Abstract

In the field of cardiac electrophysiology, modeling has played a central role for many decades. However, even though the effort is well-established, it has recently seen a rapid and sustained evolution in the complexity and predictive power of the models being created. In particular, new approaches to modeling have allowed the tracking of parallel and interconnected processes that span from the nanometers and femtoseconds that determine ion channel gating to the centimeters and minutes needed to describe an arrhythmia. The connection between scales has brought unprecedented insight into cardiac arrhythmia mechanisms and drug therapies. This review focuses on the generation of these models from first principles, generation of detailed models to describe ion channel kinetics, algorithms to create and numerically solve kinetic models, and new approaches toward data gathering that parameterize these models. While we focus on application of these models for cardiac arrhythmia, these concepts are widely applicable to model the physiology and pathophysiology of any excitable cell.

INTRODUCTION

While computational modeling of ion channels can trace its roots back to the seminal work of Hodgkin and Huxley (HH) and the squid giant axon in 1952,1 the field has recently seen a rapid and sustained evolution in the complexity and power of such models to understand emergent physiology. Our ability to model increasingly complex physiology has allowed for a better understanding of mechanisms of disease, as well as hypothesis generation for the design and testing of new electrophysiology experiments. This review will focus on new methods to model ion channel electrophysiology and the application of these models to understand cardiac arrhythmia mechanisms and drug therapies. However, the concepts described herein are widely applicable, specifically within neuroscience and other diseases of excitability. We first start with a brief review of the cardiac action potential (AP).

Generation of the cardiac action potential

The generation of the cardiac action potential (AP), the electrical activity of single cardiac myocytes, requires an exquisitely timed series of ion channel, pumps and exchanger activation working in concert to generate a well-defined electrical impulse. Across the entire heart, these single cell electrical impulses coalesce to form the heartbeat by translating electrical signals into mechanical contraction via intracellular calcium and mechanical proteins of the heart, a process termed excitation–contraction coupling.

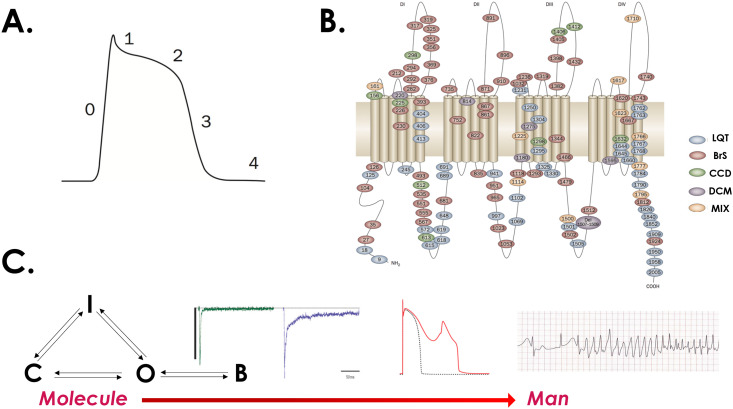

While a detailed discussion of the cardiac AP is beyond the scope of this review (see Ref. 2) in brief, the ventricular AP is broken up into five phases [Fig. 1(a)]. The upstroke of the AP is generated by a rapid inward (depolarizing) Na+ current, termed phase 0. Phase 1 is marked by Na+ channels closing, and a transient outward current (Ito), which is responsible for the characteristic “notch” of the AP. In phase 2, a series of Ca2+ channels “open” while K+ channels continue to efflux representing an electrically “neutral” balance that underlies the “plateau” phase of the cardiac AP. As voltage gated Ca2+ channels close and slowed K+ rectifier channels open, the cell begins to repolarize back to resting membrane potential, which marks phase 3. Finally, phase 4 is marked by K+ channel permeability, keeping the cell at a resting membrane potential of ∼−85 mV. Notably, these cells are not autonomous, but rather are electrically exited once an impulse is generated from the heart's conduction system, originating from sinoatrial nodal cells.

FIG. 1.

The generation of the cardiac action potential in both health and disease. (a) The cardiac ventricular action potential is divided into five phases, with the rapid influx of Na+ into the cell leading to the fast upstroke of the AP (phase 0). (b) Numerous diseases have been linked to the cardiac Na+ channel including the long QT3, Brugada, and dilated cardiomyopathy. (c) In the prototypical LQT3 mutation, some channels fail to inactivate and enter a bursting regime (denoted B). This leads to a small, sustained inward Na+ current (purple trace). At the single cell level, this manifests as AP prolongation (red waveform, depicting an early afterdepolarization). At the organ level, this can lead to the deadly rhythm disturbance known as polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Adapted with permission from Ruan et al., Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 6, 337–348. 2009, Copyright 2009 Nature Publishing.3

A small ion channel perturbation can lead to deadly rhythm disturbances

The electrical conduction system of the heart, while complex, remains highly robust, allowing for approximately 100 000 heart beats a day. For the vast majority of heart beats, the system “works” as intended. However, small perturbations in the function of even a single ion channel type can lead to deadly rhythm disturbances (so-called channelopathies). Numerous disease phenotypes have been linked to the cardiac Na+ channel, for example, including the long QT syndrome (LQT3), Brugada syndrome, and dilated cardiomyopathy3 [Fig. 1(b)]. In LQT3, the Na+ channel fails to inactivate completely during phases 2 and 3 of the cardiac action potential, leading to a small sustained inward current and AP prolongation. Summed over the entire heart, cellular AP prolongation manifests as a prolonged QT interval on the body surface ECG (a marker of impaired repolarization), which can lead to ventricular arrhythmias including polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death [Fig. 1(c)]. Understanding which patients and in which specific situations these rhythm disturbances manifest, and further rational design of drug therapies that target the channelopathy has been quite challenging.

In practice, tracking markers of arrhythmia, which are diseases in space and time, and developing a comprehensive understanding how a disturbance at the ion channel level (scale of angstroms) manifests in cells (nanometer scale), tissues and organ level (centimeters) is nearly impossible. However, these highly nonlinear, emergent dynamics that manifest due to electrotonic coupling of thousands of cells are well suited for a computational modeling approach. The power of in silico modeling is that the researcher is able to track markers of arrhythmia and test a vast parameter space of virtual drugs and conditions that would be impossible to reproduce experimentally. Once a positive result is found computationally, it can then be validated experimentally; this approach provides for a bidirectional feedback to refine the model.

MODELING OF THE ACTION POTENTIAL

General structure of cellular model

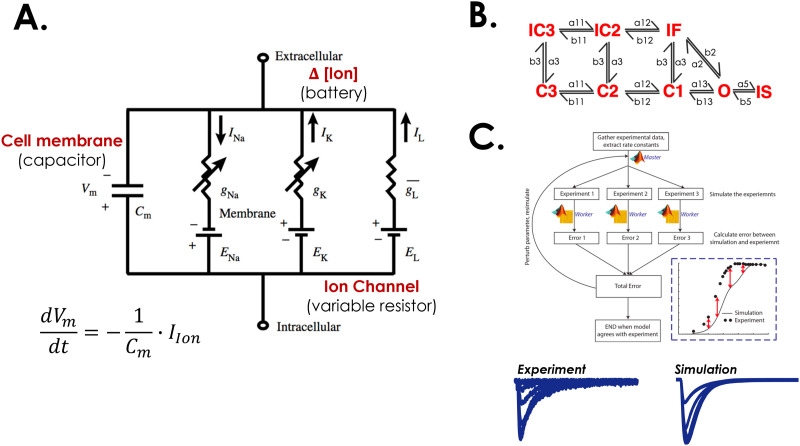

Action potential models that describe the flow of ions both across the cellular membrane and within subcellular compartments can be represented as a circuit diagram, as depicted in Fig. 2(a). Shown are sample Na+, K, and leakage currents as well as the capacitive effect of the membrane, which is impermeable to charged ions. Thus, change in Vm across the membrane can be described by the following equation:

where Cm is the membrane capacitance (μF/cm2), and Iion is the total membrane current (μA/cm2). Cell capacitance per unit area of membrane and current densities are used to calculate Vm, which allows for normalization of variability in cell size.2 In the above equation, Iion is the sum of all membrane currents in the Hodgkin–Huxley model; as noted in the figure for this particular model, Iion is the sum of INa (a depolarizing current), IK (repolarizing current), and ILeak, a leakage current. For INa and IK, the driving force is generated by the transmembrane concentration gradients, and its magnitude is the difference between Vm and the equilibrium potential, calculated by the Nernst equation.

FIG. 2.

Creation and numerical optimization of quantitative descriptions of ion channels. (a) A simple circuit diagram representing the cell membrane (capacitor), and three ion channels (gNa, gK, and gL) representing variable resistors. (b) A prototypical eight-state Na+ channel Markov model with three closed states, one open state, two closed inactivated states and a fast and slow inactivated state arising from the open state. (c) To fit the rate constants depicted in (b), numerical optimization techniques are employed to simulate an electrophysiologic experiment. The simulated results are compared to the experiment, and the rate constants are adjusted to minimize the objective function (the error between simulation and experiment. Adapted with permission from Y. Rudy and J. R. Silva, Q. Rev. Biophys. 39(1), 57–116 (2006). Copyright 2006 by Cambridge University Press. In addition, Adapted with permission from Moreno et al., PLoS One 11(3), e0150761 (2016). Copyright 2016 Authors, licensed under a Create Commons Attribution (CC BY) License.2,24

Once the driving force is known, the current can be computed using Ohm's law, for example, for INa:

In the Hodgkin Huxley (HH) formalism, the conductance for each current is computed as a function of the open probability of a series of hypothetical gates and the maximum conductance of the membrane for each ion species. This allowed for voltage and time dependence of the conductance. Each gate can transit from a closed to open and vice versa, at a rate that is independent from the position of the other gates. An ion can only pass through the gate in the open position. Beginning with the Luo–Rudy dynamic model, the consequences of multiple ionic species coming through the L-type Ca2+ channel were accounted for with the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz (GHK) equation instead of the Ohmic formulation used for INa.4 The use of the constant field equation followed work by Campbell et al. looking at the reversal potential of Ca2+ channel.5 Interestingly, consistently accounting for the GHK equation in fitting the activation curve recently improved the behavior of the updated ToR-ORd model.6

For example, for INa, Na+ current activation can be modeled by a series of three identical activation gates (m) that moved from closed to open once the membrane, Vm, is depolarized. When m = 0, the gate is closed, and open when m = 1. The time-dependent change in m can be described by the following differential equation:

where m and (1 − m) are the gate open and closed probabilities, t is time (ms), and α and β are the voltage dependent open d and closing rates (ms−1). Given the assumption of independence, the probability that all three activation gates are open is m3. As the membrane depolarizes, all three gates open rapidly, allowing for the flow of Na+ ions into the cell, which provides the depolarizing current that underlies the AP upstroke. In similar fashion to the activation gate, m, the HH formalism includes an inactivation gate, h, which is fully open at hyperpolarized potentials. Conversely, when the membrane is depolarized, the inactivation gate closes, which causes a monoexponential decrease observed in INa. Again, given the gating independence of the HH formalism, this is represented by

where gNa,Max is the maximum conductance. The governing equations for IK and ILeak are derived in similar fashion. These seemingly simple equations and compact formalism faithfully reproduced the axonal AP morphology under a wide variety of conditions and continues to serve as the basis significantly more complex, cellular models across a wide variety of species. The reader is referred to Refs. 2 and 7 for a more detailed review.

Numerical solution of action potential model equations

Historically, as computational models of action potentials gained detail and the duration of time domains that they were simulated over increased, methods were developed to improve the efficiency of their integration, given limited computational resources, e.g., the equations for the Luo–Rudy phase I model were integrated on an Apple IIe personal computer.4 The equations above describe a set of ordinary differential equations that are integrated simultaneously. The most intuitive approach to integrate them is to measure the derivative at the current point and step forward in time at the rate suggest by the derivative, according to Euler's method:

where h is the time interval or time step and we have N coupled first order differential equations with the general form with i = 0,1,…,N.

If the derivative does not change significantly over the time interval being stepped over, the equations will be accurately integrated. In addition, each of the gating equations, e.g., for m, h, etc., can be integrated analytically. An example is below for the m-gate:

where and . Inspection of the analytical solution provides the insight that at time 0 the exponential term is equal to 1, thus . At time infinity, the exponential term is 0, so .

Thus, the time it takes to approach is dependent on the time constant in the exponential term, .

With the analytical solutions for the gate equations in hand, only the voltage equation needs to be integrated “numerically.” Rush and Larsen used the analytical solutions of the gates with Euler integration of the voltage equation to efficiently solve action potential models.8,9 The drawback of this approach is that error associated with a given time step is not calculated during the solution of these equations. Thus, if the time step is too large and the derivative changes significantly during step, the solution is not accurate and can become unstable. To address this limitation, they suggested a small time step during the action potential upstroke, an intermediate step during the action potential and a longer step when the model was repolarized. A framework for integrating Markov models into the Rush Larsen scheme was implemented by Clancy et al. that used the unconditionally stable backward Euler method to solve just for the Markov model equations and iteratively reduce the error just for these equations.10 This hybrid approach can be quite efficient but estimating error for just part of the solution can be problematic.

The highly efficient Rush–Larsen approach is still used for three-dimensional whole heart simulations that contain millions of excitable elements. However, Computational power has become more available and easy-to-use solvers for ordinary differential equations are readily accessible. Thus, many investigators have used these solvers, including the versatile Runge–Kutta solvers, which estimate derivatives across the interval being stepped over to produce a more accurate step over a longer interval.11 In Matlab, this approach is represented by the highly used ode45 function. These methods also have the advantage of estimating the error of the step by producing two solutions, one of higher accuracy and one of lower accuracy. A significant difference between the higher lower accuracy solutions indicates that the magnitude of the time step should be reduced, allowing the algorithm to dynamically step through the solution. Given the wide availability of these improved solvers in Matlab, Python, and specialized packages, such as CVODE,12,13 it is highly recommended they be used if possible.

A second consideration is the intrinsic stiffness of the equations that are being solved. For solving differential equations, stiffness has been described by Cleve Moler as follows. “A problem is stiff if the solution being sought varies slowly, but there are nearby solutions that vary rapidly, so the numerical method must take small steps to obtain satisfactory results.”14 Unfortunately, the equations for the Na+ current in most action potential models introduce quite a bit of stiffness into the system. Thus, many models are more efficiently solved by implicit models where the derivative is evaluated at the time point being stepped to, e.g.,

Algorithms that use this approach, including ode15s in Matlab rely on a linearization of the set of differential equations that uses a Jacobian. The Jacobian can be found by finite differences automatically, but the solution is found much more effectively if the Jacobian or at least its dependencies are specified in advance. This increase in efficiency comes from the fact finite differences requires many sequential calculations of expensive exponential equations that are used to describe the voltage dependence of the gating variables. Still, it can be challenging to specify the Jacobian and sometimes the resulting solution contains singularities. Fortunately, recent open-source methods15 have been described to greatly facilitate this process.

In most contemporary publications, action potential models are integrated with the numerical solvers described. However, using these solvers still pose a challenge for the optimization of Markov type models where there are many parameters and the objective function has many local minima, requiring global optimization methods. The many sets of parameters required, requires a more efficient method to integrate the equations. Efficient integration can be accomplished at a given potential by solving the matrix exponential. In this case,

where and y are the states of the Markov model while Q contains the rates that relate state occupancy to the derivative, known as a “Q-matrix.”16 Since most protocols used to characterize ionic current kinetics are composed of step functions, this approach is highly efficient because the solution of the matrix exponential only needs to be performed once for every step. In our experience, it also tends to be more stable, allowing the optimization algorithm to explore the parameter space without encountering numerical instability as often.17 While this approach tends to shine most brightly when simulating pulse protocols, it can also be used to integrate Markov models within the Rush–Larsen method for action potential simulations,18 replacing the backward Euler approach used previously.

MARKOV MODELS OF ION CHANNELS

Differentiating a Markov model from the Hodgkin–Huxley formalism

While the HH formalism allowed for an initial conceptual framework for the ionic basis of the action potential, it soon became clear that models with explicit representations of single ion channel states were required. For example, in the HH formalism, gating parameters did not represent specific kinetic states of ion channels. Second, the assumption of independent gating transitions was found to be inaccurate. Notably, for example, inactivation of the Na+ channel has a greater probability of occurring when the channel is open, and therefore depends on activation. As such, the equation m3 * h to compute conductance is inaccurate. Markov formalism allows for the representation of the dependence of a given transition on the current occupancy of different states of the channel, but not on previous behavior.2

Mathematically, we can describe a simple two-state Markov model, which includes an open, conducting state, as well as a closed state,

where O and C are the probabilities that the channel is residing in the open and closed state, respectively; α and β are the voltage dependent transition rates (ms−1) between these states.

Developing the structure of a Markov model

Initially, the generation of a Markov model describing channel gating relied on operator “intuition” to create a Markov model structure that is informed by experimental data that seeks to understand the various kinetic states of the channel. As an example, to understand the gating mechanisms leading to pathologic behavior of a long QT variant, ΔKPQ, Clancy et al.10 developed a computational model of the Na+ channel that was represented by a series of six states [three closed states, loosely representing the four voltage sensing domains (VSD)], a conducting open state, and a fast and slow inactivating state. Each state was connected by a series of voltage dependent rate constants, drawn from experimental data. The model parameters were then “hand tuned” to fit the ensemble average of a Na+ channel current that recapitulated key electrophysiologic parameters including steady state activation, inactivation, recovery from inactivation, and channel mean open time. The model was then expanded to include unique gating aspects of ΔKPQ. Experiments in single ΔKPQ channels revealed a population of channels that would fail to inactivate and would exhibit “bursting” behavior.10,19 To recapitulate this behavior, the WT Na+ channel model was expanded to include a bursting regime that would not allow the channel to inactivate. As such, a series of bursting states were connected to the closed and open states. These transitions were voltage independent and represented the probability of the Na+ channel entering into a noninactivating, bursting regime.

As more data on the complex behavior of inactivation and recovery from inactivation became available, the model was expanded by Moreno et al.20 to include additional inactivated states from the closed position. Thus, the WT Na+ channel model now included three closed states, a conducting open state, two closed inactivated states, as well as a fast and slow inactivated state arising from the open state [Fig. 2(b)]. This additional model structure allowed for more complex, time dependent protocols to be recapitulated, namely, recovery from use-dependent block (a biexponential phenomenon), whereby the channel transits to an absorbing inactivated regime after a series of repetitive pulses. In this work, the WT Na+ channel model was then coupled to two separate “drug-bound” models that sought to describe the complex kinetics of local anesthetic (class I) antiarrhythmic drugs at both the cellular and tissue level.

It is important to consider a few key points about Markov model development to this point. The model structure was determined by the operator based on their understanding of the Na+ channel structure, and kinetic transitions observed experimentally. For example, it is known that there are four voltage sensing domains (VSD) in the cardiac Na channel, and that each one must activate for the channel to open and allow for current flow. One would thus expect four closed states in the model, with each successive transition (C4 → C3 → C2 → C1) to represent the movement of one VSD to the activated position. Yet, the models only contain three closed states; this is because the addition of a fourth closed state did not significantly improve the model fits, and thus one of the closed states (e.g., C3) likely represents two kinetic transitions in the Na+ channel activation process. Up to this point, while the Markov model structure was informed by experimental data and putative structure of the ion channel, there was not necessarily a 1:1 association between channel conformational structure and Markov model state.21 Most importantly, the model should only be as complex as necessary to fit the given experimental data.

Second, parameter optimization in the first-generation models were hand tuned, e.g., the researcher would modify the rate constants and visually assess for fidelity of fit of the model to the experimental data. This approach had significant limitations; first, the process was onerous, and only the more simple models with few protocols could be fit in this fashion. Second, the fit was operator dependent, and required a great deal of intuition on the part of the researcher to understand how a particular change in rate constant might have both intended and unintended consequences for multiple protocols. As model complexity has increased (e.g., 42 states in the most recent Moreno et al. model22), so too has computational power, and the field has moved away from hand tuning, toward sophisticated numerical optimization techniques. In this fashion, the models have become operator independent. Simply, a series of experimental protocols that the operator wishes to fit are simulated computationally. The error between the experimental data and simulated results is then compared and ultimately minimized (the objective function) [Fig. 2(c)]. This has allowed for a much more robust search of the wide parameter space necessary to fit the myriad experimental data now available (for detailed reviews, see Refs. 23 and 24) Of note, with increasing data, there is potential for over-fitting, as well as discordant datasets if data were gathered at different times, and under slightly different experimental conditions. Clerx et al. provide an important study25 that compares four different methods of ion channel fitting, with a short, rapidly fluctuating protocol providing superiority in accuracy of predictions and computational efficiency.

Structural correlates in Markov model development

Connecting molecular structure to channel function

As more data have emerged, revealing detailed structures of channels and their associated functional consequences, there has been increased interest in connecting Markov models to channel features. One of the initial attempts to accomplish this connection was with the slow delayed rectifier K+ current, IKs.26 Extensive work by the Aldrich group had shown that the four voltage sensing domains of prototypical Shaker K+ channels activate in multiple steps27–29 accounting for sigmoidal activation that is also observed in IKs activation. Modeling the details of voltage domain activation, in terms of multiple steps taken, revealed that the slow first step held channels in reserve that then became available at rapid heart rates as they exited the reserve states and entered a domain where they could rapidly activate. Subsequent voltage clamp fluorometry data, directly observing the activation of the voltage sensing domains30–32 and single channel measurements,33–36 have been used to update the structure of these models,37,38 demonstrating a highly productive interplay between modeling and experiment.

Much additional work has been done to connect the molecular dynamics methods that are used to study the nanoscale movements of proteins to the Markov type models used for cardiac electrophysiology. One of the first, this study modeled the interaction of charged amino acids in the voltage sensing domains of the IKs alpha subunit, KCNQ1 along a simulated trajectory through the membrane.39 The associated free energy for each putative state was estimated using implicit methods that average the membrane effects as a continuum. The emerging landscape was then used to simulate activation of the IKs channel and connect it to the cell and tissue level electrophysiology. The challenge in applying this approach more widely has been appropriately sampling the energy landscape that defines voltage sensing domain activation and much work needs to be done to accurately predict how subtle changes in the structure of a channel will translate to its function. Indeed, even supercomputer simulations of the well-defined Shaker K+ channel activation only yielded a single trajectory that was stitched together.40 Without accurate simulation of the voltage sensing domain, it is difficult to connect molecular dynamics to the gating variables used in action potential models. Nevertheless, methods to generate Markov type models from molecular dynamics simulation of proteins have been developed,41–44 and we expect that with increases in computational power, perhaps with new developments in cloud45 quantum computing and the use of artificial intelligence for structure prediction,46,47 these scales will be eventually connected.

While simulation of the voltage-sensing domain has been exceptionally challenging, there has been significant progress in terms of simulating drug interactions. These efforts include simulation of anti-arrhythmic drug binding and recent work suggested that multiple class I molecules may be able to enter the pore of the cardiac Na+ channel.48 Connecting the details of this binding to the potential for arrhythmia to be initiated and sustained may eventually lead to improved therapies. On the other end of the spectrum, the binding of pro-arrhythmic drug block to hERG K+ channels has also been modeled from the molecular level.49 The aim of these efforts is to eventually be able to predict pro-arrhythmic side effects before significant effort is expended in developing a drug. Conversely, successfully predicting that a drug will not be pro-arrhythmic could facilitate the development of potentially beneficial molecules that would otherwise not be pursued as therapies.

Unbiased searching of model structures

This process of model development to this point required a comprehensive understanding and intuition of the underlying physiology to develop a Markov model structure. This process necessarily carried an implicit bias on the part of the researcher, who hypothesized how the model structure should be connected based on an analysis of the experimental data. The newest generation models have removed this barrier. In 2009, Menon described a numerical optimization technique that allowed for the optimization routine to alter the topology of the ion channel.50 In 2021 Mangold et al.51 further refined this approach by developing a systematic method to identify all possible Markov model topologies for a given number of states (e.g., all possible six state models), with a single open state. Each model is then optimized to a set of experimental data and the best model fit and structure is elucidated. This approach thus allows for model creation even when the structure of the model is not specified a priori!

We have discussed two extremes thus far: (1) model structure was either determined a priori from the researcher based on macroscopic ion current kinetics and single channel behavior, or (2) determined purely numerically from an optimization algorithm that may have little to do with the actual ion channel structure. In reality, a third hybrid approach has also been employed which marries ion channel kinetic data with simultaneous molecular movements obtained through a technique called voltage-clamp fluorimetry.52,53 For example, to understand the molecular movements of the Na+ channel, a fluorophore is connected to a specific domain (e.g., DI–DIV of the Na+ channel), which is then simultaneously tracked across a series of kinetic protocols. In this way, key kinetic transitions of the channel can be correlated with the precise molecular movement of a specific domain. We harnessed this technique to answer a clinical question: why, for certain LQT3 mutations is mexiletine, a class IB antiarrhythmic drug effective at suppressing malignant arrhythmia, while for others, it shows virtually no efficacy54? We used the VCF technique to further clarify the role of the DIII-VSD in Na+ channel inactivation and its interaction with class I antiarrhythmic drug efficacy. We then built a model of the Na+ channel that incorporated the DIII-VSD molecular movement and then used the model to rationally design a precision targeted therapeutic that we hypothesized would “boost” mexiletine.

In sum, over the past 30 years, Markov model development has transitioned from a painstaking process that required a strong computational expertise as well as biased knowledge of model structure, to a much more robust, near fully automated and widely available approach that can either incorporate known molecular movements or use the computational algorithm to suggest model structures that may be novel and hypothesis generating for experimental testing!

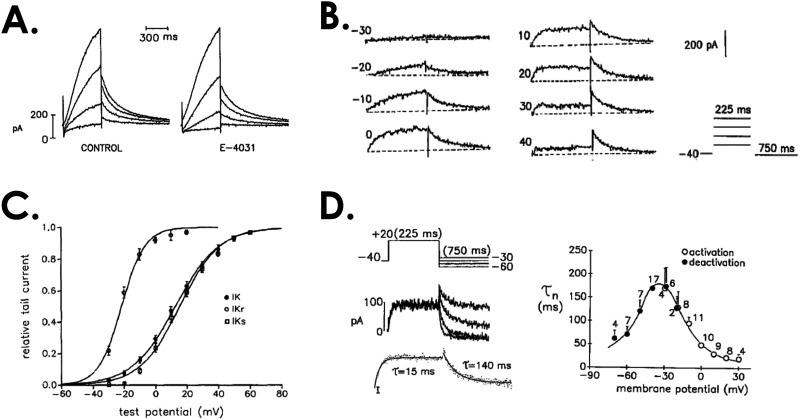

GATHERING DATA TO PARAMETERIZE THE MODELS

The time and membrane voltage dependence of ion channel opening have been traditionally characterized by applying a series of square pulses in a carefully designed series. For example, a set of steps from a negative (∼−100 mV) to positive membrane potentials (between −40 and +40 mV) can be used to assess the steady state dependence of K+ channel opening on membrane potential. The rate of rise provides the activation time constant. Figure 3 shows historical recordings of the fast and slow components of the delayed rectifier K+ currents, obtained as specific blockers became available.55 These pulse protocols can be further modified to assess the voltage dependence of the rate of deactivation [Fig. 3(d)], by stepping to different negative potentials after a depolarizing pulse. Inactivation can be measured by stepping to progressively depolarized potentials to cause inactivation and then applying a test pulse to assess the fraction of channels that have entered this state. Additional information from single channel recordings can be used to assess the mean open time, which informs the probability of opening after a depolarizing pulse.56

FIG. 3.

Traditional protocols that are used to characterize ion channel time- and voltage-dependent kinetics. (a) K+ currents that arise from a series of steps to depolarized potentials from a guinea pig ventricular myocyte. A component of the overall current (left) is blocked by the molecule E-4031 (right). (b) Subtraction of the E-4031 blocked current from control yields the difference current. In this case, the rapid component of the delayed rectifier K+ channel, IKr. Shown is the response to steps at different potentials according to the protocol shown at the bottom right. (c) The relationship between the steady state conductance and the membrane potential is calculated by dividing the peak current magnitude by the driving force, e.g., (Vm − EK) where Vm is the membrane potential and EK is the reversal potential for K+, providing n∞ for the model. (d) The time constant τn is found by fitting the activation at depolarized potentials as in (b), and hyperpolarizing potentials after activation according to the protocol at the top left of the panel which steps to different negative potentials. Adapted with permission from Sanguinetti et al., J. Gen. Physiol. 96(1), 195–215 (1990). Copyright 1990 by Rockefeller University Press.55

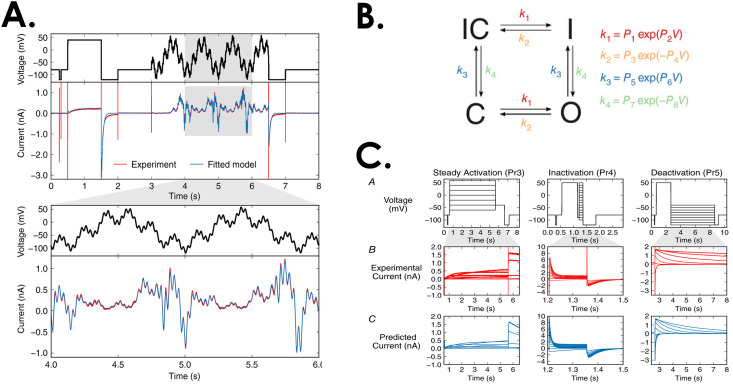

However, these traditional protocols have some limitations, including the time and number of cells needed to complete them. They also may not be ideally suited to efficiently optimize a channel model. Recently, the use of a series of sine waves to interrogate channel function instead of square pulses has been proposed, they may be more effective when used to identify model rate parameters.57 Figure 4 shows the sine waves used to parameterize a model of IKr and the model ability to predict ionic currents elicited by traditional pulse protocols [Fig. 4(c)]. One significant advantage to this approach is that the protocols can be much shorter, allowing full characterization of the channel kinetics in a single cell (as opposed to applying the different pulse protocols from above to different cells).

FIG. 4.

Sinusoidal waveforms can be used to parameterize Markov models. (a) The waveform at the top is used to evoke the current below and this is fit to parameters for a four-state Markov model. (b) The Markov model that was fit to the parameters includes four states with forward and backward rates between each of the states. The rates are described by exponential equations. (c) A test of the model evaluated whether it could predict ionic currents from traditional square pulse protocols, and it was able to do so successfully. Adapted with permission from Beattie et al., J. Physiol. 596(10), 1813–1828 (2018). Copyright 2018 by The Physiological Society.57

Other experimental approaches attempt to characterize multiple currents within the same myocyte, which provides key data that shows how different conductances are correlated with one another. The “onion peeling” technique was developed where a series of specific blockers to serially characterize the Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ionic and Na+/Ca2+ exchange currents within a single myocyte.58,59 A second recent approach used a genetic optimization algorithm to optimize a protocol to rapidly assess the conductances of multiple currents in the same cell, allowing for rapid identification of currents affected by pro-arrhythmic drugs.60 As many groups are currently investigating the consequences of variability between patients and from myocyte to myocyte,61–63 these experimental approaches have the potential to inform the bounds of conductance magnitudes as well as correlations between them. For example, emerging data suggest that Na+ and K+ channels traffic to the membrane together.64 Thus, one might hypothesize that an increased Na+ channel conductance would correlate with an increased K+ channel conductance.

A second challenge with data collection is the limited number of myocytes available from large animal models or healthy human hearts.65 As it is impractical to thoroughly characterize every kinetic parameter from every ion channel current in every model system, multiple groups have proposed using regression approaches to connect two data sets. Using these methods, the idea would be to record currents in readily available myocytes and then use these algorithms in conjunction with action potential models to extrapolate the effects on the human myocytes. Thus, data from mouse myocytes or myocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells could be used to predict the consequences of a drug intervention or variant on the human myocyte action potential.62,66,67

MODELS: THE NEXT GENERATION

Markov models have proven highly useful in describing detailed behavior of ion channels, but they are not without limitations including challenges with optimization, parameter identifiability, and equation stiffness. New work has investigated whether other models that are perhaps more easily optimized might prove superior in some cases. One effort used a neural network to simulate ion channel behavior. This approach is attractive given the highly developed methods to find the weights needed to relate the inputs to a neural network to the predicted output. In this case, a time series of voltage steps is presented to the neural network and the expected ionic current is predicted.68

Another new approach employs automata, which are described as discrete dynamic systems that respond only to local inputs. Since the automata only respond to local inputs, in many cases they can simulate very complex behavior in a computationally efficient manner. Examples include the simulation of protein conformations and dynamics as well as Ca+ dynamics and ionic currents within a neuronal membrane.69–71 Given that these models are particularly efficient in representing the interactions between different elements of a model, they are likely to be useful in discovering the emergent behavior of a multiscale system. The heart represents such a system where molecular level defects, drug interactions and post-translational modifications propagate to the whole organism to cause or prevent sudden cardiac death.

CONCLUSIONS

The field of computational modeling to understand cardiac myocyte electrophysiology has a rich history. As detailed in this review, there have been seminal discoveries in understanding fundamental mechanisms that determine ion channel kinetics, and how derangement can lead to disease. Despite over 70 years of research, the continued advancement of computational power and numerical methods, married with fascinating experimental setups that can tease apart molecular mechanisms of ion channel biology ensure that future discoveries will have a profound impact on our understanding of health and disease.

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

Jonathan Moreno: Conceptualization (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Jonathan Silva: Conceptualization (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Resources (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Hodgkin A. L. and Huxley A. F., “ A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve,” J. Physiol. 117(4), 500–544 (1952). 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudy Y. and Silva J. R., “ Computational biology in the study of cardiac ion channels and cell electrophysiology,” Q. Rev. Biophys. 39(1), 57–116 (2006). 10.1017/S0033583506004227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruan Y., Liu N., and Priori S. G., “ Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias,” Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 6, 337–348 (2009). 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luo C. H. and Rudy Y., “ A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. I. Simulations of ionic currents and concentration changes,” Circ. Res. 74(6), 1071–1096 (1994). 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell D. L. et al. , “ Reversal potential of the calcium current in bull-frog atrial myocytes,” J. Physiol. 403, 267–286 (1988). 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tomek J. et al. , “ Development, calibration, and validation of a novel human ventricular myocyte model in health, disease, and drug block,” Elife 8, e48890 (2019). 10.7554/eLife.48890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moreno J. D. and Clancy C., “ Simulation of cardiac action potentials,” in Heart Rate and Rhythm, edited by Tripathi S. ( Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marsh M. E., Ziaratgahi S. T., and Spiteri R. J., “ The secrets to the success of the Rush–Larsen method and its generalizations,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59(9), 2506–2515 (2012). 10.1109/TBME.2012.2205575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rush S. and Larsen H., “ A practical algorithm for solving dynamic membrane equations,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 25(4), 389–392 (1978). 10.1109/TBME.1978.326270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clancy C. E. and Rudy Y., “ Linking a genetic defect to its cellular phenotype in a cardiac arrhythmia,” Nature 400(6744), 566–569 (1999). 10.1038/23034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Press W. H., Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed. ( Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2007), Vol. xxi, p. 1235. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hindmarsh A. et al. , “ SUNDIALS: Suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers,” ACM Trans. Math. Software 31(3), 363–396 (2005). 10.1145/1089014.1089020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardner D. et al. , “ Enabling new flexibility in the SUNDIALS suite of nonlinear and differential/algebraic equation solvers,” ACM Trans. Math. Software 48(3), 1–24 (2022). 10.1145/3539801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moler C. B., Numerical Computing with MATLAB ( Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Philadelphia, 2004), Vol. XI, p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hendrix M., Clerx M., and AU T., “ cellmlmanip and chaste_codegen: Automatic CellML to C++ code generation with fixes for singularities and automatically generated Jacobians,” Wellcome Open Res. 6, 261 (2022). 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17206.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colquhoun D. and Hawkes A. G., “ A Q-Matrix cookbook,” in Single-Channel Recording, edited by Sakmann B. and Neher E. ( Springer, Boston, 1995), pp. 589–633. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teed Z. R. and Silva J. R., “ A computationally efficient algorithm for fitting ion channel parameters.,” MethodsX 3, 577–588 (2016). 10.1016/j.mex.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stary T. and Biktashev V. N., “ Exponential integrators for a Markov chain model of the fast sodium channel of cardiomyocytes,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62(4), 1070–1076 (2015). 10.1109/TBME.2014.2366466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Q. et al. , “ SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome,” Cell 80, 805–811 (1995). 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moreno J. D. et al. , “ A computational model to predict the effects of class I anti-arrhythmic drugs on ventricular rhythms,” Sci. Transl. Med. 3(98), 98ra83 (2011). 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silva J. R., “ How to connect cardiac excitation to the atomic interactions of ion channels,” Biophys. J. 114(2), 259–266 (2018). 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moreno J. D. et al. , “ A molecularly detailed NaV1.5 model reveals a new class I antiarrhythmic drug target,” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.: Basic Transl. Sci. 4, 736 (2019). 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangold K. E. et al. , “ Mechanisms and models of cardiac sodium channel inactivation,” Channels 11(6), 517–533 (2017). 10.1080/19336950.2017.1369637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moreno J. D., Lewis T. J., and Clancy C. E., “ Parameterization for in-silico modeling of ion channel interactions with drugs,” PLoS One 11(3), e0150761 (2016). 10.1371/journal.pone.0150761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clerx M. et al. , “ Four ways to fit an ion channel model,” Biophys. J. 117(12), 2420–2437 (2019). 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silva J. and Rudy Y., “ Subunit interaction determines IKs participation in cardiac repolarization and repolarization reserve,” Circulation 112(10), 1384–1391 (2005). 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zagotta W. N., Hoshi T., and Aldrich R. W., “ Shaker potassium channel gating. III. Evaluation of kinetic models for activation,” J. Gen. Physiol. 103(2), 321–362 (1994). 10.1085/jgp.103.2.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zagotta W. N. et al. , “ Shaker potassium channel gating. II. Transitions in the activation pathway,” J. Gen. Physiol. 103(2), 279–319 (1994). 10.1085/jgp.103.2.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoshi T., Zagotta W. N., and Aldrich R. W., “ Shaker potassium channel gating. I. Transitions near the open state,” J. Gen. Physiol. 103(2), 249–278 (1994). 10.1085/jgp.103.2.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rudokas M. W. et al. , “ The Xenopus oocyte cut-open vaseline gap voltage-clamp technique with fluorometry,” J. Vis. Exp. 11(85), 51040 (2014). 10.3791/51040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Osteen J. D. et al. , “ Allosteric gating mechanism underlies the flexible gating of KCNQ1 potassium channels,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109(18), 7103–7108 (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1201582109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osteen J. D. et al. , “ KCNE1 alters the voltage sensor movements necessary to open the KCNQ1 channel gate,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107(52), 22710–22715 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1016300108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eldstrom J. et al. , “ ML277 regulates KCNQ1 single-channel amplitudes and kinetics, modified by voltage sensor state,” J. Gen. Physiol. 153(12), e202112969 (2021). 10.1085/jgp.202112969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson E., Eldstrom J., and Fedida D., “ Single channel kinetic analysis of the cAMP effect on I(Ks) mutants, S209F and S27D/S92D.,” Channels 12(1), 276–283 (2018). 10.1080/19336950.2018.1499369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Werry D. et al. , “ Single-channel basis for the slow activation of the repolarizing cardiac potassium current, I(Ks),” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110(11), E996–1005 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1214875110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Westhoff M. et al. , “ I(Ks) ion-channel pore conductance can result from individual voltage sensor movements,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116(16), 7879–7888 (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1811623116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fedida D., “ Modeling the hidden pathways of IKs channel activation,” Biophys. J. 115(1), 1–2 (2018). 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramasubramanian S. and Rudy Y., “ The structural basis of IKs ion-channel activation: Mechanistic insights from molecular simulations,” Biophys. J. 114(11), 2584–2594 (2018). 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silva J. R. et al. , “ A multiscale model linking ion-channel molecular dynamics and electrostatics to the cardiac action potential,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106(27), 11102–11106 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0904505106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jensen M. O. et al. , “ Mechanism of voltage gating in potassium channels,” Science 336(6078), 229–233 (2012). 10.1126/science.1216533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bowman G. R., “ Improved coarse-graining of Markov state models via explicit consideration of statistical uncertainty.,” J. Chem. Phys. 137(13), 134111 (2012). 10.1063/1.4755751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bowman G. R., “ An overview and practical guide to building Markov state models,” Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 797, 7–22 (2014). 10.1007/978-94-007-7606-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bowman G. R. et al. , “ Discovery of multiple hidden allosteric sites by combining Markov state models and experiments,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112(9), 2734–2739 (2015). 10.1073/pnas.1417811112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pande V. S., Beauchamp K., and Bowman G. R., “ Everything you wanted to know about Markov state models but were afraid to ask,” Methods 52(1), 99–105 (2010). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mangold K. E. et al. , “ Creating ion channel kinetic models using cloud computing,” Curr. Protoc. 2(2), e374 (2022). 10.1002/cpz1.374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Varadi M. et al. , “ AlphaFold protein structure database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models,” Nucl. Acids Res. 50(D1), D439–D444 (2022). 10.1093/nar/gkab1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jumper J. et al. , “ Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold,” Nature 596(7873), 583–589 (2021). 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nguyen P. T. et al. , “ Structural basis for antiarrhythmic drug interactions with the human cardiac sodium channel,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116(8), 2945–2954 (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1817446116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang P. C. et al. , “ A computational pipeline to predict cardiotoxicity: From the atom to the rhythm,” Circ. Res. 126, 947 (2020). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Menon V., Spruston N., and Kath W. L., “ A state-mutating genetic algorithm to design ion-channel models,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106(39), 16829–16834 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0903766106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mangold K. E. et al. , “ Identification of structures for ion channel kinetic models,” PLoS Comput. Biol. 17(8), e1008932 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhu W., Varga Z., and Silva J. R., “ Molecular motions that shape the cardiac action potential: Insights from voltage clamp fluorometry,” Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 120(1–3), 3–17 (2016). 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Varga Z. et al. , “ Direct measurement of cardiac Na+ channel conformations reveals molecular pathologies of inherited mutations,” Circ.: Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 8(5), 1228–1239 (2015). 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ruan Y. et al. , “ Gating properties of SCN5A mutations and the response to mexiletine in long-QT syndrome type 3 patients,” Circulation 116(10), 1137–1144 (2007). 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sanguinetti M. C. and Jurkiewicz N. K., “ Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents,” J. Gen. Physiol. 96(1), 195–215 (1990). 10.1085/jgp.96.1.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zou A. et al. , “ Single HERG delayed rectifier K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes,” Am. J. Physiol. 272(3 Pt 2), H1309 (1997). 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.3.H1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beattie K. A. et al. , “ Sinusoidal voltage protocols for rapid characterisation of ion channel kinetics,” J. Physiol. 596(10), 1813–1828 (2018). 10.1113/JP275733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen-Izu Y. et al. , “ From action potential-clamp to 'onion-peeling' technique-recording of ionic currents under physiological conditions,” in Patch Clamp Technique ( Intech Open, 2012), pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Horvath B. et al. , “ Ion current profiles in canine ventricular myocytes obtained by the ‘onion peeling’ technique,” J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 158, 153–162 (2021). 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Clark A. P. et al. , “ An in silico-in vitro pipeline for drug cardiotoxicity screening identifies ionic pro-arrhythmia mechanisms,” Br. J. Pharmacol. 179, 4829 (2022). 10.1111/bph.15915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Britton O. J. et al. , “ Experimentally calibrated population of models predicts and explains intersubject variability in cardiac cellular electrophysiology,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110(23), E2098 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1304382110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gong J. Q. X. and Sobie E. A., “ Population-based mechanistic modeling allows for quantitative predictions of drug responses across cell types,” npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 4, 11 (2018). 10.1038/s41540-018-0047-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ni H. et al. , “ Populations of in silico myocytes and tissues reveal synergy of multiatrial-predominant K(+)-current block in atrial fibrillation,” Br. J. Pharmacol. 177(19), 4497–4515 (2020). 10.1111/bph.15198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ponce-Balbuena D. et al. , “ Cardiac Kir2.1 and NaV1.5 channels traffic together to the sarcolemma to control excitability,” Circ. Res. 122(11), 1501–1516 (2018). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Moreno J. D. et al. , “ Pulsus alternans in cardiogenic shock recapitulated in single cell fluorescence imaging of a patient's cardiomyocyte.,” Circ. Heart Failure 15(2), e008855 (2022). 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.121.008855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aghasafari P. et al. , “ A deep learning algorithm to translate and classify cardiac electrophysiology,” Elife 10, e68335 (2021). 10.7554/eLife.68335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Morotti S. et al. , “ Quantitative cross-species translators of cardiac myocyte electrophysiology: Model training, experimental validation, and applications,” Sci. Adv. 7(47), eabg0927 (2021). 10.1126/sciadv.abg0927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lei C. L. and Mirams G. R., “ Neural network differential equations for ion channel modelling,” Front. Physiol. 12, 708944 (2021). 10.3389/fphys.2021.708944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Khrennikov A. and Yurova E., “ Automaton model of protein: Dynamics of conformational and functional states,” Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 130, 2–14 (2017). 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nguyen V., Mathias R., and Smith G. D., “ A stochastic automata network descriptor for Markov chain models of instantaneously coupled intracellular Ca2+ channels,” Bull. Math. Biol. 67(3), 393–432 (2005). 10.1016/j.bulm.2004.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pezard L. and Lesne A., “ Cellular automata approach of transmembrane ionic currents,” J. Integr. Neurosci. 7(2), 271–286 (2008). 10.1142/S021963520800185X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.