Abstract

The corrosion inhibition effects of five concentrations (5E-5 M to 9E-5 M) of ethyl-(2-(5-arylidine-2,4-dioxothiazolidin-3-yl) acetyl) butanoate, a novel thiazolidinedione derivative code named B1, were investigated on mild steel in 1 M HCl using gravimetric analysis, electrochemical analysis and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. After synthesis and purification, B1 was characterized using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. All gravimetric analysis experiments were carried out at four different temperatures: 303.15 K, 313.15 K, 323.15 K and 333.15 K, achieving a maximum percentage inhibition efficiency of 92% at 303.15 K. The maximum percentage inhibition efficiency obtained from electrochemical analysis, conducted at 303.15 K, was 83%. Thermodynamic parameters such as ΔG°ads showed that B1 adsorbs onto the MS surface via a mixed type of action at lower temperatures, transitioning to exclusively chemisorption at higher temperatures.

Keywords: Corrosion novel thiazolidinedione derivative chemisorption mild steel butanoate

1. Introduction

Mild steel (MS), also known as plain-carbon steel, is an important metal with a variety of applications in industry [1]. It is used in the fabrication of reaction vessels, storage tanks, construction of petroleum refineries, as a building material, in machinery and construction of pipes [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Mild steel frequently encounters corrosive conditions in industry, primarily brought about by acids such as hydrochloric acid (HCl) [6,7]. Hydrochloric acid is used extensively in industry for processes such as acid pickling and descaling, well acidizing and electrochemical etching [[8], [9], [10]]. The acid induced corrosion of MS results in several negative effects such as reduction in mechanical strength, crumbling of MS structures and fluid intrusion in containers and pipelines [[11], [12], [13]]. The need to reduce HCl induced corrosion of MS has led to the use of corrosion inhibitors (CIs), typically added to the acid in small concentrations. This results in a significant reduction in corrosion, prolonging the useful life of the metal [14].

To achieve the desired protective effect, CIs must meet certain structural requirements: they must have an abundance of heteroatoms (P, N, S and O) and must also possess multiple bonds [15]. Such compounds have been used extensively as CIs for metals in aqueous environments [16,17]. Heteroatoms and multiple bonds are electron rich centres that can potentially donate electron density to the metal surface, increasing the likelihood that dative covalent bonds can be formed between the CI and the metal. This results in the formation of a strong and durable adsorption film on the metal surface, protecting it from corrosion. Organic compounds are thus desirable as CIs as they possess all the necessary structural qualities [18]. The novel thiazolidinedione derivative (TZD) highlighted in this article has all the structural qualities mentioned above: the presence of heteroatoms (N, O, and S) and double bonds. Extensive corrosion research has been carried out on other TZDs [[19], [20], [21]]. Gravimetric analysis experiments by Chaouiki et al. [19] indicated that the TZDs MeOTZD and MeTZD showed good inhibition for carbon steel in 1 M HCl, with maximum percentage inhibition efficiencies (%IE) of 94% and 83% respectively. Potentiodynamic polarization (PDP) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments by Lgaz et al. [20] showed that the TZDs MTZD and ATZD attained maximum %IE of 90% and 96% respectively for PDP and 94% and 98% respectively for EIS. These results are in keeping with data presented in this paper and show that TZDs are potent CIs for metals in aggressive environments.

However, when selecting a potential CI, its molecular structure should not be the only consideration. Many CIs in use today are toxic and thus harmful to human health and the environment. Some of these toxic CIs include polyphosphates, chromates and benzothiazoles [[22], [23], [24]]. Birkholz et al. [25] stated that benzothiazoles are used extensively as anticorrosive agents in engine coolants, aircraft de-icers, antifreeze liquids and dishwashing liquids, where they are used to protect silver from corrosion. Benzothiazoles have been associated with dermal sensitization, respiratory tract irritation, endocrine disruption, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity [26]. Liao et al. [26] noted that rubber factory workers exposed to 2-mercapto-benzothiazole had a high prevalence of cancers such as bladder cancer, lung cancer and leukaemia. Toxic effects of polyphosphates and chromates include nose bleeds, sores, major organ toxicity and increased risk of strokes and heart attacks [27,28]. The TZD discussed in this work is neither a benzothiazole, polyphosphate nor a chromate, making it far more desirable as a CI.

Table 1 shows the total cost of corrosion (CoC) incurred by different countries and regions around the world. Table 1 also shows the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) lost to corrosion. The data was obtained from sectors such as infrastructure, utilities, transportation, production, and manufacturing [29]. All these sectors make extensive use of MS. Table 1 emphasizes the importance of discovering new, effective CIs to protect MS. Developing effective CIs will result in significant savings by different economic sectors, leading to a 3%–4% improvement in GDP for countries [30]. There are also environmental benefits to using more effective CIs, primarily the reduction of CO2 emissions associated with the production of more steel to replace corroded steel [31]. Due to the high %IE attained by B1 in protecting MS in 1 M HCl, it can be said that such a CI has been developed.

Table 1.

Global cost of corrosion [29].

| Economic regions | Total CoC (USD Billion) | CoC (% GDP) |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 451.3 | 2.7 |

| India | 70.3 | 4.2 |

| Europe | 701.5 | 3.8 |

| Arab world | 140.1 | 5.0 |

| China | 394.9 | 4.2 |

| Russia | 84.5 | 4.0 |

| Japan | 51.6 | 1.0 |

This paper represents the first time B1 has been used in corrosion studies. Originally synthesized as a potential antidiabetic agent by Tshiluka et al. [32], the molecular structure of B1 made it an ideal candidate for use as a CI for MS in 1 M HCl. In addition, B1 is not commercially available. This necessitated the addition of an extra dimension to the study, that of organic synthesis. An exhaustive search of literature showed that B1 has never been synthesized let alone used in anyway outside of the University of Venda (UNIVEN) Chemistry Department, of which Tshiluka et al. [32] and the authors of this paper are members. This adds yet another novelty aspect to this paper.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Most of the mass of the MS coupons was made up of Fe, with the balance shared amongst a variety of different elements (Table 2). Each of the MS coupons had a 6 mm hole in the centre through which a glass hook was inserted for gravimetric analysis (GA) and for preparing MS coupons for Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The length and width of the MS pieces were 3 cm and 2 cm, respectively.

Table 2.

Elemental composition of mild steel coupons.

| Element | Fe | C | Ni | Mn | S | P | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass % | 99.32 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

2.2. Preparation of solutions

Each 1 M HCl solution was prepared using ultrapure de-ionized water and fuming, 32% HCl. All in all, five different solutions of B1 were prepared: 5 E-5M, 6 E-5M, 7 E-5M, 8 E-5M, and 9 E-5M. B1 is insoluble in water. Therefore, dissolving B1 in an organic solvent was necessary before commencement of corrosion studies. Even so, gentle heating with magnetic stirring was needed to ensure B1 remained dissolved. The organic solvent used to dissolve B1 was anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis). The total amount of DMSO required to dissolve B1 ranged from 1 to 2 mL. Table 3 shows the percentage purity of all reagents used throughout the study.

Table 3.

Percentage purity of reagents.

| Reagents | % Purity |

|---|---|

| Bromoacetyl chloride | ≥98 |

| Dichloromethane | ≥99.8 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (anhydrous) | ≥99.5 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (NMR solvent) | 99.9 |

| DL-2-aminobutyric acid | 99 |

| Ethanol | 95 |

| Hydrochloric acid | 32 |

| Para-anisaldehyde | 98 |

| Piperidine | ≥99 |

| Potassium chloride | ≥99 |

| Potassium hydroxide pellets | ≥85 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 99.9 |

| 2,4-thiazolidinedione (Technical grade) | 90 |

| Thionyl chloride | ≥99 |

2.3. Synthesis and characterization of B1

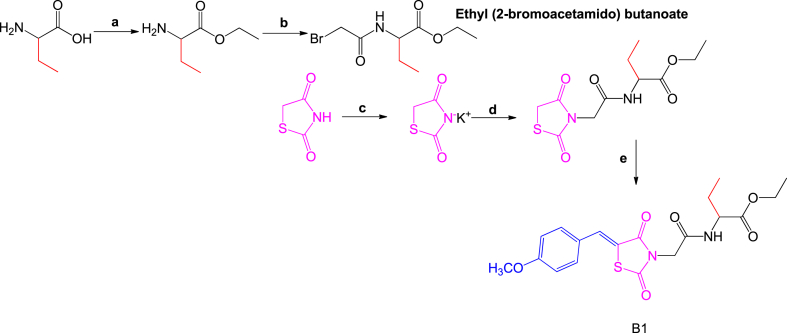

The synthetic steps followed to synthesize B1 (Fig. 1) are highlighted in the work done by Tshiluka et al. [32]. All reagents used were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, United States). After purification, 50 mg of B1 was dissolved in DMSO‑d6 and characterized using a Bruker Ultra shield plus 400 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer (Billerica, United States). Specifically, B1 was subjected to three NMR characterization techniques: proton NMR (1H NMR) at 400 MHz, carbon-13 NMR (13C NMR) at 100 MHz and DEPT-135, also at 100 MHz.

Fig. 1.

B1 reaction scheme.

2.4. Gravimetric analysis

Gravimetric analysis experiments were conducted at four different temperatures in Memmert water baths (Buchenbach, Germany): 303.15 K, 313.15 K, 323.15 K and 333.15 K. All MS coupons were gently polished using Struers 200 mm silicon-carbide (SiC) emery paper attached to a Struers LaboSystem instrument (Cleveland, United States). After polishing, all MS coupons were rinsed with acetone, dried then weighed before immersion in both uninhibited and inhibited 1 M HCl solutions. After an immersion period of 5 h, the MS coupons were gently brushed, re-rinsed with acetone, re-dried and re-weighed. The difference in masses was recorded and used in subsequent calculations.

2.5. Electrochemical analysis

A BioLogic SP-150 instrument (Seyssinet-Pariset, France) was used for all electrochemical experiments. All MS coupons were cut into squares with a surface area of 1 cm2. All cut MS coupons were attached to electrical conducting wires, embedded in a synthetic resin, and polished before being used as working electrodes (WE). As with GA, the polishing was done using a Struers LaboSystem instrument (Cleveland, United States) with 200 mm SiC emery paper. The other two electrodes used were a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrode (with a saturated KCl filling solution) and a graphite counter electrode. Thirty minutes was allotted for the WE to reach open circuit potential (OCP), also known as corrosion potential (Ecorr), before commencement of experiments.

2.6. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

An ALPHA FT-IR Brucker platinum 22 vector instrument (Billerica, United States) was used for all FTIR experiments. After pre-treatment of two MS coupons (see Section 2.4), one coupon was immersed in an inhibited 1 M HCl solution and the other in an uninhibited 1 M HCl solution. After an immersion period of 5 h, both metal coupons were removed from the aggressive solutions and allowed to corrode over a sufficient period. The corrosion products formed on the metal surfaces were then scrapped off and subjected to FTIR analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. B1 NMR spectra

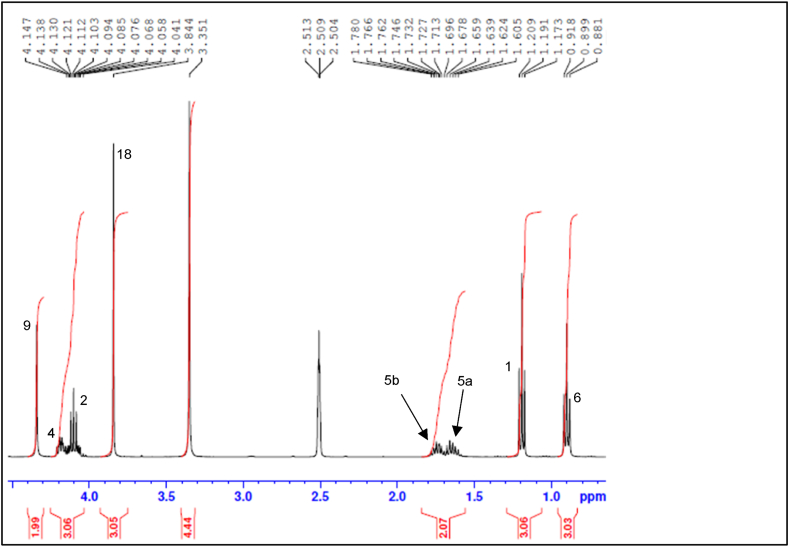

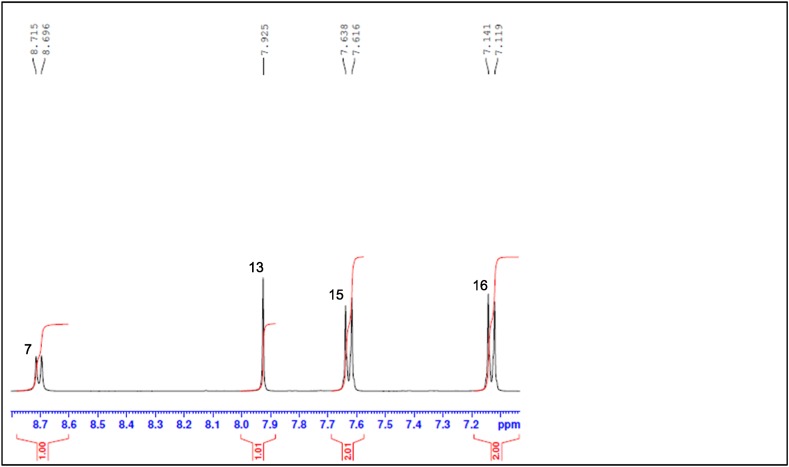

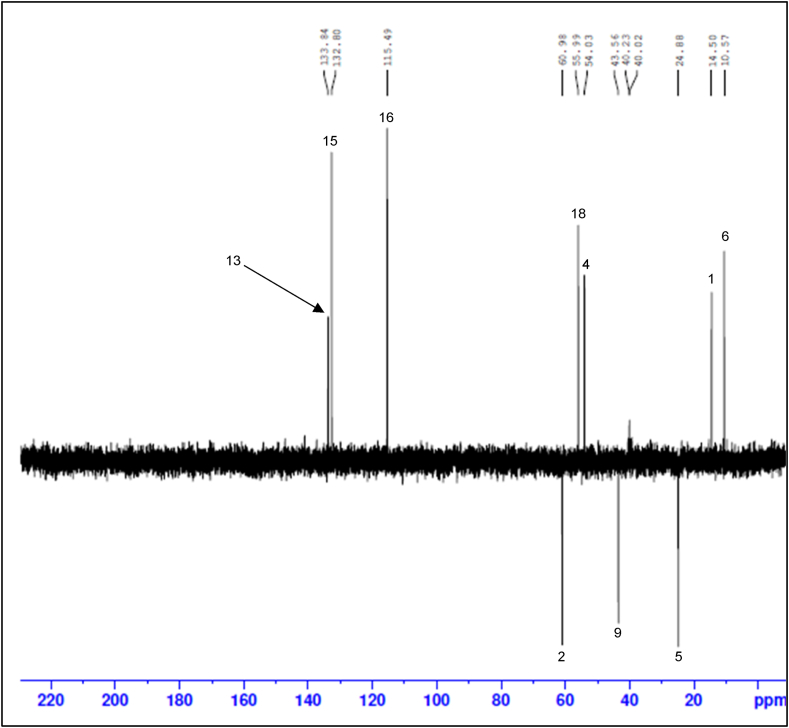

The NMR spectra below show that the synthesis of B1 was successful. Fig. 2 shows the full 1H NMR spectrum of B1, encompassing the aliphatic, heteroatomic and aromatic regions. The expanded aliphatic to heteroatomic region of the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 3) shows a total of eight peaks, with the two protons on C-5 (H-5a and H-5b) being non-equivalent due to the stereogenic centre at C-4. The aliphatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum shows three methyl group peaks at 0.89 ppm, 1.19 ppm and 3.84 ppm ascribed to H-6 (doublet), H-1 (doublet) and H-18 (singlet) respectively. The aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum shows four peaks: H-7 (doublet) at 8.70 ppm, H-15 (doublet) at 7.62 ppm, H-16 (doublet) at 7.13 ppm and H-13 (singlet) at 7.92 ppm (Fig. 4). Proton H-7 has the highest chemical shift due to the electronegative nature of the N atom to which it is bonded [33]. The DEPT-135 spectrum, which shows methylene (negative peak), methine (positive peak) and methyl (positive peak) carbons in the molecular structure of a compound [34], confirmed that the structure contains three methylene groups: C-2 at 60.98 ppm, C-9 at 43.56 ppm and C-5 at 24.88 ppm (Fig. 5). Also, a combination of DEPT-135 and 13C NMR spectra confirmed that the structure contains seven quaternary carbons: C-11 at 172.03 ppm, C-3 at 167.54 ppm, C-8 and C-10 at 165.80 ppm, C-17 at 161.73 ppm, C-14 at 125.81 ppm and C-12 at 118.24 ppm. The 13C NMR spectrum (Fig. 6) which, unlike the DEPT-135 spectrum, includes quaternary carbons [35], also showed the presence of one methine carbon at 54.03 ppm (C-4) and three methyl carbons at 56 ppm (C-18), 14.50 ppm (C-1) and 10.57 ppm (C-6).

Fig. 2.

B1 full 1H NMR spectrum.

Fig. 3.

B1 1H NMR spectrum (aliphatic and heteroatomic region).

Fig. 4.

B1 1H NMR spectrum (aromatic region).

Fig. 5.

B1 DEPT-135 spectrum.

Fig. 6.

B1 13C NMR spectrum.

3.2. Gravimetric analysis

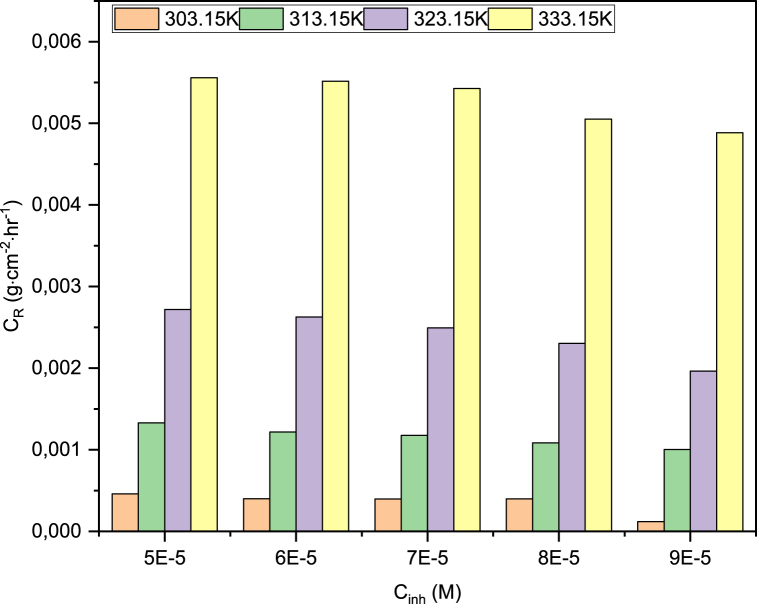

Three sets of important data were obtained from GA: %IE, metal corrosion rate (CR) and thermodynamic data. Fig. 7, Fig. 8 show the relationship between %IE Equation (1), CR Equation (2) and inhibitor concentration (Cinh) [36]. As the name suggests, %IE is a measure of how effective an inhibitor is at protecting a substrate, in this case MS, from corrosion. The higher the %IE, the greater the degree of protection. Under isothermal conditions, an increase in Cinh results in an increase in %IE. This is due to an increase in fractional coverage (θ) Equation (3) [36]. An increase in %IE also corresponds with a decrease in CR. The above-mentioned trends in %IE and CR have been reported elsewhere [[37], [38], [39]]. Olomola et al. [39] noted that all three CIs studied exhibited higher %IE with an increase in their concentrations.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

were Wb, Wa, A, t, wo and wi are the metal weight before immersion, metal weight after immersion, total metal surface area, immersion time and the weight loss values in the absence and presence of B1 respectively [[40], [41], [42], [43]].

Fig. 7.

Relationship between inhibitor concentration and percentage inhibition efficiency.

Fig. 8.

Relationship between inhibitor concentration and metal corrosion rate.

At much higher temperatures, the %IE is significantly lower (Fig. 7). Some of the B1 molecules desorb from the adsorption sites on the metal surface, leading to a decrease in both θ and %IE. This has also been reported elsewhere [38,39,44,45]. Olomola et al. [39] stated that one of the CIs studied, an inhibitor code named 4a, showed higher %IE at lower temperatures. This drop in θ exposes parts of the metal surface to more frequent and forceful collisions from corrosive species in the aggressive environment, especially highly corrosive Cl− ions, increasing the metal CR [[46], [47], [48]]. Noor [48], observed that HCl is more corrosive than H2SO4 at all studied temperatures (30°C–70 °C) because of the more corrosive nature of Cl− ions on MS.

3.3. Adsorption and activation parameters

3.3.1. Adsorption parameters

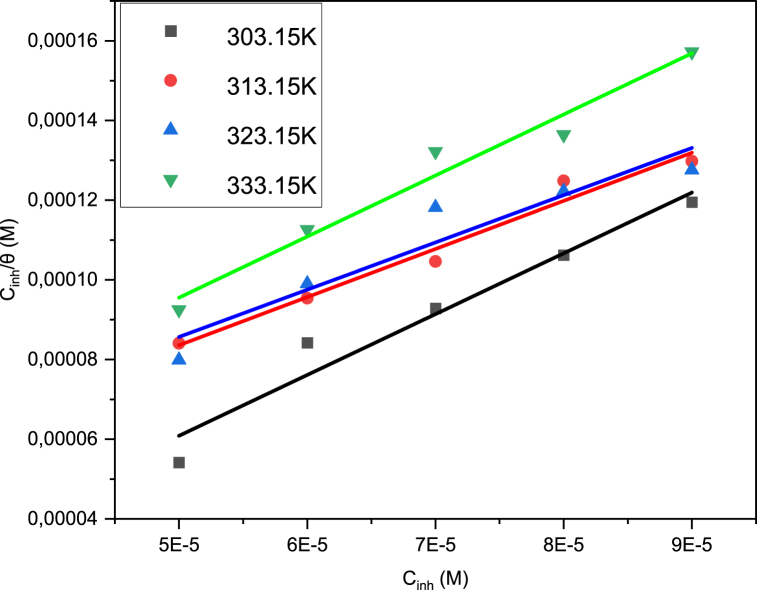

Adsorption isotherms are a key tool in the toolbox of corrosion scientists as they provide a simplified model of the pathway through which corrosion inhibitors adsorb onto a metal surface [49]. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm (LAI), which is the simplest adsorption isotherm developed, was the best fit for B1. Using Equation (4), the LAI (Fig. 9) is obtained from plotting Cinh/θ (y-axis) and Cinh (x-axis), with a y-intercept of 1/Kads [50,51]:

| (4) |

were Kads is the adsorption equilibrium constant.

Fig. 9.

B1 Langmuir adsorption isotherms.

Once Kads is obtained, the standard Gibbs free energy change of adsorption (ΔG°ads) is calculated using Eq. (5) [52]:

| (5) |

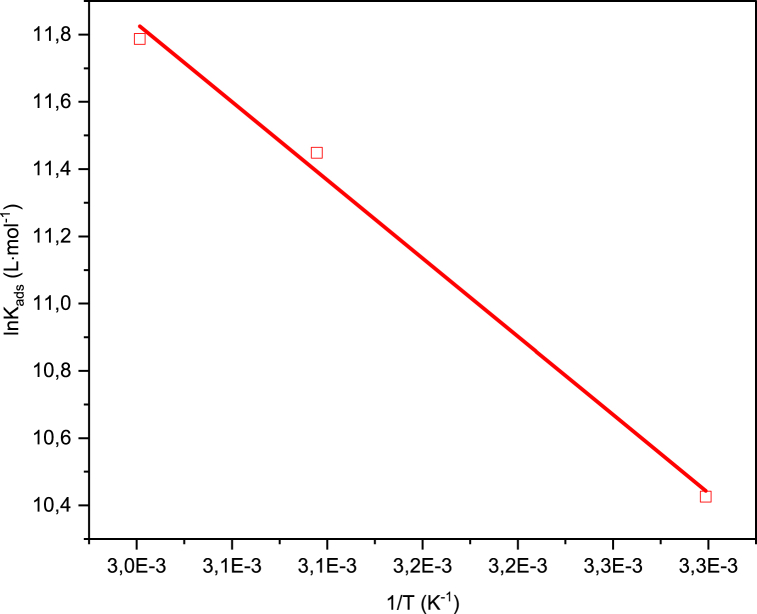

were R, T and 55.5 are the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), the temperature (in Kelvin) and the molar concentration of pure water respectively [53]. Using the van't Hoff equation (Eq. (6)), a plot of lnKads vs 1/T (Fig. 10) is used to obtain the standard enthalpy change of adsorption (ΔH°ads) [54,55]:

| (6) |

were ΔS°ads is the standard entropy change of adsorption.

Fig. 10.

B1 van't Hoff plot.

Using the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation (Eq. (7)), together with the ΔH°ads obtained from Equation (6), ΔS°ads data is calculated at all four different temperatures:

| (7) |

Table 4 shows a summary of the LAI parameters and adsorption data obtained from Equations (4), (5), (6), (7). The coefficient of determination (r2) values are close to unity and thus show that the LAI is a good fit for the experimental data obtained [56]. Bashir et al. [56] indicated that if ΔH°ads is negative, the adsorption of the CI onto the metal surface is exothermic. Therefore, a positive ΔH°ads (38.67 kJ mol−1) is indicative of endothermic adsorption. This shows that B1 molecules, once adsorbed onto the metal surface, repel one another (due to their bulky nature) [57]. This necessitates the supply of additional heat energy (q) to override the increased energy generated by the repulsive forces, hence the endothermic nature of the adsorption.

Table 4.

B1 adsorption parameters.

| Temperature (K) | r2 | Kads |

ΔG°ads kJ·mol−1 | ΔH°ads kJ·mol−1 | ΔS°ads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L·mol−1 | J·mol−1∙K−1 | ||||

| 303.15 | 0.9516 | 33717.5 | −36.40 | 38.67 | 178.83 |

| 313.15 | 0.9735 | 66811.96 | −39.38 | 38.67 | 181.57 |

| 323.15 | 0.9069 | 93773.44 | −41.55 | 38.67 | 181.63 |

| 333.15 | 0.9692 | 131485.52 | −43.77 | 38.67 | 181.85 |

The additional q not only increases the spontaneity of adsorption of B1 onto the metal surface but, also facilitates the formation of additional dative covalent bonds between B1 and the metal surface. This is shown by the increasingly negative ΔG°ads values, as B1 transitions from being an inhibitor that adsorbs in a mixed manner (−40 kJ mol−1 < ΔG°ads ≤ −20 kJ mol−1) [[58], [59], [60]], to one that adsorbs primarily via chemisorption (ΔG°ads ≤ −40 kJ mol−1) [61]. This increase in the spontaneity of adsorption as the temperature is increased also explains the increase in the Kads data from 33,718 L mol−1 to 131,486 L mol−1. The more the adsorption of the adsorbate onto the adsorbent is favoured, the higher Kads becomes [56].

An increase in temperature results in a steady increase in ΔS°ads. Nwosu and Muzakir [62], reported negative ΔS°ads values, stating they represent the adsorption of the CI onto the MS surface. Therefore, positive ΔS°ads data is indicative of desorption from the metal surface. This is supported by Atkins and De Paula [57], when they stated that positive ΔS°ads data indicates an increase in the translational energy of inhibitor molecules at the metal surface. This increase in translational energy results in a weakening of the bonds formed between B1 molecules and the MS surface. However, given the slight increase in ΔS°ads, most of the bonds formed between B1 and the MS surface remain largely intact and unaffected. This emphasizes why chemisorption is the most ideal mode of adsorption as it forms resilient and tough protective films on the metal surface [63].

3.3.2. Activation parameters

Activation parameters are a key component in describing the metal corrosion process. These parameters consist of activation energy (Ea), standard enthalpy change of activation (ΔH°act) and standard entropy change of activation (ΔS°act). All activation parameters are shown in Table 5. Activation energy is calculated using the Arrhenius equation (Eq. (8)) whereas ΔH°act and ΔS°act are obtained using the transition state equation (Eq. (9)), an alternative form of (Eq. (8)) [54].

| (8) |

were A is the Arrhenius constant, susceptible to the type of metal being used and the aggressive environment into which it has been immersed [64].

| (9) |

were N and h are the Avogadro and Planck constants respectively. A plot of log (CR/T) against 1/T yields a straight line with slope (-ΔH°act/2.303 R) and a y-intercept of [log (R/Nh)+(ΔS°act/2.303 R)] [65].

Table 5.

B1 activation parameters.

| Cinh (M) | Eact (kJ·mol−1) | ΔH°act (kJ·mol−1) | ΔS°act (J·mol−1∙K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 54.69 | 54.68 | −118.29 |

| 5E-5 | 68.87 | 68.86 | −82.66 |

| 6E-5 | 68.89 | 68.87 | −81.79 |

| 7E-5 | 69.54 | 69.53 | −81.20 |

| 8E-5 | 74.30 | 74.29 | −65.18 |

| 9E-5 | 101.14 | 101.13 | 17.05 |

All Ea values for the inhibited 1 M HCl solutions are larger than the Ea of the uninhibited 1 M HCl solution [66,67]. This is an indication that in the presence of B1 molecules the corrosion process is suppressed significantly [68]. As Cinh is increased, Ea also increases [55,69]. As a result, 9E-5 M has the highest Ea of all the studied concentrations, as can be deduced from its much steeper Arrhenius plot (Fig. 11). Plotting LogCR vs 1/T yields straight lines with a slope of -Ea/R [64].

Fig. 11.

B1 Arrhenius plots.

All ΔH°act values are approximately the same as their corresponding Ea values [67]. Diki et al. [67] attributed the closeness of Ea and ΔH°act data to the equation ΔH°act = Ea-RT. However, Table 5 shows that Ea and ΔH°act are virtually identical. Since all experiments were carried out under constant pressure conditions and, q = Ea, it follows that ΔH°act = q. Therefore, Ea = ΔH°act. This explains the similarity in Ea and ΔH°act data. In addition, all ΔH°act values are positive. Thoume et al. [70] attribute this to chemisorption.

As Cinh is increased, ΔS°act becomes more positive, indicating an increase in the extent of disorder at the metal surface [56,67]. Diki et al. [67] attribute this trend to the formation of an activated complex between the metal surface and the inhibitor molecules, resulting in the displacement of H2O molecules from the MS surface (Eq. (10)). Therefore, the adsorption of B1 molecules onto the MS surface can be regarded as a quasi-water displacement process governed by the equilibrium equation below [71]:

| (10) |

were Inhsol, H2Oads, Inhads and H2Osol are the inhibitor molecules in solution, adsorbed water molecules, adsorbed inhibitor molecules and displaced water molecules respectively.

3.4. Potentiodynamic polarization

The corrosion inhibition effects of five concentrations of B1 were studied at 303.15 K. The potential of the WE was varied both in the cathodic and anodic directions over a pre-set potential range of -1 V to +1 V. Tafel plots (Fig. 12, Fig. 13) were then plotted, enabling the calculation of all the parameters shown in Table 6. The logarithm of corrosion current (Logicorr) values for the inhibited 1 M HCl solutions are lower than that of the uninhibited solution (Fig. 12, Fig. 13), as reported elsewhere [[72], [73], [74]]. This is an indication that, in the presence of B1, MS corrosion is suppressed [75]. Fig. 13 shows a shift to more positive and negative potentials by anodic and cathodic curves respectively. This shows that B1 is a mixed action inhibitor, preventing corrosion at both anodic and cathodic sites on the MS surface [76].

Fig. 12.

B1 Tafel plot (Full scale plot).

Fig. 13.

B1 Tafel plot (Expanded version).

Table 6.

B1 PDP parameters.

| Concentration (M) | CR (mpy) | Ecorr (mV) | icorr (μA) | βa (mV·dec−1) | βc (mV·dec−1) | Rp (Ω) | %IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 380 | −426 | 866 | 70 | 127 | 180 | – |

| 5E-5 | 155 | −455 | 339 | 53 | 94 | 379 | 61 |

| 6E-5 | 135 | −456 | 295 | 60 | 126 | 415 | 66 |

| 7E-5 | 123 | −439 | 270 | 59 | 104 | 437 | 69 |

| 8E-5 | 88 | −435 | 191 | 58 | 120 | 449 | 78 |

| 9E-5 | 67 | −438 | 146 | 63 | 123 | 690 | 83 |

All CR values for inhibited solutions are significantly lower than the CR for the uninhibited solution (Table 6) [66], [77]. This shows that corrosion of MS is suppressed when B1 is added to the 1 M HCl solution. A decrease in CR corresponds to a decrease in icorr (Table 6). In turn, a decrease in icorr results in an increase in %IE (Table 6). Corrosion current can therefore be used to calculate %IE according to Eq. (11) [78]:

| (11) |

were iocorr and iicorr are the corrosion currents in the uninhibited and inhibited solution respectively.

An increase in CR also corresponds to a decrease in polarization resistance (Rp), as reported by Thoume et al. [70] and Jalab et al. [54]. A decrease in Rp is an indication of decreasing %IE [79]. Therefore, Rp can also be used to calculate %IE according to Eq. (12) [78]:

| (12) |

were Rop and Rip are the polarization resistances for the uninhibited and inhibited solutions respectively. All Rp values for inhibited solutions are significantly larger than the Rp for the uninhibited solution, another positive sign that corrosion inhibition of MS is taking place in the presence of B1 [80].

The deviation from Ecorr is < 85 mV, indicating that B1 is a mixed action inhibitor, inhibiting the corrosion process at both the anodic and cathodic sites on the WE surface [[81], [82], [83]]. However, the cathodic Tafel constants (βc) change more significantly than the anodic Tafel constants (βa) on addition of B1 to the 1 M HCl solution, an indication that the formation of H2(g) at the cathodic sites is impaired more than the dissolution of MS at the anodic sites [84].

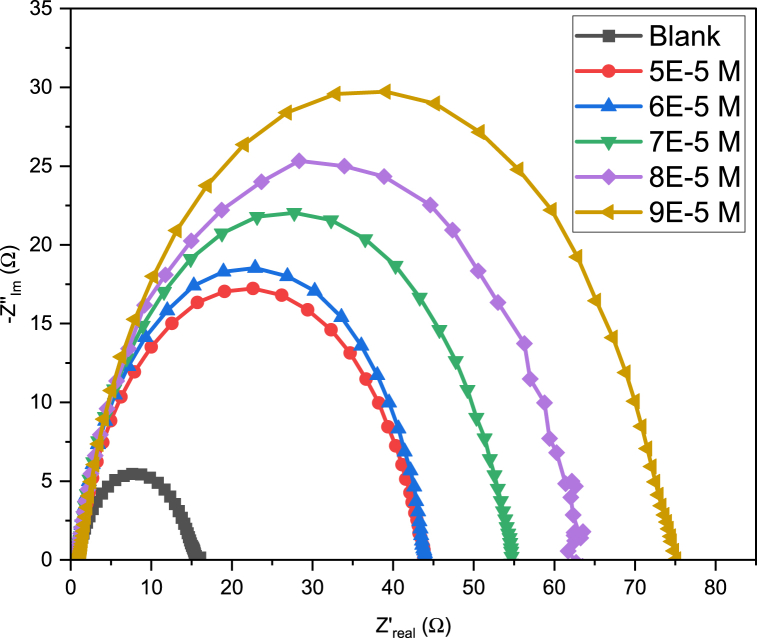

3.5. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

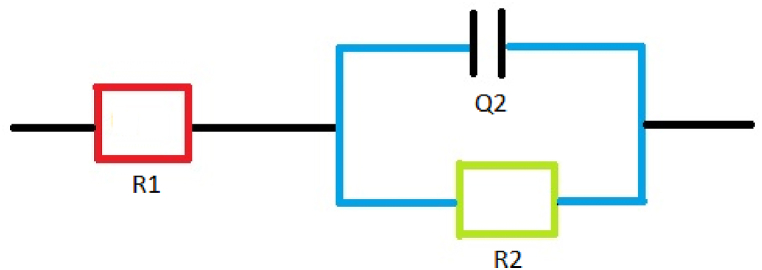

The EIS parameters that define the adsorption of B1 onto the MS surface are shown in Table 7. These parameters were obtained by fitting a modified Randels circuit (Fig. 14) to real (Z′) and imaginary (-Z″) impedance data points. The fit was done using ZSimDemo 3.30 d software. A plot of the (Z’; -Z″) coordinates, using OriginPro graphing and analysis software, produced Nyquist plots (Fig. 15).Were R1, R2 and Q2 are the solution resistance (Rs), charge transfer resistance (Rct) and the constant phase element respectively [85].

Table 7.

B1 EIS parameters.

| Concentration (M) | Rct (Ω) | Rs (Ω) | Χ2 | n | Qdl (μF) | %IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15.27 | 0.73 | 0.0008478 | 0.7951 | 225.14 | – |

| 5E-5 | 42.82 | 0.856 | 0.007498 | 0.9035 | 129.44 | 64.34 |

| 6E-5 | 43.41 | 0.865 | 0.01525 | 0.8817 | 104.13 | 64.82 |

| 7E-5 | 53.22 | 0.897 | 0.0009147 | 0.8649 | 101.81 | 71.31 |

| 8E-5 | 61.03 | 0.932 | 0.0006241 | 0.8861 | 96.00 | 74.98 |

| 9E-5 | 73.69 | 1.156 | 0.001487 | 0.8594 | 84.33 | 79.29 |

Fig. 14.

Modified Randels circuit.

Fig. 15.

B1 Nyquist plots.

Table 7 shows that all Rct values for the inhibited 1 M HCl solutions are much larger than that of the uninhibited solution [86]. Table 7 also shows that an increase in Cinh results in an increase in Rct [79,87]. This is because, as Cinh is increased, more and more molecules of B1 adsorb onto the surface of the WE, protecting it from corrosion [86]. For this reason, any increase in Rct corresponds to an increase in %IE (Table 5). Therefore, Rct can be used to calculate %IE according to Eq. (13) [88]:

| (13) |

were Roct and Rict are the charge transfer resistances of the uninhibited and inhibited solutions respectively.

The Solution resistance also increases as Cinh is increased, a trend also reported by Bashir et al. [56] and Mashuga et al. [89]. Although in Mashuga et al. [89], only one of the four compounds studied (P4) follows this trend perfectly. Mashuga et al. [89] also notes that Rs for the blank is lower than that of the inhibited solutions. Mashuga et al. [89] and Daoud et al. [90] put this down to a decrease in the solution conductivity and the adsorption of inhibitor molecules onto the metal surface.

Since a modified Randles circuit (Fig. 14) was the best fit for the impedance data obtained, the constant phase element (CPE), denoted as Q2 in Fig. 14, was used in place of an ideal capacitor. The CPE compensates for the complexity of the system brought about by the roughness of the WE surface [91]. Double layer capacitance (Cdl) was calculated as shown (Eq. (14)) [54]:

| (14) |

were n and Y0 are the phase shift and CPE constant respectively.

Since the CPE was used in place of an ideal capacitor, Cdl has been replaced by Qdl (Table 7). Table 7 shows a decrease in Qdl as Cinh is increased. This is because B1 molecules displace H2O molecules from the WE surface as they adsorb onto it, lowering Qdl [92]. The low chi-squared (Χ2) values show that the modified Randles circuit (Fig. 14) fits the EIS data very well [70].

3.6. Adsorption film analysis

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy is a simple, quick, non-destructive, and affordable technique for characterizing the functional groups of molecules present in a sample [93]. It can be used for the analysis of solids, liquids, and gases [94]. Only molecules with a net dipole moment can absorb infrared radiation and therefore only such molecules can be characterized using FTIR [95].

The FTIR spectrum for B1 (Fig. 16) shows two sets of peaks between 2500 cm−1 and 3500 cm−1. The first intense peak just before 3500 cm−1 (green square) represents the N–H amine stretch whereas the second, less intense cluster of peaks at approximately 3000 cm−1 (yellow square) corresponds to aromatic and alkyl C–H stretches [96,97]. Both peaks are absent in the spectrum of the adsorption layer, an indication that both the N atom and the aromatic ring take part in the formation of an adsorption film on the MS surface. The carbonyl (C O) peak at 1700 cm−1 (purple square) experiences a significant reduction in its intensity as B1 adsorbs onto the metal surface. This shows that the C O groups also participate in the formation of an adsorption film on the metal surface. A reduction in the intensity of the C–O ester stretch (1100 cm−1 to 1200 cm−1), as shown by the B1 adsorption layer spectrum, suggests the O heteroatoms found in the ester functional group of B1 take part in the formation of an adsorption film on the MS surface.

Fig. 16.

Ftir spectra for B1.

4. Conclusions

-

•

Gravimetric analysis results show that B1 is a very good corrosion inhibitor for MS in 1 M HCl, achieving a maximum %IE of 92%.

-

•

The ΔS°act data shows the displacement of water molecules from the metal surface as Cinh increases and the formation of a protective adsorption film.

-

•

The ΔG°ads data shows that the adsorption of B1 onto the metal surface is not only spontaneous but shifts from a mixed type of adsorption (mostly chemisorption in nature) to chemisorption as the temperature is increased.

-

•

A positive ΔH°ads value (38.67 kJ mol−1) is indicative of the endothermic nature of the adsorption of B1 onto MS, showing that chemisorption is the favoured mode of adsorption.

-

•

The Ecorr data obtained from PDP analysis shows that the WE is polarized by < 85 mV, showing that B1 is a mixed action inhibitor, suppressing MS corrosion at both anodic and cathodic sites on the WE surface. However, both Tafel plots and the βc constants show that B1 suppresses MS corrosion by acting mainly at the cathodic sites on the WE surface, hindering the evolution of H2 gas.

-

•

As Cinh is increased, icorr, Rp, CR and %IE decrease, increase, decrease and increase respectively. This shows the success of B1 in suppressing the corrosion of MS in 1 M HCl.

-

•

EIS analysis shows that a modified Randels circuit is the best fit for the impedance data obtained.

-

•

EIS data also shows that as Cinh increases, parameters such as Rct, %IE, and Qdl increase, increase, and decrease respectively. This is further evidence of the ability of B1 to suppress MS corrosion in 1 M HCl.

-

•

The (n) data, which is close to unity, is indicative of pseudo-capacitive behaviour of the constant phase element.

Author contribution statement

Nhlalo M. Dube-Johnstone: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Unarine Tshishonga: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Simon S. Mnyakeni-Moleele: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Lutendo C. Murulana: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of the Republic of South Africa Thuthuka (Grant 107,431) and the South African Synthetic Oil Limited (SASOL) University Collaboration Programme Grant.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the South African National Research Foundation (NRF).

References

- 1.Ghuzali N.A.M., Noor M., Zakaria F.A., Hamidon T.S., Husin M.H. Study on Clitoria ternatea extracts doped sol-gel coatings for the corrosion mitigation of mild steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021;6:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari K.R., Quraishi M.A., Singh A. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in hydrochloric acid by some pyridine derivatives: an experimental and quantum chemical study. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;25:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahlakeh G., Ramezanzadeh B., Dehghani A., Ramezanzadeh M. Novel cost-effective and high-performance green inhibitor based on aqueous Peganum harmala seed extract for mild steel corrosion in HCl solution: detailed experimental and electronic/atomic level computational explorations. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;283:174–195. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doner A., Kardas G. N-Aminorhodanine as an effective corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 0.5 M H2SO4. Corrosion Sci. 2011;53:4223–4232. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabirneeza A.A.F., Subhashini S. A novel water-soluble, conducting polymer composite for mild steel acid corrosion inhibition. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012;127:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunder O., Lapique F., Johnsen B., Nisancioglu K. Effect of pre-treatment on the durability of epoxy bonded AA6060 aluminium joints. Int. J. Adhesion Adhes. 2004;24:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oguzie E.E. Evaluation of the inhibitive effect of some plant extracts on the acid corrosion of mild steel. Corrosion Sci. 2008;50:2993–2998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeed M.T., Saleem M., Usmani S., Malik I.A., Al-Shammari F.A., Deen K.M. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in 1 M HCl by sweet melon peel extract. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2019;31:1344–1351. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obaid A.Y., Ganash A.A., Qusti A.H., Elroby S.A., Hermas A.A. Corrosion inhibition of type 430 stainless steel in an acidic solution using a synthesized tetra-pyridinium ring-containing compound. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:1276–1283. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng S., Li X. Inhibition by Jasminum nudiflorum Lindl. leaves extract of the corrosion of aluminium in HCl solution. Corrosion Sci. 2012;64:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anwar S., Khan F., Zhang Y. Corrosion behaviour of Zn-Ni alloy and Zn-Ni-nano-TiO2 composite coatings electrodeposited from ammonium citrate baths. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2021;141:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foorginezhad S., Mohseni-Dargah M., Firoozirad K., Aryai V., Razmjou A., Abbassi R., Garaniya V., Beheshti A., Asadnia M. Recent advances in sensing and assessment of corrosion in sewage pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2021;147:192–213. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Z., Liao W., Wu W., Du C., Li X. Failure analysis of leakage caused by perforation in an L415 steel gas pipeline. Case Stud. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2017;9:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abboud Y., Abourriche A., Saffaj T., Berrada M., Charrouf M., Bennamara A., Hannache H. A novel azo dye, 8-quinolinol-5-azoantipyrine as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acidic media. Desalination. 2009;237:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Praveen B., Venkatesha T. Metol as corrosion inhibitor for steel. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2009;4:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed M.H.O., Al-Amiery A.A., Al-Majedy Y.K., Kadhum A.A.H., Mohamad A.B., Gaaz T.S. Synthesis and characterization of a novel organic corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1M hydrochloric acid. Results Phys. 2018;8:728–733. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadhim A., Al-Okbi A.K., Jamil D.M., Qussay A., Al-Amiery A.A., Gaaz T.S. Experimental and theoretical studies of benzoxazines corrosion inhibitors. Results Phys. 2017;7:4013–4019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitzhaus T.E., Ortega-Vega M.R., Schroeder R., Muller I.L., Mattedi S., de Fraga Malfatti C. An amino-based protic ionic liquid as a corrosion inhibitor of mild steel in aqueous chloride solutions. Mater. Corros. 2020;71:1175–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaouiki A., Chafiq M., Ko Y.-G., Al-Moubaraki A.H., Thari F.Z., Salghi R., Karrouchi K., Bougrin K., Ali I.H., Lgaz H. Adsorption mechanism of eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for exceptional corrosion protection of carbon steel: electrochemical and first principles DFT evaluations. Metals. 2022;12:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lgaz H., Saha S.K., Lee H.-S., Kang N., Thari F.Z., Karrouchi K., Salghi R., Bougrin K., Ali I.H. Corrosion inhibition properties of thiazolidinedione derivatives for copper in 3.5 wt.% NaCl medium. Metals. 2021;11:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alamry K.A., Aslam R., Khan A., Hussein M.A., Tashkandi N.Y. Evaluation of corrosion inhibition performance of thiazolidine-2,4-diones and its amino derivative: gravimetric, electrochemical, spectroscopic, and surface morphological studies. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2022;159:178–197. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirzakhanzadeh Z., Kosari A., Moayed M.H., Naderi R., Taheri P., Mol J.M.C. Enhanced corrosion protection of mild steel by synergetic effect of zinc aluminium polyphosphate and 2-mercaptobenzimidazole inhibitors incorporated in epoxy-polyamide coatings. Corrosion Sci. 2018;138:372–379. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendig M.W., Buchheit R.G. Corrosion inhibition of aluminium and aluminium alloys by soluble chromates, chromate coatings, and chromate-free coatings. Corrosion. 2003;59:379–400. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jafari H., Akbarzade K., Danaee I. Corrosion inhibition of carbon steel immersed in a 1M HCl solution using benzothiazole derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 2019;12:1387–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkholz D.A., Stilson S.M., Elliot H.S. Analysis of emerging contaminants in drinking water-a review. Earth Syst. Environ. Sci. 2014;2:212–229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao C., Kim U., Kannan K. A review of environmental occurrence, fate, exposure, and toxicity of benzothiazoles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:5007–5026. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farris F.F. third ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2014. Encyclopaedia of Toxicology. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutch N.J. third ed. Academic Press; Massachusetts: 2013. Platelets. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thakur A., Sharma S., Ganjoo R., Assad H., Kumar A. Anti-corrosive potential of the sustainable corrosion inhibitors based on biomass waste: a review on preceding and perspective research. J. Phys. 2022;2267:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch G. Woodhead Publishing; Sawston: 2017. Trends in Oil and Gas Corrosion Research and Technologies. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X., Jiao K., Zhang J., Guo Z. A review on low carbon emissions projects of steel industry in the world. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;306:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tshiluka R.N., Bvumbi M.V., Ramaite I.I., Mnyakeni-Moleele S.S. Synthesis of some new 5-arylidene-2,4-thiazolidinedione esters. Arch. Org. Chem. 2021;5:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marson C.M. third ed. Academic Press; Massachusetts: 2003. Encyclopaedia of Physical Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claridge T.D.W. third ed. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2016. High-resolution NMR Techniques in Organic Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clendinen C.S., Lee-McMullen B., Williams C.M., Stupp G.S., Vandenborne K., Hahn D.A., Walter G.A., Edison A.S. 13C NMR metabolomics: applications at natural abundance. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:9242–9250. doi: 10.1021/ac502346h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olawale O., Bello J.O., Ogunsemi B.T., Uchella U.C., Oluyori A.P., Oladejo N.K. Optimization of chicken nail extracts as corrosion inhibitor on mild steel in 2M H2SO4. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02821. 1, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashir S., Thakur A., Lgaz H., Chung I., Kumar A. Corrosion inhibition efficiency of bronopol on aluminium in 0.5M HCl solution: insights from experimental and quantum chemical studies. Surface. Interfac. 2020;20:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karthik G., Sundaravadivelu M. Investigations of the inhibition of copper corrosion in nitric acid solutions by levetiracetam drug. Egypt. J. Petrol. 2016;25:481–493. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olomola T.O., Durodola S.S., Olasunkanmi L.O., Adekunle A.S. Effect of selected 3-chloromethylcoumarin derivatives on mild steel corrosion in acidic medium: experimental and computational studies. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2022;36:2547–2561. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karthik G., Sundaravadivelu M. Inhibition of mild steel in sulphuric acid using esomeprazole and the effect of iodide ion addition. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2013:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karthik G., Sundaravadivelu M., Rajkumar P. Corrosion inhibition and adsorption properties of pharmaceutically active compound esomeprazole on mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015;41:1543–1558. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nan L., Xu D., Gu T., Song X., Yang K. Microbiological influenced corrosion resistance characteristics of a 304L-Cu stainless steel against Escherichia coli. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015;48:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beese P., Venzlaff H., Srinivasan J., Garrelfs J., Stratmann M., Mayrhofer K.J.J. Monitoring of anaerobic microbially influenced corrosion via electrochemical frequency modulation. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;105:239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 44.James A.O., Oforka N.C., Abiola O.K. Inhibition of acid corrosion of mild steel by pyridoxal and pyridoxol hydrochlorides. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2007;2:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oguzie E.E. Corrosion inhibition of aluminium in acidic and alkaline media by Sansevieria trifasciata extract. Corrosion Sci. 2007;49:1527–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiao-Ping W., Minhua S., Chen-Qing Y., Shi-Gang D., Rong-Gui D., Chang-Jian L. Study on effect of chloride ions on corrosion behaviour of reinforcing steel in simulated polluted concrete pore solutions by scanning micro-reference electrode technique. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021;895:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D., Yue Y., Xie Z., Mi T., Yang S., McCague C., Qian J., Bai Y. Chloride-induced depassivation and corrosion of mild steel in magnesium potassium phosphate cement. Corrosion Sci. 2022;206:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noor E.A. Temperature effects on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic solutions by aqueous extract of fenugreek leaves. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2007;2:996–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ekemini I., Onyewuchi A., Abosede J. Evaluation of performance of corrosion inhibitors using adsorption isotherm models: an overview. Chem. Sci. Int. J. 2017;18:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan S., Liang B., Zhao Y., Pehkonen S. Surface chemistry and corrosion behaviour of 304 stainless steel in simulated seawater containing inorganic sulphide and sulphate-reducing bacteria. Corrosion Sci. 2013;74:353–366. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venzlaff H., Enning D., Srinivasan J., Mayrhofer K.J.J., Hassel A.W., Widdel F., Stratmann M. Accelerated cathodic reaction in microbial corrosion of iron due to direct electron uptake by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Corrosion Sci. 2013;66:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murulana L.C., Kabanda M.M., Ebenso E.E. Vol. 5. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances; 2015. pp. 28743–28761. (Experimental and Theoretical Studies on the Corrosion Inhibition of Mild Steel by Some Sulphonamides in Aqueous HCl). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouklah M., Hammouti B., Lagranee M., Bentiss F. Thermodynamic properties of 2,5-bis (4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in normal sulphuric acid medium. Corrosion Sci. 2006;48:2831–2842. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jalab R., Saad M.A., Sliem M.H., Abdullah A.M., Hussein I.A. An eco-friendly quaternary ammonium salt as a corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in 5M HCl solution: theoretical and experimental investigation. Molecules. 2022;27:1–21. doi: 10.3390/molecules27196414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nesane T., Mnyakeni-Moleele S.S., Murulana L.C. Exploration of synthesized quaternary ammonium ionic liquids as unharmful anti-corrosives for aluminium utilizing hydrochloric acid medium. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04113. 1, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bashir S., Thakur A., Lgaz H., Chung I., Kumar A. Corrosion inhibition performance of Acarbose on mild steel corrosion in acidic medium: an experimental and computational study. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2020;45:4773–4783. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atkins P., De Paula J. ninth ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. Atkins' Physical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernandes C.M., de Mello M.V.P., dos Santos N.E., de Souza A.M.T., Lanznaster M., Ponzio E.L. Theoretical and experimental studies of a new aniline derivative corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acid medium. Mater. Corros. 2019;71:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verma C., Singh A., Pallikonda G., Chakravarty M., Quraishi M.A., Bahadur I., Ebenso E.E. Aryl sulfonamidomethylphosphonates as new class of green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in 1M HCl: electrochemical, surface and quantum chemical investigation. J. Mol. Liq. 2015;209:306–319. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amin M.A., Ibrahim M.M. Corrosion and corrosion control of mild steel in concentrated H2SO4 solutions by a newly synthesized glycine derivative. Corrosion Sci. 2011;53:873–885. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Azawi K.F., Mohammed I.M., Al-Baghdadi S.B., Salman T.A., Issa H.A., Al-Amiery A.A., Gaaz T.S., Kadhum A.A.H. Experimental and quantum chemical simulations on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by 3-((5-(3,5-dinitrophenyl)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)imino)indolin-2-one. Results Phys. 2018;9:278–283. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nwosu F.O., Muzakir M.M. Thermodynamic and adsorption studies of corrosion inhibition of mild steel using lignin from siam weed (Chromolaena odorata) in acid medium. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2016;7:1663–1673. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kwon S., Fan M., DaCosta H.F.M., Russell A.G., Berchtold K.A., Dubey M.K. William Andrew; New York: 2011. Coal Gasification and its Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Haddad M.A.M., Radwan A.B., Sliem M.H., Hassan W.M.I., Abdullah A.M. Highly efficient eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 5M HCl at elevated temperatures: experimental and molecular dynamics study. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40149-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sithuba T., Masia N.D., Moema J., Murulana L.C., Masuku G., Bahadur I., Kabanda M.M. Corrosion inhibitory potential of selected flavonoid derivatives: electrochemical, molecular-Zn surface interactions and quantum chemical approaches. Res.Eng. 2022;16:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bashir S., Lgaz H., Chung I., Kumar A. Effective green corrosion inhibition of aluminium using analgin in acidic medium: an experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020;208:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diki N., Coulibaly N.H., Kassi K.F., Trokourey A. Mild steel corrosion inhibition by 7-(ethylthiobenzimidazolyl) theophylline. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2021;11:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Akinbulumo O.A., Odejobi O.J., Odekanle E.L. Thermodynamics and adsorption study of the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by Euphorbia heterophylla L. extract in 1.5M HCl. Res. Mater. 2020;5:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Lateef H.M.A., El-Sayed A., Mohran H.S., Shilkamy H.A.S. Corrosion inhibition and adsorption behaviour of phytic acid on Pb and Pb-In alloy surfaces in acidic chloride solution. Int. J. Integrated Care. 2019;10:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thoume A., Elmakssoudi A., Left B.D., Achagar R., Irahal I.N., Dakir M., Azzi M., Zertoubi M. Dibenzylidenecyclohexanone as a new corrosion inhibitor of carbon steel in 1M HCl. J. Bio- Tibo- Corros. 2021;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiwari N., Mitra R.K., Yadav M. Corrosion protection of petroleum oil well/tubing steel using thiadiazolines as efficient corrosion inhibitor: experimental and theoretical investigation. Surface. Interfac. 2021;22:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dueke-Eze C.U., Madueke N.A., Iroha N.B., Maduelosi N.J., Nnanna L.A., Anadebe V.C., Chokor A.A. Adsorption and inhibition study of N-(5-methoxy-2-hydroxybenzylidene) isonicotinohydrazide Schiff base on copper corrosion in 3.5% NaCl. Egypt. J. Petrol. 2022;31:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sajadi G.S., Naghizade R., Zeidabadinejad L., Golshani Z., Amiri M., Hosseini S.M.A. Experimental and theoretical investigation of mild steel corrosion control in acidic solution by Ranunculus arvensis and Glycine max extracts as novel green inhibitors. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10983. 1, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma V., Kumar S., Bashir S., Ghelichkhah Z., Obot I.B., Kumar A. Use of Sapindus (reetha) as corrosion inhibitor of aluminium in acidic medium. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;5:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qiang Y., Zhang S., Tan B., Chen S. Evaluation of Ginkgo leaf extract as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor of X70 steel in HCl solution. Corrosion Sci. 2018;133:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bashir S., Lgaz H., Chung I.M., Kumar A. Potential of Venlafaxine in the inhibition of mild steel corrosion in HCl: insights from experimental and computational studies. Chem. Pap. 2019;73:2255–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Obot I.B., Obi-Egbedi N.O. Fluconazole as an inhibitor for aluminium corrosion in 0.1M HCl. Colloid. Surface. 2008;330:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guruprasad A.M., Sachin H.P., Swetha G.A., Prasanna B.M. Corrosion inhibition of zinc in 0.1M hydrochloric acid medium with clotrimazole: experimental, theoretical and quantum studies. Surface. Interfac. 2020;19:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goel R., Siddiqi W.A., Ahmed B., Hussan J. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in HCl by isolated compounds of Riccinus Communis (L.) J. Chem. 2010;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yildiz R. An electrochemical and theoretical evaluation of 4,6-diamino-2-pyrimidinethiol as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl solutions. Corrosion Sci. 2015;90:544–553. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mahalakshmi D., Hemapriya V., Subramaniam E.P., Chitra S. Synergistic effect of antibiotics on the inhibition property of aminothiazolyl coumarin for corrosion of mild steel in 0.5 M H2SO4. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;284:316–327. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shuyun C., Dan L., Hui D., Jinghui W., Hui L., Jianzhou G. Corrosion inhibition effects of a novel ionic liquid with and without potassium iodide for carbon steel in 0.5 M HCl solution: an experimental study and theoretical calculation. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;275:729–740. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al-Amiery A.A., Ahmed M.H.O., Abdullah T.A., Gaaz T.S., Kadhum A.A.H. Electrochemical studies of novel corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in 1 M hydrochloric acid. Results Phys. 2018;9:978–981. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuce A.O., Mert B.D., Kardas G., Yazici B. Electrochemical and quantum chemical studies of 2-amino-4-methyl-thiazole as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl solution. Corrosion Sci. 2014;83:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lai C.-Y., Huang W.-C., Weng J.-H., Chen L.-C., Chou C.-F. Impedimetric aptasensing using a symmetric Randels circuit model. Electrochim. Acta. 2020;337:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ansari K.R., Quraishi M.A., Singh A. Chromenopyridin derivatives as environmentally benign corrosion inhibitors for N80 steel in 15% HCl. J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017;22:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goel R., Siddiqi W.A., Ahmed B., Khan M.S., Chaubey V.M. Synthesis characterization and corrosion inhibition efficiency of N-C2{(2E)-2-[4-(dimethylamino) benzylidene] hydrazinyl} 2-oxo ethyl benzamide on mild steel. Desalination. 2010;263:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Solomon M.M., Umoren S.A., Udosoro I.I., Udoh A.P. Inhibitive and adsorption behaviour of carboxymethyl cellulose on mild steel corrosion in sulphuric acid solution. Corrosion Sci. 2010;52:1317–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mashuga M.E., Olasunkanmi L.O., Verma C., Sherif M., Ebenso E.E. Experimental and computational mediated illustration of effect of different substituents on adsorption tendency of phthalazinone derivatives on mild steel surface in acidic medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;305:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Daoud D., Douadi T., Issaadi S., Chafaa S. Adsorption and corrosion inhibition of new synthesized thiophene Schiff base on mild steel X52 in HCl and H2SO4 solutions. Corrosion Sci. 2014;79:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang L., He Y., Zhou Y., Yang R., Yang Q., Qing D., Niu Q. A novel imidazoline derivative as a corrosion inhibitor for P110 carbon steel in a hydrochloric acid environment. Petroleum. 2015;1:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ye Y., Zou Y., Jiang Z., Yang Q., Chen L., Guo S., Chen H. An effective corrosion inhibitor of N doped carbon dots for Q235 steel in 1M HCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2020;815:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Padhi S., Behera A. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2022. Agri-waste and Microbes for Production of Sustainable Nanomaterials. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sindhu R., Binod P., Pandey A. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2015. Industrial Biorefineries and White Biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Khan S.A., Khan S.B., Khan L.U., Farooq A., Akhtar K., Asiri M.A. Springer; New York: 2018. Handbook of Materials Characterization. [Google Scholar]

- 96.D'Angelo J. FT-IR determination of aliphatic and aromatic C-H contents of fossil leaf compressions. Latin Am. Yearbk. Chem. Educ. 2004;18:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Naghshbandi M.P., Moghimi H. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2020. Methods of Enzymology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.