Abstract

Experiences of racism occur across a continuum from denial of services to more subtle forms of discrimination and exact a significant toll. These multilevel systems of oppression accumulate as chronic stressors that cause psychological injury conceptualized as racism-based traumatic stress (RBTS). RBTS has overlapping symptoms with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with the added burden that threats are constantly present. Chronic pain is a public health crisis that is exacerbated by the intersection of racism and health inequities. However, the relationship between RBTS and pain has not yet been explored. To highlight how these phenomena are interlinked, we present Racism ExpoSure and Trauma AccumulatiOn PeRpetuate PAin InequiTIes – AdVocating for ChangE (RESTORATIVE); a novel conceptual model that integrates the models of racism and pain, and demonstrates how the shared contribution of trauma symptoms (e.g., RBTS and PTSD) maintains and perpetuates chronic pain for racialized groups in the United States. Visualizing racism and pain as “two halves of the same coin,” in which the accumulative effects of numerous events may moderate the severity of RBTS and pain, we emphasize the importance of within-group distinctiveness and intersectionality (overlapping identities). We call on psychologists to lead efforts in applying the RESTORATIVE model, acting as facilitators and advocates for the patient’s lived experience with RBTS in clinical pain care teams. To assist with this goal, we offer suggestions for provider and researcher antiracism education, assessment of RBTS in pain populations, and discuss how cultural humility is a central component in implementing the RESTORATIVE model.

Keywords: cultural humility, pain inequities, antiracism, psychologists, biopsychosocial

In the United States (US), the ongoing crises of racism and health inequities are not merely co-occurring, but instead form a syndemic – a connected set of problems that interact synergistically to make each factor worse and increase the burden of disease (Singer, 2009). Racism is older than the US (Talking About Race, n.d.) and has been identified as the key driver of health inequities (Phelan & Link, 2015). Chronic pain is a significant public health issue characterized by acute health inequities. Latest estimates indicate that 20% of adults in the US have experienced chronic pain in the past 3 months, with rates rising to 30% for older adults (Zelaya et al., 2020). Disparities in pain prevalence and severity (C. M. Campbell & Edwards, 2012), along with pain processing (Burton et al., 2017), have been reported for racialized groups compared to non-Hispanic White groups. False ideas about pain insensitivity (Hoffman et al., 2016) and provider biases (Nelson & Hackman, 2013) contribute to inequitable treatment for pain across health care settings and pain conditions (Letzen et al., 2022; Morais et al., 2022).

Psychologists’ training in social, biological, and psychological processes would seem to uniquely position them to address these syndemic issues. Too often, however, psychologists have been slow to recognize and confront racism within the profession and in their work with clients. This sluggish pace might be explained by the fact that White males of European ancestry primarily created the dominant psychological models and theories (Hergenhahn & Henley, 2013), that the field remains systematically and disproportionately White (Wright et al., 2017), that psychology has perpetuated scientific racism (Winston, 2020), and that psychological practice has largely focused more on individual processes than on the social forces. The history of the discipline and the contemporary environment in which psychology is practiced likely contribute to a failure to acknowledge racism, discomfort discussing oppression, dismissiveness of structural and institutional issues, and in the worst instances, silencing the voices calling for change (Moon & Sandage, 2019). Only recently have organizations and institutions released statements and apologies for their complicity in contributing to systemic inequities, and in the case of the American Psychological Association (APA), admitting that they “failed in its role leading the discipline of psychology” (American Psychological Association, 2021).

Experiences of racism exact a significant physical and psychological toll (Feagin, 2006). A mechanism through which racism affects mental health is racism-based traumatic stress (RBTS) (Carter, 2007b). RBTS theory conceptualizes the significant emotional and mental injury caused by frequent uncontrollable racist experiences and encounters as stress-inducing with the potential to produce traumatic responses (e.g., avoidance, flashbacks) (Carter et al., 2020). An accumulation of these experiences can lead to symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but with the added burden of a socio-political context where threats are constantly present, and the impact of racist experiences are generally invalidated by the dominant White society (Carter, 2007b). Although the conceptualization of traumatic stress remains ingrained in non-Hispanic White perspectives, recent work, such as the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal Socialization Theory (RECAST), provides a framework to understand how adverse, racist events require racialized coping self-efficacy (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019). However, such frameworks have limited integration of structural forces and do not address the impact of RBTS on pain production, exacerbation, or maintenance.

Our article fills this critical gap by introducing the Racism ExpoSure and Trauma AccumulatiOn PeRpetuate PAin InequiTIes – AdVocating for ChangE (RESTORATIVE) model, which conceptualizes the shared biopsychosocial pathways between RBTS and pain. The RESTORATIVE model contends that RBTS is a mechanism sustaining pain inequities on structural, cultural, interpersonal, and intraindividual levels. The RESTORATIVE model is informed by the biopsychosocial models of racism (Clark et al., 1999) and pain (Gatchel et al., 2007). The model focuses on providers reinforcing but not demanding cultural strengths and resilience, examining the effects of RBTS through the lens of intersectionality to consider multiple identities affected by racism, and acknowledging that coping with the interlocking systems of racism in our medical settings causes and exacerbates RBTS. Social inequities occur for most people living with chronic pain (Brown et al., 2018). However, to center the experience of people experiencing the most significant and pervasive pain inequities, the RESTORATIVE model focuses on people from racialized groups and the multilevel factors that systematically increase their pain burden.

We challenge psychologists to recognize and begin examining the oppressive systems that cause individuals’ need to cope with RBTS and ask them to modify their practices and processes as they care for people living with pain. To empower psychologists to work towards this goal, we offer suggestions for clinician and researcher antiracism education, provide tools for the assessment of RBTS in chronic pain populations, describe multidisciplinary approaches and collaboration with scholars and practitioners from complementary disciplines, and discuss cultural humility as a central component in implementing the RESTORATIVE model. Our model has the potential for scientific impact for people living with pain whilst highlighting innovative ways psychologists can interact within healthcare systems to reduce RBTS and chronic pain.

Positionality Statement

Racism and racialization – political and economic processes that ascribe ethnic or racialized identities to a group, often based on phenotypic skin color, and maintain deep-rooted White European hierarchies and power to differentially allocate valued societal resources (Omi & Winant, 2014) – are a global scourge. However, the deep-rooted processes through which racism affects society and institutions in the US, notably anti-Black racism and the forced displacement of Native American Indigenous peoples, cannot simply be generalized to other countries. Moreover, the complexity of the byzantine collection of governmental, non-profit, and for-profit organizations, insurance providers, and hospital systems that systematically disenfranchises racialized groups is unique to US healthcare. Given this distinctiveness and because all of the authors received all or part of their training in the US, we feel we are best equipped to discuss the RESTORATIVE model within a US setting. Further, we have tried to use cultural humility to help us recognize and address our biases as we too, are learning, self-reflecting, and considering how to make our work align in a health equity perspective. The included positionality statement shares how our experiences have contributed to our interpretations regarding our research using individual statements rather than aggregating across demographic, training, and career factors to allow each author to share the elements of their lived experience they feel most applicable to the current work (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Author’s Positionality Statement

| Author | Positionality Statement |

|---|---|

| Anna M. Hood | AMH is a cisgender woman trained as a pediatric clinical health psychologist. Her work focuses on the biopsychosocial model of pain in patients with sickle cell disease. She is a dual British and American citizen perceived as a Black whose grandparents emigrated from Jamaica to the UK as part of the Windrush generation |

| Calia A. Morais | CAM is a licensed clinical psychologist and a pain researcher focused on developing culturally-responsive pain assessment tools and psychosocial treatments. She is a first-generation college graduate, a first-generation immigrant from Peru, and is perceived as Hispanic in the US |

| LaShawnda N. Fields | LNF is a professor of social work whose research centers the voices and experiences of Black women within social work education and their experiences shaped by their intersecting race and gender identities. She is a Black, cisgendered woman from the Midwest |

| Ericka N. Merriwether | ENM is US born and self-identifies as a cisgender Black woman. She has interdisciplinary training as a clinical and translational scientist, is a licensed physical therapist, and has a research focus on obesity-related pain inequities |

| Amber K. Brooks | AKB is a board certified anesthesiologist, pain medicine physician, and health disparities educator and researcher. Her research is focused on pain-related disparities among older adults. She is a Black, cisgender woman raised in the Midwest |

| Jaylyn F. Clark | JFC is a licensed clinical psychologist and pain researcher focused on developing trauma-informed interventions to address health disparities in assessing and treating chronic pain. She is a Black, cisgender woman raised in the rural South |

| Lakeya S. McGill | LSM is a licensed clinical psychologist and postdoctoral fellow focused on promoting equity in pain care among minoritized communities, including adults with sickle cell disease. She is a Black, cisgender woman raised in a working-class family in the rural South. She is also a first-generation college graduate with an invisible disability |

| Mary R. Janevic | MRJ is a community health sciences researcher and social epidemiologist. Her research focuses on developing interventions to address pain inequities among older adults. She is a White, cisgender woman raised in a working-class family in the industrial Midwest |

| Janelle E. Letzen | JEL is a licensed clinical psychologist and pain researcher focused on biopsychosocial mechanisms of pain treatment responses, particularly among marginalized groups. She is the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Argentina and a first-generation college graduate |

| Lisa C. Campbell | LCC is a Black, cisgender woman born and raised in the American South. She is also a licensed clinical psychologist and pain researcher focused on making psychosocial pain management interventions accessible and effective for marginalized populations |

Note. Authors have chosen to share how their experiences have contributed to their interpretations regarding the present research

Racism

More than 50 years after the end of legal segregation and national civil rights legislation, racism persists in the US. Recently, we have seen the normalization of hate speech (Opotow & McClelland, 2020), an increase in hate crimes (Potok, 2017), and the instigation of domestic terrorism threatening racialized groups (Bell, 2019). Almost half of White Americans and nearly one-third of Black Americans hold pro-White bias and a negative bias toward Black Americans (Morin & Rohal, 2015), and 31% of Asian Americans report being subjected to racialized slurs and jokes since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ruiz et al., 2020). However, psychologists often remain hesitant to directly attribute health inequities to racism and draw implicit rather than explicit conclusions about key drivers identified in their work. Racism cannot be eliminated unless it is directly acknowledged. With this goal in mind, we will conceptualize “race” as a social construct that is a multifaceted and multidimensional form of oppression embedded within our social, economic, and cultural systems (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017).

At the macro level, cultural racism works through ubiquitous forces such as the traditional (i.e., television) and social media to instill an ideology that assigns inferiority across language, values, and imagery and reinforces negative stereotypes that racialized groups are less attractive, intelligent, trustworthy, or deserving (D. R. Williams et al., 2019). These incessant messages are adopted and normalized (Bramlett-Solomon & Roeder, 2008). Structural racism is an underlying system through which governmental policies, laws and housing practices are shaped, justified, and perpetuated to reinforce a racialized hierarchy and inequities (Feagin, 2006). Although it legally ended in the US in 1968, residential segregation is a far-reaching example of structural racism that remains fortified by federal, state, and local policies such as mortgage discrimination and redlining (D. R. Williams & Cooper, 2019). Segregation reduces access to high-quality medical care, educational resources, and employment opportunities, along with concentrating poverty. Segregation is responsible for persistent differences in socioeconomic status (D. R. Williams & Cooper, 2019) and reduced access to mental health services for racialized groups (Mensah et al., 2021).

Structural racism encompasses institutional processes and practices resulting from an accumulation of many choices made by many people over time, within the expectations and routines in that setting. Stark evidence for structural racism and adverse health outcomes includes systematically higher morbidity and mortality for Black mothers (J. K. Taylor, 2020). Rather than a condemnation of specific individuals within the system, structural racism acknowledges that decisions made in these institutions are in the context of a society that continues to struggle with racism (House-Niamke & Eckerd, 2020). Structural changes require large-scale, multimodal solutions often viewed as challenging to implement, so, unsurprisingly, discussions often center on interpersonal and individual racism. However, this focus is tied to deeply embedded cultural ideologies of meritocracy (e.g., systems reward the best people) and just-world beliefs (e.g., good things happen to good people) and lacks recognition of the larger structures that facilitate racism (Mathur et al., 2021).

Our institutions tend to consider racialized identity separate from sex, gender, age, and disability status. In her seminal 1989 work “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw first described how aspects of an individual’s identities (i.e., political, social) combine and how racialized identity intersects and overlaps with other individual characteristics to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe this analytic framework and centered her analysis on the experience of Black women as they are “theoretically erased” (Crenshaw, 1990). Within this framework, eliminating prejudice requires focusing on macro interlocking structures of inequities rather than just internal processes. For example, women from racialized communities experience gender bias differently from White women (Settles et al., 2020). Relatedly, it is critical that communities are not treated as an undifferentiated mass and that within-racialized group differences are discussed. These differences can also operate through colorism, which is rooted in colonialism and is discrimination that privileges light-skin over dark-skin color within racialized communities (Hunter, 2007).

Racism-based Traumatic Stress

Racism is a chronic stressor, yet its psychological toll has only been formally studied in recent decades. Early work seeking to characterize the psychological effects of racism used several terms, such as race-based traumatic stress, societal trauma, racist incident-based trauma, and insidious trauma (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005). In the present article, we use the term “racism-based traumatic stress” (RBTS) to acknowledge that this form of traumatic stress is caused by the multi-level system of oppression rather than one’s racialized identity and intrapersonal factors. Many definitions of RBTS have been proposed. This article uses Carter’s (2007) definition of RBTS as “emotional or physical pain or the threat of physical and emotional pain from racism in the forms of racialized harassment (hostility), racialized discrimination (avoidance), or discriminatory harassment (aversive hostility)” (Carter, 2007b). Based on Carter’s scholarship, we conceptualize RBTS as psychological injury wherein the person experiencing racism had their rights unfairly violated and is valid in their emotional response, regardless of whether the RBTS stressor includes overt events, covert acts, and/or vicarious or intergenerational stress (Carter, 2007a).

Across cultural, structural, and interpersonal domains, racism occurs along a continuum from explicit oppression to more subtle forms of discrimination (Bailey et al., 2017). Racism can take the form of microassaults – overt racialized disparagements (e.g., racialized epithets or slurs) (Sue et al., 2007). More commonplace is covert racism – acts that subvert, distort, restrict, and deny racialized groups access to societal privileges and benefits. Harrell et al. (2000) described these types of overt and covert racism as stressors that are often experienced in combination over an individual’s lifespan (Harrell, 2000). Racism-related life events are time-limited and salient experiences unlikely to occur daily (e.g., a Chinese American person is denied entry to a business because of the “Chinese virus’”). Daily microstressors (Sue et al., 2007), on the other hand, are subtle affronts that act as constant reminders that one’s racialized identity is a stimulus in a White dominant society such as microinsults (e.g., telling a Black person, “You are very articulate”), racialized profiling (e.g., a person of Middle Eastern descent is stopped at airport security), microaggressions (e.g., a professor of Mayan descent is mistaken for a janitor) or microinvalidations (e.g., asking an Asian American person “Where are you really from?”) (Coates, 2011).

Chronic-contextual stress is pressure to adapt to and cope with the social, political, and institutional structures of White society (e.g., an Iranian Muslim woman stops wearing her hijab). Collective and vicarious racism life events are collective, group-level events that are not directly observed by the person (e.g., an African American child learns about the 1921 Tulsa massacre), whereas vicarious experiences are events targeting members of one’s racialized group that the individual observes (e.g., a Latinx teenager sees a video of police brutality against a Latinx adult). Finally, transgenerational transmission of group trauma is the long-lasting effects of racism on future generations (e.g., withdrawing federal resources from Indigenous communities).

Scholars have emphasized that RBTS is an understudied and underappreciated form of stress among racialized individuals, leading to trauma reactions similar to those observed in PTSD. PTSD is a constellation of distressing and/or interfering symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, changes in cognition and mood, and changes in arousal and reactivity that emerge after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event (Wilson, 2004). Few studies have examined the degree to which symptoms of RBTS and PTSD overlap; however, preliminary work shows similar symptom profiles, and it is well-established that personal trauma is associated with a greater likelihood of developing PTSD than impersonal trauma (e.g., natural disasters) (M. T. Williams et al., 2018). Overlapping symptoms of RBTS and PTSD include low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, hypervigilance, dissociation, and sleep disturbance (Carter et al., 2020). Although there are similarities in individual responses between PTSD and RBTS, an RBTS framework specifically highlights the external system and processes that cause or reinforce the traumatic event (Carter, 2007b).

Williams and colleagues (2018) proposed an approach for diagnosing RBTS within a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) framework of PTSD. Importantly, they explain that the current DSM-5 constraints on the type of trauma that an individual must experience to be considered for the diagnosis do not pertain to all forms of racism-related stressors, particularly more covert forms that occur regularly (e.g., microaggressions). For this reason, scholars (Butts, 2002) have called for the expansion of DSM-5 criteria to include trauma related to racism and other systems of oppression. Carter cautions, however, that in framing RBTS as a form of PTSD, researchers and clinicians should avoid conceptualizing RBTS as a dispositional matter and instead continue to see it as a form of injury from an external assault.

Pain

The chronic pain epidemic in the US exacts a heavy toll on individuals in the form of morbidity, mortality and disability, and on society with an estimated $560–635 billion in medical costs and lost productivity each year (Simon, 2012). A landmark report concluded that significant improvements are needed in pain prevention, treatment, management, and research (Simon, 2012), and there have been multiple calls and new initiatives for equitable care for people living with chronic pain (Collins et al., 2018). There is also a growing recognition of a significant degree of overlap between many common chronic pain conditions, a phenomenon known as chronic overlapping pain conditions (COPCs) that include, but are not limited to, fibromyalgia, migraine headache, and chronic low back pain (Fillingim et al., 2020). Evidence suggests a higher prevalence of COPCs in older adults who are racialized as Black or Hispanic/Latino/a/x (Plesh et al., 2011). Notably, greater stress, increased negative affect, and higher pain catastrophizing are similar across select COPCs (Fillingim et al., 2020). Regardless of its source, chronic pain is often accompanied by other somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbance, fatigue, and cognitive and physical functioning impairments (Phillips & Clauw, 2013).

The pathophysiology of acute and chronic pain are distinct. For acute pain, healing occurs over the ensuing days to weeks, after resolution of inflammation and cessation of pain signals in the body. Contrarily, for patients with chronic pain, the nervous system will continue to send signals for pain even after the initial injury has resolved. The pathophysiology of chronic pain revolves around this concept of central plasticity of the brain (“neuroplasticity”) in which neural connections are rewired and sensitivity to stimuli changes in response to an initial injury (Fregoso et al., 2019). Significantly, chronic stressors can influence the development of chronic pain (Chapman et al., 2008), with stress modulating pain perception. Previous models have described the mechanisms underlying the transition from acute to chronic pain with cumulative exposure to past traumatic life events (e.g., death of a loved one) (Casey et al., 2008) predictive of chronic pain and negatively valenced emotions heighten the impact of stress on pain (Ahmad & Zakaria, 2015). Pain and stress have also been conceptualized as “two distinguished yet overlapping processes presenting multiple conceptual and physiological overlaps” (Abdallah & Geha, 2017). However, there has been an overreliance on biomedical mechanistic studies to elucidate multifactorial contributors to acute-to-chronic pain transition despite evidence supporting forms of stress as candidate mechanisms for pain chronicity after acute injury (Fregoso et al., 2019). Traumatic events consistent with RBTS are associated with physical and emotional distress, similarities exist between RBTS and PTSD, and evidence links PTSD to pain (see below), yet the association between RBTS and pain has not been theoretically or empirically explored.

The biopsychosocial model accounts for the complex array of biological, psychological, and social factors that shape the experience of chronic pain (Gatchel et al., 2007). Biological factors include the severity of the injury, physiological mechanisms, neurochemistry, genetic predisposition, comorbidities, medication effects, and pain sensitivity; psychological factors include anxiety, depression, and cognitive representations of pain; and social factors include others’ response to pain, environmental demands, and culture (Gatchel et al., 2007). Among Black individuals, in particular, interacting biopsychosocial dimensions are influenced by the toxic and health-damaging conditions produced by structural racism (Baker et al., 2022). For example, Black Americans have increased “allostatic load” (a combination of biomarkers indicating wear and tear on the body) and weathering (i.e., accelerated aging) due to racism, resulting in high rates of multimorbidity and functional impairment that worsen pain’s impact on daily life (Phelan & Link, 2015). Lack of access to medical care and experiences of bias in the health care system means that pain is frequently undertreated and more likely to become severe and disabling. Psychological factors shaped by structural racism include chronic stress resulting from racialized economic disadvantage, experiences of discrimination, and RBTS (J. L. W. Taylor et al., 2018). Social factors influencing pain include social network stressors like mass incarceration of Black Americans that sever social bonds and undermine social support systems (Umberson, 2017).

PTSD and chronic pain commonly co-occur; people living with chronic pain are more likely to have PTSD, and among people with PTSD, pain is highly prevalent and one of the most common physical symptoms (Moeller-Bertram et al., 2012). Proposed models to explain this link include shared vulnerability, in which there are common predisposing factors for both conditions, such as anxiety sensitivity; mutual maintenance, in which symptoms of PTSD and pain exacerbate each other, leading to persistence of both (Otis et al., 2003); and fear avoidance, which contains elements of both prior models, as avoidance behaviors are thought to play a role in perpetuating both pain (by causing activity avoidance leading to depression and disability) and PTSD (in which avoiding thoughts or reminders of things associated with the trauma prevents effective processing of the event) (Otis et al., 2003).

An adjacent body of work provides strong evidence for an association between racialized discrimination and chronic pain, potentially mediated through psychological distress (Brown et al., 2018). We can speculate about similarities and differences between mechanisms underlying the established relationship between PTSD and pain and the possible association between RBTS and pain. There are potential similarities in explanatory models—including shared psychological or physiological vulnerabilities to both the effects of RBTS and pain and the mutual maintenance of symptoms. Potential differences in mechanisms include that the fear avoidance model presents differently in RBTS, as a hallmark of this condition is that avoidance of exposure to acts of racism either directly or vicariously is often impossible, given its pervasiveness. The shared vulnerability model of RBTS and PTSD should recognize that a key vulnerability in RBTS is not intrinsic to the individual but rather is imposed by structural racism. That is, the same factors that give rise to racialized traumatic events that cause RBTS also expose racialized individuals to ongoing risks for developing chronic pain and sustained pain inequities.

Pain-related Coping

Dominant psychological models have traditionally differentiated chronic pain coping strategies as “active and adaptive” (using internal resources to control pain and engaging in activities) vs “passive and maladaptive” (external sources to control pain and/or the avoidance of activities) (Snow-Turek et al., 1996). Within these models, chronic pain coping strategies, such as prayer, have often been classified as a passive strategy, and a meta-analysis found Black people in the USA use prayer as a coping strategy more often than White people (Meints et al., 2016); however, prayer or religiosity are not equivalent to attempting to escape or denial of the pain similar to other guarded responses. Notably, most evidence that active coping strategies contribute to better mood and functioning among people with chronic pain have been developed by and primarily tested on people of White European descent and may not be valid in other cultural traditions (Snow-Turek et al., 1996).

In relation to RBTS, more recent theories highlight that people from racialized groups must manage overt racist encounters and microstressors that can trigger stress-based physiological and psychological responses over time, and they must flexibly choose between “active” (e.g., calling out discriminatory bias) or more “passive” (e.g., being silent) coping strategies depending on the situation often with little warning or time to make a decision, which may differ depending on their racialized coping self-efficacy (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019) and what is needed for optimal for pain coping (Robinson-Lane et al., 2021). For racialized individuals experiencing chronic pain, after months or years of obstacles and not receiving adequate pain treatment regardless of actions they may take (Meints et al., 2016), they may instead use stoicism (i.e., enduring pain or without displaying feelings and without complaint) as a pain coping strategy (Booker, 2016). Therefore, we propose that our field needs to expand our thinking to understand that chronic stressors, subsequent trauma symptoms, and the choice of pain coping strategies are inseparable from structural racism for people from racialized groups living with pain.

The RESTORATIVE Model

In the previous sections, we have detailed the significant impact of racism on the lives of racialized communities and evidence for a relationship between RBTS and PTSD and PTSD and pain, all of which point toward a theoretically and clinically plausible association between RBTS and pain that has not yet been examined. Therefore, we posit Racism ExpoSure and Trauma AccumulatiOn PeRpetuate PAin InequiTIes – AdVocating for ChangE (RESTORATIVE) as a new conceptual model that incorporates the multilevel, combined, and interacting effect of the biopsychosocial factors of racism and pain, along with the shared contribution of RBTS and PTSD symptoms, in maintaining and perpetuating the systematically higher burden of chronic pain in racialized groups. Critically, however, we also contend that systems need to change to remove the multi-domain threat of racism from individuals’ lives. Thus, psychologists and medical providers should incorporate the impact of multilevel racism into their conceptualizations of trauma and design interventions that specifically account for the entrenchment of multi-level generational (e.g., epigenetic), cultural (e.g., television, movies), structural (e.g., laws, segregation), and institutional (e.g., involuntary hospital admissions) racism as a causal factor in RBTS and pain inequities.

The RESTORATIVE model explicitly outlines the considerable overlap and interaction in processes, factors, and symptomatology between racism, specifically RBTS and PTSD, and pain, visualized as “two halves of the same coin.” Our model also incorporates that people from racialized groups must choose from a reservoir of “active and passive” coping strategies during healthcare encounters and when managing pain and argues that through a non-Eurocentric perspective, spirituality is not “passive.” Instead, it may be better conceptualized as “active” for racialized communities who have used their faith to preserve culture, family, and identity (Danoff-Burg et al., 2004). We emphasize the importance of not treating racialized groups as a monolith. For example, although some people from Latinx and Black communities value spirituality, this will differ considerably across and within groups. For those seeking to understand oppression, intersectionality and across and within-group distinctiveness should be at the forefront of implementing this model.

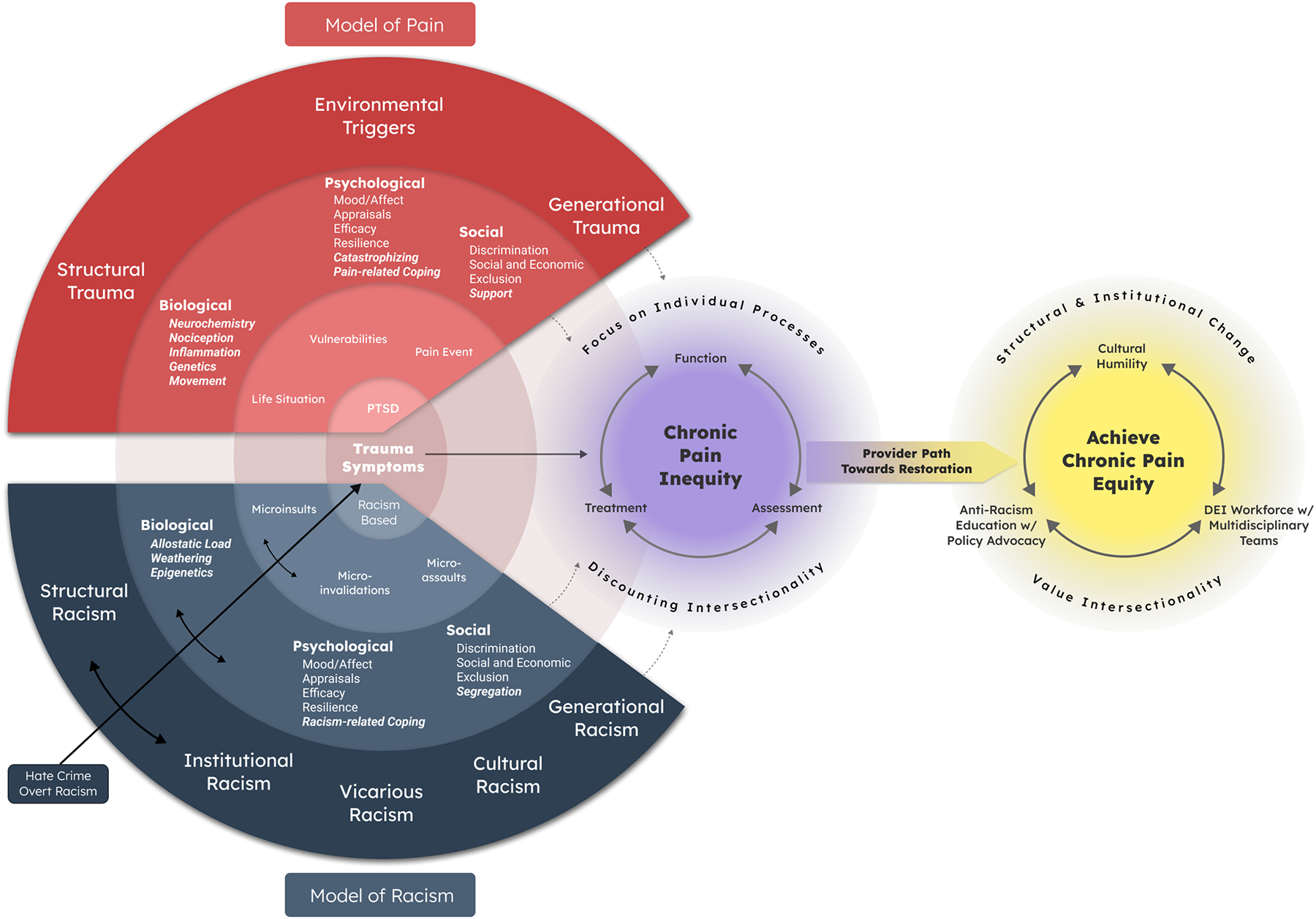

Our RESTORATIVE model (see Figure 1) also helps to elucidate the complexity and interrelatedness of the biopsychosocial factors of racism and pain. In the outer circle, we include the macro-level processes (e.g., vicarious, generational, and structural factors of pain and racism) that shape and are directly tied to biopsychosocial factors in the circle within. For example, social factors of racism and discrimination can produce robust biological (e.g. epigenetic changes, cardiovascular effects, brain impacts) and psychological (e.g. anxiety, depression, vigilance) consequences. Generational trauma (e.g., intergenerational relationship between trauma in parents and chronic pain experienced in children) and structural trauma (e.g., chronic pain of racialized groups discounted or not believed) (Hoffman et al., 2016) are not currently included in our biopsychosocial models of pain; however, we advocate for change that includes a greater focus on these systemic and interacting factors. We theorize that these contributing processes influence how a pain event or racialized microstressor is managed, whether trauma symptoms occur, and how and if pain becomes chronic. The severity of RBTS and pain may be moderated by the cumulative effects of numerous events (Carter, 2007b). Using our model, we advocate for an active engagement in which clinicians acknowledge the contribution of racism, recognize and oppose racism in all domains including their clinical encounters (Jones et al., 2021), and understand that interpersonal interactions with people from racialized groups occur within the context of an “inclined field of prejudice” (Lopez et al., 2000).

Figure 1.

Racism ExpoSure and Trauma AccumulatiOn PeRpetuate PAin InequiTIes – AdVocating for ChangE (RESTORATIVE) model. The models of racism and pain have mostly overlapping constructs, although some have primarily studied with respect to racism or pain (bolded). These complementary factors and symptoms combine and contribute to the progression of trauma symptoms [racism-based traumatic stress (RBTS) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)]. Within and between interactions occur at the model’s macro levels represented in dark gray and dark red (i.e., racism: structural, vicarious, generational; pain: structural, triggers, generational), the biopsychosocial factors within the middle level represented in gray and red, and for the interpersonal and intraindividual levels in the inner level represented in light gray and light red (i.e., racism: microstressors; pain: life situations, vulnerabilities, pain event). These shared contributions maintain and perpetuate chronic pain for racialized groups in the United States, which is further exacerbated by Eurocentric psychological and functional assessment and treatment for chronic pain (represented in purple). A path towards restoration and achieving chronic pain equity for people from racialized groups must be driven by providers (e.g., psychologists, pain scientists, clinicians) and structural change (represented in yellow).

Overall, we propose that our model provides the structure for a deeper understanding and path forward for empirical research and multidisciplinary interventions (quantitative and qualitative designs) assessing the distinctive and overlapping process of racism and pain and the shared contribution of trauma symptoms (racism-based and PTSD). The RESTORATIVE model can drive research that does not just identify disparities but addresses the key drivers. To highlight this more clearly, we next include a fictional case example which illustrates how the different cultural, vicarious, structural, institution factors of the RESTORATIVE model can result in repeated, ambiguous, and unexpected RBTS for an individual from a racialized group influencing their function, healthcare utilization, as well as assessment and treatment, contributing to chronic pain. Although many aspects of the poor-quality care described are, unfortunately, pervasive in pain medicine, we argue these factors compound for people from racialized groups to perpetuate pain inequities.

Case Example

Kim Johnson is a 42-year-old, Black, heterosexual, cisgender woman living with her husband and 2 children (son aged 12, daughter aged 14) in a lower-middle class community on the outskirts of a mid-size city in the southern US. Ms Johnson has close relationships with her family, friends, and church community and draws strength from her faith. She shares a car with her husband, so she often uses public transportation. Intergenerational and structural barriers stem from being raised in a segregated neighborhood surrounded by the aftermath of decades of cordoning off and disinvestment in public services and infrastructure for racialized communities, including limited transportation (i.e., unreliable bus service) and Ms Johnson having to navigate increasingly challenging physical, social, and economic environments in pursuit of healthcare options.

Ms Johnson experiences widespread body pain that started 7 years ago after a minor car accident. She sought medical treatment, but diagnostic tests were unremarkable. However, her lower back pain has progressively worsened over the past five years. Ms Johnson has recent weight gain (BMI > 40) and deconditioning due to sedentary behaviors because of her chronic pain. Her pain interferes with her household responsibilities and social engagement; her comorbid symptoms secondary to pain include sleep disturbances, fatigue, anxiety, and cognitive challenges. Despite this cluster of symptoms, only within the last 8 months has she been diagnosed with fibromyalgia after her primary care physician referred her to a pain clinic. Notably, the diagnosis of fibromyalgia has not facilitated Ms Johnson’s pain care. For example, her primary care physician has frequently commented about her weight and focused on weight management rather than her fibromyalgia diagnosis. These experiences have led to justified mistrust of her primary medical provider.

Similar to many other people from racialized groups in the southern US, Ms Johnson worked in customer service. She was often subjected to microassaults with customers telling her “the topic was too complex for her to understand” and asking for “that colored girl.” During an annual review, she received feedback that her natural hairstyles were unprofessional for the work setting. The physical demands of her job and exposure to RBTS contributed to episodic pain ‘flare-ups’. Ms Johnson was recently terminated from her restaurant supervisor role (after 25 years in the industry) due to the COVID-19 pandemic related closure and lost her health insurance, which has limited her ability to access necessary pain care.

Ms Johnson’s current care plan includes physical therapy, psychological support services, a social work evaluation, and consultation with pain medicine. She is in the process of applying for disability benefits, but her lack of insurance has precluded her from scheduling regular appointments. Despite these delays, Ms Johnson has persisted in seeking care but has encountered numerous racism-related barriers. To illustrate this point, her predominately White MDT has made medical decisions paternalistically instead of using a sharing decision-making process, and her primary care physician did not discuss with her why opioids were not advised to manage her pain or that trialing antidepressants was recommended as part of a multimodal intervention strategy for chronic pain management. Similarly, without an advocate or facilitator in her pain care team, she was not cautioned that she might experience soreness after physical therapy, so only attended once. Across treatment modalities, Ms Johnson has encountered stereotyped views affecting her willingness to engage in health care utilization. She recently presented to the emergency department (ED) for severe pelvic pain. After waiting 8 hours to be seen, her request for pain medications was met with skepticism. Providers questioned if she was “drug-seeking,” a common stereotype leveled at racialized communities seeking pain relief in ED settings. She left without any new recommendations and felt exhausted, disappointed, and helpless regarding her pain management.

Ms Johnson has attended 3 psychology sessions but is unsure if she will return. Her psychologist caused her to feel invalidated when they advised Ms Johnson that her coping strategies (e.g., prayer) are “passive or maladaptive.” She feels pressure to present as a “superwoman” and has not shared her concerns that she is a “failure” as she struggles to fulfill her family roles and cannot return to employment. Her psychologist focused sessions on Ms Johnson’s internalized anxiety symptoms rather than structural factors, and they did not assess RBTS or consider it as a contributor to Ms Johnson’s chronic pain. When Ms Johnson shared her negative experiences in the healthcare system, her psychologist dismissed her concerns and said, “many people have difficulty getting a diagnosis for pain.”

Implementation

The RESTORATIVE model provides an empirical framework for researchers to investigate and develop interventions to assess the relationship between RBTS and pain. Based on our present understanding of factors that can assist with this goal, we offer the following suggestions related to provider and researcher antiracism education, assessment of RBTS in pain populations, and using cultural humility to support the implementation of our model.

Antiracism Education and Clinical Practice

Antiracism is neither colorblindness (a belief that racialized identity does not affect a person’s socially created opportunities) nor passively non-racist. In fact, colorblindness and passivity uphold White supremacy. As the first step in antiracism education, psychologists and the MDTs with whom they engage can develop cultural humility, particularly in working with racialized individuals (Rodríguez et al., 2021). Cultural humility is a lifelong process starting with examining one’s own beliefs and cultural identities, followed by the ongoing self-evaluation to learn about others’ cultures and is a central component for medical care, psychological practice, and implementation of the RESTORATIVE model (Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013). This foundation of self-knowledge is critical for redressing power imbalances. Cultural humility is essential for applying a RBTS lens to eliminating pain care inequities by bridging the gap between the predominantly White pain clinician community and the members of racialized groups whose pain is under-assessed and undertreated (Green et al., 2003). Without cultural humility, we are ill-equipped to address unmet pain care needs of those whose racialized identities position them on the lowest rungs of social hierarchies and determine aspects of their pain experience and the extent to which it will be assessed and treated (L. C. Campbell et al., 2012; Green et al., 2003). An example of cultural humility in implementing the RESTORATIVE model is provided later in this article.

Through antiracism education more broadly, individuals not only recognize racism but actively do something about dismantling it (Cox, 2021). Education and social justice efforts require acknowledgement that racism infects all of our systems, and even if a person does not see themselves as racist, they are likely not engaging in antiracism behaviors. Antiracism moves beyond multicultural competence or diversity and inclusion training as they often fall short in actively assessing and addressing how structural factors, privilege, and underlying White bias impact clinical praxis and an individual’s lived experience (Gray et al., 2020). Instead, antiracism education includes learning the history of the social construction of “race” to promote White hegemony, taking accountability for one’s actions that contribute to systemic racism, and developing skills to actively fight against these actions and structural forces that maintain systemic racism (Corneau & Stergiopoulos, 2012). To achieve the desired outcomes of antiracism practices, psychologists must learn from and engage in community-informed approaches. Health equity has the most significant impact when communities lead and when social indicators of health (e.g., housing, employment) and intergenerational effects are acknowledged and integrated. Antiracism education could easily be embedded as a natural facet of training in the responsible conduct of research and good clinical practice trainings (Buchanan et al., 2021).

The APA, Society for Behavioral Medicine, United States Association for the Study of Pain, and American Academy of Pain Medicine are particularly positioned to develop training and continuing education to support the development of antiracism competencies and changes in diagnostic criteria relevant to RBTS and chronic pain (see Table S1 in the supplemental materials). Fitting well within these competencies at the practitioner and institutional level is trauma-informed care – practices that promote a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing along with acknowledging the impact of trauma on health (Protocol, 2014). Ninety percent of mental health providers never ask about trauma, citing barriers that include embarrassment, pity, repulsion, avoidance or disinterest in the response (Havig, 2008). Thus, RBTS likely receives even less attention. To develop trainees’ antiracism clinical skills, supervisors can use reflexive supervision – encouraging introspection and exploration of how one’s beliefs and values influence the therapeutic relationship (Tang Yan et al., 2021). Further, individuals must recognize their power to advocate and achieve change within their current space (e.g., lab culture), in their work with patients and supervision of trainees, and engaging in social advocacy (e.g., advising policymakers) with or without a leadership position (Chaudhary et al., 2020; Salles et al., 2021). White colleagues can take on some of the heavy lifting in the fight for equity to support the work of scholars from racialized groups (see Table S1) (Hood et al., 2022).

Multidisciplinary Teams and Assessment of RBTS in Chronic Pain

The RESTORATIVE model creates an opportunity for shared knowledge, cross-disciplinary collaborations, and to think deeply about how sociocultural mechanisms of injustice shape inequity and lead to changes in patients’ lives (Mathur et al., 2021). In addition to psychologists, the scholarship of public health scientists and medical anthropologists can be utilized. Due to the biopsychosocial etiology, chronic pain management requires the clinical expertise of a diverse group of professionals to form a MDT (Smith et al., 2019). MDTs should communicate regularly (e.g., weekly) to review cases, ensure continuity of care, and formulate treatment recommendations (Pergolizzi et al., 2013). MDTs can include specialities such as pain medicine (i.e., anesthesiologists) who often serve as the director along with primary care, rheumatology, emergency medicine, nursing, psychiatry, social work, pharmacy, community health, integrative medicine, palliative care, physical therapy, pastoral care, and care partners and coordinators.

Within the MDT, psychologists can act as facilitators. Given the training and tools available to psychologists, they are well-placed to lead the assessment of RBTS. This would streamline the assessment process and limit the retraumatization of patients by having to repeatedly respond to the same traumatic questions. They can also advocate to make sure the patient voice is at the center of all decisions. This goal may be accomplished by using shared decision-making – an approach that is a collaborative process where the healthcare profession and patient work together to achieve informed preferences about their treatment (Elwyn et al., 2012). Shared decision-making supports an effective partnership between patients, families, and clinicians with trust and clear communication (Elwyn et al., 2012). Shared decision-making can help to limit the inherent power imbalance and paternalistic role of the clinician through the use of decision aids (widely available online) to ask the patient, “what matters to you?” In cases where appropriate, psychologists can serve as the link between the traditional culture of the person living with pain and the biomedical culture of medicine. Psychologists could also lead a needs assessment to identify gap areas in treatment for the patient (e.g., massage therapy) and the MDT to ensure that members have the support and training of the institution in skills such as cross-cultural communication, community-and-family focused strategies, and cultural sensitivity.

To foster a therapeutic alliance, psychologists can change the structure of their pre-intake form to be strength or solution focused (e.g., asking “Where would you like to see yourself one year from now?” instead of “How long have you experienced pain?”) (Richmond et al., 2014). This is also a chance for a thoughtful exploration of racialized and cultural identity, acculturation, trauma, and intergenerational family history. Importantly these changes need to be standardized, and questions should be given to all new clients and patients to avoid clinician bias. This information lays the groundwork for an in-depth clinical interview. Many psychologists find discussions about racism uncomfortable and may avoid conversations to prevent a verbal misstep, not considering that the benefits of dialogue outweigh these fears (Mensah et al., 2021). To help allay concerns, standardized instruments may be used to assess RBTS or racism (see Table S1 for examples) (Atkins, 2014). Pain assessment should also be included in the clinical interview along with standardized instruments. Notably, there is a gap in formal measurements of co-occurring RBTS and chronic pain; research is needed to develop such instruments for clinical practice to advance the RESTORATIVE model. However, clinicians can still document and discuss the overlapping symptoms between RBTS and chronic pain with their patients.

Cultural Humility in Implementation of the RESTORATIVE Model in our Case Example

Using the case example described above, the psychologist treating Kim Johnson may not have developed enough awareness of their history and beliefs to acknowledge racism or its traumatic effects (Helms, 1990). Rather than assuming Ms Johnson was “fine” because she did not mention racism directly, with more self-reflection, they may have acknowledged that Ms Johnson used avoidance because the therapeutic relationship was not one of mutual respect and trust. Ms Johnson’s psychologist had an opportunity to acknowledge her resiliency, whilst recognizing the real and harmful effects of years of cumulative chronic adversities. Some people respond to chronic stressors through resilience, but resilience, in turn, can contribute to weathering and allostatic load in high-risk environments (Bryant & Anderson, 2021). Practicing cultural humility requires the capacity to sit in discomfort and bear witness to the emotional pain that may be beyond personal experience or that one is unwilling to acknowledge (Butts, 2002). Intolerance of discomfort can draw a clinician toward intellectualizing the experience of racism rather than acknowledging the emotional harms (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005).

Cultural humility could have helped bring greater awareness of how the traumatic effects of racism shaped and exacerbated Ms Johnson’s chronic pain (Helms et al., 2012). Had this foundation been established, Ms Johnson’s psychologist could have begun discussing racism early in the therapeutic relationship to explore reactions and racism-related coping (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019) and shared racialized trauma self-care tools (see Table S1). When discussing coping, Ms Johnson’s psychologist could have worked to understand how faith and prayer were active strategies to cope with pain and discussed meaningful ways Ms Johnson could maintain her community ties and fulfill her spiritual needs (e.g., volunteering at her church) and that supporting Ms Johnson’s cultural value of familism (i.e., warm and close family relationships) might reduce RBTS and the extent of Ms Johnson’s chronic pain (Corona et al., 2019). Through these practices, Ms Johnson’s psychologist could work honestly and collaboratively to establish a shared understanding of the role of RBTS in the pain experience and integration into the multimodal pain treatment plan where indicated.

Ms Johnson’s psychologist would then have been optimally positioned to provide structured guidance to the MDT to address Ms Johnson’s functional decline, disability, and increased social isolation. Specifically, they could have shared with the MDT that Ms Johnson chronic microassaults (e.g., critiques of her natural hairstyle) at her previous customer service position and microinvalidations (e.g., questioned as “drug-seeking”) within the current healthcare system work similarly to contribute to Ms Johnson’s RBTS and pain experience as they are both examples of structural racism. Further, a legacy of generational racism (i.e., unreliable transportation) affects Johnson’s ability to attend appointments, so the MDT could have discussed ways that they could connect services (e.g., psychology, physical therapy appointments) on the same day and utilize social work to assist Ms Johnson with navigating the healthcare system and determining if she was eligible for transportation costs. Ms Johnson values and preferences should be central in any decision making process whilst acknowledging that racialized bias is pervasive and manifests in patient-provider interactions reducing communication. One way to streamline communication could be to use a decision navigator for Ms Johnson to create a personalized summary report, including questions she could ask the MDT (DeRosa et al., 2021). Finally, although cultural humility is a starting point for building rapport and delivering meaningful care, the RESTORATIVE model could be used to develop pain interventions with greater and equitable impact for individuals from racialized groups.

Conclusion

In 2007, Carter charged the research community with a responsibility that there “is the need for trauma researchers to consider racial–cultural contexts,” and yet we have fallen woefully short in this endeavor. We originally intended to propose a model focused on treatment and intervention for RBTS and pain, drawing on a rich literature addressing this critical health inequity. However, although scholars – predominantly from racialized groups – have done exemplary work, no theoretical model linking RBTS and pain has been formally proposed or empirically evaluated in research, and chronic pain disparities persist for racialized groups in the US. Therefore, 15 years later, we answer Carter’s call with the novel RESTORATIVE model as a framework to help guide research in this area. Psychologists can lead efforts to investigate and collect data to examine the shared contribution of trauma symptoms (e.g., RBTS and PTSD) that maintain and perpetuate higher chronic pain levels and incorporate the combined, interacting, and multilevel effects of the biopsychosocial factors of racism and pain into their conceptualizations of pain disparities. Moreover, psychologists can more intentionally engage and collaborate with scholars with complementary expertise (e.g., anthropologists, sociologists) to enhance theoretical models of racism and discrimination and to propose potential solutions to our current problems.

Although the RESTORATIVE model describes how cultural, structural, generational, and vicarious racism relate to individuals from racialized groups’ pain experience, we emphasize that most components of the model require a change from psychologists and medical providers in their education, assessment, and practice to make an impact on patient care. We believe that psychologists are uniquely placed to facilitate expansive changes within their MDTs and institutions to advocate for patient needs, center the community voice in decision-making, and support health with awareness of structural influences. Clinicians’ labor has to be supported through structural changes within institutions and organizations (e.g., APA), including funding to create culturally-responsive standardized assessments, reflexive protocols and clinical guidelines that consider structural factors and the influence on adherence and healthcare utilization, and diagnostic criteria that include external factors and RBTS. More broadly, greater inclusion of psychologists in pain MDTs both within and outside of large, academic tertiary care centers is a pressing need. Related to this drive, training and recruitment of psychologists currently systematically excluded from the profession (e.g., people from racialized identities or who are cognitively diverse) need to increase significantly as outcomes improve when the MDT better reflects the population it serves. We are not naïve and understand that challenges require a willingness from individuals and institutions to engage in cultural humility and self-reflection. However, fostering empathy and wanting more meaningful lives for patients is why most people join the healthcare profession. Thus, eliminating the ongoing marginalization of people from racialized groups in healthcare should be a clinical-standard imperative.

There are limitations to the RESTORATIVE model as some connections have not been empirically tested; however, the model can provide a blueprint for future empirical research (including qualitative methods such as ethnography) to assess the magnitude and directionality of associations among model components. For example, we ask the field to test whether higher levels of RBTS predict worse chronic pain or does worse chronic pain predict capacity for coping with RBTS? Standardized and validated instruments are available for both constructs, and new research can help develop instruments that capture their co-occurrence. However, even with these testable hypotheses, before critical considerations of feedback loops, potential moderators and mediators, intersectionality, and how the results may differ or identify shared commonalities for racialized groups (e.g., Black, Latinx, Indigenous Peoples), they have not yet been explored, likely due to many of the structural factors outlined in this paper. Once a relationship has been established, funding mechanisms that include time to co-produce and implement patient stakeholder input (Janevic, 2021) are necessary to assess longitudinal interacting processes. However, we believe that implications for the RESTORATIVE model in understanding the co-occurrence of RBTS and pain are high if the scope, frequency, and intensity of effort required to withstand racism challenge all of us to reckon with the depth and breadth of its harms honestly.

Supplementary Material

Public Significant Statement:

Chronic pain is systematically more severe and disabling, yet undertreated, among racialized individuals. The Racism ExpoSure and Trauma AccumulatiOn PeRpetuate PAin InequiTIes – AdVocating for ChangE (RESTORATIVE) model posits that biopsychosocial mechanisms of racism-based traumatic stress and PTSD interact with the pain experience and create these inequities. Psychologists are well-positioned to lead multidisciplinary efforts advancing knowledge and interventions in this area to improve the wellbeing of racialized people living with pain.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joshua Maddux at the University of Cincinnati for his assistance with visualizing the RESTORATIVE conceptual model.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Funding sources include the following: 5P30AG059297-04S1 (NIH/NIA, Morais); 1U24AR076730-01(NIH/NIAMS), R24DA055306 (NIH/NIDA), & 5UL1 TR001420-07 (NIH/NCATS, Brooks); 5T32HD007414 (NIH/NICHD, McGill); R01-NR020442 (NIH/NINR), R01-AG071511 (NIH/NIA), U01-TR003409 (NIH/NCATS), U19 AR076734 NIH/ NIAMS), U45-ES006180-29 (NIH/NIEHS), & 5K01AG050706 (NIH/NIA, Janevic)

References

- Abdallah CG, & Geha P (2017). Chronic pain and chronic stress: two sides of the same coin? Chronic Stress, 1, 2470547017704763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad AH, & Zakaria R (2015). Pain in times of stress. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 22(Spec Issue), 52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2021). APA apologizes for longstanding contributions to systemic racism. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/10/apology-systemic-racism

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins R (2014). Instruments measuring perceived racism/racial discrimination: Review and critique of factor analytic techniques. International Journal of Health Services, 44(4), 711–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, & Bassett MT (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, Janevic MR, & Booker SQ (2022). Chronic Pain and the Movement Toward Progressive Healthcare. In Berger Z (Ed.), Health for Everyone: A Guide to Politically and Socially Progressive Healthcare (pp. 19–26). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J (2019). The resistance & The Stubborn But Unsurprising Persistence of Hate and Extremism in the United States. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 26(1), 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ (2016). African Americans’ perceptions of pain and pain management: A systematic review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(1), 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett-Solomon S, & Roeder Y (2008). Looking at race in children’s television: Analysis of Nickelodeon commercials. Journal of Children and Media, 2(1), 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TT, Partanen J, Chuong L, Villaverde V, Griffin AC, & Mendelson A (2018). Discrimination hurts: the effect of discrimination on the development of chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine, 204, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, & Ocampo C (2005). Racist incident–based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33(4), 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, & Anderson LA (2021). Revisioning the Concept of Resilience: Its Manifestation and Impact on Black Americans. Contemporary Family Therapy, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan NT, Perez M, Prinstein MJ, & Thurston IB (2021). Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how science is conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated. American Psychologist, 76(7), 1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton EF, Suen SY, Walker JL, Bruehl S, Peterlin BL, Tompkins DA, Buenaver LF, Edwards RR, & Campbell CM (2017). Ethnic differences in the effects of naloxone on sustained evoked pain: A preliminary study. Diversity and Equality in Health and Care, 14(5), 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts HF (2002). The black mask of humanity: Racial/ethnic discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 30(3), 336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, & Edwards RR (2012). Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Management, 2(3), 219–230. 10.2217/pmt.12.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Robinson K, Meghani SH, Vallerand A, Schatman M, & Sonty N (2012). Challenges and opportunities in pain management disparities research: Implications for clinical practice, advocacy, and policy. The Journal of Pain, 13(7), 611–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007a). Clarification and purpose of the race-based traumatic stress injury model. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007b). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, Kirkinis K, & Johnson VE (2020). Relationships between trauma symptoms and race-based traumatic stress. Traumatology, 26(1), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Casey CY, Greenberg MA, Nicassio PM, Harpin RE, & Hubbard D (2008). Transition from acute to chronic pain and disability: a model including cognitive, affective, and trauma factors. Pain, 134(1–2), 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CR, Tuckett RP, & Song CW (2008). Pain and stress in a systems perspective: reciprocal neural, endocrine, and immune interactions. The Journal of Pain, 9(2), 122–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary VB, Berhe AA, Housden N, Maiden M, & Kleanthous C (2020). Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. PLOS COMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGY, 13(7), Article: e1005652. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:eb2b1133-2a14-42d9-9dcc-04280f067628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates RD (2011). Covert racism: Theories, institutions, and experiences. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, Koroshetz WJ, & Volkow ND (2018). Helping to end addiction over the long-term: the research plan for the NIH HEAL initiative. Jama, 320(2), 129–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneau S, & Stergiopoulos V (2012). More than being against it: Anti-racism and anti-oppression in mental health services. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(2), 261–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona K, Campos B, Rook KS, Biegler K, & Sorkin DH (2019). Do cultural values have a role in health equity? A study of Latina mothers and daughters. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JM (2021). When Color-conscious Meets Color-blind: Millennials of Color and Color-blind Racism. Sociological Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar]

- Danoff-Burg S, Prelow HM, & Swenson RR (2004). Hope and life satisfaction in Black college students coping with race-related stress. Journal of Black Psychology, 30(2), 208–228. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R, & Stefancic J (2017). Critical race theory. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeRosa AP, Grell Y, Razon D, Komsany A, Pinheiro LC, Martinez J, & Phillips E (2021). Decision-making support among racial and ethnic minorities diagnosed with breast or prostate cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, & Rollnick S (2012). Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J (2006). Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression Routledge. New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, Sanders AE, Rathnayaka N, Maixner W, & Slade GD (2020). Associations of psychologic factors with multiple chronic overlapping pain conditions. J Oral Facial Pain Headache, 34, s85–s100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregoso G, Wang A, Tseng K, & Wang J (2019). Transition from acute to chronic pain: evaluating risk for chronic postsurgical pain. Pain Physician, 22(5), 479–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, & Turk DC (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DM, Joseph JJ, Glover AR, & Olayiwola JN (2020). How academia should respond to racism. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(10), 589–590. 10.1038/s41575-020-0349-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, & Tait RC (2003). The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Medicine, 4(3), 277–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism related-stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havig K (2008). The health care experiences of adult survivors of child sexual abuse: A systematic review of evidence on sensitive practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9(1), 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE (1990). Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, & Green CE (2012). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Traumatology, 18(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenhahn BR, & Henley T (2013). An introduction to the history of psychology. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, & Oliver MN (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood AM, Booker SQ, Morais CA, Goodin BR, Letzen JE, Campbell LC, Merriweather EN, Aroke EN, Campbell CM, Mathur VA, & Janevic MR (2022). Confronting Racism in All Forms of Pain Research: A Shared Commitment for Engagement, Diversity, and Dissemination. The Journal of Pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House-Niamke S, & Eckerd A (2020). Institutional Injustice: How Public Administration Has Fostered and Can Ameliorate Racial Disparities. Administration & Society, 0095399720979182. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M (2007). The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Janevic MR (2021). Making Pain Research More Inclusive: Why and How. The Journal of Pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letzen JE, Mathur VA, Janevic MR, Burton MD, Hood AM, Morais CA, Booker SQ, Campbell CM, Aroke EN, Goodin BR, Campbell LC, & Merriweather EN (2022). Confronting racism in all forms of pain research: Reframing Designs. The Journal of Pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SJ, Gariglietti KP, McDermott D, Sherwin ED, Floyd RK, Rand K, & Snyder CR (2000). Hope for the evolution of diversity: On leveling the field of dreams. In Handbook of hope (pp. 223–242). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Trost Z, Ezenwa MO, Sturgeon JA, & Hood AM (2021). Mechanisms of injustice: what we (don’t) know about racialized disparities in pain. PAIN. https://journals.lww.com/pain/Fulltext/9000/Mechanisms_of_injustice__what_we__don_t__know.97847.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meints SM, Miller MM, & Hirsh AT (2016). Differences in pain coping between black and white Americans: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain, 17(6), 642–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah M, Ogbu-Nwobodo L, & Shim RS (2021). Racism and mental health equity: history repeating itself. Psychiatric Services, appi-ps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller-Bertram T, Keltner J, & Strigo IA (2012). Pain and post traumatic stress disorder–review of clinical and experimental evidence. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SH, & Sandage SJ (2019). Cultural humility for people of color: Critique of current theory and practice. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 47(2), 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Morais CA, Aroke EN, Letzen JE, Campbell CM, Hood AM, Janevic MR, Mathur VA, Merriweather EN, Goodin BR, Booker SQ, & Campbell LC (2022). Confronting Racism in Pain Research: A Call to Action. The Journal of Pain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin R, & Rohal M (2015). Exploring racial bias among biracial and single-race adults: The IAT. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SC, & Hackman HW (2013). Race matters: Perceptions of race and racism in a sickle cell center. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 60(3), 451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omi M, & Winant H (2014). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Opotow S, & McClelland SI (2020). Theorizing hate in contemporary USA. [Google Scholar]

- Otis JD, Keane TM, & Kerns RD (2003). An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 40(5), 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi J, Ahlbeck K, Aldington D, Alon E, Coluzzi F, Dahan A, Huygen F, Kocot-Kępska M, Mangas AC, & Mavrocordatos P (2013). The development of chronic pain: physiological CHANGE necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 29(9), 1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, & Link BG (2015). Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips K, & Clauw DJ (2013). Central pain mechanisms in rheumatic diseases: future directions. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 65(2), 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesh O, Adams SH, & Gansky SA (2011). Racial/ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. Journal of Orofacial Pain, 25(1), 25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potok M (2017). The year in hate and extremism. Intelligence Report, 162(Spring), 36–62. [Google Scholar]

- Protocol ATI (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Rockville, USA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond CJ, Jordan SS, Bischof GH, & Sauer EM (2014). Effects of solution-focused versus problem-focused intake questions on pre-treatment change. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 33(1), 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Lane SA, Hill-Jarrett T, & Janevic MR (2021). Ooh, You Got to Holler Sometime”: Pain Meaning and Experiences of Black Older Adults. In van Rysewyk S (Ed.), Meanings of Pain – Volume III: Vulnerable or Special Groups of People. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, & Washington JC (2021). Dismantling Anti-Black Racism in Medicine. American Family Physician, 104(6), 555–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz NG, Horowitz JM, & Tamir C (2020). Many Black and Asian Americans say they have experienced discrimination amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Salles A, Arora VM, & Mitchell K-A (2021). Everyone Must Address Anti-Black Racism in Health Care: Steps for Non-Black Health Care Professionals to Take. JAMA, 326(7), 601–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles IH, Warner LR, Buchanan NT, & Jones MK (2020). Understanding psychology’s resistance to intersectionality theory using a framework of epistemic exclusion and invisibility. Journal of Social Issues, 76(4), 796–813. [Google Scholar]

- Simon LS (2012). Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 26(2), 197–198. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M (2009). Introduction to syndemics: A critical systems approach to public and community health. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Faux SG, Gardner T, Hobbs MJ, James MA, Joubert AE, Kladnitski N, Newby JM, Schultz R, & Shiner CT (2019). Reboot online: a randomized controlled trial comparing an online multidisciplinary pain management program with usual care for chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 20(12), 2385–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow-Turek AL, Norris MP, & Tan G (1996). Active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain, 64(3), 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talking About Race. (n.d.). National Museum of African American History and Culture. Retrieved March 28, 2021, rom https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race