Abstract

Background

The French health authorities are considering expanding the current selective hepatitis E virus (HEV)-RNA testing procedure to include all donations in order to further reduce transfusion-transmitted HEV infection. Data obtained from blood donors (BDs) tested for HEV-RNA between 2015 and 2021 were used to assess the most efficient nucleic acid testing (NAT) strategy.

Materials and methods

Viral loads (VLs) and the plasma volume of blood components, as well as an HEV-RNA dose of 3.85 log IU as the infectious threshold and an assay with a 95% limit of detection (LOD) at 17 IU/mL, were used to assess the proportion of: (i) HEV-RNA-positive BDs that would remain undetected; and (ii) blood components associated with these undetected BDs with an HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU, considering 4 NAT options (Individual testing [ID], MP-6, MP-12, and MP-24).

Results

Of the 510,118 BDs collected during the study period, 510 (0.10%) were HEV-RNA-positive. Based on measurable VLs available in 388 cases, 1%, 15.2%, 21.8%, and 32.6% of BDs would theoretically pass undetected due to a VL below the LOD of ID, MP-6, MP-12, and MP-24 testing, respectively. All BDs associated with a potentially infectious blood component would be detected with ID-NAT while 13% of them would be undetected with MP-6, 19.6% with MP-12, and 30.4% with MP-24 depending on the plasma volume. No red blood cell (RBC) components with an HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU would enter the blood supply, regardless of the NAT strategy used.

Discussion

A highly sensitive ID-NAT would ensure maximum safety. However, an MP-based strategy can be considered given that: (i) the risk of transmission is closely related to the plasma volume of blood components; (ii) RBC are the most commonly transfused components and have a low plasma content; and (iii) HEV-RNA doses transmitting infection exceed 4 log IU. To minimise the potential risk associated with apheresis platelet components and fresh frozen plasma, less than 12 donations should be pooled using an NAT assay with a LOD of approximately 20 IU/mL.

Keywords: hepatitis E virus, blood donations, nucleic acid testing, pooling, transfusion-transmitted infection

INTRODUCTION

In high-income countries, hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is mainly acquired through the consumption of contaminated raw or undercooked meat, pork liver sausage or contaminated water1. Of the 8 genotypes (genotypes 1–8) described to date, genotype 3 (HEV-3), originating from animal reservoirs and, to a lesser extent, genotype 4 (HEV-4), are responsible for most infections occurring in Western Europe2. In developed countries, the large majority of HEV infections cause self-limiting asymptomatic acute hepatitis. However, extrahepatic manifestations such as neurological and renal disease or severe forms have been described as fulminant hepatitis in patients suffering from pre-existing chronic liver disease, and chronic hepatitis observed in approximately 60% of immunocompromised organ-transplant recipients3–6. Furthermore, HEV-4 seems to generate more severe outcomes than HEV-3 in infected patients7–9.

HEV infection emerged as a new threat to blood safety in the early 2000s with the first case of transmission by transfusion being observed in Japan in 200210. Since then, several transfusion-transmitted (TT) infections have been reported worldwide11 involving all types of blood components including solvent detergent (SD)-treated plasma and components inactivated with Amotosalen12,13. In France, following the first TT-HEV infection in 200614, additional cases affecting all blood components, including those submitted to pathogen reduction, have been reported to the haemovigilance network12.

The risk of TT-HEV infection has been related to the infectious dose (amount of virus present in the infected blood product), which depends on the volume of plasma transfused. The minimum infectious dose (MID) causing TT-HEV was reported with a platelet concentrate containing 3.85 log IU, although transmission is more likely when the dose exceeds 4 log IU11,15,16.

Due to an increasing number of TT-HEV cases and the severity of the disease in immunocompromised patients, several countries have decided to implement HEV-RNA screening of blood donations (BD) to mitigate the risk of transmission through blood components. However, in the absence of mandatory regulatory requirements, decisions in each country have been guided by logistic, economic and ethical issues17,18. Due to the occurrence of multiple TT-HEV cases, the first country which implemented HEV molecular testing was Japan (in Hokkaido) in 2015, firstly as an experimental measure then progressively applied to all donations19. HEV-RNA screening was also introduced in some European countries from 2012 onwards. A few of them adopted universal screening while others opted for a selective screening procedure targeted towards recipients at risk or limited to certain regions of the country17,18. In France, nucleic acid testing (NAT) for HEV was initially introduced in December 2012 in pools of 96 apheresis plasma donations for plasma intended for SD-plasma production. From the end of 2014 onwards, HEV-RNA screening was continued in mini-pools (MP) of 6 donations in order to display approximately 30% of HEV-free plasma components targeted towards immunocompromised patients and recipients with pre-existing chronic liver disease. The residual risk of viral transmission with cellular blood components and the availability of new screening devices are prompting French health authorities to consider expanding testing to all donations. To help identify the most efficient testing strategy, we first assessed the analytical sensitivity of two NAT screening methods and then used data obtained over a 7-year period of HEV-RNA blood-donation testing to compare different NAT options for risk mitigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hepatitis E virus screening of blood donations

Approximately 30% of plasma derived from apheresis or whole blood was tested for HEV-RNA in mini-pools of 6 donations (MP-6). From January 2015 to December 2017, HEV-NAT was performed with the Real Star HEV RT-PCR kit 1.0 (Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany) and since January 2018 with the Procleix HEV-RNA assay on the Panther automated platform (Grifols, Barcelona, Spain). A 95% limit of detection (LOD) has been estimated for both methods using the World Health Organization (WHO) HEV standard (HEV genotype 3a) at 23 IU/mL and 24 IU/mL (95% CI: 19–33), respectively20. Reactive MPs were deconstructed to identify the positive donation. If a reactive result was obtained in individual (ID) testing, the donation was deemed positive for HEV-RNA and underwent further investigation including: (i) viral load (VL) with in-house RT-PCR until 201821, then with a RealStar® HEV-RT-PCR Kit 2.0 (Altona, limit of quantification [LOQ] estimatedat 30 IU/mL);(ii) sequencing in the ORF2 region with a previously described method to determine the genotype22; and (iii) screening for the presence of HEV-specific IgM and IgG antibodies using the anti-HEV Elisa technique (IgM and IgG WANTAI HEV, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

A total of 510,118 donations collected from week 47 in 2014 to week 35 in 2021 were tested for HEV-RNA in MP-6 NAT with an estimated MP LOD of approximately 140 IU/mL.

Limit of detection of HEV-NAT screening devices

Two CE-marked diagnostic devices intended to detect HEV-RNA in blood donations have been reviewed to assess their 50% and 95% LODs in two EFS laboratories: 1) Cobas® HEV Testing on the Cobas® 8800 System (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) reported a 50% LOD at 3.9 IU/mL (3.4–4.3) and 95% LOD at 18.6 IU/mL (15.9–22.6); and 2) Procleix HEV with the Panther system (Grifols) reported a 50% LOD 2.02 IU/mL (1.71–2.32) and 95% LOD 7.89 IU/mL (6.63–9.83). Twenty-four replicates of 10 sequential dilutions ranging from 0 to 40 IU/mL of the genotype 3a 6,329/10 standard23 were tested with each assay, and 50% and 95% LODs were calculated by Probit analysis.

Evaluation of different HEV-RNA testing strategies

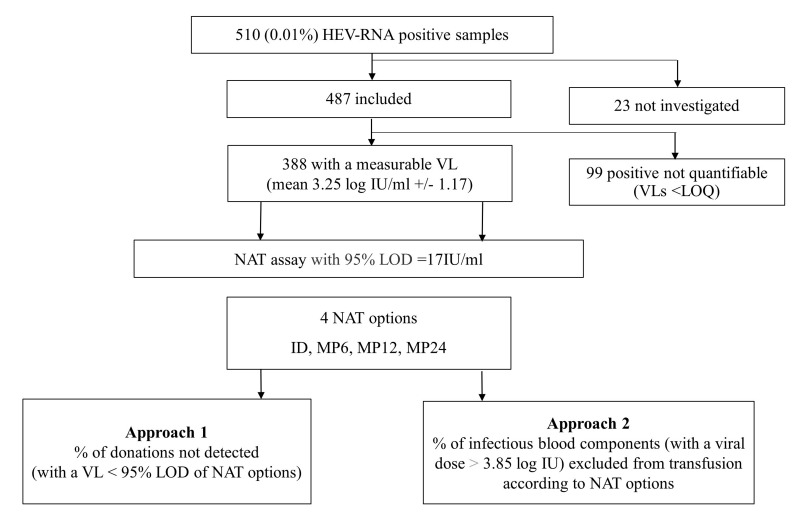

Viral loads of HEV-NAT-positive donations included in the study period and plasma volume of blood components, as well as an HEV-RNA dose of 3.85 log IU as the infectious threshold and a NAT assay with a 95% LOD estimated in the study focusing on the two HEV-NAT screening devices, were used to assess: (i) the proportion of HEV-RNA-positive BDs which would remain undetected; and (ii) the proportion of blood components associated with these undetected BDs, with a viral dose >3.85 log IU considering 4 NAT options (Individual testing [ID], MP-6, MP-12, MP-24). The 95% LOD of the NAT assay used in the model was the mean of the 95% LODs obtained for Cobas and Procleix assays, respectively (i.e., 17 IU/mL; see Results section) leading to 4 anticipated 95% LODs according to the 4 NAT options: 17 IU/mL (1.23 log U/mL) for ID, 102 IU/mL (17×6, 2.01 log IU/mL) for MP-6, 204 IU/mL (17×12, 2.31 log IU/mL) for MP-12, and 408 IU/mL (17×24, 2.61 log IU/mL) for MP-24 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study design

The number of donations with a VL below each of these LODs was used to calculate the percentage of HEV-RNA-positive donations which theoretically would pass undetected with the various NAT testing options.

To estimate the proportion of potential HEV infectious blood components excluded from transfusion according to the NAT testing strategy, we calculated the total HEV-RNA dose (in IU) contained in each blood component, assuming that each blood donation would have generated one of these components. This was obtained by multiplying the donation VL by the mean plasma volume contained in each component which was retrieved from our quality control process (details not shown): 12.5 mL (100/8) for whole blood-derived pooled platelet concentrates (WBPCs) in pools of 8 donations, 15 mL for red blood cells (RBC), 24 mL (120/5) for WBPCs in pools of 5 donations, 130 mL for apheresis platelet concentrates (APC), and 200 mL for fresh frozen plasma units (FFPs). Then, considering a dose of 7,056 IU (3.85 log IU) as the infectious threshold, we calculated the number (A) of theoretically HEV infectious blood components (those with a total HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU) for each category of blood components. Finally, for each of the 4 NAT testing options, we determined the number (B) of components in each category with an HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU for the VL donation that would have been detected according to the 95% LOD achieved with NAT testing. The percentage of HEV infectious blood components excluded from transfusion was obtained by dividing B by A.

RESULTS

Characteristics of HEV-NAT-positive blood donations

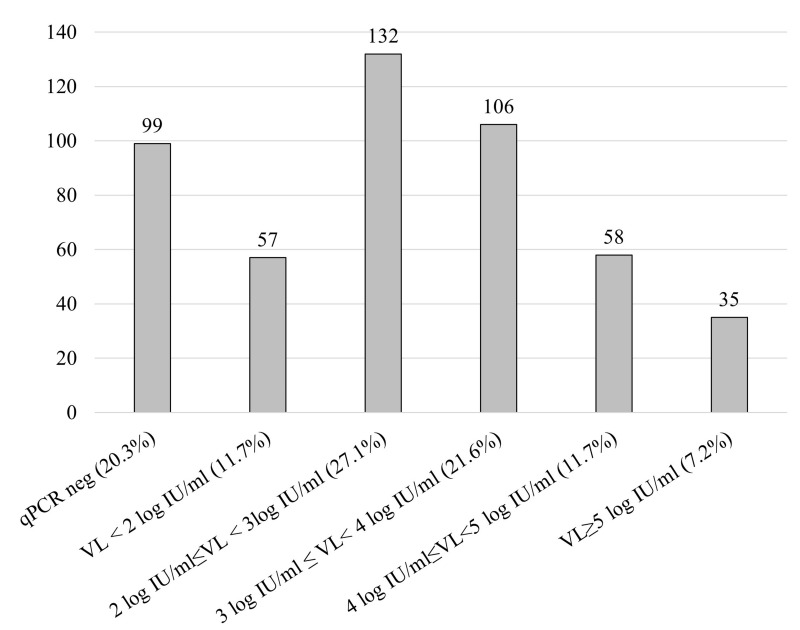

Among the 510,118 donations collected during the study period and tested for HEV-RNA in MP-6, 510 (0.10%) were positive. HEV-RNA prevalence was stable over time (data not shown). Of the 510 HEV-RNA-positive donations, 487 (95.5%) were included in the study while the remaining 23 were unavailable for analysis (Figure 1). There were more males (n=443) than females (n=44); males had a significantly higher mean age (47.4±13.7 years [19–70] vs 36.2±16.7 [19–65], p<0.0001). The VLs were distributed as follows: 99 (20.3%) negative with quantitative PCR, 57 (11.7%) <2 log IU/mL, 132 (27.1%) between 2 and 3 log IU/mL, 106 (21.7%) between 3 and 4 log IU/mL, 58 (11.9%) between 4 and 5 log IU/mL, and 35 (7.2%) >5 log IU/mL (Figure 2). The mean VL of the 388 samples with a measurable HEV-RNA level was 3.25±1.17 log IU/mL (median 3.05 log IU/mL, [0.3–7.23]). The genotype obtained for 284 samples (73.5%) was HEV-3 for 99.6% of sequenced strains (48.6% gt3c, 33.5% gt3f and 17.6% gt3 other). Only one (0.4%) was HEV-4. No anti-HEV antibodies were detected in 61.5% of the 483 tested donors while 27.1% were IgM+/IgG+, 5.8% IgM−/IgG+ and 5.6% IgM+/IgG−. The presence of IgG (whether associated or not to IgM) was significantly higher (p=0.02) in samples with low VLs, and IgM alone could be detected more frequently in the highest VLs (p<0.0001) (Table I).

Figure 2.

Distribution of viral loads (expressed as log IU/mL) in 487 HEV-NAT-positive blood donations tested in MP-6

Table I.

Serology results in 483 HEV-NAT-positive samples based on the viral load (VL)

| Not quantifiable VL | VL (log IU/mL) <2 | 2 ≤ VL (log IU/mL) <3 | 3 ≤ VL (log IU/mL) <4 | 4 ≤ VL (log IU/mL) <5 | VL (log IU/mL) ≥5 | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG−/IgM− | 58 | 59.8% | 37 | 64.9% | 77 | 58.3% | 68 | 64.8% | 39 | 68.4% | 18 | 51.4% | 297 | 61.5% |

| IgG−/IgM+ | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 1.8% | 2 | 1.5% | 6 | 5.7% | 7 | 12.3% | 10 | 28.6% | 27 | 5.6% |

| IgG+/IgM+ | 33 | 34.0% | 17 | 29.8% | 45 | 34.1% | 25 | 23.8% | 8 | 14.0% | 3 | 8.6% | 131 | 27.1% |

| IgG+/IgM− | 5 | 5.2% | 2 | 3.5% | 8 | 6.1% | 6 | 5.7% | 3 | 5.3% | 4 | 11.4% | 28 | 5.8% |

| Total | 97 | 57 | 132 | 105 | 57 | 35 | 483 | |||||||

Limit of detection of NAT screening devices

The 50% and 95% LOD established by Probit analysis from the results obtained in 24 replicates of the HEV gt3a 6329/10 standard were 3.33 IU/mL (2.66–4.11) and 16.33 IU/mL (11.67–27.06) for Cobas HEV 8800, and 4.10 IU/mL (3.33–5.01) and 18.08 IU/mL (13.13–29.03) for Procleix HEV Panther (Table II). These findings are consistent with the specifications provided for the Cobas assay while Procleix assay LODs were 2-fold higher than those provided by the manufacturer.

Table II.

Limit of detection of the 2 HEV-NAT assays studied using the WHO 6329/10 genotype 3a standard

| Cobas HEV8800, Roche | Procleix HEV Panther, Grifols | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD provided by the manufacturer | 50% LOD: 3.9 IU/mL [3.4–4.3] 95% LOD: 18.6 IU/mL [15.9–22.6] |

50% LOD: 2.02 IU/mL [1.71–2.32] 95% LOD: 7.89 IU/mL [6.63–9.83] |

||

| HEV-RNA IU/mL | N. pos/N. tested | % positive | N. pos/N. tested | % positive |

| 0 | 0/22 | 0% | 0/24 | 0% |

| 0.93 | 3/24 | 12.5% | 1/24 | 4.17% |

| 1.50 | 5/24 | 20.8% | 6/24 | 25.0% |

| 2.40 | 12/24 | 50.0% | 7/24 | 29.2% |

| 3.80 | 8/24 | 33.3% | 7/24 | 29.2% |

| 6.10 | 16/24 | 66.6% | 15/24 | 62.5% |

| 9.8 | 22/24 | 9.6% | 20/24 | 83.3% |

| 15.6 | 23/24 | 95.8% | 23/24 | 95.8% |

| 25 | 24/24 | 100% | 24/24 | 100% |

| 40 | 24/24 | 100% | 24/24 | 100% |

| 50% LOD [95%CI] | 3.33 IU/mL [2.66–4.11] | 4.10 IU/mL [3.33–5.01] | ||

| 95% LOD [95%CI] | 16.33 IU/mL [11.67–27.06] | 18.08 IU/mL [13.13–29.03] | ||

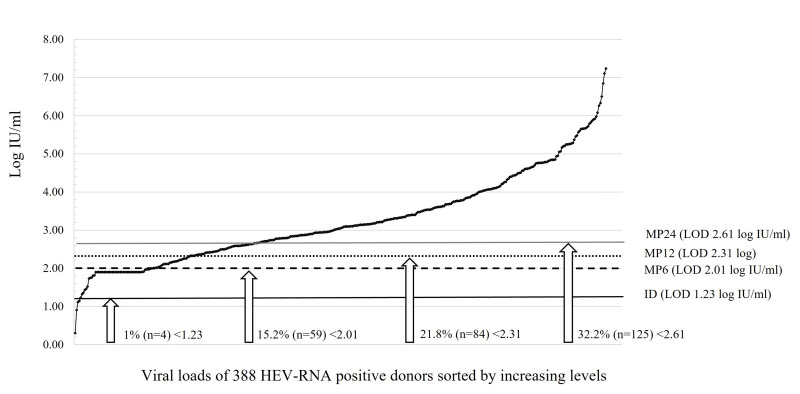

Proportion of HEV-RNA-positive donations which would remain undetected according to the NAT testing strategy

Figure 3 shows the VL distribution of the 388 HEV-RNA-positive donations with a measurable HEV-RNA level, including the percentage that would theoretically be missed with a 95% probability due to a VL below the 95% LOD of the 4 NAT screening options under consideration. Among these 388 donations, 4 (1%) would remain undetected with ID-NAT (VLs <1.15 log IU/mL), 59 (15.2%) with MP-6 (VLs <2.00 log IU/mL), 84 (21.8%) with MP-12 (VLs <2.29 log IU/mL), and 125 (32.2%) with MP-24 (VLs <2.60 log). Considering the VLs of these donations and blood component plasma volumes, the 3.85 log IU infectious threshold was never exceeded in blood components prepared from donations undetected with ID, whereas this threshold was exceeded for 49 FFPs and 48 APCs associated with the 59 donations undetected with MP-6, for 74 FFPs and 73 APCs linked to the 84 donations undetected with MP-12, and 115 FFPs, 114 APCs and 20 WPBCsx5 with the 125 donations undetected with MP-24.

Figure 3.

Number (%) of HEV-RNA-positive samples remaining undetected according to NAT options among the 388 HEV-NAT-positive blood donations with measurable viral loads (log IU/mL)

The curve reports the distribution of VLs. Horizontal lines represent the anticipated 95% LOD depending on the pooling strategy using an assay with a 95% limit of detection (LOD) at 17 IU/mL.

Proportion of HEV infectious blood components excluded from transfusion as per the NAT testing strategy

The percentage of potential infectious blood components (with HEV-RNA >3.85 log IU) assumed to be prepared from the 388 HEV-RNA-positive blood donations which would be discarded according to the HEV-NAT screening strategy is presented in Table III. The use of a NAT assay with a 95% LOD at 17 IU/mL on individual format would be able to detect all blood donations associated with any blood component showing an HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU. The same assay used on pools would fail to detect 12.7% and 13% of blood donations associated with APCs and FFPs if performed in MP-6, 19.6% and 19.4% of blood donations associated with APCs and FFPs in MP-12, and 30.4%, 30.2%, and 7.1% of blood donations associated with APCs, FFPs and WBPCsx5 in MP-24, respectively. Notably, the lowest VLs associated with a component with HEV-RNA >3.85 log IU were 54, 95, 246, 478, and 585 IU/mL for FFP, APC, WBPCx5, RBCs and WBPCx8, respectively.

Table III.

Discarded infectious blood components according to the HEV-NAT screening strategy based on viral loads obtained in 388 HEV-RNA-positive blood donations collected from 2014 to 2021

| Blood component | Plasma volume (mL) | N. (%) of components with an HEV-RNA >3.85 log IU | % of positive HEV antibodies | % of potential infectious blood components (with an HEV-RNA >3.85 log IU) detected with HEV-NAT according to sensitivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single testing 95% LOD: 17 IU/mL | MP-6 95% LOD: 102 IU/mL | MP-12 95% LOD: 204 IU/mL | MP-24 95% LOD: 408 IU/mL | ||||

| FFP | 200 | 378 (97.4%) | 38% | 378/378 (100%) | 329/378 (87%) | 304/378 (80.4%) | 263/378 (69.6%) |

| APC | 130 | 377 (97.2%) | 37.9% | 377/377 (100%) | 329/377 (87.3%) | 304/377 (80.6%) | 263/377 (69.8%) |

| WBPC×5 | 24 | 283 (72.9%) | 40.6% | 283/283 (100%) | 283/283 (100%) | 283/283 (100%) | 263/283 (92.9%) |

| RBC | 15 | 253 (62.5%) | 37.8% | 253/253 (100%) | 253/253 (100%) | 253/253 (100%) | 253/253 (100%) |

| WBPC×8 | 12.5 | 242 (62.4%) | 37.5% | 242/242 (100%) | 242/242 (100%) | 242/242 (100%) | 242/242 (100%) |

RBC: red blood cells; APC: apheresis platelet concentrates; WBPC: whole blood-derived pooled platelet concentrates; FFP: fresh frozen plasma.

DISCUSSION

The HEV-RNA incidence found in this study (0.10%) is one of the highest observed among blood donors in Europe. Notably, this incidence is relatively steady over time but higher than that observed in plasma samples tested in MP-96 (0.04%) in the period 2012 to 201415,17. A recent review reported a 0.032% overall rate (0.01–0.19%) across 8 European facilities performing HEV-RNA testing17. More recently, two studies based on the same assay for HEV-RNA screening reported incidence rates of 0.19% in 16,236 blood donors tested individually in Germany24 and 0.02% in 655,523 blood donors tested in MP-16 in Catalonia, Spain25. Assuming a similar HEV epidemiology in both countries, the 10-fold lower rate observed in the latter study is probably related to the pooling strategy and suggests that a substantially high proportion of HEV-RNA-positive samples had low VLs. In line with this hypothesis, our data highlighted VLs that were not measurable in 20.3% of HEV-NAT-positive screening donations. This suggests that a certain proportion of HEV-RNA-positive donations with low HEV-RNA levels may have escaped detection. Therefore, the highest incidence would presumably have been observed with an individual NAT screening procedure. Furthermore, blood donors tested in our study were mainly apheresis plasma donors due to the selective testing adopted in our country and so were not representative of the entire blood donor population. Our data, therefore, need to be adjusted according to donor characteristics in order to extrapolate them to the entire population and compare them to other countries. This adjustment will also prove useful in updating the HEV transfusion risk, estimated at 1 in 3,800 donations (from 1 in 2,700 to 1 in 6,200) in 201326. Interestingly, and in agreement with data collected in Spain showing 42% of HEV-RNA-positive with antibodies25, 38.5% of viraemic blood donors in our study had anti-HEV antibodies (70% IgM+/IgG+, 15% IgM+/IgG− and 15% IgM−/IgG+) suggesting that HEV-RNA-positive donations were collected during the entire viremia phase. The presence of IgG mostly observed in blood donors with low VLs supports the hypothesis that these donations were collected at the end of the viraemic period, and that donors were, therefore, in the convalescent phase of infection. The presence of antibodies in the plasma of some donors raises the question as to whether they have a lower level of plasma infectivity, as suggested by Hewitt et al.27 who showed that HEV antibodies were detected in 22% of donations associated with virus transmission vs 52% of donations not associated with transmission. However, although antibodies may neutralise enterally non-enveloped HEV particles, "partially" lipid-enveloped HEV particles circulating in the blood may be protected against ORF-2 antibodies28,29. The absence of antibody-neutralising activity in the blood should, however, be investigated in the light of a recent study showing that blood could also contain non-enveloped particles30. Notably, seropositive blood donations associated with an HEV-RNA dose >3.85 log IU amounted to approximately 40% (see Table III). This is higher than the figure observed in a recent study reporting 21% (4/19) seropositive at-risk blood donations in Germany24. Although controversial, the neutralising antibody effect cannot be entirely ruled out and we can assume that the presence of antibodies in blood donations with relevant VLs may slightly reduce the risk of blood-transmitted HEV infection.

The risk of TT-HEV infection is closely related to the infectious HEV-RNA dose present in the transfused blood component, which depends on the donation VL and the plasma volume of the component. Consequently, RBCs are less likely to transmit the virus than FFP11,24,27. The selective screening strategy implemented in our country up to now has been based on mitigating the risk associated with the transfusion of plasma products to specific high-risk patients (such as organ-transplanted subjects or individuals with chronic liver disease) given the high HEV-RNA dose contained in this product, if infected. This partial plasma strategy has probably reduced the risk of plasma-associated HEV transmission; the last case of plasma-related TT-HEV was reported in 201312. However, logistic and organisational issues, as well as the dilemma posed by potential HEV transmission via other untested blood components, raise the question of how useful it would be to introduce universal screening, as already witnessed in several European countries following the implementation of nation-wide or regional universal HEV-RNA testing programmes.

We initially assessed the sensitivity of two potentially suitable assays for large-scale screening in order to help decide on the most appropriate HEV-RNA screening strategy. The Cobas HEV assay on the 8800 platform and the Procleix HEV assay using the Panther system exhibited similar sensitivity levels of around 4 and 17 IU/ mL with LODs of 50% and 95%, respectively. As indicated by Cordes et al.24, ID-NAT remains the best option to avoid any TT risk. Based on data reported in this last study, 18/31 ID-NAT positive donations had an HEV-RNA VL below 140 IU/mL corresponding to the 95% LOD of the MP-6 NAT strategy. Therefore, a MP-6 NAT would miss 58% of viraemic donations. As we considered the 95% LOD, this proportion is probably overestimated and represents the worst-case scenario. In addition, being based on a low number of samples (n=31), this estimate should be interpreted with caution. Similarly, a simulation study carried-out in Germany showed that NAT screening based on an assay with a 95% LOD of 20 IU/mL used in MP-24 would reduce anticipated TT-HEV infection by 90.7% and anticipated TT chronic HEV infections by 92%31. Nonetheless, HEV-positive donations with low viraemia levels do not necessarily lead to recipient contamination, which is closely related to the volume of plasma transfused. This was supported by Bes et al. who showed that no cases of TT-HEV infection have been reported since the implementation of HEV-RNA universal screening in MP-16 in Catalonia, Spain25. Moreover, some cases of TT-HEV infections remain asymptomatic or resolve spontaneously, at least in immunocompetent patients. Therefore, a pooling screening strategy could be a valuable option that reconciles risk mitigation and organisational, financial and logistical constraints that should be assessed before introducing such a measure. Parameters that need to be considered in order to make a final decision are: (i) risk-benefit analysis for which our data could be useful; (ii) the cost of each scenario; and (iii) the impact on organising the laboratory in terms of human and technological resources. Thus, the first approach in our study was to assess the capacity of 4 NAT screening options (ID, MP-6, MP-12 and MP-24 based on an assay with 95% LOD at 17 IU/mL) to detect a large panel of samples comprising donations with quantified VLs from French blood donors who had tested positive for HEV-RNA in MP-6, assuming that the VL distribution was representative of what can be expected across the entire blood donor population. The simulation shows that 1% (ID-NAT) to 32.6% (MP-24) of HEV-infected blood donations would have gone undetected. This approach predicted 15.2% of undetected donations with MP-6, which contradicts our routine blood-screening results since these donations tested RNA-positive. This can probably be explained by the fact that VLs close to the LOD of the MP-6 NAT were detected by chance with a probability <95%.

The second approach was to assess the proportion of blood components that would be discarded depending on the NAT screening strategy used by taking into account their HEV-RNA dose, assuming that each positive donation may generate all types of blood components. We found that all potential infectious components with an overall quantity of HEV-RNA >3.85 log IU would be discarded using an ID-NAT strategy with a 95% LOD at 17 IU/mL. FFPs and APCs are the components with the highest plasma volume and are, therefore, most likely to pass undetected despite at-risk characteristics. Nevertheless, these data must be considered in the light of transfusion practices. Indeed, RBCs are the most widely transfused components, accounting for more than 85% of transfusions. According to our simulations, all NAT options would guarantee the blood safety of RBCs, although the greatest impact is on APCs and FFPs components since approximately 13% of them would not be rejected with MP-6 while MP-12 and MP-24 would disregard 20% and 30%, respectively.

Our study has some limitations. The first is related to the panel of samples used for estimates. As they tested HEV-RNA-reactive with the current NAT pooling strategy (estimated 95% LOD of 140 IU/mL), we cannot rule out the possibility that some infected donations with extremely low VLs will have gone undetected and these are, therefore, not included in our estimates. Nevertheless, we have noted that 34% of reactive BDs had a VL <140 IU/mL, which suggests that the distribution of VLs is probably close to that anticipated in all infected blood donors. Consequently, the proportion of undetected infectious components was likely to be overestimated but cannot be accurately established. The second limitation concerns the possible underestimation of the HEV-RNA dose due to the occurrence of blood components with much higher plasma volumes than those previously encountered and to an underestimation of the minimal infectious dose. The infectious threshold was considered to be 7,056 IU, although a recent Japanese paper described virus transmission by a plasma unit produced from an HEV-RNA-negative donation tested in MP-6, which was also found to contain an extremely low viral dose estimated by logistic regression analysis at 324 IU, hence posing the issue of an underestimated risk19. This extremely rare situation, picked up by chance by NAT, has never been observed by our haemovigilance surveillance system to date, neither has it been reported in other published cases in which the most frequent minimal infectious dose was found to be around 4 log IU11,15,16. In line with this, data from 36 recipients infected with blood components between 2006 and 2021 in France (data not shown) show that the viral doses transmitting HEV infection averaged 5.98±1.15 log IU with an MID of 4.36 log IU contained in RBC. However, if such a low infectious dose, as estimated by Sakata et al.19, were to be reported by the haemovigilance network, we would perform a further risk analysis and take this parameter into account.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of data from the current HEV-NAT partial screening of blood donations in France allows us to highlight the characteristics of HEV infection in this population and to reconsider the NAT strategy. We have shown that viral loads were mostly low, thereby requiring an extremely sensitive method in order to detect all HEV-RNA-positive blood donations. However, as the risk of transmission is closely related to the plasma volume of blood components, and as RBCs, the most commonly transfused components, have a low plasma content, and because, in our experience, HEV-RNA doses transmitting infection exceeded 4 log IU, an MP-based strategy can be considered. On the basis of our findings, in order to minimise the potential risk associated with APCs and FFPs, we do not recommend a NAT method with a 95% LOD at 400 IU/mL (MP-24) in a risk-benefit analysis. However, NAT strategies based on an assay with a LOD of approximately 20 IU/mL and a pooling method collecting less than 12 donations should be considered and should be further revised in the light of cases reported in the haemovigilance system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Elodie Pouchol and Stephane Begue from the EFS Saint Denis for providing data collected via the French haemovigilance system and the national quality control process, and to all staff involved in testing for their contribution.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

SLa and PG designed the study. CM, SLe and PG supervised HEV-RNA testing in blood donations and collected data from HEV RNA positive donations. CM, CR, SLe and ID, supervised NAT assay evaluation. SLh, FA and JI supervised molecular and serological investigations. SLa, PG, PM, PR and PT analysed the data. Sla and PG drafted the manuscript. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mansuy JM, Abravanel F, Miedouge M, Mengelle C, Merviel C, Dubois M, et al. Acute hepatitis E in south-west France over a 5-year period. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslan AT, Balaban HY. Hepatitis E virus: epidemiology, diagnosis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5543–5560. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i37.5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lhomme S, Marion O, Abravanel F, Izopet J, Kamar N. Clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and treatment of hepatitis E virus infections. J Clin Med. 2020;9:331. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izopet J, Lhomme S, Chapuy-Regaud S, Mansuy JM, Kamar N, Abravanel F. HEV and transfusion-recipient risk. Transfus Clin Biol. 2017;24:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colson P, Decoster C. Recent data on hepatitis E. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019;32:475–481. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lhomme S, Marion O, Abravanel F, Chapuy-Regaud S, Kamar N, Izopet J. Hepatitis E pathogenesis. Viruses. 2016;8:212. doi: 10.3390/v8080212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanayama A, Arima Y, Yamagishi T, Kinoshita H, Sunagawa T, Yahata Y, et al. Epidemiology of domestically acquired hepatitis E virus infection in Japan: assessment of the nationally reported surveillance data, 2007–2013. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:752–758. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micas F, Suin V, Peron JM, Scholtes C, Tuaillon E, Vanwolleghem T, et al. Analyses of clinical and biological data for French and Belgian immunocompetent patients infected with hepatitis E virus genotypes 4 and 3. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:645020. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.645020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeblaoui A, Haim-Boukobza S, Marchadier E, Mokhtari C, Roque-Afonso AM. Genotype 4 hepatitis e virus in France: an autochthonous infection with a more severe presentation. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:e122–126. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsubayashi K, Nagaoka Y, Sakata H, Sato S, Fukai K, Kato T, et al. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E caused by apparently indigenous hepatitis E virus strain in Hokkaido, Japan. Transfusion. 2004;44:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreier J, Knabbe C, Vollmer T. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E: NAT screening of blood donations and infectious dose. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallian P, Pouchol E, Djoudi R, Lhomme S, Mouna L, Gross S, et al. Transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E virus infection in France. Transfus Med Rev. 2019;33:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser L, Roque-Afonso AM, Beyloune A, Simonet M, Deau Fischer B, Burin des Roziers N, et al. Hepatitis E transmission by transfusion of Intercept blood system-treated plasma. Blood. 2014;123:796–797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-524348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colson P, Coze C, Gallian P, Henry M, De Micco P, Tamalet C. Transfusion-associated hepatitis E, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:648–649. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallian P, Lhomme S, Piquet Y, Saune K, Abravanel F, Assal A, et al. Hepatitis E virus infections in blood donors, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1914–1917. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satake M, Matsubayashi K, Hoshi Y, Taira R, Furui Y, Kokudo N, et al. Unique clinical courses of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E in patients with immunosuppression. Transfusion. 2017;57:280–288. doi: 10.1111/trf.13994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boland F, Martinez A, Pomeroy L, O’Flaherty N. Blood donor screening for hepatitis E virus in the European Union. Transfus Med Hemother. 2019;46:95–103. doi: 10.1159/000499121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domanovic D, Tedder R, Blumel J, Zaaijer H, Gallian P, Niederhauser C, et al. Hepatitis E and blood donation safety in selected European countries: a shift to screening? Euro Surveill. 2017;22:30514. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.16.30514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakata H, Matsubayashi K, Iida J, Nakauchi K, Kishimoto S, Sato S, et al. Trends in hepatitis E virus infection: Analyses of the long-term screening of blood donors in Hokkaido, Japan, 2005–2019. Transfusion. 2021;61:3390–3401. doi: 10.1111/trf.16700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abravanel F, Lhomme S, Chapuy-Regaud S, Mansuy JM, Boineau J, Saune K, et al. A fully automated system using transcription-mediated amplification for the molecular diagnosis of hepatitis E virus in human blood and faeces. J Clin Virol. 2018;105:109–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abravanel F, Sandres-Saune K, Lhomme S, Dubois M, Mansuy JM, Izopet J. Genotype 3 diversity and quantification of hepatitis E virus RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:897–902. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05942-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansuy JM, Peron JM, Abravanel F, Poirson H, Dubois M, Miedouge M, et al. Hepatitis E in the south west of France in individuals who have never visited an endemic area. J Med Virol. 2004;74:419–424. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baylis SA, Blumel J, Mizusawa S, Matsubayashi K, Sakata H, Okada Y, et al. World Health Organization International Standard to harmonize assays for detection of hepatitis E virus RNA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:729–735. doi: 10.3201/eid1905.121845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordes AK, Goudeva L, Lutgehetmann M, Wenzel JJ, Behrendt P, Wedemeyer H, et al. Risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis E virus infection from pool-tested platelets and plasma. J Hepatol. 2022;76:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bes M, Costafreda MI, Riveiro-Barciela M, Piron M, Rico A, Quer J, et al. Effect of hepatitis E virus RNA universal blood donor screening, Catalonia, Spain, 2017–2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:157–165. doi: 10.3201/eid2801.211466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillonel J, Gallian P, Sommen C, Couturier E, Piquet Y, Djoudi R, et al. [Assessment of a transfusion emergent risk: the case of HEV]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2014;21:162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2014.07.004. [In French.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewitt PE, Ijaz S, Brailsford SR, Brett R, Dicks S, Haywood B, et al. Hepatitis E virus in blood components: a prevalence and transmission study in southeast England. Lancet. 2014;384:1766–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapuy-Regaud S, Dubois M, Plisson-Chastang C, Bonnefois T, Lhomme S, Bertrand-Michel J, et al. Characterization of the lipid envelope of exosome encapsulated HEV particles protected from the immune response. Biochimie. 2017;141:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagashima S, Takahashi M, Kobayashi T, Tanggis, Nishizawa T, Nishiyama T, et al. Characterization of the quasi-enveloped hepatitis E virus particles released by the cellular exosomal pathway. J Virol. 2017;91:e00822–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00822-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costafreda MI, Sauleda S, Rico A, Piron M, Bes M. Detection of non-enveloped hepatitis E virus in plasma of infected blood donors. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1753–1760. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamp C, Blumel J, Baylis SA, Bekeredjian-Ding I, Chudy M, Heiden M, et al. Impact of hepatitis E virus testing on the safety of blood components in Germany - results of a simulation study. Vox Sang. 2018;113:811–813. doi: 10.1111/vox.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]