test,

=based on Chi-square test

Figure 2.

Heatmap of enrolled CAL-BHR participants from CA counties

3.4. Characteristics and BHR module completion of Latino Participants

Characteristics and BHR module completion of Latino participants by enrollment source (culturally-tailored CAL-BHR efforts versus standard nonculturally-tailored BHR enrollment efforts) are presented in Table 4. Among Latino participants recruited through the CAL-BHR culturally-tailored efforts (N=5,662), the mean age is 57 (SD=10.2),3,603 (63.6%) were 55 years or older, and 1374 (13.5%) report being born outside the USA or US territory. Most participants identify as female (87.5%) and have an average of 14.3 years (SD=2.41) of education. Among Latino participants who joined through CAL-BHR efforts, at baseline, 99.8% completed at least the core module, 6.0% completed all questionnaires and NPTs, 30% completed at least one NPT, 11.2% tried to complete one NPT but had technical difficulties, and 1.9% have an enrolled study partner. Of all Latino participants enrolled through the CAL-BHR efforts, 93.7% agreed to be contacted about opportunities to enroll in other studies. Latino participants enrolled through the CAL-BHR culturally-tailored efforts were significantly older, reported fewer years of education, self-identified more as female, reported more memory concerns, reported more family history of AD, completed all modules less often, and completed at least one NPT less often compared to Latino participants who were enrolled through BHR’s standard nonculturally-tailored efforts (all p<.0001).

Table 4.

Characteristics and study engagement of enrolled Latino participants

| Latino enrollment from standard nonculturally-tailored efforts (N=4539) |

Latino enrollment from CAL-BHR efforts (N=5662) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M(SD) Range |

49,9 (14.9) 18–90 |

57 (10.2) 18–90 |

<.0001 1 |

| Years education, M(SD) Range |

15.3 (2.64) 6–20 |

14.3 (2.41) 6–20 |

<.0001 1 |

| Gender, n(%) | <.0001 2 | ||

| Male | 1200 (26.4%) | 701 (12.4%) | |

| Female | 3335 (73.5%) | 4953 (87.5%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.0%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.0%) | 5 (0.1%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Race, n(%) | <.0001 2 | ||

| African American/Black | 106 (2.3%) | 44 (0.8%) | |

| Asian | 39 (0.8%) | 24 (0.4%) | |

| Native American | 126 (2.8%) | 376 (6.6%) | |

| Pacific Islander | 19 (0.4%) | 24 (0.4%) | |

| Two or more races | 389 (8.6%) | 406 (7.2%) | |

| Other | 1309 (28.8%) | 1841 (32.5%) | |

| White | 2274 (50.1%) | 2728 (48.2%) | |

| Decline to state | 277 (6.1%) | 219 (3.9%) | |

| Birth region | .0024 2 | ||

| USA | 596 (13.1%) | 2653 (26.0%) | |

| USA Territory | 61 (1.3%) | 183 (1.8%) | |

| Outside USA | 334 (7.4%) | 1374 (13.5%) | |

| Don’t know | 2 (0.0%) | 3 (0.0%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.0%) | 18 (0.2%) | |

| No data collected* | 3544 (78.1%) | 5970 (58.5%) | |

| Self-report memory concern, n(%) | 2461 (54.2%) | 3480 (61.5%) | <.0001 2 |

| Report family history of AD, n(%) | 1263 (27.8%) | 1596 (28.2%) | <.0001 2 |

| Have an enrolled study partner | 268 (5.9%) | 110 (1.9%) | <.0001 2 |

| Completed at least one BHR module | 4531 (99.8%) | 5649 (99.8%) | .48² |

| Completed all BHR modules | 797(17.6%) | 337 (6.0%) | <.0001 2 |

| Completed at least one NPT | 2170 (47.8%) | 1697 (30.0%) | <.0001 2 |

| Had difficult completing NPT | 496 (10.9%) | 636 (11.2%) | .74² |

| Agreed to be contacted about study referrals | 4194 (92.4%) | 5306 (93.7%) | .26² |

Note.

=based on Mann-Whitney test,

=based on Chi-square test

Birth region information was collected starting on 02/24/2021.

4. Discussion

The major findings of this study were: (1) culturally-tailored enrollment websites and Facebook ads created through a community engaged research approach are a feasible and scalable strategy to increase the enrollment of Latino participants into an online ADRD-related research registry; (2) only 47% of those who completed the sign-up form went on to enroll in BHR; (3) this effort mainly recruited female Latino participants and Latino participants with a higher educational attainment (e.g., more than high school); and (4) completion of core BHR module was high (99.8%), but we failed to engage participants sufficiently for them to complete the entire BHR modules. Major challenges of this approach include the need for developing effective strategies to increase enrollment of male Latino participants and Latino participants with a lower education, and to increase the completion of BHR tasks of enrolled participants. Yet, despite challenges, these results show that our culturally-tailored digital enrollment approach has great potential as one strategy to increase enrollment of Latino individuals into online studies. Further investigation is necessary to determine whether this approach could be used to increase enrollment of other ethnocultural groups.

To our knowledge, the CAL-BHR study was the first to demonstrate the feasibility and success of using a digital culturally-tailored enrollment approach informed by a CSPB to increase enrollment of Latino participants in an online ADRD-related research registry. This is supported by enrolling 3,603 older Latino adults in one year, which is 71% of the total CAL-BHR initiative enrollment goal of 5,000 older Latino adults within a 2.25-year initiative period. The feasibility was also supported by enrollment of 5,662 Latino participants of all ages in a little over a year, which resulted in 122.7% increase of Latino participants in the BHR. The representation of Latino participants in the BHR increased from 6% before the efforts to 12.2%, getting closer to being representative of the U.S. population (18.5% identify as Latino according to the U.S. Census47) and to California (39% identify as Latino according to the U.S. Census48). However, when looking at the monthly enrollment over time, we see signs of market saturation, which may mean that we might need more than the allotted time to reach our enrollment goal of 5,000 older Latino participants. The digital efforts of this study targeted Californians and we expect that if this effort is expanded to more states, the representation of Latino participants would increase as well. Our findings add to the emerging evidence of using digital marketing for increasing enrollment in digital studies42, 49–51 and provide further support for the importance of developing culturally-tailored enrollment efforts informed by the community to improve representation of online research registries24, 27, 37, 52–58. Since the digital material can be tailored to other ethnocultural or socioeconomic populations and promoted via social media to adults living in other states, countries, and rural areas, this strategy has high potential for scalability and improving the reach of enrollment efforts. Researchers interested in developing and deploying culturally-tailored digital marketing campaigns should consider allocating resources for developing the digital marketing campaigns and placing digital advertisements in their proposed budget when applying for funding. This includes resources for paying the CSPB members for attending the CSPB meetings, hiring a marketing company with experience with the population of interest, and placing the advertisements on digital platforms.

Despite the overall success, our results show that more than 50% of participants who signed-up for BHR through this effort did not complete the enrollment process. The enrollment process may partially explain the attrition. All potential BHR participants must sign-up, then create an account, and lastly review and agree to an online informed consent form. We sent culturally-tailored reminder emails one and three days after the start of the enrollment process for those who did not complete the process. The efficacy of the culturally-tailored reminder emails will be investigated in future analysis. There is emerging evidence that videos developed with the Latino community, which feature ethnically-concordant community members and study investigators peers, can increase willingness and interest to participate in research59. Therefore, enrollment effort videos which feature members of the CSPB, address concerns and/or barriers to participation, and clarify what it means to participate in BHR are under development and will be added to advertisements and websites.

CAL-BHR efforts resulted in a sample with a majority of female Latino participants and Latino participants with a higher educational attainment (e.g., more than high school). An underrepresentation of male participants exists in the overall BHR cohort35 and has been found in other online ADRD-related registries60, 61. According to the American Community Survey 2019, only 17.6% of Latino adults living in the U.S. have a bachelor’s degree or higher62. This highlights our failure to recruit a representative sample of Latino individuals in terms of educational attainment. In relation to education attainment, Internet use and familiarity might be relevant barriers to enrollment. For example, a Pew Research Center report highlighted that in Latino adults, internet use is among the lowest for those with a high school education or less (67%)63. In addition, lack of Spanish language messaging and study materials might be a barrier among Latino participants with a lower education or years of living in the U.S. BHR has recently launched a Spanish language version of the BHR website, including translation of the informed consent form and all questionnaires and NPTs. A further contributing factor may be that marketing efforts so far have primarily targeted metropolitan areas. Future analyses will determine whether these efforts increase representation of Latinos with lower educational attainment. More future efforts are needed to tailor the enrollment strategies to increase representations of male participants and those with lower educational background to make study results more generalizable.

The success of the enrollment effort was limited by our failure to sufficiently engage Latino participants such that they completed all BHR modules. Even though the CAL-BHR culturally-tailored enrollment effort enhanced the enrollment of Latino participants, only a small percentage completed all BHR modules (all questionnaires and NPTs) or at least one NPT. This is also consistent with a previous analysis of BHR completion data which demonstrate BHR’s failure to engage Latino participants in terms of completion of self-reported questionnaires and NPT modules64. In addition, BHR completion rates are low among all BHR participants35. The non-traditional open-ended structure of the BHR contributes to this problem and this is amplified for Latino participants. This failure leads to missing data, which in turn limits our ability to generalize findings. These results are also similar to in-clinic findings, which showed that studies were less successful in collecting genetic samples from Latino participants22 and brain donation compared to white non-Latino participants24. In addition, only a very small percentage have an enrolled BHR study partner, which is especially relevant in ADRD research since trials typically need to enroll both a participant and their study partner65. One positive aspect is that completion of the core BHR module was high, which includes important demographic, memory, and health data which can be used for referral to other studies and BHR data analysis. Our failure to engage enrolled Latino participants might be related to the fact that the effort’s focus has been on increasing enrollment and not BHR module completion. In addition, the researchers and the design of the study might have hindered module completion. For example, potential explanations include the burden and time commitment of completing all modules in BHR, which have previously been identified as barriers to ADRD-related research participation among Latino individuals66. There is also a long history of providing incentives to participants to improve task completion and retention in Internet-based67–70 studies, as well as in older adults and underrepresented populations71–73. Providing financial incentives to older Latino participants may offset the participation cost/burden, make participants feel understood and respected, and decrease financial stress74. Another contributing factor to low module completion may be that the call to action, theme, and messaging used in enrollment effort material may not adequately address the needs of the community. Efforts are underway to implement and evaluate the use of incentives to improve module completion of underrepresented ethnocultural groups in BHR and the BHR team is working with a company to improve the overall user experience of the registry. In addition, the entire CAL-BHR enrollment effort occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. The increased use of technology during this time and the associated screen fatigue or digital burnout may have contributed to lower BHR module completion.75 Taken together, our study illustrates the differences between enrolling in a registry and completing of research registry modules and a crucial next step is to develop efforts which focus on enhancing BHR module completion. Despite the low module completion among the newly enrolled Latino participants, 93.7% agreed to be contacted about future studies opportunities increasing the number of Latino participants BHR can refer to other AD and aging research studies in the future. However, future studies will need to determine whether those participants will actually enroll in referral studies including in-clinic studies and trials.

4.1. Limitations

Due to the online nature of the marketing campaign and the online BHR design, this study suffers from multiple selection biases, for example, for those with internet access, ability to read and write in English (BHR was not available in Spanish until July 2021), as well as those familiar with scientific research and medical culture. As described above, our registry underrepresents males and individuals with an education attainment less than a high school degree. This impacts the interpretation of the findings and their generalizability. The Latino participants recruited and enrolled in BHR does not represent the characteristics of the overall U.S. Latino population. Enrollment efforts focused on individuals self-identifying as Latino in California, who are mostly of Mexican American/Chicanx heritage76. It remains to be determined whether this effort would be successful in other U.S. Latino subpopulations (e.g., Caribbean, South American). Future analysis will use more fine-grained sociocultural information to inform within-group analyses and better contextualize the current findings (e.g., Latino heritage country/region, language/bilingualism, acculturation). No theoretical framework was used to develop the content of the advertisements. Currently, there is little evidence for theoretical frameworks to improve recruitment of under-included populations in ADRD research10, 16. However, recently intersectional frameworks of research justice and participation have been proposed which could guide future efforts9. The current analyses also did not compare the effectiveness of the different ads used in terms of content and format (e.g., video, photo), as well as the marketing strategies. Future analysis should also include a systematic evaluation of effectiveness of the culturally-tailored efforts compared to the standard nonculturally-tailored efforts. In addition, future efforts need to specifically focus on the researchers and their study design and not exclusively on the low module completion of Latino BHR participants. Efforts will include a Spanish language BHR experience and could include surveying Latino BHR participants about what changes could be made to the study to facilitate BHR module completion. A further investigation could look at whether completion rates of participants vary by enrollment effort platform. It is also unclear whether the same culturally-tailored approach would be feasible for registries which collect blood samples, saliva samples, or imaging data.

4.2. Conclusion

This study provides an evidence-base for the feasibility of culturally-tailored efforts informed by the community for enrolling Latino individuals in a relatively short period of time into an online ADRD research registry that does not translate into an increase in BHR module completion among Latino participants. The CAL-BHR enrollment effort could be regarded as a tool that may facilitate enrollment into a registry, but not as a tool to increase registry module completion. More work is needed to enroll a representative sample of Latino participants in terms of gender and education and to identify ways to increase module completion of enrolled participants. Future work will also evaluate effects of a newly released Spanish-language BHR website and digital ads, as well as long-term module completion of Latino BHR participants recruited through this effort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge all the hard work and insightful comments from all CAL-BHR Community Scientific Partnership Board members including: Alejandra Morlett-Paredes, PhD; Alexandra Tobler, PhD; Barbara Marquez, MPH; Bego Lozano; David X. Marquez, PhD; Elizabeth Rose Mayeda PhD, MPH; Hector González, PhD; Herminia Ramirez, MPH; Jose Antonio Ramirez, MPA; Lindsey Hernandez-Hergsheimer, Monica Rivera Mindt, PhD; Rebecca Rosales; Rey Martinez, MBA; Roxanne Alaniz; Stella de la Pena. We are also grateful to all the BHR participants who enrolled through this effort.

Footnotes

Conflict/funding sources

This study and manuscript is produced by the researchers at the University of California, San Francisco and partner organization, and supported by the California Department of Public Health Alzheimer’s Disease Program funding from the 2019 California Budget Act [RFA19–10616]. The content may not reflect the official views or policies of the State of California.

Dr. Ashford receives support from the National Institutes of Health (made to institution) and declares no potential conflicts of interest.

Monica Camacho, Chengshi Jin, Joseph Eichenbaum, Aaron Ulbricht, Anna Aaronson, Shivam Parmar, Derek Flenniken, Juliet Fockler, Diana Truran, and Alejandra Morlett-Paredes report no potential conflict of interest.

Roxanne Alaniz, Lesley Van De Mortel, Jennefer Sorce work at Alaniz Marketing, Inc. Alaniz Marketing, Inc. is contracted with UCSF to create marketing material and oversee digital and social media campaigns for this study (CAL-BHR) and other academic studies at UCSF and other academic institutions. The payments are made to Alaniz Marketing, Inc. The Alaniz team also discloses to have received consulting fees from the following academic institutions: UCSF, Mt Sinai & George Washington University.

R. Scott Mackin declares to have grants or contracts from the following entities in the past 36 months: R01MH117114, Ro1MH 098062, R01MH101472, R01MH125928. All contracts and grant payments made to university.

Hector M. González declares to have grants or contracts from the following entities in the past 36 months: NIH/NIA R56AG048642 – Institution, RFA 19–10616 – Institution. He also declares to have received payment for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events: International Neuropsychological Association payment made to me.

Elizabeth Rose Mayeda declares to have received support for the present manuscript from NIH grants (payments made to the institution). She also declares to have grants or contracts from the following entities in the past 36 months: National Institute on Aging; payments made to institution; California Department of Public health, payments made to institution; Hellman Fellows Fund; payments made to institution

M. Rivera Mindt declares all payments to institution: Ongoing Research NIH/NIGMS SC3GM141996 (PI: D. Byrd) Project Title: Health Disparities in Alzheimer’s Disease: Intergenerational and Sociocultural Contributors to Dementia Literacy in Immigrant Latinx Families. This study will examine dementia literacy levels and the influence of generation status and sociocultural factors in Latinx immigrant family dyads. Role: Co-Investigator Total Award: $346,500 NIH/NIA R13 AG071313–01 (MPIs: M. Rivera Mindt, R. Turner-II, M. Carrillo) 01/15/21 – 12/31/24 Project Title: Black Male Brain Reserve, Resilience & Alzheimer’s Disease: Life Course Perspectives This three-year conference series will advance health disparities and cognitive aging research via focused and collaborative attention on increasing representation and engagement of Black males in ADRD research. Role: Co-Principal Investigator Total Award: ~$162,000 Genentech Health Equity Innovations 2020 Fund G-89294 01/01/21–12/31/24 (MPIs: M. Rivera Mindt, R. Nosheny & C. Hill) Project Title: Digital Engagement of Black/African American Older Adults in Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Research Using the Brain Health Registry The goal of this project is to improve participation of Black/African American older adults in Alzheimer’s Disease research using novel, innovative community-engaged research techniques. Role: Co-Principal investigator Total Award: $749,500 NIH/NIA R01AG065110 – 01A1 (PI: M. Rivera Mindt) 09/15/20–08/31/25 Project Title: Study of Aging Latinas/os for Understanding Dementia in HIV (S.A.L.U.D.) This is a longitudinal observational study of dementia rate and genetic, neuromedical, and sociocultural risk factors for dementia and changes in brain integrity in older HIV- & HIV+ Latinx adults. Role: Principal investigator Total Award: ~$3,329,120 NIH/NIA 5U19AG024904–14 (PI: M. Weiner) 07/15/20–07/30/22 Project Title: Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) The goal of ADNI is to discover, standardize, and validate biomarkers for AD treatment trials. Dr. Rivera Mindt will Co-Lead the ADNI Diversity Taskforce to advance diversity recruitment & related scientific goals. Role: Subcontract PI/Co-Investigator/Co-Lead of ADNI Diversity Task Force Total Award: $96,040,840 Note. One of many ongoing ADNI grants NIH/NIA R01AG066471–01A1 (MPIs: A. Federman & J.P. Wisnivesky) 04/13/20–04/12/25 Project Title: Natural Language Processing and Automated Speech Recognition to Identify Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment (CI) This is a large (N = 1,000) multi-site observational study of machine learning techniques to identify CI in a diverse sample of older adults. Total Award: $4,278,550 Role: Co-Investigator Alzheimer’s Association Research Grant AARGD-16–446038 07/01/17 – 06/30/20 (PI: Rivera Mindt; PI of subcontract to Mt. Sinai: J. Robinson-Papp) Project Title: Alzheimer’s, Cerebrovascular, & Sociocultural Risk Factors for Dementia in HIV This cross-sectional study aims to understand the relative roles of HIV and aging in neurocognitive impairment of HIV+ Latinx older adults, including genetic, neuroimaging, laboratory, and neurocognitive evaluations. Role: Principal Investigator Total Award: $165,000. Dr. Rivera Mindt declares to have been paid for the following: 2) Panel Moderator: Rivera Mindt, M., Hilsabeck, R. Marquine, M., and Trittschuh, E. (To be Presented 2021, June [delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic]). Hot Topics in Culture and Gender in Clinical Neuropsychology. Workshop to be presented at the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology annual meeting, Chicago, IL. 3) Invited Presentation: Savin, MJ & Rivera Mindt, M.G. (2021, May). Recommendations from the Rez: Guidelines and Future Directions for Neuropsychological Assessment among American Indian/Alaska Natives Adults. UCSD/San Diego VA Clinical Neuropsychology Seminar: Diversity Series in San Diego, CA. 4) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2021, March). The Persistence of U.S. Brain Health Disparities: Moving Forward through Cultural Neuropsychology. Harvard MGH Psychology Assessment Center Seminar; Boston, MA [virtual]; March 18, 2021. 5) Grand Rounds Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2020, March [delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic]). Advancing Brain Health Equity in the 21st Century. University of Washington Department of Neurology Grand Rounds; Seattle, WA.; March 5th, 2020. 6) Keynote Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2020, March). Improving Diagnostic Precision and Health Outcomes within the U.S. Latinx Population through Evidence-Based Neuropsychological Evaluation. Annual Conference of the Pacific Northwest Neuropsychological Society; Seattle, WA.; March 7th, 2020. 7) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2020, January). The Vital Future of Clinical Psychology Through Diversity and Inclusion. Annual Conference of the Council of University Directors of Clinical Psychology; Austin, TX; January 18, 2020. 8) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2019, October). Cultural Neuroscience in Society. National Academy of Sciences/Simons Foundation: The Science & Entertainment Exchange. Woodhull, MA. 9) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2019, April). Cognitive Effects of Chronic Opioid Use, Treatment, and Implications for HIV & Health Disparities. Emory University HIV & Aging Conference. 10) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2019, March). Brain & Cognitive Health in a Sociocultural Framework. Brown University Alpert Medical School, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Grand Rounds. 11) Invited Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2018, November). Neurocognitive diagnosis and care of older Latinx adults with neurocognitive impairment: A Culturally-tailored approach. Paper presentation at the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute/University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health 16th Annual Alzheimer’s Disease Update Conference. 12) Invited Panelist: Rivera Mindt, M. (2018, Oct.). Developing multicultural competencies. Panel presentation at the 38th annual meeting of the National Academy of Neuropsychology, New Orleans, LA. 13) Invited Panelist: Rivera Mindt, M. (2018, Sept.). The Clinical Neuropsychologist: Increasing Diversity & Inclusion. Council of Science Editors, Technica Editorial Services Webinar. The Peer Review Ecosystem: Where Does Diversity & Inclusion Fit In? 2018 [accessed 2018 Oct 9]. https://www.councilscienceeditors.org/resource-library/past-presentationswebinars/past-webinars/2018-webinar-3-the-peer-reviewer-ecosystem-where-does-diversity-inclusion-fit-in/. 14) Invited Colloquium Presentation: Rivera Mindt, M. (2018, Sept.). Cultural neuropsychology: Implications for research and practice. Dept. of Psychology, Ohio University, Athens, OH. Support for attending meetings: NIH and Fordham University; paid to her if I needed to be reimbursed. Dr. Rivera Mindt has held the following roles: National/Regional Leadership 2021 – Present Advisory Board Member, ALL-FTD External Advisory Board 2021 – Present Advisory Board Member, Brown University Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research 2021 – Present Member, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) BOLD Public Health Center of Excellence on Dementia Risk Reduction Expert Panel 2021 – Present Member, CDC/National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) Physical Activity, Tobacco Use, and Alcohol Workgroup 2021 – Present Member, Einstein/Rockefeller/Hunter CFAR (ERC-CFAR) HIV and Mental Health Scientific Working Group 2020 – Present Board Member, Alzheimer’s Association NYC Chapter Board of Directors 2020 – Present Advisory Board Member, Society for Black Neuropsychology 2020 – Present Advisory Board Member, @SocialThatSupports (Chair: Dr. David Washington) 2019 Elections Committee, International Neuropsychological Society 2018 – Present Co-Founder & Co-Chair, Wisdom Workgroup for Indigenous Neuropsychology: A Global Strategy (Wisdom WINGS) 2018 – 2020 Continuing Education (CE) Program Committee, International Neuropsychological Society 2016 – 2020 President-Elect * President * Past-President (Elected Position), Hispanic Neuropsychological Society (HNS) Community 2020 – Present Board of Directors - Treasurer, Harlem Community & Academic Partnership 2019 – Present Older Adults Subcommittee Member, East Harlem Community Health Committee 2014 – 2019 Advisory Board Member, SMART University (NYC-based CBO for HIV+ women) 2013 – 2020 Board of Directors - Secretary, Harlem Community & Academic Partnership.

Dr. Nosheny has received support from NIH (support to institution) for the present manuscript and grant from: NIH (grant to institution), California Department of Public Health (grant to institution) Genentech, Inc. (grant to institution), Alzheimer’s Association (grant to institution). Dr. Nosheny received the following support for attending meetings: MCI 2020 symposium/Mt. Sinai: payment to her.

Michael Weiner, M.D. is a full time Professor for the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Principal Investigator of many projects with the above grant funding.

Financial Disclosures (Outside Income and Relationships): Dr. Weiner has performed Paid Consulting on Advisory Boards for: Alzheon, Inc., Biogen, Cerecin, Dolby Family Ventures, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Nestle/Nestec, and Roche, University of Southern California (USC).

He has provided Consulting to: Baird Equity Capital, BioClinica, Cerecin, Inc., Cytox, Dolby Family Ventures, Duke University, FUJIFILM-Toyama Chemical (Japan), Garfield Weston, Genentech, Guidepoint Global, Indiana University, Japanese Organization for Medical Device Development, Inc. (JOMDD), Nestle/Nestec, NIH, Peerview Internal Medicine, Roche, T3D Therapeutics, University of Southern California (USC), and Vida Ventures.

He has acted as a Speaker/Lecturer to: The Buck Institute for Research on Aging; China Association for Alzheimer’s Disease (CAAD); Japan Society for Dementia Research

He has Traveled with the support of: University of Southern California (USC), NervGen, ASFNR, CTAD Congres.

He holds Stock options with: Alzeca, Alzheon, Inc., and Anven.

Research Support to NCIRE and UCSF with Mike as PI or Co-Investigator:

Dr. Weiner receives support for his research from the following funding sources:

National Institutes of Health (NIH): 5U19AG024904–14; 1R01AG053798–01A1; R01 MH098062; U24 AG057437–01; 1U2CA060426–01; 1R01AG058676–01A1; and 1RF1AG059009–01;

Department of Defense (DOD): W81XWH-15–2-0070; 0W81XWH-12–2-0012; W81XWH-14–1-0462; and W81XWH-13–1-0259;

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): PPRN-1501–26817;

California Department of Public Health (CDPH): 16–10054;

University of Michigan: 18-PAF01312;

Siemens: 444951–54249;

Biogen: 174552;

Hillblom Foundation: 2015-A-011-NET;

Alzheimer’s Association: BHR-16–459161;

The State of California: 18–109929.

He also receives support from Johnson & Johnson, Kevin and Connie Shanahan, GE, VUmc, Australian Catholic University (HBI-BHR), The Stroke Foundation, and the Veterans Administration.

Non-Financial Relationships

Dr. Weiner has served on Advisory Boards (paid and unpaid) for:

Acumen Pharmaceutical, ADNI, Alzheon, Inc., Biogen, Brain Health Registry, Cerecin, Dolby Family Ventures, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., National Institute on Aging (NIA), Nestle/Nestec, PCORI/PPRN, Roche, University of Southern California (USC), NervGen.

He serves on Editorial Boards (unpaid) for:

Alzheimer’s & Dementia, MRI and TMRI.

References

- 1.Wu S, Vega W, Resendez J, Jin H. Latinos & Alzheimer’s disease: New numbers behind the crisis. Projection of the Costs for US Latinos Living with Alzheimer’s Disease through. 2016;2060. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta P, Horton DK, Kasarskis EJ, Tessaro E, Eisenberg MS, Laird S, Iskander J. CDC Grand Rounds: National Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Registry Impact, Challenges, and Future Directions. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2017;66(50):1379–82. Epub 2017/12/22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6650a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang M-X, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, Andrews H, Feng L, Tycko B, Mayeux R. The APOE-∊ 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. Jama. 1998;279(10):751–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y, Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(2):169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haan MN, Miller JW, Aiello AE, Whitmer RA, Jagust WJ, Mungas DM, Allen LH, Green R. Homocysteine, B vitamins, and the incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment: results from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;85(2):511–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewster P, Barnes L, Haan M, Johnson JK, Manly JJ, Nápoles AM, Whitmer RA, Carvajal-Carmona L, Early D, Farias S. Progress and future challenges in aging and diversity research in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15(7):995–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaffe K, Falvey C, Harris TB, Newman A, Satterfield S, Koster A, Ayonayon H, Simonsick E. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: Prospective study. BMJ. 2013;347:f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Croff R, Glover CM, Jackson JD, Resendez J, Perez A, Zuelsdorff M, Green-Harris G, Manly JJ. Traversing the Aging Research and Health Equity Divide: Toward Intersectional Frameworks of Research Justice and Participation. Gerontologist. 2021. Epub 2021/07/30. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnab107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill CV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Anderson NA, Bernard MA. The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research Framework. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):245–54. doi: 10.18865/ed.25.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamar M, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Sachdeva S, Pirzada A, Perreira KM, Rundek T, Gallo LC, Grober E, DeCarli C, Lipton RB. Cardiovascular disease risk factor burden and cognition: Implications of ethnic diversity within the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. PloS one. 2019;14(4):e0215378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner AD, James BD, Capuano AW, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL. Perceived stress and cognitive decline in different cognitive domains in a cohort of older African Americans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RS, Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Weuve J, Evans DA. Factors related to racial differences in late-life level of cognitive function. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(5):517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuelsdorff M, Larson JL, Hunt JF, Kim AJ, Koscik RL, Buckingham WR, Gleason CE, Johnson SC, Asthana S, Rissman RA. The Area Deprivation Index: A novel tool for harmonizable risk assessment in Alzheimer’s disease research. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2020;6(1):e12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canevelli M, Bruno G, Grande G, Quarata F, Raganato R, Remiddi F, Valletta M, Zaccaria V, Vanacore N, Cesari M. Race reporting and disparities in clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2019;101:122–8. Epub 2019/04/05. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, Flowers-Benton S, Block LM, Dilworth-Anderson P, Barnes LL, Shah MN, Zuelsdorff M. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2019;5:751–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fargo KN, Carrillo MC, Weiner MW, Potter WZ, Khachaturian Z. The crisis in recruitment for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s and dementia: An action plan for solutions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2016;12(11):1113–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas MV, Raval PK, Watt JA, Tang-Wai DF. Representation of ethnic groups in dementia trials: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2018;394:107–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franzen S, Smith JE, van den Berg E, Rivera Mindt M, van Bruchem-Visser RL, Abner EL, Schneider LS, Prins ND, Babulal GM, Papma JM. Diversity in Alzheimer’s disease drug trials: The importance of eligibility criteria. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raman R, Quiroz YT, Langford O, Choi J, Ritchie M, Baumgartner M, Rentz D, Aggarwal NT, Aisen P, Sperling R. Disparities by race and ethnicity among adults recruited for a preclinical Alzheimer disease trial. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(7):e2114364–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birkenbihl C, Salimi Y, Domingo-Fernándéz D, Lovestone S, consortium A, Fröhlich H, Hofmann-Apitius M, Initiative JAsDN, Initiative AsDN. Evaluating the Alzheimer’s disease data landscape. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2020;6(1):e12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardach SH, Jicha GA, Karanth S, Zhang X, Abner EL. Genetic sample provision among National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center participants. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019;69:123–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milani SA, Swain M, Otufowora A, Cottler LB, Striley CW. Willingness to participate in health research among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: Does race/ethnicity matter? Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):773–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilbrey AC, Humber MB, Plowey ED, Garcia I, Chennapragada L, Desai K, Rosen A, Askari N, Gallagher-Thompson D. The impact of latino values and cultural beliefs on brain donation: Results of a pilot study to develop culturally appropriate materials and methods to increase rates of brain donation in this under-studied patient group. Clinical Gerontologist. 2018;41(3):237–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong R, Amano T, Lin SY, Zhou Y, Morrow-Howell N. Strategies for the Recruitment and Retention of Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Alzheimer Disease and Dementia Clinical Research. Current Alzheimer research. 2019;16(5):458–71. Epub 2019/03/26. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190321161901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer’s disease research recruitment. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014;28(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massett HA, Mitchell AK, Alley L, Simoneau E, Burke P, Han SH, Gallop-Goodman G, McGowan M. Facilitators, Challenges, and Messaging Strategies for Hispanic/Latino Populations Participating in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Clinical Research: A Literature Review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021(Preprint):1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krysinska K, Sachdev PS, Breitner J, Kivipelto M, Kukull W, Brodaty H. Dementia registries around the globe and their applications: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017;13(9):1031–47. Epub 2017/06/04. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aisen P, Touchon J, Andrieu S, Boada M, Doody R, Nosheny R, Langbaum J, Schneider L, Hendrix S, Wilcock G. Registries and cohorts to accelerate early phase Alzheimer’s trials. A report from the EU/US Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease Task Force. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016;3(2):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders K, Langbaum J, Holt C, Chen W, High N, Langlois C, Sabbagh M, Tariot P. Arizona Alzheimer’s Registry: Strategy and outcomes of a statewide research recruitment registry. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2014;1(2):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong K, Cummings J. Healthybrains. org: From registry to randomization. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016;3(3):123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langbaum JB, Gordon D, Walsh T, Graf H, High N, Nichols JB, Reiman EM, Tariot PN. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry’s Genematch program: Update on progress and lessons learned in helping to accelerate enrollment into Alzheimer’s prevention studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;14(7):P1073. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grill JD, Hoang D, Gillen DL, Cox CG, Gombosev A, Klein K, O’Leary S, Witbracht M, Pierce A. Constructing a local potential participant registry to improve Alzheimer’s disease clinical research recruitment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018;63(3):1055–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson SC, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Clark LR, Mueller KD, Berman SE, Bendlin BB, Engelman CD, Okonkwo OC, Hogan KJ. The Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention: A review of findings and current directions. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2018;10:130–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner MW, Nosheny R, Camacho M, Truran-Sacrey D, Mackin RS, Flenniken D, Ulbricht A, Insel P, Finley S, Fockler J. The Brain Health Registry: An internet-based platform for recruitment, assessment, and longitudinal monitoring of participants for neuroscience studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;14(8):1063–76. Epub 2018/05/15. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cocroft S, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Plassman BL, Chanti-Ketterl M, Edmonds H, Gwyther L, McCart M, MacDonald H, Potter G, Burke JR. Racially diverse participant registries to facilitate the recruitment of African Americans into presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2020;16(8):1107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall LN, Ficker LJ, Chadiha LA, Green CR, Jackson JS, Lichtenberg PA. Promoting retention: African American older adults in a research volunteer registry. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2016;2:2333721416677469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson M Mobile technology and home broadband 2019. Pew Research Center. 2019;2. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Leckenby JD. Internet advertising formats and effectiveness. Center for Interactive Advertising. 2004:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auxier B, Anderson M. Social Media Use in 2021. A majority of Americans say they use YouTube and Facebook, while use of Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok is especially common among adults under 30. Pew Research Center. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 41.King DB, O’Rourke N, DeLongis A. Social media recruitment and online data collection: A beginner’s guide and best practices for accessing low-prevalence and hard-to-reach populations. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne. 2014;55(4):240. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cowie JM, Gurney ME. The use of Facebook advertising to recruit healthy elderly people for a clinical trial: baseline metrics. JMIR research protocols. 2018;7(1):e7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashford MT, Eichenbaum J, Williams T, Fockler J, Camacho MR, Ulbricht A, Flenniken D, Truran D, Mackin RS, Weiner MW, Nosheny RL. Underrepresented Elders in The Brain Health Registry: US Representativeness and Registry Behavior. Clinical Trials and Aging: 12th Conference Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease; San Diego: The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease (JPAD). 2019. p. 45–154. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nosheny RL, Camacho MR, Insel PS, Flenniken D, Fockler J, Truran D, Finley S, Ulbricht A, Maruff P, Yaffe K. Online study partner-reported cognitive decline in the Brain Health Registry. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2018;4:565–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackin RS, Insel PS, Truran D, Finley S, Flenniken D, Nosheny R, Ulbright A, Comacho M, Bickford D, Harel B. Unsupervised online neuropsychological test performance for individuals with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: Results from the Brain Health Registry. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2018;10:573–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunt JF, Vogt NM, Jonaitis EM, Buckingham WR, Koscik RL, Zuelsdorff M, Clark LR, Gleason CE, Yu M, Okonkwo O. Association of Neighborhood Context, Cognitive Decline, and Cortical Change in an Unimpaired Cohort. Neurology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Census Bureau US ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES, 2019 American Community Survet 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables. [Google Scholar]

- 48.U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts California [cited 2022 February 4]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/CA.

- 49.Watson B, Robinson DH, Harker L, Arriola KRJ. The inclusion of African-American study participants in web-based research studies. Journal of medical Internet research. 2016;18(6):e5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wozney L, Turner K, Rose-Davis B, McGrath PJ. Facebook ads to the rescue? Recruiting a hard to reach population into an Internet-based behavioral health intervention trial. Internet interventions. 2019;17:100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bour C, Ahne A, Schmitz S, Perchoux C, Dessenne C, Fagherazzi G. The Use of Social Media for Health Research Purposes: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(5):e25736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brewer LC, Fortuna KL, Jones C, Walker R, Hayes SN, Patten CA, Cooper LA. Back to the future: achieving health equity through health informatics and digital health. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(1):e14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.García AA, Zuñiga JA, Lagon C. A personal touch: The most important strategy for recruiting Latino research participants. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2017;28(4):342–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chadiha LA, Washington OG, Lichtenberg PA, Green CR, Daniels KL, Jackson JS. Building a registry of research volunteers among older urban African Americans: Recruitment processes and outcomes from a community-based partnership. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(suppl_1):S106–S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McHenry JC, Insel KC, Einstein GO, Vidrine AN, Koerner KM, Morrow DG. Recruitment of older adults: success may be in the details. The Gerontologist. 2015;55(5):845–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glover CM, Creel-Bulos C, Patel LM, During SE, Graham KL, Montoya Y, Frick S, Phillips J, Shah RC. Facilitators of research registry enrollment and potential variation by race and gender. Journal of clinical and translational science. 2018;2(4):234–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Epps FR, Skemp L, Specht J. Using culturally informed strategies to enhance recruitment of African Americans in dementia research: A nurse researcher’s experience. Journal of Research Practice. 2015;11(1):M2–M. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gelman CR. Learning from recruitment challenges: Barriers to diagnosis, treatment, and research participation for Latinos with symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of gerontological social work. 2010;53(1):94–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sewell MC, Neugroschl J, Umpierre M, Chin S, Zhu CW, Velasco N, Gonzalez S, Acabá-Berrocal A, Bianchetti L, Silva G. Research Attitudes and Interest Among Elderly Latinxs: The Impact of a Collaborative Video and Community Peers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2021(Preprint):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim YY, Yassi N, Bransby L, Properzi M, Buckley R. The Healthy Brain Project: an online platform for the recruitment, assessment, and monitoring of middle-aged adults at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019;68(3):1211–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langbaum J, High N, Nichols J, Kettenhoven C, Reiman E, Tariot P. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry: A Large Internet-Based Participant Recruitment Registry to Accelerate Referrals to Alzheimer’s-Focused Studies. JPAD-JOURNAL OF PREVENTION OF ALZHEIMERS DISEASE. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.U.S. Census Bureau. EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, 2019 American Community Survet 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables.

- 63.Perrin A DM, Duggan M. Americans’ Internet Access: 2000–2015. Pew Research Center, Internet & Technology, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ashford MT, Eichenbaum J, Williams T, Camacho MR, Fockler J, Ulbricht A, Flenniken D, Truran D, Mackin RS, Weiner MW. Effects of sex, race, ethnicity, and education on online aging research participation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2020;6(1):e12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Largent EA, Karlawish J, Grill JD. Study partners: essential collaborators in discovering treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2018;10(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Areán P. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scheuer L, Dobell-Feder D, Kaduthodil J, Ressler K, Germine L. A randomized study of engagement strategies for assessing cognitive control and emotion perception in the Partners Healthcare Biobank. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown JA, Serrato CA, Hugh M, Kanter MH, Spritzer KL, Hays RD. Effect of a post-paid incentive on response rates to a web-based survey. Survey Practice. 2016;9(1). [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Gelder MM, Vlenterie R, IntHout J, Engelen LJ, Vrieling A, van de Belt TH. Most response-inducing strategies do not increase participation in observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2018;99:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Kalaitzaki E, White IR, McCambridge J, Thompson SG, Wallace P, Godfrey C. Impact and costs of incentives to reduce attrition in online trials: two randomized controlled trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(1):e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doerfling P, Kopec JA, Liang MH, Esdaile JM. The effect of cash lottery on response rates to an online health survey among members of the Canadian Association of Retired Persons: a randomized experiment. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2010;101(3):251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dykema J, Stevenson J, Kniss C, Kvale K, González K, Cautley E. Use of monetary and nonmonetary incentives to increase response rates among African Americans in the Wisconsin pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Maternal and child health journal. 2012;16(4):785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu ST, Geidenberger C. Comparing incentives to increase response rates among African Americans in the Ohio pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(4):527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Areán PA, Gallagher-Thompson D. Issues and recommendations for the recruitment and retention of older ethnic minority adults into clinical research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma MK, Anand N, Ahuja S, Thakur PC, Mondal I, Singh P, Kohli T, Venkateshan S. Digital burnout: COVID-19 lockdown mediates excessive technology use stress. World Social Psychiatry. 2020;2(2):171. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Demographic and Economic Profiles of Hispanics by State and County, 2014. Pew Research Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.