Abstract

Camphorsultam-based lithium enolates referred to colloquially as Oppolzer enolates are examined spectroscopically, crystallographically, kinetically, and computationally to ascertain the mechanism of alkylation and the origin of the stereoselectivity. Solvent- and substrate-dependent structures include tetramers for alkyl-substituted enolates in toluene, unsymmetric dimers for aryl-substituted enolates in toluene, substrate-independent symmetric dimers in THF and THF/toluene mixtures, HMPA-bridged trisolvated dimers at low HMPA concentrations, and disolvated monomers for the aryl-substituted enolates at elevated HMPA concentrations. Extensive analyses of the stereochemistry of aggregation are included. Rate studies for reaction with allyl bromide implicate an HMPA-solvated ion pair with a +Li(HMPA)4 counterion. Dependencies on toluene and THF are attributed to exclusively secondary shell (medium) effects. Aided by density functional theory (DFT) computations, a stereochemical model is presented in which neither chelates nor the lithium gegenion serve roles. The stereoselectivity stems from the chirality within the sultam ring and not the camphor skeletal core.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

A survey of scaled procedures used by Pfizer Process over two decades showed that 68% of all C–C bond formations were carbanion-based, and 64% of these involved enolates.1,2 A survey of over 500 academic natural product syntheses revealed that lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) was the most commonly used reagent, which certainly involved a considerable number of lithium enolates.3 Thus, the central importance of lithium enolates in organic synthesis is unassailable.4

We submit that understanding how solvation and aggregation influence enolate reactivity and selectivity also has a niche, but it has been a particularly challenging problem. During a collaboration with the Sanofi-Aventis process group to study β-amino ester enolates (1, Chart 1)5 we happened upon a generalizable protocol6 for determining aggregation states of O–Li species in solution.7 This initiated studies of structure-reactivity-selectivity relationships of synthetically important enolates ranging from simple to functionally complex (Chart 1).8

Chart 1.

Synthetically relevant enolates characterized in solution.5,8

Notably absent from Chart 1 are camphor-based Oppolzer enolates exemplified by lithium enolate 8 in eq 1.9 Highly stereoselective functionalizations using a range of counterions are attributed to transition structures depicted as 10 in which stereocontrol to form 9 stems from endo-face approach to the sultam-based chelates. We describe herein studies of the lithium enolates of type 8, exploring how solvent influences aggregate structure and the mechanism underlying highly stereoselective alkylations. After wading through some strikingly complex aggregation and solvation effects we found that the sulfonyl-based chelates are structurally important but do not influence the stereoselectivity of alkylation. Moreover, neither the lithium counterion nor the camphor methyl moieties influence the stereochemistry. The unglamorous function of the camphor skeleton is to anchor the C–C–C–N dihedral angle in sultam 11. The sulfonyl moiety plays a key and quite unexpected role.

|

(1) |

The bulk of the study focuses on the structures of aryl acetamide-derived enolates and their alkylation.10 While this is logical given the prevalence of pharmaceutical agents with aryl propionate substructures11 and considerable room for further development of their syntheses using the Oppolzer enolates,12 the aryl acetamide-derived enolates are more structurally tractable than their alkyl counter-parts. For the casual readers, the Discussion summarizes the solvent-dependent structures and mechanism of alkylation. For the more structurally and mechanistically inclined readers, the Results section details the challenges and methods for determining solution structure.

Background: structure determination.

Structure and mechanism are in-separably entwined. In 1968, Edwards et al.13 reduced reaction kinetics to a simple (paraphrased) maxim: the rate law provides the stoichiometry of the transition structure relative to the reactants. It offers the empirical formula of the transition structure provided the structures of all reactants are known. Thus, the success of a detailed mechanistic study depends critically on understanding and controlling the structures of the reactants. Having determined hundreds of rate laws over decades, however, we can say with confidence that the challenges posed by structural variability in the reactants are far more vexing than those arising from multiple transition structures.

Seebach, Williard, and others laid important foundations by determining enolate crystal structures showing what might exist in solution.14 Lithium enolate solution structures, however, were elusive owing to the absence of spin-spin coupling in the O–Li linkage that was central to understanding C–Li and N–Li species.15,16,17 Early solution structural studies of enolates employed colligative measurements to obtain average molecular weights of all species in solution inferred from measured solution molalities,18 but these methods are opaque and error-prone owing to the possibility of complex equilibria and undetected impurities. Diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) promoted in organolithium chemistry contemporaneously by Williard19 and Stalke20 shows great promise by providing relative molecular weights of the independent species. While questions remain about the contributions of solvation, aggregate shape, and some odd temperature sensitivities,21,22 DOSY comes into play in this study. A bevy of 2-D NMR spectroscopies can reveal structures of aggregates containing magnetically inequivalent subunits,8e,8f,23 but we had little luck with this approach on the Oppolzer enolates.

The method of continuous variations (MCV) offered us a flexible tool to ascertain the structures of enolates in solution.5–7 An ensemble generated from binary mixtures of constitutionally similar species of unknown aggregation number (An and Bn, eq 2) is monitored by NMR spectroscopy as a function of mole fraction, XA or XB. The number and symmetries of the heteroaggregates attest to the aggregation state. Plotting the relative proportions against measured mole fraction24 with a parametric fit affords a Job plot confirming the assignment (vide infra).7

| (2) |

The application of MCV requires carefully chosen binary mixtures to optimize spectral resolution, which becomes an issue of increasing importance as the aggregation states increase. As we show below, binary mixtures of antipodes of a single enolate—scalemic mixtures—proved especially important by reducing the resonance counts owing to symmetry. Choice of substrate is always an important issue, but it proved critical in Oppolzer enolates. Various binary pairs often provided well-resolved views of some but not all structural forms. The large number of enolates examined (Chart 2) does not reflect an unchecked urge to characterize every imaginable enolate but rather a struggle to solve some difficult problems. The data collectively lead to a self-consistent structural model assembled from a large number of combinations of substrates and solvents. As an aside, tetramer ensembles in toluene require aging at 0 °C to equilibrate the aggregates.8,25 We suspect the potential consequences of slow aggregate aging are underappreciated by practitioners using lithium enolates.8a,d,e

Chart 2.

Substrates and enolates.

Density functional theory (DFT) computations supported experimentally elusive details.26,27,28 In what may seem intellectually backward to some, three crystal structures support the spectroscopic and computational conclusions.

Results

Aggregates ebb and flow with choice of solvent that included toluene, THF, HMPA, and combinations of the three. A standard protocol involves titrating enolate solutions in one solvent with variable concentrations of another, monitoring the appearance and disappearance of aggregates. The Oppolzer enolates were examined using 1H, 6Li, 13C, 15N, 19F, and 31P NMR spectroscopies; 6Li, 13C, and 19F were the most informative. 15N NMR spectroscopy using an 15N-labeled substrate lacked adequate resolution within the all-important ensembles. 31P NMR spectroscopy provided a few insights into lithium-HMPA contacts but generally was disappointing when compared with the successes enjoyed by Reich and coworkers at low temperatures inaccessible to us.15b The majority of spectra are archived in the supporting information and not mentioned herein.

There are four recurring structural types—monomers, symmetric dimers, spirocyclic dimers, and tetramers—and different forms were best observed with different enolates and ensembles. We have attempted to minimize the discomfort of the reader by using data emblematically to illustrate structural and stereochemical issues without attempting to adjudicate the assignments comprehensively. The presentation below is organized in an aggregate-centric format to illustrate key issues and strategies, beginning with monomers. An overview of the results presented using a more solvent-centric narrative is found in the Discussion.

Monomers.

The absence of detectable heteroaggregation by 1H, 6Li, 13C, and 19F NMR spectroscopies in binary mixtures of enolates is the primary evidence of a monomer. Figure 1 shows select 19F NMR spectra of representative aryl acetamide-derived enolates, a subset of Oppolzer enolates that are most prone to form monomers.29 Possible structural variations of the monomers include 12–15. The exo and endo designations refer to chelation by the sulfonyl oxygens on the exo and endo norbornyl faces, respectively. Endo and exo coordination were never observed concurrently, preventing us from distinguishing a high stereochemical preference for one from a rapid exchange of a mixture. DFT computations support 1–6 kcal/mol preferences for endo isomers in most aggregation states; however, there are exceptions and both are represented in crystal structures of dimers (below). Neither unchelated monomer 14 nor ion pair 15 are detected spectroscopically,30 but 15 proves mechanistically important. Assignment of the enolate geometries as Z isomers derives from putative A-strain in all carboxamide-like enolates,31 the X-ray structures discussed below, and DFT computations. NOE studies were not definitive.

Figure 1.

19F NMR spectra of 0.10 M of [6Li]8r, [6Li]8t, and a 4:6 mixture in 0.30 M HMPA in toluene at −80 °C.

HMPA-solvated enolates are central to this study because HMPA is required for successful alkylations. While the alkyl-substituted enolates show no evidence of HMPA-solvated monomers, additions of >1.5 equiv of HMPA to the aryl-substituted enolates show monomers emerging concurrently with dimers; monomers become the dominant form at >3.0 equiv of HMPA. They appear at characteristic chemical shifts as broad singlets, broad triplets, or well-resolved 1:2:1 triplets depending on the substrate and temperature.32 Figure 2 shows monomer 16 (R = m-CF3Ph) as a 1:2:1 triplet centered at −0.64 ppm (JLi-P = 3.2 Hz) flanked by two low intensity multiplets corresponding to dimers (vide infra). 31P NMR spectroscopy shows two 31P resonances (1:1) broadened by unresolved 6Li coupling, which logically correspond to the endo- and exo-disposed HMPA ligands of 16. DFT computations support 16 over the exo chelate by 4.9 kcal/mol.

Figure 2.

6Li NMR spectrum of 0.10 M [6Li]8u in 0.30 M HMPA in toluene at −100 °C showing monomer 16 (orange) along with a bridged trisolvated dimer 24 (red, vide infra).

The bis-HMPA solvation confirms the chelate remains intact rather than forming 14 or 15 based on extensive studies of HMPA-solvated lithium salts by Reich and coworkers.15b DOSY showed that monomer 16 has a lower relative molecular weight than trisolvated dimers (discussed below), confirming that the triplet stems from the relatively small monomer 16 rather than from a relatively large tetrasolvated dimer of general structure (ROLi)2(HMPA)4.

Dimers.

We are not only presented with the complexity of endo versus exo chelation but also by what we colloquially refer to as symmetric dimers (17 and 18) and spirocyclic dimers (19 and 20). A crystal structure of enolate 8c reveals dimer 22 (Figure 3), which corresponds to homochiral dimer 17 (R = ethyl) showing coordination to the endo sulfonyl oxygen with one HMPA on each lithium syn to each other. A 7:3 scalemic mixture of aryl-substituted enolate 8t (Figure 4) affords dimer 23, which corresponds to heterochiral dimer 21 (R = p-fluorophenyl) showing chelation by the exo sulfonyl oxygen with one THF on each lithium anti to each other.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of bis-HMPA solvated enolate 8c corresponding to homochiral dimer 22 showing double endo chelation with one HMPA on each lithium syn to each other.

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structure of bis-THF solvated enolate 8t corresponding to heterochiral dimer 23 (Ar = p-fluorophenyl) showing double exo chelation with one THF on each lithium anti to each other.

Symmetric dimers such as 17 or 18 have magnetically equivalent subunits and would display a single 6Li resonance. The spirocyclic dimers 19 and 20 display two well-resolved 6Li nuclei while displaying magnetically equivalent subunits. Select spectra of enolates 8b and 8g (Figure 5) and the affiliated Job plot (Figure 6) confirm the dimer assignment. An alternative view using scalemic mixtures of 8t affording magnetically identical A2 and B2 homodimers provides the Job plot in Figure 7.6 The non-statistical preference for heterodimerization in Figure 7—the two curves should meet at 0.50 relative intensity and XS = 0.50 in a statistical sample—is supported by DFT suggesting a 2.2 kcal/mol preference.

Figure 5.

6Li NMR spectra of 0.10 M mixtures of [6Li]8b (A, blue) and [6Li]8g (B, red) in neat THF at −80 °C. One new resonance appears for the mixed aggregate (A1B1, orange).

Figure 6.

Job plot showing relative integrations of homodimers of [6Li]8b (A2, blue) and [6Li]8g (B2, red) and the heterodimer (A1B1, orange) plotted against the measured mole fraction24 of [6Li]8b (XA) for 0.10 M mixtures of lithium enolates [6Li]8b and [6Li]8g in neat THF at −80 °C monitored by 6Li NMR spectroscopy (Figure 5). The curves result from a parametric fit to a dimer model.

Figure 7.

Job plot showing relative integrations the two magnetically equivalent homochiral homodimers of [6Li]8t (R2/S2, red), and the heterochiral mixed dimer (R1S1, orange) plotted against the measured mole fraction24 of [6Li](S)8t (XS) for scalemic 0.10 M mixtures of [6Li]8t in 10 M THF/toluene at −80 °C monitored by 19F NMR spectroscopy. The curves result from a parametric fit to a dimer model.

Conjugation-stabilized aryl acetamide-derived enolates in toluene afford homoaggregated spirocyclic dimers (19 or 20) manifesting magnetically equivalent enolate subunits and two inequivalent lithium nuclei to the exclusion of higher aggregates. Although the 6Li resonances within dimer ensembles were poorly resolved, 19F NMR spectroscopy (Figure 8) provided the resolution for a clean dimer-based Job plot (Supporting Information).33

Figure 8.

19F NMR spectra of mixtures of [6Li]8s (A2, blue) and [6Li]8t (B2, red) in toluene at −80 °C. Two new resonances appear for the mixed aggregate (A1B1, orange).

Incremental additions of HMPA to enolates in THF or toluene showed a recurring theme in which a single 6Li resonance of variable intensity corresponding to monomer 16 (monomer type 12) as discussed above was flanked by two equal-intensity 6Li resonances. Resolution of the 6Li-31P couplings was substrate-dependent; enolate 8o provided a particularly clear view (Figure 9). The two doublet-of-doublets (JLi-P = 3.2 and 1.1 Hz) first noted in Figure 2 correspond to a bridged dimer with a partial structure 24. Monomer 16 is favored at elevated HMPA concentrations and low enolate concentrations, consistent with higher per-lithium solvation and lower aggregation than 24. The small coupling in 24 is characteristic of bridged (μ2) HMPA ligands.15b

Figure 9.

6Li NMR spectrum of 0.10 M [6Li]8o in 0.30 M HMPA in toluene at −100 °C showing bridged trisolvated dimer 24 (red) and monomer 16 (orange).

The partial structure 24 with requisite proximal (synfacial) HMPA ligands is consistent with the HMPA ligands in the crystallographically characterized disolvated dimer (Figure 3). Moreover, two doublet-of-doublets (1:1) suggest an asymmetry that would arise from magnetically inequivalent subunits. This lack of symmetry seems to demand either a single endo-exo pairing such as 25 or 26 or a 1:1 mixture of two symmetric dimers out of four possible isomers, 27–30. The invariant 1:1 proportions of the two double-of-doublets in numerous examples seems too coincidental, prompting us to lean firmly toward 25 or 26. Computations of the six isomers showed 25 to be strongly preferred relative to 30 while stable minima with intact core structures could not be located for dimers 26–29.

Tetramers.

Tetramers of general structure 31 with D2d-symmetric cores manifesting a single 6Li resonance and magnetically equivalent subunits had been observed for lithiated Evans enolates (5).8d Tetramers with S4-symmetric cores (32) manifesting two 6Li resonances (1:1) and two magnetically inequivalent subunits were observed for chiral amino alkoxides.34,35 Both forms are well represented crystallographically for tetrameric chelated lithium salts. Alkyl-substituted Oppolzer enolates (8a–n) in toluene uniformly display the spectral properties anticipated for 32. Computations using propionate enolate 8b reveal an 11 kcal/mol preference for 32 over 31.

Confirming the tetramer assignment by MCV was particularly challenging because of isomerism within the 3:1, 2:2, and 1:3 heteroaggregates (Chart 3). A complete ensemble of S4-type tetramers in the limit consists of 10 discrete isomers manifesting 32 magnetically distinct subunits. Although relief from steric congestion might drive stereocontrol and preclude some isomers, success was not guaranteed. In previous examples we could monitor aggregate proportions at elevated temperatures wherein each stoichiometry in the An–Bn ensemble appears as a single 6Li resonance owing to intraaggregate 6Li-6Li exchange.5,34 Unfortunately, Oppolzer enolates in toluene decompose above 0 °C, temperatures well below those needed to observe intraaggregate coalescence.

Chart 3.

Ensemble of homo- and heteroaggregated tetramers and affiliated resonance counts.

The most tractable result emerged from mixtures of 8f and 8l, affording 18 identifiable 6Li resonances total. Monitoring the intensities against mole fraction (Figure 10), paying particular attention to mass action effects to discern the different stoichiometries, afforded tentative assignments to the various aggregate stoichiometries and the Job plot in Figure 11. While this confirms high (tetramer-like) aggregation behavior, the reliance on precise attributions seems fanciful. Fortunately, a much better solution arose.

Figure 10.

Select 6Li NMR spectra of mixtures of [6Li]8l (A4) and [6Li]8f (B4) in toluene at −80 °C. The sealed NMR tubes were aged at 0 °C for 10 min. The total molar ratio (8l:8f) of the two enolates is superimposed to the left of each spectrum. Several new overlapping resonances appear for the mixed aggregates (A3B1, A2B2, A1B3) consistent with a tetramer model.

Figure 11.

Job plot showing relative 6Li integrations (Figure 10) of the two homoaggregates of [6Li]8l (A4, blue) and [6Li]8f (B4, red), 3:1 mixed tetramers A3B1 (violet), 2:2 mixed tetramer A2B2 (orange), and 1:3 mixed tetramer A1B3 (green) against the measured24 mole fraction of [6Li]8l (XA) for 0.10 M mixtures of lithium enolates [6Li]8l and [6Li]8f in neat toluene at −80 °C. The curves result from a parametric fit to a tetramer model.

Binary mixtures of two enantiomers reduce the number of possible structures (Chart 4) and the number of resonances owing to enantiomeric R4/S4, R3S1/R1S3, and R2S2 aggregate pairs and generally higher symmetries within several heterotetramers. The theoretical upper limit drops to 6 discrete aggregates displaying 12 6Li resonances. We suspected that stereocontrolled aggregation might further reduce the number of resonances. In the optimistic event of total stereocontrol producing a single stereoisomeric heteroaggregate for each stoichiometry, the theoretical aggregate count drops to three and the resonance count to seven.

Chart 4.

Ensemble of homo- and heteroaggregated tetramers from scalemic mixtures and affiliated resonance counts.

We got lucky. Three enantiomeric pairings each afforded the optimal stereocontrol manifesting only seven resonances, affording successful MCV analyses; scalemic mixtures of the isopropyl substituted enolate 8f gave the most visually pleasing spectra (Figure 12) and Job plot (Figure 13). The 2:2 stoichiometry, for example, displays a single resonance out of a possible four. We are fully confident in the tetramer assignment and find the stereochemical complexity of aggregation quite satisfying (in retrospect).

Figure 12.

6Li NMR spectra of mixtures of the two antipodes of [6Li]8f in toluene at −80 °C and aged at 0 °C for 10 min.25 The intended (not measured) molar ratio (S:R)24 of the two enolates is to the left of each spectrum. Five new resonances appear for the mixed aggregates (R3S1, R2S2, R1S3) consistent with a tetramer model.

Figure 13.

Job plot showing relative integrations plotted against measured24 mole fraction of the S antipode (XS) in 0.20 M scalemic mixtures of lithium enolate [6Li]8f in neat toluene at −80 °C monitored by 6Li NMR spectroscopy (Figure 12). The curves showing mirror image homotetramers (R4/S4, red), mirror image 3:1 heterotetramers (R1S3/R3S1, blue), and a single 2:2 heterotetramer (R2S2, orange) result from a parametric fit to a tetramer model.

We examined the heterochiral ensemble using DFT. The 3:1 and 2:2 mixed tetramers showed 6.0 and 4.0 kcal/mol preferences, respectively, for single isomers. An observed small non-statistical preference for forming the 3:1 and 2:2 heterotetramers observable in Figure 13—the blue and orange curves should contact at XS = 0.5—are overestimated computationally (2.0 and 1.7 kcal/mol, respectively.)

Influence of Excess LDA.

A standard protocol of probing for lithium enolate-LDA mixed aggregates by using excess [6Li,15N]LDA revealed dianion crudely depicted as 33 instead (eq 3).36 Three distinct 6Li resonances (2:1:1) showed no 6Li-15N coupling. A crystal structure showed a complex aggregate comprised of four subunits of dianion 33 with a symmetry consistent with the 6Li spectral data (Figure 14). There are no C–Li contacts. The structure of the dianion is of limited pedagogical value except to reveal the origins of byproducts reported in the synthetic organic literature discussed below.37 The Li8O12X4 core structure does not appear in the Cambridge Database.

|

(3) |

Figure 14.

Partial X-ray crystal structure of octalithiated tetramer with D2 symmetry consisting of four units of dianion 33 (left) and partial structure (right). Six coordinated THF molecules have been omitted for clarity.

Kinetics of alkylation.38

The mechanism of alkylation was studied using enolate 8o and allyl bromide (eq 4). The enolate generated in situ using recrystallized LDA39 exists as bis-HMPA-solvated monomer 16 (R = Ph) over all concentrations of HMPA (0.075 – 0.90 M), THF (0.50 – 11.0 M), and allyl bromide (≤0.825 M).40 Alkylation rates were monitored by in situ IR spectroscopy41 following the loss of enolate 8o (1616 cm−1) and formation of product 34 (1704 cm−1). Figure 15 illustrates an emblematic decay. Alkylations under more synthetically relevant conditions (0.10 M enolate and 3.0 equiv of allyl bromide) displayed no unusual curvatures that would be emblematic of intervening consequential autocatalysis or auto-inhibition.38d

|

(4) |

Figure 15.

Alkylation of 8o (0.025 M; 1616 cm−1) with 0.275 M allyl bromide in 9.00 M THF/toluene at −78 °C to form 34 (1704 cm–1). The red curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to eq 5, such that n = 1.01 ± 0.02, kobsd = 0.0064 ± 0.0005, and [substrate]0 = 0.0261 ± 0.0002.

With enolate as the limiting reagent and boxed in by technical limitations owing to substrate solubitilities, we turned to the non-linear variant of the van’t Hoff differential method (eq 5)42 to determine the enolate order, n, by best-fit. The curve in Figure 15 stems from such a fit. Although orders determined by this method routinely afford considerable variation from run to run, replication solves that problem. An enolate order of 1.2 ± 0.2 was obtained from the 132 independent decays used to obtain values for kobsd. The first order in excess allyl bromide was confirmed by a two-point control experiment showing a direct relationship of kobsd to concentration.

| (5) |

A plot of kobsd against [HMPA] concentration reveals a second-order dependence (Figure 16) implicates an intermediate ion pair or free ion with a +Li(HMPA)4 counterion commonly observed spectroscopically.15b The first-order rather than half-order enolate dependence implicates ion pair 35 with correlated ions rather than fully formed free ions, which would manifest a half-order dependence.43

Figure 16.

Plot of kobsd against [HMPA] for the alkylation of enolate 8o (0.025 M) with 0.275 M allyl bromide in 9.0 M THF/toluene at −78 °C. The asterisk (*) to the far left is outside pseudo-first-order conditions and was not included in the fit. The blue curve depicts an error-weighted least-squares fit to f(x) = axb such that a = 0.062 ± 0.001, b = 2.2 ± 0.1.

A plot of kobsd against THF concentration revealed a second-order THF dependence (Figure 17, blue curve). Superficially, this implicates a +Li(HMPA)4(THF)2 cation. However, using toluene as the cosolvent proved to be a fateful choice. Suspecting from previous studies that secondary-shell (medium) effects could be intervening we carried out a standard control experiment in which 2,5-Me2THF was used as a sterically encumbered (non-coordinating) cosolvent with a dielectric constant nearly equal to that of THF.44 The resulting zeroth-order THF dependence is shown in Figure 17 (red curve). Thus, the second-order THF dependence is entirely attributable to sterically insensitive medium effects, which seemed extraordinary based on numerous previous studies (most but not all) revealing trivial cosolvent dependencies. Having observed strange effects of toluene on several occasions,45 we monitored the initial rate against toluene concentration using cyclopentane as cosolvent at fixed HMPA and THF concentrations and obtained an inverse-first-order dependence (Figure 18). These sterically insensitive (secondary-shell) effects are considered further in the discussion.

Figure 17.

Plot of kobsd against THF concentration for alkylation of 0.025 M 8o with allyl bromide (0.275 M) in 0.275 M free HMPA concentration46 at −78 °C in toluene (●) or 2,5-Me2THF (◆) co-solvent. The asterisk (*) to the far left is not under pseudo-first-order conditions and was not included in the fit. The blue curve depicts an error-weighted least-squares fit to the function f(x) = y0 + axb such that y 0 = 1.0 × 10−4 ± 0.1 × 10−4, a = 2.5 × 10−5 ± 0.4 × 10−5, b = 2.1 ± 0.1. The red curve depicts an error-weighted least-squares fit to the function f(x) = y0 + ax such that y0 = 4.9 × 10−3 ± 0.2 × 10−3, a = 1.1 × 10−5 ± 2.9 × 10−5.

Figure 18.

Plot of rate constants determined from initial rate measurements against toluene concentration for the alkylation of 0.025 M 8o at −78 °C with 0.275 M allyl bromide in 0.275 M free HMPA in 2.0 M THF using cyclopentane cosolvent. The curve depicts an error-weighted least-squares fit to the function f(x) = y0 + axb such that y0 = −1.4 × 10−6 ± 0.3 × 10−6, a = 5.1 × 10−5 ± 0.3 × 10−5, b = −1.1 ± 0.2.

Discussion

We have described one of those investigations that might have given us pause had we anticipated the challenges. The structural studies provided inordinate complexity while the rate studies offered unexpected results. We begin by summarizing the structural studies described above and archived in Supporting Information by taking a solvent-centric look at aggregation, underscoring the general trends.

Solvent- and substituent-dependent aggregation.

Scheme 1 depicts the structural changes of Oppolzer enolates as a function of solvent, taking liberties to make the story tractable. The loops represent the sultam chelates while the sticks and spheres reflect different faces with implicitly different steric demands. The loose term “solvent power” connotes the progression through a combination of increasing solvent donicity47 (Lewis basicity) and increasing donor solvent concentration, which tend to work in concert.

Scheme 1.

Solvent-dependent aggregates of Oppolzer enolates.

Oppolzer enolates in toluene exist as two structural types depending on the enolate substituent. The sterically unhindered alkyl-substituted enolates afford tetramers of type 32 with S4-symmetric cores analogous to lithium amino alkoxides in solution34 rather than drum-like structures with D2d-symmetric cores (31) formed by Evans enolates (5, Chart 1).8d,48 This is supported by DFT computations showing an 11 kcal/mol preference isomer 32. Primary-shell solvation (ligation) by toluene is implicated only in the spirocyclic dimer structures (see below), but toluene strikingly influences reactivity (vide infra.)

Ironically, our first efforts to explore tetramers computationally using phenylacetate-derived enolate 8o as a model completely failed to afford stable minima with the cubic core intact. We subsequently discovered that the relatively large phenyl groups49 preclude the formation of tetramers, affording the spirocyclic dimers (36) instead. Enolates 8f and 8g bearing large alkyl substituents form tetramer 32 along with low levels of spirocycle 36. DFT suggests a 2.0 kcal/mol exothermic solvation of the terminal lithium of 36 by toluene (Figure 19). The partial structure in Figure 19 shows an interesting gearing of the three phenyl moieties. Although this should render the two subunits magnetically inequivalent, high flux-ionality would be expected to negate the broken symmetry.

Figure 19.

DFT-computed structure of phenyl-substituted enolate 8o displaying a type-36 core structure. The partial structure illustrates the disposition of the ligated toluene measurably out of the Li2O2 plane.

We routinely study solvation by titrating hydrocarbon solutions of organolithiums with donor solvent to observe structural changes during the transition from the large aggregates to more highly solvated lower aggregates.7 This strategy provided complex and largely useless spectra at low THF concentrations en route to the tractable dimers emerging at elevated (typically >3.0 M) THF concentrations. Both alkyl- and aryl-substituted enolates afford symmetric solvated dimers 37 or 38. THF solvates with anti-oriented THF ligands (37) are assigned based on DFT computations and analogy to a crystal structure in Figure 4. These THF-solvated dimers proved well-suited for MCV-based characterizations and would have been excellent candidates for mechanistic studies if not for their failure to alkylate below the temperatures of enolate decomposition.

Incrementally adding HMPA to toluene and various THF-toluene mixtures revealed several resonances that were candidates for the bis-HMPA-solvated dimers (see 37 or 38), but their concentrations remained low, and definitive assignments were elusive. The dominant HMPA-solvate is akin to type-38 dimer observed crystallographically (Figure 3) but with an additional bridging (μ2) HMPA. This trisolvated dimer with a core structure illustrated by 24 invariably coexists with disolvated monomer of type 39. Of 6 possible isomeric trisolvates (25–30), broken symmetry observed spectroscopically in conjunction with DFT computations pointed to a single isomer 25 with a mix of endo and exo chelation (Figure 20). Of the five other isomers, only 30 afforded stable minima with intact core structure, and it is considerably higher energy.

Figure 20.

DFT-computed structure of tris-HMPA-solvated dimer 25 (R = Ph).

Monomer of type 39 (drawn in more detail as 16 in eq 4) containing two magnetically inequivalent HMPA ligands forms to the exclusion of 40 that would be at least trisolvated according to Reich’s extensive studies of HMPA solvation.15b Most importantly, type-39 monomers form over a wide range of conditions for aryl-substituted enolates, establishing structural foundations for rate studies. Before addressing the alkylation mechanism and its role in dictating stereoselective alkylation, however, there are a few structural details to consider.

Stereochemistry of aggregation.

Something so simple as whether the sultam chelate exploits the exo or endo sulfonyl oxygen remains unresolved spectroscopically; the endo form is preferred computationally in most environments, while both are represented crystallographically. Stereochemical issues that emerged when using MCV to determine aggregation state are primarily academic but are interesting nonetheless. One can argue that understanding stereocontrolled aggregation may reveal how to exploit homo- and heteroaggregate structures to impose stereocontrol on tetramer-based transformations.14,50 Probably the most spectacular example of this was achieved by Merck Process in their Efavirenz synthesis.51

Characterizing S4-type tetramers using MCV relies on generating ensembles of two structurally distinct enolates with up to 32 magnetically inequivalent subunits (Chart 3). By contrast, pairing enantiomers—generating analogous RmSn ensembles from scalemic mixtures—reduces the number of possible magnetically equivalent subunits to 12 (Chart 4). In the limit that steric biases impart total dia-stereoselectivity, the resulting heterochiral ensembles could reduce to as few as 3 distinct tetramers manifesting only 7 magnetically distinct subunits. That is precisely what happened as illustrated by the clean ensembles and convincing Job plots (Figures 12 and 13).

Dianion.

Synthetic chemists have reported byproducts of type 41 in which LDA appeared to metalate proximate to the sulfonyl group.37 Our quest for evidence of LDA-enolate mixed aggregates instead afforded 33 as a spectroscopically and crystallographically characterized octalithiated tetramer (Figure 14). The dianion did not form mixed aggregates with LDA, which contrasts with dianion 6 corresponding to Myers enolates (Chart 1).8e

Despite square planar lithiums and no C–Li contacts, there is nothing particularly notable about the structure. It does, however, prompt a few comments and some ideas worth exploring. Decades ago we rediscovered52 the high tendency of sulfones to stabilize dianions of general structure ArSO2CM2R (M = Li, Na, or K)53,54 and even ArSO2CLi3.55 In short, sulfones are remarkably effective at stabilizing anions. Synthetic organic and inorganic chemists have largely overlooked these potentially interesting synthons. We also suspect there is a general and notion within the community that dianions are destabilized by charge repulsion. To understand the flaw in this logic, compare an aggregated alkoxide to a dilithiated dial-koxide (42 and 43): it is altogether unclear why simply adding the bridge would be destabilizing. Moreover, given that highly reactive organolithiums routinely aggregate; invoking charge repulsion is linguistically and thermochemically suspect.

Mechanism of alkylation and odd solvent effects.

Aryl-substituted enolates forming bis-HMPA-solvated monomers of type 16 (39 in Scheme 1) persist over a wide range of conditions rendering them well-suited for rate studies. A second-order HMPA dependence and first-order enolate dependence are fully consistent with a mechanism proceeding through a transition structure based on solvent-separated ion-pair 35. The obvious loss of the chelate stands out, but before discussing the origins of stereocontrol, we must draw attention to some unusual solvent effects.

A second-order THF dependence initially suggested a hexasolvated mixed cation, +Li(HMPA)4(THF)2, but was traced to exclusively secondary-shell (medium) effects. A superposition of an inverse-first-order toluene dependence and a first-order THF dependence were acting antagonistically: toluene stabilizes the reactant and THF stabilizes the transition structure (Figure 21). Using 2,5-Me2THF instead of toluene as cosolvent eliminates both effects, causing the apparent second-order THF dependence to disappear altogether.

Figure 21.

Medium effects on the ground and transition states.

We begin with the seemingly straightforward stabilization of the transition state by THF. Having ascertained a vast number of rate laws we have found that medium effects in THF/hexane mixtures range from small to undetectable in most instances.38c In short, to the extent there are medium effects in the ground state and transition state they cancel. The +Li(HMPA)4 gegenion, however, would logically be stabilized by secondary shell (possibly ordered) dipoles.15b,55 In analogy to the Oppolzer enolate alkylations, an ionization-based alkylation of Ph2NLi in THF56 revealed exceedingly high THF orders that were traced to the superposition of primary and secondary shell influences.

Stabilization of the reactants by toluene is more nuanced but also supported by other studies. Evidence of primary shell lithium ion coordination by aromatic hydrocarbons is well documented.7 While it is difficult to imagine a consequential stabilization of monomer 16, we have observed strange effects of aromatic hydrocarbons on both observable organolithium equilibria as well as on reaction rates even in the presence of far superior donor solvents.38d The closest analogy to the Oppolzer enolates is found in LDA-mediated enolization of esters in THF-HMPA, also displaying a second-order HMPA dependence owing to an ion-paired intermediate.45d Changing the ‘inert’ cosolvent from pentane to cyclopentane to help solubilize the HMPA reduced the observed rates without reducing the HMPA reaction order. We surmised that the cyclopentane-based stabilization of HMPA imparting higher solubility was the same stabilization retarding the reaction. Thus, the enolization of esters and the alkylation of Oppolzer enolates are retarded by solvent-solvent interactions. The notion that dissolving reactants necessarily has a retarding influence on reactivity is self-evident in retrospect but easily overlooked. That such rate effects are observed in the presence of notoriously more polar solvents and are attributable to solvent-solvent rather than solvent-lithium interactions is sobering. Thus, it is precarious to consider toluene an “inert” cosolvent. It is to be respected and, if necessary, avoided in detailed rate studies. We have fallen into this trap several times.45,57,58

Origins of the stereoselectivity.

We now must unbury the lede and ponder the origins of the highly stereocontrolled alkylations. The ion pair-based alkylation ensures there is no role of the chelate despite its central importance to every mechanistic model reported to date with one exception.59 The solvent-separated ion pair even renders the lithium cation largely irrelevant.

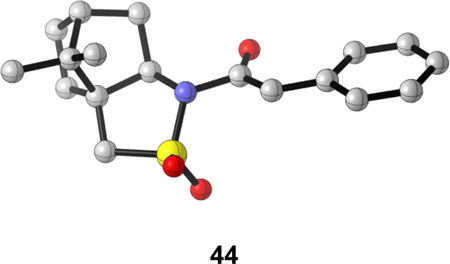

This is where the story gets interesting. The computed structure of the cation-free enolate, 44, shows a 131° S-N-C-O dihedral angle, which operationally reverses the faces of the enolate exposed to the steric influence of the gem-dimethyl groups when compared with chelated forms. DFT computations show a 3.9 kcal/mol preference for 44 over the rotamer with the enolate oxygen syn to sulfone. The preferred alkylation of 44 requires approach of the electrophile syn to the protruding camphor methyl group. Indeed, DFT computations show a 2.6 kcal/mol preference for syn (exo) approach via transition structure 45 relative to anti (endo) approach via 46. There are minor differences in the S-N-C-O dihedral angles (145° versus 164°) but overlaying the two transition structures shows a high skeletal superposition.

We consider five possible stereochemical determinants emanating from potentially key van der Waals interactions and several critical dihedral angles and distortions within the substrate.

On inspection of 45 and 46 one is struck by the absence of significant alkyl halide-methyl interactions that are central to all qualitative stereochemical models. The most consequential is a 1.9 Å H–H interaction on preferred transition structure 45. A 2.4 Å H–O contact with the endo sulfonyl oxygen in 46 compared to a 3.3 Å H–O contact the exo sulfonyl oxygen in 45 could, in principle, be important, although even 2.4 Å seems distant. We return to this after exploring other contributions.

-

The alignment of the allyl moieties over the enolate and aromatic ring in 45 and 46 (p-stacking)60 was found to be stabilizing by approx. 2.0 kcal/mol by comparing isomeric transition structures in which the allyl group is rotated away. Nonetheless, the stereochemical preference is largely retained (2.2 kcal/mol) in the non-p-stacked analogs. Eliminating the p-stacking altogether by replacing the phenyl moiety with a methyl group retains a 2.8 kcal/mol stereochemical preference. Similarly, using methyl bromide instead of allyl bromide shows disparate H–O contacts (3.3 and 2.1 Å) and retains a 2.0 kcal/mol preference for 47 relative to 48. We switched focus to methylation to simplify subsequent calculations.

-

The role of the camphor methyl group in conventional stereochemical models is to block the exo face. Removal of the two camphor methyls (see 49 and 50) shows only a slightly lower (1.4 kcal/mol) facial preference. The desmethyl transition structures 49 and 50, however, show distortion of the camphor portion accompanied by little change of the S–N–C–O and C–C–C–N dihedral angles.

-

Given the potentially (but weakly) destabilizing 2.4 Å O–H interaction in 46 and the inconsequential 3.3 Å O–H interaction in 45, we wondered if the role of the bicyclo[2.2.1] portion of camphor was to influence the sultam conformation. Transition structures 51 and 52 containing only the core sultam ring showed a markedly reduced stereoselectivity (0.4 kcal/mol) accompanied by near parity (2.5 Å and 2.4 Å, respectively) of the H–O interactions. What was also noticeable, however, is that the C–C–C–N dihedral angles of −41° and −38°, respectively, were reduced when compared to 47 and 48 (–34° and −32°, respectively), causing the sultam to be less puckered. Anchoring the dihedral angles of 51 and 52 to the values observed in 47 and 48 restored the stereochemical preference (1.4 kcal/mol).

-

The emerging model based on an H–O interaction between the alkyl bromide and sulfonyl moiety is appealing, but so was the model based on chelates. It seemed possible that a stereoelectronic effect was at play in which the electrophile preferentially approaches anti to the endo sulfonyl oxygen as illustrated in 51. To address this, we removed any possibility of an H–O interaction and dramatically reduced all steric effects by examining proton transfers. After probing a few electrophiles trying to minimize additional unwanted variables, we settled on the metalation of CHF3 via 53 and 54. The 1.2 kcal/mol preference for 53 suggests a dominant stereoelectronic influence.

We must confess that the camphor methyl moiety ostensibly hovering over the face of the enolate always appeared too distant to us, but the universally accepted model was compelling. It appears that the role of the camphor core is to impart chirality and conformational rigidity in the sultam but offer little in the way of direct van der Waals influence on the incoming electrophile. In short, the stereocontrol emanates from interactions of the electrophile with the sulfonyl, not the camphor core, and even this interaction appears to be stereoelectronic rather than steric.

This stereochemical model reduces Oppolzer enolates to a chiral sultams without a chelate or even a counterion. The results evoke images of alternative applications of sultam-derived enolates of general structure 55. Alas, there are many substituted sultams, but all are expensive. In this sense, Oppolzer’s auxiliary is uniquely suited for the task.

Conclusion

The work described herein began with a seemingly straightforward goal to fill in structural and mechanistic puzzle pieces in the story of stereoselective enolate alkylation. It is commonplace for the complexity and unanticipated results to exceed our expectations, but we continue to be surprised. The structural studies proved quite complex and challenging; enolates have generally proven far more difficult to study than, for example, lithium amides.

For those interested in solvation, we should underscore the value of kinetics to study primary and secondary shell solvation. The high HMPA order is not surprising: HMPA is reputed to solvate and ionize lithium salts. The medium effects in which toluene stabilizes the ground state and THF stabilizes the transition state are quite surprising. Although they may appear to be purely academic on first inspection, there are potential practical consequences. A tenfold rate inhibition by the “inert” cosolvent toluene could impose considerable cost differences as process chemists choose between heptane and toluene. To unquestioningly treat these two solvents as interchangeable in any setting would be a mistake.

It is dangerous to extrapolate or generalize the results from a single detailed mechanistic study, but there is a case for rethinking all reactions of the Oppolzer auxiliary. Given the irrelevance of the solvent-separated counterion, alkylations of the sodium enolates generated from NaHMDS/THF might also follow this same model. Oppolzer enolates with alternative counterions such as zinc, titanium, or boron could proceed by open transition structures as found in boron variants of Evans enolates with the sultam rather than the camphor methyl moiety still dictating the stereoselectivity. Could 1,4-additions and Diels-Alder cycloadditions to unsaturated Oppolzer sultams also be under the influence of stereoelectronic control by the sultam ring? The complete story makes us wonder if stereoelectronic effects of sulfonyl and other S(IV) and S(VI) moieties on stereocontrolled functionalizations might be overlooked.

The ionization-based mechanism suggests that those looking for alternatives to HMPA should be pondering lithium-ion-selective ligands. Of course, synthetic chemists turned to sodium enolates, probably paying little or no attention to the counterion’s role. We already have preliminary data showing that sodiated Oppolzer enolates are challenging to study, but that is another story altogether.

Experimental

Reagents and solvents.

LDA, [6Li]LDA, and [6Li,15N]LDA were prepared as white crystalline solids.61 Toluene, hexanes, THF, MTBE, cyclopentane, 2,5-Me2THF, and HMPA were distilled from blue or purple solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. Allyl bromide was distilled from 4Å molecular sieves. Substrates 7a–u were prepared according to slightly modified literature procedures.9

Synthesis of [15N]-camphorsulfonamide.

[15N]-Camphorsulfonyl chloride was prepared by adding thionyl chloride (SOCl2, 1.45 mL, 20.0 mmol) and 2 drops of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) to solid camphorsulfonic acid (3.1 g, 13.3 mmol) at room temperature. The slurry was stirred at 90 °C until gas generation ceased. Meanwhile, [15N]NH3 was generated from [15N]NH4Cl (>99% 15N isotopic purity, 1.3 g, 23.9 mmol) and excess solid NaOH.62 The resulting [15N]NH3 (approx. 0.6 mL) was dissolved in 1.0 mL water and added to the camphorsulfonyl chloride on ice with vigorous stirring. Note: this reaction is highly exothermic. 5.0 mL water was added to the reaction. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature over several hours and tracked by TLC (SiO2, 1:1 Hex:EtOAc). The insoluble [15N]-camphorsulfonamide (1.3 g, 42.5%) was collected by filtration, dried in vacuo, and used without further purification. [15N]-camphorsultam was prepared from [15N]-camphorsulfonamide according to literature procedures.63,64 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.34 (d, J = 78.2 Hz, 2H), 3.47 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H), 3.13 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (ddd, J = 18.8, 5.0, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 2.16 (dd, J = 8.1, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 2.11 – 2.02 (m, 2H), 1.96 (d, J = 18.7 Hz, 1H), 1.52 – 1.43 (m, 1H), 1.01 (s, 3H), 0.93 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 217.81, 59.53, 54.21, 54.19, 49.27, 43.23, 42.98, 27.21, 26.99, 20.12, 19.53. 15N NMR (61 MHz, CDCl3) δ 97.30. HRMS (DART) Calc. for C10H1815NO3S+ (M+H+): 233.09723; found: 233.09855.

NMR spectroscopic analyses.

An NMR tube fitted with a double-septum under vacuum was flame-dried on a Schlenk line and allowed to passively cool to room temperature, backfilled with argon, and placed in a dry ice/acetone cooling bath. Individual stock solutions of the N-acyl sultams and [6Li]LDA were prepared at room temperature and −78 °C, respectively. The appropriate amounts of the N-acyl sultams, [6Li]LDA, solvent, and (when applicable) co-solvent were added sequentially via gastight syringe. The tube was flame-sealed under partial vacuum while cold to minimize evaporation. The tubes were mixed on a vortex mixer and stored at −80 °C. Unless otherwise stated all tubes were sealed with a total enolate concentration of 0.10 M. Standard 1H, 19F, 6Li, 13C, 15N, and 31P direct detection spectra were recorded on a 11.8 T spectrometer at 500.1, 470.6, 73.6, 125.8, 50.7, and 202.5 MHz, respectively. 1H, 13C, 15N, and 31P resonances are referenced to their respective standards (Me4Si, NH3, and H3PO4, all at 0.0 ppm). 6Li resonances are referenced to 0.30 M [6Li]LiCl/MeOH (0.0 ppm). 19F spectra are referenced to C6H5F (−113.15 ppm). For quantitated 6Li and 19F spectra, the spin-lattice relaxation (T1) was determined by standard inversion recovery experiments on several samples. The relaxation delay (d1) was set to seven times the average relaxation lifetime. Integration of the NMR signals was determined using the line-fitting method included in MNova (Mestrelab research S.L.).

Rate Studies.

IR spectra were recorded with an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe. The spectra were acquired at a gain of 1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1. All tracked reactions were conducted under a positive flow of argon from a Schlenk line. A representative reaction was carried out as follows: The IR probe was inserted through a Teflon adapter and O-ring seal into an oven-dried, cylindrical flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar and a T-joint. The T-joint was capped with a septum for injections and an argon line. After evacuation under full vacuum, heating, and flushing with argon, the flask was charged with the THF/cosolvent mixture of choice (toluene, 2,5-Me2THF, toluene/cyclopentane) and cooled to −78 °C in a dry ice−acetone bath. A set of 256 baseline scans were collected and IR spectra were recorded every 15 seconds from 30 scans. The reaction vessel was charged to 0.025 M 7o (1704 cm−1). A 2.00 M stock solution of LDA was injected (0.030 M, 1.2 equiv) through the septum, and enolization was tracked to completion (1616 cm−1), typically ~10 min. Following full disappearance of 7o, HMPA was added to the reaction as a 4.70 M (75 v/v%) stock solution in toluene. The reaction was left to stir for another 10 min. At this point, spectral collection was halted, and an additional 256 baseline scans were collected. The spectrometer was configured to collect spectra every 5 seconds from 16 scans. 1 set of scans was collected before addition of neat allyl bromide through the septum. The reaction was tracked over 5 half-lives monitoring disappearance of the enolate (1616 cm−1) and appearance of the allyl adduct (1706 cm−1).

Single crystal X-ray diffraction.

Low-temperature X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy diffractometer coupled to a Rigaku Hypix detector with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å), from a PhotonJet micro-focus X-ray source at 100 K. The diffraction images were processed and scaled using the CrysAlisPro software.65 The structures were solved through intrinsic phasing using SHELXT66 and refined against F2 on all data by full-matrix least squares with SHELXL67 following established refinement strategies.68 All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All hydrogen atoms bound to carbon were included in the model at geometrically calculated positions and refined using a riding model. The isotropic displacement parameters of all hydrogen atoms were fixed to 1.2 times the Ueq value of the atoms they are linked to (1.5 times for methyl groups).

Structures for dimer 22 and dianion 33 were refined as inversion twins. Both structures 22 and 33 contain disordered solvent molecules of THF that were included in the unit cell but could not be satisfactorily modeled. Therefore, those solvents were treated as diffuse contributions to the overall scattering without specific atom positions using the solvent mask routine in Olex2.69 Details of the crystal growth conditions, data quality, and a summary of the residual values of the refinements are available in the supporting information.

Density functional theory (DFT) computations.

All DFT calculations were carried out using Gaussian 16.26 Prompted by a recent benchmarking of modern density functionals, all calculations were conducted at the M06–2X level of theory using Grimme’s zero-dampened DFT-D3 dispersion corrections.27a–d A pruned (99, 590) integration grid (equivalent to Gaussian’s “UltraFine” option) was used for all calculations. Where appropriate solvation effects were accounted for by the Self Consistent Reaction Field method using the SMD model of Truhlar and coworkers.27e Jensen’s polarization-consistent segment-contracted basis set, pcseg-1, was used for geometry optimizations and the expanded pcseg-2 basis set for single-point energy calculations.27f Basis set files were obtained from the Basis Set Exchange.27g Ball-and-stick models were rendered using CYLview 1.0b.27h A large number of DFT-computed energies are archived in the Supporting Information.28

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM131713) for support. This work made use of the Cornell University NMR Facility, which is supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation through MRI award CHE-1531632. NML thanks the Cornell glass shop.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: The Supporting Information is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org. Synthetic and experimental procedures, spectroscopic, rate, diffraction, and computational data.

Accession Codes: CCDC 2202043, 2202044, 2202045, 2202046 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References and Footnotes

- 1.Dugger RW; Ragan JA; Ripin DHB Survey of GMP Bulk Reactions Run in a Research Facility Between 1985 and 2002. Org. Process Res. Dev 2005, 9, 253. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For applications of lithium enolates in pharmaceutical chemistry, see; (a) Farina V; Reeves JT; Senanayake CH; Song JJ Asymmetric Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu G; Huang M Organolithium Reagents in Pharmaceutical Asymmetric Processes. Chem. Rev 2006, 106, 2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rathman TL; Bailey WF Optimization of Organolithium Reactions. Org. Process Res. Dev 2009, 13, 144. [Google Scholar]

- 3.A survey of approximately 700 total syntheses compiled by H. J. Reich and coworkers revealed LDA to be the most commonly used reagent. The database currently resides in the Hans Reich’s Collection. Total Syntheses. https://organicchemistrydata.org/hansreich/resources/syntheses/?index=groupby%2Finformation&page=acknowledgment%2F (accessed 2021-10-23).

- 4.For reviews of enolates in synthesis, see; (a) Green JR In Science of Synthesis; Georg Thieme Verlag: New York, 2005; Vol. 8a, pp 427–486. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schetter B; Mahrwald R Modern Aldol Methods for the Total Synthesis of Polyketides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Braun M Lithium Enolates: ‘Capricious’ Structures - Reliable Reagents for Synthesis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2015, 98, 1. [Google Scholar]; Also, see refs. 2a and 2b.

- 5.(a) McNeil AJ; Toombes GES; Chandramouli SV; Vanasse BJ; Ayers TA; O’Brien MK; Lobkovsky E; Gruner SM; Marohn JA; Collum DB Characterization of b-Amino Ester Enolates as Hexamers via 6Li NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liou LR; McNeil AJ; Toombes GES; Collum DB Structures of b-Amino Ester Enolates: New Strategies Using the Method of Continuous Variation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 17334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liou LR; McNeil AJ; Ramírez A; Toombes GES; Gruver JM; Collum DB Lithium Enolates of Simple Ketones: Structure Determination Using the Method of Continuous Variation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renny JS; Tomasevich LL; Tallmadge EH; Collum DB Method of Continuous Variations: Applications of Job Plots to the Study of Molecular Associations in Organometallic Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.By compound number:; (a) 2: Jin KJ; Collum DB Solid-State and Solution Structures of Glycinimine-Derived Lithium Enolates J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) 3: Houghton MJ; Collum DB Lithium Enolates Derived from Weinreb Amides: Insights into Five-Membered Chelate Rings. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 11057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) 4: Houghton MJ; Biok NA; Huck CJ; Algera RF; Keresztes I; Wright SW; Collum DB Lithium Enolates Derived from Pyroglutaminol: Aggregation, Solvation, and Atropisomerism. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) 5: Tallmadge EH; Collum DB Evans Enolates: Solution Structures of Lithiated Oxazolidinone-Derived Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) 6 (M = Li): Zhou Y; Jermaks J; Keresztes I; MacMillan SN; Collum DB Pseudoephedrine-Derived Myers Enolates: Structures and Influence of Lithium Chloride on Reactivity and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) 6 (M = Na): Zhou Y; Keresztes I; MacMillan SN; Collum DB Disodium Salts of Pseudoephedrine-Derived Myers Enolates: Stereoselectivity and Mechanism of Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 16865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Oppolzer W Camphor Derivatives as Chiral Auxiliaries in Asymmetric Synthesis. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1969. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heravi MM; Zadsirjan V Recent Advances in the Application of the Oppolzer Camphorsultam as a Chiral Auxiliary. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 1061. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C; Sheng X; Zhang L; Yu J; Huang H Arylacetic Acids in Organic Synthesis. Asian J. Org. Chem 2020, 9, 23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouda AM; Beshr EA; Almalki FA; Halawah HH; Taj BF; Alnafaei AF; Alharazi RS; Kazi WM; AlMatrafi MM Arylpropionic Acid-Derived NSAIDs: New Insights on Derivatization, Anticancer Activity and Potential Mechanism of Action. Bioorg. Chem 2019, 92, 103224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Oppolzer W; Tamura O Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acids and α-N-Hydroxyamino Acids via Electrophilic Amination of Bornanesultam-Derived Enolates with 1-Chloro-1-Nitrosocyclohexane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 991. [Google Scholar]; (b) Oppolzer W; Tamura O; Deerberg J Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Amino Acid and α-N-Hydroxyamino Acids from N-Acylbornane-10,2-Sultams: 1-Chloro-1-Nitrosocyclohexane as a Practical [NH] Equivalent. Helv. Chim. Acta 1992, 75, 1965. [Google Scholar]; (c) Oppolzer W; Darcel C; Rochet P; Rosset S; De Brabander J Non-Destructive Removal of the Bornanesultam Auxiliary in α-Substituted N-Acylbornane-10,2-Sultams under Mild Conditions: An Efficient Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure Ketones and Aldehydes. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 1319. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lu WC; Cao XF; Hu M; Li F; Yu GA; Liu SH A Highly Enantioselective Access to Chiral 1-(β-Arylalkyl)-1H-1,2,4- Triazole Derivatives as Potential Agricultural Bactericides. Chem. Biodivers 2011, 8, 1497. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards JO; Greene EF; Ross J From Stoichiometry and Rate Law to Mechanism. J. Chem. Educ 1968, 45, 381. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Seebach D Structure and Reactivity of Lithium Enolates. From Pinacolone to Selective C-Alkylations of Peptides. Difficulties and Opportunities Afforded by Complex Structures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1988, 27, 1624. [Google Scholar]; (b) Structural studies of enolates: Williard PG In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis; Pergamon: New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]; Also, see ref 4e.

- 15.(a) Günther H Selected Topics from Recent NMR Studies of Organolithium Compounds. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 1999, 10, 241. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reich HJ Role of Organolithium Aggregates and Mixed Aggregates in Organolithium Mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 7130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucht BL; Collum DB Lithium Hexamethyldisilazide: A View of Lithium Ion Solvation Through a Glass-Bottom Boat. Acc. Chem. Res 1999, 32, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Extensive leading references to structural studies of lithium enolates are provided in ref 6.

- 18.For examples of colligative measurements on lithium enolates, see; (a) Bauer W; Seebach D Degree of Aggregation of Organolithium Compounds by Means of Cryoscopy in Tetrahydrofuran Helv. Chim. Acta 1984, 67, 1972. [Google Scholar]; (b) Arnett EM; Moe KD Proton Affinities and Aggregation States of Lithium Alkoxides, Phenolates, Enolates, β-Dicarbonyl Enolates, Carboxylates, and Amidates in Tetrahydrofuran. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 7288. [Google Scholar]; (c) Arnett EM; Fisher FJ; Nichols MA; Ribeiro AA Structure-Energy Relations for the Aldol Reaction in Nonpolar Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112, 801. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guang J; Liu QP; Hopson R; Williard PG Lithium Pinacolone Enolate Solvated by Hexamethylphosphoramide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 7347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neufeld R; Stalke D Accurate Molecular Weight Determination of Small Molecules via DOSY-NMR by Using External Calibration Curves with Normalized Diffusion Coefficients. Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Algera RF; Ma Y; Collum DB Sodium Diisopropylamide: Aggregation, Solvation, and Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williard explicitly uses DOSY to study solvation:; Tai O; Hopson R; Williard PG Ligand Binding Constants to Lithium Hexamethyldisilazide Determined by Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 6223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Jermaks J; Tallmadge EH; Keresztes I; Collum DB Lithium Amino Alkoxide-Evans Enolate Mixed Aggregates: Aldol Addition with Matched and Mismatched Stereocontrol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sott R; Granander J; Hilmersson G Solvent-Dependent Mixed Complex Formation—NMR Studies and Asymmetric Addition Reactions of Lithioacetonitrile to Benzaldehyde Mediated by Chiral Lithium Amides. Chem. Eur. J 2002, 8, 2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jacobson MA; Keresztes I; Williard PG On the Mechanism of THF Catalyzed Vinylic Lithiation of Allylamine Derivatives: Structural Studies Using 2-D and Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Also, see ref 8f.

- 24.The intended mole fraction refers to the mole fraction based on what was added to the samples. The measured mole fraction—the mole fraction within only the ensemble of interest—eliminates the distorting effects of impurities.

- 25. Slow aggregate equilibration for even simple enolates at −78 °C is a phenomenon with potentially significant consequences8a,d,e that may be underappreciated by many practitioners.

- 26.Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Li X; Caricato M; Marenich AV; Bloino J; Janesko BG; Gomperts R; Mennucci B; Hratchian HP; Ortiz JV; Izmaylov AF; Sonnenberg JL; Williams-Young D; Ding F; Lipparini F; Egidi F; Goings J; Peng B; Petrone A; Henderson T; Ranasinghe D; Zakrzewski VG; Gao J; Rega N; Zheng G; Liang W; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Throssell K; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd JJ; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Keith TA; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Millam JM; Klene M; Adamo C; Cammi R; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Farkas O; Foresman JB; Fox DJ Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Mardirossian N; Head-Gordon M Thirty years of density functional theory in computational chemistry: an overview and extensive assessment of 200 density functionals. Mol. Phys 2017, 115, 2315. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang Y; Verma P; Jin X; Truhlar DG; He X Revised M06 density functional for main-group and transition-metal chemistry. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 2018. 115, 10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao Y; Truhlar DG The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Function. Theor. Chem. Acc 2008, 120, 215. [Google Scholar]; (d) Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Marenich AV; Cramer CJ; Truhlar DG Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2009, 113, 6378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jensen F Unifying General and Segmented Contracted Basis Sets. Segmented Polarization Consistent Basis Sets. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2014, 10, 1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Pritchard BP; Altarawy D; Didier B; Gibson TD; Windus TL New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2019, 59, 4814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Legault CY; CYLview, 1.0b; Université de Sher-brooke, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.For leading references to computations of lithium enolate alkylations, see; (a) Ikuta Y; Tomoda S Origin of Stereochemical Reversal in Meyers-Type Enolate Alkylations. Importance of Intramolecular Li Coordination and Solvent Effects. Org. Lett 2004, 6, 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Elango M; Parthasarathi R; Subramanian V; Chat-taraj PK Alkylation of Enolates: An Electrophilicity Perspective Int. J. Quant. Chem 2006, 106, 852. [Google Scholar]; Also, see ref 8.

- 29.In general, lower aggregates are promoted by higher steric demands and anion stabilization. High concentrations or strongly coordinating solvents often promote lower aggregates, but sweeping statements about the influence of solvation on aggregation can be misleading.

- 30.We did, however, notice a measurable downfield shift in the 6Li resonance of monomeric 8t with added pyridine, which could be construed as additional cooperative solvation with accompanying cleavage of the chelate.

- 31.(a) Tsunoda T; Sasaki O; Itô S Aza-claisen rearrangement of amide enolates. Stereoselective synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted carboxamides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 727. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kanemasa S; Nomura M; Yoshinaga S;Yamamoto H High Enantiocontrol of Michael Additions by Use of 2,2-Dimethyloxazolidine Chiral Auxiliaries. Exclusively ul,lk-1,4-Inductive Michael Additions of the Lithium (Z)-Enolate of (S)-4-Benzyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-3-propanoyl-oxazolidine to α,β-Unsaturated Esters. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 10463. [Google Scholar]; (c) Manthorpe JM; Gleason JL Stereoselective Generation of E- and Z-Disubstituted Amide Enolates. Reductive Enolate Formation from Bicyclic Thioglycolate Lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Evans DA; Takacs JM Enantioselective Alkylation of Chiral Enolates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 4233. [Google Scholar]; (e) Evans DA; Bartroli J: Shih TL Enantioselective Aldol Condensations. 2. Erythro-Selective Chiral Aldol Condensations via Boron Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1981, 103, 2127. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reich studied highly fluxional HMPA-solvated organolithiums at cryogenic temperatures below −140 °C. Hardware and solubilities limited us from this type of cryogenic study.

- 33.Mixtures of enantiomers using enolate 8t showed no detectable heterodimer, indicating it either failed to resolve spectroscopically or the two enantiomers do not mix. DFT computations suggest they should mix; we have no further insight or comment.

- 34.(a) Bruneau AM; Liou L; Collum DB Solution Structures of Lithium Amino Alkoxides Used in Highly Enantioselective 1,2-Additions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pöppler AC; Meinholz MM; Faßhuber H; Lange A; John M; Stalke D Mixed Crystalline Lithium Organics and Interconversion in Solution. Organometallics 2012, 31, 42. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prismatic hexamers with S6-symmetric cores also show 1:1 subunit ratios. 6

- 36. For leading references to structural studies of dianions, see ref 8e.

- 37.(a) Oppolzer W; Moretti R; Thomi S Asymmetric Alkylation of N-Acyl-sultams: A General Route to Enantiomerically Pure, Crystalline C(α,α)-Disubstituted Carboxylic Acid Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 5603. [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyabe H; Fujii K; Naito T Radical Addition to Oximeethers for Asymmetric Synthesis of β-Amino Acid Derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem 2003, 1, 381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Several general-purpose reviews on determining reaction mechanism:; (a) Meek SJ; Pitman CL; Miller AJM Deducing Reaction Mechanism: A Guide for Students, Researchers, and Instructors. J. Chem. Educ 2016, 93, 275. [Google Scholar]; (b) Simmons EM; Hartwig JF On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C–H Bond Functionalizations by Transition Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Collum DB; McNeil AJ; Ramírez A Lithium Diisopropylamide: Solution Kinetics and Implications for Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2007, 46, 3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Algera RF; Gupta L; Hoepker AC; Liang J; Ma Y; Singh KJ; Collum DB Lithium Diisopropylamide: Non-Equilibrium Kinetics and Lessons Learned about Rate Limitation. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh KJ; Hoepker AC; Collum DB Autocatalysis in Lithium Diisopropylamide-Mediated Ortholithiations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 18008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.“[enolate]” refers to the concentration of the monomer subunit (normality). The ligand concentrations in the plots refer to free donor solvent concentration.

- 41.Rein AJ; Donahue SM; Pavlosky MA In Situ FTIR Reaction Analysis of Pharmaceutical-Related Chemistry and Processes. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev 2000, 3, 734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) van’t Hoff JH; Cohen E; Ewan T Studies in Chemical Dynamics; Frederik Muller & Co.: Amsterdam, NL, 1896. [Google Scholar]; (b) Upadhyay SK Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Dynamics; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, NL, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashby EC; Dobbs FR; Hopkins HP Composition of Complex Aluminum Hydrides and Borohydrides, as Inferred from Conductance, Molecular Association, and Spectroscopic Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1973, 95, 2823. [Google Scholar]

- 44.The dielectric constants of substituted tetrahydrofurans are slightly lower than THF.; (a) Harada Y; Salomon M; Petrucci S Molecular Dynamics and Ionic Associations of Lithium Hexafluoroarsenate (LiAsF6) in 4-Butyrolactone Mixtures with 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran. J. Phys. Chem 1985, 89, 2006. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carvajal C; Tolle KJ; Smid J; Szwarc M Studies of Solvation Phenomena of Ions and Ion Pairs in Dimethoxyethane and Tetrahydrofuran. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1965, 87, 5548. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aromatic hydrocarbons can markedly alter chemical shifts, aggregation states, and reactivities of organolithiums even in the presence of superior donor solvents. For examples and leading references, see; (a) Reyes-Rodríguez GJ; Algera RF; Collum DB Cosolvent, and Isotope Effects on Competing Monomer- and Dimer-Based Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Godenschwager PF; Collum DB Lithium Hexamethyldisilazide-Mediated Enolizations: Influence of Chelating Ligands and Hydrocarbon Cosolvents on the Rates and Mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lucht BL; Collum DB Lithium Ion Solvation: Amine and Unsaturated Hydrocarbon Solvates of Lithium Hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 2217. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun X; Collum DB Lithium Diisopropylamide-Mediated Enolizations: Solvent-Independent Rates, Solvent-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 2452. [Google Scholar]; (e) Chadwick ST; Rennels RA; Rutherford JL; Collum DB Are n-BuLi/TMEDA-Mediated Arene Ortholithiations Directed? Substituent-Dependent Rates, Substituent-Independent Mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 8640. [Google Scholar]

- 46.The allusion to free HMPA is to correct for the decrease in the HMPA concentration owing to the doubly solvated monomer.

- 47.Gutmann V The Donor-Acceptor Approach to Molecular Interactions; Plenum: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Analogous D2d and S4 structures are well represented in the Cambridge Crystallographic Database:; Groom CR; Bruno IJ; Lightfoot MP; Ward SC The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Cryst. 2016, B72, 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The A-value of a phenyl moiety—the energy cost of placing it axial on cyclohexane—is 3.1 (kcal/mol), which is substantially larger than secondary alkyl groups. With that said, it is dangerous to use such a specific metric of steric effects for generalized statements.

- 50.Pang H; Williard PG Solid State Aldol Reactions of Solvated and Unsolvated Lithium Pinacolone Enolate Aggregates. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 130913 and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grabowski EJJ Reflections on Process Research —The Art of Practical Organic Synthesis, Abdel-Magid AF; Ragan JA, Eds. ACS Symposium Series, 870, American Chemical Society, Washington DC, 2004, Chapter 1, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 52.(a) Raiser EM; Hauser CR 1,3-Dianion of Dimethyl Sulfone and 1,1-Dianion of Benethyl Phenyl Sulfone. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 34, 3341. [Google Scholar]; (b) Langer P; Freiberg W Cyclization Reactions of Dianions in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fustier-Boutignon M; Nebra N; Mézailles N Geminal Dianions Stabilized by Main Group Elements. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. In 1983, geminal dianions of general structure PhSO2CM2Ph (M = Li, Na, and K) were isolated as solids, and a low-resolution crystal structure of the 1,1-dilithio derivative was obtained: Wanat, R. E.; Collum, D. B., unpublished. A structurally related ArSO2CLi2SiMe3 analog was eventually published.54 We treated PhSO2CH3 with three equiv n-BuLi to obtain a solid that provided 2.8 deuteria when quenched with D2O. An astute colleague recently noted that the possible reductive cleavage of aryl sulfones with tertiary alkyl groups with lithium naphthalide makes this tri-lithiated derivative an equivalent of a CLi4 synthon.

- 54.Gais HJ; Vollhardt J; Günther H; Moskau D; Lindner HJ; Braun S Solid-State and Solution Structure of Dilithium Trimethyl((Phenylsulfonyl)Methyl)Silane, a True Dilithiomethane Derivative. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 978. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ionization constants for conversion of ion pairs to free ions illustrate the enthalpic contributions of secondary-shell solvation:; Hogen-Esch TE; Smid J Studies of Contact and Solvent-Separated Ion Pairs of Carbanions. II. Conductivities and Thermodynamics of Dissociation of Fluorenyllithium, -sodium, and -cesium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1966, 88, 318. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Depue JS; Collum DB Structure and Reactivity of Lithium Diphenylamide. Role of Aggregates, Mixed Aggregates, Monomers, and Free Ions on the Rates and Selectivities of N-Alkylation and E2 Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 5524. [Google Scholar]

- 57. A marked influence of toluene on LiHMDS-mediated enolizations of oxazolidinones prompted us to conclude that “the toluene effect is most likely a ground-state stabilization.”45a.

- 58.We hasten to add that neat toluene becomes visibly viscous at −78 °C, which serves as a warning to would-be kineticists.; Santos FJV; de Castro CN; Dymond JH Standard Reference Data for the Viscosity of Toluene. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2006, 35, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayoub and coworkers pondered the possibility that open transition structures might be involved in the quaternization of a highly stabilized Oppolzer enolates:; Ayoub M; Chassaing G; Loffet A; Lavielle S Diastereoselective Alkylation of Sultam-Derived Amino Acid Aldimines Preparation of Cα-Methylated Amino Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 4069. [Google Scholar]