Abstract

Linguatula serrata is a worldwide zoonotic food-borne parasite. The parasite is responsible for linguatulosis and poses a concern to human and animal health in endemic regions. This study investigated the hematological changes, oxidant/antioxidant status and immunological responses in goats and sheep naturally infected with L. serrata. Hematological changes, antioxidant enzymes and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured. The level of inter-leukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) mRNA expression was investigated in lymph nodes. According to the hemogram results, eosinophils were significantly increased in the infected goats and sheep, and Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT), hematocrit (HCT), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) were significantly decreased. The levels of MDA and the activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) were significantly higher in infected animals than in non-infected animals. However, the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) was significantly lower in infected animals than in non-infected animals. A comparison of the cytokine mRNA expression in lymph nodes from infected and non-infected animals showed higher cytokine expression in the infected animals. Infection with L. serrata caused microcytic hypochromic and normocytic hypochromic anemia in goats and sheep. The inconsistent results of immunological changes were found in infected goats and sheep. In both animals, oxidative stress occurred and led to an increase in lipid peroxidation. L. serrata created a cytokine microenvironment biased towards the type 2 immune responses.

Key Words: Hematology, Immunological responses, Linguatulosis, Oxidative stress

Introduction

Linguatula serrata (Pentastomida: Linguatulidae) is a worldwide zoonotic food-borne parasite.1-3 It is responsible for linguatulosis and poses a concern to human and animal health in endemic countries. Carnivores and herbivores are definitive and intermediate hosts, respectively. Visceral linguatulosis occurs in humans by ingesting L. serrata eggs through food or water contaminated by nasopharyngeal secretions and feces of the infected final hosts.4 Nasopharyngeal linguatulosis, known as Halzoun syndrome, is caused by accidental ingestion of L. serrata nymphs in intermediate hosts raw or semi-cooked viscera.5 Clinical signs of nasopharyngeal linguatulosis may include moderate to severe pharyngitis, dysphagia, itchiness of the throat and nose, nasal congestion, discharge, sneezing, coughing, salivation, and lacrimation.6

In intermediate hosts, the nymphal stages of the parasite mainly damage the lymph nodes with a wide array of histopathological changes particularly resulting in lymphocyte depletion. This may influence both the intermediate hosts humoral and cell-mediated immune systems and make them susceptible to infectious agents.3,7 Hyperemia, hemorrhage, severe edema, and coagulative and liquefactive necrosis were seen in infected lymph nodes. Infiltration of macrophages, eosinophils, and plasma cells was observed along with a reduction in lymphocytes. It seems that L. serrata nymphs can escape from immune responses and persist in lymph nodes leading to chronic infection. Chronic inflammatory conditions can affect systematic oxidative stress status.8,9

Combining the hematological profile with clinical findings and other diagnostic tests may point to a specific differential diagnosis. The diagnostic value of blood samples remains in their ability to reflect disease effects on the blood cells.10 Thus, understanding the impact of infection on hematological profile factors is essential.

The type 2 immune responses are mediated by various cytokines that regulate diverse cellular functions ranging from antihelminth parasite immunity to allergic inflammation, wound healing and metabolism. A diverse variety of compounds including macroscopic parasites can elicit type 2 immune responses orchestrated by several cell types.11 Initiation of the type 2 responses occurs in the tissue sites where parasites are encountered. The type 2 immune responses are elicited by the concatenated events enforced by type 2 cytokines including interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5. Information about the regulation of immune responses after the infection is critical to understanding of pathogenesis mechanisms. Therefore, this information may be useful in designing diagnostic tests, developing candidate vaccines and monitoring therapeutic effects.12 There is no published information on the hematological, oxidant/antioxidant and immunological status of goats and sheep infected with L. serrata. This study was designed to determine profiles of the hematological, oxidant, antioxidant and immune responses at the mRNA level of some cytokines in goats and sheep naturally infected with L. serrata.

Materials and Methods

Animals and sampling. From September 2018 to March 2019, 791 mesenteric lymph nodes and the blood of goats (n = 335) and sheep (n = 456) were collected from the slaughterhouse in Ahvaz, southwest of Iran. The sample size was calculated based on the population ratio of slaughtered animals at the time of sampling and considering a margin of error of 5.00% and a 95.00% confidence level. In this study, all the sampled animals were healthy based on antemortem and postmortem inspection. Animals with fever or abnormalities in respiration, behavior, gait, posture, structure and conformation, abnormal discharges or protrusions from body openings, and abnormal color and odor were excluded. The infection of L. serrata was diagnosed using two methods: 1) Observation of parasite nymphs in the mesenteric lymph nodes using a stereomicroscope and 2) Hemagglutination test. Animals with positive test and lymph node examination were considered as positive group. Blood samples were collected in the tubes containing di-potassium EDTA (K2EDTA). The separated sera were stored at – 70.00 ˚C until laboratory examinations. In addition, the mesenteric lymph nodes of animals were frozen at – 70.00 ˚C until RNA extraction. All the experiments were carried out in compliance with the requirements of the animal welfare committee of Shahid Chamran University, following the Iranian Veterinary Medical Association guidelines (Ethical Approval No. EE/98.10.6/SCU. AC.IR).

Preparation of somatic antigens of L. serrata. Fifty live nymphs of L. serrata collected from sheep and goat lymph nodes were washed several times in PBS (Exir, Borujerd, Iran) pH 7.40 with gentamycin (40.00 mg L-1; Erfandarou, Tehran, Iran) and then sonicated with a Bandelin sonicator (Bandelin, Berlin, Germany) in 5.00 mL of normal saline. The homogenate was clarified by centrifugation at 7,000 g for 5 min at 4.00 ˚C and the supernatant was stored at – 70.00 ˚C until use.13

Indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA). The indirect hemagglutination test was used to detect antibodies against L. serrata. In this experiment somatic antigens of L. serrata were used. Sheep erythrocytes were washed thrice in PBS (pH 7.20). The mixture of RBC 1.00% suspension and the diluted tannic acid solution (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) (2.50 mg tannic acid + 50.00 mL PBS) were mixed and incubated at 37.00 ˚C for 1 hr. The cells were centrifuged at 4,000 g for 5 min (Hettich, Kirchlengern, Germany) and washed twice with PBS. They were then transferred to three tubes. Antigens were added to two of them. After overnight, the tubes were washed three times with PBS. Bovine serum albumin (Sigma) was added to the tubes as the blocker. Finally, 50.00 µL of PBS, sample serum and RBC with and without antigen were used to measure the total antibody. For measuring Immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels, 2-mercaptoethanol buffers (Sigma) were used instead of PBS. The IHA test was performed in serial serum dilutions beginning at 1: 2 to 1: 256. Sera with a titer of ≥ 1: 8 were considered positive.13

Hematological examination. Complete blood counts including total erythrocyte count (RBC), platelet count (PLT), hematocrit value (HCT), hemoglobin concentration (Hb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), total white blood cells (WBC) and red cell distribution width (RDW) were determined by hematology analyzer (CAL 8000; Mindray, Shenzhen, China). Differential leukocyte counts were also estimated by evaluating the Giemsa-stained blood smears.

Oxidant/antioxidant test. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme activity was measured using a commercial kit (Randox, Antrim, UK). For measuring the activity of SOD, superoxide radicals generated by xanthine oxidase reaction converted 1-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(−4 nitrophenol)-5-phenyltertrazoliumchloride quantitatively to a formazan dye (Ransel kit; Randox Lab, Antrim, UK). Conversion of superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide by superoxide dismutase inhibited dye formation and measured superoxide dismutase activity. The activity of the enzyme in the serum was expressed as U mL-1. Catalase activity was measured in serum samples by the method described by Koroliuk et al.14 To estimate the catalase activity, Tris-HCl buffer (0.05 mmol L-1, pH 7.80; Sigma) containing 10.00 mmol L-1 hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) was made and mixed with the sample. The mixture was incubated for 10 min, then ammonium molybdate (Sigma) 4.00% was added. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 410 nm by a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek, Winooski, USA). Enzyme activity was reported in U mL-1 protein. The activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx) was measured with a commercial kit (Randox). The GPx reduces Cumene hydro-peroxide while oxidizing GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). In the presence of glutathione reductase, GSSG was reduced to GSH with concomitant oxidation of NADPH to NADP+. The decrease in NADPH (measured at 340 nm) was proportionate to GPx activity. GPx activity was calculated according to the manufacturer's instruction and expressed in U mL-1. Lipid peroxidation was determined as malondialdehyde (MDA) by estimation of the thio-barbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) according to Mihara and Uchiyama.15 The sera, 25.00 µL were mixed with 250 µL of 20.00% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma) and 100 µL of 0.60% thiobarbituric acid and heated in a boiling water bath for 30 min. The mixtures were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min to remove impurities and clear the supernatant. A volume of 200 μL of the supernatant of each sample was transferred to a 96-well plate and the absorbance of the samples was measured at 535 nm by a spectrophotometer (Bio-Tek). Lipid peroxidation was expressed as MDA μmol mL-1 serum.

RNA extraction and analysis of cytokine mRNA expression. Total RNA was extracted from collected lymph nodes homogenized in the Trizol Reagent (Cinna-Gen, Tehran, Iran). Messenger RNA (mRNA) enrichment was performed using the RNeasy mini kit (CinnaGen). The RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor (Applied Biosystems, Waltham USA). The reaction mixtures were placed in a thermal cycler (T100; Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) with the following thermal steps: 25.00 ˚C for 10 min, 37.00 ˚C for 120 min and 85.00 ˚C for 5 min.16 Real-Time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) amplification was performed using specific primers for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (F: 5ʹ- CAGAAGTTGCTTGTGCCTCA-3ʹ and R: 5ʹ-TGAGAAGAGGAC CTGAGTGTT-3ʹ); IL-4 (F: 5'- TGAGCTTAGGCGTATCTACAG G-3' and R: 5'-CAT TCACAGAACAGGTCTTGCT-3'); IL-5 (F: 5´- GAGCTGCTTATGTTTGTGCCA-3´and R: 5´- GGAATCATC AAGTTCCCATCACC-3´); IL-10 (F: 5´- GACTTTAAGGGTTAC CTG GGTTG-3´and R: 5´- TTGATGTCAGGCCCATGGTT-3´); and IL-2 (F: 5´- AAGCTCTA CGGGGAACACAA-3´ and R: 5´-ATTCTGTAGCGTTAACCTTGGG-3´) genes. PCR efficiency was determined for each target gene and a melting curve analysis for each target gene was performed to ensure that a single gene product was amplified. The Real-time PCR assay reaction mixture (10.00 μL) containing 5.00 μL of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.25 μL of each primer (Table 1; 10.00 mM), 2.00 μL of cDNA template and 2.00 μL of RNase-free water were amplified using the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The thermal conditions were as follow: Initial denaturation at 95.00 ˚C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95.00 ˚C for 15 sec, annealing at 58.00 ˚C for 30 sec and a final extension at 72.00 ˚C for 15 sec. To confirm that there was no background contamination, a cDNA template-free negative control was included in each run and the gene for GAPDH (F: 5´- CTGGAGAAACCTGC CAAGTATG-3´ and R: 5´-AGAGTGAGTGTCGCTGTTGA-3´) was used as an internal control since it ws constitutively expressed under a wide range of conditions.16

Table 1.

Hematologic results as mean ± SE in infected and non-infected goats with L. serrata

| Parameters | Infected (n = 15) | Non-infected (n = 10) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×10 3 μL -1 ) | 12.33 ± 3.19a | 11.09 ± 1.41a | 0.318 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 56.20 ± 4.75 a | 54.00 ± 4.74a | 0.422 |

| Monocyte (%) | 0.70 ± 0.48 a | 0.40 ± 0.54a | 0.332 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 2.70 ± 1.25 a | 0.20 ± 0.44b | 0.000 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 40.40 ± 5.16 a | 45.40 ± 4.98a | 0.106 |

| RBC (×10 6 μL -1 ) | 11.38 ± 1.31a | 15.54 ± 1.83b | 0.004 |

| Hemoglobin (g dL -1 ) | 5.52 ± 0.65 a | 10.00 ± 1.07b | 0.000 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 16.49 ± 2.99 a | 29.10 ± 4.12b | 0.001 |

| MCV (fl) | 14.50 ± 1.79 a | 21.69 ± 2.41b | 0.001 |

| MCH (pg) | 4.82 ± 0.42 a | 6.66 ± 0.68b | 0.002 |

| MCHC (g dL -1 ) | 33.80 ± 2.93 a | 35.18 ± 3.17a | 0.441 |

| RDW (%) | 21.27 ± 1.82 a | 16.32 ± 1.55b | 0.000 |

| Platelet (×10 3 μL -1 ) | 245.60 ± 26.61a | 230.80 ± 23.33 a | 0.212 |

WBC: white blood cells, RBC: red blood cell, MCV: mean corpuscular volume, MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC: mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and RDW: red cell distribution width.

ab Values in rows with different lower-case superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Calculation of the relative gene expression. The threshold for positivity of real-time PCR was determined based on the expression of the specific mRNAs in the lymph node of non-infected goats and sheep using the equation 2-ΔΔCt. The relative fold changes in the expression of genes were determined in three replications and values > 2 or < –2 was considered as a measure for increase or decrease in the level of gene expression.

Statistical analysis. Data were analyzed using the two-tailed independent t-test procedure when samples had a normal distribution and Mann-Whitney tests were used when the distribution was not normal. All analyses were performed using SPSS Software (version 20.00; IBM Corp., Armonk, USA). The significance levels were expressed at a 95.00% confidence level (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

Prevalence of L. serrata infection in animals. Based on the observation of nymphs in the mesenteric lymph nodes, the overall prevalence of L. serrata in goats and sheep was 10.70% and 5.70%, respectively. The mean intensity of infection in goats and sheep was 10.60 and 4.90 nymph per lymph node, respectively.

Hematologic assessment. The results of hematological parameters are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The comparison between infected and non-infected goats showed a significant increase in the percentage of eosinophils and red cell distribution width (RDW) in the infected group (p = 0.00). Furthermore, a significant decrease in total erythrocyte count (RBC) (p = 0.004), hemoglobin (HGB) (p = 0.00), HCT (p = 0.001), MCV (p = 0.001), MCH (p = 0.002) in the infected group was obtained. For other hematological factors, non-significant differences were detected (p > 0.05; Table 1). Hemogram results in sheep revealed a significant increase in the percentage of eosinophils and a significant decrease in HGB (p = 0.019), HCT (p = 0.019) and MCHC (p = 0.002) in the infected group compared to the non-infected group. The level of other blood parameters revealed no significant alterations in the infected group compared to the non-infected group (p > 0.05; Table 2). In addition, the level of basophil was zero in all samples.

Table 2.

Hematologic results as mean ± SE in infected and non-infected sheep with L. serrata

| Parameters | Infected (n = 15) | Non-infected (n = 10) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×10 3 μL -1 ) | 10.27 ± 3.82a | 10.18 ± 1.39 a | 0.948 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 53.40 ±11.04a | 54.20 ± 7.36 a | 0.871 |

| Monocyte (%) | 0.50 ± 0.70 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.052 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 3.50 ± 1.26a | 0.20 ± 0.44b | 0.000 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 42.70 ±10.88a | 45.60 ± 7.70 a | 0.563 |

| RBC (×10 3 μL -1 ) | 8.93 ± 1.24 a | 10.67 ± 2.06 a | 0.139 |

| Hemoglobin (g dL -1 ) | 7.87 ± 1.24a | 11.20 ± 2.09b | 0.019 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 27.07 ± 3.71a | 35.18 ± 5.14b | 0.019 |

| MCV (fl) | 30.41 ± 1.85 a | 31.67 ± 4.25 a | 0.554 |

| MCH (pg) | 8.76 ± 0.44 a | 9.82 ± 1.60 a | 0.215 |

| MCHC (g dL -1 ) | 28.96 ± 1.31a | 35.16 ± 2.26b | 0.002 |

| RDW (%) | 16.73 ± 0.76 a | 17.00 ± 0.95 a | 0.599 |

| Platelet (×10 3 μL -1 ) | 202.00 ± 57.12 a | 233.40 ± 34.73 a | 0.212 |

WBC: white blood cells, RBC: red blood cell, MCV: mean corpuscular volume, MCH: mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mchc: Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and RDW: red cell distribution width.

ab Values in rows with different lower-case superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Oxidant/antioxidant assessment. The amount of MDA and activities of GPx, SOD and CAT are shown in Table 3. The level of MDA and the activity of GPx in the infected goats and sheep were significantly higher than in the non-infected animals (p = 0.00). The activity of SOD (sheep and goats p = 0.00 and p = 0.001, respectively) and CAT (p = 0.00) were significantly lower in the infected groups than in the non-infected animals.

Table 3.

Oxidant/antioxidant status results as mean ± SE in non-infected and infected animals with L. serrata

| Animals | Parameters | Infected (n = 15) | Non-infected (n = 10) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goats | SOD (U mL -1 ) | 3.18 ± 0.82a | 9.76 ± 1.75b | 0.001 |

| CAT (U mL -1 ) | 1.20 ± 0.45a | 3.30 ± 0.42b | 0.000 | |

| GPX (U mL -1 ) | 3.99 ± 0.55a | 2.19 ± 0.55b | 0.000 | |

| MDA (nmol mL -1 ) | 5.87 ± 1.37a | 1.91 ± 0.51b | 0.000 | |

| Sheep | SOD (U mL -1 ) | 2.60 ± 0.73a | 12.41 ± 0.72b | 0.000 |

| CAT (U mL -1 ) | 0.91 ± 0.27a | 3.40 ± 0.41b | 0.000 | |

| GPX (U mL -1 ) | 4.70 ± 1.22a | 2.13 ± 0.50b | 0.000 | |

| MDA (nmol mL -1 ) | 5.69 ± 1.48a | 1.69 ± 0.28b | 0.000 |

SOD: Superoxide dismutase, CAT; Catalase, GPx: glutathione peroxidase, MDA: malondialdehyde.

ab Values in rows with different lower-case superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

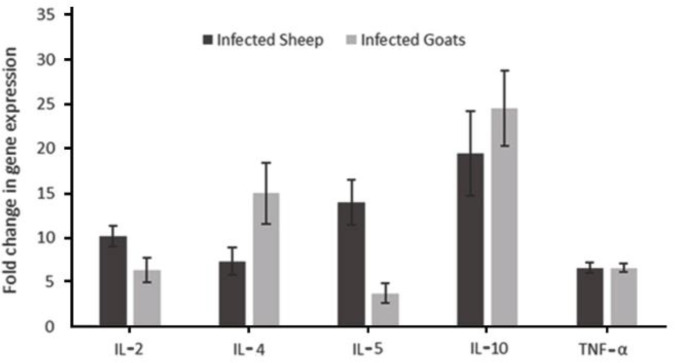

Gene expression. The mRNA cytokine expression in infected and non-infected lymph node samples showed a trend toward higher cytokine expression in infected samples as illustrated in Figure 1. The cytokines expression was significantly increased in infected groups. However, this difference was more significant regarding TNF-α in goats and sheep, IL-4 in goats, and IL-2, IL-5 and IL-10 in sheep.

Fig. 1.

The relative fold change in the expression of cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and TNFα) in sheep and goats infected with L. serrata

Discussion

There is a paucity of data on the effect of L. serrata infection on hematological, oxidant/antioxidant status and immunological responses in goats and sheep. The present study was novel in its analyses of the parameters evaluated in naturally L. serrata-infected goats and sheep. Based on the results of RBC indices in infected goats, the anemia was diagnosed as microcytic hypo-chromic anemia because both MCV and hemoglobin were decreased. However, the anemia was normocytic hypo-chromic because of normal MCV and low hemoglobin value in sheep. This finding could be related to the higher intensity of infection in goats. Prolonged infection or inflammation often leads to the development of anemia (anemia of chronic disease). Anemia of chronic disease is usually mild to moderate anemia that develops in the setting of many infections, inflammatory disorders and some malignancies.17 In anemia of chronic diseases like linguatulosis the erythrocytes are usually normocytic, however, can be mildly microcytic. Most chronic bacterial, fungal, viral or parasitic infections with systemic manifestations can cause anemia of chronic disease. The other factors variably contribute to anemia of chronic disease include increased destruction of erythrocytes (hemolytic anemia), suppression of the maturation of erythrocyte precursors by cytokines and cytokine-mediated interference with erythropoietin production or signaling. Several biochemical and histo-chemical observations support the importance of iron restriction as a key mechanism in the anemia of chronic disease.17 At the molecular level, cytokine-stimulated overproduction of hepcidin causes the endocytosis and degradation of the iron efflux channel ferroportin decreasing the delivery of iron from macrophages and enterocytes to plasma. Hypoferremia ensues and restricts the supply of iron to hemoglobin synthesis eventually resulting in anemia.18 The eosinophils may increase in different disorders.19 Parasitic diseases, especially parasitic tissue infections are among the major problems in this context.20,21 In this study, eosinophil levels were increased in infected compared to the non-infected goats and sheep. The infection of the animal with internal or external parasites is associated with excessive release of free radicals which may be attributed to a decrease in the nutrients availed by the body to synthesize antioxidants and may be due to the destruction of cells produced by the activity of the parasites. The antioxidant system has a cellular protective action against oxidative stress of cells, organs, and tissue damage that results from parasitic invasion.22 Free radicals are involved in the patho-genesis of most of the parasitic infections that are reported to be associated with lipid peroxidation.23 The antioxidant systems play different defense lines from the prevention of the early production of reactive species to the recovery of propagating radicals. In the first line of defense, enzymes such as SOD, CAT and GPx are involved. Lipid peroxidation is one of the best indicators of the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that induces systemic biological damage.24 In the lymph nodes of goats and sheep with higher parasite burdens and more injuries a significant decrease was observed in the activities of SOD and CAT in serum. In addition, the GPX and MDA levels in infected animals were significantly higher than in non-infected animals. Low levels of SOD and CAT activity in infected animals might be related to oxidative stress which caused a marked increase in lipid peroxidation and MDA levels. This finding could represent another aspect of the pathogenesis of L. serrata in goats and sheep. It seems the parasitic infection causes ROS production leading to the reduction of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT. It also appears that an increase in the oxidative crisis in linguatulosis will increase some antioxidants including GPx to combat this stress.

The type 2 immune response is critical for host defense against large parasites. Thus, a balanced type 2 immune response must be achieved to protect against invading pathogens while avoiding immunopathology.11 The classical model of type 2 immunity mainly involves the differentiation of type 2 T helper (Th2) cells and the production of distinct type 2 cytokines including IL-4 and IL-5. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) were recently recognized as another important source of type 2 cytokines. Studies have demonstrated that cytokines such as IL-2, could enhance ILC2 proliferation. Indeed, T cells collaborate with ILC2s to maintain M2 macrophages during worm infection presumably through IL-2 secretion.11 Although eosinophils, mast cells and basophils can also express type 2 cytokines and participate in type 2 immune responses to various degrees, the production of type 2 cytokines by the lymphoid lineages, Th2 cells and ILC2s, in particular, is the central event during the type 2 immune response. 25

The cytokine TNF-α exhibits both protective immunity and pathogenicity. Furthermore, TNF-α is necessary for homing Th2 cells to the site of inflammation.26

According to the issues mentioned above and the role of type 2 immune response, specifically Th2 in the immune response to the parasites, in this study, we tried to evaluate the amount of mRNA expression of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and TNF-α. As shown in Fig 1, all the factors in the infected samples were significantly higher than in the non-infected samples. However, this rate was much higher in TNF-α than in other elements. Therefore, we suggested that L. serrata created a cytokine micro-environment in small ruminants that led to a type 2 immune response and enhanced the parasite pathogenesis at the site of infection. Different studies on helminth parasites have indicated Th2 dominant immune responses that promoted the stimulation of humoral immune responses which were responsible for parasite evasion from immune surveillance.27,28

We found inconsistent immunological changes (bactericidal, lysozyme and complement activities) between goats and sheep due to the differences in the immune system of the animals. In both animals, oxidative stress occurred and led to an increase in lipid peroxidation. L. serrata initiated the type 2 response in lymph nodes where parasites were encountered. Imbalanced type 2 immune response enhanced the parasite pathogenesis in the lymph nodes in small ruminants. L. serrata infection caused anemia, oxidative stress and type 2 immune responses in goats and sheep.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz Research Council (Grant No: Scu.vP98.370).

References

- 1.Hajipour N, Tavassoli M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of Linguatula serrata infection in definitive and intermediate hosts in Iran and other countries: A systematic review. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2019;16:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehlhorn H. Encyclopedic reference of parasitology. 3rd ed. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 1114–1118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam R, Anisuzzaman , Hossain MS, et al. Linguatula serrata, a food-borne zoonotic parasite, in livestock in Bangladesh: Some pathologic and epidemiologic aspects. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2018;13:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yılmaz H, Cengiz ZT, Ciçek M, et al. A nasopharyngeal human infestation caused by Linguatula serrate nymphs in Van province: a case report. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2011;35(1):47–49. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yazdani R, Sharifi I, Bamorovat M, et al. Human linguatulosis caused by Linguatula serrata in the city of Kerman, south-eastern Iran- case report. Iran J Parasitol. 2014;9(2):282–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabibian H, Yousofi Darani H, Bahadoran-Bagh-Badorani M, et al. A case report of Linguatula serrata infestation from rural area of Isfahan city, Iran. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:42 . doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajipour N, Ketzis J, Esmaeilnejad B, et al. Pathological characteristics of Linguatula serrata (aberrant arthropod) infestation in sheep and factors associated with prevalence in Iran. Prev Vet Med. 2019;15(172):104781. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azizi H, Nourani H, Moradi A. Infestation and pathological lesions of some lymph nodes induced by Linguatula serrata nymphs in sheep slaughtered in Shahrekord Area (Southwest Iran) Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2015;5(7):574–578. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yakhchali M, Tehrani A. The mesenteric lymph nodes pathology by nymph stage of Linguatula serrata in cattle. J Res Appl Basic Med Sci. 2019;5(2):111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones ML, Allison RW. Evaluation of the ruminant complete blood cell count. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2007;23(3):377–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurram RK, Zhu J. Orchestration between ILC2s and Th2 cells in shaping type 2 immune responses. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16(3):225–235. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klose CSN, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:765–774. doi: 10.1038/ni.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alborzi AR, Hosseini M, Bahrami S, et al. Evaluation of complement and lysozyme activity and determination of antibody titers in the sera of Linguatula serrata -infected intermediate hosts by indirect hemagglutination [Persian] Vet Res Biol Prod (Pajouhesh-va-Sazandegi) 2022;35(2):49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koroliuk MA, Ivanova LI, Maĭorova IG, et al. A method of determining catalase activity [Russian] Lab Delo. 1988;1:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihara M, Uchiyama M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal Biochem. 1978;86(1):271–278. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forlenza M, Kaiser T, Savelkoul HF, et al. The use of real-time quantitative PCR for the analysis of cytokine mRNA levels. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;820:7–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-439-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madu AJ, Ughasoro MD. Anaemia of chronic disease: An in-depth review. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(1):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000452104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nemeth E, Ganz T. The role of hepcidin in iron metabolism. Acta Haematol. 2009;122(2-3):78–86. doi: 10.1159/000243791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shomali W, Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(10):1149–1167. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cojocariu IE, Bahnea R, Luca C, et al. Clinical and biological features of adult toxocariasis. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2012;116(4):1162–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovalszki A, Weller PF. Eosinophilia. Prim Care. 2016;43(4):607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dede S, Değer Y, Kahraman T, et al. Oxidation products of nitric oxide and the concentrations of antioxidant vitamins in parasitized goats. Acta Vet Brno. 2002;71:341–345. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abd Ellah MR. Involvement of free radicals in parasitic infestations. J Appl Anim Res. 2013;41(1):69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popova MP, Popov CS. Damage to subcellular structures evoked by lipid peroxidation. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2002;57(3-4):361–365. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-3-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouchery T, Kyle R, Camberis M, et al. ILC2s and T cells cooperate to ensure maintenance of M2 macrophages for lung immunity against hookworms. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6970. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajavelu P, Das SD. Th2-type immune response observed in healthy individuals to sonicate antigen prepared from the most prevalent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain with single copy of IS6110. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;45(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muñoz-Carrillo JL, Contreras-Cordero JF, Gutiérrez-Coronado O, et al. Cytokine profiling plays a crucial role in activating immune system to clear infectious pathogens. In: Tyagi K, Bisen P, editors. Immune response activation and immunomodulation. London, UK: Intech Open; 2018. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]