ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has seen multiple surges globally since its emergence in 2019. The second wave of the pandemic was generally more aggressive than the first, with more cases and deaths. This study compares the epidemiological features of the first and second COVID-19 waves in Kozhikode district of Kerala and identifies the factors associated with this change.

Methods:

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted in Kozhikode district. A total of 132,089 cases from each wave were selected for the study using a consecutive sampling method. Data were collected from the District COVID-19 line list using a semistructured proforma and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) ver. 18.

Results:

The second wave had a higher proportion of symptomatic cases (17.3%; 20.1%), cases with severe symptoms (0.3%; 0.6%), intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (11.2%; 17.9%), and case fatality rate (0.69%; 0.72%). Significant difference was noted in the age, gender, locality, source of infection, comorbidity profile, symptom, and the pattern of admission in various healthcare settings between the first and second wave. Among the deceased, gender, duration between onset of symptoms and death, comorbidity status, and cause of death were significantly different in both waves.

Conclusion:

The presence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta variant, as well as changes in human behavior and threat perception as the pandemic progressed, resulted in significant differences in various epidemiological features of the pandemic in both waves, indicating the need for continued vigilance during each COVID-19 wave.

Keywords: Comparative study, COVID-19, cross-sectional study, epidemiological features, pandemic waves

Introduction

Ever since the Chinese officials provided information to the World Health Organization (WHO) on the cluster of cases of “viral pneumonia of unknown cause” identified in Wuhan on January 3, 2020,[1] the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread to almost all parts of the globe, affecting more than 449 million people and killing nearly 6 million.[2]

The first confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection reported in India was on January 30, 2020 from Kerala.[3] Since then Kerala, similar to other parts of the world, has experienced two surges in active cases and newly detected cases, what we now call the first and the second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.[4,5] The second wave of the pandemic was generally more aggressive, with higher cases and deaths compared with the first. There were differences in the age group infected, their symptoms, and comorbidities, as well as mortality patterns.[6] These were attributed to local mutations leading to newer virus strains, lack of social distancing, and hand hygiene practices by the public as well as relaxation of enforcement measures by the administration.[7,8,9]

There are still numerous questions regarding the epidemiology of the coronavirus illness and our knowledge of it is still developing. Due to the lack of a sufficient number of published research on the subject from south India, the similarities and differences between the characteristics of the two waves in this part of the world remain largely unknown. To plan for the future surge in cases, we must first understand the epidemiological similarities and differences of the previous COVID-19 surges. This study compares the epidemiological features of the first and second COVID-19 waves in Kozhikode district of Kerala and identifies the factors associated with this change.

Materials and Methods

Comparative cross-sectional study, in study design

Research Approval number C2/7421/2021 Dated 28/06/2021.

Study period and setting

The present study was conducted in Kozhikode district over a period of 2 weeks from June 30, 2021 to July 15, 2021.

Sample size

Minimum sample size was estimated as 83,958 in each wave[10] using the formula (Zα + Zβ)2 × 2pq/d2.

Inclusion criteria

The first wave in the current research was defined as the interval between the lowest corresponding values in the rising and declining trend of a weekly average of Test Positivity Rate (TPR; September 07, 2021 to March 14, 2021). The second wave was defined as the time from March 15, 2021 (following the end of the first wave) until June 20, 2021 (Lowest Week average TPR after the beginning of the second wave).

A total of 132,089 cases from each wave were selected for the study using a consecutive sampling method.

Data collection

After getting approval from the District Research Committee, data were obtained from the District COVID-19 line list and database using a semistructured proforma. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables as proportions. Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-18) software package. Chi-square and logistic regression tests were used for data analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

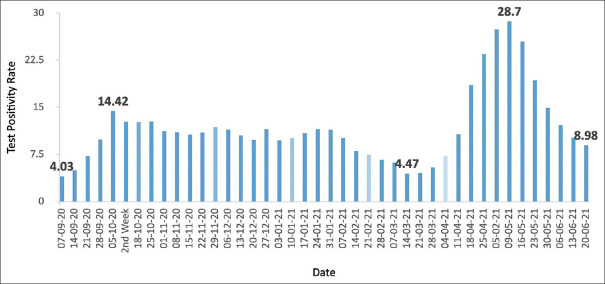

Figure 1 illustrates the trend of the weekly average of COVID-19 TPR in the present study. The first wave showed a 258% increase in test positivity rate within a period of 4 weeks. It had a prolonged decline phase lasting 23 weeks with several undulations of minor crests and troughs. The peak of the second wave had a 542% increase in TPR compared with the end of the first wave, and the growth phase lasted 8 weeks. It was followed by a rapid decline phase lasting 6 weeks.

Figure 1.

Trend of week average of test positivity rate

Demographic features and comorbidity profile

A total of 132,089 cases each from the first and second waves were included in the study. The mean age was 38.95 ± 18.891 years. Majority of the cases were epidemiologically linked to one of their family or household members. Diabetes mellitus was the most prevalent comorbidity, closely followed by hypertension. Table 1 compares the demographic features and comorbidity profile of COVID-19 patients in the first and second waves.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic features and comorbidity profiles between the first and second waves of COVID-19

| Characteristics | First Wave (n=132,089) | Second Wave (n=132,089) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s characteristics | |||

| Age* | 39.0±19.04 years | 38.8±18.7 years | 0.025 |

| Male | 75,078 (56.8%) | 70,921 (53.7%) | 0.000 |

| Female | 57,007 (43.2%) | 61,157 (46.3%) | |

| Urban locality | 60,799 (46.0%) | 55,649 (42.1%) | 0.000 |

| Rural locality | 71,290 (54.0%) | 76,440 (57.9%) | |

| Source of Infection | |||

| Family or workplace contact | 7840 (58.9%) | 53,423 (40.4%) | 0.000 |

| Public place contact | 10,244 (7.8%) | 8898 (6.7%) | |

| Other states and foreign contact | 531 (0.4%) | 326 (0.2%) | |

| Unknown Source | 36,781 (27.8%) | 61,254 (46.4%) | |

| Others | 6693 (5.1%) | 8188 (6.2%) | |

| Comorbidity Profile | |||

| Comorbidities present | 2787 (2.1%) | 724 (0.5%) | 0.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1360 (1%) | 391 (0.3%) | 0.000 |

| Systemic hypertension | 1226 (0.9%) | 328 (0.2%) | 0.000 |

| Coronary artery disease | 586 (0.4%) | 154 (0.1%) | 0.000 |

| Chronic lung disease | 207 (0.2%) | 42 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 380 (0.3%) | 67 (0.1%) | 0.000 |

| Chronic liver disease | 46 (0.0%) | 16 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 15 (0.0%) | 06 (0.0%) | 0.050 |

| Malignancy | 144 (0.1%) | 34 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

*Means±SD

Symptom profile

Majority of the study population were asymptomatic. During the second wave, there was an increase in the proportion of symptomatic individuals as well as those with severe symptoms [Table 2]. The most common symptoms were fever and cough, both of which affected a larger proportion of cases during the second wave. Other symptoms that increased significantly during the second wave were sore throat, severe fatigue, breathing difficulty, and body ache.

Table 2.

Comparison of the symptom profiles of COVID-19 patients in the first and second waves

| Characteristics | First Wave (n=132,089) | Second Wave (n=132,089) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom category during testing | |||

| Asymptomatic | 109,260 (82.7%) | 105,572 (79.9%) | 0.000 |

| Symptomatic | 22,829 (17.3%) | 26,517 (20.1%) | |

| Category A | 16,731 (12.7%) | 9325 (7.1%) | 0.000 |

| Category B | 5669 (4.3%) | 16,356 (12.4%) | |

| Category C | 429 (0.3%) | 836 (0.6%) | |

| Major Symptoms | |||

| Fever | 1973 (1.5%) | 15,257 (11.6%) | 0.000 |

| Cough | 815 (0.6%) | 5687 (4.3%) | 0.000 |

| Sore Throat | 567 (0.4%) | 1231 (0.9%) | 0.000 |

| Severe Fatigue | 41 (0.0%) | 1161 (0.9%) | 0.000 |

| Anosmia at presentation | 7 (0.0%) | 374 (0.3%) | 0.000 |

| Breathing difficulty | 375 (0.3%) | 606 (0.5%) | 0.000 |

| Chest pain | 38 (0.0%) | 159 (0.1%) | 0.000 |

| Hemoptysis | 37 (0.0%) | 107 (0.1%) | 0.000 |

| Diarrhea | 46 (0.0%) | 153 (0.1%) | 0.000 |

| Body Ache | 349 (0.3%) | 3011 (2.3%) | 0.000 |

| Nasal discharge | 131 (0.1%) | 764 (0.6%) | 0.000 |

| Vomiting | 157 (0.1%) | 504 (0.4%) | 0.000 |

| Abdominal Pain | 59 (0.0%) | 223 (0.2%) | 0.000 |

Hospital admission details

The percentage of cases that required hospitalization was higher in the first wave, whereas the second wave had a significantly high number of hospitalized patients who required ICU care. Table 3 compares hospital admission information from the first and second waves.

Table 3.

Comparison of hospital admission details and profiles of persons who died of COVID-19 during the first and second wave

| Details of Hospitalization | First Wave (n=21,216) | Second Wave (n=10,806) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government hospital | 9662 (45.54%) | 3290 (30.4%) | 0.000 |

| Private hospital | 11,554 (54.5%) | 7516 (69.6%) | 0.000 |

| Duration of hospitalization* | 7.03±4.80 days | 5.81±4.00 days | 0.000 |

| Ward | 18,836 (88.8%) | 8871 (82.1%) | 0.000 |

| ICU | 2380 (11.2%) | 1935 (17.9%) | 0.000 |

|

| |||

| Details of COVID-19 death | First Wave (n=914) | Second Wave (n=957) | P |

|

| |||

| Case Fatality Rate | 0.69% | 0.72% | |

| Age* | 67.64±12.98 years | 68.28±13.51 years | 0.298 |

| Male | 644 (70.5%) | 604 (63.1%) | 0.001 |

| Female | 270 (29.5%) | 353 (36.9%) | 0.001 |

| Interval between onset of symptoms and death* | 7.61±7.28 days | 8.99±6.45 days | 0.000 |

| Comorbidity Status | |||

| Single comorbidity | 124 (13.6%) | 194 (20.3%) | 0.000 |

| Multiple comorbidities | 721 (78.9%) | 616 (64.4%) | 0.000 |

| No comorbidity | 69 (7.5%) | 147 (15.4%) | 0.000 |

| Cause of death | |||

| COVID-19 pneumonia | 623 (68.2%) | 789 (82.4%) | 0.000 |

| ARDS | 112 (12.3%) | 197 (20.6%) | 0.000 |

| Sepsis | 87 (9.5%) | 65 (6.8%) | 0.031 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 156 (17.1%) | 70 (7.3%) | 0.000 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 19 (2.1%) | 11 (1.1%) | 0.110 |

*Means±SD

Mortality details

The overall case fatality rate (CFR) was 0.69%. Majority of the cases had multiple comorbidities. COVID-19 pneumonia remains the most common cause of death following COVID-19 infection. Table 3 compares the profiles of COVID-19 deaths throughout the first and second waves.

Discussion

Following initial isolated cases, the first surge in COVID-19 infection in Kozhikode began in early September, peaked in October, and slowly declined.

Demographic features

In our study, the mean age of the infected person was 39.0 ± 19.04 years during the first wave and 38.8 ± 18.7 years during the second wave and males were more affected in both the waves. Iftimie et al.[6] had reported that the population affected in the second wave was significantly younger than the first wave (58 ± 26 years vs. 67 ± 18 years; P = 0.001). The median age of infected persons was 55 to 65 years, with males predominantly affected due to the high concentration of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in them.[11] Arani et al.[12] reported a mean age of 54.6 ± 17.2 and the majority of cases belonged to male gender (53.7%).

In both the waves, a higher proportion of cases were from the rural locality, which was statistically significant. Different studies have reported different predominance of cases in urban and rural localities. A study from South Carolina reported significant differences in cases and deaths between urban and rural areas.[13] Another study reported the mean prevalence of COVID-19 in rural areas as 3.6 per 100,000 population compared with 10.1 per 100,000 population in the urban areas.[14] Our study reflects the proportionate distribution of population in rural and urban settings in the district.[15]

Majority of the cases were infected from close contact from either family or the workplace and this difference in proportions among the source of infection was statistically significant in the first and second waves. In Madrid, Spain, 17% of cases reported positive household contacts.[16] Another study from Switzerland found that household members of a COVID-19 patient were three times more likely to become infected than close contacts outside the home. This emphasizes the need of sending out clear instructions about preventative steps that may be taken at home.[17]

Comorbidity profile

Jalali et al.[18] noted that the most common comorbidities among COVID-19 cases were diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, chronic renal disorders, malignancies, and asthma and all of these were more prevalent during the second wave. Hypertension (58.3%), diabetes (29.8%), and heart disease (26.2%) were reported as the most prevalent comorbidities in another study.[19] Patients in the second COVID-19 wave had a significantly higher body mass index (BMI), asthma, and chronic kidney disease compared with the first wave.[20] Contrary to the above studies, we noted that the presence of comorbidities was higher among cases during the first wave and diabetes was the most common comorbidity during both the waves followed by hypertension.

Symptom profile

Majority of the cases were asymptomatic during both the waves, with the proportion of symptomatic cases increasing during the second wave, which was statistically significant also. Fever, cough, and sore throat were the predominant symptoms during the first wave while it was fever, cough, and body ache during the second wave. There was also a significant increase in the severity of illness during the second wave compared with the first. This was also contrary to several studies. In a study from Regensburg, the proportion of asymptomatic cases were found to be large during the second wave compared with the first. The comparison of symptoms reveals that the most prevalent COVID-19 symptoms reported in the first phase were cough (42%), fever (38%), and overall feeling of illness (22%), which were seen less often in the second wave (cough 14%, fever 17%, and overall feeling of illness 14%).[21] Htun et al.[19] reported that, in all 81.5% of patients were symptomatic, with fever (54.1%), loss of smell (50.3%), and cough (30.9%) being the most prevalent presenting symptoms for COVID-19. Another study reported, 35.5% of patients were having severe/critical illness during the first wave while it was 60.7% in the second wave.[22]

Hospital admission and mortality details

The duration of hospitalization was shorter during the second wave, although the proportion of patients admitted to ICU increased. The case fatality rate was greater in the second wave. There was no significant difference in the mean age of the deceased between the first and second waves. In both waves, comorbidity status was a significant determinant of COVID-19 mortality; the proportions of single, multiple, and no-comorbidity differed significantly. In other studies, the second wave, hospitalization was also significantly shorter (14 ± 19 vs. 22 ± 25 days; P = 0.001); the first wave resulted in 49 deaths while the second wave resulted in 35 deaths, lowering the case fatality rate from 24.0% to 13.2%. Patients who died in the second wave were older than those who died in the first (83 ± 10 vs. 78 ± 13 years; P = 0.042). In the first wave, logistic regression analyses revealed the importance of age, fever, dyspnea, acute respiratory distress syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cancer as the important predictors of mortality, and in the second wave, age, gender, smoking habit, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and chronic neurological diseases.[6] The second wave was associated with a greater prevalence of COVID-19, a faster increase in hospital admissions, and an increase in in-hospital mortality in South Africa. These were attributed to older people getting admitted to hospitals during the second wave, to increased healthcare pressures, and to the new Beta variant of COVID-19.[23]

Significant difference was noted in the age, gender, locality, source of infection, comorbidity profile, and symptom status between the first and second wave of COVID-19 infection. The pattern of admission in various healthcare settings also showed statistically significant differences. Analysis of mortality surveillance showed gender, duration between onset of symptoms and death, comorbidity status, and cause of death as statistically different in both waves.

The relaxation of enforcement measures, declining threat perception among public, which led to reluctance in social distancing practices as well as the emergence of newer more virulent strains of SARS-CoV-2 virus during the second wave,[24] may be responsible for this difference. The hike in the proportion of cases requiring ICU admissions, the reduced inpatient duration, and the increased case fatality rate may be attributed to the widespread presence of the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 virus, a variant of concern during the second surge.[25]

To conclude, several epidemiological parameters showed statistically significant differences between the second wave of the COVID-19 outbreak and the first. These findings may help us better understand how pandemics evolve and they also highlight the need for an established system incorporating whole genome sequencing for early detection of mutant variants of COVID-19 virus.

Author contributions

All three authors were involved in substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jayasree Vasudevan (District Medical Officer Kozhikode), Dr. Peeyush M Nambudiripad (District Surveillance Officer Kozhikode), and the management team at the District COVID Cell in Kozhikode for their tremendous support towards this research.

References

- 1.Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 response. [[Last accessed on 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline .

- 2.COVID-19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. [[Last accessed on 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html .

- 3.Andrews MA, Areekal B, Rajesh KR, Krishnan J, Suryakala R, Krishnan B, et al. First confirmed case of COVID-19 infection in India:A case report. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:490–2. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2131_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, Kebede Y, Tshangela A, Moussif M, et al. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa:A cross-sectional study. Lancet Lond Engl. 2021;397:1265–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safi M. India's shocking surge in Covid cases follows baffling decline. The Guardian. 2021. [[Last accessed 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/21/india-shockingsurge-in-covid-cases-follows-baffling-decline .

- 6.Iftimie S, López-Azcona AF, VallverdúI , Hernández-Flix S, Febrer G de, Parra S, et al. First and second waves of coronavirus disease-19:A comparative study in hospitalized patients in Reus, Spain. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graichen H. What is the difference between the first and the second/third wave of Covid-19?-German perspective. J Orthop. 2021;24:A1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Second waves, social distancing, and the spread of COVID-19 across the USA. [[Last accessed 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8063524/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kim S, Ko Y, Kim Y-J, Jung E. The impact of social distancing and public behavior changes on COVID-19 transmission dynamics in the Republic of Korea. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunno J, Supawattanabodee B, Sumanasrethakul C, Wiriyasivaj B, Kuratong S, Kaewchandee C. Comparison of different waves during the COVID-19 pandemic:Retrospective descriptive study in Thailand. Adv Prev Med. 2021;2021:e5807056. doi: 10.1155/2021/5807056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umakanthan S, Sahu P, Ranade AV, Bukelo MM, Rao JS, Abrahao-Machado LF, et al. Origin, transmission, diagnosis and management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Postgrad Med J. 2020;96:753–8. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arani HZ, Manshadi GD, Atashi HA, Nejad AR, Ghorani SM, Abolghasemi S, et al. Understanding the clinical and demographic characteristics of second coronavirus spike in 192 patients in Tehran, Iran:A retrospective study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Q, Jackson S, Derakhshan S, Lee L, Pham E, Jackson A, et al. Urban-rural differences in COVID-19 exposures and outcomes in the South:A preliminary analysis of South Carolina. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul R, Arif AA, Adeyemi O, Ghosh S, Han D. Progression of COVID-19 from urban to rural areas in the United States:A spatiotemporal analysis of prevalence rates. J Rural Health. 2020;36:591–601. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerala Population Sex Ratio in Kerala Literacy rate data 2011-2022. [[Last accessed on 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/kerala.html .

- 16.Soriano V, Ganado-Pinilla P, Sanchez-Santos M, Gómez-Gallego F, Barreiro P, de Mendoza C, et al. Main differences between the first and second waves of COVID-19 in Madrid, Spain. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;105:374–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupraz J, Butty A, Duperrex O, Estoppey S, Faivre V, Thabard J, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in household members and other close contacts of COVID-19 cases:A serologic study in canton of Vaud, Switzerland. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab149. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalali SF, Ghassemzadeh M, Mouodi S, Javanian M, Akbari Kani M, Ghadimi R, et al. Epidemiologic comparison of the first and second waves of coronavirus disease in Babol, North of Iran. Casp J Intern Med. 2020;11((Suppl 1)):544–50. doi: 10.22088/cjim.11.0.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Htun YM, Win TT, Aung A, Latt TZ, Phyo YN, Tun TM, et al. Initial presenting symptoms, comorbidities and severity of COVID-19 patients during the second wave of epidemic in Myanmar. Trop Med Health. 2021;49:62. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarrett SA, Lo KB, Shah S, Zanoria MA, Valiani D, Balogun OO, et al. Comparison of patient clinical characteristics and outcomes between different COVID-19 peak periods:A single center retrospective propensity matched analysis. Cureus. 2021;13:e15777. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lampl BMJ, Salzberger B. Changing epidemiology of COVID-19. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2020;15:Doc27. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sargin Altunok E, Satici C, Dinc V, Kamat S, Alkan M, Demirkol MA, et al. Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with severe/critical illness in the first wave versus the second wave. J Med Virol. 2022;94:291–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jassat W, Mudara C, Ozougwu L, Tempia S, Blumberg L, Davies MA, et al. Difference in mortality among individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19 during the first and second waves in South Africa:A cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1216–25. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maragakis L. Coronavirus Second Wave, Third Wave and Beyond: What Causes a COVID Surge. [[Last accessed on 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/first-and-second-waves-of-coronavirus .

- 25.Maya C. Delta variant | Kerala needs to analyse its data at granular level. The Hindu. 2021. [[Last accessed 2022 Mar 09]]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/deltavariant-kerala-needs-to-analyse-its-data-at-granular-level/article35992429.ece .