Abstract

Background

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the front-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is currently the standard of care. However, as clinical trials include a very limited number of elderly patients, evidence on the safety and efficacy of using ICI-based regimens is still limited.

Methods

A virtual International Expert Panel took place in July 2022 to review the available evidence on the use of ICI-based regimens in the first-line setting in elderly patients with NSCLC and provide a position paper on the field both in clinical practice and in a research setting.

Results

All panelists agreed that age per se is not a limitation for ICI treatments, as the elderly should be considered only as a surrogate for other clinical factors of frailty. Overall, ICI efficacy in the elderly population is supported by reviewed data. In addition, the panelists were confident that available data support the safety of single-agent immunotherapy in elderly patients with NSCLC. Conversely, concerns were expressed on the safety of chemo + ICI-based combination, which were considered mainly related to the toxicities of chemotherapy components. Therefore, suggestions were proposed to tailor combined approaches in the elderly patients with NSCLC. The panelists defined high, medium, and low priorities in clinical research. High priority was attributed to implementing the real-world assessment of elderly patients treated with ICIs, who are mostly underrepresented in pivotal clinical trials.

Conclusions

Based on the current evidence, the panelists outlined the significant limitations affecting the clinical practice in elderly patients affected by NSCLC, and reached common considerations on the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of ICI monotherapy and ICI combinations in the first-line setting.

Key words: immune checkpoint inhibitors, elderly, NSCLC, consensus

Highlights

-

•

Elderly patients are not well represented in clinical trials evaluating ICIs in lung cancer.

-

•

An Expert Panel Meeting was held to provide a position paper on the use of ICIs in the elderly population.

-

•

Common considerations on feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of different ICI treatments were pointed out.

Introduction

The definition of the elderly population was statically set at an age cut-off of 65 years, and more than half of new diagnoses of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are above this age cut-off.1 However, the concept of the elderly evolved into a more complex evaluation, taking into account not only chronological age but also biological age, including individuals’ functional and social status. Hence, several scales and tools2 have been developed to assess specific aspects, including function (i.e. activities of daily living—ADL, instrumental ADL), comorbidities (i.e. Charlson Comorbidity Score), quality of life (QoL) (disease-specific questionnaires), cognition (Folstein Mini-Mental State), and emotions (Geriatric Depression Scale). However, although the geriatric assessment is feasible in cancer patients,3 the impact of comprehensive geriatric assessment on decision making and treatment allocation did not impact survival but slightly reduced toxicity in patients with advanced NSCLC (A-NSCLC) in a phase III trial.4

Indeed, elderly age might better be intended as an indirect measure of potential patient’s functional status, which may be impaired by clinical features commonly acquired by increasing age, including progressive organ function reserve failure (mainly renal, cardiovascular, hepatic, bone marrow function), and acquired chronic comorbidities, also linked to tobacco smoking.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Because of this, in the past years, the concepts of elderly and poor performance status (PS) frequently overlapped, and studies have been conducted to investigate the best chemotherapy approach in the front-line treatment of elderly patients with NSCLC. The main clinical trials in this field showed that the addition of platinum chemotherapy did not improve survival. In contrast, added toxicities were observed as compared to single-agent chemotherapy,10,11 and single-agent chemotherapy was considered as a valid treatment option in the elderly unfit patients.12

The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the front-line treatment of A-NSCLC led to reconsidering the treatment paradigm in elderly patients.

Indeed, single-agent anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1) and anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 (anti-PD-L1) demonstrated prolonged overall survival (OS) and long-term survival in platinum-pretreated patients over standard docetaxel,13, 14, 15, 16 and therefore were firmly established as further-line treatment also in the elderly population.

Soon after, the use of ICIs rapidly moved to the first-line setting of NSCLC treatment. Single-agent anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab and cemiplimab) and anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab) are current standard of care in the first-line treatment of patients with either squamous or non-squamous NSCLC whose tumors have PD-L1 expression ≥50% and are wild type (WT) for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) status.17, 18, 19, 20 Front-line combination of single-agent pembrolizumab or atezolizumab or cemiplimab, as well as dual-agent anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA-4) (nivolumab plus ipilimumab and durvalumab plus tremelimumab), with histology-based platinum-doublet chemotherapy, showed survival benefit over chemotherapy alone regardless of PD-L1 expression levels in EGFR/ALK WT tumors, and are standard treatment options in this setting.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Since eligibility for pivotal clinical trials of first-line ICIs in NSCLC was conditioned by platinum eligibility, the elderly population is not well represented here, with patients ≥75 years of age being almost 10% of the overall population. In addition, the age cut-offs used were different among clinical trials and no information is available on specific subsets of elderly patients included. These aspects are crucial considering that >40% of patients with lung cancer are aged ≥70 years in clinical practice, and therefore represent a significant proportion of potential applicability of ICI-based treatments (monotherapy or combination) in the first-line setting. The main concerns raised on using ICIs in the elderly population were first related to potential toxicity, based on previous studies demonstrating a high prevalence of autoantibodies in the elderly population.28 In addition, immune senescence, meaning the modifications in the immune system activity related to aging, including decreased pro-inflammatory activity (i.e. cytokine production, signal transduction, chemotaxis) of the adaptive and innate immune cells,29 raised doubts on potential ICI efficacy in this special population.

In light of the few prospective data specifically addressing the elderly population, an updated consensus is needed to refocus on the first-line approaches for elderly patients affected by NSCLC in the immunotherapy era.

Methods

The 14th International Experts Panel Meeting by Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Toracica (AIOT) was held virtually on 7 July 2022 to discuss the topic ‘Immunotherapy in the first-line treatment of elderly patients with advanced NSCLC’. The scientific panel of the meeting was made up of five medical oncologists from different countries (Italy, Switzerland, and the United States) with clinical and research expertise in NSCLC treatment. During the first part of the meeting, the available evidence on the use of first-line immunotherapy in elderly patients was formally reviewed to initiate discussion. The second part of the meeting consisted of panelists’ discussion to reach common conclusions to include in a position paper on the field on clinical practice and clinical research.

Published data useful for panel discussion were identified using a PubMed search, carried out with combinations of the following search terms: ‘non-small-cell lung cancer’ and ‘elderly’. Only articles written in English were considered for the discussion. Abstracts presented between 2000 and 2022 at the main international meetings were also searched. The search has been updated for this article with the proceedings of the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology and European Society of Medical Oncology meeting. Relevant references from selected articles and other articles selected from the personal collections of the panelists were also included.

For the clinical practice, 11 questions, previously agreed upon by the panelists, were proposed and widely discussed during the meeting. As reported previously,30 due to the intended international applicability of the Expert Panel Consensus, the discussion was limited to the approved ICI treatment regimens by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), so that the first-line single-agent pembrolizumab and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab in PD-L1 ≥1% NSCLC patients were not considered for panelists’ discussion.

For discussion on clinical research, issues were proposed by each panelist and attributed priorities in the form of high-medium-low according to panel voting.

As in the previous AIOT meeting, live-shared minutes were used to produce a summary report of the meeting, which was agreed by all panelists to serve as the basis to generate the current manuscript. All panelists reviewed the shared statements and approved the final manuscript.

Evidence on the use of first-line immunotherapy in elderly patients with nsclc

Prospective evidence on the use of immunotherapy in elderly patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC is limited. The pivotal first-line clinical trials used different age cut-offs to define subgroups. In particular, the atezolizumab trials (IMpower110, IMpower150, IMpower130)18,22,23 and the chemotherapy plus nivolumab and ipilimumab (CheckMate 9LA)25 evaluated age subgroups using 75 years cut-off. Conversely, the KEYNOTE series of studies with pembrolizumab (KEYNOTE-024, 042, 189),17,31,32 cemiplimab studies,20,27 and the POSEIDON trial26 with chemotherapy plus durvalumab and tremelimumab limited their analysis to 65 years cut-off. Overall, no impact on treatment outcomes was observed when using a 65-year age cut-off through trials. Conversely, the OS benefit of ICI-based treatments was not confirmed in the ≥75-year age subgroup, when evaluated, either as monotherapy or as combination,18,25 but the small proportion (∼10%) of patients in this subgroup makes it impossible to try conclusions on these data from clinical trials.

Of note, the FDA recently presented a pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with pembrolizumab or atezolizumab monotherapy and combinations, investigating outcomes between single-agent ICI and chemo-immunotherapy in PD-L1 ≥50% NSCLC. Comparable outcomes with the two approaches were observed in the overall population, but single-agent immunotherapy showed favorable OS in patients aged ≥75 years.33

To overcome the intrinsic limitations of clinical trials, meta-analyses have been conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of ICIs in elderly patients with NSCLC. Overall, in the pretreated setting, comparable efficacy was observed in older and younger adults treated with ICI monotherapy using a cut-off of 65 years.34, 35, 36, 37 In a meta-analysis of 12 RCTs, OS benefit with mono-immunotherapy was not observed when considering a cut-off of 75 years.36 Of interest, patients aged ≥75 years were reporting lower incidence of grade 3 or higher (G ≥3) adverse events (AEs) compared to those <65 years in a pooled analysis of four RCTs with single-agent ICI by FDA.35

Two prospective studies with nivolumab monotherapy, CheckMate 153 and CheckMate 171 trials, were conducted in the pretreated setting and included patients aged 70 years or older (278 out of 811 in the squamous histology population in CheckMate 171; 99 out of 252 in CheckMate 153).38,39 The incidence of AEs was similar between older and overall patients in both trials (56% versus 50%, and 64% versus 62%, respectively). Comparable survival outcomes were also observed between the older and the overall population.

A small phase II prospective study conducted in Japan enrolled 26 patients aged ≥75 years affected by A-NSCLC with PD-L1 ≥50% and EGFR/ALK WT, who received front-line pembrolizumab.40 Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 9.6 months, median OS was 21.6 months, overall response rate (ORR) was 41.7%, and G ≥3 AEs were 15.4%, comparable with pivotal clinical trial results. No changes in patients’ QoL were observed during treatment. Another small prospective phase II trial was conducted in Spain, enrolling 75 patients aged ≥70 years, with PD-L1 ≥1% and EGFR/ALK WT, treated with pembrolizumab. This study provides a comprehensive geriatric description of the treated population, confirming the safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy.41

A pooled analysis was carried out on 264 patients aged ≥75 years included in the KEYNOTE-010 (pretreated), KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 (front-line) trials.42 Overall, pembrolizumab monotherapy significantly improved survival compared to chemotherapy [median OS 15.7 versus 11.7 months, hazard ratio (HR) 0.76], and the magnitude of benefit was greater in patients with PD-L1 ≥50%. In treatment-naïve elderly patients (n = 93) with PD-L1 ≥50%, median OS with pembrolizumab was 27.4 months, compared to 7.7 months with chemotherapy (HR 0.41). The incidence of AEs appeared lower in the elderly population receiving pembrolizumab than in those treated with chemotherapy (G ≥3 AEs 24.2% versus 61%).42

Several retrospective reports evaluated the outcomes of immunotherapy regimens in the real-world elderly population. In a retrospective study with a small sample size (27 patients out of 98 aged ≥70 years), worse OS was reported in elderly compared to younger patients treated with immunotherapy (median OS 5.3 versus 13 months).43 A larger retrospective cohort of 327 patients with NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥50% treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy included 169 (51.7%) patients aged ≥70 years. No difference in clinical outcomes, OS, ORR, and safety was observed between older and younger patients in this study. Of note, multivariate analysis showed poor PS, and not age, as a factor impacting OS.44

A few retrospective reports included the elderly population receiving chemotherapy plus immunotherapy combinations. A real-world Japanese study included 299 patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC receiving first-line chemo-immunotherapy combination with platinum, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab.45 Forty-three patients were aged ≥75 years. Comparable survival results were obtained in older and younger patients (median PFS 8.9 versus 8.5 months, median OS not reached in both groups). Conversely, the rate of AE-related discontinuation of all treatment components was significantly higher in the elderly population (40% versus 21%, P = 0.012).45

Another real-world study was conducted in the United States in the same setting. Overall, 283 patients were included, 59 (21%) were aged ≥75 years.46 The effectiveness and feasibility of platinum plus pemetrexed plus pembrolizumab combination was consistent in the extended cohort of elderly patients in this analysis (n = 99). Of note, pemetrexed was sooner discontinued compared to pembrolizumab in the elderly population (32% due to toxicity), with time on treatment for pembrolizumab and pemetrexed of 4.9 (3.8-6.2) and 2.8 (2.2-3.6) months, respectively.47

A retrospective trial specifically collected data from 136 elderly (≥75 years) patients with A-NSCLC without EGFR/ALK/ROS1 targetable alterations, treated with first-line pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy (n = 43) or mono-chemotherapy (n = 93). Significant survival benefit was observed with the combination (median PFS 12.5 versus 5.3 months, P < 0.001; median OS not reached versus 21.3, P = 0.037, respectively).48 As expected, higher treatment discontinuation (26% versus 5%) was observed with chemo-immunotherapy.

To date, two phase III trials with first-line immunotherapy specifically addressed to elderly patients (≥70 years) with NSCLC have data presented: the IPSOS study (NCT03191786)49 and the eNERGY study (NCT03351361).50 Both studies were not limited to the elderly population but were extended to poor PS (eNERGY) and more in general platinum-ineligible population (IPSOS). The IPSOS trial was designed to compare atezolizumab monotherapy with single-agent chemotherapy in platinum-unfit patients. Among 453 randomized patients in this trial, 31% were aged ≥80 years. With a median follow-up of 41 months, atezolizumab significantly improved OS compared to chemotherapy (stratified HR 0.78, 95% confidence interval 0.63-0.97, P = 0.028) across key subgroups in this frail population.49 Of note, lower AEs were observed with atezolizumab compared to chemotherapy (16.3% versus 33.3%), and improvements in chest pain, appetite loss, and cough were observed with atezolizumab from baseline.

The eNERGY study compared the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab with carboplatin doublet chemotherapy. In this trial, despite non-significant OS benefit in the overall population, subgroup analysis showed significant OS benefit in elderly patients with PS 0-1 treated with dual-agent immunotherapy compared to chemotherapy (median OS 22.6 versus 11.8 months, P = 0.02), with similar toxicity rates.50

Discussion on clinical practice

Elderly definition

The first issue for panel discussion was related to the validity of the elderly definition in clinical practice to assess patients for immunotherapy treatment (Table 1, questions Q1-Q2).

Table 1.

Expert Panel statements on the use of first-line immunotherapy in elderly patients with A-NSCLC

| Panel questions | Expert conclusions |

|---|---|

| Elderly assessment | |

| Q1. Is ‘elderly’ definition still adequate in the immunotherapy era? | Age is not per se a limitation for treatment selection but should be considered as a surrogate for other factors potentially related to age (ECOG PS, comorbidities). |

| Q2. In patients with A-NSCLC, does age affect your treatment choice with ICIs? |

|

| Single-agent immunotherapy | |

|---|---|

| Q3. Is single-agent immunotherapy feasible and safe in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥50%? | Yes, with available data. |

| Q4. Is single-agent immunotherapy effective in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥50%? | Yes, with available data. |

| Combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy | |

|---|---|

| Q5. In elderly patients with A-NSCLC and squamous histology is combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy feasible and safe? | Yes, but concerned about paclitaxel due to neurotoxicity. |

| Q6. Is combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy effective in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and squamous histology? | Probably yes. We only have exploratory analysis from clinical trial KEYNOTE-407, showing no difference with 65 years cut-off. |

| Q7. In elderly patients with A-NSCLC and non-squamous histology is combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy feasible and safe? | Yes, but concerns are expressed for combined chemotherapy plus immunotherapy in octogenarians. Caution on maintenance with pemetrexed. |

| Q8. Is combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy effective in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and non-squamous histology? | Probably yes. We only have exploratory analysis from clinical trial KEYNOTE-189, showing no difference with 65 years cut-off. |

| Q9. In elderly patients with A-NSCLC is combined chemotherapy plus double immunotherapy feasible and safe? | Yes, considering that the regimen with two cycles of chemo without maintenance pemetrexed could be favorable in the elderly population. |

| Q10. In elderly patients with A-NSCLC is combined chemotherapy plus double immunotherapy effective? | Probably yes, as we cannot avoid treatment in the elderly based only on a small subgroup analysis on ≥75 years cut-off in the CM9LA. |

| Preferred treatments | |

|---|---|

| Q11. In elderly patients with A-NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥50%, how do you choose between single-agent immunotherapy and combined chemo-immunotherapy? | Based on FDA pooled analysis and real-world data, it is reasonable to choose single-agent anti-PD-1/PD-L1, excluding never smokers (irrespective of age). |

A-NSCLC, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; PS, performance status; Q, question.

To all panelists, patients’ age does not represent per se a limitation for adequate treatment selection in A-NSCLC, whichever the age cut-off selected for elderly definition. Indeed, rising chronological age could be an indirect indicator of increasing risk to develop clinical features of frailty that may impact treatment safety. These include major comorbidities, drug polytherapy, worsening Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS, and decreased renal function. As such, panelists agreed that age should be considered mainly as a surrogate for other factors potentially related to age. In this view, the authors discussed the uselessness of an age boundary in a population that is overall getting older, with increasing number of octogenarians. A multifactorial approach is indeed needed to evaluate elderly patients for treatment selection. Overall, panelists considered age not a problem for single-agent anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Conversely, they expressed concerns for combined chemotherapy plus immunotherapy in octogenarians, mainly related to the concerns on toxicities from chemotherapy components (see section ‘Discussion on combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy’, Table 1, Q5-Q7).

Discussion on single-agent immunotherapy

Besides the consensus on elderly definition, the panelists focused the discussion on treatments available in the first-line setting. As first, the safety and efficacy of single-agent immunotherapy in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and high PD-L1 (≥50%) expression were reviewed (Table 1, Q3-Q4).

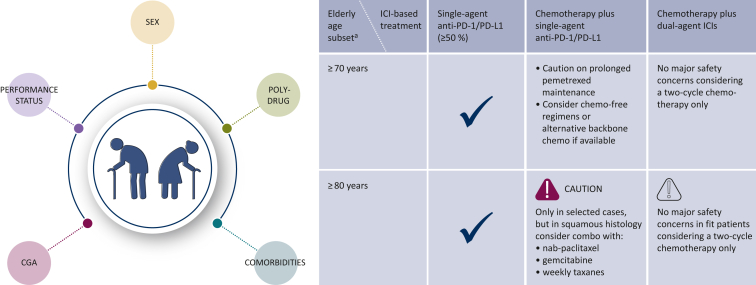

To all panelists, there is no particular concern on the safety of mono-immunotherapy in this setting (Figure 1). This conclusion is supported by the reviewed evidence derived from FDA pooled analysis, meta-analysis, pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE studies, and real-world studies.

Figure 1.

Summary of clinical consensus for ICI treatment in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC.

The figure represents the main factors involved in the evaluation of elderly patients and expert consensus indications for the choice of first-line treatment with ICI-based regimens in the clinical setting.

CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1.

aAbsolute value of age boundaries to be considered within a multifactorial approach.

In the same line, the efficacy of single-agent immunotherapy in the elderly population was confirmed across the same available evidence. Moreover, with the same referral considerations, the panelists observed no differences among the approved agents in this setting, neither in terms of toxicities nor in terms of efficacy.

To strengthen the validity of the consensus, the panelists agreed that, due to concerns on chemotherapy toxicity, single-agent anti-PD-1/PD-L1 should be considered as preferred treatment in elderly patients with A-NSCLC and PD-L1 ≥50%, at least in the absence of dedicated prospective trials to evaluate survival benefit between single-agent and combination treatments.

Discussion on combined chemotherapy plus single-agent immunotherapy

Following the consensus on single-agent immunotherapy, the discussion was focused on the safety and efficacy of the combination of chemotherapy plus single-agent ICIs (Table 1, Q5-Q6-Q7-Q8).

In this setting, the main concerns were expressed by all panelists on the toxicities of the chemotherapy components, in both squamous and non-squamous histology. General concern was expressed for combined chemotherapy plus immunotherapy in octogenarians. In particular, in squamous histology, the major concern was noticed on paclitaxel due to neurotoxicity. Because of this, panelists agreed to prefer, where available, nab-paclitaxel or gemcitabine, or even weekly paclitaxel schedule to better manage chemotherapy toxicity.

In non-squamous histology, caution was recommended on maintenance with pemetrexed. Indeed, renal function in elderly is extremely variable, related to organ failure, but also to frequently low water intake and body mass index composition. As such, signals of early discontinuation from real-world data confirm the alert on prolonged pemetrexed maintenance (Figure 1).

To this extent, data from IPSOS and eNERGY trials support the use of chemo-free regimens in the elderly population, regardless of PD-L1 value.49,50 Furthermore, data about alternative backbone chemotherapy (i.e. for platinum-eligible patients) are recommended topic for research issue (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101192).

With respect to efficacy, besides real-world data confirming activity in patients with non-squamous histology aged ≥75 years, the panelists based their opinion on the exploratory analysis available from pivotal RCTs. In particular, data from KEYNOTE-407 and KEYNOTE-189 showed no difference in treatment efficacy with 65-year age cut-off, but only few elderly patients ≥75 years were included in clinical trials.

Discussion on combined chemotherapy plus double-agent immunotherapy

The option of first-line treatment with chemotherapy plus double-agent immunotherapy, namely anti-PD-1/PD-L1 plus anti-CTLA-4, was considered for panelists’ discussion, based on the results of the CheckMate 9LA and POSEIDON trials25,51 (Table 1, Q9-Q10).

In this setting, the panelists agreed that the absence of benefit deriving from a small subgroup analysis on 10% of patients aged ≥75 years in the CheckMate 9LA trial cannot be used as a backbone to avoid this treatment in the elderly (Figure 1).

In addition, no major safety concerns were expressed with this regimen, considering that a regimen with two cycles of chemotherapy, avoiding maintenance pemetrexed, could be favorable in the elderly population.

As a reminder, they evaluated, based on the results from the eNERGY trial, that the use of dual immunotherapy without chemotherapy in PD-L1 1%-49% could be an option in the United States, where this regimen is approved.

Discussion on preferred treatments

Moving forward, the panelists discussed on preferred treatments in the PD-L1 ≥50% population of elderly patients. In this setting, as also expressed in the ‘Discussion on single-agent immunotherapy’ section, the panelists agreed that, based on FDA pooled analysis and real-world data, it is reasonable to choose single-agent anti-PD-1/PD-L1, with the only exception of never-smoker patients, irrespective of age (Table 1, Q11).

Discussion on clinical research

According to the panelists, the main limitation in the evaluation of the elderly population in NSCLC is related to the lack of consistent data from pivotal clinical trials, including a small proportion of elderly patients, with different age cut-offs and not amenable to be assessed for their functional status. Hence, the panelists prioritized real-world supplementation of data in the elderly population. More in depth, they advocate the adoption of better data quality from real-world databases, to be able to assess all the subsets in the elderly population, including frailty, comorbidities, which may impact tumor response, treatment efficacy, and tolerability with ICI-based regimens (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101192).

In line with the recently presented data from the IPSOS trial, and the elderly subpopulation of the eNERGY trial, with OS benefit of single- or dual-agent ICI over chemotherapy, the panelists agreed that medium priority should be given to increase research on chemotherapy-free regimens (Table 2), or even in clinical trials with combination of single-agent chemotherapy plus immunotherapy. Indeed, single-agent chemotherapy treatments were considered as preferred options for unfit elderly patients in the pre-immunotherapy era.10

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials with ICIs in the front-line setting in elderly patients

| Trial ID | Study phase | Treatment arms | PD-L1 | Age setting (years) | Primary endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04396457 | II | Pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed | <50% | ≥75 | ORR |

| NCT03975114 (MILES-5) | II | CTx → at PD: durvalumab or Durvalumab → at PD: CTx or Durvalumab plus tremelimumab → at PD: CTx | Any | ≥70 | 12 months OS |

| NCT03293680 | II | Pembrolizumab | ≥1% | ≥70 | 12 months OS |

| NCT05273814 | I | Tislelizumab plus bevacizumab and pemetrexed | Any | ≥65 | ORR |

| NCT04533451 | II | Pembrolizumab or Pembrolizumab plus carboplatin plus pemetrexed | Any | ≥70 | AEs |

| NCT03977194 | III | Carboplatin plus paclitaxel or Carboplatin plus paclitaxel plus atezolizumab | Any | ≥70-89 | OS |

| NCT05230888 | Prospective | CGA and VES-13 questionnaire in patients receiving ICIs | Any | ≥70 | irAEs |

AEs, adverse events; CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment; CTx, chemotherapy; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; irAEs, immune-related adverse events; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed cell death-ligand 1; VES, Vulnerable Elders Survey.

To better evaluate the impact of senescence on immunotherapy outcomes, medium priority was also attributed to studies evaluating pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ICIs in the elderly population. In the same line of investigation, the potential role of sex in influencing immunosenescence should be addressed.

In addition, the panelists prompted further relevant aspects related to patients’ QoL as they might affect patients’ survival. Indeed, as elderly patients are often not self-sustaining, the role of caregiver and its relationship with survival deserves investigation. Moreover, due to the potential multiple needs of the elderly population, and burden for patients and their caregivers to sustain multiple outpatient visits, decentralization of patients’ cures should be prioritized, at least for those identified as frail patients.

Conclusions

The use of immunotherapy in the first-line treatment of elderly patients with NSCLC was discussed during the 14th International Experts Panel Meeting, and issues for debate were evaluated. The limited prospective evidence is due to an underrepresentation of the elderly population in clinical trials. However, implementation with data from pooled analysis and real-world experiences helped to reach out a consensus on specific statements related to safety and efficacy of ICI-based regimens in this population.

Despite the fact that efficacy was mainly confirmed across data, no safety concerns were expressed with single-agent immunotherapy, whereas some concerns were pointed out with combinations, especially in octogenarians. In this line, the panel experts agreed on the need to expand clinical research with robust real-world studies, and investigate alternative combination strategies with less toxic potential in the elderly patients with A-NSCLC.

Funding

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Toracica (AIOT) (no grant number).

Disclosure

CG received honoraria as speaker bureau or advisory board member or as consultant from MSD, BMS, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, Menarini, Boehringer, Karyopharm, Eli Lilly, Amgen, Sanofi, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim. SP received education grants, provided consultation, attended advisory boards, and/or provided lectures for the following organizations: AbbVie, AiCME, Amgen, Arcus, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beigene, Biocartis, BioInvent, Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis, Daiichi Sankyo, Debiopharm, ecancer, Eli Lilly, Elsevier, F-Star, Fishawack, Foundation Medicine, Genzyme, Gilead, GSK, Illumina, Imedex, IQVIA, Incyte, iTeos, Janssen, Medscape, Medtoday, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Merck Serono, Merrimack, Mirati, Novartis, Novocure, OncologyEducation, Pharma Mar, Phosplatin Therapeutics, PER, Peerview, Pfizer, PRIME, Regeneron, RMEI, Roche/Genentech, RTP, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, Vaccibody. VV received honoraria or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Foundation Medicine, Curis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Taiho Pharmaceuticals. FdM received honoraria or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Novartis, Takeda, Xcovery, and Roche. IA has declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Yancik R. Cancer burden in the aged: an epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer. 1997;80:1273–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuccarino S., Monacelli F., Antognoli R., et al. Exploring cost-effectiveness of the comprehensive geriatric assessment in geriatric oncology: a narrative review. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:3235. doi: 10.3390/cancers14133235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puts M.T., Hardt J., Monette J., et al. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1133–1163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corre R., Greillier L., Le Caer H., et al. Use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment for the management of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the phase III randomized ESOGIA-GFPC-GECP 08-02 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1476–1483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheitlin M.D. Cardiovascular physiology-changes with aging. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2003;12:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2003.01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mühlberg W., Platt D. Age-dependent changes of the kidneys: pharmacological implications. Gerontology. 1999;45:243–253. doi: 10.1159/000022097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anantharaju A., Feller A., Chedid A. Aging liver. A review. Gerontology. 2002;48:343–353. doi: 10.1159/000065506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dees E.C., O’Reilly S., Goodman S.N., et al. A prospective pharmacologic evaluation of age-related toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2000;18:521–529. doi: 10.3109/07357900009012191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson V., Marano M.A. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1995. Vital Health Stat. 1998;10:1–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gridelli C., Morabito A., Cavanna L., et al. Cisplatin-based first-line treatment of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: joint analysis of MILES-3 and MILES-4 phase III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2585–2592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.8390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morabito A., Piccirillo M.C., Maione P., et al. Effect on quality of life of cisplatin added to single-agent chemotherapy as first-line treatment for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: joint analysis of MILES-3 and MILES-4 randomised phase 3 trials. Lung Cancer. 2019;133:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gridelli C., Balducci L., Ciardiello F., et al. Treatment of elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: results of an international expert panel meeting of the Italian Association of Thoracic Oncology. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borghaei H., Paz-Ares L., Horn L., et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brahmer J., Reckamp K.L., Baas P., et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst R.S., Baas P., Kim D.W., et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rittmeyer A., Barlesi F., Waterkamp D., et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reck M., Rodriguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbst R.S., Giaccone G., de Marinis F., et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1–selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1328–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reck M., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G., et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(21):2339–2349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sezer A., Kilickap S., Gümüş M., et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:592–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadgeel S., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Speranza G., et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1505–1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Socinski M.A., Jotte R.M., Cappuzzo F., et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2288–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West H., McCleod M., Hussein M., et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:924–937. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paz-Ares L., Luft A., Vicente D., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040–2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paz-Ares L., Ciuleanu T.E., Cobo M., et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson M., Cho B.C., Luft A., et al. PL02.01 Durvalumab ± tremelimumab + chemotherapy as first-line treatment for mNSCLC: results from the phase 3 POSEIDON study. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:S844. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gogishvili M., Melkadze T., Makharadze T., et al. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):2374–2380. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01977-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manoussakis M.N., Tzioufas A.G., Silis M.P., et al. High prevalence of anti-cardiolipin and other autoantibodies in a healthy elderly population. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;69:557–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solana R., Tarazona R., Gayoso I., et al. Innate immunosenescence: effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gridelli C., Peters S., Mok T., et al. First-line immunotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients with ECOG performance status 2: results of an International Expert Panel Meeting by the Italian Association of Thoracic Oncology. ESMO Open. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandhi L., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Gadgeel S., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mok T.S.K., Wu Y.L., Kudaba I., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akinboro O., Vallejo J.J., Nakajima E.C., et al. Outcomes of anti–PD-(L)1 therapy with or without chemotherapy (chemo) for first-line (1L) treatment of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with PD-L1 score ≥ 50%: FDA pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:9000–9002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elias R., Giobbie-Hurder A., McCleary N.J., et al. Efficacy of PD-1 & PD-L1 inhibitors in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:26. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marur S., Singh H., Mishra-Kalyani P., et al. FDA analyses of survival in older adults with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in controlled trials of PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies. Semin Oncol. 2018;45:220–225. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L., Sun L., Yu J., et al. Comparison of immune checkpoint inhibitors between older and younger patients with advanced or metastatic lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9853701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim C.M., Lee J.B., Shin S.J., et al. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in elderly patients: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. ESMO Open. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felip E., Ardizzoni A., Ciuleanu T., et al. CheckMate 171: a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer, including ECOG PS 2 and elderly populations. Eur J Cancer. 2020;127:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spigel D.R., McCleod M., Jotte R.M., et al. Safety, efficacy, and patient-reported health-related quality of life and symptom burden with nivolumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, including patients aged 70 years or older or with poor performance status (CheckMate 153) J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:1628–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamai K., Masuda T., Fujitaka K., et al. Phase 2 study of first-line pembrolizumab in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer expressing high PD-L1. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:e21156–e21157. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanco R., Nadal E., Loutfi S., et al. 1317P Survival, quality of life (QoL) and geriatric outcomes of elderly patients (pt) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), treated with pembrolizumab (P) in the first-line setting. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S851. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nosaki K., Saka H., Hosomi Y., et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in elderly patients with PD-L1-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: pooled analysis from the KEYNOTE-010, KEYNOTE-024, and KEYNOTE-042 studies. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corral de la Fuente E., Barquín García A., Saavedra Serrano C., et al. 169P_PR - Benefit of immunotherapy (IT) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in elderly patients (EP) Ann Oncol. 2019;30:ii61–ii62. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grosjean H.A.I., Dolter S., Meyers D.E., et al. Effectiveness and safety of first-line pembrolizumab in older adults with PD-L1 positive non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study of the Alberta Immunotherapy Database. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:4213–4222. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28050357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujimoto D., Miura S., Yoshimura K., et al. A real-world study on the effectiveness and safety of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for nonsquamous NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velcheti V., Hu X., Piperdi B., et al. Real-world outcomes of first-line pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed-carboplatin for metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC at US oncology practices. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88453-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Velcheti V., Hu X., Chen X., et al. 1328P Clinical outcomes of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in non-squamous metastatic NSCLC patients aged 75 years or older at US oncology practices. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S856. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z., Chen Y., Wang Y., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy monotherapy as a first-line treatment in elderly patients (≥75 years old) with non-small-cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.807575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S.M., Schulz C., Prabhash K., et al. LBA11 IPSOS: results from a phase III study of first-line (1L) atezolizumab (atezo) vs single-agent chemotherapy (chemo) in patients (pts) with NSCLC not eligible for a platinum-containing regimen. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:S1418–S1419. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lena H., Monnet I., Bylicki O., et al. Randomized phase III study of nivolumab and ipilimumab versus carboplatin-based doublet in first-line treatment of PS 2 or elderly (≥ 70 years) patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (Energy-GFPC 06-2015 study) J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:9011–9012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson M.L., Cho B.C., Luft A., et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: The Phase III POSEIDON Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1213–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.