Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified long-standing issues of burnout and stress among the U.S. nursing workforce, renewing concerns of projected staffing shortages. Understanding how these issues affect nurses’ intent to leave the profession is critical to accurate workforce modeling.

Purpose

To identify the personal and professional characteristics of nurses experiencing heightened workplace burnout and stress.

Methods

We used a subset of data from the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey for analysis. Binary logistic regression models and natural language processing were used to determine the significance of observed trends.

Results

Data from a total of 29,472 registered nurses (including advanced practice registered nurses) and 24,061 licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses across 45 states were included in this analysis. More than half of the sample (62%) reported an increase in their workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly high proportions reported feeling emotionally drained (50.8%), used up (56.4%), fatigued (49.7%), burned out (45.1%), or at the end of their rope (29.4%) “a few times a week” or “every day.” These issues were most pronounced among nurses with 10 or fewer years of experience, driving an overall 3.3% decline in the U.S. nursing workforce during the past 2 years.

Conclusion

High workloads and unprecedented levels of burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic have stressed the U.S. nursing workforce, particularly younger, less experienced RNs. These factors have already resulted in high levels of turnover with the potential for further declines. Coupled with disruptions to prelicensure nursing education and comparable declines among nursing support staff, this report calls for significant policy interventions to foster a more resilient and safe U.S. nursing workforce moving forward.

Keywords: Workforce, burnout, stress, pandemic, COVID-19, nursing shortage

For decades, scholars have warned of looming nursing shortages across the United States, citing an aging workforce and long-standing issues of burnout and stress stemming from high patient-to-nurse ratios, low pay, and concerns regarding workplace safety. The surge in patient volume and acuity driven by the COVID-19 pandemic compounded many of these pre-existing issues. Simultaneously, prelicensure nursing education programs were forced to rapidly re-invent themselves in response to clinical site disruptions, potentially affecting the supply and clinical preparedness of new nurse graduates. This combination of factors has led to unprecedented levels of burnout among newly licensed and tenured nurses alike. We used a subset of data from the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey to identify potential indicators of stress and burnout among the current nursing workforce to better target resources, tailor solutions, and inform policy decision-making.

Background

The overall number of registered nurses (RNs) in the United States has steadily risen over the past decade (NCSBN, 2023; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022), but the number of employed RNs per capita in each state varies widely (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022; United States Census Bureau, 2022). Even within single jurisdictions, regional differences exist (Scheidt et al., 2021; NCSBN Environmental Scan, 2023). Long-standing concerns over nursing shortages existed prior to the pandemic (Buerhaus et al., 2007; Snavely, 2016; Marć et al., 2019), but COVID-19 appears to have accelerated this trend and exacerbated many pre-existing workforce issues (Haas et al., 2020), such as nurses’ experiences of burnout and stress (Aiken et al., 2002; McHugh et al., 2011; Aiken et al., 2018). Emerging evidence suggests that between 22%–32% of the nursing workforce is actively considering retiring, leaving the profession, or leaving their current position in the near future (Smiley et al., 2021; Berlin, Lapointe, Murphy, & Wexler, 2022; Nurse.com, 2022; Smiley et al., 2023). Within specific subsets of the profession, such as critical care, the picture is even bleaker, with an estimated 67% of nurses indicating that they plan to leave their current position in the next 3 years (Ulrich et al., 2022).

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many of these trends, it is often not the root cause of the problem, nor are the issues isolated to the United States. The main drivers of nurses’ intent to leave are frequently identified as more durable issues or problems, such as insufficient staffing levels, desire for higher pay, not feeling listened to or supported at work, and the emotional toll of the job (Lasater et al., 2021; Galanis et al., 2021; Murat et al., 2021; Berlin, Lapointe, & Murphy, 2022). In fact, when ranked, McKinsey research found that financial considerations and plans to retire or return to school often played bigger roles in nurses’ decision-making than the pandemic (Berlin, Essick, et al., 2022). Furthermore, scholars have found that intent to leave is typically influenced by a multitude of factors, including individual characteristics such as job satisfaction and frequency of experiencing “moral distress,” and work environment characteristics, such as appropriate staffing, quality of care, safety, etc. (Aiken et al., 2022; Ulrich et al., 2022). Surveys have found that these experiences translate internationally as well, with substantial proportions of nurses in France, Singapore, Japan, and the United Kingdom indicating they also plan to leave direct care for many of the same reasons (Berlin, Essick, et al., 2022).

Fissures in the U.S. healthcare system were apparent from the start of the pandemic, with multiple reports identifying critical staffing shortages from the onset of COVID-19 (Spetz, 2020) and throughout surge events driven by variant strains of the virus (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2022). Distressingly, emerging evidence suggests the pandemic has even stalled the decades-long workforce growth trend, with data now showing that a decline in the RN population by approximately 100,000 may be primarily due to a 4% dropoff in the number of RNs younger than 35 years (Auerbach et al., 2022). While it is not yet clear whether the trend of younger nurses pausing or leaving nursing “is a temporary or more permanent phenomenon” (Firth, 2022), there is reason for concern. Some researchers now project a gap of 200,000 to 450,000 nurses by 2025—a gap partly driven by a decreased supply of the absolute RN workforce but also amplified by increased in-patient demand from or related to COVID-19 and an aging population (Berlin, Essick, et al., 2022).

In addition, many healthcare facilities closed their doors to clinical experiences to reduce the spread of COVID-19 and preserve their limited supplies of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic (Dewart et al., 2020). As a result, many prelicensure nursing programs faced enormous difficulty in securing traditional in-person clinical placements, directly affecting the supply and preparedness of new nurse graduates (Emory et al., 2021; Lanahan et al., 2022). In response, most nursing programs shifted their face-to-face lectures to online platforms and their traditional clinical placements to simulation-based and virtual simulation-based experiences (Benner, 2020; Innovations in Nursing Education, 2020; Kaminski-Ozturk & Martin, 2023; Martin et al., 2023). The scope and speed of this pivot presented particular challenges for faculty and administrators in the health professions, as the rapid development and implementation of online and simulated curricula often ran counter to their own academic training (Booth et al., 2016; Seymour-Walsh et al., 2020). Despite many challenges (Michel et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2021), some evidence suggests prelicensure nursing students maintained learning outcomes (Konrad et al., 2021). However, others have documented the need for more hands-on training and the frustration of new nurse graduates over the apparent mismatch between their clinical experiences and their role entering the clinical setting during a global health crisis (Crismon et al., 2021; Emory et al., 2021; Bultas & L’Ecuyer, 2022; Lanahan et al., 2022).

Taken together, the U.S. nursing workforce is at a critical crossroads (NCSBN, 2023). To better inform and target policy solutions with the goal of fostering a more sustainable workforce, we analyzed a subset of data from the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey to address two primary research questions:

-

1.

What are the personal and professional characteristics of nurses experiencing heightened workplace burnout and stress?

-

2.

How do nurses’ experiences of burnout and stress inform their intent to leave the profession?

Methods

Survey Sample

All RNs, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs) with an active license in the United States and its territories were eligible to be survey participants. The bulk of the sample was drawn from Nursys, NCSBN’s licensure database. This database contains basic demographic and licensure information for RN and LPN/LVN licensees. For Georgia, the licensee list and addresses were purchased directly from Medical Marketing Service, Inc. Separate RN and LPN/LVN samples were drawn at random and stratified by state. As nurses can hold multiple single-state licenses, an initial review of all data was undertaken to de-duplicate license counts for individual practitioners by assigning licensees a single home state based on primary address.

Study Design

The core of the National Nursing Workforce Survey is comprised of the National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers’ Nurse Supply Minimum Data Set, which was approved in 2009 and updated in 2016 (The National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers, 2016). However, the survey instrument also includes several custom items for a total of 39 questions across the following six domains: (1) COVID-19 Pandemic; (2) License Information; (3) Work Environment; (4) Telehealth; (5) Nurse Licensure Compact; and (6) Demographics. Items specific to respondents' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and work as travel nurses during the past 2 years were added for the 2022 cycle. The survey was initially fielded on April 11, 2022, via direct mail outreach in partnership with Scantron, a leader in assessment and technology solutions, and hosted online via Qualtrics (Provo, UT). The survey remained open for approximately 6 months, with two scheduled mail reminders at weeks 10 and 20 and regular weekly email reminders for online surveys. A comprehensive overview of the survey methods, including the sampling strategy, and detailed national results will be available in a forthcoming publication of the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey as a supplement to the Journal of Nursing Regulation. Prior to commencing any outreach, the study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board.

Dependent and Independent Variable Coding

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) is a reliable, and valid survey instrument comprising three domains: Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment (Maslach et al., 1997). Nurses completing the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey were asked to complete 5 Likert-scale items originating from the Emotional Exhaustion domain, which has a Cronbach’s alpha of .90 (Iwanicki & Schwab, 1981; Gold, 1984). Respondents were asked to indicate how frequently they feel emotionally drained, used up, fatigued, burned out, or at the end of their rope using a seven-point scale, where 1 meant “never” and 7 meant “every day.” After a review of the distribution of raw responses and to simplify interpretation, each dependent variable was collapsed to identify and isolate respondent characteristics that aligned with a reported frequency of “a few times a week” (6) or “every day” (7). In addition, for the primary independent variable (years’ experience), receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for each of the five included outcomes to identify, as possible, a general inflection point at which respondents’ sentiments appeared to consistently shift regarding experiences or drivers of burnout and stress. In aggregate, this cut point emerged at approximately 9 to 10 years of experience, so 10 years was selected to simplify the analysis and readers’ interpretation of the results.

Data Analysis

A descriptive summary of the sample includes counts and proportions for categorical variables, while continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. For most descriptive measures, there was minimal variation by license type, so sample-based estimates are reported. Where notable differences emerged, they are presented. Univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression models were used to compare respondents’ experiences of stress or burnout. An alpha error rate of p ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant and all analyses of structured survey items (e.g., fixed-item, check all that apply, etc.) were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Analysis of unstructured data was performed using the Natural Language Toolkit (Bird et al., 2009) and gensim (Řehůřek & Sojka, 2010) packages in Python 3.10. Data were first pre-processed, removing punctuation, numbers, and stop words (domain general and domain specific). Common bigrams, trigrams, and quadgrams were identified. Frequently used abbreviations and their fully spelled-out forms were also collapsed, and word tokens were lemmatized using the WordNet Lemmatizer. To extract recurrent themes identified in the responses, a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) probabilistic model (Blei et al., 2003) was employed.

The LDA model assumes there are a set number of latent topics—where a topic is a probability distribution across words found in the dataset—and each individual response has its own probability distribution across these latent topics. The LDA model can generate a response by sampling a topic based on the response’s probability distribution and then sampling a word based on the probability distribution of that topic. The model searches across possible topics to maximize the likelihood of generating the observed dataset. These topics group words that are commonly used together. LDA models were run using gensim for a range of topics; in the present article, we chose to use five-topic models because they performed better on the U Mass Coherence metric than models with other topic thresholds (Mimno et al., 2011). Because coherence metrics do not necessarily align with coherence as observed by humans, several five-topic models were evaluated and compared for final inclusion. An alpha error rate of p ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were conducted using the scipy.stats package (Virtanen et al., 2020) in Python.

Results

Sample Summary

A total of 54,025 respondents across 45 states were included in the sample. The sample was roughly evenly divided between RNs (50.0%, n = 26,749) and LPNs/LVNs (45.0%, n = 24,061), with APRNs (5.0%, n = 2,723) constituting a smaller subset. Respondents were on average 51 years old (M: 51.4, SD: 14.4) and reported a median of 19 years of experience (IQR: 9–34), with minimal variation by license type. A majority of respondents self-identified as female (92.5%, n = 48,546), non-Hispanic (95.%, n = 49,465), and White (79.9%, n = 41,728). In general, LPNs/LVNs tended to be more racially diverse (75.2% White) compared to RNs (82.5%) and APRNs (85.8%). While most respondents reported full-time employment in nursing (66.3%, n = 35,382), only 4.6% (n = 2,006) indicated they engaged in travel nursing. APRNs reported the highest rate of full-time employment (75.7%), while the full-time employment rates among LPNs/LVNs (66.3%) and RNs (65.7%) were more comparable. The median reported salary for LPNs/LVNs was $50,000 (IQR: $38,000–$60,000) compared to $75,000 (IQR: $58,000–$95,000) for RNs and $110,000 (IQR: $87,500–$140,000) for APRNs.

More than half of the sample (62.0%, weighted n = 3,002,301) reported an increase in their workload during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, high proportions reported feeling emotionally drained (50.8%, weighted n = 2,352,775), used up (56.4%, weighted n = 2,601,572), fatigued (49.7%, weighted n = 2,296,545), burned out (45.1%, weighted n = 2,080,380), or at the end of their rope (29.4%, weighted n = 1,353,809) “a few times a week” or “every day.” Nurses with 10 or fewer years of experience consistently reported a 28% to 56% increase in their frequency of feeling emotionally drained (OR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.36–1.47), used up (OR: 1.50, 95% CI: 1.44–1.56), fatigued (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.50–1.63), burned out (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.38–1.49), or at the end of their rope (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.23–1.34) compared to their more experienced counterparts (all p < .001, Table 1 ). Nurses who reported an increased workload during the pandemic displayed a similar pattern: emotionally drained (OR: 3.31, 95% CI: 3.19–3.44), used up (OR: 3.32, 95% CI: 3.19–3.45), fatigued (OR: 2.99, 95% CI: 2.88–3.11), burned out (OR: 2.80, 95% CI: 2.70 – 2.92), or at the end of their rope (OR: 2.35, 95% CI: 2.25–2.46) (all p <.001). Consistent univariable patterns also emerged by license type (RN, LPN/LVN vs. APRN), for those providing direct patient care, and for those who reported engaging in travel nursing (all p < .001). Trends related to years’ experience and increased workload held on multivariable analysis after further adjustments for respondents’ self-reported sex, ethnicity, race, salary, and license type, as well as indicators for full-time nursing employment, direct patient care, and travel nurse designation. Furthermore, a meaningful interaction between years of experience and increased workload emerged. Nurses with 10 or fewer years of experience who also reported an increased workload during the pandemic were between two and a half to more than three times more likely to report higher frequencies of feeling emotionally drained, used up, fatigued, burned out, or at the end of their rope compared to similarly inexperienced nurses with normal workloads (all p < .001, Table 2 ). Even compared to more experienced nurses with comparable workloads, early career respondents with high workloads still reported a 10% to 23% increase in feeling emotionally drained, used up, fatigued, burned out, or at the end of their rope (all p < .001). The most pronounced differences emerged when comparing early career nurses with higher workloads to their more experienced peers with normal workloads. In this comparison, early career respondents with high workloads were more than three to four times more likely to report higher frequencies of feeling emotionally drained, used up, fatigued, burned out, or at the end of their rope (all p < .001).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Summary for Respondents Who Reported a Frequency of “A Few Times a Week” or “Every Day” Across Each Emotional Exhaustion Outcome

| Emotionally Drained | Used Up | Fatigued | Burned Out | End of Rope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| License Type | |||||

| LPN/LVN | 48.1% (10,774) | 52.9% (11,770) | 47.3% (10,532) | 41.9% (9,328) | 27.7% (6,154) |

| RN | 48.6% (12,169) | 54.5% (13,584) | 47.5% (11,845) | 42.6% (10,613) | 27.8% (6,922) |

| APRN | 45.3% (1,196) | 50.3% (1,328) | 40.5% (1,070) | 36.5% (962) | 20.9% (550) |

| Years’ Experience | |||||

| ≤10 y | 53.4% (7,400) | 59.8% (8,258) | 53.8% (7,444) | 47.3% (6,552) | 30.3% (4,182) |

| 11+ y | 44.7% (13,568) | 49.7% (15,024) | 42.7% (12,903) | 38.5% (11,640) | 25.3% (7,628) |

| Travel Nurse | |||||

| No | 47.8% (19,537) | 53.3% (21,711) | 46.6% (19,026) | 41.0% (16,710) | 26.2% (10,649) |

| Yes | 59.8% (1,192) | 65.1% (1,290) | 60.1% (1,195) | 54.4% (1,079) | 37.2% (739) |

| Increased Workload | |||||

| No | 30.4% (5,663) | 35.5% (6,572) | 30.7% (5,697) | 27.1% (5,021) | 17.6% (3,255) |

| Yes | 59.1% (18,238) | 64.6% (19,836) | 57.0% (17,519) | 51.0% (15,681) | 33.4% (10,247) |

| Direct Patient Care | |||||

| No | 44.0% (5,200) | 48.3% (5,682) | 41.7% (4,910) | 36.9% (4,345) | 23.4% (2,758) |

| Yes | 50.0% (15,578) | 56.0% (17,380) | 49.4% (15,354) | 43.4% (13,487) | 27.9% (8,646) |

Notes. APRN = advanced practice registered nurse; LPN/LVN = licensed practical nurse/licensed vocational nurse; RN = registered nurse. Data presented as unweighted % (n). Dependent variables were collapsed to identify and isolate respondent characteristics that align with a reported frequency of “a few times a week” or “every day” across each of the five outcomes.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Results for Respondents Who Reported a Frequency of “A Few Times a Week” or “Every Day” Across all Outcomes

| Years’ Experience | Increased Workload Interactiona | Emotionally Drained | Used Up | Fatigued | Burned Out | End of Rope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤10 y | Yes | All p < .001 | All p < .001 | All p < .001 | All p < .001 | All p < .001 |

| ≤10 y | No (Ref) | 3.13 (2.85, 3.43) | 2.93 (2.68, 3.21) | 2.67 (2.44, 2.93) | 2.77 (2.52, 3.04) | 2.47 (2.21, 2.76) |

| 11+ y | Yes (Ref) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.25) | 1.23 (1.16, 1.31) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.25) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) |

| 11+ y | No (Ref) | 4.14 (3.85, 4.45) | 4.23 (3.93, 4.54) | 3.86 (3.59, 4.15) | 3.66 (3.40, 3.94) | 3.10 (2.84, 3.38) |

Note. Ref = reference. Multivariable model n ranges from 29,941 to 30,060 observations across all five dependent variables. Dependent variables were collapsed to identify and isolate respondent characteristics that align with a reported frequency of “a few times a week” or “every day” across each of the five outcomes. Results presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

In addition to years’ experience and increased workload, each model further adjusted for respondents’ self-reported sex, ethnicity, race, salary, and license type, as well as indicators for full-time nurse employment, direct patient care, and travel nurse designation.

Free-Response Analysis

Subjective characterizations were developed for each of the five topics included in the results (Table 3 ). This was achieved in two ways: first, by analyzing the set of words that were most frequent and salient for each topic, and, second, by identifying the 15 most representative survey responses. Topic 1, labeled COVID-19 stress, typically involved acute stressors relevant to the pandemic, ranging from both anti-vaccination and anti-public health intervention sentiments to more commonplace concerns about PPE shortages, vulnerability to COVID-19 infection, and long-haul infections. Topic 2 was characterized by stressors that may have predated but ultimately were exacerbated by the pandemic, such as staffing shortages, unsafe work environments, and workplace violence. Topic 3 was represented by more emotional responses, including respondents’ sense of feeling underappreciated and disrespected by patients and superiors. Responses that scored high for Topic 4 were focused on retirement and other types of career change, usually with the sentiment that stress and burnout were bad, but now that the respondent was no longer working in that environment, it was much better. Finally, Topic 5 was predominantly characterized by complaints about compensation levels.

TABLE 3.

Free Response Topics and Keywords

| Subjective Topic | % (n) of Responses | Keywords | Representative Responsea |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Stress | 20.2% (3,783) | home, covid, working, worked, resident, people, clinic, job, vaccine, agency, stressful, forced, family, mask, hospital, vaccination | During COVID-19, homecare nursing was never addressed as a high risk job. Paramedics, hospital staff, and other essential workers seem to get addressed and considered for vaccines but I was told by my physician that I was not eligible for the vaccine when it came out. It was and still is like playing Russian roulette going into patients’ homes, not knowing if they have been exposed or not. PPE equipment was not always available, and every assisted living facility had different rules for homecare to follow. |

| Unsafe Staffing/Work Environment | 23.2% (4,338) | staff, covid, stress, pandemic, short, staffing, anxiety, med, load, covid-19, always, leaving, regulation, increased, short staffed, ratio, facility, heavy, mandated, supply, burnout, job | The amount of extra work I have been required to perform at work without financial compensation is outstanding. My working environment is unsafe for both staffing and lack of security. There have been many times I thought I was in danger or a patient was in danger. These situations have led to me having anxiety and even full-blown panic attacks every morning when I clock in. I am terrified for my own safety, as well as for the patients I see every day. |

| Underappreciated | 22.6% (4,219) | feel, management, underpaid, overworked, administration, employer, shortage, underappreciated, support, under appreciated, burned out, burnout, lack, respect, feeling, | It isn’t the job, it is the lack of respect from everyone, especially when it comes from patients/clients and/or their support groups. I believe that there are fewer and fewer people wanting to be in healthcare due to the demands of what it takes to care for others. So when there are less people taking care of others as a healthcare professional, it puts more pressure and demands on a limited workforce. |

| Retirement/Career Change | 16.5% (3,086) | retired, license, burnout, 2020, busy, part time, back, stress, tired, shift, job, years ago, pandemic, illness, breathing, covid, exercise | I am retired and a widow. I’m active in church and help with my grandkids. I keep my LPN license because who knows. It would have to be light and low stress to return. |

| Compensation | 17.5% (3,275) | pay, increased, increase, load, paid, enough, workload, short_staffing, wage, staff, raise, staffing, poor, short_staffed, job, travel, incentive, too much, salary, ethic, stress, burnout, decreased, rate, money, need, ratio | Burn out, short staffed, not enough pay, and yet they want to cap nurses on wages, but you don’t see them capping physician pay or lawyer pay. |

Responses were lightly edited for punctuation and journal style.

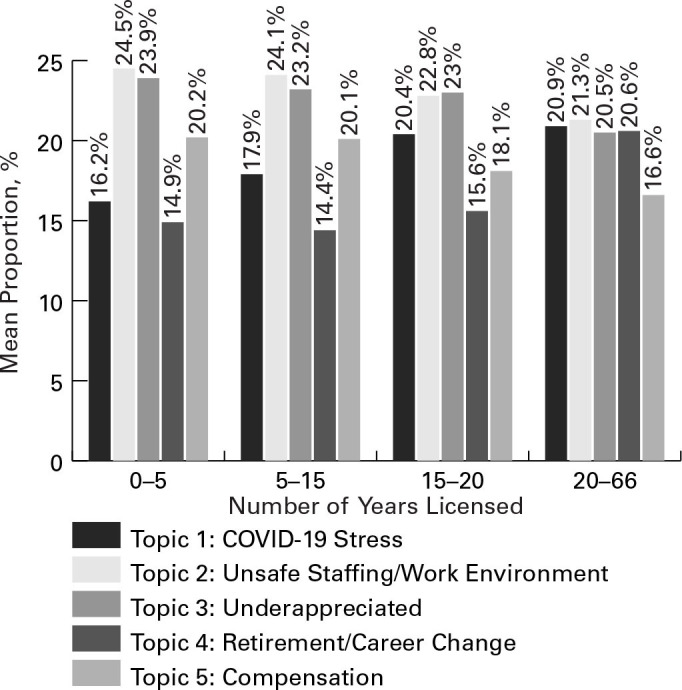

There was fair saturation across all five topics based on respondents’ license types (Figure 1 ). However, select themes appeared to resonate more with certain groups. For example, discussion of compensation was more common among APRNs, while unsafe staffing and work environments appeared more often in RNs’ narrative accounts, as did issues related to retirement or career change. Stress related to COVID-19, including both workplace and personal concerns, was more concentrated among LPNs/LVNs. Across all groups, issues related to feeling underappreciated emerged.

FIGURE 1.

Free-Response Topics by License Type

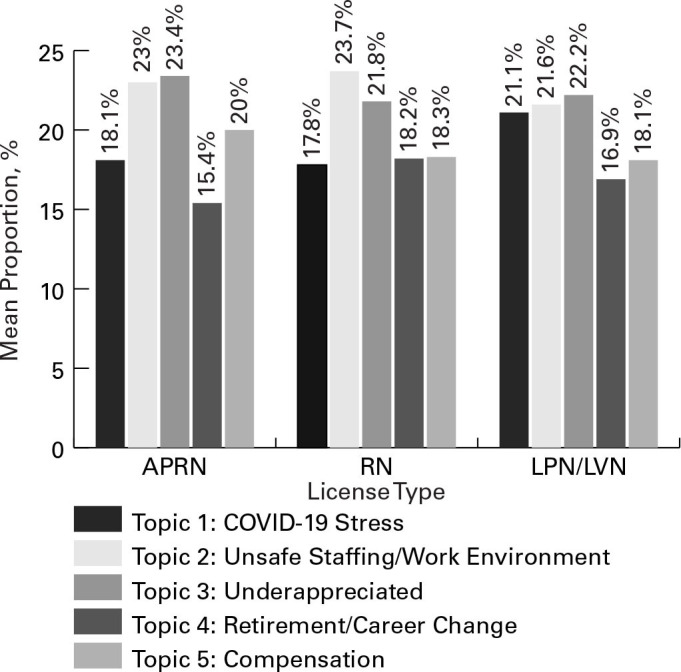

When compared against respondents’ years of work experience, even clearer patterns emerged, providing valuable interpretative context (Figure 2 ). There was a significant and positive linear relationship between reported years’ experience and topics one and four. In other words, more experienced nurses were more likely to self-report higher levels of burnout and stress specifically due to the pandemic and were more likely to share free-text comments regarding retirement or career change as a result. By contrast, an inverse relationship emerged between years of experience and topics two, three, and five. Thus, less experienced nurses, in particular those with <5 years’ experience, but also 5 to up to 15 years experience, were most likely to report unsafe staffing or work environments and feeling underappreciated. This less experienced cohort was also significantly more likely to raise concerns regarding compensation levels as well. Although these topics also emerged among more experienced nurses, they were significantly less pronounced.

FIGURE 2.

Free-Response Topics by Years’ Experience

Discussion

The U.S. nursing workforce is at a critical crossroads (NCSBN, 2023). Many of the problems currently confronting the nursing profession long predated the global health crisis (Aiken et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified these concerns, and current evidence has identified unprecedented levels of stress and burnout among the key factors driving high rates of projected turnover (Berlin, Lapointe, Murphy, & Wexler, 2022; Nurse.com, 2022; Smiley et al., 2021; Smiley et al., 2023). In this large, nationally representative survey of licensed nurses, approximately 50% of respondents reported feeling emotionally drained (50.8%), used up (56.4%), fatigued (49.7%), or burned out (45.1%) “a few times a week” or “every day.” More than a quarter of the workforce also reported feeling at the end of their rope (29.4%) at a similar frequency. This analysis confirms some of the potential drivers of these trends, such as significant increases in nurses’ workload during the pandemic (62%). However, even more importantly, it provides critical contextual evidence to better understand implications for the U.S. nursing workforce moving forward. Specifically, the findings illustrate a differential but equally meaningful impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on both ends of the experience spectrum, particularly among RNs. Furthermore, this report links such developments to simultaneous disruptions to traditional prelicensure nursing education models and comparable shortfalls among the supply of support workers (LPNs/LVNs). In doing so, this report seeks to inform policy aimed at fostering a more sustainable and safe U.S. nursing workforce.

In line with emerging evidence (Lasater et al., 2021; Galanis et al., 2021; Murat et al., 2021; Berlin, Lapointe, & Murphy, 2022), issues that often predated the pandemic, such as insufficient staffing levels, unsafe work environments, desire for higher pay, and not feeling appreciated emerged as concrete drivers of stress and burnout among respondents to this national survey. The findings of this study confirm that these concerns have been felt most acutely by less experienced nurses. RNs (+20%) and LPNs/LVNs (+16%) with 10 or fewer years of experience were significantly more likely to report an increased workload during the pandemic compared to their more experienced peers, leading to higher rates of reported burnout and stress (p < .001 across all outcomes). In the past 2 years, this has resulted in a net decline of 3.3% of the nursing workforce across all levels. Although the the RN workforce decline is a bit lower (2.7%), the absolute decline in frontline RNs is striking. In 2022, a nationally weighted estimate of 97,312 RNs reported they left nursing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Alarmingly, RNs with 10 or fewer years of experience, who were a mean age of 36 (SD: 10.3) years, left at an even faster pace (3%) and accounted for nearly 41% of the total dropoff in practicing RNs (39,785). These trends mirror findings from the Current Population Survey, which was sponsored jointly by the United States Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Auerbach et al., 2022).

Disconcertingly, a high proportion of RNs with 10 or fewer years’ experience also reported they planned to leave nursing in the next 5 years (15.2%). If this were to come to pass, it would result in a net decline of an additional 188,962 RNs (nationally weighted estimate) currently younger than 40 years. Although it is not yet clear if the trend will hold (Firth, 2022), these results align with McKinsey research, which projected a gap of 200,000 to 450,000 nurses in the United States by 2025 (Berlin, Essick, et al., 2022). Again, increased workload emerged as a potential driver of this trend in this analysis (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.15–1.58, p < .001). Furthermore, these results are compounded by the emergence of a dumbbell distribution in the findings, which suggest that stress directly linked to the pandemic is simultaneously driving a high proportion of RNs with more than 10 years of work experience and a mean age of 57 (SD: 11.7) years to consider leaving their position or retiring in the next 5 years (44.8%, 610,388). This is on top of the 50,009 RNs (weighted national estimate) with more than 10 years of experience who reported they already left nursing due to the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, traditional support and re-supply apparatuses (e.g., LPN/LVNs and new nurse graduates) appear less resilient than they once were. On one hand, prelicensure nursing education programs have faced considerable and somewhat unprecedented disruptions (Benner, 2020; Dewart et al., 2020; Innovations in Nursing Education, 2020; Kaminski-Ozturk & Martin, 2023; Martin et al., 2023). This has, in turn, spurred concerns regarding the supply and clinical preparedness of new nurse graduates. On the other hand, this report confirmed comparable declines (4.2%) among nursing support staff, which resulted in 33,811 fewer LPNs/LVNs (weighted national estimate) in the U.S. nursing workforce compared to the start of the pandemic. Paired with documented trends among currently licensed RNs, and absent some form of intervention, these combined results raise considerable concerns regarding the resilience of the U.S. nursing workforce moving forward.

Limitations

Despite a large and geographically diverse respondent pool, we were not able to capture pandemic-related feedback from respondents in five nursing jurisdictions due to our sampling method. That may somewhat limit our ability to generalize our findings to nurses in Missouri, Wyoming, New Mexico, North Carolina, and Washington. Furthermore, nationally weighted estimates associated with projected intent to leave represent a potential loss in the number of licensed nurses. As some nurses hold multiple licenses and indeed practice across state lines, there is a possible multiplicative effect associated with the potential attrition. Combined with the state sample limitation, it is likely the projections shared in this report are conservative regarding the scale of any future loss. In addition, the LDA model defines topics via word co-occurrence relationships, but it has no direct understanding of semantic or contextual information, and it is equally unable to capture semantic connections as elements of respondent dialect and/or style. Given that respondent demographics might influence a respondent’s word choice (e.g., older respondents may choose to use different words than younger respondents), it is possible that the topics discovered here may be influenced simply by how different respondent groups talk about burnout. Finally, the quantitative trends documented in this study are correlational and do not support causal inference.

Conclusion

High workloads and unprecedented levels of stress and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic have strained the U.S. nursing workforce. This has already resulted in high levels of turnover during the past 2 years among younger, less experienced nurses. In parallel, disruptions to prelicensure nursing education coupled with comparable declines among nursing support staff suggest the U.S. nursing workforce may be at a critical juncture. This report serves to confirm and quantify projected trends that have recently begun to emerge in the literature, but it also provides critical contextual evidence to better understand implications for the nursing workforce moving forward. Should some of the projections derived from this analysis and mirrored by government data and market research come to pass, the outlook for the U.S. healthcare system could be dire. Fortunately, projected intent to leave or retire is not static but rather a manipulable outcome depending on policymakers’ future decisions. This work seeks to inform debates on future workforce policy and, in doing so, better target resources and tailor solutions aimed at fostering a more sustainable and safe U.S. nursing workforce.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Aiken L.H., Clarke S.P., Sloane D.M., Sochalski J., Silber J.H. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L.H., Sloane D.M., Barnes H., Cimiotti J.P., Jarrín O.F., McHugh M.D. Nurses’ and patients’ appraisals show patient safety in hospitals remains a concern. Health Affairs. 2018;37(11):1744–1751. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L.H., Sloane D.M., McHugh M.D., Pogue C.A., Lasater K.B. A repeated cross-sectional study of nurses immediately before and during the Covid-19 pandemic: Implications for action. Nursing Outlook. Advance online publication. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach D.I., Buerhaus P.I., Donelan K., Staiger D.O. A worrisome drop in the number of young nurses. Health Affairs Forefront. 2022 doi: 10.1377/forefront.20220412.311784. , April 13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. Finding online clinical replacement solutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educating Nurses. 2020 https://www.educatingnurses.com/author/pbenner/page/4/ , March 19. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin G., Essick C., Lapointe M., Lyons F. McKinsey & Company; 2022, May 12. Around the world, nurses say meaningful work keeps them going.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/around-the-world-nurses-say-meaningful-work-keeps-them-going [Google Scholar]

- Berlin G., Lapointe M., Murphy M. McKinsey & Company; 2022, February 17. Surveyed nurses consider leaving direct patient care at elevated rates. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/surveyed-nurses-consider-leaving-direct-patient-care-at-elevated-rates. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin G., Lapointe M., Murphy M., Wexler J. McKinsey & Company; 2022. Assessing the lingering impact of COVID-19 on the nursing workforce.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/assessing-the-lingering-impact-of-COVID-19-on-the-nursing-workforce , May 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S., Klein, E., & Loper, E. (2009). Natural language processing with Python: analyzing text with the natural language toolkit. O’ReillyMedia, Inc.

- Blei D.M., Ng A.Y., Jordan M.I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. the Journal of machine Learning research. 2003;3:993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Booth T.L., Emerson C.J., Hackney M.G., Souter S. Preparation of academic nurse educators. Nurse Education in Practice. 2016;19:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerhaus P.I., Donelan K., Ulrich B.T., Norman L., DesRoches C., Dittus R. Impact of the nurse shortage on hospital patient care: Comparative perspectives. Health Affairs. 2007;26(3):853–862. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultas M.W., L’Ecuyer K.M. A longitudinal view of perceptions of entering nursing practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2022;53(6):256–262. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20220505-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crismon D., Mansfield K.J., Hiatt S.O., Christensen S.S., Cloyes K.G. COVID-19 pandemic impact on experiences and perceptions of nurse graduates. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2021;27(5):857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewart G., Corcoran L., Thirsk L., Petrovic K. Advance online publication; Nurse Education Today: 2020. Nursing education in a pandemic: Academic challenges in response to COVID-19. 10.1016%2Fj.nedt.2020.104471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emory J., Kippenbrock T., Buron B. A national survey of the impact of COVID-19 on personal, academic, and work environments of nursing students. Nursing Outlook. 2021;69(6):1116–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth S. Snapshot analysis shows ‘unprecedented’ decline in RN workforce. MedPage Today. 2022 https://www.medpagetoday.com/nursing/nursing/98372 , April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., Bilali A., Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2021;77(8):3286–3302. doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold Y. The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in a sample of California elementary and junior high school classroom teachers. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1984;44(4):1009–1016. doi: 10.1177/0013164484444024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S., Swan B.A., Jessie A.T. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the global nursing workforce. Nursing Economic$ 2020;38(5):231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Innovations in nursing education: Recommendations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (2020, March 30). https://nepincollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Nursing-Education-and-COVID-Pandemic-March-30-2020-FINAL.pdf

- Iwanicki E.F., Schwab R.L. A cross validation study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1981;41(4):1167–1174. doi: 10.1177/001316448104100425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski-Ozturk N., Martin B. Prelicensure nursing clinical simulation and regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic (in press). Journal of Nursing. Regulation. 2023 doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(23)00065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad S., Fitzgerald A., Deckers C. Nursing fundamentals—Supporting clinical competency online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2021;16(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.teln.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanahan M., Montalvo B., Cohn T. The perception of preparedness in undergraduate nursing students during COVID-19. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2022;42:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2022.06.002. 10.1016%2Fj.profnurs.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasater K.B., Aiken L.H., Sloane D.M., French R., Martin B., Reneau K., Alexander M., McHugh M.D. Chronic hospital nurse understaffing meets COVID-19: An observational study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2021;30(8):639–647. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marć M., Bartosiewicz A., Burzyńska J., Chmiel Z., Januszewicz P. A nursing shortage—A prospect of global and local policies. International Nursing Review. 2019;66(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/inr.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B., Kaminski-Ozturk N., Smiley R., Spector N., Silvestre J., Bowles W., Alexander M. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing education: A national study of prelicensure RN programs. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2023;14(1S):S1–S68. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(23)00041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S.E., Leiter M.P. In: Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Zalaquett C.P., Wood R.J., editors. Scarecrow Education; 1997. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M.D., Kutney-Lee A., Cimiotti J.P., Sloane D.M., Aiken L.H. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Affairs. 2011;30(2):202–210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A., Ryan N., Mattheus D., Knopf A., Abuelezam N.N., Stamp K., Branson S., Hekel B., Fontenot H. Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions on nursing education during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: A national sample. Nursing Outlook. 2021;69(5):903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimno, D., Wallach, H. M., Talley, E., Leenders, M., & McCallum, A. (2011, July). Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the 2011 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (pp. 262–272). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Murat M., Köse S., Savaşer S. Determination of stress, depression, and burnout levels of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2021;30(2):533–543. doi: 10.1111/inm.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council of State Boards of Nurses Number of nurses in U.S. and by jurisdiction: A profile of nursing licensure in the US. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from. 2023, February 24. https://www.ncsbn.org/nursing-regulation/national-nursing-database/licensure-statistics.page

- The National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers. (2016). National nursing workforce minimum datasets: Supply.https://nursingworkforcecenters.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/National-Forum-Supply-Minimum-Dataset_September-2016-1.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nurse.com 2022 nurse salary research report. 2022. https://www.nurse.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Nurse-Salary-Research-Report-from-Nurse.com_.pdf

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hospital and outpatient clinician workforce. 2022, May 3. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/9cc72124abd9ea25d58a22c7692dccb6/aspe-covid-workforce-report.pdf U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Řehůřek R., Sojka P. Gensim–python framework for vector space modelling. NLP Centre, Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic. 2011;3(2) [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt L., Heyen A., Greever-Rice T. Show me the nursing shortage: Location matters in Missouri nursing shortage. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2021;12(1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(21)00023-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour-Walsh A.E., Bell A., Weber A., Smith T. Adapting to a new reality: COVID-19 coronavirus and online education in the health professions. Rural and Remote Health. 2020;20(2) doi: 10.22605/RRH6000. Article 6000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley R.A., Ruttinger C., Oliveira C.M., Hudson L.R., Allgeyer R., Reneau K.A., Silvestre J.H., Alexander M. The 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2021;12(1S):S1–S96. [Google Scholar]

- Smiley R.A., Allgeyer R.L., Shobo Y., Lyons K.C., Letourneau R., Zhong E., Kaminski-Ozturk N., Alexander M. The 2022 national nursing workforce survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2023;14(2S):S1–S92. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Buckner M., Jessee M.A., Robbins V., Horst T., Ivory C.H. Impact of COVID-19 on new graduate nurses’ transition to practice: Loss or gain? Nurse Educator. 2021;46(4):209–214. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snavely T.M. A brief economic analysis of the looming nursing shortage in the United States. Nursing Economics. 2016;34(2):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J. 2020, March 31. There are not nearly enough nurses to handle the surge of coronavirus patients: here’s how to close the gap quickly. Health Affairs Forefront. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich B., Cassidy L., Barden C., Varn-Davis N., Delgado S.A. National nurse work environments – October 2021: A status report. Critical Care Nurse. 2022;42(5):58–70. doi: 10.4037/ccn2022798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Annual Population Estimates, Estimated Components of Resident Population Change, and Rates of the Components of Resident Population Change for the United States, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021 (NST-EST2021-ALLDATA) 2022. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/tables.html Retrieved October 7, 2022, from.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment and wage statistics. 2022, June 22. http://www.bls.gov/oes/oes_emp.htm

- Virtanen P., Gommers R., Oliphant T.E., Haberland M., Reddy T., Cournapeau D., Burovski E., Peterson P., Weckesser W., Bright J., van der Walt S., Brett M., Wilson J., Millman K.J., Mayorov N., Neslson A.R.J., Jones E., Kern R., Larson E., VanderPlas J., SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods. 2020;17:261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]