Abstract

With the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), machines are increasingly being used to complete complicated tasks, yielding remarkable results. Machine learning (ML) is the most relevant subset of AI in medicine, which will soon become an integral part of our everyday practice. Therefore, physicians should acquaint themselves with ML and AI, and their role as an enabler rather than a competitor. Herein, we introduce basic concepts and terms used in AI and ML, and aim to demystify commonly used AI/ML algorithms such as learning methods including neural networks/deep learning, decision tree and application domain in computer vision and natural language processing through specific examples. We discuss how machines are already being used to augment the physician's decision-making process, and postulate the potential impact of ML on medical practice and medical research based on its current capabilities and known limitations. Moreover, we discuss the feasibility of full machine autonomy in medicine.

Keywords: Algorithms, artificial intelligence, deep learning, machine learning, neural networks

INTRODUCTION

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) seeks to understand and develop computer systems that are able to perform tasks that usually require human intelligence. The most common method of classifying AI is by dichotomising it into artificial general intelligence (AGI) and artificial narrow intelligence (ANI).[1] AGI pertains to a universal algorithm for learning and acting in any environment. It is an intelligence that is at least human level – able to perform cognitive tasks in different environments and contexts that the average human is capable of. This would include tasks such as understanding context and making sense of an environment. AGI is likely impossible at the current level of development in AI.[1] ANI concerns algorithms that perform tasks within defined boundaries usually expected of a human or a domain expert. These may be single tasks such as identifying cats as opposed to dogs, translating languages, or in a more relevant context, identifying whether a skin lesion is likely to be malignant or identifying suspicious lung nodules on chest radiographs. ANI could represent what a human can do in a second.[1] This article will mainly deal with ANI.

Machine learning (ML) is considered a branch of AI. ML is defined as the ability of a machine to learn from a set of training data and knowledge to make predictions about data points outside of the initial training dataset.[2] ML does this by utilising the theory of statistics in building mathematical models, as the core task involves drawing inferences from given samples.[3] ML can be subdivided into parametric and non-parametric models. An algorithm that summarises data with a set of parameters of fixed sizes is a parametric model[4,5]; an example is a Gaussian model. Other examples of parametric models include linear regression[4] and logistic regression. By contrast, a non-parametric model, such as the k-nearest neighbour, may have more flexible parameters as it characterises from more data.[5] The model offers greater flexibility as it makes fewer assumptions about the data, but as a consequence, requires much more data to be sufficiently trained. Other examples of non-parametric models include decision tree[6] and support vector machines.[7] This article will focus on ML and attempt to improve its understanding through descriptive examples and relevant diagrams.

Another important concept with regard to the applicability of ML in medicine is supervised versus unsupervised learning. Supervised learning aims to model the inputs and the corresponding known outputs. The machine is given some examples of input (questions) with the corresponding output (the correct answers); it then learns a function to map questions to answers, frequently through classification and regression.[1] Most real-world applications employ supervised learning. An example would be the deep learning neural networks trained to recognise diabetic retinopathy and related eye diseases.[8] In the study, Ting et al.[8] found that the system had high sensitivity and specificity for identifying referable diabetic retinopathy and vision-threatening retinopathy. Conversely, the goal of unsupervised learning is to find naturally occurring patterns in the input data with no explicit feedback. Techniques such as clustering and association are the mainstay of unsupervised learning.[1] In medicine, unsupervised learning has the potential to unearth previously unknown pathophysiologic mechanisms, which could in turn lead to new treatment regimes [Table 1].[9]

Table 1.

Terminology and characteristics of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML).

| Terminology | Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial intelligence | ||

| Artificial general intelligence | Universal algorithm, functions in any environment | None currently |

|

| ||

| Artificial narrow intelligence | Specific algorithm, functions within defined boundaries | Self-driving cars, AI playing chess, poker, go[10] |

|

| ||

| Machine learning (subset of AI) | ||

|

| ||

| Parametric models | Fixed set, strong assumptions, less flexible | Linear regression, logistic regression |

|

| ||

| Non-parametric models | Fewer assumptions, greater flexibility | Decision tree, support vector machines |

|

| ||

| Supervised learning | Trained with ‘correct’ answers | (Supervised) Deep learning system[8] |

|

| ||

| Unsupervised learning | No explicit feedback, finds patterns | K-means,[11] means shift[12] |

MACHINE LEARNING IN MEDICINE: THE PRESENT

The use of algorithms should not be foreign to the medical fraternity. Simply put, an algorithm is a sequence of instructions carried out to transform input to output.[3] A commonly used ML algorithm is a decision tree; to draw parallels to algorithms used in clinical practice, consider the use of flowcharts in many of our work processes. An example would be the Ministry of Health's clinical practice guidelines on diabetes mellitus 2014 [Figure 1].[13] The input data in this context is the blood glucose level, and within set parameters, the flowchart will provide an accurate output, which, in this case, is a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, or otherwise.

Figure 1.

Flowchart shows the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus when fasting glucose is not ≥7.0 mmol/L or casual/2-hr post-challenge glucose is not ≥11.1 mmol/L.[13]

Besides the similarities noted between medical flowcharts and decision tree algorithms, clinical scoring systems and supervised learning also share some similarities. The widespread use of clinical scoring systems for diagnosis (e.g. Wells Criteria[14]), prognosis (Model for End Stage Liver Diseases score[15]) and determination of the risk of developing a disease (Framingham Risk score[16]) will likely make it easier for clinicians to understand the basis of supervised learning. Consider 'Estimation of 10-Year Coronary Artery Disease Risk for Men' from the Ministry of Health's clinical practice guidelines for lipids 2016,[17] which predicts the ten-year risk of developing coronary artery disease in men by analysing features such as age, race, total cholesterol, smoking status and blood pressure. Clinical scoring systems are analogous to supervised learning; instead of having the researchers weigh the features and generate a model that matches the population data, an ML algorithm adjusts the weightages by itself to match the output.

Now let us take a look at a few descriptive examples of different ML algorithms in various medical fields to see how far machines have come, before we move on to discuss the future of machines in medicine.

Example 1: computer vision with convolutional neural network

Computer vision is a subset of AI that encompasses the ability of a computer to gain understanding through exposure to digital images or videos.[18] Tasks such as detection, segmentation and classification can be typically performed with computer vision, although effective complete automation of these tasks has been challenging despite numerous developments in computer vision.[19] However, through the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the utility of computer vision can be taken to the next level. A CNN, which is a subset of AI and ML, is a specialised type of computational model inspired by the neurons and synapses in the human brain.[3] The basic unit of a neural network is the perceptron, which is a single layer of computational neurons[20] [Figure 2]. Addition of more layers between the input and the output makes a neural network[21] [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Diagram shows single layer of computational neurons.[20]

Figure 3.

Diagram shows addition of more layers to make a neural network.[21]

One of the key advancements in neural networks comes in the form of convolutional layers instead of a fully connected layer plus deep structure. An example is an award-winning CNN (2014 ImageNet Competition) developed by Google (Mountain View, CA, USA) named GoogleNet, which is 22 layers deep and combined with different convolutional kernels (patches). Cicero et al. re-trained GoogleNet to detect cardiomegaly, pulmonary oedema, consolidation, pleural effusion and pneumothorax on single-view posterior-anterior frontal chest radiographs.[22] It was trained with over 30,000 images and was subsequently tested against a set of approximately 2,400 images. The network managed to accurately diagnose 90% of normal chest films and those with pleural effusions. However, it showed slightly worse diagnostic efficacy with regard to the other pathologies (i.e. cardiomegaly, oedema, consolidation and pneumothorax). The study proved that CNNs have the potential to differentiate normal from abnormal with a relatively high confidence, although diagnosing the actual pathology might prove to be difficult at times. The team expressed difficulties in obtaining a large quantity of well-labelled data with a good balance of pathologies, which may skew the algorithm's training. The team also needed to downsize the resolution of the images to reduce the data burden, which may have affected the network's accuracy in picking up subtle changes.

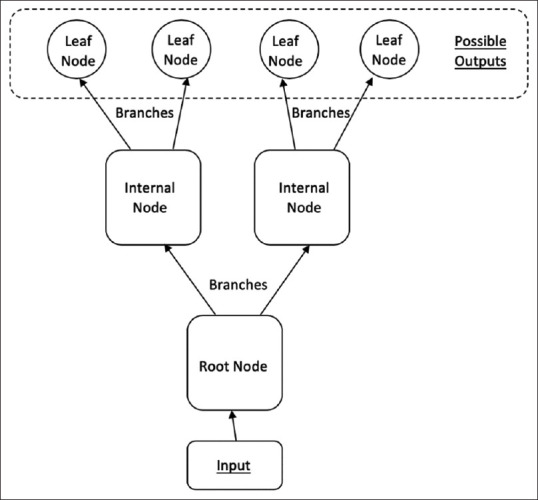

Example 2: decision tree and random forest

A decision tree takes an input and returns a 'decision' as an output.[1] We alluded to this familiar structure earlier in the form of medical flowcharts. A tree is made up of nodes and branches. Each node takes a single input and may generate a range of possible outputs via the branches. The final decision is essentially a path going through several nodes through the branches, arriving at a final leaf output or decision.[1] Figure 4 shows the anatomy of a decision tree.[3] A random forest is, as its name implies, a collection of individual decision trees. Individual, uncorrelated decision trees are placed in an ensemble and the individual errors of each tree are cancelled out in the final output.[3]

Figure 4.

Diagram shows the anatomy of a decision tree.[3]

Hsich et al.[23] compared a random survival forest of 2,000 trees (with each tree constructed on a bootstrap sample from the original cohort) against the conventional Cox regression statistical model in terms of identifying important risk factors for survival in patients with systolic heart failure. In this case, decision trees were used for two tasks: identification of variables for predictors of survival; and prediction of patient survival. By inspecting individual trees, the researchers were able to identify that the three most important predictive variables were peak oxygen consumption, serum urea nitrogen and treadmill exercise time. With regard to the prediction performance in terms of patient survival, the random survival forest model was as competitive as the traditional Cox proportional hazard model.

Example 3: support vector machines and natural language processing

Support vector machines (SVMs) are commonly used for classification tasks in case of outliers or non-linearities.[24] An SVM algorithm is an example of supervised learning; it is able to separate labelled input data by a wide gap. The SVM is able to place new data into either category after being informed of the characteristics of the gap. Furthermore, SVM can classify examples that are not traditionally linearly separable by generating a hyperplane derived from input data after using a non-linear kernel method [Figure 5].[3]

Figure 5.

Graph shows data that is not traditionally linearly separable can be projected into a higher dimensional space, which can make it linearly separable. [Adapted from: Alpaydin E. Introduction to Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004]

Natural language processing (NLP) is a wide field encompassing many different tools and concepts, aimed at letting machines have some basic competency in another human skill that is taken for granted, i.e., language. NLP involves extracting features from free-text documents, making inferences and eventually mapping to predicted outcomes. Machines should be able to perform NLP for communication and acquisition of information, perhaps even knowledge.[1]

Goodwin et al. utilised SVMs in conjunction with other ML techniques to conceive a novel method for automatically recognising symptom severity by using NLP of psychiatric evaluation records of patients. The algorithm extracted features from the psychiatric evaluation records and an SVM was used to map the severity score into one of the four discrete severity levels.[25]

In the above study, the researchers had to employ multiple ML techniques including a hybrid model to train a machine to do what a physician does naturally – stratification based on clinical notes. Of course, we can argue that a trained physician will be able to glean much more than just disease severity from well-written medical records; however, if a machine is able to trawl through dense medical notes and provide an accurate assessment of a given parameter (in this case, disease severity), it can potentially be an immense help for the time-starved physician.

The three examples above are newer ML techniques that have emerged in the 21st century. However, research has shown that older ML tools, such as linear regression and principal component analysis, remain the mainstay in biomedical research.[26] Other ML techniques still being used in biomedical research include t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding and Markov model.[26]

A HYPOTHETICAL SCENARIO: CLINIC CONSULTATION

Let us consolidate what we have learnt through a hypothetical situation. Mr A goes to his family physician, Dr B, for an episode of acute onset breathlessness and decreased effort tolerance. Mr A has a history of coronary artery bypass grafting and is usually on fluid restriction of 1 L per day. It is a busy day in Dr B's clinic, with more than ten patients in line after Mr A. After completing his consultation notes for Mr A, Dr B's newly acquired heart failure SVM + NLP algorithm flashes a pop-up on his computer, stating that Mr A's symptoms exhibit high-risk features. Dr B does his due diligence and refers Mr A to the emergency department for further management. Mr A heads over to the emergency department and undergoes chest radiography. The emergency department's state-of-the-art computer vision and CNN algorithm diagnoses cardiomegaly and pleural effusions in Mr A's chest radiograph. Mr A eventually gets admitted to the cardiology unit. The cardiologist on duty orders some blood tests and inputs these blood test results into his innovative decision tree and random forest algorithm, which predicts that Mr A has a great chance of survival, despite his acute symptoms. Mr A is then discharged well a week later with an increased dose of diuretics and has even downloaded a new app on his phone to keep track of his fluid restriction!

MACHINE LEARNING IN MEDICINE: CHALLENGES AND THE POSSIBLE FUTURE

Maintaining privacy

Although these algorithms may seem promising, they pose unique challenges to medical practitioners. ML relies on copious amounts of data in order to be effective. In medicine, protection of patient's personal data is paramount. This has been illustrated by the events involving the Royal Free London Trust and DeepMind, where there was a lack of safeguarding of patient data that were handed to Google DeepMind. The millions of identified individuals in the dataset had not provided consent and were not informed prior to the data transfer to DeepMind.[27] Following the incident, the Royal Free Trust had to sign a new agreement that complies with data protection law.[28] Some experts have attempted to minimise data privacy violation when training ML algorithms,[29] although it is unlikely that this method will reduce the mismanagement of sensitive data to zero.

Quality control

All algorithms in ML including regression, deep learning and SVM use the theory of statistics in building mathematical models. It is a probabilistic process, which implies that users of this tool should expect certain percentages of error, rather than demand absolute certainties in the outputs. Hence, users should define acceptable margins of error before embarking on ML projects.

Explainability

The concept of 'black-box decision-making' has been touched upon by numerous studies.[30,31] Some ML algorithms (i.e. CNNs) make indecipherable calculations, which make it challenging for physicians to detect error or bias in the decision-making process.[32] This is a key concern because if we are unable to explain to our patients how we arrived at a diagnosis, treatment plan or prognosis, we cannot expect their trust in return.

Patient safety

As clinicians, we are trained to err on the side of caution when faced with a diagnostic dilemma, especially if there is a potentially serious outcome, even if it is at the cost of our diagnostic accuracy. Machines do not execute this behavioural shift when faced with the same situation[33]; yet, this is critical to patient safety. Therefore, machines in clinical care must be trained to be less insensitive to the impact of their decisions.[34]

It is known that machines struggle with distributional shift.[35] In other words, machines are poor at identifying a change in context, which will lead them to make repeated erroneous estimates. A group of expert dermatologists found that their algorithm that was trained with images of lesions biopsied in the clinic does not perform as well when screening the general population, where the appearances and risk profiles of patients differ.[33] Compare this with a clinician; when confronted with a novel situation, we will recognise that there is a gap in expertise and take appropriate action, thus minimising poor patient outcome.

Last but not the least, automation may breed complacency and bias.[36] Clinicians may accept the guidance of a machine and be less vigilant in searching for contrary evidence, or worse, the ground truth, in clinical judgement.[37] To avoid compromising patient safety, it is even more pertinent that doctors have knowledge of the technologies that are or will be deployed as well as understand the limitations and pitfalls of such technologies (including ML), regardless of how complex and reliable the technologies may seem. A simple example would be of the false normal readings given by pulse oximetry devices in carbon monoxide poisoning because standard pulse oximeters cannot differentiate between oxyhaemoglobin and carboxyhaemoglobin.[38] Ultimately, although it is the responsibility of the providers of automative technologies to clearly state the safety boundaries of their product, clinicians who utilise these inventions must remain cognisant of their limitations.

Current ML capability tends to be narrow in focus and likely limited by the data it learnt from, and machines still lack 'common sense' and broad real-world knowledge. Medical care will remain very much an art and a science, and it is very unlikely for machines to easily learn the deep subtleties of history-taking and physical examinations performed by experienced practitioners. Physicians of the future will still need to maintain sharp clinical acumen, while being ready to utilise all available ML tools to augment their ability to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and practise sound clinical decision-making.

In view of the above challenges, we speculate that full machine autonomy (like in self-driving cars[39]) is very unlikely in the foreseeable future. However, that fact that physicians are not likely to be replaced does not mean that the practice of medicine will continue unchanged. We believe that AI and ML, especially deep learning, will impact our practice in ways yet to be known. In the next section, we will focus on the aspects of medicine that will be influenced the most.

PROMISES AND THE POSSIBLE FUTURE

We believe that machines have the potential to impact the practice of medicine in the tasks of screening, diagnosis, analysis, treatment and medical research.

Screening, diagnosis and analysis

Consider diseases that are difficult to 'catch', such as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF). With the use of smartphones and wearables, deep learning algorithms have been proven to detect paroxysmal AF using photoplethysmographic monitoring with high diagnostic accuracy.[40] Extrapolating from this example, asymptomatic patients may benefit from noninvasive screening tools that incorporate technology and AI/ML, thus leading to greater uptake and improved diagnoses.

We all remember a mantra taught to generations of doctors: 'Common things occur commonly'. It is now clear that machines have the potential to outdo humans at something we thought we were good at – pattern recognition. Computer vision, NLP and various algorithms represent a paradigm shift in how we appreciate patterns, sifting through large amounts of data in a short span of time, with similar, if not better, accuracy compared with that of human experts. The data can be visual, including dermatology pictures,[33] pathology slides,[41,42] radiological images[2,43] and free text.[25] As we take large strides into the world of big data, massive datasets of images can be used to 'train' data-hungry algorithms to draw conclusions on inputted data and issue an almost instantaneous report, within certain limitations. How will we define and convey these limitations? Consider the reasons for which clinicians perform investigations – usually to rule in or rule out conditions that the clinician already has in mind, e.g., intracranial haemorrhage. A computer vision-based ML tool may assess a head CT and deliver the output: intracranial haemorrhage detected (likelihood 75%). This will differ from a radiologist's assessment, which will include more details and analysis, e.g., the presence of mass effect or a concomitant skull fracture. As such, ML algorithms might play a greater role in situations where a radiologist's deep analysis is not essential. Consider the measurement of lesions in follow-up imaging for multiple lung nodules or mammography for known breast lesions. These are tedious and time-consuming tasks that may be fully automated in future.

Treatment

ML algorithms have also made inroads in augmenting physicians with treatment, assisting them with certain steps in treatment procedures to achieve better outcomes. For example, a Singapore-based company announced an AI platform that aims to improve our understanding of the response of cancer cells to different drugs, and combines this information with micro-tumour technology to individualise patient treatment, potentially accelerating drug discovery and future cancer therapy development.[44]

Medical research

In the field of research, the potential of automated literature review and consolidation of up-to-date knowledge in a short span of time is within the capabilities of current technology. Chinese developers have created a specialised healthcare search engine AskBob, which is said to have amalgamated millions of medical resources and evidence into an unprecedented knowledge bank. The inventors of AskBob are already collaborating with the National University Health System, Singapore, and the SingHealth group, Singapore, to enable smarter medical literature research and trend analysis.[45] If we can ensure anonymity and patient data protection, AI will have a pivotal part to play in medical knowledge maintenance.

CONCLUSION

Going forward, what are some strategies that physicians can employ to maintain their competitive advantage in the face of this technological disruption? We refer to an article by Liew that adapted Porter's framework[46] in strategising for the future.[47] Let us continue to differentiate ourselves from AI, while not losing focus on what matters most: our patients. The time freed up by the increased productivity and efficiency should be spent with patients, lest we forget that the practice of medicine is as much an art as much as a science.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russell SJ, Norvig P. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson BJ, Korfiatis P, Akkus Z, Kline TL. Machine learning for medical imaging. Radiographics. 2017;37:505–15. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpaydin E. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. Introduction to Machine Learning. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt AF, Finan C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;98:146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wey A, Connett J, Rudser K. Combining parametric, semi-parametric, and non-parametric survival models with stacked survival models. Biostatistics. 2015;16:537–49. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach Learn. 1986;1:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christianini N, Shawe-Taylor J. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2000. An Introduction to Support Vector Machines and Other Kernel-Based Learning Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ting DSW, Cheung CY, Lim G, Tan GSW, Quang ND, Gan A, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning system for diabetic retinopathy and related eye diseases using retinal images from multiethnic populations with diabetes. JAMA. 2017;318:2211–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.18152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. 2015;132:1920–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meskó B, Hetényi G, Györffy Z. Will artificial intelligence solve the human resource crisis in healthcare? BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:545. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3359-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna K, Murty MN. Genetic K-means algorithm. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part B Cybern. 1999;29:433–9. doi: 10.1109/3477.764879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comaniciu D, Meer P. Mean shift: A robust approach toward feature space analysis. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2002;24:603–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Diabetes Mellitus. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available fro: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/cpg_diabetes-mellitus-booklet---jul-2014.pdf .

- 14.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Stiell I, Dreyer JF, Barnes D, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: Management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Lipids. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/moh-lipids-cpg---booklet.pdf .

- 18.Ballard DH, Brown CM. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1982. Computer Vision. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chartrand G, Cheng PM, Vorontsov E, Drozdzal M, Turcotte S, Pal CJ, et al. Deep learning: A primer for radiologists. Radiographics. 2017;37:2113–31. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo L. New York, NY: Garland Science; 2015. Principles of Neurobiology. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2016. Deep Learning. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cicero M, Bilbily A, Colak E, Dowdell T, Gray B, Perampaladas K, et al. Training and validating a deep convolutional neural network for computer-aided detection and classification of abnormalities on frontal chest radiographs. Invest Radiol. 2017;52:281–7. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsich E, Gorodeski EZ, Blackstone EH, Ishwaran H, Lauer MS. Identifying important risk factors for survival in patient with systolic heart failure using random survival forests. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:39–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.939371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brereton RG, Lloyd GR. Support vector machines for classification and regression. Analyst. 2010;135:230–67. doi: 10.1039/b918972f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin TR, Maldonado R, Harabagiu SM. Automatic recognition of symptom severity from psychiatric evaluation records. J Biomed Inform. 2017;75S:S71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koohy H. The rise and fall of machine learning methods in biomedical research. Version 2. F1000Res. 2017;6:2012. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powles J, Hodson H. Google DeepMind and healthcare in an age of algorithms. Health Technol (Berl) 2017;7:351–67. doi: 10.1007/s12553-017-0179-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suleyman M, King D. The Information Commissioner, the Royal Free, and what we've learned. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://deepmind.com/blog/announcements/ico-royal-free .

- 29.Papernot N, Abadí M, Erlingsson Ú, Goodfellow I, Talwar K. Semi-supervised knowledge transfer for deep learning from private training data. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/16100.05755 .

- 30.Kusunose K, Haga A, Abe T, Sata M. Utilization of artificial intelligence in echocardiography. Circ J. 2019;83:1623–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H, Yune S, Mansouri M, Kim M, Tajmir SH, Guerrier CE, et al. An explainable deep-learning algorithm for the detection of acute intracranial haemorrhage from small datasets. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019;3:173–82. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Challen R, Denny J, Pitt M, Gompels L, Edwards T, Tsaneva-Atanasova K. Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:231–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542:115–8. doi: 10.1038/nature21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Megler V, Gregoire S. Training models with unequal economic error costs using Amazon Sagemaker. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/machine-learning/training-models-with-unequal-economicerror-costs-using-amazon-sagemaker/

- 35.Amodei D, Olah C, Stainhardt J, Christiano P, Schulman J, Dan Mané. Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv. 2016. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06565 .

- 36.Parasuraman R, Manzey D. Complacency and bias in human use of automation: An attentional integration. Hum Factors. 2010;52:381–410. doi: 10.1177/0018720810376055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai TL, Fridsma DB, Gatti G. Computer decision support as a source of interpretation error: The case of electrocardiograms. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:478–83. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan ED, Chan MM, Chan MM. Pulse oximetry: Understanding its basic principles facilitates appreciation of its limitations. Respir Med. 2013;107:789–99. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Society of Automotive Engineers. Automated Driving. Levels of driving automation are defined in new SAE International Standard J3016. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://www.sae.org/binaries/content/assets/cm/content/news/press-releases/pathway-to-autonomy/automated_driving.pdf .

- 40.Kwon S, Hong J, Choi EK, Lee E, Hostallero DE, Kang WJ, et al. Deep learning approaches to detect atrial fibrillation using photoplethysmographic signals: Algorithms development study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealt. 2019;7:e12770. doi: 10.2196/12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rashidi HH, Tran NK, Betts EV, Howell LP, Green R. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in pathology: The present landscape of supervised methods? Acad Pathol. 2019;6:2374289519873088. doi: 10.1177/2374289519873088. doi: 10.1177/2374289519873088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maleki S, Zandvakili A, Gera S, Khutti SD, Gersten A, Khader SN. Differentiating noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features from classic papillary thyroid carcinoma: Analysis of cytomorphologic descriptions using a novel machine-learning approach. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:29. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_25_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajpurkar P, Irvin J, Ball RL, Zhu K, Yang B, Mehta H, et al. Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis: A retrospective comparison of the CheXNeXt algorithm to practicing radiologists. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singapore announces AI platform for cell therapy and immuno-oncology. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://www.biospectrumasia.com/news/54/15640/singapore-announces-ai-platform-for-cell-therapy-and-immuno-oncology.html .

- 45.Dai S. Doctors in Singapore now have a smart assistant backed with AI technology from China's Ping An. [Last accessed on 04 Oct 2019]. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/tech/science-research/article/3019907/doctors-singapore-now-have-smart-assistant-backed-ai .

- 46.Porter M. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review. Mar 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liew C. Medicine and artificial intelligence: A strategy for the future, employing Porter's classic framework. Singapore Med J. 2020;61:447. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2019047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]