ABSTRACT

Context:

Growing pain (GP) is a common presentation in primary care settings.

Aims:

To find out the prevalence of GP and to observe its characteristics and associations.

Settings and Design:

General paediatric outpatient department (OPD).

Methods and Material:

Children coming to the general paediatric OPD of a tertiary centre in India between April 2019 and March 2020 for ‘chronic leg pains’ were screened with Peterson’s criteria. Patients with systemic illness were excluded. All received vitamin D and calcium supplementation. Patients with haemoglobin less than 11 gm% received additional 3 mg/kg iron supplementation. Then, patients were asked for follow-up.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi-square test.

Results:

A total of 333 children were diagnosed as GP out of the total OPD attendance of 26750. The prevalence was 1.24% and 72.7% among the children with chronic leg pain. Highest prevalence was in winter (1.74%). The mean age of the patients was 7.88 years. The mean duration of symptoms was 10.92 months. After 3 months, 267 patients could be followed up. Seventy-two out of 107 (67.3%) children, who received iron became symptom-free. Only 43 (28.8%) patients became symptom-free out of 160, who received only calcium and vitamin D3 and did not receive iron. The difference was highly significant statistically (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

The prevalence of GP in the OPD was 1.24% and 72.7% among the children with chronic leg pain. Iron supplementation along with vitamin D3 and calcium was associated with faster resolution of the symptoms.

Keywords: Calcium, child, iron, leg pains, night pain, vitamin D

Introduction

Growing pains (GPs) in children are characterised by intermittent poorly localised nocturnal pains in children, usually affecting the legs without any obvious cause. This condition is fairly common presentation in primary care set-ups and the parents often seek consultation of the primary care physicians or family doctors. As per Nelson’s text book of paediatrics, GP affects about 10–20% of children.[1]

Since GP was described by Marcel Duchamp as Maladies de la Croissance (pains of growth) in the nineteenth century,[2] the term ‘Growing Pain’ was used vaguely for any leg pain in children until Peterson in 1986 gave a clear definition for diagnosis of the GP.[3]

During the first half of the twentieth century, GP was considered to be a subacute form of rheumatic fever and it was feared that these children might develop carditis. However, careful follow-up of GP cases by Hawksley (1939) did not reveal any evidence of carditis even after four years. Apley in 1951 gave more emphasis to psychological factors towards the causation of GP.[4,5]

Certainly, growth is not the cause of the pain. The exact mechanism of the pain is still not understood; many theories have been put forward such as psychological, mechanical, overuse and low pain threshold to explain the nature of the pain. Currently, GP is considered to be a benign condition with uncertain aetiology. Most children eventually outgrow this condition and GP does not lead to any further serious disorders later on. Nevertheless, they can produce considerable anxiety in the parents and the physician. Proper knowledge and awareness about GP would certainly help to reduce that.[2,3]

Though common, this condition hardly gets any attention during undergraduate medical study or paediatrics post-graduation tenure. Thus, general practitioners, primary care doctors and even paediatricians have very low level of awareness and a vague idea about this common problem.

Hence, this study was undertaken to find out the prevalence of GP in the general paediatric outpatient department (OPD) and to study its characteristics and associations.

Subjects and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee vide memo no. MMC/IEC 2019/21 dated 28/03/2019, and the study was conducted as per the standard ethical practices of the institution. Informed consent from the parents or guardians was obtained before including them in the study.

Study design

Cross-sectional, descriptive and observational.

Setting

Paediatrics OPD of a rural medical college.

Period of the study

April 2019 to March 2020.

Participants

Children coming to the Paediatric OPD.

In the paediatric OPD, where this study was conducted, there were four resident doctors (two junior and two senior) and one consultant paediatrician (professor/associate professor/assistant professor). A workshop on GP and the study methodology was conducted before taking of this study, where the above doctors participated. All the cases of chronic leg pains (agreed to be more than one month) were first attended by the resident doctors, and then, they were seen by the consultants.

Diagnosis of GP was done with the help of the inclusion and exclusion criteria [Box 1] described by Peterson.[2,3] Inclusion criteria were intermittent poorly localised leg pains, which occurred in the evening or night, with normal physical examination. Exclusion criteria were continuous/persistent/increasing/localised pain, joint involvement, oedema/tenderness/restriction of movements/limping on physical examination. Laboratory investigations are usually not required for the diagnosis.[2,6] Informed consent from the parents after due explanation was taken before including them in the study.

Box 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Intermittent pain with pain free intervals, usually one or two in a week lasting up to 2 h | Persistent or increasing pain |

| usually in evening/night | Day time pain or pain lasting throughout the day |

| Both legs are involved | Unilateral pain |

| Calf muscles usually, sometimes Back of knee or anterior thigh | Joint pain |

| Normal Physical Examination | Swelling, Erythema, Tenderness History of injury, limping |

Though diagnosis of GP was done entirely on a clinical basis, routine blood tests such as complete blood count and C-reactive protein (CRP) were done to exclude any associated underlying inflammatory process. Children suffering from systemic illnesses or any other chronic diseases were excluded from the study. When the haemoglobin levels were less than 11 gm%, further investigations for sickling test, peripheral blood smear and haemoglobin electrophoresis were advised. Patients found to be with haemolytic anaemia were excluded. The sickle cell/thalassemia traits were also excluded.

Variables, data sources and measurements

The age was recorded in years rounded off to the nearest complete year. Rural or urban residence was determined from the address. Weight was recorded with a help of a digital weighing scale in kilogram and its fractions. Height was recorded with the stadiometer in centimetres. Body mass index (BMI) was determined for children above 5 years with IAP growth charts and classified as underweight, normal or overweight as per the chart.[7] Children less than 5 years were classified as per the WHO weight for age chart.[8] The duration of the symptoms was recorded in months. Socio-economic class (SC) was determined using the modified Kuppuswami scale. For the sake of simplicity SC, I was taken as upper, SC II and III were as middle, and SC IV and V were taken as lower.[9] The emotional well-being of the child was assessed using the Bengali version of the Spence Children Anxiety Scale.[10] A score above 60 was taken as an indicator of anxiety in the child. During follow-up, ‘improvement’ was defined as the absence of pain at least for the last month.

Management and follow-up of cases: ‘All children with GP’ were given a single-dose oral supplementation of 60,000 IU of vitamin D3 along with a daily dosage of 50 mg/kg of calcium and 600 IU of vitamin D3 preparations for 3 months.[11] When the haemoglobin level was less than 11 gm%, iron was supplemented orally at a dose of 3 mg per day for three months.[12,13] The parents were asked to come for follow-up every month for at least 3 months. Patients who could not come physically were followed up telephonically.

Bias: All the cases were diagnosed strictly based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The parents of each diagnosed GP cases were questioned with standard pre-structured printed Performa. The resident doctors involved with data collection were trained to use the Peterson’s diagnostic criteria of GP and the Spence Children Anxiety Scale.

Study size: Sample size (n) was calculated using the formula n = Z2P (1 − P)/d2, where Z is 1.96 for 95% confidence interval, P is expected prevalence, and d is tolerable error.[14] Assuming the prevalence of GP is around 10–20% in the population, we expected 5% would seek consultation. Taking P as 5% and d as P/5, the estimated sample size was 4475. However, it was decided to carry out the study for one calendar year, where we expected around 20,000 to 30,000 attendance as per previous records, which would bring down the error substantially and would cover all the seasons to observe any seasonal variation.

Statistical methods: The data collected utilizing the pre-printed Performa were transferred to Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Descriptive analysis was done for socio-demographic factors. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were calculated to determine the association between growing pain and various factors. A Chi-square test was used and a P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Total number of OPD attendance was 26,750 during the study period from April 2019 to March 2020. There were 408 cases of chronic leg pains, out of which 333 children were diagnosed as GP by Peterson’s criteria. Thus, the prevalence of GP was 1.24% among children visiting OPD and 72.7% among children with chronic leg pain.

Table 1 enlists other causes of chronic leg pains. There were 16 cases where no diagnosis could be ascertained. Out of these, nine cases had abnormal physical and laboratory findings and they were referred to the higher centre or other departments. Rest seven cases had normal physical and laboratory examination results and were classified as an atypical presentation of GP as per Peterson’s criteria as follows.

Table 1.

Causes of chronic leg pains in children

| Diagnosis | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Growing pains | 333 |

| Sickle cell trait | 73 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 14 |

| Sports injury | 11 |

| Transient synovitis | 6 |

| Restless leg syndrome | 3 |

| Malignancy | 2 |

| Atypical presentation of GP | 7 |

| No diagnosis | 9 |

| Total | 458 |

Site of pain: Involving one leg only, as opposed to bilateral involvement

Time of pain: Morning pains or sometimes pain persisting throughout the day as opposed to night pains.

‘Mean age of the patients’ was 7.88 years (SD 2.01, range 3–14 years). ‘Mean duration of symptoms’ was 10.92 months (SD 5.46, range 1–36 months).

Table 2 describes various associations of growing pains.

Table 2.

Associations of growing pains

| Factors associated with GP | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 172 | 51.65 |

| Urban residence | 242 | 72.67 |

| Underweight | 63 | 19.52% |

| Summer | 125 | 37.5% |

| Rainy | 101 | 30.3% |

| Winter | 107 | 32.1% |

| Anxiety in child | 68 | 20.4% |

| High SC | 23 | 6.9% |

| Middle SC | 225 | 67.6% |

| Lower SC | 85 | 25.5% |

| Anaemia (Hb% <11) | 115 | 34.5% |

There were 172 (51.65%) males and 161 (48.35%) females in the study. A total of 242 (72.67%) cases had an urban residence, while 91 (27.33%) cases came from rural background. Sixty-three (19.52%) cases were underweight and 17 (7.51%) cases were overweight. It was found that though the OPD attendance was highest (12,188) during the monsoons (July to October), only 101 (30.3%) cases of GP (0.83%) were diagnosed. However, 125 out of 333 cases of GP (37.5%) were detected out of 8423 (prevalence 1.48%) during the summer months (April, May, June and March). Winter (November to February) recorded 107 (32.1%) cases out of 6139 or prevalence of 1.74%.

Only 68 (20.4%) cases had anxiety scores of more than 60 using the Spence Children Anxiety Scale. The highest proportions (67.6%) of cases were from middle socio-economic class (SC II and III as per the modified Kuppuswami scale).

Table 3 depicts follow-up of cases of growing pains.

Table 3.

Follow-up of cases of growing pains

| Follow-up visits | Hb* <11 gm/dL (received iron, calcium and vitamin D) | Cases received only calcium and vitamin D | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st visit | 115 | 218 | 333 | |

| Follow-up after 1 month | 115 | 190 | 305 | |

| Improvement after 1 month | 28 (24.35%) | 13 (6.84%) | 41 | <0.0001 |

| No improvement after 1 month | 87 | 177 | 264 | |

| Follow-up after 3 months | 107 | 160 | 267 | |

| Improvement after 3 months | 72 (67.3%) | 43 (28.8%) | 115 | <0.0001 |

| No improvement after 3 months | 35 | 117 | 152 |

*Hb% less than 11 is considered anemia

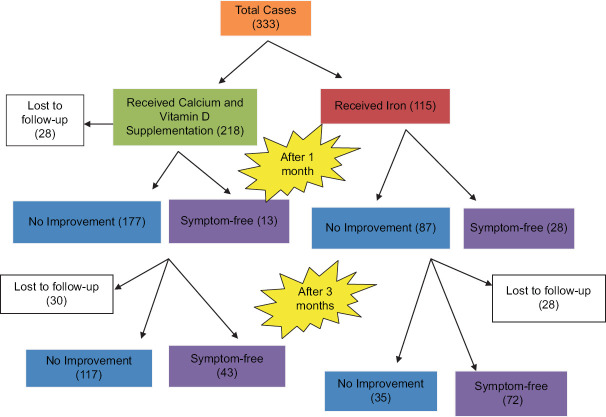

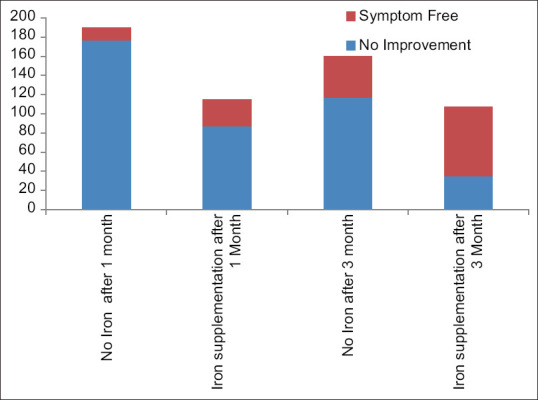

It was found that 115 (34.5%) cases had haemoglobins less than 11 gm%. These 115 patients received iron supplementation at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day for 3 months in addition to vitamin D and calcium. Total of 305 patients could be followed up after 1 month. Twenty-eight (77.2%) patients out of 115 who received iron group and 13 (24.35%) out of 190 in the non-iron group were symptom-free after 1 month. Thirteen (6.84%) out of 190 in the non-iron group were also symptom-free. The above two groups were compared using the Chi-square test and the P value was <0.0001 (95% confidence interval 9.2400% to 26.5447%).

After 3 months, 267 patients could be followed up. Seventy-two out of 107 (67.3%) children who received iron became symptom-free. Only 43 (28.8%) patients became symptom-free out of 160, who received only calcium and vitamin D3 and did not receive iron. The difference was highly significant statistically (P < 0.0001 and 95% confidence interval 26.5430% to 48.8997%).

Figure 1 Follow-up of cases of growing pains.

Figure 1.

Follow-up of cases of growing pains

Figure 2 Significant improvements of symptoms after iron supplementation.

Figure 2.

Significant improvements of symptoms after iron supplementation

Discussion

The prevalence of GP in this study was 1.24% during the year 2019–20.

The prevalence of GP varies widely from 2.6 to 49.4% in the reported literature. This is due to the disparity in sample sizes, age ranges and unspecified populations.[15] Kaspiris et al.[16] reported the prevalence to be 24.5% in children of 4–12 years in a hospital-based retrospective study using questionnaires for parents. Evans et al.[15] found the prevalence among children of 4–6 years as high as 36.9%, in a well-designed population-based study.

Abu-Arafeh and Russel studied school children aged 5–15 years in Aberdeen, UK, where the prevalence of GP was 2.6%.[17] Naish and Apley (1951) in their extensive paper on GP described the prevalence to be 4.2% among school children aged 8–12 years.[5] Vishwanathan and Khubchandani[18] from India examined 433 school children of age 3–9 years and reported the prevalence to be 28.1%. Haque et al.[19] from Bangladesh found a prevalence of 19.3% among school children aged 6–12 years. The high prevalence of GP in some of the above studies was not reflected in our study. It is probably because our study was based in a tertiary care hospital and most parents perhaps visit primary care only. It is also possible that many mild cases do not seek any medical help. Kaspiris et al.[16] reported that only one in five parents visited a doctor.

GP is the most common cause of chronic leg pains in children. In our study, 72.7% of cases were diagnosed as GP among children with chronic leg pain. Similar to our study, De Piano et al.[20] found that 87% of cases of chronic leg pains were due to GP.

The mean age of the patients was 7.88 (SD2.01) years. The finding was in agreement with other studies, where the age of the study population was not pre-determined. Kaspiris et al.[16] reported the mean age to be 8.6 (SD 2.5) years. Haque et al.[19] also reported the peak age of incidence to be 7 and 8 years of age. De Piano et al.[20] from Brazil found the mean age to be 9.2 ± 4 years. Pavone et al.[21] found the mean age to be 8 years too.

The mean duration of symptoms in this study was 10.9 (SD 5.46) months, and the maximum duration was up 48 months. Similar observations were also noted by Haque et al.[19]

In this study, males outnumbered females (51.35% vs 48.65%). Similar findings were reported by many authors.[17,19,22] It seems boys may be more prone to suffer from GP than girls.

In this study, urban children were more (72.67%) than rural children (27.33%). Most of the earlier studies on GP were conducted in urban schools.[5,17,19]

The study found 19.52% of GP cases to be underweight and 7.51% of them to be overweight. Haque et al.[19] found 15.4% of cases to be overweight.[19] Kaspiris et al. in their analysis did not find any correlation between GP and BMI.[16] De Piano et al.[20] reported that the mean BMI of the GP cases was not significantly different than other normal children.

The prevalence was highest during the winter and lowest during the rainy season. Park et al.[22] had also reported the highest prevalence during the winter. This may be related to low vitamin D levels in winter.

Naish and Apley had postulated emotional disturbances as the major cause of GP.[5] But in this study, only 20.4% of cases had anxiety scores of more than 60 while using the Spence Children Anxiety Scale.

However, the GP cases came from all socio-economic classes most (67.6%) patients belonged to the middle socio-economic class (SC II and III as per the modified Kuppuswami scale).

Recently, many authors such as Sharma et al. (2018), Vehapoglu (2015) et al., Morandi et al. (2015) and Insaf (2017) have demonstrated that supplementation of vitamin D3 in children with GP resulted in improvement.[11,23,24,25] But we found significantly greater proportion of children improved when they received iron along with calcium and vitamin D3.

We did not find any study where iron supplementations improved the symptoms of GP. Iron supplementation was found to improve restless leg syndrome (RLS).[26] Sometimes RLS and GP might represent a different spectrum of the same underlying problem,[27] which might explain the significant improvement of symptoms after iron supplementation in this study.

There are limitations in the above finding in the study that it did not separate cases of vitamin D supplementation from cases with iron supplementation. Also laboratory studies to confirm vitamin D or iron deficiency could not be done. It is known that there might be iron deficiency despite normal levels of haemoglobin as anaemia is a late presentation.[28,29] The cases, which had haemoglobin levels more than 11 gm% in this study, did not receive any iron supplementation. We may suspect that the cases, which did not improve with calcium and vitamin D, might be having iron deficiency despite normal haemoglobin levels.

Conclusions

The prevalence of GP in the OPD was 1.24% and 72.7% among children with chronic leg pain. Iron supplementation along with vitamin D3 and calcium was associated with faster resolution of the symptoms. Further studies may be done to find out the role of iron in GP.

What is already known: GP is a common benign and self-limiting condition in children. Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to GP.

What this study adds: Along with vitamin D and calcium supplementation, iron supplementation may be beneficial in the management of GP.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Anthony K, Schanberg L, Anthony K, Schanberg L. Growing pains. In: Kliegman R, Blum R, Geme J III, Tasker R, Shah S, Wilson K, et al., editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Elsevier Inc; 2020. pp. 1329–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohanta MP. Growing Pains:Practitioners'Dilemma. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:379–83. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen H. Growing pains. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33:1365–72. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawksley JC. The nature of growing pains and their relation to rheumatism in children and adolescents. BMJ. 1939;1:155–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4073.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naish JM, Apley J. 'Growing pains':A clinical study of non-arthritic limb pains in children. Arch Dis Child. 1951;26:134–40. doi: 10.1136/adc.26.126.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asadi-Pooya AA, Bordbar MR. Are laboratory tests necessary in making the diagnosis of limb pains typical for growing pains in children? Pediatr Int. 2007;49:833–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indian Academy of Pediatrics Growth Charts Committee. Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal KK, Tamboli S, Banerjee M, et al. Revised IAP growth charts for height, weight and body mass index for 5- to 18-year-old Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0566-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO, Child Growth standards, weight for age. [[Last accessed on 2019 Mar 18]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/weight-for-age .

- 9.Singh T, Sharma S, Nagesh S. Socio-economic status scales updated for 2017. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:3264–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spence SH. Spence Children Anxiety Scale. [[Last accessed on 2019 Mar 22]]. Available from https://www.scaswebsite.com/

- 11.Sharma S S, Verma S, Sachdeva N, Bharti B, Sankhyan N. Association between the occurrence of growing pains and vitamin-D deficiency in Indian children aged 3-12 years. Sri Lanka J Child Health. 2018;47:306–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharadwa K, Mishra S, Tiwari S, Yadav B, Deshmukh U, Elizabeth KE, et al. Prevention of micronutrient deficiencies in young children:Consensus statement from infant and young child feeding chapter of Indian academy. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:577–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandal P, Mukherjee S. Management of Iron deficiency anemia—a tale of 50 years. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:47–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-017-0995-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6:14–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans AM, Scutter SD. Prevalence of “growing pains”in young children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:255–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaspiris A, Zafiropoulou C. Growing pains in children:Epidemiological analysis in a Mediterranean population. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu-Arafeh I, Russel G. Recurrent limb pain in school children. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:336–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viswanathan V, Khubchandani RP. Joint hypermobility and growing pains in school children. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:962–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haque M, Laila K, Islam MM, Islam MI, Talukder MK, Rahman SA. Assessment of growing pain and its risk factors in school children. Ame J Clin Exper Medi. 2016;4:151–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Piano LPA, Golmia RP, Golmia APF, Sallum AME, Nukumizu LA, Castro DG, et al. Diagnosis of growing pains in a Brazilian pediatric population:A prospective investigation. Einstein. 2010;8:430–2. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082010AO1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavone V, Lionetti E, Gargano V, Evola F, Costarella L, Sessa G. Growing pains:A study of 30 cases and a review of literature. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:606–9. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318220ba5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park MJ, Lee J, Lee JK, Joo SY. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in Korean children presenting with nonspecific lower-extremity pain. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56:1384–8. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.5.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vehapoglu A, Turel O, Turkmen S, Inal BB, Aksoy T, Ozgurhan G, et al. Are growing pains related to vitamin D deficiency?Efficacy of vitamin D therapy for resolution of symptoms. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:332–8. doi: 10.1159/000431035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morandi G, Maines E, Piona C, Monti E, Sandri M, Gaudino R, et al. Significant association among growing pains, vitamin D supplementation, and bone mineral status:Results from a pilot cohort study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2015;33:201–6. doi: 10.1007/s00774-014-0579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Insaf AI. Growing pains in children and vitamin D deficiency, the impact of vit D treatment for resolution of symptoms. J Hea Med Nurs. 2017;39:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dosman C, Witmans M, Zwaigenbaum L. Iron's role in paediatric restless legs syndrome—A review. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:193–7. doi: 10.1093/pch/17.4.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champion GD, Bui M, Sarraf S, Donnelly TJ, Bott AN, Goh S, et al. Improved definition of growing pains:A common familial primary pain disorder of early childhood. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2022;4:78–86. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Naseem A, Sallam A, Choudhury S, Thachil J. Iron deficiency without anaemia:a diagnosis that matters. Clin Med (Lond) 2021;21:107–13. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balendran S, Forsyth C. Non-anaemic iron deficiency. Aust Prescr. 2021;44:193–6. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2021.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]