Abstract

Objectives:

The surgery for dialysis access has changed over the past 38 years. In the 1980s and 1990s, prosthetic grafts were the most common form of access. Then, autogenous fistulae had a rebirth due to their durability and decreased complications. The continued expansion of the dialysis population, coupled with the paucity of adequate superficial veins in many patients, required other techniques of dialysis access such as tunneled dialysis catheters, and more complex surgery on deeper veins.

Methods:

This study of one surgeon’s practice over 38 years mirrors the extensive changes in dialysis access. The changes in surgical technique, interventional procedures, and approaches were documented and evaluated.

Results:

During the 38-year period, there were 1531 autogenous fistulae, 409 prosthetic grafts, and 1624 tunneled dialysis catheters placed for access. The first 20 years had 130 autogenous fistulae with 302 prosthetic grafts, while in the last 10 years there were 740 fistulae and only 17 prosthetic grafts. Prosthetic grafts were not salvageable for a long term with exposure, infection, and persistent bleeding. Autogenous fistulae were best salvaged with autogenous tissue rather than prosthetic material. Interventional procedures were most valuable in stenting high-grade stenosis centrally and dilating areas of recurrent stenosis. They were not helpful in treatment of large aneurysms or as a long-term solution for persistent and/or massive bleeding.

Conclusion:

Dialysis access has progressed back to autogenous fistula. This may require longer use of tunneled dialysis catheters, and more surgical procedures, but the construction of an autogenous fistula can be achieved in many dialysis patients.

Keywords: Dialysis access, autogenous dialysis access, complications of hemodialysis access

Introduction

The surgery for dialysis access has gone through many changes, throughout its history. The first attempt to provide a reusable form of hemodialysis was the use of an external cannula, which provided easy access to the venous and arterial system (Scribner shunt) in the early 1960s.1 This innovation initiated a new phase of clinical hemodialysis and avoided repeated cannulations. Access surgery then progressed to the autogenous fistula (the Brescia–Cimino fistula) for chronic dialysis access.2

As hemodialysis machines were refined and improved, the missing link to provide this modality to all patients with significant renal failure was a means to provide chronic hemodialysis access. Unfortunately, adequate, usable cephalic veins and radial arteries limited the use of the Brescia–Cimino fistula. In addition, the early use of this autogenous fistula was hampered by limited vascular surgical experience and poor maturation of marginal veins. It was at this time in the early 1970s that a multitude of prosthetic grafts were produced to fill this need. During this phase of dialysis access surgery, the Cimino fistula was still used, but the vast majority of procedures for hemodialysis access were dominated by the insertion of prosthetic grafts for arteriovenous conduits. The use of prosthetic grafts was a very important adjunct in the early days of hemodialysis access. It allowed an option for patients with limited venous access and obviated the need for long-term use of poor-quality dialysis catheters with resultant sepsis and inadequate hemodialysis.

The advent of the National Kidney Foundation—Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-DOQI) for hemodialysis in 1997 began to advocate the construction of autogenous fistulae as the access of choice for hemodialysis.3 This, coincidentally and, perhaps, causally, occurred at a time when the complications and increased hospitalizations due to thrombosis and infections of prosthetic grafts became especially prominent. In fact, for a period in the late 1990s, the most common cause for admission to a hospital for a nephrology patient was a complication with their hemodialysis prosthetic graft.4 In addition, the continued improvement in the medical treatment of hypertension, cardiac disease, and diabetes mellitus in chronic renal failure patients showed significant increases in life expectancy.5

It was the combination of all these events, which mandated and supported a new approach to the chronic renal failure patient on hemodialysis. Both the Fistula First Initiative and NKF-DOQI for hemodialysis advocated the use of autogenous fistulae to lessen the morbidity and mortality so frequently seen with prosthetic grafts.

As in the earlier phases and changes in surgical hemodialysis access, the number of patients requiring hemodialysis continued to increase, which mandated newer approaches to satisfy this demand. This time, however, the emphasis was on the construction of autogenous fistulae rather than the continued use of prosthetic grafts. In addition, more vascular surgeons and specialists in dialysis access provided newer techniques of autogenous access. The construction of brachiocephalic fistula, mid-forearm radiocephalic fistula, basilic vein transposition, and brachial vein transposition offered new areas for the construction of autogenous fistula. These endeavors were assisted by the continued and increased use of tunneled dialysis catheters, which provided time for maturation of accesses and multiple attempts to construct a functional and lasting autogenous access. The purpose of this article is to present one surgeon’s experience in the continually developing and changing field of dialysis access through a 38-year period (1983–2021).

Methods

This was a retrospective study over a 38-year period and involved no risk to patients. It was done in conjunction with the Carilion Clinic’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). All ethical standards were followed, and the requirement of informed consent was waived. It was determined that the research involved no risk to subjects.

This article is a review of all patients treated and operated on by one of the two surgeons over a 38-year period (1983–2021). All patients referred to the surgeon requiring dialysis access, both acute and chronic were included. The vast majority of the surgeries were performed by one surgeon (SLH). The fact that almost all the surgeries were done by one surgeon over the 38-year study negates any variability of surgical technique or treatment choices in possibly influencing results. Catheter placement and surgical treatment for access complications were also addressed and treated. Interventional treatments were referred to other specialists in dialysis access through the years studied. When necessary and indicated, femoral, subclavian, and internal jugular percutaneous catheters were used for urgent and immediate dialysis access. Over the last 25 years of this study, tunneled dialysis catheters were used to expedite discharge to an outpatient setting. In addition, they have been used for patients with multiple medical issues including difficult access situations, maturation of accesses, and in those renal failure patients who were too sick to undergo any operative intervention.

Being a tertiary care referral center and a center for dialysis, many patients were referred in with complications, failed accesses, infections, and massive bleeding issues. There were many patients who were referred for peritoneal dialysis catheter placement, but these patients were not included in this study unless they required conversion to hemodialysis.

The changes in types of vascular access, as well as the different types of complications and their treatments were documented and followed through the years.

All patients considered for operative intervention were completely evaluated by the vascular lab. In the early part of period 1, this was fairly innovative. However, over the next 30 years, it became routine and important in choosing the best sites for fistula construction as well as graft placement and catheter insertion. The duplex scan represented in this study and in the world of dialysis access is a significant advancement in the successful use of veins and arteries in the construction of hemodialysis access.

In evaluating patients for possible fistula construction, veins and arteries chosen were always at least 2.0 mm in diameter. They were always evaluated postoperatively, when possible, prior to their use for dialysis and were marked. In the later years, if there was a stenosis picked up on a postoperative vascular scan, they were treated appropriately, prior to initiation of dialysis. Those fistulae, which were occluded or inadequate for dialysis, were revised or a new fistula or a graft was placed. In those who had no adequate veins, a prosthetic graft was used for hemodialysis access. A small percentage of patients were deemed too sick for operative intervention and/or felt to have a severely limited life expectancy. These patients remained with a tunneled dialysis catheter for dialysis until their demise.

The introduction of interventional techniques by radiology and nephrology was started during the early years of period 1 and followed.

These changes in all modalities of treatments, and results, form the basis for this article, and its findings and recommendations.

All patients requiring dialysis access or a complication with their access referred to the author were included in this study. Therefore, the exclusion criteria were only those renal failure patients referred solely for peritoneal dialyses.

Statistical analysis

There were no extensive statistical analyses performed. The purpose of the article was to document the changes and make empirical observations of the changes occurring in the field of dialysis access. The only statistical indices were means and medians and the graphs represented numbers of procedures and patients.

Results

Over the 38 years, there were a total of 2861 patients with 5546 procedures. As is often seen in dialysis access patients, there were multiple patients who appeared in different periods for multiple procedures. This being a referral center, it was not possible to follow all the patients and their access unless their local physicians referred them back for further treatments or complications. In addition, many procedures were performed on patients referred in for complications, including abscesses, exposed grafts, and persistent or massive bleeding sites. The study groups consisted of all patients referred to the primary author for dialysis construction and/or those with complications in dialysis access.

There were significant changes through the years, especially when comparing procedures during the time period. In evaluating and tabulating data in this study, it appeared best and appropriate to divide the 38 years into three separate periods. Period 1 covered 1983–2003, period 2 covered 2004–2011, and period 3 covered 2012–2021. The changes and trends became especially salient when viewed in this manner (Table 1).

Table 1.

Review of patients and procedures in each of the individual periods.

| Period 1: 1983–2003 | Period 2: 2004–2011 | Period 3: 2012–2022 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 366 | 953 | 1542 | 2,861 |

| Procedures | 1120 | 1092 | 1710 | 3,922 |

| Prosthetic grafts | 302 | 90 | 17 | 409 |

| Ancillary/revision | 303 | 115 | 11 | 429 |

| Autogenous fistulae | 130 | 661 | 740 | 1,531 |

| Ancillary/revision | 31 | 114 | 68 | 213 |

| Cimino | 52 | 174 | 159 | 385 |

| Ancillary/revision | 7 | 10 | 17 | 34 |

| Brachiocephalic fistula | 76 | 269 | 313 | 658 |

| Ancillary/revision | 13 | 39 | 28 | 80 |

| Mid-forearm transposition | 0 | 36 | 38 | 74 |

| Ancillary/revision | 0 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Basilic vein transposition | 1 | 97 | 170 | 268 |

| Ancillary/revision | 11 | 48 | 14 | 73 |

| Brachial vein transposition | 1 | 85 | 60 | 146 |

| Ancillary/revision | 0 | 14 | 6 | 20 |

| Catheters | 43 | 827 | 754 | 1624 |

In the early years of this study, period 1, there was an emphasis on prosthetic grafts, the beginnings of interventional techniques, and the limited use of catheters for outpatient hemodialysis. In patients requiring vascular access for hemodialysis, a prosthetic graft was used approximately 69% of the time. There were 302 prosthetic grafts placed; in addition, multiple grafts were referred in requiring an additional 303 procedures to maintain patency, repair, or revise. There were 130 autogenous fistulae constructed, primarily of the radiocephalic and brachiocephalic type. There were 31 procedures required to repair or revise these autogenous fistulae. An additional cause for the increased use of prosthetic grafts in this period was the paucity of methods for outpatient hemodialysis. Arteriovenous prosthetic grafts represented a relatively quick solution at that time, since no maturation period was necessary, and they were relatively easy to insert.

In the second period (2004–2011), the effect of the NKF-DOQI for autogenous fistula construction begins to be apparent. The percentage of accesses provided by prosthetic grafts fell to 11%. The construction of autogenous fistula rose to 661 in the 10-year period, representing 88%, now consisting of radiocephalic, brachiocephalic, and basilic vein transposition. These changes are especially dramatic in light of the fact that period 2 comprised only 10 years compared to 20 years in period 1. There were 827 tunneled dialysis catheters placed in period 2, when this type of access became available. This new option further accelerated the trend of autogenous fistula, since it provided an outpatient means of dialysis access while maturation of the fistula occurred.

This trend is continued in the most recent period (period 3). The use of prosthetic graft drops to 2.2% (17) while the use of autogenous fistula increases to 97% (740). However, as shown in the literature,4,6 this comes with a cost. The number of tunneled dialysis catheters performed by the primary surgeon remains elevated at 754 in the 10-year period. These numbers, however, do not include catheters replaced or placed by interventional physicians at other institutions in these patients. Also, patient preference plays an integral part in the choice of access or dialysis catheter. Some patients prefer a catheter and, as stated before, some patients with severe comorbidities can and should only undergo dialysis catheter insertion.

The number of operative procedures for autogenous fistula revision and repair also remains elevated (68). In addition, the operative procedures for autogenous fistula have become more complex with the addition of brachial vein transposition (see Figures 1 and 2).

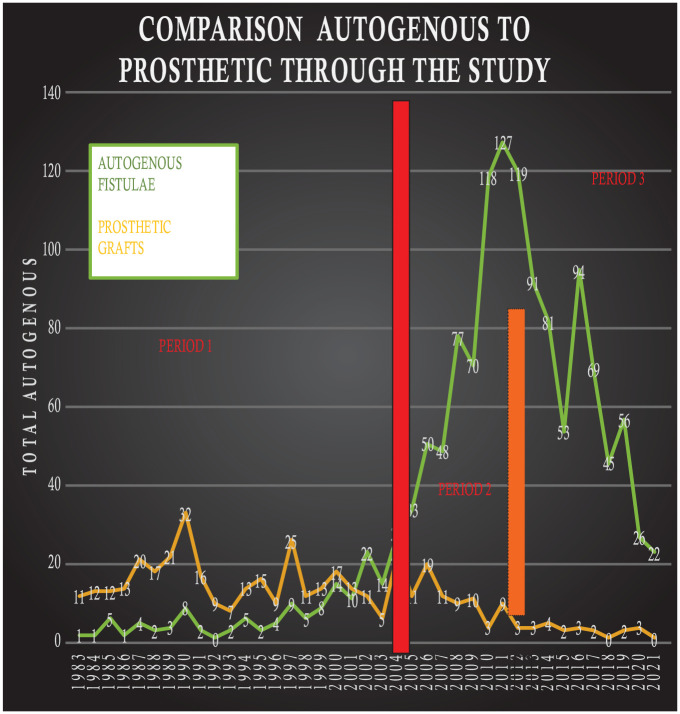

Figure 1.

Comparison of autogenous to prosthetic grafts through the three periods of the study.

Figure 2.

Total numbers of autogenous fistulae and tunneled dialysis catheters throughout the three periods.

It is of note that during periods 2 and 3, interventional procedures became more active in the treatment of dialysis access—with lysis of thrombosed accesses, dilatation of stenosis, and placement of stents (covered and bare metal) in narrowed segments of both fistulae and prosthetic grafts.

Often seen in hemodialysis access procedures, there are a multitude of procedures performed to deal with complications and maintain patency. It was noted that prosthetic grafts required far more ancillary procedures (percentage wise) to maintain functionality than autogenous fistulae. However, autogenous fistulae, while requiring fewer ancillary procedures to remain functional, had a higher rate of initial failure due to the poor quality of the vein. This can occur despite an adequately sized vein and artery—perhaps due to an undiagnosed mild thrombogenic state, technical surgical error, or a poor-quality vein.

Throughout the 38-year period, infection/cellulitis was more common in prosthetic dialysis access grafts. There were 59 (14.42%) patients with prosthetic grafts with an infection severe enough to require treatment. There were 74 patients (4.8%) with an autogenous fistula who required treatment. In essence, the autogenous fistulae could be salvaged frequently with antibiotics and/or occasional surgeries. A prosthetic graft with an infection could rarely be salvaged long term.

It needs to be emphasized that the data for the last 5 years of period 3 are a manifestation of the changes in the surgeon rather than a reflection of changes of dialysis access. It represents the slowing down of the primary surgeon (after 30 years), not the decreased need or construction of autogenous fistula in general.

The volume of patients and procedures decreased but the types of procedures and their relative percentages continued in the present trend. This further emphasizes the fact that trends described in the literature and seen in this study are consistent and real.

Discussion

This study of one surgeon’s procedures through a 38-year period is a microcosm of the changes manifested in dialysis access surgery in general.

The effect, through the years, of the use of prosthetic grafts and the gradual conversion to autogenous fistulae is clearly documented (Figure 1). Similarly, the beginnings of catheter placement and the use of silastic cuffed catheters for dialysis were evaluated and implemented (Figure 2).

Finally, the progression of the construction of autogenous fistulae is clearly demonstrated (Figure 3). The radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula, the first autogenous fistula described by Brescia and Cimino, was invaluable in initiating the use of autogenous fistula construction for hemodialysis. However, it became obvious in the early years of hemodialysis that the cephalic vein in this location could only provide limited availability due to needle sticks, intravenous lines, and overall poor quality in some patients. Then in the late 1990s to early 2000s, the vascular lab assisted in identifying other possible sources of autogenous fistulae. The mid-forearm radiocephalic, the upper arm cephalic, the basilic vein, and the brachial vein became part of the armamentarium of the vascular access surgeon. These additional locations of possible venous outflow greatly expanded the number of individuals who could benefit from the construction of an autogenous fistula for hemodialysis.

Figure 3.

Comparison of numbers of different autogenous fistulae throughout the 38 years.

In reviewing the results of the changes and surgeries in period 1, it is seen that the prosthetic grafts were the main conduit for dialysis access. The Cimino fistula and, occasionally, the brachiocephalic fistula served as the autogenous alternatives. It was in the later part of period 1 that the NKF-DOQI recommendations, as well as the Fistula First Initiative, began to push their agendas and made a significant difference on dialysis access surgery.6–8

It is in the 10-year span of period 2 that the true effects of these two initiatives are seen with a significant decrease in the use of prosthetic grafts and an increase in the construction of autogenous fistulae.

Similarly, and probably as a consequence, there is a significant increase in the numbers of tunneled dialysis catheters used. However, this also represented an increase in the number of patients receiving dialysis both for acute and chronic renal failure. These tunneled dialysis catheters were used for outpatient dialysis of patients with acute renal failure, awaiting return of renal function, as well as for patients with chronic renal failure awaiting a permanent access.

The use of tunneled dialysis catheters, in addition to offering an outpatient solution for many patients, also allowed for more attempts at autogenous fistulae. However, it has been shown that this comes with a significant price. The incidence of infection, bacteremia, and death has been associated with prolonged use of a dialysis catheter.9,10

In spite of the controversy concerning possible overuse of autogenous fistula construction, the autogenous fistula continued to be the best access due to its durability and lack of significant complications. We had every patient extensively evaluated by the vascular lab prior to any operative intervention to ensure the use of the best possible vein. All veins chosen had to be at least 2.0 mm in size to qualify for possible autogenous fistula construction.

The development of interventional techniques and the promulgation of different surgical techniques allowed this complex dialysis treatment for failing kidneys to continue. The use of an autogenous fistula in difficult, morbid, and obese patients is especially important in attempting to avoid the recurrent complications of thrombosis and infection.

Over the 38 years, it became obvious which interventional procedures were a true and helpful solution to dialysis access problems and which were not helpful and often deleterious. Interventional procedures, which were especially helpful, were declotting a fistula with ancillary dilatation of the problem area. The dilatation of a stenosis in the fistula both in the cannulation sites and in other isolated areas was helpful over time, in preserving fistula function, avoiding thrombosis, and limiting the size of aneurysmal dilatation and severe venous congestion. Similarly, the placement of a stent centrally helped to prolong the life of the fistula. However, the placement of stents for recurrent stenosis along the cannulation sites was an abysmal failure through the years and mandated a surgical approach.

It is the significant increase in interventional techniques performed by a multitude of physicians and access centers, which decreased the need for surgical correction of fistula complications. This was manifested, indirectly, by increased patency and decreased ancillary surgical procedures to maintain patency of both autogenous and prosthetic dialysis access. In general, bare metal stents were used for stenting central stenosis while covered stents were used for bleeding complications.

It was also noted that the use of stents or interventional procedures for aneurysms was unsuccessful. There were numerous attempts through the years of the study to treat patients with massive bleeding from fistulae with interventional techniques of covered stent placement and/or injection of thrombotic material, which were failures in the vast majority. The use of prosthetic stents for bleeding areas was failure because they converted an autogenous fistula to a prosthetic graft, precluded the site for possible cannulation, and often ended either in thrombosis of the fistula or in extrusion of the stent through the skin. The literature has documented these failings.11,12

Also, during these 38 years, there were a multitude of fistula and grafts, which required a surgical approach for repair or revision. Being the primary vascular surgeon in many of the patients, failure of maturation was seen and required ancillary procedures or new accesses.

In essence, the prosthetic grafts which presented with an infection, drainage, or an exposed portion required plans for a new access. Sometimes, the prosthetic graft could undergo repair, coverage, and antibiotic coverage, but would only be transient a solution and possibly provide time for a new access. Functioning autogenous fistula could be salvaged in more than 75% of the cases—as long as they were repaired with autogenous tissue and not prosthetic material.

This applied to both infected fistulae (rare) and recurrent bleeding sites. Similarly, those fistulae which presented with massive bleeding could be controlled and repaired with autogenous material more than 70% of the time. The academic centers and the literature have had similar experiences.13–15

Limitations of the study were that there was no independent blind selection of patients. The patients were those who were referred to the primary author throughout the 38-year period at the tertiary care center. This may appear to be a low number for a tertiary care center, but it only refers to one surgeon not the entire medical center. Since this study was dependent entirely on referrals to the primary author throughout the 38 years, there was no sample size calculation.

In essence, this extensive review of one surgeon’s experience over a 38-year period shows that with careful selection, good surgical technique, and preoperative duplex evaluation, most patients can have a functional autogenous fistula. If attempts at autogenous fistula construction can be done before the onset of dialysis, the necessary evil of prolonged catheter use can be avoided or, at least, limited.

Furthermore, when patients with an autogenous fistula present with bleeding or infection, the best chance for a long-term solution requires adherence to an autogenous tissue and meticulous surgical technique. It allows for possible repair and acceptance by the body and oftentimes can be used immediately postoperatively, without the need for a catheter for dialysis.

Conclusion

It appears that surgical access for hemodialysis has come full circle with the finding that autogenous hemodialysis access is the best mode of providing dialysis access. The need for excellent surgical technique combined with autogenous tissue offers the best solution for long-term utilization of a hemodialysis access.

Acknowledgments

There are no acknowledgments associated with this article.

Footnotes

Author note: This was presented in 2022 vascular access for hemodialysis symposium. Vascular Access Society of the Americas, June 11, 2022, Charleston Marriott Hotel, Charleston, South Carolina.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Carilion Clinic’s Institutional Review Board because this was a retrospective study over a 38-year period and involved no risk to patients.

Informed consent: Informed consent was not sought for this study because it was waived off by the IRB.

Trial registration: Trial registration was not applicable.

ORCID iD: Stephen l Hill  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8635-5181

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8635-5181

References

- 1. Scribner BH, Buri R, Caner JE, et al. The treatment of chronic uremia by means of intermittent hemodialysis: a preliminary report. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1960; 6: 114–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brescia MJ, Cimino JE, Appel K, et al. Chronic hemodialysis using venipuncture and a surgically created arteriovenous fistula. N Engl J Med 1966; 275: 1089–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levin N, Eknoyan G, Pipp M, et al. National kidney foundation: dialysis outcome quality initiative—development of methodology for clinical practice guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997; 12(10): 2060–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mayers JD, Markell MS, Cohen L, et al. Vascular access surgery for maintenance hemodialysis. Variables in hospital stay. ASAIO J 1992: 38; 113–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Hubert-Shearon TE, et al. A critical examination of trends in outcomes over the last decade. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 32(6 Suppl 4): S9–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ascher E, Gade P, Hingorani A, et al. Changes in the practice of Angioaccess surgery: impact of dialysis outcome and quality initiative recommendations. J Vasc Surg 2000; 31: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robbin ML, Gallichio MH, Deierhoi MH, et al. US vascular mapping before hemodialysis access placement. Radiology 2000; 217: 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silva MB, Hobson RW, Jr, Pappas PJ, et al. A strategy for increasing use of autogenous hemodialysis access procedures: impact of preoperative noninvasive evaluation. J Vasc Surg 1998; 27: 302–307; Discussion 307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee T, Barker J, Allon M. Tunneled catheters in hemodialysis patients: reasons and subsequent outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46: 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allon M, Daugirdas J, Depner TA, et al. Effect of change in vascular access on patient mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Florescu MC, Qiu F, Plumb TJ, et al. Endovascular treatment of arteriovenous graft pseudoaneurysms, indications, complications, and outcomes: a systemic review. Hemodial Int 2014; 18(4): 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aurshina A, Hingorani A, Marks N, et al. Utilization of stent grafts in the management of arteriovenous access pseudoaneurysms. Vascular 2018; 26(4): 368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasklinsky G, Meisner R, Labropoulos N, et al. Management of true aneurysms of hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg 2011; 53(5): 1291–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inui T, Boulom V, Bandyk D, et al. Dialysis access hemorrhage: access rescue from a surgical emergency. Ann Vasc Surg 2017; 42: 45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jaffers GJ, Fasola CG. Experience with Ulcerated, bleeding autologous dialysis fistulas. J Vasc Access 2012; 13(1): 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]