Abstract

Objective

To use scoping review methods to construct a conceptual framework based on current evidence of group well-child care to guide future practice and research.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) six stages. We used constructs from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and the quadruple aim of health care improvement to guide the construction of the conceptual framework.

Results

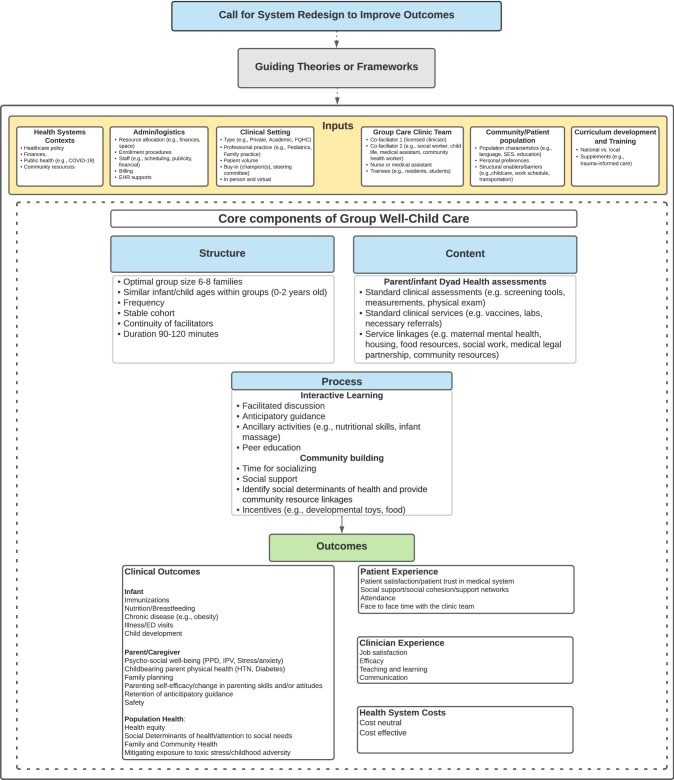

The resulting conceptual framework is a synthesis of the key concepts of group well-child care, beginning with a call for a system redesign of well-child care to improve outcomes while acknowledging the theoretical antecedents structuring the rationale that supports the model. Inputs of group well-child care include health systems contexts; administration/logistics; clinical setting; group care clinic team; community/patient population; and curriculum development and training. The core components of group well-child care included structure (e.g., group size, facilitators), content (e.g., health assessments, service linkages). and process (e.g., interactive learning and community building). We found clinical outcomes in all four dimensions of the quadruple aim of healthcare.

Conclusion

Our conceptual framework can guide model implementation and identifies several outcomes that can be used to harmonize model evaluation and research. Future research and practice can use the conceptual framework as a tool to standardize model implementation and evaluation and generate evidence to inform future healthcare policy and practice.

Keywords: Group well-child care, Group care, Pediatric primary care, Preventive medicine/methods, Maternal and child health

Significance

What is already known on this subject? Group well-child care (GWCC) is associated with improved healthcare utilization (e.g., attendance, immunization rates), parent outcomes (e.g., psychological well-being, satisfaction), and clinician outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy).

What this study adds? Scoping review methodology was used to generate a conceptual framework of GWCC which can be used as a guide to standardize practices for implementation, evaluation, and research in GWCC.

Introduction

Well-child care provides a critical window of opportunity to identify and manage health and social challenges and promote child and family health. Given how tightly linked a childbearing parent’s postpartum health is to infant well-being, current postpartum and early childhood preventive care models are not optimal in that many families, particularly those from groups that have been minoritized, do not receive recommended preventive services, and/or are left with unfulfilled needs (e.g. unmet health-related social needs, unaddressed parental depression) (ACOG, 2018; Coker et al., 2013; Fahey & Shenassa, 2013; Freeman et al., 2018; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019). As a result, there are significant racial gaps in child developmental outcomes (Liljenquist & Coker, 2021). To address the unmet needs and improve outcomes for families particularly in underserved areas, various redesigns of well-child care have been proposed, including group well-child care (GWCC) (Coker et al., 2013; Schor, 2004).

In place of standard individual visits, GWCC offers care to multiple infant-parent dyads or triads at once. Most GWCC models bring together the same group of 6–8 parents and their infants, who are born within one month of one another, for one to 2 years of preventive care visits (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Gaskin et al., 2021). In general, sessions are 120 min with the first 30–45 min consisting of standard health assessments of the infant and caregiver, by a clinician in a semi-private section of the room, followed by 75–90 min of group discussion using interactive health promotion activities (Bialostozky et al., 2016; Connor et al., 2017; DeLago et al., 2018; Friedman et al., 2021; Marchel et al., 2015).

GWCC is associated with improvements in healthcare utilization (e.g., attendance, immunization rates) and with parent and clinician satisfaction (Desai et al., 2019; Fenick et al., 2020; Graber et al., 2019; Gullett et al., 2019; Irigoyen et al., 2020; Johnston et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2018; Machuca et al., 2016; Page et al., 2010; Platt et al., 2022; Rice & Slater, 1997; Rosenthal et al., 2016; Rushton et al., 2015). Clinicians have also described the potential impact of GWCC to shift power dynamics and improve quality of care (Desai et al., 2019; Lazar et al., 2021). A recent systematic review describes GWCC as an efficient model that is patient-centered, influences outcomes, and has the potential to meet the needs of underserved populations (Gaskin et al., 2021). However, authors noted inconsistencies in model implementation and lack of standardization in assessing outcomes, making interpretation of the results challenging. Therefore, using scoping review methods, we sought to construct a GWCC conceptual framework based on current evidence to serve as a tool for practitioners and researchers to guide model implementation and harmonize GWCC practice, evaluation, and research.

Methods

We mapped key concepts related to GWCC through a systematic search and synthesis of existing knowledge to construct a conceptual framework (Colquhoun et al., 2014). We chose scoping review methodology to inform conceptual framework construction because the approach allows for the inclusion of all types of research (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods), reviews, and commentaries and expert consultation. Following recommendations of Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010 enhancements, our review stages included: identifying the research question and relevant studies, study selection, charting, collating, and summarizing the data, reporting results, and completing a consultation exercise. Our research question was: “what is known from the existing literature about the conception, implementation, and outcomes of GWCC?” We worked with a research librarian to develop search terms (Appendix 1) and conducted a systematic search of Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, APA PsychInfo, Web of Science, and Scopus. Search terms included variations of group well-child care and CenteringParenting (a standardized GWCC model). There were no limitations related to publication date or language.

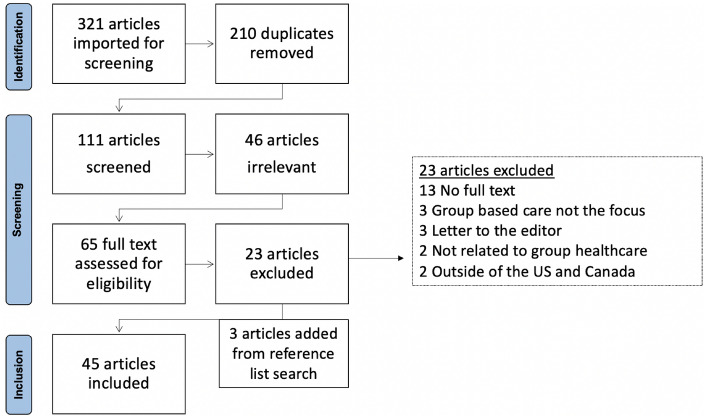

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined iteratively between three team members (Colquhoun et al., 2014). Studies were included if they specifically referred to GWCC and were available in full text. Two team members screened titles and abstracts; a third team member was consulted if consensus could not be reached; three team members subsequently conducted the full text review. We also hand-searched references listed in included articles. Team meetings were held to refine the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In these meetings we decided to exclude studies outside of the US and Canada as the literature outside of these countries includes some reference to continuing group care in the postpartum period, but often did not go past 6 weeks postpartum, and due to the many differences in the health care systems. Figure 1 describes the search stages.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Three team members independently extracted data using Covidence systematic review software’s data extraction template and discussed interpretation of variables extracted (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021). The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model tools for research evidence appraisal were used (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). For the process-oriented data, a qualitative content analysis approach was used to extract data (Colquhoun et al., 2014). Data from the extraction tool were collated to summarize and report results. We used two existing frameworks to organize outcomes and guide the development of the conceptual framework, including: (1) the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009), which consists of theory-based constructs (e.g., inner and outer setting, intervention characteristics, and process) associated with effective implementation of interventions, and (2) the quadruple aim of health care improvement (improved clinical outcomes; improved patient experience; improved clinician experience; and reduced per capita cost of healthcare) (Berwick et al., 2008; Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014; Sikka et al., 2015).

The draft GWCC conceptual framework was circulated to the larger study team consisting of the founder of CenteringParenting, three practitioners in GWCC, and four researchers. The team refined the framework over a series of meetings. We then sent the framework to 14 additional experts (11 pediatricians, 2 social workers, and 1 child life specialist with experience in implementation of, or in research on, GWCC models). All experts reviewed the framework, verified findings, and provided feedback (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The framework was finalized by the study team as a whole.

Results

A total of 45 articles were included in the review. Study designs included quantitative (n = 18), qualitative (n = 13), and mixed methods (n = 5). Nine non-research publications were included. The results present in narrative and table form the findings from the scoping review that led to the construction of the conceptual framework (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

GWCC conceptual framework

We present the mapped domains and key concepts in the framework which align with the CFIR constructs and the quadruple aim.

Call for System Redesign to Improve Outcomes

GWCC was often implemented in response to health system constraints in traditional care (e.g., lack of time, limited opportunities to address psychosocial topics) and to more efficiently address family needs (Anderson, 2006; Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Friedman et al., 2021; McNeil et al., 2016; Osborn, 1982; Page et al., 2010; Stein, 1977). Most of the GWCC literature describes it being implemented in underserved patient populations (Gaskin et al., 2021). Several studies reported that implementation of GWCC was aimed at addressing specific stressors more effectively (e.g., low health literacy, unmet social needs) or to deliver care to a particular population (e.g., children in immigrant families) (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Friedman et al., 2021; Platt et al., 2022).

Guiding Theories or Frameworks

Theories or frameworks supporting rationale for GWCC model design and curriculum development were identified in six articles (Bialostozky et al., 2016; DeLago et al., 2018; Machuca et al., 2016; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; Oldfield et al., 2019; Rushton et al., 2015). These included adult learning theory (Rushton et al., 2015), experiential learning theory (DeLago et al., 2018), Weisner’s ecoculturalist theory of human development (Bialostozky et al., 2016), transtheoretical model of change (Machuca et al., 2016), social learning theory (Machuca et al., 2016), Freirean framework (Machuca et al., 2016), Anderson’s model of health services utilization (Oldfield et al., 2019), the Behavior Change Wheel framework(MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019), and the Capacity, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior system (MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019).

Inputs

Similar to the CFIR constructs of inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals and process (Damschroder et al., 2009), the inputs referred to below describe the economic, political, financial, and structural contexts and processes and individuals that influence the implementation of GWCC. Table 1 provides more details for each key concept.

Table 1.

GWCC conceptual framework domain: inputs

| Domain and concepts | Description from the literature | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs | ||

| Health systems context | National and state healthcare policies | Connor et al., (2017), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016) |

| Financial: funding, payers, and government agencies | ||

| Public health: COVID-19 pandemic | Expert consultation | |

| Community resources | Expert consultation | |

| Administration/logistics |

Critical resources needed: Space Personnel (e.g., group care coordinator, group facilitators, support staff) for program coordination, scheduling, and billing |

Anderson (2006), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Castellan et al., (2020), DeLago et al., (2018), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), McNeil et al., (2016), Novick et al., (2020), Osborn (1989), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Page et al., (2010) |

|

Enrollment procedures: Opt-out enrollment At the end of pregnancy (some as a continues to CenteringParenting) Advertisement with flyers During postnatal hospitalization Postpartum visits At first or second well-child visit |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Friedman et al., (2021), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Machuca et al., (2016), Novick et al., (2020), Osborn (1989), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Page et al., (2010), Saysana and Downs (2012), Stein et al., (2005) | |

|

Financial considerations Clinician productivity Billing Up-front costs with implementing a new model of care |

Anderson (2006), Connor et al., (2017), Irigoyen et al., (2020), McNeil et al., (2016), Yoshida et al., (2014) | |

| Clinical setting |

Type of setting Private pediatrician office Outpatient pediatric primary care clinic Community or federally qualified health center Academic pediatric practice Hospital-based clinics Community-based facility Resident training practice (i.e., continuity clinic) Public health clinic Family medicine residency clinic Multi-specialty group |

Anderson (2006), Bialostozky et al., (2016), Castellan et al., (2020), Connor et al., (2017), DeLago et al., (2018), Dodds et al., (1993), Fenick et al., (2020), Friedman et al., (2021), Graber et al., (2019), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Machuca et al., (2016), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016), Mittal (2011), Novick et al., (2020), Oldfield et al., (2019), Osborn (1982), Osborn (1989), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Page et al., (2010, 2013), Platt et al., (2022), Rice and Slater (1997), Rosenthal et al., (2014, 2016), Rushton et al., (2015), Saysana and Downs (2012), Shah et al., (2016), Taylor et al., (1997b), Taylor and Kemper (1998), Yoshida et al., (2014) |

|

Type of professional practice Pediatric medicine Family medicine |

Anderson (2006), Bialostozky et al., (2016), DeLago et al., (2018), Dodds et al., (1993), Friedman et al., (2021), Graber et al., (2019), Gullett et al., (2019), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Machuca et al., (2016), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016), Mittal, (2011), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Page et al., (2010, 2013), Platt et al., (2022), Rosenthal et al., (2014, 2016), Rushton et al., (2015), Saysana and Downs (2012), Stein (1977), Stein et al., (2005), Taylor et al., (1997a, 1997b), Taylor and Kemper (1998), Yoshida et al., (2014) | |

| Patient volume | Jones et al., (2018) | |

|

Institutional buy-in Program champions Steering committee Institutional leadership |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Friedman et al., (2021), Jones et al., (2018), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016), Novick et al., (2020), Osborn (1989) | |

| In person and virtual | Expert consultation | |

| Group care clinic team |

Type of facilitator Pediatricians Family practice provider Registered nurses/public health nurses Advanced practice registered nurses (family nurse practitioners, pediatric nurse practitioners) Physician’s assistants Social workers Medical assistants Trainees (e.g., residents) Centering coordinator Case manager Patient advocate Nutritionist Child life specialist Infant mental health specialist Community health workers Type of guest speakers/ facilitators Certified nurse midwives OB/GYN Dietician Health educator Psychologist Lactation specialist Physical therapist Parenting coaches |

Anderson (2006), Bialostozky et al., (2016), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Castellan et al., (2020), Delago et al., (2018), Desai et al., (2019), Dodds et al., (1993), Fenick et al., (2020), Friedman et al., (2021), Graber et al., (2019), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Liebert (2016), Machuca et al., (2016), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016), Mittal (2011), Novick et al., (2020), Oldfield et al., (2019), Osborn (1982), Osborn (1989), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Page et al., (2010, 2013), Platt et al., (2022), Rosenthal et al., (2014, 2016), Rushton et al., (2015), Saysana and Downs, (2012), Shah et al., (2016), Stein (1977), Taylor et al., (1997a, 1997b), Thomas et al., (1984), Yoshida et al., (2014) |

| Community/patient population |

Population characteristics Racially and ethnically diverse populations Low income or low socio-economic status New immigrant caregivers Language: Spanish, English Insurance: public and private |

Bialostozky et al., (2016), Castellan et al., (2020), Delago et al., (2018), Fenick et al., (2020), Friedman et al., (2021), Graber et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Machuca et al., (2016), Mittal (2011), Oldfield et al., (2019), Osborn (1989), Platt et al., (2022), Rice and Slater (1997), Saysana and Downs (2012), Taylor and Kemper (1998) |

|

Patient preferences Desire for group visits or individual visits Privacy concerns Concerns of comparisons across families |

Connor et al., (2017), Osborn (1989), Yoshida et al., 2014) | |

|

Structural enablers/barriers Scheduling Work Time Childcare for siblings |

Friedman et al., (2021), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Platt et al., (2022), Taylor et al., (1997b) | |

| Curriculum development and training | National vs. local | Expert consultation |

|

Description of the model: CenteringParenting |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Castellan et al., (2020), Connor et al., (2017), Desai et al., (2019), Fenick et al., (2020), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), McNeil et al., (2016), Mittal (2011), Novick et al., (2020), Platt et al., (2022) | |

| Adapted CenteringParenting | Delago et al., (2018), Friedman et al., (2021) | |

| GWCC | Anderson (2006), Bialostozky et al., (2016), Dodds et al., (1993), Gaskin et al., (2021), Marchel et al., (2015), Oldfield et al., (2019), Osborn (1982), Page et al., (2010), Rice and Slater (1997), Rosenthal et al., (2014), Saysana and Downs (2012), Shah et al., (2016), Stein (1977), Stein et al., (2005), Taylor et al., (1997b), Yoshida et al., (2014) | |

|

GWCC with supplements or enhanced curriculum Psychosocial well-being/mental health Vaccine refusal Toxic stress Nutrition Obesity Burn prevention Trauma-informed care |

Graber et al., (2019), Machuca et al., (2016), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), Rushton et al., (2015), Thomas et al., (1984) | |

|

Training Centering Healthcare Institute training 6 h training prior to start, and just-in-time team discussion in advance of each group visit and feedback after each session 1 h refresher training sessions quarterly to review how to address challenging situations |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Connor et al., (2017), Delago et al., (2018), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Jones et al., (2018), Mittal (2011), Yoshida et al., (2014) | |

Health Systems Contexts

Most of the included studies described health systems contexts affecting implementation of GWCC. Several studies emphasized the importance of supportive health and financial policies and funding for implementation success (Connor et al., 2017; Marchel et al., 2015). GWCC was described as aligned with US national health care reform efforts focused on using life-course perspective, optimizing efficiency, and family-centered care (Connor et al., 2017). Our expert reviewers identified additional health system contexts, (e.g., the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic requiring a shift to a virtual format or a cancellation of group visits). One expert highlighted the importance of understanding the community context in order to link families with community resources when necessary (e.g., food/nutrition benefits).

Administration/Logistics

Critical resources enabling GWCC delivery included space, personnel dedicated to program coordination, scheduling, and billing (Anderson, 2006; Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Castellan et al., 2020; DeLago et al., 2018; Gullett et al., 2019; Irigoyen et al., 2020; McNeil et al., 2016; Novick et al., 2020; Osborn, 1989; Page et al., 2010). Most studies noted the importance of having a room large enough to accommodate ~ 6–8 families and clinic team and include a semi-private area for health assessments, several studies described space as problematic (Anderson, 2006; Irigoyen et al., 2020; Osborn, 1989; Osborn & Woolley, 1981). Cost was identified as a concern in several studies (Connor et al., 2017; Irigoyen et al., 2020; McNeil et al., 2016); specific concerns included (1) potential impact of GWCC on clinician productivity and (2) up-front and ongoing costs for human (e.g., visit coordinator) and material resources needed for implementation. One cost-analysis outlined conditions (e.g., group size, clinician type) for cost neutrality of GWCC compared to individual care (Yoshida et al., 2014).

Clinical Setting

Across clinic settings, studies underscored the importance of program champions, staff and administrative buy-in, and institutional leadership for sustaining GWCC—through advocating for and committing resources to its continuation (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Friedman et al., 2021; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; McNeil et al., 2016; Novick et al., 2020).

Group Care Clinic Team

All models included at least one licensed clinician serving as a GWCC facilitator and care clinician. Some models had continuity of one or two facilitators while others relied on a single clinician, with rotating guest speakers facilitating specific topics. Interdisciplinary co-facilitation and the addition of non-medical providers (e.g., a child development specialist, or social worker) was reported to enhance well-child visits (Marchel et al., 2015). Groups were facilitated in multiple languages, primarily English and Spanish, and in some cases, experts described using interpreters.

Community/Patient Population

Factors that might lead families to prefer individual visits over group care included privacy concerns, a tendency for groups to invite comparisons between families, and a desire for more focused one-on-one time with clinicians (Connor et al., 2017; Osborn, 1989; Yoshida et al., 2014). Structural barriers and enablers to attending group visits are detailed in Table 1. Studies reported parity in patients’ time spent at the clinic (arrival to departure) for GWCC and individual care (Friedman et al., 2021; Osborn & Woolley, 1981; Taylor et al., 1997b).

Curriculum Development and Training

Table 1 includes curricula developed or utilized for GWCC. In addition to normal well-child care topics, curriculum development often focused on placing an emphasis on a specific content area based on context specific needs such as psychosocial well-being, vaccine refusal, toxic stress, nutrition, obesity, and burn prevention (Graber et al., 2019; Liebert, 2016; Machuca et al., 2016; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; Marchel et al., 2015; Platt et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 1984).

Training in the GWCC model varied. The Centering® Healthcare Institute training focuses on facilitation skills and the specifics of dyad care (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013). One expert described institution-specific training for GWCC. Some raised concerns about the skills needed to facilitate GWCC and believed most physicians’ medical training did not emphasize group facilitation skills, necessitating additional clinician training (Connor et al., 2017; McNeil et al., 2016).

Core Components of GWCC

The core components identified for GWCC were conceptualized as “characteristics of the intervention” as described in CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009). This section and Table 2 outline the key attributes of the intervention that influence its successful implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Table 2.

GWCC conceptual framework domain: core components of GWCC

| Domain and concepts | Description from the literature | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Core components of GWCC | ||

| Structure | Group size between 4 and 8 families | Anderson (2006), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Delago et al., (2018), Osborn (1989), Page et al., (2010, 2013), Rosenthal (2016), Rosenthal et al., (2014), Rushton et al., (2015) |

| Similar infant/child ages within groups (0–2 years old) | Gaskin et al., (2021) | |

| Frequency | Gaskin et al., (2021) | |

| Stable cohort | Delago et al., (2018), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), McNeil et al., (2016) | |

| Continuity of facilitators | (Gaskin et al., (2021) | |

| Duration 60–120 min | (Gaskin et al., (2021) | |

| Content (Parent/infant health assessments) |

Standard clinical services Individual health assessments (infant and parent) |

(Anderson (2006), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Friedman et al., (2021), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Marchel et al., (2015), McNeil et al., (2016), Osborn (1982) |

|

Standard practice screening tools Ages and stages parent questionnaire (ASQ) Parents evaluation of developmental status (PEDS) Modified checklist for autism in toddlers (MCHAT) Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) Parent health questionnaire -2, and -9 (PHQ-2, PHQ-9) Social needs screeners Additional research measures used Parenting stress index Social provision scale Sense of competence Safe environment for every kid parent screening questionnaire Karitane Parenting confidence scale (KPCS) Difficult life circumstances scale Orr stress test Parenting morale index Perceived stress scale Spielberger state-trait anxiety scale Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Social isolation subscales Social support questionnaire MOS social support survey Parent questionnaire knowledge based Upstart parent survey Family empowerment scale Stein’s functional status (FSIIR) Bayley’s Scale of infant development |

Bialostozky et al., (2016), Delago et al., (2018), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), Liebert (2016), Mittal (2011), Page et al., (2010), Platt et al., (2022), Rice and Slater (1997), Rushton et al., (2015), Stein et al., (2005), Taylor and Kemper (1998), Taylor et al., (1997a, 1997b) | |

| Process |

Interactive learning Facilitated discussion Anticipatory guidance Ancillary activities (e.g., cooking skills and infant massage) General topics covered Nutrition, sleep, child development, language development, behavior, safety, infant care, reproductive planning, healthy relationships, maternal self-care, mental health, and parenting skills |

Anderson (2006), Bialostozky et al., (2016), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Dodds et al., (1993), Friedman et al., (2021), Irigoyen et al., (2020), McNeil et al., (2016), Osborn (1982), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Taylor et al., (1997b) |

|

Community building Time for socializing Social support Service linkages for identified needs (e.g., mental health referrals; referrals for community resources, nutrition benefits,other social determinants of health) Incentives (e.g., developmental toys, food) |

Anderson (2006), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Friedman et al., (2021), McNeil et al., (2016), Mittal (2011), Osborn (1989) | |

Structure

The optimal range in cohort size to meet family needs, allow for effective facilitated group discussions, and meet productivity requirements remains unclear (Oldfield et al., 2020). Group structure concepts described in reviewed studies included group size, composition, stability, continuity of patients and facilitators, and frequency and length of visits (Table 2). One study described difficulties maintaining stable cohorts due to insufficient patient volumes (Jones et al., 2018). Most authors described following the Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics periodicity schedule for visit frequency (Dodds et al., 1993; Gaskin et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2018; Rice & Slater, 1997; Rosenthal et al., 2014, 2016). Two experts noted that CenteringParenting and other models follow the periodicity schedule with an additional two visits. The optimal number of GWCC sessions needed to impact outcomes is unclear, and the ability to sustain groups over time.

Content

Health Assessments

Screening Tools

Screening tools used to assess infant and family health are in Table 2. Several studies noted that GWCC facilitated more consistent screening for postpartum depression (PPD) and social needs (Friedman et al., 2021; Liebert, 2016; Platt et al., 2022). For research studies, additional measures were used to address specific research questions.

Standard Clinical Services/Service Linkages

Studies describing individual GWCC health assessments noted that weight, height, head circumference of infants, a physical exam, and standard screening tools were used (Friedman et al., 2021; Marchel et al., 2015). Some GWCC models included self-assessments for parents and parental assistance as part of infant assessments (e.g., height, weight) (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; McNeil et al., 2016). Several studies noted that individual assessment time was also used to provide referrals and follow-up with families if needed. One study reported that PPD evaluation and referrals were more successful in group compared to individual care (Liebert, 2016). Conversely, other studies in pediatric settings described the integration of maternal physical health assessments into GWCC as challenging (e.g., maternal weight, and blood pressure) (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Jones et al., 2018).

Process

Interactive Learning within Group Discussion

Facilitative learning was described in all GWCC models, in contrast to the didactic approach typically used at individual visits (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013). The increased time in the group visit for discussion about health and social concerns was described as beneficial (Anderson, 2006; Connor et al., 2017; Friedman et al., 2021; Marchel et al., 2015; L. Osborn, 1982; L. Osborn & Woolley, 1981; Taylor et al., 1997b). One study reported that participants had increased odds of receiving more recommended anticipatory guidance than in individual care (Connor et al., 2017; Friedman et al., 2021; Marchel et al., 2015; Rushton et al., 2015) Group discussions about sensitive topics (e.g., PPD, partner relationships, and social needs) were described as generally well-received (Platt et al., 2022). One study described peer education and knowledge-sharing during GWCC as influencing health service utilization (Oldfield et al., 2019).

Community-Building

GWCC was described as fostering partnerships between families, clinicians, and communities (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Mittal, 2011). Studies described the support and reassurance patients received from fellow group members and clinicians (Anderson, 2006; Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Osborn, 1989) Studies focusing on specific patient populations described the benefit of receipt of group support and education to address cultural and community needs (Bialostozky et al., 2016; Friedman et al., 2021; Oldfield et al., 2019).

Outcomes

We organized clinical outcomes reported in the articles according to the quadruple aim of health care (see Table 3) (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014; Sikka et al., 2015).

Table 3.

GWCC conceptual framework domain: outcomes

| Domain and concepts | Description from the literature | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||

| Clinical outcomes |

Infant Immunizations Nutrition/breastfeeding Chronic disease (e.g., obesity) Illness/ED visits Child development |

Bialostozky et al., (2016), Delago et al., (2018), Fenick et al., (2020), Friedman et al., (2021), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Johnston et al., (2017), Machuca et al., (2016), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Page et al., (2010), Rice and Slater (1997), Rushton et al., (2015), Shah et al., (2016), Taylor et al., (1997b) |

|

Parent/caregiver Psychosocial well-being Childbearing parent physical health Family planning Parenting self-efficacy/change in parenting skills and/or attitudes Retention of anticipatory guidance Safety |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Connor et al., (2017), Delago et al., (2018), Desai et al., (2019), Fenick et al., (2020), Friedman et al., (2021), Graber et al., (2019), Johnston et al., (2017), Jones et al., (2018), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), Osborn and Woolley (1981), Platt et al., (2022), Rice and Slater (1997), Rosenthal (2016), Rushton et al., (2015), Thomas et al., (1984) | |

|

Population health Social determinants of health/attention to social needs Mitigating exposure to toxic stress/childhood adversity Family and community health Health equity |

Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Delago et al., (2018), Desai et al., (2019), Fenick et al., (2020), Graber et al., (2019), Gullett et al., (2019), Machuca et al., (2016), Oldfield et al., (2019), Platt et al., (2022), Rosenthal et al., (2016), Taylor et al., (1997b) | |

| Patient experience | Patient satisfaction/patient trust in medical systems | Anderson (2006), Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Connor et al., (2017), Delago et al., (2018), Gullett et al., (2019), Jones et al., (2018), Marchel et al., (2015), Saysana and Downs (2012) |

| Social support/social cohesion/support networks | Bloomfield and Rising (2013), Castellan et al., (2020), Connor et al., (2017), Friedman et al., (2021), Johnston et al., (2017, Jones et al., (2018), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Marchel et al., (2015), Oldfield et al., (2019), Page et al., (2010), Stein (1977) | |

| Attendance | Fenick et al., (2020), Gullett et al., (2019), Irigoyen et al., (2020), Rushton et al., (2015) | |

| Face to face time with the clinic team | Friedman et al., (2021) | |

| Clinician experience | Job satisfaction | Desai et al., (2019), Friedman et al., (2021) |

| Efficacy | Desai et al., (2019), Friedman et al., (2021), MacMillan Uribe et al., (2019), Mittal (2011), Page et al., (2010, 2013), Rosenthal et al., (2014, 2016), Saysana and Downs (2012) | |

| Communication | Rosenthal et al., (2014, 2016) | |

| Health system costs | Cost neutral | Yoshida et al., (2014) |

| Cost effective | Anderson (2006), Yoshida et al., (2014) | |

Clinical Outcomes

Infant

Outcomes measured related to the infant included: vaccination rates, nutrition-related behaviors (e.g., rates of breastfeeding amongst participants), infant/child weight, emergency department visits, and child development. As described in a recent systematic review, studies suggest improvements in several healthcare utilization domains, including vaccination rates and ED utilization (Gaskin et al., 2021).

Parent/Caregiver

Parent/caregiver outcomes included: psychosocial well-being (e.g., PPD, intimate partner violence (IPV), stress/anxiety), physical health, family planning, parenting self-efficacy/change in parenting skills and/or attitudes, receipt and retention of anticipatory guidance, and safety measures in the home. Most studies examining psychosocial well-being were qualitative, parents described GWCC as an opportunity for stress relief (Platt et al., 2022), a safe space to create peer connections that empower them to recognize toxic stress and address it (Graber et al., 2019), and provide grief support (M. Rosenthal, 2016). Clinicians and caregivers reported several physical health needs of the parent that were potentially addressed in GWCC, including breastfeeding support, diabetes and hypertension screening, weight management, screening for family violence, support for the management of substance use, and family planning (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; Platt et al., 2022). Although one study found that pediatricians expressed concerns that they are not adequately trained to address maternal health needs (Connor et al., 2017), parents considered the inclusion of maternal wellness as beneficial (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Connor et al., 2017; McNeil et al., 2016).

Population Health

Several studies described the potential population health benefits of GWCC, including increased preventive health care (Fenick et al., 2020), improved identification of social needs (DeLago et al., 2018; Desai et al., 2019; Gullett et al., 2019; Platt et al., 2022) and the ability to incorporate strategies to address child poverty (DeLago et al., 2018; Fierman et al., 2016), and trauma-informed care to enhance participant resilience (Graber et al., 2019). Population-specific discussion topics included immigration stressors and fears (Oldfield et al., 2019; Platt et al., 2022). GWCC was also described by facilitators as advancing health equity through increasing and improving clinicians’ skills in family engagement (Rosenthal et al., 2016). Additionally, patient involvement in GWCC was described as more effectively highlighting participants’ health education needs (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013).

Patient Experience

Studies described high patient satisfaction with GWCC (Anderson, 2006; Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Connor et al., 2017; DeLago et al., 2018; Gullett et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2018; Marchel et al., 2015; Saysana & Downs, 2012). The most frequently expressed themes among participants in GWCC included the value of support, reassurance and learning from other parents (Bloomfield & Rising, 2013; Castellan et al., 2020; Connor et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2018; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; Marchel et al., 2015; McNeil et al., 2016; Oldfield et al., 2019; Page et al., 2010; Stein, 1977). Some studies described increases in social support in group care as compared to individual care (Friedman et al., 2021; Johnston et al., 2017). Others reported increased well-child visit attendance at GWCC as compared to individual care (Fenick et al., 2020; Gullett et al., 2019; Irigoyen et al., 2020; Rushton et al., 2015).

Clinician Experience

Clinician-reported benefits of GWCC included high clinic team satisfaction and increased perceived effectiveness and quality of care in group versus individual visits (Desai et al., 2019; Friedman et al., 2021; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; McNeil et al., 2016; Mittal, 2011), reduced burnout (Gullett et al., 2019; Stein et al., 2005), and increased empathy (M. S. Rosenthal et al., 2016). Training benefits of GWCC included being able to simultaneously master skills in family engagement and provide well-child care (Page et al., 2010, 2013; Rosenthal et al., 2014, 2016), improved trainee education (Saysana & Downs, 2012), and improvement in trainees’ abilities to provide culturally competent care, conduct developmental assessments, address common parent concerns, and bond with families (Mittal, 2011).

Health System Costs and Savings

Few studies included costs as an outcome or focused on costs. An economic evaluation found cost neutrality was achieved “at 4 families in the APRN [advanced practice registered nurse] group WCV [well-child care] model; at 3, 4, 5, and 6 families in the resident model with 30, 45, 60, and 90 min of attending supervision, respectively; and at 4 and 5 families in the low and high attending salary model” (Yoshida et al., 2014). One study projected that targeted interventions such as GWCC yielding a 1% reduction in obesity prevalence among children could achieve USD1.7 billion in lifetime savings, based on calculated lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity (Machuca et al., 2016).

Discussion

The current system of well-child care is inadequate to meet families’ needs, resulting in the need for system redesign to address barriers to high quality, family-centered care and to improve outcomes (Coker et al., 2013; Freeman et al., 2018; MacMillan Uribe et al., 2019; Schor, 2004). In synthesizing the data available for GWCC for the conceptual framework, we found that GWCC provides a viable alternative model of well-child care that aligns with the quadruple aim in impacting not only patient outcomes, but also patient/family and clinic team’s experiences, population health, and potentially health system costs. An engaged and productive healthcare workforce is key to an effective healthcare system (Sikka et al., 2015), and available research suggests high satisfaction among clinic care teams implementing GWCC. This framework can be used as a tool for practitioners to implement GWCC as it describes the necessary inputs and core components of GWCC, which may be particularly beneficial to underserved populations (Gaskin et al., 2021).

Our conceptual framework allows us to graphically depict key GWCC domains and concepts crucial to model implementation and sustainability across a range of settings (Miles et al., 2019). Incorporation of implementation science methodologies have been recommended to advance future research on GWCC in order to bridge the gap between evidence and practice of GWCC (Oldfield et al., 2020). Conceptual frameworks provide guidance for policy, practice, and evaluation and are particularly important for identifying relevant factors influencing implementation processes (Wittmeier et al., 2015). Incorporating constructs in alignment with the CFIR and the quadruple aim in the conceptual framework provides the necessary foundation to examine GWCC model fidelity and future evaluations of the efficacy of GWCC across settings (Damschroder et al., 2009; Wittmeier et al., 2015). Given the identified impacts on outcomes, it is important that researchers not only fully describe the elements of the GWCC model implemented, but also harmonize assessments. Harmonization would allow for better comparisons of effectiveness across settings, models, and among various patient populations. For example, although some studies use screening tools typically found in the electronic health records (e.g., the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for PPD), there is little uniformity across other study measures.

While the conceptual framework depicts the key domains and concepts for successful implementation of GWCC based on the existing literature and expert consultation, it has the flexibility for adaptation to specific contexts in which GWCC is implemented. Several studies adapted or enhanced GWCC session curricula for a particular population or setting to provide content and/or resources to fit the context in which GWCC was being delivered. This showcases an opportunity to use GWCC as a strategy to redesign well-child care to meet the needs of families, their physical, mental, and social determinants of health and reach marginalized populations. Studies show that low-income parents endorse group visits as an empowering opportunity to learn from other parents and build support networks (Coker et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2018). The results from the enhanced trauma-informed GWCC also highlight GWCC’s potential to serve as a clinical strategy to address health disparities and improve health equity (Graber et al., 2019). Studies implementing GWCC among immigrant populations described the ability to identify concerns related to socio-political and economic concerns and link families to community resources to address them, and culturally adapt the model both in content and linguistically to make it accessible to diverse populations. Several studies reported increased vaccine uptake among GWCC participants; this is particularly relevant to highlight in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic with high rates of vaccine hesitancy (Callaghan et al., 2021; Troiano & Nardi, 2021).

The conceptual framework depicts key elements to successfully implement GWCC. However, it is important to note that implementation barriers, including inadequate space and the need for dedicated and skilled facilitators, were also described across studies. Despite findings that the model can be cost neutral, some studies described financial concerns with startup costs and billing for visits (Connor et al., 2017; McNeil et al., 2016). Others described low patient volumes which made it difficult to sustain GWCC. Expert consultation highlighted the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on group visits and challenges to maintaining in-person visits. In some practices group visits have pivoted to telehealth platforms. Across health care disciplines telehealth has undergone a rapid transformation and research may elucidate how to effectively incorporate this modality (Curfman et al., 2021). Additional barriers to accessing telehealth add further complexities to providing equitable well-child care. These issues highlight areas for consideration and improvement in the implementation of GWCC for it to be maximally successful and widely implemented.

Our review has several limitations. While multiple articles described the same site and model, many articles did not fully describe the specific elements of the model of GWCC in use at their practices. There are more sites implementing the model than those conducting studies which highlights the evidence-to-practice gap around GWCC (Centering Healthcare Institute, 2021) and suggests that there is additional information to be learned from practicing sites. While the framework was constructed based on literature from the US and Canada, it can be adapted for use in international settings. Finally, searching primarily academic databases may not have captured all relevant gray literature. However, taken as a body of literature, the included studies provided the necessary data to construct the conceptual framework. Moreover, our inclusion of expert consultation including GWCC clinicians served to mitigate these limitations through incorporation of their valuable, practice-based knowledge and insights in the process.

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research

We suggest convening a working group to identify standard tools for outcome measurement to be able to compare effectiveness across sites. Research designs such as adaptive and pragmatic trials and implementation/effectiveness trials are recommended to understand the benefits of GWCC in specific contexts and populations (Oldfield et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2020).

A major gap in the available research is the lack of cost and savings data. Given rising healthcare costs, policymakers and health systems need evidence showing that in the short-term there is no major increase in costs or resources when GWCC is offered and in the long-term, there is an accumulative cost savings as infants, children, and their families are healthier (Machuca et al., 2016). Growing an evidence-base can lead to policy changes and increased model uptake; as seen with group prenatal care, with its larger evidence-base, 10 states now support its implementation financially through enhanced reimbursements for group care providers (Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center, 2020).

Conclusion

GWCC is a model of care that offers an opportunity to meet the quadruple aim of healthcare and provide the necessary system redesign to meet families’ needs. Future research and practice can use the conceptual framework as a tool to standardize model implementation and evaluation and generate more evidence to inform future healthcare policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the following experts’ contributions to the conceptual framework: Adriana Bialostozky, MD; Mireille Boutry, MD; Camille Brown, MD; Patricia Faraone Nogelo, LCSW; Suzanne Friedman, MD; Flor Giusti, LCSW-C; Andrea Green, MD; Kathi Kemper, MD, MPH; Caitlin Leary, Certified Child Life Specialist; Susan Leib, MD MPH; Dodi Meyer, MD; Lucy Osborn, MD; Julia Rosenberg, MD, MHS; Marty Stein, MD.

Appendix 1

List of search terms

Ovid MEDLINE

| No. | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | ((group adj "well-child") or (group adj "well child")).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 2 | ("centering parenting" or "centeringparenting").mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 3 | 1 or 2 |

Embase

| No. | Query |

|---|---|

| 1 | ((group NEAR/2 ('well child' OR 'well-child')):ti,ab,kw) OR 'centeringparenting':ti,ab,kw OR 'centering parenting':ti,ab,kw |

CINAHL

| No. | Query | Limiters/Expanders | Last run via |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | (group N2 ("well child" OR "well-child")) OR ("centering parenting" OR "centeringparenting") |

Expanders—Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase |

Interface—EBSCOhost research databases Search screen—Advanced search Database—CINAHL plus with full text |

Web of Science

TOPIC: ((group NEAR/2 ("well child" OR "well-child")) OR "centeringparenting" OR "centering parenting").

Timespan: All years. Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC.

Scopus

(TITLE-ABS-KEY ((group W/2 "well child") OR (group W/2 "well-child")) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ("centering parenting" OR "centeringparenting")).

APAPsycInfo

| # | Query | Limiters/Expanders | Last run via |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (group N2 ("well child" OR "well-child")) OR ("centering parenting" OR "centeringparenting") |

Expanders—Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase |

Interface—EBSCOhost research databases Search screen—Advanced search Database—APA PsycInfo |

Author Contributions

This article was conceptualized by AG and DW and designed by AG, DW, AF, SR, CP, TC, and RP. AG conducted the literature search. AG, DW, and RP reviewed the abstracts and read final full text articles for inclusion/exclusion. AG crafted the original draft preparation. AG, DW, CP, AF, TC, SR, NG, and RP reviewed and edited subsequent versions.

Funding

Ashley Gresh was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31NR019205. Rheanna Platt was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Award K23MH118431. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- ACOG Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG committee opinion No. 736. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;131:e140–150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. Rejuvenate your practice with group visits. Contemporary Pediatrics. 2006;23(5):80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialostozky A, McFadden SE, Barkin S. A novel approach to well-child visits for latino children under two years of age. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2016;27(4):1647–1655. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield J, Rising SS. CenteringParenting: an innovative dyad model for group mother-infant care. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013;58(6):683–689. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, Hotez P, Strych U, Dor A, Fowler EF, Motta M. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Social Science and Medicine. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellan CM, Casola AR, Weinstein LC. Centering providers to deliver group care: implementing CenteringPregnancy and CenteringParenting at an Urban federally qualified health center. Population Health Management. 2020 doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centering Healthcare Institute. (2021). CenteringParenting.

- Coker TR, Chung PJ, Cowgill BO, Chen L, Rodriguez MA. Low-income parents’ views on the redesign of well-child care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):194–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Windon A, Moreno C, Schuster MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for young children: A systematic review of strategies and tools. Pediatrics. 2013;131:S5–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1427c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, Kastner M, Moher D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KA, Duran G, Faiz-Nassar M, Mmari K, Minkovitz CS. Feasibility of implementing group well baby/well Woman Dyad care at federally qualified health centers. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;18(5):510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curfman A, McSwain SD, Chuo J, Yeager-McSwain B, Schinasi DA, Marcin J, Herendeen N, Chung SL, Rheuban K, Olson CA. Pediatric telehealth in the COVID-19 pandemic era and beyond. Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-047795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearholt S, Dang D. Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: model and guidelines. Sigma Theta Tau International; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLago C, Dickens B, Phipps E, Paoletti A, Kazmierczak M, Irigoyen M. Qualitative evaluation of individual and group well-child care. Academic Pediatrics. 2018;18(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Chen F, Boynton-Jarrett R. Clinician satisfaction and self-efficacy with CenteringParenting group well-child care model: a pilot study. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2150132719876739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds M, Nicholson L, Muse B, III, Osborn L. Group health supervision visits more effective than individual visits in delivering health care information. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):668–670. doi: 10.1542/peds.91.3.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JO, Shenassa E. Understanding and meeting the needs of women in the postpartum period: The perinatal maternal health promotion model. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2013;58(6):613–621. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenick AM, Leventhal JM, Gilliam W, Rosenthal MS. A randomized controlled trial of group well-child care: Improved attendance and vaccination timeliness. Clinical Pediatrics. 2020;59(7):686–691. doi: 10.1177/0009922820908582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierman AH, Beck AF, Chung EK, Tschudy MM, Coker TR, Mistry KB, Siegel B, Chamberlain LJ, Conroy K, Federico SG, Flanagan PJ, Garg A, Gitterman BA, Grace AM, Gross RS, Hole MK, Klass P, Kraft C, Kuo A, Cox J. Redesigning health care practices to address childhood poverty. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(3S):S136–S146. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman XK, Md XX, Coker XR. Six questions for well-child care redesign. Pediatric Association. 2018;18(6):609. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Calderon B, Gonzalez A, Suruki C, Blanchard A, Cahill E, Kester K, Muna M, Elbel E, Purushothaman P, Krause MC, Meyer D. Pediatric practice redesign with group well child care visits: A multi-site study. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2021;25(8):1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03146-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin E, Yorga KW, Berman R, Allison M, Sheeder J. Pediatric group care: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2021;25(10):1526–1553. doi: 10.1007/s10995-021-03170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber LK, Roder-Dewan S, Brockington M, Tabb T, Boynton-Jarrett R. Parent perspectives on the use of group well-child care to address toxic stress in early childhood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma. 2019;28(5):581–600. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1539423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gullett H, Salib M, Rose J, Stange KC. An Evaluation of centeringparenting: A group well-child care model in an Urban federally qualified community health center. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2019;25(7):727–732. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irigoyen MM, Leib SM, Paoletti AM, Delago CW. Timeliness of immunizations in CenteringParenting. Academic Pediatrics. 2020;000:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JC, McNeil D, van der Lee G, MacLeod C, Uyanwune Y, Hill K. Piloting CenteringParenting in two alberta public health well-child clinics. Public Health Nursing. 2017;34(3):229–237. doi: 10.1111/phn.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Do S, Porras-Javier L, Contreras S, Chung PJ, Coker TR. Feasibility and acceptability in a community-partnered implementation of CenteringParenting for group well-child care. Academic Pediatrics. 2018;18(6):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar J, Boned-Rico L, Olander EK, McCourt C. A systematic review of providers’ experiences of facilitating group antenatal care. Reproductive Health. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebert H. Postpartum depression: screening and treatment of low-income women in a primary care setting. The Wright Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liljenquist K, Coker TR. Transforming well-child care to meet the needs of families at the intersection of Racism and poverty. Academic Pediatrics. 2021;21(8):S102–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca H, Arevalo S, Hackley B, Applebaum J, Mishkin A, Heo M, Shapiro A. Well baby group care: Evaluation of a promising intervention for primary obesity prevention in toddlers. Childhood Obesity. 2016;12(3):171–178. doi: 10.1089/chi.2015.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan Uribe AL, Woelky KR, Olson BH. Exploring family-medicine providers’ perspectives on group care visits for maternal and infant nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2019;51(4):409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchel MA, Winesett H, Hall K, Luke S, Duluth P, Ladd MC. Holding the holders: An interdisciplinary group well-child model. Zero to Three Journal. 2015;2015:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil D, Johnston J, van der Lee G, Wallace N. Implementing CenteringParenting in well child clinics: mothers’ nurses’ and decision makers’ perspectives. Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing. 2016 doi: 10.4172/2471-9846.1000134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. SAGE Publications; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal P. Centering parenting: pilot implementation of a group model for teaching family medicine residents well-child care. The Permanente Journal/fall. 2011;15(4):40. doi: 10.7812/tpp/11-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G, Womack JA, Sadler LS. Beyond implementation: Sustaining group prenatal care and group well-child care. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2020;65(4):512–519. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Nogelo PF, Vázquez M, Ona Ayala K, Fenick AM, Rosenthal MS. Group well-child care and health services utilization: A bilingual qualitative analysis of parents’ perspectives. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2019;23(11):1482–1488. doi: 10.1007/s10995-019-02798-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Rosenthal MS, Coker TR. Update on the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of group well-child care. Academic Pediatrics. 2020;20(6):731–732. doi: 10.1177/0009922820908582.T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn L. Group well-child care: An option for today’s children. Pediatric Nursing. 1982;8(5):306–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn LM. Group well-child care offers unique opportunities for patient education. Patient Education and Counseling. 1989;14:227. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(89)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn L, Woolley F. Use of groups in well child care. Pediatrics. 1981;67(5):701. doi: 10.1542/peds.67.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page C, Reid A, Andrews L, Steiner J. Evaluation of prenatal and pediatric group visits in a residency training program. Family Medicine. 2013;45(5):349–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page C, Reid A, Hoagland E, Brier Leonard S. WellBabies: Mothers’ perspectives on an innovative model of group well-child care. Family Medicine. 2010;42(3):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt RE, Acosta J, Stellmann J, Sloand E, Caballero TM, Polk S, Wissow LS, Mendelson T, Kennedy CE. Addressing psychosocial topics in group well-child care: A multi-method study with immigrant Latino families. Academic Pediatrics. 2022;22(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. (2020). Group prenatal care.

- Rice RL, Slater CJ. An analysis of group versus individual child health supervision. Clinical Pediatrics. 1997;36:685–690. doi: 10.1177/000992289703601203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, M. (2016). Coding grief. Contemporary pediatrics . https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/view/coding-grief

- Rosenthal MS, Connor KA, Fenick AM. Pediatric residents’ perspectives on relationships with other professionals during well child care. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2014;28(5):481–484. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.909796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MS, Connor KA, Fenick AM. Pediatric residents’ perspective on family-clinician discordance in primary care: A qualitative study. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2016;27(3):1033–1045. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton FE, Byrne WW, Darden PM, McLeigh J. Enhancing child safety and well-being through pediatric group well-child care and home visitation: the well baby plus program. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2015;41:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saysana M, Downs SM. Piloting group well child visits in pediatric resident continuity clinic. Clinical Pediatrics. 2012;51(2):134–139. doi: 10.1177/0009922811417289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor EL. Rethinking well-child care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):210–216. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NB, Fenick AM, Rosenthal MS. A healthy weight for toddlers? Two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of group well-child care. Clinical Pediatrics. 2016;55(14):1354–1357. doi: 10.1177/0009922815623230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The quadruple aim: Care, health, cost and meaning in work. In BMJ Quality and Safety. 2015;24(10):608–610. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Platt R, Hernandez A. Evidence from pragmatic trials during routine—slouching toward a learning health system. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(16):1488–1491. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1915762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MT. The providing of well-baby care within parent-infant groups. Clinical Pediatrics. 1977;17(9):825–828. doi: 10.1177/000992287701600917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MT, Plonsky C, Zuckerman B, Carey WB. Reformatting the 9-month health supervision visit to enhance developmental, behavioral and family concerns. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005;26:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Davis RL, Kemper KJ. A randomized controlled trial of group versus individual well child care for high-risk children: maternal-child interaction and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics. 1997;99:e9. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Davis RL, Kemper KJ. Health care utilization and health status in high-risk children randomized to receive group or individual well child care. Pediatrics. 1997;100:e1. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.3.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Kemper KJ. Group well-child care for high-risk families maternal outcomes. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1998 doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.6.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KA, Hassanein RS, Christophersen ER. Evaluation of group well-child care for improving burn prevention practices in the home. Pediatrics. 1984;74:879–882. doi: 10.1542/peds.74.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. 2021;194:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2021). Covidence systematic review software. www.covidence.org.

- Wittmeier KDM, Klassen TP, Sibley KM. Implementation science in pediatric health care advances and opportunities. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(4):307–309. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Fenick AM, Rosenthal MS. Group well-child care: An analysis of cost. Clinical Pediatrics. 2014;53(4):387–394. doi: 10.1177/0009922813512418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.