ABSTRACT

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is considered any type of behavior involving the premeditated use of physical, emotional, or sexual force between two people in an intimate relationship. The prevalence of health-seeking attitude towards IPV in India is very low among victims affected by it. The chances of facing violence or even in their maternal life were substantially high among women having lesser education or without any financial empowerment. Data have been quite supportive whenever elevated odds of risk of experiencing controlling behavior from their spouses were concerned. Safety strategies for violence programming could increase monitoring and evaluation efforts to reduce violence. Women with vulnerabilities like being marginalized, least resourced, and disabled are likely to suffer violence in an intimate relationship. Primary care physicians have a definitive role and involvement of other stakeholders like ward members and self-help groups to mitigate such occurrences.

Keywords: COVID-19, intimate partner violence, women

Introduction

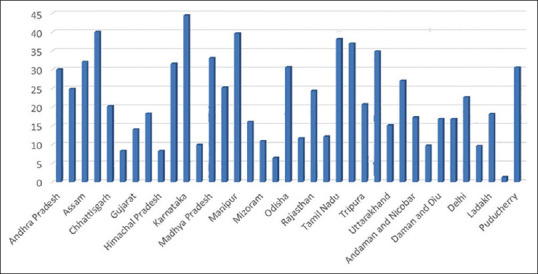

Intimate partner violence (IPV) can be defined as any conduct inside an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual hurt to those in the relationship.[1] It is one of the most imperative causes of morbidity and mortality among women of reproductive age groups worldwide.[2] According to National Family Health Survey-5, 29.3% of all married women aged 18–49 years have experienced spousal violence at least once, which is slightly less (31.2%) than NFHS-4.[3,4] Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of IPV in India. The incidence rate of physical violence during pregnancy was 3.1% among women aged 18–29 years, and 1.5% experienced sexual violence by age 18.[3] IPV occurs in all settings, from religious grounds to various cultures and different socio-economic status. The reporting of IPV has been found to be poor in India and 31 other countries.[4,5] Classic and prominent examples like Mount St. Helens (1980), Hurricane Katrina (2005), the Black Saturday Bush-fires (2009), Earthquake in Haiti (2017) correlate with a higher incidence of IPV with the presence of family stressors, aggression, unemployment, and other associated stressors.[6]

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in different states of India (Source NFHS -5)

Up to 60% of all married women have experienced domestic violence worldwide.[7] To the agony, with the advent of COVID-19 pandemic social detachment of individuals from families, friends, etc., has occurred, resulting in remarkable deviation of conduct. One of the offshoots of the occurrence mentioned above is the rising cases of domestic violence, of which IPV is an evil form. Causal drivers include lockdown-enforced travel restrictions, unusual stays with accomplices, stress, nervousness, and substance abuse. Factors such as underreporting, pathetic access to social and medical care, and lack of awareness and sensitivity act as articulating elements in exacerbating the situation.[8] During the nationwide lock-down, violence against women was more with an almost two fold increase in complaints of violence as per the report by the National Commission for Women statistics.[9]

In a study conducted in Delhi, women reported IPV by 30.6% and controlling behavior by their husbands by 43.2%.[10] Children’s health is influenced directly or indirectly by maternal exposure to domestic violence by the partner or spouse’s family members.[11] National Family Health Survey of 2020–2021 showed that 29.3% of ever-married women of the age group of 18–49 years experienced spousal violence, 3.1% experienced physical violence during any pregnancy, and 1.5% experienced sexual violence.[12] Twenty-two percent of participants experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse (6%), and emotionally abused (10%) by their partner in the past year.[12] Women with relatively advanced education, employment, or earning status than their spouses face more repeated violence than women with lower educational levels.[13]

Intimate partner violence types

It is of different kinds, as depicted below[14]

Sexual abuse: any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act by a person, regardless of their relationship to the victim. This includes touching and rubbing private parts, forced sex, and other forms of intimidation. Rape, defined as physically forced or otherwise forced entry of a penis, another part, or object into the vulva or anus, attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching, and other forms of non-contact are also included.[1]

Physical abuse: pinching, slapping, hitting, kicking, and biting.

Psychological abuse: humiliation, intimidation, insults, threats of harm, intimidation to take away kids.

Delimited behaviors: detaching a person from family and friends, observing their movements.

Imminent risk factors

The most common risk factors for IPV are young age, illiteracy, use of alcohol, smoking and drugs, personality disorders, short temper personality, history of abusing partners, acceptance of violence, and sexual abuse of children.[15,16]

IPV in COVID-19

In India, several studies have found an increased incidence of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic, either due to job loss, psychological stress due to the lockdown, or other factors. Using the routine activity approach, it was found that several newspaper articles about domestic violence were published during the lockdown period.[17] Pattojoshi et al. found a prevalence of domestic violence of up to 18.2% during the lockdown in an online survey period.[18] This study brought into the limelight the disastrous implications of a work-from-home culture where affected spouses were exposed to new violence owing to completely residing all family members during the lockdown period. This was again superimposed by consequences generated due to abstinence from alcohol and other substances.[19]

Potential solutions to tackle IPV

Stronger empowerment of women’s rights related to divorce, dowry, and child support

Should obtain the proper consent of the partner

Promotion of the social and economic self-determination of girls and women.

Social media/Print media campaigns to raise awareness about existing legislation.

IPV should be discussed in a school-based program.

Gender equity

Monthly one-day counseling should be given regarding IPV to risk families.

Use behavioral change communication to achieve social change.

In monthly meetings, in particular, integrate attention to the IPV into sexual and reproductive health services.

Forming the “Survivors’ Network” of IPV and engaging them with various preventive, promotive, and advocacy activities; such as reaching out to suspected victims and supporting them, community engagement and stakeholders involvement for addressing and preventing IPV, undertaking advocacy activities to bring about greater awareness on IPV issues, strengthening policy formulations and interventions to reduce and prevent IPV and respectful rehabilitation of the victims with social security and legal aid support.[20,21]

Strengthen the redressal mechanisms at all levels of society, be it family, community, and workplace, to respond effectively to incidences of IPV.

Carrying out high-intensity campaigns using mass media and social media channels, and community platforms to raise awareness of the issue and remedial measures available for the victims.

Advocating to recognize IPV as a cross-cutting issue and incorporating it into the planning of various sectors, departments, and agencies.

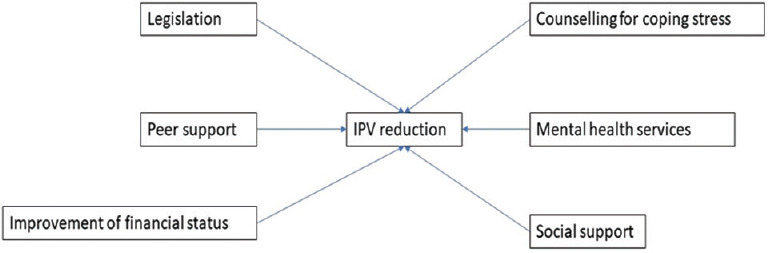

Framework for IPV violence prevention

The following framework with an integrated approach will help in IPV reduction [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Framework for reduction of intimate partner violence (IPV)

Conclusion

IPV is a severe public health problem and is preventable. Most IPV is under-recognized and underreported. This problem was compounded by various cultural beliefs and legal, social, and economic factors. Alcohol, smoking, drugs, and substance abuse are closely transmitted to IPV incidents. This necessitates awareness and sensitizing the community, especially the medical system, which will enable primordial and primary prevention (health promotion). From the prospect of primary care physicians, health education is very crucial to all family members regarding this social issue. Multiple stakeholders like ward members and self-help groups can be engaged in an integrated manner by the medical officer of the primary health center to solve the issue of IPV. Secondary prevention (early screening and intervention), like the strong involvement of community members and local health care workers, can be advocated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization & Pan American Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women: Intimate Partner Violence. World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77432 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood SN, Glass N, Decker MR. An integrative review of safety strategies for women experiencing intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;22:68–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838018823270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) [[Last accessed on 2022 Feb 06]]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml .

- 4.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) [[Last accessed on 2022 Feb 06]]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-5.shtml .

- 5.Goodson A, Hayes BE. Help-seeking behaviors of intimate partner violence victims:A cross-national analysis in developing nations. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP4705–27. doi: 10.1177/0886260518794508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic:Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Foren Sci Int Rep. 2020;12:100089. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. doi:10.1016/j.fsir. 2020.100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agüero JM. COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Dev. 2021;137:105217. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair VS, Banerjee D. “Crisis within the Walls”:Rise of intimate partner violence during the pandemic, Indian perspectives. Front Glob Womens Health. 2021;2:614310. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2021.614310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Malathesh BC, Das S, Chatterjee SS. COVID-19 and domestic violence against women. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102227. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee R, Joshi RK. Controlling behavior and intimate partner violence:A cross-sectional study in an urban area of Delhi, India. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP10831-42. doi: 10.1177/0886260519876720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul P, Mondal D. Maternal experience of intimate partner violence and its association with morbidity and mortality of children:Evidence from India. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0232454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weitzman A. Women's and men's relative status and intimate partner violence in India. Popul Dev Rev. 2014;40:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Organização Mundial da Saúde. 2002. [[Last accessed on 2022 Sep 11]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241545615 .

- 14.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, Meyer SR, García-Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399:803–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnakumar A, Verma S. Understanding domestic violence in India during COVID-19:A routine activity approach. Asian J Criminol. 2021;16:19–35. doi: 10.1007/s11417-020-09340-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pattojoshi A, Sidana A, Garg S, Mishra SN, Singh LK, Goyal N, et al. Staying home is NOT 'staying safe':A rapid 8-day online survey on spousal violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75:64–6. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadkarni A, Kapoor A, Pathare S. COVID-19 and forced alcohol abstinence in India:The dilemmas around ethics and rights. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2020;71:101579. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women, taking action and generating evidence. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564007/en/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Joseph SJ, Mishra A, Bhandari SS, Dutta S. Intimate partner violence during the COVID- 19 pandemic in India:From psychiatric and forensic vantage points. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102279. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]