Abstract

Optoacoustic tomography has been established as a powerful modality for preclinical imaging. However, efficient whole-body imaging coverage has not been achieved owing to the arduous requirement for continuous acoustic coupling around the animal. In this work, we introduce panoramic (3600) head-to-tail 3D imaging of mice with spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography (SVOT). The system combines multi-beam illumination and a dedicated head holder enabling uninterrupted acoustic coupling for whole-body scans. Image fidelity is optimized with self-gated respiratory motion rejection and dual speed-of-sound reconstruction algorithms to attain spatial resolution down to 90 µm. The developed system is thus highly suitable for visualizing rapid biodynamics across scales, such as hemodynamic changes in individual organs, responses to treatments and stimuli, perfusion, total body accumulation, or clearance of molecular agents and drugs with unmatched contrast, spatial and temporal resolution.

Keywords: Optoacoustic imaging, Photoacoustics, Whole-body imaging, Functional and molecular imaging, Biodistribution, Motion artefact correction

1. Introduction

Small animal mammalian models are extensively employed in preclinical research to study disease progression and monitor responses to therapies [1], [2]. Preclinical versions of computed tomography (CT) [3], [4], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [5], [6], and positron emission tomography (PET) [7], [8] and ultrasound (US) imaging [9], [10] are routinely used for whole-body imaging of mice and other rodents. Optical approaches are known to provide unique advantages for preclinical research, particularly in the context of functional and molecular imaging [11], [12], [13], [14]. Being a hybrid combination between optical imaging and ultrasound, optoacoustic (OA) imaging and tomography has matured as a powerful bioimaging modality [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] benefiting from the rich spectroscopic optical contrast, deep penetration into living mammalian tissues in the near-infrared spectral window, high spatial and temporal resolution [20].

In vivo OA imaging of small animals was first demonstrated almost two decades ago [21], [22]. Since then, a myriad of OAT embodiments based on different types of light delivery methods and US detection geometries have been proposed for whole-body imaging of small animals [23], [24], [25]. Examples include linear arrays translated and/or rotated around/along the animal [26], curved/arc shaped arrays rotated around the longitudinal axis of the mouse[27], concave arrays of cylindrically focused elements for cross-sectional imaging [28], [29], or sparse hemispherical arrays rotated around their central axis [30]. Densely populated spherical arrays have been shown to achieve real-time multi-wavelength three-dimensional (3D) imaging at the whole-organ scale [31], [32], essentially resulting in a five dimensional (5D, real-time volumetric spectroscopic) imaging capacity [33]. Spherical array geometry has also been employed for whole-body imaging of mice with spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography (SVOT). The method capitalizes on the large angular coverage of the array to provide volumetric images of large areas in mice, whereas the achievable temporal resolution scales with the imaged field of view (FOV) [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. A common challenge in whole-body imaging of mice with OA methods is the need for efficient (full) acoustic coupling around the animal, typically leading to suboptimal solutions with only partial coverage of thoracic and/or abdominal regions of the animal. Proper coverage of cranial regions is challenged by the need for full immersion of the animal, thus hindering the use of whole-body scanners for brain imaging [28], [39], [40].

In this work, we implemented rapid panoramic (360°) head-to-tail 3D imaging of mice to attain high resolution whole-body scans. The system employs multi-beam illumination and a dedicated head holder (Fig. 1B) enabling uninterrupted acoustic coupling around the animal, which further ensures that the animal can properly breathe while being immersed in water and maintained under constant anesthesia. Self-gated respiratory motion rejection and dual speed-of-sound correction algorithms were used to mitigate breathing motion artifacts and improve spatial resolution by accounting for acoustic mismatches between the mouse body and the surrounding coupling medium.

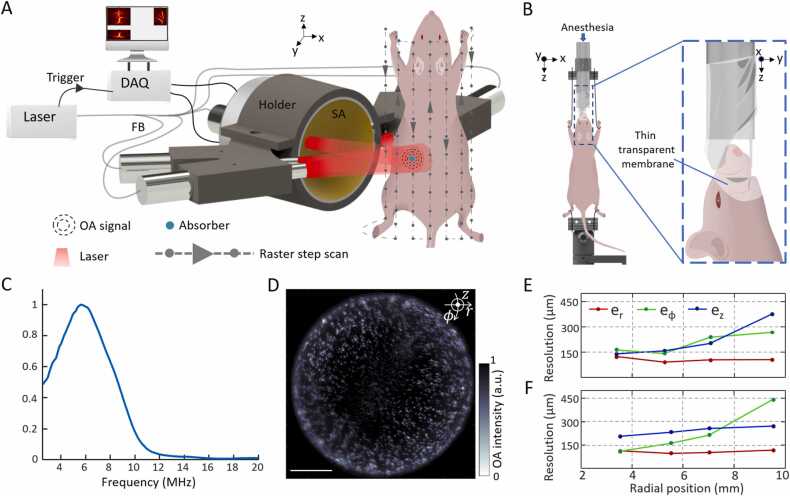

Fig. 1.

A. Schematic of the system for head-to-tail volumetric imaging of mice. SA: spherical array, FB: fiber bundle, DAQ: data acquisition system, OA: optoacoustic. B. Left: Custom-designed animal holder for SVOT. Right: Zoomed-in side view of the head holder. Nose and mouth of the animal are covered with a thin transparent membrane allowing it to breathe normally while inside water. C. Frequency response of the spherical array transducer for a point source (30 µm sphere) located at the center of spherical surface. D-F. Spatial resolution performance characterization using a tissue mimicking phantom containing randomly distributed 50 µm spheres. D. Reconstructed maximum intensity projection (MIP) of sphere phantom along z direction. The focus of the spherical array geometry was set at a distance of 6.9 mm from the rotational axis. Scalebar: 5 mm. E and F show dependence of the radial (), azimuthal (), and elevational () resolution on the radial position from the axis of rotation. The focus of the spherical array was set at 4.8 and 6.9 mm from the rotational axis in E and F respectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental set-up

The schematic of the newly designed SVOT experimental setup is depicted in Fig. 1A. An optical parametric oscillator (OPO)-based laser (SpitLight, Innolas Laser GmbH, Krailling, Germany) was used as an excitation source. It delivers < 10 ns duration pulses at a repetition rate of 10 Hz over a broad tunable wavelength range (680 – 1250 nm) with per-pulse energies up to ∼180 mJ. The light beam was guided through a custom-made fiber bundle (CeramOptec GmBH, Bonn, Germany) that bifurcates into five individual outputs with an equal number of fibers. All five outputs are placed at the same radial distance of 40 mm from the center of a custom-made spherical array. One of these outputs is inserted into a central cavity of the array, while the other four are arranged on both sides of the array facing the object at ± 64° and ± 76° angles (Fig. 1A). Each bundle output created a Gaussian illumination profile with a size of 10 mm at full width at half maximum (FWHM) on the mouse surface, resulting in an elongated ∼10 × 30 mm illumination pattern. The optical fluence was maintained below ANSI safety limits in all experiments [41]. A custom-made spherical array consisting of 512 individual piezoelectric sensor elements, having 7 mm2 area, 7 MHz central detection frequency, and 85% bandwidth was used to collect the OA responses. The effective transducer detection bandwidth, obtained using a 30 µm sphere, is shown in Fig. 1C covering a range from 2.6 to 8.6 MHz at FWHM. The elements are arranged on a hemispherical surface with a 40 mm radius and an angular coverage of 110° (0.61π solid angle). The OA signals are simultaneously digitized at 40 mega samples per second by a custom-made parallel data acquisition unit (DAQ, Falkenstein Mikrosysteme GmBH, Taufkirchen, Germany), which is triggered with the Q-switch output of laser, and transferred through 1 Gb/s Ethernet connection to a PC for storage and further processing. The PC further controls the data acquisition via custom-designed MATLAB interface (Version R2020b, MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA).

2.2. System characterization

To calibrate the relative position and orientation of the array with respect to its rotation axis, a gauge phantom consisting of a single 100 µm polyethylene microsphere (Cospheric Inc, Santa Barbara, USA) embedded in an agar cylinder (1.3% agar powder by weight) of 20 mm diameter was scanned before each experiment. The radial position, lateral shift, and axial rotation angle of the spherical array were determined by considering 18 angular locations (projections) of the array for each elevational (z axis) position. Following the initial calibration, a phantom consisting of a cloud of 50 µm polyethylene microsphere (Cospheric Inc, Santa Barbara, USA) was imaged to precisely characterize the spatial resolution of the system across the entire FOV. The spheres were randomly distributed in a 20 mm diameter cylindrical tissue mimicking (to mimic effective angular coverage) phantom. It was made of agar (1.3% agar powder by weight) containing black India ink and 1.2% by volume of Intralipid to simulate a background absorption coefficient of μa = 0.23 cm−1 and a reduced scattering coefficient of μs’ = 10 cm−1. These correspond to typical (average) values in biological tissues at the excitation wavelength used for the phantom experiments (800 nm). The sphere phantom was scanned in step-wise motion of the spherical array detector together with the five outputs of the fiber bundle along 18 projections covering 3600 and six translational positions along z-axis in steps of 2 mm. The position of the spherical array was controlled using motorized stages that can be translated in the vertical (z) direction and rotated in the azimuthal (ϕ) direction (RCP2-RGD6c-I-56 P-4–150-P1-S-B, RCP2-RTCL-I-28 P-30–360-P1-N, IAI Inc., Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan). To improve accuracy, the acquired signals were averaged 50 times for each scanning position. To evaluate the dependence of the spatial resolution on the radial position of the array, two different scans were performed with the focus of the spherical array positioned at a distance of 4.8 mm and 6.9 mm from the rotation axis. The motor positions were controlled using the MATLAB-based interface.

2.3. Whole body in vivo imaging

All in vivo animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the Swiss Federal Act on Animal Protection and with the approval of the Cantonal Veterinary Office in Zurich. Female athymic nude-Foxn1nu mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (4% volume ratio for induction and 1.5% volume ratio during experiments; Provet AG, Switzerland) in an oxygen/air mixture (100/400 mL/min). The animals were placed in a steady position using a custom-made animal holder with both fore and hind paws fixed (Fig. 1B, left). A transparent thin membrane was employed for covering the nose and mouth of the mice allowing it to freely breath gas anesthesia with the rest of the body fully submerged in water (Fig. 1B, right). The mice were then carefully immersed inside a water tank so that the water level covered the whole head. The water temperature was stabilized at 36 °C throughout the experiments using a feedback-controlled heating stick throughout the experiments. The whole body of the mice was scanned in a stop-and-go manner covering 3600 in 9 angular projections and in steps of 2 mm in the vertical direction.

2.4. Signal processing, image reconstruction

For in vivo image reconstruction, a pre- processing motion rejection algorithm was employed based on multi-frame acquisition of time-resolved OA signals with the spherical array transducer [42]. At each position of the array, 20 frames (1 frame = 1 laser pulse) were acquired. Each recorded frame comprised of a sinogram matrix with rows corresponding to 1005 time-samples of each signal and columns representing 512 channels (elements) of the array. The 20 frames were subsequently rearranged into a 2D matrix containing 1005 × 512 rows and 20 columns, representing the entire sequence of frames acquired at a single position of the array transducer. An autocorrelation matrix of all pairs of frames was then computed. Clustering of frames was subsequently done by applying the second order k-means method to the matrix of correlation coefficients. Then 20 frames were divided into two sets based on predetermined knowledge of the characteristic physiology of the animal under anesthesia. After rejecting frames afflicted with motion, the remaining frames were then averaged. All these steps were repeated at each scanning position. After motion-rejection, the time-resolved OA signals of the selected frames were then band pass filtered between 0.1 and 12 MHz and deconvolved with the impulse response of the array sensing elements [43]. Image reconstruction of individual volumetric frames was carried out with a graphics processing unit (GPU) implementation of back-projection (BP) reconstruction technique with each US array element split into 16 sub-elements for mitigating image artifacts related to spatial undersampling [37]. An average speed of sound (SOS) of 1480 m/s and 25 µm voxel resolution was used for phantom images, whilst two SOSs with 100 µm voxel resolution were used instead for in vivo images. Whole-body 3D mouse images were obtained by stitching individual reconstructed volumes at each position of the array by means of the Icmax compounding technique [37], [38].

2.5. Dual speed-of-sound correction for in vivo volumetric images

The acoustic impedance mismatch between the animal and surrounding coupling medium (water) commonly results in low image fidelity when the reconstruction is performed by assuming a uniform SOS. Typically, the SOS in water at room temperature is ∼1490 m/s while the average SOS in biological tissues is ∼1540 m/s. To account for SOS heterogeneities between water and biological tissues, we employed dual SOS-based back-projection (BP) reconstruction algorithm for rendering volumetric 3D images [44]. For this, a volumetric 3D image with uniform SOS corresponding to the SOS in water is reconstructed at each position of the spherical array. Next, we created a volumetric mask delineating the biological tissue volume and the water medium in 3D. Then, we assigned different values of SOS for water (1520 m/s at 360 C) and the segmented region. The value of the SOS within the mouse was determined as that corresponding to the image with highest contrast rendered using the dual-SOS-based BP algorithm. Note that dual SOS algorithm was applied after correcting for motion artifacts using self-gated respiratory motion rejection algorithm.

Initially, the dual SOS correction algorithm was validated in a phantom consisting of a cloud of 50 µm spheres distributed over 20 mm cylinder. The phantom was made of agar (1.3% agar powder by weight) containing glycerol in 2:1 ratio, with small percentage of black India ink and Intralipid to simulate background absorption and scattering. Note that in order to mimic SOS differences inside tissue and coupling medium, glycerol was added into agar resulting in different SOS (∼ 1655 m/s) inside the phantom compared to surrounding water (∼1477 m/s @ 18.4 0C).

3. Results

3.1. Spatial resolution characterization

The system’s spatial resolution was characterized by scanning a cloud of 50 µm spheres distributed across a tissue mimicking phantom (Fig. 1D). The reconstructed sphere size remained nearly isotropic along the three cylindrical axes, namely, the radial , azimuthal , and elevational (Fig. 1E and F). After deconvolving the actual microsphere diameter from their estimated FWHM in the images [25], the radial resolution performance remained nearly isotropic and constant throughout the imaged volume in the range between 90 and 125 µm. Similar behavior was observed for azimuthal resolution, although stronger dependence exists on the position of the geometric center of the spherical array relative to the axis of rotation. Note that FWHM was calculated after fitting to Gaussian curve in all axes. Elevational resolution exhibits the most significant variations across the imaged volume while also strongly depending on the position of the spherical array with respect to the rotation axis. Thus, depending on the total size of the imaged object, the spherical array position must be carefully chosen to obtain the best performance in the desired region of interest (ROI). Certain deviations from an isotropic spatial resolution are generally anticipated across such a large FOV due to the directivity of the individual array elements along the scanning trajectory.

3.2. Volumetric dual speed-of-sound correction

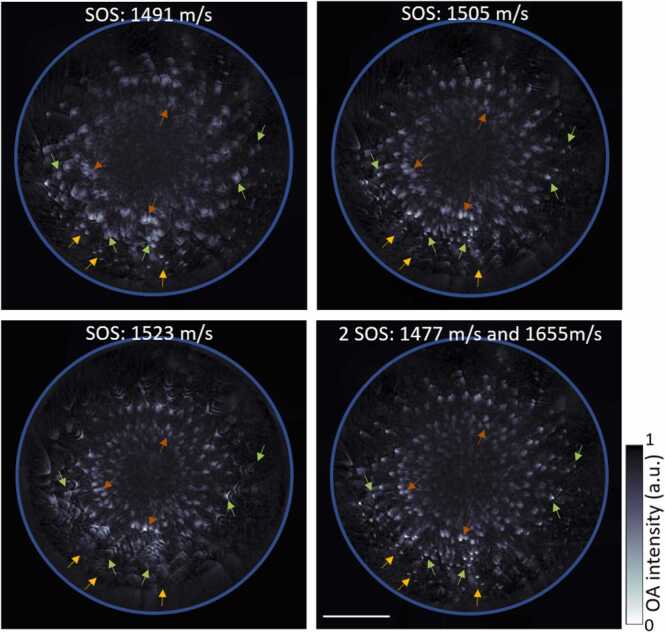

OA reconstructions based on uniform SOS assumptions may generally result in degraded spatial resolution and other artefacts, thereby leading to diminished image fidelity. As a first order correction, imaging performance can be enhanced by considering 2 different SOS values in water (coupling medium) and inside tissue, as has previously been demonstrated for cross-sectional (2D) OA imaging systems [45]. Here, we have adapted the dual SOS algorithm for volumetric (3D) image data. The maximum intensity projections (MIPs) along the z direction of the images reconstructed considering a uniform SOS clearly show blurring of the spheres reconstructed at different depths (Fig. 2, @SOS: 1491, 1505, and 1523 m/s). For instance, while the peripherally located spheres are accurately reconstructed as point targets with a uniform SOS of 1491 m/s (yellow arrows), blurring is produced at deeper locations for this particular SOS value (green arrows) with the spheres also deformed in shape at the center of the phantom (brown arrows). On the other hand, OAT reconstruction with uniform SOS values of 1505 resulted in spheres optimally reconstructed only at relatively shallow depths (green arrows) or otherwise at the center of the phantom (brown arrows) for SOS of 1523 m/s. The dual SOS reconstruction algorithm enabled accurately reconstructing all the spheres as point targets across the entire phantom (Fig. 2, @2SOS: 1477 and 1655 m/s).

Fig. 2.

2-SOS correction for volumetric 3D data. Differences between single SOS and dual SOS can be seen with arrows pointing to the spheres across different depths. Yellow, green, and brown arrows pointing to the spheres at the periphery, closer to periphery and closer to the center of the phantom respectively. Scale bar: 5 mm.

3.3. Head-to-tail in vivo whole-body mouse imaging

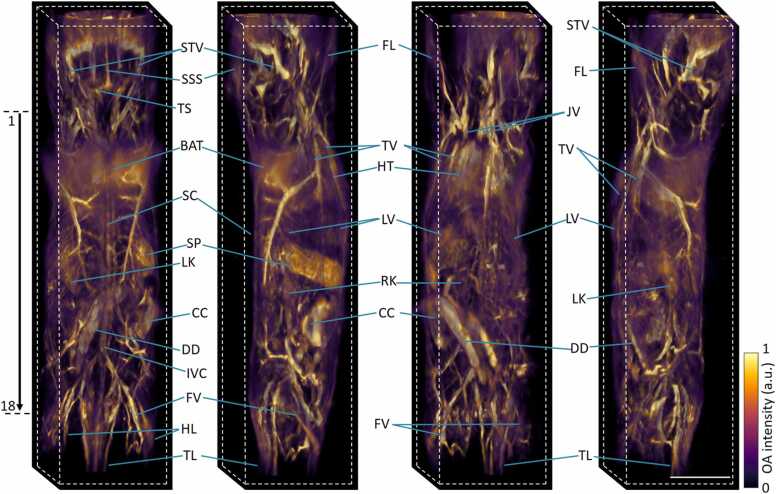

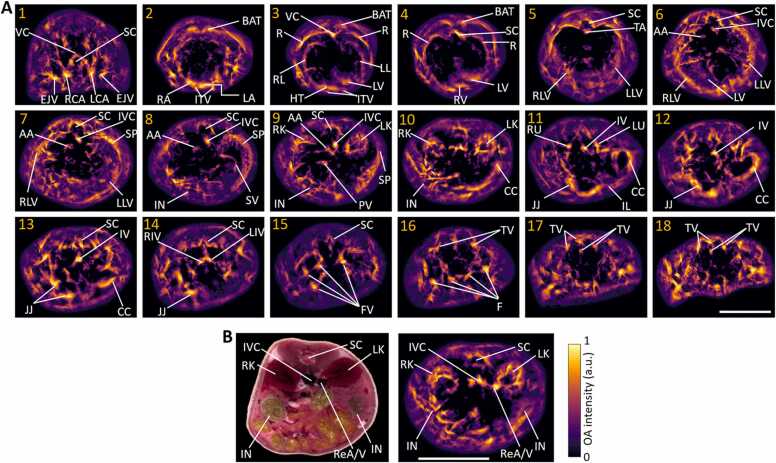

The multi-beam illumination strategy along with the custom-designed breathing mask have enabled here the full panoramic (3600) scans of mice covering from head to tail in a single setup with excellent image contrast and nearly isotropic spatial resolution (Fig. 3). Main organs like brain, heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, spinal cord, intestines, brown adipose tissue, fore and hind limbs, tail and surrounding major blood vascular system are clearly discernible with high resolution and contrast. Fine structures such as superior sagittal and transverse sinuses, superior temporal veins, jugular veins, inferior vena cava, thoracic and femoral vessels can be easily observed. A rotational 3D view of the whole-body mouse volume can be best visualized in Supplementary Movie 1. Note that the full tomographic angular coverage of the system facilitates visualization of deep anatomical structures. These are mainly concealed by the MIP views, which commonly emphasize superficial signals due to depth-dependent light attenuation in tissues. The reduced signal intensity is more clearly evinced in the cross-sectional slices at various anatomical locations (marked 1–18 in Fig. 3) ranging from the neck to the tail regions shown in Fig. 4. Fine anatomical and vascular structures were clearly discernible, including vertebral column, right and left carotid arteries, external jugular veins, both atria and ventricles of the heart, partial right and left lungs, right, medial and left lobes of liver, thoracic and abdominal aortas, portal vein, splenic vein, cecum, ileum, jejunum, right and left kidneys, right and left ureters, iliac veins and tail veins. Note that light fluence correction and Frangi filtering [46] were applied for all cross-sectional slices (0.1 mm thickness) to showcase actual penetration depth and enhance visibility of the vascular network. Negative image values were thresholded to zero, A fly-through movie of the cross-sectional slices over the entire mouse, from head-to-tail, is further available in Supplementary Movie 2. Although most of the cross-sections contain good contrast across all depths, visibility is limited to superficial layers in some areas due to the strong light absorption by highly vascularized organs (such as liver, spleen and lungs) as well as acoustic distortions introduced by the air-containing lungs.

Fig. 3.

In vivo head-to-tail 3D imaging of a mouse. MIPs of the rendered volume are shown (left to right) from the back, right, left-front, left views. STV: superficial temporal vein, SSS: superior sagittal sinus, TS: transverse sinus, BAT: brown adipose tissue, SC: spinal cord, SP: Spleen, LV: liver, LK: left kidney, RK: right kidney, FL: fore limb, HL: hind limb, TL: tail, HT: heart, JV: jugular vein, TV: thoracic vessels, CC: caecum, DD: duodenum, IVC: inferior vena cava, FV: femoral vessels. A rotational video is further available in Supplementary Video 1. Scalebar: 1 cm.

Fig. 4.

Cross-sectional slice images of a mouse extracted from the whole-body volume image. A. The shown 18 slices (0.1 mm thickness each) cover the entire length from the neck region to the tail (see the arrow in the leftmost image in Fig. 3). VC: vertebral column, SC: spinal cord, EJV: external jugular vein, RCA: right common carotid artery, LCA: left common carotid artery, BAT: brown adipose tissue, ITV: internal thoracic veins, HT: heart, RA: right atrium, LA: left atrium, RV: right ventricle, LV: left ventricle, RL: right lung, LL: left lung, TA: thoracic aorta, R: ribs, RLV: right lobe of liver, LLV: left lobe of liver, LV: liver, IVC: inferior vena cava, AA: abdominal aorta, SP: spleen, SV: splenic vein, IN: intestines, LK: left kidney, RK: right kidney, PV: portal vein, CC: cecum, RU: right ureter, LU: left ureter, JJ: jejunum, IL: ileum, IV: iliac vein, RIV: right common iliac vein, LIV: left common iliac vein, FV: femoral veins, TV: tail veins. B. Cryoslice image (left) showing major organs like left and right kidneys, intestines, and surrounding blood vessels like inferior vena cava and renal artery/vein (ReA/V), corresponding reconstructed image (right). Scalebar: 1 cm.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100480.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie S1..

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.pacs.2023.100480.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Movie S2..

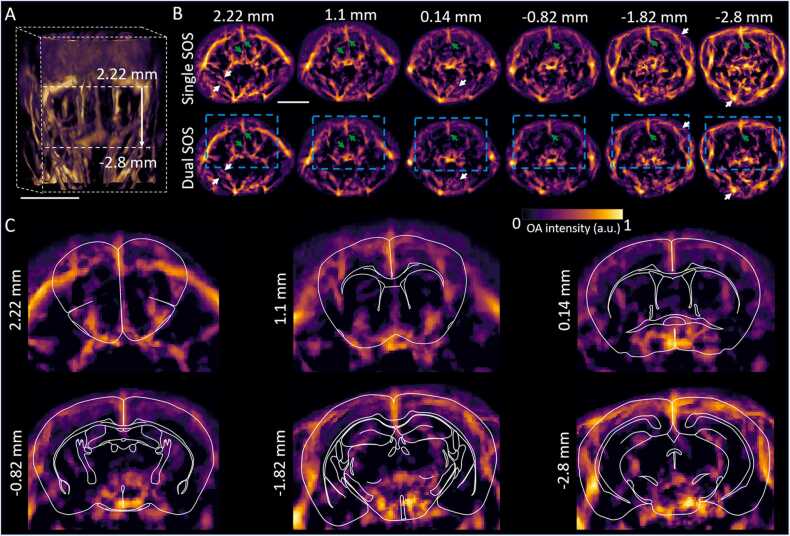

3.4. Brain imaging performance with the dual SOS algorithm

We investigated in detail the efficiency of volumetric reconstructions with the dual SOS algorithm for mouse whole-brain imaging (Fig. 5A). In particular, whole head cross-sectional slices (shown with respect to bregma position) reconstructed with uniform SOS and dual SOS show clear differences in the reconstructed image fidelity. For instance, shape of the central sagittal vessels (green arrows in Fig. 5B) appears enlarged and distorted when considering a single SOS, while having a focused shape in the images reconstructed with the dual SOS algorithm. The differences become more prominent in deeper regions. As evinced in the zoomed-in slices of the brain area, deeply seated anatomical structures across the entire mouse brain are revealed with the method (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Whole head/brain imaging with volumetric dual SOS correction. A. 3D- view of the whole head of the mice. Dotted lines indicate the region of the brain considered. Scalebar: 1 cm. B. Comparison of single and dual SOS reconstructed slices (0.1 mm thickness each) at various anatomical locations with respect to the bregma point. Arrows indicate the main differences. Scalebar: 5 mm. C. Zoomed-in areas (indicated by blue dotted boxes in panel B) showing whole brain mapping with the dual SOS reconstructions. Atlas-based outlines of the main brain areas are overlaid for anatomical reference.

4. Discussions and conclusions

The developed approach allowed for first panoramic head-to-tail noninvasive optoacoustic imaging of mice with full 3600 coverage. The system employed multi beam illumination together with a newly engineered mouse holder, which provided comfort to the animal to properly breathe while being fully immersed in water. A thin transparent membrane covering the nose and mouth of the animal acted as a breathing mask providing unperturbed anesthesia. The system has thus enabled unrestricted head-to-tail scans, covering cranial, thoracic and abdominal regions in a single set up. We further employed multi-beam illumination to expand the achievable FOV for each position of the spherical array. Streak artifacts that are commonly associated with spatial tomographic undersampling were mitigated by means of the 16x-sub-element reconstruction. Icmax compounding technique was used to efficiently stitch the individual reconstructed volumes at each position of the spherical array to obtain panoramic 3D image of the whole mouse. Self-gated respiratory motion rejection algorithm and volumetric dual speed-of-sound correction further enabled averting motion artifacts and increased achievable resolution by accounting for acoustic heterogeneities between mouse and surrounding water. As a result, whole-head/brain as well as major organs like heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, and major vasulature could be visualized across whole body of a mouse with superior image fidelity in 3D. Recently, whole-body (head-to-tail) imaging of mice was performed with a rotational hemispherical detector array system [47]. However, this was done post mortem and only neck-to-tail imaging with limited angular coverage could be achieved in vivo. Alternatively, whole-body imaging can be realized via scanning of a circular array transducer whose elements are cylindrically focused into a common plane [46]. While such configurations achieve high quality cross-sectional (2D) images, their whole-body (volumetric) imaging performance is compromised by the inferior and highly anisotropic resolution along the vertical (elevational) direction due to cylindrical focusing. As a result, no accurate images of arbitrarily-oriented vascular networks can be achieved with cross-sectional imaging systems, which can be partially compensated by applying Frangi-based (vesselness) filtering at the expense of appearance of vessel-like networks that do not correspond to actual structures in the mouse [48].

The devised SVOT system can be operated in different scanning modes with a trade-off between acquisition time and achievable image quality that must be considered depending on the application. The step-and-go scanning method can be employed for panoramic visualization of head-to-tail morphological information with superior spatial resolution, signal-to-noise performance, image quality and depth. This however requires ∼12 min acquisition time with 10 Hz laser pulse repetition rate and 20 frames acquired at each position of the array scanning in steps of 2 mm in vertical (z) and 400 in azimuthal (ϕ) directions. Naturally, the acquisition time can be reduced with higher laser repetition rates. Alternatively, continuous overfly scanning of the array along the same trajectory at a peak velocity of 80 mm/s in z and in steps of 400 in ϕ enables covering the same volume of mouse in a total scan time of ∼37 s[36]. Rapid overview 3D scans can also be acquired within 2 s with a single-sweep approach [37]. The spherical array system has previously been shown capable of rapid volumetric imaging with 3D frame rates exceeding 100 Hz [49], albeit the effective FOV is limited to ∼1 cm3 in this case thus restricting the imaging to a single organ level.

In summary, the introduced approach greatly expands the preclinical optoacoustic imaging toolset by achieving panoramic (3600) 3D visualization from head-to-tail in a single set up. The developed system is highly suitable for visualizing rapid biodynamics across scales, such as label-free imaging of hemodynamics in multiple organs, monitoring responses to treatments and stimuli, tracking perfusion, total body accumulation and clearance dynamics of molecular agents and drugs with unmatched contrast, spatial and temporal resolution.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

S.K.K., X.L.D.B., D.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. S.K.K.: Investigation, Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. X.L.D.B.: Software, Resources, Formal analysis. M.R.: Investigation. D.R.: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by European Research Council under grant agreement ERC-2015-CoG-682379.

Biographies

Sandeep Kumar Kalva is working as a postdoctoral fellow in Prof. Daniel Razansky’s group at the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology and the Institute for Biomedical Engineering, University of Zürich and ETH Zürich, Switzerland since November, 2019. He earned Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering from the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore in the year 2019. His research is focused on development and application of new optoacoustic imaging systems for various biomedical applications in cancer theranostics. He has published 27 peer-reviewed journal publications, 11 conference proceedings and 1 book chapter.

Xosé Luís Deán-Ben has been working in the field of optoacoustic (photoacoustic) imaging since 2010. He currently serves as a senior scientist and group leader at the Institute for Biomedical Engineering and Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology (University of Zürich and ETH Zürich). Previously, he received post-doctoral training at the Institute of Biological and Medical Imaging (Helmholtz Zentrum Munich). He contributed both to the development of new optoacoustic systems and processing algorithms as well as to the demonstration of new bio-medical applications in cancer, cardiovascular biology and neuroscience. He has co-authored more than 70 papers in peer-reviewed journals on the topic.

Michael Reiss finished his professional development as Biological Laboratory Technician at Helmholtz Zentrum München in 2015. Afterwards he joined Prof. Daniel Razansky's lab in Munich and eventually in Zürich.

Daniel Razansky holds the Chair of Biomedical Imaging with double appointment at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Zürich and Department of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, ETH Zürich. He earned Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering and M.Sc. in Electrical Engineering from the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology and completed postdoctoral training in bio-optics at the Harvard Medical School. Between 2007 and 2018 he was the Director of Multi-Scale Functional and Molecular Imaging Lab and Professor of Molecular Imaging Engineering at the Technical University of Munich and Helmholtz Center Munich. His Lab pioneered and commercialized a number of imaging technologies, among them the multi-spectral optoacoustic tomography and hybrid optoacoustic ultrasound imaging. He has authored over 250 peer-review journal articles and holds 15 patented inventions in bio-imaging and sensing. He is the Founding Editor of the Photoacoustics journal and serves on Editorial Boards of a number of journals published by Springer Nature, Elsevier, IEEE and AAPM. He is also an elected Fellow of the IEEE, OSA and SPIE.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kiessling F., Pichler B.J. Springer Science & Business Media; 2010. Small Animal Imaging: Basics And Practical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker M. The whole picture. Nature. 2010;463(7283):977–979. doi: 10.1038/463977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heyden B., et al. Virtual monoenergetic micro-CT imaging in mice with artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaker K., et al. Phase-contrast X-ray tomography resolves the terminal bronchioles in free-breathing mice. Commun. Phys. 2021;4(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin R., et al. Carbonized paramagnetic complexes of Mn (II) as contrast agents for precise magnetic resonance imaging of sub-millimeter-sized orthotopic tumors. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29586-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhan S., et al. Targeting NQO1/GPX4-mediated ferroptosis by plumbagin suppresses in vitro and in vivo glioma growth. Br. J. Cancer. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01800-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim D.-Y., et al. In vivo imaging of invasive aspergillosis with 18F-fluorodeoxysorbitol positron emission tomography. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain radio-probe: a non-invasive approach for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 mapping in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00809-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., et al. Augmented ultrasonography with implanted CMOS electronic motes. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiles B., et al. Performance benchmarking of microbubble-localization algorithms for ultrasound localization microscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022;6(5):605–616. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00824-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enninful A., Baysoy A., Fan R. Unmixing for ultra-high-plex fluorescence imaging. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser A.K., et al. A hybrid open-top light-sheet microscope for versatile multi-scale imaging of cleared tissues. Nat. Methods. 2022;19(5):613–619. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01468-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchard M.B., et al. Swept confocally-aligned planar excitation (SCAPE) microscopy for high-speed volumetric imaging of behaving organisms. Nat. Photonics. 2015;9(2):113–119. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos‐Coquillat A., et al. Goat milk exosomes as natural nanoparticles for detecting inflammatory processes by optical imaging. Small. 2022;18(6) doi: 10.1002/smll.202105421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beard P. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus. 2011;1(4):602–631. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manohar S., Razansky D. Photoacoustics: a historical review. Adv. Opt. Photonics. 2016;8(4):586–617. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das D., et al. Another decade of photoacoustic imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021;66(5):05TR01. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/abd669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deán-Ben X.L., et al. Advanced optoacoustic methods for multiscale imaging of in vivo dynamics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46(8):2158–2198. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00765a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deán‐Ben X.L., Razansky D. Optoacoustic imaging of the skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021;30(11):1598–1609. doi: 10.1111/exd.14386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L.V., Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335(6075):1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruger R.A., et al. Thermoacoustic computed tomography using a conventional linear transducer array. Med. Phys. 2003;30(5):856–860. doi: 10.1118/1.1565340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., et al. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(7):803–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia J., Wang L.V. Small-animal whole-body photoacoustic romography: a review. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2014;61(5):1380–1389. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2283507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeon M., Kim J., Kim C. Multiplane spectroscopic whole-body photoacoustic imaging of small animals in vivo. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016;54(2–3):283–294. doi: 10.1007/s11517-014-1182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma R., et al. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) scanner for whole-body small animal imaging. Opt. Express. 2009;17(24):21414–21426. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.021414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gateau J., et al. Three‐dimensional optoacoustic tomography using a conventional ultrasound linear detector array: Whole‐body tomographic system for small animals. Med. Phys. 2013;40(1) doi: 10.1118/1.4770292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brecht H.-P.F., et al. Whole-body three-dimensional optoacoustic tomography system for small animals. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14(6) doi: 10.1117/1.3259361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia J., et al. Whole-body ring-shaped confocal photoacoustic computed tomography of small animals in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012;17(5) doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.050506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razansky D., Buehler A., Ntziachristos V. Volumetric real-time multispectral optoacoustic tomography of biomarkers. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6(8):1121–1129. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv J., et al. Hemispherical photoacoustic imaging of myocardial infarction: in vivo detection and monitoring. Eur. Radiol. 2018;28(5):2176–2183. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottschalk S., et al. Rapid volumetric optoacoustic imaging of neural dynamics across the mouse brain. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3(5):392–401. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deán-Ben X.L., Razansky D. Functional optoacoustic human angiography with handheld video rate three dimensional scanner. Photoacoustics. 2013;1(3–4):68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gottschalk S., et al. Noninvasive real-time visualization of multiple cerebral hemodynamic parameters in whole mouse brains using five-dimensional optoacoustic tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2015;35(4):531–535. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehm T.F., et al. In vivo whole-body optoacoustic scanner with real-time volumetric imaging capacity. Optica. 2016;3(11):1153–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deán-Ben X.L., et al. Spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography visualizes multi-scale dynamics in mice. Light.: Sci. Appl. 2017;6(4) doi: 10.1038/lsa.2016.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ron A., et al. Flash scanning volumetric optoacoustic tomography for high resolution whole‐body tracking of nanoagent kinetics and biodistribution. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalva S.K., Dean-Ben X.L., Razansky D. Single-sweep volumetric optoacoustic tomography of whole mice. Photonics Res. 2021;9(6):899–908. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalva S.K., et al. Rapid Volumetric Optoacoustic Tracking of Nanoparticle Kinetics across Murine Organs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021 doi: 10.1021/acsami.1c17661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L., et al. Single-impulse panoramic photoacoustic computed tomography of small-animal whole-body dynamics at high spatiotemporal resolution. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017;1(5):0071. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gottschalk S., et al. Noninvasive real-time visualization of multiple cerebral hemodynamic parameters in whole mouse brains using five-dimensional optoacoustic tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2015;35(4):531–535. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers ANSI Z136.1–2007 (American National Standards Institute, Inc., New York, NY, 2007).

- 42.Ron A., et al. Self-gated respiratory motion rejection for optoacoustic tomography. Appl. Sci. 2019;9(13):2737. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rebling J., et al. Optoacoustic characterization of broadband directivity patterns of capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016;22(4) doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.22.4.041005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deán-Ben X.L., Özbek A., Razansky D. Accounting for speed of sound variations in volumetric hand-held optoacoustic imaging. Front. Optoelectron. 2017;10(3):280–286. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deán‐Ben X.L., Ntziachristos V., Razansky D. Effects of small variations of speed of sound in optoacoustic tomographic imaging. Med. Phys. 2014;41(7) doi: 10.1118/1.4875691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merčep E., et al. Transmission–reflection optoacoustic ultrasound (TROPUS) computed tomography of small animals. Light.: Sci. Appl. 2019;8(1):18. doi: 10.1038/s41377-019-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asao Y., et al. In vivo label-free observation of tumor-related blood vessels in small animals using a newly designed photoacoustic 3D imaging system. Ultrason. Imaging. 2022;44(2–3):96–104. doi: 10.1177/01617346221099201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longo A., et al. Assessment of hessian-based Frangi vesselness filter in optoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2020.100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Özbek A., Deán-Ben X.L., Razansky D. Optoacoustic imaging at kilohertz volumetric frame rates. Optica. 2018;5(7):857–863. doi: 10.1364/OPTICA.5.000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.