Abstract

Many cancers hijack translation to increase synthesis of tumor-driving proteins whose messenger RNAs (mRNAs) have specific codon usage patterns. Termed codon-biased translation and originally identified in stress response regulation, this mechanism is supported by diverse studies demonstrating how the 50 RNA modifications of the epitranscriptome, specific transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and codons-biased mRNAs are used by oncogenic programs to promote proliferation and chemoresistance. Epitranscriptome writers METTL1-WDR4, ELP1-6, CTU1-2 and ALKBH8-TRM112 illustrate the principal mechanism of codon-biased translation, with gene amplifications, increased RNA modifications, and enhanced tRNA stability promoting cancer proliferation. Further, systems-level analyses of 34 tRNA writers and 493 tRNA genes highlight the theme of tRNA epitranscriptome dysregulation in many cancers and identify candidate tRNA writers, tRNA modifications, and tRNA molecules as drivers of pathological codon-biased translation.

Keywords: epitranscriptome, translational regulation, gene expression, cancer, tRNA modifications, codon, systems biology

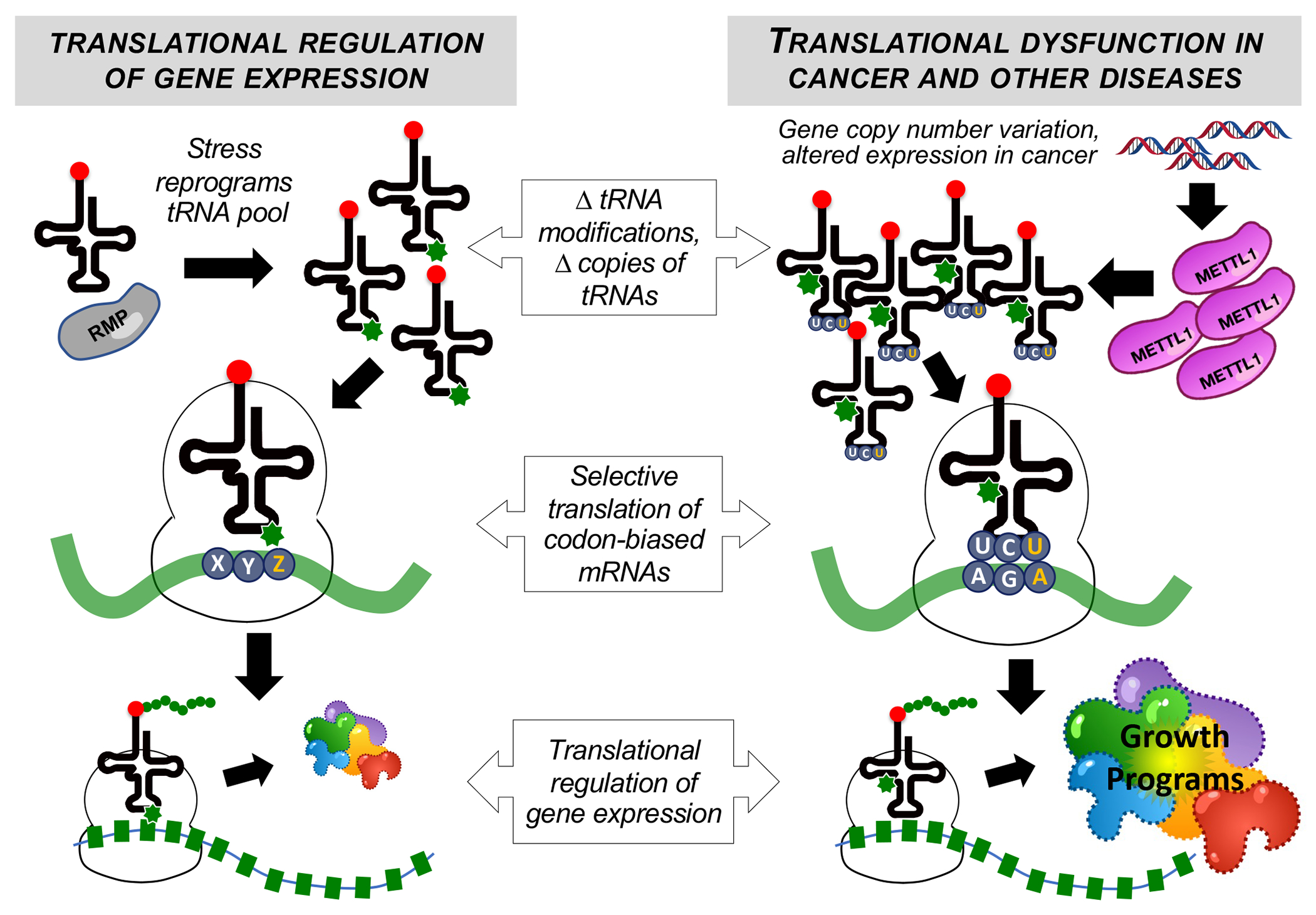

A fundamental mechanism regulating translation

Of the major systems regulating gene expression at the level of translation, there is evidence for coordination among three in all forms of life: the tRNA ribonucleome of ~250 expressed tRNAs (from ~500 tRNA genes), the >50 modified ribonucleosides that make up the tRNA epitranscriptome, and alternative genetic information in the form of biased use of synonymous codons in different gene families [4, 11–15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 27–39]. A scheme for the coordination among these three systems is illustrated in Fig. 1. The general idea is that, in conjunction with activation of transcriptional and signaling pathways, cells respond to environmental demands by reprogramming the number of copies of individual tRNAs and the levels of 4 to on average 13 modified ribonucleosides in each tRNA to enhance translation of families of stress response mRNAs possessing biased use of codons matching the reprogrammed tRNAs [11–21]. Here we use cancer to illustrate how corruption of each of these systems leads to aberrant translation that drives pathology and disease.

Fig. 1. tRNA as a driver of translational dysfunction in human disease.

After initiation, translational control of gene expression can be guided by tRNAs, modifications, and writers that promote the synthesis of mRNAs with specific codon biases, with normal function of this system regulating stress responses, cell cycle, and growth programs (left). In the pathophysiology of cancer and other diseases, this system can be corrupted to alter translational regulation of gene expression, with some cancers using writers, modifications, and tRNAs to increase the translation of mRNAs with specific codon biases to promote growth programs, such as changes in oncogenic pathways, cell cycle and metabolism (right). RMP: RNA-modifying protein; METTL1: methyltransferase 1, tRNA methylguanosine.

tRNA expression as a cancer driver.

Though only half are expressed, the human genome has ~500 tRNA genes comprising 51 anticodon families, or isoacceptors (same amino acid), to read 61 of 64 codons for 20 amino acids [40–42]. While wobbling allows 51 anticodons to read 61 codons, humans have multiple sequence-similar versions of each isoacceptor – isodecoders – with differential expression in tissues to fine-tune translation [42–44]. It has been shown that, in coordination with the tRNA epitranscriptome (Fig. 2), the abundance of specific tRNAs enhances the translation of mRNAs enriched with the cognate codons of the tRNAs [11, 12, 15, 17–19, 21, 30, 31, 45]. These observations extend to cancer [23, 24, 38, 46]. Using a hybridization method to quantify tRNA levels in normal and breast cancer cells, it was shown that overexpression of specific tRNA isoacceptors correlated with increased levels of oncoproteins from genes enriched with cognate codons of the tRNAs [23]. Other studies have revealed that codon-biases and matching tRNA overexpression distinguish proliferating from differentiating cells [24]. Consistent with the model for tRNA epitranscriptome-driven codon-biased translation, highly expressed tRNAs are frequently associated with overexpression of their tRNA-modifying enzymes in cancer. For example, insertion of m7G at position 46 into several tRNAs by over-expressed METTL1, including the isodecoder tRNA-Arg-TCT-4-1 (see “tRNA” in Glossary for tRNA nomenclature), stabilizes the tRNAs against loss or degradation, with the increased levels of tRNA-Arg-TCT driving translation of growth-promoting mRNAs enriched with the 5’-AGA-3’ cognate codon [25–27] (Fig. 1). The tRNA in Cancer database (tRic) corroborates this model, with abnormally high levels of tRNA-Arg-TCT in tumors such as gliomas [26] (vide infra). Similarly, over-expression of ELP3 is thought to increase the levels of tRNAs containing ELP3-catalyzed wobble uridine (U) modifications (Fig. 2), which drives translation of mRNAs enriched in their cognate codons, including tumor-driving proteins such as cell cycle regulators [22].

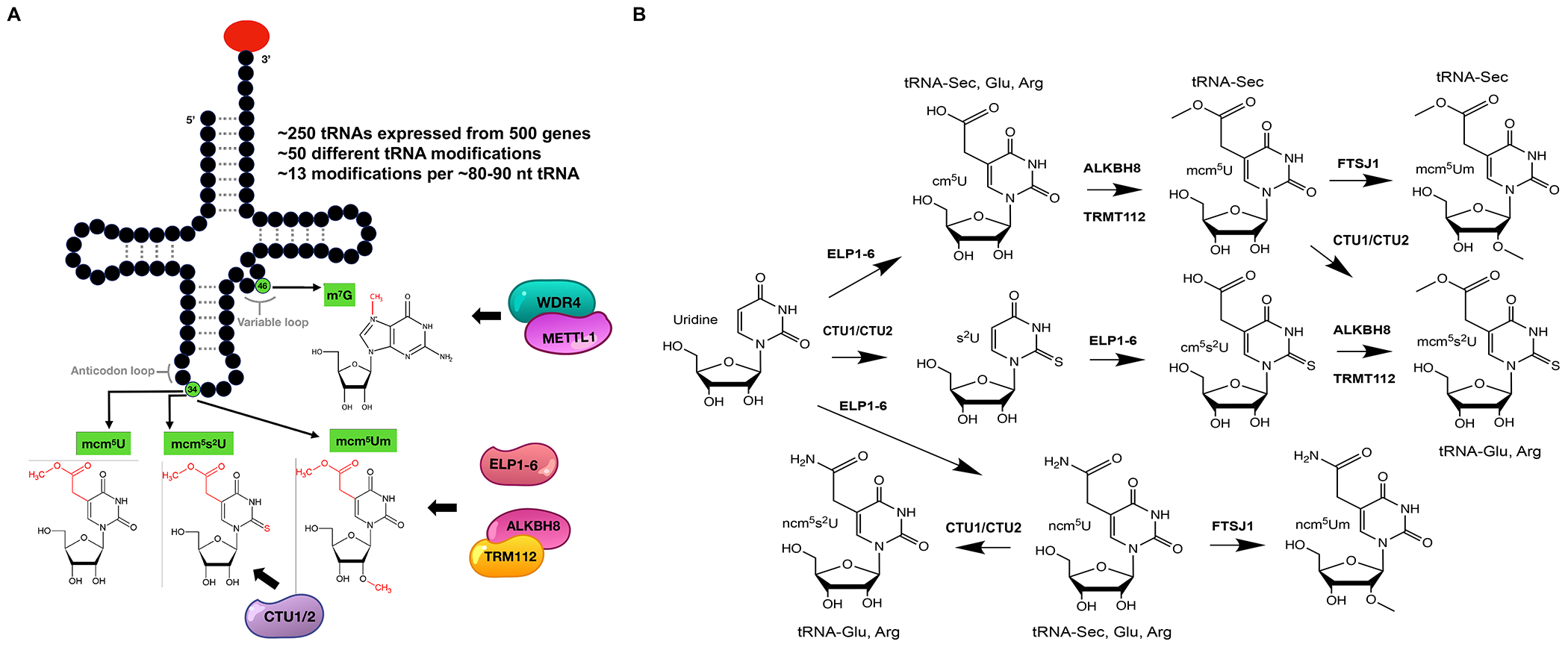

Fig. 2. tRNA modifications and writers linked to cancer.

(A) A canonical tRNA structure showing the locations of specific tRNA modifications and their writers shown to be drivers of cancer proliferation. (B) Complex biochemical pathways for the synthesis of wobble uridine modifications by ALKBH8-TRM112, ELP1-6, CTU1/2 and FTSJ1 writers, illustrating the many potential points for corruption of tRNA reprogramming and codon-biased translation in cancer and the many possible targets for therapeutic intervention.

The tRNA epitranscriptome in cancer.

A second contribution to translation addiction of cancer [9] arises from >50 modified ribonucleosides inserted post-transcriptionally into every form of RNA in humans – the epitranscriptome [47, 48]. From among >170 RNA modifications in all organisms [1, 49], humans possess ~50 [50], with ~13 modifications in each of >250 different ~80-nt tRNA molecules [51]. For example, methylation is the most abundant RNA modification, with >25 tRNA methyltransferases (TRMs/METTLs) in mice and humans [1, 52]. In general, TRMs/METTLs transfer the methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to tRNA nucleobases or the ribose 2′-OH, such as METTL1-WDR4 catalyzing the formation of m7G (Fig. 2). At the other extreme of complexity, many RNA modifications involve multiple enzymatic steps and are termed “hyper-modified”, such as the mcm5Um and mcm5s2U modifications catalyzed by a complex of ELP1-6, CTU1/2, ALKBH8-TRM112 and FTSJ1 (Fig. 2). Like several other tRNA-modifying enzymes, the catalytic activity of METTL1 and ALKBH8 require the noncatalytic binding partners WDR4 and TRM112, respectively, to form a catalytically-competent complex [53, 54].

Depending upon location, modifications regulate tRNA stability, prevent frame shifting, and modulate translation efficiency [27, 55–57]. For example, the presence of m7G at position 46 of a subset of tRNAs stabilizes them against loss or degradation [25–27]. Significantly, the tRNA wobble position is important for optimizing anticodon-codon interactions during translation and it is the most frequently and variably modified position in tRNA [58–60]. This points to a significant potential for regulating translation [55, 61] and, as a result, a significant source of disease-driving dysregulation. With implications for disease causation, the 50 tRNA modifications coordinate as a system to regulate gene expression at the level of translation [4, 11–15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 27–39]. Yeast, rat, and human cells respond to stress by altering the levels of a subset of modifications at different positions in tRNA, especially the anticodon wobble position 34 (Fig. 2). This modification reprogramming is unique to each stress [11, 12, 15, 17–19, 21, 30, 31, 45], with >80% sensitivity and specificity for predicting the stress in yeast [15]. The altered modifications can lead to changes in tRNA levels by increasing or decreasing tRNA stability and to enhanced reading of their cognate codons, with the net result of enhanced translation of mRNAs enriched with these codons. As discussed shortly, families of stress response [11–13, 15, 17, 18, 28, 30–32, 36] and cell proliferation genes [23, 24, 46] are distinguished by biased use of synonymous codons as alternative genetic information that is coordinated with tRNA copy number and modifications to regulate translation.

Emerging evidence points to this reprogramming of the tRNA epitranscriptome as a major driver of cancer. As noted earlier, the ELP3/CTU1/2 complex that catalyzes U34 modifications (Fig. 2) can drive melanomas that express mutated BRAFV600E, with subsequent resistance to anti-BRAF therapy caused by codon-biased translation of metabolic proteins [22]. This epitranscriptome-driven cell proliferation generalizes to breast and WNT-based colon cancer driven by increased ELP3 [4, 22, 38]. Similarly, humans possess 2 homologs of mcm5U34-inserting yeast Trm9: TRM9L and ALKBH8 [17, 28, 34, 35, 62]. Epigenetically silenced in many cancers, TRM9L (also called TRMT9B) is a catalytically inactive negative regulator of tumor growth that functions as a phospho-signaling node in the oxidative stress-activated MEK-ERK-RSK cascade [35]. ALKBH8, on the other hand, catalyzes both methylation to form mcm5U34 and oxidation to mchm5U in tRNA (Fig. 2), with wobble modification of the tRNA for selenocysteine driving translation of oxidative stress tolerance selenoproteins [17, 28, 34, 62, 63] (Fig. 2). While loss of ALKBH8 is associated with severe intellectual disability, senescence, and sensitivity to toxicants [20, 64, 65], over-expression plays a causative role in bladder cancer [66] possibly by increasing expression of selenoproteins protecting against tumorigenic stresses [17, 28, 62]. The over-expression of other RNA modifying proteins (RMPs) in many cancers is discussed shortly.

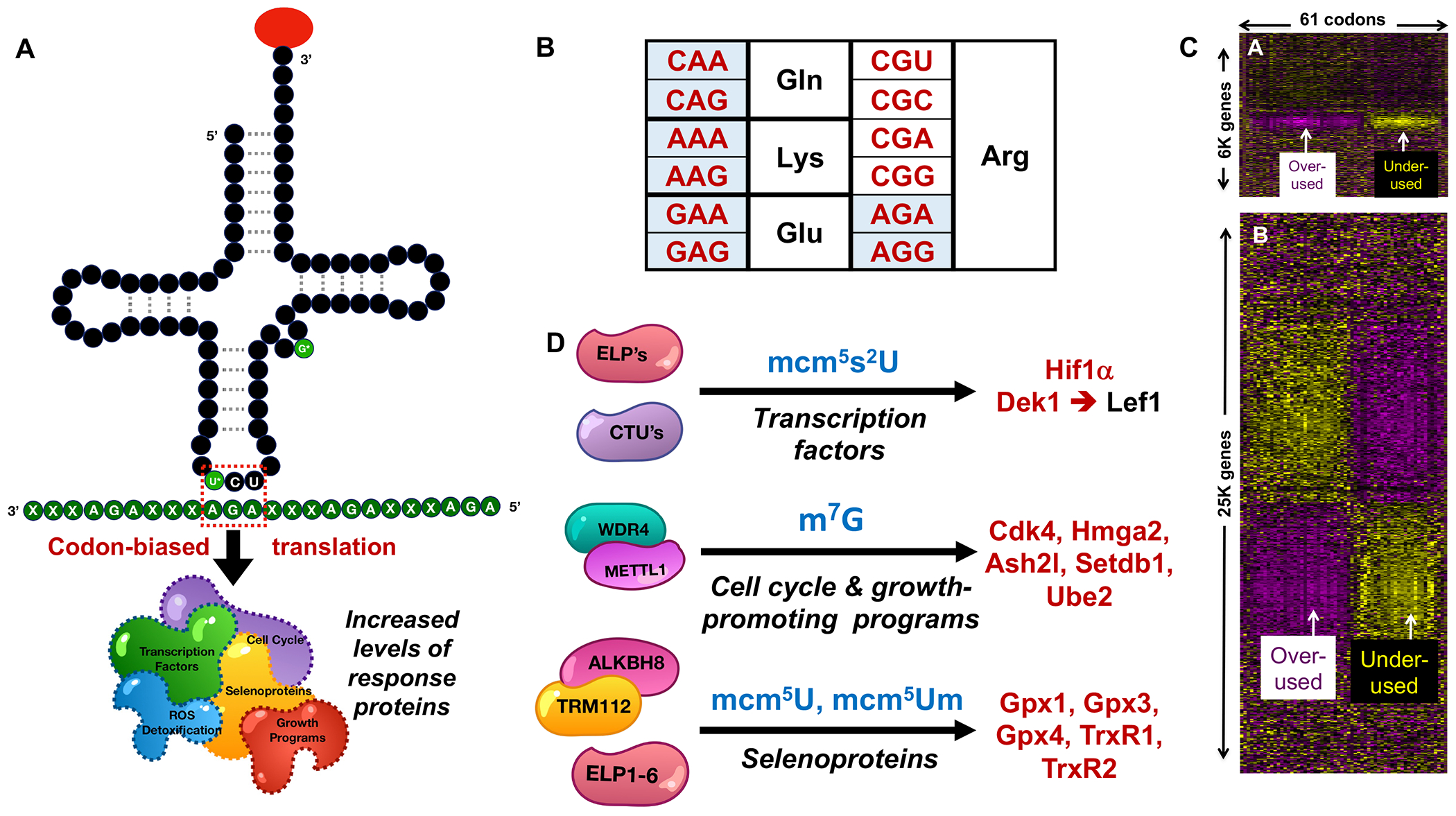

The tRNA epitranscriptome is linked to codon-biased translation: Biased codon use in stress responses and cancer.

A third contribution to the translational regulation of gene expression involves non-random use of the multiple synonymous codons for 19 of 21 amino acids in humans to drive codon-biased translational regulation (Fig. 3A–B). Using gene-specific codon counting algorithms with clustering and heat map-based visualization tools [31, 32, 67, 68], groups of genes with similar codon patterns can be visualized in most genomes, including S. cerevisiae and humans (Fig. 3C). For example, >400 of 5,700 genes in S. cerevisiae [31, 32, 67, 68],have highly biased use of specific synonymous codons, including over-use of many un-preferred (i.e., non-optimal) codons, relative to genome averages (Fig. 3C). These codon-biased genes represent specific gene families in yeast, including the environmental stress response (ESR) [31, 32, 67, 68], (p<10−9), which are over-represented in the functional categories of protein synthesis, energy utilization, stress/damage responses (p <10−5), and DNA damage response activities (p<1.5×10−6). Similarly in humans, gene-specific codon analysis on all human cDNAs reveals striking patterns of over- and under-usage of codons 1000’s of genes (Fig. 3C). Many of the codon-biased genes correspond to proteins with translation, DNA repair, ROS detoxification, stress response, cell cycle regulation, and metabolic functions [22, 31, 32, 67, 68, 69] That human cells use tRNA reprogramming linked to codon-biased translation is supported by studies showing tRNA-based epitranscriptomic reprogramming of colorectal cancer lines and mouse embryonic fibroblast in response to specific stressors, as well as by evidence for corruption of this program in cancer [17, 28].

Fig. 3. Variations of codon-biased translational regulation.

(A) tRNAs, modifications, anticodons, and mRNAs provide key control points regulating codon-biased translation of multiple types of proteins, here illustrated with tRNA-Arg-TCT and METTL1 modification with m7G at position 46 and a wobble U modification. (B) Blue-shaded synonymous codons for specific amino acids have been mechanistically linked to codon-biased translation. (C) Gene-specific codon counting reveals highly biased codon usage patterns in families of stress response genes. Heat maps of (upper panel) yeast and (lower panel) human gene-specific analyses reveal significant over- (yellow) and under-use (purple) of individual codons (columns) in 100’s of yeast and 1000’s of human genes (rows). These heat maps do not provide details about gene regulation per se, but instead highlight groups of genes that are heavily biased in usage of groups of codons, as detailed in a previous publication [68]. (D) Writers (left), modifications (middle), and proteins derived from targets of codon-biased translational regulation (right).

Corruption of the translational regulatory system in many forms of cancer is evident in the pathophysiological changes in codon-biased translation. For example, one study has shown that breast cancer cells are addicted to ELP3/CTU1/2-calatyzed wobble modifications in tRNAAsp and tRNAGlu due to codon-biased translation of oncoprotein DEK1, which promotes the IRES-dependent translation of the transcription factor LEF1 and a pro-invasion program [38] (Fig. 3D). In melanoma, it was shown that wobble U modifications promote resistance-driving glycolysis through the codon-dependent translational regulation of HIF-1A [22, 38]. Codon engineered versions of DEK1 or HIF-1A uncouple their translational regulation from specific tRNA modifications [22, 38]. Similarly, cell cycle regulatory genes are enriched with AGA codons and there is METTL1-dependent over-expression of these genes in AML, glioblastoma, liposarcomas, and possibly other tumors that also over-express METTL1, which modifies tRNAs that read AGA codons [27] (Fig. 3D). Bladder cancers have been shown to be addicted to the over-expression of ALKBH8, which regulates selenoprotein translation [70]. Further, selenoprotein dysregulation has been linked to the etiology of many cancers, with corresponding glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and thioredoxin reductases (TRXR) playing important roles regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and mitochondrial physiology [17, 20, 62, 71]. Selenoproteins contain the 21st amino acid selenocysteine, which is incorporated using a form of specialized translation termed stop-codon recoding [72–74]. There is no dedicated codon for selenocysteine, so an internal stop codon is recoded with the help of an epitranscriptomic mark written on tRNAsec by ALKBH8 to promote the synthesis of selenoproteins (Fig. 3D). The 25 human mRNAs for selenoproteins have multiple stop codons and are thus synthesized using a specialized form of codon bias [75].

Case studies of Translational Dysregulation in Cancer

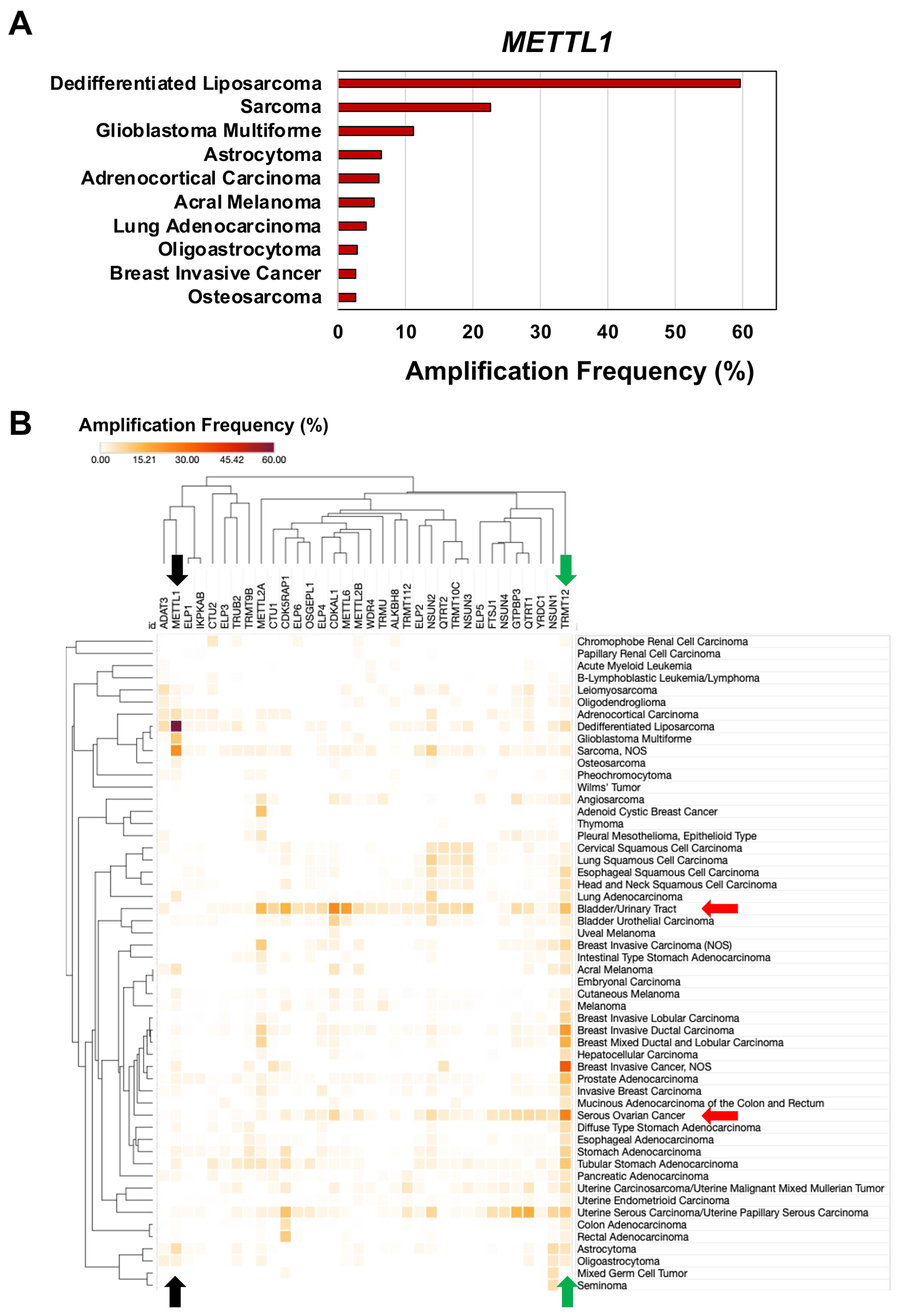

The three examples of epitranscriptome writers METTL1-WDR4, ELP1-6/CTU1-2 and ALKBH8-TRM112 driving cancer proliferation by enhancing translation of codon-biased mRNAs from oncogenic genes (Fig. 3D) demonstrate the complete molecular mechanism of pathological tRNA reprogramming and codon biased translation. How many other types of cancer exploit this mechanism? Which of the dozens of other epitranscriptome writers and hundreds of tRNA genes are corrupted in different cancers? While complete validation of tRNA reprogramming and codon biased translation is challenging due to the number of systems that need to be interrogated, surrogate markers in the form of gene copy number, RNA expression levels, and gene dependencies serve as a starting points to identify cancers potentially driven by translational dysfunction. And what better place to search for these markers than the immense datasets available in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [25], the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) [76–78], and the tRNA in Cancer (tRic) database [26]. Here we provide three case studies for mining these datasets for markers of tRNA reprogramming and codon-biased translation in cancer. Specifically, we focused on alterations in gene copy numbers for 34 RNA writers in 55 forms of cancer and specific to 47,534 patient samples (Figs. 4, 5), as well as mRNA expression levels and gene dependencies in 798 cell lines found in the CCLE (Fig. 6, Supplemental Fig. 1). In addition, we summarized tRNA expression levels for 492 isodecoders in 10,532 patient samples specific to 31 cancers (Supplemental Fig. 2). As detailed below, mining these three datasets reveal widespread dysregulation of writers and tRNAs in specific cancers and identify writer gene dependencies promoting cancer proliferation.

Fig. 4. Gene amplification changes for RNA modification writers in cancers.

(A) Bar graph detailing the top 10 cancers that have amplification of the gene for METTL. (B) Hierarchical clustering of gene amplifications for 34 writers in 55 cancers from 181 studies representing 47,534 samples in the TCGA. Data represent the alteration frequency, with a minimum of 50 total cases and a minimum of 1% alteration. Colored arrows highlight specific RNA-modifying proteins and cancers that are discussed in the text; black, METTL1; green, TRMT12; red, bladder/urinary tract cancer and serious ovarian cancer.

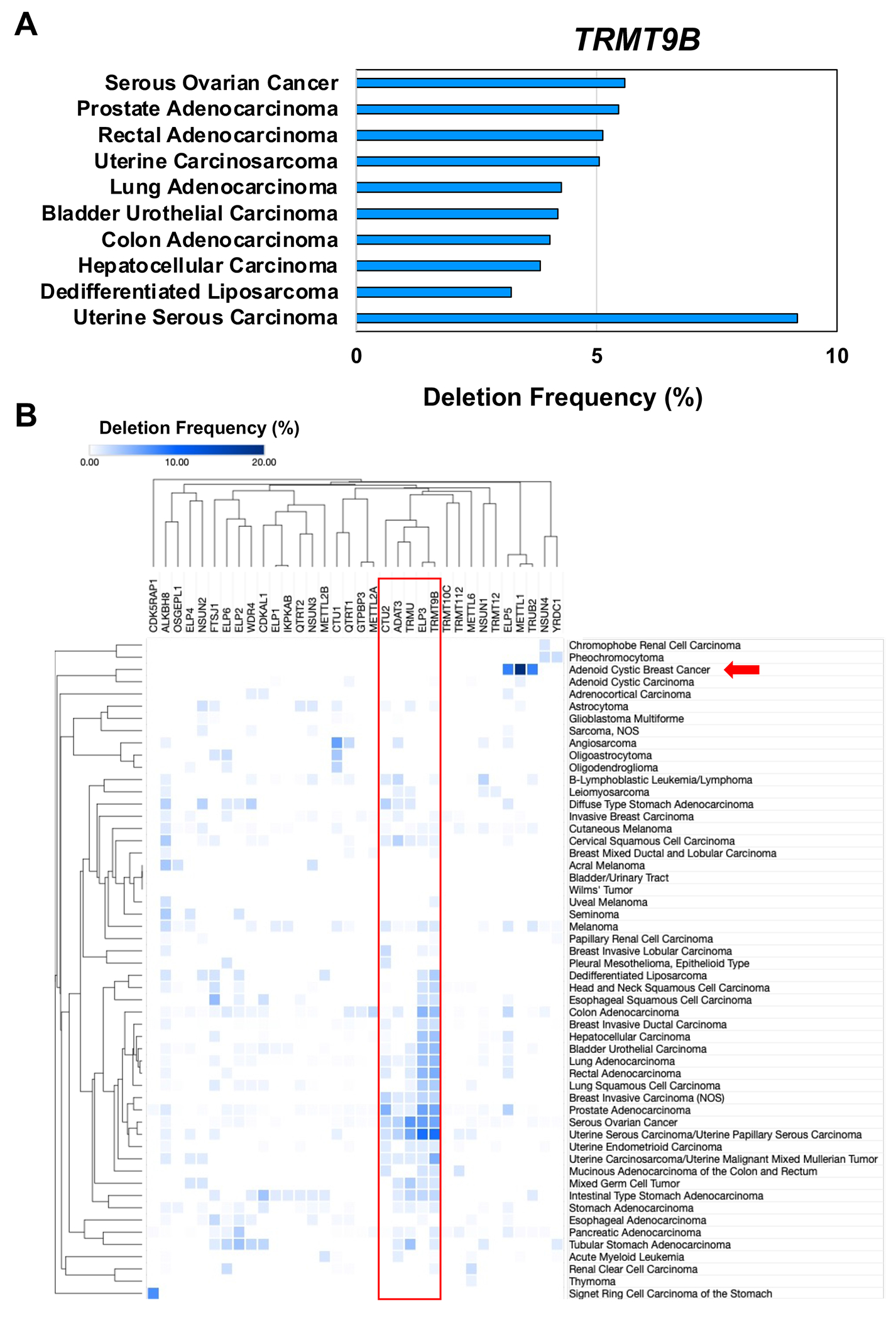

Fig. 5. Gene deletion changes for RNA modification writers in cancers.

(A) Bar graph detailing the top 10 cancers that have deletion of the gene for TRMT9B. (B) Hierarchical clustering of gene deletions for 34 writers in 55 cancers from 181 studies representing 47,534 samples in the TCGA. Data represent the alteration frequency, with a minimum of 50 total cases and a minimum of 1% alteration.

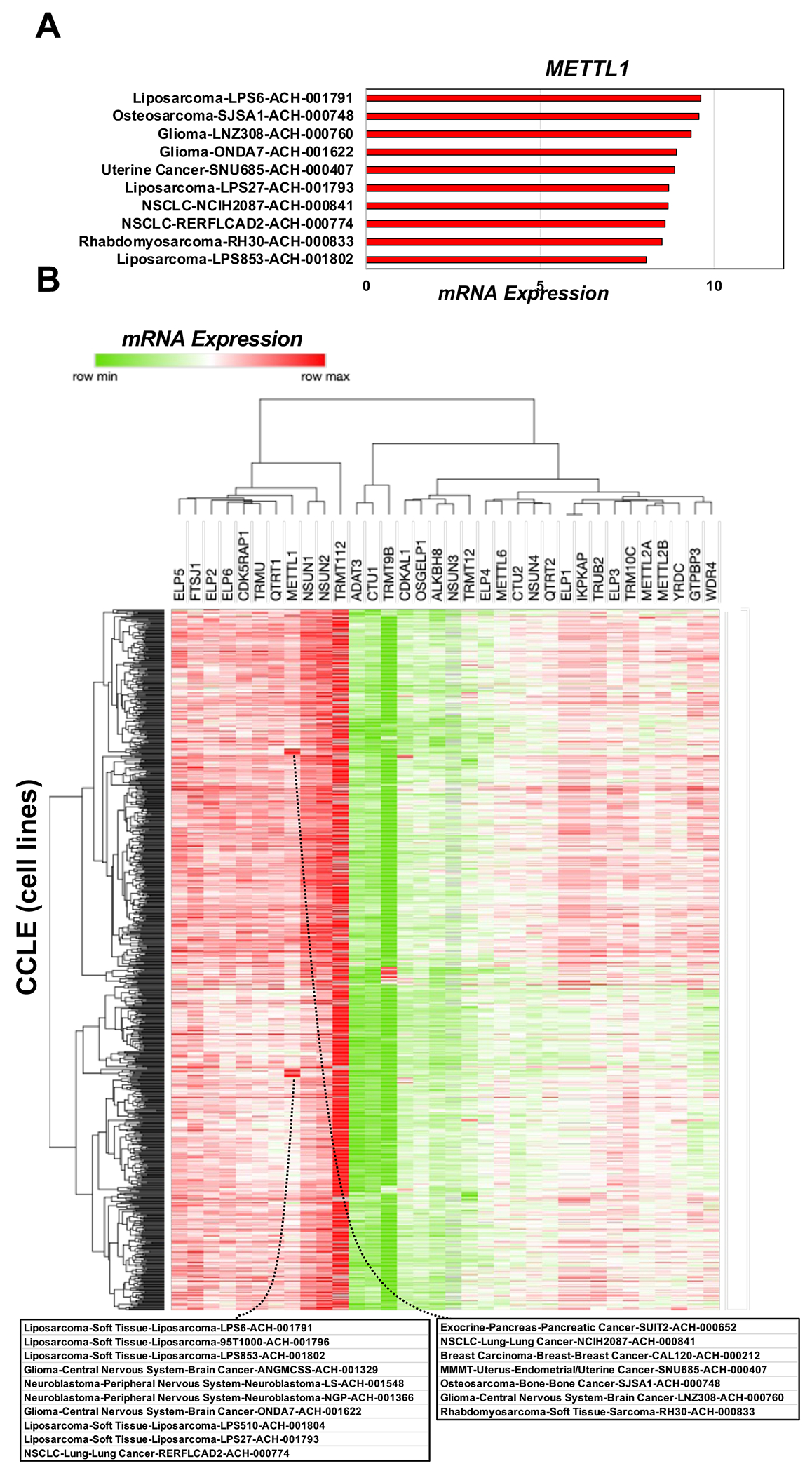

Fig. 6. Writer RNA expression data in cancers.

(A) Bar graph detailing the 10 cancer cell lines with increased METTL expression. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the log2(fold-change) values for mRNA expression for 34 writers in 798 CCLE samples found in DepMap (Expression 22Q1 Public).

Of the many metrics addressed in TCGA, we focused first on gene copy number variation (CNV), specifically gene amplifications, for 34 writers among the 55 specific cancers represented in TCGA (Fig. 4). As a paradigm for validating tRNA writers as regulators of cancer phenotype by epitranscriptome reprogramming and codon-biased translation (Fig. 4A), the high gene copy number for METTL1 has been established to result in high enzyme levels [27, 79]. Several notable features stand out in systems data, such as the high CNV specific to amplifications for the gene for the yW tRNA writer, TRMT12, in most of the cancers (Fig. 4B green arrow). Another example involves the extremely high percentage (~60%) of dedifferentiated liposarcomas with amplifications of the METTL1 gene, as well as high levels of METTL1 amplification in sarcomas and glioblastoma (Fig. 4B black arrow). Data from Fig. 4B also highlight increased gene copy numbers for multiple RNA writers in specific cancers. For example, bladder, and urinary tract cancers and serous ovarian cancer show increased amplification (>4%) for >20 and 9 writer genes, respectively (Fig. 4B, red arrows). This supports the idea that there could be codon-biased translation or translational dysfunction in these cancers worthy of further investigation.

Codon-biased translation was originally identified as regulating stress-response programs (Fig. 3) that are strongly linked to tumor growth suppression, so we also summarized CNV specific to gene deletions for 34 writers, which is shown in the heat map in Figure 5. As a paradigm for systems analysis, we provide deletion details specifically on TRMT9B (Fig. 5A), which is deleted in many cancers and an established tumor growth suppressor [28]. While TRMT9B does not have a defined RNA modification activity, it is known to be a phosphosignaling protein involved in regulating oxidative stress response [35]. TRMT9B has homology to the known wobble U RNA-modifying enzyme ALKBH8 and, like ALKBH8, is bound by the master methylation regulator TRMT112 [34, 35]. Using a systems-based approach and heat map visualization (Fig. 5B, red box), we observe that that adenoid cystic breast cancer shows frequent gene deletion specific to three RNA writers, METTL1, ELP5, and TRUB2 (Fig. 5B, red arrow), with METTL1 the most frequently deleted. While we have already described the roles for METTL1 and ELP5 in codon-biased translation, TRUB2 has not yet been implicated. TRUB2 catalyzes pseudouridine (Ψ) formation in mitochondrial tRNAs and deficiencies of this writer promote defects in mitochondrial translation and oxidative phosphorylation [80, 81]. This circumstantial evidence points to the potential involvement of TRUB2 in codon-biased translation, with its loss causing defects in mitochondrial function commonly associated with cancer progression and defects in oxidative phosphorylation as part of the Warburg effect that is a hallmark of cancer cell metabolism [82].

The heat map in Figure 5B also shows that some writer genes are deleted in many forms of cancer, such as the cluster of TRMT9B, ELP3, CTU2, TRMU and ADAT3 (Fig. 5B, red box). TRMU is a mitochondrial wobble U modification enzyme that catalyzes the 2-thiolation of 5-taurinomethyl-2-thiouridine (taum5s2U) on tRNAs for lysine, glutamine and glutamic acid [83], while ADAT3 is a characterized tRNA adenosine deaminase that catalyzes the formation of wobble inosines from adenosine [84]. While TRMT9B, ELP3, CTU2, TRMU, and ADAT3 are all linked to tRNA wobble ribonucleoside modifications, a known feature of codon-biased translation, further study is needed to determine if they are truly associated with selective translation of codon-biased mRNAs.

A third case study involves mRNA expression levels. Understanding of the molecular underpinnings of cancer has been limited by the lack of appropriately characterized model systems and their lack of genetic and lineage diversity. To address these limitations, the CCLE was created to provide systems-level distinctions among 947 cancer cell lines representing 36 different types of cancer [76–78, 85]. The CCLE project and the derivative Dependency Map (DepMap) project have annotated the cell lines with large datasets, including mRNA-seq and CRISPR-based loss-of-function [86–88]. We have summarized the mRNA expression of 34 writers in CCLE lines in Figure 6. METTL1 shows high levels of expression in liposarcomas, gliomas, and neuroblastoma (Fig. 6A–B) and is firmly linked to codon-biased translation in these tumors supports this idea. We also used heat maps to visualize the expression of many writers in many cancers (Fig. 6B). Here we see that TRM112 shows a high level of expression in many cancers, which is perhaps not surprising given its role as an essential binding partner for several writers [53, 63, 89–91]. Similarly, NSUN1 and NSUN2 writers are highly expressed in many different cancers. NSUN1 (also known as NOP2) is a putative m5C ribosomal writer. NSUN2 writes m5C in multiple RNAs and has been shown to be up-regulated by MYC, with known associations to cancers [92–94]. While neither NSUN1 nor NSUN2 have been linked to codon-biased translation, there will likely be both tRNA and ribosomal components linked to m5C methylation

We have also investigated the co-dependence of 34 writers with themselves and other genes for cancer cell proliferation. Here we used CCLE-derived DepMap to plot the CRISPR-based “Gene Effect” score heat map shown in Supplemental Figure 1, which quantifies the effects of specific writer deletions (columns) on the growth of each of 808 cell lines (rows) encompassing CCLE and other existing cell resources. A negative Gene Effect score indicates a dependency, with deletions of YRDC, TRM112, NSUN1, ELP1, ELP3, ELP5, and ELP6 specifically clustering together as a group that, when lost, has largely negative effects on growth for most cell lines. Loss of the N6-threonylcarbamoyltransferase YRDC, which has been previously implicated in hepatocellular carcinoma [95, 96], or TRMT112, the methyltransferase activator for at least four epitranscriptomic writers [53, 63, 89–91], led to a particularly striking and widespread negative gene effect score, which identifies both as common essential genes. In addition, many of the ELP enzymes, which participate in the formation of mcm5U and mcm5s2U and are linked to proteome stability and human diseases [22, 38, 97–102], have negative Gene Effect scores that classify their genes as common essential across many cancers. That the DepMap data provides surrogate markers for genes involved in codon-biased translation is again supported by the fact that TRMT112 and ELP enzymes have been mechanistically linked to codon-biased translational regulation, with YRDC a potential component.

Expression of tRNA isoacceptors and isodecoders serves as the third case study for codon-biased translation markers. The heat map in Supplemental Figure 2 uses data derived from the tRNA in Cancer database (tRic) [26], which was assembled from miRNA-seq data (i.e, RNA <200 nt) derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Here we summarize relative RNA-seq expression for 493 tRNA genes (columns) in 10,532 samples (rows) of 31 different cancers. We have highlighted two over-expressed isoacceptors: tRNA-Arg-TCT and tRNA-Ala-AGC in gliomas and ovarian serous cystadenocarcinomas, respectively. While the small RNA sequencing data derived from TCGA are largely not accurate for tRNAs due to a host of biases caused by the many modifications in all tRNAs and by very stable tRNA secondary structures [21], the tRic data for levels of the METTL1 substrate, tRNA-Arg-TCT, are consistent with published reports [27], with extremely high over-expression in glioma tumors. About 20% of gliomas have significant METTL1 over-expression and enhanced translation of genes enriched with the AGA codon read by tRNA-Arg-TCT. The heat map also supports the idea that tRNA-Ala-AGC is over-expressed in specific ovarian cancers (Supplemental Fig. 2), but there are no studies linking tRNA-Ala-AGC to codon-biased translation. Both tRNA-Arg-TCT and tRNA-Ala-AGC are reported to contain m7G, D, Y and m1A modifications [103]. In addition, tRNA-Arg-TCT also contains mcm5U, m1A, m1G, m3C, m5C, m5U, m7G, and t6A modifications, with tRNA-Ala-AGC containing the RNA modifications Gm, I, m1I, m2,2G, m2G and Um [103]. These two tRNAs and their modifications illustrate the potential for many other possible modifications that could participate in codon-biased translational regulation and provide a host of testable hypotheses for future studies. Further, application of a more accurate tRNA sequencing method to the TCGA tissues and CCLE cell lines could reveal less extreme tRNA dependencies in cancers driven by defective tRNA reprogramming and codon-biased translation.

Concluding Remarks

Dysregulated epitranscriptome systems have been linked to multiple diseases, with the key stress response system of codon-biased translation corrupted to increase the levels of growth promoting programs that drive cancer proliferation. The examples of METTL1, ELPs/CTUs, and ALKBH8 (Fig. 3) strongly illustrate this mechanism, which was recapitulated in the case studies of the systems-level cancer datasets. The case studies support the idea that codon-biased translation is used in distinct cancers and reveal other writers and tRNAs that could be linked to cancer etiology. Writers, tRNAs, epitranscriptomic marks, and biased codon use in mRNAs have emerged as mechanistic components of codon-based translational regulation of gene expression, with ribosomal and mitochondrial features also likely to be involved in coordination with the tRNA reprogramming. These discoveries now raise many Outstanding Questions about the future directions for tRNA epitranscriptome research and the potential implications of these mechanisms for human health. Not only do the enzymes in the pathways of codon-biased translation represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer, but the patterns of RNA modifications, mRNAs, and tRNAs have strong potential as signature biomarkers for cancer subtypes, for drug efficacy and toxicity in pre-clinical and clinical studies, and for patient selection in clinical trials of new cancer therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 2. Gene Deletions; Raw data for Figure 5B

Supplemental Table 1. Gene Amplifications; Raw data for Figure 4B

Supplemental Table 3. mRNA Expression; Raw data for Figure 6B

Supplemental Table 4. Gene Effect; Raw data for Supplemental Figure 1

Supplemental Fig. 1. The dependence of cancer cell growth on RNA writer genes: Gene Effect scores. Hierarchical clustering of DepMap chronos data detailing the “Gene Effect” scores that quantify the effect on cell growth when the corresponding writer target has been deleted in specific lines found in the CCLE using CRISPR. Negative numbers represent genes tin which the corresponding cells are dependent for growth, with −1 a median value for all common essential genes. The heat map displays 34 genes specific to RNA writers in 808 cells specific to the CCLE.

Supplemental Figure 2. tRNA expression data in cancers. Hierarchical clustering of relative RNA-seq expression for tRNAs (columns) in 10,532 samples of 31 cancers (rows). Two isoacceptors are highlighted: tRNA-Arg-TCT in brain lower grade glioma (green circle) and tRNA-Ala-AGC in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (blue circle).

Supplemental Table 5. tRNA Expression; Raw data for Supplemental Figure 2

Why focus on translational dysfunction and why now?

Translational dysfunction is now associated with more than 100 human diseases [2–8]. That cancer is prominent on this list might not be surprising given the well-established “addiction” of cancer cells to translation and to the levels of key proteins that drive proliferation and survival [9]. The normal process of messenger RNA (mRNA; see Glossary) translation is among the most well-established features of biology and the Central Dogma, so why has there only recently been an explosion of interest in translational dysfunction as the basis for human disease? One explanation lies in recent technological breakthroughs in RNA sequencing, mass spectrometry, and informatics, which have provided a systems-levels view of the molecular underpinnings of translational regulation of gene expression. This translation-based regulatory system itself comprises multiple cellular systems: the >50 modified nucleosides in mRNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNAs (tRNAs) that make up the epitranscriptome, the hundreds of enzymes that catalyze (i.e., write) the epitranscriptome, the pool >250 expressed tRNAs from over 500 tRNA genes, the dozens of ribosomal proteins and their proteoforms [10], and, most recently, alternative genetic information on mRNA in the form of biased use of synonymous codons. The only way to appreciate the coordinated activity in this system of systems is to apply a multi-omics approach. This is illustrated by our discovery that cells ranging from bacteria to humans respond to stress by reprogramming tRNA modifications and the tRNA pool to enhance translation of families of stress response mRNAs possessing biased use of codons matching the reprogrammed tRNA [11–21]. Disruption of this system by loss, mutation, or dysregulated transcription of genes for RNA modifying enzymes or tRNAs is now recognized as a major contributor to pathology and disease. For example, it was observed that over-expression of ELP3 drives melanomas with mutated BRAFV600E [22] by (1) increasing modification of tRNAs with ELP3-catalyzed wobble U modifications, which (2) increases the number of copies of these tRNAs thus (3) enhancing the translational efficiency of mRNAs enriched in their cognate codons, including tumor-driving proteins such as cell cycle regulators [22]. While this systems-level behavior has been recapitulated in multiple studies [23, 24], perhaps the best developed model for cancer-driving tRNA modifications and codon-biased translation involves over-expression of METTL1 in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), gliomas, sarcomas, and other cancers [25–27]. The m7G46 (see Box 1 for RNA modification nomenclature) modification catalyzed by METTL1 stabilizes tRNAs whose codons are enriched in mRNAs for cancer-driving cell proliferation genes [27]. Here we review the fundamental underpinnings of this mechanism of tRNA reprogramming and codon-biased translation and then provide several case studies illustrating the mechanistic diversity of translational dysfunction as a driver of disease, focusing on cancer etiology. As summarized in the Clinician’s Corner section, defective codon-biased translation as a disease driver has significant implications for discovery of therapeutic targets and development of biomarkers of disease and pathology.

Clinician’s Corner.

Dysfunctional protein synthesis at the level of translation elongation is now recognized as a major pathophysiological driver of many human diseases, most notably cancer.

Three examples of defective codon-biased translation in specific types of cancer illustrate the mechanistic steps that represent possible targets for therapeutic interventions including small molecule inhibitors of RNA-modifying enzymes, gene or RNA replacement for lost tRNAs, and drugs that directly react with RNA to reduce and enhance function.

The broad involvement of corrupted tRNA writers (hundreds), tRNA modifications (~50), tRNA genes (~500), and expressed tRNAs (~250) in many cancers is supported by systems-level analyses of cancer databases, which point to the potential utility of levels of modifications and tRNAs as biomarkers of disease risk and progression and therapeutic intervention, as well as companion diagnostics for epitranscriptome- and tRNA-based therapies.

The development of biomarkers of translational dysfunction in subsets of cancer patients requires preservation of the native epitranscriptome and tRNA pool in tumor samples. This requires rigorous control of tissue processing and preservation, such as rapid freezing of excised tumor tissues, to minimize translational changes due to artifactual environmental changes. We are challenged to develop a clinical tissue processing ecosystem that emphasizes rigorous tissue management.

Box 1: RNA modification nomenclature.

Using “m7G” as an example, the formal IUPAC name is 2-amino-9-[(2R,3R,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]-7-methyl-6-oxo-6,9-dihydro-1H-purin-7-ium and the common name is N7-methylguanosine. Abbreviations include the historical “m7G” and Modomics digital code “7G” [1]. The number following the modification name, as in m7G46, denotes the position of the modification in the RNA sequence.

Highlights.

While more than 150 chemical modifications of RNA in all organisms – the epitranscriptome – have fascinated researchers for decades, the recent discovery of systems-level function for the transfer RNA (tRNA) epitranscriptome has reignited broad interest.

As a system regulating gene expression at the level of translation, 50 modifications adorning 250 expressed tRNAs in humans reprogram during stress to selectively translate families of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) with biased use of synonymous codons.

Fascination with the tRNA epitranscriptome lies in the emerging appreciation that this system is corrupted in many human diseases.

Cancer databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) reveal widespread corruption of epitranscriptome writers and tRNA expression, pointing to broad involvement of codon-biased translation in many cancers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many students and staff researchers who, over the past 15 years of our collaboration, have developed the technologies and made the discoveries that serve as the foundation for this review article. The authors are also grateful for generous financial support from the National Institutes of Health (ES026856, ES031529, GM070641, ES024615, the US National Science Foundation (CHE 1308839), the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-17-1-0185), the National Research Foundation of Singapore through the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology Antimicrobial Resistance Interdisciplinary Research Group, the MIT - Spain ”la Caixa” Foundation Seed Fund, and the Agilent Foundation.

Glossary

- BRAFV600Em

A mutated, oncogenic version of the human gene for serine/threonine-protein kinase B-Raf, a proto-oncogene.

- Codon

One of 64 possible combinations of three of the four deoxyribonucleotides comprising DNA, with each codon specifying one amino acid and representing the basic unit of the genetic code. Redundant codons for the same amino acid are terms synonymous codons.

- Codon-biased translation

A stress response involving coordination among RNA writers, tRNA modifications, tRNA molecules, and the codon usage pattern of mRNAs to increase the translation and activity of specific proteins and pathways.

- CNV

copy number variation, in which the number of copies of a specific gene can be pathologically increased by mutation, sometimes leading to increased expression of the encoded protein

- CTU1, CTU2

Ctu1 and Ctu2 form a complex that catalyzes 2-thiolation of uridines (e.g., mcm5s2U) in a subset of tRNAs.

- ELP1-6

Elongator complex, a 6-subunit protein complex that catalyzes formation of 5-methoxycarbonylmethyluridine(mcm5U) and 5-carbamoylmethyluridine (ncm5U) at wobble positions in a subset of tRNAs. Elp3 has also been shown to acetylate histone proteins.

- ELP3

-

Elongator Complex Protein 3 is a component of the multiprotein Elongator Complex that catalyzes addition of carboxy-methyl moieties to position 5 in uridine bases located at the wobble position of the anticodon in some tRNAs. Elp3 possesses both histone acetyltransferase activity for transcriptional regulation as well as tRNA modification activity for translational regulation.

Elongator complex catalyzes posttranscriptional tRNA modifications by attaching carboxy-methyl (cm5) moieties to uridine bases located in the wobble position. The catalytic subunit Elp3 is highly conserved and harbors two individual subdomains, a radical S-adenosyl methionine (rSAM) and a lysine acetyltransferase (KAT) domain

- Epitranscriptome

The ~50 enzymatic modifications of ribonucleotides in all forms of RNA in all organisms.

- Epigenome

The ~5 enzymatic modifications of DNA and ~30 enzymatic modifications of histone proteins in eukaryotic organisms and >20 DNA modifications in bacteria, archaea, and bacteriophage. These DNA and protein modifications regulate transcription and serve as restriction-modification systems in prokaryotes.

- FTSJ1

tRNA methyltransferase catalyzing 2’-O-methylation of wobble (position 34) f5C and hm5C in tRNA to f5Cm and hm5Cm, respectively. FTSJ1 activity requires binding to non-catalytic WDR6.

- Gm

2’-O-methylguanosine, a methylated form of guanosine with the methyl group on the ribose sugar

- I

inosine, a deamination product of adenosine

- Isoacceptor

tRNAs that are charged with the same amino acid

- Isodecoder

tRNAs that have the same charged amino acid and identical anticodons but will have different sequence content in the tRNA.

- m1A

N1-methyladenosine, an unstable modification that converts to m6A in a reaction called the Dimroth rearrangement

- m3C

3-methylcytosine

- m5C

5-methylcytosine

- mchm5U

5-methoxycarbonylhydroxymethyluridine, a hydroxylated form of mcm5U occurring in two stereochemical forms (R and S configurations)

- mcm5U

5-Methoxycarbonylmethyluridine, a wobble uridine modification linked to ELPS, ALKBH8 and TRM112

- m1G

1-methylguanosine

- m2G

N2-methylguanosine

- m2,2G

N2,N2-dimethylguanosine

- m7G

7-Methylguanosine, a modified guanine linked to METTL1 and WDR4.

- m1I

1-methylinosine

- m5U

5-methyluridine, the equivalent to thymine in DNA

- mRNA

Messenger RNA, the gene transcript carrying the genetic code to the ribosome for translation into proteins.

- Omics

The nickname for the fields of study that typically possess the suffix “-ome”, such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, ribonucleomics, and soon. These fields address the entire collection – or system – of entities and molecules that comprise each field, with the term “omic” often referring to the technologies and tools used to discover and quantify all components of the field, such as mass spectrometry for quantifying thousands of different proteins (the proteome) or molecules (the metabolome) in a cell, and nucleic acid sequencing for studying thousands of genes (the genome) in a single genome and all of the transcripts (the transcriptome) produced from thoses genes in a cell. In the subdiscipline of systems biology, simultaneous quantification of molecular classes often reveals mechanistic behaviors (transcendent properties) not apparent when studying one molecule at a time.

- Proteoform

All possible forms of the protein product of one gene, including genetic variation, alternative splicing, and post-translational modifications[10].

- Ribonucleome

The collection of all forms of RNA in a cell, including mRNA, tRNA, rRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs, etc. Term first used by Suzuki and coworkers[104].

- rRNA

The three forms of ribosomal RNA in all cells, comprising 5S rRNA, 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA in humans.

- Selenocysteine

The 21st amino acid in which selenium replaces sulfur in the side chain. There is no codon for selenocysteine, so its tRNA uniquely reads internally positioned stop codons in the genes for selenoproteins.

- t6A

N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine, a modification specific to position 37 in the tRNA anticodon loop

- taum5s2U

5-taurinomethyl-2-thiouridine

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas was launched by the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute of NIH USA in 2006 to facilitate genomic and molecular characterization of over 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples.

- TRM112

The non-catalytic but essential binding partner of several human methyltransferases, including TRMT11 (m2G in tRNA), ALKBH8 (mcm5U and (S)-mchm5U in tRNA), HEMK2 (methylation of eRF1 protein for translation termination), RNMT2 (m7G in 18S rRNA) and possibly two other rRNA methyltransferases in humans[105].

- TRMT12

Also called TY2, TRMT12 is a tRNA methyltransferase that catalyzes the third step in the formation of wybutosine (yW).

- tRNA

Transfer RNA, the amino acid-containing adaptor molecule that reads the genetic code in mRNAs and transfers the coded amino acid into the growing peptide chain during translation of mRNA in the ribosome. tRNAs are named for the amino acid, the anticodon, and the specific gene encoding the tRNA. For example, the METTL1 substrate for m7G insertion, tRNA-Arg-TCT-4-1: carries arginine (Arg; the isotype of the tRNA), has 3’-UGU-5’ as the anticodon (T in the DNA gene represent U in the tRNA itself; underlined U/T is the wobble position 34), is the fourth isodecoder for tRNA-Arg-TCT (“4” is the unique ID for this isodecoder), and has been assigned to gene locus #1 in the genome (for multiple identical gene copies)

- Um

2’-O-methyluridine, a methylated form of uridine ribonucleoside with the methyl group on the ribose sugar

- WDR4

Like TRM112, WDR4 is the non-catalytic component of the METTL1-WDR4 methyltransferase complex.

- yW

The tRNA modification wybutosine.

References

- 1.Boccaletto P et al. (2022) MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res 50 (D1), D231–D235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonkhout N et al. (2017) The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA 23 (12), 1754–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nachtergaele S and He C (2017) The emerging biology of RNA post-transcriptional modifications. RNA Biol 14 (2), 156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapino F et al. (2017) tRNA Modification: Is Cancer Having a Wobble? Trends Cancer 3 (4), 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres AG et al. (2014) Role of tRNA modifications in human diseases. Trends Mol Med 20 (6), 306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafik AM et al. (2021) Dysregulated mitochondrial and cytosolic tRNA m1A methylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbieri I and Kouzarides T (2020) Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boriack-Sjodin PA et al. (2018) RNA-modifying proteins as anticancer drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17 (6), 435–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truitt ML and Ruggero D (2016) New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Cancer 16 (5), 288–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith LM et al. (2013) Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity. Nat Methods 10 (3), 186–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CT et al. (2010) A quantitative systems approach reveals dynamic control of tRNA modifications during cellular stress. PLoS Genet 6 (12), e1001247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan CT et al. (2012) Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nat Commun 3, 937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patil A et al. (2012) Increased tRNA modification and gene-specific codon usage regulate cell cycle progression during the DNA damage response. Cell Cycle 11 (19), 3656–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu C et al. (2014) tRNA modifications regulate translation during cellular stress. FEBS Lett 588 (23), 4287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan CT et al. (2015) Highly Predictive Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications Is Linked to Selective Expression of Codon-Biased Genes. Chem Res Toxicol 28 (5), 978–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng W et al. (2015) Trm9-Catalyzed tRNA Modifications Regulate Global Protein Expression by Codon-Biased Translation. PLoS Genet 11 (12), e1005706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endres L et al. (2015) Alkbh8 Regulates Selenocysteine-Protein Expression to Protect against Reactive Oxygen Species Damage. PLoS One 10 (7), e0131335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chionh YH et al. (2016) tRNA-mediated codon-biased translation in mycobacterial hypoxic persistence. Nat Commun 7, 13302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng CS et al. (2018) tRNA epitranscriptomics and biased codon are linked to proteome expression in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Syst Biol 14, e8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonardi A et al. (2020) The epitranscriptomic writer ALKBH8 drives tolerance and protects mouse lungs from the environmental pollutant naphthalene. Epigenetics 15 (10), 1121–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu JF et al. (2021) Quantitative mapping of the cellular small RNA landscape with AQRNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol 39 (8), 978–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rapino F et al. (2018) Codon-specific translation reprogramming promotes resistance to targeted therapy. Nature 558 (7711), 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodarzi H et al. (2016) Modulated Expression of Specific tRNAs Drives Gene Expression and Cancer Progression. Cell 165 (6), 1416–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gingold H et al. (2014) A dual program for translation regulation in cellular proliferation and differentiation. Cell 158 (6), 1281–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute NC, The Cancer Genome Atlas, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z et al. (2020) tRic: a user-friendly data portal to explore the expression landscape of tRNAs in human cancers. RNA Biol 17 (11), 1674–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orellana EA et al. (2021) METTL1-mediated m(7)G modification of Arg-TCT tRNA drives oncogenic transformation. Mol Cell 81 (16), 3323–3338 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Begley U et al. (2013) A human tRNA methyltransferase 9-like protein prevents tumour growth by regulating LIN9 and HIF1-alpha. EMBO Mol Med 5 (3), 366–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai WM et al. (2015) A Platform for Discovery and Quantification of Modified Ribonucleosides in RNA: Application to Stress-Induced Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications. Methods Enzymol 560, 29–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dedon PC and Begley TJ (2014) A system of RNA modifications and biased codon use controls cellular stress response at the level of translation. Chem Res Toxicol 27 (3), 330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng W et al. (2015) Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications promote translation by directly regulating expression of ribosomal proteins. PLoS Genetics 11 (12), e1005706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doyle F et al. (2016) Gene- and genome-based analysis of significant codon patterns in yeast, rat and mice genomes with the CUT Codon UTilization tool. Methods 107, 98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fry RC et al. (2006) The DNA-damage signature in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is associated with single-strand breaks in DNA. BMC Genomics 7, 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu D et al. (2010) Human AlkB homolog ABH8 Is a tRNA methyltransferase required for wobble uridine modification and DNA damage survival. Mol Cell Biol 30 (10), 2449–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu C et al. (2018) Phosphorylation of human TRM9L integrates multiple stress-signaling pathways for tumor growth suppression. Sci Adv 4 (7), eaas9184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patil A et al. (2012) Translational infidelity-induced protein stress results from a deficiency in Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications. RNA Biol 9 (7), 990–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothenberg DA et al. (2018) A Proteomics Approach to Profiling the Temporal Translational Response to Stress and Growth. iScience 9, 367–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaunay S et al. (2016) Elp3 links tRNA modification to IRES-dependent translation of LEF1 to sustain metastasis in breast cancer. J Exp Med 213 (11), 2503–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lentini JM et al. (2020) DALRD3 encodes a protein mutated in epileptic encephalopathy that targets arginine tRNAs for 3-methylcytosine modification. Nat Commun 11 (1), 2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iben JR and Maraia RJ (2012) tRNAomics: tRNA gene copy number variation and codon use provide bioinformatic evidence of a new anticodon:codon wobble pair in a eukaryote. RNA 18 (7), 1358–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan PP and Lowe TM (2016) GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 44 (D1), D184–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres AG et al. (2019) Differential expression of human tRNA genes drives the abundance of tRNA-derived fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116 (17), 8451–8456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sagi D et al. (2016) Tissue- and Time-Specific Expression of Otherwise Identical tRNA Genes. PLoS Genet 12 (8), e1006264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dittmar KA et al. (2006) Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet 2 (12), e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pang YL et al. (2014) Diverse cell stresses induce unique patterns of tRNA up- and down-regulation: tRNA-seq for quantifying changes in tRNA copy number. Nucleic Acids Res 42 (22), e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavon-Eternod M et al. (2009) tRNA over-expression in breast cancer and functional consequences. Nucleic Acids Res 37 (21), 7268–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer KD and Jaffrey SR (2014) The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15 (5), 313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCown PJ et al. (2020) Naturally occurring modified ribonucleosides. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 11 (5), e1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cantara WA et al. (2011) The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res 39 (Database issue), D195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki T (2021) The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 22 (6), 375–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprinzl M et al. (1998) Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 26 (1), 148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Towns WL and Begley TJ (2012) Transfer RNA methytransferases and their corresponding modifications in budding yeast and humans: activities, predications, and potential roles in human health. DNA Cell Biol 31 (4), 434–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guy MP and Phizicky EM (2014) Two-subunit enzymes involved in eukaryotic post-transcriptional tRNA modification. RNA Biol 11 (12), 1608–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin S et al. (2018) Mettl1/Wdr4-Mediated m(7)G tRNA Methylome Is Required for Normal mRNA Translation and Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Mol Cell 71 (2), 244–255 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agris PF (2004) Decoding the genome: a modified view. Nucleic Acids Res 32 (1), 223–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashraf SS et al. (1999) The uridine in “U-turn”: contributions to tRNA-ribosomal binding. RNA 5 (4), 503–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ashraf SS et al. (2000) Role of modified nucleosides of yeast tRNA(Phe) in ribosomal binding. Cell Biochem Biophys 33 (3), 241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy F.V.t. et al. (2004) The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys)UUU. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11 (12), 1186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarian C et al. (2000) Modified nucleoside dependent Watson-Crick and wobble codon binding by tRNALysUUU species. Biochemistry 39 (44), 13390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yarian C et al. (2002) Accurate translation of the genetic code depends on tRNA modified nucleosides. J Biol Chem 277 (19), 16391–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Motorin Y and Helm M (2010) tRNA stabilization by modified nucleotides. Biochemistry 49 (24), 4934–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leonardi A et al. (2019) Epitranscriptomic systems regulate the translation of reactive oxygen species detoxifying and disease linked selenoproteins. Free Radic Biol Med 143, 573–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Songe-Moller L et al. (2010) Mammalian ALKBH8 possesses tRNA methyltransferase activity required for the biogenesis of multiple wobble uridine modifications implicated in translational decoding. Mol Cell Biol 30 (7), 1814–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monies D et al. (2019) Recessive Truncating Mutations in ALKBH8 Cause Intellectual Disability and Severe Impairment of Wobble Uridine Modification. Am J Hum Genet 104 (6), 1202–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee MY et al. (2020) Loss of epitranscriptomic control of selenocysteine utilization engages senescence and mitochondrial reprogramming(). Redox Biol 28, 101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohshio I et al. (2016) ALKBH8 promotes bladder cancer growth and progression through regulating the expression of survivin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 477 (3), 413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tumu S et al. (2012) The gene-specific codon counting database: a genome-based catalog of one-, two-, three-, four- and five-codon combinations present in Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes. Database (Oxford) 2012, bas002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Begley U et al. (2007) Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications link translation to the DNA damage response. Mol Cell 28 (5), 860–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huber S et al. (2022) Arsenic toxicity is regulated by queuine availability and oxidation-induced reprogramming of the human tRNA epitranscriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimada K et al. (2009) A novel human AlkB homologue, ALKBH8, contributes to human bladder cancer progression. Cancer Res 69 (7), 3157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis CD et al. (2012) Selenoproteins and cancer prevention. Annu Rev Nutr 32, 73–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Driscoll DM and Copeland PR (2003) Mechanism and regulation of selenoprotein synthesis. Annu Rev Nutr 23, 17–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gladyshev VN and Hatfield DL (1999) Selenocysteine-containing proteins in mammals. J Biomed Sci 6 (3), 151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Novoselov SV et al. (2005) Selenoprotein deficiency and high levels of selenium compounds can effectively inhibit hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene 24 (54), 8003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kryukov GV et al. (2003) Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science 300 (5624), 1439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barretina J et al. (2012) The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483 (7391), 603–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghandi M et al. (2019) Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature 569 (7757), 503–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nusinow DP et al. (2020) Quantitative Proteomics of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Cell 180 (2), 387–402 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma J et al. (2021) METTL1/WDR4-mediated m(7)G tRNA modifications and m(7)G codon usage promote mRNA translation and lung cancer progression. Mol Ther 29 (12), 3422–3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mukhopadhyay S et al. (2021) Mammalian nuclear TRUB1, mitochondrial TRUB2, and cytoplasmic PUS10 produce conserved pseudouridine 55 in different sets of tRNA. RNA 27 (1), 66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antonicka H et al. (2017) A pseudouridine synthase module is essential for mitochondrial protein synthesis and cell viability. EMBO Rep 18 (1), 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Warburg O (1956) On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science 124 (3215), 269–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Umeda N et al. (2005) Mitochondria-specific RNA-modifying enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of the wobble base in mitochondrial tRNAs. Implications for the molecular pathogenesis of human mitochondrial diseases. J Biol Chem 280 (2), 1613–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramos J et al. (2020) Identification and rescue of a tRNA wobble inosine deficiency causing intellectual disability disorder. RNA 26 (11), 1654–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li H et al. (2019) The landscape of cancer cell line metabolism. Nat Med 25 (5), 850–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McDonald ER 3rd et al. (2017) Project DRIVE: A Compendium of Cancer Dependencies and Synthetic Lethal Relationships Uncovered by Large-Scale, Deep RNAi Screening. Cell 170 (3), 577–592 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsherniak A et al. (2017) Defining a Cancer Dependency Map. Cell 170 (3), 564–576 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dempster JM et al. (2019) Agreement between two large pan-cancer CRISPR-Cas9 gene dependency data sets. Nat Commun 10 (1), 5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lentini JM et al. (2018) Monitoring the 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine (mcm5s2U) modification in eukaryotic tRNAs via the gamma-toxin endonuclease. RNA 24 (5), 749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mazauric MH et al. (2010) Trm112p is a 15-kDa zinc finger protein essential for the activity of two tRNA and one protein methyltransferases in yeast. J Biol Chem 285 (24), 18505–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Purushothaman SK et al. (2005) Trm11p and Trm112p Are both Required for the Formation of 2-Methylguanosine at Position 10 in Yeast tRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol 25 (11), 4359–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xu X et al. (2020) NSun2 promotes cell migration through methylating autotaxin mRNA. J Biol Chem 295 (52), 18134–18147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chellamuthu A and Gray SG (2020) The RNA Methyltransferase NSUN2 and Its Potential Roles in Cancer. Cells 9 (8), 1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frye M and Watt FM (2006) The RNA methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) mediates Myc-induced proliferation and is upregulated in tumors. Curr Biol 16 (10), 971–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arrondel C et al. (2019) Defects in t(6)A tRNA modification due to GON7 and YRDC mutations lead to Galloway-Mowat syndrome. Nat Commun 10 (1), 3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang S et al. (2019) Modulation of YrdC promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 114, 108859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shaheen R et al. (2019) Biallelic variants in CTU2 cause DREAM-PL syndrome and impair thiolation of tRNA wobble U34. Hum Mutat 40 (11), 2108–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nedialkova DD and Leidel SA (2015) Optimization of Codon Translation Rates via tRNA Modifications Maintains Proteome Integrity. Cell 161 (7), 1606–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dewez M et al. (2008) The conserved Wobble uridine tRNA thiolase Ctu1-Ctu2 is required to maintain genome integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (14), 5459–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rapino F et al. (2021) Wobble tRNA modification and hydrophilic amino acid patterns dictate protein fate. Nat Commun 12 (1), 2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rosu A et al. (2021) Loss of tRNA-modifying enzyme Elp3 activates a p53-dependent antitumor checkpoint in hematopoiesis. J Exp Med 218 (3), e20200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zanut A et al. (2020) Insights into the mechanism of coreactant electrochemiluminescence facilitating enhanced bioanalytical performance. Nat Commun 11 (1), 2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.de Crecy-Lagard V et al. (2019) Matching tRNA modifications in humans to their known and predicted enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 47 (5), 2143–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ikeuchi Y et al. (2006) Mechanistic insights into sulfur relay by multiple sulfur mediators involved in thiouridine biosynthesis at tRNA wobble positions. Mol Cell 21 (1), 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bourgeois G et al. (2017) Trm112, a Protein Activator of Methyltransferases Modifying Actors of the Eukaryotic Translational Apparatus. Biomolecules 7 (1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 2. Gene Deletions; Raw data for Figure 5B

Supplemental Table 1. Gene Amplifications; Raw data for Figure 4B

Supplemental Table 3. mRNA Expression; Raw data for Figure 6B

Supplemental Table 4. Gene Effect; Raw data for Supplemental Figure 1

Supplemental Fig. 1. The dependence of cancer cell growth on RNA writer genes: Gene Effect scores. Hierarchical clustering of DepMap chronos data detailing the “Gene Effect” scores that quantify the effect on cell growth when the corresponding writer target has been deleted in specific lines found in the CCLE using CRISPR. Negative numbers represent genes tin which the corresponding cells are dependent for growth, with −1 a median value for all common essential genes. The heat map displays 34 genes specific to RNA writers in 808 cells specific to the CCLE.

Supplemental Figure 2. tRNA expression data in cancers. Hierarchical clustering of relative RNA-seq expression for tRNAs (columns) in 10,532 samples of 31 cancers (rows). Two isoacceptors are highlighted: tRNA-Arg-TCT in brain lower grade glioma (green circle) and tRNA-Ala-AGC in ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (blue circle).

Supplemental Table 5. tRNA Expression; Raw data for Supplemental Figure 2