Abstract

A straightforward and scalable approach to a previously unreported class of cyclic hypervalent Br(III) species capitalizes on the anodic oxidation of aryl bromide to dimeric benzbromoxole that serves as a versatile platform to access a range of structurally diverse Br(III) congeners such as acetoxy-, alkoxy-, and ethynyl-λ3-bromanes as well as diaryl-λ3-bromanes. The synthetic utility of dimeric λ3-bromane is exemplified by photoinduced Minisci-type heteroarylation reactions and benzylic oxidation.

Hypervalent halide reagents are an indispensable part of the organic synthesis tool kit. Among hypervalent halides, bromine(III) reagents possess superior reactivity to that of iodine(III) counterparts owing to stronger electrophilicity and better nucleofugality of the bromanyl moiety.1 The unmatched reactivity of λ3-bromanes has allowed for the development of a series of unprecedented synthetic transformations, e.g., an unusual Hofmann rearrangement of sulfonamides,2 a rare Bayer–Villiger-type oxidation of open-chain aliphatic aldehydes,3 the oxidative coupling of alkynes and primary alcohols to conjugated enones,4 and the regioselective C–H functionalization of nonactivated alkanes.5 Recently, the application of diaryl-λ3-bromanes in catalysis6 and cycloaddition reactions7 was also reported. Notwithstanding these application examples, the remarkable synthetic potential of λ3-bromanes appears to be unexploited due to challenges associated with their preparation. Thus, high oxidation potentials of aryl bromides (e.g., 2.0 V vs Ag/0.01 M AgNO3 for PhBr in CH3CN)8 and poor stability of the resulting bromine(III) species complicate the direct two-electron oxidation by chemical oxidants, a method that is routinely employed for the synthesis of iodine(III) counterparts from iodoarenes.9

In 1984, Frohn demonstrated that the challenging direct oxidation of Br(I) to Br(III) species could be circumvented by a ligand exchange reaction between a suitable Br(III) source such as BrF3 and arylsilane to afford difluoro-λ3-bromane 1 (eq 1, Figure 1).10 Since then, the unstable and moisture-sensitive Frohn’s reagent 1 has served as a key starting material for the synthesis of various Br(III) species,11 including bench-stable imino-λ3-bromane 2.12 Recently, the latter was employed by Miyamoto as the starting material in the preparation of a new series of λ3-bromanes such as 3 and 4 (eq 1, Figure 1).13 Notwithstanding these notable achievements, all of the above-mentioned syntheses rely on the use of BrF3 as the ultimate starting material. Given the high toxicity and extreme reactivity of liquid BrF3 that require specialized equipment and experimental techniques for safe handling, the synthesis of λ3-bromanes is possible only in laboratories that are capable of handling the BrF3 reagent.

Figure 1.

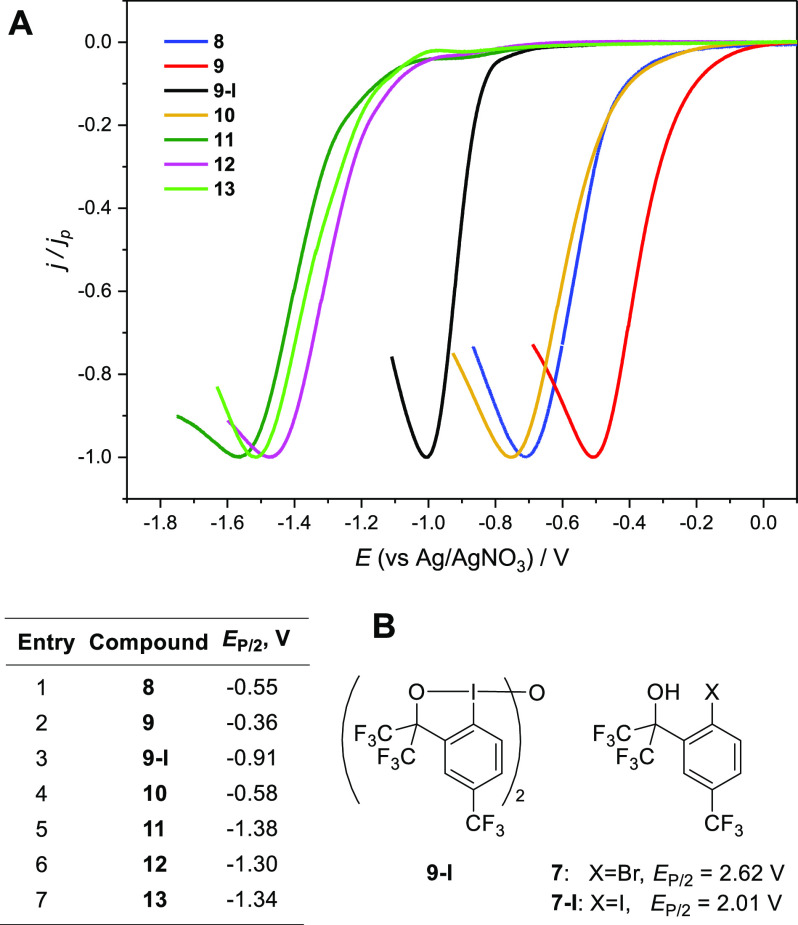

Electrochemical approach to benzbromoxoles 8–13.

In a quest to solve the challenge of λ3-bromane synthesis, we recently disclosed an inherently safe, inexpensive, and straightforward approach to chelation-stabilized hypervalent bromine(III) reagents 6 (Martin’s bromanes) by anodic two-electron oxidation of parent aryl bromides 5 under constant current conditions in an undivided cell (eq 2, Figure 1).14 The suitability of hypervalent Br(III) reagents 6 for the oxidative amination of anilines and the homocoupling of electron-rich arenes was also demonstrated. However, the remarkably stable doubly chelated structure of Martin’s bromanes 6 limits their application in reactions involving ligand exchange at the hypervalent Br(III) center, e.g., functional group transfer reactions.15 Herein, we report on the further development of an anodic oxidation methodology for the synthesis of benzbromoxoles 8 and 9. Notably, λ3-bromane 9 is a stable crystalline material that serves as a platform for the synthesis of benzbromoxoles with various ligands at the exocyclic position such as acetoxy-λ3-bromane 10, phenyl-λ3-bromane 11, alkynyl-λ3-bromane 12, and tert-butoxy-λ3-bromane 13 (eq 3, Figure 1). Electrochemical properties of all synthesized hypervalent Br(III) species 8–13 are also disclosed together with representative synthetic application examples, as shown below.

The published conditions for the electrochemical generation of bromine(III) species 6(14) (glassy carbon as the working electrode and platinum foil as the counter electrode in a TBA-BF4/HFIP electrolyte; current density j = 10 mA cm–2, passed charge equivalents 2F) were used as the starting point for the anodic oxidation of aryl bromide 7 (Table S1, SI). NMR spectra of an electrolyzed solution of 7 in HFIP (with an added equal volume of CHCl3-d) revealed the presence of starting aryl bromide 7 (77% conversion) together with a new product (70% NMR yield) that could be isolated from the electrolysis mixture by aqueous workup and separated from the unreacted 7 by reversed-phase chromatography.16 A structure of hypervalent bromine(III) reagent 8 was assigned on the basis of NMR and MS data (Figure 2). λ3-Bromane 8 is a crystalline material that could be stored at −18 °C (freezer) for 8 weeks. It is stable in organic solvents such as CHCl3-d (τ1/2 = 96 h) and MeCN-d3 (τ1/2 = 168 h) at room temperature. The stability of 8 is notable, given that the electrochemically generated HFIP-containing hypervalent iodine(III) species were insufficiently stable to be isolated in a pure form.17 Optimization of the anodic oxidation conditions (increase in current density to 20 mA cm–2 and passed charge equivalents to 2.5F) allowed us to isolate λ3-bromane 8 in 57% yield. (For an overview of the optimization experiments, see Table S1 in the SI.)

Figure 2.

Synthesis of λ3-bromanes 8–13. Stability was measured in a 0.02 M solution at room temperature. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability, with hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg) for λ3-bromane 9: Br1–O2, 2.034(2); Br1–O1, 1.9240(16); Br1–C7A, 1.931(3); O1–Br1–O2, 173.63(8); Br1–O1–Br1′, 114.32(14); O2–Br1–C7A, 83.06(10); C7A–Br1–O1, 90.73(9); and Br1–O2–C3–C3A, 1.4(3). Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg) for diaryl-λ3-bromane 11: Br1–O2, 2.365(2); Br1–C6, 1.933(2); Br1–C5, 1.959(2); C6–Br1–O2, 176.7(1); C6–Br1–C5, 98.76(10); O2–Br1–C5, 78.1(1); and Br1–O2–C3–C4, −8.8(2). For a discussion of crystalline state structures of dimeric λ3-bromane 9 and diaryl-λ3-bromane 11, see the Supporting Information.

With the optimized electrolysis conditions in hand (Figure 2), the postelectrolysis conversion of relatively unstable 8 into an easier-to-handle λ3-bromane was addressed by the exchange of the 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropoxy ligand for acetate. Gratifyingly, the addition of AcOH to the electrolysis mixture followed by concentration and extractive workup afforded crystalline acetate 10 (Figure 2) that was stable at −18 °C for more than 2 months. The corresponding trifluoroacetate-containing λ3-bromane IM1 was also observed by NMR when 8 was reacted with TFA in CHCl3-d. However, attempted isolation of trifluoroacetyl-λ3-bromane IM1 unexpectedly delivered crystalline dimer 9, whose structure was assigned by NMR and MS methods and confirmed by X-ray analysis (Figure 2). Presumably, λ3-bromane IM1 undergoes ligand exchange with water to form transient IM2 that readily condenses into dimer 9.18 Importantly, bench-stable dimer 9 can be stored at 4 °C for 4 months without any decomposition. The superior stability of crystalline 9 compared to that of λ3-bromanes 8 and 10 renders dimer 9 the most suitable product of the anodic oxidation reaction. Accordingly, additional optimization of electrolysis conditions (replacement of TBA–BF4 with water-miscible TEA–BF4 to ease the extractive removal of supporting electrolyte) combined with the acidic aqueous workup allowed for the scaling up of the electrolysis to furnish 2.42 g (61% yield from 7) of dimeric λ3-bromane 9 in a single run (Figure 2).

Easy-to-handle, stable, and crystalline dimeric λ3-bromane 9 served as a key starting material for the synthesis of a series of bromine(III) congeners 10–13 (Figure 2). Thus, the treatment of 9 with acetic anhydride in the presence of catalytic TMS-OTf (10 mol %) afforded acetoxy-λ3-bromane 10. The reaction of 9 with alkynylsilane and stoichiometric BF3·OEt2 furnished β-(triisopropylsilyl)ethynyl-λ3-bromane 12.19 Notably, both 10 and 12 turned out to be sufficiently stable (Figure 2) to be purified by reversed-phase column chromatography.20 Crystalline diaryl-λ3-bromane 11 was also readily obtained from 9 and phenyl trimethylsilane in the presence of stoichiometric BF3·OEt2, and its structure was proven by X-ray analysis.21 Dimer 9 can be converted back to alkoxy-λ3-bromane 8 simply by dissolution in HFIP. Finally, activation with TMS-OTf was required for the reaction of dimeric λ3-bromane 9 with tert-BuOH to afford tert-butoxy-λ3-bromane 13 (Figure 2).

Electrochemical properties of the 7/8 redox couple and reduction potentials of λ3-bromanes 9–13 were studied with cyclic voltammetry (CV) in MeCN or HFIP and 0.1 M NBu4BF4 as an electrolyte, a glassy carbon working electrode, and a Ag/0.01 M AgNO3 reference (E0 = −87 mV vs Fc/Fc+ couple).22 Bromide 7 exhibits a single irreversible anodic feature with a half-peak potential (EP/2 = 2.62 V; see Figure 3B and the SI),23 which is higher than that of aryl bromide 5 (R=CF3; EP/2 = 2.54 V), a precursor of Martin’s bromane.14 As anticipated, the corresponding iodide 7-I is oxidized at a considerably lower potential (EP/2 = 2.01 V; see Figure 3B).24 A CV study of the cathodic reduction (Figure 3A and the SI) showed that each of the λ3-bromane 8–13 exhibits a single irreversible feature, indicating that electron transfer is followed by a rapid chemical step. Of note, the reduction potentials of λ3-bromanes 8–13 span a relatively wide range from −0.36 to −1.38 V with dimer 9 possessing the highest half-peak potential of −0.36 V (Figure 3A), which is comparable to that of Martin’s bromane 6 (R=CF3; EP/2 = −0.37 V).14b λ3-Bromanes 8 and 10 are not as easy to reduce (EP/2 = −0.55 and −0.58 V, respectively), while λ3-bromanes 11–13 are reduced at even lower potentials (EP/2 = −1.38, −1.30, and −1.34 V, respectively) than are required for λ3-iodane 9-I (EP/2 = −0.91 V; Figure 3A). Interestingly, the reduction potentials are highly sensitive to the electronic properties of ligands at the Br(III) center as evidenced by the remarkable 0.79 V difference between half-peak potentials for structurally related HFIP- and tert-butoxy-substituted benzbromoxoles 8 and 13 (Figure 3A). Overall, the electrochemical reduction of benzbromoxoles is relatively difficult as it proceeds at negative potentials; therefore, λ3-bromanes 8–13 could be considered to be weaker SET oxidants than hypervalent iodine(III) reagents such as widely used PIFA and Koser’s reagent PhI(OH)OTs (EP/2 = −0.33 and +0.14, respectively; see the SI, p S23). In the meantime, λ3-bromane 9 (EP/2 = −0.36 V) is a much stronger SET oxidant than the analogous λ3-iodane 9-I (EP/2 = −0.91 V), so considerable SET oxidizing ability is anticipated for hitherto unreported bromine(III) analogs of Koser’s reagent and PIFA.25

Figure 3.

(A) Background and iR drop-corrected linear sweep voltammograms (LSV) of λ3-bromanes 8–13 and λ3-iodane 9-I (c = 1 mM) were recorded at 100 mV·s–1 in MeCN. (B) Oxidation half-peak potentials EP/2 are for bromide 7 and iodide 7-I in HFIP (c = 5 mM).

Despite the comparable reduction potentials of λ3-bromanes 8–10 and Martin’s reagent 6 (Figure 3A), benzbromoxoles 8–10 are considerably less stable than the doubly chelated λ3-bromane 6. For example, the thermolysis of dimer 9 in benzene at 80 °C for 2 h generated a 4:1 mixture of reduction product 7 and ketone 14, respectively, together with biphenyl (Figure 4A). Possibly, λ3-bromane 9 undergoes homolytic cleavage of the exocyclic Br–O bond13,26 to generate a pair of radicals IM3 and IM4 that abstract a hydrogen atom from benzene, leading to Br(III) intermediate IM2 and bromide 7, respectively (Figure 4A). Subsequent homolysis of the Br–O bond in IM2 leads to 7 via radical IM4. Alternatively, IM2 may also dimerize into 9. A competing decomposition pathway for oxygen-centered radical IM4 apparently involves β-scission to form ketone 14 and a CF3 radical, which upon reaction with benzene produced trifluorotoluene (observed in the reaction mixture by 19F NMR and GC–MS assays). An alternative mechanistic scenario would involve the SET reduction of λ3-bromane 9 by benzene. We regard this as a less likely scenario because dimer 9 is a weaker oxidant than PIFA (EP/2 = −0.33; see the SI), which requires activation by a Lewis acid to effect the SET oxidation of electron-rich arenes.27 Furthermore, no signs of decomposition were observed for doubly chelated λ3-bromane 6 (R=CF3) in benzene at 80 °C even after 18 h. Given the virtually similar reduction potentials for the relatively unstable dimer 9 and stable Martin’s bromane 6 (R=CF3), SET oxidation could be ruled out in favor of homolytic cleavage of the exocyclic Br–O bond as the underlying mechanism for thermal decomposition. Notably, clean conversion of dimeric λ3-bromane 9 to bromide 7 was observed upon light irradiation at 365 nm under ambient temperature within 1 h.

Figure 4.

Reactivity of λ3-bromane 9. aThe yield of 15 was determined by 1H NMR using mesitylene as an internal standard and was calculated based on λ3-bromane 9. bReaction conditions: heterocycle (0.5 mmol), 9 (0.5 mmol), TFA (2.5 mmol), and THF (3 mL); c0.6 mmol of 9; d0.8 mmol of 9; e0.6 mmol of 9, 1:1 cyclohexane/EtOAc (3.0 mL); fheterocycle (0.5 mmol), 9 (0.6 mmol), TFA (0.5 mmol), 1:1 formamide/EtOAc (3.0 mL); g7 h; and h2.5 mmol of TFA, 3 h.

The propensity for the homolytic Br–O bond cleavage renders dimeric λ3-bromane 9 a convenient source of electrophilic radicals for application in hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions28 such as benzylic oxidation29 (Figure 4B) and photoinduced Minisci-type heteroarylations (Figure 4C).30 Indeed, indane was readily oxidized to 1-indanone 15 at 40 °C under oxygen in the presence of dimer 9. Likely, the oxidation is initiated by the abstraction of a benzylic hydrogen atom by radical intermediate IM3 or IM4 to produce the corresponding benzyl radical26c that undergoes autoxidation with dioxygen. λ3-Bromane 9 is also suitable for late-stage oxidative functionalization of complex natural products and pharmaceuticals, as demonstrated by the benzylic oxidation of natural diterpene leelamine (dehydroabietylamine) and antidepressant citalopram to the corresponding ketones 16 and 17 (Figure 4B). Notably, doubly chelated Martin’s bromane 6 and λ3-iodane 9-I were completely inefficient as initiators of alkane aerobic oxidation reactions. Dimeric λ3-bromane 9 also effected the cross-dehydrogenative Minisci-type alkylation of heterocycles with THF and amidation with formamide upon light irradiation at 365 nm (Figure 4C).31 Both alkylation products 18–21 and amides 22–25 were readily formed in 38–98% yields within 1 h at room temperature.32 It should be noted that alkylation product 18 was isolated in only 8% yield (at 10% conversion of the starting 4-methyl quinoline) when dimeric λ3-iodane 9-I was employed. Possibly, the higher reactivity of λ3-bromane 9 as compared to that of λ3-iodane 9-I can be attributed to a lower BDE for the Br–O bond. Importantly, recovery of aryl bromide 7 (98% in the formation of ketone 15 and 94% in the synthesis of quinoline 18) followed by electrochemical oxidation allowed for multiple reuses of λ3-bromane 9 reagent in benzylic oxidation and photoinduced Minisci-type heteroarylations. Further studies to expand the application scope of λ3-bromanes 8–13 are ongoing in our laboratory.

In summary, we have disclosed an efficient, reliable, and inexpensive methodology toward a previously unreported class of cyclic hypervalent bromine(III) species. Our approach capitalizes on the anodic oxidation of chelating ortho-substituent-containing aryl bromide to a dimeric benzbromoxole derivative under constant current conditions in an undivided cell. Easy-to-handle, stable, and crystalline dimeric benzbromoxole serves as a versatile platform to access a wide range of structurally diverse bromine(III) congeners such as acetoxy-, alkoxy-, and ethynyl-λ3-bromanes as well as diaryl-λ3-bromanes. All synthesized bromine(III) species are sufficiently stable to be handled under ambient conditions and purified using standard techniques such as column chromatography. The electrochemical oxidation can be easily scaled-up to afford gram quantities of the dimeric benzbromoxole derivative in a single batch. Cyclic voltammetry studies indicate that oxygen- and carbon-ligand-containing benzbromoxoles are relatively difficult to reduce with potentials spanning a range from −0.36 to −1.38 V. In the meantime, benzbromoxoles are prone to homolysis of the exocyclic Br–O bond under elevated temperatures as well as upon photoexcitation at 365 nm. Hence, the cyclic λ3-bromanes are suitable sources of electrophilic oxygen-centered radicals in, for example, hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions such as Minisci-type amidation and cross-dehydrogenative alkylation as well as benzylic oxidation. Importantly, the recovery of aryl bromide postreaction followed by electrochemical oxidation allowed for multiple reuse of the λ3-bromane reagent. Overall, we believe that the disclosed methodology is a breakthrough in the preparation of λ3-bromanes, a hitherto difficult-to-access class of hypervalent halide species of unmatched reactivity and remarkable application potential in organic synthesis and pharmaceutical chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Latvian Science Council grant LZP-2021/1-0595. The authors thank Dr. Sergey Belyakov from the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis for X-ray crystallographic analysis and Dr. Igors Klimenkovs from the University of Latvia for DSC and TGA measurements.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00405.

Experimental procedures, analytical and spectroscopic data for new compounds, copies of NMR spectra, and X-ray crystallographic data for λ3-bromanes 9 and 11 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Winterson B.; Patra T.; Wirth T. Hypervalent Bromine(III) Compounds: Synthesis, Applications, Prospects. Synthesis 2022, 54, 1261–1271. 10.1055/a-1675-8404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Miyamoto K.Chemistry of Hypervalent Bromine. In PATAI’S Chemistry of Functional Groups; Rappoport Z., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, U.K., 2018; pp 1–25. [Google Scholar]; c Farooq U.; Shah A.-H. A.; Wirth T. Hypervalent Bromine Compounds: Smaller, More Reactive Analogues of Hypervalent Iodine Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1018–1020. 10.1002/anie.200805027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai M.; Okada T.; Tada N.; Yoshimura A.; Miyamoto K.; Shiro M. Difluoro-λ3-Bromane-Induced Hofmann Rearrangement of Sulfonamides: Synthesis of Sulfamoyl Fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (24), 8392–8393. 10.1021/ja903544d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai M.; Yoshimura A.; Miyamoto K.; Hayashi S.; Nakanishi W. Hypervalent λ3-Bromane Strategy for Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation: Selective Transformation of Primary Aliphatic and Aromatic Aldehydes to Formates, Which Is Missing in the Classical Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 9236–9239. 10.1021/ja104330g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai M.; Yoshimura A.; Mori T.; Nishi Y.; Hirobe M. Difluoro-λ3-Bromane-Induced Oxidative Carbon–Carbon Bond-Forming Reactions: Ethanol as an Electrophilic Partner and Alkynes as Nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3742–3743. 10.1021/ja801097c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai M.; Miyamoto K.; Kaneaki T.; Hayashi S.; Nakanishi W. Highly Regioselective Amination of Unactivated Alkanes by Hypervalent Sulfonylimino-λ3-Bromane. Science 2011, 332, 448–451. 10.1126/science.1201686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y.; Ishikawa S.; Mino T.; Sakamoto M. Bromonium Salts: Diaryl-λ3-Bromanes as Halogen-Bonding Organocatalysts. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2519–2522. 10.1039/D0CC07733J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzi M.; Ali Abdine R. A.; De Abreu M.; Wencel-Delord J. Cyclic Diaryl λ 3 -Bromanes: A Rapid Access to Molecular Complexity via Cycloaddition Reactions. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9047–9052. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg N. L.; Weinberg H. R. Electrochemical Oxidation of Organic Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1968, 68, 449–523. 10.1021/cr60254a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt E. A.; Olofsson B. Synthesis of a Range of Iodine(III) Compounds Directly from Iodoarenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 3690–3694. 10.1002/ejoc.201100360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Frohn H. J.; Giesen M. Beitrage zur chemie des bromtrifluorids 1. Teil pentafluorphenylbrom(III)difluorid und -bis (trifluoracetat). J. Fluorine Chem. 1984, 24, 9–15. 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)81292-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Frohn H. J.; Giesen M. Contributions to the Chemistry of Bromine Trifluoride Part 3. Electronic Influences on the Fluorine—Aryl Substitution Reaction of Bromine Trifluoride with Monosubstituted Phenyltrifluorosilanes. J. Fluorine Chem. 1998, 89, 59–63. 10.1016/S0022-1139(98)00087-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ochiai M.; Nishi Y.; Goto S.; Shiro M.; Frohn H. J. Synthesis, Structure, and Reaction of 1-Alkynyl(Aryl)-λ3-Bromanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15304–15305. 10.1021/ja038777q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ochiai M.; Nishi Y.; Mori T.; Tada N.; Suefuji T.; Frohn H. J. Synthesis and Characterization of β-Haloalkenyl-λ3-Bromanes: Stereoselective Markovnikov Addition of Difluoro(Aryl)-λ3-Bromane to Terminal Acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10460–10461. 10.1021/ja051690f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ochiai M.; Tada N.; Murai K.; Goto S.; Shiro M. Synthesis and Characterization of Bromonium Ylides and Their Unusual Ligand Transfer Reactions with N-Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9608–9609. 10.1021/ja063492+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai M.; Kaneaki T.; Tada N.; Miyamoto K.; Chuman H.; Shiro M.; Hayashi S.; Nakanishi W. A New Type of Imido Group Donor: Synthesis and Characterization of Sulfonylimino-λ3-Bromane That Acts as a Nitrenoid in the Aziridination of Olefins at Room Temperature under Metal-Free Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12938–12939. 10.1021/ja075811i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K.; Saito M.; Tsuji S.; Takagi T.; Shiro M.; Uchiyama M.; Ochiai M. Benchtop-Stable Hypervalent Bromine(III) Compounds: Versatile Strategy and Platform for Air- and Moisture-Stable λ3-Bromanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9327–9331. 10.1021/jacs.1c04536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sokolovs I.; Mohebbati N.; Francke R.; Suna E. Electrochemical Generation of Hypervalent Bromine(III) Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 15832–15837. 10.1002/anie.202104677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mohebbati N.; Sokolovs I.; Woite P.; Lõkov M.; Parman E.; Ugandi M.; Leito I.; Roemelt M.; Suna E.; Francke R. Electrochemistry and Reactivity of Chelation-stabilized Hypervalent Bromine(III) Compounds. Chem.–Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202200974. 10.1002/chem.202200974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li Y.; Hari D. P.; Vita M. V.; Waser J. Cyclic Hypervalent Iodine Reagents for Atom-Transfer Reactions: Beyond Trifluoromethylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4436–4454. 10.1002/anie.201509073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hari D. P.; Caramenti P.; Waser J. Cyclic Hypervalent Iodine Reagents: Enabling Tools for Bond Disconnection via Reactivity Umpolung. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 3212–3225. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anodic oxidation of bromide 7 analogs possessing MeO and Cl substituents instead of CF3 returned only the starting aryl bromides, whereas the electrochemical oxidation of a nonsubstituted analog of 7 (H instead of CF3) led to a complex mixture of unidentified products. Studies to unravel the role of arene electronics in the anodic oxidation of aryl bromides are ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

- a Nishiyama S.; Amano Y. Effects of Aromatic Substituents of Electrochemically Generated Hypervalent Iodine Oxidant on Oxidation Reactions. Heterocycles 2008, 75, 1997. 10.3987/COM-08-11331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Broese T.; Francke R. Electrosynthesis Using a Recyclable Mediator–Electrolyte System Based on Ionically Tagged Phenyl Iodide and 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoroisopropanol. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5896–5899. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Koleda O.; Broese T.; Noetzel J.; Roemelt M.; Suna E.; Francke R. Synthesis of Benzoxazoles Using Electrochemically Generated Hypervalent Iodine. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 11669–11681. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Elsherbini M.; Winterson B.; Alharbi H.; Folgueiras-Amador A. A.; Génot C.; Wirth T. Continuous-Flow Electrochemical Generator of Hypervalent Iodine Reagents: Synthetic Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9811–9815. 10.1002/anie.201904379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallos J.; Varvoglis A.; Alcock N. W. Oxo-Bridged Compounds of Iodine(III): Syntheses, Structure, and Properties of μ-Oxo-Bis[Trifluoroacetato(Phenyl)Iodine]. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1985, 757–763. 10.1039/P19850000757. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A. K.; Tessier R.; Hari D. P.; Waser J. Amphiphilic Iodine(III) Reagents for the Lipophilization of Peptides in Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 17963–17968. 10.1002/anie.202106458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The decomposition of λ3-bromanes 9, 10, and 12 was investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetry methods (SI, pp S16 and S17). The DSC analysis of 9 (heating rate 10 K/min) showed an exotherm from 98 to 146 °C with a total heat release of 160.8 J/g that points to a thermal hazard potential for bromane 9. λ3-Bromanes 10 and 12 are more stable, as evidenced by measured lower decomposition enthalpies of 53.0 and 11.9 J/g, respectively.

- Deposition numbers 2232882 and 2232883 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for λ3-bromanes 9 and 11, respectively. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- Pavlishchuk V. V.; Addison A. W. Conversion Constants for Redox Potentials Measured versus Different Reference Electrodes in Acetonitrile Solutions at 25°C. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 298, 97–102. 10.1016/S0020-1693(99)00407-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidation half-peak potential for 7 in MeCN: EP/2 = 2.67 V. At this potential, acetonitrile undergoes oxidative degradation (SI, p S19).

- For comparison, the oxidation potential for PhI is EP/2 = 1.65 V in MeCN and EP/2 = 1.78 V in HFIP (SI, pp S19 and S20).

- The synthesis of the polyfluorinated Br(III) analog of PIFA has been reported in ref (10a).

- a Amey R. L.; Martin J. C. Identity of the Chain-Carrying Species in Halogenations with Bromo- and Chloroarylalkoxyiodinanes: Selectivities of Iodinanyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 3060–3065. 10.1021/ja00505a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Dolenc D.; Plesničar B. Evidence for Divalent Iodine (9-I-2) Radical Intermediates in the Thermolysis of (Tert-Butylperoxy)Iodanes. An Unusually Efficient Deiodination of o-Iodocumyl Alcohols by Cyclohexyl Radicals1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2628–2632. 10.1021/ja9636404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ochiai M.; Ito T.; Takahashi H.; Nakanishi A.; Toyonari M.; Sueda T.; Goto S.; Shiro M. Hypervalent (Tert-Butylperoxy)Iodanes Generate Iodine-Centered Radicals at Room Temperature in Solution: Oxidation and Deprotection of Benzyl and Allyl Ethers, and Evidence for Generation of α-Oxy Carbon Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 7716–7730. 10.1021/ja9610287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Dohi T.; Ito M.; Yamaoka N.; Morimoto K.; Fujioka H.; Kita Y. Hypervalent Iodine(III): Selective and Efficient Single-Electron-Transfer (SET) Oxidizing Agent. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 10797–10815. 10.1016/j.tet.2009.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Izquierdo S.; Essafi S.; del Rosal I.; Vidossich P.; Pleixats R.; Vallribera A.; Ujaque G.; Lledós A.; Shafir A. Acid Activation in Phenyliodine Dicarboxylates: Direct Observation, Structures, and Implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12747–12750. 10.1021/jacs.6b07999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo L.; Ravelli D. Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT): A Versatile Strategy for Substrate Activation in Photocatalyzed Organic Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2056–2071. 10.1002/ejoc.201601485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi T.; Kita Y. New Site-Selective Organoradical Based on Hypervalent Iodine Reagent for Controlled Alkane Sp3 C–H Oxidations. ChemCatChem. 2014, 6, 76–78. 10.1002/cctc.201300666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. S. J.; Phipps R. J. Recent Advances in Minisci-Type Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13666–13699. 10.1002/anie.201900977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interestingly, the formation of IM1 from 9 and excess TFA was not observed by 1H NMR in the reaction mixture of Minisci-type arylation (SI, p S31).

- Less than 2% of isoquinoline 20 was formed in the absence of 9 after 1 h.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.