Abstract

Precision medicine strives for highly individualized treatments for disease under the notion that each individual’s unique genetic makeup and environmental exposures imprints upon them not only a disposition to illness, but also an optimal therapeutic approach. In the realm of rare disorders, genetic predisposition is often the predominant mechanism driving disease presentation. For such, mostly, monogenic disorders, a causal gene to phenotype association is likely. As a result, it becomes important to query the patient’s genome for the presence of pathogenic variations that are likely to cause the disease. Determining whether a variant is pathogenic or not is critical to these analyses and can be challenging, as many disease-causing variants are novel and, ergo, have no available functional data to help categorize them. This problem is exacerbated by the need for rapid evaluation of pathogenicity, since many genetic diseases present in young children who will experience increased morbidity and mortality without rapid diagnosis and therapeutics. Here, we discuss the utility of animal models, with a focus mainly on C. elegans, as a contrast to tissue culture and in silico approaches, with emphasis on how these systems are used in determining pathogenicity of variants with uncertain significance and then used to screen for novel therapeutics.

1. Introduction

One of the major contributions of genetics to society is the ability to diagnose, and often, treat, genetic disease. The process of achieving a diagnosis is frequently a long one and is referred to as the diagnostic odyssey (Carmichael et al., 2014; Sawyer et al., 2016). In the context of this review, the diagnostic odyssey refers to obtaining a complete molecular diagnosis for a patient’s set of symptoms. The first molecular genetic tests were developed to diagnose aneuploidy. Gross chromosomal aberrations remained the main form of genetic testing for decades with advances allowing the detection of ever smaller aberrations, a subject matter that has been extensively covered (Durmaz et al., 2015; Bejjani and Shaffer, 2006; Cheung et al., 2005). This review will focus on molecular testing for the detection and evaluation of small, typically <20bp, but frequently, single nucleotide mutations. Until recently, genetic diagnoses were obtained by single gene tests. The diagnostic odyssey traditionally was defined by ordering such a test, based on a physician’s best guess at what the causative gene may be, waiting on the result, which may take several weeks or months, then, upon receipt of a negative result, ordering the next most likely gene for testing (Xue et al., 2015). Such a process could take years until a genetic diagnosis, if any, is reached. The advent of panel testing allowed for simultaneous testing of multiple genes known to be involved in a disease (Fig. 1A). Several years after panels gained acceptance in the marketplace, the advent of the next generation of DNA sequencing technology was introduced. Unlike the prior DNA sequencing technology (Sanger), the introduction of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) was notable for two things: first, NGS traditionally required a longer timeline of many days to weeks to return a report (although state-of-the-art approaches can now sequence a subject in just a few hours), whereas Sanger sequencing data could be acquired within a day, and second, the cost of NGS per base was dramatically lower at $0.50/Mb compared to ~$500/Mb for Sanger. The market continues to grow with new technologies (e.g. long read, single molecule sequencing) and whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) are rapidly becoming the dominant data path for the pediatric clinical geneticist. For more review on the market and technology evolution, see these references (Levy and Myers, 2016; Adams and Eng, 2018; Levy and Boone, 2019).

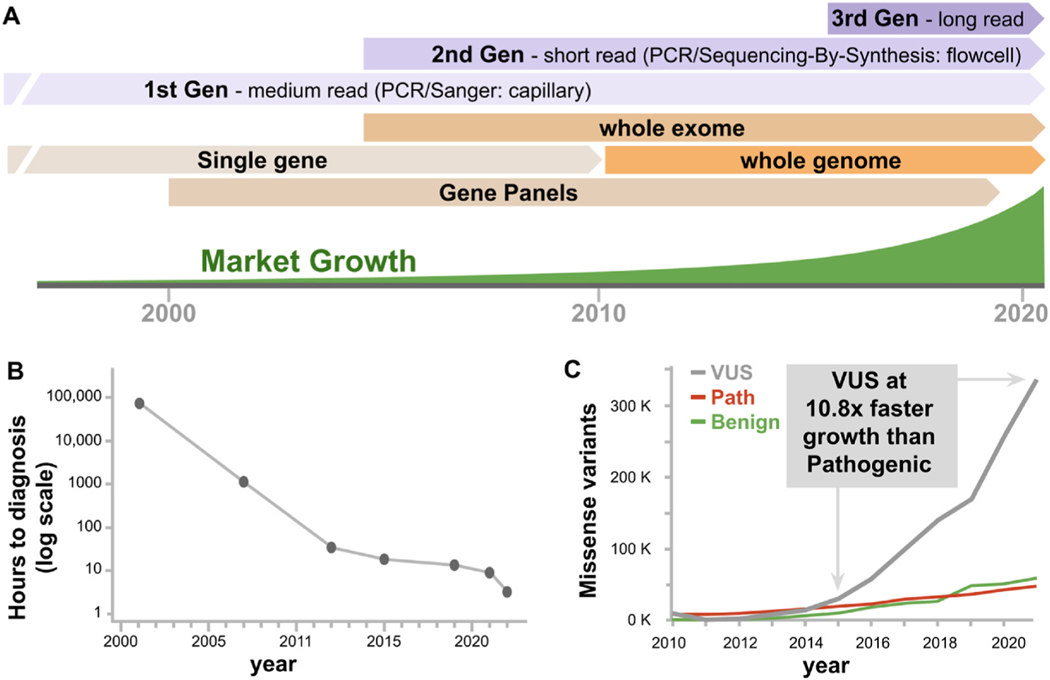

Fig. 1.

Components of the Diagnostic Odyssey. A) three generations of DNA sequencing technology are driving market growth and the types of analysis have expanded from single gene to whole genome. B) Speed to assembled genome for C) growth of variant classes in three groups assessed yearly from ClinVar database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). The VUS are annotations of “variants of uncertain significance” that also include conflicted annotations. Both Path and Benign include Likely Pathogenic and Likely Benign, respectively.

2. Genome wide sequencing

The ability to examine the whole genome places a huge amount of data at the fingertips of the clinician. The advent of clinical WES in the second half of 2011 radically changed the diagnostic odyssey by interrogating virtually all disease genes in a single test. This allowed a single test, with a 6–12 week turn-around-time to diagnose 25–35% of all patients including those with extremely rare, newly described diseases (Yang et al., 2013; de Ligt et al., 2012). WGS shortened the diagnostic odyssey further with slightly higher diagnostic rates than WES and improved Copy Number Variant (CNV) calling (Clark et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2018; Meienberg et al., 2016). Over the last 20 years, the time to identify all variants in a patient’s genome has dropped by over 10,000 fold and a genetic diagnosis can now be achieved the same day a sample is drawn from the patient (Fig. 1B) (Clark et al., 2018; Wright et al., 2018; Meienberg et al., 2016; Zanello et al., 2022; Richards et al., 2015a). The result is an ability to detect disease-causing variants in structural, coding and non-coding regions with profound rapidity. However, diagnostic yield has remained less than 50% for many heritable disease types, causing the diagnostic odyssey for many patients’ and families’ to remain a high social and economic burden (Zanello et al., 2022; Richards et al., 2015a; Dragojlovic et al., 2019; Gainotti et al., 2018).

One of the major factors hampering the attainment of higher diagnostic rates is the large number of Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS) that are uncovered by whole genome approaches and it is not possible to definitively determine whether the variant is pathogenic or benign with currently available data. Thus, even with a VUS in a gene that is a good candidate for the disease in question, it often remains non-diagnostic (Baldridge et al., 2017). The advent of inexpensive sequencing and the collective integration of genomic information from around the world is represented in the ClinVar database where VUS have rapidly outpaced pathogenic and benign assignments at an average of nearly 11x over the last 5 years (Fig. 1C). Misclassification of variants is critical to care and indeed, misclassification can result in malpractice lawsuits (Ray, 2016). This highlights a clear need for tests to delineate rapidly, inexpensively, and accurately pathogenic from non-pathogenic variants.

3. ACMG criteria and VUS

The advent of genome wide sequencing has faced clinical diagnostic labs with the daunting task of having to evaluate variants as pathogenic or benign across the genome. This burden is lightened in part by guidelines set by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) (Richards et al., 2015b). ACMG guidelines outline a rubric which categorizes different types of data, the strength of that data, and a mechanism to combine different types of data to determine the pathogenicity of a variant. The data integration creates lines of evidence supporting five types of assessment levels for a given variant (Box 1).

Box 1. Categorization criteria and their weights. Experimental evidence is highlighted in bold.

Supporting evidence:

The weakest evidence for determining pathogenicity, it includes: multiple lines of computational evidence, gene with low rates of benign and high rates of pathogenic missense variants, reputable database of pathogenic variants.

Moderate evidence:

Absent in population (normal) databases, variant affects amino acid that is established as harboring pathogenic mutations, mutational hotspot, in trans with known pathogenic (AR disease).

Strong evidence:

Statistical enrichment in disease cohort, causes same amino acid change as known pathogenic, well established functional studies. De novo mutation.

Very Strong evidence:

Predicted null variant in gene where loss of function is known disease mechanism.

The ACMG guidelines are necessarily conservative to minimize false positive identification of a benign variant as pathogenic. However, an unfortunate outcome of this stringency is that many variants are categorized as VUS and thus remain clinically non-actionable. The vast majority of data recognized by ACMG criteria stems either from large databases (normal population controls, disease cohorts) or is inherent to the particular patient in question (segregation of the allele in the family and the special case of de novo mutations in the proband). Practically, this means that a VUS will remain a VUS until, serendipitously, another patient with the same disease has an identical or similar variant (e.g. affects the same amino acid residue as previously identified). The only exceptions to this are computational methods to predict variant severity and functional studies to test the effect of a variant in the lab. Of these, computational methods are only considered ‘supporting’ evidence for a pathogenic or benign variant, whereas functional data is considered strong evidence. Thus, although computational methods to elucidate pathogenicity can be compelling, experimental model systems remain the gold standard.

4. Computational prediction of pathogenicity and identification of candidate therapeutics

Methods that can computationally sort pathogenic from non-pathogenic mutations have been pursued for decades. The goal of these algorithms is to generate a score that is correlated to the likelihood that the mutation in question damages protein function, and, by extension, causes disease. Some of the first computational methods to make these predictions, and that are still used today are SIFT (Ng and Henikoff, 2001) and PolyPhen (Sunyaev et al., 2000, 2001). These methods rely on a combination of experimentally determined substitution frequencies and known properties of the amino acids involved. Algorithms will typically first rely on multiple alignments of related proteins to determine whether individual amino acids, or protein regions have strong evolutionary conservation under the assumption that variants in these regions will be deleterious to protein function (Chenna et al., 2003). Later methods use complex, machine learning approaches to integrate many different forms of data or annotation, including ensemble predictions from multiple deleteriousness predictors. For example, CADD (Kircher et al., 2014) integrates data from transcription factor binding sites (Lesurf et al., 2016), evolutionary conservation measures (e.g. phyloP (Pollard et al., 2010)), and PolyPhen and SIFT. Newer methods, such as REVEL (Ioannidis et al., 2016) and BayesDel (Tian et al., 2019) use more complex machine learning approaches and integrate an even larger number of predictors (Pollard et al., 2010; Mort et al., 2014; Shihab et al., 2013; Carter et al., 2013; Choi and Chan, 2015; Schwarz et al., 2010; Flygare et al., 2018; King et al., 2005). Deleterious predictions can be made in just a few minutes and scores for many point mutations can be precalculated, allowing a simple ‘look up’ for any observed mutation (Liu et al., 2020). This makes in silico methods instantaneous, inexpensive, and comprehensive for point mutations. However, evaluating the validity of these methods can be challenging as there are a limited number of variants with ‘gold standard’ pathogenic or benign classification. Furthermore, many of the methods are not independent because they have been trained on these same variants. Yet, it is generally accepted that current in silico approaches have an overall accuracy performance of between 80 and 92% (Tian et al., 2019). Nevertheless, in silico approaches are rapidly evolving. For instance, the Genome-to-Protein Informatics Program (G2PIP) at the Mayo Clinic has starting to use complex structural inferences from a variety of simulation methods to foster pathogenicity assessments (Norris et al., 2021; Richter et al., 2021; Ahuja et al., 2020; Blackburn et al., 2020; Coban et al., 2020; Hines et al., 2019a, 2019b), often using machine-learning approaches to associate defects in structure-function relationships with pathogenicity effects. Advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence, in combination the ab initio structure prediction of Alphafold2 (Jumper et al., 2021), will, in the future, allow these simulation methods to rapidly address defects in novel proteins and help characterize their variants for developing targeted, personalized drug therapies (Coban et al., 2021). Overall there is a growing promise for molecular dynamics methods to become a major contributor to achieving pathogenicity assessments of clinical variants.

Despite their benefits, in silico methods currently have a number of shortcomings. First, they cannot easily distinguish between gain and loss of function (G/LOF) mutations. Although variants that are LOF and impede the function of a gene are the most common mechanism of disease, GOF variants may also alter or increase the function of a gene and thereby cause certain diseases. Additionally, some genes may cause different diseases depending on whether they harbor LOF or GOF mutations. For example, mutations in NALCN, may cause either autosomal dominant congenital contractures of the limbs and face, hypotonia, and developmental delay [MIM:616266], or autosomal recessive hypotonia, infantile, with psychomotor retardation and characteristic facies 1 [MIM: 615419], depending on whether the mutations are dominant GOF or biallelic LOF variants (Al-Sayed et al., 2013; Cochet-Bissuel et al., 2014; Chong et al., 2015). Indeed, in silico predictions frequently struggle to determine that GOF mutations are pathogenic at all (Rice et al., 2020; Rabadan Moraes et al., 2022), although in other contexts they perform well (Lee et al., 2009). Second, although performance is generally good across all genes, some predictors will struggle with certain genes (e.g. MYBPC3), although it is not clear why. Recently gaining traction is the use of gene-specific cutoffs, where a threshold score unique to a gene is used for determining pathogenicity (Wilcox et al., 2022; Johnston et al., 2021). Third, some mutation types may be particularly difficult to evaluate in silico, such as non-frameshift insertions/deletions (indels), primarily because these events are much less common than SNVs (Dong et al., 2014; Gravel et al., 2011) and thus it is more difficult to understand their evolutionary impact. While many predictors do not even attempt to establish the pathogenicity of in-frame indel events, others have developed specialized predictors for them (Douville et al., 2016; Hu and Ng, 2013). However, these specialized predictors still typically have an accuracy that is 10–20% lower than their SNV counterparts. Thus, despite the advantages of in silico models, in vivo and in vitro models are critical for providing insight on certain types of mutations and can be particularly useful for studying the spectrum of variant functional effects in some genes. Tissue culture systems for analysis of variant pathogenicity have been recently reviewed for multiplex assay methods (Findlay, 2021) and deep mutational scanning with CRISPR prime editing (Erwood et al., 2022). Indeed, massively parallel assays of variant effects are now widespread (Fowler and Fields, 2014; Findlay et al., 2018; Mighell et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2022; Newberry et al., 2020). These assays are advantageous in that they assay all (or virtually all) possible variants in a protein and determine pathogenicity. Although developing the assay can be difficult and time consuming, the experiment need only be executed once, and any subsequent variants of interest can be ‘looked up’ instantly. Development of an assay, however, is critical, and may not be possible with all genes. Typically assay readout is based on cell viability or growth and in situations where this approach is not feasible, deep mutational scanning is difficult to conduct. Deep mutational scanning is also challenged, like all competitive assays, in that some variants may simply outcompete others (Findlay, 2021), or that mutations may affect the protein function but not in a biologically relevant mechanism leading to poor clinical correlation (Kozek et al., 2020). Deep mutational scanning is conducted in single cells, and thus the phenotypic readouts may be limited. For complex phenotypes or diseases with wide phenotypic spectra, these approaches may miss more subtle phenotypic readouts that are visible in multicellular organisms. Thus, although deep mutational scanning is extremely powerful, other model systems are needed where this approach is either inapplicable, too expensive, or provides insufficient phenotype readout.

For drug discovery, the use of computer modeling methods has become an established approach. With the growth of new computer hardware such as graphical processing units that make parallel processing faster, as well as the availability of extensive data collections, the application of machine learning techniques in artificial intelligence have emerged as an essential tool in almost every stage in drug development. In drug design, the model constructed from the machine learning technique is applied to predict the target structure, binding sites, the biological activity of new ligands, and pharmacokinetic and toxicological profiles of compounds. Machine learning techniques also assist in the screening and optimization of compounds that will undergo preclinical and clinical trials. For over 10 years, classical machine learning techniques such as decision trees, random forests, artificial neural networks, and support vector machines have been applied to improve and optimize drug discovery and design processes (Hamet and Tremblay, 2017), as well as its integration with other computational approaches (Aggarwal and Murty, 2020). Conventional neural networks were popular in chemoinformatics during the early days of machine learning, but have largely been replaced with Deep Learning Neural Network (DLNN) techniques to avoid a tendency for overfitting in small data sets. DLNNs are widely applied for predictions at the small molecular and macro-molecular levels, and the popularity of DLNN is further increasing (Anighoro, 2022). Using DLNN, AlphaFold2 was able to predict single-domain protein structures consistently, with an accuracy of ~2 Å compared to experimental structures, as revealed by the 14th critical assessment of protein structure prediction blind test competition (Anighoro, 2022). As a result, machine learning methods in drug discovery are providing opportunities to increase efficiency across the drug discovery and development pipeline. Yet, although computer modeling is proving to be essential in targeted drug discovery, the predictions from the modeling will need to be validated in phenotypic tests - the identified in silico candidates need to be tested for their capacity to restore wildtype activity, preferably in an animal containing a clinical variant.

5. Animal models for diagnostics on clinically-relevant timescale

Animal models have been used extensively in the past to identify new disease genes, elucidate human genetics and discover new drugs (Birling et al., 2021; Giunti et al., 2021; Pandey and Nichols, 2011; Lieschke and Currie, 2007; Takai et al., 2020; Ochenkowska et al., 2022). However, using animal models as a diagnostic platform is relatively new. Animal models have several advantages over in silico approaches in determining pathogenicity. Heterologous systems exist which can detect and screen for the multidirectional functional consequence of a genetic variation, for example, differentiating LOF and GOF variants. Transfection assays in cell culture in certain contexts can be used to measure the subtleties of variant dysfunctional on a clinical time scale (Vanoye et al., 2018). Indeed, although this review focuses on animal models, in vitro systems show great promise for rapidly and, in some cases in a highly parallel manner, the deep mutational scanning of variants to generate insights on intrinsic protein properties and their behavior within cells, as well as help gain understanding of the consequences of human genetic variation (Fowler and Fields, 2014). Induced pluripotent stem cells are also attractive in allowing the modeling of not just the variant of interest, but the entire genetic background of the subject (Paes et al., 2016; Shcheglovitov and Peterson, 2021; Hamazaki et al., 2017; Rowe and Daley, 2019). Animal models have also been used to successfully differentiate between GOF and LOF variants by observing different phenotypic classes of aberrant function. For example, Bend et al. (2016) demonstrated that a C. elegans animal model bearing known pathogenic human mutations in its orthologous gene for NALCN showed lower sensitivity to aldicarb, while exhibiting hypercontraction and uncoordinated movement in gain of function variants, while LOF variants lead to generalized paralysis.

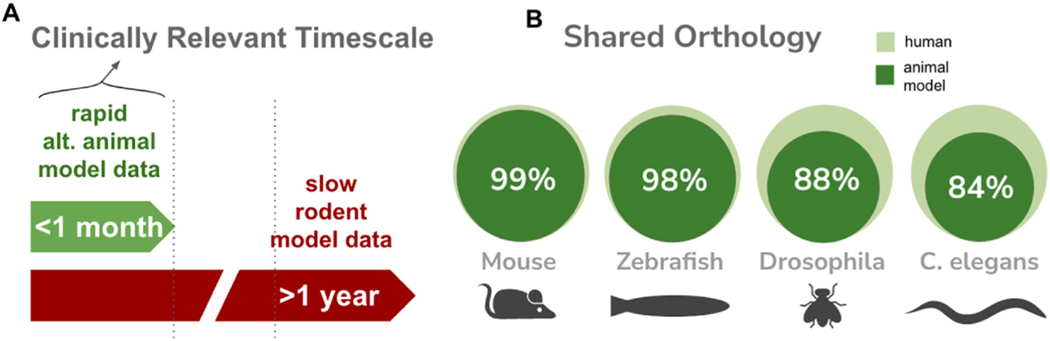

Although the mouse is the most common model utilized to understand human disease, the use of mice for functional studies of clinical variants requires a long timeline to install the variant into the mouse genome and then test progeny for abnormal activity (Fig. 2A). As a result, the application of mouse models to variant diagnostics is not practical in pediatric settings, where onset and disease progression can be rapid and life threatening. It is, therefore, preferential to use alternate models, where time to testing is a matter of days or weeks, rather than months (or sometimes, years). Therefore, alternate models such as C. elegans with its fast 3 day lifecycle, and Drosophila melanogaster (10 day lifecycle) and Danio rerio (crispant studies), are attractive as alternate animal models to use in acute diagnostic settings (Bellen et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022; Bek et al., 2021; Lange et al., 2021, 2022; McDiarmid et al., 2018; Lins et al., 2022; Di Rocco et al., 2022). Many of the same CRISPR engineering tools applied in C. elegans can also be applied in Drosophila to enable rapid installation of a variant and the implementation of phenotypic screens to characterize and quantify functional defects in progeny. In the case of D. rerio, morpholino knockdown screens (Guo et al., 2015) and the crispant technique (Lazcano et al., 2019; Watson et al., 2020), with mRNA rescue have been adapted to rapidly screen for variant abnormalities.

Fig. 2.

Properties of animal models. A) alternative animals can be used in approaches that allow for rapid testing for aberrant function of VUSs. B) Level of shared orthology for Important monogenic disease-associated genes. Genes with monogenic association identified via searching OMIM and ClinVar database (7524 genes) were screened for presence of orthologs in 4 animal models via Diopt search. The number of Genes not found were used to determine the percentage of shared orthology.

A major drawback in the use of these alternate, evolutionary distant animal models is the limitation of one-to-one orthology in important disease genes. For instance, although zebrafish share 70% similarity in its total genes with humans (Howe et al., 2013), the whole genome duplication as a recent evolutionary phenomenon in teleost fish (Chapter 8 The Zebrafish Genome, 1998), leads to a large fraction (>50%) of human orthologs having two versions in zebrafish. Also, in invertebrates, certain gene families are greatly expanded. For instance, in C. elegans, the number of genes compared to humans for Cytochrome P450s (Larigot et al., 2022) and GPCRs (Cardoso et al., 2012) are about 1.5-times higher and in nuclear hormone receptors it is six-times higher (Magner and Antebi, 2008). Inversely, some genes are under-represented. For instance, there are four NOTCH receptors in humans while worms have two and flies have only one. Nevertheless, orthologs in important disease-associated genes can be identified at a high enough rate to make the use of these alternate animal models feasible and attractive (Fig. 2B). Direct comparison of human variation to C. elegans variation has been generated in the ConVarT database (https://convart.org/) and nearly 13% of variations in humans already have a corresponding variant in C. elegans (Pir et al., 2022). As a result, alternate animal models are an effective platform to directly test for pathogenicity in many human variants.

6. Whole-gene humanization to improve clinical translation

A low degree of sequence conservation occurs at many variant positions. Combining ClinVar and gnomAD data, the ConVarT team observed only 31% of human variants occur at an amino acid position that is identical in human vs C. elegans sequence alignments (Pir et al., 2022). As a result, in regards to pathogenicity assessment, direct modeling in the native locus is often hampered by a lack of one-to-one correlation between variants across species. For example, we examined variants for amino acid conservation between C. elegans and humans in top 20 genes with highest numbers of pathogenic assessments. Using the ClinVar database restricted to Expert Panel curation, the variant totals for definitive Pathogenic (excluding “Likely Pathogenic”) yielded 591 variants, while the VUS yielded 707 variants. In the Pathogenic category, only 61.8% of variants occurred at positions conserved in C. elegans. For VUS, only 57.6% of variants were conserved. As a result, the use of native locus in the animal model for studying variant effects is limiting.

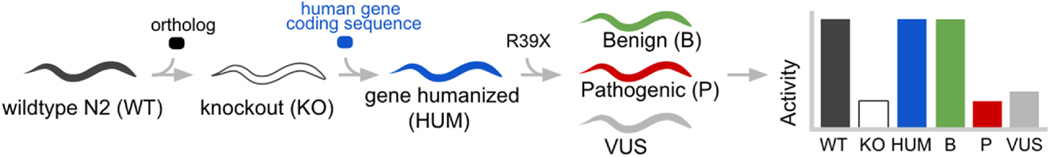

To access more variant effects and achieve a higher translatability of findings, a Whole-gene Humanized Animal Model (WHAM) can be made so that any amino acid position can be tested for its functional consequence when mutated (Fig. 3). Our team has explored the use of WHAM at the moderately conserved STXBP1 locus to screen for functional defects in clinically-observed variants (McCormick et al., 2021). Defects in STXBP1 are associated with autosomal dominant forms of juvenile epilepsy frequently caused by erroneous release of neurotransmitters at the presynaptic terminus. As of August 2022, there are 85 missense variants categorized in ClinVar as either Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic and only 70.6% occur at conserved positions. For the 36 Benign and Likely Benign variants, only 30.6% occur at conserved positions. As a result, the ability to model in the native locus of the unc-18 orthologous gene is challenged by a lack of amino acid conservation in the reference alleles. On the VUS and Conflicting Interpretation variants (n = 138), only 55.8% are at conserved positions. As a result, the training of a variant classifier on variants installed into the native unc-18 locus will not use the full potential of the established benign and pathogenic variants and, further, it will only address slightly more than half the variants of concern that need pathogenicity assessment. However, when a WHAM humanized locus is utilized, every clinical variant in STXBP1 can be addressed.

Fig. 3.

Outline of the Whole-gene Humanization in Animal Model (WHAM) approach in C. elegans. A native (WT) animal is CRISPR-edited to make a gene KO animal. A whole gene substitution is made with a human coding sequence in the native locus. Next, additional CRISPR edits are made to insert clinical variants (eg “R39X”) into the humanized locus which recreates a set of Patient Avatars that represent the genetic variation of a human. Phenotypic activity of the transgenic lines is measured to enable detection of variant deficiencies.

In the WHAM approach, it is necessary to alter the coding sequence of the inserted human gene in order to optimize expression in the animal model. For instance, the human genome coding sequence is 15% richer in GC content when compared to C. elegans (Piovesan et al., 2019). This can create a codon bias where certain codons that are abundantly used in the human genome are observed as rare in the C. elegans genome. To avoid the usage of rare codons in C. elegans, codon adapters are available to enable selection of more frequently used codons (Sun et al., 2013; Piovesan et al., 2013). A second attribute to enable adequate expression of the human coding sequence is to introduce artificial introns, which avoid triggering nonsense-mediated decay and degradation of intronless transcripts (Lacy-Hulbert et al., 2001; Moabbi et al., 2012). A third attribute of design is to detect and eliminate cryptic splice junctions via sequence scanning software (e.g. the NetGene2 program) (Hebsgaard et al., 1996; Brunak et al., 1991). The final attribute that measures the success of a humanized sequence is the observation of rescue of function relative to a knockout or loss-of-function allele in the parent line. A whole-gene humanized platform can be considered as valid for use, if statistically significant restoration of function can be achieved with the wildtype human coding sequence. So far, in 15 attempts at whole-gene humanization, 12 genes have led to rescue of function (Table 1). For the remaining three genes the sequence identity was below 39%, suggesting ortholog of low identity (<40%) will be at risk for the human gene not rescuing the function of a null allele.

Table 1.

List of genes where WHAM procedure was used to create gene humanized lines.

| Human Gene | Human Disease (OMIM) | Human Phenotype (Disgenet) | C. elegans Gene | C. elegans Phenotype (Wormbase) | Sequence Identity | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3F3A | Bryant-Li-Bhoj neurodevelopmental syndrome 1 (BRYLIB1; 619720) | muscle hypotonia, absent reflex, facial hypotonia, hypoxemia | his-71 | embryonic and larval lethal, slow growth, shortened lifespan | 99%∧ | rescue |

| VAMP2 | Neurodevelopmental disorder with hypotonia and autistic features with or without hyperkinetic movements (NEDHAHM; 618760) | muscular hypotonia, seizures, generalized hypotonia, cortical visual impairment | snb-1 | embryonic lethal, locomotion defective | 69% | rescue |

| STXlA | Neuro-developmental disorders (https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr493706) | hepatomegaly, diarrhea, recurrent respiratory infections, malabsorption | unc-64 | embryonic lethal, locomotion defective | 64% | rescue |

| CACNB4 | Episodic ataxia, type 5 (EA5; 613855), Epilepsy, idiopathic generalized, susceptibility to, 9 (EIG9; 607682), Epilepsy, juvenile myoclonic, susceptibility to, 6 (EJM6; 607682) | truncal ataxia, ataxia, senosory ataxia, motor ataxia | ccb-1 | embryonic and larval lethal, locomotion defective, | 63% | rescue |

| STXBPl | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy-4 (DEE4; 612164) | aura, seizures, hyperactive behavior, tremor | unc-18 | locomotion defective, paralyzed | 59% | rescue |

| KLC4 | Hereditary spastic paraplegia (PMID 26423925) | lordosis, spastic paraplegia, scoliosis, frontal bossing | klc-2 | embryonic and larval lethal, reduced brood size | 58.%∧ | rescue |

| SNAP25 | Congenital myasthenic syndrome-18 (CMS18; 616330) | myasthenia, diabetes mellitus, bipolar disorder, tics | ric-4 | embryonic and larval lethal, | 53% | rescue* |

| FOXGl | Rett syndrome (613454) | seizures, dystonia, monoclonic seizures, atonic absence seizures | fkh-2 | embryonic and larval lethal, sluggish | 51% | rescue |

| SLC6A4 | Major depressive disorder (MDD; 608516); Anxiety-related personality traits (607834); Obsessive-compulsive disorder (164230) | pulmonary hypertension, depressed mood, drug habituation, memory impairment | mod-5 | locomotion defective, shrotened lifespan, | 45% | rescue* |

| DYRK1A | Autosomal dominant intellectual developmental disorder-7 (MRD7; 614104) | aura, hyperactive behavior, seizures, abnormal behavior | mbk-1 | embryonic and larval lethal, slow growth, shortened lifespan, locomotion defective | 43%∧ | rescue |

| SLC2A1 | Dystonia-9 (DYT9; 601042); Early-onset absence epilepsy before age 4 years (EIG12; 614847); Stomatin-deficient cryohydrocytosis with neurologic defects (SDCHCN; 608885); GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 (GLUT1DS1; 606777) | seizures, dystonia, ataxia, absence seizures | fgt-1 | fat content increase, extended lifespan | 40%∧ | rescue |

| TARDBP | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 10, with or without frontotemporal dementia (ALS10; 612069) | quadriparesis, apathy, agitation, respiratory insufficiency due to muscle weakness | tdp-1 | oxidative sensitivity, exetended lifespan, salt sensitive | 39% | rescue |

| KCNQ2 | benign familial neonatal seizures-1 (BFNS1; 121200); developmental and epileptic encephalopathy-7 (DEE7; 613720); | seizures, myokymia, tonic/clonic seisures, dystonia | kqt-1 | pharynx pumping frequency reduced” | 36%∧ | failed” |

| GABRG2 | Familial febrile seizures-8 (FEB8; 607681); Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy-74 (DEE74; 618396); Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, type 3 (607681) | absence seizures, autistic behavior, obsessive-compulsive trait, delayed speech and language development | unc-49 | locomotion defective, PTZ sensitivity, | 33% | failed |

| LMNA | Cardiomyopathy, dilated, 1 A (115200); Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, type 2B1 (605588); Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (181350 and 616516); Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (176670); Lipodystrophy, familial partial, type 2 (151660); Malouf syndrome (212112); Mandibuloacral dysplasia (248370); Muscular dystrophy, congenital (613205) | sudden cardiac death, auriculo- ventricular dissociation, progeria, muscular dystrophy | lmn-1 | embryonic and larval lethal, shortened lifespan, nuclear position variant, reduced brood size | 29% | failed |

not reciprocal orthologs;

rescue in trans or with amino acid variant; “ failure due to lack of published phenotype in knockout.

7. Phenotyping: phenocopy and phenolog

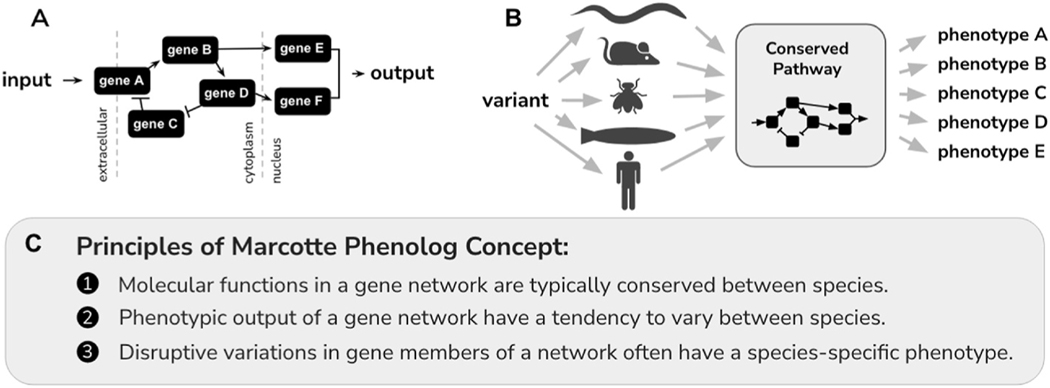

In one of the first WHAM techniques attempted, McDiarmid et al. replaced the C. elegans daf-18 locus with PTEN cDNA sequence (McDiarmid et al., 2018), which is a gene associated with cancer (Yehia et al., 2001), intellectual disability (DeSpenza et al., 2021) and autism (Cummings et al., 2022). Clinical features of PTEN deficiencies range from the intellectual (autism or developmental delay), dermatologic (lipomas, trichilemmomas, oral papillomas, or penile freckling), vascular (arteriovenous malformations or hemangiomas), to gastrointestinal (polyps). Leveraging off of the phenomenon that overexpression of human PTEN can rescue a daf-18 deficiency (Solari et al., 2005), McDiarmid installed a clinical variant (p.G129E) into their PTEN humanized locus. They found that hPTEN-p.G129E model had an increase in NaCl salt avoidance response and a decrease in mechano-stimulatory response, which was consistent with the daf-18 full deletion allele. One of the criticisms of the use of animal models is that a clinical variant installed in the animal model may not yield a phenocopy of the clinical presentation. Yet, because of conservation in evolution, the genetic output of a gene in one animal may yield a different genetic output in another animal, even though the underlying molecular function is highly similar. This conservation of molecular function with the possibility of drastically different phenotype effects was first described in detail by the Marcotte lab where they coined the term phenolog as the orthologous phenotypes occurring for the related genes between two different species (McGary et al., 2010). Using a hypothetical signaling pathway as an example, an input signal travels through a set of genes and leads to a specific output (Fig. 4A). When the same genetic variation is installed at conserved locations in orthologs of different species, the phenotypic output from the signaling pathway tends to result in species-specific phenotypes (Fig. 4B). The phenolog readout between species can be mapped for a variety of disease associated genes for loss of function variants with minimal overlap of transspecies phenotype observed (see Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Phenolog Concept. A) An input signal of information is transferred between genes and leads to a specific output from the cell. B) Because signaling pathways can evolve to have different outputs, a variant installed into a highly-conserved pathway gene, can lead to phenotypic responses that depend on the organism chosen. C) Listed principles of the phenolog concept.

In computational work with unsupervised machine learning, the aggregation of orthologous phenotypes, along with integration of paralog and multispecies analysis, has been used to detect existing and novel genes contributing to human disease of epilepsy and atrial fibrillation (Woods et al., 2013). Intriguingly, it has been noted that orthologous phenotypes from the same genetic signaling pathway can be observed to have different phenotypic consequences in the same animal depending on which tissue specific context are present (Golden, 2017). As a result, it has been noted that the understanding of phenolog readouts in model organisms and their predictive power for understanding human disease based off of a disparaging phenotypic presentation “mark one of those uncommon occasions in science in which intuition built on years of experience fails completely” (Linghu and DeLisi, 2010).

8. Rapid diagnostics in a clinical setting

As discussed earlier, the advent of the next generation sequencing revolution has decreased the turnaround time for diagnosing a patient (see Fig. 2A), which was demonstrated at Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in 2018. In less than 24 h (Clark et al., 2019) a patient was sequenced and a pathogenic mutation (p.L292P) in KCNQ2 (Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 7 [MIM: 613720]) was identified. Although it has now been shown a patient’s genome can be fully sequenced and the causative variants can be diagnosed in as little as 4 h (Gorzynski et al., 2022), the practical and routine turnaround time for a genetic diagnosis is approximately 13 h (Owen et al., 2021). Despite the increased expense of very rapid whole-genome sequencing, it repeatedly results in overall cost savings for pediatric/neonatal conditions in acute care settings (Dimmock et al., 2021; Sanford Kobayashi et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2017; Stark et al., 2016, 2017, 2019; Schofield et al., 2019; Yeung et al., 2020). Diagnosing neonates with genetic disease comes with its own set of challenges. Primarily this involves the rapid and evolving phenotype of patients, that is, the ‘classic’ phenotype may not present until the child is older, or the fragility of the patient, that is, an ineffectively treated patient can die quickly and suddenly. This has two major consequences: first, because the patient may present non-classically, it is difficult to establish a strong genotype-phenotype correlation and the result is a higher rate of VUS being reported. Second, because these patients are fragile, a diagnosis is needed rapidly. Yet, when the variant in question is identified as a VUS, the clinical actionability is drawn into question. Although in silico prediction tools play an important role in the rapid evaluation of variants, they typically cannot alter a VUS classification to Pathogenic, however animal model data can yield definitive and actionable results.

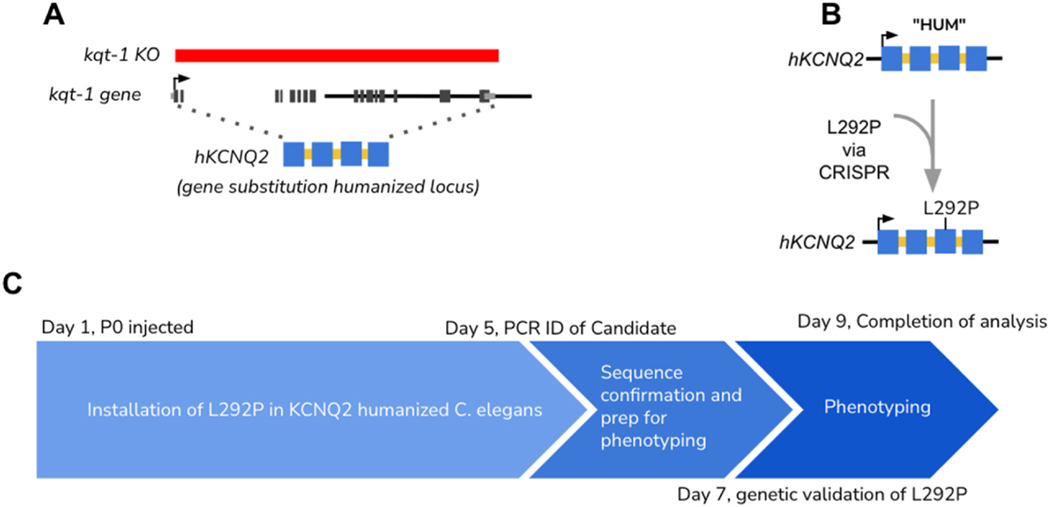

To provide the functional data that would meet ACMG guidelines for determining a Likely Benign or Likely Pathogenic assessment, we set up a demonstration project to determine how quickly a variant install can be performed into the humanized C. elegans locus. CRISPR-based gene editing methods were tested for the speed to insert a clinical variant in a humanized KCNQ2 locus (Fig. 5A). From ordering the gene targeting CRISPR reagents to the measurement of an electrophysiology phenotype using a ScreenChip microfluidics apparatus (InVivo Biosystems), the animal representation (Clinical Avatar) of the patient variant p. L292P was made and analyzed in less than 10 days (Fig. 5B). Although this approach requires a pre-existing humanized platform, which can take several months to develop, once the platform is generated, installing new variants requires approximately five days to generate the F0 worm, two days to validate the variant, and one day to phenotype a suitable number of worms (Fig. 5C). Although measuring phenotypes in multiple worms, and with technical replicates is critical, automated methods exist for measuring various worm phenotypes and determining variant pathogenicity, meaning that multiple batches of worms could be evaluated in a day or two. Thus it is possible to identify a patient, identify a candidate causal mutation and evaluate the pathogenicity of that mutation in <2 weeks.

Fig. 5.

Whole-gene humanization for functional assessment of clinical variants. A) Schematic for creation of a kqt-1 KO (full coding sequence deletion generated by CRISPR gene editing) and insertion of human hKCNQ2 sequence (Uniprot: O43526–1) as a CRISPR-mediated WHAM humanization. B) CRISPR-based gene editing inserted L292P variant into humanized locus C) Beginning with injection of guides on day one, worms are established and tested for genetic variants by day 5. Sequencing validated worms are identified by day 7 and phenotyping and evaluation is completed by day 9.

9. Drug screening pipelines

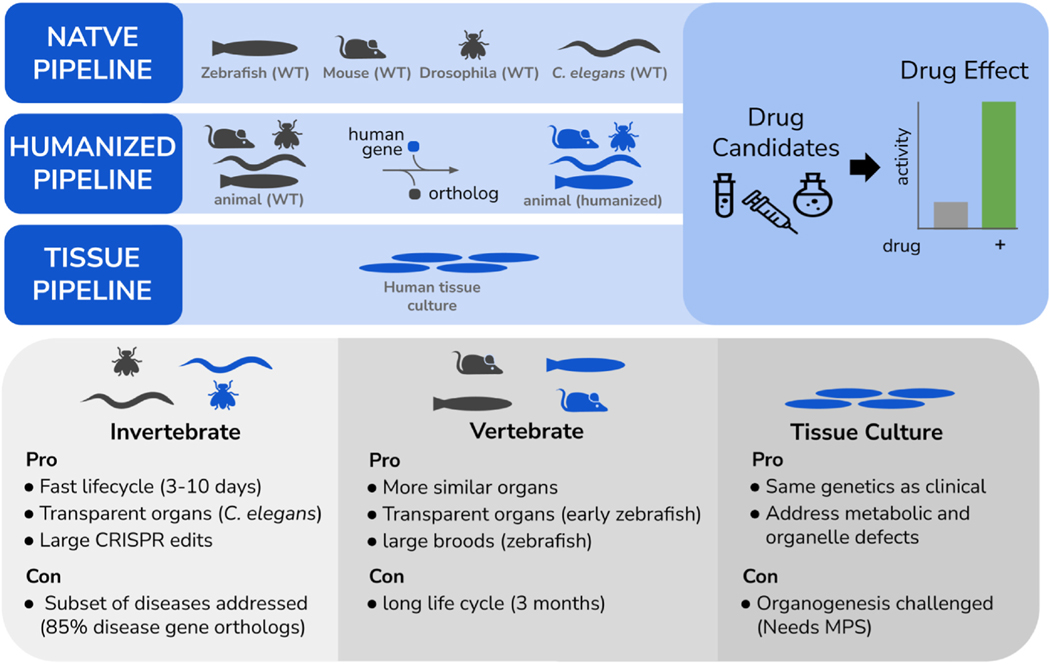

In animal models, the installation of a clinical variant into a WHAM-humanized locus for distant orthologs, or modeling directly in the native locus for orthologs of high sequence identity, creates a patient-specific platform for drug screening (Fig. 6). Similarly, in tissue culture, the use of patient derived tissues with isogenic controls, or creation of cell lines with CRISPR-based edits to install variants, also create a drug screening platform that is specific to the patient. These systems can be used in phenotypic screens to find candidates that reverse abnormal phenotypes back to normal activity. Phenotypic screens have the powerful advantage over in vitro target-engagement screens, because often toxicity issues are simultaneously being addressed in the engagement screen. A variety of screening modalities have been explored in clinical variant contexts. For instance a human haploid cell line CRISPR engineered to contain pathogenic variants in NPC1, the cause of Niemann-Pick disease type C [MIM:257220], was used to uncover that nearly 60% of missense variants are deleterious and can be used for patient specific drug screening (Erwood et al., 2019). Pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) also have significant potential for functional genomics and drug discovery studies (Brooks et al., 2022). Using the robust capacity of iPSCs to be differentiated into cardiomyocytes, pathogenic variants in the TNNT2 gene were compared to its isogenic control in a screening of a Prestwich library and identified two small molecule kinase inhibitors, Go-6976 and SB-203580, which were found in an unbiased phenotype reversal screen (Perea-Gil et al., 2022). The combinatorial application of these inhibitors was then found to reverse the contractile dysfunction in a host of related cardiomyopathy genes (TTN, LMNA, PLN, TMP1, and LAMA2) via the induction of one-carbon metabolism enzymes that increase the production of serine and glycine, whose levels are negatively correlated with cardiovascular disease (Perea-Gil et al., 2022; Rom et al., 2018).

Fig. 6.

Three types of pipelines for performing phenotypic screens for personalized therapeutics discovery. Native pipeline involves the use of gene editing in the disease-gene ortholog to install the clinical variant seen in the patient. Humanized pipeline utilizes human gene expression in the animal as the locus for installation of a clinical variant. Tissue pipeline uses human sourced cells as either patient derived or reference line gene edited at clinical variant site so that isogenic controlled studies can be performed. Pros and cons of each pipeline are noted.

For animal model screens, humanized mice for disease models have been extensively reviewed (Brehm et al., 2010; Yong et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2008; Gurumurthy and Lloyd, 2019; Le Bras, 2020). However, in one example applied to small vesicle disease caused by cysteine imbalance in the extracellular domain of NOTCH3, a knockout mouse was rescued in trans with human NOTCH3 coding sequence when monitored for biomarker expression of α-smooth muscle (a marker of mural cells that is not affected by changes in NOTCH3 activity), however, rescue failed for a construct containing the p. C455R pathogenic variant (Machuca-Parra et al., 2017). The same authors demonstrated an agonist antibody (A13) can be therapeutic in restoring NOTCH3 signaling in the p. C455R impaired mice. In a Drosophila example, TBC1D24 is associated with epilepsy and dystonia [MIM: 608105; 220500]. When the TBC1D24-p.G501R variant was put into a gene humanized locus, the mouse was found to have both activity and synaptic vesicle trafficking defects (Lüthy et al., 2019). Next, the authors screened antioxidants and found N-acetylcysteine amide and α-tocopherol were able to restore wild type activity in the context of the p. G501R variant. In zebrafish, drug discovery has been performed on the Scn1lab sodium channel (ortholog of epilepsy-associated SCN1A) using a variant derived by chemical mutagenesis (Muto et al., 2005). In a screen of over 3000 compounds, trazodone and lorcaserin, were identified as two FDA-approved compounds to bring to clinical trials (Baraban et al., 2013; Griffin et al., 2017). Lorcaserin is currently in phase 3 clinical trials for treatment of Dravet-associated epilepsy (A Study of Lorcaserin as, 2022). In C. elegans, the ability to handle the animal in liquid format allows for high-throughput screens in 1536-well plates of over 350,000 compounds in under 6 weeks (Leung et al., 2013). This high throughput screening capacity was applied to a repurposing drug screen to find modulators of PMM2-CDG, a rare disease congenital disorder of glycosylation (Iyer et al., 2019). A p. F119L clinical variant was constructed in the C. elegans by our team for the native ortholog of PMM2 (p.F125L of the pmm-2 gene). Using a bortezomib hypersensitization assay, the Microsource Spectrum drug repurposing library (2560 compounds) was screen and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) identified as a lead restoring normal bortezomib sensitivity. Because CHCA is a potent aldose reductase inhibitor (ARI), these authors performed a secondary screening of ARIs and identified epalrestat, an FDA approved drug for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, as having a similar capacity to reverse the bortezomib phenotype. After validation testing patient-derived fibroblasts, a successful n 1 clinical trial was performed, which has since been expanded to a 40-patient cohort, phase 3 trial (Oral Epalrestat Therapy in Pediatric, 2022). Although WHAM-humanized animals have not been directly used in drug screens, prior screens at native loci have yielded promising results that can be expected to translate with higher success with studies done on WHAM-humanized configurations.

10. Conclusions

Variants of uncertain significance are a challenge in current clinical molecular genetics practice and an issue that is only likely to grow. Various methods have been developed to help distinguish between pathogenic and benign variants including computational and in vitro model systems. Animal models have several advantages over other systems in that they can provide a rich set of phenotypes to measure and provide a platform for drug testing and discovery. Further, animal model data can be directly integrated to inform machine learning models and increase prediction accuracies. While some genes may have very specific effects in a single cell type, others may cause more systemic disease and may benefit from a whole animal model system. Advances in gene editing techniques have enabled both whole gene replacement and rapid production of specific variants in animal models. Combined with the rapid life-cycle of invertebrates, this has allowed development of rapid, whole-animal functional tests for pathogenicity of VUS and is opening the door to personalized medicine discoveries. As a result, the use of alternative animal models shows great promise in enabling personalized genetic medicine to come into fruition.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R43AG061978, 2018; R43NS113691, 2019, R43GM133229, 2019; R43HG010852, 2020].

Glossary

- CNV

Copy number variant:A large deletion or duplication of thousands to millions of DNA base pairs

- Diagnostic Yield

The proportion of cases which have a molecular diagnosis that accounts for the majority of the patient’s symptoms

- Diagnostic Odyssey

The journey a patient undertakes in achieving an accurate diagnosis of their symptoms

- DLNN

Deep Learning Neural Network

- Gene-Specific

Threshold Cutoffs Computation approach to pathogenicity detection where each gene has a unique cut-off value in score for assessment as deleterious

- GOF

Gain of function:A variant that alters or increases the function of a protein

- In-frame Indels

insertions or deletions that retain coding frame

- LOF

Loss of function:A variant that decreases or obliterates the function of a protein

- NGS

Next generation sequencing:Typically used to refer to any type of high-throughput (non-Sanger) sequencing. Frequently separated into 2nd generation, Illumina short read sequencing and 3rd generation, long read single-molecule sequencing

- VUS

Variant of uncertain significance: A variant which, by ACMG criteria, can neither be classified as benign or pathogenic

- WES

Whole exome sequencing:A method of DNA sequencing that attempts to enrich DNA sequence data from the protein coding portion (or a other subset of) the whole genome

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing:A method of DNA sequencing that does not deliberately attempt to bias where sequenced DNA is obtained from the genome

- WHAM

Whole-gene Humanized Animal Model:The act of replacing a non-human animal gene with its human ortholog in its native locus

References

- A study of lorcaserin as adjunctive treatment in participants with Dravet syndrome - full text view - ClinicalTrials.gov [cited 23 Aug 2022]. Available: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04572243.

- Adams DR, Eng CM, 2018. Next-generation sequencing to diagnose suspected genetic disorders. N. Engl. J. Med 379, 1353–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal M, Murty MN, 2020. Machine Learning in Social Networks: Embedding Nodes, Edges, Communities, and Graphs. Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja AS, Selvam P, Vadlamudi C, Chopra H, Richter JE Jr., Macklin SK, et al. , 2020. Genomics combined with a protein informatics platform to assess a novel pathogenic variant c.1024 A>G (p.K342E) in OPA1 in a patient with autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 41, 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sayed MD, Al-Zaidan H, Albakheet A, Hakami H, Kenana R, Al-Yafee Y, et al. , 2013. Mutations in NALCN cause an autosomal-recessive syndrome with severe hypotonia, speech impairment, and cognitive delay. Am. J. Hum. Genet 93, 721–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anighoro A, 2022. Deep learning in structure-based drug design. Methods Mol. Biol 2390, 261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge D, Heeley J, Vineyard M, Manwaring L, Toler TL, Fassi E, et al. , 2017. The Exome Clinic and the role of medical genetics expertise in the interpretation of exome sequencing results. Genet. Med 19, 1040–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban SC, Dinday MT, Hortopan GA, 2013. Drug screening in Scn1a zebrafish mutant identifies clemizole as a potential Dravet syndrome treatment. Nat. Commun 4, 2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG, 2006. Application of array-based comparative genomic hybridization to clinical diagnostics. J. Mol. Diagn 8, 528–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bek JW, Shochat C, De Clercq A, De Saffel H, Boel A, Metz J, et al. , 2021. Lrp5 mutant and crispant zebrafish faithfully model human osteoporosis, establishing the zebrafish as a platform for CRISPR-based functional screening of osteoporosis candidate genes. J. Bone Miner. Res 36, 1749–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen HJ, Wangler MF, Yamamoto S, 2019. The fruit fly at the interface of diagnosis and pathogenic mechanisms of rare and common human diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet 28, R207–R214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bend EG, Si Y, Stevenson DA, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Newcomb TM, Jorgensen EM, et al. , 2016. NALCN channelopathies: distinguishing gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations. Neurology 87, 1131–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birling M-C, Yoshiki A, Adams DJ, Ayabe S, Beaudet AL, Bottomley J, et al. , 2021. A resource of targeted mutant mouse lines for 5,061 genes. Nat. Genet 53, 416–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn PR, Carter JM, Oglesbee D, Westendorf JJ, Neff BA, Stichel D, et al. , 2020. An activating germline variant associated with a tumor entity characterized by unilateral and bilateral chondrosarcoma of the mastoid. HGG Adv 1, 100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras A, 2020. Rare disease mouse models. Lab. Anim 49, 313–313. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm MA, Shultz LD, Greiner DL, 2010. Humanized mouse models to study human diseases. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes 17, 120–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks IR, Garrone CM, Kerins C, Kiar CS, Syntaka S, Xu JZ, et al. , 2022. Functional genomics and the future of iPSCs in disease modeling. Stem Cell Rep. 17, 1033–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunak S, Engelbrecht J, Knudsen S, 1991. Prediction of human mRNA donor and acceptor sites from the DNA sequence. J. Mol. Biol 220, 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso JCR, Felix RC, Fonseca VG, Power DM, 2012. Feeding and the rhodopsin family g-protein coupled receptors in nematodes and arthropods. Front. Endocrinol 3, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael N, Tsipis J, Windmueller G, Mandel L, Estrella E, 2014. Is it going to hurt?”: the impact of the diagnostic odyssey on children and their families. J. Genet. Counsel 24, 325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter H, Douville C, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Karchin R, 2013. Identifying Mendelian disease genes with the variant effect scoring tool. BMC Genom. 14 (Suppl. 3), S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapter 8 The Zebrafish Genome, 1998. Methods in Cell Biology. Academic Press, pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, et al. , 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3497–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung SW, Shaw CA, Yu W, Li J, Ou Z, Patel A, et al. , 2005. Development and validation of a CGH microarray for clinical cytogenetic diagnosis. Genet. Med 7, 422–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Chan AP, 2015. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics 31, 2745–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong JX, McMillin MJ, Shively KM, Beck AE, Marvin CT, Armenteros JR, et al. , 2015. De novo mutations in NALCN cause a syndrome characterized by congenital contractures of the limbs and face, hypotonia, and developmental delay. Am. J. Hum. Genet 96, 462–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, Stark Z, Farnaes L, Tan TY, White SM, Dimmock D, et al. , 2018. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom Med 3, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, Hildreth A, Batalov S, Ding Y, Chowdhury S, Watkins K, et al. , 2019. Diagnosis of genetic diseases in seriously ill children by rapid whole-genome sequencing and automated phenotyping and interpretation. Sci. Transl. Med 11 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban MA, Blackburn PR, Whitelaw ML, van Haelst MM, Atwal PS, Caulfield TR, 2020. Structural models for the dynamic effects of loss-of-function variants in the human SIM1 protein transcriptional activation domain. Biomolecules 10. 10.3390/biom10091314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban MA, Fraga S, Caulfield TR, 2021. Structural and computational perspectives of selectively targeting mutant proteins. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol 18, 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochet-Bissuel M, Lory P, Monteil A, 2014. The sodium leak channel, NALCN, in health and disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci 8, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings K, Watkins A, Jones C, Dias R, Welham A, 2022. Behavioural and psychological features of PTEN mutations: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder characteristics. J. Neurodev. Disord 14, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSpenza T Jr., Carlson M, Panchagnula S, Robert S, Duy PQ, Mermin-Bunnell N, et al. , 2021. PTEN mutations in autism spectrum disorder and congenital hydrocephalus: developmental pleiotropy and therapeutic targets. Trends Neurosci. 44, 961–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock D, Caylor S, Waldman B, Benson W, Ashburner C, Carmichael JL, et al. , 2021. Project Baby Bear: rapid precision care incorporating rWGS in 5 California children’s hospitals demonstrates improved clinical outcomes and reduced costs of care. Am. J. Hum. Genet 108, 1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Walker MF, Carriero NJ, DiCola M, Willsey AJ, Ye AY, et al. , 2014. De novo insertions and deletions of predominantly paternal origin are associated with autism spectrum disorder. Cell Rep. 9, 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douville C, Masica DL, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Gygax DM, Kim R, et al. , 2016. Assessing the pathogenicity of insertion and deletion variants with the variant effect scoring tool (VEST-Indel). Hum. Mutat 37, 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragojlovic N, van Karnebeek CDM, Ghani A, Genereaux D, Kim E, Birch P, et al. , 2019. The cost trajectory of the diagnostic care pathway for children with suspected genetic disorders. Genet. Med 22, 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz AA, Karaca E, Demkow U, Toruner G, Schoumans J, Cogulu O, 2015. Evolution of genetic techniques: past, present, and beyond. BioMed Res. Int 2015, 461524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwood S, Brewer RA, Bily TMI, Maino E, Zhou L, Cohn RD, et al. , 2019. Modeling Niemann-Pick disease type C in a human haploid cell line allows for patient variant characterization and clinical interpretation. Genome Res. 29, 2010–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwood S, Bily TMI, Lequyer J, Yan J, Gulati N, Brewer RA, et al. , 2022. Saturation variant interpretation using CRISPR prime editing. Nat. Biotechnol 40, 885–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Callow MG, Fortin J-P, Khan Z, Bray D, Costa M, et al. , 2022. A saturation mutagenesis screen uncovers resistant and sensitizing secondary mutations to clinical KRAS inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 119, e2120512119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay GM, 2021. Linking genome variants to disease: scalable approaches to test the functional impact of human mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet 30, R187–R197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay GM, Daza RM, Martin B, Zhang MD, Leith AP, Gasperini M, et al. , 2018. Accurate classification of BRCA1 variants with saturation genome editing. Nature 562, 217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flygare S, Hernandez EJ, Phan L, Moore B, Li M, Fejes A, et al. , 2018. The VAAST Variant Prioritizer (VVP): ultrafast, easy to use whole genome variant prioritization tool. BMC Bioinf. 19, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DM, Fields S, 2014. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nat. Methods 11, 801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainotti S, Mascalzoni D, Bros-Facer V, Petrini C, Floridia G, Roos M, et al. , 2018. Meeting patients’ right to the correct diagnosis: ongoing international initiatives on undiagnosed rare diseases and ethical and social issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 15, 2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunti S, Andersen N, Rayes D, De Rosa MJ, 2021. Drug discovery: insights from the invertebrate Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol Res Perspect 9, e00721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A, 2017. From phenologs to silent suppressors: identifying potential therapeutic targets for human disease. Mol. Reprod. Dev 84, 1118–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorzynski JE, Goenka SD, Shafin K, Jensen TD, Fisk DG, Grove ME, et al. , 2022. Ultrarapid nanopore genome sequencing in a critical care setting. N. Engl. J. Med 386, 700–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel S, Henn BM, Gutenkunst RN, Indap AR, Marth GT, Clark AG, et al. , 2011. Demographic history and rare allele sharing among human populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 11983–11988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin A, Hamling KR, Knupp K, Hong S, Lee LP, Baraban SC, 2017. Clemizole and modulators of serotonin signalling suppress seizures in Dravet syndrome. Brain 140, 669–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D-C, Gong L, Regalado ES, Santos-Cortez RL, Zhao R, Cai B, et al. , 2015. MAT2A mutations predispose individuals to thoracic aortic aneurysms. Am. J. Hum. Genet 96, 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurumurthy CB, Lloyd KCK, 2019. Generating mouse models for biomedical research: technological advances. Dis Model Mech 12. 10.1242/dmm.029462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki T, El Rouby N, Fredette NC, Santostefano KE, Terada N, 2017. Concise review: induced pluripotent stem cell research in the era of precision medicine. Stem Cell. 35, 545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamet P, Tremblay J, 2017. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Metabolism 69S, S36–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebsgaard SM, Korning PG, Tolstrup N, Engelbrecht J, Rouzé P, Brunak S, 1996. Splice site prediction in Arabidopsis thaliana pre-mRNA by combining local and global sequence information. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 3439–3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines SL, Mohammad AN, Jackson J, Macklin S, Caulfield TR, 2019a. Integrative data fusion for comprehensive assessment of a novel CHEK2 variant using combined genomics, imaging, and functional-structural assessments via protein informatics. Mol Omics 15, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines SL, Richter JE Jr., Mohammad AN, Mahim J, Atwal PS, Caulfield TR, 2019b. Protein informatics combined with multiple data sources enriches the clinical characterization of novel TRPV4 variant causing an intermediate skeletal dysplasia. Mol Genet Genomic Med 7, e566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, et al. , 2013. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496, 498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Ng PC, 2013. SIFT Indel: predictions for the functional effects of amino acid insertions/deletions in proteins. PLoS One 8, e77940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, et al. , 2016. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet 99, 877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Sam FS, DiPrimio N, Preston G, Verheijen J, Murthy K, et al. , 2019. Repurposing the aldose reductase inhibitor and diabetic neuropathy drug epalrestat for the congenital disorder of glycosylation PMM2-CDG. Dis Model Mech 12. 10.1242/dmm.040584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JJ, Dirksen RT, Girard T, Gonsalves SG, Hopkins PM, Riazi S, et al. , 2021. Variant curation expert panel recommendations for RYR1 pathogenicity classifications in malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Genet. Med 23, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. , 2021. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DC, Taylor J, Elnitski L, Chiaromonte F, Miller W, Hardison RC, 2005. Evaluation of regulatory potential and conservation scores for detecting cis-regulatory modules in aligned mammalian genome sequences. Genome Res. 15, 1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J, 2014. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet 46, 310–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozek KA, Glazer AM, Ng C-A, Blackwell D, Egly CL, Vanags LR, et al. , 2020. High-throughput discovery of trafficking-deficient variants in the cardiac potassium channel K11.1. Heart Rhythm 17, 2180–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Hulbert A, Thomas R, Li XP, Lilley CE, Coffin RS, Roes J, 2001. Interruption of coding sequences by heterologous introns can enhance the functional expression of recombinant genes. Gene Ther. 8, 649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange KI, Tsiropoulou S, Kucharska K, Blacque OE, 2021. Interpreting the pathogenicity of Joubert syndrome missense variants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dis Model Mech 14. 10.1242/dmm.046631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange KI, Best S, Tsiropoulou S, Berry I, Johnson CA, Blacque OE, 2022. Interpreting ciliopathy-associated missense variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in Caenorhabditis elegans. Hum. Mol. Genet 31, 1574–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larigot L, Mansuy D, Borowski I, Coumoul X, Dairou J, 2022. Cytochromes P450 of : implication in biological functions and metabolism of xenobiotics. Biomolecules 12. 10.3390/biom12030342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazcano I, Rodríguez-Ortiz R, Villalobos P, Martínez-Torres A, Solís-Saínz JC, Orozco A, 2019. Knock-down of specific thyroid hormone receptor isoforms impairs body plan development in zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol 10, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Zhang Y, Mukhyala K, Lazarus RA, Zhang Z, 2009. Bi-directional SIFT predicts a subset of activating mutations. PLoS One 4, e8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesurf R, Cotto KC, Wang G, Griffith M, Kasaian K, Jones SJM, et al. , 2016. ORegAnno 3.0: a community-driven resource for curated regulatory annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D126–D132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CK, Wang Y, Malany S, Deonarine A, Nguyen K, Vasile S, et al. , 2013. An ultra high-throughput, whole-animal screen for small molecule modulators of a specific genetic pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 8, e62166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SE, Boone BE, 2019. Next-generation sequencing strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 9. 10.1101/cshperspect.a025791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SE, Myers RM, 2016. Advancements in next-generation sequencing. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet 17, 95–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke GJ, Currie PD, 2007. Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet 8, 353–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BWM, Kleefstra T, Yntema HG, Kroes T, et al. , 2012. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N. Engl. J. Med 367, 1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linghu B, DeLisi C, 2010. Phenotypic connections in surprising places. Genome Biol. 11, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lins J, Hopkins CE, Brock T, Hart AC, 2022. The use of CRISPR to generate a whole-gene humanized and the examination of P301L and G272V clinical variants, along with the creation of deletion null alleles of and loci. MicroPubl Biol 2022. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li C, Mou C, Dong Y, Tu Y, 2020. dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med. 12, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthy K, Mei D, Fischer B, De Fusco M, Swerts J, Paesmans J, et al. , 2019. TBC1D24-TLDc-related epilepsy exercise-induced dystonia: rescue by antioxidants in a disease model. Brain 142, 2319–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca-Parra AI, Bigger-Allen AA, Sanchez AV, Boutabla A, Cardona-Vélez J, Amarnani D, et al. , 2017. Therapeutic antibody targeting of Notch3 signaling prevents mural cell loss in CADASIL. J. Exp. Med 214, 2271–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner DB, Antebi A, 2008. Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear receptors: insights into life traits. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol 19, 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick K, Brock T, Wood M, Guo L, McBride K, Kim C, et al. , 2021. A gene replacement humanization platform for rapid functional testing of clinical variants in epilepsy-associated STXBP1. bioRxiv 2021. 10.1101/2021.08.13.453827.08.13.453827. [DOI]

- McDiarmid TA, Au V, Loewen AD, Liang J, Mizumoto K, Moerman DG, et al. , 2018. CRISPR-Cas9 human gene replacement and phenomic characterization in to understand the functional conservation of human genes and decipher variants of uncertain significance. Dis Model Mech 11. 10.1242/dmm.036517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGary KL, Park TJ, Woods JO, Cha HJ, Wallingford JB, Marcotte EM, 2010. Systematic discovery of nonobvious human disease models through orthologous phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 6544–6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meienberg J, Bruggmann R, Oexle K, Matyas G, 2016. Clinical sequencing: is WGS the better WES? Hum. Genet 135, 359–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mighell TL, Evans-Dutson S, O’Roak BJ, 2018. A saturation mutagenesis approach to understanding PTEN lipid phosphatase activity and genotype-phenotype relationships. Am. J. Hum. Genet 102, 943–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moabbi AM, Agarwal N, El Kaderi B, Ansari A, 2012. Role for gene looping in intron-mediated enhancement of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 8505–8510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort M, Sterne-Weiler T, Li B, Ball EV, Cooper DN, Radivojac P, et al. , 2014. MutPred Splice: machine learning-based prediction of exonic variants that disrupt splicing. Genome Biol. 15, R19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto A, Orger MB, Wehman AM, Smear MC, Kay JN, Page-McCaw PS, et al. , 2005. Forward genetic analysis of visual behavior in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 1, e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry RW, Leong JT, Chow ED, Kampmann M, DeGrado WF, 2020. Deep mutational scanning reveals the structural basis for α-synuclein activity. Nat. Chem. Biol 16, 653–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S, 2001. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 11, 863–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris GA, Tsai AC-H, Schneider KW, Wu Y-H, Caulfield T, Green AL, 2021. A novel, germline, deactivating CBL variant p.L493F alters domain orientation and is associated with multiple childhood cancers. Cancer Genet 254–255, 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochenkowska K, Herold A, Samarut É, 2022. Zebrafish is a powerful tool for precision medicine approaches to neurological disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci 15, 944693. [cited 23 Aug 2022]. Available: Oral epalrestat Therapy in pediatric subjects with PMM2-CDG https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04925960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MJ, Niemi A-K, Dimmock DP, Speziale M, Nespeca M, Chau KK, et al. , 2021. Rapid sequencing-based diagnosis of thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med 384, 2159–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paes BCMF, Moço PD, Pereira CG, Porto GS, de Sousa Russo EM, Reis LCJ, et al. , 2016. Ten years of iPSC: clinical potential and advances in vitro hematopoietic differentiation. Cell Biol. Toxicol 33, 233–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey UB, Nichols CD, 2011. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev 63, 411–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Greiner DL, Shultz LD, 2008. Humanized SCID mouse models for biomedical research. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 324, 25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Gil I, Seeger T, Bruyneel AAN, Termglinchan V, Monte E, Lim EW, et al. , 2022. Serine biosynthesis as a novel therapeutic target for dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Piovesan A, Vitale L, Pelleri MC, Strippoli P, 2013. Universal tight correlation of codon bias and pool of RNA codons (codonome): the genome is optimized to allow any distribution of gene expression values in the transcriptome from bacteria to humans. Genomics 101, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovesan A, Pelleri MC, Antonaros F, Strippoli P, Caracausi M, Vitale L, 2019. On the length, weight and GC content of the human genome. BMC Res. Notes 12, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pir MS, Bilgin HI, Sayici A, Coşkun F, Torun FM, Zhao P, et al. , 2022. ConVarT: a search engine for matching human genetic variants with variants from non-human species. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1172–D1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KS, Hubisz MJ, Rosenbloom KR, Siepel A, 2010. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 20, 110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabadan Moraes G, Pasquier F, Marzac C, Deconinck E, Damanti CC, Leroy G, et al. , 2022. An inherited gain-of-function risk allele in EPOR predisposes to familial JAK2 myeloproliferative neoplasms. Br. J. Haematol 198, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray T. Mother’s negligence suit against quest’s athena could broadly impact genetic testing labs. Genomeweb [Internet]. 14 Mar 2016. [cited 23 Aug 2022]. Available: https://www.genomeweb.com/molecular-diagnostics/mothers-negligence-suit-against-quests-athena-could-broadly-impact-genetic.

- Rice GI, Park S, Gavazzi F, Adang LA, Ayuk LA, Van Eyck L, et al. , 2020. Genetic and phenotypic spectrum associated with IFIH1 gain-of-function. Hum. Mutat 41, 837–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, Kent Korgenski E, Srivastava R, Bonkowsky JL, 2015a. Costs of the diagnostic odyssey in children with inherited leukodystrophies. Neurology 85, 1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. , 2015b. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med 17, 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JE Jr., Hines S, Selvam P, Atwal H, Farres H, Caulfield TR, et al. , 2021. Clinical description & molecular modeling of novel MAX pathogenic variant causing pheochromocytoma in family, supports paternal parent-of-origin effect. Cancer Genet 252–253, 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rocco M, Galosi S, Lanza E, Tosato F, Caprini D, Folli V, et al. , 2022. Caenorhabditis elegans provides an efficient drug screening platform for GNAO1-related disorders and highlights the potential role of caffeine in controlling dyskinesia. Hum. Mol. Genet 31, 929–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rom O, Villacorta L, Zhang J, Chen YE, Aviram M, 2018. Emerging therapeutic potential of glycine in cardiometabolic diseases: dual benefits in lipid and glucose metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol 29, 428–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RG, Daley GQ, 2019. Induced pluripotent stem cells in disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Genet 20, 377–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford Kobayashi E, Waldman B, Engorn BM, Perofsky K, Allred E, Briggs B, et al. , 2021. Cost efficacy of rapid whole genome sequencing in the pediatric intensive care unit. Front Pediatr 9, 809536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SL, Hartley T, Dyment DA, Beaulieu CL, Schwartzentruber J, Smith A, et al. , 2016. Utility of whole-exome sequencing for those near the end of the diagnostic odyssey: time to address gaps in care. Clin. Genet 89, 275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield D, Rynehart L, Shresthra R, White SM, Stark Z, 2019. Long-term economic impacts of exome sequencing for suspected monogenic disorders: diagnosis, management, and reproductive outcomes. Genet. Med 21, 2586–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]