ABSTRACT

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is an etiologically unknown systemic disease characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Additionally, it is accompanied by vasculitis of small and medium-sized blood vessels. It manifests clinically as a triad involving the lungs, upper airways, and kidneys. It is estimated that 90% of patients will exhibit upper or lower airway symptoms and around 80% develops the renal disease. In this article, we describe three case scenarios with varying presentations. GPA should be considered among the possible etiologies of cavitary pulmonary lesions with ear manifestations including hearing loss with poor response to unusual treatment.

Keywords: Cavitary lung disease, diagnostic dilemma, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, hearing loss, hemoptysis

Introduction

As a type of systemic vasculitis involving medium and small arteries, Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) affects both the upper and lower respiratory tract and often coincides with glomerulonephritis. A necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) are common hallmarks of GPA.[1] The pulmonary involvement of GPA is well described, but the lower airway involvement has received little attention, and various descriptions have been published.[2] In some cases, ear, nose, or throat involvement may be the only early manifestation of the disease. Untreated GPA patients have a median survival of 5 months, 82% die within one year, and over 90% die within two years if they are not treated promptly.[3] Here, we describe three cases of GPA with varying presentations diagnosed using a combination of various clinical, laboratory, imaging, and biopsy criteria.

Case Presentation

Case-1

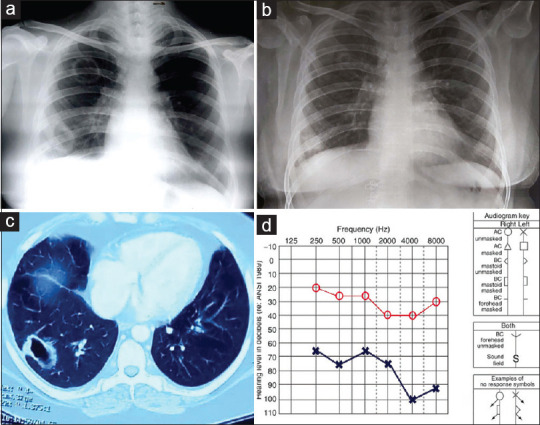

A 37-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented with hearing loss in her left ear for 5 months, cough, low-grade fever, hemoptysis, and night sweats for 1 month. Initially, she was diagnosed to have pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) on a radiological basis and was started on anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) (HRZE). She continued to worsen even after being on ATT for 4 months and was referred to us for further evaluation. On physical examination, PR was 82 beats/min, BP was 110/68 mmHg, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min without any use of accessory muscles of respiration, and no lymphadenopathy. On respiratory system examination, there were no abnormal findings. The rest of the systemic examination was normal. Routine hematologic investigations showed an ESR-40 mm/h and other routine investigations were normal. Chest radiographs demonstrated a cavity in the right upper and lower zone [Figure 1a]. Differentials considered were rheumatoid vasculitis, tuberculosis, GPA, and fungal infection. Urine microscopic examination showed microscopic hematuria (7-10 RBC/HPF). Urine and blood cultures were sterile. Sputum smear examination for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and sputum cultures (pyogenic, mycobacterial, and fungal) were negative, and a tuberculin test was nonreactive (5 × 6 mm). Ultrasonography (USG) of the whole abdomen was normal. CT scan of the thorax [Figure 1c] revealed a cavity measuring 4 × 3 cm with a few nodules in the right upper lobe and a cavity measuring 5 × 2 cm in the right lower lobe with normal surrounding lung parenchyma. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid cytology revealed mononuclear cell preponderance and was negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungus, and malignant cells. A pure tone audiogram (PTA) was done which revealed mild sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in the right ear and severe mixed hearing loss with profound loss at high frequency in the left ear [Figure 1d]. The serum perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) were negative, while the serum cytoplasmic antineutrophil antibodies (c-ANCA) were positive (76.0 IU/ml). Diagnosis of granulomatosis with polyangiitis was made based on the American College of Rheumatology- European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (ACR-EULAR) criteria. A combination of oral prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was initiated after which the patient showed significant improvement in pulmonary symptoms. Follow-up chest X-ray showed significant improvement after 2 months [Figure 1b]. Unfortunately, repeat PTA confirmed persistent unilateral hearing loss in the left ear with no significant improvement even after treatment.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray (PA view) showing cavity in right upper and lower zone (a), CT-Thorax showing thick-walled cavity in right lower lobe (c); Pure Tone audiogram (d) mild sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in right ear and severe mixed hearing loss with profound loss at high frequency in left ear, and (b) showing response to treatment

Case-2

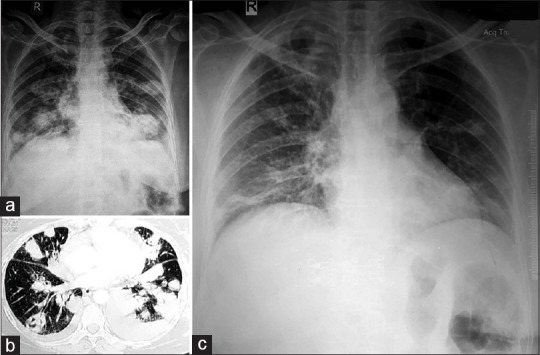

A 48-year-old non-smoker female presented with complaints of pain and reduced hearing in both ears for the last 4 months, cough with expectoration, streaky hemoptysis, and low-grade fever for the last 2 months along with anorexia and weight loss. She was clinically diagnosed to have PTB and was started on Cat-1 ATT (HRZE). As there was no symptomatic improvement, she presented to us. Chest radiograph (PA view) revealed multiple nodular lesions in both lung fields with left-sided pleural effusion [Figure 2a]. Routine blood investigations were within normal limits with raised ESR and urine microscopic examination showed microscopic hematuria (5-6 RBC/HPF). Pleural Fluid analysis revealed exudative lymphocytic effusion, with low ADA (14.6 IU/L), and was negative for malignant cells. Sputum smears for AFB and CBNAAT were negative. CT thorax revealed a large rounded mass lesion involving the apico-posterior segment of the right upper lobe, multiple nodular and cavitary lesions in bilateral lung fields, and left sided pleural effusion [Figure 2b]. Lung cryo-TBLB revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltration of the interstitium with features of vasculitis. Later, PTA revealed bilateral SNHL along with negative ANA and positive c-ANCA (63.9 IU/ml). In view of clinical-radiological findings, biopsy findings, c-ANCA positivity, and sensorineural hearing loss, a diagnosis of GPA was made. She was started on a combination of prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and co-trimoxazole along with other organ-specific therapy. She is in remission [Figure 2c] until the last follow-up with low-dose glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide.

Figure 2.

Chest Radiograph (PA view) showing multiple cavitary nodules involving bilateral mid and lower zone (a), CT-Thorax showing multiple cavitary nodules with left sided pleural effusion (b), and (c) shows resolution of cavities and pleural effusion after 3 months of treatment initiation

Case-3

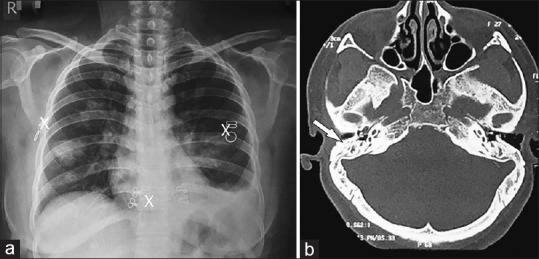

A 27-year-old, non-diabetic, non-hypertensive, euthyroid, immune-competent female presented with complaints of dry cough for 4 weeks, hemoptysis for 3 weeks, left-sided chest pain for 2 weeks, along with fatigue and loss of weight. She also complained of pain in multiple joints and difficulty hearing. She was clinically diagnosed to have PTB and was started on ATT (HRZE). With no improvement, she was referred to us. On examination, PR-122/min, BP-90/60 mmHg, RR-24/min, and was pale. There were reduced breath sounds in the left infra-scapular area on respiratory system examination. Chest radiograph showed multiple bilateral nodular shadows with left pleural effusion [Figure 3a]. Her sputum for AFB and CBNAAT were negative. No pathogenic organism was seen in the sputum gram smear and culture and sensitivity testing. CT brain revealed bilateral CSOM [Figure 3b], and CT thorax showed multiple nodular opacities with few cavitations in both lungs. Later, PTA revealed bilateral conductive hearing loss. Pleural fluid was exudative, and lymphocytic with low ADA. Her Rheumatoid factor and Anti PR3 antibody were positive (67 IU/ml). Based on the ACR-EULAR criteria, the diagnosis of GPA was made after six of the ten criteria were met and she was initiated on prednisolone and cyclophosphamide. She is advised to follow up regularly to assess the remission (clinical and radiological) and to monitor the toxicity of cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids.

Figure 3.

Chest Radiograph (PA view) showing bilateral cavitary nodules with left sided effusion (a) and CT brain (b) shows features of CSOM (White arrow denoting hypopneumatisation of the mastoid air cells)

Discussion

GPA, also known as systemic immune vasculitis is associated with ANCA. Friedrich Wegener first described the condition in 1936. Since then, it has been referred to as wegeners’s granulomatosis (WG) in the medical literature; however, its nomenclature has changed to GPA in recent years.[4,5]

According to the Johns Hopkins University Vasculitis Center, there several primary signs and symptoms associated with GPA. A majority of these cases involve (1) diseases of the ear, nose, or throat (95%); (2) persistent cold symptoms coupled with otitis media (about 90%); (3) lung lesions associated with chronic coughs (85%); (4) kidney dysfunction (75%); (5) arthritis symptoms of joints of hands, knees, ankles, and feet (70%); and (6) ocular discomfort or double vision (50%).[6] In 85% to 90% of cases, pulmonary involvement is present; manifestations include multiple nodules with or without cavitation, fleeting pneumonia, unilateral or bilateral pleural effusion, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.[7,8]

The exact cause of GPA is unknown. Several polymorphisms have been associated with PRTN3 (the gene encoding proteinase-3), HLA-DP, and SERPINA1 (a circulating inhibitor of PR3), which strongly suggest that the autoimmune response to PR3 plays a role in disease pathogenesis. A causal relationship may exist between environmental factors and the ross river virus. GPA can also be exacerbated by toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) produced by Staphylococcus aureus. Inhalation of a stimulant causes activation of neutrophils leading to the transfer of PR-3 to cell membranes and increased levels of c-ANCA, gamma globulins, and circulating immune complexes. Vasculitis results from increased cellular and humoral immune factors that also contribute to granuloma formation and tissue destruction. The sex distribution is equal, and the majority of patients are in their fifth decade, although the range of age extends to both extremes.[9]

Identifying a clinical phenotype, eliminating vasculitis mimics, and assessing the extent of the disease are essential steps in diagnosing the disease. Testing for ANCA is highly specific with indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) for c-ANCA pattern and PR3 confirmation through ELISA. The most specific findings in GPA are necrotizing vasculitis in any organ or pauci-immune glomerulonephritis on histopathology, with renal biopsy being the most sensitive and specific.[9] ACR/EULAR Classification 2022 suggests that a diagnosis of GPA is based on 3 items in clinical criteria, and 7 items in laboratory, imaging, and biopsy criteria and a score of ≥5 is required to classify the disease as GPA.[10]

Immunosuppressive medication is used as a treatment for the two main phases, induction (either new or relapsing) and maintenance of remission. For patients with organ or life-threatening disease, glucocorticoids (GC) combined with Rituximab (RTX) or cyclophosphamide (CYC) are used to induce remission, while methotrexate (MTX) and GC are used for non-severe active GPA patients. In patients with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) or raised serum creatine levels above 5.65 mg/dl (500 mmol/L), plasma exchange (PLEX) therapy may be beneficial. The most common drugs used for maintenance are azathioprine (AZA), RTX, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), MTX, or leflunomide (LEF) depending on the individualized factors such as renal and liver function, pregnancy or history of prior relapses.[9] Current recommendations are summarized in Table 1.[11]

Table 1.

Current ACR treatment recommendation

| American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2021 Guideline | |

|---|---|

| Induction | |

| Severe | High dose IV or PO GC |

| RTX >CYC | |

| IVIg if unable to receive conventional immunosuppression (due to sepsis, pregnancy etc) | |

| Non-severe | MTX + GC |

| Refractory disease | Switch to induction therapy |

| Add IVIg to induction therapy | |

| Remission | RTX with scheduled re-dosing |

| MTX or AZA >MMF or LEF | |

| Relapse | RTX >CYC |

| Already on RTX: Switch RTX to CYC | |

| Alternatively add IVIg | |

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AZA, azathioprine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; GC, glucocorticoid; IV, intravenous; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; LEF, leflunomide; MMF, mycophenolate; MTX, methotrexate; PLEX, plasma exchange; PO, oral; RTX, rituximab

Many novel therapies have been identified and are under trial. Avacopan (CCX-168; ADVOCATE, CLEAR, & CLASSIC trial) is an oral C5a inhibitor, steroid-sparing novel induction agent. Other novel therapies used in treating relapsing or refractory disease include abatacept (CTLA-4 Inhibitor; ABROGATE trial), alemtuzumab (anti-CD 52 antibodies; ALLEVIATE trial), and belimumab (anti-B-lymphocyte; BREVAS trial).[12]

Untreated GPA has a poor prognosis, with a 90% mortality rate within 2 years. Cardiovascular disease (CVD), malignancy, infection, and renal dysfunction are considered to be risk factors for premature mortality in ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). The Risk of malignancy is higher in GPA than in MPA or EGPA, largely attributed to cyclophosphamide exposure.[9]

In our series, all three patients were clinically diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and all had hearing impairment with pulmonary cavitating nodules, this should suggest an inflammatory condition like GPA and it should be placed high on the list of differentials. In many autoimmune conditions including AAV such as GPA, glucocorticoids still remains the cornerstone of treatment despite the well-recognized adverse events associated with it.

Conclusion

GPA is an uncommon disease that is associated with a significant mortality risk if diagnosing and treating it are delayed. Otological manifestations such as hearing loss and otitis media can even be the first sign of the disease. Inflammatory diseases like GPA should be considered when the condition has failed to respond to anti-microbial therapy/ATT in a TB endemic country like India.

Key learning points from this case series

-

1)

Ear disease in GPA might be present for months before pulmonary or renal manifestations and is often ignored.

-

2)

Prompt recognition and treatment are necessary to preserve the auditory function and to prevent the involvement of other organs.

-

3)

Presence of cavitary lung disease indicates a high sputum bacillary load in tuberculosis; hence, if microbiological confirmation is not proven, one should also suspect other conditions like GPA before classifying the case as clinically diagnosed TB.

Availability of data and materials

All data underlying the findings are fully available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical committee approval was required for this case report by the Department because this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals. Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in this study.

Author contribution

VV, SJ, YA, AS, DKMN, PS: Concepts; VV, SJ, YA, AS, DKMN, PS: definition of intellectual content; VV, SJ, YA, DKMN: literature research; VV, SJ, AS, PS: manuscript preparation; VV, SJ, AS, PS: manuscript editing; Manuscript review and final approval: All author’s

Consent for publication

Both patients gave their written informed consent to use their personal data for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. All authors agree to the content of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fahey JL, Leonard E, Churg J, Godman G. Wegener's granulomatosis. Am J Med. 1954;17:168–79. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis:A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97:906–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A, Armas JM, Dempster JH. Wegener's granulomatosis:Diagnostic dilemma. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:46–7. doi: 10.1258/0022215011906768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis:Lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis) Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164((Suppl 1)):7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woywodt A, Matteson EL. Wegener's granulomatosis—probing the untold past of the man behind the eponym. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1303–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghavidel A. Otitis media triggered by Wegener's granulomatosis:A case report and review of the literature. J Res Clin Med. 2015;3:261–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samara KD, Papadogiannis G, Nicholson AG, Magkanas E, Stylianou K, Siafakas N, et al. A patient presenting with bilateral lung lesions, pleural effusion, and proteinuria. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/489362. doi:10.1155/2013/489362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananthakrishnan L, Sharma N, Kanne JP. Wegener's granulomatosis in the chest:High-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:676–82. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin K, Janagan S, Wells M, Crawshaw H, McAdoo S, Robson JC. ANCA associated vasculitis subtypes:Recent insights and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:2567–82. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S284768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robson JC, Grayson PC, Ponte C, Suppiah R, Craven A, Judge A, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for rheumatology classification criteria for granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:393–9. doi: 10.1002/art.41986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SA, Langford CA, Maz M, Abril A, Gorelik M, Guyatt G, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation guideline for the management of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:1088–105. doi: 10.1002/acr.24634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RM. Update on the treatment of ANCA associated vasculitis. Presse Med. 2015;44:e241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data underlying the findings are fully available.