Abstract

In grass, the lemma is a unique floral organ structure that directly determines grain size and yield. Despite a great deal of research on grain enlargement caused by changes in glume cells, the importance of normal development of the glume for normal grain development has been poorly studied. In this study, we investigated a rice spikelet mutant, degenerated lemma (del), which developed florets with a slightly degenerated or rod-like lemma. More importantly, del also showed a significant reduction in grain length and width, seed setting rate, and 1000-grain weight, which led to a reduction in yield. The results indicate that the mutation of the DEL gene further affects rice grain yield. Map-based cloning shows a single-nucleotide substitution from T to A within Os01g0527600/DEL/OsRDR6, causing an amino acid mutation of Leu-34 to His-34 in the del mutant. Compared with the wild type, the expression of DEL in del was significantly reduced, which might be caused by single base substitution. In addition, the expression level of tasiR-ARF in del was lower than that of the wild type. RT-qPCR results show that the expression of some floral organ identity genes was changed, which indicates that the DEL gene regulates lemma development by modulating the expression of these genes. The present results suggest that the normal expression of DEL is necessary for the formation of lemma and the normal development of grain morphology and therefore has an important effect on the yield.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-023-01297-6.

Keywords: Lemma, Map-based cloning, Rice, Yield, Spikelet

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a model monocotyledonous plant and is one of the most important food crops in the world. Increasing rice grain yield provides the food demands and security of a rapidly growing population. The grain size and shape of rice are determined by the length, width, and thickness of the grain, which determine the overall yield and quality. Loss-of-function of OsNAC129, a member of the NAC transcription factor gene family that has its highest expression in the immature seed, greatly increased grain length, grain weight, apparent amylose content (AAC), and plant height due to increased cell length compared with wild-type plants (Jin et al. 2022). OsDDM1b T-DNA insertion loss-of-function of mutant exhibited dwarfism, smaller organ size, and shorter and wider grain size than the wild type, because the outer parenchyma cell layers of lemma in osddm1b developed more cells with decreased size (Guo et al. 2022). Mutation of FZP causes smaller grains and degenerated sterile lemmas. The small fzp-12 grains were caused by a reduction in cell number and size in the hulls (Ren et al. 2018). Hence, the size of the lemma and palea determines the length and width of the grain, thus the normal development of the glume is important for ensuring the normal development of the grain and is closely related to the yield and quality (Shomura et al. 2008; Xing and Zhang 2010).

The characteristic genes that regulate floral meristem identity maintain the normal development of the inflorescence, and activate the expression of the related floral organ identity genes to produce specialized floral organ primordia and ultimately form the complete floret. The so-called ABCDE model for the regulation of floral organ development in higher plants has been proposed (Theissen 2001). Class A genes are involved in the regulation of the lemma, three of which have been isolated in rice, namely OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS18, which all belong to the SQUA gene family and the FUL subfamily. Ectopic expression of OsMADS14 leads to an early-flowering phenotype (Jeon et al. 2000). In situ hybridization indicates that OsMADS15 is expressed in the lemma and palea; the mutant shows degeneration and albinism of the lemma, and overexpression of OsMADS15 results in early flowering (Kyozuka and Shimamoto 2002; Wang et al. 2010b). OsMADS18 is widely expressed in all tissues and overexpression resulted in early flowering and accelerated tillering of the stem meristem (Moon et al. 1999). In addition, Class E genes are involved in the regulation of the lemma. Class E genes in rice comprise OsMADS1 (LHS1), OsMADS5, OsMADS7, OsMADS8, and OsMADS34, which predominantly regulate the development of organs in the entire floret. OsMADS1 may maintain the development of the palea and lemma and the establishment of spikelet determinacy (Malcomber and Kellogg 2004).

The development of the lemma and palea is also regulated by the trans-acting small interfering RNA (ta-siRNA) synthesis pathway. In contrast to the first five types of genes, the ta-siRNA synthesis pathway predominantly regulates lemma and palea development by affecting the establishment of polarity. Ta-siRNA synthesis is controlled by three types of major proteins that all play important roles, namely the AGO protein that specifically binds to miRNA; the RDR6 and SGS3 proteins involved in dsRNA formation; and the DCL4 and DRB4 proteins performing cleavage functions (Allen et al. 2005). Previous research have shown that mutations in the ta-siRNA synthesis pathway can cause defective polarity development of the glume. SHL2 encodes a protein in rice similar to Arabidopsis RDR6, which mediates the production of dsRNA. In the shl2 mutant, the stamens and lemma are defective in adaxial–abaxial polarity development, causing the lemma to become filamentous or stick-shaped, or to fail to develop entirely (Toriba et al. 2010). Rice SHO1 and SHO2 encode proteins closely related to Arabidopsis DCL4 and AGO7, respectively. Leaf growth of the sho1 mutant is accelerated and the leaves are deformed, showing short and narrow or filamentous shapes, and lemma development is hindered by the absence of adaxial surfaces (Nagasaki et al. 2007). The sho2 mutant exhibits leaf phenotypes similar to those of sho1, but lemma development has not previously been described (Song et al. 2012).

In this study, we identified a rice DEGENERATED LEMMA (DEL) gene which encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and is highly expressed in the spikelet, especially in the lemma. The del developed florets with a slightly degenerated or rod-like lemma, which then forms a dropping-like seed or empty grain. Analysis of agronomic traits shows that grain length and width, seed setting rate, and 1000-grain weight of the del mutant were reduced significantly compared with the wild type. This suggests that the mutation of DEL further affected rice grain yield. Compared with the wild type, the expression of DEL in del was significantly reduced. In addition, the expression level of tasiR-ARF in del was lower than that of the wild type. RT-qPCR results show that the expression of some floral organ identity genes was changed, which indicates that the DEL gene regulates lemma development by modulating the expression of these genes. Taken together, these results suggest that the normal expression of DEL is necessary for the formation of lemma and the normal development of grain morphology and therefore has an important effect on the yield.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The del mutant was derived from the progeny of a rice indica restorer line, O. sativa subsp. indica cultivar ‘Xinong 1B’, treated with ethyl methane sulfonate-mutagenized (EMS) and was stably inherited through seven successive generations of self-crossing. The F1 progeny was generated by the cross of indica sterile line 56S with del. All the plant materials used were planted in the experimental fields under natural conditions at the Rice Research Institute of Southwest University in Chongqing, China (30° 05′ 08″ N, 106° 18′ 02″ E, latitude of 321 m) and the local climate is subtropical monsoon humid climate. During the experimental period, the air temperature ranged from 12 to 38°C, and the air relative humidity from 13 to 80%. The plants with mutant phenotype in F2 progeny were used to map the DEL gene.

Morphological and histological analysis

At the flowering stage, living plants were collected from the field and moved to the scanning electron microscope room. Removed the leaves that enclose the young inflorescences. Then the spikelets were moved to the carrier table of the scanning electron microscope (Hitachi SU3500, Tokyo, Japan), and observed and photographed under low vacuum mode, 5 kV accelerating voltage, and freezing conditions at − 20°C.

Panicles of the wild type and the del mutant were collected at the heading stage and fixed in FAA solution (50% ethanol, 0.9 M glacial acetic acid, and 3.7% formaldehyde) overnight at 4°C. The fixed spikelets were dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions, infiltrated in xylene, and embedded in paraffin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Samples were sectioned at 8 μm and transferred onto poly-L-lysine–coated glass slides, deparaffinized with xylene, and dehydrated through a series of ethanol solutions. The sections were stained sequentially with 1% safranin (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) and 1% Fast Green (Amresco), and observed using an Eclipse E600 light microscope (Nikon).

Molecular mapping of del and linkage map construction

To localize the target gene, the bulk segregant analysis method was used (Michelmore et al. 1991). The DNA was extracted by etyltrime thylammonium bromide method (Murray and Thompson 1980) to locate the target gene. The InDel markers used for gene mapping were distributed equally among the 12 chromosomes. All primers were synthesized by the Beijing Tsingke Company. The total volume of PCR amplification was 13 µL, comprising 1.25 µL 10 × PCR buffer, 1 µL of 50 ng µL−1 DNA, 8.5 µL ddH2O, 1 µL of 10 mmol L−1 forward and reverse primers, 0.5 µL of 2.5 mmol L−1 dNTPs, and 0.1 µL of 5 U µL−1 rTaq DNA polymerase. DNA amplification was achieved by the following procedure: 5 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated in 10% polyacrylamide gel and visualized after rapid silver staining (Luo et al. 2007). The relative distances between the del locus and the InDel markers were marked by the number of recombinants. The primers are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Candidate genes analysis

Information on gene annotations was obtained from the Gramene (http://www.gramene.org/) and Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/) online data resources. Homology analysis was conducted using the BLAST tool on the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Complementation test

The Os01g0527600 sequence, a 7034-bp genomic fragment that contained the DEL coding sequence, coupling the 2144-bp upstream, was downloaded from the gramene database (http://www.gramene.org/microsat), and the forward primer DELcom-F and reverse primer DELcom-R were designed by bioengineering software Vector NTI Advance 10 (InforMax, Frederick). DNA extracted from the wild type was used as the template for PCR amplification and the PCR product was purified by a gel extraction kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, BEIJING). The pCAMBIA1301 original bacterial solution of the complementary vector was used for shaking replication, and the plasmid was extracted and digested by Kpn I and Xba I restriction endonuclease. Recombinant enzymes were used for ligating and transformation, and the positive strains detected by PCR were selected and sent to the Chongqing TSINGKE company for sequencing. The constructed pCAMBIA1301-DELp-DEL-GUS fusion expression vector was transformed into del mutants by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method. The recombinant vector was transformed into Agrobacterium Tumefaciens, which was co-cultured with del callus, and then the positive plants were screened. The transformation and differentiation processes were completed by the Wuhan Boyuan Company. The primer sequences used are shown in Supplemental Table 5.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

RNAprep Pure Plant RNA Purification Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) was used to isolate the total RNA from lemma, rod-like lemma, palea, pistil, and stamen of the wild type and the del mutant plant. The extraction process followed the kit instructions and kept RNase free environment throughout the whole process. The purity and concentration of RNA were determined by NanoDrop™ One/OneC (Thermo) and RNA integrity was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis. 2 µg of purified RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript® Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa). DNase treatment was given prior to cDNA preparation. Half a microliter of the reverse-transcribed RNA was used as a PCR template with gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table 4). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) with the CFX Connect™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). The total volume was 20 µL, comprising 10 µL SYBR premix Ex Taq II, 2 µL of 10 µmol L−1 forward and reverse primers, 0.4 µL of ROX Reference Dye II, 2 µL template, and 5.6 µL ddH2O. DNA amplification was achieved by the following procedure: 30 s at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C, with a final extension at 95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 1 min. ACTIN (LOC_Os03g50885) and U6 were used as the internal reference genes (Supplemental Table 4). The complete reaction conditions followed the kit instructions. The average expression level was calculated for each gene. All samples were obtained from fresh plants in the field, stored in liquid nitrogen, and transported to the laboratory. Residual RNA samples were stored at − 80°C and cDNA at − 20°C. A minimum of three replicates were analyzed to produce the mean values of the expression levels of each gene.

In situ hybridization

Young panicles from the wild type were fixed in 70% FAA (RNase free), then dehydrated through a series of alcohols/xylene treatments, before being embedded in paraffin (Sigma-Aldrich). For the DEL probe, gene-specific cDNA was amplified and labeled using the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Zhang et al. 2017). Hybridization conditions for the probe were carried out at 52°C overnight; then the slides were washed four times at 50°C. The primers are shown in Supplemental Table 5.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data for gene expression and statistical data were examined for statistically significant differences using a one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) test as described in the corresponding figure legends. One-way ANOVA tests were performed using Excel (2021).

Protein structure prediction

The protein sequences of wild type and del were inputted into PSIPRED website (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/) to predict their secondary structure. At the mutation site, both wild type and del were β-strand structure. The tertiary structure of wild-type protein was found in uniprot database (https://www.uniprot.org/) with ID Q8LHH9. Alphafold 2 (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2.ipynb) was used to predict the tertiary structure of mutants online. The structure comparison tool in SWISS-MODEL website (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) was used to compare the tertiary structure of wild type and del, and it was found that the overall spatial structure and the spatial structure of mutation sites had no significant changes.

Results

Morphological and histological analysis of the del mutant at the flowering stage

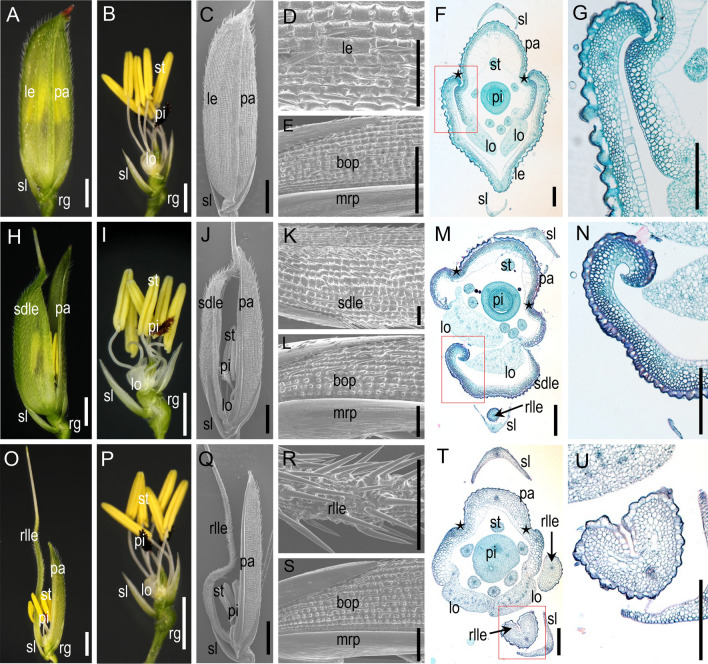

The spikelet of the wild type contains one terminal fertile floret, one pair of sterile lemmas, and one pair of rudimentary glumes in rice (Fig. 1A). The terminal fertile floret is bisexual and consists of one pistil and six stamens, as well as two lodicules and one pair of bract-like organs (lemma and palea) (Fig. 1B and C). There are five and three vascular bundles in the lemma and palea, respectively. In addition, the lemma is composed of four cell layers: from the abaxial to the adaxial surface these are a silicified upper epidermis, sclerenchyma cells, parenchyma cells, and a vacuolated inner epidermis, and the palea is composed of two fused parts: the body of the palea (bop) and two marginal regions of the palea (mrp) (Fig. 1D and E). The cellular structure of the bop is similar to that of the lemma, but the mrp displays a distinctive smooth epidermis. The lemma and palea are hooked together to protect the inner floral organs and grain (Fig. 1F and G).

Fig. 1.

Phenotype of spikelets of the wild type and the del mutant. A Complete spikelet of the wild type. B The spikelet shown in A with the lemma and palea removed. C Surface of wild-type spikelet. D Surface features of the lemma. E Surface features of the palea. F Transverse sections of a wild-type spikelet. G High-magnification image of the area in the red box in F. H A del mutant spikelet with a slightly degenerated lemma. I The spikelet shown in H with the lemma and palea removed. J Surface of the slightly degenerated lemma with the inner floral organs exposed. K Surface features of the slightly degenerated lemma. L Surface features of the palea. M Transverse sections of a del mutant spikelet. N High-magnification image of the area in the red box in M. O A del mutant spikelet with a rod-like lemma. P The spikelet shown in O with the lemma and palea removed. Q, The surface of the rod-like lemma with the inner floral organs exposed. R Surface features of the rod-like lemma. S, Surface features of the palea. T Transverse sections of a del mutant spikelet. U High-magnification image of the area in the red box in T. Black stars indicate the joining of the lemma and palea. le, lemma; pa, palea; sl, sterile lemma; rg, rudimentary glume; st, stamen; pi, pistil; lo, lodicule; sdle, slightly degenerated lemma organ; rlle, rod-like lemma organ; bop, body of the palea; mrp, margin of the palea. Bars = 1 cm in A–C, H–J, and O–Q; 2 mm in D, E, G, K, L, N, R, S, and U; 500 μm in F, M, and T

In comparison with the wild type, in the del mutant 36% of spikelets developed a slightly degenerated lemma (Fig. 1H–N), which was narrow and unable to hook with the palea, causing a cracked floret (Fig. 1H and J). Interestingly, the palea and inner floral organs developed normally (Fig. 1I, K, and L). Inspection of paraffin sections revealed that the four-layer cell structure of the lemma persisted, but the number and volume of the cells were significantly lower in the mutant (Fig. 1M and N). In 53% of spikelets, a rod-like lemma formed (Fig. 1O and T), and in these spikelets, the lemma was extremely degenerated and transformed into an awn-like organ (Fig. 1O, Q, and R). The morphology of the lemma was highly similar to that of the awn and contained only one midvein. The silicified cells that should have been present on the outside surface of the wild type were ectopic and found in the inner epidermis of the rod-like lemma. The internal cell structure was almost completely disordered and unrecognizable (Fig. 1T and U). The palea and inner floral organs in the mutant were normal (Fig. 1P, S, and T). Taken together, del showed degeneration of the lemma to differing degrees, which suggests that DEL plays an important role in the lemma development.

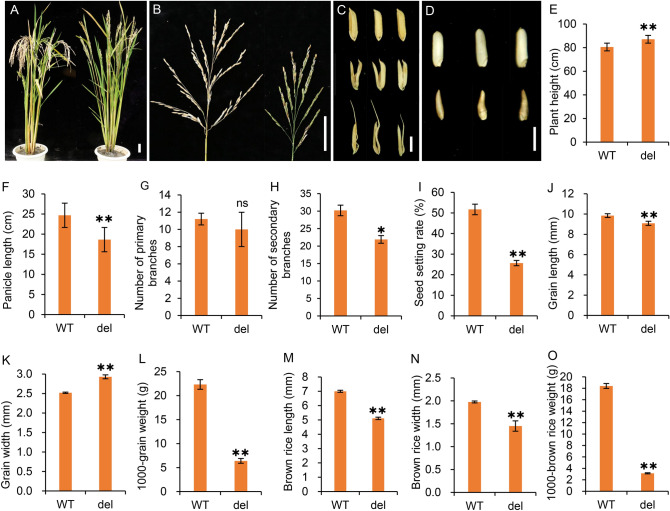

The del mutant affects grain yield

The spike type of the del mutant was more erect and smaller than that of the wild type. Compared with the wild type, the plant height of the del mutant was increased by 6.55 cm (Fig. 2A, E), while the panicle length was reduced by 24.5% (Fig. 2B, F). While the number of primary branches of del showed no significant difference, the number of secondary branches was reduced by 10.7% (Fig. 2G and H). The rate of seed setting in del was reduced by 70% (Fig. 2I). As well as impaired flower development, the mature grains of del were also affected. The glumes of the mature grains in del were still dehiscent, and the lemma was rod-like in the severe mutant (Fig. 2C). The mature brown rice grains were shaped like water droplets, being narrow at the top and wide at the bottom, and the rod-like spikelets produced few grains (Fig. 2D). The grain length and the brown-rice grain length of the del were reduced by 7.7% and 27.0%, respectively (Fig. 2J and M). The grain width of the del was increased by 16.3%, but the brown-rice grain width of the del was reduced by 26.8% (Fig. 2K and N). The 1000-grain weight and the 1000-grain brown-rice weight were also reduced by 71.3% and 83.0%, respectively (Fig. 2L and O). The results reveal that the DEL gene plays an important role in spikelet development and affects rice grain yield.

Fig. 2.

Investigation of yield-related agronomic traits in the wild type and del mutant. A Plant type of the wild type (left) and del mutant (right). B Main panicle of the wild type (left) and del mutant (right). C Mature grains of the wild type (upper), slightly degenerated del mutant (middle) and rod-like del mutant (lower). D Brown rice of the wild type (upper) and slightly degenerated del mutant (lower). E–I Plant height (E), panicle length (F), number of primary branches (G), number of secondary branches (H), and seed setting rate (I). J–L, length (J), width (K), and 1000-grain weight (L) of mature grains in the wild type and del mutant. M–O, length (M), width (N), and 1000-grain weight (O) of brown rice in the wild type and del mutant. Values are mean ± SD (n = 10). P value is determined using a t-test compared with 1B. * represents P < 0.05, ** represents P < 0.01, and ns represents no significance. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Bar = 5 cm in A and B, 4 mm in C and D

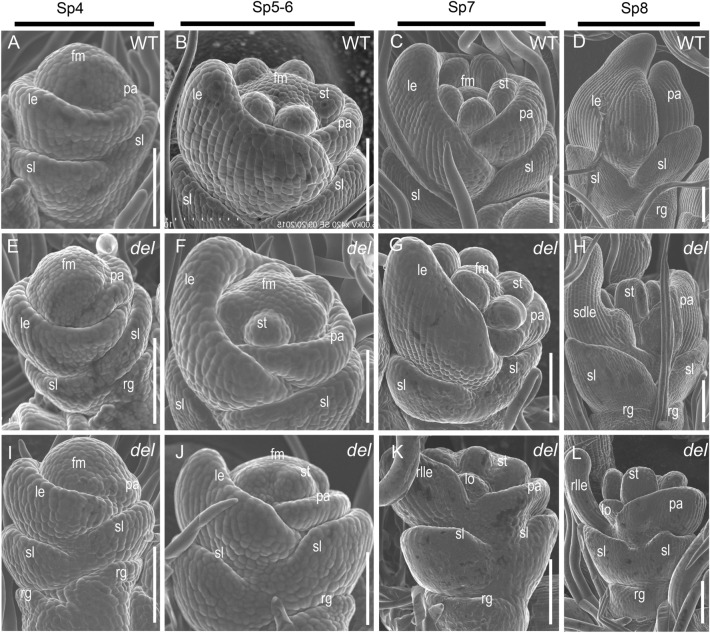

Early morphological analysis of the del mutant

Using scanning electron microscopy, we examined spikelets of the wild type and del mutant during the early developmental stages. At the spikelet 4 stage (Sp4), the primordia of the lemma and palea began to develop in the wild-type floret (Fig. 3A). In the del mutant, no significant difference was observed at Sp4 compared with the wild type (Fig. 3A, E, and I). During the Sp5 and Sp6 stages, the lemma and palea primordia were formed and the palea was smaller than the lemma, the five spherical stamen primordia were formed synchronously except for the primordium nearest the lemma in the wild-type floret (Fig. 3B). In the del mutant, which was different from the wild type, the shape of the slightly degenerated lemma was normal (Fig. 3F), and the margin of the rod-like lemma was not developed and did not intersect with the palea primordium (Fig. 3J). During the Sp7 stage, the pistil primordium was initiated and the lemma and palea primordia were normally developed and semi-closed, enclosing the inner whorl organ primordia in the wild-type floret (Fig. 3C). In the del mutant, the slightly degenerated lemma primordium was noticeably shorter and narrower than the lemma primordium in the wild type (Fig. 3G), cell differentiation on each side of the rod-like lemma was slow, and development into a rod-like structure occurred gradually (Fig. 3K). During the Sp8 stage, the single floret of the wild-type spikelet underwent a further stage of development (Fig. 3D). In the del mutant, the slightly degenerated lemma was significantly narrowed, and the palea and lemma were unable to close to cover the inner floral organs (Fig. 3H). The rod-like lemma primordium was further elongated, but the flanks remained undeveloped, and the inner floral organs were completely bare. However, the inner floral organs were normal (Fig. 3L). Collectively, these observations reveal that the defects of the lemma in the del mutant arose during the early stages of spikelet development.

Fig. 3.

Spikelet phenotypes of the wild type and the del mutant. A–D Spikelet of the wild type. E–H the slightly degenerated spikelet of the del. I–L the spikelet phenotypes of the rod-like lemma of the del. A, E, and I, Sp4; B, F, and J, Sp5-Sp6; C, G, and K, Sp7; D, H and L, Sp8. le, lemma; pa, palea; fm, floral meristem; st, stamen; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma; lo, lodicule; sdle, slightly degenerated lemma organ; rlle, rod-like lemma organ. Bars = 1 mm

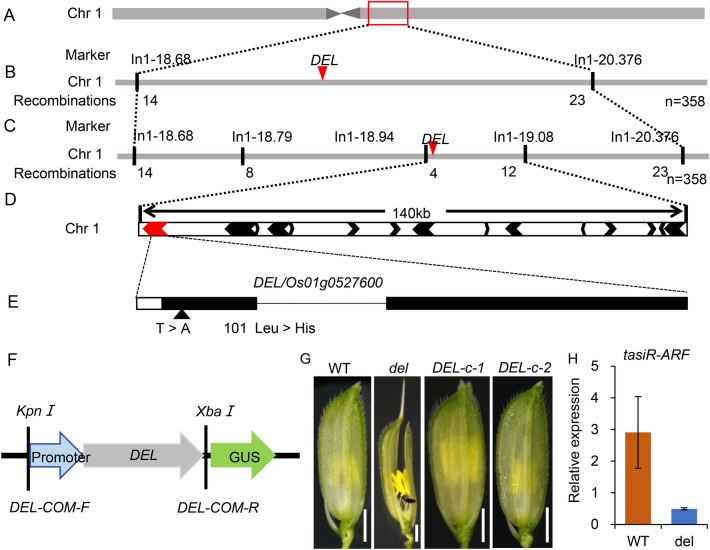

Map-based cloning of DEL

The F1 progeny was derived from the cross between 56S and the del mutant and showed a wild-type phenotype. The segregation ratio of the normal to the mutant phenotype was 3:1 (1091 wild-type-like plants and 358 mutant-like plants; χ2 = 0.26 < χ20.05,1 = 3.84) in the F2 population. This result indicates that the del mutant phenotype was controlled by a single recessive gene.

A map-based cloning approach was used to fine-map the DEL gene. The 358 recessive individuals in the F2 population were used as a mapping population to localize the DEL gene. To screen for polymorphism between the parents, a total of 420 pairs of simple sequence repeat (SSR) and InDel primers evenly distributed in the rice genome were used (Supplemental Table 1). Ninety InDel markers were selected and used to further screen two DNA pools prepared by mixing equal amounts of genomic DNA from either 10 wild-type-like F2 plants or 10 mutant-like F2 plants (Supplemental Table 2). The DEL gene was localized between the InDel markers In1-18.68 and In1-20.376 on chromosome 1 (Fig. 4A and B). To fine-map DEL, 30 pairs of InDel primers located between In1-18.68 and In1-20.376 were developed, of which In1-18.68, In1-18.79, In1-18.94, In1-19.08, and In1-20.38 exhibited polymorphism between the parents (Supplemental Table 3). Among all the F2 individuals, these five markers detected separately 14, 8, 4, 12, and 23 recombinants (Fig. 4C). These results show that DEL was located between the InDel markers of In1-18.94 and In1-19.08. The estimated physical distance between In1-18.94 and In1-19.08 was approximately 140 kb, and 15 annotated genes (RAPdb annotation) were included within this interval: four enzymes (Os01g0527600/ BAS72488, Os01g0527700/ BAS72489, Os01g0528800/ BAS72494, Os01g0529800/ BAS72498), five expressed protein (Os01g0528300/ BAS72492, Os01g0528700/ BAS72493, Os01g0529700/ BAS72497, Os01g0530100/ BAS72500, Os01g0530200/ BAS72501), a transcription factor (Os01g0528000/ BAS72491), two transposon protein (Os01g0527900/ BAS72490, Os01g0529400/ BAS72496), a non-protein-coding transcript (Os01g0527801/ Without accession number), a hypothetical protein (Os01g0530000/ BAS72499), and a gene with no annotated information (Os01g0529101/ BAS72495) (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Table 6).

Fig. 4.

Localization of DEL and candidate gene analysis. A and B Primary mapping of DEL on chromosome 1 based on 358 individuals. C DEL was fine-mapped to an interval of 140 kb using 358 individuals. D Fifteen genes were annotated in the 140 kb region. E A single-nucleotide substitution from T to A was detected in Os01g0527600.Mutation site of Os01g0527600 was between the del mutant and the wild type ‘Xinong 1B’. F Schematic structure of the complementation vector pCAMBIA1301-DEL-GFP. G The spikelets of WT, del, and the complementary transgenic line. H RT-qPCR of tasiR-ARF in spikelets of the wild type and del. U6 was used as an internal control. Data are Mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). Bars = 2 mm

Sequencing analysis showed that Os01g0527600 had a single-nucleotide substitution from T to A. The substitution of the nucleotide substitution in the del mutant caused the amino acid mutation of Leu-34 to His-34. To confirm that the mutation of Os01g0527600 caused the del mutant phenotypes, we cloned a fragment consisting of a 2144-bp upstream sequence from the start codon and 4890-bp coding region sequence of the Os01g0527600 gene in the wild type into the pCAMBIA1301 vector with the green fluorescent protein (GUS). The recombinant plasmid was then introduced into the del mutant (Fig. 4F). Subsequently, a total of 13 complementary transgenic lines were obtained, and GUS staining showed that 7 lines of them appeared indigo blue. This indicated that these lines had correctly transformed and successfully transferred into exogenous target vectors. All the T0 positive plants were planted in the fields, and the spikelet phenotype of these 7 lines was restored to the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 4G). These results confirm that the Os01g0527600 gene is the DEL gene, and the phenotype of del is indeed caused by mutation of the Os01g0527600 gene. As predicted by the bioinformatics website (https://ensembl.gramene.org/Oryza_sativa/Gene/), we found that Os01g0527600 encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 protein involved in regulating the synthesis of tasiR-ARF (Peragine et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2010a). Therefore, RT-qPCR was used to detect the expression levels of tasiR-ARF in the wild type and del. The results showed that the expression of tasiR-ARF in del was less than that of the wild type (Fig. 4H). This suggests that the DEL mutation does affect the synthesis of tasiR-ARF.

To study the relationship between the del mutant phenotype and the single-nucleotide substitution from T to A, we performed RT-qPCR to measure the expression of DEL in the spikelet of WT and del. The results showed that compared with WT, the expression of DEL in del was significantly reduced (Fig. 5G). As the substitution of the nucleotide substitution in the del mutant caused the mutation of hydrophobic amino acid Leu-34 to hydrophilic amino acid His-34, and hydrophobic interactions are the main driving force of protein folding and play a role in maintaining the tertiary structure of proteins (Perunov and England 2014). Therefore, we performed secondary and tertiary structural analysis of DEL protein in WT and del, respectively, and the results showed that the overall spatial structure of wild type and del and the spatial structure of mutation sites did not change (Supplemental Figure). Taken together, the above results suggest that the phenotype of del spikelets with developmental defects may be due to the decreased transcription level of DEL rather than the alteration of the higher structure of its protein.

Fig. 5.

Spatiotemporal expression pattern of the DEL gene. A and B RT-qPCR of DEL. Young panicles < 0.5 cm, 0.5–1.0 cm, 1.0–2.0 cm, vegetative organ, and floral organ of the wild type were used. C–F Expression pattern of DEL in spikelets of the wild type. In situ hybridization in the spikelets of the wild type during stages Sp4 (C), Sp5-6 (D), Sp7-8 (E), and glume (F). G RT-qPCR of DEL/OsRDR6 in spikelets of wild type and del. ACTIN (LOC_Os03g50885) was used as an internal control. Data are Mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). fm, floral meristem; le, lemma; pa, palea; st, stamen; pi, pistil; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma. The black arrows indicate the vascular bundles. Bars = 100 μm

Spatiotemporal expression pattern of DEL

To clarify the functions of the DEL gene, we used RT-qPCR and in situ hybridization to test for DEL expression in the wild type. RT-qPCR analysis showed that DEL was constitutively expressed in whole organs, including root, stem, blade, sheath, and panicles in wild-type plant. The lowest expression was found in the stem, and the highest expression was found in the blade. The expression level in the sheath was slightly higher than that of the stem, and the expression levels of the root and panicle were similar in wild-type plant (Fig. 5A). In the spikelet, DEL was expressed in the lemma, palea, pistil, stamen, and lodicule (Fig. 5B). Later, in situ hybridization was used to detect the expression pattern of DEL, and a strong signal was shown in the rice spikelet (Fig. 5C–F). At the Sp3 stage, the DEL gene was highly expressed in the rudimentary glume, the sterile lemma, and the floral meristem (Fig. 5C). At the Sp5-6 stage, a strong DEL signal was detected in the lemma and palea primordia, and floral meristem (Fig. 5D). At Sp7-Sp8, DEL was expressed in the lemma, palea, stamen, pistil, and lodicule (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that DEL was mainly expressed in the spikelet and florets, and was highly expressed throughout plant growth, which implies its role in regulating the development of the lemma. Because del showed a phenotype of lemma degeneration to differing degrees, we also explored the expression of DEL in the wild-type glume. The results showed that DEL was highly expressed in the whole of the lemma and palea, especially in their eight vascular bundles (Fig. 5F).

Expression analysis of floral organ identity genes in the del mutant and wild type

To determine the identity of the floral organs in the del mutant, we used quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis to investigate the expression patterns of known genes associated with floral organ identity. DROOPING LEAF (DL) is a lemma identity gene. DL was expressed predominantly in the lemma of the wild type and the slightly degenerated lemma of the del mutant, but a weak expression signal was detected in the rod-like lemma of the del mutant (Fig. 6A). OsMADS1, OsMADS14, and OsMADS15 are lemma and palea identity genes. In the lemma and palea of the wild type, and in the slightly degenerated lemma, rod-like lemma, and palea of the del mutant, strong signals for OsMADS1, OsMADS14, and OsMADS15 were detected (Fig. 6B–D). These results suggest that the slightly degenerated lemma retained the identity of the lemma, and degeneration of the rod-like lemma in the del mutant may be caused by reduced expression of DL. OsMADS6, which is an mrp identity gene, was expressed in the palea of the wild type and del mutant, which indicates that the palea identity in the del mutant was normal (Fig. 6E). We also detected transcripts of OsMADS2, OsMADS3, and OsMADS4, all of which regulate the development of the stamens and pistil. Each gene was expressed significantly in the stamens and pistil of both the wild type and del mutant, which indicates that the stamens and pistil of the del mutant showed normal identities (Fig. 6F–H). Collectively, these results indicate that the del mutation played a critical role in the regulation of DL for lemma identity.

Fig. 6.

Relative expression levels of floral organ identity genes in floral organs of the wild type and del mutant. le, lemma; pa, palea; sdle, slightly degenerated lemma organ; rlle, rod-like lemma organ; st, stamen; pi, pistil. ACTIN (LOC_Os03g50885) was used as an internal control. Data are Mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates)

Discussion

In our study, we identified a del mutant, which contains a mutant allele of OsRDR6, to gain a better understanding of the functions of OsRDR6. The del mutant had the same phenotypes as the reported osrdr6 mutants, such as cracked glumes, caused by the different degrees of degradation of the lemma (needle/rod/awn-like structure) (Song et al. 2012; Toriba et al. 2010). Moreover, the del mutant also exhibited an altered grain size. We suggest that the different backgrounds and mutation sites of the del mutant and the osrdr6 mutants could result in additional phenotypes. SHL2 encodes OsRDR6, eight shl2 alleles (shl2-1 through shl2-8) from O. sativa cultivar Taichung 65 have been identified, and most alleles have a nonsense mutation, frameshift mutation, or amino acid substitution in the conserved RdRP domain. The shl2 mutants reported to date are embryonic or seedling-lethal, caused by a failure in the formation of the SAM in the embryo (Toriba et al. 2010). For the osrdr6-1 mutant from japonica cultivar Zhonghua11, a single nucleotide transition from G to T in osrdr6-1 led to the substitution of a highly conserved tryptophan to cysteine (Song et al. 2012). Most spikelets in osrdr6-1 showed needle-shaped, awn-like lemma and altered stamen number. The shl2-rol mutant from the japonica cultivar Nipponbare had an amino acid substitution in the N-terminal region far from the RdRP domain. In the shl2-rol spikelets, morphological defects were observed in the lemma (needle-like structure), palea, and stamen, resulting in a lack of organs or a reduction in their number. By comparison, we considered the del from the indica restorer line, Xinong 1B (a local variety of Chongqing). Substitution of the nucleotide in the del mutant caused amino acid mutation of hydrophobic amino acid Leu-34 to hydrophilic amino acid His-34 in the N-terminal region far from the RdRP domain. Hydrophobic interactions are the main driving force of protein folding and play a role in maintaining the tertiary structure of proteins (Perunov and England 2014). Therefore, we performed secondary and tertiary structural analysis of OsRDR6 protein in WT and del, respectively, and the results showed that the higher structures of both were similar (Supplemental Figure). The mutation of del was less severe than that of shl2-rol and osrdr6-1, only producing a rod-like lemma mutant, whereas abnormal phenotypes were observed in both shl2-rol and osrdr6-1 in lemma and inner whorl organs (Toriba et al. 2010). This may be because the mutation site of del is not in the conserved RdRP domain. The mutation sites of shl2-rol and osrdr6-1 are in the RdRP domain. Combined with the above results, we speculated that the mutant phenotype of del was due to the decreased transcription level of DEL rather than the alteration of the higher structure of its protein.

Improved grain yield is an important goal for basic and applied scientific research in plants (Ren et al. 2019). Normal development of floral organs, specifically the glumes (i.e., lemma and palea) is the basis for ensuring the normal development of the grain and is also closely related to the yield (Ren et al. 2019; Shomura et al. 2008; Xing and Zhang 2010). Grain size is also an important factor in determining rice yield. Significantly, previous studies of OsRDR6 focused on the development of flower organs, especially lemmas. The phenotype of the del showed that some florets were able to form seeds without the presence of a lemma or palea, and these seeds were dropping-like and smaller than those of the wild type. In our study, compared with the wild type, the grain length and the brown-rice grain length of the del were reduced by 7.7% and 27.0%, respectively. The grain width in the del mutant was increased by 16.3%, but the brown-rice grain width of the del was reduced by 26.8%. The 1000-grain weight and the 1000-grain brown rice weight were also reduced by 71.3% and 83.0%, respectively. The reduced grain or brown-rice grain length and width in del may be due to the degenerated lemma, which provides photosynthetic products for the floral organs in the early stages of development, to protect the grain from attack by diseases and insects after maturity, and determines the length and width of the grain. Taken together, the normal function of the DEL gene is the basis for the normal development of lemma morphology and size, and has an important influence on rice grain yield. DEL is thus a possible target for efforts to improve rice grain yield.

The lemma and palea are specialized floral organs that are unique to grasses. The development of the lemma has been an important focus of research on floral organ development in rice. In previous research, LHS1 (OsMADS1) was shown to regulate the formation and development of the lemma, predominantly by controlling the differentiation of specific cells of the lemma (Jeon et al. 2000). The complete loss-of-function of OsMADS1 results in a homologous transformation of the three internal whorls of floral organs (lodicules, stamens, and pistil) into a lemma and palea-like structure (Agrawal et al. 2005; Jeon et al. 2000). The DL gene is a member of the YABBY family. The phenotype of the dl-sup6 mutant differs from that of other mutants in that a DNA fragment is inserted into the second intron of DL, resulting in a loss of expression of DL and a change in the number of vascular bundles of the lemma (Ohmori et al. 2011). Compared with the aforementioned mutants, the del mutant displayed a lemma degenerated to different degrees, including a rod-like lemma, and the surface of the lemma is similar to that of the awn. However, the palea and inner floral organs are normally developed. DEL is the allele of OsRDR6, which encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and is essential for ta-siRNA synthesis in rice. Genes associated with the ta-siRNA pathway are likely to be involved in the establishment of adaxial–abaxial polarity. Rice SHO1 and SHO2 encode proteins closely related to Arabidopsis DCL4 and AGO7, respectively. Leaf growth of the sho1 mutant is accelerated and the leaves are deformed, showing short and narrow or filamentous shapes, and lemma development is hindered by the absence of adaxial surfaces (Nagasaki et al. 2007). The sho2 mutant exhibits leaf phenotypes similar to those of sho1 (Song et al. 2012). OsDCL4 is responsible for the formation of the 21-nucleotide-long siRNA. In the osdcl4-1 mutant, the lemma shows degeneration and widespread conversion to an awn (Liu et al. 2007). Similar to the above mutations in the ta-siRNA synthesis pathway, the lemma of the del mutant was also degenerated to varying degrees, being partially or completely degenerated to the awn. In addition, RT-qPCR was used to detect the expression levels of tasiR-ARF in the wild type and del, and it has been reported that RDR6 is necessary for the synthesis of tasiR-ARF (Peragine et al. 2004). The results showed that the expression of tasiR-ARF in del was less than that of the wild type, which suggests that the DEL mutation does affect the synthesis of tasiR-ARF. Therefore, the function of the ta-siRNA synthesis pathway is conserved, in regulating lemma and palea development by affecting the establishment of polarity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900612, 31730063 and 31971919). Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (Grant No. cstc2021jcyj-bshX0076).

Data availability

All available data has been presented.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally to this work: You Jing and Chen Wenbo.

References

- Agrawal G, Abe K, Yamazaki M, Miyao A, Hirochika H. Conservation of the E-function for floral organ identity in rice revealed by the analysis of tissue culture-induced loss-of-function mutants of the OsMADS1 gene. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;59:125–135. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2161-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Zhang W, Mohammadi MA, He Z, She Z, Yan M, Shi C, Lin L, Wang A, Liu J, Tian D, Zhao H and Qin Y (2022) OsDDM1b controls grain size by influencing cell cycling and regulating homeostasis and signaling of brassinosteroid in rice. 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jeon JS, Jang S, Lee S, Nam J, Kim C, Lee SH, Chung YY, Kim SR, Lee YH, Cho YG, An G. leafy hull sterile1 is a homeotic mutation in a rice MADS box gene affecting rice flower development. Plant Cell. 2000;12:871–884. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.6.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S-K, Zhang M-Q, Leng Y-J, Xu L-N, Jia S-W, Wang S-L, Song T, Wang R-A, Yang Q-Q, Tao T, Cai X-L and Gao J-P (2022) OsNAC129 regulates seed development and plant growth and participates in the brassinosteroid signaling pathway. 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kyozuka J, Shimamoto K. Ectopic expression of OsMADS3, a rice ortholog of AGAMOUS, caused a homeotic transformation of lodicules to stamens in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:130–135. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Chen ZY, Song XW, Liu CY, Cui X, Zhao XF, Fang J, Xu WY, Zhang HY, Wang XJ, Chu CC, Deng XW, Xue YB, Cao XF. Oryza sativa dicer-like4 reveals a key role for small interfering RNA silencing in plant development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2705–2718. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZK, Yang ZL, Zhong BQ, Li YF, Xie R, Zhao FM, Ling YH, He GH. Genetic analysis and fine mapping of a dynamic rolled leaf gene, RL10(t), in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genome. 2007;50:811–817. doi: 10.1139/G07-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcomber ST, Kellogg EA. Heterogeneous expression patterns and separate roles of the SEPALLATA gene LEAFY HULL STERILE1 in Grasses. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1692–1706. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore RW, Paran I, Kesseli RV. Identification of markers linked to disease-resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis—a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9828–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YH, Kang HG, Jung JY, Jeon JS, Sung SK, An G. Determination of the motif responsible for interaction between the rice APETALA1/AGAMOUS-LIKE9 family proteins using a yeast two-hybrid system. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:1193–1203. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid Isolation of High molecular-weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki H, Itoh JI, Hayashi K, Hibara KI, Satoh-Nagasawa N, Nosaka M, Mukouhata M, Ashikari M, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Nagato Y, Sato Y. The small interfering RNA production pathway is required for shoot meristern initiation in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14867–14871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704339104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori Y, Toriba T, Nakamura H, Ichikawa H, Hirano HY. Temporal and spatial regulation of DROOPING LEAF gene expression that promotes midrib formation in rice. Plant J. 2011;65:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS. SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2368–2379. doi: 10.1101/gad.1231804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perunov N, England JL. Quantitative theory of hydrophobic effect as a driving force of protein structure. Protein Science : a Publication of the Protein Society. 2014;23:387–399. doi: 10.1002/pro.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Hu J, Xu Q, Cui Y, Zhang Y, Zhou T, Rao Y, Xue D, Zeng D, Zhang G, Gao Z, Zhu L, Shen L, Chen G, Guo L, Qian Q. FZP determines grain size and sterile lemma fate in rice. J Exp Bot. 2018;69:4853–4866. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Cui Y, Hu H, Xu Q, Rao Y, Yu X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Peng Y, Zeng D, Hu J, Zhang G, Gao Z, Zhu L, Chen G, shen L, Zhang Q, Guo L and Qian Q, AH2 encodes a MYB domain protein that determines hull fate and affects grain yield and quality in rice. Plant J. 2019;100:813–824. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomura A, Izawa T, Ebana K, Ebitani T, Kanegae H, Konishi S, Yano M. Deletion in a gene associated with grain size increased yields during rice domestication. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ng.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wang D, Ma L, Chen Z, Li P, Cui X, Liu C, Cao S, Chu C, Tao Y, Cao X. Rice RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 acts in small RNA biogenesis and spikelet development. Plant J Cell Molecular Biology. 2012;71:378–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theissen G. Development of floral organ identity: stories from the MADS house. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:75–85. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toriba T, Suzaki T, Yamaguchi T, Ohmori Y, Tsukaya H, Hirano H-Y. Distinct regulation of Adaxial–Abaxial polarity in anther patterning in rice. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1452–1462. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Gao X, Li L, Shi X, Zhang J, Shi Z. Overexpression of Osta-siR2141 caused abnormal polarity establishment and retarded growth in rice. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:1885–1895. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KJ, Tang D, Hong LL, Xu WY, Huang J, Li M, Gu MH, Xue YB, Cheng ZK. DEP and AFO regulate reproductive habit in rice. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Zhang Q. Genetic and molecular bases of rice yield. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:421–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Li Y, Ma L, Sang X, Ling Y, Wang Y, Yu P, Zhuang H, Huang J, Wang N, Zhao F, Zhang C, Yang Z, Fang L, He G. LATERAL FLORET 1 induced the three-florets spikelet in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:201700504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700504114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All available data has been presented.