Abstract

Background.

Hypersomnolence has been considered a prominent feature of Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) despite mixed research findings. In the largest multi-season study conducted to date, we aimed to clarify the nature and extent of hypersomnolence in SAD using multiple measurements during winter depressive episodes and summer remission.

Methods.

Sleep measurements assessed in individuals with SAD and nonseasonal, never-depressed controls included actigraphy, daily sleep diaries, retrospective self-report questionnaires, and self-reported hypersomnia assessed via clinical interview. To characterize hypersomnolence in SAD we 1) compared sleep between diagnostic groups and seasons, 2) examined correlates of self-reported hypersomnia in SAD, and 3) assessed agreement between commonly used measurement modalities.

Results.

In winter compared to summer, individuals with SAD (n = 64) reported sleeping 72 minutes longer based on clinical interviews (p<.001) and 23 minutes longer based on actigraphy (p=.011). Controls (n = 80) did not differ across seasons. There were no seasonal or group differences on total sleep time when assessed by sleep diaries or retrospective self-reports (p’s>.05). Endorsement of winter hypersomnia in SAD participants was predicted by greater fatigue, total sleep time, time in bed, naps, and later sleep midpoints (p’s<.05).

Conclusion.

Despite a winter increase in total sleep time and year-round elevated daytime sleepiness, the average total sleep time (7 hours) and daytime sleepiness suggest hypersomnolence is a poor characterization of SAD. Importantly, self-reported hypersomnia captures multiple sleep disruptions, not solely lengthened sleep duration. We recommend using a multimodal assessment of hypersomnolence in mood disorders prior to sleep intervention.

Keywords: Depression, sleep, hypersomnia, hypersomnolence, actigraphy, seasonal affective disorder

Major Depressive Disorder with Seasonal Pattern (Seasonal Affective Disorder; SAD) typically recurs in fall and winter and spontaneously remits in spring and summer (American Psychological Association, 2013). Seasonal changes in light exposure are thought to result in circadian misalignment and disturbed sleep patterns in SAD (Lewy et al., 1988) including hypersomnolence, an excessive quantity of nighttime sleep (i.e., hypersomnia), daytime sleepiness, and/or sleep inertia (i.e., diminished sensory, motor, and cognitive function upon waking American Psychological Association, 2013). Hypersomnia is considered a prominent symptom in SAD (Rosenthal, 1984; Kaplan and Harvey, 2009), despite discrepancies between self-report and behavioral measures of winter total sleep time (Kaplan and Harvey, 2009). It remains unclear whether hypersomnolent presentations are symptoms of winter depressive episodes or residual symptoms during summer remission. Hypersomnolence in mood disorders has been associated with treatment resistance and episode recurrence (Breslau et al., 1996; Zimmerman et al., 2005; Kaplan et al., 2011; Plante et al., 2017), underscoring the importance of understanding hypersomnolence in SAD. Multiple sleep measurements in-and-out of depressive episodes are critical for determining both the magnitude and time course of hypersomnolence in SAD.

Our current understanding of hypersomnolence in SAD may be inaccurate and primarily focuses on excessive sleep duration (i.e., hypersomnia). While a majority (64-87%) of SAD participants report a winter increase in total sleep time (Winkler et al., 2002; Kaplan and Harvey, 2009; Roecklein et al., 2013) on questionnaires (e.g., Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire; Magnusson, 1996) and clinical interviews (e.g., Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Seasonal Affective Disorder Version (SIGH-SAD; Williams et al., 1992), these metrics are mood-state dependent and vulnerable to retrospective recall bias. Prospective sleep diaries have similar limitations and show mixed findings of winter hypersomnia (Anderson et al., 1994; Shapiro et al., 1994). Using actigraphy (Sadeh, 2011), an underutilized and behavioral sleep metric in SAD, individuals with SAD (n=17) had shorter winter sleep durations than controls and more fragmented sleep, with no differences in total sleep time (Winkler et al., 2005). Seasonal comparisons of rest-activity rhythms in SAD showed winter early evening settling (down-mesor), which correlated with greater fatigue (Smagula et al., 2018). Notably, self-reported hypersomnia in depression may be a function of long total sleep time, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, increased time in bed, maladaptive sleep cognitions, and/or fragmented sleep (Kaplan and Harvey, 2009; Harvey, 2011; Roecklein et al., 2013). It is possible that multiple sleep disruptions may be conflated with self-reported hypersomnia in SAD. To systematically characterize the extent and nature of hypersomnolence in SAD we employed a comprehensive assessment of actigraphy, sleep diaries, and retrospective self-reports during winter depressive episodes and summer remission.

Self-reported hypersomnolence in SAD may be an artifact of delayed circadian timing. Low winter environmental light levels are hypothesized to delay circadian timing in SAD leading to misalignment with the sleep/wake cycle (Lewy et al., 2006). Misalignment resulting from delayed circadian timing can manifest behaviorally as sleep onset insomnia and morning sleep inertia. After a night of difficulty initiating sleep, individuals might sleep-in the next morning, nap, or sleep longer the following night (Bond and Wooten, 1996), which may be experienced subjectively as excessive sleep duration and/or daytime sleepiness.

The current study aims to address discrepancies surrounding hypersomnolence in SAD by characterizing sleep in SAD using multiple metrics, across seasons, and relative to nonseasonal, never-depressed controls. Our first aim compared seasonal changes in total sleep time, time in bed, sleep fragmentation, sleep midpoint, regularity, and sleepiness between participants with SAD and controls on actigraphy, sleep diaries, and retrospective self-report measures. We included sleep midpoint as a proxy for circadian timing, and regularity of total sleep time to measure oscillations of nightly sleep length. Our second aim examined correlates of self-reported winter hypersomnolence in SAD. Our third aim measured agreement between self-report and actigraphic measures of total sleep time.

Methods

Participants

We recruited participants aged 18-65 through the Pitt+Me® Research Participant Registry, an institutional research participant registry in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (latitude 40°26′N) from 2013-2019. Study procedures were explained prior to obtaining and documenting informed consent. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures prior to participant recruitment, and the research was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 1989. Individuals with a substance-induced mood disorder, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, sleep disordered breathing, narcolepsy, or shift-workers were excluded. Participants completed a health questionnaire that assessed retinopathology (as part of a larger study looking at retinal responsivity in SAD) and sleep disorders. Both controls and individuals with SAD were invited to complete a semi-structured interview, questionnaires, and sleep diaries and actigraphy measures. Participants were assessed in the winter (December 21st to March 21st) during a major depressive episode and during spontaneous summer remission (June 21st to September 21st). The following assessments were used to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Clinical Assessments

SCID

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen was used to assess for a lifetime mood disorder diagnoses and to screen for select comorbid Axis I disorders (SCID-I/P; First, 2015)). Individuals in the SAD group were diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder with Seasonal Pattern. Individuals in the control group had no lifetime history of any mood disorder.

SIGH-SAD

The Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression—Seasonal Affective Disorder Version (SIGH-SAD) is the most commonly used clinical assessment for measuring SAD symptoms (Williams et al., 1992) and has been shown to have high inter-rater reliability (.923-.967; Rohan et al., 2016). The SIGH-SAD is a 29-item semi-structured interview that includes the 21-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and eight items assessing atypical symptoms of depression. Inclusion criteria for SAD was a total SIGH-SAD score of ≥ 20 with ≥ 5 on the atypical depressive symptom subscale (Terman et al., 1990). Individuals in the control group did not meet criteria for a current episode in either season. Reports from SIGH-SAD item A6 were used to characterize self-reported hypersomnolence in aim 2. The SIGH-SAD assesses hypersomnolence by asking individuals: “Have you been sleeping more than usual this past month? How much more?” with responses selected from (0) no increase in sleep length, (1) at least one hour longer, (2) at least two hours longer, (3) at least three hours longer, or (4) four or more hours longer. Interviewers must first establish euthymic (i.e., summer) total sleep time, as well as current total sleep time, and include naps in the estimate of total daily total sleep time averaged across the past week when scoring this item.

Self-report questionnaires

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a self-report measure of sleep characteristics and quality (Buysse et al., 1989). It distinguishes “good sleepers” from “poor sleepers” with high specificity and has a high internal consistency (Cronbach α=0.85;Buysse et al., 1989). The global PSQI score ranges from scores of 0 to 21 with higher scores being more indicative of disturbed sleep. We extracted self-reported measures of total sleep time and time in bed from the PSQI for analyses.

Chalder Fatigue Measure (CFM)

The CFM is a self-report measure of the severity of physical and mental fatigue (Chalder et al., 1993). Participants rate 11-items as being less than usual=0, no more than usual=1, worse than usual=2, or much worse than usual=3 (Chalder et al., 1993). All items are summed for a total CFM score. The CFM has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.89), and internal reliability (r=0.86 for physical fatigue, and r=0.85 for mental fatigue; Chalder et al., 1993). Total scores for the CFM were used to predict hypersomnia in aim 2.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

The ESS is a self-report scale in which participants rate their likelihood of dozing off under various circumstances from 0 (no chance) to 3 (high chance; (Johns, 1991). Scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater daytime sleepiness. The ESS has a high test-retest reliability in healthy individuals over a 5-month period (r=0.82) as well as a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.88; Johns, 1991). The ESS total score was compared across groups and seasons in aim 1 and used as a predictor of self-reported hypersomnia in aim 2.

Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM)

The CSM is a 13-item self-report scale of circadian preference, in which participants rate their propensity for sleep and activity timing (Smith et al., 1989). Scores range from 13 to 55, with higher scores indicative of earlier circadian preference (13–26 evening-preference; 27–41 intermediate-preference; 42–55 morning-preference; Natale and Alzani, 2001). The CSM total score was used as a predictor of self-reported hypersomnia in aim 2.

Sleep Diaries

Participants completed daily sleep diaries (Buysse et al., 1989) for 5-20 nights (average of 8.41 nights). The sleep diary variables reported include: 1) Time in Bed: the duration between ‘went to bed time’ and ‘woke up time’, 2) Total sleep time: the duration of sleep between ‘lights out time’ and ‘woke up time’ after accounting for both sleep onset latency and nighttime awakenings, 3) Wake time after sleep onset (WASO): the number of minutes participants reported being awake during the night, 4) Sleep midpoint: a proxy for circadian timing to determine if self-reports of hypersomnolence are a function of delayed sleep timing, and 5) 24-hour total sleep time: total sleep time plus the duration of daytime naps.

Actigraphy

Participants wore an Actiwatch Spectrum (Philips Respironics, Bend, OR, USA) on their non-dominant wrist for 5-26 days (average of 10 nights). Actigraphy data were recorded continuously and sampled in 30-second epochs. The actigraphy-based sleep-wake variables were determined using the Actiware software program (Philips Respironics) with total activity counts above the threshold sensitivity value of 40 counts/per epoch. Rest intervals were manually set using sleep diary information, event markers, and/or a cutoff of activity below 40 counts. These rest intervals bookended our determination of time in bed.

The actigraphy variables being reported include: 1) Time in Bed: the duration between onset and offset of the rest interval, 2) Total sleep time: the number of minutes scored as sleep during the primary sleep period, 3) Wake time after sleep onset (WASO; the number of minutes scored as wake during the sleep period, 4) Regularity: the variability of each participant’s total sleep time calculated as the standard deviation of total sleep time for each individual, 5) Sleep midpoint: the halfway point between sleep onset and sleep offset; a proxy for circadian timing, and 6) 24-hour total sleep time: total number of minutes in a 24-hour period scored as sleep, includes daytime naps.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical procedures were conducted using R Studio 1.1.463 (R Core Team, 2017). Unadjusted means and standard deviations of sleep and circadian variables were calculated, and group differences in age and gender were tested using multilevel regression and chi-square analyses, respectively. Seasonal changes in depressive symptoms measured by the SIGH-SAD were tested using a mixed-effects negative binomial model with the glmmTMB package (Brooks et al., 2017).

Aim 1: Seasonal sleep changes across diagnostic groups.

We fit three linear mixed-effects models (actigraphy, sleep diaries, PSQI) comparing sleep variables between diagnostic group (SAD vs. controls), season (winter vs. summer), and the group by season interaction adjusting for age and gender, with a random intercept. Sleep dependent variables included time in bed, total sleep time, 24-hour total sleep time, sleep midpoint, WASO, regularity, and sleepiness. Initial examination of the raw data indicated high frequencies of naps on both actigraphy and sleep diaries. Given that self-reported hypersomnolence on the SIGH-SAD includes daytime nap duration in addition to nightly total sleep time, we included 24-hour total sleep time as a separate analysis. Linear mixed-models account for both multiple nightly measures (actigraphy and diaries) and repeated seasonal assessments while retaining all available data. Models were fitted with the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2014) using restricted maximum likelihood (REML). We used Satterthwaite approximations from lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) to derive p-values and degrees of freedom as these approximations have shown to produce acceptable Type 1 error rates in previous simulations (Luke, 2017). To control for multiple comparisons, we used the adaptive Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Glickman et al., 2014; Benjamini and Hochberg, 2016; Stevens et al., 2017).

Aim 2: Explaining self-reported hypersomnia.

We examined which factors best account for self-reported winter hypersomnia (question A-6 of the SIGH-SAD). We first dichotomized A-6 into (1) no increase in sleep length and (2) at least an hour increase and compared it across diagnostic groups in winter. Multiple logistic regression included the following predictors: total sleep time, time in bed, age, gender, sleepiness, fatigue, circadian preference, actigraphic average nap duration, sleep midpoint, and depression severity measured by the total SIGH-SAD score excluding sleep and fatigue items. To separate the unique contributions of naps and total sleep time, 24-hour total sleep time was not included in this analysis. Models were examined for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIFs), which led us to analyze total sleep time and time in bed separately. Goodness of fit between the total sleep time and time in bed models was compared using a likelihood ratio test (Hu et al., 2011). McFadden’s pseudo R-squared was calculated to determine the improvement in model likelihood over the null model for each model (Hemmert et al., 2018). Both crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Aim 3: Agreement between self-report and actigraphic measures of total sleep time.

We used a Bland-Altman analysis to assess the degree of measurement agreement between total sleep time assessed via actigraphy compared to self-reported total sleep time from sleep diaries and the PSQI in SAD (Bland and Altman, 1986). Horizontal lines were drawn at the mean difference and at the limits of agreement, defined as the mean difference ±1.96 times the standard deviation of the differences (Bland and Altman, 1986).

Results

Sample Description

Our total sample comprised 64 individuals with SAD and 80 nonseasonal, never-depressed controls with no history of depression (N=144). Some participants attended both summer and winter assessments, yielding 92 SAD and 110 control assessments for 202 total assessments across 144 unique participants (Table 1). Age did not differ between groups (F1,122.39= .004, p=.947), but there were significantly more women in the SAD group than in the control group (χ2 = 4.4, p=.035). Age and gender were included as covariates in all analyses below. Consistent with diagnostic criteria, depression severity measured by the SIGH-SAD was significantly higher in the SAD group during the winter (b=.94 SE=.23; p<.001) compared to controls. On average, participants completed 10.3 nights of actigraphic monitoring and 9.2 nights of sleep diaries. Groups did not differ on number of actigraphic nights (F1,141.41=3.3, p=.073) or number of sleep diary assessments (F1,122.39=.004, p=.947).

Table 1.

Demographic and sleep characteristics of the sample presented as Mean (Standard Deviation) except where indicated.

| SAD |

Control |

Both Groups & Seasons | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | Total | Summer | Winter | Total | ||

|

|

|||||||

| N (Assessments) a | 38 | 50 | 64 (88) | 50 | 59 | 80 (109) | 144 (202) |

| Age | 39.4 (12.8) | 38.9 (12.6) | 39.1(12.6) | 38.6 (14.0) | 37.7 (13.2) | 38.1(13.5) | 38.6(13.1) |

| Gender n(%) | 32 (84%) | 45 (90%) | 55 (86%) | 33 (66%) | 44 (75%) | 57(71%) | 112(78%) |

| Actigraphy nights | 9.8 (3.1) | 11.5 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.4) | 9.5 (3.4) | 9.9 (3.1) | 9.7 (3.2) | 10.3(3.8) |

| Sleep Diary nights | 8.7 (2.7) | 9.5 (3.6) | 9.2 (3.2) | 8.6 (3.1) | 9.8 (3.1) | 9.2 (3.1) | 9.2 (3.2) |

| Naps b (min) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 1.9 (5.7) | 4.9 (8.3) | 3.7 (7.4) | .5 (1.7) | 2.6 (6.3) | 1.6 (4.9) | 2.6 (6.2) |

| Diary | 0 (0) | 13.9(22.1) | 8.1 (18.1) | 0 (0) | 6.5 (10.8) | 3.6 (8.6) | 5.7 (14.0) |

| Time in bed (hrs) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 8.2 (1.7) | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.3 (1.7) | 7.8 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.7) | 7.9 (1.7) | 8.1 (1.7) |

| Diary | 8.3 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.7) | 8.0 (1.8) | 7.8 (1.5) | 7.9 (1.6) | 8.1 (1.7) |

| PSQI c | 8.3 (1.5) | 8.4 (1.8) | 8.3 (1.6) | 7.6 (1.4) | 7.7 (1.4) | 7.7 (1.4) | 7.9 (1.5) |

| Total sleep time (hrs) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 7.1 (1.6) | 7.2 (1.6) | 7.2 (1.6) | 6.8 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.6) |

| Diary | 7.1 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.6) | 7.2 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.4) | 6.9 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.6) |

| PSQI c | 7.1 (1.4) | 7.4 (1.9) | 7.3 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.4) |

| WASO (min) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 48.2 (36.6) | 46.5 (30.8) | 47.2 (33.3) | 43.8 (25.1) | 43.0 (28.2) | 43.3 (26.8) | 45.1 (30.0) |

| Diary | 18.2 (26.3) | 20.5 (32.3) | 19.6 (30.1) | 8.9 (16.9) | 10.5 (22.1) | 9.8 (20.0) | 14.1 (25.4) |

| Efficiency (%) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 86.5 (8.5) | 87.1 (6.5) | 86.9 (7.3) | 87.2 (6.2) | 87.8 (6.2) | 87.5 (6.2) | 87.2 (6.77) |

| Diary | 85.6 (10.2) | 86.6 (8.9) | 86.2 (9.4) | 87.7 (8.5) | 87.6 (8.4) | 87.7 (8.4) | 87.0 (8.9) |

| PSQI c | 84.1 (13.5) | 85.0 (12.3) | 84.6 (12.8) | 92.2 (8.3) | 91.9 (8.3) | 92.1 (8.3) | 88.8 (11.1) |

| Midpoint (hh:mm) | |||||||

| Actigraphy | 3:43 (1.5) | 3:20 (1.5) | 3:29 (1.5) | 3:51 (1.7) | 3:34 (1.8) | 3:41 (1.7) | 3:36 (1.6) |

| Diary | 3:22 (1.3) | 3:12 (1.3) | 3:16 (1.3) | 3:39 (1.5) | 3:37 (1.5) | 3:38 (1.5) | 3:28 (1.4) |

| PSQI c | 3:07 (1.2) | 3:01 (1.3) | 3:03 (1.3) | 3:08 (1.2) | 2:49 (1.2) | 2:58 (1.2) | 2:59 (1.2) |

| Regularity (min) | |||||||

| Actigraphy (SD) | 80.7 (27.4) | 74.9 (29.9) | 77.1 (29.1) | 68.5 (26.8) | 68.1 (25.9) | 68.3 (26.3) | 72.3 (28.2) |

| Diary (SD) | 68.3 (41.0) | 68.4 (32.7) | 68.4 (36.2) | 68.1 (34.0) | 58.2 (29.2) | 62.7 (31.7) | 65.4 (33.9) |

Not all participants came for both a summer and winter visit. ‘Assessments’ represents the total number of visits in the study.

Weighted average nap duration

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inde

Aim 1: Seasonal sleep changes across diagnostic groups

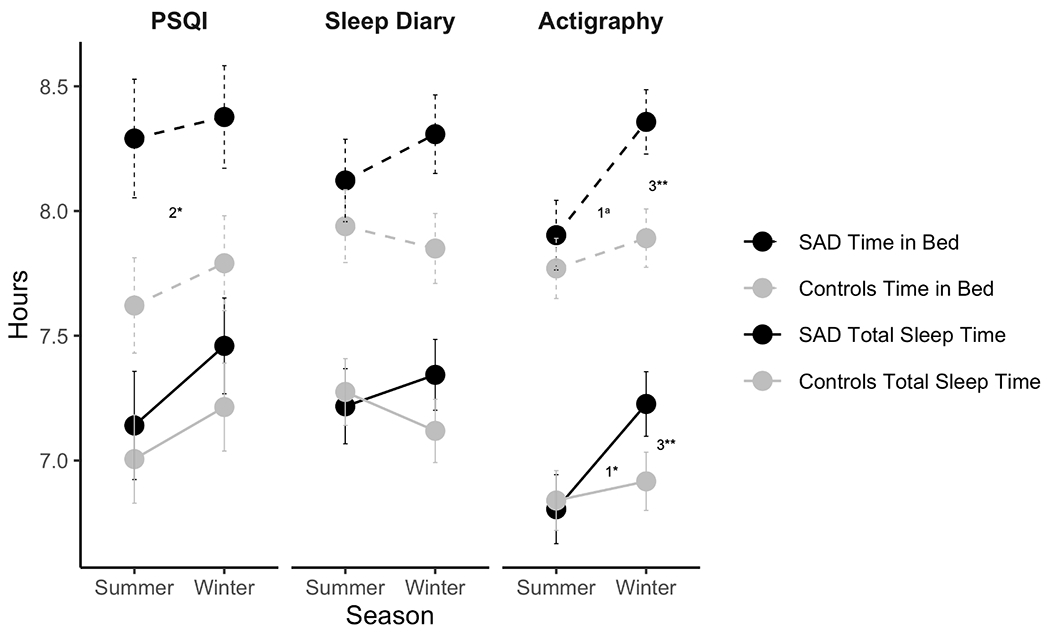

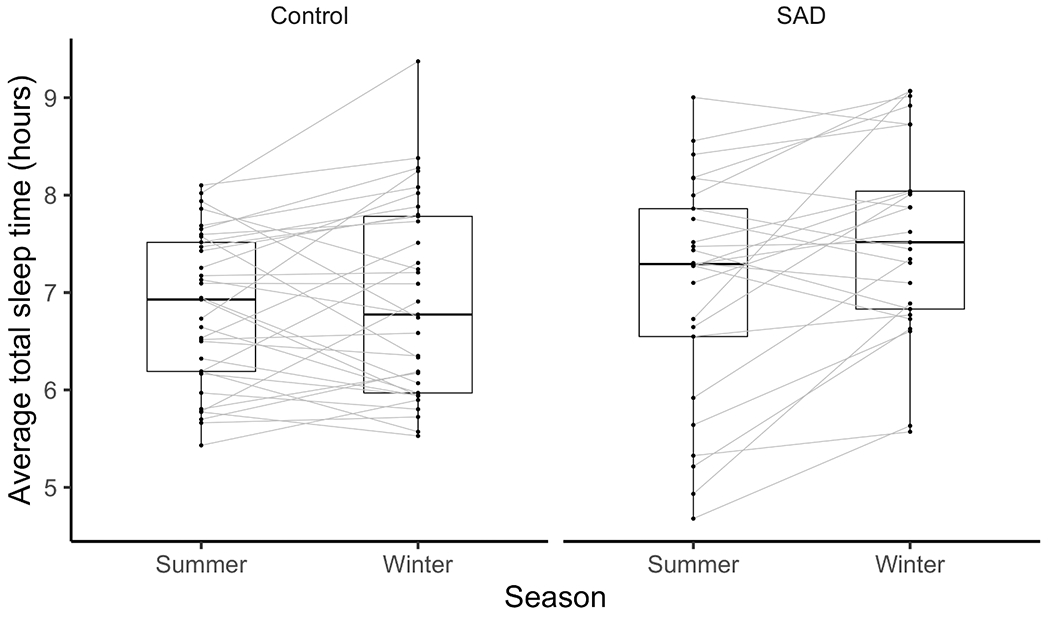

Unadjusted means and standard deviations of sleep and circadian variables from actigraphy, sleep diaries, and the PSQI are shown in Table 1. Results of the mixed-effects models are shown in Table 2. Of the 202 individual actigraphic assessments across seasons, 192 participants (95%) had complete PSQI data and 158 participants (78%) completed sleep diaries for at least 5 nights. Figure 1A provides a visual depiction of both time in bed and total sleep time for actigraphy, sleep diaries, and the PSQI across groups and seasons. Figure 1B depicts seasonal changes in total sleep time.

Table 2.

Mixed-effects models comparing measures of sleep and rhythms by diagnostic groups and seasons. Estimates represent unstandardized beta coefficients.

| Total sleep time | 24-hour Total sleep time | Time in Bed | Midpoint | Efficiency | WASO | Regularity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | ||

| Actigraphy | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 402.2 (17.4) | [368.4, 435.9] | 403.5 (17.6) | [369.3, 437.7] | 473.3 (17.2) | [439.9, 506.9] | 5.5 (.3) | [4.9, 6.1] | 85.9 (1.3) | [83.4, 88.4] | 50.4 (5.9) | [38.9, 61.9] | 83.7 (8.6) | [67.1, 100.4] | |

| Group | 6.8 (10.2) | [−13.1, 26.7] | 8.3 (10.4) | [−11.9, 28.4] | 15.3 (10.1) | [−4.4, 34.9] | .1 (.2) | [−.2, .5] | −1.4 (.9) | [−3.1, .3] | 5.2 (3.5) | [−1.6, 11.9] | 11.2 (4.9) a | [1.5, 20.9] | |

| Season | 13.9 (4.5) | [5.2, 22.7] | 16.6 (4.5) | [7.8, 25.5] | 16.5 (4.9) | [6.7, 26.2] | −.2 (.1) | [−.3, −.1] | .1 (.3) | [−.4, .7] | 1.4 (1.3) | [−1.3, 3.9] | 5.1 (3.5) | [−1.9, 11.8] | |

| Gender | 22.7 (12.3) | [−1.1, 46.6] | 24.6 (12.4) | [.5, 48.7] | 12.3 (12.2) | [−11.3, 35.9] | 1.0 (.2) | [−1.4, −.6] | −2.5 (1.0) | [−4.5, −.5] | −7.4 (4.2) | [−15.6, .7] | −6.2 (6.0) | [−17.9, 5.4] | |

| Age | −.1 (.4) | [−0.8, 0.7] | −.1 (.4) | [−.8, .7] | −.1 (.4) | [−.8, .6] | −.03 (.01) | [−.04, −.01] | .01 (.03) | [−.04, .08] | .002 (.01) | [−.2, .2] | −.2 (.2) | [−.6, .2] | |

| Group* Season | 22.7 (8.9) | [5.1, 40.1] | 25.4 (9.0) | [7.5, 42.9] | 23.0 (9.9) a | [3.4, 42.3] | |||||||||

| Sleep Diaries | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 432.7 (21.1) | [391.7, 473.7] | 438.1 (21.8) | [395.8, 480.4] | 493.2 (23.7) | [447.3, 539.1] | 5.2 (.4) | [4.5, 5.9] | 87.9 (1.9) | [84.3, 91.7] | 9.3 (4.5) | [.6, 18.1] | 69.5 (11.3) | [47.6, 91.4] | |

| Group | 11.3 (11.8) | [−11.6, 34.3] | 12.1 (12.2) | [−11.6, 35.8] | 20.4 (13.3) | [−5.4, 46.2] | .1 (.02) | [−.3, .4] | −1.5 (1.1) | [−3.5, .6] | 8.5 (2.5) | [3.7, 13.3] | 4.2 (6.3) | [−8.1, 16.4] | |

| Season | 1.6 (5.5) | [−9.4, 12.4] | 15.4 (5.8) | [3.9, 26.6] | 1.6 (5.7) | [−9.6, 12.7] | −.03 (.1) | [−.2, .1] | .2 (.5) | [−.8, 1.3] | 2.4 (1.6) | [−.6, 5.5] | −2.7 (4.6) | [−12.5, 6.3] | |

| Gender | 19.8 (15.2) | [−9.6, 49.2] | 22.2 (15.6) | [−8.1, 52.5] | 16.8 (17.1) | [−16.3, 49.9] | −.1 (.2) | [−1.5, −.5] | 1.2 (1.4) | [−1.5, 3.8] | .6 (3.2) | [−5.5, 6.8] | −6.4 (8.1) | [−22.2, 9.4] | |

| Age | −.6 (.4) | [−1.4, .2] | −.6 (.5) | [−1.5, .2] | −.5 (.5) | [−1.4, .5] | −.02 (.01) | [−.03, −.01] | −.1 (.04) | [−.1, .03] | .1 (.1) | [−.1, .3] | −.03 (.2) | [−.5, .5] | |

| Group* Season | 27.8 (11.6) | [5.2, 50.4] | .3 (.2) a | [−.6, −.02] | |||||||||||

| PSQI | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 457.5 (25.5) | [408.0, 507.0] | 485.3 (26.1) | [434.6, 535.9] | 4.4 (.3) | [3.8, 5.1] | 93.2 (3.5) | [86.5, 99.9] | |||||||

| Group | 8.0 (14.6) | [−20.3, 26.4] | 36.0 (14.9) * | [7.0, 64.9] | .2 (.2) | [−.2, .6] | −5.5 (1.9 | [−9.3, −1.6] | |||||||

| Season | 15.0 (8.9) | [−2.9, 32.5] | 9.8 (10.9) | [−12.3, 30.9] | −.2 (.1) | [−.5, .02] | .8 (1.7) | [−2.6, 4.2] | |||||||

| Gender | 3.4 (17.7) | [−30.9, 37.8] | 15.7 (18.1) | [−19.5, 50.9] | −.4 (.2) | [−.9, .01] | −2.1 (2.4) | [−6.8, 2.6] | |||||||

| Age | −.7 (.5) | [−1.8, .3] | −.5 (.6) | [−1.5, .6] | −.03 (.01) | [−.04, −.01] | −.02 (.07) | [−.2, .1] d | |||||||

bold = p<.05;

Not significant BH correction.

Figure 1.

A) Conditional means for total sleep time and time in bed across seasons for both diagnostic groups to account for repeated nights and seasons of participants. Error bars represent standard errors. There was a significant group by season interaction for actigraphic total sleep time (b=23 min; p=.011). The group by season interaction for actigraphic time in bed did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons (b=23 min; p=.020). In both seasons, individuals with SAD reported spending 36 min longer in bed on the PSQI (p=.017). 1Group by season interaction; 2Group main effect; 3Season main effect

Note: * = p < .05; ** = p <.01. aNot significantly different after adjusting for BH. B) Spaghetti plots showing individual change in mean actigraphic total sleep times for participants with both winter and summer assessments.

There was a significant interaction for actigraphic total sleep time between diagnostic group (SAD vs. controls) and season (winter vs. summer). Individuals with SAD slept 23 min longer during the winter than in the summer, with no seasonal effect for controls (p=.011). A similar interaction was shown using both actigraphy and sleep diaries predicting 24-hour total sleep time. Actigraphic total sleep time during a 24-hour period was 25 min longer on actigraphy (p=.005) and 27 min longer on sleep diaries (p=.016) in the SAD group in winter than in summer with no seasonal effect in controls. The group by season interaction for actigraphic time in bed did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons (b=23 min; p=.020). However, individuals with SAD reported spending 36 min longer than controls in bed on the PSQI when data were collapsed across seasons (i.e., main effect of group; p=.017).

When examining other dimensions of sleep, both groups had earlier sleep midpoints on actigraphy in winter compared to summer by an average of 11 min (p=.004). The group by season interaction for sleep diary midpoint did not withstand correction for multiple comparisons (b=−.29; p=.035). Further, individuals with SAD reported 9 min more WASO on sleep diaries than controls in both seasons (p<.001). Individuals with SAD had more irregularity in their night-to-night sleep length; however, this finding did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (b=12 min; p=.026). Individuals with SAD had global PSQI scores (M=7.3; SD=3.5) above the clinical cut-off of 5 (Buysse et al., 1989), and higher than controls (M=3.2, SD=2.2). PSQI-assessed global sleep quality was 3.8 points higher in individuals with SAD compared to controls when data were collapsed across seasons (i.e., main effect of group; p<.001). Similarly, individuals with SAD reported greater daytime sleepiness (M=8.9; SD=4.4) than controls (M=5.6; SD=3.8; i.e., main effect of group; b=2.6; p<.001), although this fell within the normal range of daytime sleepiness (Johns, 1991).

Aim 2: Explaining self-reported hypersomnia

Consistent with previous reports, participants with SAD differed from controls on clinician-rated interviews of self-reported presence of winter hypersomnnia (question A6 of the SIGH-SAD) endorsing hypersomnia more frequently than controls (b=2.04; SE=.499; p<.001). Individuals with SAD reported sleeping an average of 1.2 hours longer than usual (SD=1.35 hours), while the control group reported sleeping an average of .23 hours more than usual (SD=.69 hours). There were 48 SAD participants (86%) with complete winter actigraphy, sleepiness, and fatigue data available for this analysis and over half (26 participants) endorsed hypersomnolence.

In the total sleep time model, age (AOR=1.13, p=.042), total sleep time (AOR=4.11, p=.015), naps (AOR=1.13, p=.020), sleep midpoint (AOR=4.35, p=.033), and fatigue (AOR=1.56, p=.008) all significantly predicted endorsement of self-reported winter hypersomnia. In the time in bed model, age (AOR=1.12, p=.03714), time in bed (AOR=3.50, p=.026), sleep midpoint (AOR=3.96, p=.035), naps (AOR=1.12, p=.026), and fatigue (AOR=1.50, p=.008) all significantly predicted endorsement of self-reported winter hypersomnia. Fatigue, later sleep midpoints and longer actigraphic total sleep time, time in bed and naps were all statistically associated with self-reported winter hypersomnia in SAD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of self-reported hypersomnolence during the winter months in SAD.

| Total sleep time |

Time in bed |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b (SE) | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | b (SE) | Crude OR [95% CI] | Adjusted OR [95% CI] |

| Age | .12 (.05) * | 1.04 [.99, 1.09] | 1.13 [1.02, 1.26] | .12 (.05) * | 1.04 [.99, 1.09] | 1.12 [1.01, 1.26] |

| Time in bed | 1.25 (.56) * | 2.38 [1.15, 4.96] | 3.50 [1.17, 10.54] | |||

| Total sleep time | 1.41 (.58) * | 2.67 [1.30, 5.50] | 4.11 [1.31, 12.90] | |||

| WASO | .01 (.02) | .99 [.97, 1.02] | 1.01 [.97, 1.05] | −.02 (.02) | 1.0 [.98, 1.02] | .98 [.94, 1.03] |

| Naps | .12 (.05) * | 1.07 [1.07, 1.16] | 1.13 [1.02, 1.25] | .11 (.05) * | 1.07 [1.0, 1.16] | 1.12 [1.01, 1.23] |

| Midpoint | 1.47 (.68) * | 1.63 [.89, 3.0] | 4.35 [1.13, 16.61] | 1.38 (.65) * | 1.63 [.89, 3.0] | 3.96 [1.1, 14.25] |

| a ESS total | −.01 (.09) | .95 [.83, 1.08] | .99 [.80, 1.23] | −.02 (.11) | .95 [.83, 1.08] | .98 [.80, 1.20] |

| b CFM total | .45 (.17) ** | 1.11 [.98, 1.26] | 1.56 [1.13, 2.17] | .41 (.15) ** | 1.11 [.98, 1.26] | 1.5 [1.11, 2.03] |

| c SIGH-SAD total | −.07 (.06) | 1.03 [.95, 1.11] | .93 [.83, 1.06] | −.05 (.06) | 1.03 [.95, 1.11] | .95 [.84, 1.07] |

| d CSM total | −.01 (.07) | 1.00 [.95, 1.11] | .99 [.86, 1.15] | .01 (.07) | 1.00 [.95, 1.06] | 1.00 [.87, 1.15] |

| McFadden’s pseudo R2 | .46 | .43 | ||||

| % endorsing sleeping more than usual | 54% | 54% | ||||

Epworth Sleepiness Scale;

Chalder Fatigue Measure;

Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression—Seasonal Affective Disorder Version total score;

Composite Scale of Morningness;

Note:

= p < .05;

BH correction applied

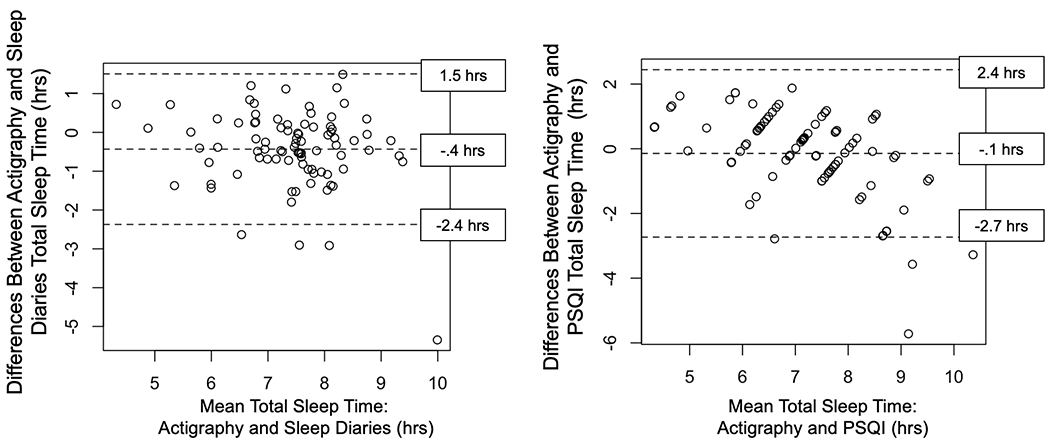

Aim 3: Self-report vs actigraphy measurement agreement in SAD

Among participants with SAD, differences in agreement between actigraphy total sleep time and sleep diary or PSQI total sleep time are depicted with Bland-Altman plots (Figure 2). Mean differences were calculated by subtracting either sleep diary or PSQI reported total sleep time from actigraphic total sleep time. Positive mean differences depict greater actigraphic total sleep time relative to sleep diaries or PSQI reports. Sleep diary total sleep time was greater than actigraphy by 24 minutes with limits of agreement varying by ± 1.95 hours. PSQI total sleep time was greater than actigraphy by 6 minutes with limits of agreement ranging from ± 2.5 hours. However, individuals with longer average total sleep time on both actigraphy and the PSQI reported longer total sleep times on the PSQI compared to actigraphy whereas individuals with shorter average total sleep time on both actigraphy and the PSQI reported shorter total sleep times on the PSQI compared to actigraphy. Both self-report measures yielded higher total sleep time compared to actigraphy, as shown by a higher prevalence of negative mean differences in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plots comparing actigraphy and sleep diaries (left panel) and comparing actigraphy and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; right panel) for total sleep time in SAD. The middle-dashed line indicates the means of the differences (in hours) between the 2 methods. The dashed lines above and below those means indicate the 95% limits of agreement (1.96 × the standard deviation of the mean difference). Positive values indicate greater total sleep time measured by actigraphy.

Discussion

Hypersomnolence has largely been accepted as the prototypical sleep disturbance in SAD; however, the present findings provide mixed evidence for hypersomnolence which depends, in part, on the assessment method. During winter depressive episodes, participants with SAD reported sleeping 1.2 hours longer than in summer based on the SIGH-SAD clinical interview and had a seasonal increase in total sleep time that was not evident in controls when measured using actigraphy. Yet, participants with SAD did not report longer winter sleep times on either prospective sleep diaries or retrospective self-reports (PSQI). Despite a seasonal increase in actigraphic sleep, the mean actigraphy-based total sleep time during the winter in SAD (7.2 hours) was well below the clinical cut-off for both the duration criterion (>9-10 hours; American Psychological Association, 2013) and daytime sleepiness criterion of hypersomnolence (>11; Johns, 1991), suggesting that the majority of participants with SAD do not exhibit a clinically significant degree of hypersomnolence. Further, individuals reporting a winter increase of sleep on the SIGH-SAD averaged between 6-9 hours on actigraphy, underscoring the need for multiple measures of sleep duration when assessing hypersomnia in mood disorders.

Assessing self-reported winter hypersomnolence in SAD with daily diaries and/or actigraphy would be critical for informing treatment choice (Kaplan and Harvey, 2009). While self-reported winter hypersomnia was not correlated with depression symptom severity, it was associated with increased actigraphic time in bed, napping, and fatigue. These factors may reflect a desire for more restful sleep, anhedonia, or behavioral inactivation. Given the low rates of clinical hypersomnia in this sample, and greater total sleep times, naps, and sleep fragmentation during the winter, individuals with SAD reporting hypersomnia should be further assessed for napping, sleep fragmentation, and fatigue rather than exclusively assessed on nightly total sleep time. Potential underlying comorbidities, such as restless leg syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, and/or sleep apnea, should be considered to disentangle greater winter total sleep times, naps, and sleep fragmentation in SAD. Further, the longest sleepers with SAD reported even greater total sleep time on the PSQI relative to their actigraphy total sleep time whereas the shortest sleepers with SAD reported sleeping even less on the PSQI compared to their actigraphy total sleep time. This biphasic relationship resembles sleep discrepancies commonly seen in insomnia (Harvey and Tang, 2012), and is extended here to longer sleepers. For the average SAD participant, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or behavioral activation interventions may be more helpful than hypersomnia-focused interventions. A particular focus may be placed on limiting time in bed, which could lead to more consolidated sleep by increasing homeostatic sleep pressure (Maurer et al., 2018). We recommend using multiple measures of sleep duration for those reporting hypersomnia to inform treatment choice while weighing participant burden against retrospective recall bias.

While later winter sleep midpoints were associated with endorsing hypersomnia, both groups had earlier sleep midpoints during the winter months suggesting that neither late nor early sleep timing is the predominant phenotype in SAD during winter depressive episodes. While the phase-shift hypothesis presumes a winter phase-delay in circadian rhythms that are out of sync with the sleep/wake cycle (Lewy et al., 1988), this is not true for all participants (Eastman et al., 1993; Burgess et al., 2004). This heterogeneity of sleep and circadian timing in SAD could explain non-responders to morning bright light therapy – the current gold standard treatment of SAD (Burgess et al., 2004; Lewy et al., 2006; Wescott et al., 2020). However, it is still possible that markers of circadian phase such as dim-light melatonin release onset (DLMO) may be delayed relative to the sleep/wake cycle in winter in the current sample.

While our group-means analytic approach was not designed to elucidate subgroups, our findings indicated significant heterogeneity of winter sleep in SAD. Almost half (43%) of participants with SAD did not endorse self-reported winter hypersomnia on the SIGH-SAD and the majority (68%) did not have any winter naps. Means-focused analyses obscure the range of presentations or subgroups (Wescott et al., 2020). Efforts to identify and characterize sleep subgroups associated with recurrence and/or symptom severity are needed to guide sleep-focused interventions in SAD.

Strengths and Limitations

This study benefitted from the use of multiple metrics of sleep assessment during both winter depressive episodes and summer remission, and is the largest actigraphic study in SAD compared to nonseasonal, never-depressed controls. One limitation is the use of a single item assessment of self-reported hypersomnia, although this was done intentionally as it is the most common measurement of sleep duration in SAD. Incorporating a more granular assessment of hypersomnolence, including objective measures of daytime sleepiness such as the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT; Arand et al., 2005), would be informative. Lack of objective assessments of comorbid sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and narcolepsy was another limitation of this work. Additionally, actigraphy-based sleep midpoint is at best a proxy for circadian timing and also reflects the behavioral sleep/wake cycle, thus limiting our ability to assess circadian misalignment. Future assessments should include physiological measures of circadian timing, such as DLMO or core body temperature nadir.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite a winter increase in total sleep time and elevated daytime sleepiness, the majority of participants with SAD do not sleep longer than 9 hours and did not endorse abnormal levels of daytime sleepiness making hypersomnolence a poor general characterization of SAD. Sleep-targeted interventions have been effective in nonseasonal depression, (Manber et al., 2008) often focusing on insomnia. Future research directions include measuring targets of behavioral treatments such as Transdiagnostic Intervention for Sleep and Circadian Dysfunction (TranS-C; Harvey et al., 2016), and/or CBT-I, and prospective measurement of sleep during spontaneous remission to predict subsequent depression recurrence and severity. We recommend following up self-reports of hypersomnolence with multimodal assessments of sleep and rest-activity-rhythms to accurately identify treatment targets.

Disclosure Statement.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (R03MH096119-01A1; R01MH103313-02; T32 HL082610).

Footnotes

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- American Psychological Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Rosen LN, Mendelson WB, Jacobsen FM, Skwerer RG, Joseph-Vanderpool JR, Duncan CC, Wehr TA, Rosenthal NE (1994) Sleep in fall/winter seasonal affective disorder: Effects of light and changing seasons. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 38, 323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D Arand, Bonnet M, Hurwitz T, Mitler M, Rosa R, Sangal RB (2005) The Clinical Use of the MSLT and MWT. Sleep 28, 123–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2014) Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. arXiv:1406.5823 [stat]. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (2016) On the Adaptive Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing With Independent Statistics: SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet (London, England) 1, 307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond T, Wooten V (1996) The etiology and management of insomnia. Virginia medical quarterly: VMQ 123, 254–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P (1996) Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biological Psychiatry 39, 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ME, Kristensen K, Benthem KJ van, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, Skaug HJ, Mächler M, Bolker BM (2017) glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. The R Journal 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HJ, Fogg LF, Young MA, Eastman CI (2004) Bright Light Therapy for Winter Depression—Is Phase Advancing Beneficial? Chronobiology International 21, 759–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessely S, Wright D, Wallace EP (1993) Development of a fatigue scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 37, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman CI, Gallo LC, Lahmeyer HW, Fogg LF (1993) The circadian rhythm of temperature during light treatment for winter depression. Biological Psychiatry 34, 210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB (2015) Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID). In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology , pp 1–6 American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- ME Glickman, SR Rao, MR Schultz (2014) False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67, 850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG (2011) Sleep and Circadian Functioning: Critical Mechanisms in the Mood Disorders? Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 7, 297–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Hein K, Dong L, Smith FL, Lisman M, Yu S, Rabe-Hesketh S, Buysse DJ (2016) A transdiagnostic sleep and circadian treatment to improve severe mental illness outcomes in a community setting: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, NKY Tang (2012) (Mis)perception of sleep in insomnia: A puzzle and a resolution. US: American Psychological Association Psychological Bulletin 138, 77–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmert GAJ, Schons LM, Wieseke J, Schimmelpfennig H (2018) Log-likelihood-based Pseudo-R2 in Logistic Regression: Deriving Sample-sensitive Benchmarks. Sociological Methods & Research 47, 507–531. [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Pavlicova M, Nunes EV (2011) Zero-inflated and Hurdle Models of Count Data with Extra Zeros: Examples from an HIV-Risk Reduction Intervention Trial. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse 37, 367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MW (1991) A New Method for Measuring Daytime Sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 14, 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KA, Gruber J, Eidelman P, Talbot LS, Harvey AG (2011) Hypersomnia in Inter-Episode Bipolar Disorder: Does it Have Prognostic Significance? Journal of affective disorders 132, 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan KA, Harvey AG (2009) Hypersomnia across mood disorders: A review and synthesis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 13, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB (2017) lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software 82. [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Lefler BJ, Emens JS, Bauer VK (2006) The circadian basis of winter depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 7414–7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Sack RL, Singer CM, Whate DM, Hoban TM (1988) Winter Depression and the Phase-Shift Hypothesis for Bright Light’s Therapeutic Effects: History, Theory, and Experimental Evidence. Journal of Biological Rhythms 3, 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke SG (2017) Evaluating significance in linear mixed-effects models in R. Behavior Research Methods 49, 1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson A (1996) Validation of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ). Journal of Affective Disorders 40, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, Pedro-Salcedo MGS, Kuo TF, Kalista T (2008) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Enhances Depression Outcome in Patients with Comorbid Major Depressive Disorder and Insomnia. Sleep 31, 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer LF, Espie CA, Kyle SD (2018) How does sleep restriction therapy for insomnia work? A systematic review of mechanistic evidence and the introduction of the Triple-R model. Sleep Medicine Reviews 42, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale V, Alzani A (2001) Additional validity evidence for the composite scale of morningness. Personality and Individual Differences 30, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Plante DT, Finn LA, Hagen EW, Mignot E, Peppard PE (2017) Longitudinal associations of hypersomnolence and depression in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Journal of Affective Disorders 207, 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roecklein KA, Carney CE, Wong PM, Steiner JL, Hasler BP, Franzen PL (2013) The role of beliefs and attitudes about sleep in seasonal and nonseasonal mood disorder, and nondepressed controls. Journal of Affective Disorders 150, 466–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan KJ, Rough JN, Evans M, Ho S-Y, Meyerhoff J, Roberts LM, Vacek PM (2016) A Protocol for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: Item Scoring Rules, Rater Training, and Outcome Accuracy with Data on its Application in a Clinical Trial. Journal of affective disorders 200, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal NE (1984) Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Description of the Syndrome and Preliminary Findings With Light Therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 41, 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A (2011) The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: An update. Sleep Medicine Reviews 15, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CM, Devins GM, Feldman B, Levitt AJ (1994) Is hypersomnolence a feature of seasonal affective disorder? Journal of Psychosomatic Research 38, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagula SF, DuPont CM, Miller MA, Krafty RT, Hasler BP, Franzen PL, Roecklein KA (2018) Rest-activity rhythms characteristics and seasonal changes in seasonal affective disorder. Chronobiology International 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CS, Reilly C, Midkiff K (1989) Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. The Journal of Applied Psychology 74, 728–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JR, Masud AA, Suyundikov A (2017) A comparison of multiple testing adjustment methods with block-correlation positively-dependent tests. Public Library of Science PLOS ONE 12, e0176124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman M, Terman JS, Rafferty B (1990) Experimental design and measures of success in the treatment of winter depression by bright light. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 26, 505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wescott DL, Soehner AM, Roecklein KA (2020) Sleep in seasonal affective disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology 34, 7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JBW, Link M, Rosenthal NE, Amira L, Terman M (1992) Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—Seasonal Affective Disorder Version (SIGH-SAD). New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D, Pjrek E, Praschak-Rieder N, Willeit M, Pezawas L, Konstantinidis A, Stastny J, Kasper S (2005) Actigraphy in Patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder and Healthy Control Subjects Treated with Light Therapy. Biological Psychiatry 58, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler D, Willeit M, Praschak-Rieder N, Lucht MJ, Hilger E, Konstantinidis A, Stastny J, Thierry N, Pjrek E, Neumeister A, Möller HJ, Kasper S (2002) Changes of clinical pattern in seasonal affective disorder (SAD) over time in a German-speaking sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 252, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB, Posternak MA, Friedman M, Boerescu D, Attiullah N (2005) Differences between minimally depressed patients who do and do not consider themselves to be in remission. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66, 1134–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]