Abstract

Purpose: To examine how federal/state-level policy guidance and local context have influenced district and school leader responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as how these external/internal factors might provide a window into K-12 crisis leadership and policy sensemaking more broadly. Research: Investigating two districts over two years (2020–2022), data gathered include 39 hours of interviews with K-12 leaders (n = 41) and teachers (n = 18), federal/state-level policy documents (N = 64) governing these districts, and school staff responses to the Comprehensive Assessment of Leaders for Learning survey (N = 111). Drawing theoretically upon sensemaking, crisis leadership/management, law/policy implementation, and organizational theory, these data were analyzed using both inductive and deductive coding over several phases. Findings: In tracing the confluence of federal/state-level guidance and local capacities, we find both influenced K-12 leaders’ sensemaking and subsequent responses to COVID-19. However, districts that possessed adequate expertise and organizational resources were better positioned to respond to the crisis, whereas those lacking such capacities experienced increased anxiety/stress. Conclusion: We argue that the COVID-19 pandemic provides a new window into the critical external/internal factors influencing K-12 leader sensemaking and subsequent responses to crises more broadly. We also discuss the potential role intermediate service agencies might play in the development of a stronger crisis response infrastructure for associated districts and schools. Finally, we point out how principal preparation programs and professional development efforts could prospectively address such crisis-related challenges faced by K-12 leaders.

Keywords: crisis leadership, crisis management, education policy, COVID-19, district leadership, school leadership

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted countless sectors of life and work in the United States (US) and abroad. Over the past four academic years, K-12 school systems have been particularly hit hard (Shores & Steinberg, 2022; Sparks, 2021). Almost immediately, 50 million K-12 students were pulled from their physical classrooms, along with 3.5 million teachers (National Academy of Education, 2020). While districts have returned to in-person instruction (Grossmann et al., 2021), the pandemic has negatively impacted students’ learning opportunities and academic performance, particularly for those traditionally underserved (e.g., Belsha et al., 2020; Domingue et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2022; Kuhfeld et al., 2022; Lewis et al., 2022; Muñiz, 2021; NAE, 2020; OECD, 2021; Patrick et al., 2021). There has also been increased turnover and burnout among administrators (DeMatthews, 2021; Sawchuck, 2021) and teachers (Bleiberg & Kraft, 2022; Kraft et al., 2020; Pressley, 2021). Notwithstanding, emerging evidence about the impact of COVID-19 on K-12 school systems has been largely anecdotal (but see De Voto & Superfine, 2023; Goldhaber et al., 2022; Grossmann et al., 2021; Kaul et al., 2022; Kuhfeld et al., 2020, 2022; Pressley, 2021). Notably, few studies have empirically examined its impact on K-12 leadership sensemaking and subsequent responses at the district/school-level (but see DeMatthews et al., 2021; De Voto & Superfine, 2023; Francois & Weiner, 2022; Harris & Jones, 2020; Lochmiller, 2021; McLoed & Dulsky, 2021; Kaul et al., 2022; Lifto, 2020; Thornton, 2021). Moreover, no known studies have fully explored K-12 leadership sensemaking to COVID-19 in terms of the broader literature examining federal/state-level policy guidance and differences in local organizational capacities (e.g., leader expertise, human/fiscal resources).

Grounded in literature on sensemaking in times of crisis, crisis leadership/management, law/policy implementation, and organizational theory, this study accordingly examines how district and school administrators have made sense of and responded to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Investigating two districts over two years in the United States (2020–2022), we: (a) conducted extensive interviews with K-12 leaders (n = 41) and teachers (n = 18); (b) analyzed federal/state-level policy documents (N = 64) governing these districts; and (c) gathered local responses to the Comprehensive Assessment of Leaders for Learning (CALL) survey (N = 111). We find districts that possessed adequate expertise and organizational resources were better positioned to make sense of and respond to the crisis, whereas those lacking such capacities experienced increased anxiety/stress. Three research questions guided these findings:

How did federal and state policy documents govern district and school leader sensemaking and subsequent responses to the COVID-19 pandemic?

How did local organizational capacities (i.e., expertise and human/fiscal resources) influence district and school leader sensemaking and subsequent responses to the COVID-19 pandemic?

How did the particularly challenging conditions presented by a crisis influence district and school leader sensemaking and subsequent responses to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Addressing these questions has the potential to inform our understanding of the legal and organizational factors influencing how crisis policy guidance is perceived, interpreted, and responded to by K-12 leaders. In doing so, this study not only provides greater knowledge about how administrators have made sense of/responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, but also offers a window into some of the major external/internal factors influencing administrator crisis sensemaking and response more broadly.

This article is organized as follows. We first discuss background literature related to COVID-19's impact on K-12 education, particularly district and school administrators. Next, we present our conceptual framework and methods of study. Third, we highlight our findings with respect to how federal/state-level policy guidance and organizational capacities influenced K-12 leader sensemaking and subsequent responses. Fourth, we unpack how our findings offer a window into some of the major factors influencing K-12 leader sensemaking and subsequent responses to crises, and how principal preparation programs (PPPs) and in-service professional development efforts might proactively address. Finally, we discuss the potential role intermediate service agencies (ISAs) might play in the development of a stronger crisis response infrastructure beyond the school and district levels

Background Literature

Research has long shown the importance of district and school leadership on K-12 decision-making and outcomes (Day et al., 2016; Grissom et al., 2021; Grissom & Loeb, 2011), particularly during crises (De Voto & Superfine, 2023; Grissom & Condon, 2021). On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Within weeks, many U.S. states issued mandates to close K-12 schools (DeMatthews et al., 2021; Grossmann et al., 2021), forcing 50 million students and 3.5 million teachers to operate remotely (NAE, 2020). Although schools have since reopened (Grossmann et al., 2021), calls of “learning loss”—especially for those traditionally underserved—have run rampant (e.g., Dorn et al., 2020; Engzell et al., 2021; Fuchs-Schundeln et al., 2020; Kuhfeld et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2022; Shores & Steinberg, 2022). Additionally, increased turnover/burnout among administrators (Clifford & Coggshall, 2021; DeMatthews, 2021; Sawchuck, 2021) and teachers (Bleiberg & Kraft, 2022; Pressley, 2021) have become the norm.

Notwithstanding, research on K-12 leaders’ responses largely remains limited (in the United States and abroad). However, we foreground our study in several recent works. First, in examining the perspectives of rural superintendents during COVID-19, Lochmiller (2021) found the pandemic has profoundly shifted their work, particularly in states with limited school closure mandates. For example, rural superintendents had to make many local public health decisions surrounding reopening their districts, while also participating in lesser-known activities (e.g., contact tracing and quarantining). Second, Thornton (2021) interviewed 18 principals in New Zealand about their experiences during COVID-19. Her findings echoed those of rural superintendents in the U.S. (Lochmiller, 2021), particularly the need for administrators to be flexible and optimistic. In other words, K-12 leaders around the globe have had to be stalwarts for their districts, schools, and associated communities. They have also had to make sense of new roles that otherwise would not be in their purview, pre-pandemic. Third, using data from the RAND American Educator Panels COVID-19 Surveys, DeMatthews and colleagues (2021, p. 7) found few districts were prepared for COVID-19; the majority of administrators reported a lack of “planning, preparation, and resources” to deal with the crisis, especially the closures and transition to remote instruction. Fourth, analyzing the experiences of 20 principals in four large, urban school districts (the U.S.), Kaul and collegues (2022) point out that K-12 leaders took two different approaches when responding to local COVID-19 policies—abiding or subverting. These approaches were further tethered to pre-existing organizational conditions, including decision-making, collaboration structures, and social relationships. Notably, our study seeks to elaborate upon these external and internal factors.

While K-12 leaders have long had to operate in increasingly uncertain environments (Cosner & Jones, 2016) Stone-Johnson and Weiner (2020) further argue that the pandemic has exposed the fundamental limits of professionalism for K-12 leaders, specifically around expertise and autonomy. Indeed, K-12 leaders have had to make many local public health decisions themselves, despite not being in the best position to do so. Decisions include defining classroom capacities to reflect social distancing, contact tracing, and mask mandates. At the same time, they have had to make sense of and respond to federal/state-level policy guidance, reducing their professional autonomy. The result has been a tug-of-war between needing guidance and support during the pandemic and being given some local control.

Taken together, recent research shows a confluence of federal, state, and local factors have impacted K-12 leaders’ responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study builds on these findings and theoretical investigations by highlighting how issues of local control and federal/state governance have placed added stress on leader sensemaking and varying district/school capacities to effectively respond.

Conceptual Framework

Indeed, many factors shape K-12 leader sensemaking and subsequent responses (Coburn, 2005). To study how district and school administrators have responded to a crisis like COVID-19, we borrow concepts from several areas of literature: (a) sensemaking in times of crisis; (b) crisis leadership/management; (c) law/policy implementation; and (d) organizational theory. Together, they point to several external and internal factors that influence K-12 crisis response, including policy guidance, leader expertise, and organizational resources. Each area of literature is discussed in turn, and where appropriate, how these external and internal factors play a role in K-12 crisis response.

Sensemaking in Times of Crisis

The concept of sensemaking is rooted in cognitive psychology. Piaget and Cook (1952) state that when learning to address something new (e.g., a crisis), humans assemble stimuli into frameworks or “schemata.” These schemata help them “to comprehend, understand, explain, attribute, extrapolate, and predict” (Starbuck & Milliken, 1988, p. 51). Within organizations, this process is both collective and individual. As organizational actors interact with their colleagues, they construct “shared understandings” based on workgroup culture, beliefs, and routines (Coburn, 2005). However, by virtue of their formal role, leaders exert authority over how organizations collectively make sense of and respond to a given situation (Coburn, 2005; Firestone, 1996). This is particularly true in times of crisis (see Weick, 1993).

During a crisis, leaders must be able to leverage their individual expertise and available resources to assist collective sensemaking (Weick, 1993). From this view, expertise and resources can be thought of as internal factors influencing sensemaking (please see the organizational theory subsection for a more nuanced explanation). Yet making sense of a crisis is also subject to external factors, especially policy guidance (via the fed., state, or city/county). Such external guidance can be categorized as loose or tight. Whereas loose guidance gives more discretional sensemaking to local actors, tight guidance explicitly tells local actors what they must do (please see the law and policy implementation subsection for a more nuanced explanation). Taken together, these external and internal factors support or inhibit effective crisis response. Using crisis leadership/management, law/policy implementation, and organizational theory, we further detail these external/internal factors.

Crisis Leadership and Management

Over the past several decades, the COVID-19 pandemic is merely one of many crises district and school leaders have had to make sense of and respond to (Striepe & Cunningham, 2021). According to Smith and Riley (2012, p. 58), a crisis can be broadly defined as an “urgent situation that requires immediate and decisive action by an organisation” (Smith & Riley, 2012, p. 58). However, not all crises are created equal. Scholars tend to categorize crises as either “sudden” or “smoldering” (see James & Wooten, 2005). Sudden crises are unexpected (e.g., natural disasters, COVID-19) and have an external locus beyond organizational leadership (see Grissom & Condon, 2021). Conversely, smoldering crises have an internal locus, beginning as smaller problems within an organization and multiplying over time due to inattention (e.g., staff embezzlement). Whether the crisis developed outside or inside the organization, crisis leadership and management are seen as two internal factors influencing their responses (Grissom & Condon, 2021; Mutch, 2015).

Crisis leadership tends to be associated with characteristics leaders may possess while crisis management is more operational (e.g., developing disaster plans, conducting disaster drills, and identifying roles/responsibilities; see Mutch, 2015). From this view, leaders become influential actors for their respective organizations (Potter et al., 2021; Thornton, 2021). However, because leaders’ capabilities and local conditions vary (Mutch, 2018), crises often produce “winners” and “losers” (Boin et al., 2013). Notably, these inequitable differences are further related to organizational sensemaking in conditions of uncertainty (e.g., Boin et al., 2013; Grissom & Condon, 2021; McLeod & Dulsky, 2021; Mutch, 2015). During a crisis, leaders are flooded with external information they must rapidly interpret under stress (Potter et al., 2021). This information—some of which is inaccurate or incomplete—influences their organization's responses (Mumford et al., 2007; Potter et al., 2021; Weick, 1976). In the process, they become critical funnels and buffers of such information across actors (Honig, 2012).

As it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic, K-12 leaders have largely depended upon external guidance from the federal-, state-, and local-level due to their inexperience with public health crises (McLeod & Dulsky, 2021). Yet some of this guidance (particularly early on) was inadequate (see DeMatthews et al., 2021; Grossmann et al., 2021), necessitating further advice from external stakeholders (De Voto & Superfine, 2023). In this way, open communication across internal and external stakeholders is critically important for K-12 leaders to build trust, shared understandings, and make informed decisions during crises (Fletcher & Nicholas, 2016; Mutch, 2015, 2018). At the same time, K-12 leaders in the United States currently do not receive preparation in crisis management (see Kitamura, 2019; Lichtenstein et al., 1994; McCarty, 2012). As such, most crisis sensemaking is learned in the field, resulting in a wide range of organizational expertise and local capacities to respond to sudden crises like COVID-19 (Striepe & Cunningham, 2021).

Law and Policy Implementation

Because K-12 leaders have depended upon external federal-, state-, and local-level guidance when making sense of the COVID-19 crisis, we further draw on literature examining law and policy implementation. Notably, we focus on the importance of local responses to external policy signals or designs (Lipsky, 1971; Weatherley & Lipsky, 1977). Broadly, this literature has long underscored that the nature and intensity of problems influence local actors in various ways (e.g., Berman, 1986; Berman & McLaughlin, 1978; Datnow & Park, 2009; Honig, 2006; Majone & Wildavsky, 1984; McLaughlin, 1987). For example, when federal statutes rely on state and local agencies to address the problem, and when ground-level implementers display limited understandings toward statutory directives, some local actors will make sense of a policy as intended and others will not (Lipsky, 1971; Sabatier & Mazmanian, 1979). Weatherley and Lipsky (1977) refer to these circumstances as “street-level bureaucracy.” Local responses therefore critically depend on how such actors make sense of an external policy's design (see Spillane et al., 2002), as Kaul and colleagues (2022) found with COVID-19 state-level guidance.

Notwithstanding, a sudden crisis like COVID-19 is arguably one of the most intractable sorts of problems, stressing the ability of local agencies to effectively respond (Sabatier & Mazmanian, 1979). To this end, actions taken by federal or state institutions further play a role in this process (Weatherley & Lipsky, 1977). Typically, these institutions release a significant amount of external guidance during a crisis (as opposed to formally enacted statutes or regulations; see Superfine, 2011). Although some states have released more external guidance than others during the pandemic (see Grossmann et al., 2021), the looseness or tightness of such guidance further effects how K-12 leaders respond (Grossmann et al., 2021; Harris & Strunk, 2021). Loose guidance is best suited to situations where local conditions vary because it gives more discretional sensemaking to local actors. However, this means loose guidance also demands more leader expertise and local capacities to make sense of and implement such guidance (Superfine, 2013). Conversely, tight guidance is best suited to homogenous conditions because it specifies precisely what local actors are supposed to do. In the process, tight guidance reduces the need for leader expertise (but not local capacities) in making sense of and responding to such guidance.

In either case, how external policy guidance is communicated to local actors—or street-level bureaucrats (Weatherley & Lipsky's, 1977)—also influences its implementation (Cohen & Moffitt, 2009). For instance, scholars have long highlighted the importance of “boundary spanners” in promoting coherent sensemaking and policy implementation across multiple actors at different organizational levels (Burt, 2001, 2005; Daly et al., 2014; Honig, 2006), including during COVID-19 (see Anderson & Weiner, 2023; De Voto & Superfine, 2023). These individuals act as “brokers” (see Stovall & Shaw, 2012), bringing new ideas, understandings, and/or other resources to local actors who otherwise might not be directly connected to external policy signals. That said, boundary spanners generally do not have the requisite authority to leverage responses in the “receiving” organizations; rather, they translate information for key actors (e.g., district and school leaders), who then make internal decisions about how best to proceed (Honig, 2006; Tushman & Scanlan, 1981). In turn, these messages are further impacted by the receiving organization's local capacities to successfully implement translated information (as Kaul et al., 2022, argue concerning COVID-19).

Organizational Theory

While laws, policies, and subsequent guidance make up external factors influencing crisis response, using organizational theory, we highlight several internal factors—namely (a) leader expertise and (b) organizational resources and routines. We define expertise as the competencies required for leaders to successfully address a pressing problem. As Weick (1993) argues, an organization's ability to properly respond to a crisis is compromised when leaders lack such expertise. This tends to happen when the pressing problem is more ambiguous (e.g., constantly changing), leaders are thrust into unfamiliar roles (e.g., becoming a public health expert), or the organizational system has loose ties (e.g., districts/schools). Moreover, leaders may possess expertise in some areas but not others (Reitzug & Reeves, 1992; Sebastian & Allensworth, 2012)—such as teaching and learning but not facilities management or public health. Depending upon the crisis, these internal factors can therefore impact how they respond, and how they communicate those responses across other street-level bureaucrats.

COVID-19 research already shows many K-12 leaders have lacked initial expertise with instructional demands like remote learning (DeMatthews et al., 2021) and public health demands like contact tracing (Lochmiller, 2021). However, expertise by itself is not sufficient in helping leaders address a crisis; an organization must also have the proper internal resources and routines to do so (see Weick, 1993). Resources can be physical (e.g., monetary assets, managerial talent) or intrapersonal (e.g., knowledge, relationships, mission; see Kraatz & Zajac, 2001) whereas routines are a “repetitive, recognizable pattern of interdependent actions that serve as agreements about how to do organizational work” (Spillane et al., 2009, p. 95). Together, resources and related routines operationalize leader expertise when making sense of and responding to a crisis.

From this view, when organizations lack resources and/or routines, a leader may be hampered to effectively act despite having the requisite expertise (McLaughlin, 1987). This is because they do not have the proper tools to address the problem (Weick, 1993), or other street-level bureaucrats have trouble making sense of the crisis. In contrast, organizations exhibiting sufficient internal resources and/or routines are best positioned to leverage a leader's expertise toward a given crisis (e.g., buying the proper remote platform or personal protective equipment).

Bringing Crisis Leadership, Law/Policy Implementation, and Organizational Theory Together

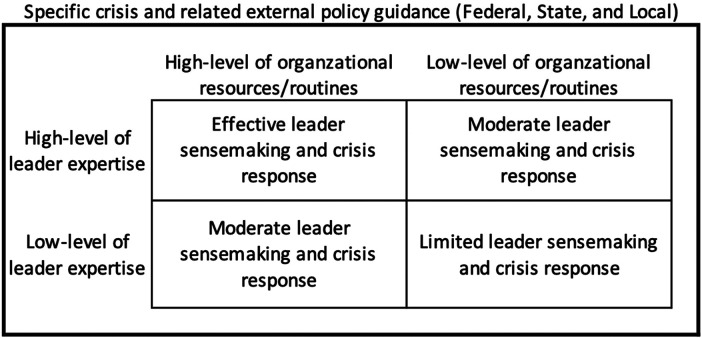

Collectively, this diverse literature points to several external and internal factors that influence how district and school leaders make sense of and subsequently respond to sudden crises like COVID-19. On the one hand, federal, state, and local guidance produce external signals that leaders must interpret and implement. On the other hand, internal factors like leader expertise and organizational resources/routines further impact whether and how such external guidance is implemented. That said, we must acknowledge that these bodies of literature (and outlined external/internal factors) provide for a more linear crisis response than might otherwise exist across local contexts. Therefore, to help illustrate this intersection visually, we designed Figure 1.

Figure 1.

K-12 Leader Sensemaking and Subsequent Crisis Responses.

Put simply, leader expertise and organizational resources/routines work together to produce effective, moderate, or limited sensemaking and crisis responses. These responses are further influenced by the external challenges posed by the crisis itself, and what federal, state, and local guidance exists.

Finally, as discussed, COVID-19 has presented an intractable problem for federal, state, and district entities, regardless of how effective responses might be at any layer throughout these loosely coupled systems. We argue this is precisely what defines the pandemic as a crisis for the K-12 education sector. Consequently, local expertise is almost assuredly lacking in some respects. But we hypothesize districts and schools with more organizational resources/routines are better positioned to deal with the challenges presented, and likely to view their situations more favorably.

In the following sections, we compare and contrast how two districts in one state navigated COVID-19, and what external/internal factors influenced their responses. In doing so, we aim to advance the field's knowledge not only about K-12 leaders’ responses to the pandemic, but also about how they make sense of/respond to crises more broadly.

Methods

To investigate the influence of federal/state-level policy and organizational capacities on K-12 administrator crisis response, we employed a multiple-embedded case study (Yin, 2013). This design allows for the rigorous examination across multiple policy and organizational levels, while ensuring feasible data collection. Two case districts in Illinois—Washington and Hamilton (pseudonyms)—were chosen via purposive sampling (Patton, 2002). These districts are part of a five-year, US $5M National Science Foundation (NSF) grant that uses a design-based implementation research (DBIR) process to co-develop and co-implement a multicomponent professional development (PD) intervention to improve teachers’, teacher leaders’, and administrators’ understandings of effective math teaching and learning. Selecting both case districts from the same state was important because while federal guidance has remained constant (Reich et al., 2020), state-level guidance has varied considerably (see Courtemanche et al., 2021; Goldhaber et al., 2021; Grossmann et al., 2021). In Illinois, the Governor's Office, State Board of Education (ISBE), and Department of Public Health (IDPH) have provided significant guidance to K-12 districts, but left most decisions up to local authorities (i.e., district/school leaders and county departments of health).

To study the interaction between federal/state-level policy and varying organizational capacities, we selected a resource-rich (Washington) and resource-deficient (Hamilton) district. These designations were specifically based on the “adequacy target” component of Illinois’ school finance formula, which models all education cost factors in relation to the actual costs (as a percentage) required to operate the district satisfactorily. However, these designations were reinforced by responses to the Comprehensive Assessment of Leaders for Learning (CALL) survey (N = 111), which assesses school-wide leadership and organizational capacity (see data sources for more detail). Indeed, Washington remained one or more standard deviations above the national CALL average, whereas Hamilton was at least one standard deviation below across all organizational domains. As a control, we kept other demographic factors (e.g., race, percent free, and reduced lunch) relatively similar.

Within each selected district, K-8 schools became our embedded cases. Washington has four and Hamilton has three. Notably, high schools were left out of the case design because the NSF project is specifically geared toward improving K-8 math teaching and learning across four districts (two of which are highlighted in this study). At the same time, because high schools are departmentalized, examining their responses across organizational levels would prove difficult. See Table 1, which illustrates the demographics across both case districts and their embedded schools.

Table 1.

Demographics of Selected Cases.

| Number of Schools | Percent Adequacy Target | Percent Free and Reduced Lunch | Percent White | Percent English Language Learners | Percent Student Mobility | Percent Teacher Retention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington | 4 | 120% | 57% | 42% | 15% | 5% | 86% |

| Hamilton | 3 | 57% | 62% | 67% | 34% | 9% | 88% |

Data Sources and Procedures

Three different sources of data were collected across our selected cases in Illinois: (1) federal/state/local documents (N = 64); (2) semi-structured interviews with leaders and teachers (N = 59); and (3) staff responses to the CALL survey (N = 111).

Federal/State/Local Documents

In order to better understand the frequency and substance of external policy guidance, we collected documents and letters issued by the federal government, Governor's Office, ISBE, and other education leadership associations between March and August 2020. We also gathered guidance released through both districts’ local intermediate school districts (ISAs). According to ISBE, ISAs “provide staff development, technical assistance, and information resources to [local] public school personnel” (see www.isbe.net/roe), helping us further examine the extent to which these agencies synthesized federal/state-level guidance.

This six-month range was chosen for two reasons. On the one hand, these months coincide with the state's initial executive order (No. 2020-05) to shutdown schools (in favor of remote instruction) and district preparations for returning to in-person schooling. On the other hand, all substantial federal-, state-, and local-level guidance was disseminated during this time. Although other documents have been circulated since August 2020 (particularly from ISBE and IDPH), these newer documents only slightly modify prior letters/guidance, limiting further sensemaking on behalf of district/school leaders. Outside of this month range, we therefore only include the federal government's mandate for state standardized testing (spring 2021), as well as a letter issued in July 2021 from Illinois K-12 leaders to the Governor urging for more guidance during the COVID-19 delta variant outbreak (see Lewis, 2021), which resulted in a corresponding executive order (No. 2021-20).

All documents were collected via the U.S. Department of Education's (DOE) website, ISBE's website, and by the third author (via affiliation as an Illinois district leader outside our selected cases). The contents of these collected documents fall into three different areas: (1) teaching-related (e.g., remote instruction); (2) health-related (e.g., social distancing, masking); and (3) learning-related (e.g., standards, curriculum). It should also be noted that we did not collect district-level documents, guidance, or plans. This is because Illinois districts primarily depended on state-level guidance, whereas local documents only interpreted what was funneled down from the state (e.g., mask mandates, social distancing signage, or quarantining/contact tracing protocols) or county (i.e., regional ISA or department of health). Additionally, local emergency response plans were not collected as they were not amended for COVID-19 (i.e., primarily related to active shooters and tornados).

Interviews

The bulk of our data collection came from semi-structured interviews with district and/or school leaders (n = 41) and teachers (n = 18). Leaders included superintendents, assistant superintendents, education directors (i.e., SPED, ELL), principals, and assistant principals. We also interviewed the executive director of the regional ISA that supports both districts. Teachers included all grade-levels K-8, including SPED. All interviews were collected across four points in time: (1) spring 2020, a few months after the initial school closures; (2) winter 2021, as districts/schools learned to cope with navigating COVID-19 during a full academic year; (3) fall 2021, as districts/schools continued to adjust to a new “normal”; and (4) spring 2022, as state mandates were lifted. However, to minimize the stresses on our selected cases navigating the pandemic, we only interviewed all selected leaders in winter 2021, opting for a smaller subset in spring 2020, fall 2021, and spring 2022. Also, teachers were only interviewed in spring 2022, and mainly served to trace district/school leadership responses and their impact at the classroom-level.

All leaders and teachers were given pseudonyms based on their district (D03 for Washington, and D04 for Hamilton), building (B01 for central office, and B02, etc., for each embedded K-8 school), and role (A for district leader, P for principal, B for assistant principal, and T for teacher). Leaders and/or teachers from both central offices and all embedded K-8 schools were represented. Please see Table 2 detailing this information across the four time periods.

Table 2.

Conducted Sample Interviews.

| Role | Spring 2020 | Winter 2021 | Fall 2021 | Spring 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington | |||||

| D03_B01_A03 | Asst. Superintendent | X | X | X | X |

| D03_B01_A04 | SPED Director | X | X | ||

| D03_B01_A11 | ELL Director | X | |||

| D03_B02_P01 | Principal | X | X | ||

| D04_B02_P01B | Asst. Principal | X | |||

| D03_B03_P02 | Principal | X | X | X | |

| D03_B04_P03 | Principal | X | X | ||

| D03_B04_P03B | Asst. Principal | X | |||

| D03_B05_P04 | Principal | X | X | X | |

| D03_B05_P04B | Asst. Principal | X | X | X | |

| D03_B02_T10 | Grade-4 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B02_T13 | Grade-6 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B02_T14 | Grade-6 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B03_T26 | Grade-6 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B04_T32 | Grade-3 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B05_T44 | Grade-1 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B05_T60 | Grade-2 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B05_T44 | Grade-1 Teacher | X | |||

| D03_B05_T65 | Grade-6 Teacher | X | |||

| Hamilton | |||||

| D04_B01_A01 | Superintendent | X | X | X | X |

| D04_B02_P01 | Principal | X | X | ||

| D04_B02_P01B | Asst. Principal | X | X | X | X |

| D04_B03_P02 | Principal | X | X | X | X |

| D04_B04_P03 | Principal | X | X | ||

| D04_B04_P03B | Asst. Principal | X | X | ||

| D04_B02_T10 | Math-2 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B02_T15 | Math-4 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B02_T16 | Math-4 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B02_T17 | Math-5 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B02_T23 | Math-3 SPED | X | |||

| D04_B02_T16 | Math-4 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B03_T53 | Math 2 SPED | X | |||

| D04_B04_T55 | Math-8 Teacher | X | |||

| D04_B04_T57 | Math-7 Teacher | X |

A different semi-structured protocol was used for each point in time. The first protocol (spring 2020) primarily served as a “check-in” with a limited number of leaders from our sample (n = 6). We wanted to understand how Washington and Hamilton’s leaders were initially coping with the sudden closure of schools and transition to remote instruction. The second protocol (winter 2021) sought to understand the extent to which leaders were becoming accustomed to operating within the pandemic (i.e., learned expertise), including (a) what information/stakeholders they depended on (e.g., guidance, other districts, peers, etc.) and (b) what organizational resources they had (or didn’t have) at their disposal. Specific questions were modified based on their role but included questions like: (1) “What key sources or stakeholders have you come to depend on most for guidance while operating as a district during the pandemic?”; (2) “What challenges, if any, have transpired across your district since the beginning of the pandemic?”; and (3) “How are you personally feeling about navigating and working as a district/school leader during the pandemic?” The third protocol (fall 2021) sought to capture data that needed more elaboration. Interviewing a small subset of our sample (n = 7), we asked questions like: (1) “What state guidance, if any, do you feel you need that has been missing to effectively respond to the pandemic?”; (2) To what extent do you feel your district has had the organizational resources needed to effectively respond to the pandemic?”; and (3) “How do you feel about navigating the pandemic since last time we talked?”. The fourth protocol (spring 2022) was designed for leaders and our subset of teachers and sought to understand lessons learned, including its impact on instruction and staff/student wellbeing. To reduce physical exposure, all interviews were conducted via Zoom, lasted between 15 and 60 minutes, and were audio-recorded. A total of 39 hours were recorded in assembling these findings.

CALL Survey

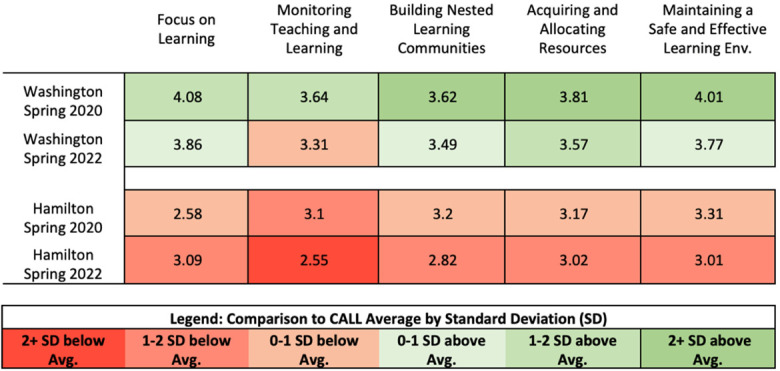

To further cross-examine organizational resources and leader expertise between both case districts, we opted to use the CALL survey. This on-line formative assessment and feedback system was developed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Kelley et al., 2012). It assesses school-wide leadership and organizational capacities (including resources) through five evidence-based domains: (1) focus on learning; (2) monitoring teaching and learning; (3) building nested learning communities; (4) acquiring and allocating resources; and (5) maintaining a safe and effective learning environment. We were particularly interested in domains three through five, as they best aligned to our conceptual framework that prioritizes leadership expertise and organizational resources/routines during sudden crises. Each domain has a score from 1 through 5, which is aggregated across respondents and then compared to the national average to provide standard deviations.

The CALL survey was administered in spring 2020 and spring 2022. These time points were chosen to measure both initial organizational responses to COVID-19, as well as during recovery (see Grissom & Condon, 2021). We hypothesized that those districts with effective leadership and greater accessibility to resources would be better positioned to address the crisis. About half of all leaders and K-8 teachers completed the survey over both points in time (N = 111).

Because specific CALL domains and aggregated scores are integrated within the qualitative findings, we have chosen to display the full survey findings here. Please see Table 3.

Table 3.

CALL Survey Data (Spring 2020 and Spring 2022).

|

|

Abbreviation: CALL = Comprehensive Assessment of Leaders for Learning.

As the legend points out, the colors refer to the average standard deviation in relation to all districts who took the CALL survey (in a given year). Writ large, Washington's responses outpaced Hamilton's by one to two standard deviations, indicating a substantial difference in organizational resources and leadership expertise. These data, therefore, support our case selection of a resource-rich and resource-deficient district.

Analysis

All documents and interviews were uploaded to Dedoose—a web-based qualitative data software—for analysis. Using our conceptual framework, we produced a set of 35 a priori codes. To establish reliability across these codes, we conducted several rounds of interrater reliability (IRR) between all three authors. The first round of practice coding resulted in Cohen's Kappa (κ) of .049 (indicating moderate reliability). Three codes were particularly problematic: (1) local conditions, (2) instructional changes/impact, and (3) learning changes/impacts. After discussing these coding discrepancies, we clarified our definitions and examples for each code to more precisely articulate when to employ each. We then conducted a second IRR test resulting in (κ) = 0.91, indicating significant reliability.

All data were coded in several phases. After an initial pass, we met to discuss our findings and whether the coding scheme captured all relevant schemata. These discussions propelled the need to conduct a third and fourth round of interviews (fall 2021, spring 2022)—including a subset of teachers—to clear up a few points. After these leader/teacher interviews were completed, a second round of coding was conducted across all data to ensure the trustworthiness of our initial analysis. Another group discussion followed, in which we agreed data were successfully coded and sufficient evidence was gathered to draw conclusions from across our selected cases. Finally, memos were created for each code. We then cross-examined these memos to identify core themes, particularly as they related to the intersection between federal/state-level policy and local organizational capacities (i.e., leader expertise and resources/routines). A total of 764 individual pieces of data were analyzed by the team in assembling these findings. Following Stake (1995), we then used an instrumental approach. This approach seeks to use various cases in an effort to examine a broader set of phenomena (see De Voto et al., 2021, De Voto & Gottlieb, 2021, for example). In the process, we were able to trace the major external/internal factors working together to influence district and school administrator responses during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how these might provide a window into administrator crisis sensemaking and response more broadly.

Limitations

While every effort was made to maintain a rigorous, mixed-methods research design, we recognize this study has several limitations. Most importantly, we only examined guidance from one state—Illinois. As such, other states—particularly those governed by conservatives—may have provided districts less guidance (see e.g., Courtemanche et al., 2021; Grossmann et al., 2021), which could in turn increase local district variation. Second, we only examined two districts within Illinois. Despite selecting districts with different adequacy targets, access to resources, and controlling for other demographics, Illinois currently has 859 independent school districts. Therefore, we are unable to verify with absolute certainty the ways in which K-12 leader responses could be different in other districts.

Findings

In tracing the external (i.e., federal-, state-, and local-level guidance) and internal (i.e., leader expertise and resources) factors across two districts, we find both have impacted K-12 leader sensemaking and responses to COVID-19. At the federal-level, there have been relatively few communications during the pandemic—aside from standardized testing mandates related to Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) accountability measures. In turn, the Governor's Office/ISBE/IDPH has released a significant amount of state-level guidance, which was then further mirrored by local health departments. That said, K-12 leaders with whom we spoke (15/16) overwhelmingly feel this state/local guidance has been relatively loose and untimely, resulting in the need for more assistance—particularly from other districts (via boundary spanners). And while such boundary spanning has increased leaders’ expertise, we find their sensemaking and subsequent responses have ultimately been dependent upon existing organizational resources and routines, producing some inequities. Indeed, Washington leaders have been able to leverage their ample resources to adopt a wide swath of new routines. Meanwhile, Hamilton leaders have had less resources to work with, limiting their overall responses. Notwithstanding, K-12 leaders across both districts have remained resilient throughout the crisis, becoming accustomed to a “new normal.”

We first discuss the external federal/state/local-level guidance documents governing K-12 leader responses, followed by the boundary spanning they engaged in to locally make sense of them. We then discuss how internal factors like leader expertise and organizational resources/routines further influenced how such external guidance was interpreted. To help bridge the external/internal factors impacting Washington and Hamilton's sensemaking, we discuss three different scenarios: (1) remote instruction, (2) public health, and (3) curriculum implementation. Where applicable, we integrate interview and CALL data from leaders and/or teachers.

External Guidance Governing District and School Leader Responses

Federal Guidance

External guidance from the Fed was specifically provided to Illinois (and other states) via the DOE. We found a total of seven K-12 documents were disseminated between March and August 2020. However, none of these documents were related to public health or instruction; rather, they were compliance letters or “fact sheets” for special education, migratory children, and English language learners (ELLs). There was also one letter waiving certain standardized testing requirements under ESSA for 2019–2020 due to the mass school closures.

Under former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and the Trump Administration, such limited guidance was common (see De Voto & Reedy, 2021). Yet the Biden Administration and new Secretary Miguel Cardona also did not grant any state waivers for testing requirements in 2020–2021, instead granting some “flexibility” (Barnum, 2021). For instance, Illinois was authorized to waive certain standardized assessments, but not all of them (Cantù, 2021). Thus, Washington and Hamilton administrators with whom we spoke (15/16) disagreed with the federal government's testing mandates in 2020–2021 because of their disruption to instructional time in a hybrid environment (i.e., remote/in-person). As one Hamilton principal (D04_B02_P01) said:

Personally, I don’t think we should be testing [during a crisis]. And my reasonings are really because of the fact of time. We don’t have a ton of time with these kids, and that is possibly seven to eight days of testing for us because our students only come half-day, so we would lose about two weeks of instruction [in 2020-2021] just with testing because the other half of the day, those students are home. So, if it were a typical year, we would take a 70 or 90-minute test, and then the rest of the day we would have to teach, but this year we don’t, we have 90 minutes and then the students would have STEM time and they'd have to go home. So, that is a concern of mine.

Despite entering a new school year (2022–2023) without remote instruction, we find these perceptions have remained unchanged as leaders continue to adjust to a new normal.

It should also be noted that all states and districts received Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds through the Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. These funds sought to ease the burden amid rapidly changing conditions. For instance, ESSER funding became vital to Hamilton, especially during the transition back to in-person instruction in fall 2020. As the superintendent (D04_B01_A01) went on to say: “The federal [ESSER] funding has really made a difference for us during the transition, particularly around things like PPE.” In contrast, Washington leaders acknowledged that ESSER funds were helpful, but not necessary to their survival.

State and Local Guidance

Because federal guidance was relatively absent, most education guidance was handed down to school districts via states (Grossmann et al., 2021). In Illinois, we found the Governor's Office/ISBE/IDPH sent out substantial guidance between March 12, 2020, and September 3, 2020, in the form of executive orders, letters, minutes, and packets. Meanwhile, no formal documents were issued by both districts’ ISA. Instead, “Resources for Covid-19” were made available, with pages providing numerous links for families and teachers to support students during school closures and other COVID-related needs (e.g., professional development, subject-specific assistance, instructional recommendations, technology support). Other ISA technical support came in the form of frequent webinars or phone calls with district leaders, as Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) confirmed: “I was just on before you and I jumped on [Zoom]. Every single Monday, our ISA, which is our regional office of education here in [BLINDED], they lead a meeting with all 66 districts, which is super helpful.” We similarly did not find any county-level health guidance, as this guidance simply mirrored the IDPH. Please see Table 4, which outlines the different forms of guidance and their frequency over the six-month document collection period.

Table 4.

Frequency of Guidance From State-Level Sources March 2020 – August 2020.

| March 2020 | April 2020 | May 2020 | June 2020 | July 2020 | August 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL Executive Order | X X X X X | X X | X X | X | ||

| ISBE Supt Letter | X X X X X X X X | X X X X X X | X X X X | X X | X | X X |

| ISBE Joint Guidance | X | X | X X | X | X | |

| ISBE Board/Finance Committee/Ed Policy Committee Minutes | X | X X | X X X X | X X X | ||

| Local (ISA or County) | ||||||

| Other | X X X X | X | X X X | X X X |

During our collection period, Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker issued 10 executive orders to districts, starting with the school closures and ending with the transition back to in-person for the 2020–2021 academic year. Most of this guidance was reasonably tight and revolved around public health (e.g., masking and social distancing). On the other hand, we found 23 letters from the Superintendent of Schools, six substantial “Joint Guidance” documents from ISBE etc., and 11 other documents that augmented prior state-level guidance. Unlike executive orders, these documents were rather loose in favor of local control. That said, district and school leaders with whom we spoke cited the need for tighter state-level guidance. As one Hamilton principal (D03_B02_P01) best pointed out:

I do understand pushing for [looser state-level guidance] to make local decisions, but it really would be nice during a pandemic to have our Illinois top leadership make some decisions that districts could guide themselves off of, so that there’s some sense of equity in experiences in learning.

Despite the desire for more state-level sensegiving, we found ISBE's Joint Guidance documents to be the most influential. Developed in consultation with ISAs and as many as 64 school district employees across the state, these documents sought to loosely guide K-12 public health and instructional practices. The first of these documents—“Remote Learning Recommendations During COVID-19 Emergency” (March 27, 2020)—provided recommendations for both instruction and grading for every grade-level and specific subgroups. The second—“Part 1—Transition Plan—Considerations for Closing the 2019–20 School Year & Summer 2020” (May 15, 2020)—provided additional guidance and recommendations on a variety of topics (e.g., attendance, grading, learning loss, social-emotional supports, summer school, professional development, device distribution). The third—“Part 2—Transition Joint Guidance—Updated Summer School and Other Allowable Activities" (June 4, 2020)—provided information on allowable activities inside of schools and specifics with respect to health and safety protocols. The fourth—“Part 3—Transition Joint Guidance—Starting the 2020–21 School Year” (June 23, 2020)—provided district leaders guidance for transitioning to in-person learning, with recommendations for instruction as well as family communication, blended (or hybrid) learning days, scheduling, student/staff attendance, and health/safety protocols. The fifth—“Fall 2020 Learning Recommendations” (July 23, 2020)—sought to further clarify blended, remote, and in-person learning arrangements. The sixth and final substantial release—“Illinois Priority Learning Standards” (August 24, 2020)—outlined the priority learning standards, critical concepts, and instructional guidance that would serve as a “starting point for discussion on prioritization of learning standards at the local district level” (p. 4). Taken together, these six releases provided a documentary foundation from which to examine in greater detail local K-12 sensemaking and subsequent responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Please see Table 5 further detailing ISBE Joint Guidance.

Table 5.

ISBE Joint Guidance Descriptions.

| ISBE Joint Guidance 1 March 2020 |

ISBE Joint Guidance 2 May 2020 |

ISBE Joint Guidance 3 June 2020 |

ISBE Joint Guidance 4 June 2020 |

ISBE Joint Guidance 5 July 2020 |

ISBE Joint Guidance 6 August 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 District Consultants | 28 District Consultants | 55 District Consultants | 56 District Consultants | 58 District Consultants | “Diverse and skilled team of Illinois Educators” |

| - Grading Recommendations - Instructional Recommendations - PreK-12/Subgroups |

- Attendance - Grading - Learning Loss - SEL - Summer School - Professional Dev. - Device Distribution |

- School Activities - Health/Safety Protocols (across settings) |

- Transitioning to In-Person Instruction - Family Communication - Blended Learning - Scheduling - Student/Staff Attendance - Instructional Recommendations - IDPH Protocols |

- Instructional Recommendations for Blended, In-Person, or Remote Environments | - Prioritized Standards - Priority Standards - Critical Concepts - Instructional Guidance - 9 Subjects |

Highlighting the importance of maintaining local control, the joint guidance authors stated that districts should “weigh these recommendations in light of the reality of their local contexts …” (p. 7). This was further reinforced by both Washington and Hamilton leaders with whom we spoke. As one Hamilton principal (D04_B02_P01) best illustrated:

The last line in their [joint] guidance has always been “based on district-level discretion,” so they're putting a lot of parameters out there and saying, “This is what we see as best, but not hard line,” so every district seems to be doing something very different, and it’s kind of challenging because everybody's putting in the same amount of work and coming up with different products… instead of working smarter, everybody's working a lot harder because of the fact that they're just giving us guidance.

Although most documents were collected between March and August 2020, we must acknowledge the rise of the COVID-19 delta variant during summer 2021 resulted in some additional guidance. For instance, a set of letters sent to Governor Pritzker authored by the Office of State Representative Lewis and 350 school leaders cited some “unresolved [guidance] issues that must be addressed before education professionals can effectively implement their planning for the 2021-2022 school year” (Lewis 2021). These pleas propelled mask and vaccination requirements by the Governor's Office in August 2021 (Executive Order No. 2021-20). Health recommendations were also reduced from six feet to three feet in supporting the transition back to in-person learning (given different classroom footprints amongst schools). And most recently, all state-level health and instructional guidance has been rescinded for the 2022–2023 school year. This shift mirrors most states and districts at the present time (Blake, 2022), including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance.

Confluence of External Guidance and Internal Capacities on District and School Leader Responses

Common with any sudden crisis, we find Washington and Hamilton’s leaders operated in “survival mode” due to rapidly changing conditions. And while state-level guidance from the Governor's Office and ISBE has been relatively comprehensive (see Grossmann et al., 2021), leaders feel that such guidance has often been too loose and/or untimely. Internally, this has placed increased stress and anxiety on both districts. It also necessitated leaders to lean on (a) boundary spanning for advice and (b) funneling loose guidance for other staff.

Loose and/or Untimely Guidance

With the exception of one leader, most (15/16) felt the state-level guidance was too loose and/or untimely, increasing their stress/anxiety. As Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) revealed early on in spring 2020:

The Governor figured we’re going to give schools what they always ask for, which is local control, and each one, it's up to them to make those decisions… [But] I think my frustration with ISBE like everyone else is just, all of a sudden, [the guidance] comes out. There's nothing, nothing, nothing, and then it's four o’clock on a Friday, here's a 75-page document for you to figure out, and it has to be in place by Tuesday. So, that part has been frustrating … locally having to figure out things. It's created a lot of anxiety for administrators to not really be able to plan or know what's coming next. It's been a lot of support from within house, and it's put a lot of decision-making on the local entities to make the decisions on what they’re going to do and what school's going to look like this year.

Indeed, such stresses only continued once schools began transitioning back to in-person in 2020–2021. Operating under local control and its added frustration, the superintendent went on to say the following:

Schools are on their own to make decisions under these [state] guidelines. So, no, we haven’t really gotten much from them … It wasn’t really quite the [state] guidance we were all expecting during the pandemic. We are not the health experts here … [And, this year], many districts in August [2021] had made the decision that we’re going to make masks optional… but now that we didn’t do what [Illinois] wanted … we’re going to require masks. If they were going to require masks, just do it from the beginning, so we’re not spending hours and hours our staff's time trying to figure out how we can fit within loose guidance, only to then be told well “too bad” we’re going to do this [other option] anyways.

However, these stresses remain unclear for the 2022–2023 school year, as state-level guidance has been rescinded. This accounting by the superintendent is reflective of such uncertainly: “Everything goes back to normal when we start next school year. Regardless of where we are at. But sometimes that is not a superintendent's call, as much as we think it is.”

Boundary Spanning for Advice

Because Washington and Hamilton’s administrators initially lacked internal expertise, we found they have relied on a wide variety of external stakeholders (or boundary spanners) for advice—including other districts/leaders, social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Voxer), and associations (e.g., Illinois Principals Association, Illinois Association of School Administrators). These networks were different for each leader, but similarly enabled them to rapidly make sense of information for their respective organizations. One Hamilton principal (D04_B02_P01) with whom we spoke best describes some of these advice networks:

[To make sense of the state-level guidance] we rely a lot on each other, as admin., but I also have created a Voxer group for Illinois administrators, and so they’re principals and assistant principals, and a lot of great feedback has come there with the share-outs through that Voxer group. Twitter naturally, too, constantly learning a lot from there. Those are really the grassroots groups … we’re learning a lot from each other and, what are you doing in this situation, or where are you at with this or even just updates of what's coming up. And you're hearing things from other states or other districts doing this and that. So we were trying to pick and choose the things that we think for sure we’re going to need. The summer [of 2020] was interesting. The days flew by because you knew that there was just so much more that you were unsure of and had to plan for.

In the process, leaders in both districts felt a collective push to meet the challenges posed by COVID-19. Rather than competing, leaders where collaborating in ways that otherwise would not have taken place. But with new information came the need to properly utilize and message it across internal stakeholders.

Funneling Loose Guidance for Other Staff

Given the need to make sense of state-level guidance locally, we find superintendents have become critical funnels and buffers of external information for their districts and personnel (Honig, 2012). As one Washington principal (D03_P02_P01) went on to say about their superintendent: “I don’t necessarily rely on ISBE, they’re not necessarily my guiding decision-maker because that's more the role of [my superintendent who] filters the impact of those [guidance] decisions on our district, and I handle it at the school-level.” Notwithstanding, this has required extensive preparation, information gathering, and collaboration by district heads (see Smith & Riley, 2012). As Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) best pointed out:

The summer [of 2020] was crazy. So we created a team, it was, I think, 42 members this summer, that had teachers, and paraprofessionals, and parents, and board members and administrators, and everyone had a subgroup they were part of. So, I would start off by leading that meeting. We met like every two weeks. I think we met five times, and then they would be sent out into their breakout rooms, and I was just observing and answering questions.

In sum, external factors like loose state-level guidance impacted whether and how leaders made sense of and responded to the sudden crisis. Meanwhile, internal factors like leader expertise proved vital. Lacking such expertise early on, however, we find leaders leaned on external boundary spanners (i.e., ISAs and other K-12 leaders) to help make more informed decisions, while also funneling these decisions across internal stakeholders. In tracing the intersection between external policy guidance and internal organizational capacities, we, therefore, present three different scenarios experienced by our case districts: (1) remote learning, (2) public health, and (3) curriculum implementation.

Remote Learning

In response to the Governor's executive order (No. 2020-05) closing schools in March 2020, the initial Joint Guidance from ISBE was related to remote instruction. As mentioned, this guidance was rather loose given districts had varying technological capacities. Indeed, we observed such technological differences across our selected cases. On one hand, Washington had some initial expertise, fully implementing a remote learning system pre-pandemic for possible snow days. In turn, Washington leaders felt reasonably prepared at the beginning to make the immediate transition to fully remote instruction, as Washington's assistant superintendent (D03_B01_A03) pointed out:

I think we had a leg up on many other [Illinois districts] just because we had already assembled this remote learning plan for snow days. And then we were able to pretty quickly scale it to everyone and across the board everyday. And then eventually grow it because there were things that we appreciated or learned, and then we're able to take it from there. There were some lumps, of course, in terms of the amount of time that we can have kids in front of screens, but I think what we've got reflects the vast majority of what they need. And I think we're able to successfully get that through to them instructionally.

These comments were further reinforced by teachers who reflected on their expereinces two years later: “[Washington] did about as good a job as you could ask for … we felt prepared to meet remote learning head on … and if we ever have to go back again, we’re ready” (D03_B05_T44). CALL data also showed the district's “monitoring teaching and learning” was almost two standard deviations above the national mean (3.64) in spring 2020.

At the same time, we find these initial technological investments were further supported by human capacities. Notably, Washington employs a large cadre of technology coaches and paraprofessionals. This made the sudden transition from in-person to remote in March 2020 (and for the rest of the academic year) relatively smooth, as these individuals were able to train and/or assist teachers in adapting their instruction. One assistant principal's (D03_B03_P04B) comments best illustrate this point:

We’ve worked really hard with our tech. coaches to work with the staff on different pieces of response-type software that would assist them in teaching [remotely], which I think were instrumental in at least trying to replicate what was in the classroom. You can’t ever create that again, but just doing our best to provide the students with anything that they would need to assist them in being successful, I think has been really key … We also have paraprofessionals in breakout rooms to facilitate some of the learning and to monitor the independent work, because developmentally, kindergartners and first graders and even some second graders to all of a sudden be expected to be at that level of independence remotely developmentally isn't quite there.

Given such technological support structures, Washington teachers with whom we spoke felt less overwhelmed about remote instruction in spring 2020. These perceptions continued throughout the 2020–2021 school year (which also began remote). As another assistant principal (D03_B04_P03C) went on to say: “… concerning technology, teachers haven't reached out for anything anymore. It seems like it's been going okay [now].”

In contrast, Hamilton did not have the same technological resources or expertise, placing them at an early disadvantage. For example, the district did not have a remote learning system for possible snow days, necessitating a quick transition in March 2020. The district was also not quite “one-to-one,” requiring some additional logistics to provide laptops to all students. Finally, Hamilton did not have the dedicated personnel to train or assist teachers. School leaders subsequently had to improvise and take over this support role to help their staff through the transition. As one assistant principal (D04_B02_P01B) with whom we spoke shared: “I’ve become more of a technology specialist because there are parents, and students, and staff that need that assistance … So, I feel like my roles have shifted a little bit with that.”

Due to the change in role and increased technological responsibilities, most Hamilton leaders said they were overwhelmed at the beginning of the pandemic. As Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) went on to say: “I've never worked that hard in my life … I'm embarrassed to say it, but I was not at the forefront concerning how do we get a [remote] model to work where we're … still instructing students.” Such sensemaking was similarly reflected by teachers; CALL survey data showed respondents felt “monitoring teaching and learning” was almost two standard deviations below the national mean (3.1) in spring 2020. And despite some teacher professional development at the beginning of the 2020–2021 school year, without a permanent specialist, school leaders continued to shoulder this technology role. In describing this stressful situation, one assistant principal (D04_B04_P03B) said:

I find myself so stressed because I have so many teachers who are asking [remote technology] questions and need help with things and I can’t help them because I just can’t. One, because I just don’t have the resources to do so, or just I don’t have the information and I'm that person that you give me a challenge or a problem, I’m going to want to try to fix it.

It is important to note that both districts returned to fully in-person instruction for the 2021–2022 school year, and now feel prepared to transition to remote learning at any time. Nevertheless, Hamilton's limited expertise and organizational resources early on made the sudden transition more difficult than Washington. This finding is best illustrated by Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01):

So if your district has money, and you're able to have these big buildings and more technology … you’re able to maybe run more in person classes and kids are there full time. I mean, I don’t care what anybody says, they’re learning way more in school than they are outside of school.

Public Health

While state-level guidance was relatively loose concerning remote instruction, public health guidance (e.g., masking, social distancing) became tighter once in-person/hybrid learning resumed during the 2020–2021 school year. Much of this external guidance has come directly from the IDPH rather than local (i.e., county) health departments. Consequently, we find leaders have not had to make sense of such external guidance to the same degree as remote instruction, which was welcomed. As Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) pointed out:

I would say in just about every other instance, I would love local control. But how much of this has to do with education is debatable. It's really more of a scientific decision, that I don't know how equipped I or any other school person at leadership is equipped to make.

Acknowledging their lack of public health expertise related to COVID-19 prevention, IDPH's tighter guidance gave leaders some relative sense amid rapidly changing conditions.

That said, some of this external guidance remained loose in terms of its implementation. For example, although a six feet distance between all teachers, students, and staff was required for the 2020–2021 school year, the state did not provide guidance on how to execute such restrictions. In this way, K-12 leaders still became critical street-level bureaucrats for their respective organizations. In describing these challenges, one Washington principal (D03_B04_P03) with whom we spoke said:

They’ll tell us, “You can't have 50 kids.” or “If your room isn’t yea big, you can’t have so many people in a room.” But they don’t tell you what you can do. They don’t say, “So, if you have lunch or recess and you’re already at a max number, here's some suggestions.” They’re not saying that … So we had to go back to the drawing board and come up with some creative ways to do this.

At the same time, state guidance was constantly changing as the 2020–2021 school year began, requiring districts to routinely gather information, adapt, and make rapid decisions (see Smith & Riley, 2012). As one Hamilton principal (D04_B02_P01) further revealed:

I think we’ve done our best in the timeline that we’ve had. At times, things definitely felt rushed … changes [to guidance] were being made very, very quickly, especially at the beginning of the [2020-2021 school] year from the state and the IDPH, so we had to adapt, we had to be flexible. There were many times at the beginning of the school year where we created two, three different schedules, even until this day, we’re still looking at creating different schedules to meet possible changes in the future. So, this year, we’ve gone through three different schedule changes, and we’ve never had to do that.

Because of such rapidly changing conditions, local sensemaking proved precarious (albeit in different ways than remote instruction). To help mitigate, Washington relied on an internal team of lawyers to help interpret and direct safety decisions, as the assistant superintendent (D03_B01_A03) went on to say:

Some of [the guidance] has definitely been open to interpretation, just having to follow up with our lawyers to make sure that we’re following the guidelines accurately. They provided, especially in the early fall [2020], a lot of, “This is what this means, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah,” types of pieces of information. [But] there have definitely been some gray areas that I feel like our district needed to understand, wrap our heads around, and work through. So has [guidance] been the clearest? No … I can't fault them completely for that, but I definitely think there's been some gray areas making things more difficult.

In turn, Washington stakeholders with whom we spoke felt there was a coherent line of communication throughout the organization. These efforts to implement a safe learning environment were also supported by CALL data; compared to most districts nationally, Washington was found to be two standard deviations (4.01) above the mean. Acknowledging such effectiveness and fortune, Washington's assistant superintendent said:

There is a level of [COVID-19] being very uncomfortable simply because I'm not a healthcare provider, but I feel like we have such great communication across the district, and we are very fortunate we do have a tremendous amount of resources, so we were able to make things [during the pandemic] work. I think that the way it works [with guidance] here maybe doesn't work the same way in another school district; not every school district has the exact same resources or the exact same capabilities.

Conversely, Hamilton did not have such a team, instead relying on administrators, staff, and teachers to make snap decisions in real time. These circumstances resulted in local stakeholders making sense in different ways. For instance, Hamilton stakeholders felt safe to varying degrees once in-person learning began in fall 2020. The teacher's union sent out a climate survey a month after the transition (Dec. 2020), and according to the superintendent (D04_B01_A01), most teachers did not feel the district was doing an adequate job to protect their staff from COVID-19 (while ensuring quality instruction). In discussing this situation, the superintendent (D04_B01_A01) said the following:

In December 2020, the union had actually given a survey out, and I would say that was the low point. I think one building only had 33% of their staff who said they felt safe. Then another building had only 20%, and then another building had 60% … This year, it seems like every single thing you try to do comes with a whole set of problems, some anticipated, some not. Nothing just goes through like it normally would in the past.

Given these circumstances, the union pushed for substantial changes around school safety, as the superintendent went on to say:

We did some give-and-take [to alleviate these stresses], and just understanding that people are terrified of this [crisis], and I think people who aren’t in a school forget that. I mean, we’ve seen 30 cases of teachers getting coronavirus [in fall 2021]. There's been no cases that have been linked in the schools, but that's still 30 people who’ve been in our schools, and that doesn’t even count the students. So, I think it's understanding where some of that fear comes from is really important when we have those conversations.

However, this put a lot of stress on building-level leaders specifically, as they had to take on many roles that otherwise would not exist, including contact tracing and wellness checks with remote students. One assistant principal's comments (D04_B04_P01B) best describe these operational challenges: “I feel like I'm just like the doer of all … So it's a struggle just to manage that … kind of having nothing that's stable, like consistent; I'm just the doer of everything, all the time … that's the worst part [of the crisis].”

We find these challenges were further tied to the actual facilities both districts operated within. Due to the six feet mandate in 2020–2021, classroom square footage became important. This finding was best captured by one Hamilton principal (D04_B04_P03B) with whom we spoke:

I think it's unfair for ISBE to give us those hard lines [for social distancing) because every school district, every community, every building even within a district, our rooms are different, so the size of our rooms are different, even within a building the size of the rooms are different. So, if they really came out and say no more than 10 kids in a classroom, for our school, that's a full capacity, whereas if you have another school, they might be able to fit an extra five to 10 kids with six-foot social distancing; at the junior high, they might not be able to even fit 10.

Unable to maintain social distancing at full capacity, Washington and Hamilton had to resort to different in-person scheduling models. Having the good fortune of larger classrooms, Washington only had to reduce in-person instruction time by one hour each day. Alternatively, Hamilton's smaller classrooms required a more nimble strategy. The district eventually settled on an AM/PM hybrid model, which was borrowed from another district superintendent (via boundary spanning). This meant students only received in-person, synchronous learning for half the school day—far less than Washington. In describing this decision, Hamilton's superintendent (D04_B01_A01) said:

I remember, I called someone, a superintendent from North Shore that I met at one of the conferences and, I mean, they have money coming out of everywhere, so some of the things they can do, we just can’t. But it was my conversation with them that convinced me we could do this AM/PM model that we [now] have. So, that really has been where we get everything from, is from the other districts.

During the 2021–2022 year, however, the state-level guidance was amended. Instead of a six feet distance, schools only had to maintain three feet. This allowed Hamilton and Washington to resume their normal, pre-pandemic school schedules. As another Washington principal (D03_B05_P04) with whom we spoke shared:

The three feet rule really made a big difference for us, especially in the lunchroom. That was our biggest obstacle last year was feeding the kids lunch, and that was why we weren't able to have them in full day because we had nowhere to feed them.

Furthermore, beginning fall 2022, all social distancing mandates have been rescinded (including masking). This means the 2022–2023 school year will be the first time since the pandemic began that such restrictions have not been in place.

Concerning public health, we find organizational resources have played a significant role in making sense of and responding to tighter state-level guidance. Because physical space was limited, both districts had to limit their in-person instruction time during the 2020–2021 school year (though Washington to a lesser degree). So despite district leaders being provided with some expertise, gray areas within the guidance heightened street-level bureaucracy until spring 2022 when mandates were lifted by court order (see Austin v. The Board of Education of Community Unit School District 300).

Curriculum Implementation

Similar to remote instruction, Illinois’ curriculum guidance was fairly loose. Notably, the state provided essential learning standards for each grade-level as part of its sixth and final joint guidance document (August 2020). These standards were disseminated to “mitigate the added stress and pressure placed on educators and students” by focusing on the standards that had “the greatest positive impact on learning” (Illinois Priority Learning Standards, 2021, p. 5). We found leaders particularly appreciated these standards amid rapidly changing conditions. One Washington principal's (D03_B03_P02) accounting best exemplifies this point: