Abstract

Objective

To investigate peripheral blood cell (PBCs) global gene expression profile of SSc at its preclinical stage (PreSSc) and to characterize the molecular changes associated with progression to a definite disease over time.

Material and methods

Clinical data and PBCs of 33 participants with PreSSc and 16 healthy controls (HCs) were collected at baseline and follow-up (mean 4.2 years). Global gene expression profiling was conducted by RNA sequencing and a modular analysis was performed.

Results

Comparison of baseline PreSSc to HCs revealed 2889 differentially expressed genes. Interferon signalling was the only activated pathway among top over-represented pathways. Moreover, 10 modules were significantly decreased in PreSSc samples (related to lymphoid lineage, cytotoxic/NK cell, and erythropoiesis) in comparison to HCs. At follow-up, 14 subjects (42.4%) presented signs of progression (evolving PreSSc) and 19 remained in stable preclinical stage (stable PreSSc). Progression was not associated with baseline clinical features or baseline PBC transcript modules. At follow-up stable PreSSc normalized their down-regulated cytotoxic/NK cell and protein synthesis modules while evolving PreSSc kept a down-regulation of cytotoxic/NK cell and protein synthesis modules. Transcript level changes of follow-up vs baseline in stable PreSSc vs evolving PreSSc showed 549 differentially expressed transcripts (336 up and 213 down) with upregulation of the EIF2 Signalling pathway.

Conclusions

Participants with PreSSc had a distinct gene expression profile indicating that molecular differences at a transcriptomic level are already present in the preclinical stages of SSc. Furthermore, a reduced NK signature in PBCs was related to SSc progression over time.

Keywords: preclinical SSc, gene expression, modular analysis, disease progression

Rheumatology key messages.

At a transcriptomic level, molecular differences are already present in the preclinical stages of systemic sclerosis.

A reduced peripheral blood cells natural killer signature is related to disease progression and onset of skin fibrosis.

Introduction

SSc is a systemic autoimmune disease in which microvascular impairment, fibrosis and autoantibodies production are interconnected events that lead to a progressive multi organ damage. The 2013 ACR/The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (ACR/EULAR) defined classification criteria for SSc and a total score of 9 is sufficient to classify the patients for a definite form of SSc [1].

According to 2001 LeRoy and Medsger criteria, patients at a preclinical stage of disease present solely with RP, positive SSc specific auto-antibodies and/or a nailfold video-capillaroscopy positive for ‘scleroderma pattern’, thus do not reach the score of 9 necessary for the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria [1, 2]. This group of patients with early signs of SSc but no other fibrotic clinical features, are classified as PreSSc patients (pre-clinical SSc, also named in literature as early SSc). Based on the study by Koenig and colleagues, patients with preclinical SSc have about a 50% risk for disease progression into a definite/established fibrotic form within five years of diagnosis [3]. In 2011, criteria for a very early diagnosis of SSc (VEDOSS) were proposed, individuating ANA positive, SSc-specific autoantibodies, puffy fingers and abnormal nailfold capillaroscopy as potential predictors of a definite SSc [4, 5].

Currently, due to the low number of recruitable patients at a preclinical stage, research studies focused on PreSSc patients are numerically limited. Studies performed on few PreSSc cohorts so far, reported the presence of immunological alterations since the very early preclinical stages of SSc, suggesting that further promising investigations should be performed on these subjects.

Examining a limited panel of expression of 11 IFN type I inducible genes, a type I IFN signature was detected in whole blood samples of PreSSc patients [6]. To the best of our knowledge, no global gene expression studies in preclinical SSc patients have been performed yet.

At the protein level, few studies examining a limited number of serum proteins in PreSSc patients have been published. According to a study in 24 PreSSc patients, 48 definite SSc patients, and 24 osteoarthritis/fibromyalgia controls, higher sICAM-1, CCL2, CXCL8 and IL-13 levels, as well as a markedly increased IL-33 levels were present in PreSSc patients in comparison to controls [7]. A more recent study identified significantly elevated serum levels of CXCL10, CXCL11, TNFR2 and CHI3L1 in preclinical SSc [8]. In a study on a cohort of 34 subjects fulfilling VEDOSS criteria and 29 SSc, CXCL10 and CXCL11 were higher in the SSc group and were also found to be predictive of progression over time from VEDOSS to SSc [9].

The time between RP appearance and the definitive organ involvement provides a unique window of opportunity for understanding early progression of SSc molecular profile with important clinical and biological implications. The present longitudinal study aimed at characterizing the peripheral blood cell (PBC) global gene expression profile of PreSSc and its progression over time.

Patients and methods

Clinical features and PBC RNA samples of 33 patients at a pre-clinical stage were collected consecutively at baseline and re-collected after four years. PreSSc patients were defined according to 2001 LeRoy and Medsger criteria for the classification of early SSc [2] (that is the presence of RP plus SSc‐specific autoantibodies and/or SSc‐specific nailfold video-capillaroscopic changes without any other sign of definite SSc and/or fibrosis thus at high risk of developing SSc) [3] thus meeting part of VEDOSS criteria with the exclusion of puffy fingers that is the very first feature of skin involvment in SSc. Nailfold video-capillaroscopy was only assessed at baseline visit. Clinical and laboratory data at 4 years were available to determine whether PreSSc patients had progressed to definite SSc according to the ACR/EULAR criteria [1] or whether they had remained stable at a pre-clinical stage. PreSSc patients were considered progressors if the minimum score of 9, as required according to the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria to be classified as definite SSc, was reached. Patients with clinical progression were then classified as diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) or limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) accordingly to the extent of skin fibrosis. Patients with a definite SSc but without skin fibrosis yet with puffy fingers were categorized in the lcSSc group [2]. Patients that after 4 years of observation kept preclinical features, were labelled as ‘stable PreSSc’ while those progressing to definite SSc were labelled as ‘evolving PreSSc’. Of note, only two stable SSc patients did not have SSc nailfold capillaroscopic changes at the baseline visit and neither of them had developed non-capillaroscopic SSc classification criteria during the follow-up visit. Patients were not treated at baseline or during follow-up with any kind of immunosuppression or immunomodulating agents (such as hydroxychloroquine). Patients could be on treatment for the control of RP (low-dose aspirin and/or calcium channel blockers).

Blood samples from 16 age- and ethnicity matched healthy controls were also collected at the follow-up visit. Controls had no history of systemic autoimmune diseases or concomitant relevant diseases such as diabetes, cancer or infectious diseases and were not relatives of the enrolled PreSSc patients.

Data and sample collection was approved by the local Ethical Committee, Comitato Etico Milano Area 2, and patients provided signed informed consent.

RNA sequencing

PreSSc’s and healthy controls’ whole blood samples were collected in PAX gene tubes and stored at –80°C. RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol and quality was assessed by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Globin genes were depleted using GLOBIN Clear kit. mRNA was enriched from total RNA using oligo(dt) beads (NEB Next Ultra II RNA Kit following the poly(A) enrichment workflow). The mRNA was subsequently fragmented randomly in fragmentation buffer, and reverse transcribed to cDNA. The cDNAs were converted to double stranded cDNAs, then subjected to end-repair, A-tailing and adapter ligation, size selection and PCR enrichment. Library concentration was first quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then diluted to 1 ng/ul before checking insert size on an Agilent 2100 and quantified to greater accuracy by quantitative PCR (q-PCR) (library activity >2nM). Libraries were pooled into Novaseq6000 machines according to molarity and expected data volume. A paired-end 150 bp sequencing strategy was used to generate an average of 88 million reads per sample. The gene expression data will be deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)’s Gene Expression Omnibus.

Transcript data were normalized with DESeq2. Transcripts were filtered with count-per-million (CPM) keeping those genes that had at least two samples with ‘cpm >1’. A total of 17746 transcripts out of 60641 in raw count file passed the filtering criteria. Transcripts were considered as differentially expressed if P < 0.05 and Log2 fold change >0.2 (or less than –0.2). An unpaired analysis was used for the comparison of study groups at the baseline visit and a paired analysis was performed for the longitudinal comparisons.

Modular analysis

Modular analysis utilizing 62 curated whole-blood modules was conducted using the original repertoire analysis described in [10] and [11]. A gene set analysis was conducted using the QuSAGE algorithm for the modular analysis of differentially expressed genes [12]. QuSAGE tests whether the average log2 fold change of a gene set is different from zero. The method correctly adjusts for gene-to-gene correlations within a gene set and provides an easy interpretable metric for the magnitude of differential regulation. A threshold value of P < 0.05 and Log2 fold change >0.2 (or less than –0.2) was used to identify differentially expressed module.

Results

Demographic data

Among the 33 PreSSc subjects included in the study, 14 (42.4%) presented signs of progression towards a definite SSc at 4 years. Baseline demographic characteristics of PreSSc patients, stratified by 4-year progression outcome, are presented in Table 1. At baseline, patients who did progress (evolving PreSSc) and who did not (stable PreSSc) had a comparable age, gender, auto-antibody profile, Raynaud’s phenomenon duration and pulmonary function test percentage of predicted values; upper GI tract symptoms, mainly gastroesophageal reflux disease, were present in a small percentage. As per exclusion criteria, none of patients had any skin involvement including puffy fingers. No patient was treated with steroids, immunosuppressants or biologics at the time of baseline evaluation and thereafter. Evolving PreSSc and stable PreSSc were both treated with antiplatelets agents and calcium channels blockers for RP, with a significantly higher portion of stable PreSSc patients being treated with low dose aspirin at the baseline visit.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of PreSSc patients along with stratification according to the 4-year evolution outcome

| Features | All subjects [33] | Stable PreSSc [19] | Evolving PreSSc [14] | HC [16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 56.6 ± 12.6 | 57.1 ± 10.4 | 55.9 ± 15.4 | 55.3 ± 12.6 |

| Gender, female n (%) | 28 (84.8) | 15 (78.9) | 13 (92.9) | 15 |

| Ethnicity Caucasian n (%) | 33 (100) | 19 (100) | 14 (100) | 16 (100) |

| ANA n (%) | 32 (97) | 18 (94.7) | 14 (100) | NA |

| ACA n (%) | 22 (66.7) | 12 (63.2) | 10 (71.4) | NA |

| Anti-Scl70 n (%) | 6 (18.2) | 3 (15.7) | 3 (21.4) | NA |

| Other n (%) | 5 (15.1) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (7.1) | NA |

| RP years duration mean (s.d.) | 9.6 ± 8.1 | 9.9 ± 8.5 | 9.1 ± 7.8 | NA |

| Positive video-capillaroscopy n (%) | 31 (93.9) | 17 (89.5) | 14 (100) | NA |

| FVC (%) mean (s.d.) | 115.5 ± 16.7 | 114.1 ± 18.3 | 117.4 ± 14.7 | NA |

| DLCO (%) mean (s.d.) | 86 ± 18.6 | 86.3 (20.3) | 85.6 (16.8) | NA |

| SSc clinical features | ||||

| None n (%) | 16 (48.5) | 10 (52.6) | 6 (42.9) | NA |

| Skin n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Upper GI n (%) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (28.6) | NA |

| Teleangectasia n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Low dose aspirin n (%) | 28 (84.5) | 19 (100)* | 9 (64.3) | NA |

| CCB n (%) | 24 (72.7) | 15 (78.9) | 8 (57.1) | NA |

CCB: calcium channel blockers; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity; GI: gastrointestinal; n: number; NA: not applicable.

P-value = 0.008 based on χ2 test.

Features of progression at 4 years included puffy fingers in 57.1% of cases, skin fibrosis and telangiectasia, alone or in combination with the above (Table 2). Time of observation between baseline to follow-up visit and RP duration were well balanced between stable and evolving PreSSc patients as shown in Supplementary Table S1 (available at Rheumatology online) which lists each patient’s features at the baseline and follow-up visits. Moreover, FVC % at follow-up visit was similar between the two groups while Dlco% was numerically lower in the evolving PreSSc group (77.2% vs 85.6%, P = 0.25) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subjects clinical features at follow-up

| Features | Stable PreSSc 1 [19] | Evolving PreSSc [14] |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (s.d.) | 61 (10.5) | 60.2 (15.4) |

| Gender, female n (%) | 15 (78.9) | 13 (92.9) |

| Ethnicity Caucasian n (%) | 19 (100) | 14 (100) |

| ANA n (%) | 18 (94.7) | 14 (100) |

| ACA n (%) | 12 (63.2) | 10 (71.4) |

| Anti-Scl70 | 3 (15.8) | 3 (21.4.7) |

| Other | 4 (21.1) | 1 (7.1) |

| Follow-up time mean (s.d.) | 3.9 (0.6) | 4.3 (0.6) |

| RP years duration mean (s.d.) | 13.9 (8.6) | 13.3 (7.8) |

| FVC (%) mean (s.d.) | 118.1 (18.1) | 118.8 (17.2) |

| DLCO (%) mean (s.d.) | 85.6 (23.2) | 77.2 (13.9) |

| Progression n (%) | 0 | 14 (100) |

| SSc clinical features | ||

| None n (%) | 9 (47.4) | 0 |

| lcSSc features n (%) | 0 | 12 (85.7) |

| Puffy fingers n (%) | 0 | 8 (57.1) |

| Sclerodactily n (%) | 0 | 4 (28.6) |

| dcSSc n (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Upper GI n (%) | 6 (31.6) | 9 (64.3) |

| Teleangectasia n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (35.7) |

| Low dose aspirin n (%) | 14 (73.7) | 10 (71.4) |

| CCB n (%) | 13 (68.4) | 11 (78.6) |

CCB: calcium channel blockers; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity; GI: gastrointestinal; n: number; NA: not applicable.

RNASeq gene expression data

Comparison of PBC global gene expression profile of overall baseline PreSSc samples to matched healthy controls revealed 2889 differentially expression genes (DEGs) with the majority of transcripts [n = 2639 (91.3%)] being down-regulated in PreSSc samples. The complete list of DEGs is included in an online supplementary data file (https://go.uth.edu/scleroderma-data). Fig. 1A shows the top ten overrepresented Canonical pathways based on Ingenuity Pathway Analysis for this comparison. Specifically, interferon signalling pathway was the only activated pathway while HGF, LPS-stimulated MAPK, NF-κB activation by Viruses, Natural Killer Cell, Aldosterone Signalling in Epithelial Cells and Macropinocytosis signalling were down-regulated.

Figure 1.

The top ten overrepresented canonical pathways (A) Top 10 overrepresented canonical pathway in comparison of baseline PreSSc samples to healthy controls; (B) Top 10 overrepresented Canonical Pathway in comparison of follow-up to baseline sample changes in stable vs in evolving PreSSc groups

Next, a modular analysis was pursued. In this analysis, 62 gene expression modules observed in whole blood across a variety of inflammatory and infectious diseases are investigated and a biological function assigned to each module based on the function of genes present in that module. Some of the modules remain undetermined (Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online).

As shown in Table 3, 10 modules were significantly decreased in comparison of overall baseline patient samples to healthy controls while no modules were upregulated. These down-regulated modules included those related to lymphoid lineage, cytotoxic/NK cell and erythropoiesis. The previously reported upregulation of interferon inducible genes was not observed at the prespecified threshold level but interferon modules 1.2 and 3.4 showed a trend for higher expression values in baseline patient samples (log fold change = 0.33, P = 0.068; log fold change = 0.17, P = 0.053, respectively). Moreover, two modules were differentially expressed in the comparison of anti-Scl70 to anti-centromere positive PreSSc patients: M5.15 neutrophils/granulocyte module was down regulated (log fold change P = –1.34, P = 0.006) while M 4.11 plasmablasts module was upregulated (log fold change = 0.574, P = 0.05) (see Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online).

Table 3.

Differentially expressed modules in comparison of overall PreSSc vs healthy controls at baseline

| Module | Module annotation | logFC | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| M6.18 | Erythropoiesis | –0.445 | 0.000 |

| M2.3 | Erythropoiesis | –0.36 | 0.0008 |

| M3.6 | Cytotoxic/NK Cell | –0.334 | 0.0147 |

| M4.5 | Protein synthesis | –0.249 | 0.0025 |

| M6.7 | Lymphoid lineage | –0.24 | 0.0109 |

| M5.9 | Protein synthesis | –0.233 | 0.0403 |

| M4.7 | Lymphoid lineage | –0.232 | 0.0236 |

| M4.15 | Cytotoxic/NK cell | –0.228 | 0.0378 |

| M4.8a | –0.206 | 0.027 | |

| M6.5a | –0.202 | 0.0059 |

FC: fold change;

undetermined.

The comparison of baseline stable to baseline evolving PreSSc samples did not yield any differentially expressed modules (neither at prespecified thresholds nor at nominal P < 0.05), indicating that the PBC molecular profile of stable and evolving patients is not significantly different at the baseline visit.

Pairwise comparison of follow-up to baseline samples at the modular level

As shown in Table 4, comparison of follow-up to baseline samples in patients with stable PreSSc indicated that cytotoxic/NK and protein synthesis modules increased during the follow-up time.

Table 4.

Differentially expressed modules in paired comparison of stable PreSSc at follow-up vs baseline visit

| Module | Module annotation | logFC | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| M5.9 | Protein synthesis | 0.2683 | 0.0031 |

| M4.3 | Protein synthesis | 0.2428 | 0.0194 |

| M4.5 | Protein synthesis | 0.2108 | 0.0061 |

| M3.6 | Cytotoxic/NK cell | 0.2038 | 0.0415 |

FC: fold change.

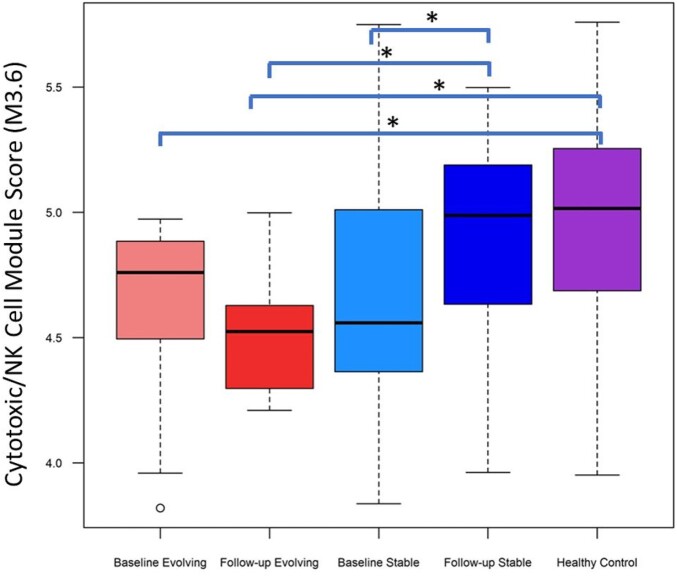

The comparison of follow-up to baseline samples in patients with evolving PreSSc indicated that there was minimal change in gene expression modules with only a significant increase in erythropoiesis module—M2.3 (logFC = 0.21, P = 0.019). These results indicate that stable PreSSc normalize their initial down-regulation cytotoxic/NK cell and protein synthesis module upon follow-up while evolving PreSSc continue showing a down-regulation cytotoxic/NK cell and protein synthesis modules. This finding is also supported by the fact that the only module that was differentially expressed in comparison of evolving to stable PreSSc at the follow-up visit was Cytotoxic/NK cell module-M3.6 (log FC = –0.38, P = 0.015) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The Cytotoxic/NK cell module scores in study groups. * indicates statistically significant differences in QuSAGE analysis. The follow-up vs baseline analyses compared each follow-up sample to the baseline samples of the same patient

Gene level changes in stable vs progressor group

Next, we examined the transcript level changes of follow-up vs baseline samples in stable PreSSc group in comparison to evolving PreSSc. This comparison showed 549 differentially expressed transcripts (336 up-regulated and 213 down-regulated). A complete list of DEGs is included in an online supplemental data file (https://go.uth.edu/scleroderma-data). Fig. 1B shows the top ten Canonical Pathway analysis based on this comparison. In agreement with QuSAGE modular analysis, protein synthesis related Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (EIF2) Signalling pathway was upregulated. Moreover, the T-cell related Granzyme A Signalling pathway was overrepresented.

Discussion

The present project explored SSc subjects at a preclinical stage of disease and for the first time the PBCs global gene expression profile was assessed in a cohort of PreSSc with characterization both at baseline and after four years of observation. Based on modular analysis, transcripts signatures emerged at characterizing preclinical patients prone to disease progression and distinguishing PreSSc from healthy controls.

At baseline, evolving PreSSc and stable PreSSc showed comparable clinical features: similar FVC%, DLCO%, autoantibody profile, upper GI involvement and disease duration (number of years since RP onset). Almost all PreSSc subjects, 31 out of 33, had on top of RP both ANA positive and a video-capillaroscopy positive for scleroderma pattern. After average four years of observation, 42.4% of PreSSc patients progressed to a definite SSc diagnosis (thus reaching the score of 9 based on the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria). Our data are in line with the previous observation by Koenig and colleagues that followed-up 586 consecutive patients presenting with RP for >10 years. They found that SSc is a progressive disease in which capillaroscopy abnormalities and/or specific autoantibodies predict independently progression. When both capillaroscopy abnormalities and specific autoantibodies were present, 65.9% subjects progressed into a definite SSc in 5 years, 72.7% in 10 years and 79.5% at the end of follow-up (about 20 years) [3]. Moreover, a very recent multicentre longitudinal EUSTAR study investigated the clinical value of the VEDOSS criteria in detecting definite SSc progression of subjects presenting with RP. This study showed that the absence of ANA is predictive of a lack of progression while ANA positivity and the presence of puffy fingers predicted the highest rate of progression towards a definite SSc (that fulfils 2013ACR/EULAR criteria) [13]. The uniqueness of our PreSSc cohort is that it was characterized at baseline by PreSSc without even puffy fingers, that is typically the very first skin feature. At follow-up the appearance of puffy fingers and/or other clinical features determined their progression reaching ≥ the score of 9 based on the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria.

Paralleling our observations at the clinical level, the baseline PBCs gene expression did not predict disease progression. In comparison to healthy controls that were age and ethnicity matched and belonged to the same geographical area like patients, the overall PreSSc group showed at baseline a decrease of several modules (Erythropoiesis M 6.18 and M2.3, Cytotoxic/NK module M3.6 and M4.15, Protein Synthesis M4.5 and M 5.9, Lymphoid Lineage M 6.7 and M 4.7) while Interferon modules 1.2 and 3.4 showed a trend for higher expression values. Also in the Canonical pathways of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, interferon signalling was the only activated pathway, aligning with prior observations of a type I IFN signature in SSc patients, as well as in preclinical SSc [6, 14–16]. In general, we can conclude that the overall PreSSc group has a distinct PBCs gene expression profile in comparison to healthy controls highlighting that these individuals without definite clinical signs or symptoms of SSc (except for RP) already manifest clear biomolecular differences worthy to be further explored for understanding the very early pathogenetic steps of this disease.

Notably, the Cytotoxic/NK modules that were found decreased at baseline in the overall PreSSc group were still decreased in the comparison of follow-up to baseline samples of evolving PreSSc. In contrast, stable PreSSc showed an increase of the NK signature over time. This observation indicates that stable PreSSc normalize over time their initial down-regulation of cytotoxic/NK cell while evolving PreSSc show a persistent down-regulation of cytotoxic/NK cell, as well as of protein synthesis modules. In line with our results that associate a decreased NK signature with the progression and thus the appearance of definitive SSc, a reduced cytotoxic/NK module was observed in PBCs of SCOT trial participants (all of whom had dcSSc) and an independent sample from GENISOS cohort. Notably, myeloablation followed by autologous stem cell transplantation led to significant increases in the PBC NK module scores and normalization of this signature while treatment with intravenous monthly cyclophosphamide did not have a similar effect. Moreover, the NK module score showed a significant negative correlation with modified Rodnan Skin Score (mRSS) at the baseline visit (that is, a low NK score correlated with a high mRSS) and an increase in the NK module score correlated significantly with a decline (improvement) in mRSS (rS = –0.56) after treatment in the SCOT study [11]. The findings of the current study focusing on early disease progression and the molecular studies in the SCOT trial focusing on transplant-induced disease ‘regression’ provide complementary evidence for linking the decreased peripheral blood NK gene expression signature to skin fibrosis. Moreover, immunophenotyping performed in 162 SSc belonging to two different large European SSc cohorts, one from the southern Europe and the other from central-western Europe, showed a reduction in the number of circulating NK cells in comparison to healthy controls in both cohorts [17].

The biological significance of an NK reduction in peripheral blood or tissues has been investigated in different diseases and autoimmune conditions. The NK cells mainly consist of two subsets, the CD56dim CD16+ NK subset which is more cytotoxic and CD56bright CD16– subset which produces abundant cytokines and plays an important immunoregulatory role [18]. Several studies suggested an anti-fibrotic role of NK cells in liver fibrosis through the regulation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) that can differentiate into myofibroblasts and contribute to collagen deposition. In mice carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis model, NK cells can eliminate senescent HSCs during fibrosis progression and clinical observations showed that a subset of NK cells is decreased in the peripheral blood and in liver of patients with chronic HBV infection at advanced stages of fibrosis [18–22]. NK cells have been shown to suppress cardiac fibrosis in experimental autoimmune myocarditis and depletion of NK cells exacerbated cardiac fibrosis [23]. Moreover, a peripheral blood NK reduction was also extensively observed in systemic lupus erythematosus, particularly in active forms of SLE [21, 24–28]. Future studies are needed to elucidate the role of NKs in SSc and in particular their eventual contribution to disease progression.

Our analysis based on Canonical Pathway changes in comparison of follow-up to baseline samples in stable PreSSc vs evolving PreSSc showed the upregulation of EIF2 Signalling pathway. EIF2 is the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 that has a fundamental role in the initiation of mRNA translation to proteins in eukaryotic cells. In condition of stress, protein kinases phosphorylate EIF2 determining a consequent suppression of mRNA translation, protecting cells against endoplasmic reticulum stress [29, 30]. Among stress factors, viral and bacterial infections induce in response a reduction of EIF2 function with consequent reduction of general protein synthesis and thus decreased viral replication [31, 32]. The EIF2 regulation is also involved in innate immune responses [33]. It is unknown how these processes are related to observed increased EIF2 signalling in stable PreSSc vs evolving PreSSc. We can hypothesize that mechanisms involved in the controlling of inflammation and/or innate immunity could be an explanation.

The present project had several strengths. To our knowledge, our study is the first global gene expression analysis in PreSSc subjects with the novelty of investigating the very first biomolecular features in the shift between a preclinical to clinical phase of the disease. Also, PreSSc with homogeneous clinical features and with a careful clinical characterization along with comparison to matched healthy controls were investigated.

The present study has also some limitations such as the modest sample size; mainly due to the logistical difficulty in intercepting and identifying patients at a preclinical stage in a rare autoimmune disease. Although disease duration was homogeneous among the groups, participants had a relatively long time interval from the onset of RP at the baseline visit. This might represent a selection bias for slow progressors. Same finding of a possible bias towards detection of lcSSc in comparison to dcSSc was also observed in the recent VEDOSS EUSTAR study [13]. To better stratify the risk of progression, future studies are needed that create the necessary awareness and infrastructure for referral to the specialized assessment centres within a short time interval after RP onset. Also, although haemoglobin depletion was performed, the heterogeneity of RNA gene expression coming from peripheral blood cells may have impacted the present study. Lastly, we were not able to provide skin biopsies in order to investigate skin gene expression and its possible correlation with the inverse peripheral blood NK cell signature.

In conclusion, the present study showed that subjects with preclinical SSc have a distinct PBC gene expression profile in comparison to healthy controls, indicating that immune perturbations are present in the early stages of disease. Moreover, patients with a progressive course continued showing a reduced NK signature on follow-up while those with non-progressive course normalized their NK signature, linking this signature to onset of fibrosis in SSc. The overall findings of the present study set the stage for follow-up biomolecular and mechanistic investigations in preclinical SSc.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Chiara Bellocchi, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; Scleroderma Unit, Referral Center for Systemic Autoimmune Diseases, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

Lorenzo Beretta, Scleroderma Unit, Referral Center for Systemic Autoimmune Diseases, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

Xuan Wang, Biostatistics, Baylor Institute for Immunology Research, Dallas, TX, USA.

Marka A Lyons, Rheumatology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Maurizio Marchini, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Maurizio Lorini, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Vincenzo Carbonelli, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Nicola Montano, Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Shervin Assassi, Rheumatology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Data availability statement

Dataset analysed in the present study are available at https://go.uth.edu/scleroderma-data.

Funding

This work was supported by Gruppo Italiano per la Lotta alla Sclerodermia GILS Bando Giovani Ricercatori (Sep 2017) and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R61AR078078, R56AR078211).

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J. et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LeRoy EC, Medsger TA.. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koenig M, Joyal F, Fritzler MJ, Roussin A. et al. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3902–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minier T, Guiducci S, Bellando-Randone S. et al. Preliminary analysis of the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis (VEDOSS) EUSTAR multicentre study: evidence for puffy fingers as a pivotal sign for suspicion of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:2087–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellando-Randone S, Matucci-Cerinic M.. Very early systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019;33:101428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brkic Z, van Bon L, Cossu M. et al. The interferon type I signature is present in systemic sclerosis before overt fibrosis and might contribute to its pathogenesis through high BAFF gene expression and high collagen synthesis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;75:1567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vettori S, Cuomo G, Iudici M. et al. Early systemic sclerosis: serum profiling of factors involved in endothelial, T-cell, and fibroblast interplay is marked by elevated interleukin-33 levels. J Clin Immunol 2014;34:663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cossu M, van Bon L, Preti C. et al. Earliest phase of systemic sclerosis typified by increased levels of inflammatory proteins in the serum. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crescioli C, Corinaldesi C, Riccieri V. et al. Association of circulating CXCL10 and CXCL11 with systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1845–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chaussabel D, Baldwin N.. Democratizing systems immunology with modular transcriptional repertoire analyses. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:271–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Assassi S, Wang X, Chen G. et al. Myeloablation followed by autologous stem cell transplantation normalises systemic sclerosis molecular signatures. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1371–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yaari G, Bolen CR, Thakar J, Kleinstein SH.. Quantitative set analysis for gene expression: a method to quantify gene set differential expression including gene-gene correlations. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bellando-Randone S, Del Galdo F, Lepri G. et al. Progression of patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a five-year analysis of the European Scleroderma Trial and Research group multicentre, longitudinal registry study for Very Early Diagnosis of Systemic Sclerosis (VEDOSS). Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e834–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan FK, Zhou X, Mayes MD. et al. Signatures of differentially regulated interferon gene expression and vasculotrophism in the peripheral blood cells of systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology 2006;45:694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. York MR, Nagai T, Mangini AJ. et al. A macrophage marker, Siglec-1, is increased on circulating monocytes in patients with systemic sclerosis and induced by type I interferons and toll-like receptor agonists. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1010–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu X, Mayes MD, Tan FK. et al. Correlation of interferon-inducible chemokine plasma levels with disease severity in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beretta L, Barturen G, Vigone B. et al. Genome-wide whole blood transcriptome profiling in a large European cohort of systemic sclerosis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1218–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schleinitz N, Vély F, Harlé J-R, Vivier E.. Natural killer cells in human autoimmune diseases. Immunology 2010;131:451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou X, Yu L, Zhou M. et al. Dihydromyricetin ameliorates liver fibrosis via inhibition of hepatic stellate cells by inducing autophagy and natural killer cell-mediated killing effect. Nutr Metab 2021;18:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi W-M, Ryu T, Lee J-H. et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in natural killer cells attenuates liver fibrosis by exerting cytotoxicity to activated stellate cells. Hepatology 2021;74:2170–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yabuhara A, Yang FC, Nakazawa T. et al. A killing defect of natural killer cells as an underlying immunologic abnormality in childhood systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 1996;23:171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wan M, Han J, Ding L, Hu F, Gao P.. Novel immune subsets and related cytokines: emerging players in the progression of liver fibrosis. Front Med 2021;8:604894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ong S, Ligons DL, Barin JG. et al. Natural killer cells limit cardiac inflammation and fibrosis by halting eosinophil infiltration. Am J Pathol 2015;185:847–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hervier B, Ribon M, Tarantino N. et al. Increased concentrations of circulating soluble MHC Class I-Related Chain A (sMICA) and sMICB and modulation of plasma membrane MICA expression: potential mechanisms and correlation with natural killer cell activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol 2021;12:633658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Humbel M, Bellanger F, Fluder N. et al. Restoration of NK cell cytotoxic function with elotuzumab and daratumumab promotes elimination of circulating plasma cells in patients with SLE. Front Immunol 2021;12:645478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henriques A, Teixeira L, Inês L. et al. NK cells dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus: relation to disease activity. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin S-J, Kuo M-L, Hsiao H-S. et al. Activating and inhibitory receptors on natural killer cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosis-regulation with interleukin-15. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spada R, Rojas JM, Barber DF.. Recent findings on the role of natural killer cells in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Leukoc Biol 2015;98:479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Proud CG.. The role of eIF2 phosphorylation in cell and organismal physiology: new roles for well-known actors. Biochem J 2022;479:1059–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG.. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 2009;136:731–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shrestha N, Bahnan W, Wiley DJ. et al. Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2) signaling regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression and bacterial invasion. J Biol Chem 2012;287:28738–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. García MA, Meurs EF, Esteban M.. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: virus and cell control. Biochimie 2007;89:799–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woo CW, Cui D, Arellano J. et al. Adaptive suppression of the ATF4–CHOP branch of the unfolded protein response by toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11:1473–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Dataset analysed in the present study are available at https://go.uth.edu/scleroderma-data.