Abstract

It is important to provide the independent life support individuals with intellectual disabilities need in preparing for employment. The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of the Pre-Employment Independent Life Education Program (PILEP) design based on the needs to inform and support young adults. The research model is a pre-test post-test control group design. Thirty young adults with intellectual disabilities participated in the study. Also, included within the scope of the social validity study were the opinions of the participants and stakeholders in the PILEP. The PILEP consists of three modules: (1) Personal Care and Hygiene, (2) Preparation to Community Life and (3) Health and Safety. A mixed ANOVA (2x3) with two factors was performed to investigate the effectiveness of the PILEP. The results showed that PILEP was effective regarding the knowledge and skills of young adults. A significant difference (p < .05; η2 = 0.94) was found between the experimental group and control group with large effect size. In the social validity study, the opinions of the participants, their parents, employer, job teacher and lead waiter were interviewed. The opinions on the content, presentation, and implementation with multimedia design of the PILEP were positive.

Keywords: Intellectual disability, independent life, preparation to employment, adulthood, education program, experimental study

Introduction

The acquisition of independent living skills for individuals with intellectual disability (ID) especially includes post-school education, job, and vocational education, preparation for adulthood, and lifelong education. Therefore, the post-school adolescence and adulthood period of an individual are critical periods in which the transition to independent life should be focused (Alwell and Cobb 2009; Drew and Hardman 2007; Hanley-Maxwell and Collet-Klingenberg 2012).

Theories of adult development emphasize self-determination skills and independent living skills to keep pace with the maturation and new changes (such as work, marriage, parenting) that occur with the completion of cumulative progressive developmental periods (Kochhar-Bryant and Greene 2009). ‘Adult life’ and ‘working life’ await young individuals in the post-school period. Facilitating the transition of these individuals to adult life and working life depends on acquiring the independent living skills they need during this period (Brolin 1997; Lane 2012).

In the Life Centered Education (LCE) Program which was first developed by Brolin and was revised and expanded in 2012, independent living skills are collected in three basic areas: (a) daily life skills, (b) self-determination and interpersonal skills, and (c) vocational/working skills (Wandry et al. 2013). The independent living skills required in working life are manifested in employability skills. The employability skills for individuals with special needs are (a) basic skills (academic, personal care, communication), (b) integrative skills (technology, social skills, self-determination), and (c) application skills (career planning, vocational skills) (Hanley-Maxwell and Collet-Klingenberg 2012). As can be seen, most of the employability skills refer to the independent living skills of adulthood.

It is seen that the studies on teaching these skills to young adults with ID in the literature are aimed at teaching particular skills (generally daily life skills) rather than comprehensive and multi-dimensional independent life education programs (Belva and Matson 2013). Similarly, the studies on working life focus only on vocational skills. However, working life does not only consist of the vocational skills. According to the research, the least preferred disability group by employers is intellectual disability (Kocman et al. 2018). The basis of the negative attitudes of the employers lies in the idea that these individuals cannot adapt to the workplace even if they learn the vocational skills, and that they are insufficient and unqualified for employment (Kocman et al. 2018; Li 2004; Nota et al. 2014). The reason for this is that the difficulties experienced in the employment of young adults are observed in the independent living skills such as daily living skills, communication skills, interpersonal skills, cooperation, adaptation to work, access to information, safety skills, self-determination, decision making, problem-solving and taking responsibility (Beyer and Robinson 2009; Lane 2012; Hanley-Maxwell and Collet-Klingenberg 2012). It is emphasized that these skills should be studied in a holistic way for sustainable employment (Council for the Education of Exceptional Children (CEC) 2011). After-school education, which includes the teaching of independent living skills that affect working life, is expressed as one of the main resources for integrating young people with ID into the workforce (Judge and Gasset 2015). On the other hand, it is stated that the after-school programs for the teaching of the independent living skills are limited (Plotner and Marshall 2015), and the existing programs are not designed in line with the needs of the young (Luthra et al. 2018; Onukwube 2010). Therefore, comprehensive, extensive, and effective programs are needed to develop all the skills required in adult life (Alwell and Cobb 2009; Bouck 2010). This study was planned based on this need. It has been discussed whether the education program developed to support sustainable employment is effective on young adults with ID.

The studies that offer comprehensive independent life education within a program for the acquisition of these skills for the young adults with ID were examined. Cavkaytar (1999) offered training to young through their families with the ‘Parent training program that taught self-care and domestic skills. In another study, this program was expanded and moved to an online platform (Cankaya 2013). Gumpel and Nativ-Ari-Am (2001) examined the effect of ‘map the instructional universe using general case method’ on teaching young aged 17-21 to shop using a shopping list, pay by card, and practice complex community-based social skills. This method was the basis of a task analytical flow chart of the skills involved in grocery shopping. Riffel et al. (2005) examined the use of a palmtop computer with a Visual Assistant program on vocationally-oriented life skills for young people between the ages of 18-20. The Model of Self Determination integrated occupation-based therapy was used for teaching home skills in a case study (Harr et al. 2011). The Workplace Training Program which included communication skills, emotional control, workplace social behaviors, and work skills were developed to enhance the work-related behaviors in young adults between the ages of 18-40 (Liu et al. 2013). Gomes‐Machado et al. (2016) examined the effects of the vocational training program (The SCOT) on the adaptive behavior of young adults, ages 18-28, and assessed the social impact of employability. Another study evaluated the effectiveness of the TEACCH approach in teaching functional skills such as vocational skills, communication skills, social skills, and life skills to young adults between the ages of 21-40. (Siu et al. 2019). All the programs mentioned in the related studies were found to be effective in the development of independent living skills.

Among these studies, there was only one study that determined the needs of the participants (Liu et al. 2013), and only one study was conducted with an experimental design (Siu et al. 2019). It is thought that the current study contributed to the literature in terms of developing a program considering the needs of young adults with ID and conducting an experimental study with a control group. On the other hand, it was observed that there was a need for applied research that prepares these young adults for independent life after school (Alwell and Cobb 2009; Bouck 2010). However, independent living education is focused on daily life and only vocational skills are emphasized in preparing for employment. Yet many independent living skills that affect employment seemed to be ignored in previous research. There is a need for effective programs in preparing young adults with ID for employment.

Purpose

The main purpose of the study was to investigate the effectiveness of the Pre-Employment Independent Life Education Program (PILEP) that was developed for the needs of young adults with ID and to prepare them for adulthood and working life. In addition, within the scope of the social validity study, the opinions of the participants and stakeholders about the program were determined. The research questions were as follows:

To what extent is the PILEP effective in developing knowledge and skills that young adults need, to prepare for their adulthood and a working life?

- Social validity of the PILEP;

- What are the opinions of young adults (experiment group) about the PILEP?

- What are the opinions of the parents, job teacher, employer and lead waiter of the young adults about the PILEP?

Method

This research consists of mixed method design the study. This research has two studies and both quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques were used. The first stage of the study, which includes investigating the PILEP, was a quantitative study. The second stage of the study, which includes the social validity of the PILEP, was a qualitative study.

A pre-test and post-test control group experimental design was used for investigating the PILEP in the first stage. The independent variable of the study was the PILEP, and the dependent variables were independent living skills and knowledge levels of the participants associated with employment. Participants and stakeholders were consulted to determine the social validity of the PILEP. At the social validity stage of the research, a phenomenological study (with structured and semi-structured interviews) was used.

Participants and setting

In the field of special education, it is very difficult to reach a large number of adults with ID who perform similarly. While determining the participants in line with the purpose of the research, individuals with ID who completed their formal education and continued their vocational education were selected from the province. In this process, criterion sampling, which is a purposeful sampling type, was used. As a result of the examinations and interviews, 30 participants who met the criteria and volunteered to participate in the study were selected. The criteria for inclusion of participants were as follows: living in the province where the study was conducted, completed formal education with a continued vocational education, diagnosed with intellectual disability with mild to moderate, aged between 18-35 years old, had basic skills such as reading comprehension, audio-visual perception, receptive-expressive language skills, follow verbal instructions, adapted to group training. These skills were measured by the first author. She asked them to do the behavior, observed their behavior, and marked the behavior they do and cannot do on a checklist. The exclusion criteria were as follows: continuing formal education, having severe intellectual disability or mixed diagnosis, having other physical disabilities preventing to have basic skills required, be over 40 years old, not having the basic skills required (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants of the experimental stage.

| Characteristics/ | N | SD | Gender |

Level of ID |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Female | Male | Mild | Moderate | ||

| Experimental group | 15 | 26 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 3 |

| Control group | 15 | 29 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 4 |

Note. SD = Mean Age; ID, intellectual disability.

A total of 30 young adults with ID, 12 females and 18 males, between the ages of 20 and 38 participated in the experiment stage. Typical young adults generally refer to the 18-29 age range (Arnett 2010). But in the participants’ group, only three people were in their 30 s. The young adult age range has been stretched considering the intellectual age. Only seven of the participants were diagnosed with moderate intellectual disability, others had a mild ID. However, all meet the inclusion criteria.

They were assigned to the experimental and control groups by random assignment via randomizer.org. As a result, independent living skills play a key role in sustainable employment. The fact that vocational education takes place in its natural environment, on the job, serves the permanence of learning and the generalization of skills to the real environment. In this direction, trainings were held in a cafe where these young people were employed in the city where the practice took place. A setting has been determined as a workplace where the young adults can practice independent living skills. All participants continued their job training in sheltered employment. The study was conducted in this sheltered workshop/workplace (a café). The experimental process was carried out in the seminar hall on the upper floor of one of the workplaces. Participants sat in a u-shape during the training and the instructor presented the multimedia application of the PILEP through the projector in the middle of the hall. Images and animations were shown on the screen, which was in a position that all the participants could see. They did role-playing in the middle of the u-shaped layout from time to time.

At the end of the experimental process, the social validity study was conducted. The experimental group (15) and five stakeholders (parents, job teacher, employer, lead waiter) participated in the social validity stage. Both parents are mothers of two participants in the experimental group and they are nonworkers. One was 49 and the other was 53 years old. The job teacher was the trainer in the workplace where most of the experimental group participants work. The job teacher graduated from special education, and she was 44 years old conducted training in the fields of arts, independent living and social skills in the workplaces. The lead waiter and employer working in this workplace also participated in this phase. The person responsible for young adults was the lead waiter and the employer was the manager of the young adults. The employer was 55 years old, and the lead waiter was 27 years old, and both are high school graduates. The entire research process was carried out by the first author. The treatment fidelity of experimental process was carried out by an independent observer that has a Ph.D. in special education.

Procedure

This research formed part of a multi-stage project led by the authors. An ethics report was obtained from the first author’s University Ethics Committee on 10/10/2016 with ethical committee approval numbered 105775. The development of the PILEP, constituted one pillar of this project. The study of the determination of needs, which is the first step in the development of the PILEP, has been reported in a separate study (Yıldız and Cavkaytar 2020).

Development of the PILEP

The Pre-Employment Independent Life Education Program (PILEP) development stages are as follows: (a) the needs analysis to determine what to teach, (b) determination of aim and content, (c) teaching-learning process and (d) assessment and evaluation. The first stage of the project was previously reported by the authors (Yıldız and Cavkaytar 2020), and the development of the PILEP and the experimental process was carried out in this study.

Determination of the needs

The needs of the young adults with ID were determined by observing them, and taking the opinions of their employers, families, and trainers with semi-structured interviews. The study of the determination of needs was reported and published in the first study of the project (Yıldız and Cavkaytar 2020). According to the findings of the previous study, based on independent living needs of young adults, it was decided by the experts that topics should be included in the program under three main headings as (1) Personal Care and Hygiene, (2) Preparation to Community Life, and (3) Health and Safety (Yıldız and Cavkaytar 2020).

Determination of the aim and the content

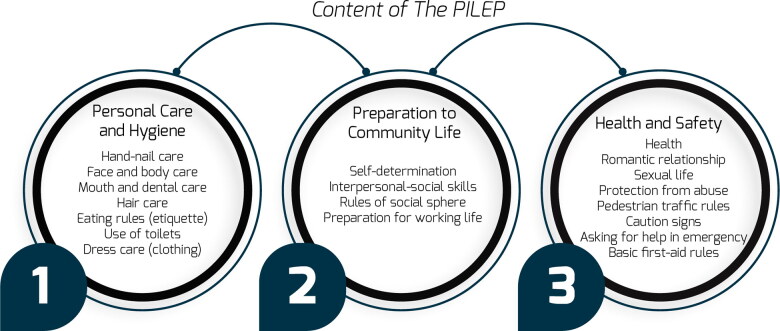

The PILEP consists of 16 sessions, each one hour long, using a multimedia application. The aim of the PILEP was to develop the knowledge and skills of young adults with ID regarding independent living to prepare them for adulthood and working life. The content and goals were finalized after interviewing experts in the field of special education and program design. There is total of 70 goals, including cognitive and psychomotor in the PILEP. The goals of the PILEP are addressed at young adults with moderate and mild ID, there are no personal goals. As shown in Figure 1, The PILEP consisted of three modules. The modules include text, visual, audio, and animations on how to use each knowledge and skill in the workplace.

Figure 1.

Content of the PILEP.

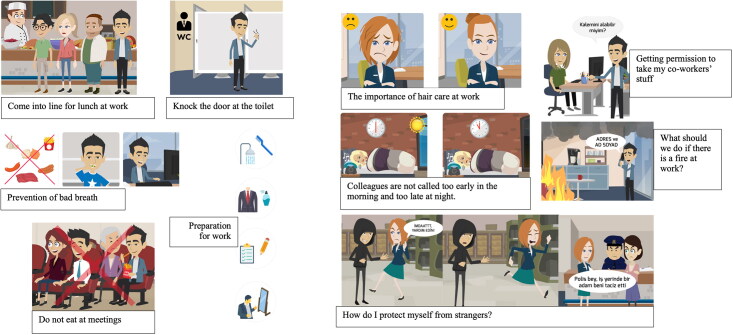

In each module, knowledge-level content is presented with visuals and skills are presented with animations. The content in the PILEP is independent living skills required in the workplace and employment. Figure 2 shows examples of some images in the PILEP.

Figure 2.

Sample Pictures from the PILEP Mutlimedia Application.

The difference of the PILEP from other independent living programs is that it focuses on the independent living skills needed in the employment process rather than daily life and aims to holistically support all independent lives rather than teaching certain skills. While other programs often involve the acquisition of skills, the aim of the PILEP is to teach use existing skills correctly and appropriately for the context. The PILEP includes important points to be considered in the use of independent living skills in the working life. It focuses on the young adult’s ability to organize and to use their existing knowledge, skills, and behaviors in the appropriate place, time, and frequency. The content of the PILEP consists of interpersonal skills that should be known in all professions. Another difference in the PILEP is the development of an application specially designed for the young adults with ID. The PILEP consists of content for people with ID over the age of 18. The knowledge content was usually supported with images and texts. The skill content was generally supported with animations.

Teaching-learning process

The essential learning material is the PILEP developed as a multimedia application containing audio-visual aids and animations. Mayer’s (2014) multimedia design principles were adapted to the special education field in this process. For example, excluding all off-topic visuals in the worksheet, removing all distracting elements from the design, focusing on the target behavior (consistency principle), changing the color and size of the text related to the subject taught, or zooming in on the visual (the principle of attracting attention), etc. In addition, three handbooks for each module were handed out during the training. The trainer made use of techniques such as presentation strategy, direct instruction, question-answer technique, modeling, animation, and demonstration-making on the training sessions (Borich 2016). She taught the knowledge and skills to the participants by using these techniques and the multimedia application and handbook.

Assessment and evaluation

Knowledge tests and a skill inventory developed by the first author were used to examine the impact of the PILEP. Social validity question forms were used at the social validity stage. Details are in the ‘Data Collection and Techniques’.

Implementation of the PILEP

In the pilot study the first module was presented in two sessions and the first author’s presentation style was evaluated by an independent observer. In addition, the use of program evaluation tools was tested.

The experimental process was carried out in July 2018 by group training in the workplace where young adults continued their vocational training. The experimental process lasted a month. In the group training, young adults sat in a U-shape. The PILEP multimedia application was projected on the wall so that all of them could see. The training process was completed in 16 sessions, each one lasting 45 min. In the lectures the instructor actively used the PILEP multimedia application, created discussions with the question-answer technique, animated the sample scenarios with the participants and performed as a model for appropriate behaviors. For the skills in the PILEP, animation videos containing the skill steps were watched, and then the participants were asked to do these steps. The instructor became a model by animating these steps. The content at the knowledge level in the PILEP was explained by the instructor using the visuals in the multimedia app. In matters related to interpersonal skills and social rules, the participants were divided into groups of two and three, and role-playing activities were carried out. Homework was given in each session and follow-up homework was provided by forming a WhatsApp group with the parents.

Data collection and techniques

To investigate the effects of the PILEP, three knowledge tests (module 1-2-3) and a skill inventory (module 1) were used as a pre-test and post-test. Structured and semi-structured interviews were used to evaluate social validity. All the tools were developed by the first author.

Development of the knowledge tests

The knowledge tests developed in this study were for young adults with ID. For this reason, validity studies have been carried out with considerations for the difficulties in creating large samples with similar characteristics. At this stage, the steps were followed (Adiguzel 2019); (1) Creating knowledge test questions: According to Bloom’s developed cognitive domain classification for each module, four-choice multiple-choice, true-false and multiple-choice questions were written. (2) Presenting knowledge test questions for expert evaluation and opinion: Three knowledge tests with 20 questions for each of the three modules were developed. In the first stage 20 experts (13 in special education, five in assessment-evaluation) evaluated the suitability of the question items to the cognitive domain level, the assessments, and evaluations. In addition, the content validity ratio (CVR) of all question items and the content validity index (CVI) of each module was calculated. The smallest CVR value from the expert team of 20 people was 0.42 and the smallest CVI value was 0.67 (Adiguzel 2019). The lowest CVR of the knowledge tests question items was calculated as 0.7, and the highest CVR as 1. The CVI for the first and second module was found to be 0.99 and the CVI for the third module was 0.98.

The fact that Webb's (2007) ‘balance of representation index’ value between the question items and the gains is .70 or above indicates that the items represent the gains in a mostly balanced way (Adiguzel 2019). The ‘balance of representation index’ values were respectively calculated as follows: First module 0.92, second module 0.96, third module 0.90.

In the second stage the tables of the questions in the tests were coded by five field experts. According to Miles and Huberman, coding between experts and the researcher is calculated with the formula ‘Agreement/Agreement + Disagreement’ and the coding consistency should be at least 70% (Adiguzel 2019). It was calculated as 94% in this study. In addition, the question items of each module were coded according to Bloom's classification by five experts and the Fleiss Kappa statistics were calculated. The kappa value of the first module was 0.83, the second module was 0.90, and the third module was 0.78. Accordingly, expert evaluations on the appropriateness of the question items to the cognitive domain level are in strong agreement. Whether the knowledge test was understandable by the young adults with ID, whether it was easily implemented, and the answering time to the questions were examined in the pilot study.

As a result, the knowledge test items were found to be valid and reliable in terms of content and measurement-evaluation structure. The highest score that could be obtained from each knowledge test was 100 and the lowest was 0.

Development of the skill inventory

There were both cognitive and psychomotor goals in the Personal Care and Hygiene module. The psychomotor goals were measured with the skill inventory by observing young adults. The skill inventory developed by the first author was on the three-point likert scale scored as Insufficient (0), Partially Sufficient (1), Sufficient (2) and Not Proportional (x). There were 94 items in the skill inventory covering all units of the Personal Care and Hygiene module. The highest score that can be obtained from the skill inventory was 94 × 2 = 188, the lowest score was 94 × 0 = 0. In the second evaluation phase of the knowledge test on the use of the scaling system and the skill inventory received opinions from five experts. They also examined the items in terms of structural suitability. Content validity of the checklist was evaluated by 20 experts who were consulted during the goal writing phase of the program. The lowest CVR of the 94 items was calculated as 0.8 and the highest CVR as 1. The CVI for the skill inventory was found to be 0.92. The skill inventory was examined in the pilot study in terms of suitability and observation time for the young adults with ID. The skill inventory was filled in by researchers, families, workplace personnel, and job teachers. In addition to observing the young adults, stakeholders who know the young people best were consulted to avoid subjective evaluation while filling in the skill inventory. The effectiveness data of the study were collected by applying a pre-test before the presentation of each module and a post-test at the end.

The skills inventory was filled in by the researcher by observing the participants at work. To observe all the skills in the inventory, the researcher made long-term observations. Parental views were also sought, especially on issues such as health and personal care.

Development of the social validity question forms

The participants had difficulty in answering the open-ended interview questions due to their intellectual disabilities. Therefore, a structured form was prepared for them. They were presented with a question form (structured interview) with closed-ended questions and short-answer writing-based questions. Semi-structured interview forms were used to determine the stakeholder views.

The structured interview form consisted of a total of 12 questions with eight closed-ended which there are ‘yes-neutral-no’ options and four short answers. Semi-structured interview form included seven open-ended questions. In both forms there were questions about the content of the PILEP, the manner of presentation, the multimedia application, the effect of the PILEP on daily life and the likes and dislikes of the PILEP. The structured interview form was presented to 20 field experts. Semi-structured interview questions were also examined by five field experts.

Validity and reliability

Validity studies of data collection tools were made and explained under the title of ‘Data Collection and Techniques’. To ensure experimental control, factors that may affect internal and external validity were tried to be controlled. In addition, a treatment fidelity was conducted to determine whether the implementation was carried out as planned. In the internal validity process the implementation period was one month which controlled the maturation effect. Conducting the tests before and after the implementation, controlled the investigating effect and the validity and reliability studies of the tests kept the measurement factor under control. In the external validity process, controlling the implementation times of the tests and the interaction of pre-test post-test and implementation, the sensitivity effect on the post-test was put under control. There is no selection-implementation interaction due to random assignment. The experimental and control groups were not physically close during the experimental process. For those who might know each other, their families were informed not to contact each other by phone or anything else. What training the control group received on which day and time and what they did in the other workplace were followed, monitored, and reported by second author.

Experimental and control groups were groups that received training in different places and did not interact. No special training was provided to the control group. They continued their usual vocational training with the job teacher at another workplace. After the experimental process the PILEP training was also given to the control group. The entire process has been reported in detail and repeatable. Ten sessions (at least 30%) selected randomly from the training sessions were monitored by an independent observer. Treatment fidelity was calculated to be 98% indicating that the instructor presented the program as planned, using the formula ‘Happening Instructor Behaviors/Planned Instructor Behaviors x 100’. In the use of this formula a checklist containing the behaviors that the instructor should do during a session was used. In this list, there are behaviors such as the instructor telling the young adults the aims of the lesson, presenting the training in accordance with the session plan, using a clear and understandable language, using the multimedia application, distributing each course handbook, and answering the questions of the participants.

Data analysis

Although all modules had the knowledge test, only first module had the skill inventory. Therefore, the dependent variables were not of equal order. The knowledge and skill level were analyzed separately. For the data obtained from the three knowledge tests of each module, the pre-test post-test gained scores were analyzed with a two-factor (2 × 3) mixed ANOVA. Since there is a separate knowledge test for each module in this study, there were three pre-test and three post-test scores. To reduce this score to a single level, the difference between the knowledge pre-test and post-test of each module in the experimental and control groups were calculated. Factor 1 refers to independent groups (experimental-control), factor 2 refers to module type (1-2-3). The skill inventory was analyzed by two factors (2 × 2) mixed ANOVA. Factor 1 refers to independent groups (experiment-control), factor 2 refers to repeated measures (pre-test; post-test).

Mixed ANOVA prerequisites were tested for all data. According to George and Mallery (2014), if the skewness and kurtosis values are between −1 and +1, they are ‘excellent’ and between −2 and +2 ‘acceptable’ levels. According to the pre-analysis results, only three values in the data set in the study are below −1 and were in the ‘acceptable’ range, while the others were in the ‘excellent’ range. The p values for the Shapiro-Wilk test in all groups ranged from 0.61 to 0.79 and all were greater than 0.05 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kurtosis and skewness values of all measurements.

| Modules | Module1- Knowledge- Pretest |

Module1- Knowledge- Posttest |

Module1- ControlList- Pretest |

Module1- ControlList- Posttest |

Module2- Knowledge- Pretest |

Module2- Knowledge- Posttest |

Module3- Knowledge- Pretest |

Module3- Knowledge- Posttest |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. | Skew. | Kurt. |

| Exp. | −0.01 | −0.15 | −0.66 | −0.60 | 0.41 | −0.99 | −0.26 | −1.78 | 0.81 | −0.13 | −0.28 | −0.70 | 0.07 | 0.63 | −0.12 | −1.08 |

| Con. | 0.07 | −0.99 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.73 | −0.79 | 0.60 | −1.14 | 0.57 | −0.96 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.45 | −0.79 |

Note. Exp .= Experimental; Con. = Control; Skew. = Skewness; Kurt. = Kurtosis.

Levene test statistic of all measurements is greater than .05 (module 1 knowledge pre-test F(1, 28) = 0.511; p = 0.481, module 1 skill inventory pre-test F(1, 28) = 0.380; p = 0.542, module 2 pre-test F(1, 28) = 0.48; p = 0.828, module 3 pre-test F(1, 28) = 0.195; p = 0.662, module 1 knowledge post-test F(1, 28) = 0.619; p = 0.438, module 1 skill inventory post-test F(1, 28) = 0.874; p = 0.358, module 2 post-test F(1, 28) = 0.074; p = 0.788, module 3 post-test F(1, 28) = 0.339; p = 0.565), variances are matched. Experimental and control groups are independent groups.

Results

Effectiveness of the PILEP on developing knowledge and skills

Effectiveness of the PILEP on the knowledge level

The PILEP is a package program. To examine the effect of PILEP, knowledge-level measurements were taken together. To examine the effect of all modules together and to see the interaction between modules, the 2 × 3 mixed ANOVA with two factors was used by calculating gained scores. In this analysis design the dependent variable is the gained score between pre-test and post-test. The first independent variable is the group (experiment-control), the second independent variable is the module type (module 1-2-3).

The significance level of Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity W value was 0.584, which means that the sphericity prerequisite was met (p > .05), and the performance change between modules did not differ from group to group.

When the findings summarized in Table 3 were examined, it could be seen that the gained rates between the pre-test and post-test scores did not change from module to module (F(2, 56) = 2.888, p > .05). In other words, the performances of the participants were similar between the modules.

Table 3.

Comparison of knowledge tests pre-test and post-test mean scores of all modules according to group: Mixed ANOVA results.

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Subjects | |||||||

| Module | 633.889 | 2 | 316.944 | 2.888 | 0.064 | 0.09 | 0.543 |

| Module x Group | 353.889 | 2 | 176.944 | 1.612 | 0.209 | 0.05 | 0.327 |

| Error (Pretest-Posttest) | 6145.556 | 56 | 109.742 | ||||

| Between Subjects | |||||||

| Group | 53777.778 | 1 | 53777.778 | 410.169 | 0.001 | 0.94 | 1.000 |

| Error | 3671.111 | 28 | 131.111 |

Note. df = Degrees of freedom; F = F statistic; p = Level of statistical significance; η2 = Eta-squared.

On the other hand, it could be seen that there was a very significant difference between the gained scores of the groups who participated in the PILEP and those who did not, regardless of the module, and the effect size was also high (F(1, 28) = 410.169; p < .05; η2 = .94). Considering these findings, it can be said that the average scores of the experimental group in each module of the PILEP were significantly higher than the control group showing that the program was quite effective.

Effectiveness of the PILEP on the independent living skills level

In the two factor (2 × 2) mixed ANOVA, the p-value decreased from .05 to .0125 with Bonferroni because the experimental, control, pre and posttest were four measurements (0.05/4 = 0.0125). The sphericity prerequisite was tested by the Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity. The significance level of the W value was found to be .00 (p < .05) for all measurements, and the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was considered (Huck 2009).

As seen in Table 4, the difference between pre-test and post-test was significant (F(1, 28) = 200.03; p < .001; η2 = .88); and a significant difference with a large effect size was also observed between the experimental and control groups (F(1, 28) = 15.542; p < .001; η2 = .36).

Table 4.

Comparison of personal care and hygiene module skill inventory pre-test and post-test mean scores according to group: Mixed ANOVA results.

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Subjects | |||||||

| Pretest-Posttest | 12877.350 | 1 | 12877.350 | 200.03 | 0.000 | 0.88 | 1.000 |

| Pretest-Posttest x Group | 13771.350 | 1 | 13771.350 | 213.888 | 0.000 | 0.88 | 1.000 |

| Error (Pretest-Posttest) | 1802.800 | 28 | 64.386 | ||||

| Between Subjects | |||||||

| Group | 18480.150 | 1 | 18480.150 | 15.542 | 0.000 | 0.36 | 0.967 |

| Error | 33294.000 | 28 | 1189.071 |

Note. df = Degrees of freedom; F = F statistic; p = Level of statistical significance; η2 = Eta-squared.

Although the interaction effect of the change from pre-test to post-test between experimental and control groups was significant (F(1, 28) = 213.888; p < .001; η2 = .88), when this interaction was examined (t-test), the increase in the experimental group from pre-test to post-test was quite significant (t(14) = −17.071; p < .001), however, it was seen that the difference between pre-test and post-test in the control group was not significant (t(14) = 0.448; p > .001). Therefore, the change in skill level in the Personnel Care and Hygiene module was significant only in the experimental group.

Social validity of the PILEP

In the social validity study, the opinions of the experimental group participants and their job teacher, parents, employer, and lead waiter’s satisfaction were determined. They were asked to comment on the PILEP multimedia application, the instructor's style of expression, the likes and dislikes of the education, the content, implementation, and results of the program. A structured-interview form was administered to the experimental group participants after the implementation. One month after the implementation was completed, semi-structured interviews were conducted with five volunteers consisting of mothers, the job teacher, the employer, and the lead waiter of the participants. Data from the closed-ended questions in the structured-interview form were analyzed by descriptive analysis, data from the open-ended questions in the structured interviews and the semi-structured interviews were analyzed by content analysis. The steps were followed in the content analysis: transcribing the voice recordings (raw data), organizing the data, and preparing it for analysis, reading all the data thoroughly, coding the data, creating meaningful themes, associating the themes, and interpreting the themes (Creswell 2014).

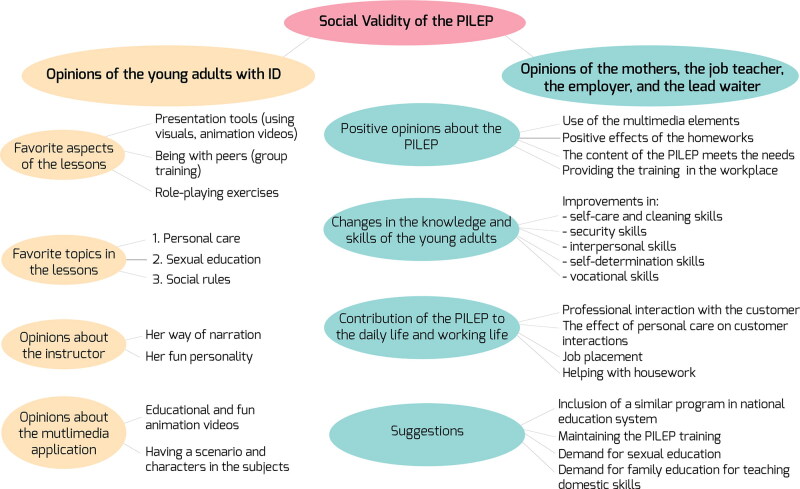

In the closed-ended questions, the experimental group was asked whether they liked the content of the training, the way of presentation, the narrator's expression, and communication. All participants answered ‘yes’ to these questions. The open-ended questions analyzed with content analysis and the themes from these questions were shown in the Figure 3. According to the Figure 3, the findings from the young adults with ID were discussed in four themes. As can be seen in the first theme, the favorite aspect of the lessons for young adults with ID were presentation of the PILEP by using visuals and animation videos, being with peers and role-playing exercises. One of the young adults said that “…my favorite aspect of the lessons were the great videos and animations…”, another said that “…I made friends in the lessons, it’s nice to be with them…”, the other said “…The best part was the role-playing exercises…”. The young adults stated that they liked the most the personal care, sexual education, and social rules topics. The young adults liked the instructor’s narration and her fun personality. One of them said that “…I liked my teacher's lecture very much, it was very enjoyable…”, another said that “…I wish the lessons didn’t end…”. In addition, most of the young adults expressed their opinions about the multimedia application and stated that the use of animation videos, scenario and character was fun and instructive.

Figure 3.

Social validity findings of the PILEP.

The findings obtained from the interviews with the mothers, the job teacher, employer, and the lead waiter of the experimental group were collected in four themes using content analysis. These findings are also shown in Figure 3.

According to the findings in Figure 3 it was concluded that the PILEP met the needs of the young adults, the content of the PILEP was very comprehensive. It has been stated that the training given in the workplace created the opportunity to apply what is learned in the real environment and interactive presentation style using animations has positive effects. One of the mothers expressed her opinion as follows: “…this program was very good to avoid some problems after getting settled in the job…”. The opinion of the lead waiter at the workplace regarding the presentation of the PILEP was as follows: “…Visuality was at the forefront of the presentation. It is easier for them to see and perform, since you turned the process into a visual, learning became permanent. Our children do not forget what they see…”.

Stakeholders stated that after the training young adults’ knowledge and skills in self-care, security, interpersonal, self-determination and vocational are changed positively. The employer's view on areas of improvement after the training is as follows: “…Personal care at work was very important to us. We no longer remind, whether you have cut your nails, sprayed your perfume or shaved your beard…”. Participants stated that the PILEP contributed to the young adults’ daily life and working life. The lead waiter's view on the contribution of the program to working life is as follows: “…They didn't do anything without command or clue. Now, as soon as the customer comes, they stand up, they say welcome, everything has changed…”. The job teacher said “… the setting was the right place for practice, it was a very good place, it happened in its natural environment. As soon as they left the class, they said that I must do this now… It was implemented right after the training, it triggered it, it was not forgotten…” for the training to be given in the workplace.

Stakeholders suggested inclusion of a similar program in the national education curriculum, continuation of the PILEP, and sexual education and family education on domestic skills in future trainings.

Discussion

The PILEP was found effective in developing participants' knowledge and skills about independent living. It has been seen that there is a significant difference between the gained scores of the groups and the large effect size (F(1, 28) = 410,169; p < .05; η2 = .94). This can be explained by the fact that participants saw many topics in PILEP for the first time. The PILEP included content that they needed in adulthood and working life, but that they didn’t get in their formal education.

As stated earlier, in the literature there are studies in which programs like the PILEP were implemented. These programs have been found effective in supporting young adults’ working life and independent living (Cankaya 2013; Cavkaytar 1999; Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016; Gumpel and Nativ-Ari-Am 2001; Harr et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2013; Riffel et al. 2005; Siu et al. 2019). The fact that the PILEP is effective in this study shows that its effectiveness findings are consistent with the literature. In these studies, most of the comprehensive independent living education programs in preparation for adulthood focus only on daily life skills (Bouck 2010; Cankaya 2013; Cavkaytar 1999; Gumpel and Nativ-Ari-am 2011; Harr et al. 2011). It is seen that sustainable employment, another pillar of independent living is ignored or only focused on teaching certain vocational skills (Ellenkamp et al. 2016). At this point, this study differs in that it determines the needs of the adult group with ID and deals with the independent living skills necessary for sustainable working life through these needs. Although the PILEP basically includes independent living knowledge and skills, this content is structured to ensure employability.

In this study, the PILEP was presented by using the multimedia application which was adapted to the learning characteristics of young adults with ID. The fact that multimedia design principles were adapted to the young adults with ID may have a role in the effectiveness of the PILEP. In only one of the studies in which the program was prepared by the researchers, the program was developed around the needs of the participants (Liu et al. 2013). In the current study, different from the literature, the PILEP was designed based on the needs and the learning material was adapted to the characteristics of the participants. It is thought that the study is original in terms of the design of the PILEP.

It was observed that health and safety issues (especially sexual education, protection from harassment and abuse), have not been included in programs of other related studies. Therefore, the PILEP differs from other programs in preparing for adulthood and employment. This difference may have risen from the needs of the target group which can be explained by the limited education on sexuality in many countries (Brown and McCann 2018; Swango-Wilson 2011) although it is one of the areas where the most intense support is needed (Bryne 2018; Gil-Llario et al. 2019; Gimenez-Garcia et al. 2017). On the other hand, the literature shows that one of the biggest difficulties in the participation of young adults in working life is abuse (Gil-Llario et al. 2019; Gimenez-Garcia et al. 2017; Nye-Lengerman et al. 2017), and that sexual education is needed to protect the people from abuse and allow them to live safely in society (Brown and McCann 2018; Bryne 2018; Swango-Wilson 2011). This issue has become very important for working life in the needs and it has been a big place in the third module. It is thought that the fact that sexual education and safety issues were in the PILEP will both contribute to the literature and will have a significant effect on the daily life of the participants in terms of living confidently and without being dependent on anyone. The PILEP differs in this aspect as well.

In the research, the PILEP was presented in 16 sessions for one month in a group training setting. In the relevant literature one-on-one training was carried out in five studies (Cankaya 2013; Cavkaytar 1999; Gumpel and Nativ-Ari-Am 2001; Harr et al. 2011; Riffel et al. 2005), and group training in three studies (Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2013; Siu et al. 2019). When the implementation periods of these studies were examined, it was seen that the trainings were carried out in 18 sessions (Cankaya 2013; Cavkaytar 1999), 20 sessions (Gumpel and Nativ-Ari-Am 2001), and 21 sessions (Riffel et al. 2005), and in terms of time, for two months (Siu et al. 2019), six months (Liu et al. 2013) and ten months (Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016). It has been shown that the training period of the PILEP largely overlaps with the literature. Therefore, the session duration of the study was a suitable time. In group session with young people and adults with ID, it can be stated that comprehensive training can take about 15-20 sessions.

The most frequently emphasized subject by all participants in the social validity findings was the PILEP's presentation style and content. The multimedia design used in the presentation of the PILEP and the presentation style of the trainer attracted great attention. In the relevant literature social validity studies were conducted in only two studies (Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016; Riffel et al. 2005). Data were collected from participants with ID in one of these studies, (Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016) and from both participants with ID and their job teachers in the other (Riffel et al. 2005). In these studies, where social validity studies were carried out, opinions about the program presented were received and positive results were obtained from them, too (Gomes‐Machado et al. 2016; Riffel et al. 2005). Since the social validity study, which was not carried out in most related studies, was carried out by collecting data from all participating groups in this study, it is thought that this study will make a significant contribution to the literature and will also serve to improve group training processes in which young adults interact one-on-one. The employer and lead waiter stated that there were improvements in the workplace, especially in personal care and interaction with customers, while families stated that young adults started to help with housework. However, the most important thing in the social validity is that direct interviews were conducted with young adults, who were the primary interlocutors of the experimental stage. As a result of these interviews, the fact that young adults were satisfied with the process, liked the multimedia application and were sad because their lessons were over made this study powerful.

The strengths of this study include the design of the PILEP based on the needs of young adults, adapting the design principles to special education in the design of the multimedia application of the PILEP, presenting it by a special education specialist, carrying out the training in the workplace, conducting group training for 16 sessions with 15 young adults who have serious difficulties in areas such as understanding abstract concepts, providing attention, working with a team and using experimental research design which includes a control group. The different aspect of the intervention is that it is not limited to the teaching of a few skills, does not focus directly on daily life skills, and supports non-professional skills in working life so that working life is sustainable. Finally, another group of experimental studies with young adults with ID in this field has not been found in the national literature. The weaknesses of the study can be expressed as that the PILEP can be evaluated largely at the level of knowledge and limited to 30 young adults. In addition, in the previous study involving the determination of the needs (Yildiz and Cavkaytar 2020), the opinions of the young adults could not be taken because they had difficulty in expressing their own difficulties, needs, instead, the young adults were observed.

The need for group experimental studies on supporting independent living with young adults continues. In further research, experimental research can be planned by applying the PILEP with more participants and/or groups with different disabilities. The effect of the PILEP on different variables such as the participants' quality of life, different behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions can be examined. More comprehensive experimental studies with family participation can be planned on health and safety in the future. Finally, the multimedia application used in the presentation of the PILEP can be transformed into an interactive interface that young adults can directly use on their own to support their independence and learning.

The biggest limitation of this study was the difficulty in finding young adult participants who met the prerequisites and had similar characteristics of intellectual disability at the experimental stage. For this reason, the experimental process could be carried out with only 30 participants. This situation creates a limitation in the generalization of the study findings. However, group experimental studies involving young adults with ID in special education research are quite limited and the samples are small. It is thought that the experimental phase of this study will set an example for future special education research. To increase the widespread impact, the PILEP was shared with educational institutions at the end of the research and made available to be used by young people and adults with ID. On the other hand, since there is no suitable scale for the young adults with ID to examine the effect of the PILEP, knowledge tests and the skill inventory was developed to monitor the development of knowledge and skills within the PILEP.

Conclusion

At the end of this study, an education program was designed that is effective in improving the knowledge and skills of young adults with ID regarding working life and independent living, supporting sustainable employment, and adapting to the learning characteristics of the participants. The PILEP is an open-access resource in preparation for the after-school and working life and it is accessible to all youngs with ID, their families, and teachers in our country. The PILEP covered critical topics that were ignored in preparation for working life and adulthood. In particular, interpersonal skills at work, being well-groomed at work and interaction with customers, and sexual education are not included in any after-school education in the country where the study was conducted.

Commonly, special education practices are carried out with individualized teaching. The group trainings were organized with 15 young adults between the ages of 20-38. Working with a group with ID during the experiment, gave the researcher different experiences. In the process of group training, the mental, social, emotional, and psychological characteristics of the participants required various arrangements in teaching. For example, the researcher took precautions such as changing the seating arrangement, setting classroom rules, and using a reward system to prevent inappropriate interactions of the participants with each other to ensure classroom control, and assigning homework to reduce inappropriate behaviors. Activities and digital games were chosen as rewards suitable for the adult group.

Conducting group training with people with ID is a rare and challenging process. As a result of the study, it can be stated that dividing the participants into small groups, role-playing activities and peer observation for the group trainings with adults to be effective. This study also contributes to the literature as one of the rare group experimental studies conducted with people with ID in the field of special education.

In conclusion, the PILEP was found effective and socially valid. According to the social validity findings, young adults want to receive training on independent living in preparation for working life after their formal education, and they are very positively affected by group training with their peers. Other researchers may organize more group trainings with adults. According to the findings obtained from the stakeholders, the after-school training and the independent living skills are important for sustainable employment. It is thought that programs such as the PILEP are needed for employers to employ the youngs with ID.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adiguzel, O. C. 2019. Need analysis handbook in the development of educational programs. 2nd ed. Ankara: Ani Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Alwell, M. and Cobb, B.. 2009. Functional life skills curricular interventions for youth with disabilities: A systematic review. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32, 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. 2010. Adolescence and emerging adulthood. 4th ed. USA: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Belva, B. C. and Matson, J. L.. 2013. An examination of specific daily living skills deficits in adults with profound intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, S. R. and Robinson, C.. 2009. A review of the research literature on supported employment: A report for the cross-government learning disability employment strategy team. London: MRC Center for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Borich, G. D. 2016. Effective teaching methods: Research-based practice. 9th ed. USA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Bouck, E. C. 2010. Reports of life skills training for students with intellectual disabilities in and out of school. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 54, 1093–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolin, D. E. 1997. Life centered career education: A competency-based approach. 5th ed. USA: The Council for Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. and McCann, E.. 2018. Sexuality issues and the voices of adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 74, 124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryne, G. 2018. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with intellectual disability: A review of the recent literature. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 294–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cankaya, S. 2013. Development and evaluation of skills training software for families in teaching self-care and home skills to youngs with intellectual disabilities. PhD. Anadolu University. [Google Scholar]

- Cavkaytar, A. 1999. The effectiveness of a family education program in the teaching of self-care and home skills to youngs with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 2, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Council for the Education of Exceptional Children (CEC). 2011. Reauthorization of the workforce investment act (WIA): Priorities and concerns for students with disabilities. Issue Brief. Arlington: CEC. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, C. J. and Hardman, M. L.. 2007. Intellectual disabilities across the lifespan. 9th ed. USA: Pearson Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenkamp, J. J., Brouwers, E. P., Embregts, P. J., Joosen, M. C. and van Weeghel, J.. 2016. Work environment-related factors in obtaining and maintaining work in a competitive employment setting for employees with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 26, 56–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, D. and Mallery, P. 2014. IBM SPSS statistics 21 step: A simple guide and reference. 14th ed. USA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Llario, M. D., Morell-Mengual, V., Díaz-Rodríguez, I. and Ballester-Arnal, R.. 2019. Prevalence and sequelae of self-reported and other-reported sexual abuse in adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 63, 138–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Garcia, C., Gil-Llario, M. D., Ruiz-Palomino, E. and Diaz-Rodriguez, I.. 2017. Sexual abuse and intellectual disability: How people with intellectual disabilities and their professionals identify and value the experience. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 4, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes‐Machado, M. L., Santos, F. H., Schoen, T. and Chiari, B.. 2016. Effects of vocational training on a group of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gumpel, T. P. and Nativ-Ari-Am, H.. 2001. Evaluation of a technology for teaching complex social skills to young adults with visual and cognitive impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 95, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Maxwell, C. and Collet-Klingenberg, L.. 2012. Preparing students for employment. In: Wehman P. and Kregel J., eds. Functional curriculum for elementary and secondary students with special needs. USA: PRO-Ed, pp. 529––561. [Google Scholar]

- Harr, N., Dunn, L. and Price, P.. 2011. Case study on effect of household task participation on home, community, and work opportunities for a youth with multiple disabilities. Work (Reading, MA), 39, 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huck, S. W. 2009. Statistical misconception. USA: Psychology Press Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, S. and Gasset, D. I.. 2015. Inclusion in the workforce for students with intellectual disabilities: A case study of a spanish postsecondary education program. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar-Bryant, C. A. and Greene, G.. 2009. Pathways to successful transition for youth with disabilities: A developmental process. New Jersey: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Kocman, A., Fischer, L. and Weber, G.. 2018. The employers’ perspective on barriers and facilitators to employment of people with intellectual disability: A differential mixed‐method approach. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 31, 120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, V. 2012. Examining attachment in person with a disability and their transition to independent living. MA: Saint Mary’s College of California. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E. P. Y. 2004. Self-perceived equal opportunities for people with intellectual disability. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue Internationale de Recherches de Readaptation, 27, 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. P., Wong, D., Chung, A. C., Kwok, N., Lam, M. K., Yuen, C. M., Arblaster, K. and Kwan, A. C.. 2013. Effectiveness of a workplace training programme in improving social, communication and emotional skills for adults with autism and intellectual disability in Hong Kong-a pilot study. Occupational Therapy International, 20, 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra, R., Högdin, S., Westberg, N. and Tideman, M.. 2018. After upper secondary school: Young adults with intellectual disability not involved in employment, education or daily activity in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 20, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. 2014. The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. 2nd ed. UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nota, L., Santilli, S., Ginevra, M. C. and Soresi, S.. 2014. Employer attitudes towards the work inclusion of people with disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 27, 511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye-Lengerman, K., Narby, C. and Pettingell, S.. 2017. Bringing Employment First to Scale: What is the relationship between gender end employment status for individuals with IDD? University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion. [Google Scholar]

- Onukwube, V. C. 2010. Experiences, feelings, and perceptions of former foster care youth about independent living program. PhD. Walden University. [Google Scholar]

- Plotner, A. J. and Marshall, K. J.. 2015. Postsecondary education programs for students with an intellectual disability: Facilitators and barriers to implementation. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 53, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffel, L. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., Turnbull, A. P., Lattimore, J., Davies, D., Stock, S. and Fisher, S.. 2005. Promoting independent performance of transition-related tasks using a palmtop PC-based self-directed visual and auditory prompting system. Journal of Special Education Technology, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, A. M., Lin, Z. and Chung, J.. 2019. An evaluation of the TEACCH approach for teaching functional skills to adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 90, 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swango-Wilson, A. 2011. Meaningful sex education programs for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 29, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wandry, D., Wehmeyer, M. L. and Glor-Scheib, S.. 2013. Life centered education: The teacher’s guide. USA: Council for Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, G. and Cavkaytar, A. 2020. Independent living needs of young adults with intellectual disabilities. Turkish Online. Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 11, 193–217. [Google Scholar]