Abstract

Background:

There is considerable heterogeneity in symptom burden among lung transplant candidates that may not be explained by objective measures of illness severity.

Objectives:

This study aimed to characterize symptom burden, identify distinct profiles based on symptom burden and illness severity, and determine whether observed profiles are defined by differences in social determinates of health (SDOH).

Methods:

This was a prospective study of adult lung transplant candidates. Symptoms were assessed within 3 months of transplant with the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS). MSAS subscale (physical and psychological) scores range 0–4 (higher=more symptom burden). The lung allocation score (LAS) (range 0–100) was our proxy measure of illness severity. The MSAS subscales and LAS were used as continuous indicators in a latent profile analysis to identify distinct symptom-illness severity profiles. Comparative statistics were used to identify SDOH differences among observed profiles.

Results:

Among 93 candidates, 3 distinct symptom-illness severity profiles were identified: 71% had a mild profile in which mild symptoms (MSAS physical 0.49; MSAS psychological 0.57) paired with mild illness severity (LAS 38.59). Of the 29% mismatched participants, 9% had moderate symptoms (MSAS physical 0.88; MSAS psychological 1.47) but severe illness severity (LAS 88.02) and 20% had severe symptoms (MSAS physical 1.30; MSAS psychological 1.94) but mild illness severity (LAS 42.13). The two mismatch profiles were younger, more racially diverse, and had higher psychosocial risk scores.

Conclusion:

Symptom burden is heterogenous, does not always reflect objective measures of illness severity, and may be linked to SDOH.

Keywords: lung transplantation, symptoms, quality of life, patient reported outcomes, social determinants of health

Introduction

While thousands of individuals benefit from a successful organ transplantation each year, a far greater number die without receiving a transplant.1 This is due to low referral rates, inequitable access to the wait list, and a persistent shortage of organs. These issues prompted the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to conduct a review of the inequities in the United States (US) organ transplantation system and identify opportunities for improvement. The NASEM 2022 report2 reveals demonstrable inequities in the patient experience across the transplant trajectory from referral for transplant, wait listing, receiving a transplant, and clinical outcomes based on nonmedical social determinants of health (SDOH) such as race and ethnicity, gender, geographic location, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors. The NASEM report urges the US organ transplantation system to address these inequities. Also, to improve the patient experience of needing, waiting for, and living with an organ transplant, the report emphasizes the need to focus on the outcomes that matter most to transplant patients, referred to as patient centered outcomes. At this point, we neither routinely collect nor evaluate patient centered outcomes in transplantation and therefore, we know very little about patient centered outcomes and the patient experience of waiting for an organ transplantation.

Individuals with end stage lung failure seek organ transplantation for extended survival, but also for palliation of symptoms.3 Symptoms are an important patient centered outcome that impacts clinical outcomes and health-related quality of life in end stage organ failure populations.4–7 While waiting for lung transplant, we know that candidates experience frequent and distressing physical and psychological symptoms that contribute to an overall symptom burden.8 The wait for a lung transplant is unpredictable; some wait days, months, or even sometimes years depending on objective medical factors that represent a candidate’s severity of illness and medical urgency.1 There is considerable heterogeneity in symptom burden among candidates, even among those with the same underlying disease process.6 One might expect that illness severity accounts for this heterogeneity, but there is growing recognition of incongruence between the severity of symptoms subjectively experienced and the severity of illness objectively measured.5,9 Whether severity of symptom burden is congruent with a patient’s severity of illness or whether this disconnect exists among lung transplant candidates and for whom has yet to be determined. If symptom burden is not solely dependent on severity of illness, it is important to identify what other factors may contribute to heterogeneity in symptom burden. There is growing interest in how SDOH contribute to differences in clinical and patient centered outcomes.10 The SDOH are the economic and social conditions that influence an individual’s differences in health status.11 In transplant candidates, whether SDOH are linked to patient centered outcomes remains understudied.

This study addresses the NASEM report’s key recommendation to focus the organ transplantation system on the patient experience of waiting for an organ transplant. The aims of our study are to: 1) characterize symptom burden among lung transplant candidates, 2) identify distinct profiles using integrated data on symptom burden and an objective measure of illness severity, and 3) identify whether observed profiles are defined by differences in SDOH. Integrating subjective symptom data that reflect how patients feel and objective data that reflect illness severity to identify unique patient profiles can identify actionable ways to improve the transplant patient experience. Further, determining whether these profiles are defined by differences in SDOH may uncover disparities in organ transplantation that must be addressed if we are to improve outcomes for transplant patients.

Methods:

Study Design and Participants

This was a prospective cohort study of adult (≥18 years) candidates listed between February 2019 and January 2021 for a first-time single or bilateral lung transplant at a high-volume university-affiliated transplant center in the northeastern US. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1 In summary, all participants were able to communicate verbally and read and speak English. We excluded patients listed for a multi-organ transplant and patients who were mechanically ventilated, unable to communicate, or unwilling to provide informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university (Protocol #832441).

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Adults (age ≥18 years) |

| Listed for a first-time lung transplant |

| Able to communicate verbally |

| Able to read and speak English |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Children (age <17 years) |

| Mechanically ventilated |

| Listed for a multi-organ transplantation |

| Listed for a redo lung transplantation |

| Unwilling to provide informed consent |

Study Procedures

Eligible patients were identified by reviewing the electronic medical record (EMR) of candidates listed for lung transplantation. All patients willing to participate provided informed consent and completed a symptom survey at enrollment. Because the date of transplant surgery is unpredictable, participants completed the symptom survey every 3 months until transplant surgery in effort to standardize the timing of data collection to within 3 months of surgery. The most recent measurement of symptoms, assessed closest to the date of transplant, was used for analysis. Clinical and SDOH data were abstracted from the electronic health record (EHR) at enrollment and at each subsequent study visit. All data collected at the study visit closest to the date of transplant were used for analyses.

Measurement

Clinical and SDOH data were abstracted from the EMR. Clinical data included lung diagnosis, lung allocation score, 6-minute walk test distance, history of cigarette use and pack year history, body mass index, number of prescribed medications and antidepressant, benzodiazepine, sleep aid, and opioid use. SDOH data included age, sex, race, employment status, educational attainment, health insurance coverage, marital status, relationship of social support person, and psychosocial risk score. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant (SIPAT) is used by many transplant programs to assess patients’ psychosocial risk factors. The SIPAT divides psychosocial risk factors into four domains: 1) patient readiness level, illness knowledge, and understanding of illness management, 2) social support system readiness, 3) psychological stability and psychopathology, and 4) lifestyle and effect of substance use. SIPAT scores range from 0 to 119; higher scores indicate greater psychosocial risk.12 We also assessed patient’s perceived financial status (“Considering how well your household lives on its income, financially, would you say you are: comfortable, have enough to make ends meet, or do not have enough to make ends meet?”) and perception of support quality (“How would you rate the quality of support you receive (emotional and physical support, information, etc.): poor, satisfactory, good, very good?”).

Symptom Measurement

We measured symptoms using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) for the week preceding the study visit.13 The MSAS is a self- reported instrument, developed to assess multidimensional information (frequency, severity, and distress) about 32 physical and psychological symptoms. Frequency and severity are reported using a 4-point scale and distress is reported using a 5-point scale. A symptom burden score is calculated for each symptom by averaging severity, frequency, and distress. The symptom burden scores are combined into subscales. The psychological subscale is the average of the symptom burden scores for six psychological symptoms (feeling sad, irritable, nervous, difficulty sleeping or concentrating, and worrying). The physical subscale is the average of the symptom burden scores for 12 physical symptoms (lack of appetite or energy, feeling drowsy or bloated, pain, constipation, dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, dizziness and change in taste). The total MSAS is the average of the symptom burden scores for all 32 symptoms, including respiratory symptoms. Individual symptom burden scores and subscale scores range 0 to 4. Higher scores indicate greater symptom burden, but floor effects are common because if a patient does not experience a specific symptom, this is scored as 0 and pulls the overall symptom burden score down.6,13 The MSAS has been established as a valid and reliable instrument to assess symptoms of patients with lung disease.9,14,15

Severity of Illness

We used the lung allocation score (LAS) as our proxy measure of illness severity. The US lung allocation system requires that every lung transplant candidate have an updated LAS that estimates the candidate’s severity of illness and expected post-transplant survival rate. The LAS is a composite score ranging 0 to 100 based on objective physiological and comorbid patient variables. The US lung transplant system uses the LAS to determine priority for receiving a lung transplant when a donor becomes available; a candidate with a higher LAS has a greater severity of illness and is prioritized for a lung offer compared to a candidate with a lower LAS.16 Therefore, we characterized patients with a higher LAS (on a continuous scale) as those with greater severity of illness. We obtained the participant’s LAS that most closely corresponded to the date the participant completed their symptom assessment from the EHR.

Statistical Analysis

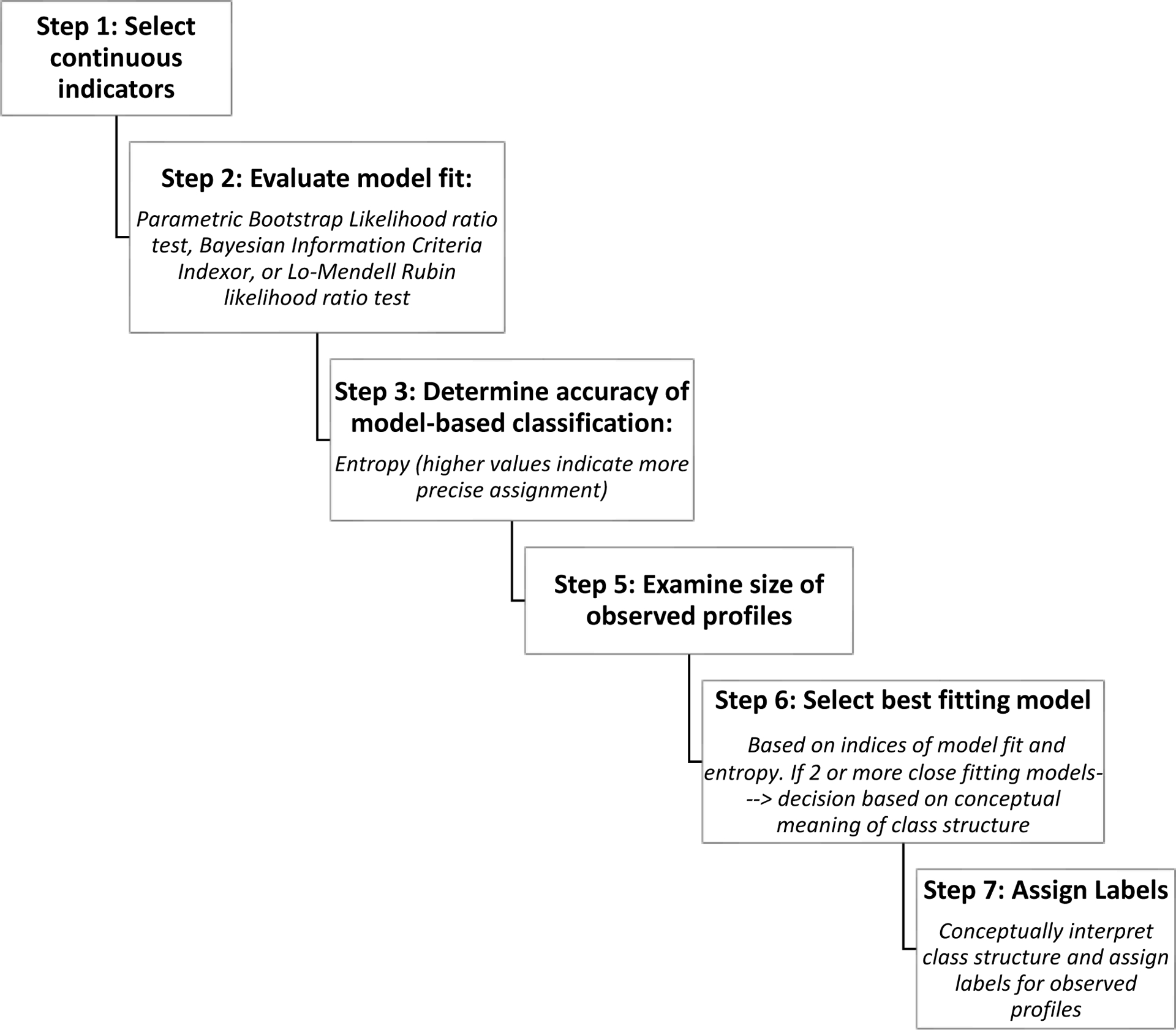

We used latent profile analysis to identify distinct patient profiles based on symptom burden and illness severity; analyses were done using MPlus software (Figure 1).17,18 The MSAS psychological and physical subscales and the LAS were used as continuous indicators. We fit a latent class model based on (1) the parametric bootstrap likelihood ratio test to test the number of classes, (2) model entropy to assess the precision of assigning latent class with a cutoff of 0.80, and 3) the size of the observed profiles (not < 5% of the sample). The parametric bootstrap likelihood ratio test compares the log-likelihood ratio from the estimated model to that from a model with one fewer classes; a significant value indicates that the estimate model fits the data significantly better than a model with one fewer classes.18 Owing to our relatively small sample size we fit 2 and 3 class models.

Figure 1. Latent Profile Analysis Method Flowchart.

This figure presents procedural steps in the latent profile statistical analysis.

Categorical variables were summarized as percentages and continuous variables were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR). We compared individual symptom burden scores across profiles using non-parametric Kruskal Wallis. We examined differences in clinical factors and SDOH across profiles using non-parametric Kruskal Wallis for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. We performed pairwise comparisons using Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Flinger Method for continuous variables and two proportion Z-test for categorical variables. Owing to our sample size and exploratory nature of our investigation we did not adjust for multiple comparison and considered type I error rate=0.05.

Results

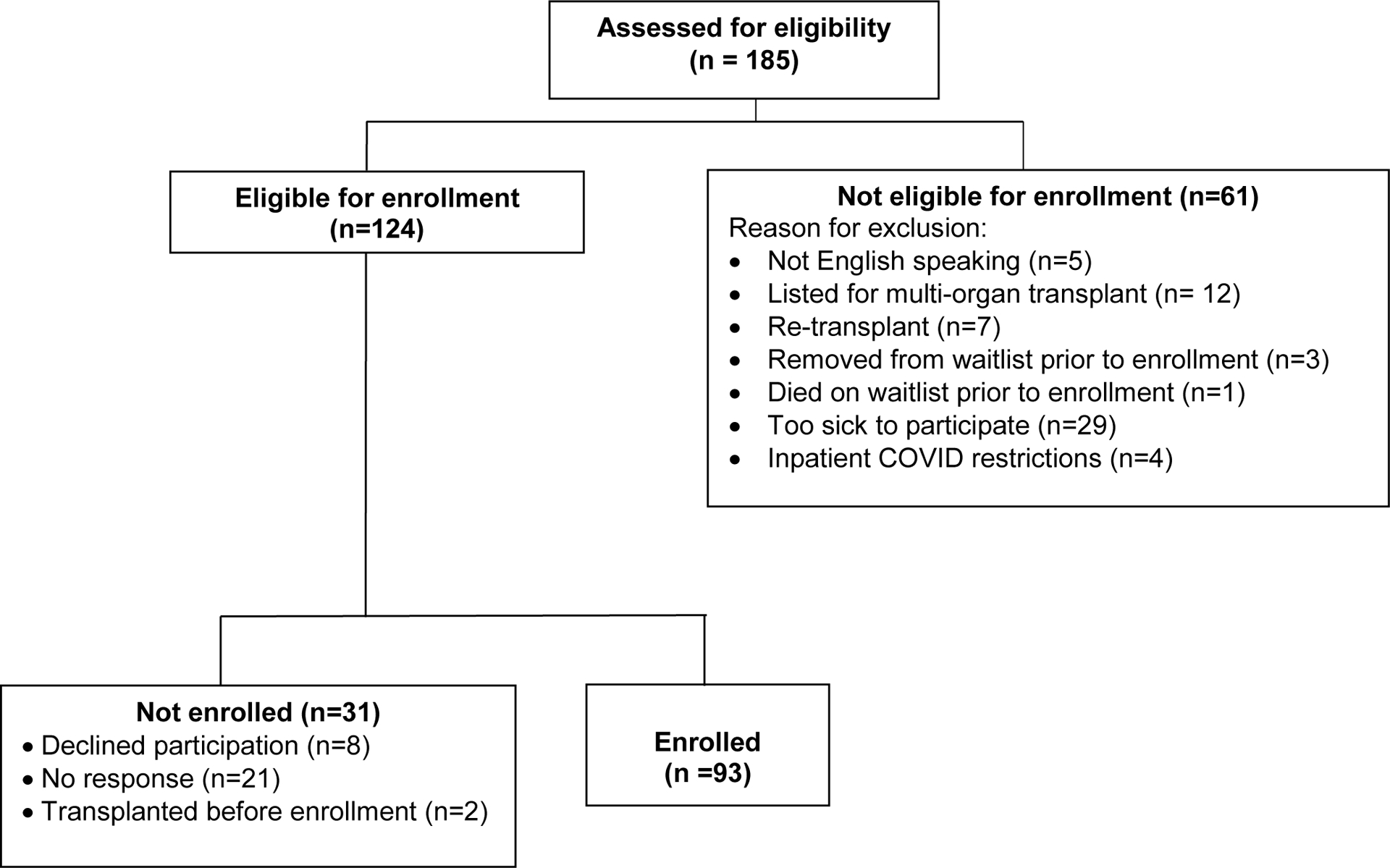

The study flow diagram (Figure 2) presents data on participants who were screened, eligible, and enrolled. A total of 93 transplant candidates were enrolled; this is 74% of those who were eligible to participate during our enrollment period. Clinical and SDOH characteristics are presented in Table 2. The typical participant was an older white adult; over half were female. Most were college educated but few were working at the time of transplant listing. Most were publicly insured. Clinically, about half the cohort had restrictive lung disease and the median LAS was 39.4.

Figure 2. Study Flow Diagram.

This figure presents the participant enrollment process: eligibility prescreens, recruitment, and enrollment.

Table 2.

Participants’ Clinical and Social Determinant of Health Characteristics

| Social Determinant of Health Characteristics | Total Cohort (N= 93) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (Q1,Q3) | 62 (52.0.67.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (53.8) |

| White, non-Hispanic n (%) | 75 (80.7) |

| College educated, n (%) | 62 (66.7) |

| Working for income, n (%) | 17 (18.3) |

| Private Insurance, n (%) | 41 (44.1) |

| Married/in a relationship, n (%) | 57 (61.3) |

| Primary support person, spouse/significant other, n (%) | 58 (62.4) |

| Patient reported financial status, “Does not have enough to make ends meet,” n (%) | 8 (8.6) |

| Patient reported quality of support, “satisfactory” or “poor,” n (%) | 3 (3.2) |

| SIPAT score, median (QR) | 9.0 (9.0) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Restrictive Lung Disease | 48 (51.6) |

| LAS, median (Q1,Q3) | 39.43 (34.16,47.35) |

| History of Cigarette use (yes), n (%) | 24 (50.0) |

| Pack year history median (Q1,Q3) | 20 (0, 40.0) |

| BMI, median (Q1,Q3) | 26.22 (21.98, 30.74) |

| Number of prescribed medications, median (Q1,Q3) | 12 (9.0, 16.0) |

| Antidepressants use, n (%) | 32 (34.4) |

| Benzodiazepine use, n (%) | 31 (33.3) |

| Sleep Aid use, n (%) | 16 (17.2) |

| Opioid use, n (%) | 12 (12.9) |

| Oral Corticosteroid use, n (%) | 49 (52.7) |

| 6 MWT distance (meters), median (Q1,Q3) | 239.57 (164.5,315.7) |

6MWT distance= 6-minute walk test distance; BMI= Body Mass Index; IQR=interquartile range; LAS= Lung Allocation Score; SIPAT= Stanford Integrate Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant;

Symptom Burden of Study Cohort

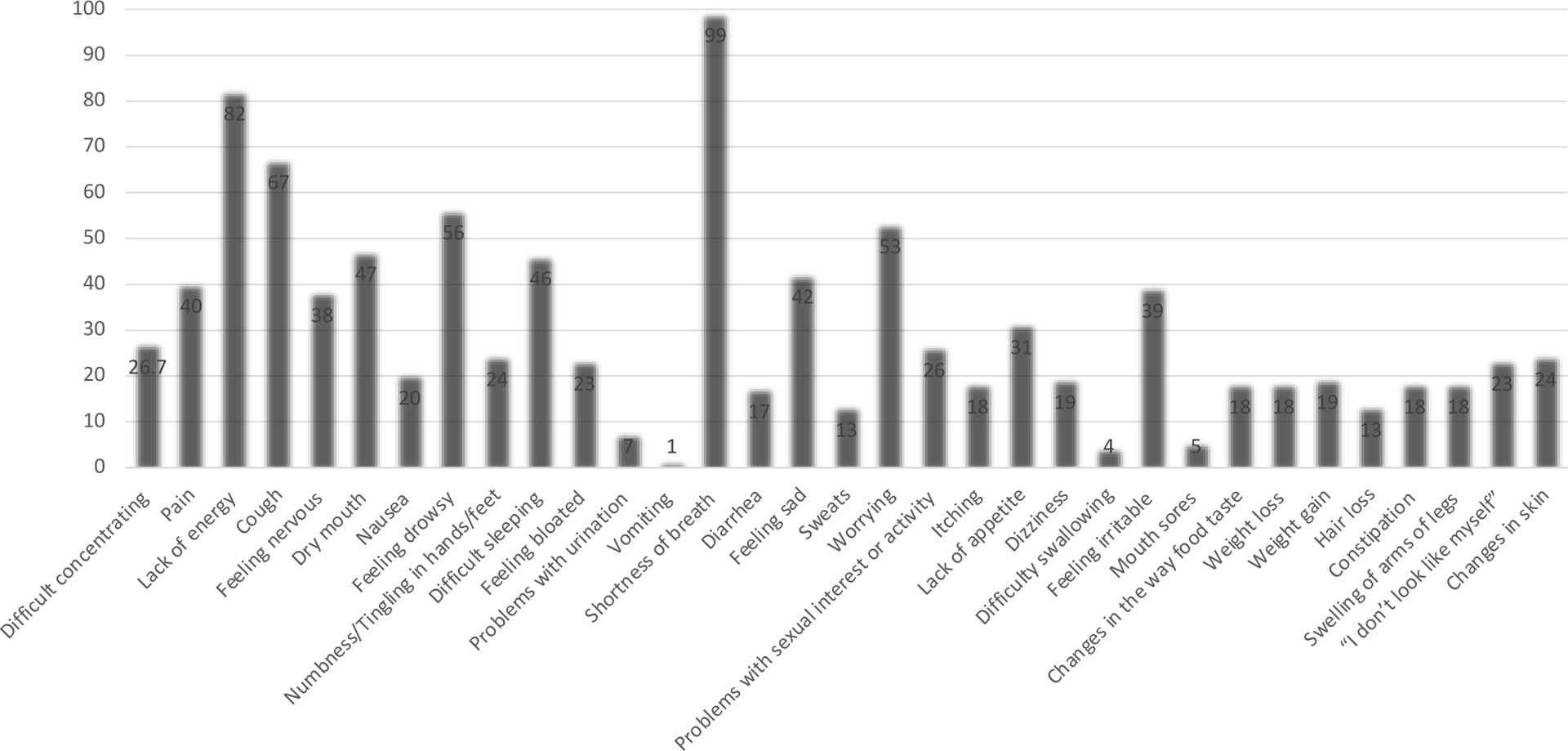

Symptoms were prevalent prior to lung transplant (Figure 3). Some symptoms were reported as severe, frequent, and distressing (Supplement Table 1). Almost the entire cohort experienced shortness of breath and most reported it to be severe, frequent, and very distressing. Patients were also burdened with several co-occurring physical (lack of energy, drowsy, pain, and cough) and psychological (worry, nervous, sad, and difficulty sleeping) symptoms.

Figure 3: Symptom Prevalence Among Study Cohort.

This figure presents Symptoms prevalence: the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS)

Distinct Patient Profiles

Given our modest sample size, we used parametric bootstrap likelihood ratio test to determine model fit. We fit latent class models for 2 and 3 profiles using all 93 participants. Our final model selection was a three-class model supported by a statistically significant measure of fit, good separation of profiles, and class structure that provided the most clinically meaningful conceptual interpretation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Latent Profile Analysis Model Fit Statistics

| Classes | Parametric Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test | Entropy | Number of Individuals Per Latent Class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 2 | <0.0001 | 0.98 | 84 | 9 | |

| 3 | <0.0001 | 0.84 | 66 | 8 | 19 |

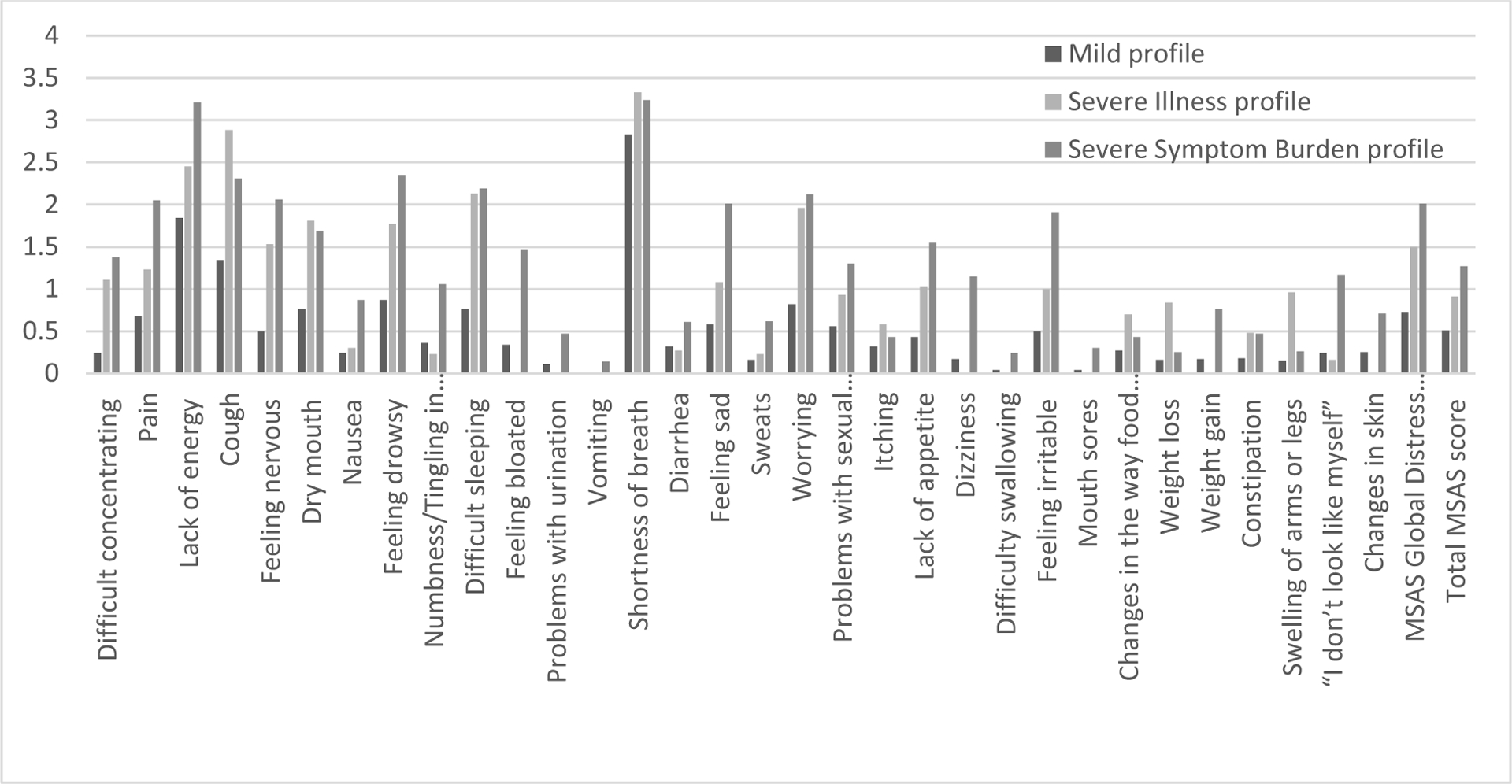

Next, we assigned labels to observed profiles. A majority (n=66, 71%) of participants were classified in a “mild profile” meaning they had mild physical and psychological symptom burden (physical subscale 0.49; psychological subscale 0.57) and mild illness severity reflected by an LAS (38.59) that was similar to the US national average. Among the remaining 29% of the cohort, we observed two profiles with a mismatch in subjective symptom burden and objective severity of illness.

One mismatch profile (n=8, 9%) was characterized by a moderate physical and psychological symptom burden profile (physical subscale 0.88; psychological subscale 1.47) and a severe illness severity profile reflected by a high LAS (88.02). This profile was defined by its severity of illness and thus labeled as the “severe illness” profile.

The other mismatch profile (n=19, 20%) was characterized by the most severe physical and psychological symptom burden profile (physical subscale 1.30; psychological subscale 1.94) and a moderate illness severity profile reflected by a relatively average LAS (42.13), compared to the national average LAS at the time of transplant. This profile was defined by having the highest symptom burden and thus we labeled this group as the “severe symptom burden” profile.

Clinical Differences by Profile

The three profiles had relatively similar clinical characteristics. Profiles were similar in the composition of lung diagnoses, with most candidates diagnosed with restrictive lung disease. Other clinical factors including history of cigarette use, body mass index, and number of currently prescribed medications were also similar across all three profiles. Significant differences were observed in LAS scores, 6-minute walk test distance, and medication use. The severe illness profile with the highest LAS walked only about half the distance in 6-minutes compared to the severe symptom and mild profiles. Compared to the mild profile, the severe symptom burden profile was significantly more often prescribed antidepressants and opioids and, although not significant, was also more often prescribed benzodiazepines and sleep aids. The proportion of those transplanted during our study period and the median wait time significantly differed by profile; the severe symptom burden profile had the longest median wait time compared to the mild and severe illness profile (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient Characteristics by Profile

| Characteristics of the sample | Mild profile (MP) (n=66) | Severe Illness Profile (SIP) (n=8) | Severe Symptom Burden profile (SSP) (n=19) | p-value | Post-hoc comparison (profile comparison, p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Determinant of Health Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years), median (Q1,Q3) | 65.5 (55.0, 67.0) | 53.5 (47.5, 64.0) | 52.0 (44.0,62.0) | 0.008 | SSBP-MP 0.017 |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (48.5) | 4 (50.0) | 14 (73.7) | 0.16 | |

| White, non-Hispanic n (%) | 58 (87.9) | 5 (62.5) | 12 (63.2) | 0.02 | SSBP-MP 0.018 |

| College educated, n (%) | 44 (66.7) | 4 (50.0) | 14 (73.7) | 0.55 | |

| Working for income, n (%) | 14 (21.2) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (10.5) | 0.35 | |

| Private Insurance, n (%) | 27 (40.9) | 4 (50.0) | 10 (52.6) | 0.66 | |

| Married/in a relationship, n (%) | 42 (63.6) | 4 (50.0) | 11 (57.9) | 0.69 | |

| Primary support person, spouse/significant other, n (%) | 44 (66.7) | 3 (37.5) | 11 (57.9) | 0.25 | |

| Patient reported financial status, “Does not have enough to make ends meet,” n (%) | 4 (6.1) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0.05 | |

| Patient reported quality of support, “satisfactory” or “poor,” n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (10.5) | 0.02 | |

| SIPAT score, median (Q1,Q3) | 7.5 (4.0, 10.0) | 10.5 (5.50,18.50) | 13.0 (5.0,17.0) | 0.03 | SSBP-MP 0.045 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| Restrictive Lung Disease | 33 (50.0) | 6 (75.0) | 9 (47.4) | ||

| LAS, median (Q1,Q3) | 38.6 (33.55, 42.97) | 88.0 (74.32,90.71) | 42.1 (37.11, 48.61) | <0.001 | SSBP-SIP <0.001 SIP-MP < 0.001 |

| History of Cigarette use (yes), n (%) | 16 (53.3) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.92 | |

| Pack year history, median (Q1,Q3) | 20.0 (0, 40.0) | 15.0 (0, 25.0) | 3.0 (0, 35.0) | 0.30 | |

| BMI, median (Q1,Q3) | 26.3 (21.93, 30.74) | 30.9 (24.08, 33.76) | 24.5 (21.61,29.84) | 0.18 | |

| Number of prescribed medications, median (Q1,Q3) | 12.0 (9.0, 15.0) | 12.5 (10.5,16.0) | 15.0 (10.0,18.0) | 0.19 | |

| Antidepressants use, n (%) | 20 (30.3) | 1 (12.5) | 11 (57.9) | 0.04 | SSBP-MP p = 0.032 |

| Benzodiazepine use, n (%) | 21 (31.8) | 2 (25.0) | 8 (42.1) | 0.67 | |

| Sleep Aid use, n (%) | 11 (16.7) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (21.1) | 0.90 | |

| Opioid use, n (%) | 6 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (31.6) | 0.03 | SSBP-MP p=0.019 |

| Oral Corticosteroid use, n (%) | 34 (51.5) | 5 (62.5) | 10 (52.6) | 0.89 | |

| 6 MWT distance (meters), median (Q1,Q3) | 239.57 (178.6,315.7) | 127.6 (106.3, 185.9) | 273.7 (166.4, 353.5) | 0.018 | SSBP-SIP 0.071 SIP-MP 0.033 |

| Time on Wait list, median (Q1,Q3) | 101.5 (43.0,319.0) | 19.5 (10.5,73.5) | 192.0 (59.0,245.0) | 0.0345 | |

| Transplanted, n (%) | 45 (68.2) | 8 (100) | 16 (84) | 0.08 | |

| Bilateral transplant, n (%) | 38 (65.2) | 6 (10.3) | 14 (24.1) | ||

6MWT distance= 6-minute walk test distance; BMI= Body Mass Index; IQR=interquartile range; LAS= Lung Allocation Score; MP= Mild Profile; SIP= Severe Illness Profile; Severe Symptom Burden Profile= SSBP SIPAT= Stanford Integrate Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant

p-values for significant post-hoc comparison are listed

Differences in SDOH by Profile

Some SDOH differed significantly across the three observed profiles. There were significant differences in age, race, SIPAT score, perceived financial status, and quality of support among the three profiles. The two mismatch profiles, the severe symptom profile and the severe illness profile, were younger, more racially diverse, and had greater psychosocial vulnerability compared to the mild profile. Although not statistically significant in this small sample size, a higher proportion of the severe symptom profile were female and a lower proportion were employed and married or in a relationship compared to the mild profile. (Table 4).

Differences in Symptoms

Symptom assessments were completed within 3 months of either transplant surgery, removal from the wait list, or the end of study period in most patients (73% of the cohort). Multidimensional symptom data is presented in the Supplementary (Supplement Table 2).

Most of the symptom burden scores were significantly different among the three profiles (Figure 4). Pairwise comparisons revealed that most of the symptom burden scores for the severe symptom burden profile, compared to the mild profile, were significantly higher. Significant differences in the total MSAS were observed among the three profiles (Figure 4; Supplement Table 3).

Figure 4. Total MSAS Symptom Burden Scores by Profile.

This figure presents symptom burden scores (score range 0–4, higher scores indicate severe symptom burden): the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS). Each symptom burden score is presented by the observed symptom profile.

Discussion

Symptoms remain largely understudied in the field of lung transplantation. We aimed to better understand heterogeneity in symptom burden in the lung transplant candidate population. Using the MSAS, we identified a high prevalence of physical and psychological symptoms and heterogenous symptom burden. Integrating subjective symptom data with objective clinical data, we identified three distinct patient profiles: a “mild” profile characterized by mild symptoms and illness severity and two mismatch profiles in which symptom severity and illness severity were not congruent. Researchers have cautioned against reliance on measures of illness severity because, for some patients, this is a poor predictor of symptom burden.19,20 Our findings confirm what clinicians have suspected, that symptom burden is heterogenous and does not always reflect objective measures of illness severity. These findings highlight a novel area of inequity in the organ transplantation system related to disparities in patient centered outcomes that are not explained by medical differences.

In our cohort, one in five participants had a more severe symptom burden than expected based on objective illness severity. Our severe symptom burden profile scored up to three times higher on the physical, psychological, global distress index, and total MSAS subscales compared to the mild profile. Yet objectively, these two profiles were similar in illness severity. Likewise, the severe symptom profile scored higher on the MSAS subscales compared to the severe illness profile who objectively, was exceedingly more critically ill. These findings highlight that symptom burden is highly heterogenous and measures of illness severity may not identify a subset of patients who are at greatest risk of experiencing a higher symptom burden. This led us to explore differences in nonmedical factors that may help explain heterogeneity in symptom burden among the three profiles.

Our findings suggest that heterogeneity in symptom burden may be linked to SDOH. Transplant candidates with the severe symptom profile and those with a moderate symptom burden, were younger, female, more racially diverse, and had greater psychosocial vulnerability compared to the mild profile with less severe symptom burden. While SDOH are associated with a wide range of health outcomes, the contribution of SDOH to symptom experiences is limited.21 The mechanisms that explain the relationship between SDOH and symptoms may be biological, behavioral or a combination of both. A disproportionate burden of lung disease occurs in people of lower socioeconomic status due to differences in health behaviors and social and environmental exposures. For example, tobacco use, air pollution, housing conditions, and occupations with exposure to inhalant toxins can influence underlying biological processes that give rise to lung disease.22,23 People of lower socioeconomic status tend to have greater exposure to these factors. SDOH are not only linked to the risk of developing lung disease, but also are associated with worse health outcomes.22 The role of SDOH in explaining differences in symptom burden and how SDOH influence symptom management remains understudied and should be addressed in future research. Our findings that younger and female candidates more commonly experienced worse symptom burden is consistent with previous reports in other chronically ill populations.20,24,25 Aging may blunt symptom perception and reduce the risk of higher symptom burden perception in the older adult population.26 Gender disparities may be explained by differences in underlying pathophysiology that give rise to symptoms,27 gender differences in willingness to report symptoms,26 or differences in support available to manage symptoms. Younger and female candidates also may have different social roles, such as caregivers to children or family members, that may be physically and mentally burdensome and may contribute to greater symptom burden (e.g., fatigue, shortness of breath, pain, anxiety).21 Compared to the mild profile, the severe symptom profile had a significantly higher SIPAT score. This psychosocial risk score measures four important domains including, patient readiness, knowledge, and understanding of illness management, social support, psychological stability, and substance use; each individually has been linked to poorer symptom management.28–30

When asked about social support, transplant candidates with the severe symptom profile and those with a moderate symptom burden more often reported “satisfactory” or “poor” support quality compared to the mild profile. These same candidates also less often reported being married/in a relationship or having a spouse/significant other as their primary support person compared to the mild profile. Our findings suggest that patients with poorer social support may be at risk for worse symptom burden. These findings are consistent with the literature, which has demonstrated a relationship between the quality of a patient’s support person and improved symptom management.26,28

We acknowledge that our study has several limitations. This was a single center study, which could limit the generalizability of our findings. Although the characteristics of our sample are comparable to the national US lung transplant waitlist, patients with pulmonary hypertension and cystic fibrosis were underrepresented in our sample. Second, 14% of the patients were excluded because they were “too sick.” Most of these patients were mechanically ventilated, required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and/or were medically sedated. Results cannot be generalized to these patients. Our sample was relatively small, which limited our ability to adjust for multiple comparisons and may have limited our ability to identify significant differences in SDOH across groups. Additionally, we identified 3 profiles; however, a larger sample size is needed to determine whether more than three symptom-illness severity profiles exist. We had limited access to SDOH data including social and environmental exposures, economic stability, and health literacy, More granular SDOH data is needed to better understand the relationship between SDOH and symptom experiences. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to integrate subjective symptom data with objective clinical data to define profiles that provide important preliminary evidence of heterogenous symptom burden that is not explained by severity of illness in lung transplantation, but rather, by SDOH.

Our findings have implications for clinicians and researchers interested in improving quality of life outcomes for transplant patients. Our findings suggest that in addition to traditional objective measures of illness, symptom assessments and SDOH screenings need to be incorporated into routine pre- and post-transplant practice. In combination, these data could inform patient and provider decision-making, lead to more personalized care, and be used to define transplant benefit more comprehensively.

Our findings also highlight that SDOH may play an important role in explaining variability in symptom experience. Therefore, assessing SDOH in clinical practice may help identify patients at greatest risk for experiencing high symptom burden. Health care systems are beginning to embed SDOH into the electronic health record problem list.31 Providing care teams with SDOH data at the point of care can contribute to a better understanding of the context in which patients are managing their symptoms and what resources are available to assist them. This understanding could help inform how we treat and educate patients in clinical practice and help guide more personalized care. If SDOH contribute to symptoms, interventions that target SDOH are needed.

Future research is needed to determine whether these distinct profiles are associated with differences in clinical outcomes such as hospital length of stay, hospital readmission rates, and mortality. Finally, understanding how symptoms change over the transplantation trajectory and for whom is also needed to better define transplant benefit and inform shared decision-making.

The 2022 NASEM report has identified addressing inequities in the US organ transplantation system and improving the patient experience of needing and waiting for an organ transplantation as high priorities. Our findings contribute to these important but often understudied areas in lung transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Clustering data on symptom and illness severity, three distinct profiles were identified

Symptom burden among lung transplantation candidates is highly heterogenous

Measures of illness severity may not identify patients who are at greatest risk of experiencing a higher symptom burden; rather, heterogeneity in symptom burden may be linked to social determinants of health

Funding Sources:

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award training program in Individualized Care for At Risk Older Adults (T32NR009356, 2018-2020), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Award (2018-2020), the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Nursing, Health Sciences, and Allied Health Research Grant, and Sigma Theta Tau Chapter Research grant (2019).

Abbreviations

- MSAS

Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

- LAS

lung allocation score

- EMR

electronic medical record

- SIPAT

Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

All authors have no financial disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Valapour M, Lehr CJ, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2019 Annual Data Report: Lung. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2021;21 Suppl 2:441–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Realizing the Promise of Equity in the Organ Transplantation System. . The National Academies Press. Published 2022. Accessed2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer JP, Chen J, Blanc PD, Leard LE, Kukreja J, Chen H. A thematic analysis of quality of life in lung transplant: the existing evidence and implications for future directions. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(4):839–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CS, Gelow JM, Denfeld QE, et al. Physical and psychological symptom profiling and event-free survival in adults with moderate to advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(4):315–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee CS, Hiatt SO, Denfeld QE, Mudd JO, Chien C, Gelow JM. Symptom-Hemodynamic Mismatch and Heart Failure Event Risk. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;30(5):394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melhem O, Savage E, Al Hmaimat N, Lehane E, Fattah HA. Symptom burden and functional performance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;62:151510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatigati A, Alrawashdeh M, Zaldonis J, Dabbs AD. Patterns and Predictors of Sleep Quality Within the First Year After Lung Transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2016;26(1):62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanuza DM, Lefaiver CA, Brown R, et al. A longitudinal study of patients’ symptoms before and during the first year after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26(6):E576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen VL, Holm AM, Cooper B, Paul SM, Miaskowski C, Rustoen T. Differences in Symptom Burden Among Patients With Moderate, Severe, or Very Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(5):849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health. Accessed December 21, 2022.

- 12.Maldonado JR, Dubois HC, David EE, et al. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT): a new tool for the psychosocial evaluation of pre-transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 1994;30a(9):1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckerblad J, Todt K, Jakobsson P, et al. Symptom burden in stable COPD patients with moderate or severe airflow limitation. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2014;43(4):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jablonski A, Gift A, Cook KE. Symptom assessment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Western journal of nursing research. 2007;29(7):845–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Network for Organ Sharing. Questions and anwsers for transplant professionals about lung allocation

- 17.Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth Mixture Modeling: A Method for Identifying Differences in Longitudinal Change Among Unobserved Groups. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;33(6):565–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmiege SJ, Meek P, Bryan AD, Petersen H. Latent variable mixture modeling: a flexible statistical approach for identifying and classifying heterogeneity. Nursing research. 2012;61(3):204–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melhem O, Savage E, Lehane E. Symptom burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;57:151389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen VL, Rustøen T, Cooper BA, et al. Distinct symptom experiences in subgroups of patients with COPD. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2016;11:1801–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grayson SC, Patzak SA, Dziewulski G, et al. Moving beyond Table 1: A critical review of the literature addressing social determinants of health in chronic condition symptom cluster research. Nurs Inq. 2022:e12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pleasants RA, Riley IL, Mannino DM. Defining and targeting health disparities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2016;11:2475–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadipelli VR, Elwing JM, Oglesby WH, El-Kersh K. Social determinants of health in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients in the United States: Clinician perspective and health policy implications. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(3):e12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gift AG, Shepard CE. Fatigue and other symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: do women and men differ? J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(2):201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faulkner KM, Jurgens CY, Denfeld QE, Lyons KS, Harman Thompson J, Lee CS. Identifying unique profiles of perceived dyspnea burden in heart failure. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2020;49(5):488–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Lee CS, Strömberg A. Integrating Symptoms Into the Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2019;42(3):206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CS, Hiatt SO, Denfeld QE, Chien CV, Mudd JO, Gelow JM. Gender-Specific Physical Symptom Biology in Heart Failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;30(6):517–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iovino P, Lyons KS, De Maria M, et al. Patient and caregiver contributions to self-care in multiple chronic conditions: A multilevel modelling analysis. International journal of nursing studies. 2021;116:103574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaarsma T, Cameron J, Riegel B, Stromberg A. Factors Related to Self-Care in Heart Failure Patients According to the Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness: a Literature Update. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017;14(2):71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholas PK, Willard S, Thompson C, et al. Engagement with Care, Substance Use, and Adherence to Therapy in HIV/AIDS. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014:675739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen M, Tan X, Padman R. Social determinants of health in electronic health records and their impact on analysis and risk prediction: A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1764–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.