Abstract

Meningioma is the most common central nervous system (CNS) tumor. In recent decades, several efforts have been made to eradicate this disease. Surgery and radiotherapy remain the standard treatment options for these tumors. Drug therapy comes to play its role when both surgery and radiotherapy fail to treat the tumor. This mostly happens when the tumors are close to vital brain structures and are nonbenign. Although a wide variety of chemotherapeutic drugs and molecular targeted drugs such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, alkylating agents, endocrine drugs, interferon, and targeted molecular pathway inhibitors have been studied, the roles of numerous drugs remain unexplored. Recent interest is growing toward studying and engineering exosomes for the treatment of different types of cancer including meningioma. The latest studies have shown the involvement of exosomes in the theragnostic of various cancers such as the lung and pancreas in the form of biomarkers, drug delivery vehicles, and vaccines. Proper attention to this new emerging technology can be a boon in finding the consistent treatment of meningioma.

Keywords: Meningioma, Targeted therapy, Therapeutic drugs, Exosome-based targeted therapy, Exosome drug delivery system, Exosome-based vaccines

Introduction

Meningiomas are tumors arising from the outer membrane of the brain and spinal cord. Primarily, these tumors are formed from meningothelial arachnoid cells, but their presence has also been reported in the ventricles of the CNS and extracranial organs like lungs. Currently, the approximate incidence of meningioma is 7.86 cases per 100,000 people per year confirming it as a dangerous disease. As per the current WHO categorization, around 80% of meningiomas are benign (grade I), while 20% are atypical (grade II) or anaplastic (grade III). Almost 90% of tumors are intracranial while 10% are detected in the spinal area [1]. These tumors are primarily observed in people of the elderly age group (having an age more than 65 years), but the incidence is also increasing in adults [2]. The incidence of meningioma in adults (aged 15–39 years) is approximately 16% of all intracranial tumors. Meningioma is rare in children that account for 0.4–4.1% of all pediatric tumors [3]. Pediatric meningioma occurs equally in males and females; however, in adulthood, meningioma is more prevalent in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1 [4]. Radiation [5], diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and smoking are other risk factors for meningioma, the last risk factor being contradictory [6, 7]. The tumor can be identified using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When the tumor is small, highly calcified, and asymptomatic, patients may not need any treatment in contrast to patients having large symptomatic tumors causing epilepsy or neurologic deficit. Although surgical excision can cure 70–80% of meningiomas, grade II and grade III meningiomas are not completely removed and can recur [8–10]. As a result, following resection, radiation therapy or stereotactic radiation surgery is done to treat meningioma, either acting as a monotherapy or as an adjuvant therapy [11]. When surgery and radiation therapy fail to give the desired results and the tumor continues to grow, this leads to recurrent meningiomas, which are candidates for systemic therapy. Radiosurgery is also disadvantageous as it causes neurotoxicity and injury to the adjacent vascular and cranial nerves, again increasing the dependency on systemic therapy. Over the last decade, many drugs have been tested for meningioma. Systemic therapy includes chemotherapy (conventional or cytotoxic therapy), hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, and immune therapy in which numerous small-molecule drugs are intended to target cancerous cells without harming normal cells.

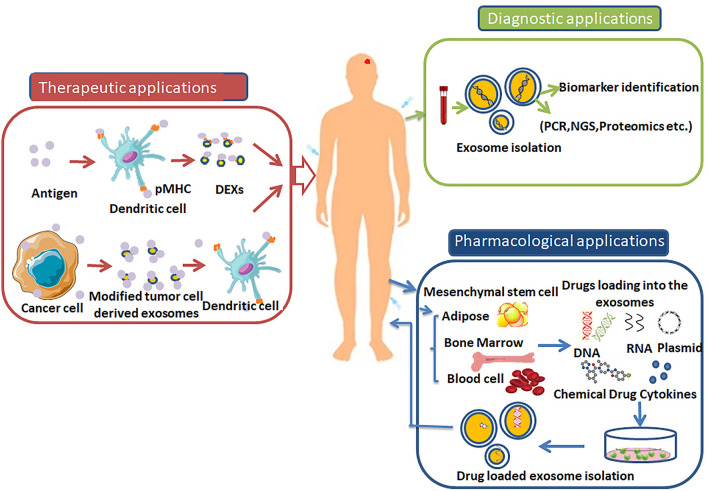

Tumor mass is mostly occupied by the TME (tumor microenvironment), which constitutes the stroma of the tumor [12]. Exosomes are small extracellular vesicles having 30 to 150 nm diameter. They are involved in cell-to-cell signaling [13]. They can transfer a cargo of proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids from donor cells to recipient cells. Exosomes can be produced by all kinds of cells, i.e., diseased and normal cell types, but their increased production has been reported in diseased conditions. They are also found as good diagnostic markers for diseases, especially cancers like meningioma. Exosomes influence the TME component cells, which leads to the progression of cancers (meningioma). Since meningioma is highly vascularized cancer, angiogenesis plays an important role in their growth. Exosomes also affect angiogenesis in oral squamous cell carcinoma [14], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [15], lung cancer [16], and hepatocellular carcinoma [17]. Exosomes and tumor growth are also correlated. Tumor growth involves three main elements: cell-cycle progression, inhibition of apoptosis, and glycolysis [18–22]. Exosomes control growth rate, as has been seen in lung cancer [23], pancreatic cancer [24], colorectal cancer [25], and nonsmall-cell lung cancer [26]. Studies have also shown the involvement of exosomes in metastasis. Metastasis denotes cancer migration and invasion. Both these processes are affected by EMT (epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition) [27]. During EMT-induced metastasis, E-cadherin decreases while N-cadherin increases inside the cancerous cells [28, 29]. Reports on prostate [30], ovarian [31], and breast cancer [32] have shown the role of exosomes in cancer metastasis. In addition to EMT, MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases) are also related to cancer metastasis, but this field is still in its infancy [33–37]. In addition, these nanovesicles are also involved in drug resistance and immune escape. Exosomes genotypically and phenotypically resemble their parent cells, can protect themselves from their surroundings, and are present in all body liquids; accordingly, they are used in liquid biopsies. Although in the past few years, different research groups have published papers emphasizing on the role of engineered exosomes in treating various type of cancers yet their use in detection and treatment of meningioma is new. Undoubtedly, now also continuous work is going on in this area. When it particularly comes to brain tumors, exosomes have also been observed as good therapeutic delivery agents. They can cross the blood–brain barrier, allowing them to deliver biological molecules or pharmaceutical medications to brain tumors. Exosomes are nonviable and, hence, better than transplanted cells. They are good because of biosafety reasons. Exosomes are carriers which deliver therapeutic molecules, while their administration also elicits intrinsic therapeutic effects. Exosomes, derived from dendritic cells, carry machinery including antigenic material and major histocompatibility complex peptide complexes for the antigen presentation process of the immune response; hence, they can be used as noncellular antigens for developing vaccines against infectious diseases or tumors. After antigen presentation, they induce T-cell activation, thereby killing the tumor cells. The present review sheds light on developing new, promising systemic therapies, targeted drug delivery by exosomes, and cell-free vaccine development using exosomes against meningioma.

Targeting therapies

Current knowledge of meningioma-associated growth factors, as well as their receptors and signaling pathways, is not sufficient [38–42]. Deregulation of the signaling pathways is considered one of the major causes of the neoplastic transformation of meningioma. There are reports on meningioma cells showing abnormal expression of critical signaling molecules, resulting in uncontrolled cell division, differentiation, migration, survival, and angiogenesis [43, 44]. Recently, efforts have been made to develop potential inhibitors of several targeted agents. Today, the identification of therapeutic targets and the selection of such agents are major challenges. Most anti-growth factor receptor strategies involve small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies against EGFR and VEGFR. Other potential inhibitors are PDGFR inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, integrin path inhibitors, etc. Drugs used in target therapy are listed in the tables below.

Some common cytotoxic agents

Common cytotoxic agents include temozolomide, irinotecan, hydroxyl urea, trabectedin, cyclophosphamide doxorubicin, curcumin, AKBA, and vincristine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of some common cytotoxic agents used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytotoxic agents | ||||

| Temozolomide (today) | Imidazotetrazine, orally administered | Alkylated agent | Temozolomide for treatment-resistant recurrent meningioma; phase II trial: no clinical efficacy shown | [45] |

| Irinotecan (Camptosar) | C33H38N4O6 plant alkaloid, intravenously administered | Topoisomerase 1 inhibitor | Irinotecan has growth-inhibitory effects in meningiomas both in vitro and in vivo; phase II trial: no clinical efficacy shown | [46] |

| Hydroxyurea | CH4N2O2, orally administered | Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor | Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas; phase I trials: inhibition of primary human meningioma cells in culture and meningioma transplants by induction of the apoptotic pathway; phase II trial: mixed results | [47] |

| Trabectedin (Yondalis) | C39H43N3O11S, intravenous infusion | Mechanism unclear; believed to make conformational changes in DNA strands, causing inhibition of transcription factor binding | Trabectedin has promising antineoplastic activity in high-grade meningioma | [48] |

| Cyclophosphamide | C7H15Cl2N2O2P, orally administered | Synthetic nitrogen mustard alkylating agent | Medical management of meningioma in the era of precision medicine | [49] |

| Bacteria-derived agents | ||||

| Doxorubicin | C27H29NO11, anthracycline antibiotic, intravenous | Topoisomerase 2 inhibitor | Recurrent meningioma of the cervical spine, successfully treated with liposomal doxorubicin | [50] |

| Plant-derived agents | ||||

| Curcumin | C21H20O6, orally administered | Interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins | Curcumin has antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity in human meningiomas; preclinical trial: cell culture/in vitro | [51] |

| AKBA | Pentacyclic triterpene | Induction of apoptosis; anti-inflammatory | Cytotoxic action of acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA) on meningioma cells; preclinical trial: cell culture/in vitro | [52] |

| Vincristine | C46H56N4O10, intravenously administered at weekly intervals | Binds to tubulin, thus stopping the polymerization of tubulin dimers; microtubules make cells unable to replicate during metaphase, inducing apoptosis | Adjuvant combined modality therapy for malignant meningiomas | [53] |

Pathway inhibitors

EGFR inhibitors

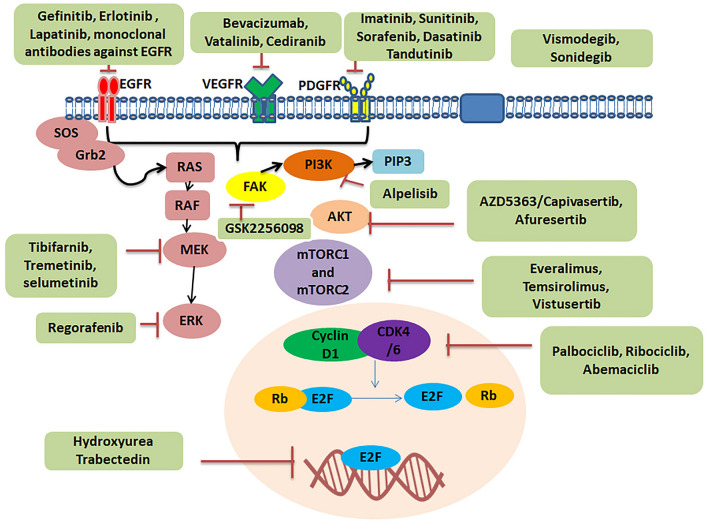

EGFR is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase also called HER1 and ERBB1 [54]. It belongs to the ERBB family. Extracellular ligands such as epidermal growth factor, heparin-binding EGF, and transforming growth factor-α bind to EGFR [55]. On binding, EGFR dimerizes either with itself or with ERBB family receptors. Dimerization causes transphosphorylation of the C-terminal domain, activating the downstream signaling cascades and various physiological processes. The downstream signaling pathways include PI3K/AKT/mTOR, RAS/RAF/ERK, and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathways. Expression of EGFR is seen in 60% of meningiomas [56]. According to a study, EGF and TGFα, by inducing meningioma cell growth [57, 58], activate the EGFR pathway. Gefitinib, erlotinib, and lapatinib are important examples of these types of inhibitors (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of drugs used in target therapy of meningioma including EGFR Inhibitors, Platelet-derived growth factor inhibitors, Anti-angiogenesis drugs, Pi3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway inhibitor, Rb signaling pathway inhibitor, Protein kinase C inhibitors, RAF/MEK/ERK Inhibitors and Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, FAK inhibitors, and Integrin PI3K/Akt pathway

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibitors

There are four members in the PDGF family, namely, PDGFA, PDGFB, PDGFC, and PDGFD. This family has two types of receptors, i.e., alpha-receptor and beta-receptor. When PDGF binds to the receptor, it activates and cross-phosphorylates tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain. This leads to the activation of the PI3K, Jak family kinase, MAPK, Src family kinase, and phospholipase C-gamma signal transduction pathways. These ligands, along with their receptors, have long been connected with tumorigenesis and may play a significant role in meningioma formation and progression. PDGF and its receptors are expressed in meningioma [59]. Studies revealed that PDGF was more highly expressed in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas than in benign meningiomas [60]. It was seen that supplementation of PDGF-BB antibody increased the proliferation of meningioma cells, while the addition of anti-PDGF-BB produced the opposite effect [61]. Examples include imatinib, sunitinib, sorafenib, dasatinib, and tandutinib.

Anti-angiogenesis

Angiogenesis contributes to tumorigenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis. VEGF is involved in the angiogenetic process and responsible for cell migration, endothelial cell proliferation, extracellular matrix degradation, and expression of proangiogenic factors (matrix metalloproteinase-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, urokinase plasminogen activator, and its receptor). Hypoxia, acidosis, and a variety of growth factors such as EGF, PDGF, HGF, c-kit, and their downstream signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt and Ras/MAPK) enhance the expression of VEGF. VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 are two types of VEGF-A receptors. Inhibition of cancer-related blood arteries is an essential therapeutic approach. Cancer cells, including meningioma cells, have the property of high vascularization. These blood vessels supply nutrition to the tumor cells, thereby promoting their growth. If this supply is hampered, it could be therapeutically beneficial. Studies found that an antiangiogenic fumagillin analog suppressed the growth of benign and malignant meningioma in xenograft models (TNP 470). Meningioma expresses VGFR, and its expression is higher in atypical and malignant meningiomas than in benign meningioma [61]. Bevacizumab, vatalinib, and cediranib are examples.

Pi3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitors

Phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol and active downstream components is catalyzed by PI3Ks, which are lipid kinases found inside cells. The main functions of PI3Ks include cell survival, cell cycle, protein translation, and metabolism. There are three types of PI3K: PI3K I, PI3K II, and PI3K III, which function to produce phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphates from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphates. According to the membrane receptors that activate it, RTK, and G protein-coupled receptor class, PI3K I is separated into two subfamilies, IA and IB [62]. Class IA PI3Ks consists of two subunits: subunit p85 and subunit p110, whereby p85 is the regulatory subunit, while subunit p110 is the catalytic subunit. There are three isoforms of p85, namely, p85α, p85β, and p55γ, encoded by PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3 genes, respectively. Similarly, p110 has three isoforms p110α, p110β, and p110γ, encoded by genes PIK3CA, PIK3CB, and PIK3CD, respectively. When specific ligands bind to RTK, conformation changes in p85 of class IA occur, which activates the catalytic subunit p110 leading to the transformation of PIP2 to PIP3. This activates Akt and the mTORC1 signaling pathway, which ultimately induces protein translation. Everolimus, temsirolimus, vistusertib, alpelisib, afuresertib, and AZD5363 are important examples.

Rb signaling pathway inhibitors

G1- to S-phase cell-cycle transition is controlled by the Rb signaling pathway which leads to the regulation of DNA replication and cell division [63, 64]. CDK4 and CDK6 are kinases with similar amino-acid sequences and roles. They both interact with cyclin D and influence Rb protein phosphorylation [65]. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways PI3K/AKT/mTOR, nuclear factor κb, Wnt, JAK/STAT, and JAK/STAT stimulate cyclin D, leading it to interact with CDK4/6. As a result, CDK4/6 phosphorylates Rb. On phosphorylation, the E2F transcription factor separates from Rb, activating E2F and G1 target genes [66, 67]. In the case of higher-grade meningiomas, genetic alterations of genes encoding these proteins are found [68].

Protein kinase C, RAF/MEK/ERK inhibitors

When ligands such as EGF and PDGF bind to their receptors, tyrosine kinases become autophosphorylated on the cytoplasmic side of receptors. Subsequently, grb2 and sos proteins come close to the plasma membrane. Ras proteins, which are small GTPases, become attenuated, which further activates downstream elements of signal transduction pathways such as Raf, MEK 1, and ERK. These factors phosphorylate various transcription factors. Studies have shown that MEK1 inhibitors suppress MAPK activity in meningioma cell culture; hence, there is less inhibition, leading to changes in growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [69]. Tipifarnib, trametinib, and selumetinib are important such inhibitors.

Hedgehog pathway inhibitors

When the hedgehog ligand binds to the protein patched homolog-1, it causes PTCH1 to be internalized and degraded. It causes SMO protein to be suppressed by PTCH1. SMO then interacts with the fused homologous suppressor (SUFU). This interaction elicits the translocation of the zinc finger protein GL1 to the nucleus, which activates target genes. Examples are vismodegib and sonidegib.

FAK inhibition

In vivo and in vitro studies showed sensitivity for FAK inhibition in cells in the case of NF2-mutant tumors such as serous ovarian carcinoma and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Its widespread inhibitor is GSK2256098 (Fig. 1) [70, 71].

Integrin PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitors

The PI3K/Akt pathway is activated when integrin proteins are activated. The downstream effectors of PI3K/Akt are associated with various cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, and proliferation of cells. Integrins are also associated with FAK and ILK at the downstream signaling cascade level.

Integrin inhibitor

Cilengitide is a pentapeptide and an integrin inhibitor. Cilengitide mimics the Arg–Gly–Asp (RGD) binding site and inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells, which are critical in tumor neoangiogenesis. Studies have shown higher expression of integrins in brain tumors, thus indicating that cilengitide inhibition of integrins prevents tumor growth (Table 2) [72].

Table 2.

Details of some common signaling pathway inhibitors used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR antagonists | ||||||||

| Gefitinib (Iressa) | It is an anilinoquinazoline with anticancer activity, orally administered | It competes with ATP for binding to the EGFR’s tyrosine kinase domain, inhibiting receptor autophosphorylation and signal transmission; it is also in charge of stopping the cell cycle and preventing angiogenesis | The study showed its involvement in the treatment of meningioma as an EGFR antagonist; phase: no survival benefit shown | [73] | ||||

| Erlotin ib (Tarceva) | C22H23N3O4 is a quinazoline derivative with anticancer activity, orally given | Similar to gefitinib, it competes with ATP binding to the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR, thereby inhibiting autophosphorylation of EGFR and blocking signal transduction | Its use in meningioma treatment is underway; phase II: no survival benefit shown | [73] | ||||

| Lapatinib | C43H42ClFN4O10S3 is a small molecule and a dual EGFR/ErbB2 inhibitor, as shown by preclinical and clinical data, orally given | EGFR antagonist | Effect of lapatinib on meningioma growth in adults with neurofibromatosis type 2 revealed anticancer activity against schwannomas; it is also hypothesized to have growth-inhibitory effects on meningiomas (Fig. 1) | [74] | ||||

| Monoclonal antibodies, humanized monoclonal antibodies of EGFR | ||||||||

| Cetuximab | Fv region of a murine anti-EGFR antibody with human IgG1 heavy and kappa light chain constant regions | By binding to EGFR on a cancer cell, cetuximab blocks EGF from binding (activation); this stops the cell from continuing the pathway that promotes cell division and growth, effectively stopping cancer by stopping the cancerous cells from growing and multiplying | Assessment of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in human meningioma | [75] | ||||

| Panitumumab | ABX-EGF is a fully human monoclonal antibody specific to the epidermal growth factor receptor | Panitumumab works by binding to the extracellular domain of the EGFR preventing its activation; this results in halting the cascade of intracellular signals dependent on this receptor | Is there effective systemic therapy for recurrent surgery- and radiation-refractory meningioma? | [76] | ||||

| Matuzumab (EMD72000) | A fully humanized ErbB-1-specific monoclonal antibody | Matuzumab binds to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on the outer membrane of normal and tumor cells; the matuzumab epitope has been mapped to domain III of the extracellular domain of the EGFR | Innovative therapeutic strategies in the treatment of meningioma | [77] | ||||

| mAb 806 | mAb 806 is a second-generation antibody | Depatuxizumab selectively targets a unique epitope on the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which is only expressed on cancer cells (and not on normal cells) | Targeting a unique EGFR epitope with monoclonal antibody 806 activates NF-κB and initiates tumor vascular normalization | [78] | ||||

| Nimotuzumab | Nimotuzumab (also known by the lab code h-R3) is a humanized IgG1 isotype monoclonal antibody | Nimotuzumab binds with optimal affinity and high specificity to the extracellular region of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor). This results in a blockade of ligand binding and receptor activation; epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a key target in the development of cancer therapeutics | Nimotuzumab is a promising therapeutic monoclonal for the treatment of tumors of epithelial origin | [79] | ||||

| PDGFR antagonists | ||||||||

| Imatinib (Gleevec) | C30H35N7O4S is a 2-phenyl amino pyrimidine derivative, orally given | Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is an inhibitor of PDGFR-a and b, Bcr –Abl, c-Fms, and c-Kit tyrosine kinases, which are responsible for abnormal cell growth through its constitutive expression; it has the power to inhibit PDGFR-a or b, which makes it a superior meningioma therapeutic alternative | The North American Brain Tumor Consortium (NABTC) evaluated the efficacy of imatinib in meningioma patients PDGFR antagonist; phase II: some stabilization of disease | [80] | ||||

| Nilotinib | C28H22F3N7O, orally given | Second-generation PDGFR inhibitor | Nilotinib alone or in combination with selumetinib is a drug candidate for neurofibromatosis type 2; no studies | [81] | ||||

| Dasatinib | C22H26ClN7O2S, orally given | Dasatinib inhibits the growth-promoting actions of SRC-family protein tyrosine kinases by binding to them; PDGFR antagonist | Combination therapy with mTOR kinase inhibitor and dasatinib as a novel therapeutic strategy for vestibular schwannoma; dasatinib is a multikinase inhibitor targeting SFKs, several EPH receptors, and c-Kit23 dasatinib and AZD2014 combination therapy was performed on NF2-deficient meningioma cells; in vivo and in vitro, this combination therapy efficiently inhibited the development of NF2-deficient meningioma cells; dasatinib and AZD2014 combined therapy was more effective than either monotherapy | [82] | ||||

| Tandutinib | C31H42N6O4 is a piperazinyl quinazoline, a potent anticancer agent,that specifically acts on the angiogenic pathways, orally given | This is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets PDGFRb, C-Kit, and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), thereby inhibiting cellular proliferation and inducing apoptosis (Fig. 1); PDGFR B antagonist | Vascular endothelial growth factor signals through platelet-derived growth factor receptor β in meningiomas in vitro | [61] | ||||

| VEGFR antagonists | ||||||||

| Bevacizumab (Avastin) | Bevacizumab is a full-length IgG1κ isotype antibody composed of two identical light chains (214 amino-acid residues) and two heavy chains (453 residues), intravenous infusion | Bevacizumab was engineered as a humanized monoclonal antibody to VEGF receptors that inhibits the binding and signaling cascade required for vascularization, as it leads to diminished tumor blood supply | Recently, numerous studies on anti-angiogenesis have been conducted on meningioma humanized monoclonal antibodies of EGFR; SSCTs: mixed results | [83] | ||||

| Cediranib (recentin) | C25H27FN4O3, also called AZD2171, is a potent anticancer agent, orally given | It is a small-molecule tumor kinase inhibitor of VEGFRs that also targets c-KIT and PDGFR-a | The effect of cediranib has been studied in various types of cancers, and 81 clinical trials have been conducted; it is currently being analyzed in juvenile recurrent CNS malignancies in phase I clinical trials (Fig. 1);VEGFR antagonist; no studies | [84] | ||||

| Combination antagonists | ||||||||

| Sorafenib (Nexavar) | C21H16ClF3N4O3 is a multi-tyrosine kinase synthetic inhibitor, orally administered | It is a potent anticancer agent with antiangiogenetic and cytostatic effects; it was the first approved angiogenetic multikinase inhibitor; this compound targets RAF kinase of the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway and inhibits the VEGFR-2/PDGFR beta signaling cascade, thereby preventing tumor angiogenesis | Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition by regorafenib/sorafenib inhibits the growth and invasion of meningioma cells | [85] | ||||

| Sunitinib (Sutent) | C22H27FN4O2 is a pyrrole and a monocarboxylic acid amide with potent anticancer activity, orally given | Inhibitor of VEGFR, PDGFR, and KIT tyrosine kinase; sunitinib blocks the tyrosine kinase activity of VEGFR and PDGFR; it inhibits angiogenesis and cell proliferation | Sunitinib is widely used in cancer treatment; association between meningioma and sunitinib was seen in studies; dual VGFER and PDGFR antagonist; phase II: some stabilization of disease | [86] | ||||

| Vatalanib (PTK-787) | C20H15ClN4 is an anilinophthalazine with potential anticancer activity, orally administered | Vatalanib, also called PTK787, is an inhibitor of VEGFR-1 (Flt-1), VEGFR-2 (KDR), and VEGFR3 (Flt4), by binding to the protein kinase domain of VEGFRs; dual VGFER and PDGFR antagonist; vatalanib induces a dose-dependent inhibition of VEGF-induced angiogenesis, as well as tumor-derived angiogenesis; it also binds to the tyrosine kinase domain of other receptors such as PDGFR, C-Fms, and c-Kit | Preclinical studies showed that, when given orally to orthotopic models, some stabilization of disease occurred | [69] | ||||

| Farnesyl transferase inhibitors | ||||||||

| Tipifarnib (Zrnestra) | C27H22Cl2N4O is a nonpeptidomimetic quinolinone and is a potent anticancer agent, orally administered | Farnesyl protein transferase is an enzyme that causes protein farnesylation and is involved in signal transduction; tipifarnib binds to and inhibits this enzyme, thereby inhibiting protein processing; it stops Ras oncogenes from being activated, resulting in the induction of apoptosis, as well as the prevention of cell proliferation and angiogenesis | Research on the use of tipifarnib against meningioma is underway | [69] | ||||

| mTOR inhibitors | ||||||||

| Temsirolimus (Torisel) | C56H87NO16 is an ester analog of rapamycin and a kinase inhibitor, intravenous infusion | Temsirolimus inhibits mTOR after attaching to it, leading to the downregulation of mRNAs required for cell-cycle progression; the cell cycle is halted in the G1 phase; mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that is involved in the PI3K/AKT signaling cascade; mTOR has been discovered to be elevated in certain malignancies; as it is like a protein kinase inhibitor, inhibition of mTOR activation is a kind of therapy for treating various types of cancers | Phase I/II study of erlotinib and temsirolimus for patients with recurrent malignant gliomas: North American Brain Tumor Consortium trial 04–02 | [87] | ||||

| Everolimus (Afinitor) | C53H83NO14 is derived from the macrocyclic lactone sirolimus in nature; it is an immunosuppressant, antiangiogenic, and anti-cell proliferative agent, orally given | Everolimus is an inhibitor that forms an immunosuppressive complex with the immunophilin FK binding protein-12 (FKBP-12), which then binds to and inhibits mTOR (mammalian target of Rapamycin); because mTOR is a regulatory kinase, it causes the production of mRNA that codes for cell-cycle proteins and hinders the glycolysis process, thus inhibiting tumor growth; as already explained, mTOR is upregulated in cancer and, hence, inhibition of mTOR activation may help in cancer treatment | Antitumor effect of everolimus in the case of grade III meningioma was reported; mTOR inhibitor; phase I | [88] | ||||

| Vistusertib | C25H30N6O3 is an antineoplastic agent and is administered orally | It is an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR); it inhibits mTORC1 and mTORC2, leading to tumor cell death and a reduction in tumor cell growth; it is a serine/threonine kinase that is involved in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling cascade; its suppression is the cornerstone of anticancer therapy because it is elevated in a variety of malignancies | Vistusertib (AZD2014) is under investigation for the treatment of advanced gastric adenocarcinoma; mTOR C1 and C2 inhibitor; phase II | [69] | ||||

| Akt inhibitors | ||||||||

| AZD5363/capivasertib | It is a novel pyrrolopyrimidine derivative with a potency of 10 nM or less in inhibiting the AKT isoform, orally administered | Capivarsertib inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT (Iat, Ser, and Thr) in BT474c cells in three cell lines; in vivo investigations revealed that, when given orally to nude mice, it reduced the phosphorylation of PRAS40, GSK3, and S6 in BT474c xenografts in a dose- and time-dependent manner; it inhibited the growth of xenografts in a dose-dependent manner in a variety of malignancies (Fig. 1) | Durable control of metastatic AKT1-mutant WHO grade 1 meningothelial meningioma was shown using the Akt inhibitor AZD5363 | [89] | ||||

| Afuresurtib | C18H17Cl2FN4OS is an orally administered drug | Afuresurtib is an inhibitor of Akt, a protein kinase inhibitor, and thus, a potent anticancer agent; afuresurtib inhibits Akt, which is increased in several types of cancer and is implicated in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, resulting in tumor growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis | Emerging medical treatments for meningioma in the molecular era | [90] | ||||

| PI3K inhibitor | ||||||||

| Alpelisib | C19H22F3N5O2S is a well-tolerated drug given orally | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase α (PI3Kα)-specific inhibitor; cell development and survival may be inhibited as a result | Phase I trial of alpelisib in combination with concurrent cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck showed that alpelisib in combination with trametinib can be used to treat aggressive and recurrent meningioma | [91] | ||||

| CDK4/6 inhibitors | ||||||||

| Palbociclib | C24H29N7O2 is an orally available cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor with potential anticancer properties, orally administered | CDK4 and 6 are serine/threonine kinases that regulate cell-cycle progression and are overexpressed in several malignancies; palbociclib inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases 4 (CDK4) and 6 (CDK6), which leads to cell-cycle arrest by inhibiting retinoblastoma (Rb) protein phosphorylation during the early G1 phase of the cell cycle; DNA replication is inhibited, and tumor cell proliferation is reduced | Palbociclib had effects in combination with radiation in preclinical models of aggressive meningioma; CDK4/6 inhibitor | [92] | ||||

| Ribociclib | C23H30N8O is orally given | CDK4/6 inhibitor | Ribociclib (LEE011) in preoperative glioma and meningioma patients; phase I | [69] | ||||

| Abemaciclib | C27H32F2N8 is orally given | CDK4/6 inhibitor | Meningioma is not always a benign tumor: a review of advances in the treatment of meningiomas | [93] | ||||

| MEK1/2 inhibitors | ||||||||

| Trametinib | C26H23FIN5O4 is an inhibitor of MAP2K/ERK kinase (MEK) 1 and 2 and a potent anticancer agent, orally given | Trametinib inhibits growth factor-mediated cell signaling and cellular proliferation in a variety of malignancies by targeting MEK 1 and 2, which are two types of MEK; MEK 1 and 2 are serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases with dual specificity that are commonly overexpressed in cancer; it affects cell proliferation by activating the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway | Trametinib is used in combination with dabrafenib for the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma | [94] | ||||

| Selumetinib | C17H15BrClFN4O3 is a small molecule that has potential anticancer activity, used to treat symptomatic, refractory fibroma in neurofibromatosis type 1, orally given | The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway regulates a variety of cellular activities, including proliferation; this pathway is abnormally regulated in cancer, and MEK1 and 2, which are dual-specificity kinases, are overexpressed; selumetinib inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinases (MEK or MAPK/ERK kinases) 1 and 2, resulting in cellular proliferation suppression in a variety of malignancies | Trial of selumetinib in patients with neurofibromatosis type II-related tumors (SEL-TH-1601) | [69] | ||||

| ERK inhibitor | ||||||||

| Regorafenib | C21H15ClF4N4O3 is orally given | ERK inhibitor | Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition by regorafenib/sorafenib inhibits the growth and invasion of meningioma cells | [85] | ||||

| Hedgehog pathway inhibitors | ||||||||

| Vismodegib | C19H14Cl2N2O3S, also called aDC-0449, is a small molecule and a potent anticancer agent. SMO inhibitor, orally given | Vismodegib is a Hedgehog antagonist that works by inhibiting Hedgehog signaling; it suppresses Hedgehog signaling by blocking the activity of the Hedgehog ligand cell surface receptors PTCH and/or SMO; the Hedgehog signaling system is so important for tissue growth and repair that its improper and constitutive activation leads to uncontrolled cellular proliferation | Vismodegib, FAK inhibitor GSK2256098, capivasertib, and abemaciclib in treating patients with progressive meningiomas; phase II | [69] | ||||

| Sonidegib | C26H26F3N3O3 is a small molecule that is administered orally for cellular growth, differentiation, and repair | It is an antagonist of smoothened (SMO), which shows potential antineoplastic activity; in cancer cells where the hedgehog pathway is abnormally activated, sonidegib inhibits the Hh signaling cascade by binding to the hedgehog (Hh) ligand cell surface receptor SMO; SMO inhibitor | Selective vulnerability of the primitive meningeal layer to prenatal SMO activation for skull base meningothelial meningioma formation; the Hh signaling pathway is responsible for this abnormal activation of the hedgehog path and way may be associated with a mutation in SMO | [95] | ||||

| FAK inhibitors | ||||||||

| GSK2256098 | C20H23ClN6O2 | FAK inhibitor | Vismodegib, FAK inhibitor GSK2256098, capivasertib, and abemaciclib in treating patients with progressive meningiomas; phase II | [69] | ||||

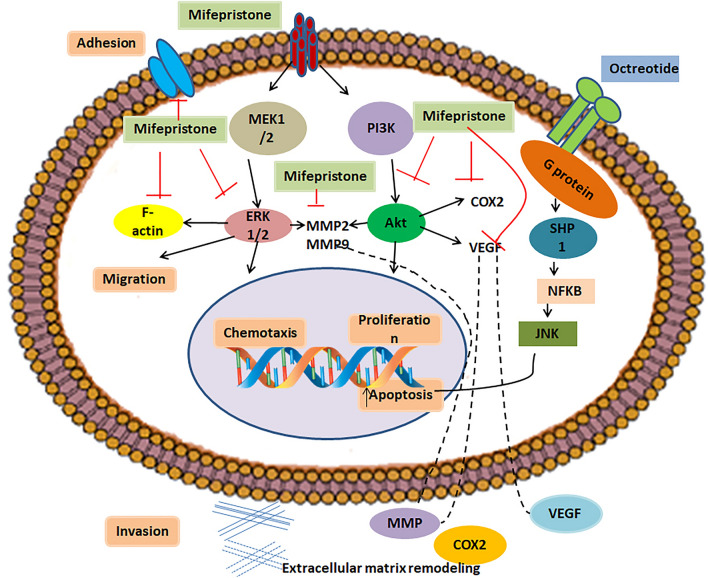

Hormonal therapy

Females are more likely to have meningiomas. They are more common after puberty and during the reproductive years. A study found a direct link between the number of pregnancies and the occurrence of meningioma. Increased risk of meningioma in women over the age of 50 has been seen [5, 96]. Breast cancer patients showed a higher tendency of meningioma [97]. Furthermore, 10% of meningiomas express estrogen receptors with a higher percentage of progesterone receptors [98, 99]. The greater degree of progesterone expression in meningioma has sparked extensive interest for research purposes. Somatostatin is a hormone majorly produced by the hypothalamus. This neuropeptide is released into the systemic circulation and reaches its primary sites of action, which are the pituitary, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract. It is responsible for inhibiting the endocrine and exocrine secretions, as well as the motility of the gastrointestinal tract. Somatostatin prevents cancer by acting as an anti-angiogenesis agent. It also inhibits invasion and apoptosis. Because somatostatin has a limited half-life, various analogs with extended half-lives have been created. Octreotide is a well-known somatostatin receptor agonist. One of the most successful treatments for pituitary adenomas and gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors is somatostatin analog therapy. Biochemical analysis or scintigraphy detected that the majority of meningiomas express somatostatin receptors. There are five subtypes of somatostatin receptors (sstr1–sstr5), with nearly 90% of meningiomas expressing somatostatin receptors. In one study, somatostatin analog octreotide showed an antitumor effect on progressive meningioma grade II to grade I. Mifepristone and octreotide are examples of hormone inhibitors. According to various studies, mifepristone can be used in cancer therapy alone or in combination with other drugs to treat different types of cancers; examples include nonsmall-cell lung cancer [100, 101], renal cancer [102], and pancreatic cancer [103]. Documented studies have shown that mifepristone also has an impact on brain tumors. Mifepristone acts as an antagonist to progesterone receptors. Reports have shown that progesterone is capable of inducing infiltration and migration in the rat cortex [104]. Glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors were found to be highly expressed in high-grade glioma patients, and they play role in cell proliferation; therefore, as an antagonist of progesterone and glucocorticoids, mifepristone blocks the capacity of progesterone to induce the growth, migration, and invasion of human astrocytoma cell lines [105, 106] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of drugs used in hormonal therapy of meningioma

Retinoids

Retinoids are derivatives of vitamin A that are potent anticancer agents. Their inhibitory effects include inhibition of growth, enhancement of differentiation, and anti-angiogenesis. Some cancers (e.g., acute promyelocytic leukemia) have been treated with synthetic retinoids. A study showed that retinoids induce noninvasive phenotypes in meningioma cells and, hence, can be used to treat meningioma [107] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Drugs used in hormonal therapy of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal agents | ||||||||

| Progesterone receptor-binding agents | ||||||||

| Megestrol (Megace) | C22H30O3, orally administered | Progesterone receptor partial agonist | SSCT: no survival benefit shown | [108] | ||||

| Mifepristone (RU- 486) | C29H35NO2 is a substituted 19-nor steroid compound and the first clinically available progesterone receptor antagonist; it is a derivative of the synthetic progestin norethindrone, orally given | It has antiprogesterone activity; it competes with progesterone for binding to its receptor, which leads to inhibition of the effects of endogenous or exogenous progesterone; progesterone receptor competitive antagonist | Mifepristone is useful in the treatment of vestibular schwannoma because of its anti-glucocorticoid effect; it also binds to progesterone receptors in meningiomas | [109] | ||||

| Estrogen antagonists | ||||||||

| Tamoxifen | C26H29NO is a tertiary amino compound and a stilbenoid, orally given | Estrogen receptor competent antagonist | A population-based study in Sweden found an association of tamoxifen with meningioma | [110] | ||||

| Somatostatin | ||||||||

| Octreotide (Sandostatin) | C49H66N10O10S2 is a synthetic long-acting cyclic octapeptide with anticancer properties, subcutaneous (s.c.) injection or intravenous (i.v.) infusion after dilution | It mimics somatostatin but is a more potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin; similar to somatostatin, this agent also suppresses the luteinizing hormone response to the gonadotropin-releasing hormone, decreases splanchnic blood flow, and inhibits the release of gastrin, serotonin, secretin, motilin, pancreatic polypeptide, and thyroid-stimulating hormone | Octreotide was administered with low toxicity in a small series of recurrent meningioma cases; somatostatin was found to decrease meningioma cell proliferation in vivo (Fig. 2) | [111] | ||||

| Pasireotide (Signifor) | C58H66N10O9, subcutaneous injection | Somatostatin mimetic | Phase II study of monthly pasireotide LAR (SOM230C) for recurrent or progressive meningioma | [112] | ||||

| GH receptor antagonists | ||||||||

| Pegvisomant (somavert) | PEGylated form of mutant growth hormone, subcutaneously | PEGylated GH receptor antagonist | Pegvisomant was investigated in the treatment of acromegaly | [113] | ||||

| IGF-I and IGF-II Antagonists | ||||||||

| Fenretinide | C26H33NO2 is a synthetic retinoid, orally given | It shows inhibition of growth via apoptosis in various tumor cell lines | Studies were aimed at finding the role and mechanism of fenretinide in controlling the growth of cells in meningioma | [114] | ||||

| Retinoids | [107] | |||||||

Interferons, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and immunotherapy

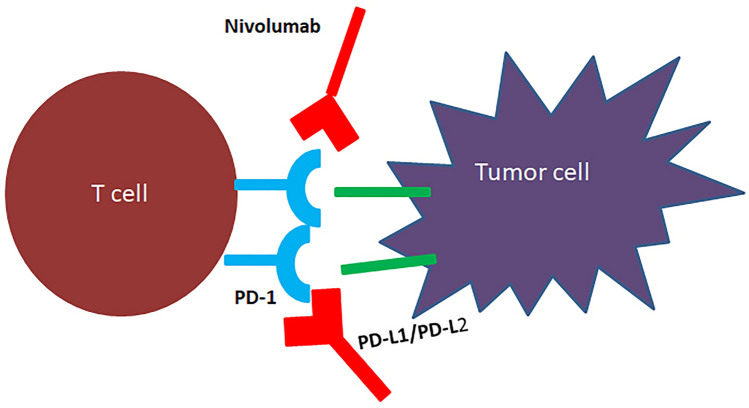

Our body is protected from foreign substances or antigens such as transplanted grafts, bacteria, and viruses by natural mechanisms through the immune system. Our immune system selectively eliminates foreign substances and prevents them from entering our bodies. It is also responsible for the removal of cancerous cells from our bodies. Some cancer cells, however, manage to evade the immune system detection. Immunotherapy has emerged as a viable cancer treatment option in recent years. The immune system has stimulatory or inhibitory regulators called immune checkpoints. They control how the antigen is presented to T-cell receptors. Immune checkpoints that restrict over activation of the immune system, such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 and programmed cell death protein 1 protect normal cells from being mistakenly killed by the immune system. By deregulating the CTLA4/PD-1 immune checkpoint pathway, certain cancer cells can evade the immune response. Immunotherapy reactivates the T-cell-mediated immune response to destroy tumor cells by targeting inhibitory immunological checkpoints like CTLA4/PD-1. There is evidence showing that checkpoint inhibition via PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has the potential to treat meningioma. There is a need to explore other new promising targets. Several studies in the past years confirmed the identification of previously unrecognized immunomodulatory proteins such as PD-L2, B7-H3, and NY-ESO1 [115–117]. Examples are nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and avelumab (Fig. 3) (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Diagram of antibodies used in the treatment of meningioma

Table 4.

Details of some common immunomodulators used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of Action | Type of study | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunomodulators | ||||||||

| IFN Α2b | C16H17Cl3I2N3NaO5S | Antiproliferative and antiangiogenic properties | Phase II: mixed results | [118] | ||||

| Nivolumab | It is a human IgG4 monoclonal antibody, intravenously | It works as a checkpoint inhibitor; T cells kill cancer cells and protect our body from cancer; in turn, cancer cells develop proteins to defend themselves against T lymphocytes; nivolumab inhibits the protective proteins in T lymphocytes, causing them to attack cancer cells; the protein PD-1 is found on the surface of activated T lymphocytes. T cells become inactive when another molecule termed programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 or programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 binds to PD-1; this anticancer drug works by preventing PD-L1/2 from attaching to PD-1, allowing T lymphocytes to destroy cancer cells | Outside of the respiratory epithelium and placental tissue, PD-L1 is expressed in 40–50% of melanomas and has low expression in most visceral organs; PD-1 receptor and ligand inhibitor; phase II | [69] | ||||

| Pembrolizumab | It is an immunoglobulin G4, intravenous injection | It is an immune checkpoint inhibitor like nivolumab; its mechanism of action is similar to nivolumab, which treats melanoma, head and neck cancer, lung cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, and stomach cancer; under normal conditions, T cells interact with other cells through PD-1 and PD-L1 or PD-L2; PD-1 receptors present on the activated T-cell bind to ligands PD-L1 or PD-L2 on other cells and deactivate the T-cell-mediated immune response; in this way, the body prevents the immune system from acting on normal cells; in many cancers, cells make protein PD-L1 that binds PD-1, thus shutting down the ability of the body to kill cancer cells; pembrolizumab inhibits the binding of PD-1 on lymphocytes to PD-L1 and PD-L2 on cancer cells, thereby allowing lymphocytes to destroy cancer cells | Pembrolizumab affects meningioma cell growth; PD-1 receptor and ligand, Inhibitor; phase II | [69] | ||||

| Avelumab | It is a human monoclonal antibody of isotype IgG1, intravenous infusion | Its working mechanism is the same as that of pembrolizumab and nivolumab | Avelumab is used for the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and renal cell carcinoma (Fig. 3); PD-1 receptor and ligand inhibitor; phase II | [119] | ||||

MicroRNAs

MiRNAs are short RNAs of 21–23 nucleotides that regulate the expression of several target genes after transcription. They may promote cancer or may suppress cancer. Recently, downregulation of miRNA-29c-3p and miR-219-5p has been linked to meningioma, with a similar expression of miRNA 145, miR200a, and miR355 affecting meningioma (Table 5).

Table 5.

Details of some common miRNAs used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug Composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MicroRNA | ||||||||

| miR-29c-3p | miRNA | A study revealed that miR-29c-3p promoted the malignant development of HCC by regulating the methylation of LATS1 caused by DNMT3B and inhibiting the anticancer function of the Hippo signaling pathway | Simultaneous analysis of miRNA–mRNA in human meningiomas by integrating transcriptome, investigating the relationship between PTX3 and miR-29c | [120, 121], | ||||

| miR-219-5p | miRNA | Overexpression of miR-219-5p can inhibit gastric cancer cell malignancy by targeting the liver receptor homolog-1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways | This microRNA expression signature predicts meningioma recurrence | [120, 122] | ||||

| miR-190A | miRNA | A recent study showed that miR-190a is involved in estrogen receptor (ERα) signaling, causing inhibition of breast tumor metastasis | While miR-190a is downregulated in aggressive neuroblastoma (NBL), its overexpression leads to the inhibition of tumor growth and prolonged dormancy periods in fast-growing tumors8 | [120] | ||||

| miR-145 | miRNA | miR-145 may serve as a tumor suppressor which can downregulate E-cad expression by targeting MUC1, leading to the inhibition of tumor invasion and metastasis | MiRNA-145 is downregulated in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas and negatively regulates the motility and proliferation of meningioma cells | [120, 122] | ||||

| miR-335 | miRNA | miR-335 promotes cell proliferation by directly targeting Rb1 in meningiomas | miR-335 promotes cell proliferation by directly targeting Rb1 in meningiomas | [120, 123] | ||||

Tumor suppressor proteins

There are certain proteins whose loss is widely distributed among meningioma grades such as protein 4.1B. Drugs targeting periostin reduce meningioma. Variation in the genes coding for proteins NF2, MN1, ARID1, MUC 5, and SEMA4D leads to meningioma. The pan histone deacetylase inhibitor AR42 increased the expression of p16, p21, and p27, but reduced the expression of cyclins D1, E, and A, as well as proliferating cell nuclear antigen, in the meningeal cell, which reduced the expression of cyclin B required for progression through the G2 phase. The differential effects of AR42 on cell-cycle progression of normal meningeal cells and meningioma cells can be of therapeutic use [124] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Details of some common tumor suppressor proteins used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor suppressor protein inhibitors | ||||||||

| AR42 | Protein, orally given | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | AR42, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, is a potential therapy for vestibular schwannomas and meningiomas; phase I | [124] | ||||

| Protein 4.1B | Protein, orally given | Growth suppressor | Protein 4.1B is differentially expressed in adenocarcinoma of the lung and functions as a growth suppressor in meningioma cells by activating rac1-dependent c-Jun-NH2-kinase signaling | [125] | ||||

| NF2, MN1, ARID1B, SEMA4D, MUC5 | Proteins | The NF2 gene provides instructions for the production of a protein called merlin, also known as schwannoma; this protein is made in the nervous system, particularly in specialized cells called Schwann cells that wrap around and insulate nerves, MN1 function is unclear, The ARID1B gene provides instructions for making a protein that forms one piece (subunit) of several different SWI/SNF protein complexes; SWI/SNF complexes regulate gene activity (expression) via a process known as chromatin remodelling, Semaphorin 4D (SEMA4D) is an axon guidance molecule that is secreted by oligodendrocytes and induces growth cone collapse in the central nervous system; by binding plexin B1 receptor, it functions as an R-Ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) and repels axon growth cones in the mature central nervous system, Mucin 5AC (MUC5AC) is a protein with unknown function that is encoded by the MUC5AC gene in humans; Muc5AC is a large gel-forming glycoprotein; in the respiratory tract, it protects against infection by binding to inhaled pathogens that are subsequently removed by mucociliary clearance | Exome sequencing on malignant meningiomas identified mutations in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and meningioma 1 (MN1) genes | [126, 127] | ||||

| Periostin and Ki-67 | Protein | Periostin has essential roles in wound healing, ECM deposition, mesenchymal cell proliferation, and tissue fibrosis, During mitosis, Ki-67 is essential for the formation of the perichromosomal layer (PCL), a ribonucleoprotein sheath coating the condensed chromosomes; in this structure, Ki-67 acts to prevent the aggregation of mitotic chromosomes | Periostin is a novel prognostic predictor for meningiomas, Ki-67/MIB-1 has a prognostic role in meningioma | [128, 129] | ||||

Other important drugs used in targeted therapy of meningioma

Epigenetic modifier inhibitor

Changes in epigenetic modifiers such as KDM5C are found in 8% of meningiomas. KDM5 inhibitor KDOAM-25 is being tested for meningioma.

BAP1 inhibition

Breast cancer 1-associated protein 1 inhibition is associated with early tumor occurrence.

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2

When the malignant meningioma cell line IOMM-Lee was transfected with tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI-2) and tumor growth was evaluated in vitro and in vivo, studies indicated that it could have therapeutic potential in malignant meningioma (Table 7). Table 7 Details of some common drugs used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma.

Table 7.

Details of some other common drugs used in target therapy for the treatment of meningioma

| Drug name | Drug composition/molecular formula administration | Mechanism of action | Type of study | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiretrovirals survivin protein downregulation, preclinical: cell culture/in vitro | ||||||||

| Nelfinavir | C32H45N3O4S, orally administered | The anticancer mechanism of nelfinavir includes modulation of different cellular conditions, such as unfolded protein response, cell cycle, apoptosis, autophagy, the proteasome pathway, oxidative stress, the tumor microenvironment, and multidrug efflux pumps | The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir has anticancer properties | [130] | ||||

| Lopinavir | C37H48N4O5, orally administered | Cell cycle arrest | Lopinavir inhibits meningioma cell proliferation via Akt-independent mechanism | [131] | ||||

| Epigenetic inhibitor | ||||||||

| KDOAM-25 | Histone lysine demethylase 5 (KDM5) inhibitor | KDOAM-25 is a KDM5 enzyme inhibitor that increases H3K4me3 levels at lower concentrations in MCF-7 cells | Advances in multidisciplinary therapy for meningiomas | [132] | ||||

| Possible adjunctive agents | ||||||||

| Calcium channel blockers | Benzothiazepines, phenylalkylamines, and dihydropyridines | Reduction of intracellular calcium concentrations | Calcium channel antagonists have effects on in vitro meningioma signal transduction pathways after growth factor stimulation; preclinical: animal models | [133] | ||||

| Statins | Pharmacophores, which are dihydroxyheptanoic acid segments, such as simvastatin (SIM), fluvastatin (FLU), atorvastatin (ATO), rosuvastatin (ROS), lovastatin (LOV), pravastatin (PRA), and pitavastatin (PIT) | Inhibition of MAPK pathway | Statins and thiazolidinediones have cytotoxic effects on meningioma cells; preclinical: cell culture/in vitro | [134] | ||||

| TL4 inhibitors | ||||||||

| Ipilimumab | Antibody | Binding to TL4, preventing the escape of immune surveillance mechanisms, | Toll-like receptors are therapeutic targets in central nervous system tumors; preclinical: cell cultures/in vitro | [135] | ||||

| Integrin inhibitor | ||||||||

| Cilengitide | Cyclic Arg–Gly–Asp peptide with antiangiogenic activity | Cilengitide acts as a highly potent inhibitor of angiogenesis and induces apoptosis of growing endothelial cells via the inhibition of the interaction between integrins with their ECM ligands | The integrin inhibitor cilengitide affects meningioma cell motility and invasion | [72] | ||||

| BAPI inhibitor | ||||||||

| Tazamatostat | C34H44N4O4 | Tazemetostat is a cancer drug that acts as a potent selective EZH2 inhibitor. Tazemetostat blocks the activity of the EZH2 methyltransferase, which may help keep the cancer cells from growing | Distant metastases in meningioma: an underestimated problem | [136] | ||||

| Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 | ||||||||

| Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 | TFPI-2 functions in the maintenance of the stability of the tumor environment and inhibits invasiveness and growth of neoplasms, as well as metastasis formation; TFPI-2 has also been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit angiogenesis, which may contribute significantly to tumor growth inhibition | Restoration of tissue factor pathway inhibitor inhibited invasion and tumor growth in vitro and in vivo in a malignant meningioma cell line | [137] | |||||

| RNAi | Antisense abrogation of mRNA strands | Preclinical: cell culture/in vitro | ||||||

Completed and ongoing clinical trial

Hydroxyurea has been found to have many hematological and dermatological side effects [138–146]. In a phase III placebo-controlled clinical trial, mifepristone which is an antiprogesterone drug showed no changes in radiographic response, six-month progression-free survival, time to tumor progression, and overall survival from the placebo [147, 148]. Two single-armed studies, showing no comparison of drug’s effectiveness with the proper comparator group, was done on tamoxifen limiting its use as an effective drug. Recently, some new pharmacotherapy targets and their targeted agents have been identified. Wide varieties of these agents are under investigation for treatment of meningioma. Ongoing studies are testing the Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway inhibitors (trametinib, selumetinib) as drugs for meningioma, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT)/the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway inhibitors, and AKT inhibitor (alpelisib, Vistusertib, Capivasertib) are currently under investigation for meningioma treatment [149, 150]. Despite putting efforts in treating meningioma using the drugs like epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors (brigatinib, afatinib), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors (cabozantinib, apatinib), no success could be achieved and work using this category drugs are still ongoing. VEGF inhibitors (bevacizumab, sunitinib, vatalanib) may offer some benefit in antiangiogenic treatments in meningiomas [86, 90, 150–154]. Findings suggest some role of c-MET and AXL inhibitor (cabozantinib) against meningioma by suppressing these proteins which are generally found elevated in meningioma [155, 156], similarly, smoothened (SMO) are potent targets for meningioma therapy [149, 157] and inhibitors of smoothened (SMO) are sonidegib and vismodegib. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitor (GSK2256098) has shown some response toward meningioma treatment [117, 158], ongoing research on ribociclib and abemaciclib, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (Ribociclib, abemaciclib) individually are on the way. Histone deacetylase inhibitor (OSU-HDAC42) is recently used in first clinical trial for the treatment of meningioma, Glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta (GSK-3β) inhibitor (9-ING-41). This inhibitor enhances NF-_B’s the transcriptional activity [159–161]. GSK-3β can be used to get control over multiple malignancy including meningiomas [162]. Dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) inhibitor (ONC206), this is an imipridone small molecule which produces cytotoxicity to tumor cells by increasing TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand’s activity [162]. PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab sintilimab), PD-L1 inhibitors (avelumab) can also be potential drugs against meningioma. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression increases with tumor grades so anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapy can be given to tumor patients [163, 164]. Currently, seven trials are going on to explore the effect of anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy on patients with meningioma. A current phase I trial study is being carried out on a newly modified drug, 177 Lu-DOTA-JR11, to investigate its safety and efficacy. While treating advanced and recurrent meningiomas, it is postulated to have better clinical efficacy and therapeutic index [165]. Two current phase II trials are evaluating the efficacy of LUTATHERA for the treatment of high-grade meningioma.

Limitations of conventional chemotherapy

Chemotherapy destroys normal cells, such as cells in the bone marrow, digestive tract, macrophages, and hair follicles, along with the cancerous cells [161].

Chemotherapeutic drugs cannot kill solid tumors as they fail to reach their core [162].

Traditional drugs are engulfed by macrophages and come out of circulation, remaining in circulation for a very short duration.

Some conventional chemotherapy drugs are unable to cross the plasma membrane and, hence, prove to be inefficient treatment options [163].

P-glycoprotein is a multidrug resistance protein that is overexpressed on the surface of cancerous cells due to which drugs do not accumulate inside the tumor, ultimately leading to resistance to anticancer drugs [164–167].

Exosomes and their role in cancer

Exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicles originating from the endosome system, which play role in cell-to-cell communication inside the tumor microenvironment (TME) [168]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) consists of tumor blood vessels, the extracellular matrix, and nonmalignant cells such as stromal cells, fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells [169–172]. Therefore, there are interactions among cancer cells, mesenchymal cells, and endothelial cells for the proper development of cancer [171]. Exosomes transfer proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids from parent cells to recipient cells. The various steps involved in exosome formation are as follows:

Extracellular components are captured via endocytosis leading to the formation of early endosomes.

Some specific endocytic bodies carrying proteins and nucleic acids sprout to form intraluminal vesicles (ILVs).

Late endosomes are formed from multivesicular bodies which carry multiple ILVs [172].

Many MVBs are digested by lysosomes while some vesicles with CD63, LAMP1, and LAMP2 on their surface fuse with the membrane, which are then secreted extracellularly [173].

ILVs and MVBs are formed with the help of endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT). There are four types, including vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4 (VPS4), apoptosis linked gene 2-interacting protein X (ALIX), and vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 1 (VTA1). ESCRT is mainly involved in sorting specific substances in ILVs. Exosomes act as a double-edged sword as they promote cancer formation on one hand, while they can kill the targeted cancer cells by encapsulating anticancer drugs, on the other hand.

Exosomes and tumor microenvironment

The TME was defined in the previous section. The TME has important features such as low oxygen levels, extracellular acidosis, poor nutrient content, and high lactate levels [174, 175]. As described earlier, the TME is composed of various cells including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and immune cells which secrete cytokines and growth factors [176]. Tumor progression is predicted by interactions between the TME and activation/inhibition pathways, which help in developing therapies targeting the TME [177–179]. Macrophages are found in excess in the TME and exhibit two phenotypes (M1 and M2) [180]. When there is shift toward the M2 phenotype, the chances of tumor progression are increased, mediating therapy resistance [181, 182]. One related signaling pathway with an oncogenic role is the signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 (STAT3) pathway [183–187]. Recently, a relationship was revealed among STAT3, exosomes, macrophage polarization, and glioma. In glioma, which is a very disastrous type of brain tumor, there is an increase in the secretion of exosomes along with an increase in hypoxic conditions. Exosomes release interleukin 6 and miRNA-155-3p, which activate STAT3, thus leading to autophagy. Autophagy then elevates the shift toward M2 polarization, which further increases glioma progression [188]. This study provided a big clue of how similar mechanisms can be found in meningioma, facilitating the development of a new targeted therapy.

Role of exosomes in tumor progression, tumor metastasis, and angiogenesis

Exosomes are an important component of the TME that can affect the proliferation and differentiation of cells. Therefore, an option for the treatment of cancer is to target the TME. Exosomes carrying CD171 from their parent cells can cause glioma cell invasiveness, proliferation, and motility [189]. Four important steps for cancer metastasis are (1) local infiltration of cancer cells, (2) entry of cells into circulation through the lymphatic system or blood vessels, and (3) entry or exit of cancer cells from remote organs. All steps are carried out by exosomes. Another important characteristic of cancer cells is metabolic reprogramming [190] which involves various cellular events such as the Warburg effect, changes in metabolites of the Krebs cycle, and the rate of oxidative phosphorylation, all of which fulfill the energy and structural requirements for growth and invasiveness of cancer cells [191].

The role of exosomes in the transition of grades and subtypes of meningiomas

As mentioned earlier, meningiomas are classified on the basis of their histological features. However, this system of grading remains unsatisfactory due to poor reproducibility and considerable variability within grades. According to the WHO 2021 classification, there are total of 15 subtypes. Grade I meningiomas have nine histological subtypes: meningothelial, fibrous, transitional, psammomatous, angiomatous, microcystic, secretory, lymphoplasmacyte-rich, and metaplastic. Grade II menangiomas have three subtypes: chordoid, clear cell, and atypical. Grade III menangiomas have three subtypes: papillary, rhabdoid, and anaplastic (malignant) [192]. The most common subtype is meningothelial (57.7% of all meningiomas) originating more commonly from the parasagittal area, followed by transitional (19%) and fibrous (13%) meningiomas, while metaplastic and lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningiomas are exceptionally rare [193]. Several new markers are now being discovered, thanks to the availability of genomic and epigenomic profiling. These markers indicate the location, histological subtype, and clinical behavior of meningiomas. These discoveries enable us to develop new targeted therapies, as well as new adjuvant methods. Some of the latest techniques used for this purpose include copy number alterations, specific genetic abnormalities (germline or sporadic), and genome-wide methylation profiles. Since exosomes are also the source of different types of molecular markers, they can help in categorizing the various grades and subtypes of meningiomas. This may also provide information related to the detection of the grade or the subtype, resulting in the creation of new, advanced targeted therapies. According to recent studies, circulating miRNAs such as miRNA 497 and 219 inside the exosomes have the potential to be used as cancer biomarkers in various tumors including meningiomas [194]. In another study, M2 macrophage-derived exosomes were found to stimulate meningioma progression through the TGF-β signaling pathway [195]. Fibulin-2 was observed as another marker for differentiating grade II and grade I meningiomas [196]. Similar studies showed that the serum levels of miR-106a-5p, miR-219-5p, miR-375, and miR-409-3p were significantly increased, whereas the serum levels of miR-197 and miR224 were markedly decreased in the case of meningiomas; hence these six miRNAs act as noninvasive markers for meningioma [197]. Therefore, the abovementioned examples show how exosomes can be exploited as potent biomarkers for the detection and treatment of meningiomas.

The role of exosomes in immune escape

To develop properly, tumors adopt various strategies and manipulate the surrounding microenvironment. Evading the immune system is a powerful strategy opted by tumor cells to proliferate and metastasize. Studies have shown that several mechanisms render cancerous cells tolerant to the immune system. Cancer cells can cause the death of immune cells by following the FasL/Fas and PD-L1/PD-1 pathways, which lead to a decrease in the number of T cells and NK cells. Furthermore, cancer cells also recruit myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) that halt CD8 + T-cell functioning, resulting in tumor immune escape. Recently, extensive efforts have been made to understand the role of cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles in activating the immune escape mechanism [198, 199]. EVs are involved in tumor microenvironment remodeling through angiogenesis [200–202], invasion [203, 204], metastasis [205–207], and resistance to therapies [208, 209].

Exploring the mechanisms of tumor-derived exosomes-mediated immune escape

Previous studies showed that extracellular vesicles inhibit the immune response against cancer at the innate and adapted levels [210]. Tumor-derived exosomes act on different components of the immune system through three mechanisms: functional activation, functional inhibition, and functional polarization.

Functional activation: As the tumor develops, it promotes the production of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which enhance the immunosuppressive activity within the tumor microenvironment [211]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are upregulated in cancer patients and perform an immunosuppressive function within the tumor microenvironment, leading to tumor progression [212–214]. In a study by Szajnik and colleagues, tumor-derived extracellular vesicles induced the expansion of human Tregs, whereas normal cell-derived EVs did not. This study was the first to show that TEVs (Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles/tumor-derived exosomes) can cause the expansion of human Tregs [215].

Functional inhibition: The tumor microenvironment refers to the environment around the tumor and consists of surrounding blood vessels, immune cells, fibroblasts, signaling molecules, and the extracellular matrix, as described earlier. Dendritic cells are antigen-presenting cells that are involved in the innate and adaptive immune response. DCs are part of the tumor microenvironment, which act by capturing antigens and presenting them to T cells, subsequently activating the antitumor immune response. A mechanism that facilitates tumor cells escaping immune surveillance is the inhibition of DC maturation [216, 217]. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles inhibit the dendritic cell maturation process. For example, in the case of lung carcinoma and breast cancer, the TEV-mediated inhibition of DCs has been studied [218]. NK cells are an important component of the immune system as they cause the lysis of target cells. Some studies have shown that TEVs cause the inhibition of NK cells, thus facilitating escape from the immune system. TEVs have also been reported to inhibit T lymphocyte cells, particularly CD8 + T cells [219]. This inhibition helps the tumor to grow and metastasize, leading to a tumor-friendly environment.

Functional polarization: The tumor microenvironment also contains tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which have the potential to infiltrate tumors and suppress the function of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, thereby enhancing cancer progression. A recent study showed that TEVs contribute to TAM polarization, whereby TV-treated macrophages were seen to promote in vivo tumor growth [220].

Immune checkpoints and cancer

Cancer cells escape the immune system [221] through various mechanisms:

Tumor cells can express corrupted versions of self-molecules;

Tumor cells can release immunosuppressive substances;

Aberrant changes in lymphocyte expression can lead to the antitumor immune response of tumor cells. Tumor cells can modulate macrophage function through this antitumor immune response [222].

The immune checkpoint inhibitor PD-1

Cancer cells survive inside the human body by generating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. These cells express higher amounts of inhibitory ligands such as PD-L1 and PD-L2. These ligands inhibit the responses of T lymphocytes by binding to PD-L1 inhibitor receptors, which are expressed by T lymphocytes. They resist the apoptosis of cancer cells by T lymphocytes. PD-L1 expression was found to be higher in various types of cancer, including pancreatic cancer [223], renal cell carcinoma [224], lung cancer [225, 226], breast cancer [227, 228], gastric cancer [229, 230], and colorectal cancer [231].

Tumor-derived exosomes are carriers of PD-L1

It is known that PD-L1 plays a role as a tumor biomarker. Currently, interest is being garnered in the role of PD-L1-carrying tumor-derived EVs in regulating tumor progression. Several in vivo and in vitro tumor models such as melanoma, breast, glioblastoma, and prostate cancer have revealed the biological effects of ExoPD-L1 in causing cancer [232]. There is evidence showing that TEVs carrying PD-L1 are crucial players in inhibiting the proliferation and activation of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, which infiltrate the tumor microenvironment. Hence, PD-L1 is responsible for inhibiting immune surveillance and promoting tumor progression. Recently, substantial focus has been given toward blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathways to resist cancer progression. Immune checkpoint protein inhibitors such as antibodies against PD-L1 and PD-1 can be used for curing numerous cancers [227–244]. In the future, characterization of the biological activities of ExoPD-L1 can contribute to understanding the mechanisms of immune escape.

Tumor-derived exosomes as modulators of PD-L1 expression in target cells

Recent studies have shown that tumor-derived extracellular vesicles carry PD-L1 and induce its expression in myeloid cells.

Role of exosomes in chemoresistance

Exosomes mediate tumorigenesis, metastasis, angiogenesis, and drug resistance, and they play role in physiological processes and pathological conditions [245, 246]. Chemoresistance can be classified as primary drug resistance and multidrug resistance. In primary drug resistance, cancer cells are resistant to induced drugs, whereas, in multidrug resistance, cancer cells become resistant to induced drugs, as well as other drugs to which cancer cells were not exposed [247]. Chemoresistant cancer cells show several properties and follow some mechanisms for their production. These include induced DNA repair, downregulation of apoptosis, increased drug efflux, alterations of drug targets, and overexpression of MDR proteins [248, 249]. Several proteins and nucleic acids have been identified as responsible for making cells resistant to drugs.

Role of exosomes in theranostics for the management of meningioma

Exosomes as diagnostic tools

Exosomes are present in body fluids such as breast milk, plasma, saliva, serum, malignant ascites fluids, and urine, which can be easily isolated [250–252]. Exosomes have clinical applications as diagnostic biomarkers, as well as therapeutic tools. The bodily fluids of both healthy individuals and diseased patients contain different proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs inside exosomes, which can be potential biomarkers. Exosomes can be biomarkers in both cancerous and noncancerous diseases. Abundant nucleic acids, proteins, etc., in tumor-derived exosomes can serve as tumor markers; for example, EGFRVIII mRNAs are found in increased amounts in the circulating exosomes of patients with glioblastoma multiforme and lung cancer [253, 254]. Similarly, higher levels of proteoglycan glypican-1-positive exosomes have been detected in pancreatic cancer patients [255–258]. Specific mRNA/miRNA profiles in exosomes isolated from serum are seen in patients with ovarian cancer and lung cancer. miR-21, miR-16, miR-93, miR-100, miR-126, miR-200, and miR-223 were found upregulated in ovary cancer patients as compared to normal [259]. Breast cancer cells showed increased level of EpCAM-positive exosome, Del-1 exosome level, and HER2 expression [260–262]. Exosomal proteins present in urine are potential biomarkers for bladder and prostate cancer [263, 264]. Enrichment of lncRNA that sponges miRNA in the exosomes of prostate cancer patients showed their involvement. In this case, 26 lncRNAs observed downregulated and 19 lncRNAs got upregulated [265]. A recent comparative analysis of exosomal proteins from patients with different types of cancers showed that the level of CD63 was higher in exosomes isolated from cancer cells than the exosomes of normal cell lines [260].

Exosome-based cancer therapy by engineering of exosomes, extracellular vesicles using different types of nucleic acids, proteins and drugs

Several methods have been developed for exosome-based cancer therapy [261, 265–268], including the use of immune cell-derived natural exosomes to suppress cancer [269], preventing the production of cancer cell-derived exosomes, using exosomes as gene carriers [266], and using exosomes as anticancer drug carriers [267]. Extracellular vesicles are good drug carriers for tumor therapy due to their excellent properties such as biosafety, stability, and target specificity. In recent years, substantial efforts have been directed toward specifically engineering EVs to improve their tumor-targeting ability and drug delivery efficiency. These modifications can be applied directly or indirectly.

Engineering EVs in tumor therapy

-

Modification methods

Direct modifications: Direct modifications involve altering the surface proteins and the contents of purified EVs. Such modifications can be introduced physically or chemically. Specific peptide sequences and target proteins are inserted into the membrane of EVs. There are several physical modification methods, including simple incubation, electroporation, sonication, extrusion, freeze–thaw cycles, and saponin. Chemical modifications can be covalent or noncovalent, electrostatic interactions, ligand–receptor interaction, etc.

Indirect modifications: In the case of indirect modifications, parent cells are incubated so that specific types of EVs can be produced. Parent cells of EVs can be genetically and metabolically engineered to enhance their tumor-targeting capabilities and drug delivery efficiency. Indirect modifications can be applied via genetic engineering, metabolic engineering, membrane engineering, and loading components in parent cells.

-

Sources

Various cell types including mesenchymal stem cells, immune cells, and cancer cells are suitable choices for EV-based drug delivery [270]. EVs from other types of immune cells such as M1 EVs, DC-EVs, and NK-EVs are capable of affecting the tumor microenvironment, and hence, are used for inhibiting tumor progression.

-

Route of administration