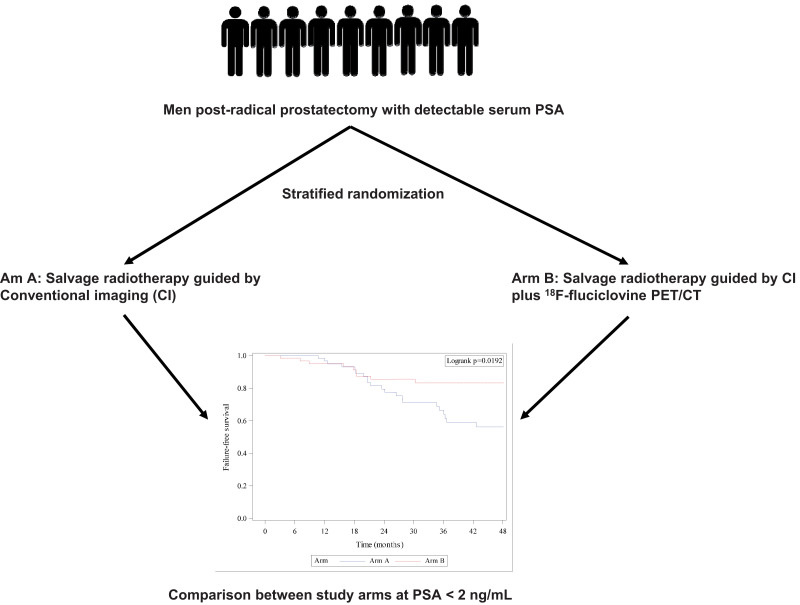

Visual Abstract

Keywords: 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, salvage radiotherapy, EMPIRE-1 trial, prostate cancer, adverse pathology, prostate-specific antigen

Abstract

The EMPIRE-1 (Emory Molecular Prostate Imaging for Radiotherapy Enhancement 1) trial reported a survival advantage in recurrent prostate cancer salvage radiotherapy (SRT) guided by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT versus conventional imaging. We performed a post hoc analysis of the EMPIRE-1 cohort stratified by protocol-specified criteria, comparing failure-free survival (FFS) between study arms. Methods: EMPIRE-1 randomized patients to SRT planning via either conventional imaging only (bone scanning plus abdominopelvic CT or MRI) (arm A) or conventional imaging plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (arm B). Randomization was stratified by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (<2.0 vs. ≥ 2.0 ng/mL), adverse pathology, and androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) intent. We subdivided patients in each arm using the randomization stratification criteria and compared FFS between patient subgroups across study arms. Results: Eighty-one and 76 patients received per-protocol SRT in study arms A and B, respectively. The median follow-up was 3.5 y (95% CI, 3.0–4.0). FFS was 63.0% and 51.2% at 36 and 48 mo, respectively, in arm A and 75.5% at both 36 and 48 mo in arm B. Among patients with a PSA of less than 2 ng/mL (mean, 0.42 ± 0.42 ng/mL), significantly higher FFS was seen in arm B than arm A at 36 mo (83.2% [95% CI, 70.0–91.0] vs. 66.5% [95% CI, 51.6–77.8], P < 0.001) and 48 mo (83.2% [95% CI, 70.0–91.0] vs. 56.2% [95% CI, 40.5–69.2], P < 0.001). No significant difference in FFS between study arms in patients with a PSA of at least 2 ng/mL was observed. Among patients with adverse pathology, significantly higher FFS was seen in arm B than arm A at 48 mo (68.9% [95% CI, 52.1–80.8] vs. 42.8% [95% CI, 26.2–58.3], P < 0.001) though not at the 36-mo follow-up. FFS was higher in patients without adverse pathology in arm B versus arm A (90.2% [95% CI, 65.9–97.5] vs. 73.1% [95% CI, 42.9–89.0], P = 0.006) at both 36 and 48 mo. Patients in whom ADT was intended in arm B had higher FFS than those in arm A, with the difference reaching statistical significance at 48 mo (65.2% [95% CI, 40.3–81.7] vs. 29.1 [95% CI, 6.5–57.2], P < 0.001). Patients without ADT intent in arm B had significantly higher FFS than patients in arm A at 36 mo (80.7% [95% CI, 64.9–90.0] vs. 68.0% [95% CI, 51.1–80.2]) and 48 mo (80.7% [95% CI, 64.9–90.0] vs. 58.6% [95% CI, 41.0–72.6]). Conclusion: The survival advantage due to the addition of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to SRT planning is maintained regardless of the presence of adverse pathology or ADT intent. Including 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to SRT leads to survival benefits in patients with a PSA of less than 2 ng/mL but not in patients with a PSA of 2 ng/mL or higher.

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is one of the treatment choices offered to patients with localized prostate cancer (PCa) (1). After RP, recurrence manifests as a rising level of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (2). Early detection of recurrence followed by salvage therapy is crucial for a favorable outcome (3). Salvage radiotherapy (SRT) with or without androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) is recommended for biochemical recurrence of PCa (4). SRT can be curative if the irradiation volume encompasses all the sites of PCa recurrence (5). Imaging for lesion localization, therefore, plays a critical role in SRT planning.

Conventional imaging with MRI, CT, and radionuclide bone scintigraphy has traditionally been used for restaging and SRT planning. The performance of these conventional imaging modalities is heterogeneous across studies, with low lesion detection rates at a PSA level of less than 2.0 ng/mL, a level at which SRT may be curative (5,6). Several radionuclide probes targeting different epitopes in the PCa cells were subsequently developed to address the limited diagnostic performance of conventional imaging at low PSA levels and improve the lesion detection rate in biochemical recurrence of PCa before SRT. 18F-fluciclovine is a radiofluorinated synthetic amino acid transported into PCa cells (7,8). One of the strengths of 18F-fluciclovine PET imaging of PCa recurrence is its lack of significant early bladder excretion, allowing for detection of recurrence in the prostate bed (9,10). Our group and others have shown the high diagnostic performance of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, even at low PSA levels (11–13). We have also reported a high impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT on therapy decisions during SRT planning (14).

The ability of SRT to lead to a decline in serum PSA level to below detectable limits and maintain disease control is the ultimate measure of the correctness of treatment decisions during radiotherapy planning. Unfortunately, most studies have focused on lesion detection rate and management change rather than the outcome of such decisions. Recently, the EMPIRE-1 (Emory Molecular Prostate Imaging for Radiotherapy Enhancement 1) study, a phase 2/3 trial that randomized patients with detectable serum PSA after RP to either conventional imaging only or conventional imaging plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to guide SRT, reported a significantly longer time to failure (failure-free survival, or FFS) for conventional imaging plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT than for imaging only (15). The difference in the time to failure between arms was the primary aim for which the study was prospectively powered. Yet, the EMPIRE-1 trial also stratified patients using 3 criteria (serum PSA level < 2 ng/mL vs. ≥ 2 ng/mL; presence or absence of adverse pathologic features, including extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and presence of lymph node metastases at RP; and ADT intent) that are known to influence SRT outcomes in patients with PCa recurrence (16,17). This stratified randomization afforded the opportunity to evaluate the impact of these characteristics known to affect SRT outcomes in post-SRT patients with PCa. We therefore performed a secondary analysis of the EMPIRE-1 trial cohort stratified by protocol-specified criteria and compared FFS between study arms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a secondary analysis of data from the EMPIRE-1 trial (NCT01666808). EMPIRE-1 is a phase 2/3 controlled trial that randomized patients with detectable serum PSA after RP to SRT guided by conventional imaging only or conventional imaging plus abdominopelvic 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. Details on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, randomization and masking, protocols for conventional imaging and 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, and outcome assessment have been published previously (15). Briefly, patients with detectable serum PSA after RP for adenocarcinoma of the prostate gland without evidence of systemic metastases on conventional imaging were randomized to undergo no additional imaging (arm A) versus additional 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT for guiding the SRT decision. Systemic metastasis was defined as any site of metastasis outside the pelvic field of SRT. Conventional imaging included whole-body planar bone scintigraphy and abdominopelvic CT or MRI. Exclusion criteria were a history of previous pelvic radiotherapy, a European Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of at least 3, the presence of contraindications to radiotherapy, a previous invasive malignancy within the 3 y preceding enrollment, and severe concurrent illness. All trial subjects gave written informed consent. The institutional review board of Emory University approved the study.

Randomization

Randomization into the study arms was in a ratio of 1:1 and was stratified by serum PSA level (<2.0 vs. ≥ 2.0 ng/mL), presence of adverse pathology at RP (extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node metastasis: none vs. any), and ADT intent (yes vs. no).

Image Analysis

Conventional images and 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT images were interpreted by 2 experienced readers independently. They read the 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT images on a MIMVista Workstation (MIM Software Inc.) without knowing the findings of conventional imaging or the clinicopathologic history of the patients. Disagreements between the readers were resolved by consensus.

Treatment

In the conventional imaging–only arm, SRT decisions were based on the standard-of-care practice and were guided by the presurgical disease features, pathologic features of the RP specimen, and PSA trajectory. In the arm using conventional imaging plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, SRT decisions were guided by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings. No on-trial radiotherapy was given to patients with extrapelvic findings. Patients with pelvic findings received 64.8–70.2 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions to the prostate bed and 45.0–50.4 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions to the pelvis. Patients with prostate-only findings and those with negative 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT findings received 64.8–70.2 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions to the prostate bed only.

Follow-up and Outcome Determination

After SRT, all patients were followed up at 1 mo, 6 mo, and every 6 mo thereafter for 36 mo after SRT. Longer follow-up was permitted for patients who had not experienced treatment failure at 36 mo after SRT. During each follow-up visit, treatment failure was evaluated clinically with physical examination and biochemically with serum PSA level determination. We defined treatment failure as a rise in serum PSA by 0.2 ng/mL above the nadir achieved after SRT, followed by another rise in a subsequent measurement; failure to achieve a decline in serum PSA after SRT; failure based on imaging or clinical examination (including digital rectal examination) findings; or the initiation of systemic therapy (18). We defined FFS as the duration from the completion of SRT to the date that failure was confirmed.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary endpoint of the RCT, a sample of 146 patients, including 73 in each arm, was calculated to detect a 20% difference in 3-y FFS between the arms at a 0.05 level of confidence with 80% power. We set an overall enrollment target of 162 participants, assuming a 10% dropout rate. We used the z test to compare FFS between arms (15).

For the current investigation, we subsequently stratified patients in the 2 arms by the protocol-specified stratification criteria (PSA < 2.0 vs. ≥ 2.0 ng/mL, presence vs. absence of any adverse pathology at RP, and yes vs. no to ADT intent) and compared FFS between study arms at 3 and 4 y using the z test (19). In addition to dichotomizing each study arm by a PSA cutoff of 2 ng/mL for comparison, we performed exploratory comparisons between study arms using the z test at different PSA levels (<0.5, <1.0, and <2.0 ng/mL). We set statistical significance at a P value of less than 0.05. We performed statistical analysis using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

RESULTS

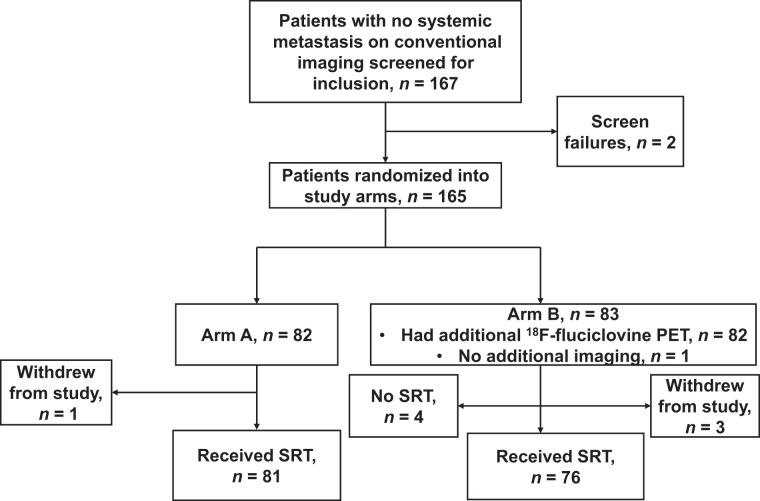

In total, 167 patients without systemic metastasis on conventional imaging were screened for inclusion. Two patients failed screening, and 165 patients were randomized, with 82 being allocated to arm A (conventional imaging only) and 83 to arm B (conventional imaging plus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT). One patient in arm A and 3 in arm B withdrew from the study after randomization. The remaining 81 patients in arm A received SRT without additional imaging. Of the remaining 80 patients in arm B, 79 had additional 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, whereas PET/CT could not be performed in 1 patient because of technical issues. Four patients in arm B had extrapelvic sites of metastasis and were excluded from undergoing SRT. Finally, 81 patients in arm A and 76 in arm B received SRT, and their data are presented in this work (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart showing patient recruitment and randomization into study arms.

Table 1 compares the patients in both arms according to the baseline clinicopathologic characteristics and the criteria applied in stratifying patients to study arms. Baseline PSA, presence of any adverse pathology, and ADT intent were stratification criteria and, hence, were similar between arms. Age and Gleason scores at RP were also similar between groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Randomized into Study Arms

| Characteristic | Arm A (n = 81) | Arm B (n = 76) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61 (55–68) | 61 (57–68) |

| Baseline PSA (ng/mL) | 0.34 (0.13–0.95) | 0.34 (0.18–1.10) |

| <2 | 69 (85.2) | 66 (86.8) |

| ≥2 | 12 (14.8) | 10 (13.2) |

| Any adverse pathology | ||

| Present | 61 (75.3) | 53 (69.7) |

| Absent | 20 (24.7) | 23 (13.2) |

| ADT intent | ||

| Yes | 28 (34.6) | 27 (35.5) |

| No | 53 (65.4) | 49 (64.5) |

| Gleason score | ||

| <8 | 52 (64.2) | 53 (69.7) |

| ≥8 | 29 (35.8) | 23 (30.3) |

Qualitative data are number and percentage; continuous data are median and interquartile range.

In arm A, 56 patients (69.1%) received radiation to the prostate bed alone, whereas 25 (30.9%) received radiation to the prostate bed and pelvis. Among patients in arm B whose SRT decision was guided by findings on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, 41 (53.9%) received radiation to the prostate bed alone, whereas 35 (46.1%) received radiation to the prostate bed and the pelvis.

The median follow-up was 3.5 y (95% CI, 3.0–4.0 y). At the 36-mo follow-up, 22 and 15 patients had experienced treatment failure in arms A and B, respectively. In arm A, FFS was 63.0% and 51.2% at the 36- and 48-mo follow-ups, respectively, whereas in arm B, FFS was 75.5% at both the 36- and the 48-mo follow-ups.

Among patients with a PSA level of less than 2 ng/mL, 66.5% and 83.2% in arms A and B, respectively, were failure-free at the 36-mo follow-up (P < 0.001), whereas 56.2% and 83.2%, respectively, were failure-free at the 48-mo follow-up (Table 2). Among patients with a PSA level of 2 ng/mL or higher, 40.4% and 26.3% in arms A and B, respectively were failure-free at 36-mo follow-up, whereas 0% and 26.3%, respectively, were failure-free at 48 mo after SRT.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of FFS Rates Between Arms Stratified According to PSA, Adverse Pathology, and ADT Intent

| Stratification criterion | Follow-up time (mo) | Arm A (%) | Arm B (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSA | ||||

| <2 ng/mL | 36 | 66.5 (51.6–77.8) | 83.2 (70.0–91.0) | <0.001* |

| 48 | 56.2 (40.5–69.2) | 83.2 (70.0–91.0) | <0.001* | |

| ≥2 ng/mL | 36 | 40.4 (9.8–70.2) | 26.3 (4.0–57.5) | 0.231 |

| 48 | 0.0 (NA–NA) | 26.3 (4.0–57.5) | NA | |

| Adverse pathology | ||||

| Present | 36 | 59.9 (43.7–72.8) | 68.9 (52.1–80.8) | 0.085 |

| 48 | 42.8 (26.2–58.3) | 68.9 (52.1–80.8) | <0.001* | |

| Absent | 36 | 73.1 (42.9–89.0) | 90.2 (65.9–97.5) | 0.006* |

| 48 | 73.1 (42.9–89.0) | 90.2 (65.9–97.5) | 0.006* | |

| ADT intent | ||||

| Yes | 36 | 52.3 (27.7–72.1) | 65.2 (40.3–81.7) | 0.113 |

| 48 | 29.1 (6.5–57.2) | 65.2 (40.3–81.7) | <0.001* | |

| No | 36 | 68.0 (51.1–80.2) | 80.7 (64.9–90.0) | 0.008 |

| 48 | 58.6 (41.0–72.6) | 80.7 (64.9–90.0) | <0.001* |

P < 0.005.

NA = not applicable.

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs. Adverse pathology considered was extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and presence of nodal metastases in pathology specimen obtained during RP.

In our exploratory comparison of FFS at different PSA thresholds, we found significant differences between study arms (Table 3). At a PSA level of less than 0.5 ng/mL, there was no significant difference in FFS between arms A and B at the 36-mo follow-up (79.3% vs. 85.3%, P = 0.184). At 48 mo, however, FFS was significantly higher in arm B than arm A (85.3% vs. 63.2%, P < 0.001). Among patients with a PSA level of less than 1 ng/mL, FFS was significantly higher in arm B than arm A at 36 mo (84.7% vs. 72.8%, P = 0.005) and 48 mo (84.7% vs. 60.5%, P < 0.001).

TABLE 3.

Differences in FFS Between Arms A and B for SRT Planning

| Parameter | Arm A (%) | Arm B (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA < 0.5 ng/mL | |||

| n | 48 | 51 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.19 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | |

| FFS at 36 mo | 79.3 (61.3–89.6) | 85.3 (69.7–93.2) | 0.184 |

| FFS at 48 mo | 63.2 (42.8–78.1) | 85.3 (69.7–93.2) | <0.001* |

| PSA < 1 ng/mL | |||

| n | 61 | 57 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.29 ± 0.24 | 0.29 ± 0.20 | |

| FFS at 36 mo | 72.8 (56.8–83.6) | 84.7 (70.3–92.5) | 0.005* |

| FFS at 48 mo | 60.5 (43.2–74.0) | 84.7 (70.3–92.5) | <0.001* |

| PSA < 2 ng/mL | |||

| n | 69 | 66 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.41 ± 0.41 | 0.43 ± 0.43 | |

| FFS at 36 mo | 66.5 (51.6–77.8) | 83.2 (70.0–91.0) | <0.001* |

| FFF at 48 mo | 56.2 (40.5–69.2) | 83.2 (70.0–91.0) | <0.001* |

P < 0.05.

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs.

Dichotomization of patients in each arm was based on the presence of any extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, or lymph node metastasis in the surgical specimen at pathologic evaluation after RP. Among patients with any of the adverse pathologic features, 59.9% and 68.9% of patients were failure-free at the 36-mo follow-up in arms A and B, respectively (P = 0.085), and at 48 mo, FFS remained significantly higher in arm B than arm A (68.9% vs. 42.8%, P < 0.001). Among patients without any of these adverse pathologic features, FFS was also significantly higher in arm B than arm A at both 36 and 48 mo (Table 2).

On the basis of their disease-associated risk, there was ADT intent for 28 and 27 patients in arms A and B, respectively. At the 36-mo follow-up, FFS did not significantly differ between study arms (52.3% for arm A vs. 65.2% for arm B, P = 0.113). At the 48-mo follow-up, FFS was significantly higher in arm B (65.2%) than arm A (29.1%) (P < 0.001). In the cohorts of patients without ADT intent, FFS was significantly higher in arm B than arm A at 36 mo (80.7 vs. 68.0, P = 0.008) and 48 mo (80.7 vs. 58.6, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The EMPIRE-1 trial, which stratified patients into study arms on the basis of pre-SRT serum PSA level, presence or absence of adverse pathologic features, and the intent to add ADT in management, reported that SRT decisions guided by findings on18F-fluciclovine PET/CT result in a favorable FFS (15). The benefit of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT on FFS reported in the EMPIRE-1 study was at a group level. In the current study, we performed a substratification post hoc analysis of the EMPIRE-1 data to determine whether the FFS advantage conferred by adding 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to SRT planning is maintained across different patient strata. In this study, FFS was significantly higher in patients with a serum PSA of less than 2 ng/mL who underwent additional 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (arm B) for SRT planning than in patients whose SRT planning was based on conventional imaging only. At a PSA level of more than 2 ng/mL, we found no significant difference in FFS between study arms. This finding may be related to the limited number of patients with this PSA level (22 patients) in the EMPIRE-1 cohort but requires further study before definitive conclusions can be made.

SRT has been recommended at low serum PSA levels (<0.5 ng/mL) (20) because of the decrease in its benefits as PSA rises (21). Given this, we performed an explorative analysis to see whether the FFS benefit conferred by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT is retained at lower PSA levels. Indeed, FFS remained significantly higher in arm B than arm A at a PSA level of less than 1 ng/mL at both the 36- and the 48-mo follow-ups. Among patients with a PSA level of less than 0.5 ng/mL, FFS was significantly higher in arm B than arm A, with the difference reaching statistical significance at the 48-mo follow-up. This finding suggests that although the use of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT for SRT planning is beneficial in patients with a PSA of more than 0.5 ng/mL, this benefit reaches significance in the long term, and this finding may be related to the more sustained disease control seen in patients who had 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT as part of SRT planning compared with the progressive increase in failure rate over time in patients who did not.

Adverse pathologic features such as extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and the presence of nodal metastases in the pathology specimen obtained during RP are suggestive of advanced disease (17). The EMPIRE-1 trial therefore stratified patients during randomization into study arms according to the presence or absence of these adverse pathologic features. The FFS benefit conferred by incorporating 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT into SRT planning was maintained in patients with and without adverse pathologic features at the 36- and 48-mo follow-ups. In patients with adverse pathology present, the higher FFS rate seen in arm B than arm A at the 36-mo follow-up showed a trend toward statistical significance, whereas significance was clearly seen at the 48-mo follow-up, again highlighting the long-term tumor control afforded by SRT decisions guided by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT.

Adding ADT to SRT improves progression-free survival, especially in patients with high-risk disease phenotypes (16,22). To remove the confounding effect of additional ADT on SRT outcome, ADT intent was balanced between study arms. Among patients with no ADT intent, FFS was significantly higher at the 36- and 48-mo follow-ups in arm B than arm A. Among patients for whom additional ADT was planned, there was a higher FFS in arm B than arm A at the 36-mo follow-up, with the difference reaching statistical significance at the 48-mo follow-up. The improvement in FFS due to SRT conferred by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT was more prominent at the 48-mo follow-up than at the 36-mo follow-up, a finding that was consistently seen across different patient strata. Fifteen patients experienced SRT failure in arm B, all of which occurred within 36 mo of SRT. There was no further event during the 36- to 48-mo follow-up interval. Conversely, in arm A, 22 events occurred within 36 mo of SRT and a further 5 events occurred between the 36- and 48-mo follow-ups. It is notable and expected that, regardless of arm, patients with higher PSA levels, adverse histology, and ADT intent generally have lower FFS than those with lower PSA levels, no adverse histology, and no ADT intent.

Among patients randomized to arm B, 4 did not receive SRT because of detection of extrapelvic metastases on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. In these patients, 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT prevented futile SRT. In arm A, 30.9% of patients received pelvic radiotherapy in addition to radiotherapy to the prostate bed. This rate is lower than the 46.1% of patients in arm B who had pelvic radiotherapy in addition to radiotherapy to the prostate bed, a decision guided by the findings on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT. Put together, the higher FFS brought about by the incorporation of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT during SRT decision making is a result of a combination of better patient selection and more accurate radiotherapy target delineation. We previously reported that 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT had a greater impact on SRT management decisions than conventional imaging in the EMPIRE-1 cohort (14). A more favorable survival outcome in patients undergoing additional 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT, compared with patients whose SRT was guided by conventional imaging alone, suggests that the change in management decision brought about by 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT led to a favorable treatment outcome.

The detection of additional lesions on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT compared with conventional imaging is often associated with an increase in the pretreatment defined target volume (23). The higher rate of radiotherapy to the pelvis in the 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT arm in the current study, therefore, has the potential to expose such patients to radiotherapy-induced toxicities. A recent report that evaluated provider- and patient-reported SRT-induced toxicities in the EMPIRE-1 cohort did not find significant differences in the incidence of treatment-induced toxicities between study arms despite a significant increase in target volumes due to the incorporation of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT into SRT planning (24). This finding confirms that the improvement in lesion detection, SRT management decisions, and favorable SRT outcomes brought about by the incorporation of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT into SRT planning occurs without exposing the patients to a higher rate or severity of treatment-induced toxicities.

Several studies have reported the diagnostic performance of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in patients with PCa recurrence (25–28). These studies have primarily evaluated the diagnostic performance of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT or its effects on management decisions rather than the impact of imaging findings on patients’ survival. Imaging studies that randomized patients into study arms and evaluated the impact of imaging findings on survival are rare. The strength of this study, therefore, lies in its design and the choice of FFS as the study endpoint. In the EMPIRE-1 trial design, power and sample size calculations were performed for the primary aim (i.e., to detect a 20% difference in 3-y FFS between study arms). The current subgroup investigation is purely exploratory. Despite not being powered to detect differences between study arms stratified according to protocol-specified criteria, we found that the survival benefit from adding 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT was maintained across most of the strata evaluated.

Of note, though there has been a recent expansion in the use of 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT, with a few prospective single-arm trials reporting the time to failure as a study endpoint in patients whose SRT was guided by this novel imaging modality (29,30), there have been no randomized controlled trials of PSMA versus conventional imaging reported as yet in this postprostatectomy radiotherapy space. An ongoing phase III trial at the University of California Los Angeles (NCT03582774), when completed, will fill this void (31). We have an ongoing phase III trial at our institution comparing 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT versus 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT (R01CA226992, NCT03762759) for guiding SRT of PCa recurrence. The results from this trial may provide further insights on the comparative benefits of these 2 approved imaging modalities for PCa recurrence in guiding SRT management decisions.

CONCLUSION

The addition of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to conventional imaging in SRT management planning reduces the occurrence of treatment failure. This benefit is seen across different PSA levels below 2 ng/mL. This benefit is also maintained regardless of the presence versus absence of adverse pathologic features or the intention to add ADT to SRT, or not, in the treatment of PCa recurrence after RP.

DISCLOSURE

This study received funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA169188) and Blue Earth Diagnostics (fluciclovine synthesis cassettes to Emory University). Research reported in this publication was supported partly by the Biostatistics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award P30CA138292. Ashesh Jani reports personal fees from Blue Earth Diagnostics for advisory board services outside the submitted work. Mark Goodman is entitled to a royalty derived from sale of products related to the research described in this report. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. The research consent forms state that he is entitled to a share of sales royalty received by Emory University from Nihon MediPhysics under that agreement. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. David Schuster participates through the Emory University Office of Sponsored Projects in sponsored grants including those funded or partially funded by Blue Earth Diagnostics, Nihon MediPhysics, Telix Pharmaceuticals (U.S.), Advanced Accelerator Applications, FUJIFILM Pharmaceuticals USA, and Amgen and reports consultant fees outside the submitted work from Syncona, AIM Specialty Health, Global Medical Solutions Taiwan, and Progenics Pharmaceuticals. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals at Emory University for their support and assistance: Walter J. Curran, Mark McDonald, Sherrie Cooper, and the entire radiation oncology clinical trials team; the entire imaging team; Ronald J. Crowe and the entire cyclotron and synthesis team from Emory University Center for Systems Imaging; and Martin Sanda, Mehrdad Alemozaffar, and the entire urology clinical enterprise and clinical trials team. We thank all participating patients.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Is the survival advantage from adding 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT to SRT planning for PCa recurrence, as reported in the EMPIRE-1 trial, maintained in different patient subpopulations?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: The incorporation of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in SRT management decisions improved FFS across different PSA strata below 2 ng/mL. The survival benefit was retained regardless of whether adverse pathologic features were present or whether concomitant ADT was planned with SRT.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: The addition of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT SRT planning improves FFS in patients with disease recurrence after RP, and the benefit is retained across different patient categories.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eastham JA, Auffenberg GB, Barocas DA, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO guideline, part I: introduction, risk assessment, staging, and risk-based management. J Urol. 2022;208:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kupelian P, Katcher J, Levin H, Zippe C, Klein E. Correlation of clinical and pathologic factors with rising prostate-specific antigen profiles after radical prostatectomy alone for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 1996;48:249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tilki D, Preisser F, Graefen M, Huland H, Pompe RS. External validation of the European Association of Urology biochemical recurrence risk groups to predict metastasis and mortality after radical prostatectomy in a European cohort. Eur Urol. 2019;75:896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pisansky TM, Thompson IM, Valicenti RK, D’Amico AV, Selvarajah S. Adjuvant and salvage radiation therapy after prostatectomy: ASTRO/AUA guideline amendment, executive summary 2018. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019;9:208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zaorsky NG, Calais J, Fanti S, et al. Salvage therapy for prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18:643–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kane CJ, Amling CL, Johnstone PA, et al. Limited value of bone scintigraphy and computed tomography in assessing biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2003;61:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oka S, Okudaira H, Yoshida Y, Schuster DM, Goodman MM, Shirakami Y. Transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-fluoro[1-14C]cyclobutanecarboxylic acid in prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ono M, Oka S, Okudaira H, et al. [14C]fluciclovine (alias anti-[14C]FACBC) uptake and ASCT2 expression in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schuster DM, Nanni C, Fanti S, et al. Anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid: physiologic uptake patterns, incidental findings, and variants that may simulate disease. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1986–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nye JA, Schuster DM, Yu W, Camp VM, Goodman MM, Votaw JR. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the synthetic nonmetabolized amino acid analogue anti-18F-FACBC in humans. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1017–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marcus C, Abiodun-Ojo OA, Jani AB, Schuster DM. Clinical utility of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in recurrent prostate cancer with very low (≤0.3 ng/mL) prostate-specific antigen levels. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;11:406–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bulbul JE, Grybowski D, Lovrec P, et al. Positivity rate of [18F]fluciclovine PET/CT in patients with suspected prostate cancer recurrence at PSA levels below 1 ng/mL. Mol Imaging Biol. 2022;24:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salavati A, Gencturk M, Koksel Y, et al. A bicentric retrospective analysis of clinical utility of 18F-fluciclovine PET in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer following primary radiation therapy: is it helpful in patients with a PSA rise less than the Phoenix criteria? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:4463–4471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abiodun-Ojo OA, Jani AB, Akintayo AA, et al. Salvage radiotherapy management decisions in postprostatectomy patients with recurrent prostate cancer based on 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT guidance. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1089–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jani AB, Schreibmann E, Goyal S, et al. 18F-fluciclovine-PET/CT imaging versus conventional imaging alone to guide postprostatectomy salvage radiotherapy for prostate cancer (EMPIRE-1): a single centre, open-label, phase 2/3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1895–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pollack A, Karrison TG, Balogh AG, et al. The addition of androgen deprivation therapy and pelvic lymph node treatment to prostate bed salvage radiotherapy (NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT): an international, multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1886–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pisansky TM, Agrawal S, Hamstra DA, et al. Salvage radiation therapy dose response for biochemical failure of prostate cancer after prostatectomy: a multi-institutional observational study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tendulkar RD, Agrawal S, Gao T, et al. Contemporary update of a multi-institutional predictive nomogram for salvage radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3648–3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. Springer; 2003:234–237. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cornford P, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:630–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. King CR. The timing of salvage radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carrie C, Hasbini A, de Laroche G, et al. Salvage radiotherapy with or without short-term hormone therapy for rising prostate-specific antigen concentration after radical prostatectomy (GETUG-AFU 16): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jani AB, Schreibmann E, Rossi PJ, et al. Impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET on target volume definition for postprostatectomy salvage radiotherapy: initial findings from a randomized trial. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dhere VR, Schuster DM, Goyal S, et al. Randomized trial of conventional versus conventional plus fluciclovine (18F) positron emission tomography/computed tomography-guided postprostatectomy radiation therapy for prostate cancer: volumetric and patient-reported analyses of toxic effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;113:1003–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Odewole OA, Tade FI, Nieh PT, et al. Recurrent prostate cancer detection with anti-3-[18F]FACBC PET/CT: comparison with CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1773–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Solanki AA, Savir-Baruch B, Liauw SL, et al. 18F-fluciclovine positron emission tomography in men with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and planning to undergo salvage radiation therapy: results from LOCATE. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020;10:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Calais J, Ceci F, Eiber M, et al. 18F-fluciclovine PET-CT and 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET-CT in patients with early biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy: a prospective, single-centre, single-arm, comparative imaging trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1286–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scarsbrook AF, Bottomley D, Teoh EJ, et al. Effect of 18F-fluciclovine positron emission tomography on the management of patients with recurrence of prostate cancer: results from the FALCON trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ceci F, Rovera G, Iorio GC, et al. Event-free survival after 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in recurrent hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (HSPC) patients eligible for salvage therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:3257–3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emmett L, Tang R, Nandurkar R, et al. 3-year freedom from progression after 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT-triaged management in men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: results of a prospective multicenter trial. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Calais J, Czernin J, Fendler WP, Elashoff D, Nickols NG. Randomized prospective phase III trial of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT molecular imaging for prostate cancer salvage radiotherapy planning [PSMA-SRT]. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]