Abstract

Study Objectives:

The aim was to describe sleep habits and epidemiology of the most common sleep disorders in Italian children and adolescents.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study in which parents of typically developing children and adolescents (1–18 years) completed an online survey available in Italy, gathering retrospective information focusing on sleep habits and disorders.

Results:

Respondents were 4,321 typically developing individuals (48.6% females). Most of our sample did not meet the age-specific National Sleep Foundation recommendations for total sleep duration (31.9% of toddlers, 71.5% of preschoolers, 61.6% of school-age children, and 41.3% of adolescents). Napping was described in 92.6% of toddlers and in 35.2% of preschoolers. Regarding geographical differences, children and adolescents of northern Italy showed more frequent earlier bedtimes and rise times than their peers of central and southern Italy. The most frequently reported sleep disorder in our sample was restless sleep (35.6%), followed by difficulties falling asleep (16.8%), > 2 night awakenings (9.9%), and bruxism (9.6%). Data also suggest that longer screen time is associated with later bedtimes on weekdays in all age groups.

Conclusions:

The current study shows that Italian children are at risk of sleep disorders, particularly insufficient sleep, restless sleep, and difficulty falling asleep. The study also provides normative sleep data by age group in a large cohort of typically developing Italian children, emphasizing the importance of the developmentally, ecologically, and culturally based evaluation of sleep habits and disorders.

Citation:

Breda M, Belli A, Esposito D, et al. Sleep habits and sleep disorders in Italian children and adolescents: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19(4):659–672

Keywords: sleep habits, sleep disorders, infant, preschoolers, children, adolescents

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Knowing the sleep habits of our children is important considering the role of sleep for brain development; negative effects of sleep disturbances have been demonstrated on memory, attention, executive functions, language, and learning. While some data are available on the epidemiology of sleep habits, very few studies have analyzed the epidemiology of sleep disorders through a standardized questionnaire.

Study Impact: The current study shows that Italian children are at risk of sleep disorders, particularly insufficient sleep, restless sleep, and difficulty falling asleep. The study also provides normative sleep data by age group in a large cohort of typically developing Italian children, emphasizing the importance of the developmentally, ecologically, and culturally based evaluation of sleep habits and disorders.

INTRODUCTION

The crucial role of sleep for brain development in infants and children is widely acknowledged, and sleep problems are a growing public health concern.1,2 Indeed, most authors agree that good sleep quality during childhood is essential for the correct development of neurocognitive functioning.3,4 The impact of sleep is not homogeneous across ages, brain function, and type of sleep problem.1 However, negative effects of sleep disturbances have been demonstrated on memory, attention, executive functions, language, and learning5–7 Many correlation studies showed a connection between sleep, daytime sleepiness, and school performance.8–10 Sleep also plays a critical role in emotional regulation and in “neurobehavioral functioning” as well.11 Accordingly, poor sleep has been found to influence emotion recognition and expression12,13 and irritability and emotional volatility.14 Several bidirectional associations between psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence and sleep behaviors have also been described.15

The National Sleep Foundation in 2015 recommended a sleep duration of 14–17 hours (h)/day for newborns, 12–15 h for infants (aged 4–11 months), 11–14 h for toddlers (aged 1–2 years), 10–13 h for preschoolers (aged 3–5 years), 9–11 h for school-aged children (aged 6–13 years), and 8–10 h for teenagers (aged 14–18 years).16 Similar recommendations were made by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.17

However, in daily life, children rarely comply with these recommendations. As several US national surveys showed, approximately 29% of infants, 21% of toddlers, 22% of preschoolers and a percentage ranging from 17% up to 36% of school-aged children sleep fewer hours than recommended.18,19 This relative lack of sleep becomes even more relevant in adolescents since 32–45% of them do not get the optimal amount of night sleep,19,20 with up to 72.7% reporting, on average, less than 8 h of sleep on school nights.21 Among the factors affecting sleep across developmental periods is screen time, considering the unquestionable rise of the digital environment in the last decades.

Medical societies, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization, have recommended that children aged 0–1 years should not be exposed to media use and that children 2–5 years of age should not exceed 1–2 h of screen time per day.22,23 However, children worldwide do not follow these recommendations in everyday life, using screens for longer times.24

With regard to the Italian pediatric population, no study included epidemiologic data on sleep habits together with the prevalence of sleep disorders along the developmental period. Several authors have investigated sleep habits in preschool-aged children, schoolchildren, and adolescents,25–30 but only a few studies have focused on early infancy.31–33 However, many epidemiologic studies date back to more than a decade25,27,31; for this reason, they do not consider the recent impact of technology and screen use on pediatric sleep. On the other hand, some authors focused on sleep disorders34–36 while others focused on media use alone.28,30,32,33

With regard to sleep disorders, insomnia—defined as a persistent difficulty in falling or remaining asleep—is the most common sleep disorder in the pediatric age.37 However, a variety of sleep disorders may affect children and adolescents, such as sleep breathing disorders, sleep-related movement disorders, parasomnias, and excessive daytime sleepiness.38

According to the authors’ knowledge, little comprehensive work has been dedicated to analyze both physiological and disordered sleep in pediatric population–based studies.39 Therefore, given the lack of comprehensive studies in Italian children and adolescents, the aim of this study was to offer an up-to-date description of sleeping habits in these individuals, together with the current epidemiology of the most common sleep disorders in the Italian pediatric population.

METHODS

Participants

Parents of typically developing children and adolescents aged 1 to 18 years completed an online survey. The survey was developed and conducted following the guidelines set by the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)40 and advertised via social media, for a limited time window (May 7–June 15, 2020). Data were organized according to age group: 1–3 years, 4–5 years, 6–12 years, and 13–18 years.

Data for this study were extrapolated from the results of a research project aiming to evaluate the differences in sleep habits and disorders before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown.41 In Italy, measures to prevent the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) included nationwide school closure from the March 4, 2020, until the end of the school year.

Retrospective questions were used to estimate perceived changes across 2 time periods: from “before the lockdown” (ie, in the last month before the outbreak) to “during the lockdown” (ie, in the 7 days prior to filling out the survey); for this study, only data on the period before lockdown were used. The period between reporting and the month prior to lockdown was approximately 1 month.

There was no monetary or credit compensation for participating in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Developmental and Social Psychology of the Sapienza University of Rome and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

A specific questionnaire gathering retrospective information about the month before the COVID-19 lockdown was arranged for the survey. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections. The first section was devoted to the collection of demographic data (age, sex caregiver education, region of Italy). A second section was organized to gather information on sleep arrangement and schedule during weekdays and during weekends (bedtime, rise time, sleep latency, sleep duration, co-sleeping). A third section of the survey was related to family composition, screen exposure time, and use of over-the-counter or prescription drugs for sleep disturbances. A further question asked if the child/adolescent was typically developing or if he/she had specific diseases, such as neurodevelopmental disorders, migraine, epilepsy, allergies, etc. Finally, caregivers completed a fourth section consisting of an adapted version of the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC).42

The SDSC was originally validated in a sample of 6- to 16-year-old healthy children from the general population,42 but was also used for younger neurotypical and neurodiverse children.43–45 In order to facilitate the completion of the questionnaire and simplify data collection, questions of the SDSC related to sleep-disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness and parasomnias were collapsed and reduced; therefore, the number of items was reduced to 13 items in total.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were applied to characterize sociodemographic variables, sleep patterns, and sleep disturbances. Data were reported as frequencies and percentages for comparisons between the age, sex, and geographical area groups (north, center, and south of Italy). Chi-square tests were conducted to compare sleep patterns, sleep schedule, and sleep disturbances between different sexes, age groups, and geographical area groups. Fisher’s exact test was applied when appropriate. Mode and mean values were calculated with their respective 95% confidence intervals for all sleep pattern parameters, in order to compare them between different age groups.

For all comparisons, P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant. For each sleep parameter, the comparisons between groups were reported only when statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Population demographics

A total of 5,805 participants completed the survey. From this sample, we excluded all individuals who reported to have comorbidities or neurodevelopmental disorders (1,491), in order to evaluate only healthy and typically developing children and adolescents. Respondents were 4,321 typically developing individuals, of whom 2,102 were females (48.6%). The sample demographics data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Age Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 Years (n = 1,272) (29.4%) | 4–5 Years (n = 896) (20.7%) | 6–12 Years (n = 1,843) (42.7%) | 13–18 Years (n = 310) (7.2%) | Total (n = 4,321) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 685 (53.9%) | 456 (50.9%) | 931 (50.5%) | 147 (47.4%) | 2,219 (51.4%) |

| Female | 587 (46.1%) | 440 (49.1%) | 912 (49.5%) | 163 (52.6%) | 2,102 (48.6%) |

| Italian region | |||||

| Northern Italy | 858 (67.5%) | 619 (69.1%) | 1,257 (68.2%) | 211 (68.1%) | 2,931 (68.2%) |

| Central Italy | 212 (16.5%) | 137 (15.3%) | 301 (16.3%) | 56 (18.1%) | 706 (16.3%) |

| Southern Italy | 202 (15.9%) | 140 (15.6%) | 285 (15.5%) | 42 (13.9%) | 670 (15.5%) |

| Family income | |||||

| Low | 157 (12.5%) | 88 (9.9%) | 170 (9.4%) | 28 (9.2%) | 443 (10.4%) |

| Middle | 1,024 (81.2%) | 714 (80.4%) | 1,479 (81.4%) | 242 (79.6%) | 3,459 (81.0%) |

| High | 80 (6.3%) | 86 (9.7%) | 167 (9.2%) | 34 (11.2%) | 367 (8.6%) |

| Siblings | |||||

| Only child | 769 (60.5%) | 332 (37.1%) | 443 (24.0%) | 61 (19.74%) | 1605 (37.2%) |

| 2 children | 442 (34.8%) | 491 (54.8%) | 1,135 (61.36) | 173 (55.8%) | 2,241 (51.9%) |

| 3 children | 53 (4.2%) | 63 (7.0%) | 227 (12.3%) | 64 (20.6%) | 407 (9.4%) |

| > 4 children | 7 (0.6%) | 10 (1.1%) | 37 (2.0%) | 12 (3.9%) | 66 (1.5%) |

Values are presented as n (%).

Bedtimes and rise times

Bedtime and rise times for age groups are shown in Table 2; P values show differences between all age groups. For the total sample, the most frequently reported bedtime was between 9 and 10 pm during weekdays (56.6%) and 10–11 pm during weekends (39.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sleep patterns in the different age groups.

| 1–3 Years | 4–5 Years | 6–12 Years | 13–18 Years | P | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedtime weekday | ||||||

| < 8 pm | 24 (1.9%; 1.1–2.6%) | 5 (0.6%; 0.1–1.0%) | 10 (0.5%; 0.2–0.9%) | 0 (0.0%; 0.0–0.0%) | < .001 | 39 (0.9%; 0.6–1.2%) |

| 8–9 pm | 315 (24.9%; 22.5–27.2%) | 244 (27.3%; 24.4–30.2%) | 462 (25.2%; 23.2–27.2%) | 10 (3.2%; 1.3–5.2%) | < .001 | 1,031 (23.9%; 22.7–25.2%) |

| 9–10 pm | 654 (51.6%; 48.9–54.4%) | 515 (57.6%; 54.4–60.8%) | 1,143 (62.3%; 60.1–64.5%) | 123 (39.8%; 34.3–45.3%) | < .001 | 2,435 (56.6%; 55.1–58.0%) |

| 10–11 pm | 227 (17.9%; 15.8–20.0%) | 118 (13.2%; 11.0–15.4%) | 204 (11.1%; 9.7–12.6%) | 137 (44.3%; 38.8–49.9%) | < .001 | 686 (15.9%; 14.8–17.0%) |

| 11 pm–12 am | 44 (3.5%; 2.5–4.5%) | 11 (1.2%; 0.5–2.0%) | 16 (0.9%; 0.4–1.3%) | 34 (11.0%; 7.5–14.5%) | < .001 | 105 (2.4%; 2.0–2.9%) |

| > 12 am | 3 (0.2%; 0.0–0.5%) | 1 (0.1%; −0.1–0.3%) | 0 (0.0%; 0.0–0.0%) | 5 (1.6%; 0.2–3.0%) | < .001 | 9 (0.2%; 0.1–0.3%) |

| Bedtime weekend | ||||||

| < 8 pm | 18 (1.4%; 0.8–2.1%) | 2 (0.2%; −0.1–0.5%) | 2 (0.1%; 0.0–0.3%) | 0 (0.0%; 0.0–0.0%) | < .001 | 22 (0.5%; 0.3–0.7%) |

| 8–9 pm | 190 (15.0%; 13.1–17.0%) | 98 (11.0%; 9.0–13.1%) | 96 (5.3%; 4.2–6.3%) | 2 (0.7%; −0.2–1.6%) | < .001 | 386 (9.0%; 8.2–9.9%) |

| 9–10 pm | 550 (43.5%; 40.7–46.2%) | 354 (39.8%; 36.6–43.0%) | 575 (31.6%; 29.4–33.7%) | 24 (7.8%; 4.8–10.8%) | < .001 | 1,503 (35.1%; 33.7–36.5%) |

| 10–11 pm | 399 (31.5%; 29.0–34.1%) | 343 (38.5%; 35.3–41.7%) | 836 (45.9%; 43.6–48.2%) | 92 (30.0%; 24.8–35.1%) | < .001 | 1,670 (39.0%; 37.5–40.4%) |

| 11 pm–12 am | 96 (7.6%; 6.1–9.0%) | 88 (9.9%; 7.9–11.8%) | 293 (16.1%; 14.4–17.8%) | 144 (46.9%; 41.3–52.5%) | < .001 | 621 (14.5%; 13.4–15.6%) |

| > 12 am | 12 (0.9%; 0.4–1.5%) | 5 (0.6%; 0.1–1.1%) | 20 (1.1%; 0.6–1.6%) | 45 (14.7%; 10.7–18.6%) | < .001 | 82 (1.9%; 1.5–2.3%) |

| Rise time weekday | ||||||

| < 7 am | 292 (23.0%; 20.7–25.4%) | 178 (20.0%; 17.3–22.6%) | 626 (34.1%; 31.9–36.3%) | 174 (56.3%; 50.8–61.8%) | < .001 | 1,270 (29.5%; 28.2–30.9%) |

| 7–8 am | 666 (52.6%; 49.8–55.3%) | 579 (64.9%; 61.8–68.0%) | 1,119 (61.0%; 58.7–63.2%) | 117 (37.9%; 32.5–43.3%) | < .001 | 2,481 (57.7%; 56.2–59.1%) |

| 8–9 am | 245 (19.3%; 17.2–21.5%) | 120 (13.5%; 11.2–15.7%) | 67 (3.7%; 2.8–4.5%) | 14 (4.5%; 2.2–6.8%) | < .001 | 446 (10.4%; 9.5–11.3%) |

| 9–10 am | 50 (3.9%; 2.9–5.0%) | 9 (1.0%; 0.4–1.7%) | 17 (0.9%; 0.5–1.4%) | 2 (0.6%; −0.2–1.5%) | < .001 | 78 (1.8%; 1.4–2.2%) |

| > 10 am | 14 (1.1%; 0.5–1.7%) | 6 (0.7%; 0.1–1.2%) | 6 (0.3%; 0.1–0.6%) | 2 (0.6%; −0.2–1.5%) | .071 | 28 (0.7%; 0.4–0.9%) |

| Risetime weekend | ||||||

| < 7 am | 157 (12.4%; 10.6–14.3%) | 43 (4.8%; 3.4–6.2%) | 65 (3.6%; 2.7–4.4%) | 10 (3.3%; 1.3–5.2%) | < .001 | 275 (6.4%; 5.7–7.2%) |

| 7–8 am | 478 (37.9%; 35.2–40.6%) | 281 (31.5%; 28.5–34.6%) | 359 (19.7%; 17.9–21.5%) | 23 (7.5%; 4.5–10.4%) | < .001 | 1,141 (26.6%; 25.3–28.0%) |

| 8–9 am | 453 (35.9%; 33.2–38.5%) | 371 (41.6%; 38.4–44.9%) | 768 (42.1%; 39.9–44.4%) | 92 (30.0%; 24.8–35.1%) | < .001 | 1,684 (39.3%; 37.9–40.8%) |

| 9–10 am | 145 (11.5%; 9.7–13.2%) | 164 (18.4%; 15.9–21.0%) | 497 (27.3%; 25.2–29.3%) | 88 (28.7%; 23.6–33.7%) | < .001 | 894 (20.9%; 19.7–22.1%) |

| > 10 am | 29 (2.3%; 1.5–3.1%) | 32 (3.6%; 2.4–4.8%) | 134 (7.4%; 6.2–8.5%) | 94 (30.6%; 25.5–35.8%) | < .001 | 289 (6.7%; 6.0–7.5%) |

Values are presented as n (%; 95% confidence interval).

The percentages of respondents reporting bedtime between 9 and 10 pm on weekdays and weekends were as follows: 51.6% and 43.5% for toddlers, 57.6% and 39.8% for preschoolers, 62.3% and 31.6% for school-aged children, and 39.8% and 7.8% for teenagers. In adolescence, the most frequently reported bedtime was between 10 and 11 pm during weekdays (44.3%) and between 11 pm and 12 am (46.9%) during weekends. Late bedtime (after 11 pm) changed relevantly between weekdays and weekends in all age groups: 3.7% vs 8.5% of toddlers, 1.3% vs 10.5% of preschoolers, 0.9% vs 17.2% of school-age children, and 12.6% vs 61.6% of adolescents (Table 2). During both weekdays and weekends, children and adolescents from northern Italy reported, on average, earlier bedtimes than those in central and southern Italy (Table S1 (312.1KB, pdf) in the supplemental material).

For rise time, the modal value during weekdays was between 7 and 8 am (57.7%); during weekends, children and adolescents tended to wake up later: modal value 8–9 am (39.3%) (Table 2).

The percentages of respondents reporting rise times between 7 and 10 am on weekdays and weekends were as follows: 52.6% and 37.9% for toddlers, 64.9% and 31.5% for preschoolers, 61.0% and 19.7% for school-aged children, and 37.9% and 7.5% for teenagers. Late rise time (after 9 am) changed relevantly between weekdays and weekends in all age groups: 5.0% vs 13.8% of toddlers, 1.7% vs 22.0% of preschoolers, 1.2% vs 34.7% of school-age children, and 1.2% vs 59.3% of adolescents (Table 2).

In line with the reported bedtime data, the proportion of children reporting rise times before 7 am was greater in northern than in central and southern Italy and vice versa after 8 am (Table S1 (312.1KB, pdf) ).

With regard to age-related differences, adolescents showed a delayed bedtime compared with the other age groups, with 12.6% of teenagers going to bed after 11 pm during weekdays (vs 0.9% of school-aged children) and 14.7% going to bed after 12 am during weekends (1.1% of school-aged children). Concerning rise time, on weekdays, adolescents were the group waking up early most frequently (56.3% before 7:00 am vs 34.1% of school-aged children), while they were the group most frequently waking up late during weekends (30.6% after 10:00 am vs 7.4% of school-aged children) (Table 2). No significant difference between sexes was found for rise time and bedtime.

Sleep duration

Night sleep duration, 24-h sleep duration, and sleep latency for age groups are shown in Table 3; P values show differences between all age groups. For the total sample, the most commonly reported night sleep duration was between 8 and 9 h during weekdays (37.9%), while during weekends, 36.5% of participants reported a night sleep duration between 9 and 10 h and 34.2% between 8 and 9 h per night (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sleep duration and sleep latency in the different age groups.

| 1–3 Years | 4–5 Years | 6–12 Years | 13–18 Years | P | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night sleep duration weekday | ||||||

| < 7 h | 86 (6.8%; 5.4–8.2%) | 20 (2.2%; 1.3–3.2%) | 29 (1.6%; 1.0–2.2%) | 37 (12.0%; 8.4–15.6%) | < .001 | 172 (4.0%; 3.4–4.6%) |

| 7–8 h | 176 (13.9%; 12.0–15.9%) | 132 (14.8%; 12.4–17.1%) | 313 (17.1%; 15.4–18.9%) | 124 (40.1%; 34.7–45.6%) | < .001 | 745 (17.4%; 16.2–18.5%) |

| 8–9 h | 400 (31.7%; 29.1–34.3%) | 305 (34.1%; 31.0–37.2%) | 799 (43.8%; 41.5–46.0%) | 121 (39.2%; 33.7–44.6%) | < .001 | 1,625 (37.9%; 36.4–39.3%) |

| 9–10 h | 406 (32.2%; 29.6–34.7%) | 318 (35.6%; 32.4–38.7%) | 568 (31.1%; 29.0–33.2%) | 25 (8.1%; 5.1–11.1%) | < .001 | 1,317 (30.7%; 29.3–32.1%) |

| > 10 h | 194 (15.4%; 13.4–17.4%) | 119 (13.3%; 11.1–15.5%) | 117 (6.4%; 5.3–7.5%) | 2 (0.6%; −0.2–1.5%) | < .001 | 432 (10.1%; 9.2–11.0%) |

| Night sleep duration weekend | ||||||

| < 7 h | 74 (5.9%; 4.6–7.1%) | 13 (1.5%; 0.7–2.3%) | 14 (0.8%; 0.4–1.2%) | 8 (2.6%; 0.8–4.4%) | < .001 | 109 (2.6%; 2.1–3.0%) |

| 7–8 h | 166 (13.1%; 11.3–15.0%) | 99 (11.2%; 9.1–13.2%) | 156 (8.6%; 7.3–9.9%) | 43 (14.0%; 10.1–17.8%) | < .001 | 464 (10.9%; 9.9–11.8%) |

| 8–9 h | 393 (31.1%; 28.5–33.6%) | 269 (30.3%; 27.3–33.4%) | 680 (37.5%; 35.3–39.7%) | 117 (38.0%; 32.6–43.4%) | < .001 | 1,459 (34.2%; 32.7–35.6%) |

| 9–10 h | 414 (32.8%; 30.2–35.3%) | 330 (37.2%; 34.0–40.4%) | 721 (39.8%; 37.5–42.0%) | 94 (30.5%; 25.4–35.7%) | < .001 | 1,559 (36.5%; 35.0–37.9%) |

| > 10 h | 217 (17.2%; 15.1–19.2%) | 176 (19.8%; 17.2–22.5%) | 242 (13.3%; 11.8–14.9%) | 46 (14.9%; 11.0–18.9%) | < .001 | 681 (15.9%; 14.8–17.0%) |

| 24-Hour weekday sleep | ||||||

| < 7 h | 11 (0.9%; 0.4–1.4%) | 10 (1.2%; 0.4–1.9%) | 28 (1.6%; 1.0–2.2%) | 30 (9.9%; 6.6–13.3%) | < .001 | 79 (1.9%; 1.5–2.3%) |

| 7–8 h | 50 (4.0%; 2.9–5.1%) | 68 (7.9%; 6.1–9.7%) | 299 (16.8%; 15.1–18.5%) | 119 (39.4%; 33.9–44.9%) | < .001 | 536 (12.8%; 11.8–13.8%) |

| 8–9 h | 101 (8.2%; 6.6–9.7%) | 223 (25.8%; 22.9–28.7%) | 768 (43.2%; 40.9–45.5%) | 124 (41.1%; 35.5–46.6%) | < .001 | 1,216 (29.1%; 27.7–30.5%) |

| 9–10 h | 232 (18.8%; 16.6–21.0%) | 317 (36.6%; 33.4–39.9%) | 557 (31.3%; 29.2–33.5%) | 26 (8.6%; 5.4–11.8%) | < .001 | 1,132 (27.1%; 25.7–28.4%) |

| 10–11 h | 382 (30.9%; 28.4–33.5%) | 170 (19.7%; 17.0–22.3%) | 114 (6.4%; 5.3–7.5%) | 2 (0.7%; −0.3–1.6%) | < .001 | 668 (16.0%; 14.9–17.1%) |

| 11–12 h | 290 (23.5%; 21.1–25.8%) | 60 (6.9%; 5.2–8.6%) | 9 (0.5%; 0.2–0.8%) | 1 (0.3%; −0.3–1.0%) | < .001 | 360 (8.6%; 7.8–9.5%) |

| > 12 h | 169 (13.7%; 11.8–15.6%) | 17 (2.0%; 1.0–2.9%) | 4 (0.2%; 0.0–0.4%) | 0 (0.0%; 0.0–0.0%) | < .001 | 190 (4.5%; 3.9–5.2%) |

| 24-Hour weekend sleep | ||||||

| < 7 h | 9 (0.7%; 0.3–1.2%) | 5 (0.6%; 0.1–1.1%) | 13 (0.7%; 0.3–0.3%) | 7 (2.3%; 0.6–4.0%) | .026 | 34 (0.8%; 0.5–1.1%) |

| 7–8 h | 43 (3.5%; 2.5–4.5%) | 58 (6.8%; 5.1–8.4%) | 149 (8.4%; 7.1–7.1%) | 40 (13.3%; 9.5–17.1%) | < .001 | 290 (7.0%; 6.2–7.7%) |

| 8–9 h | 100 (8.1%; 6.6–9.6%) | 190 (22.1%; 19.4–24.9%) | 647 (36.6%; 34.4–34.4%) | 112 (37.2%; 31.7–42.7%) | < .001 | 1,049 (25.2%; 23.9–26.5%) |

| 9–10 h | 208 (16.8%; 14.7–18.9%) | 279 (32.5%; 29.4–35.7%) | 710 (40.2%; 37.9–37.9%) | 93 (30.9%; 25.7–36.1%) | < .001 | 1,290 (31.0%; 29.6–32.4%) |

| 10–11 h | 393 (31.8%; 29.2–34.4%) | 219 (25.5%; 22.6–28.4%) | 223 (12.6%; 11.1–11.1%) | 42 (14.0%; 10.0–17.9%) | < .001 | 877 (21.1%; 19.8–22.3%) |

| 11–12 h | 305 (24.7%; 22.3–27.1%) | 90 (10.5%; 8.4–12.5%) | 19 (1.1%; 0.6–0.6%) | 5 (1.7%; 0.2–3.1%) | < .001 | 419 (10.1%; 9.2–11.0%) |

| > 12 h | 179 (14.5%; 12.5–16.4%) | 17 (2.0%; 1.0–2.9%) | 5 (0.3%; 0.0–0.0%) | 2 (0.7%; −0.3–1.6%) | < .001 | 203 (4.9%; 4.2–5.5%) |

| Sleep latency weekday | ||||||

| 5–15 min | 469 (37.1%; 34.5–39.8%) | 438 (49.0%; 45.7–52.3%) | 1,096 (59.8%; 57.6–62.1%) | 162 (52.6%; 47.0–58.2%) | < .001 | 2,165 (50.4%; 48.9–51.9%) |

| 15–30 min | 598 (47.3%; 44.6–50.1%) | 371 (41.5%; 38.3–44.7%) | 613 (33.5%; 31.3–35.6%) | 104 (33.8%; 28.5–39.0%) | < .001 | 1,686 (39.2%; 37.8–40.7%) |

| 30–60 min | 179 (14.2%; 12.2–16.1%) | 80 (8.9%; 7.1–10.8%) | 113 (6.2%; 5.1–7.3%) | 38 (12.3%; 8.7–16.0%) | < .001 | 410 (9.5%; 8.7–10.4%) |

| > 60 min | 17 (1.3%; 0.7–2.0%) | 5 (0.6%; 0.1–1.0%) | 10 (0.5%; 0.2–0.9%) | 4 (1.3%; 0.0–2.6%) | .059 | 36 (0.8%; 0.6–1.1%) |

| Sleep latency weekend | ||||||

| 5–15 min | 428 (33.9%; 31.3–36.5%) | 404 (45.2%; 41.9–48.5%) | 1,044 (57.2%; 54.9–59.4%) | 153 (49.7%; 44.1–55.3%) | < .001 | 2,029 (47.3%; 45.8–48.8%) |

| 15–30 min | 625 (49.5%; 46.7–52.2%) | 381 (42.6%; 39.4–45.9%) | 608 (33.3%; 31.1–35.5%) | 105 (34.1%; 28.8–39.4%) | < .001 | 1,719 (40.1%; 38.6–41.5%) |

| 30–60 min | 190 (15.0%; 13.1–17.0%) | 105 (11.7%; 9.6–13.9%) | 160 (8.8%; 7.5–10.1%) | 43 (14.0%; 10.1–17.8%) | < .001 | 498 (11.6%; 10.6–12.6%) |

| > 60 min | 20 (1.6%; 0.9–2.3%) | 4 (0.4%; 0.0–0.9%) | 14 (0.8%; 0.4–1.2%) | 7 (2.3%; 0.6–3.9%) | .006 | 45 (1.0%; 0.7–1.4%) |

Values are presented as n (%; 95% confidence interval).

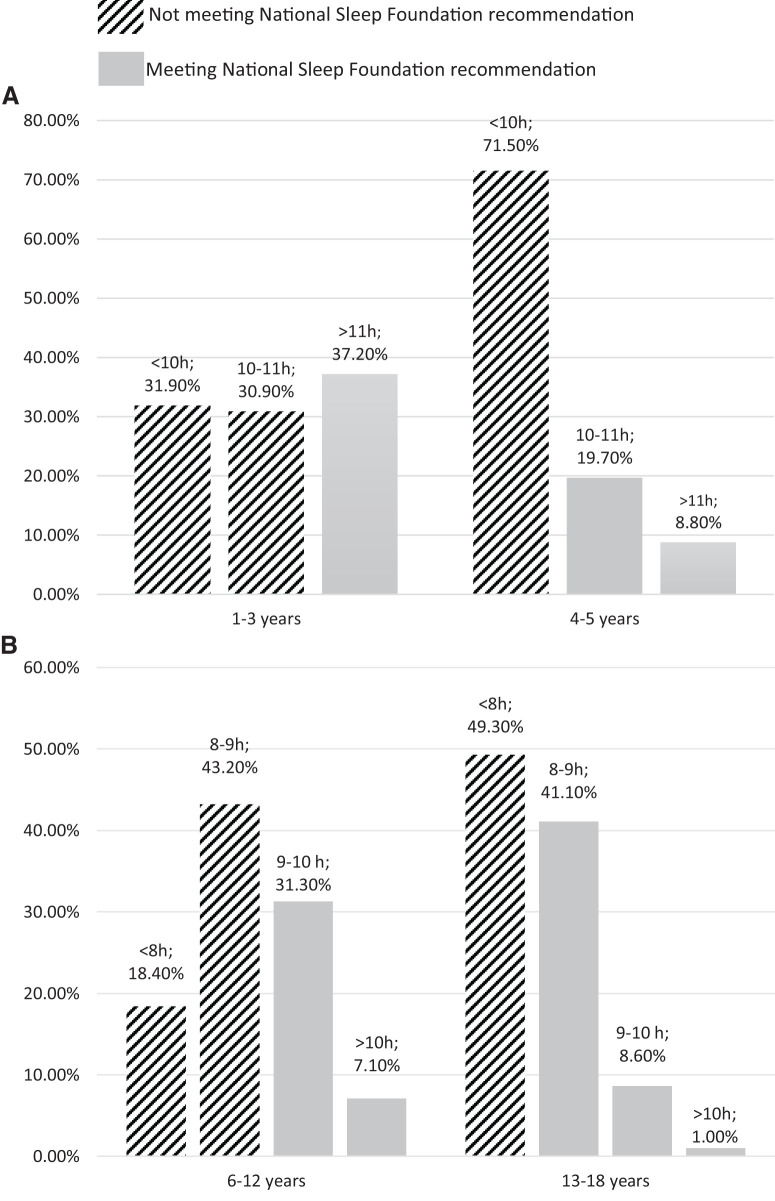

With regard to age-appropriate nappers (toddlers and preschoolers), the measure of 24-h sleep duration can be more informative than night sleep duration only, due to the presence of daytime naps. During weekdays, most toddlers (30.9%) slept between 10 and 11 h/day, whereas most preschoolers tended to sleep between 9 and 10 h/day (36.6%). Similar results were found on weekends: 31.8% of toddlers slept 10–11 h/day; 32.5% of preschoolers slept 9–10 h/day (Table 3). A relevant percentage of children and adolescents had a shorter 24-h sleep duration than recommended, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Twenty-four-hour sleep duration.

(A) Twenty-four-hour sleep duration in toddlers and preschoolers during weekdays. Recommended sleep duration according to the National Sleep Foundation: 11–14 hours/day for toddlers and 10–13 hours/day for preschoolers.16 (B) Twenty-four-hour sleep duration in school-aged children and adolescents during weekdays. Recommended sleep duration according to the National Sleep Foundation: 9–11 hours/day for school-aged children and 8–10 hours/day for adolescents.16

Daytime napping of at least 1 hour was present in 92.6% of toddlers, in 35.2% of preschoolers, in 2.2% of school-aged children, and in 4.6% of adolescents (Table S2 (312.1KB, pdf) ). Night sleep duration on school days was found to be significantly different for adolescents compared with the other age groups, with 12.0% of adolescents sleeping less than 7 h per night (vs 1.6% of school-aged children) (Table 3). During weekend nights, both adolescents and school-aged children tended to sleep 8–10 h per night (68.5% of adolescents and 77.3% of school-aged children). The differences between Italian regions in night and 24-h sleep duration are reported in Table S1 (312.1KB, pdf) . No significant difference between sexes was found for night and 24-h sleep duration.

Sleep latency

The percentage of children taking more than 30 minutes to fall asleep progressively decreased from toddlers to school-aged children (15.5% of toddlers, 9.5% of preschoolers, and 6.7% of school-aged children). In adolescence, this percentage increased, with 13.6% of teenagers needing more than 30 minutes to fall asleep (Table 3).

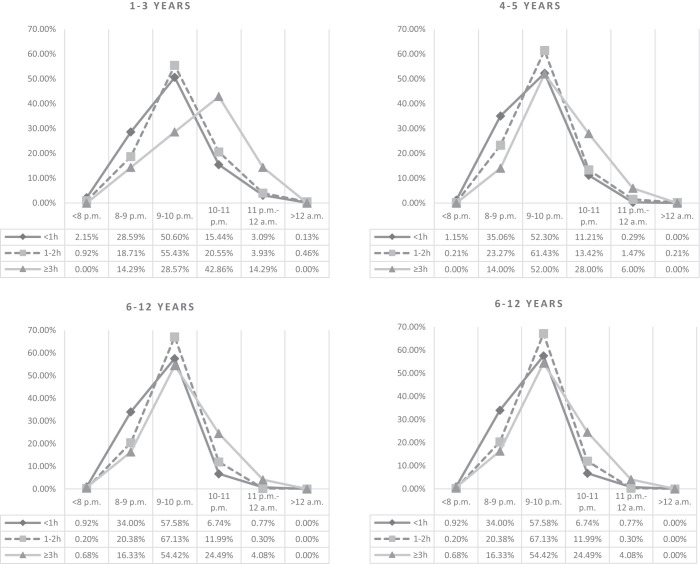

Screen time

Up to 38.3% of children between 1 and 3 years of age were reported to spend more than 1 h/day using devices with screens such as a smartphone, tablet, or television. After 4 years of age, the majority of children and adolescents spent more than 1 h/day of screen time, with 31.1% of adolescents using electronic devices for 2 h/day or more. The proportion of children going to bed later increases as the number of hours spent in front of a screen increases (Figure 2). No significant correlation was found between screen time and night/total sleep duration and sleep latency, both on weekdays and weekends.

Figure 2. Bedtime changes for screen time spent in different age groups.

Numbers of hours/day spent on screen devices are indicated as follows: < 1 hour/day (< 1 h); from 1 to 2 hours/day (1–2 h); 3 hours or more (≥ 3 h).

Co-sleeping

Co-sleeping was adopted by families of 37.0% of toddlers, 26.7% of preschoolers, 13.3% of school-aged children, and 2.3% of adolescents. There were also significant differences in co-sleeping among geographical areas: northern Italy, 22.7%; central Italy, 25.3%; southern Italy, 28.0% (χ2 = 8.755; P = .013) (Table 3) and among sexes: males (26.2%) and females (21.5%).

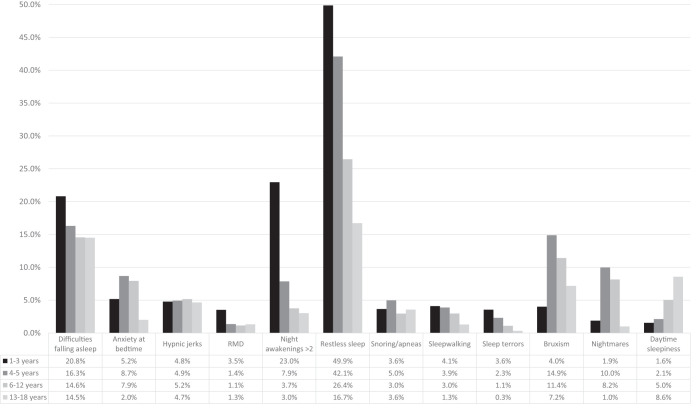

Sleep disorders

The prevalence of the sleep disturbances investigated through our questionnaire among different age groups and in the whole sample is summarized in Table S3 (312.1KB, pdf) and in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the different age groups.

RMD = rhythmic movements disorder.

The most frequently reported sleep disorder in our sample was restless sleep (35.6%), followed by difficulties falling asleep (16.8%), > 2 night awakenings (9.9%), and bruxism (9.6%). Despite being the most reported sleep disturbance at all ages, restless sleep tended to significantly decrease in frequency with age (from 49.9% in toddlers to 16.7% in adolescents; P < .05). In addition to restless sleep, the main disturbances reported were as follows: (1) in toddlers, > 2 night awakenings (23%) and difficulties falling asleep (20.8%); (2) in children aged 4 to 12 years, bruxism (14.9% in preschoolers and 11.4% in school-aged children) and difficulties falling asleep (16.3% in preschoolers and 14.6% in school-aged children); (3) in adolescents, difficulties falling asleep (14.5%), daytime sleepiness (8.6%), and bruxism (7.2%).

The reported prevalence of snoring/apnea and hypnic jerks did not differ significantly between age groups. Sleepwalking and sleep terrors tended to decrease with age, while nightmares increased in preschoolers and schoolers. On the other hand, daytime sleepiness increased with age.

None of the investigated sleep disturbances was found to have a significantly different prevalence rate in the different geographical areas of Italy (Table S4 (312.1KB, pdf) ). The majority of sleep disturbances were not found to be significantly more prevalent in males or females, except for hypnic jerks and bruxism (more frequent in males) and difficulties falling asleep (more frequent in females) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sleep disorders by sex.

| Female | Male | P | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties falling asleep | 316 (18.9%; 17.1–20.8%) | 269 (14.8%; 13.2–16.4%) | .001 | 585 (16.8%; 15.5–18.0%) |

| Anxiety at bedtime | 128 (6.9%; 5.8–8.1%) | 132 (6.7%; 5.6–7.8%) | .773 | 260 (6.8%; 6.0–7.6%) |

| Hypnic jerks | 85 (4.2%; 3.3–5.1%) | 120 (5.7%; 4.7–6.6%) | .034 | 205 (5.0%; 4.3–5.6%) |

| RMD | 33 (1.6%; 1.1–2.1%) | 48 (2.2%; 1.6–2.8%) | .150 | 81 (1.9%; 1.5–2.3%) |

| Night awakenings > 2 | 180 (9.4%; 8.1–10.7%) | 213 (10.4%; 9.1–11.7%) | .300 | 393 (9.9%; 9.0–10.9%) |

| Restless sleep | 646 (34.1%; 32.0–36.2%) | 748 (37.0%; 34.9–39.1%) | .058 | 1,394 (35.6%; 34.1–37.1%) |

| Snoring/apneas | 75 (3.6%; 2.8–4.4%) | 80 (3.6%; 2.9–4.4%) | .940 | 155 (3.6%; 3.1–4.2%) |

| Sleepwalking | 70 (3.4%; 2.6–4.2%) | 72 (3.3%; 2.6–4.1%) | .908 | 142 (3.4%; 2.8–3.9%) |

| Sleep terrors | 42 (2.0%; 1.4–2.7%) | 42 (1.9%; 1.4–2.5%) | .812 | 84 (2.0%; 1.6–2.4%) |

| Bruxism | 176 (8.6%; 7.4–9.8%) | 230 (10.6%; 9.3–11.9%) | .026 | 406 (9.6%; 8.7–10.5%) |

| Nightmares | 124 (6.6%; 5.5–7.7%) | 108 (5.4%; 4.4–6.4%) | .107 | 232 (6.0%; 5.2–6.7%) |

| Daytime sleepiness | 80 (4.1%; 3.2–5.0%) | 66 (3.2%; 2.4–3.9%) | .113 | 146 (3.6%; 3.0–4.2%) |

| Co-sleeping | 425 (21.5%; 19.8–23.3%) | 538 (26.2%; 24.4–28.1%) | < .001 | 963 (23.9%; 22.7–25.2%) |

Values are presented as n (%; 95% confidence interval). RMD = rhythmic movements disorder.

DISCUSSION

In our study, based on a large cohort of Italian children, we used online parent-reported measures aiming to provide up-to-date data concerning Italian children’s sleep habits, and provide the estimated prevalence of the most common sleep disorders in the Italian pediatric population.

Consistent with other studies,18,20,25,46,47 a developmental trend in some sleep characteristics can be found through childhood and adolescence. In our sample, indeed, total and night sleep time decreased with increasing age, especially during weekdays. An important decrease in total and night sleep was reported in the transition from school age to adolescence. It should be noted that most of our sample did not meet the age-specific National Sleep Foundation recommendations for total sleep duration16: during weekdays, approximately 62.8% of toddlers and 71.5% of preschoolers slept less than 11 and 10 h/day, respectively (which is the minimum amount of sleep recommended), whereas 61.6% of school-aged children slept less than the recommended 9 h/day and 49.3% of adolescents slept less than 8 h/day (minimum number of hours suggested by the National Sleep Foundation) (Figure 1). Our results are in line with the findings of a recent Italian systematic review48 and seem even more worrying than those found by a large survey conducted in Italy in 2017,32 according to which one-third of children and half of teenagers slept less than the recommended amount. In our study, instead, preschoolers were the age group that more frequently did not have enough sleep. Moreover, the rate of individuals having insufficient sleep in Italy is higher than that reported by international studies: in a recent survey in American children,19 recommendations on sleep duration were not met by 36.4% of school-aged children and 31.9% of adolescents. It is worth noting that, in the teenage years, sleep times vary more relevantly than in other developmental periods between weekdays and weekends (12.6% of adolescents go to bed after 11 pm during weekdays vs 61.6% during weekends), probably as a result of social habits.

Our survey also investigated differences in sleep duration between Italian geographical areas. Some differences in weekday bedtime and rise time across northern and central/southern Italy were found, with children and adolescents of northern Italy showing more frequent earlier bedtime and rise time than their peers in central and southern Italy. This could be explained both by cross-cultural differences (eg meal time and working time) and/or by differences in sunlight exposure, influencing circadian rhythms.49 Our findings are corroborated by a study in Chile demonstrating that inhabitants of northern latitudes slept less than their southern counterparts and postulated that people living at different latitudes are exposed to different sunset and sunrise times, affecting their sleep time.50 With regard to cross-cultural differences, a multicentric study showed that sleep patterns varied significantly between predominantly Asian or White preschool-aged children, with a wide range of bedtimes, varying from as early as 7:43 pm in Australia and New Zealand to as late as 10:26 pm in India.51 Moreover, even in the same country, important variations in sleep patterns between weekdays and weekends can be found. For instance, Canadian children and adolescents were reported to have bedtimes ranging from around 10 pm during weekdays up to almost midnight during weekends.52 It is therefore difficult even for scientific societies to provide recommended bedtimes and rise times, given the normal variability in daily routines.16,17 However, considering that children in Italy start school around 8:00 am, late bedtimes during weekdays are alarming and suggestive of insufficient sleep.

A previous study on sleep habits in Italian children under 6 years of age showed a decrease with age of total sleep time, sleep latency, night awakenings, and sleep problems.25 Consistently, in our sample, total sleep time seems to decrease with increasing age, as well as sleep latency, night awakenings, and difficulties falling asleep, which decrease with age from 0 to 6 years, as in the previously mentioned study.25

Among the factors affecting sleep at developmental age, screen use certainly deserves attention, considering the unquestionable rise of the digital environment in the last decades. Medical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization, have recommended that children aged 0–1 year should not be exposed to media use and that children 2–5 years of age should not exceed 1–2 h of screen time per day.22,23 However, children worldwide do not follow these recommendations in everyday life, using screens for longer times.24 For example, a study showed that, as of 2014 in the United States, children aged 2 years or less averaged around 3 h/day of screen time.53 In our sample, 3.7% of children aged 1–5 years exceeded the 2 h of screen time per day, which is even more worrisome considering the common bias in parental reports, which show difficulties in estimating the exact time spent on electronic devices.54 This bias could also be present for our adolescent sample, given that the parents reported that 31.1% of their adolescent children spent 2 h or more using electronic devices, while the average daily screen time reported in the literature is 8.8 h in teenagers aged 13–17 years.55

Prolonged screen time has been reported to affect both sleep duration and sleep quality. Accordingly, a 2014 US poll by the National Sleep Foundation showed that mean sleep time is significantly reduced in children and adolescents who use their electronic devices in their bedroom (7.3 h/night), compared with their peers who do not (8.3 h/night).46 Furthermore, longer screen times have been associated with increased sleep disturbances, as reported by parental questionnaires across all ages.55 More recently, research focused on new media usage, with a large Italian survey showing that toddlers using a smartphone or tablet daily had higher odds of sleeping less and taking longer to fall asleep.33 In our sample, longer screen time was associated with later weekday bedtime in all age groups, but not specifically with any sleep disturbance.

A common, yet controversial, sleep practice in children is the sharing of a sleeping surface or room (ie, co-sleeping and/or bed-sharing). There is great diversity in the frequency of co-sleeping and/or bed-sharing around the globe, with Western nations generally exhibiting lower rates than developing countries.56 However, it is worth noting that, even within the same countries, a high heterogeneity has been documented in the prevalence of co-sleeping.57 Also, in our sample, the prevalence of co-sleeping increases from northern (22.7%) to southern Italy (28%). Moreover, interestingly, in our sample, more males than females co-slept with their parents, which has been described previously, even though no clear explanation has been provided.58 With regard to age-specific prevalence, a recent Italian systematic review reported co-sleeping in 37–80% of infants and toddlers.48 Many factors could be related to co-sleeping in children and adolescents, including household factors (ie, number of bedrooms, siblings) or sociocultural factors, which we have not investigated in the present study and which could be studied in future research. Similarly, it should be noted that co-sleeping could have influenced parent knowledge of some sleep-related problems, such as restlessness, snoring, bruxism, or parasomnias. Our results (37%) are consistent with the most recent literature59,60 and confirm that co-sleeping is a common practice in Italy, influenced by geographical differences among regions.

The most frequent sleep problem reported in our sample was restless sleep (Figure 3). Restless sleep disorder, a newly defined clinical entity, is characterized by large body movements and repositioning during the whole night, for a minimum of 5 movements/h, in the absence of another condition able to explain it.61–63 The prevalence of restless sleep disorder is estimated to be 7.7% among children referred to a single sleep disorders center.64 We believe that at least a portion of the individuals reporting restless sleep in our survey might have been affected by restless sleep disorder, but caution should be made when interpreting the findings about restless sleep, as it can be a clinical manifestation found in up to approximately 80% of children with other sleep, neurodevelopmental, or medical conditions.65 An interesting and new addition to the literature of restless sleep is the fact that, according to parents’ report, the prevalence of restlessness during sleep decreases with age.

On the contrary, the disorder with the lowest prevalence in our sample was rhythmic movements disorder (eg, head banging and body rocking; Figure 3). The limited epidemiological studies on childhood rhythmic movements disorder provide a wide range of prevalences,66 ranging from 1.4% in school-aged children up to 66% in infants.67,68 However, in accordance with our results, previous studies also found a decreasing prevalence of rhythmic movements disorder after the first year of life.67,69,70

Another common sleep-related movements disorder is sleep bruxism, described as the occurrence of phasic or tonic masticatory muscle activity during sleep.71 It is more frequently described in individuals with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, obstructive sleep apnea, or epilepsy.72 A highly variable prevalence of bruxism has been reported in children, ranging from 6% to 50%.73 The results of our study support the lower prevalence rates, with a peak prevalence during preschool age (Figure 3).

From a general standpoint, parasomnias in our sample tended to decrease with age, in agreement with the literature70: sleep terrors and sleepwalking showed the highest prevalence in children aged less than 4 years, while they were the least prevalent parasomnia during adolescence (Figure 3). On the other hand, nightmares showed the highest prevalence in preschoolers and a progressive decrease with age (Figure 3), as previously reported by other authors.74

In our population, difficulties falling asleep had a prevalence ranging from 20.8% in toddlers to approximately 15% in the other age groups, while night awakenings (> 2/night) occurred in 23% of toddlers and decreased to 3% in adolescence, according to the literature.57 On the other hand, a recent Norwegian study conducted through direct semi-structured interviews found that only 2.5% of children aged 4–6 years met the criteria for insomnia.75 In a cohort of children aged 5–12 years, insomnia symptoms were found in 19.3% of the sample, with difficulty falling asleep being the most frequent type of complaint among those with insomnia (44.7%).76 In a study in 6- to 18-year-old children and adolescents, 18.8% were diagnosed with insomnia.77 Adolescent insomnia is one of the most studied sleep disorders, frequently associated with sleep hygiene problems and delayed sleep phase.37 Its prevalence differs significantly in different studies, ranging from 4% to 39%, probably because of the diagnostic tools and criteria used38,78–81; in our study, sleep-onset insomnia (measured as parent-reported “difficulties falling asleep”) was found in 14.5% of adolescents.

Excessive daytime sleepiness, defined as difficulty staying awake or an increased desire to sleep during the day, is a relatively common symptom among children and adolescents. In prepubertal children, a prevalence ranging from 4% to 20% has been found in different studies,68,76,82 while during adolescence, it increases to 16–47%.82–84 This increasing trend with age is supported also by our data (Figure 3), even if, in our population, the prevalence of daytime sleepiness was lower than in the literature, possibly because parental reports might not reliably identify excessive daytime sleepiness.

Limitations

As information was been collected through questionnaires completed by parents, it is possible that they tended to give responses that minimalize bedtime and screen exposure of their children or that they were not able to give accurate information about their son’s sleep, especially if an adolescent. Otherwise, when co-sleeping is present, parents can give more precise details. Moreover, parent-reported measures could be influenced by the distress the pandemic caused and by recall bias (sleep data regarding the month before the COVID-19 lockdown were collected later, during the lockdown itself); additionally, self-selection bias is inherent with the online survey methodology that uses nonprobability sampling. Furthermore, as some measures (ie, bedtime, rise time, sleep duration, sleep latency, difficulties falling asleep) were collected as separate items on the online survey, it is possible that parent-provided data did not always match with their other answers (eg, bedtimes not completely coherent with reported sleep duration). However, despite these limitations, parental reports have been demonstrated to be a reliable source of information, especially in large samples, typically agreeing with direct measurements of sleep.85–87

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study showed that Italian children are at high risk of various sleep symptoms and disorders. It also emphasizes the importance of the developmentally based evaluation of sleep habits and disorders, since there are several age-related changes that should be taken into account by health care providers. Sleep can be influenced by a variety of ecological, cultural, and ethnic differences, as noted within regions of Italy.

Therefore, it is highly recommended that all pediatric health care providers consider screening for sleep issues in their comprehensive assessment of all children and adolescents, according to age, sex, development, and relative change in prevalence of sleep disorders.

Future longitudinal studies (possibly including objective measurements of sleep, such as actigraphy) are needed to assess the negative trend in total sleep duration as well as the relationship between sleep and screen exposure. Moreover, reliable and recent data on sleep in children are fundamental for pediatricians and other professionals to better understand sleep and to detect its disturbances in children and adolescents early.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions: Each author made a substantive intellectual contribution to the study. Maria Breda: data curation, analysis, and interpretation; writing and revision of the original draft; review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Arianna Belli: data interpretation; writing and revision of the original draft; review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dario Esposito: data interpretation; writing and revision of the original draft; review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Andrea Di Pilla: data curation, analysis and interpretation; review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Maria Grazia Melegari: conceptualization and study design; data analysis, data collection and interpretation; writing and revision of the manuscript; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Lourdes DelRosso: review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Raffaele Ferri: conceptualization and study design; review and editing of final draft; approved the final manuscript as submitted. Oliviero Bruni: conceptualization and study design, data analysis, data interpretation; writing and revision of the manuscript; approved the final manuscript as submitted.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gerber L . Sleep deprivation in children: a growing public health concern . Nursing. 2014. ; 44 ( 4 ): 50 – 54 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sigurdson K , Ayas NT . The public health and safety consequences of sleep disorders . Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007. ; 85 ( 1 ): 179 – 183 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ezenwanne E . Current concepts in the neurophysiologic basis of sleep; a review . Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011. ; 1 ( 2 ): 173 – 179 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peirano PD , Algarín CR . Sleep in brain development . Biol Res. 2007. ; 40 ( 4 ): 471 – 478 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruni O , Melegari MG , Esposito A , et al . Executive functions in preschool children with chronic insomnia . J Clin Sleep Med. 2020. ; 16 ( 2 ): 231 – 241 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernier A , Beauchamp MH , Bouvette-Turcot AA , Carlson SM , Carrier J . Sleep and cognition in preschool years: specific links to executive functioning . Child Dev. 2013. ; 84 ( 5 ): 1542 – 1553 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson TD , Nelson JM , Kidwell KM , James TD , Espy KA . Preschool sleep problems and differential associations with specific aspects of executive control in early elementary school . Dev Neuropsychol. 2015. ; 40 ( 3 ): 167 – 180 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dewald JF , Meijer AM , Oort FJ , Kerkhof GA , Bögels SM . The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review . Sleep Med Rev. 2010. ; 14 ( 3 ): 179 – 189 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drake C , Nickel C , Burduvali E , Roth T , Jefferson C , Pietro B . The Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale (PDSS): sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children . Sleep. 2003. ; 26 ( 4 ): 455 – 458 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfson AR , Carskadon MA . Understanding adolescents’ sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal . Sleep Med Rev. 2003. ; 7 ( 6 ): 491 – 506 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vriend J , Davidson F , Rusak B , Corkum P . Emotional and cognitive impact of sleep restriction in children . Sleep Med Clin. 2015. ; 10 ( 2 ): 107 – 115 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldstein AN , Walker MP . The role of sleep in emotional brain function . Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014. ; 10 ( 1 ): 679 – 708 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldstein-Piekarski AN , Greer SM , Saletin JM , Walker MP . Sleep deprivation impairs the human central and peripheral nervous system discrimination of social threat . J Neurosci. 2015. ; 35 ( 28 ): 10135 – 10145 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horne JA . Sleep function, with particular reference to sleep deprivation . Ann Clin Res. 1985. ; 17 ( 5 ): 199 – 208 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alfano CA , Gamble AL . The role of sleep in childhood psychiatric disorders . Child Youth Care Forum. 2009. ; 38 ( 6 ): 327 – 340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirshkowitz M , Whiton K , Albert SM , et al . National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report . Sleep Health. 2015. ; 1 ( 4 ): 233 – 243 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paruthi S , Brooks LJ , D’Ambrosio C , et al . Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . J Clin Sleep Med. 2016. ; 12 ( 6 ): 785 – 786 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mindell JA , Meltzer LJ , Carskadon MA , Chervin RD . Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America poll . Sleep Med. 2009. ; 10 ( 7 ): 771 – 779 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsao HS , Gjelsvik A , Sojar S , Amanullah S . Sounding the alarm on sleep: a negative association between inadequate sleep and flourishing . J Pediatr. 2021. ; 228 : 199 – 207.e3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. 2006 Sleep in America poll—teens and Sleep . Sleep Health. 2015. ; 1 ( 2 ): e5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wheaton AG , Jones SE , Cooper AC , Croft JB . Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students—United States, 2015 . MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018. ; 67 ( 3 ): 85 – 90 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guram S , Heinz P . Media use in children: American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations 2016 . Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018. ; 103 ( 2 ): 99 – 101 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age . World Health Organization; 2019. . http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541170/ . Accessed August 2, 2021. [PubMed]

- 24. Madigan S , Racine N , Tough S . Prevalence of preschoolers meeting vs exceeding screen time guidelines . JAMA Pediatr. 2020. ; 174 ( 1 ): 93 – 95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ottaviano S , Giannotti F , Cortesi F , Bruni O , Ottaviano C . Sleep characteristics in healthy children from birth to 6 years of age in the urban area of Rome . Sleep. 1996. ; 19 ( 1 ): 1 – 3 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LeBourgeois MK , Giannotti F , Cortesi F , Wolfson AR , Harsh J . The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents . Pediatrics. 2005. 115 ( Suppl 1 ): 257 – 265 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Russo PM , Bruni O , Lucidi F , Ferri R , Violani C . Sleep habits and circadian preference in Italian children and adolescents . J Sleep Res. 2007. ; 16 ( 2 ): 163 – 169 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruni O , Sette S , Fontanesi L , Baiocco R , Laghi F , Baumgartner E . Technology use and sleep quality in preadolescence and adolescence . J Clin Sleep Med. 2015. ; 11 ( 12 ): 1433 – 1441 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malloggi S , Conte F , Gronchi G , Ficca G , Giganti F . Prevalence and determinants of bad sleep perception among Italian children and adolescents . Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. ; 17 ( 24 ): E9363 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Varghese NE , Santoro E , Lugo A , et al . The role of technology and social media use in sleep-onset difficulties among Italian adolescents: cross-sectional study . J Med Internet Res. 2021. ; 23 ( 1 ): e20319 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Giannotti F , Cortesi F , Sebastiani T , Vagnoni C . Sleeping habits in Italian children and adolescents . Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2005. ; 3 ( 1 ): 15 – 21 . [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brambilla P , Giussani M , Pasinato A , et al. “Ci piace sognare” Study Group . Sleep habits and pattern in 1-14 years old children and relationship with video devices use and evening and night child activities . Ital J Pediatr. 2017. ; 43 ( 1 ): 7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chindamo S , Buja A , DeBattisti E , et al . Sleep and new media usage in toddlers . Eur J Pediatr. 2019. ; 178 ( 4 ): 483 – 490 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bruni O , Sette S , Angriman M , et al . Clinically oriented subtyping of chronic insomnia of childhood . J Pediatr. 2018. ; 196 : 194 – 200.e1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Castronovo V , Zucconi M , Nosetti L , et al . Prevalence of habitual snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in preschool-aged children in an Italian community . J Pediatr. 2003. ; 142 ( 4 ): 377 – 382 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brunetti L , Rana S , Lospalluti ML , et al . Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a cohort of 1,207 children of southern Italy . Chest. 2001. ; 120 ( 6 ): 1930 – 1935 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nunes ML , Bruni O . Insomnia in childhood and adolescence: clinical aspects, diagnosis, and therapeutic approach . J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015. ; 91 ( 6, Suppl 1 ): S26 – S35 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kansagra S . Sleep disorders in adolescents . Pediatrics. 2020. ; 145 ( Suppl 2 ): S204 – S209 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Galland BC , Taylor BJ , Elder DE , Herbison P . Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studies . Sleep Med Rev. 2012. ; 16 ( 3 ): 213 – 222 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eysenbach G . Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) . J Med Internet Res. 2004. ; 6 ( 3 ): e34 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bruni O , Malorgio E , Doria M , et al . Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the Covid-19 outbreak . Sleep Med. 2022. ; 91 : 166 – 174 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bruni O , Ottaviano S , Guidetti V , et al . The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence . J Sleep Res. 1996. ; 5 ( 4 ): 251 – 261 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romeo DM , Bruni O , Brogna C , et al . Application of the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) in preschool age . Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013. ; 17 ( 4 ): 374 – 382 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Romeo DM , Cordaro G , Macchione E , et al . Application of the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) in infants and toddlers (6-36 months) . Sleep Med. 2021. ; 81 : 62 – 68 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Romeo DM , Brogna C , Belli A , et al . Sleep eisorders in autism spectrum disorder pre-school children: an evaluation using the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children . Medicina (Kaunas). 2021. ; 57 ( 2 ): 95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Buxton OM , Chang AM , Spilsbury JC , Bos T , Emsellem H , Knutson KL . Sleep in the modern family: protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep . Sleep Health. 2015. ; 1 ( 1 ): 15 – 27 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ohayon MM , Carskadon MA , Guilleminault C , Vitiello MV . Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan . Sleep. 2004. ; 27 ( 7 ): 1255 – 1273 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bacaro V , Gavriloff D , Lombardo C , Baglioni C . Sleep characteristics in the Italian pediatric population: a systematic review . Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2021. ; 18 ( 3 ): 119 – 136 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rishi MA , Ahmed O , Barrantes PJH , et al . Daylight saving time: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement . J Clin Sleep Med. 2020. ; 16 ( 10 ): 1781 – 1784 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brockmann PE , Gozal D , Villarroel L , Damiani F , Nuñez F , Cajochen C . Geographic latitude and sleep duration: a population-based survey from the Tropic of Capricorn to the Antarctic Circle . Chronobiol Int. 2017. ; 34 ( 3 ): 373 – 381 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mindell JA , Sadeh A , Kwon R , Goh DYT . Cross-cultural differences in the sleep of preschool children . Sleep Med. 2013. ; 14 ( 12 ): 1283 – 1289 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chaput JP , Janssen I . Sleep duration estimates of Canadian children and adolescents . J Sleep Res. 2016. ; 25 ( 5 ): 541 – 548 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen W , Adler JL . Assessment of screen exposure in young children, 1997 to 2014 . JAMA Pediatr. 2019. ; 173 ( 4 ): 391 – 393 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Radesky JS , Weeks HM , Ball R , et al . Young children’s use of smartphones and tablets . Pediatrics. 2020. ; 146 ( 1 ): e20193518 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Parent J , Sanders W , Forehand R . Youth screen time and behavioral health problems: the role of sleep duration and disturbances . J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016. ; 37 ( 4 ): 277 – 284 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mileva-Seitz VR , Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ , Battaini C , Luijk MPCM . Parent-child bed-sharing: the good, the bad, and the burden of evidence . Sleep Med Rev. 2017. ; 32 : 4 – 27 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mindell JA , Sadeh A , Wiegand B , How TH , Goh DYT . Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep . Sleep Med. 2010. ; 11 ( 3 ): 274 – 280 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Billingham RE , Zentall S . Co-sleeping: gender differences in college students’ retrospective reports of sleeping with parents during childhood . Psychol Rep. 1996. ; 79 ( 3 Pt 2 ): 1423 – 1426 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bacaro V , Feige B , Ballesio A , et al . Considering sleep, mood, and stress in a family context: a preliminary study . Clocks Sleep. 2019. ; 1 ( 2 ): 259 – 272 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bacaro V , Feige B , Benz F , et al . The association between diurnal sleep patterns and emotions in infants and toddlers attending nursery . Brain Sci. 2020. ; 10 ( 11 ): 891 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. DelRosso LM , Bruni O , Ferri R . Restless sleep disorder in children: a pilot study on a tentative new diagnostic category . Sleep. 2018. ; 41 ( 8 ): zsy102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. DelRosso LM , Jackson CV , Trotter K , Bruni O , Ferri R . Video-polysomnographic characterization of sleep movements in children with restless sleep disorder . Sleep. 2019. ; 42 ( 4 ): zsy269 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. DelRosso LM , Ferri R , Allen RP , et al. International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) . Consensus diagnostic criteria for a newly defined pediatric sleep disorder: restless sleep disorder (RSD) . Sleep Med. 2020. ; 75 : 335 – 340 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. DelRosso LM , Ferri R . The prevalence of restless sleep disorder among a clinical sample of children and adolescents referred to a sleep centre . J Sleep Res. 2019. ; 28 ( 6 ): e12870 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. DelRosso LM , Picchietti DL , Spruyt K , et al. International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) . Restless sleep in children: a systematic review . Sleep Med Rev. 2021. ; 56 : 101406 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gwyther ARM , Walters AS , Hill CM . Rhythmic movement disorder in childhood: an integrative review . Sleep Med Rev. 2017. ; 35 : 62 – 75 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Klackenberg G . Rhythmic movements in infancy and early childhood . Acta Paediatr Scand. 1971. ; 60 ( 224 ): 74 – 83 . [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nevéus T , Cnattingius S , Olsson U , Hetta J . Sleep habits and sleep problems among a community sample of schoolchildren . Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2001. ; 90 ( 12 ): 1450 – 1455 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Petit D , Touchette E , Tremblay RE , Boivin M , Montplaisir J . Dyssomnias and parasomnias in early childhood . Pediatrics. 2007. ; 119 ( 5 ): e1016 – e1025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Laberge L , Tremblay RE , Vitaro F , Montplaisir J . Development of parasomnias from childhood to early adolescence . Pediatrics. 2000. ; 106 ( 1 Pt 1 ): 67 – 74 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Prado IM , Paiva SM , Fonseca-Gonçalves A , et al . Knowledge of parents/caregivers about the sleep bruxism of their children from all five Brazilian regions: a multicenter study . Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019. ; 29 ( 4 ): 507 – 523 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lobbezoo F , Ahlberg J , Raphael KG , et al . International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: report of a work in progress . J Oral Rehabil. 2018. ; 45 ( 11 ): 837 – 844 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Machado E , Dal-Fabbro C , Cunali PA , Kaizer OB . Prevalence of sleep bruxism in children: a systematic review . Dent Press J Orthod. 2014. ; 19 ( 6 ): 54 – 61 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leung AK , Robson WL . Nightmares . J Natl Med Assoc. 1993. ; 85 ( 3 ): 233 – 235 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Falch-Madsen J , Wichstrøm L , Pallesen S , Steinsbekk S . Prevalence and stability of insomnia from preschool to early adolescence: a prospective cohort study in Norway . BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020. ; 4 ( 1 ): e000660 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Calhoun SL , Fernandez-Mendoza J , Vgontzas AN , Liao D , Bixler EO . Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in a general population sample of young children and preadolescents: gender effects . Sleep Med. 2014. ; 15 ( 1 ): 91 – 95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ozgun N , Sonmez FM , Topbas M , Can G , Goker Z . Insomnia, parasomnia, and predisposing factors in Turkish school children . Pediatr Int (Roma). 2016. ; 58 ( 10 ): 1014 – 1022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hysing M , Pallesen S , Stormark KM , Lundervold AJ , Sivertsen B . Sleep patterns and insomnia among adolescents: a population-based study . J Sleep Res. 2013. ; 22 ( 5 ): 549 – 556 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Roberts RE , Roberts CR , Duong HT . Chronic insomnia and its negative consequences for health and functioning of adolescents: a 12-month prospective study . J Adolesc Health. 2008. ; 42 ( 3 ): 294 – 302 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Amaral MOP , de Almeida Garrido AJ , de Figueiredo Pereira C , Master NV , de Rosário Delgado Nunes C , Sakellarides CT . Quality of life, sleepiness and depressive symptoms in adolescents with insomnia: a cross-sectional study . Aten Primaria. 2017. ; 49 ( 1 ): 35 – 41 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dohnt H , Gradisar M , Short MA . Insomnia and its symptoms in adolescents: comparing DSM-IV and ICSD-II diagnostic criteria . J Clin Sleep Med. 2012. ; 8 ( 3 ): 295 – 299 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Liu Y , Zhang J , Li SX , et al . Excessive daytime sleepiness among children and adolescents: prevalence, correlates, and pubertal effects . Sleep Med. 2019. ; 53 : 1 – 8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Joo S , Shin C , Kim J , et al . Prevalence and correlates of excessive daytime sleepiness in high school students in Korea . Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005. ; 59 ( 4 ): 433 – 440 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Meyer C , Ferrari GJ , Barbosa DG , Andrade RD , Pelegrini A , Felden ÉPG . Analysis of daytime sleepiness in adolescents by the pediatric daytime sleepiness scale: a systematic review . Rev Paul Pediatr. 2017. ; 35 ( 3 ): 351 – 360 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sadeh A . Commentary: comparing actigraphy and parental report as measures of children’s sleep . J Pediatr Psychol. 2008. ; 33 ( 4 ): 406 – 407 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hall WA , Liva S , Moynihan M , Saunders R . A comparison of actigraphy and sleep diaries for infants’ sleep behavior . Front Psychiatry. 2015. ; 6 : 19 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gossé LK , Wiesemann F , Elwell CE , Jones EJH . Concordance between subjective and objective measures of infant sleep varies by age and maternal mood: implications for studies of sleep and cognitive development . Infant Behav Dev. 2022. ; 66 : 101663 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]