Abstract

Objective

Freezing of gait (FOG) is an episodic, debilitating phenomenon that is common among people with Parkinson disease. Multiple approaches have been used to quantify FOG, but the relationships among them have not been well studied. In this cross-sectional study, we evaluated the associations among FOG measured during unsupervised daily-living monitoring, structured in-home FOG-provoking tests, and self-report.

Methods

Twenty-eight people with Parkinson disease and FOG were assessed using self-report questionnaires, percentage of time spent frozen (%TF) during supervised FOG-provoking tasks in the home while off and on dopaminergic medication, and %TF evaluated using wearable sensors during 1 week of unsupervised daily-living monitoring. Correlations between those 3 assessment approaches were analyzed to quantify associations. Further, based on the %TF difference between in-home off-medication testing and in-home on-medication testing, the participants were divided into those responding to Parkinson disease medication (responders) and those not responding to Parkinson disease medication (nonresponders) in order to evaluate the differences in the other FOG measures.

Results

The %TF during unsupervised daily living was mild to moderately correlated with the %TF during a subset of the tasks of the in-home off-medication testing but not the on-medication testing or self-report. Responders and nonresponders differed in the %TF during the personal “hot spot” task of the provoking protocol while off medication (but not while on medication) but not in the total scores of the self-report questionnaires or the measures of FOG evaluated during unsupervised daily living.

Conclusion

The %TF during daily living was moderately related to FOG during certain in-home FOG-provoking tests in the off-medication state. However, this measure of FOG was not associated with self-report or FOG provoked in the on-medication state. These findings suggest that to fully capture FOG severity, it is best to assess FOG using a combination of all 3 approaches.

Impact

These findings suggest that several complementary approaches are needed to provide a complete assessment of FOG severity.

Keywords: Daily-Living Monitoring, FOG Assessment, FOG Severity, Freezing of Gait

Introduction

Freezing of gait (FOG) is an episodic, unpredictable phenomenon that commonly impacts people with Parkinson disease. Up to 70% to 80% of people with Parkinson disease experience FOG, especially in the advanced stages of the disease.1,2 An episode often lasts several seconds or longer and may be described by the affected people as feeling glued to the floor.3 This gait disturbance not only hinders locomotion, but also results in a higher prevalence of depression, decreased functional independence, and reduced quality of life, and has only a limited response to medication.3–6 FOG is the most frequent cause of falls among people with Parkinson disease.7 A full and objective evaluation of FOG is crucial for individually tailored clinical decision making, prognostication,8 and the evaluation of disease progression and the impact of therapies.9

Due to its episodic nature and variable presence, FOG is one of the most difficult gait disturbances to assess in Parkinson disease.9 First, the test environment may play a role. Usually, FOG can be provoked in narrow spaces, while turning,10 or in a dimly lit environment where people cannot use visual feedback to compensate.9 The typical obstacle-free hospital corridors are not ideal for provoking FOG. Second, FOG often disappears when people with FOG shift from an automatic gait control to a more goal-directed one,9 when the person is focused on the walking task, like that which occurs during a clinical exam.9 Third, for practical reasons, people with Parkinson disease are often evaluated on antiparkinsonian medications, although the frequency and severity of FOG are typically greater in the off-medication state.6,11 These issues make it more challenging to evaluate and study FOG using conventional methods.

Three approaches to assess FOG may be used: self-report questionnaires based on an individual’s retrospective rating (eg, FOG occurrence over the past month); performance during FOG-provoking tests, reflecting the individual’s condition at a given point in time12; and unsupervised, home-based monitoring using wearable devices, usually quantifying FOG over 1 to 14 days.9 Self-report has been widely used.9,11,13–15 Advantages of self-report include the ease of administration and the idea that these tests provide the individual’s perspective. However, recent work suggests that the clinometric properties of self-report measures may not be ideal.11,16

To induce and quantify FOG objectively, complex trajectories with turns and obstacles are typically used in FOG-provoking tests.9,17–20 Adding cognitive loading may counteract the positive effect of arousal and increase the likelihood of provoking FOG.21 These tests are typically performed with video registration to document the amount of FOG.12 Clinical observation with video-based FOG analysis has been described as the gold standard for assessing the frequency and severity of FOG.6,22 However, this approach can be quite time-consuming and the interrater reliability is variable, ranging from low to good.6,23,24

A third, emerging approach uses wearable sensors to detect and quantify FOG in the daily-living environment. The advantages of monitoring FOG during daily living include the objective nature of the evaluation and its reflection of actual real-world behavior; the ecological relevance is high. FOG throughout the day and the influence of the medication cycles on FOG can also be evaluated.24 In addition, this approach goes beyond snapshot observations in the clinical or home setting using FOG-provoking tests and allows for measurements that extend over a longer period (eg, 1 week), while participants move unsupervised in their daily-living environment.8 Although such an approach putatively has multiple advantages, relatively little is known about FOG assessed this way and validation can be challenging and incomplete.4,25,26 Moreover, it is not yet known how measures of daily-living FOG relate to self-report and those obtained from FOG-provoking tests (ie, previously validated tests of FOG). The present work was conducted to address these questions.

Therefore, in this cross-sectional study, we sought to evaluate the relationships between these 3 different assessment approaches, focusing on the emerging, daily-living measures of FOG. More specifically, we aimed to assess the correlations between 3 approaches for quantifying FOG severity (ie, daily-living monitoring, self-report, and FOG-provoking, supervised testing, both off and on antiparkinsonian medication) and to gain insight into the construct and content validity of daily-living assessment of FOG using wearables by comparing its performance with previously validated tests of FOG and by assessing its relationship to the responsiveness to levodopa. As noted above, antiparkinsonian medications generally reduce the frequency and severity of FOG.21 Thus, another way of examining FOG is to compare its severity in those who respond to dopaminergic therapy with that in those who do not respond. Therefore, we also sought to compare the participant characteristics and FOG estimates for responders (ie, people who had a good response to dopaminergic medication, with decreased FOG severity while on medication) with those for nonresponders (ie, people who did not have a good response to dopaminergic medication). Finally, to further evaluate the 3 different approaches and their relationship to a previously validated method, we compared the FOG frequency and severity when dividing the group into those with mild and moderate FOG based on the supervised, FOG-provoking tests while off medication as well as based on unsupervised daily-living monitoring.

Methods

The research was conducted at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel and the KU Leuven in Belgium. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of both centers. All participants gave informed written consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki before their participation.

Participants

Baseline data from 28 people with Parkinson disease and FOG who participated in the DeFOG study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03978507) from January to December 2020 were analyzed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All participants completed in-home FOG-provoking tasks, self-report questionnaires, and unsupervised daily-living monitoring for 1 week.

In-Home Supervised FOG-Provoking Tasks

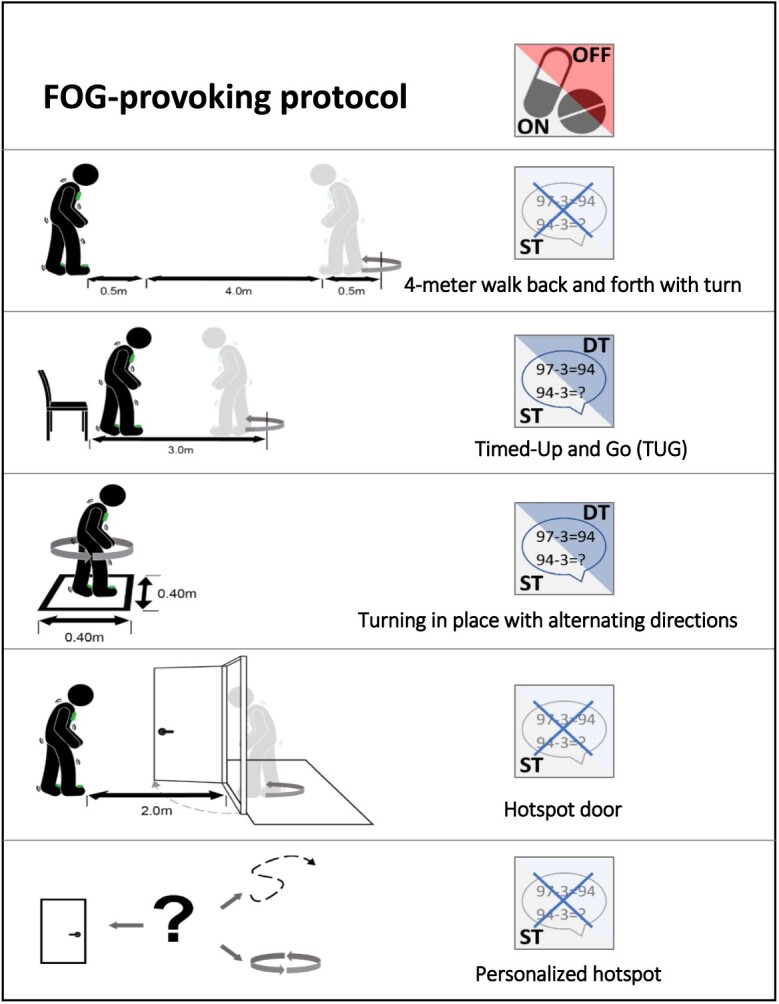

As described elsewhere,27 the previously validated FOG-provoking protocol (Fig. 1) consists of 5 different tests that were carried out in each participant’s home and were adapted and modified from the test originally proposed by Ziegler et al.18 This home-based protocol included a 4-m walk test, back and forth, to measure gait speed and cadence; the Timed “Up & Go” Test, performed in a single-task condition and in a serial-3-subtraction dual-task condition; a turning task, which involved a full 360-degree turn in place, repeated 4 times, with alternating directions in single- and dual-task conditions; walking through narrow-space passages, for which participants were asked to walk 2 m, open a door, pass through the doorway, turn in place, and return to the starting point, typically a bathroom or a toilet; and a personal hot spot, a self-reported area where a participant often experienced FOG.27 The participants were evaluated while off and on dopaminergic medication. Off-state performance was assessed following an overnight withdrawal of medication of at least 12 hours. On the same day, testing was performed again after medication intake when the participant reported that the on-medication state was reached, using a visual analog scale, typically after 1 hour. During that hour, participants completed several questionnaires and had rest breaks, as needed, to avoid fatigue.

Figure 1.

Supervised, in-home tasks provoking freezing of gait (FOG) while off and on dopaminergic medication.27 DT = dual task; ST = single task.

The FOG-provoking protocol was filmed with a video camera and synchronized to annotate freezing episodes. The videos were analyzed offline using the annotation software Elan to determine the percentage of time spent frozen (%TF) as the outcome for each task in 2 centers.28 Independent observers, each with experience in FOG assessments, annotated the videos using rigorous procedures and definitions that were put in place to enhance standardization, consistency, and fidelity.27

Self-Report Questionnaires

The Characterizing Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (CFOG-Q) is a relatively new assessment tool that provides insights into the triggers of freezing.29 The New Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (NFOG-Q) is a widely used, previously validated, and practical screening tool for FOG that measures clinical aspects of FOG within the last month (possible range: 0–28 points).30,31 The CFOG-Q and NFOG-Q were answered while participants took a break between the off and the on states of medicine intake.

Unsupervised Daily-Living Monitoring

FOG during 1 week of unsupervised (ie, no specific instructions other than to carry out a normal routine) daily-living monitoring was assessed with the DeFOG system, which is a further development of the Gait Tutor system.32 This certified medical device was developed by mHealth Technologies, Bologna, Italy. It includes a smartphone and 2 sensors that are placed on the shoes (Fig. 2). The internal measurement units in the sensors consist of a triaxial gyroscope (full scale at ±1000 degrees/s) and a triaxial accelerometer (full scale at ±8 g). Raw internal measurement unit data are transmitted to the smartphone (sampling frequency 200 Hz),27 which results in a battery capacity of about 4 hours. If the battery level becomes low, the system prompts the user to charge the battery. The FOG-detection algorithm enables the automatic and online detection of FOG every 0.5 seconds using a sliding window of 3.2 seconds. The latency between the presence of an episode and the detection is about 1 second.27 Supplementary Figure 1 provides more information.

Figure 2.

Mobile devices including 2 internal measurement units (IMU) and a smartphone, used for unsupervised daily-living monitoring.27

Participants were informed by the assessors at the end of the baseline assessments about the system setup. A detailed user manual and instructional videos were stored on the smartphone, and a printed fact sheet was handed out. Participants were encouraged to use the system as often as possible during their daily activities and to charge the system while sleeping, during lunch, and during other activities done while sitting.27 After 7 days of monitoring, the collected raw signals from the DeFOG sensors and the lower back accelerometer were processed offline with the FOG detection algorithm (using MATLAB version 2021b; The MathWorks, Inc, Natick, MA, USA) to identify FOG events (see Suppl. Material). These FOG events were used to calculate the ratio between the time spent with FOG (sum of the duration of all FOG events of at least 1 second) and the total duration of monitoring done with the system—[(time spent with FOG × 100)/total duration of monitoring]—determining the %TF.

Data Analyses

The data were analyzed using SPSS software version 20 (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The %TF for a single task was calculated by multiplying the time spent frozen by 100 and dividing the result by the duration of the task (see also Suppl. Material). The %TF from the provoking protocol (all tasks) while off or on medication was calculated by summing up the total time spent frozen during all tasks, multiplying by 100, and dividing by the sum of the duration of all tasks. The FOG episodes per hour were calculated by dividing the total number of FOG episodes measured in the observation time. The results from the in-home, FOG-provoking protocol and the questionnaires were tabulated and compared statistically with the output measures of the data collected during the 1 week of daily-living home monitoring using Spearman rank correlations. To better understand the daily-living measures and the relationship between the 3 measurement approaches, we further divided all participants based on the impact of antiparkinsonian medications on FOG in the FOG-provoking protocol (ie, responders and nonresponders), mild and moderate %TF during the provoking protocol while off medication (ie, the gold standard), and the mild and moderate %TF during daily-living activities measured with the DeFOG system. Two groups were compared using parametric and nonparametric tests (due to the nature of the distribution of the measures). Because many of the outcome variables were not normally distributed, we summarized them using the median and interquartile range (IQR). We used Benjamini-Hochberg corrections to account for multiple comparisons; only group differences that remained significant were considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The 28 people were between 57 and 80 years old, had 12.50 years of disease, with disease being relatively advanced, as expected from the inclusion criteria. During the in-home testing while off medication, the %TF of the provoking protocol (all tasks) ranged from 0.4 to 57.9 %TF (Suppl. Fig. 2). A total of 507 FOG episodes were provoked in the off-medication state, compared with 215 while on medication. During off-medication performance, the median value of FOG episodes per hour was 168.74 (IQR = 109.14–283.93), whereas during on-medication performance, the median value was 88.60 (IQR = 0.00–230.93). In the off-medication state, all participants displayed FOG, whereas in the on-medication state, 18 people had a FOG episode. The %TF during on-medication testing ranged from 0.0 to 49.9 %TF. The turning tasks induced the most FOG, both before and after medication intake (Tab. 2). The %TF during the 1 week of unsupervised daily-living monitoring ranged from 0.4 to 5.3 %TF, and the median value was 1.0 %TF. A median of 17.68 (IQR = 10.09–38.85) FOG episodes per hour was recorded during daily-living usage. Participants used the mobile devices for a median of 223.55 (IQR = 182.00–350.42) minutes each day (median across all days), that is, about 4 h/d. This is much more than the median of 82.95 (IQR = 37.27–115.13) minutes that they spent actually walking, as determined using the lower back sensor that was worn continuously throughout the week of monitoring.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 28 Participantsa

| Variable | Median | 25%–75% Percentiles | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, y | 71.00 | 65.25–75.00 | 57.00–80.00 |

| PD duration, y | 12.50 | 7.25–17.75 | 3.00–30.00 |

| LEDD, mg | 815.00 | 539.00–1119.50 | 62.00–2041.50 |

| Severity of PD | |||

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | 2.00 | 1.50–2.00 | 1.50–3.00 |

| MDS-UPDRS I | 13.00 | 9.00–17.75 | 7.00–30.00 |

| MDS-UPDRS II | 21.00 | 17.25–25.00 | 10.00–32.00 |

| MDS-UPDRS III while off medication | 46.50 | 35.25–52.00 | 31.00–55.00 |

| MDS-UPDRS III while on medication | 34.50 | 25.50–40.25 | 10.00–62.00 |

| MDS-UPDRS IV | 4.50 | 3.00–10.00 | 0.00–13.00 |

| Quality of life | |||

| PD Questionnaire, 8-item version | 34.38 | 28.13–40.63 | 6.25–65.63 |

| Life-Space Assessment (n = 24) | 84.00 | 73.50–92.00 | 35.00–120.00 |

| Fear/fall risk | |||

| Parkinson Anxiety Scale | 14.50 | 7.25–19.00 | 2.00–21.00 |

| Falls Efficacy Scale–International | 32.00 | 26.25–39.25 | 19.00–59.00 |

| Cognitive function | |||

| Mini-Mental State Examination, 26-item version | 25.00 | 23.00–26.00 | 21.00–26.00 |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment | 25.00 | 23.75–27.00 | 20.00–29.00 |

| Balance | |||

| Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test | 20.00 | 19.00–22.00 | 15.00–26.00 |

| Severity of freezing of gait | |||

| CFOG-Qb | 24.50 | 17.25–34.75 | 10.00–50.00 |

| NFOG-Qb | 22.00 | 19.25–24.75 | 14.00–28.00 |

| %TF during unsupervised daily-living monitoring | 1.0 | 0.6–2.9 | 0.4–5.3 |

CFOG-Q = Characterizing Freezing of Gait Questionnaire; LEDD = levodopa equivalent daily dose; MDS-UPDRS = Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; NFOG-Q = New Freezing of Gait Questionnaire; PD = Parkinson disease; %TF = percentage of time spent frozen.

As shown on Figure 3, scores on the CFOG-Q and the NFOG-Q were not significantly correlated with each other.

Table 2.

Severity of Freezing of Gait (FOG) During FOG-Provoking Protocol Off and On Medicationa

| Medication State | Parameter | 4-m Walk | TUG, Single Task | TUG, Dual Task | Turning Task, Single Task | Turning Task, Dual Task | Hot Spot, Narrow Space | Personal Hot Spot | Provoking Protocol, All Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off | Median %TF (25%–75% percentiles) | 0.0 (0.0–5.7) | 0.7 (0.0–8.4) | 0.0 (0.0–8.7) | 21.2 (4.9–58.6) | 27.3 (1.1–70.7) | 2.1 (0.0–25.4) | 13.7 (1.0–35.2) | 25.5 (8.6–40.5) |

| No. of FOG episodes | 14 | 20 | 42 | 137 | 162 | 27 | 105 | 507 | |

| No. of participants with FOG | 9 | 14 | 12 | 24 | 21 | 15 | 21 | 28 | |

| On | Median %TF (25%–75% percentiles) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 3.8 (0.0–51.1) | 7.6 (0.0–48.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–5.4) | 4.1 (0.0–24.3) |

| No. of FOG episodes | 2 | 5 | 7 | 95 | 80 | 6 | 20 | 215 | |

| No. of participants with FOG | 2 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 12 | 18 |

%TF = percentage of time spent frozen; TUG = Timed “Up & Go” Test.

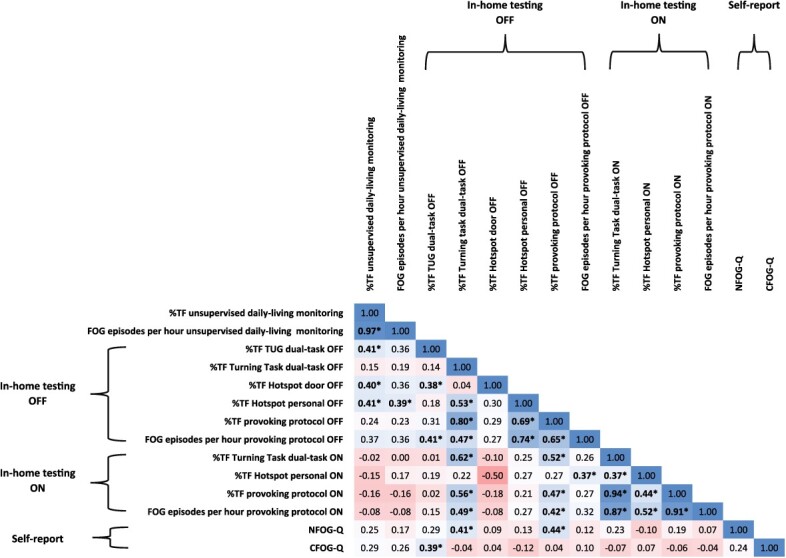

Correlations

Positive correlations between %TF assessed during unsupervised daily living and %TF during 3 tasks of the in-home testing while off medication were observed (Fig. 3). For example, moderate correlations were found between %TF from unsupervised 1 week of daily living, and the %TF during the Timed “Up & Go” Test under the dual-task condition, the hot spot door task, and the personal hot spot task during the FOG-provoking test while off medication (Fig. 3). In contrast, the %TF during provoking tasks performed while on medication was not significantly correlated with the %TF during unsupervised daily-living activities (P > .05).

Figure 3.

Spearman rank correlation of percentage of time spent frozen (%TF) during unsupervised daily-living monitoring and other estimates of freezing of gait (FOG). Similar results were obtained when we adjusted for disease duration or disease severity (ie, Hoehn and Yahr stages). *P ≤ .05. CFOG-Q = Characterizing Freezing of Gait Questionnaire; NFOG-Q = New Freezing of Gait Questionnaire; OFF = off-medication state; ON = on-medication state; TUG = Timed “Up & Go” Test.

The %TF during daily living was not significantly correlated with the NFOG-Q total score (P = .20) or its subscores (part II P = .19; part III P = .45). Similarly, the %TF during daily living was not correlated with the CFOG-Q total score (P = .14) or with its subscores (part II P = .26; part III P = .11). In contrast, the FOG item 3.11 of the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale in the off-medication state was correlated with the %TF (r = 0.44; P = .02) and the number of FOG episodes per hour (r = 0.40; P = .04) during daily living. Further, the levodopa equivalent daily dose was moderately correlated with the %TF (r = 0.43; P = .02) and the number of FOG episodes per hour (r = 0.39; P = .04) during daily living. Participants with a higher dosage of antiparkinsonian medication had higher values of %TF during daily-living activities.

The NFOG-Q total score was correlated with the total %TF during the provoking protocol performed while off medication (r = 0.44; P = .02) and the turning task performed under the dual-task condition while off medication (r = 0.41; P = .03). The Timed “Up & Go” Test under the dual-task condition while off medication (r = 0.39; P = .04) was correlated with the CFOG-Q total score (Fig. 3). Other scores on both self-report questionnaires were not significantly correlated with %TF during the FOG-provoking tests (while off and on medication).

Comparison of Responders and Nonresponders During the Home-Based Supervised Testing

The %TF of all tasks while on medication was subtracted from the %TF of all tasks while off medication to analyze the difference between responders and nonresponders. Fourteen participants exhibited less than 5% improvement (n = 10) or even had worse FOG (n = 4) while on antiparkinsonian medications. The rest of the group (n = 14) improved more than 5% in the tasks after medication intake. The performance of the FOG-provoking protocol was different in responders and nonresponders only in the %TF of the personal hot spot task (P ≤ .001) while off medication (Tab. 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Percentages of Time Spent Frozen in Responders and Nonresponders While On and Off Dopaminergic Medicationsa

| Parameter | Variable | Median (25%–75% Percentiles) for: | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants With Good Improvement While On Medication (>5%) (n = 14) | Participants With Less or No Improvement While On Medication (<5%) (n = 14) | |||

| Participant characteristics and disease severity | Age, y | 70.00 (65.25–73.00) | 71.00 (63.50–75.00) | .93 |

| Sex, % women | 14.3 | 42.9 | .94 | |

| Disease duration, y | 14.00 (9.50–18.00) | 9.50 (6.13–17.00) | .44 | |

| MDS-UPDRS part III while off medicationb | 50.50 (35.25–53.00) | 45.00 (35.00–50.25) | .34 | |

| MDS-UPDRS part III while on medicationb | 37.00 (29.25–44.75) | 32.50 (24.75–38.00) | .48 | |

| MDS-UPDRS III, item 3.11 FOG, while off medicationb | 2.00 (0.00–3.25) | 2.00 (0.00–2.00) | .28 | |

| MDS-UPDRS III, item 3.11 FOG, while on medicationb | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | 1.50 (0.00–2.00 | .55 | |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | 2.00 (1.50–2.13) | 2.00 (1.88–2.00) | .55 | |

| Gait speed during 4-m walk, m/s | 1.15 (1.00–1.23) | 0.94 (0.85–1.14) | .04 | |

| LEDD, mg/d | 832.50 (668.75–1653.75) | 630.00 (311.25–1012.50) | .03 | |

| Unsupervised home monitoring | %TF during monitoring | 2.8 (0.9–3.1) | 0.6 (0.5–1.2) | .01 |

| No. of FOG episodes | 876.00 (420.50–1491.25) | 456.50 (265.75–525.50) | .01 | |

| No. of FOG episodes/h | 35.43 (14.93–43.64) | 11.94 (8.76–22.09) | .02 | |

| Daily usage of home monitoring device, min | 221.90 (167.42–338.50) | 223.55 (191.12–366.79) | .41 | |

| Amount of FOG during supervised FOG-provoking tests (%TF) while off medication | 4-m walk while off medicationc | 2.4 (0.0–20.6) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | .03 |

| TUG, single task, while off medicationc | 2.7 (0.0–20.8) | 0.0 (0.0–6.7) | .20 | |

| TUG, dual task, while off medicationc | 3.86 (0.0–41.9) | 0.0 (0.0–4.4) | .07 | |

| Turning task, single task, while off medicationc | 42.7 (17.9–66.0) | 9.1 (3.3–47.4) | .05 | |

| Turning task, dual task, while off medicationc | 43.2 (19.3–83.6) | 8.4 (0.0–48.2) | .03 | |

| Hot spot, narrow space, while off medicationc | 8.8 (0.0–32.7) | 0.9 (0.0–21.5) | .38 | |

| Personal hot spot while off medicationc | 31.0 (12.3–44.6) | 4.8 (0.0–15.2) | ≤.001d | |

| Total %TF during provoking protocol while off medicationc | 39.5 (17.4–47.6) | 8.8 (3.5–30.8) | .01 | |

| No. of FOG episodes/h while off medication | 259.00 (142.97–320.13) | 154.94 (66.01–180.96) | .01 | |

| Amount of FOG during supervised FOG-provoking tests (%TF) while on medication | 4-m walk while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | .32 |

| TUG, single task, while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | .31 | |

| TUG, dual task, while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | .78 | |

| Turning task, single task, while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–39.8) | 8.9 (0.0–57.8) | .56 | |

| Turning task, dual task, while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–50.3) | 9.6 (0.0–47.6) | .64 | |

| Hot spot, narrow space, while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.5) | .41 | |

| Personal hot spot while on medicationc | 0.0 (0.0–6.9) | 0.0 (0.0–4.7) | .80 | |

| Total %TF during provoking protocol while on medicationc | 3.1 (0.0–3.1) | 6.2 (0.0–38.4) | .38 | |

| No. of FOG episodes/h while on medication | 66.53 (0.00–203.78) | 173.20 (0.00–242.40) | .59 | |

| Self-report questionnaires | New Freezing of Gait Questionnaireb | 23.50 (20.75–26.00) | 20.00 (18.50–24.00) | .04 |

| Characterizing Freezing of Gait Questionnaireb | 27.00 (19.50–37.75) | 22.50 (15.75–33.25) | .39 | |

Unadjusted P values are shown. FOG = freezing of gait; LEDD = levodopa equivalent daily dose; MDS-UPDRS = Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; %TF = percentage of time spent frozen; TUG = Timed “Up & Go” Test.

Reported as a score.

Reported as percentage of time spent frozen.

Statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Comparison of Mild and Moderate Freezing in the Off-Medication FOG-Provoking Protocol

Participants with mild and participants with moderate %TF during the FOG-provoking protocol were similar in age, sex, levodopa equivalent daily dose, gait speed, Hoehn and Yahr staging, and Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III while off and on medication (Suppl. Tab. 2).

While off medication, participants (n = 14) with moderate %TF during the FOG-provoking protocol had more FOG during the turning tasks in the single (P ≤ .001) and dual-task (P ≤ .001) conditions and in the personal hot spot task (P = .02), compared with people (n = 14) with mild %TF. Further, the number of FOG episodes per hour (P = .04) and the %TF of the provoking protocol while off medication (all tasks) (P ≤ .001) were significantly higher in people with moderate FOG. During the tasks performed while on medication, the people with moderate %TF (based on off-medication testing), had more %TF in the turning tasks in single (P = .02) and dual-task (P ≤ .001) as well as in the total %TF (P = .01) (Suppl. Tab. 2).

In contrast, daily-living %TF (P = .93), the number of FOG episodes during daily living (P = .41), and the duration of daily usage of the devices (P = .84) during the unsupervised daily-living monitoring period did not differ significantly between people with mild or moderate %TF based on off-medication testing (Suppl. Tab. 2).

People with mild and moderate %TF based on this classification also did not differ in the total NFOG-Q total score (P = .09) or CFOG-Q total score (P = .57) (Suppl. Tab. 2).

Comparison of Mild and Moderate Freezing in Unsupervised Daily-Living Monitoring

Participants with mild FOG, based on daily-living measures (Suppl. Tab. 2), had fewer FOG episodes during the 1 week daily-living monitoring (P ≤ .001) and fewer FOG episodes per hour (P ≤ .001). Several measures of FOG assessed in the FOG-provoking test while off medication were higher in the individuals who had more daily-living FOG; however, these trends were not significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. Overall, both groups did not differ statistically, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, in participant and disease characteristics, the %TF during the tasks of the provoking protocol while off and on medication, as well as in the total scores of the self-report questionnaires.

Discussion

We compared 3 approaches that have been previously used to quantify FOG among people with Parkinson disease. Both self-report questionnaires were not related to the %TF during 1 week of unsupervised testing. In contrast, the moderate associations between daily-living %TF during 3 different tasks performed in the off-medication state support the utility of these unsupervised daily-living measures. Daily-living freezing measured with the wearable devices was also related to FOG item 3.11 of the Movement Disorders Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale while off medication and with the levodopa equivalent daily dose, as might be expected from a measure of FOG, further supporting the validity of this approach.

The current findings suggest that freezing during daily living is primarily driven by off-medication behavior, even though many daily-living actions are carried out while on medication.6,33 Compared with a supervised assessment, which usually involves relatively few moment sequences, unsupervised free-living might include numerous turns, walking bouts, and transitions like sit-to-stand or bending to pick up an obstacle from the floor that predispose to FOG. Another difference lies in the situation. Whereas the supervised protocol was selected to provoke FOG under optimal situations (eg, reverse white coat syndrome), unsupervised monitoring measures the normal daily routine of the individual.8,34,35 The density of FOG-provoking events in the real world is apparently lower than that seen in the FOG-provoking test. This idea is supported by the higher %TF and number of FOG events found during the provoking protocol while off and on medication, compared with daily-living results. Regardless of the precise reason for this, in the future it may be informative to collect daily-living FOG and to correlate that with the timing and dose of medication intake and with environmental challenges.

Turning in place is an effective trigger to provoke FOG,22,36 as also seen in the %TF and number of FOG episodes (Tab. 2) during the turning tasks while off and on medication. The high percentage of time spent frozen during turning in single and dual-task conditions influenced the total %TF of the provoking protocol. Still, in both states, no correlation to the %TF of the unsupervised daily-living monitoring was found with %TF during turning. These differences between the existing tests and those based on daily living may, in some sense, be desirable as they all enable the capturing of different aspects of the problem.37

The current results demonstrate that %TF collected in the week-long home monitoring did not correlate with self-report scores. This absence parallels other findings.4,23,38 The CFOG-Q was originally developed to quantify heterogeneity in freezing behavior. By calculating the total scores for each section of the assessment, a detailed picture of the FOG experiences of the individual is provided.29 A previous study found a correlation of the CFOG-Q item 2 with the %TF while off medication and a significant association between the total score of section 2 (triggers) with the %TF assessed during motor tasks.29 Our results did not confirm these findings; however, in the future it may be interesting to examine associations between individual items of the CFOG-Q. Mild freezing during walking or other activities of daily life as well as fear of falling may already be felt as very disturbing for the individual and may have led to the dissociations with unsupervised monitoring outcomes.4 The lack of correlations between the subjective and unsupervised FOG assessments (ie, 1 week of home monitoring), suggests that FOG questionnaires may not provide a complete picture of the FOG frequency. Still, it should be considered that the time periods during which FOG was assessed and self-reported were not identical. Nonetheless, self-reports may be useful as screening tools for detecting the overall presence of FOG,38 even though they do not reflect the %TF during daily living monitoring.

Based on all 3 types of assessments that are currently used to evaluate FOG, we might have anticipated moderate to higher correlations between them. However, in contrast to this possibility, relatively few outcomes were strongly associated with each other. This may reflect the idea that the specific constructs and methodologies are capturing different aspects of FOG. In future work, it may be interesting to tease this apart further by examining specific constructs of some of the tests (instead of total scores).

Responders (ie, participants who had less FOG after medication intake during the FOG-provoking test) had a higher number of FOG episodes during the unsupervised daily-living monitoring (Tab. 3). Although these results were not significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons, we speculate that these findings might be related to motor fluctuations induced by dopaminergic medications. Interestingly, when the participants were divided into those with mild freezing and those with moderate freezing, based on %TF during unsupervised daily living, similar results were obtained using correlation analyses. When the participants were divided into those with mild freezing and those with moderate freezing, based on the FOG-provoking-protocol while off medication (ie, the gold standard), self-report total scores did not differ (Suppl. Tab. 2). This strengthens the idea that self-report and objective measures are not simple mirror images of each other.

Findings from the supervised assessments (ie, provoking tests and questionnaires) should be interpreted cautiously, because these results may have limited ecological value8 and may not fully reflect FOG during daily living. Hence, an assessment based on objective and subjective measures may be the best approach to comprehensively assess FOG severity in individuals with Parkinson disease.39 Clinicians should consider the limitations of different FOG outcome measures to accurately assess the severity.11 The relatively new method to measure FOG with wearable devices during daily living may help to improve the management of FOG, without requiring an in-person visit to the clinic.40 When norms for the unsupervised FOG measures are fully established, these data could be helpful in clinical decision making, for on-demand cueing, and for evaluating the impact of different therapies and interventions on FOG.9 However, additional study is needed to evaluate reliability and responsiveness to interventions. Furthermore, ethical issues and concerns about surveillance need to be taken into account when considering this emerging approach.41

In summary, unsupervised daily-living monitoring, self-reported questionnaires, and FOG-provoking tests provide different, complementary evaluation methods. When used together, a relatively complete and informative picture of a person’s FOG severity and how it is perceived emerges. To fully capture FOG severity and its impact, it may be best for researchers to assess FOG using a combination of supervised structured FOG-provoking tests, unsupervised daily-living monitoring with wearable devices, and self-report questionnaires. Until the wearable technology becomes more accessible, physical therapists and other clinicians should consider using self-report questionnaires perhaps along with questions about personal hot spots while observing also the patient as they carry out turns, one of the strongest and most consistent provokers of FOG.

Limitations and Further Research

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size that may have led to type II errors. Given the sample size, the present findings should be viewed cautiously. The cross-sectional design is also a limitation, although we did evaluate, to some degree, responsiveness to antiparkinsonian medications (Tab. 3). Prospective observational and intervention studies with more participants will provide valuable information. Furthermore, combining the movement sensor data with other information (eg, GPS data, weather, medication intake, time of day) may provide additional insights into daily-living FOG, how it changes indoors versus outdoors, and its underlying mechanisms. Another limitation relates to the algorithm used to identify FOG during daily living.

For example, the akinetic type of FOG may be especially challenging to detect. Further, even though participants had rest breaks between in-home off-medication and on-medication testing and individual short sitting breaks, fatigue might have played a role. Also, the median daily usage of the system (smartphone and sensors) during the 7-day monitoring period was about 4 hours, which may initially seem low. However, previous work among people with Parkinson disease suggests that most walk only about 2 hours per day; even among healthy older adults, most people walk less than 4 hours per day.42–45 The recordings from the lower back sensor that was worn continuously during the week of monitoring indicated the participants spent just 83 minutes walking per day, supporting the idea that the smartphone and sensor DeFOG system was worn much more than just during walking. Restrictions due to COVID-19 may also have played a role. Finally, further studies are needed to evaluate different aspects of the validity of measuring FOG during daily-living activities in an unsupervised setting with mobile devices.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Diana Denk, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Talia Herman, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Demi Zoetewei, KU Leuven, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Neurorehabilitation Research Group (eNRGy), Leuven, Belgium.

Pieter Ginis, KU Leuven, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Neurorehabilitation Research Group (eNRGy), Leuven, Belgium.

Marina Brozgol, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Pablo Cornejo Thumm, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Eva Decaluwe, KU Leuven, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Neurorehabilitation Research Group (eNRGy), Leuven, Belgium.

Natalie Ganz, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Luca Palmerini, Department of Electrical, Electronic, and Information Engineering ''Guglielmo Marconi'', University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Nir Giladi, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel; Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; Department of Neurology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Alice Nieuwboer, KU Leuven, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Neurorehabilitation Research Group (eNRGy), Leuven, Belgium.

Jeffrey M Hausdorff, Center for the Study of Movement, Cognition and Mobility, Neurological Institute, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel; Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; Department of Physical Therapy, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center and Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: P. Ginis, T. Herman, A. Nieuwboer, J.M. Hausdorff

Writing: D. Denk, T. Herman, J.M. Hausdorff

Data collection: D. Denk, T. Herman, D. Zoetewei, M. Brozgol, P.C. Thumm, E. Decaluwe

Data analysis: D. Denk, N. Ganz, L. Palmerini

Project management: P. Ginis, A. Nieuwboer, J.M. Hausdorff

Fund procurement: A. Nieuwboer, J.M. Hausdorff

Providing participants: T. Herman, N. Giladi, J.M. Hausdorff

Providing facilities/equipment: A. Nieuwboer, J.M. Hausdorff

Providing institutional liaisons: N. Giladi, A. Nieuwboer, J.M. Hausdorff

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): All authors

Ethics Approval

The research was conducted at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center in Israel and the KU Leuven in Belgium. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of both centers.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Michael J. Fox Foundation (https://www.michaeljfox.org/; Grant ID = 16347).

Clinical Trial Registration

This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03978507).

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Ge H-L, Chen X-Y, Lin Y-X, et al. The prevalence of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease and in patients with different disease durations and severities. Chin Neurosurg J. 2020;6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ehgoetz Martens KA, Peterson DS, Almeida QJ, Lewis SJG, Hausdorff JM, Nieuwboer A. Behavioural manifestations and associated non-motor features of freezing of gait: a narrative review and theoretical framework. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:350–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lord SR, Bindels H, Ketheeswaran M, et al. Freezing of gait in people with Parkinson's disease: nature, occurrence, and risk factors. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mancini M, Shah VV, Stuart S, et al. Measuring freezing of gait during daily-life: an open-source, wearable sensors approach. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2021;18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pelicioni PHS, Menant JC, Latt MD, Lord SR. Falls in Parkinson's disease subtypes: risk factors, locations and circumstances. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herman T, Dagan M, Shema-Shiratzky S, et al. Advantages of timing the duration of a freezing of gait-provoking test in individuals with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2020;267:2582–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Okuma Y, Silva de Lima AL, Fukae J, Bloem BR, Snijders AH. A prospective study of falls in relation to freezing of gait and response fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;46:30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warmerdam E, Hausdorff JM, Atrsaei A, et al. Long-term unsupervised mobility assessment in movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mancini M, Bloem BR, Horak FB, Lewis SJG, Nieuwboer A, Nonnekes J. Clinical and methodological challenges for assessing freezing of gait: future perspectives. Mov Disord. 2019;34:783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schaafsma JD, Balash Y, Gurevich T, Bartels AL, Hausdorff JM, Giladi N. Characterization of freezing of gait subtypes and the response of each to levodopa in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scully AE, Hill KD, Tan D, Clark R, Pua Y-H, de Oliveira BIR. Measurement properties of assessments of freezing of gait severity in people with Parkinson disease: a COSMIN review. Phys Ther. 2021;101:pzab109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nieuwboer A, Giladi N. The challenge of evaluating freezing of gait in patients with Parkinson's disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:S16–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gan J, Liu W, Cao X, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of FOG in Chinese PD patients, a multicenter and cross-sectional clinical study. Front Neurol. 2021;12:568841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Radder DLM, Silva, de Lima AL, et al. Physiotherapy in Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of present treatment modalities. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34:871–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilat M, Ginis P, Zoetewei D, et al. A systematic review on exercise and training-based interventions for freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hulzinga F, Nieuwboer A, Dijkstra BW, et al. The new Freezing of Gait Questionnaire: unsuitable as an outcome in clinical trials? Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barthel C, Mallia E, Debû B, Bloem BR, Ferraye MU. The practicalities of assessing freezing of gait. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016;6:667–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ziegler K, Schroeteler F, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Fietzek UM. A new rating instrument to assess festination and freezing gait in Parkinsonian patients. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Dijsseldonk K, Wang Y, van Wezel R, Bloem BR, Nonnekes J. Provoking freezing of gait in clinical practice: turning in place is more effective than stepping in place. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8:363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pardoel S, Shalin G, Nantel J, Lemaire ED, Kofman J. Early detection of freezing of gait during walking using inertial measurement unit and plantar pressure distribution data. Sensors (Basel). 2021;21:2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dagan M, Herman T, Bernad-Elazari H, et al. Dopaminergic therapy and prefrontal activation during walking in individuals with Parkinson's disease: does the levodopa overdose hypothesis extend to gait? J Neurol. 2020;268:658–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gavriliuc O, Paschen S, Andrusca A, Helmers A-K, Schlenstedt C, Deuschl G. Clinical patterns of gait freezing in Parkinson's disease and their response to interventions: an observer-blinded study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;80:175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris TR, Cho C, Dilda V, et al. A comparison of clinical and objective measures of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reches T, Dagan M, Herman T, et al. Using wearable sensors and machine learning to automatically detect freezing of gait during a FOG-provoking test. Sensors (Basel). 2020;20:4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pardoel S, Kofman J, Nantel J, Lemaire ED. Wearable-sensor-based detection and prediction of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. A review. Sensors (Basel). 2019;19:5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silva de Lima AL, Evers LJW, Hahn T, et al. Freezing of gait and fall detection in Parkinson's disease using wearable sensors: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2017;264:1642–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zoetewei D, Herman T, Brozgol M, et al. Protocol for the DeFOG trial: a randomized controlled trial on the effects of smartphone-based, on-demand cueing for freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2021;24:100817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gilat M. How to annotate freezing of gait from video: a standardized method using open-source software. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019;9:821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ehgoetz Martens KA, Shine JM, Walton CC, et al. Evidence for subtypes of freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2018;33:1174–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giladi N, Shabtai H, Simon ES, Biran S, Tal J, Korczyn AD. Construction of freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2000;6:165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nieuwboer A, Rochester L, Herman T, et al. Reliability of the new freezing of gait questionnaire: agreement between patients with Parkinson's disease and their carers. Gait Posture. 2009;30:459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mazilu S, Blanke U, Hardegger M, et al. GaitAssist: a wearable assistant for gait training and rehabilitation in Parkinson's disease. In: 2014 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Demonstrations (PERCOM WORKSHOPS). IEEE; 2014;135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Evers LJ, Raykov YP, Krijthe JH, et al. Real-life gait performance as a digital biomarker for motor fluctuations: the Parkinson@Home Validation Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Polhemus A, Ortiz LD, Brittain G, et al. Walking on common ground: a cross-disciplinary scoping review on the clinical utility of digital mobility outcomes. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shah VV, McNames J, Mancini M, et al. Laboratory versus daily life gait characteristics in patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, and matched controls. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2020;17:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spildooren J, Vinken C, van Baekel L, Nieuwboer A. Turning problems and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:2994–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Espay AJ, Hausdorff JM, Sánchez-Ferro Á, et al. A roadmap for implementation of patient-centered digital outcome measures in Parkinson's disease obtained using mobile health technologies. Mov Disord. 2019;34:657–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shine JM, Moore ST, Bolitho SJ, et al. Assessing the utility of freezing of gait questionnaires in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller KJ, Suárez-Iglesias D, Seijo-Martínez M, Ayán C. Fisioterapia para la congelación de la marcha en la enfermedad de Parkinson: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Rev Neurol. 2020;70:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Del Din S, Kirk C, Yarnall AJ, Rochester L, Hausdorff JM. Body-worn sensors for remote monitoring of Parkinson's disease motor symptoms: vision, state of the art, and challenges ahead. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11:S35–S47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sim I. Mobile devices and health. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:956–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Del Din S, Galna B, Lord S, et al. Falls risk in relation to activity exposure in high-risk older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:1198–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e219–e228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Benka Wallén M, Franzén E, Nero H, Hagströmer M. Levels and patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior in elderly people with mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2015;95:1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pisal A, Agarwal B, Mullerpatan R. Evaluation of daily walking activity in patients with Parkinson disease. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;30:207–218. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.