Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of liraglutide 3.0 mg, a glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist, for binge eating disorder (BED).

Methods

Adults with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 27 kg/m2 enrolled in a pilot, 17‐week double‐blind, randomized controlled trial of liraglutide 3.0 mg/day for BED. The primary outcome was number of objective binge episodes (OBEs)/week. Binge remission, weight change, and psychosocial variables were secondary outcomes. Mixed effect models were used for continuous variables, and generalized estimating equations were used for remission rates.

Results

Participants (n = 27) were 44.2 ± 10.6 years; BMI = 37.9 ± 11.8 kg/m2; 63% women; and 59% White and 41% Black. At baseline, the liraglutide group (n = 13) reported 4.7 ± 0.7 OBEs/week, compared with 3.0 ± 0.7 OBEs/week for the placebo group, p = 0.07. At week 17, OBEs/week decreased by 4.0 ± 0.6 in liraglutide participants and by 2.5 ± 0.5 in placebo participants (p = 0.37, mean difference = 1.2, 95% confidence interval 1.3, 2.0). BED remission rates of 44% and 36%, respectively, did not differ. Percent weight loss was significantly greater in the liraglutide versus the placebo group (5.2 ± 1.0% vs. 0.9 ± 0.7%, p = 0.005).

Conclusion

Participants in both groups reported reductions in OBEs, with the liraglutide group showing clinically meaningful weight loss. A pharmacy medication dispensing error was a significant limitation of this study. Further research on liraglutide and other GLP‐1 agonists for BED is warranted.

Keywords: binge eating disorder, binge episodes, eating disorder, liraglutide, loss of control eating, weight loss medication

1. INTRODUCTION

Binge eating disorder (BED) is a serious psychiatric condition that is characterized by the consumption of objectively large amounts of food in a discrete period, accompanied by a loss of control over eating, occurring on average at least once per week. 1 During binge episodes, persons with BED typically eat more rapidly than usual, eat until uncomfortably full, eat large amounts when not physically hungry, eat alone due to embarrassment, and feel disgust or upset after these eating episodes. 1 BED can occur at any body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), but the odds of having obesity are increased with BED. 2 Individuals with BED report clinically significant weight increases in the year prior to seeking BED treatment, 3 and more weight gain in the past year compared to persons without BED. 4 BED is also associated with significant health complications independent of BMI, including increased risk for chronic neck and back pain, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic headaches 5 as well as poorer quality of life. 6

Cognitive behavior therapy is considered the most effective treatment for BED, but it is expensive, time‐intensive, and not available in many geographical regions. 7 It also typically does not produce significant weight loss. 7 Lisdexamfetamine is the only medication currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of BED, 8 although other medications, including selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitors, 9 , 10 topiramate, 11 and sibutramine 12 have been tested for this disorder. McElroy et al. 8 found significant mean reductions with lisdexamfetamine (at 50 and 70 mg/day) of 4.1 binge episodes per week and a weight loss of 4.9 kg compared to mean reductions of 3.3 episodes per week and a weight loss of 0.1 kg for placebo. The percentage of participants achieving remission from binge episodes was 50% in the treatment groups and 42% for those on placebo. 8 However, as a stimulant, lisdexamfetamine poses the potential for abuse, which may be problematic for a significant proportion of people with BED, given the elevated rate of substance use disorders in this population. 13 , 14

Liraglutide is a glucagon‐like‐peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency for chronic weight management as an adjunct to a reduced‐calorie diet and increased physical activity. GLP‐1 slows gastric emptying, thus increasing satiety, 15 and helps reduce energy intake by affecting appetite regulation in the brain. 16 Liraglutide 3.0 mg/day has been shown to produce greater reductions in dietary disinhibition, global eating disorder psychopathology, and shape concerns in persons with obesity who were also receiving a behavioral weight loss intervention, as compared to those receiving behavioral weight loss intervention alone. 17 To our knowledge, Robert et al. 18 have published the only study testing liraglutide in a population who scored above the clinical cut point for binge‐eating features [assessed by self‐report on the Binge Eating Scale (BES)]. 19 That study was an open‐label administration of liraglutide 1.8 mg/day with minimal diet and lifestyle advice, as compared to diet and lifestyle advice alone. Participants taking liraglutide significantly decreased their BES scores at 6 and 12 weeks (study end). These participants also showed significant decreases in weight (95.5 to 90.1 kg), waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, and total cholesterol. However, this study had several weaknesses, including its lack of a placebo control group, its reliance on a global self‐report measure of binge‐eating (instead of an interview‐based measure of number of binge episodes across treatment), and its use of the 1.8 mg/day dose of liraglutide as compared to the 3.0 mg/day dose approved for weight loss.

The present study was a 17‐week randomized, double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial to test the efficacy of liraglutide 3.0 mg/day for the treatment of BED. Our primary hypothesis was that participants randomized to liraglutide would report greater reductions in the number of binge episodes per week. Secondary hypotheses included that liraglutide‐treated participants, compared with placebo, would achieve a higher percentage of remission from binge episodes, as well as greater weight loss, global BED symptom improvement, and improvement in other eating‐related behaviors, quality of life, and mood.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Persons aged 21–70 years old with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2, the threshold for prescribing liraglutide 3.0 mg for weight management, were recruited by print, television, radio and Internet advertisements aimed at individuals wanting treatment for BED. Individuals were screened by phone to assess interest in the trial and eligibility criteria. They were then invited for an in‐person assessment visit where they completed informed consent, an evaluation of BED and relevant psychosocial symptoms, and a medical history and physical examination. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania's Institutional Review Board and was conducted under the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (Common Rule).

Participants were required to meet full criteria for BED, 1 as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (interview version, 16th edition). 20 They could not have more than moderate depressive symptoms, assessed by a score of 15 or greater on the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) 21 or recent suicidality [defined as history of suicidal ideation and behavior in the past 5 years, as assessed at screening by a score of 4 or 5 on the Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C‐SSRS)]. 22 Other exclusion criteria included: women who were pregnant, nursing, or not using adequate contraceptive measures; personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mm Hg); types 1 or 2 diabetes; recent, uncontrolled medical or psychiatric diseases, including current anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa; use in past 3 months of medications known to induce significant weight loss or weight gain; loss of ≥10 lb of body weight within the past 3 months; known or suspected allergy to trial medication; and history of pancreatitis. 23

2.2. Screening assessment

An overview of the study visits is provided in Table 1. During the screening visit, BED was assessed with the EDE 20 including the number of objective binge episodes (OBEs) (i.e., consuming unusually large quantities of food with a subjective loss of control) and any inappropriate compensatory behaviors that have occurred in the previous 28 days. The EDE yields four subscales rated on 7‐point scales (0–6) with higher scores indicating greater pathology: Dietary Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern. A Global EDE score is averaged across these four subscales. The EDE was administered by a trained rater at baseline and week 17 (end of treatment). The binge‐eating section of the EDE also was used to assess frequency of binge episodes at each study visit.

TABLE 1.

Timeline of procedures and number of participants with data eligible to be included in the statistical analyses

|

Note: Shaded weeks were formal assessment weeks. Data regarding binge episodes, weight, vital signs, mood and suicide risk, and other self‐reported outcomes were collected at each medication visit.

aOne additional participant provided data but was censored due to the medication distribution error.

bThree additional participants provided data but were censored due to the medication distribution error.

cFour additional participants provided data but were censored due to the medication distribution error.

The Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.), a brief, structured interview based on the DSM IV was used to screen for other psychiatric diagnoses at baseline 24 to assess the psychiatric exclusion criteria.

A medical history and a physical examination were completed to determine medical eligibility. Body weight was measured in light clothing, without shoes using a digital scale (Tanita BWB800). Height was measured using a stadiometer and waist circumference using a standardized procedure. 25 This exam included an electrocardiogram (EKG), blood pressure and pulse rate, and fasting blood test to determine that final eligibility criteria were met. Safety screening labs included a comprehensive metabolic panel (including glucose), lipids, hemoglobin A1c, and a urine pregnancy test (for females of child‐bearing age).

Upon successful completion of the screening visit, a 2‐week run‐in period was used to confirm that participants continued to experience at least one binge episode per week before being randomized. Participants were asked to monitor their binge episodes and were contacted by study staff once per week for 2 weeks to report their frequency. Those still meeting criteria were invited to a randomization visit.

2.3. Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned to the two interventions in equal numbers by the Investigational Drug Service of the University of Pennsylvania. Participants and investigators were masked to randomization. The Investigational Drug Service received the liraglutide (6.0 mg/ml) and matching placebo study drug directly from the manufacturer (Novo Nordisk A/S). A 5‐week supply (1 box) of the medication or placebo was distributed on 4 occasions (randomization/week 0 and weeks 5, 9, and 13) to each participant.

2.4. Intervention

Liraglutide (6.0 mg/ml) and matching placebo were provided as pre‐filled, disposable, injection pens (Novo Nordisk A/S). A study physician or nurse practitioner instructed participants how to properly perform daily subcutaneous injections into their abdomen, thigh, or upper arm, and participants were given an instruction card detailing how to administer the medication. To reduce the likelihood of gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting), the medication was initiated at 0.6 mg/day for 1 week, and then increased by 0.6 mg/day in weekly intervals until a dose of 3 mg/day was reached (over the course of 5 weeks). If participants missed more than 3 days, they were to initiate therapy at 0.6 mg/day again to avoid gastrointestinal symptoms. Participants who did not tolerate an increased dose during escalation had a delayed dose escalation by up to 7 days. This is the same dosing regimen as that used for obesity treatment. Participants then continued administration of the injections for an additional 12 weeks at full strength.

2.5. Outcome measures

After randomization at week 0, participants returned for assessment visits at weeks 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, and 17 (Table 1). At each assessment, the binge episode section of the EDE was used to assess binge frequency, the primary outcome, in the past 14 days. The rater then used the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement scale (CGII) 26 to rate the level of overall symptom improvement based on the information gathered at the visit. This is a 7‐point scale ranging from 1 to 7, with 1—very much improved, 4—no change, and 7—very much worsened. Each visit also included measurements of weight, waist circumference, and vital signs, as well as participants' response, adherence, and adverse effects related to the medication, and assessment of suicidality by the C‐SSRS. The following surveys were also given at each visit: the PHQ‐9 was used to assess mood, and the Quality of Life, Satisfaction and Enjoyment Scale 27 was used to measure a broad range of quality‐of‐life items. The Eating Inventory (EI) 28 consists of 51 items and was used to assess three factors: Cognitive Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger at baseline and week 17. Scores increase positively with endorsement of items for each factor.

Participants were compensated for their transportation to and completion of the assessment visits.

2.6. Power analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted to detect a clinically relevant change in binge episodes of 1.6 per week (d = 0.39) with a standard deviation of 4.1 29 and an interclass correlation parameter equal to 0.59 estimated based on data collected from similar populations at our Center. 30 Based on these values, we estimated that an initial sample of 152 participants (76 per group) with a 15% attrition rate would give 80% power at alpha = 0.05 to detect a difference between the group in reduction in binge episodes. All secondary outcomes were considered exploratory and were evaluated at alpha = 0.05.

2.7. Statistical analyses

The number of participants eligible for statistical analysis was adversely affected by an administrative error concerning medication allocation. After the first year of the trial, the Investigational Drug Service informed the investigators that the randomization key had been interpreted incorrectly, resulting in some participants receiving medication refills that were not consistent with their assigned condition. Of the 21 participants enrolled prior to that time, 15 had been switched between placebo and liraglutide at least once during the 17‐week treatment period, and 6 received the same agent consistently.

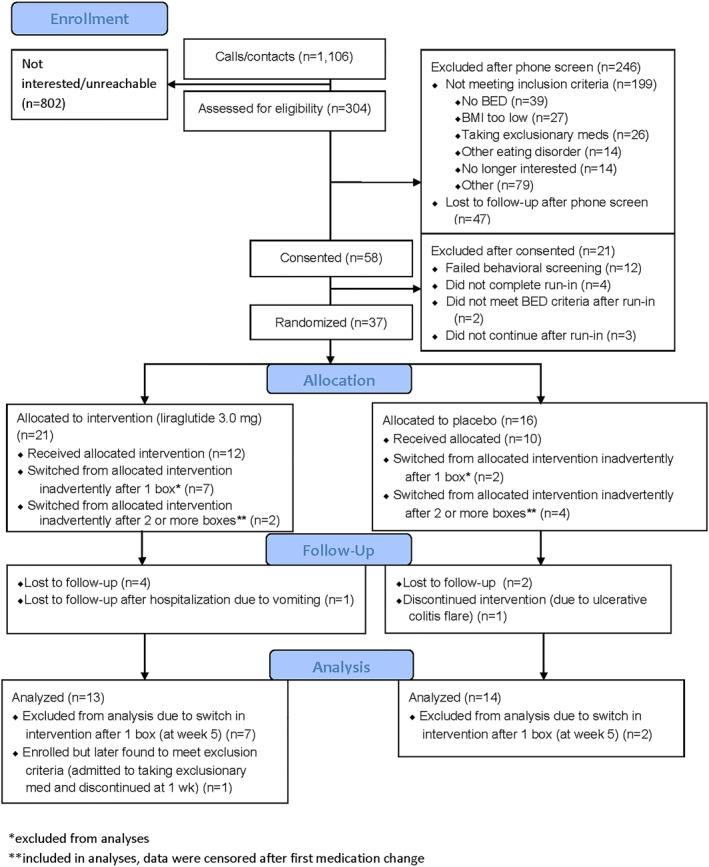

At the time that the error was identified (prior to any data analysis), we established criteria for inclusion in the modified intention‐to‐treat (mITT) analysis for affected participants. Because participants did not achieve full dose titration until after the second medication box was dispensed at 5 weeks, we chose to include only participants who received at least two boxes of the same medication in a row (i.e., those in the study more than 5 weeks). Of the 15 affected participants, 6 received at least two consecutive boxes of the same agent and were retained in the analyses. These participants' data were censored (i.e., treated as missing) after the point at which the first medication switch occurred. Nine participants were not included in the analyses because they did not receive more than one box of the same agent. The trial recruitment was ended early with 27 participants with usable data out of the 37 who were initially enrolled (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics package version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) with an alpha of 0.05. Data for the primary outcome, binge episode frequency, were skewed and a shifted log transformation was applied to better meet normality assumptions prior to conducting statistical comparisons. Preliminary analyses compared baseline differences between randomized groups on demographic characteristics, binge eating, and secondary outcomes using t‐tests or chi squared tests.

All primary and secondary outcome models were adjusted for sex and age. For binge eating frequency, anthropomorphic measurements, depression, and quality of life, mean changes from week 0 to week 17 in the mITT population were compared using repeated measures linear mixed‐effects models. For these primary and secondary outcomes, in‐treatment measurements collected every other week throughout the intervention period were included in the models to improve the estimation of the missing or censored week 17 values. For each outcome, an appropriate model shape and covariance structure were selected based on model fit. 31 Generalized estimating equation models using a binomial distribution with a logit link and an autoregressive (AR(1)) correlation structure were used to assess differences between the two groups in the percentage of participants who achieved binge eating remission at week 17, defined as having reported no OBEs in the prior 2 weeks.

Because the EI was measured only at weeks 0 and 17, in‐treatment measurements were not available to inform the modeled estimates of individuals whose data were not available at week 17. We therefore used multiple imputation to conduct a mITT analysis for the subscale outcomes (Methods in Supporting Information). Repeated measures ANCOVAs (controlling for age and sex) were then conducted on the multiply imputed data sets and pooled in SPSS using Rubin's rules.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics and retention

Thirty‐seven participants were initially randomized (Figure 1). As noted above, nine participants (n = 7 in the liraglutide group and n = 2 in the placebo group) received an incorrect medication type at week 5 due to an administrative error and thus were not included in the mITT sample. One additional participant in the liraglutide condition was withdrawn after randomization due to late disclosure (at week 1) that she was taking an exclusionary medication (metformin), leaving 27 participants in the analytic sample. There were no significant baseline differences between the 27 participants who were included in the mITT analyses and the 9 participants who were excluded due to not having received at least two boxes of a consistent medication type (Table S1).

Of the 13 included participants who were randomized to liraglutide, 7 (53.8%) completed the intervention and received liraglutide consistently for 17 weeks. An additional two liraglutide‐treated participants had data censored after week 9 (n = 1) or week 13 (n = 1) due to the medication allocation error, and five were lost to follow‐up. Of the 14 individuals randomized to placebo, 7 (50.0%) completed the intervention and received placebo for the entire 17 weeks. Four placebo‐treated participants had data censored after week 9 (n = 3) or week 13 (n = 1) due to the medication allocation error, and two were lost to follow‐up. Finally, one placebo‐treated participant completed the study off drug after her treatment was discontinued by the principal investigator following a serious adverse event (ulcerative colitis flare requiring hospitalization) (see CONSORT diagram, Figure 1).

Of the 27 adults included, 63.0% were women, 100% were non‐Hispanic, 59.3% were White, and 40.7% were Black. They had a mean ± SD age of 44.5 ± 10.5 years and a mean BMI of 37.9 ± 11.8 kg/m2. Twelve participants (44.4%) had a history of major depressive disorder based on the MINI diagnostic evaluation, three of whom (11.1% of mITT sample) also had a current major depressive episode. Three participants (11.1%) had at least one historic or current anxiety disorder diagnosis. The treatment groups differed significantly at baseline only on EI Hunger scores, with participants in the liraglutide group showing higher hunger scores (Table 2). However, there was a clinically notable (non‐significant) trend toward individuals in the liraglutide group having a higher baseline number of binge episodes per week (M = 4.9 ± 3.1) than those in the placebo group (M = 2.8 ± 1.8, d = 0.74, p = 0.065) with a large effect size.

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics at randomization

| Characteristic | Total (N = 27) | Placebo (N = 14) | Liraglutide 3.0 mg (N = 13) | Cohen's d (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 17 (63.0%) | 11 (78.6%) | 6 (46.2%) | ‐‐ | 0.09 |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| Black | 11 (40.7%) | 6 (42.9%) | 5 (38.5%) | ‐‐ | 0.82 |

| White | 16 (59.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 8 (61.5%) | ||

| Age (years) | 44.5 ± 10.5 | 42.8 ± 12.5 | 46.3 ± 7.8 | 0.34 (−0.43, 1.09) | 0.39 |

| Objective binge episodes per week a | 3.8 ± 2.7 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 3.1 | 0.74 (−0.05, 1.52) | 0.07 |

| Weight (kg) | 106.4 ± 21.4 | 105.1 ± 23.6 | 107.7 ± 19.6 | 0.12 (−0.64, 0.87) | 0.76 |

| Height (cm) | 169.1 ± 14.2 | 170.6 ± 10.7 | 167.6 ± 17.6 | −0.21 (−0.96, 0.55) | 0.59 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37.9 ± 11.8 | 35.8 ± 5.7 | 40.1 ± 16.0 | 0.36 (−0.40, 1.12) | 0.36 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 110.8 ± 12.9 | 110.5 ± 14.5 | 111.0 ± 11.6 | 0.04 (−0.72, 0.79) | 0.92 |

| Depressed mood (PHQ‐9) b | 6.5 ± 4.8 | 6.6 ± 5.5 | 6.3 ± 3.9 | −0.06 (−0.83, 0.71) | 0.88 |

| Quality of life (Q‐LES‐Q General) c | 72.4 ± 13.0 | 71.7 ± 12.6 | 73.4 ± 14.0 | 0.13 (−0.67, 0.92) | 0.76 |

| Eating inventory | |||||

| Cognitive restraint c | 7.8 ± 3.5 | 7.8 ± 3.7 | 7.8 ± 3.5 | 0.02 (−0.77, 0.81) | 0.96 |

| Disinhibition c | 13.0 ± 2.8 | 12.7 ± 3.6 | 13.3 ± 1.3 | 0.19 (−0.60, 0.98) | 0.64 |

| Hunger c | 10.0 ± 2.9 | 8.5 ± 3.0 | 11.9 ± 0.9 | 1.47 (0.56, 2.35) | 0.001 |

Note: Values are means ± SD except where otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: PHQ‐9, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 Item; Q‐LES‐Q, Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Means for binge eating episodes are expressed in real units, but the statistical analysis was performed on log transformed values. Back‐transformed log means were 3.5 ± 1.5 binge episodes in the placebo group and 5.1 ± 3.0 episodes in the liraglutide group.

N = 26 due to missing item responses.

N = 25 due to missing item responses.

3.2. Binge‐eating outcomes

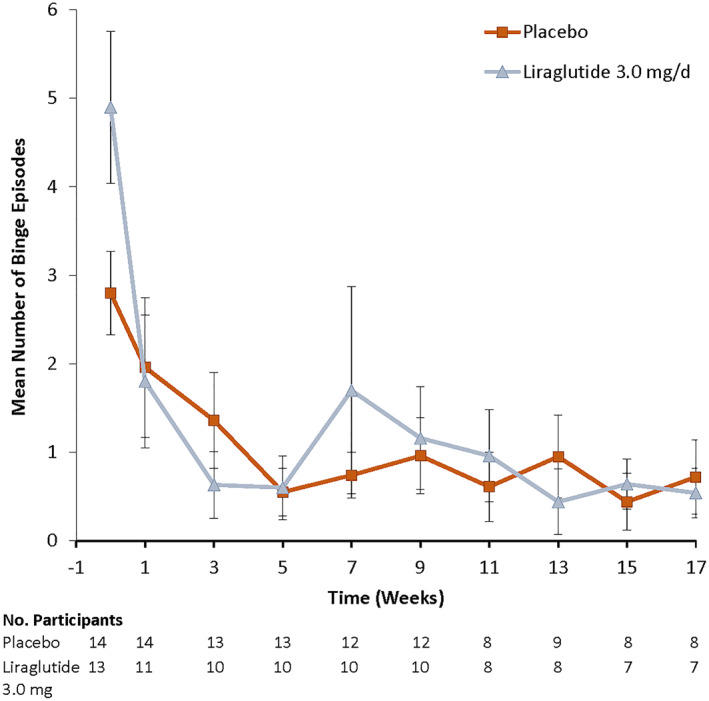

Between baseline and week 17, binge episode frequency declined by a mean (SE) of 4.0 (0.6) episodes per week in the liraglutide group, which did not differ significantly from the mean (SE) 2.5 (0.5) episode reduction in the placebo group [p = 0.37, mean difference = 1.2, 95% confidence interval (CI): −1.3, 2.0] (Table 3). Binge episodes decreased quickly in both groups with a steep decline by week 1, a reduction that was maintained through the end of treatment at week 17 (Figure 2). Participants in both groups reported having less than one binge episode per week on average at week 17, with the liraglutide group reporting a mean (SE) 0.7 (0.4) and the placebo group reporting mean (SE) 0.5 (0.4).

TABLE 3.

Changes from week 0 to week 17 in binge episodes, clinical improvement ratings, anthropometrics and psychosocial functioning in the placebo and liraglutide 3.0 mg groups

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 14)Mean ± SE | Liraglutide 3.0 mg (N = 13)Mean ± SE | Mean difference (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective binge episodes per week a | −2.5 ± 0.5 | −4.0 ± 0.6 | 1.2 (−1.3, 2.0) | 0.37 |

| CGII | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.2) | 0.30 |

| Body weight (kg) | −0.9 ± 0.7 | −4.7 ± 0.8 | 3.7 (1.4, 6.0) | 0.003 |

| Percent change in weight | −0.9 ± 0.9 | −5.1 ± 1.0 | 4.2 (1.4, 7.1) | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.3 ± 0.4 | −1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.0 (−0.2, 2.2) | 0.10 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | −1.2 ± 0.9 | −4.0 ± 1.1 | 2.8 (−0.1, 5.8) | 0.06 |

| Depression (PHQ‐9) | −3.4 ± 1.0 | −3.7 ± 1.1 | 0.3 (−2.7, 3.4) | 0.83 |

| Quality of life (Q‐LES‐Q‐General) | 5.1 ± 2.9 | 4.5 ± 3.3 | 0.6 (−8.4, 9.7) | 0.89 |

| Eating inventory | ||||

| Cognitive restraint | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 1.2 (−1.8, 4.1) | 0.38 |

| Disinhibition | −1.6 ± 0.7 | −2.6 ± 0.8 | 1.0 (−1.0, 2.9) | 0.25 |

| Hunger | −2.1 ± 1.0 | −2.7 ± 1.0 | 0.6 (−2.3, 3.4) | 0.58 |

Note: Values for all measures with exception of the Eating Inventory are estimated marginal means ± SE derived from linear mixed models. Values for the Eating Inventory subscales are pooled means ± SE from multiple imputation data sets. All models were adjusted for sex and age. CGII scores range from 1 “very much improved” to 7 “very much worse,” with a score of 4 indicating “no change.”

Abbreviations: CGII, Clinical Global Impression of Improvement Scale; PHQ‐9, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 item; Q‐LES‐Q, Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Means for binge eating episodes are expressed in real units, but the statistical analysis was performed on log transformed values. Back‐transformed log means for change from week 0–17 were −2.7 ± 0.4 binge episodes in the placebo group and −3.4 ± 0.6 episodes in the liraglutide group.

FIGURE 2.

Observed mean (SE) number of binge episodes per week in the liraglutide 3.0 mg and placebo groups by treatment week

At week 17, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the percentage of participants that achieved binge‐eating remission, defined as reporting no OBEs within the prior 2 weeks (p = 0.76). In the mITT sample, an estimated 44% of liraglutide‐treated participants (95% CI: 12%, 83%) and 36% of placebo‐treated participants (95% CI: 11%, 70%) reported remission at week 17. Among treatment completers, 3 of 7 (42.9%) in the liraglutide group and 4 of 8 (50%) in the placebo group reported no binge episodes during the prior 2 weeks. Week 17 clinician ratings of patients' binge‐eating improvement on the CGII also did not differ significantly between the groups. Mean ratings in both groups fell in the “much improved” to “very much improved” range at the end of treatment.

3.3. Weight loss and psychosocial outcomes

At week 17, the liraglutide group had a significantly larger mean weight loss of 4.7 kg (95% CI: 2.9, 6.4), compared to the 0.9 kg loss (95% CI: −0.6, 2.5) of placebo‐treated participants (Table 3). The liraglutide and placebo groups also differed significantly in percent reduction in baseline weight loss at that time, with losses of 5.1% (95% CI: 3.0, 7.3) and 0.9% (95% CI: −1.0, 2.8), respectively. The liraglutide group had somewhat larger reductions in BMI and waist circumference, but the between‐group differences in those outcomes did not reach statistical significance. Changes in eating behavior (Disinhibition, Cognitive Restraint, Hunger), depressive symptoms, and quality of life did not differ between the groups.

3.4. Adverse events

There were two serious adverse events in the liraglutide group, including a hospitalization attributed to vomiting and a laparoscopically‐performed cholecystectomy, and one in the placebo group, an ulcerative colitis flare. Adverse events were experienced by 89.5% of participants in the liraglutide group and 64.7% of the placebo group and are detailed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | Placebo (N = 17 a ) n (%) | Liraglutide 3.0 mg (N = 19 a ) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis flare b | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cholecystectomy b | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Severe vomiting b | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0%) | 5 (26%) |

| Nausea | 3 (18%) | 5 (26%) |

| Tachycardia | 0 (0%) | 3 (16%) |

| Dry mouth | 0 (0%) | 3 (16%) |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 (6%) | 2 (11%) |

| Indigestion | 2 (12%) | 2 (11%) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 1 (6%) | 2 (11%) |

| Joint pain | 2 (12%) | 1 (5%) |

The number of participants in each group includes participants who were discontinued and did not meet criteria for inclusion in the outcome analyses. Therefore, more participants are included in this table than in the previous tables.

Serious adverse events where participants sought hospitalization.

4. DISCUSSION

Participants who took liraglutide 3.0 mg per day did not differ at week 17 in their reduction in OBEs from those treated with placebo. The mean reduction of 4.0 binge episodes per week in the liraglutide group was similar to that shown with lisdexamfetamine at −4.1 episodes 8 and relatively larger than that of other medications that have been tested in patients with BED. Sibutramine (15 mg/day) produced a significant reduction of 2.7 episodes and a remission estimate of 59% at 24 weeks as compared to 2.0 episodes and a remission estimate of 43% for those taking placebo. 12 Similar reductions as in the current study have also been shown with topiramate and sertraline. 7 In the present study, both groups reported fewer than one binge episode per week at treatment end, suggesting a possible floor effect. Thus, the reduction observed with liraglutide 3.0 mg was clinically significant and is worthy of further study in a larger trial.

Participants in the liraglutide group achieved a significantly larger mean weight loss (5.1%) than those in the placebo group (0.9%). A 5% weight loss is considered clinically meaningful and is associated with improvements in obesity‐related comorbidities. 32 Persons with BED have been shown to lose less weight in behavioral weight loss trials than those without BED. 33 The present results suggest that liraglutide may be a promising approach for weight management in this population. There were no significant differences in mood or quality of life between the groups, possibly due to both reporting fewer than one binge episode per week at the end of treatment.

Limitations of this study include the impact of the misallocation of liraglutide and placebo refills to participants by the university's Investigational Drug Service, which reduced the number of participants with analyzable data. Dealing with this incident also produced a large pause in the trial, from which it was difficult to recover recruitment efforts. Ultimately, trial recruitment was terminated early. Thus, the sample size was small, which likely impacted our ability to detect significant differences between the groups. Also, the participants in this study had a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or greater due to the approved parameters for use of the study drug, so this would not be applicable to individuals with BED at lower BMIs. Finally, the placebo‐responsiveness of BED has been documented previously. 34 We attempted to limit the impact of this issue by having a 2‐week behavioral‐monitoring run‐in period, yet we still observed an improvement in the placebo group.

Identifying treatments for BED that are accessible to those who live with the disorder remains an important priority. Based on the results of this small trial, liraglutide 3.0 mg/day appears to be a promising treatment for reducing both binge episodes and body weight in those with BED and obesity. It produced improvements on these outcomes similar to those achieved with lisdexamfetamine. 8 Larger trials of liraglutide are warranted based on these initial findings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kelly C. Allison, Thomas A. Wadden and Robert I. Berkowitz conceived the idea and designed the study; Kelly C. Allison, Ariana M. Chao, Maija B. Bruzas, Courtney McCuen‐Wurst, Elizabeth Jones, Cooper McAllister, Kathryn Gruber, and Jena S. Tronieri collected the data; Kelly C. Allison, Ariana M. Chao, Maija B. Bruzas, Thomas A. Wadden, and Jena S. Tronieri contributed to the data analysis plans; Jena S. Tronieri performed the analysis; Kelly C. Allison, Ariana M. Chao, Thomas A. Wadden and Jena S. Tronieri drafted the paper; all authors participated in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Ariana M. Chao reports grant funding from Eli Lilly and Company and WW International, Inc., outside the submitted work. Robert I. Berkowitz has received research grant support from Novo Nordisk and Eisai Inc. and has served as a scientific consultant to WW International. Thomas A. Wadden serves on scientific advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and WW International and has received grant support from Novo Nordisk and Epitomee Medical. Jena S. Tronieri has received consulting fees/honoraria from Novo Nordisk.

Supporting information

Supporting Information 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the participants for volunteering for this study. This independent research received funding and study drug support from Novo Nordisk as an investigator‐sponsored study (ISS) to KCA.

Allison KC, Chao AM, Bruzas MB, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of liraglutide 3.0 mg for binge eating disorder. Obes Sci Pract. 2023;9(2):127‐136. 10.1002/osp4.619

Present address: Maija B. Bruzas, Health Psychology Associates PC, Greeley, CO, USA. Elizabeth Jones, Central Behavioral Health, Willow Grove, PA, USA. Cooper McAllister, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA. Kathryn Gruber, Matrix Medical Network, Scottsdale, AZ, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- 2. Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM‐5‐defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(5):345‐354. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ivezaj V, Kalebjian R, Grilo CM, Barnes RD. Comparing weight gain in the year prior to treatment for overweight and obese patients with and without binge eating disorder in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(2):151‐154. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. Substantial weight gains are common prior to treatment‐seeking in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):880‐884. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):904‐914. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winkler LA, Christiansen E, Lichtenstein MB, Hansen NB, Bilenberg N, Støving RK. Quality of life in eating disorders: a meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(1):1‐9. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Peat CM, et al. Binge‐eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(6):409‐420. 10.7326/m15-2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McElroy S, Mitchell J, Wilfley D, et al. Efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine for treatment of adults with moderate to severe binge‐eating disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(3):235‐246. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerdjikova AI, McElroy SL, Winstanley EL, et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of binge eating disorder with depressive disorders: a placebo‐controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(2):281‐289. 10.1002/eat.20946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Malotra S, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Keck PE. Citalopram in the treatment of binge eating disorder: a placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(7):807‐813. 10.4088/jcp.v64n0711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leombruni P, Lavagnino L, Fassino S. Treatment of obese patients with binge eating disorder using topiramate: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:385‐392. 10.2147/ndt.s3420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Hudson JI, et al. Efficacy of sibutramine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized multicenter placebo‐controlled double‐blind study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(1):51‐58. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06121970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM. DSM‐IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(3):228‐234. 10.1002/eat.20599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Javaras KN, Pope HG, Lalonde JK, et al. Co‐occurrence of binge eating disorder with psychiatric and medical disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):266‐273. 10.4088/jcp.v69n0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Can J, Sloth B, Jensen C, Flint A, Blaak E, Saris W. Effects of the once‐daily GLP‐1 analog liraglutide on gastric emptying, glycemic parameters, appetite and energy metabolism in obese, non‐diabetic adults. Int J Obes. 2014;38(6):784‐793. 10.1038/ijo.2013.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon‐like peptide 1. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(4):1409‐1439. 10.1152/physrev.00034.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chao AM, Wadden TA, Walsh OA, et al. Effects of liraglutide and behavioral weight loss on food cravings, eating behaviors, and eating disorder psychopathology. Obesity. 2019;27(12):2005‐2010. 10.1002/oby.22653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robert SA, Rohana AG, Shah SA, Chinna K, Mohamud WNW, Kamaruddin NA. Improvement in binge eating in non‐diabetic obese individuals after 3 months of treatment with liraglutide — a pilot study. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;9(3):301‐304. 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gormally J, Glack S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982;7(1):47‐55. 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O'Connor ME. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, ed. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. 16th ed. Guilford; 2008:265‐308. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606‐613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C‐SSRS). New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Novo Nordisk, Inc . Liraglutide (rDNA Origin) Injection [package insert]. Plainsboro; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two‐year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. NEJM. 2011;365(21):1969‐1979. 10.1056/nejmoa1109220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guy W ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacology Research Branch, National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q‐LES‐Q): a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321‐326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Capece JA, Beyers K, Fisher AC, Rosenthal NR. Topiramate for the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a placebo‐controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(9):1039‐1048. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allison KC, Studt SK, Berkowitz RI, et al. Anopen‐label efficacy trial of escitalopram for night eating syndrome. Eat Behav. 2013;14:199‐203. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three‐factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29(2):71‐83. 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gallop R, Tasca GA. Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: II. The complexities. Psychother Res. 2009;19(4–5):438‐452. 10.1080/10503300902849475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. NEJM. 2017;376(3):254‐266. 10.1056/nejmra1514009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blaine B, Rodman J. Responses to weight loss treatment among obese individuals with and without BED: matched‐study meta‐analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;12(2):54‐60. 10.1007/bf03327579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jacobs‐Pilipski MJ, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, et al. Placebo response in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3):204‐211. 10.1002/eat.20287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8(3):206‐213. 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deal LS, Wirth RJ, Gasior M, Herman BK, McElroy SL. Validation of the Yale‐Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(7):994‐1004. 10.1002/eat.22407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information 1