Abstract

Methcathinone (MCAT) belongs to the designer drugs called synthetic cathinones, which are abused worldwide for recreational purposes. It has strong stimulant effects, including enhanced euphoria, sensation, alertness, and empathy. However, little is known about how MCAT modulates neuronal activity in vivo. Here, we evaluated the effect of MCAT on neuronal activity with a series of functional approaches. C-Fos immunostaining showed that MCAT increased the number of activated neurons by 6-fold, especially in sensory and motor cortices, striatum, and midbrain motor nuclei. In vivo single-unit recording and two-photon Ca2+ imaging revealed that a large proportion of neurons increased spiking activity upon MCAT administration. Notably, MCAT induced a strong de-correlation of population activity and increased trial-to-trial reliability, specifically during a natural movie stimulus. It improved the information-processing efficiency by enhancing the single-neuron coding capacity, suggesting a cortical network mechanism of the enhanced perception produced by psychoactive stimulants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-022-00965-z.

Keywords: Methcathinone, Synthetic psychoactive substance, In vivo single-unit recording, Ca2+ imaging, Nucleus accumbens, Visual cortex

Introduction

Synthetic cathinones have recently emerged and grown to become popular drugs of abuse [1]. Their dramatic increase has partially resulted from sensationalized media attention as well as widespread availability. Due to the simple manufacturing process and lack of proper regulation, it sometimes can be purchased over the internet and in retail shops for personal experimentation and mood elevation. Methcathinone (MCAT) is the β-ketone analogue of methamphetamine and serves as a parent compound to a series of designer drugs and a notably popular novel psychoactive substance. Due to its structural similarity to amphetamine, MCAT is believed to function by enhancing monoaminergic neurotransmission (i.e. dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin) via various mechanisms, including inhibition of monoamine reuptake, the release of neurotransmitters stored inside synaptic vesicles, and direct interaction with receptors [2–4]. Positron emission tomography studies suggested that dopamine transporter density is significantly reduced in chronic MCAT and methamphetamine users, and this is an expected consequence in drug abuse, suggesting functional regulation of the dopaminergic system [5]. Like methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), cocaine, and other psychostimulants, MCAT can induce potent stimulant and euphoric feelings which lasts for hours. The typical desired effects of MCAT include increased alertness and awareness, elevated energy and motivation, enhanced perception and sensation, euphoria, excitement, and improved mood [6, 7]. It might also promote empathogenic effects like openness in communication, social interaction, talkativeness, and intensification of sensory experiences in drug users [8]. The craving for such desired pleasures drives the escalated consumption in many users. Overdose of MCAT also has a wide range of toxic effects with neurological and psychopathological symptoms, such as psychomotor agitation, hallucinations, delusions, hyperthermia, and even death [9–11]. Therefore, it has become a very widely used party drug, and overdose incidents are increasingly reported.

Since synthetic cathinones are chiral chemicals that exist as two enantiomeric forms having different efficacies [12], it may be simpler to study the effects of MCAT in animal models. The behavioral and physiological effects of MCAT and its analogues have been studied using experimental animals. The psychomotor effects of MCAT have been reported in rats and mice [13–15]. Addictive behavior and potential for withdrawal effect are also present in animals with long-term administration [16–18]. Despite numerous clinical cases of MCAT abuse, little is known about the neural network mechanism of its effects. Here, the goal of the present study was to systematically evaluate the effects on neuronal activity upon administration of MCAT in a mouse model. We mapped the whole-brain activity by c-Fos immunohistochemistry and recorded in vivo single-unit firing in the nucleus accumbens core and neuronal Ca2+ dynamics in the primary visual cortex (V1) upon MCAT administration. Combining behavioral testing and the dynamic change of neuronal activity in MCAT-consuming animals, our findings shed light on the neural network mechanism of the psychostimulant effects of MCAT.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Mice were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle and kept at 22–25°C, with ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Drugs

MCAT (Wuhan Zhongchang National Research Standard Technology Co. Ltd, China, #C-019) was prepared as 15 mg/mL stock solutions in saline and three doses of MCAT (1.5, 5.0, and 15.0 mg/kg) or saline were delivered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. In order to minimize the effect of injection volume on behavioral experiments,the MCAT or saline solution was adjusted to the same volume for every mouse.

Behavioral Tests

Behavioral tests were recorded by a digital camera, and movements were extracted and analyzed offline with software (Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co. Ltd) and custom-written MATLAB scripts.

Open Field Test (OFT)

The mouse was placed in the center of the OFT chamber (50 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm) and allowed to explore freely for 20 min. The OFT center ratio was defined as the time spent in the center area (>10 cm from the nearest edge) divided by the time spent in the edge area (within 10 cm of the nearest edge).

Rotarod Test

Mice were placed at the center of the rotarod (Jinan Yanyi Technology Development Co., Ltd, China). then the rotation speed was gradually accelerated to 40 rpm within 0.5 min and kept at the top speed for 5 min. Each mouse was tested three times with 10-min intervals between trials. The time to falling off the rod was measured.

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM)

The maze contained one open center area (5 cm × 5 cm), two open arms (35 cm × 5 cm) and two closed arms (35 cm × 5 cm) enclosed by 15-cm high walls. It was place 50 cm above the ground. Each mouse was placed in the center area with the head facing an open arm. The exploratory activity of the mouse was recorded for 10 min.

Social Preference Test

A mouse was first placed in the social preference test box (30 cm × 70 cm × 30 cm) for 10 min for habituation. Then, a stranger mouse and a plastic rod were each placed in a transparent acrylic cylinder (with an external diameter of 10 cm) at either end of the test box. The test animal was gently guided to the center and allowed to freely explore for 10 min. The area within a 5-cm distance to the acrylic cylinder containing the stranger mouse or the plastic rod was defined as the social or object interaction zone. The social preference index was calculated as the ratio of the social interaction time to the object interaction time.

C-Fos Immunohistochemistry and Quantification

The mice were handled for 30 min each day for 3 days before intraperitoneal injection of MCAT (5.0 mg/kg) or saline. 2.5 h after injection, the mice were euthanized with an overdose chloral hydrate, cardioperfused with 4% PFA in 0.1 mol/L PBS, and the brains were extracted. Serial sections were cut at 30 μm on a cryostat (Leica CM1520), and every tenth section was collected for c-Fos immunohistochemistry. The free-floating sections were incubated with the primary antibody [c-Fos (9F6) rabbit monoclonal antibody, Cell Signaling, China, #2250S] at 4°C for 2.5 days and then with the secondary antibody (CoraLite488-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG, Proteintech Group, Inc., China, #SA00013-2) for 2 h at 37°C. Fluorescence images were acquired with SV120 Olympus automatic section scanning system (10× objective, 0.4 NA, Japan). The locations of c-Fos+ cells in all serial images were marked with the Multi-point tool in ImageJ. WholeBrain software [19] was applied to register the images to the atlas and quantify marked c-Fos+ cells, as described in previous work [20].

Surgery

5% chloral hydrate (10 mL/kg), atropine (30 g/kg) and lidocaine (0.02 g/mL) were administered before surgery. The animal was head-fixed to a stereotaxic frame (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd, China), and the body temperature was maintained at 36.6°C by a heating pad. For multichannel recording, a craniotomy was made above the nucleus accumbens core (1.09 mm posterior to Bregma; 1.0 mm lateral to the midline; 0.8–1.0 mm in diameter) . A custom-made 16-channel electrode was slowly inserted to the target area (3.5 mm below the brain surface) through the craniotomy. For in vivo Ca2+ imaging, a custom-made titanium head-plane was first fixed to the skull with dental acrylic cement. A craniotomy (~4 mm in diameter) was carefully made above the right primary visual cortex. rAAV-CamKII-GCaMP6f (140 nL, 1010 VP/mL, BrainVTA Co., Ltd, China) were injected into layers II/III (0.2 mm below the pia) using a glass micropipette attached to a micro-injection apparatus (World Precision Instruments, USA). The CamKII promotor restricted the expression of GCaMP6f in excitatory neurons in the visual cortex. The cranial window was sealed with a 4-mm glass coverslip. Tolfedine (150 mg/kg, i.p.) was given daily for 5 days. Recordings were made at least 2 weeks after recovery from the surgery.

In vivo Multichannel Recording and Spike Sorting

We recorded extracellularly from NAc core neurons using a 16-channel home-made moveable multichannel electrode with an impedance of 700–800 kΩ as described in previous studies [21, 22]. The electrical signal was recorded using an Open Ephys acquisition board and graphical user interface (GUI) software [23] at 30 kHz and filtered with a bandpass of 300–6,000 Hz. Activity before and after administration of saline or MCAT (5.0 mg/kg) was recorded for 20 and 40 min, respectively. Spikes were analyzed offline with the Open Ephys GUI. The spike waveform was digitized (40 points per waveform), and the spike threshold was determined with triple standard deviations. Spikes were sorted and manually checked with MClust [24]. Principal component analysis was applied to separate different waveforms from the same channel. Isolated units (Lratio <0.2, isolation distance >15) were included for further analysis. The putative units whose mean firing rates changed >5 times of the standard deviation were defined as the activated or suppressed. The units with occasional burst activity and large standard deviations of firing rates were defined as activated or suppressed when their mean firing rate increased or decreased by >60% from the pre-administration rate, and the rest were defined as non-change units.

Two-Photon Ca2+ Imaging

Ca2+ imaging was applied with a resonant-galvo scanning two-photon microscope (Scientifica, Ltd, UK) with a 16×/0.8 NA Nikon objective at 2× zoom (with a field of view of ~ 250 × 250 μm2 at a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels and a speed of 30 frame/s) controlled by ScanImage software (Vidrio Technologies, LLC., USA). Ca2+ transients reported by GCaMP6f were recorded by two-photon excitation achieved with a Mai Tai DeepSee laser (Spectra-Physics, USA) running at a wavelength of 920 nm. The natural movie was captured from a camera fixed on the head of a freely-moving mouse in the home cage. Retinotopy was first mapped with chessboard stimuli. The spontaneous activity was recorded with a gray screen for 300 s (the gray screen phase). The visual evoked response was recorded while displaying the natural movie (the movie phase) for 135 s (30 s per trial, 4 repeats, with s 5-s interval of gray screen between trials). The spontaneous and visual stimulus responses were recorded before and after MCAT injection.

Movement correction was first performed in EZcalcium [25] and ROIs were manually identified in ImageJ. The fluorescence intensity trace (F) of each neuron was extracted, and ΔF/F was calculated. The neurons with visual evoked Ca2+ transients >5-fold the SD of spontaneous activity were considered visually responsive and included for further analysis. Neurons with a mean ΔF/F change >25% after drug administration during either the gray screen phase or the natural movie phase were defined as activated or suppressed, respectively, and the rest as non-change neurons. The ΔF/F traces of all neurons were binned at 3 Hz for further analysis. The population correlation coefficient and noise correlation were calculated as the averaged Pearson correlation coefficient of the mean and mean-subtracted ΔF/F between each neuron and the rest of the population. The trial-to-trial reliability was calculated as the average Pearson correlation coefficient of four repetitions during the movie stimulus. For discrimination analysis, the single-trial movie response in a given bin (Ai, where i is the trial number) was compared with the mean response (averaged across 4 natural movie trials) in the same bin (<A>) and in a different bin (<B>) by the Euclidian distances d(Ai, <A>) and d(Ai, <B>) [26]. The classification was regarded as correct if d(Ai, <A>) < d(Ai, <B>), and incorrect if d(Ai, <A>) > d(Ai, <B>). Discrimination performance was assessed by the percentage of correct classifications for all the trials. For a population with >3 neurons (n ≥4), the number of combinations was too large to compute. We randomly selected 50,000 combinations of the subpopulation from each animal, repeated 50 times, and took the average value. Single-neuron information (I) was calculated as I = 1 + (p)log2(p) + (1-p)log2(1-p), where p is the discrimination performance of a given neuron when cell number n = 1.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as the mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Statistical analysis were performed with SPSS. Comparisons were made with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), unpaired Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001. All statistical results are listed in Tables S1–S7.

Results

MCAT Increases the Number of Active Neurons in Most Brain Regions

In order to evaluate the dosage-dependence, we first examined the impact of MCAT using a series of behavioral tests. Mice were injected with three doses of MCAT (1.5, 5.0, and 15.0 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline before the behavioral test. In the OFT, higher doses of MCAT also increased the total distance moved and mobility time during the test (Fig. 1B1, B2). The time spent in the center was also decreased in animals treated with 15.0 mg/kg MCAT (Fig. 1B3). This was likely due to the increasing time spent running along the walls of the test box rather than reducing free exploration (Fig. 1A). The MCAT treatment also led to hyperlocomotion in the circular OFT (Fig. S1A–D). The hyperactivity was not likely due to the change in general motor control, as all four groups spent similar riding time on the rotating rod (Fig. 1C). Examples from each group are shown in Fig. 1A. Moreover, the high-dose MCAT group (15.0 mg/kg) also spent less time in the open arms in the elevated plus maze (EPM) (Fig. 1D, E). Furthermore, the mouse given 15.0 mg/kg MCAT spent considerably less time exploring either cylinder, instead running along the walls of the box, similar to the behavior in the OFT. Thus, high-dose MCAT resulted in hyperlocomotion that was too strong to explore the social partners and novel objects (Fig. 1F, G, H1, 2). In contrast, medium-dose MCAT caused the mice to spend much less time exploring the novel object than interacting with the stranger mouse (Fig. 1F, G, H1, 2), resulting in a higher social preference index (Fig. 1H3). In summary, MCAT treatment increased locomotion and high-dose (15.0 mg/kg) MCAT had strong effects (i.e., running along the walls). Therefore, a medium-dose (5.0 mg/kg) MCAT was used for all the functional studies in the following studies.

Fig. 1.

MCAT induces hyperlocomotion in a dose-dependent manner. A Performance of one mouse from each group during an open field test (OFT). Left panels show trajectories of motion tracking of a mouse navigating the OFT box. Heatmaps show the accumulated residence time of the mouse at each location in the OFT (middle) and the average speed when the mouse crossed each location (right). B Total travel distance (B1), total mobility time (B2), and center ratio (B3, center area time divided by edge area time) in saline and MCAT (1.5, 5.0, and 15.0 mg/kg) groups during OFT. C, Riding time on the rotating rod during rotarod test. D Performance of one mouse from each group during the elevated plus maze (EPM) test, similar to panel A. E Time spent in open arms (E1), number of entries into open arms (E2), ratio of time spent in open arms to closed arms (E3), and total mobility time (E4) in saline and MCAT (1.5, 5.0, and 15.0 mg/kg) groups in the EPM. F Schematic of social preference test apparatus. G Performance of one example mouse from each group during the social preference test, similar to panel A (black and white circles represent the location of transparent cylinders containing the stranger mouse and the object, marked as M and O, respectively). H Interaction time around the social partner cylinder (H1), object cylinder (H2), social preference index (H3, calculated as social interaction time divided by object interaction time), and total travel distance (H4) in saline and MCAT (1.5, 5.0, and 15.0 mg/kg) groups during the social preference test. All data are the mean ± SD. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001 (vs saline group); #P <0.05, ##P <0.01, ###P <0.001 (vs MCAT 1.5 mg/kg); $$P <0.01 (vs MCAT 5.0 mg/kg); one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey tests.

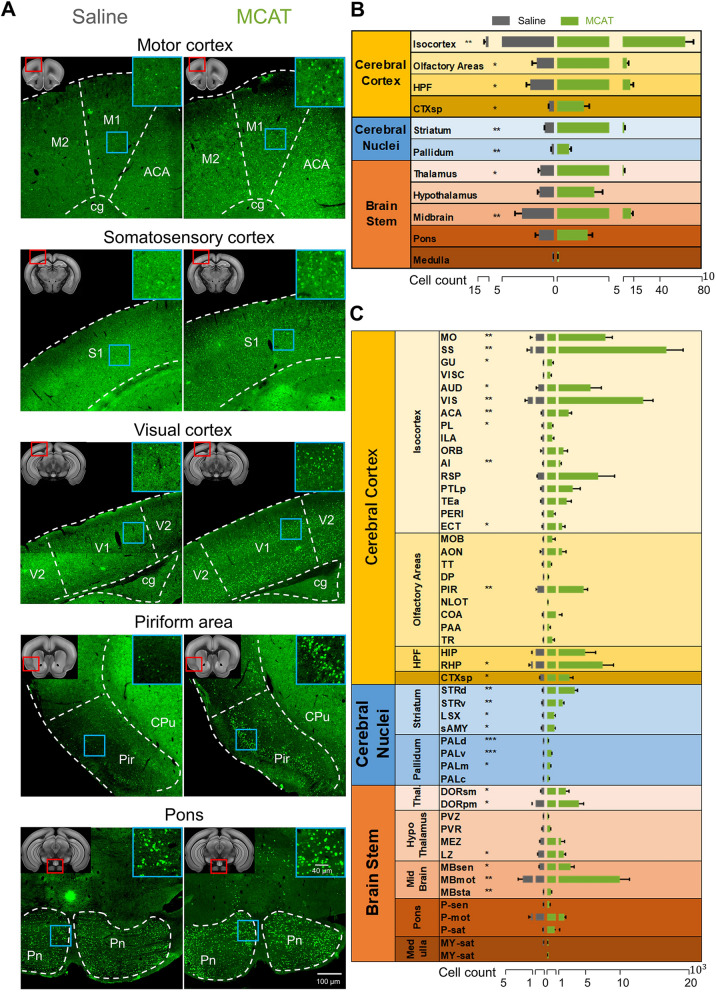

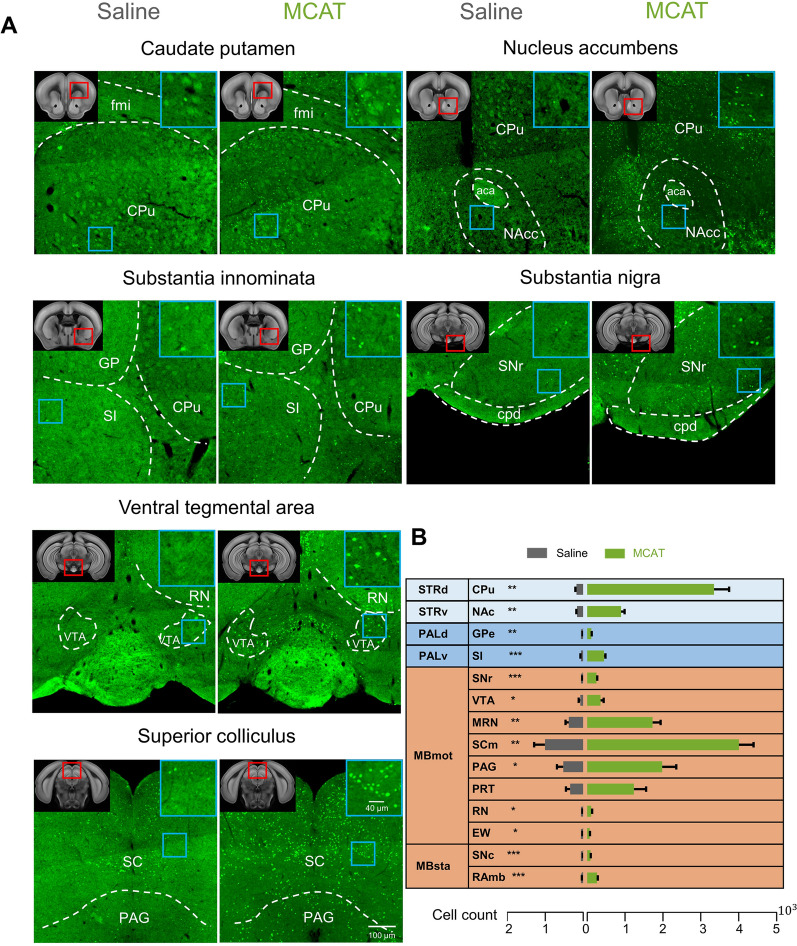

To identify the effects of MCAT on neuronal activity across the brain, we applied c-Fos staining to serial sections following injection of saline or 5.0 mg/kg of MCAT. Each set of sections was imaged with an SV120 Olympus automatic section scanning system and registered to the Allen Brain Reference Atlas using the WholeBrain framework [19]. The c-Fos+ cells were marked and quantified according to atlas segmentation [20]. Quantitative analysis showed that MCAT generally elevated brain activity, with a considerably increased number of c-Fos+ cells across the whole brain. In the MCAT-treated group, the average number of total c-Fos+ cells was 122 519 (152 854, 95 011, and 119 693 for each mouse), whereas that in the saline-treated group it was only 20 536 (18 218, 25 854, and 17 535 for each mouse), resulting in an almost 6-fold difference between the two groups (Fig. 2). MCAT exerted a strong influence on neuronal activity in the isocortex, especially the motor- and sensory-related regions. The numbers of c-Fos+ neurons in the motor cortex, somatosensory cortex, visual cortex, and piriform area were several-fold higher after MCAT injection than after saline (P <0.01, unpaired Student’s t-test, Fig. 2C, Tables S3 and S4). Subcortical areas, including the dorsal striatum and pallidum, also contained a larger number of c-Fos+ neurons (Fig. 2C), likely because these regions are closely associated with movement initiation and regulation [27–29]. Importantly, the nucleus accumbens, which plays a crucial role in reward and addiction [30, 31], was significantly activated by MCAT administration (Fig. 3 and Table S4). Midbrain areas associated with motor and sensory functions also contained a larger number of c-Fos+ neurons (Fig. 2C). Several regions associated with the maintenance of vital signs were less affected by MCAT, including the hypothalamus (except the lateral hypothalamus), medulla, and pons (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

MCAT boosts neuronal activity across the brain. A Example images of c-Fos staining in different brain regions in saline and MCAT (5.0 mg/kg)-treated mice (upper left, red box location of each section is indicated in the atlas image; upper right, high-resolution image of the region in the cyan box). B, C, Quantification of c-Fos+ neurons across brain (note, cell numbers are on a logarithmic scale). The distribution of c-Fos+ cells was compared across 11 major brain regions (B) and 50 subdivided brain areas (C) (n = 3 mice per group). Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM), *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001; unpaired Student’s t-test (statistics are listed in Tables S2 and S3).

Fig. 3.

MCAT activates neurons in subcortical regions associated with sensory and motor functions. A Example images of c-Fos staining in different subcortical regions in saline and MCAT (5.0 mg/kg) treated mice (upper left, red box location of each section is indicated in the atlas image; upper right, high-resolution image of the region in the cyan box). B Quantification of c-Fos+ neurons in motor-related subdivisions of the striatum, pallidum and midbrain. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM), *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001; unpaired Student’s t-test.

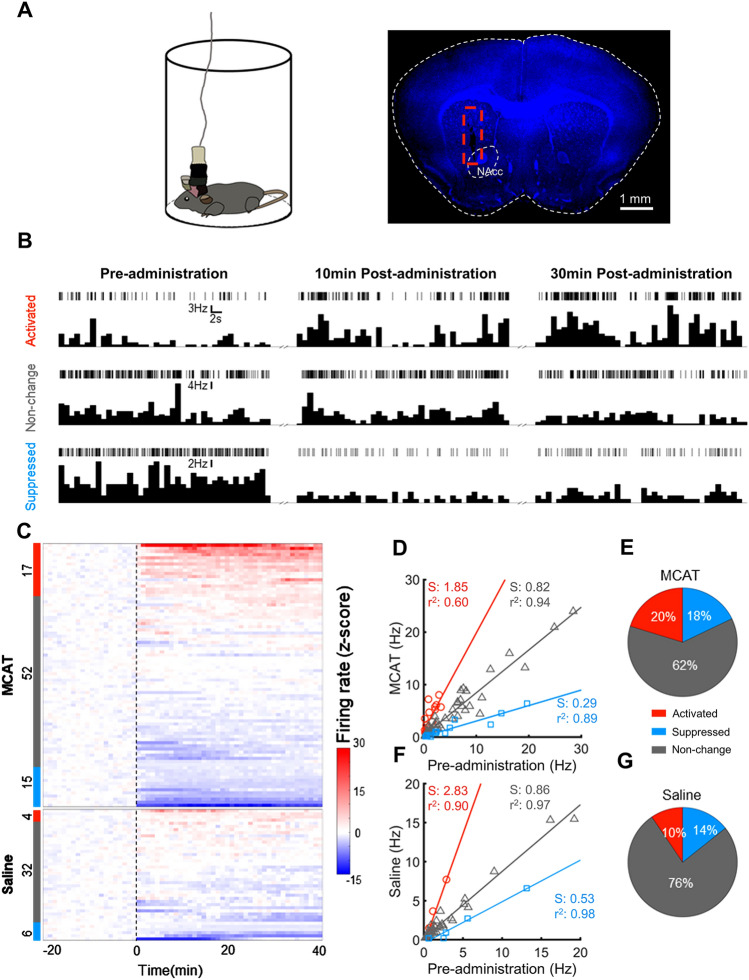

MCAT Changes the Dynamics of Neuronal Firing in the Nucleus Accumbens Core

To clarify real-time changes in the activity dynamics induced by MCAT, we applied in vivo multi-channel recordings to determine the real-time effects of MCAT on neuronal firing in the NAc core. To reduce the impact of locomotor movement on neuronal activity, mice were confined in a transparent cylinder during recording (Fig. 4A). Neuronal activity was activated, suppressed, or unchanged after saline or MCAT injection. Example raster plots and peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) of typical single units are shown in Fig. 4B. The change in firing activity could last for at least 30 min after drug injection. The z-scores of the firing rates of all recorded neurons before and after MCAT or saline injection were plotted as heatmaps (Fig. 4C) and the neurons were sorted according to their activity modulation patterns. The mean firing rate of each neuron before and after administration of MCAT or saline was compared in the three groups (Fig. 4D, F), and the linear regression of firing rate before and after drug injection in each sub-population confirmed the modulation pattern. The MCAT group showed a higher proportion of activated (20%) and suppressed (18%) neurons than the saline group (10% and 14%, respectively, Fig. 4E, G). Therefore, MCAT can significantly modulate the neuronal firing activity in the NAc core.

Fig. 4.

MCAT induces prominent bidirectional changes in firing patterns in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core. A Schematic of the electrophysiological recording (left) and an example post-surgical brain slice from the recorded mouse, with the electrode location highlighted with a red dashed box. B Firing patterns of three example units representing activated, unchanged, and suppressed types of cell. Firing patterns before MCAT (5.0 mg/kg) administration and 10 and 30 min after MCAT administration are shown as raster plots and peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs). C Z-scores of firing rates from all recorded units in MCAT and saline groups (dotted line, time of MCAT or saline administration (n = 84 units from 5 mice in MCAT group, n = 42 units from 5 mice in saline group). Color tags on the left indicate the group to which each unit belongs, red, gray, and blue tags represent activated (firing increased), unchanged, and suppressed (firing decreased) units, respectively. Numbers near tags indicate the number of units in each group. D Summary of average firing rates before and after MCAT administration. Each symbol represents one recorded unit (red circles, activated; gray triangles; unchanged; blue squares, suppressed groups; red, activated; gray, unchanged; and blue, suppressed units’ linear regression. Linear regression slopes (S) and coefficients (r2) of each group are annotated in the corresponding colors. E Proportion of activated, suppressed, and unchanged units in the MCAT group. F, G Summary of firing rates of saline group, similar to D, E.

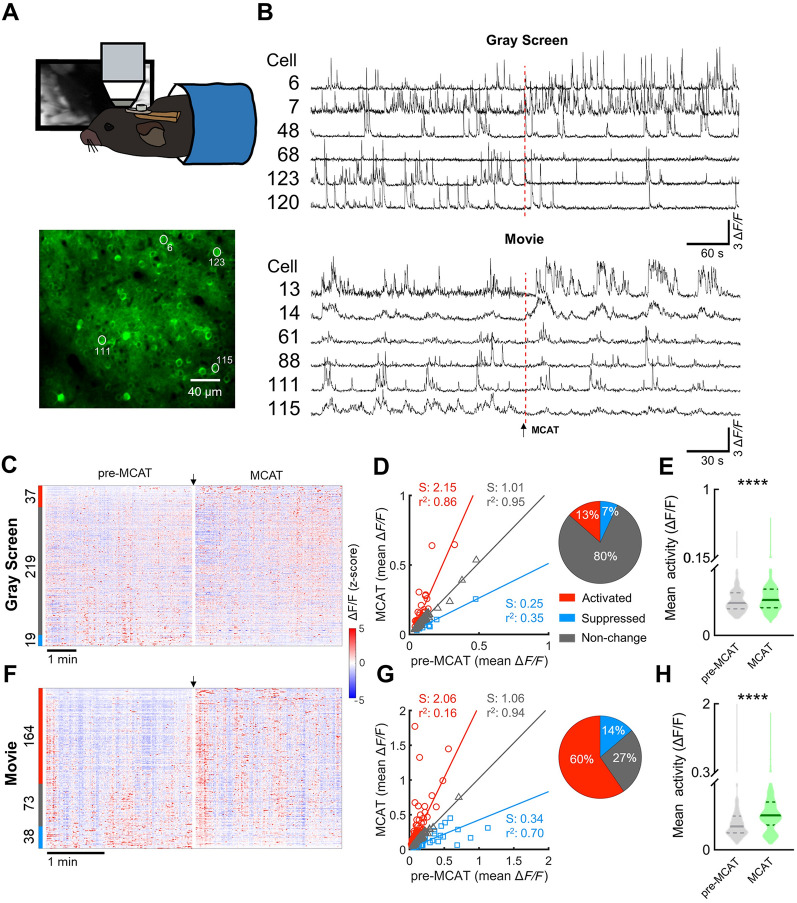

MCAT Increases the Activity of Layer II/III Neurons in the Primary Visual Cortex

MCAT administration (5.0 mg/kg) increased the number of c-Fos+ neurons in the cerebral cortex, especially in the sensory and motor areas (Fig. 2). To investigate whether and how MCAT influenced sensory information processing, we next examined the dynamics of population activity of layer II/III excitatory neurons in the primary visual cortex before and after MCAT administration (5.0 mg/kg) using in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 5A). Adeno-associated virus (AAV-CamKII-GCaMP6f), which expressed GCaMP6f in cortical excitatory neurons, was injected into the primary visual cortex. Both spontaneous activity (during gray screen stimulation) and visual-evoked activity (during natural movie stimulation) were recorded in head-fixed awake mice. Only cells with significant visual-evoked responses were included for analysis (275 out of 539 neurons in 3 mice). The Ca2+ transients of a few example neurons are shown in Fig. 5B. MCAT slightly increased the spontaneous Ca2+ activity. In contrast, it dramatically increased the visual evoked activity by 50% (Fig. 5E, H). The activities of all neurons before and after MCAT administration are shown as heatmaps (Fig. 5C, F). The neurons were divided into three clusters according to the modulation patterns, i.e., increased (activated), unchanged, and decreased (suppressed), similar to those in the NAc core, and Linear regression also confirmed the modulation patterns (Fig. 5D, G). With MCAT administration, the spontaneous activity of most neurons remained unchanged (Fig. 5D inset), but surprisingly, the visually-evoked Ca2+ transients in most neurons were significantly increased (Fig. 5G inset). MCAT induced a similar magnitude of activity change during both the gray screen and visual stimulation phases, as shown by the similar linear regression slopes of those neurons in both the increased and suppressed activity groups (Fig. 5D, G). After all, the total spontaneous and visual evoked activity was significantly increased after MCAT injection (Fig. 5E, H), and the Ca2+ transients in response to visual stimuli were significantly elevated in most cortical excitatory neurons after MCAT injection.

Fig. 5.

MCAT increases spontaneous and visual-evoked activity of layer II/III pyramidal neurons in primary visual cortex. A Schematic of in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging in an awake mouse (upper) and example image of recorded layer II/III neurons expressing GCaMP6f (lower, white circles and adjacent numbers indicate neurons in B). B Example Ca2+ traces from V1 neurons during spontaneous activity (gray screen) and in response to a visual stimulus (natural movie) (red dashed lines indicate time of MCAT administration). C Heatmaps of spontaneous activity (z-score of ΔF/F) before and after MCAT administration (n = 275 cells from 3 mice; arrow, time of MCAT injection). Color tags on left indicate activity modulating patterns (red, increased; gray, unchanged; blue, decreased; adjacent numbers, number of neurons of each type). D Summary of spontaneous activity before and after MCAT administration. Each symbol represents one recorded unit (red, activated; gray, unchanged; blue, suppressed; linear regressions use the same convention). Linear regression slope (S) and coefficient (r2) of each group are annotated in corresponding colors. Pie chart shows the percentages of activated, suppressed, and unchanged neurons. E Total spontaneous activity of all recorded neurons before and after MCAT treatment (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, Z = –6.45, P = 1.11 × 10–10). F–H Activity of V1 neurons in response to a visual stimulus (natural movie), similar to C–E (H, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, Z = –8.43, P = 3.39×10–17).

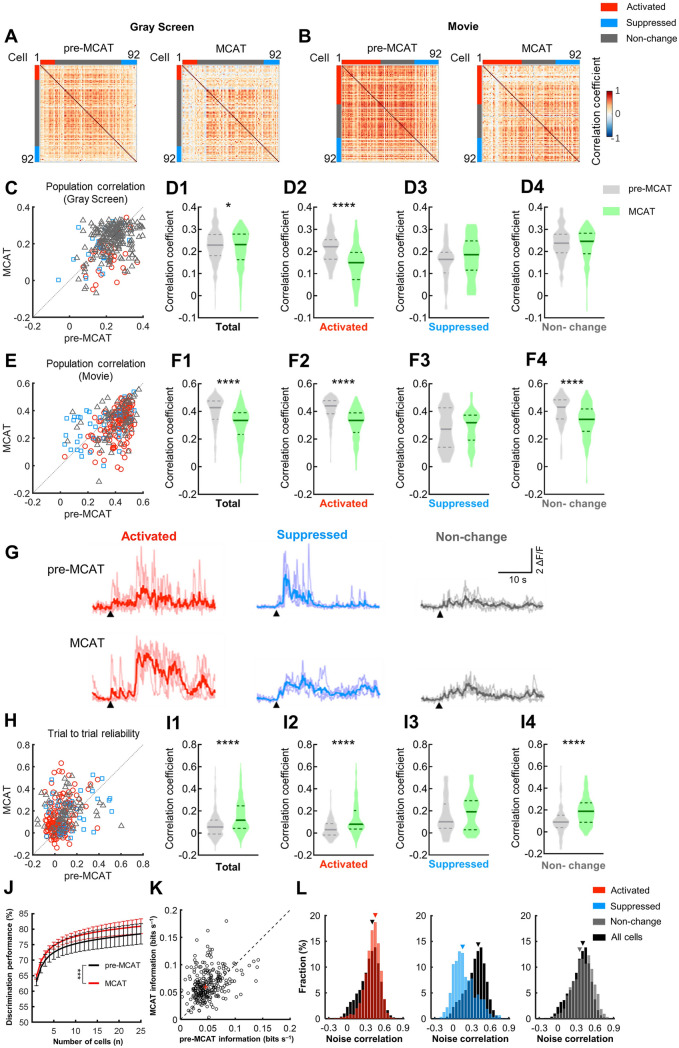

MCAT Reduces Population Correlation and Increases Trial-to-trial Reliability in Response to Natural Movies

Overall, neuronal activity in the visual cortex was elevated upon MCAT administration, but its impact on sensory information processing was still unclear. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for the activity of each neuron with the rest of the population from the same experiment during the gray screen phase (spontaneous activity) and visual stimulus phase (visual-evoked activity, Fig. 6A, B). The population correlation of spontaneous activity slightly increased upon MCAT injection (Fig. 6D1), but the population correlation during natural movie stimulation became strongly de-correlated (from 0.43 ± 0.11 to 0.34 ± 0.11, mean ± SD, Fig. 6F1). We further separately analyzed the correlation of population activity of the three types of neuron. The correlations between neurons in each group and the rest of the population before and after MCAT administration were compared (Fig. 6C, E). Only the activated group showed de-correlation of spontaneous population activity (Fig. 6D2–4). During a visual stimulus, the neurons in both the increased and unchanged groups became much more de-correlated upon MCAT administration (Fig. 6F2–4). De-correlation of population activity, specifically during visual stimulation, indicated that V1 might become more desynchronized to reduce the population redundancy and code more visual information during movie stimuli. We also examined the trial-to-trial reliability of each neuron during four repetitions of movie stimuli by computing the Pearson correlation coefficient of its responses between each pair of repeats and averaging the correlation coefficients over all pair-wise combinations (Fig. 6H, I). Overall reliability increased by ~1.5-fold after MCAT administration (Fig. 6I1). Neurons from all three activity-modulated groups became much more reliable on coding visual information after MCAT treatment (Fig. 6I2–4), although the suppressed group did not meet the criterion for statistical significance.

Fig. 6.

MCAT decreases population correlation and increases coding reliability during visual stimulation. A Correlation coefficient matrices for V1 neurons during a gray screen recording session before and after MCAT administration (color tags indicate type of neuron: red, activated; gray, unchanged; blue, suppressed responses). B Correlation coefficient matrices for V1 neurons during a natural movie recording session before and after MCAT administration, similar to A. C Summary of population correlation coefficients of spontaneous activity before and after MCAT administration (each symbol represents the correlation of one neuron to remaining: color conventions as in A). (n = 275 cells from 3 mice). D Violin plots of correlation coefficients of total population D1, activated D2, suppressed D3, and unchanged types of neuron D4 (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, D1, Z = –2.24, P = 0.0249, n = 275; D2, Z = –3.72, P = 8.94×10–5, n = 37). E, F, Summary of population correlation coefficients before and after MCAT treatment in response to a natural movie stimulus, similar to C, D (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, F1, Z = –10.07, P = 7.38×10–24, n = 275; F2, Z = –10.23, P = 1.52×10–24, n = 164; F4, Z = –4.62, P = 1.39×10–6, n = 73). G Light line, example Ca2+ traces in each trial of a natural movie stimulus; dark color, average Ca2+ response of the 4 repeats (black arrowheads, start of the movie stimulus). H, I Summary of trial-to-trial reliability revealed by correlation coefficients before and after MCAT treatment during a natural movie stimulus, similar to C, D (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, I1, Z = –7.81, P = 5.67×10–15, n = 275; I2, Z = –6.97, P = 3.17×10–12, n = 164; I4, Z = –4.36, P = 1.30×10–5, n = 73). J The function between discrimination performance and the cell number (n) selected for analysis in 3 mice. All data are the mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA, P = 0.0007. K Single-neuron information before and after MCAT administration. Each point represents one cell (n = 275 cells from 3 mice) and the red cross indicates the median value of all recorded cells (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, Z = –7.38, P = 1.53×10–13). L, Distribution of pair-wise noise correlation of the recorded population ,(black) and the activated (red), suppressed (blue), and unchanged types of neuron (gray) (inverted triangles, median value.

In principle, decreased correlation and increased reliability may improve sensory processing by reducing the population coding redundancy and enhancing the single-neuron coding efficiency [26, 32]. Therefore, we tested the discriminatory performance of the neuronal population of a given size by comparing single-trial responses of the selected neurons to the movie segment (0.33 s per segment) with the matched and unmatched template responses (mean responses across trials). We found that the discriminatory performance increased monotonically with the number of cells in the population (n) and MCAT improved the performance at all the n values that we tested (Fig. 6J). To further investigate the effect of MCAT on visual coding, we used an information-theoretic measure to assess the discriminatory performance. We calculated single-neuron information, which was unaffected by cell-to-cell correlations, and found it increased after MCAT administration (Fig. 6K). Thus, MCAT-induced improvement in response reliability might contribute to the increased information coded by individual neurons. To investigate why MCAT modulated cortical activity in three different ways, we estimated the connectivity of all recorded neurons and the three types of modulated neurons by calculating the noise correlation of each pair within each cohort, since noise correlation between neurons is usually determined by their direct synaptic connections and shared common inputs [33]. We found that the activated group exhibited higher pair-wise noise correlation than the whole population (Fig. 6L). Cortical neurons that were easily activated by MCAT might be correlated with each other with higher probability and strength and/or share more common inputs. Therefore, MCAT might not just simply boost the global activity of the brain, but may selectively promote previously well-connected subnetworks to enhance the capacity for information processing. Such function might be a distinct characteristic of the effects of MCAT on neural networks and is independent of overall activity changes. This might be a functional mechanism underlying the augmented perceptual capacity experienced by users of MCAT and other synthetic cathinones.

Discussion

We used a set of in vivo functional approaches to evaluate the effects of MCAT in mice. There were three interesting findings. First, at the behavioral level, MCAT produced dose-dependent changes in locomotion. Enhancement of spontaneous locomotor activity in mice occurred after injection of MCAT at medium and high dosages (5.0 mg/kg and 15.0 mg/kg) in the OFT and EPM. Second, at the central nervous system level, MCAT boosted a 6-fold increment of activated neurons across the brain. Third, MCAT strongly modulated the patterns of neuronal activity in the NAc core and the visual cortex. The strong increase in cortical response and de-correlation of population activity, especially during visual information processing, indicates that the coding efficiency and precision of visual cortical neurons are improved.

The effects of MCAT in mice mimics several aspects in human users. MCAT induced a remarkable increase in locomotion in mice, which is also the most prominent behavioral effect reported in rodents [13, 15, 34], similar to the hyperactive effects and higher psychomotor capacity produced by synthetic cathinones in humans. In addition, the MCAT groups ran along the walls of the OFT enclosure; this was particularly dramatic in the cOFT, where the animals did not need slow down in the corner to make a turn (Fig. 1A, B, S1). Characterized lap running of the periphery has also been reported in psychoactive synthetic cathinones such as MDMA [18, 35, 36]. Notably, mice receiving high-dose MCAT (15.0 mg/kg, Fig. 1A) exhibited non-stop high-speed running along the wall and hit the wall at the corner as they could not coordinate movement to decelerate and avoid hitting the wall. In the social preference test, the high-dose group also ran frenetically along the wall at high speed, completely ignoring the presence of the social partner or the novel object in the chamber (Fig. 1F–H). It seems that MCAT hijacks the central nervous system, producing hyperactive locomotion in an exaggerated state. Such behavior mimics the manic behavior reported in overdosing human users [6, 7]. Overall, the behavioral tests revealed that the effects of MCAT on mice are relatively like its psychostimulant effects reported by human users, suggesting that mice are good animal models for studying the neuronal mechanisms of such drugs.

MCAT has long been believed to act through the monoaminergic system due to its structural similarity to amphetamine [3, 37, 38]. However, there is no systematic analysis of its impact on changing brain activity [39, 40]. Here, we applied c-Fos immunohistochemistry to serial brain sections following MCAT administration. Using whole-brain imaging to quantify the distribution of c-Fos+ cells, we found that MCAT increased the number of activated cells by nearly 6-fold in most areas, similar to MDMA [41], including the striatum, cerebral cortex, especially the sensory and motor areas, hippocampal formation, thalamus, and motor-related brain stem. The enhanced activity in the striatum is likely related to the potentiation effect of MCAT on the dopaminergic system [3, 4, 37, 42]. The distribution of increased c-Fos+ neurons was also consistent with the distribution of direct dopaminergic innervation, which includes the cerebral cortex, olfactory structures, striatum, septum, amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, and brain stem [43]. The increased activity in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and brain stem may be associated with enhanced dopaminergic signaling during sensory perception and motor activity after drug use [13, 44–46].

We also found that the firing rates of many neurons changed following the administration of MCAT, 20% of neurons showing an increase and 14% showing a decrease. These results may be associated with the opposite effects of dopamine on D1-MSNs and D2-MSNs [47, 48], which may lead to a de-correlation in neuronal activity in the NAc core. Considering the potential elevation of dopamine level after MCAT administration [2], neurons expressing D1-receptors may be activated and those expressing D2-receptors may be inhibited, whereby MCAT may up-regulate the direct pathway and down-regulate the indirect pathway. Similarly, D1 and D2 receptors differentially contribute to MDMA-induced hyperactivity; that is, D1R-KO mice exhibit a significant increase in MDMA-induced hyperactivity, while D2R-KO mice exhibit a reduction in MDMA-induced hyperactivity [49]. Previous studies have suggested that a tonic increase in motivation is positively correlated with neuronal firing activity [50–52]. Modulation of neuronal activity in the NAc core may be the underlying mechanism of the vigorous reward-seeking behavior observed after drug consumption [36]. In addition, the psychostimulatory effects of MCAT may strengthen monoaminergic neurotransmission involving dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin via various mechanisms, including inhibition of monoamine re-uptake [4, 44, 53]. Enhanced dopamine release in the NAc core may have dichotomous effects via D1 and D2 receptors. However, the exact mechanism still needs to be explored.

We also found that neuronal activity in sensory and motor cortices was remarkably increased, which may reflect the stimulatory effects of MCAT. Based on in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging, we found that MCAT administration resulted in de-correlation of population activity and increased reliability of single neuron activity during a visual stimulus (Fig. 6). Therefore, MCAT can improve information processing efficiency by enhancing the coding capacity of individual neurons. This might explain why MCAT had a much stronger effect on visual evoked activity than spontaneous activity, as the natural movie contained much more information to be coded than the gray screen. Therefore, MCAT did not simply elevate the activity level of the central nervous system but specifically promoted information process in the brain by enhancing the capacity to extract features from the sensory inputs. The underlying mechanism might be that MCAT selectively boosted subnetworks with higher intrinsic connectivity (Fig. 6L), as the recurrent connection is the fundamental cortical network architecture for the emergence of feature selectivity. This may be a general cortical network mechanism underlying the enhanced sensation and hyperalertness produced by MCAT in many human users [6, 7].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31871089 and 31871028), Junior Thousand Talents Program of China, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (HUST: 2172019kfyXKJC077 and HUST: 2172019kfyRCPY064), Key Laboratory of Forensic Toxicology, Ministry of Public Security of China (Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau: 2020FTDWFX02 and 2019FTDWFX06). We thank Dr. Pengcheng Huang in Dr. Haohong Li’s lab for help in setting up the in vivo multichannel recording. We thank Drs Haohong Li, Luoying Zhang, Shangbang Gao, Bo Xiong, Peng Fei, Zheng Guo, and Yan Zhang for valuable discussion. We thank the imaging core facility in the School of Basic Medicine in HUST for help in acquisition of the serial images of c-Fos staining.

Conflict of interest

All authors provided critical edits and feedback on the finalized paper.

Footnotes

Jun Zhou and Wen Deng contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Man Jiang, Email: manjiang@hust.edu.cn.

Man Liang, Email: liangman@hust.edu.cn.

Yunyun Han, Email: yhan@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Baumann MH, Volkow ND. Abuse of new psychoactive substances: Threats and solutions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:663–665. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blough BE, Decker AM, Landavazo A, Namjoshi OA, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, et al. The dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine releasing activities of a series of methcathinone analogs in male rat brain synaptosomes. Psychopharmacology. 2019;236:915–924. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5063-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gygi MP, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. Methcathinone: an initial study of its effects on monoaminergic systems. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:1066–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies RA, Baird TR, Nguyen VT, Ruiz B, Sakloth F, Eltit JM, et al. Investigation of the optical isomers of methcathinone, and two achiral analogs, at monoamine transporters and in intracranial self-stimulation studies in rats. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:1762–1769. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann UD, Wong DF, Yokoi F, Villemagne V, Dannals RF, Ricaurte GA. Reduced striatal dopamine transporter density in abstinent methamphetamine and methcathinone users: Evidence from positron emission tomography studies with[11C]WIN-35, 428. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8417–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papaseit E, Pérez-Mañá C, Mateus JA, Pujadas M, Fonseca F, Torrens M, et al. Human pharmacology of mephedrone in comparison with MDMA. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2704–2713. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papaseit E, Olesti E, Pérez-Mañá C, Torrens M, Fonseca F, Grifell M, et al. Acute pharmacological effects of oral and intranasal mephedrone: An observational study in humans. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14:100. doi: 10.3390/ph14020100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karila L, Megarbane B, Cottencin O, Lejoyeux M. Synthetic cathinones: A new public health problem. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:12–20. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666141210224137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torrance H, Cooper G. The detection of mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone) in 4 fatalities in Scotland. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;202:e62–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumann MH, Solis E, Jr, Watterson LR, Marusich JA, Fantegrossi WE, Wiley JL. Baths salts, spice, and related designer drugs: The science behind the headlines. J Neurosci. 2014;34:15150–15158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3223-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs” (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49:499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almeida AS, Silva B, Pinho PG, Remião F, Fernandes C. Synthetic cathinones: Recent developments, enantioselectivity studies and enantioseparation methods. Molecules. 2022;27:2057. doi: 10.3390/molecules27072057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatch MB, Rutledge MA, Forster MJ. Discriminative and locomotor effects of five synthetic cathinones in rats and mice. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:1197–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3755-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aarde SM, Creehan KM, Vandewater SA, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. In vivo potency and efficacy of the novel cathinone α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: Self-administration and locomotor stimulation in male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:3045–3055. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wojcieszak J, Andrzejczak D, Wojtas A, Gołembiowska K, Zawilska JB. Methcathinone and 3-fluoromethcathinone stimulate spontaneous horizontal locomotor activity in mice and elevate extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in the mouse striatum. Neurotox Res. 2019;35:594–605. doi: 10.1007/s12640-018-9973-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atehortua-Martinez LA, Masniere C, Campolongo P, Chasseigneaux S, Callebert J, Zwergel C, et al. Acute and chronic neurobehavioral effects of the designer drug and bath salt constituent 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone in the rat. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:392–405. doi: 10.1177/0269881118822151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojcieszak J, Kuczyńska K, Zawilska JB. Behavioral effects of 4-CMC and 4-MeO-PVP in DBA/2J mice after acute and intermittent administration and following withdrawal from intermittent 14-day treatment. Neurotox Res. 2021;39:575–587. doi: 10.1007/s12640-021-00329-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Wetering R, Schenk S. Repeated MDMA administration increases MDMA-produced locomotor activity and facilitates the acquisition of MDMA self-administration: Role of dopamine D 2 receptor mechanisms. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:1155–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fürth D, Vaissière T, Tzortzi O, Xuan Y, Märtin A, Lazaridis I, et al. An interactive framework for whole-brain maps at cellular resolution. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:139–149. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0027-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma LP, Chen WQ, Yu DF, Han YY. Brain-wide mapping of afferent inputs to accumbens nucleus core subdomains and accumbens nucleus subnuclei. Front Syst Neurosci. 2020;14:15. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2020.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao ZD, Chen ZM, Xiang XK, Hu MN, Xie HC, Jia XN, et al. Zona incerta GABAergic neurons integrate prey-related sensory signals and induce an appetitive drive to promote hunting. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:921–932. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua RF, Wang X, Chen XF, Wang XX, Huang PC, Li PC, et al. Calretinin neurons in the midline thalamus modulate starvation-induced arousal. Curr Biol. 2018;28:3948–3959.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegle JH, López AC, Patel YA, Abramov K, Ohayon S, Voigts J. Open Ephys: An open-source, plugin-based platform for multichannel electrophysiology. J Neural Eng. 2017;14:045003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aa5eea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitzer-Torbert N, Jackson J, Henze D, Harris K, Redish AD. Quantitative measures of cluster quality for use in extracellular recordings. Neuroscience. 2005;131:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantu DA, Wang B, Gongwer MW, He CX, Goel A, Suresh A, et al. EZcalcium: open-source toolbox for analysis of calcium imaging data. Front Neural Circuits. 2020;14:25. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2020.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goard M, Dan Y. Basal forebrain activation enhances cortical coding of natural scenes. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1444–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheruel F, Dormont JF, Amalric M, Schmied A, Farin D. The role of putamen and pallidum in motor initiation in the cat. I. Timing of movement-related single-unit activity. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100:250–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00227195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grillner S, Hellgren J, Ménard A, Saitoh K, Wikström MA. Mechanisms for selection of basic motor programs - roles for the striatum and pallidum. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kravitz AV, Kreitzer AC. Striatal mechanisms underlying movement, reinforcement, and punishment. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27:167–177. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00004.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsen CM. Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robison AJ, Nestler EJ. Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:623–637. doi: 10.1038/nrn3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barlow H. Redundancy reduction revisited. Network: Comput Neural Syst. 2001;12:241–253. doi: 10.1080/net.12.3.241.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko H, Hofer SB, Pichler B, Buchanan KA, Sjöström PJ, Mrsic-Flogel TD. Functional specificity of local synaptic connections in neocortical networks. Nature. 2011;473:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature09880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones S, Fileccia EL, Murphy M, Fowler MJ, King MV, Shortall SE, et al. Cathinone increases body temperature, enhances locomotor activity, and induces striatal c-fos expression in the Siberian hamster. Neurosci Lett. 2014;559:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shankaran M, Gudelsky GA. A neurotoxic regimen of MDMA suppresses behavioral, thermal and neurochemical responses to subsequent MDMA administration. Psychopharmacology. 1999;147:66–72. doi: 10.1007/s002130051143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen JD, Aarde SM, Cole M, Vandewater SA, Grant Y, Taffe MA. Locomotor stimulant and rewarding effects of inhaling methamphetamine, MDPV, and mephedrone via electronic cigarette-type technology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:2759–2771. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anneken JH, Angoa-Perez M, Sati GC, Crich D, Kuhn DM. Assessing the role of dopamine in the differential neurotoxicity patterns of methamphetamine, mephedrone, methcathinone and 4-methylmethamphetamine. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glennon RA, Yousif M, Naiman N, Kalix P. Methcathinone: a new and potent amphetamine-like agent. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1987;26:547–551. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stepens A, Stagg CJ, Platkajis A, Boudrias MH, Johansen-Berg H, Donaghy M. White matter abnormalities in methcathinone abusers with an extrapyramidal syndrome. Brain. 2010;133:3676–3684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stepens A, Groma V, Skuja S, Platkājis A, Aldiņš P, Ekšteina I, et al. The outcome of the movement disorder in methcathinone abusers: Clinical, MRI and manganesemia changes, and neuropathology. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:199–205. doi: 10.1111/ene.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson MR, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Neural correlates of MDMA (“Ecstasy”)-induced social interaction in rats. Soc Neurosci. 2009;4:60–72. doi: 10.1080/17470910802045042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juurmaa J, Menke RA, Vila P, Müürsepp A, Tomberg T, Ilves P, et al. Grey matter abnormalities in methcathinone abusers with a Parkinsonian syndrome. Brain Behav. 2016;6:e00539. doi: 10.1002/brb3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aransay A, Rodríguez-López C, García-Amado M, Clascá F, Prensa L. Long-range projection neurons of the mouse ventral tegmental area: A single-cell axon tracing analysis. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9:59. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suyama JA, Sakloth F, Kolanos R, Glennon RA, Lazenka MF, Negus SS, et al. Abuse-related neurochemical effects of Para-substituted methcathinone analogs in rats: Microdialysis studies of nucleus accumbens dopamine and serotonin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:182–190. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gatch MB, Taylor CM, Forster MJ. Locomotor stimulant and discriminative stimulus effects of ‘bath salt’ cathinones. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:437–447. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328364166d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gatch MB, Dolan SB, Forster MJ. Comparative behavioral pharmacology of three pyrrolidine-containing synthetic cathinone derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:103–110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.223586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Striatal plasticity and basal Ganglia circuit function. Neuron. 2008;60:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao Y, Gao G, Liu K, Shi X, Cheng MX, Xiong Y, et al. Projections from D2 neurons in different subregions of nucleus accumbens shell to ventral pallidum play distinct roles in reward and aversion. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:623–640. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00632-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Risbrough VB, Masten VL, Caldwell S, Paulus MP, Low MJ, Geyer MA. Differential contributions of dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptors to MDMA-induced effects on locomotor behavior patterns in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2349–2358. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrison SE, McGinty VB, du Hoffmann J, Nicola SM. Limbic-motor integration by neural excitations and inhibitions in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurophysiol. 2017;118:2549–2567. doi: 10.1152/jn.00465.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vega-Villar M, Horvitz JC, Nicola SM. NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity in the nucleus accumbens connects reward-predictive cues to approach responses. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4429. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12387-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goto Y, Grace AA. Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:805–812. doi: 10.1038/nn1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gygi MP, Fleckenstein AE, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. Role of endogenous dopamine in the neurochemical deficits induced by methcathinone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1350–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.