Abstract

Personas are widely recognized as valuable design tools for communicating dimensions of individuals, yet they often lack critical contextual factors. For those people managing chronic health conditions, the home is a critical context of their patient work system (PWS). We propose the development of ‘home personas’ to convey essential aspects of the home context to those tasked with designing technologies and interventions to fit it. We used an iterative, multi-stakeholder design process to design ‘home personas’ for a model population, families caring for children with medical complexity. Each of the four resultant home personas—Multi-level, Customized, Ranch, and Rental—has a unique home layout, pain points, and are described on three dimensions that emerged from the data. This study builds on a foundation of work in the emerging field of Patient Ergonomics, describing a mechanism for distilling rich descriptions of the PWS into brief yet informative design tools.

Keywords: Persona, Sociotechnical system, Macroergonomics, Patient work, Children with Medical Complexity

1. Introduction

Personas are widely recognized as valuable tools for communicating dimensions of individuals that need to be accounted for in design (Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). By bringing to life a ‘user’ with an identity, needs, goals, and tasks to be performed, personas help designers build empathy for whom they are designing for (Friess, 2012; Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011; Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). There are many other benefits of persona use, including improved usability, prevention of self-referential design (i.e., where designers unintentionally design for their own needs), and improved interdisciplinary design team communication and collaboration (Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011). Yet, while personas are essential tools for human-centered research and design, they often lack critical contextual factors, an understanding of which is critical for designing technology that is usable, safe, and satisfying (Holden et al., 2013; Or et al., 2008).

1.1. Home as a sociotechnical system shaping self-management of chronic conditions

Understanding contextual factors is especially important for designing technologies for the millions of people managing chronic health conditions (National Research Council, 2011). One of the most common yet poorly understood contexts within which people manage their health is the home. (Bodenheimer et al., 2002; National Research Council, 2011). Researchers who have conceptualized the home as a sociotechnical system—i.e., a work system with interacting components of person(s) performing tasks with tools and technology in the home and community context—have begun to describe the ways in which the home shapes the self-management of one’s chronic conditions (Holden et al., 2015; Jolliff et al., 2020; Moen & Brennan, 2005; Novak et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2018; Werner, Tong, et al., 2020; Zayas-Cabán & Dixon, 2010). For example, Werner et al. (2018)’s study of people with diabetes found that the home environment played an integral role in their personal health information management (PHIM) (Moen & Brennan, 2005). While typically thought of as a cognitive activity, individuals used their home environment to support their PHIM such as by placing health documents on the table for their partner to read before throwing them away or organizing medications on the counter by the time of day in which they were to be taken (Werner et al., 2018). Another study by Novak et al. (2020), demonstrated that individuals’ care routines were intimately related to the cultural practices of one’s home. They identified that anchoring health-management activities alongside cultural practices made routines more resilient to errors. Thus, the interaction one has with their home environment is critical in shaping their health behaviors.

Conceptualizing the home as a sociotechnical system is a key area of research in the emerging field of Patient Ergonomics, i.e. the application of Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE) to study or improve patients’ or other non-professionals’ performance of effortful work activities in pursuit of health goals, i.e., patient work (Holden & Valdez, 2018; Holden & Valdez, 2019). Informed by existing work systems models, e.g., the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety or SEIPS (Carayon et al., 2006), the Patient Work System (PWS) model specifically centers the work of patients and their caregivers (Werner, Ponnala, et al., 2020). The PWS model depicts four interacting components—person(s), tasks, tools, and context, where contexts may be physical-spatial, cultural-social, or organizational (Holden et al., 2015)—and has been useful for researchers studying and producing contextualized models for a variety of instances of patient work, e.g., medication management, care transitions, etc. (Werner, Ponnala, et al., 2020). As the field of Patient Ergonomics grows, the continued development of methods that are sensitive to the distinct experiences and contexts of patients is necessary (Holden et al., 2020; Valdez et al., 2017). Further, there is a design imperative to move beyond descriptive studies to develop methods for the creation of practical tools.

When we neglect to design tools and technologies that are aligned with the sociotechnical system of the home, people encounter obstacles posed by the resulting mismatch (Zayas-Cabán & Dixon, 2010). In some cases, obstacles are so problematic that people and/or their caregivers must develop strategies for overcoming them (Barton et al., 2021; Barton et al., 2020; Holden et al., 2015). For example, families caring for children with medical complexity (CMC) often develop workarounds to fit medical devices to their home context (Barton et al., 2021). Some families, however, may be less adept at overcoming obstacles or more prone to using workarounds that introduce risk—based on their access to knowledge/education, financial resources, and time—which then becomes an equity issue (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., 2020). Thus, to improve safety, reduce burden, and reduce potential disparities, designers must consider the home context to design technology that aligns with the sociotechnical system of the home. We propose utilizing the concept of personas to communicate the home context to designers tasked with designing for the home by developing ‘home personas.’

1.2. Children with medical complexity as a case study population

Children with medical complexity (CMC) are a population who rely extensively on their home as a context for caregiving and healthcare delivery. CMC are characterized by their high healthcare utilization, reliance on medical devices to replace core body functions, multiple chronic conditions, and significant care needs, typically met by family caregivers in the home (Berry et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2011). They represent an ideal case for the initial development of ‘home personas’ given that the care work that families do is comprehensive (e.g., management and operation of medical devices, medication administration, daily care tasks, implementation of therapies, etc.). The interactions between these complex care regimens and the home context (e.g., the need to account for caregivers in the physical space, the need to account for medical equipment and technology, the potential need for spatial modifications, the need for managing medication and therapies, etc.) are likely to yield dimensions of the home that could be relevant to other individuals’ self-management and care more broadly. For these reasons, CMC and their families are a model population in which to study the aspects of the home context that are most salient to the individuals receiving and providing care within it.

1.3. Objectives

As such, the objectives of this study were to 1) identify and enumerate the key aspects of the home context to be included in a ‘home persona’ and 2) develop ‘home personas’ for our case study population. The resulting home personas could then be used to inform the design of tools, technologies, and environments that are sensitive to and informed by the full sociotechnical system.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of data collected during two previous research studies conducted at two sites, which we have termed the “primary studies.” Data from the first study (Primary Study 1) was used to achieve objective 1, identifying aspects of the home to be included in a home persona, as well as to create initial home personas towards the achievement of objective 2. Data from the second study (Primary Study 2) was used to achieve objective 2.

2.2. Primary Study Setting and Sample

Primary Study 1.

The population of primary study one (PS1) included caregivers of CMC that were enrolled in a pediatric complex care program (PCCP) at a midwestern academic children’s hospital. The participants lived in private residences within 1.5-hour drive of the hospital (Barton et al., 2021).

Primary Study 2.

The population of primary study two (PS2) included families of CMC and their social network. A family was defined as a child with medical complexity and their parent(s). Additional members of the social network were identified and recruited by the parents to participate in the study using snowball sampling. The CMC was enrolled in an academic children’s hospital that provides specialist inpatient and outpatient services, including a pediatric complex care clinic (Valdez et al., 2020).

2.3. Primary Study Procedure

Primary Study 1.

The goal of PS1 was to explore barriers and facilitators in the work system of family caregivers of CMC (Barton et al., 2020; Doutcheva et al., 2019; Parks et al., 2021). The researchers conducted a contextual inquiry in the participants’ homes (Holtzblatt & Beyer, 2016; Valdez & Holden, 2016). Two researchers went to each home and the visits lasted up to 2 hours. Caregivers were asked to physically take the interviewers through their homes demonstrating their everyday routine of caregiving. Interviewers asked probing questions guided by the second iteration of the SEIPS model, SEIPS 2.0 (see Appendix), both during and after the demonstration to obtain additional information or clarification regarding the work system (Holden et al., 2013). Observation notes and photographs of artifacts were taken by the second interviewer. Home visits were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection took place from October 2017 to January 2019.

Primary Study 2.

The goal of PS2 was to understand self-management experiences of families of CMC and how individual-, family-, and system-level factors influence approaches to care (Valdez et al., 2020). Data collection consisted of semi-structured interviews with children, parents, and social network members. The semi-structured interviews consisted of four overarching domains. The first three parts were with the family of the CMC, and the final part was with social network members. The first part consisted of open-ended questions regarding daily routines, the second part consisted of identifying how social network members fit into self-management and care tasks, the third part focused on how work system components shape self-management, and the final part was with the social network members to capture how they perceived themselves to fit into the care management of the CMC (Valdez et al., 2020). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection took place from February 2020 to September 2020.

2.4. Secondary Analysis (Present Study)

2.4.1. Thematic analysis – identifying home characteristics

A multidisciplinary team with expertise in biomedical and human factors engineering, pharmacy, and qualitative research conducted a thematic analysis of PS1 data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Researchers began by coding two randomly selected transcripts for home characteristics. The researchers independently developed and organized provisional codes before meeting together. The research team then met to discuss the codes they had for each transcript line by line and converged on an initial codebook. The codebook was further refined through a series of meetings to discuss the results of coding new transcripts and to get feedback from a senior researcher (NW). Qualitative research software, NVivo 12 (QSR International), was used to categorize and organize the identified home characteristics. The final codebook was applied to the rest of the PS1 data until each transcript was dual coded. Researchers met regularly to discuss any data that did not fit the existing codes and resolve any disagreements in coding.

2.4.2. Home Persona Development

We used an iterative, multi-stakeholder design process to take the coded home characteristic data and integrate it with design expertise and stakeholder input to form the final home personas. Stakeholder feedback was received through regular meetings with the established PS1 research “core team,” consisting of complex care physicians, researchers, a complex care nurse, a family advocate, and family caregiver. To ensure the quality of our study results, the following rigor techniques were used (1) triangulation of methods, investigators, and data sources, (2) member-checking with family caregivers, (3) critical review from other domain experts, and (4) another data set for negative case review (Devers, 1999; Lockwood et al., 2015; Valdez et al., 2017).

The coded data were reviewed by two researchers (HB, EP) and then consolidated into home summary tables—based on the identified home characteristics reported in 3.2—to capture the “essence” of each home. Examples of details that were included in the home summary tables are: the number and ages of family members, the layout of the home (e.g., presence of stairs, width of hallways, etc.), and what tools or technologies families used and where they were kept. Home summary tables were then used in an affinity diagramming process to identify relationships between different homes represented in the PS1 data.

Four initial home archetypes with mock layouts emerged from this process, representing distinct ways care, people, and space interacted in the data set. Archetypes were discussed with senior researchers (NW, RV) and dimensions around privacy, modifiability and design of the space, and where health-related tasks were done in the home, were identified. Archetypes were then brought to the PS1 research “core” team who provided feedback, advised on archetype naming, and suggested ways of visualizing findings. Researchers (HB, EP) refined the archetypes considering this feedback and developed the home persona dimensions outlined in section 3.4.

To further validate and build the credibility of the archetypes, we reviewed PS2 data to look for potential negative cases (Devers, 1999; Valdez et al., 2017). Two members of the research team (EP, HB) critically reviewed transcripts (n=20) for negative cases of our developed archetypes, meeting regularly to discuss findings. While no negative cases were identified, confirmatory cases informed subsequent archetype revisions.

Concurrent with the validation process, researchers collaborated with a designer to develop exemplar home layouts for each of the four archetypes using AutoDesk Revit (2022), Adobe Illustrator (2022), and Adobe InDesign (2022). Iterative revisions between the designer and researchers (HB, EP) occurred until researchers decided input from the PS1 research “core” team was needed. The PS1 research “core” team provided additional feedback (e.g., home persona names were again discussed and changed, callouts of important data were considered, the visual design of the home personas was critiqued) which was again incorporated into the next home persona design. Additional revisions for clarity and consistency were made iteratively between the designer and researchers (HB, EP, NW) to produce the final home personas.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

PS1 enrolled 30 families, 80% female and 77% non-Hispanic white. The primary caregivers’ age in the study ranged from 20 to 78 years, with an average age of 38 years. The child’s age ranged from 1 to 15 years, with an average age of 7 years. Seven families lived in rural residences, 23 in urban.

PS2 enrolled 20 families, of which 17 provided demographic data. Caregivers were 80% female and 85% white. Their age ranged from 23 to 54 years, with an average age of 35 years. The child’s age ranged from 3 mo. to 5 years, with an average age of 2.3 years. 10 families lived in rural residences, 10 in urban.

3.2. Home Characteristics

We identified seven broad categories of home characteristics (Table 2): 1) the people and pets that are in the home, 2) the layout of the home, 3) where tools and technology are located within the home, 4) where tasks or activities are completed within the home, 5) the aesthetic and 6) location of the home, and 7) the type of home. Dimensions identified for each home characteristic further describe home characterization.

Table 2.

Descriptions of home characteristics and their dimensions.

| Home Characteristic | Description | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| People & Pets | Includes all people and pets that live in the home. Also includes people who regularly visit the home (e.g., son who lives in a different home) or people who visit the home to provide care services. | Family Pets Visitors Care Services (teaching, physical therapy, nursing/caregivers) |

| Spatial Distribution of Tasks | Carrying out tasks within and across specific locations | Medication Preparation Personal Cares Feeding Spending time (play, etc.) |

| Spatial Distribution of Tools and Technology | Storage of tools or technologies in specific spaces of the home for either routine or future use | Medical devices Medications Supply Storage Monitoring devices Transportation tools Organization/Coordination tools |

| Layout | Layout of the home, location of structural components | Location of rooms Proximity Size of space Levels Stairs Physical Modifications |

| Aesthetics | Having the home look a certain way, having it be a nice place to live, not just for care | Decor |

| Location | Physical location of the home as it relates to anything outside of the home (e.g., close to family, a park, hospital, transportation, etc.) | Proximity to resources (hospital, emergency services, schools, etc.) Size of town Safety |

| Type of home | State of the home with regards to when it was built (e.g., old/new), whether it is rented or owned by the family, and the attributes which make the people want to be homeowners or renters (e.g., restrictions associated with modifying the house for convenience). | Home ownership status (rent vs. own) Age of home |

3.3. Home Personas

Four home personas were developed to represent the breadth of home characteristics seen in our data: Multi-level with Centralized Care (“Multi-level”), Customized Home with Designated Care Spaces (“Customized”), Ranch with Communal Care (“Ranch”), and Multi-family Rental with Bedside Care (“Rental”). Each home persona features an exemplary home layout with a key indicating where the child is fed, where their daily care happens, where the medication and medical supplies are stored, where hygiene activities happen, and where the child spends their time. Additionally, pain points describe challenges specific to the home personas and scales represent where the persona falls on three dimensions describing the type of space, further discussed in section 3.4.

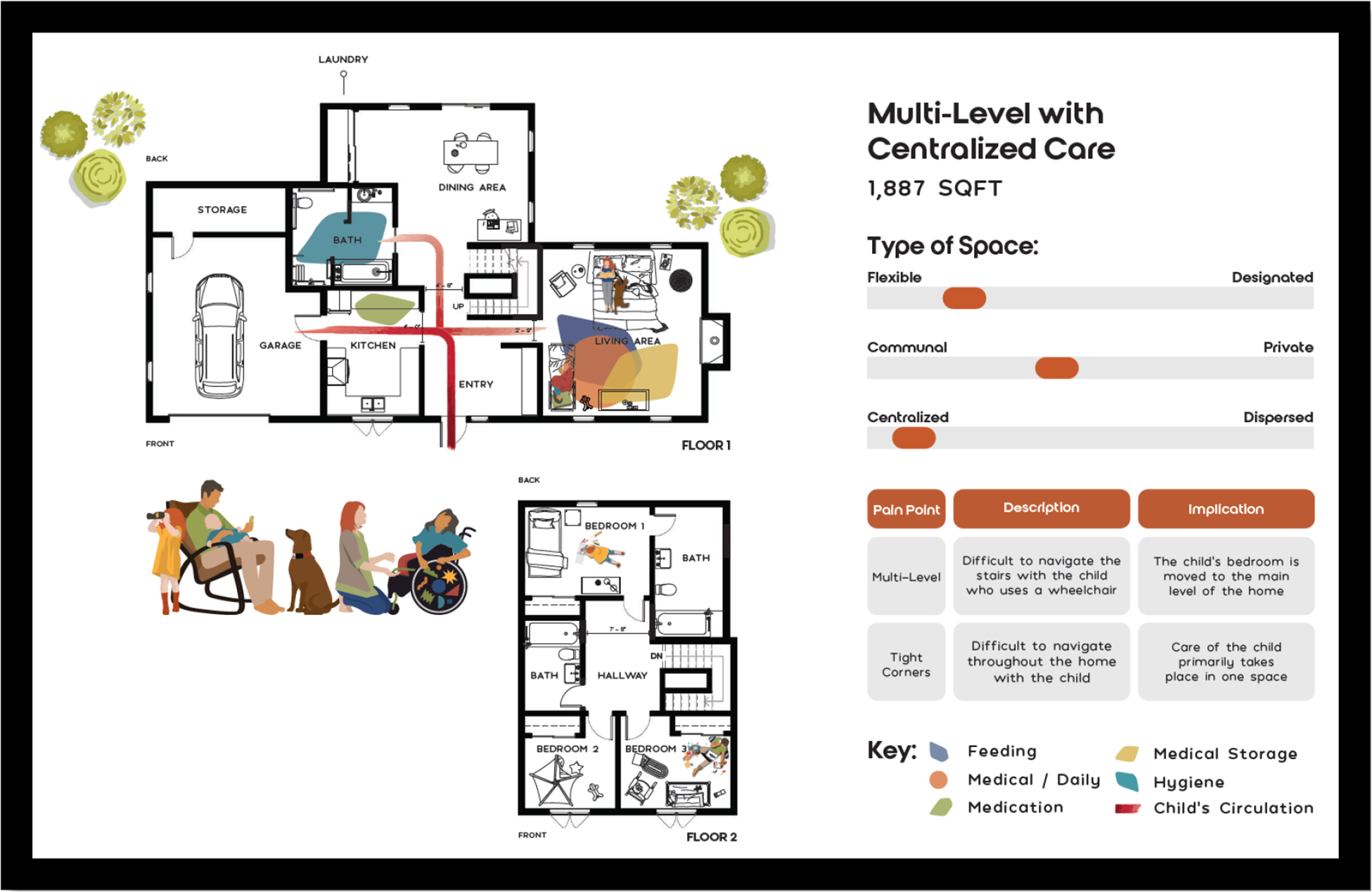

3.3.1. Multi-Level with Centralized Care (“Multi-Level”)

The Multi-level with Centralized Care is an older home characterized by its’ narrow halls, steep stairs, small bathrooms, and tight corners (Figure 1). The key pain points for the family are the tight corners and the stairs, which make it difficult to navigate the child and their wheelchair through the home.

Figure 1.

Multi-Level with Centralized Care persona (“Multi-level”).

As a result, the parents and their child primarily use the first floor and provide care in a singular space, the living room. One family who informed this home persona described how they had to make the living room both their and their child’s bedroom: “yep, [we] pretty much had to … [make] this be our bedroom area, [and the child’s] bedroom area, our living room area… [we] have a two-story house…but we can’t utilize it [second story].”

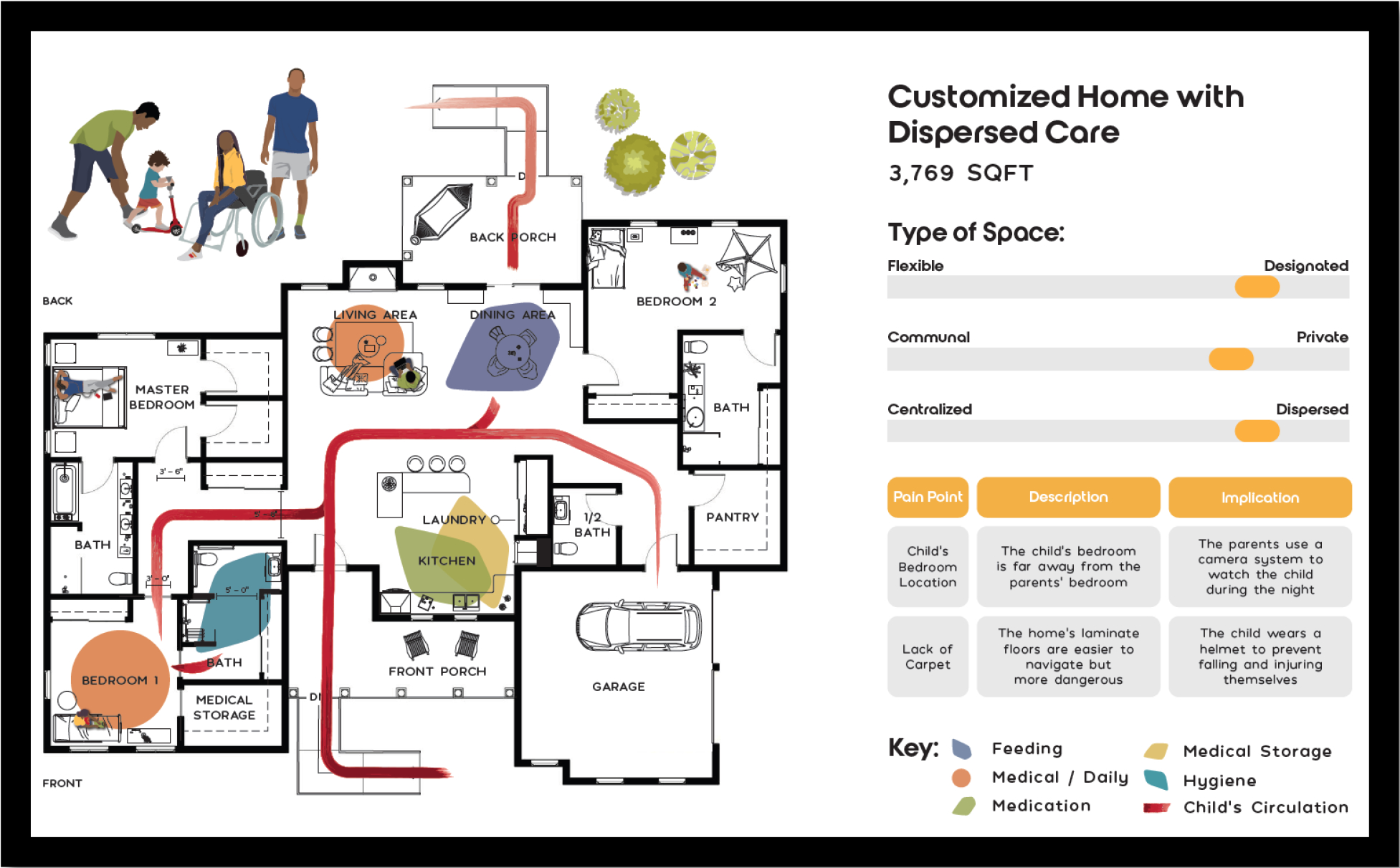

3.3.2. Customized Home with Designated Care Spaces (“Customized”)

The Customized Home with Designated Care Spaces is a home newly designed and built for care by the family (Figure 2). It features wide doorways and halls, a walk-in shower, and lots of storage space for the child’s equipment. The family uses specific spaces for different care activities, such as schooling, physical therapy, and family time. Because care needs are always changing, however, a challenge of this home is that the family is starting to grow out of the spaces that were once “ideal” for their needs.

Figure 2.

Customized Home with Dispersed Care persona (“Customized”).

The main pain points in this home are the distance between the child’s and the parents’ bedroom, which makes monitoring the child difficult and the fact that the floors are laminate which are less cushioned than carpeted floors, despite being easier to clean. One family described this pain point: “[the floor] is harder on them when they’re playing, but for us, we use helmets to help with that.”

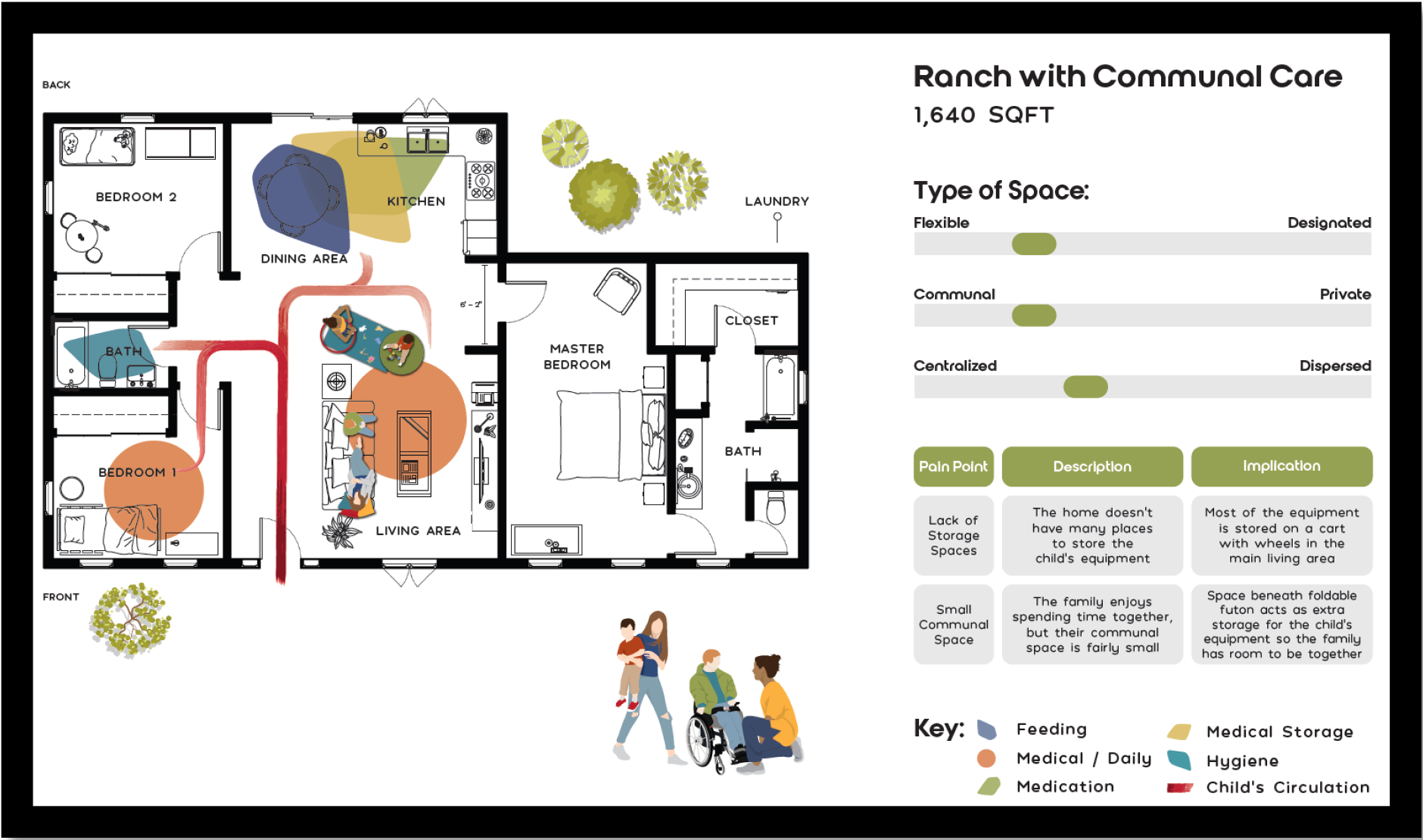

3.3.3. Ranch with Communal Care (“Ranch”)

The Ranch with Communal Care is characterized by its open floor plan and the way it is oriented around “together time.” The child has their own room, where they sleep and receive morning and evening care, but during the day the family prefers to have the child in the living room, a communal space to provide care for the child and spend time together as a family (Figure 3). It’s an older, smaller home with only one level, narrow hallways, and little storage space. The main pain points for this home persona are the small storage space, which poses challenges since the child has a lot of equipment, and small communal space which is very important to the family. A family that informed this home persona said: “ideally, we would have another room just for [child’s] stuff. I don’t like having all [their] equipment in my family room.”

Figure 3.

Ranch with Communal Care persona (“Ranch”).

3.3.4. Multi-Family Rental with Bedside Care (“Rental”)

The Multi-Family Rental with Bedside Care is a small, rented apartment which includes non-family roommates who do not provide care for the child (Figure 4). Because of this, communal spaces are not frequently used and, instead, the child receives almost all their care at the bedside, including bedside bathing. The main pain points for this home persona are the shared living space and the fact that the home is rented, making modifications impossible to undertake. One family that informed this home persona said: “it’s getting the…the housing needs [met], you know. And there’s really no [way], unless you own your own house.”

Figure 4.

Multi-Family Rental with Bedside Care persona (“Rental”).

3.4. Home Persona Dimensions

Three dimensions, conceptualized as continuums, were developed that describe the type of space represented by the home personas: flexible vs. designated, communal vs. private, and centralized vs. dispersed. Figure 5 includes scales comparing all four home personas.

Figure 5.

Cumulative scales describing the four home personas along three dimensions: flexible vs. designated spaces, communal vs. private use, and centralized vs. dispersed care.

3.4.1. How are spaces used? flexible vs. designated spaces

The first dimension identified was how the spaces of the home are used, e.g., using spaces flexibly by repurposing them for different uses or designated spaces for specific uses. Customized is the best example of a home that has mostly designated spaces, given the home was designed specifically for the family and their care needs. The other home personas—Multi-level, Ranch, and Rental—fall more towards the flexible side of the continuum. Multi-level’s living room represents an especially flexible space due to its use for care, feeding, storage, and sleeping.

3.4.2. What is the intention of the space? communal vs. private

The second dimension identified was the intention of the space, e.g., intending to use the space communally or emphasizing privacy in how the space is used. Ranch demonstrates a home that is more communal, with the living room as the primary site for care, mainly to serve the families desire for having ‘together-time.’ Rental is the most private home persona, with the child and caregivers’ use of the space being shaped strongly by the presence of a roommate and the related desire for privacy.

3.4.3. How is care distributed through space? centralized vs. dispersed

The third dimension identified was how care was distributed throughout the spaces of the home, e.g., doing care in one centralized location or dispersing care between various spaces. Multi-level is an example of a home that has centralized care since the child is primarily cared for within the main living space given the restrictions of the layout. This is juxtaposed to the way care is distributed throughout the home in Customized; daily medical care happens in the bedroom and in the living room (depending on the time of day), feeding happens in the dining room, and storage and preparation of medications and food happens in the kitchen.

4. Discussion

Using an iterative, collaborative design process, we developed four distinct home personas that represent distinguishing features of homes of families caring for CMC. By incorporating the expertise of a variety of stakeholders in our home persona design process, e.g., pediatricians, family advocates, and family caregivers, we refined rich primary data into relevant insights about home context. Further, the lack of negative cases found in our review of the second study site (PS2) data implies the insights derived from our PS1 data are likely relevant beyond our study site parameters (Valdez et al., 2017). The resultant home personas can serve as a tool for communicating the home contexts in which care work is performed.

The four resultant home personas—Multi-level, Customized, Ranch, and Rental—are vivid representations of the home contexts of families caring for CMC. Each home persona has a unique home layout within which the exemplar family cares for their child. One key finding of this study is the set of dimensions that describe, for each home persona, the way space is used (and re-used), the intention for the use of the space socially, and how care is distributed throughout the home. The dimensions are represented as continuums, with no home persona representing ultimate extremes. Further, the home personas have unique pain points that describe challenges that arise for families. These home personas can serve as practical tools to convey the essential aspects of the sociotechnical system of the home to designers tasked with designing technologies to fit it.

4.1. Home personas as a practical tool for design

There are a range of design considerations sparked by the four home personas. For example, designing for Multi-level urges the designer to consider how families may adapt spaces for alternative uses. The use of the living room as the main bedroom for the child and parents by the family in Multi-level is one solution to a challenging physical constraint and is a good example of how one’s relationship to their home may change due to illness (Corbin & Strauss, 1985). Further, designing for Multi-level should consider the need for medical supplies and technologies to fit into the main living space of the family, physically and aesthetically. With the living room serving as the site of all the child’s care and feeding, primary medical storage, and the parent’s bedroom, the space must be quite versatile.

Designing for Customized should consider how the use of multiple, spread-out spaces to provide care may influence families’ interactions with technologies. This may require the use of multiple devices, increase the value of remote control, and prompt the use of monitoring technologies. Further, since the family has designed their home to optimize care, Customized prompts designers to consider the disruptive potential of new technologies or interventions. Disruption of the existing care work system could be associated with unintended consequences and a decrease in system resilience leading to error, as other researchers have described (Novak et al., 2020).

Designing for Ranch prompts designers to think about the families who primarily spend their time together in a more limited space. Like in designing for Multi-level, this may make the need for easily storable and aesthetically pleasing (or at least unobtrusive) technologies more salient; however, unlike Multi-level, the child has a separate bedroom, and the family has a designated feeding place in the kitchen/dining area, requiring technology to be easily moved around the home. Ultimately, Ranch conveys the need for technologies to be usable by multiple family members, otherwise termed the care network. This aligns with research that suggests the importance of supporting the distributed care work that occurs in a caregiving network (Ponnala et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2022).

Designing for Rental is most uniquely characterized by the fact that the family cannot use any permanent fixtures or physically modify the space. This implies that designers should consider the way technologies may be modified or adapted to fit the home context, as other researchers have reported, e.g., by using command hooks, Velcro, etc. (Abebe et al., 2020; Barton et al., 2021). Rental also prompts designers to think about the implications of sharing a home with another person, which we already know influences PHIM management by requiring the caregiver to “work with” or “work around” others (Werner et al., 2018). In Rental, the parent and child spend most of their time in the bedroom which could be quite isolating; thus a focus on designing for inclusion may be especially warranted to prevent furthering already documented experiences of isolation and depression among families caring for CMC (Wright-Sexton et al., 2020).

4.2. Home personas as depictions of complex work system interactions

Our results point to the work system interactions that are most salient in describing the home as a place where work is performed by caregivers. Home personas are representations of configurations of the family care work system at the household level – those work system component interactions that are most influential to the process of caring for CMC (Holden et al., 2013). Further, the dimensions that emerged to describe the home personas— (1) having spaces that were used flexibly vs. designated for specific uses, (2) intending to use spaces communally vs. privately, and (3) distributing care throughout the home in a centralized vs. dispersed fashion—represent work system interactions that shape how space is used. For example, the dimension describing how spaces were used on a continuum from flexibly to designated highlights the interaction between the physical and organizational context and the task(s) required to achieve whichever goal the family may be trying to achieve, e.g., schooling. The dimension describing how spaces were used communally vs. privately highlights the interaction between physical and social context. And the final dimension focused on how care is distributed highlights the interaction between the physical and organizational context and the care task(s) and the tool(s) required to complete them.

These results provide a step towards translating descriptive patient ergonomics research into practical tools, addressing the need to advance methods in this emerging field (Holden & Valdez, 2018; Holden & Valdez, 2019; Valdez et al., 2017). While current research on care work in the home offers important insights about different populations and contexts, there is a need for easy-to-understand outputs that can be used in non-academic settings (Werner, Ponnala, et al., 2020). For instance, the home personas reported here could be used by medical device designers to guide early-stage conceptualization through to shaping usability testing of devices to be in more relevant contexts. Home personas could also be used by healthcare providers to develop care plans that are adequately situated in the family’s home context (e.g., a care plan shouldn’t require the use of a tub if the halls are too narrow to access the bathroom via wheelchair). Further, home personas could be used to support families in selecting housing (e.g., during a house or apartment hunt) to promote awareness of certain caregiving tradeoffs inherent to different home layouts. Beyond the use of the home personas themselves, we may have introduced a method that could be used to characterize and communicate other important contexts of the patient work system (e.g., workplace, school, community, etc.) (Holden et al., 2017).

4.3. Considerations for home personas

There are important considerations for the home personas we present here. First, the influence of socioeconomic status in the type, size, and location of the home a family can afford cannot be ignored. As demonstrated in Customized, one family may be able to completely design and build a home for the child’s care; whereas in Rental, the family shares a rented apartment and thus uses one room for the majority of the child’s care. We already know that a disproportionate number of children with medical complexity live in “run-down’ housing and in poverty (Berry et al., 2020) and while it is not possible to draw causality between certain homes and quality of care, the home’s constraints on caregiving may contribute to associations between socio-economic status and health outcomes. Using home personas to describe the diversity of home contexts, devoid of judgement, may prove a valuable method for designing technologies and interventions for socio-economically disadvantaged families.

It is also essential that we consider home personas inside of a broader temporal context. The home personas presented here are single snapshots in time and thus do not represent the distinct ways work system interactions shift over a day, week, month, or year(s). For example, on the short end of the timescale, families may need to adjust when the child has an acute illness or recovers from surgery or when extended family comes into town. Over time, families may make significant modifications to the home (e.g., create a zero-entry shower) because they have the funding to or because their needs have changed as the child has grown (e.g., the child is heavier so they can no longer lift the child safely into the bathtub). As the child grows, their care needs change and, consequently, families must adapt their care work system.

Finally, we must consider isolation with regards to the home personas presented here. There are interesting implications for each of the home personas with respect to how the child is integrated into the home and the family. For Multi-level and Ranch, a heavy emphasis is placed on family and together time; although, for Multi-level this may be forced by the physical environment (i.e. stairs). In Customized, the home is designed to have distinct spaces for certain activities, which introduces more physical distance between family members. This distance may create the experience of either isolation or, conversely, autonomy depending on the child’s cognitive capabilities, age, personality, etc. In Rental, despite the caregiver and child’s proximity to each other, there may be an experience, for both the parent and child, of being isolated from other family given the small, shared living room. Further, the caregiver may not feel as if there is sufficient space for them, which has the potential to contribute to the disproportionately poor mental health of family caregivers (Berry et al., 2020). Designing technologies and interventions with these considerations in mind may support families to better address or even prevent feelings of isolation.

4.4. Limitations

A few key limitations of this study should be considered. First, the sample of caregivers is primarily made up of white women. However, our data reflects the significant proportion of care that is done by women (Sharma et al., 2016) as well as local race/ethnicity demographics for both PS1 and PS2, respectively. The inclusion of a second study site expanded the geographic and cultural settings; however, other populations should be included in future studies to offer unique insights into home contexts (e.g., families who are non-English speaking, divorced, sexual and gender minorities, extremely urban or rural, etc.). Consequently, the breadth of home contexts described in this study should not be considered exhaustive, but rather a base on which to build.

Second, it is important to consider the impact of self-selection bias on the creation of the home personas. Our data (PS1) reflects the home contexts of families that were open to sharing about and having researchers enter their homes. Those who chose not to participate in the study may have commonalities that were thus not represented in the home personas. For example, a family with a particularly messy environment may have felt embarrassed and chosen not to participate. Or a family who was also caring for an ageing older adult may have wanted to maintain more privacy than they felt they could achieve in participating. In future recruitment efforts, it may be pertinent to offer participants who decline participation in the primary study an opportunity to complete a brief survey that captures less-sensitive data. This could allow us to better understand who declines these kinds of home-based or caregiving-network focused studies.

Further, as discussed in section 4.3, our analysis of the home context is only one ‘snapshot’ in time. Although some caregivers offered perspectives about their previous homes or their ideas for future modifications of their current home, the full dynamic nature of the home context is not captured by this analysis. A longitudinal study of the home as a caregiving context might offer unique insight into how these families adapt their home over time as they develop expertise in caring for their child.

4.5. Conclusion

To date, the field of Patient Ergonomics has advanced our understanding of the ways in which the home shapes self-management of one’s chronic conditions (Holden et al., 2015; Werner et al., 2018). The present study builds on this foundation by providing a mechanism for distilling rich descriptions of the PWS into brief yet informative design tools. The home personas presented here can serve as practical tools to convey the essential aspects of the home context to designers tasked with designing technologies and interventions to fit it.

Table 1.

Demographics of children and their caregivers.

| Caregiver characteristic | PS1 (N=30) | PS2 (N=20)* |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean; range) | 38; 20–78 | 35; 23–54 |

| Female gender (n, %) | 24 (80) | 16 (80) |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 23 (77) | 17 (85) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 2 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Rural residence (n, %) | 7 (23) | 10 (50) |

| Child’s characteristic | ||

| Age in years (mean; range) | 7.0; 1–15 | 2.3; 0.25–5** |

| Female gender (n, %) | 13 (43) | 2 (25)*** |

PS2 enrolled 20 caregivers, however only 17 replied to the demographic survey;

N=10;

N=8 for PS2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under UA6MC31101 Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs Research Network and by KL2 grant KL2TR002374 from the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 1UL1TR002373. Additionally, this work was funded through the NIH, National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) (R21NR017991). The information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, NIH, and the U.S. Government.

The authors would like to acknowledge the many families who invited us into their homes and lives to share their experiences, insights, and expertise. We hope this work can be used to improve your lives and the lives of those who will come after you.

Appendix: Interview Guide Questions

- Can you start out by telling me who else lives here with you (without using any names)?

- Children? – ask about ages

- Pets?

- We would like to learn about the types of activities you have to perform daily to provide care for your [child’s relationship]. Can you talk me through and show me what you do on a typical day to provide care to your [child’s relationship] in your home and where you do it?

- Are there different routines on different days or of different people? (e.g., mom vs dad days?)

- NOTE: Use the prompts below for spaces, tools/tech, and communication.

- In what spaces in the home do you perform care activities for your [child’s relationship]?

- Can you show me those areas? (if not already showing)

- What objects, items, technologies, supplies, devices are helpful to you here?

- Are there other things [such as medical devices, technologies, supplies, tools – will refer to collectively as ‘X’ thing(s) moving forward in the guide] that I haven’t seen already that you use to help you provide care or organize care to your [child’s relationship]?

- Have you created anything to help you provide or manage care to your [child’s relationship]? (e.g., calendar, note pad, bulletin board)

- Who else helps care for your [child’s relationship]?

- What kinds of things do they do?

- What kinds of things don’t they do and why (e.g., don’t feed because never received training)?

- How are daily schedules decided and who plans them?

- How do you coordinate with them?

- What support do you get from outside services and resources such as nursing, social work, and respite?

- Do you use any community resources/support?

- Does anyone help you coordinate care or services?

- In what ways do you use the internet in caring for your child?

- Are there any blogs/message boards/websites you use or find useful?

- Are you in any support groups (i.e., Facebook or other virtual?)

How do you communicate/share information with others that help you provide care to your [child’s relationship]?

- Where else does your child spend a lot of time (i.e., at school, at grandma’s)?

- What do you do to make sure they are successful at these places?

- Have you had to care for your [child’s relationship] in a place other than your home?

- What were the situations which led to spending time away from home? (e.g., Travel? Appointments?)

- How did you replicate your home environment? How did you manage differences to the layout of the environment?

- What was it like after time away from home?

- How did you manage changes to your routine? What went well? What was more challenging?

- Closing Questions

- What would an ideal day be for you and your family?

- What does a good/bad day look like?

- If you could have anything to help you, what’s the one thing that would make your life easier?

- What would ‘X’ thing(s) be helpful for?

- How could you have been better prepared to care for your child?

- What’s something you’ve learned that you wish you knew earlier, in caring for your child?

- How would you complete the following sentence? A healthy life for my child includes ________________.

- If you could have three wishes, what would you wish for?

- Is there anything else you want to show me?

- Is there anything I forgot to ask about?

Additional Prompts

Space

Why is the space arranged in this way?

Have you had to make any changes to the space?

Is there anything you find challenging about the space?

Is there anything about the space that makes providing care easier?

Are there certain things about the layout, space, or physical environment of your home that makes providing care easier or more challenging? (e.g., stairs; divided spaces rather than open layout)

Tools & Technology

Note: dig in to find out about adaptations/self-design/workarounds/emergency use/breakdowns

How do you use ‘X thing’?

Has ‘X thing’ been modified at all?

How often do you use ‘X thing’?

How do you know when to use ‘X thing’?

What kinds of challenges do you experience using ‘X thing’?

How do ‘X things’ make life easier?

How did you learn to use the ‘X thing’? Did someone teach you?

How did you find out about “X thing” ?

What do you do if something goes wrong with ‘X thing’? How do you get help when needed?

Do others use ‘X thing’?

What about ‘X thing’ do you find challenging? Easy?

Communication/Information Sharing

How do you get information from one caregiver to the next? How is the [process/thing] useful? How could it be improved?

What information needs to be passed on?

How do you know or communicate with one another that a task is completed or not? (e.g. a medication is given, a feed is completed, bath is done, supplies are ordered, etc)

Do you use anything to help you organize or plan? Why did you choose that? Have you adapted it in any way? How has it been useful? How could it be improved?

How do you remember what to do when?

If you could have any feature you want in a technology, what would you ask for?

Do you use any technologies (e.g., pc, phone, apps) to help plan, organize, communicate, share information or assist with caring for your [child’s relationship]?

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Abebe E, Scanlon MC, Lee KJ, & Chui MA (2020, Sep). What do family caregivers do when managing medications for their children with medical complexity? Appl Ergon, 87, 103108. 10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton HJ, Coller RJ, Loganathar S, Singhe N, Ehlenbach ML, Katz B, Warner G, Kelly MM, & Werner NE (2021). Medical Device Workarounds in Providing Care for Children With Medical Complexity in the Home. Pediatrics, 147(5), e2020019513. 10.1542/peds.2020-019513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton HJ, Loganathar S, Singhe N, Ehlenbach ML, Katz B, Coller RJ, & Werner NE (2020). Exploring Work System Adaptations in Providing Care for Children with Medical Complexity in the Home. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 64(1), 675–679. 10.1177/1071181320641156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JG, Agrawal R, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Risko W, Hall M, Casey P, Gordon J, & Srivastava R (2011, Aug). Characteristics of hospitalizations for patients who use a structured clinical care program for children with medical complexity. J Pediatr, 159(2), 284–290. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JG, Harris D, Coller RJ, Chung PJ, Rodean J, Macy M, & Linares DE (2020). The Interwoven Nature of Medical and Social Complexity in US Children. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 891–893. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, & Grumbach K (2002). Improving Primary Care for Patients With Chronic Illness. JAMA, 288(14), 1775–1779. 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, Gurses AP, Alvarado CJ, Smith M, & Flatley Brennan P (2006, Dec). Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care, 15 Suppl 1, i50–58. 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SK, Simon TD, & Srivastava R (2011, Mar). Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics, 127(3), 529–538. 10.1542/peds.2010-0910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, & Strauss A (1985). Managing chronic illness at home: Three lines of work. Qualitative Sociology, 8, 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Devers KJ (1999, Dec). How will we know “good” qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res, 34(5 Pt 2), 1153–1188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doutcheva N, Thomas H, Parks R, Coller R, & Werner N (2019). Homes of children with medical complexity as a complex work system: outcomes associated with interactions in the physical environment. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 63(1), 753–757. 10.1177/1071181319631484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friess E (2012). Personas and decision making in the design process: an ethnographic case study. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Jackson JD, & Wilkins CH (2020). The urgency of justice in research: Beyond COVID-19. Trends in molecular medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, Hoonakker P, Hundt AS, Ozok AA, & Rivera-Rodriguez AJ (2013). SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics, 56(11), 1669–1686. 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Cornet VP, & Valdez RS (2020, Jan). Patient ergonomics: 10-year mapping review of patient-centered human factors. Appl Ergon, 82, 102972. 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Schubert CC, & Mickelson RS (2015). The patient work system: an analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. Applied ergonomics, 47, 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, & Valdez RS (2018). Town Hall on Patient-Centered Human Factors and Ergonomics. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 62(1), 465–468. 10.1177/1541931218621106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, & Valdez RS (2019). 2019 town hall on human factors and ergonomics for patient work. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, [Google Scholar]

- Holden RJ, Valdez RS, Schubert CC, Thompson MJ, & Hundt AS (2017, Jan). Macroergonomic factors in the patient work system: examining the context of patients with chronic illness. Ergonomics, 60(1), 26–43. 10.1080/00140139.2016.1168529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzblatt K, & Beyer H (2016). Contextual Design, Second Edition: Design for Life. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliff AF, Hoonakker P, Ponto K, Tredinnick R, Casper G, Martell T, & Werner NE (2020). The desktop, or the top of the desk? The relative usefulness of household features for personal health information management. Applied ergonomics, 82, 102912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood C, Munn Z, & Porritt K (2015, Sep). Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc, 13(3), 179–187. 10.1097/xeb.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskiewicz T, & Kozar KA (2011). Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Design studies, 32(5), 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Moen A, & Brennan PF (2005, Nov-Dec). Health@Home: the work of health information management in the household (HIMH): implications for consumer health informatics (CHI) innovations. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 12(6), 648–656. 10.1197/jamia.M1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2011). Health Care Comes Home: The Human Factors. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/13149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novak LL, Baum HB, Gray MH, Unertl KM, Tippey KG, Simpson CL, Uskavitch JR, & Anders SH (2020). Everyday objects and spaces: How they afford resilience in diabetes routines. Applied ergonomics, 88, 103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or CKL, Valdez RS, Casper GR, Carayon P, Burke LJ, Brennan PF, & Karsh B-T (2008). Human Factors and Ergonomic Concerns and Future Considerations for Consumer Health Information Technology in Home Nursing Care. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 52(12), 850–854. 10.1177/154193120805201219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parks R, Doutcheva N, Umachandran D, Singhe N, Noejovich S, Ehlenbach M, Warner G, Nacht C, Kelly M, Coller R, & Werner NE (2021). Identifying Tools and Technology Barriers to In-Home Care for Children with Medical Complexity. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 65(1), 510–514. 10.1177/1071181321651214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnala S, Block L, Lingg AJ, Kind AJ, & Werner NE (2020). Conceptualizing caregiving activities for persons with dementia (PwD) through a patient work lens. Applied ergonomics, 85, 103070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt J, & Adlin T (2010). The persona lifecycle: keeping people in mind throughout product design. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, & Grover S (2016, Mar 22). Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J Psychiatry, 6(1), 7–17. 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez RS, & Holden RJ (2016). Health Care Human Factors/Ergonomics Fieldwork in Home and Community Settings. Ergonomics in Design, 24(4), 4–9. 10.1177/1064804615622111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez RS, Lunsford C, Bae J, Letzkus LC, & Keim-Malpass J (2020, Jan 23). Self-Management Characterization for Families of Children With Medical Complexity and Their Social Networks: Protocol for a Qualitative Assessment. JMIR Res Protoc, 9(1), e14810. 10.2196/14810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez RS, McGuire KM, & Rivera AJ (2017, Jul). Qualitative ergonomics/human factors research in health care: Current state and future directions. Appl Ergon, 62, 43–71. 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Fleischman A, Warner G, Barton HJ, Kelly MM, Ehlenbach ML, Wagner T, Finesilver S, Katz BJ, Howell KD, Nacht CL, Scheer N, & Coller RJ (2022, Jun 7). Feasibility Testing of Tubes@HOME: A Mobile Application to Support Family-Delivered Enteral Care. Hosp Pediatr. 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Jolliff AF, Casper G, Martell T, & Ponto K (2018). Home is where the head is: a distributed cognition account of personal health information management in the home among those with chronic illness. Ergonomics, 61(8), 1065–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Ponnala S, Doutcheva N, & Holden RJ (2020). Human factors/ergonomics work system analysis of patient work: state of the science and future directions. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 33(Supplement_1), 60–71. 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Tong M, Nathan-Roberts D, Arnott-Smith C, Tredinnick R, Ponto K, Melles M, & Hoonakker P (2020). A Sociotechnical Systems Approach Toward Tailored Design for Personal Health Information Management. Patient Exp J, 7(1), 75–83. 10.35680/2372-0247.1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright-Sexton LA, Compretta CE, Blackshear C, & Henderson CM (2020, Aug). Isolation in Parents and Providers of Children With Chronic Critical Illness. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 21(8), e530–e537. 10.1097/pcc.0000000000002344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas-Cabán T, & Dixon BE (2010). Considerations for the design of safe and effective consumer health IT applications in the home. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19(Suppl 3), i61–i67. 10.1136/qshc.2010.041897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]