Abstract

Background and Aims

Trait-based frameworks assess plant survival strategies using different approaches. Some frameworks use functional traits to assign species to a priori defined ecological strategies. Others use functional traits as the central element of a species ecophysiological strategy. We compared these two approaches by asking: (1) what is the primary ecological strategy of three dominant co-occurring shrub species from inselbergs based on the CSR scheme, and (2) what main functional traits characterize the ecophysiological strategy of the species based on their use of carbon, water and light?

Methods

We conducted our study on a Colombian inselberg. In this extreme environment with multiple stressors (high temperatures and low resource availability), we expected all species to be stress tolerant (S in the CSR scheme) and have similar ecophysiological strategies. We measured 22 anatomical, morphological and physiological leaf traits.

Key Results

The three species have convergent ecological strategies as measured by CSR (S, Acanthella sprucei; and S/CS, Mandevilla lancifolia and Tabebuia orinocensis) yet divergent resource-use strategies as measured by their functional traits. A. sprucei has the most conservative carbon use, risky water use and a shade-tolerant strategy. M. lancifolia has acquisitive carbon use, safe water use and a shade-tolerant strategy. T. orinocensis has intermediate carbon use, safe water use and a light-demanding strategy. Additionally, stomatal traits that are easy to measure are valuable to describe resource-use strategies because they are highly correlated with two physiological functions that are hard to measure: stomatal conductance and maximum photosynthesis per unit mass.

Conclusions

The two approaches provide complementary information on species strategies. Plant species can co-occur in extreme environments, such as inselbergs, because they exhibit convergent primary ecological strategies but divergent ecophysiological strategies, allowing them to use limiting resources differently.

Keywords: Abiotic filtering, functional diversity, inselbergs, CSR strategy scheme, leaf economic spectrum, limiting similarity, plant functional traits, species co-occurrence

Abstract

Introducción y Objetivos Marcos conceptuales basados en rasgos funcionales (RF) usan diferentes enfoques para evaluar las estrategias de supervivencia de las plantas. Algunos marcos usan RF para asignar a las especies a estrategias ecológicas definidas previamente. Otros marcos usan los RF como el elemento central de la estrategia ecofisiológica de las especies. Nosotras comparamos estos dos enfoques preguntando (1) cuál es la estrategia ecológica de tres especies de arbustos que coocurren en un inselberg, (2) qué rasgos funcionales caracterizan principalmente la estrategia ecofisiológica de las especies con base en su uso de carbono, agua y luz.

Métodos Este estudio fue llevado a cabo en un inselberg colombiano. En este ambiente extremo con múltiples factores estresantes (alta temperatura y baja disponibilidad de recursos), nosotras esperábamos que todas las especies fueron estrés-tolerantes (S en el esquema CSR) y tuvieran rasgos funcionales similares. Medimos 22 rasgos anatómicos, morfológicos y fisiológicos de la hoja.

Resultados clave Encontramos que las tres especies tienen estrategias ecológicas convergentes (S: Acanthella sprucei; S/CS: Mandevilla lancifolia y Tabebuia orinocensis) con estrategias de uso de los recursos divergentes. A. sprucei tiene la estrategia más conservativa de uso del carbono, un uso desmesurado del agua, y tolera la sombra. M. lancifolia tiene una estrategia adquisitiva de uso del carbono, un uso mesurado del agua y tolera la sombra. T. orinocensis tiene un uso intermedio del carbono, un uso mesurado del agua y no tolera la sombra. Adicionalmente, mostramos que rasgos de las estomas fáciles de medir son valiosos para el estudio de las estrategias de las especies porque están altamente correlacionados con rasgos fisiológicas difíciles de medir: la conductancia estomática y la fotosíntesis máxima por masa.

Conclusiones Los dos enfoques proveen información complementaria de las estrategias de las especies. Las especies de plantas pueden co-ocurrir en ambientes extremos como los inselbergs porque exhiben estrategias ecológicas convergentes, pero estrategias ecofisiológicas divergentes que les permiten usar los recursos limitantes de diferente manera.

INTRODUCTION

Plant ecologists have developed various trait-based frameworks to assess plant survival strategies in different environments [e.g. CSR strategy scheme (Grime, 1974) and the global spectrum of plant form and function (Díaz et al., 2016)]. These frameworks use plant functional traits defined as any anatomical, morphological and physiological characteristics that indirectly affect individual fitness (Violle et al., 2007). Some frameworks use functional traits to assign species to primary ecological strategies defined a priori (e.g. CSR strategy scheme; Grime, 1974; Reich, 2014). In contrast, others use functional traits as the central element of the plant ecophysiological strategy (e.g. leaf–height–seed strategy scheme; Westoby, 1998; Reich, 2014). We can understand the survival strategy of plant species by comparing the CSR strategy classification (hereafter, ‘ecological strategy’) with the ecophysiological strategy classification, as a first step towards bridging the two conceptual frameworks (Volaire, 2018). We use Grime’s CSR strategy scheme to classify species ecologically based on their affinity to three contrasting types of environments: stable and productive (characterized by plant competition; C); frequently disturbed (i.e. with factors that periodically destroy biomass; R); and stressful (characterized by factors that limit biomass production; S) (Grime, 1974, 2001). We use a combination of traits that are easy and hard to measure to assess the ecophysiology of species in terms of their carbon-, light- and water-use strategies (hereafter, ecophysiological strategy) (Hodgson et al., 1999; Wright et al., 2004; Li et al., 2015; Díaz et al., 2016).

Extreme environments are ideal for comparing ecological and ecophysiological strategies of species because we have clear expectations for them; co-occurring species are expected to be stress tolerant (Grime, 1977) and to have similar ecophysiological strategies (Weiher et al., 1995, 2011; Bernard-Verdier et al., 2012; Bartoli et al., 2014; Coyle et al., 2014; Breitschwerdt et al., 2018). Under the classic community assembly framework, extreme environments are expected to lead to strong abiotic filtering, dominating other assembly mechanisms, such as dispersal limitation, and limiting similarity (Lortie et al., 2004; Vellend, 2010). Extreme environments are defined as those in which species must deal with multiple environmental factors that limit their capacity to execute major ecological and physiological processes (Carnwath and Nelson, 2017; Fernández-Marín et al., 2020). Moreover, although extreme environments have been studied broadly, we have a limited understanding of the specific functional strategies on which inselberg plants rely to thrive (Chevin and Hoffmann, 2017; Fernández-Marín et al., 2020).

Inselbergs are good model systems to study the strategies of plants living in extreme ecosystems because their high floristic diversity and the extraordinary number of endemic species rule out dispersal limitation as an important community assembly mechanism at local scales (Parmentier et al., 2005; Parmentier and Hardy, 2009; Sarthou et al., 2017; Yates et al., 2019). Inselbergs (from German Insel = island and Berg = mountain) are pre-Cambrian black monolithic rock outcrops that form terrestrial dome-like ‘islands’ that rise above the surrounding forest or savanna landscape (Fig. 1; Porembski and Barthlott, 2000a, b; Gröger and Huber, 2007; Porembski, 2007; Giraldo-Cañas, 2008; Lüttge, 2008). The distinct vegetation community of tropical inselbergs is subjected to multiple environmental stressors: high and highly variable air temperatures (23–40 °C, with record low temperatures of 18 °C), variable relative humidity (20–100 %), intermittent water availability, and shallow acid soils with low nutrient content (Porembski and Barthlott, 2000a; Gröger and Huber, 2007; Giraldo-Cañas, 2008; Lüttge, 2008; Sarthou et al., 2017).

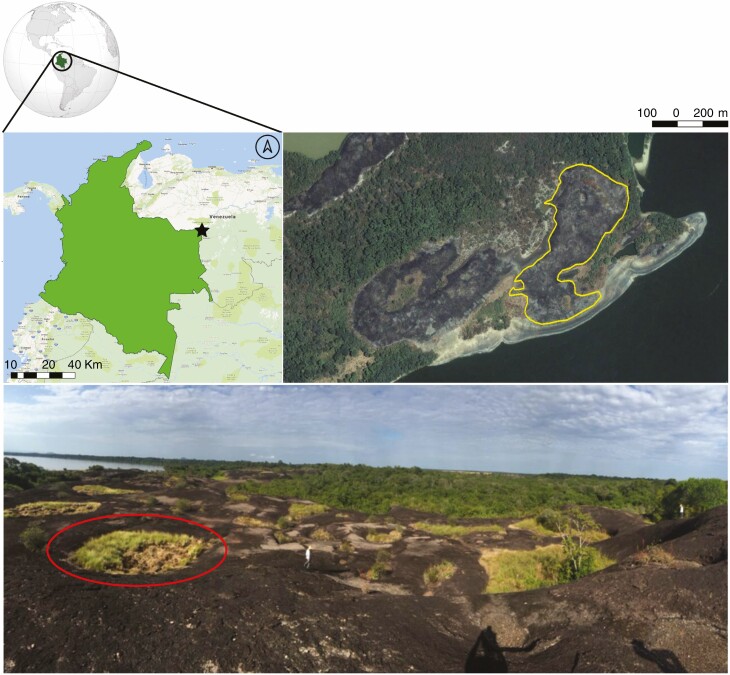

Fig. 1.

Study area, with a star indicating the ‘Reserva Natural Bojonawi’ location in Puerto Carreño, Vichada, Colombia. The yellow line demarcates the area of the inselberg studied, and the red circle indicates an example of a vegetation patch in the studied inselberg.

The floristic diversity of inselberg plant communities has been well documented in Colombia (Parra-O, 2006; Giraldo-Cañas, 2008; Tadri, 2011), but the strategies that allow plants to thrive and co-occur on inselbergs are poorly studied. We assessed the ecological and ecophysiological strategies of plants living on inselbergs by classifying them based on Grime’s CSR scheme and functional traits associated with carbon, water and light use. We specifically asked: (1) what is the primary ecological strategy of three dominant co-occurring shrub species from a Colombian inselberg based on the CSR scheme, and (2) what main functional traits characterize the ecophysiological strategy of the species based on their carbon, water and light use? We hypothesize that multiple environmental stressors on inselbergs will result in strong filtering, leading to convergent ecological and ecophysiological strategies across species. Specifically, we expected tropical inselberg environments to select for stress-tolerant species with similar ecophysiological strategies owing to similar resource-use traits.

METHODS

Study area and species

The study site, an inselberg of 5.93 ha, is in the ‘Reserva Natural Bojonawi’ (6.094958°, −67.485592°) in Vichada department (Colombia) (Fig. 1), 15 km south of the Orinoco river of Puerto Carreño at the northwestern border of the Guyanese Shield (Tadri, 2011). Puerto Carreño has an average temperature of 28.3 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 2073 mm. The rainy season occurs from May to October, during which June and July are the wettest periods. The dry season occurs from November to March, during which March is the driest month (Tadri, 2011).

The ‘Reserva Natural Bojonawi’ has three main ecosystems (forests, savannas and inselbergs), which together host 238 plant species from 72 families. Each ecosystem has a distinct flora and a unique set of species; of the 30 genera found on inselbergs, only three are shared with the forest (Buchenavia, Combretum and Eichornia) and two with the savannas (Chamaecrista and Utricularia). The forest has 114 species, the savannas 91 and the inselbergs 34 (Tadri, 2011).

We studied three common endemic shrub species growing on inselbergs: Acanthella sprucei Benth. & Hook. f., a small shrub in the Melastomataceae family; Mandevilla lancifolia Woodson., a small scandent shrub in the Apocynaceae family with abundant white latex; and Tabebuia orinocensis (Sandwith) A.H. Gentry, a shrub in the Bignoniaceae family (Parra-O, 2006; Giraldo-Cañas, 2008; Tadri, 2011). They are the most abundant shrub species in the system, dominating the vegetative cover, and represent 50 % (three of six) inselberg shrub species at ‘Reserva Natural Bojonawi’ (Tadri, 2011) and 33 % (three of nine) of all inselberg shrub species in Puerto Carreño (Parra-O, 2006).

Sampling design

The studied inselberg has 68 vegetation patches of various sizes ranging from 2.0 to 310.8 m2 (mean ± s.d. 38.6 ± 57.4 m2). Together, they represent 4.4 % of the whole inselberg area (Fig. 1). The three studied species co-occurred in 24 vegetation patches of various sizes ranging from 7.1 to 289.5 m2 (mean ± s.d. 48.2 ± 69.2 m2). We randomly chose 11 patches where the three species of interest co-occur. In each, we measured one individual per species using three recently fully mature leaves for all the traits described below (n = 11). All measurements were taken in October 2017, corresponding to the end of the rainy season.

Anatomical traits

Plant water loss depends on stomatal density and size, traits that are strictly regulated by environmental factors, and endogenous plant hormones (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Casson and Gray, 2008; Tian et al., 2016). We studied four traits related to leaf stomata: total stomatal density, stomatal length and width, and stomatal pore area index. We took prints from the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of the leaf using transparent nail polish. Once dry, we peeled the polish from the leaf and placed it on a slide. We took three photographs at ×40 magnification and classified species as amphistomatic (stomata on both sides), hypostomatic (stomata on only the abaxial side) or epistomatic (stomata on only the adaxial side). Stomata counts and measurements were averaged from photographs of three different locations per print and surface side (visual field area = 0.18 mm2) and subsequently analysed using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). We counted the number of stomata per unit area to obtain the abaxial stomatal density (sAbaxial), the adaxial stomata density (sAdaxial) and the total stomatal density (sTotal) as the sum of both. The length (sLength) and width (sWidth) were obtained from five randomly selected stomata per photograph from the abaxial side of the leaf. The stomatal pore area index (SPI, as a percentage), considered to be an integrative parameter that reflects leaf stomatal conductance (Sack et al., 2003; Tian et al., 2016), was calculated from the stomatal density and length as in eqn (1):

| (1) |

Morphological traits

Many morphological traits relate to photosynthetic capacity and are correlated with the physiological strategy of plants to deal with their environment (Wright et al., 2004; Reich, 2014; Tian et al., 2016; Kattenborn et al., 2017). Five leaf morphological traits were studied, namely leaf area (La), thickness (Lt), density (LD), dry matter content (LDMC) and specific leaf area (SLA). Leaves were collected in the field and taken to the laboratory, where they were wrapped in moist paper, placed in a plastic bag and stored in the refrigerator for 24 h at 6 °C to obtain their water-saturated mass (Lwet), then dried in an oven at 70 °C for 72 h to obtain their dry mass (Ldry). Leaf thickness (Lt) was measured with a micrometer and leaf area (La) from photographs of the leaves using Photoshop. Specific leaf area (in millimetres squared per milligram) was calculated as La/Ldry, leaf mass per unit area (LMA; in milligrams per millimetre squared) as 1/SLA, and leaf density (in milligrams per millimetre cubed) as LMA/Lt. Leaf dry matter content (in milligrams per gram) was calculated as Ldry/Lwet (Pérez-Harguindeguy et al., 2013).

Physiological traits

We studied 14 physiological traits related to water regulation, leaf-level gas exchange and photoinhibition (chlorophyll a fluorescence). To evaluate the capacity of different plant species to regulate their hydric status, we measured the water potential of leaves at predawn (ψPD; 03.00–05.00 h) and midday (ψMD; 12.00–14.00 h) with a Scholander pressure chamber (model 1505D-EXP; PMS Instrument, Albany, OR, USA). Predawn water potential reflects the best hydric status of the plant, when water potential is at equilibrium with the soil water potential. In contrast, midday water potential reflects the worst hydric status of the plant, when evaporative water demand is the greatest. Daily change in water potential (Δψ = ψMD − ψPD) is related to how well a plant regulates its water losses and gains (Bargali and Tewari, 2004). For M. lancifolia and T. orinocensis, measurements were taken from the leaf, but for A. sprucei, a species with short petiole leaves, measurements were taken from a small branch with four or five leaves. In all cases, leaves were covered with aluminum foil and a Ziplock bag for 15 min before measurements to allow the water potential of the cells and the xylem to reach equilibrium and prevent biases related to leaf excision (Roman et al., 2015).

Light-response curves were constructed using a portable infrared gas analyser (LiCor 6400XT; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA) to study leaf-level gas exchange on one fully expanded mature leaf per individual on each vegetation patch. Light curves were measured from 06.00 to 10.00 h. From the light curves, the following photosynthetic parameters were obtained: the maximum photosynthesis per area (AMarea; in micromoles of CO2 per square metre per second), the light saturation point (LSP; in micromoles (photons) per square metre per second), light compensation point (LCP; in micromoles of CO2 per square metre per second), dark respiration rate (Rd; in micromoles of CO2 per square metre per second), and the maximum photosynthesis per mass (AMmass; in micromoles of CO2 per gram per second) that was obtained based on AMarea and the LMA. To construct the light curve, we used ten photon flux density values (in micromoles per square metre per second): 2500, 2000, 1500, 2500, 1000, 500, 250, 100, 50 and 0. Each light-response curve was fitted to the 11 models proposed by Lobo et al. (2013), selecting the best-fitting curve as the one with the smallest sum of squares errors.

Additionally, midday assimilation measurements were taken (between 12.00 and 14.00 h) by setting the chamber photosynthetic photon flux density and water vapour concentrations to match ambient conditions in the field. We set CO2 to 400 ppm and the stomatal ratio to zero for A. sprucei (hypostomatic) and one for M. lancifolia and T. orinocensis (amphistomatic). Measurements were taken after reaching steady-state conditions over a relatively short time period (~2 min in standard conditions) to avoid excessive increases in chamber humidity (Roman et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). From these measurements, we obtained midday leaf-level assimilation (A; in micromoles of CO2 per square metre per second), transpiration rate (E; in millimoles of H2O per square metre per second), stomatal conductance (gs; in moles of H2O per square metre per second), instantaneous water-use efficiency (insWUE; in micromoles of CO2 per millimole of H2O) and intrinsic water-use efficiency (intWUE; in micromoles of CO2 per mole of H2O).

Fluorescence measurements were collected using a portable field chlorophyll fluorometer (OS-30P+; Opti-Sciences, Hudson, NH, USA) to evaluate the level of stress and photodamage related to high radiation. If plants are well adapted to the high light intensity typical of inselbergs, they are expected to have reduced diurnal photoinhibition. However, differences in this parameter will reflect a greater or lesser ability of species to dissipate excess light (Durand and Goldstein, 2001). We determined (Fv/Fm), where Fv = (Fm − F0), and Fm and F0 are the maximum and minimum chlorophyll fluorescence measured in the dark-acclimated leaves. The Fv/Fm ratio was determined at predawn (PDfvfm) and midday (MDfvfm) by dark-adapting leaves for 30 min, then exposing them to a light pulse strong enough to saturate all the photosystem II reaction centres. Diurnal photoinhibition (DPI; as a percentage) was calculated as in eqn (2) (Cai et al., 2007):

| (2) |

Statistical analyses

The CSR strategy scheme proposed by Grime is a well-known system to classify plants using morphological functional traits based on a priori defined ecological strategies (Grime, 1974, 1977, 2001). By using La, SLA and LDMC, plants are categorized based on their ability to compete for resources (competitors or C strategists), tolerate stress (stress-tolerant or S strategists) or survive disturbance (ruderal or R strategists) (Hodgson et al., 1999; Cerabolini et al., 2010; Pierce et al., 2017). We calculated the CSR strategy of each individual from their La, SLA and LDMC traits using ‘StrateFy’, which produces CSR ternary coordinates converted into a red, green and blue (RGB) combination based on multivariate analysis (Pierce et al., 2017). The species and environments used to develop the ‘StrateFy’ tool include species similar to ours (Pierce et al., 2017). Data from the 11 vegetation patches per species were used to create a ternary plot (Hamilton and Ferry, 2018) known as the ‘trade-off triangle’ (Pierce et al., 2017).

A principal components analysis (PCA) was performed for each functional trait set (anatomical, morphological and physiological traits) to evaluate the ecophysiological strategies of the species and determine if they had similar carbon, water and light use. For each PCA, we ran a PERMANOVA (Oksanen et al., 2018) to differentiate groups based on the Euclidean distances among individuals. We ran a PCA combining those anatomical, morphological and physiological traits that had an above-average contribution in explaining the variance in each individual PCA to show the effect of the three types of functional traits together (Kassambara and Mundt, 2017). This general matrix distance of the PCA was used to calculate Pearson correlation for pairwise combinations of traits, visualized using R package ‘corrplot’ v.0.84 (Wei and Simko, 2021). We ran a PERMANOVA based on the traits used for the general PCA to determine whether the species differ in their ecophysiological strategies (Oksanen et al., 2018). We performed linear mixed models (LMM) using the vegetation patches as a random effect and species as fixed effects to measure individual differences in resource-use traits among species. Normal data distribution was tested with a Shapiro–Wilk normality test and log-transformed when necessary. All statistical analyses were done using R (R Core Team, 2021).

RESULTS

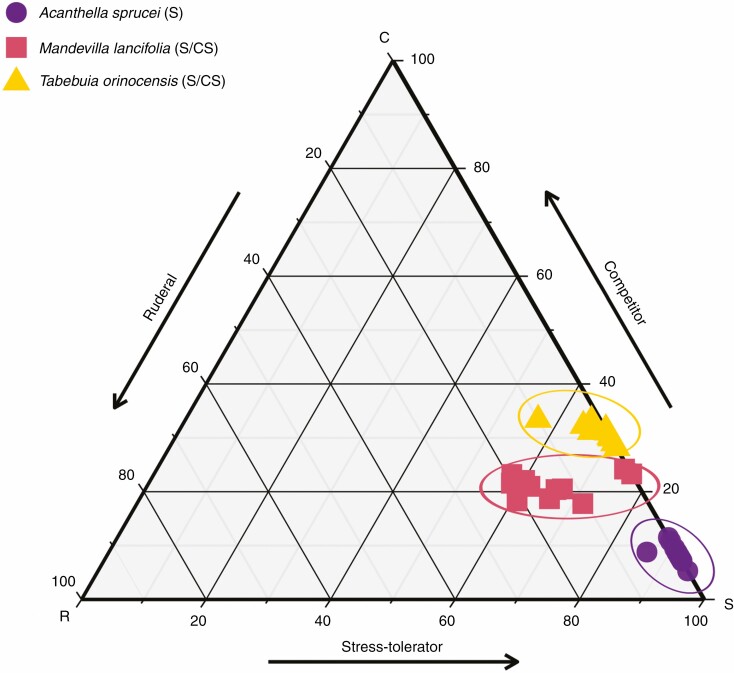

Ecological strategy classification using Grime’s CSR strategy scheme

Grime’s CSR strategy scheme sorted the three studied species into two groups; stress-tolerant (S) and stress-tolerant/competitor (S/SC) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data Table S1). A. sprucei exhibited an S strategy, whereas T. orinocensis and M. lancifolia exhibited an S/CS strategy (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data Table S1). These last two species had different proportions of R and C values: M. lancifolia was the most ruderal, with 14 % R, and T. orinocensis was the most competitive, with 31 % C.

Fig. 2.

Ternary plot showing the relative proportion (as a percentage) of C, S and R selection for Acanthella sprucei, Mandevilla lancifolia and Tabebuia orinocensis, calculated using the globally calibrated CSR analysis tool ‘StrateFy’ (Pierce et al., 2017). Data were plotted using different shapes and colours for each species.

Ecophysiological strategy classification using carbon-, water- and light-use traits

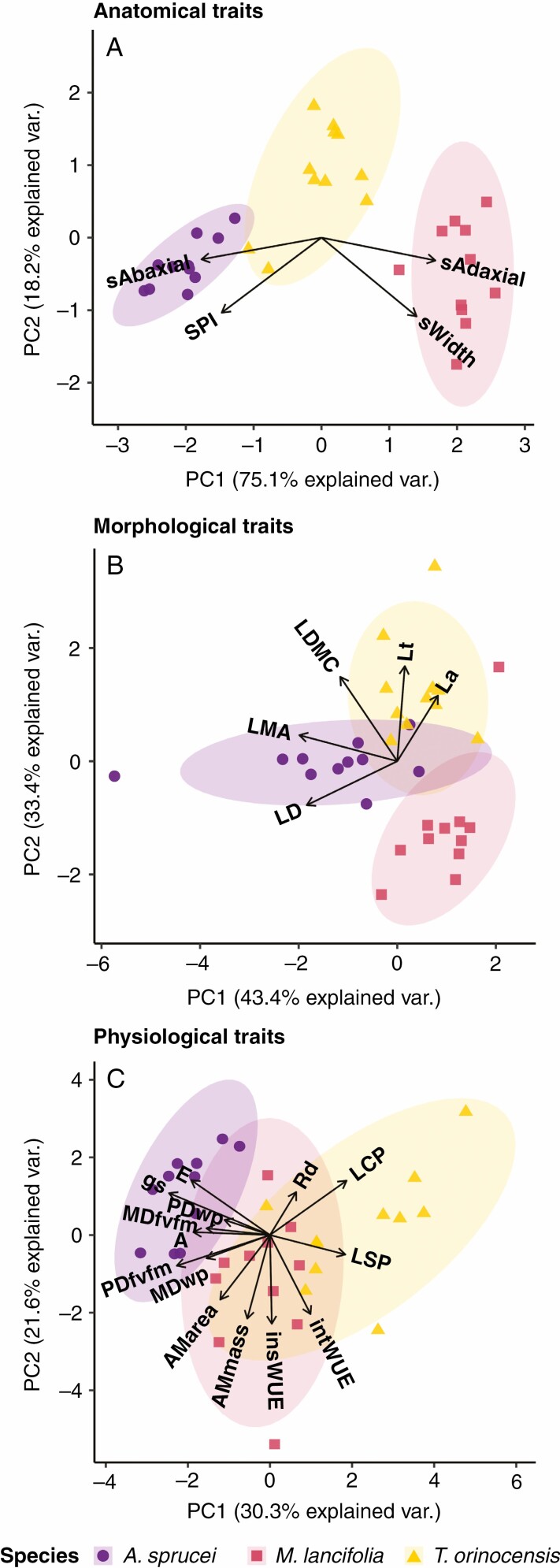

Depending on the traits considered, species can be classified into two or three ecophysiological strategies. All species are significantly different from each other based on only the anatomical traits (PERMANOVA: F = 213.4, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). In contrast, based on morphological traits, A. sprucei and T. orinocensis are indistinguishable from each other but distinct from M. lancifolia (PERMANOVA: F = 41.3, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). When physiological traits were considered, A. sprucei and T. orinocensis were different from each other, and M. lancifolia had intermediate values indistinguishable from both (PERMANOVA: F = 4.79, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). When a general PCA was created including all three types of traits (see Supplementary Data Tables S2–S4), each species showed a different ecophysiological strategy (PERMANOVA: F = 38.47, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Principal components analysis of the anatomical (A), morphological (B) and physiological (C) traits of Acanthella sprucei, Mandevilla lancifolia and Tabebuia orinocensis.

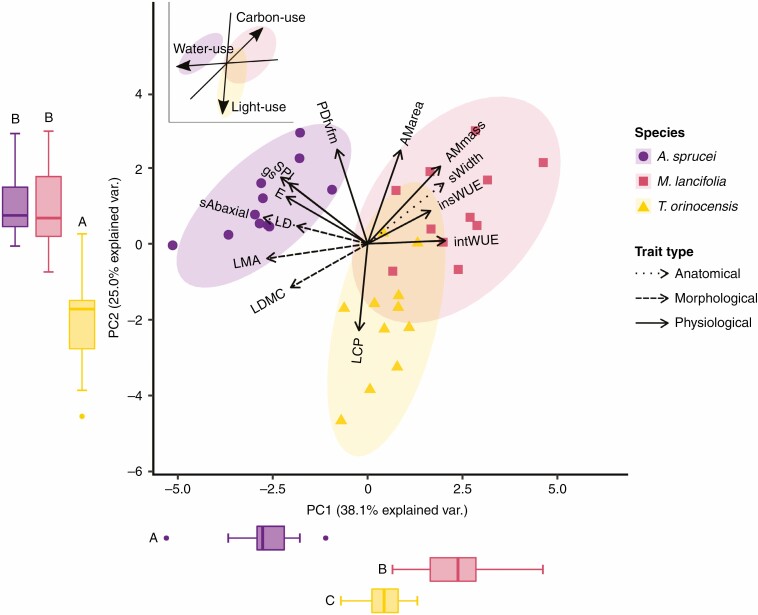

Fig. 4.

General principal components analysis was conducted on the traits with higher than the average contribution to both principal components (PC)1 and PC2 of the anatomical, morphological and physiological principal components analysis (cf. Fig. 3). Dotted lines represent anatomical traits, dashed lines represent morphological traits, and continuous lines represent physiological traits.

In the general PCA (Fig. 4), the three species were different from each other based on principal component (PC)1 (F = 73.34, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05), whereas based on PC2, A. sprucei and M. lancifolia were similar to one another and different from T. orinocensis (F = 22.67, d.f. = 2, P < 0.05). Along PC1 (Fig. 4; Table 1), we have at one end A. sprucei, with the highest stomatal density (629.2 ± 44.8 mm−2), smallest stomata (17.3 ± 0.6 µm) and highest LMA (0.15 ± 0.05 mg mm−2) and LDMC (384.2 ± 29.7 mg g−1). At the other end, M. lancifolia is the species with the lowest stomatal density (270. 3 ± 45.5 mm−2), largest stomata (26.0 ± 1.1 µm) and lowest LMA (0.08 ± 0.02 mg mm−2) and LDMC (300.6 ± 23.9 mg g−1). In the middle, T. orinocensis has intermediate values of stomatal density (379 ± 65 mm−2), stomatal size (20.5 ± 1.6 µm) and LMA (0.11 ± 0.02 mg mm−2) (Supplementary Data Fig. S1A–D).

Table 1.

Square loadings (proportion of variance in the trait explained by the principal component) and contribution (as a percentage) to principal components 1 and 2 of the traits used in the general principal components analysis (Fig. 4)

| Square loadings | Contribution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait name | Acronym | Units | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 |

| Abaxial stomatal density | sAbaxial | mm−2 | 0.765* | 0.049 | 14.356 | 1.395 |

| Stomatal pore index | SPI | % | 0.438* | 0.260* | 8.215 | 7.444 |

| Stomatal width | sWidth | μm | 0.409* | 0.259* | 7.672 | 7.401 |

| Leaf mass per area | LMA | mg mm−2 | 0.716* | 0.015 | 13.446 | 0.439 |

| Leaf density | LD | mg mm−3 | 0.352* | 0.022 | 6.615 | 0.645 |

| Leaf dry matter content | LDMC | mg g−1 | 0.418* | 0.135* | 7.842 | 3.850 |

| Stomatal conductance | gs | mol H2O m−2 s−1 | 0.532* | 0.313* | 9.994 | 8.951 |

| Transpiration rate | E | mmol H2O m−2 s−1 | 0.468* | 0.157* | 8.776 | 4.486 |

| Instantaneous water-use efficiency | insWUE | µmol CO2 mmol−1 H2O | 0.280* | 0.078 | 5.259 | 2.220 |

| Intrinsic water-use efficiency | intWUE | µmol CO2 mol−1 H2O | 0.429* | 0.001 | 8.012 | 0.020 |

| Maximum photosynthesis per area | AMarea | µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 | 0.077 | 0.621* | 1.439 | 17.747 |

| Light compensation point | LCP | µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 | 0.005 | 0.531* | 0.098 | 15.191 |

| Predawn Fv/Fm | PDfvfm | – | 0.066 | 0.631* | 1.232 | 18.053 |

| Maximum photosynthesis per unit mass | AMmass | µmol CO2 g−1 s−1 | 0.375* | 0.425* | 7.042 | 12.157 |

Abbreviation: PC, principal component.

*Traits significantly correlated with each of the PCs. Fv/Fm = Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII.

Although the higher LDMC values of A. sprucei (384.2 ± 29.7 mg g−1) and T. orinocensis (382.9 ± 20.5 mg g−1) do not distinguish these two species in trait space, they place them in the CS corner of the CSR triangle, indicating efficient conservation of resources within well-protected tissues (Fig. 2). Differences in the SLA and La values of the species (Supplementary Data Table S1) distance them from the S corner, moving M. lancifolia towards the R corner (Supplementary Data Fig. 2).

Based on leaf water-use traits expressed per unit area (gs and intWUE), A. sprucei has the highest gs (0.65 ± 0.12 mol H2O m−2 s−1), M. lancifolia has intermediate values (0.26 ± 0.12 mol H2O m−2 s−1), and T. orinocensis has the lowest gs (0.14 ± 0.06 mol H2O m−2 s−1) (gsLMM: F = 167.25, d.f. = 2, P < 0.01; Supplementary Data Fig. S1E). In terms of intWUE, M. lancifolia (56.8 ± 24.7 µmol CO2 mol−1 H2O) and T. orinocensis (52.4 ± 21.7 µmol CO2 mol−1 H2O) have similar values that are higher than A. sprucei (29.7 ± 17.1 µmol CO2 mol−1 H2O) (intWUELMM: F = 8.64, d.f. = 2, P < 0.01, Supplementary Data Fig. S1F). Based on leaf water-use traits expressed per unit mass, A. sprucei (153.8 ± 88 nmol CO2 m−1 s−1) and T. orinocensis (103.8 ± 58.3 nmol CO2 m−1 s−1) have a similar and lower maximum CO2 assimilation than M. lancifolia (330.5 ± 163.5 nmol CO2 m−1 s−1) (AMmassLMM: F = 14.58, d.f. = 2, P < 0.01; Supplementary data Fig. S1G). Thus, A. sprucei and T. orinocensis have different daily water use (intWUE) but similar low values of AMmass, indicating that these two species tend to have a conservative water strategy. In contrast, M. lancifolia has an acquisitive water strategy.

In terms of the ability of species to manage high irradiance, all species show some evidence of diurnal photoinhibition (LMM: F = 2.2, d.f. = 2, P = 0.14; Supplementary Data Fig. S1H), whereby their midday Fv/Fm values were significantly lower than their predawn Fv/Fm values (LMM per species: F = 14.4, d.f. = 2, P < 0.01, LMM per moment of the day: F = 111.2, d.f. = 1, P < 0.01; Supplementary Data Fig. S1H). Both A. sprucei and M. lancifolia showed similar behaviour with similar predawn and midday Fv/Fm values, whereas T. orinocensis showed the lowest Fv/Fm, especially at midday.

Light compensation point was one of the physiological traits contributing the most to both PC1 and PC2 in the PCA of physiological traits (Fig. 3B; Table 1; Supplementary Data Table S4), separating T. orinocensis from the other two species (Supplementary Data Fig. S1I). T. orinocensis has the highest compensation point (79.5 ± 71.5 µmol photons m−2 s−1), whereas A. sprucei (37.75 ± 18.17 µmol photon m−2 s−1) and M. lancifolia (35.74 ± 26.46 µmol (photon) m−2 s−1) have similar and significantly lower values (LMM: F = 7.03, d.f. = 2, P < 0.01; Supplementary Data Fig, S1I). Based on the light-use traits, the three species could be classified into two groups: (1) species with lower photoinhibition and the ability to assimilate carbon even under low light levels, which includes A. sprucei and M. lancifolia; and (2) species with the highest compensation and saturation point and the lowest PDfvfm and MDfvfm values, which includes T. orinocensis (Supplementary Data Fig. S2).

Examining the relationships among the traits significantly loading in the general PCA, stomatal density is positively correlated with gs (r = 0.75, P < 0.05) and LDMC (r = 0.6, P < 0.05). LMA is positively correlated with stomatal density (r = 0.59, P < 0.05), LDMC (r = 0.62, P < 0.05) and LD (r = 0.77, P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with AMmass (r = −0.57, P < 0.05) and intWUE (r = −0.5, P < 0.05). AMmass is positively correlated with stomatal width (r = 0.52, P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with LDMC (r = −0.62, P < 0.05) and LCP (r = −0.36, P < 0.05). PDfvfm is positively correlated with SPI (r = 0.56, P < 0.05) and negatively correlated with LCP (r = −0.56, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Data Fig. S3).

DISCUSSION

Ecological implications

The most salient result of our study is that the three co-occurring species show convergent primary ecological strategies yet have divergent ecophysiological strategies that allow them to co-dominate an extreme environment by using the limiting resources differently.

In partial agreement with our hypothesis, the three study species occupy a narrow range of the CSR space, with one S strategist and two S/CS strategists (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data Table S1). The small CSR space occupied is consistent with the hypothesis that the multiple interacting stressors on inselbergs should select stress-tolerant strategies, leading to convergent ecological strategies among co-occurring species (Weiher et al., 1995, 2011; Coyle et al., 2014; Breitschwerdt et al., 2018; Várbíró et al., 2020). However, the presence of two S/CS strategists was not expected. S/CS strategists exhibit some traits consistent with competitive strategies and are more resource acquisitive than pure S strategists. Three other studies have found CS strategists among co-occurring species in extreme tropical environments. de Paula et al. (2015) found strategies ranging from the S corner to the C corner among 53 co-occurring species on a Brazilian inselberg. Rosado and De Mattos (2016) found redundant S/CS strategies among ten co-occurring species in Brazilian sandy coastal plains. Cruz and Lasso (2021) found S and CS strategies among 42 co-occurring species in a Colombia páramo, an extreme tropical alpine ecosystem. Thus, evidence is mounting that species growing in highly stressful environments are not all purely stress-tolerant, but some also show a degree of competitivity.

In contrast to our hypothesis, the three study species show divergent ecophysiological strategies despite their convergent CSR strategies. Thus, the results highlight that dominant species with the same ecological strategies use available resources differently. Pierce et al. (2014) also observed this pattern in seminatural calcareous grasslands, where graminoids with S strategies were co-dominant owing to ecophysiological trait differences. This finding has two important implications. First, these results indicate that the ecological and ecophysiological strategy approaches provide complementary information: the CSR scheme describes the general approach to surviving in an environment (i.e. the plant strategy), whereas ecophysiological traits reveal the mechanisms underpinning that strategy (i.e. how the plant achieves this strategy). The CSR scheme provides a coarse classification of the type of environment to which the species are adapted, whereas the ecophysiological traits detail the specific physiological adaptations. Using them jointly in the present study has provided deeper insights into the ecology of inselberg plants than we could have gained by using a single approach.

Second, the leaf traits that allowed us to distinguish the ecophysiological strategies of species were resource-use traits, not those traits describing the leaf economic spectrum. Thus, our results indicate that the CSR and the leaf economics spectrum (LES) frameworks were inadequate for identifying local differences in plant strategies. The CSR framework was developed at a regional scale (Grime, 1974), and researchers have made various efforts to extend its application to local scales (cf. Cerabolini et al., 2010; Pierce et al., 2013, 2017). The LES framework provides a coarse-scale description of global diversity patterns (Wright et al., 2004; Reich, 2014). In local environments where species are clustered in a specific region of the triangle, these descriptors might be too coarse, unable to distinguish different ecophysiological strategies (Pierce et al., 2014; Messier et al., 2017; Rosado and de Mattos, 2017; Belluau and Shipley, 2018). For local ecological studies, functional traits describing resource use might be necessary to assess ecophysiological strategies accurately.

The differences in the ecophysiological strategies of these three common co-occurring shrubs raise questions about the role of traits in our detection of community assembly mechanisms in extreme environments. The similarity of species based on single or multiple characteristics is often used to infer community assembly mechanisms (Kunstler et al., 2012; Herben and Goldberg, 2014). Reduced trait range relative to a null model indicates ecological filtering (also known as species sorting), and even trait spacing among co-occurring species relative to a null model indicates limiting similarity (MacArthur and Levins, 1967; Chesson, 2000; Cornwell et al., 2006). In the present study, we did not collect the trait data in the surrounding species pool to build null models and test for ecological filtering, nor on the whole set of co-occurring species to test for limiting similarity. Nonetheless, the diversity of resource-use strategies among three common shrub species living on this tropical inselberg is unexpected and highlights the need to disentangle the role of different assembly mechanisms in extreme environments.

Two mechanisms could generate the diversity of ecophysiological strategies in this tropical inselberg. Classic community assembly theory would ascribe these differences to limiting similarity, a community assembly mechanism that leads to trait differences among co-existing species (Götzenberger et al., 2012). However, this interpretation of the results conflicts with the common view that limiting similarity is weak in highly stressful environments (Grime, 1977; Weiher et al., 1995; Coyle et al., 2014; Várbíró et al., 2020). Alternatively, multiple alternative optima could drive these differences if the abiotic environment selects species that have evolved different solutions to the same set of constraints (Niklas, 1994, 1997, 1999). Numerous theoretical lines of evidence have shown that this mechanism can create phenotypic diversity within a given stable abiotic environment (Marks and Lechowicz, 2006; Shoval et al., 2013; Worthy et al., 2020). Still, it has not been broadly adopted into the community ecology framework and has yet to gain empirical support from field or experimental studies. The targeted subset of species studied represents a third of the shrubs, and the phenotypic diversity cannot be ascribed to differences in growth form. We note the caveat that, having characterized only three co-occurring shrub species, our ability to draw inferences is limited; however, it makes finding a high diversity of resource-use strategies even more unexpected. Although we do not know what mechanisms lead to this, our results challenge the classic expectation that strong filtering from extreme environments leads to species with similar traits. Future studies directly measuring assembly mechanisms will be needed to shed light on this.

Physiological implications

Each shrub species shows a unique combination of functional traits that do not fall along with a single acquisitive or conservative strategy for using carbon, light and water. In terms of carbon assimilation, A. sprucei has the most conservative strategy (highest LMA and LDMC and low AMmass); T. orinocensis has an intermediate strategy (intermediate values of LMA, high LDMC and low AMmass), and M. lancifolia has an acquisitive strategy (lowest LMA and LDMC and high AMmass). Regarding the species water use, A. sprucei has a risky daily water use (low intWUE). In contrast, both T. orinocensis and M. lancifolia have a safer water-use strategy (high intWUE). We also found contrasting light-use strategies that differentiate the two S/CS strategists, with A. sprucei and M. lancifolia having low LCPs typical of shade-tolerant plants, whereas T. orinocensis has a high LCP typical of light-demanding plants. These decoupled relationships among different types of functional traits have been described in tropical (Santiago and Wright, 2007; Baraloto et al., 2010; Li et al., 2015) and temperate (Harayama et al., 2016) species, highlighting the relevance of measuring various functional traits to understand the strategies of plants in local communities.

Different types of light-use traits (anatomical, morphological and physiological) classify species in opposing light-use strategies. A. sprucei has a low LCP typical of shade-tolerant plants despite having anatomical and other physiological characteristics of light-demanding plants (dense, small chloroplasts, highest gs and lowest intWUE). Meanwhile, T. orinocensis has a high LCP typical of light-demanding plants, but anatomical (larger and fewer stomata) and other physiological traits (lowest gs and high intWUE) typical of shade-tolerant plants. Marino et al. (2010) proposed that because quantum yield at the LCP (φ) and dark respiration rate (Rd) determine the LCP, a change in one of these two traits without corresponding changes in the other will create variation in the LCP among species. This hypothesis could explain our findings, because the three species have similar Rd and different LCPs. Additionally, some authors have found that species with conservative strategies tend to tolerate both waterlogging and shade, A. sprucei being one of these species (Sterck et al., 2011). Contrasting classifications from different traits show that morpho-anatomical trait values do not necessarily predict physiological trait values. Therefore, we should continue looking for functional traits from multiple categories and organs in different environments.

Last, an important finding with implications for trait-based ecology is that two easily measured anatomical traits (stomatal density and size) were sufficient to characterize the carbon-use strategy of species. The known importance of stomata in regulating leaf temperature, water and CO2 use (Cowan and Farquhar, 1977) and the observed strong correlations between stomatal and physiological traits explain the capacity of these two anatomical traits to identify the carbon-use strategies described using all the physiological traits. They were also highly correlated with traits that are difficult, expensive or slow to measure (‘hard’ traits), such as stomatal conductance, maximum photosynthesis per unit mass, and predawn photosynthetic efficiency of photosystem II. This finding is significant for the field, because trait-based ecology has been searching for traits that are quick, inexpensive and easy to measure (‘soft’ traits) closely associated with physiological functions (Funk et al., 2017). Unfortunately, many morpho-anatomical traits are only related loosely to a physiological process or plant performance (Salguero-Gómez et al., 2018), such that the goal of identifying informative ‘soft’ traits remains central but elusive in the field. If this finding can be generalized to other species or environments, researchers could easily classify plant carbon-use strategies from two stomatal traits that are easy to measure.

Conclusions

This study shows that plant species with different ecophysiological strategies can co-occur in extreme environments, such as tropical inselbergs. We found convergent primary ecological strategies (S and S/CS) among three co-occurring species with divergent resource-use strategies (carbon, water and light) despite the filtering effect of highly stressful conditions on inselbergs. We conclude that the two approaches using functional traits to study species survival in different environments provide complementary information, making both necessary to understand plant survival strategies in local environments fully (Pierce et al., 2014). When we use functional traits to classify species based on adaptation to contrasting environmental challenges defined a priori (CSR scheme), we answer the question, ‘What is the plant ecological strategy?’ When we use functional traits as the central element to define the ecophysiological strategy of a species, we answer the question, ‘How does a plant execute its ecological strategy physiologically?’

The three species showed that a plant can be acquisitive for some resources and conservative for others, and different types of functional traits within the same species (e.g. anatomical vs. physiological) can be acquisitive for one resource but conservative for another. Last, we found that stomatal traits that are easy to measure are valuable for studying plant ecophysiological strategies in extreme environments. They differentiated the three species and were correlated with physiological traits that are hard to measure.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: species morphological traits, Grime’s CSR classification and resource-use strategy. Table S2: square loadings and contribution of the anatomical traits along PC1 and PC2. Table S3: square loadings and contribution of the morphological traits for PC1 and PC2. Table S4: square loadings and contribution of the physiological traits for PC1 and PC2. Figure S1: trait differences among species. Figure S2: parameters obtained from the light curves. Figure S3: Pearson’s correlations matrix for the traits used in the general PCA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Fundación Omacha for letting us work on inselbergs of the ‘Reserva Natural Bojonawi’ and all the people (Beyker Castañeda, Ester Marín, Brayan Castañeda and Jacinto Teran) in charge of the reserve for making our life easier during the field campaigns. Additionally, field campaigns would not have been possible without Diego Amaya, David Aragón, Claudia Baquero and Daniel López. Finally, we would like to thank all Ecology and Plant Physiology Group members at Universidad de los Andes for always being there during the investigation, especially Alejandra Ayarza, Indira León and Carol Garzón.

Conceptualization: A.L. and L.E.; methodology: A.L. and L.E; data collection: A.L. and A.N.; statistical analyses: A.L.; writing original draft: A.L. L.E. and M.J.; writing reviews & editing: A.L., L.E. and M.J. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lina Aragón, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia; Department of Biology, University of Waterloo, ON, Canada.

Julie Messier, Department of Biology, University of Waterloo, ON, Canada.

Natalia Atuesta-Escobar, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia.

Eloisa Lasso, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia; Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apt. 0843-03092, Balboa, Ancón, Panamá.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Geographic Early Career Grant [WW-168ER-17], the Seed grant for Master students, and the Research Fund to support faculty programmes at the Faculty of Science at the Universidad de los Andes, Colombia [grant number INV-2019-84-1805].

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21720008.v4.

LITERATURE CITED

- Baraloto C, Paine CET, Poorter L, et al. 2010. Decoupled leaf and stem economics in rain forest trees. Ecology Letters 13: 1338–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargali K, Tewari A.. 2004. Growth and water relation parameters in drought-stressed Coriaria nepalensis seedlings. Journal of Arid Environments 58: 505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2004.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli G, Bottega S, Forino LMC, Ciccarelli D, Spanò C.. 2014. Plant adaptation to extreme environments: the example of Cistus salviifolius of an active geothermal alteration field. Comptes Rendus Biologies 337: 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluau M, Shipley B.. 2018. Linking hard and soft traits: physiology, morphology and anatomy interact to determine habitat affinities to soil water availability in herbaceous dicots. PLoS One 13: e0193130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard-Verdier M, Navas ML, Vellend M, Violle C, Fayolle A, Garnier E.. 2012. Community assembly along a soil depth gradient: contrasting patterns of plant trait convergence and divergence in a Mediterranean rangeland. Journal of Ecology 100: 1422–1433. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschwerdt E, Jandt U, Bruelheide H.. 2018. Using co-occurrence information and trait composition to understand individual plant performance in grassland communities. Scientific Reports 8: 9076. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z Quan, L Poorter, Cao K-F, Bongers F.. 2007. Seedling growth strategies in Bauhinia species: comparing lianas and trees. Annals of Botany 100: 831–838. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnwath G, Nelson C.. 2017. Effects of biotic and abiotic factors on resistance versus resilience of Douglas fir to drought. PLoS One 12: e0185604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson S, Gray JE.. 2008. Influence of environmental factors on stomatal development. New Phytologist 178: 9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerabolini BEL, Brusa G, Ceriani RM, de Andreis R, Luzzaro A, Pierce S.. 2010. Can CSR classification be generally applied outside Britain? Plant Ecology 210: 253–261. doi: 10.1007/s11258-010-9753-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson P. 2000. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31: 343–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chevin L-M, Hoffmann AA.. 2017. Evolution of phenotypic plasticity in extreme environments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 372: 20160138. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell WK, Schwilk DW, Ackerly DD.. 2006. A trait‐based test for habitat filtering: convex hull volume. Ecology 87: 1465–1471. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1465:attfhf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan IR, Farquhar GD.. 1977. Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 31: 471–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JR, Halliday FW, Lopez BE, Palmquist KA, Wilfahrt PA, Hurlbert AH.. 2014. Using trait and phylogenetic diversity to evaluate the generality of the stress-dominance hypothesis in eastern North American tree communities. Ecography 37: 814–826. doi: 10.1111/ecog.00473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz M, Lasso E.. 2021. Insights into the functional ecology of Páramo plants in Colombia.. Biotropica 53: 1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/btp.12992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Kattge J, Cornelissen JHC, et al. 2016. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529: 167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature16489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand LZ, Goldstein G.. 2001. Photosynthesis, photoinhibition, and nitrogen use efficiency in native and invasive tree ferns in Hawaii. Oecologia 126: 345–354. doi: 10.1007/s004420000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Marín B, Gulías J, Figueroa CM, et al. 2020. How do vascular plants perform photosynthesis in extreme environments? An integrative ecophysiological and biochemical story. Plant Journal 101: 979–1000. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, Larson JE, Ames GM, et al. 2017. Revisiting the Holy Grail using plant functional traits to understand ecological processes. Biological Reviews 92: 1156–1173. doi: 10.1111/brv/12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Cañas D. 2008. Flora Vascular de los Afloramientos Precámbricos (Lajas - Inselbergs) de la Amazonia Colombiana y Areas Adyacentes del Vichada: i. Composición Florística. Serie Colombia Diversidad Biótica VII: Vegetación, Palinología y Paleoecología de La Amazonia Colombiana: 89–118. In: Rangel-Ch JO, ed. Colombia, Diversidad Biótica VII (Vegetación, palinología y paleoecología de la Amazonía colombiana). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Bogotá. [Google Scholar]

- Götzenberger L, de Bello F, Bråthen KA, et al. 2012. Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biological Reviews 87: 111–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. 1974. Vegetation classification by reference to strategies. Nature 250: 26–31. doi: 10.1038/250026a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist 111: 1169–1194. doi: 10.1086/283244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. 2001. Plant strategies, vegetation processes, and ecosystem properties, 2nd Edition. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gröger A, Huber O.. 2007. Rock outcrop habitats in the Venezuelan Guayana lowlands: their main vegetation types and floristic components. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 30: 599–609. doi: 10.1590/s0100-84042007000400006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, NE, Ferry, M.. 2018. ggtern: Ternary diagrams using ggplot2. Journal of Statistical Software 87: 1–17. doi: 10.18637/jss.v087.c03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama H, Ishida A, Yoshimura J.. 2016. Overwintering evergreen oaks reverse typical relationships between leaf traits in a species spectrum. Royal Society Open Science 3: 7. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herben T, Goldberg DE.. 2014. Community assembly by limiting similarity vs. competitive hierarchies: testing the consequences of dispersion of individual traits. Journal of Ecology 102: 156–166. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FI.. 2003. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424: 901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson JG, Wilson PJ, Hunt R, Grime JP, Thompson K.. 1999. Allocating C-S-R plant functional types: a soft approach to a hard problem. Oikos 85: 282–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A, Mundt F.. 2017. Factoextra: extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses. R Package Version 1: 1–76. https://cran.r-project.org/package=factoextra [Google Scholar]

- Kattenborn T, Fassnacht FE, Pierce S, Lopatin J, Grime JP, Schmidtlein S.. 2017. Linking plant strategies and plant traits derived by radiative transfer modelling. Journal of Vegetation Science 28: 717–727. doi: 10.1111/jvs.12525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunstler G, Lavergne S, Courbaud B, et al. 2012. Competitive interactions between forest trees are driven by species’ trait hierarchy, not phylogenetic or functional similarity: implications for forest community assembly. Ecology Letters 15: 831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, McCormack ML, Ma C, et al. 2015. Leaf economics and hydraulic traits are decoupled in five species-rich tropical-subtropical forests. Ecology Letters 18: 899–906. doi: 10.1111/ele.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, FdA, de Barros MP, Dalmagro HJ, et al. 2013. Fitting net photosynthetic light-response curves with Microsoft Excel — a critical look at the models. Photosynthetica 51: 445–456. doi: 10.1007/s11099-013-0045-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lortie CJ, Brooker RW, Choler P, et al. 2004. Rethinking plant community theory. Oikos 107: 433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13250.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttge U. 2008. Physiological ecology of tropical plants. 2nd Edition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur R, Levins R.. 1967. The limiting similarity, convergence, and divergence of coexisting species. The American Naturalist 101: 377–385. doi: 10.1086/282505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Aqil M, Shipley B.. 2010. The leaf economics spectrum and the prediction of photosynthetic light-response curves. Functional Ecology 24: 263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01630.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marks CO, Lechowicz MJ.. 2006. Alternative designs and the evolution of functional diversity. The American Naturalist 167: 55–66. doi: 10.1086/498276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier J, Lechowicz MJ, McGill BJ, Violle C, Enquist BJ.. 2017. Interspecific integration of trait dimensions at local scales: the plant phenotype as an integrated network. Journal of Ecology 105: 1775–1790. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niklas KJ. 1994. Morphological evolution through complex domains of fitness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91: 6772–6779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklas KJ. 1997. Adaptive walks through fitness landscapes for early vascular land plants. American Journal of Botany 84: 16–25. doi: 10.2307/2445878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niklas KJ. 1999. Evolutionary walks through a land plant morphospace. Journal of Experimental Botany 50: 39–52. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.330.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, et al. 2018. Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier I, Hardy OJ.. 2009. The impact of ecological differentiation and dispersal limitation on species turnover and phylogenetic structure of inselberg’s plant communities. Ecography 32: 613–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05697.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier I, Stévart T, Hardy OJ.. 2005. The inselberg flora of Atlantic Central Africa. I. Determinants of species assemblages. Journal of Biogeography 32: 685–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01243.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-O C. 2006. Estudio general de la vegetación nativa de Puerto Carreño (Vichada, Colombia). Caldasia 28: 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- de Paula LFA, Negreiros D, Azevedo LO, Fernandes R, Stehmann JR, Silveita FAO.. 2015. Functional ecology as a missing link for conservation of a resource-limited flora in the Atlantic Forest. Biodiversity Conservation 24: 2239–2253. doi: 10.1007/s10531-015-0904-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Harguindeguy N, Diaz S, Garnier E, et al. 2013. New handbook for standardized measurment of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany 61: 167–234. doi: 10.1071/BT12225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, Brusa G, Vagge I, Cerabolini BEL.. 2013. Allocating CSR plant functional types: the use of leaf economics and size traits to classify woody and herbaceous vascular plants. Functional Ecology 27: 1002–1010. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, Vagge I, Brusa G, Cerabolini BEL.. 2014. The intimacy between sexual traits and Grime’s CSR strategies for orchids coexisting in semi-natural calcareous grassland at the Olive Lawn. Plant Ecology 215: 495–505. doi: 10.1007/s11258-014-0318-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, Negreiros D, Cerabolini BEL, et al. 2017. A global method for calculating plant CSR ecological strategies applied across biomes world-wide. Functional Ecology 31: 444–457. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porembski S. 2007. Tropical inselbergs: habitat types, adaptive strategies and diversity patterns. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 30: 579–586. doi: 10.1590/s0100-84042007000400004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porembski S, Barthlott W.. 2000a. Granitic and gneissic outcrops (inselbergs) as centers of diversity for desiccation-tolerant vascular plants. Plant Ecology 151: 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Porembski S, Barthlott W.. 2000b. Inselbergs: biotic diversity of isolated rock outcrops in tropical and temperate regions, Vol. 146. Porembski S, Barthlott W, eds. Ecological Studies. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB. 2014. The world-wide ‘fast–slow’ plant economics spectrum: a traits manifesto. Journal of Ecology 102: 275–301. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roman DT, Novick KA, Brzostek ER, Dragoni D, Rahman F, Phillips RP.. 2015. The role of isohydric and anisohydric species in determining ecosystem-scale response to severe drought. Oecologia 179: 641–654. doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado BHP, De Mattos EA.. 2016. Chlorophyll fluorescence varies more across seasons than leaf water potential in drought-prone plants. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 88: 549–563. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201620150013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado BHP, de Mattos EA.. 2017. On the relative importance of CSR ecological strategies and integrative traits to explain species dominance at local scales. Functional Ecology 31: 1969–1974. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Cowan PD, Jaikumar N, Holbrook NM.. 2003. The ‘hydrology’ of leaves: co-ordination of structure and function in temperate woody species. Plant, Cell & Environment 26: 1343–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2003.01058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salguero-Gómez R, Violle C, Gimenez O, Childs D.. 2018. Delivering the promises of trait-based approaches to the needs of demographic approaches, and vice versa. Functional Ecology 32: 1424–1435. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago LS, Wright SJ.. 2007. Leaf functional traits of tropical forest plants in relation to growth form. Functional Ecology 21: 19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthou C, Pavoine S, Pierre Gasc J-P, de Massary J-C, Ponge J-F.. 2017. From inselberg to inselberg: floristic patterns across scales in French Guiana (South America). Flora 229: 147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2017.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, et al. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoval O, Sheftel H, Shinar G, et al. 2013. Evolutionary trade-offs, pareto optimality, and the geometry of phenotype space. Science 336: 1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1228281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterck F, Markesteijn L, Schieving F, Poorter L.. 2011. Functional traits determine trade-offs and niches in a tropical forest community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 20627–20632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadri GJ. 2011. Vegetación Vascular de La Reserva Natural Bojonawi (Vichada, Colombia): Aportes Para La Elaboación de La Flórula. [Biology bachelor's degree, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana]. http://hdl.handle.net/10554/8880

- Tian M, Yu G, He N, Hou J.. 2016. Leaf morphological and anatomical traits from tropical to temperate coniferous forests: mechanisms and influencing factors. Scientific Reports 6: 19703. doi: 10.1038/srep19703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Várbíró G, Borics G, Novais MH, et al. 2020. Environmental filtering and limiting similarity as main forces driving diatom community structure in Mediterranean and continental temporary and perennial streams. Science of the Total Environment 741: 140459. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellend M. 2010. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology 85: 183–206. doi: 10.1086/652373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violle C, Navas ML, Vile D, et al. 2007. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 116: 882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volaire F. 2018. A unified framework of plant adaptive strategies to drought: crossing scales and disciplines. Global Change Biology 24: 2929–2938. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lu W, Tong Y, Yang Q.. 2016. Leaf morphology, photosynthetic performance, chlorophyll fluorescence, stomatal development of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) exposed to different ratios of red light to blue light. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 250. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T, Simko V.. 2021. 'corrplot': Visualization of a Correlation Matrix . R package version 0.92, https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot

- Weiher E, Keddy PA, Box PO, Station A, Kin C.. 1995. Assembly rules, null models, and trait dispersion: new questions from old patterns. Oikos 74: 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Weiher E, Freund D, Bunton T, Stefanski A, Lee T, Bentivenga S.. 2011. Advances, challenges and a developing synthesis of ecological community assembly theory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366: 2403–2413. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M. 1998. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant and Soil 199: 213–227. doi: 10.1023/A:1004327224729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthy SJ, Laughlin DC, Zambrano J, et al. 2020. Alternative designs and tropical tree seedling growth performance landscapes. Ecology 101: e03007. doi: 10.1002/ecy.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, et al. 2004. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428: 821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates CJ, Robinson T, Wardell-Johnson GW, et al. 2019. High species diversity and turnover in granite inselberg floras highlight the need for a conservation strategy protecting many outcrops. Ecology and Evolution 9: 7660–7675. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21720008.v4.