Abstract

Introduction and importance

Femoral shaft fracture is one of the most frequent injuries encountered by an orthopedic surgeon. Surgical treatment is commonly needed. Intramedullary nailing remains the gold-standard in surgical treatment of femoral shaft fracture. One of the constant dilemmas in intramedullary nailing is whether to use a static or dynamic locking screw for treating femoral shaft fractures.

Case presentation

We reported three cases of simple femoral shaft fracture and surgically fixed with primary dynamic interlocking nail. Closed reduction with reamed nail was performed in 2 cases, and mini open reduction with un-reamed nail was performed to the other one. Early weight bearing was instructed at day 1 post-operative. Mean follow-up period was 12.6 months. A solid bony union was achieved by all patients, and no complications were observed at the final follow up.

Clinical discussion

Intramedullary nailing can be made static or dynamic. It is thought that in static mode of the intramedullary nailing, the axial weight is transferred through the locking screws rather than the fracture site, thus altering the callus formation and delaying fracture healing. A prompt dynamization of the fragments allows the contact of both fragments during mobilization and promotes early callus formation.

Conclusion

Primary dynamic interlocking nail is an effective option for surgical treatment in simple or short oblique femoral shaft fracture.

Keywords: Femur, Nail, Femoral shaft, Intramedullary nail, Dynamic, Dynamization

Highlights

-

•

Constant dilemma in choosing static or dynamic locking intramedullary nail

-

•

Static locking is believed to give a stable fixation, but altering the callus formation and delaying fracture healing

-

•

A prompt dynamization of the fragments by early weight bearing promoted the formation of periosteal callus

-

•

There is no adverse effect with the tensional rigidity and axial strength by using only one distal locking screw of IMN

1. Introduction

Femur is one of the most frequently fractured bone, and one of the load-bearing bones, in the body that requires surgical treatment, such as fixation. Femoral shaft fractures (FSF) are one of the most common injuries encountered by orthopedic surgeons [1]. They commonly result from high-energy trauma in the young adults, and lower energy trauma in elderly patients, with motor vehicle collision (MVC) is one of the most common mechanism causing this injury. Femoral shaft fractures can be treated with non-operative or operative management, depending on many factors, such as age of the patient, open or closed fracture, level of comminution, and associated injuries.

In orthopedic surgery, intramedullary nailing (IMN) has become the gold-standard for surgical treatment in physiologically stable patients. Early healing, long-term functional recovery, without sequalae or complications is the goal of fixation. Excellent outcomes of FSF are reported in modern-day treatment with 90–100 % of union rates [2], [3]. Along with the technological advancement of the implants and surgical techniques, the methods of IMN fixation have also developed, including antegrade and retrograde entry point, reamed and un-reamed nail, static and dynamic locked nail. The option of using static or dynamic type of nailing is a constant dilemma and becomes a field of debates in modern orthopedic surgery, because the indication is constantly expanding [4]. Both static and dynamic interlocking nailing is in current practice for transverse shaft fractures, variable results have been reported in various studies [5]. The concerns have been raised on static interlocking nail, which might decrease load across the fracture site and interfere the fracture healing, due to the effect of stress shielding [6].

The mode of locking of IMN is subject to surgeons' personal preference because the clinical evidence and standard protocols are lacking. In this study we reported our results and outcomes of femoral shaft fracture treated with primary dynamic locking type of IMN. The work has been reported in line with the updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) 2020 criteria [7].

2. Presentation of case

We reported 3 patients who sustained a closed femoral shaft fracture from our institution in 2021 (Table 1). The mechanism of injury was motor vehicle accidents (MVA) in all cases. All fractures were classified as 32A3 using the AO Foundation/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO-OTA) classification (Fig. 1). The mean age was 33 years-old (range, 21–57 years-old) and the mean follow-up period was 12.6 months (range, 9–17 months) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient and injury characteristics.

| Patient | Sex | Age (year-old) | Mechanism | Fracture type | AO-OTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 21 | MVA | Closed | 32A3 |

| 2 | Male | 57 | MVA | Closed | 32A3 |

| 3 | Male | 21 | MVA | Closed | 32A3 |

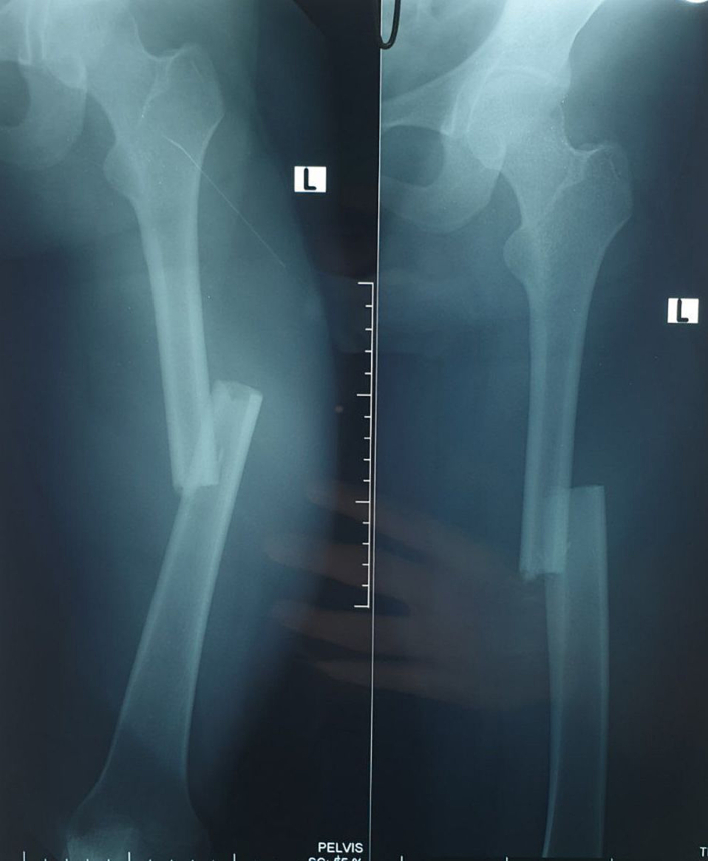

Fig. 1.

Initial radiographic examination showed a simple fracture at the midshaft of femur.

Table 2.

Surgical techniques and outcomes.

| Patient | Reduction | Reamed/unreamed | Union time (months) | Follow-up period (months) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Closed | Reamed | 6 | 12 | None |

| 2 | Mini open | Unreamed | 9 | 17 | None |

| 3 | Closed | Reamed | 6 | 9 | None |

They were in stable condition on hospital admission, and underwent surgical fixation by the first author for their FSF with antegrade intramedullary nailing (IMN). All patients were positioned supine on a fracture traction table under image intensifier, with the affected limb was attached to the traction device to aid the fracture reduction. Closed reduction was done in 2 patients and fixed with reamed IMN. Mini open reduction and un-reamed IMN fixation was done in another patient due to technical problem with the guidewire, so we could not perform the reaming process. The quality of reduction was evaluated with fluoroscope before inserting the IMN. After a good reduction was confirmed and achieved, reaming of the femoral canal was performed until 1 mm above the desired size of the IMN. All nails used in our case had two proximal inter-locking screw holes and three distal inter-locking screw holes. On the distal holes, two holes were designed for static and the other one hole was oval shaped for dynamic locking, allowing motion between the hole and the screw (Fig. 2). In all our cases, 2 static locking screws were inserted on the proximal hole with the aid of proximal guide and a dynamic locking screw was inserted on the distal hole of the nail with freehand technique (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Distal part of the nail, showing 3 holes with an oval shaped hole for dynamic locking.

Fig. 3.

All cases fixed with primary dynamic locking nail, with only 1 screw inserted at the distal hole of the nail, thus allowing cortical bony contact while mobilization.

Early range of motion exercise and weight bearing were instructed to all patients at post-operative day one to prevent stiffness and allow compression of the fragments, thus promoting early callus formation. All surgical wounds were healed uneventfully and stitches were removed in the clinic 2 weeks post-operative. Follow-up radiographs were taken at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after surgery. Union was seen in 2 patients with reamed IMN at 6 months follow-up and at 9 months follow-up in patient with un-reamed IMN (Fig. 4). Excellent functional outcome was achieved by all patients without any complications at the final follow-up. They have returned to their pre-injured level of activity without any limitations.

Fig. 4.

Solid bony union was achieved without shortening and malrotation.

3. Discussion

Being the strongest bone in the body, the amount needed to break the femur bone is usually high [1]. Closed intramedullary nailing (IMN) is the gold-standard of surgical management in femoral shaft fracture (FSF). The advantages of closed IMN include low infection rate, less blood-loss, less complication with hip and knee joint stiffness, and early mobilization [8]. In all of our cases, no infection nor hip and knee joint stiffness were observed, and a good reduction with cortical bony contact was achieved, so early mobilization and weight bearing was instructed to provide early callus formation. Despite the nail taking the entire body weight, immediate weight bearing remains the goal of treatment. Pillai [9] in his study concluded that early protected weight bearing after a closed IMN in treating a transverse FSF is an excellent option. The IMN can be a load sharing device if cortical bony contact is achieved. In case of comminuted fractures with large gap between fragments, the IMN construct immediately becomes load bearing device. But even in comminuted fracture patterns, early weight bearing with IMN has been shown to be safe [10].

Intramedullary nailing (IMN) can be made static or dynamic. In the past, static nailing can be achieved by placing locking screws into distal and proximal hole of the IMN. The weight will be transferred to the IMN instead of the bone and no contact of the fragments. On the other hand, dynamic or dynamization can be achieved by not inserting the screws or inserting the locking screws only on one side of the IMN, leaving the other side empty, hence allowing the fracture fragments to contact. In the recent design of interlocking IMN, the placement of the interlocking screw into an oval hole can provide the dynamization. Before the advent of interlocking nailing, dynamic IMN was used. But it failed to provide adequate axial and rotational stability, hence associated with malrotation and also shortening of the affected limb. With the discovered of interlocking IMN with an oval screw hole, those problems were resolved [11]. Despite the good part of static interlocking IMN, it is thought that in static mode the IMN becomes the load bearing rather than the load sharing device, and the axial weight is transferred through the locking screws rather than the fracture site, thus altering the callus formation and delaying fracture healing [6].

All cases included in our study were a simple transverse fracture, so we fixed them with a dynamic locking of IMN, allowing the contact of both fragments during mobilization in order to avoid interfragmentary gaps. A prompt dynamization of the fragments by early weight bearing promoted the formation of periosteal callus [11]. There is no adverse effect with the tensional rigidity and axial strength by using only one distal locking screw of IMN. Previous series had achieved fracture healing in all cases, even in fractures with significant comminution [12]. Somani et al. [13] in their comparative study, consist of 60 patients, showed that dynamic IMN assembly is safe in treating closed or type 1 open tibial fractures with simple or limited comminution fracture patterns. His study showed similar results with meta-analysis study conducted by Loh et al. [14], which concluded that primary dynamic IMN fixation demonstrated shorter times to bony union and less complications. In this study, all of our cases were a simple transverse fracture. By using primary dynamic IMN, bony contact is allowed and early callus formation are expected without the afraid of malrotation or shortening.

We performed reamed IMN in 2 of our cases. In antegrade nailing, reaming was performed after the fracture is reduced and the guide wire is inserted into the femoral canal from the proximal fragment to the distal fragment, confirmed by fluoroscopy. The reamer was inserted from the smaller size and gradually increased until 1 size bigger than the desired implant size. Solid bony union was achieved in all cases in our series even though one case with un-reamed IMN was slightly delayed. This finding is in-line with meta-analysis conducted by Li et al. [15] and Huang et al. [16], in their study they found that reamed IMN is associated with shorter union time and lower rates of delayed-union, nonunion, and reoperation. At the final follow-up, we found no complication such as residual pain, shortening, malrotation, and joint stiffness. The limitation of this study is a limited number of cases because we studied only in 1-year period.

4. Conclusion

Despite all the controversy over the timing and utility of dynamization in treating femoral shaft fracture with intramedullary nailing, the present series indicates that primary dynamic interlocking nail is effective option for surgical treatment of simple or short oblique femoral shaft fracture, without compromising the strength of the nail construct.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the authors institution.

Funding

N/A.

Guarantor

Sigit Wedhanto.

Research registration number

-

1.

Name of the registry: N/A

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: N/A

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): N/A.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Andi Praja Wira Yudha Luthfi: Surgeon in charge, Writing the article, Data collection, Analysis and Patient follow-up

Adlan Hendarji: Follow-up, Data collection

Ivan Mucharry Dalitan: Follow-up, Data collection

Sigit Wedhanto: Responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Sonbol A., Almulla A., Hetaimish B., et al. Prevalence of femoral shaft fractures and associated injuries among adults after road traffic accidents in a Saudi Arabian trauma center. J. Musculoskelet. Surg. Res. 2018;2(2):62. doi: 10.4103/jmsr.jmsr_42_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denisiuk M., Afsari A. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2022. Femoral shaft fractures. [Updated 2022 Feb 4] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perumal R., Shankar V., Basha R., Jayaramaraju D., Rajasekaran S. Is nail dynamization beneficial after twelve weeks – an analysis of 37 cases. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 2018;9(4):322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omerovic D., Lazovic F., Hadzimehmedagic A. Static or dynamic intramedullary nailing of femur and tibia. Med. Arch. (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina) 2015;69(2):110–113. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.110-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irfan B., Khan A., Ahmad S. Static versus dynamic interlocking intramedullary nailing in fractures shaft of femur. From Gomal. J. Med. Sci. 2015;13(2):104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qureshi A.R., Shah F.A., Ali M.A., Khan U.Z. Outcome of Femoral Shaft Fractures Treated With Interlocking Nails : Dynamization Mode Versus Static Mode. 10(4) 2018. pp. 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gänsslen A., Gösling T., Hildebrand F., Pape H.C., Oestern H.J. Femoral shaft fractures in adults: treatment options and controversies. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cechoslov. 2014;81(2):108–117. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25105784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillai M.G. Effect of early protected weight bearing in fractures of shaft of femur. Int. J. Res. Orthop. 2019;5(5):851. doi: 10.18203/issn.2455-4510.intjresorthop20193591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trompeter A., Newman K. Femoral shaft fractures in adults. Orthop. Trauma. 2013;27(5):322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.mporth.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalid M., Hashmi I., Rafi S., Shah M.I. Dynamization versus static antegrade intramedullary interlocking nail in femoral shaft fractures. J. Surg. Pak. 2015;20(3):76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cift H., Eceviz E., Avcı C.C., et al. Intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures with compressive nailing using only distal dynamic hole and proximal static hole. Open J. Orthop. 2014;04(02):27–30. doi: 10.4236/ojo.2014.42005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somani D.A.M., Saji D.M.A.A., Rabari D.Y.B., Gupta D.R.K., Jadhao D.A.B., Sharif D.N. Comparative study of static versus dynamic intramedullary nailing of tibia. Int. J. Orthop. Sci. 2017;3(3e):283–286. doi: 10.22271/ortho.2017.v3.i3e.52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh A.J., Onggo J.R., Hockings J., Damasena I. Comparison of dynamic versus static fixation of intramedullary nailing in tibial diaphyseal fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 2022;32 doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2022.101941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li A.B., Zhang W.J., Guo W.J., Wang X.H., Jin H.M., Zhao Y.M. Reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing for the treatment of femoral fractures a meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled trials. Med (United States) 2016;95(29):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X., Chen Y., Chen B., et al. Reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing for the treatment of femoral shaft fractures among adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Sci. 2022;27(4):850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2021.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]