Summary

Cholesterol initiates steroid metabolism in adrenal and gonadal mitochondria, which is essential for all mammalian survival. During stress an increased cholesterol transport rapidly increases steroidogenesis; however, the mechanism of mitochondrial cholesterol transport is unknown. Using rat testicular tissue and mouse Leydig (MA-10) cells, we report for the first time that mitochondrial translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), Tom40, is central in cholesterol transport. Cytoplasmic cholesterol-lipids complex containing StAR protein move from the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM) to the OMM, increasing cholesterol load. Tom40 interacts with StAR at the OMM increasing cholesterol transport into mitochondria. An absence of Tom40 disassembles complex formation and inhibits mitochondrial cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis. Therefore, Tom40 is essential for rapid mitochondrial cholesterol transport to initiate, maintain, and regulate activity.

Subject areas: Biomolecules, Cell biology, Protein folding

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Cholesterol complex at MAM interacts with Tom40

-

•

Absence of Tom40 disassemble MAM complex

-

•

Tom40-StAR interaction allow cholesterol transport

Biomolecules; Cell biology; Protein folding

Introduction

Cholesterol has several roles in mammalian physiology, and disturbance of its homeostasis is associated with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. As a precursor of bile acids, cholesterol is essential for fat digestion in the liver and is also essential for steroid hormone synthesis in the adrenal and gonads,1 leading to the synthesis of mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, and sex steroids that are critical for carbohydrate metabolism and electrolyte balance, acute stress management, and sexual differentiation. Cholesterol transport from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is the rate-limiting step in steroid synthesis, initiating the synthesis of pregnenolone. Multiple proteins within endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or in mitochondria are involved in the synthesis of the other steroids.1

In an acute state, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) is synthesized in the cytoplasm and facilitates rapid cholesterol fostering from the outer to IMM in adrenal and gonadal cells.2 StAR is composed of a single functional domain with an α/β helix-grip fold containing a nine-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet forming a long hydrophobic cleft that can bind cholesterol.3 StAR after phosphorylation can foster several molecules of cholesterol without being imported into the mitochondria.4,5,6 Also StAR requires glucose regulatory protein-78 (GRP78) for its folding at the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM)7 and then interacts with voltage-dependent anion channel-1 (VDAC1)8 and voltage-dependent anion channel-2 (VDAC2)9 at the MAM-mitochondria junction for its import. Mutations in StAR cause lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia (Lipoid CAH), in which virtually no steroid hormones are synthesized, and the 46 XY fetuses are phenotypically female. In the absence of StAR, steroids are not synthesized, and fetuses born with a mutant StAR protein die prematurely due to salt losing crisis.10 Like lipoid CAH in humans, StAR knockout mice had the same female-looking external genitalia (regardless of sex), failed to grow normally, and died within a short period of time.11 Interestingly the mutant and wild-type StAR is processed into the mitochondria in a similar fashion.10 However, any unimported wild-type StAR cannot remain in the cytoplasm for a longer time.8 The mitochondrial translocases Tom2212,13 and Tim5014 is essential for its further translocation into mitochondrial matrix.15

Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) signaling organizes cholesterol ester hydrolase in the cytoplasm, resulting in corticosterone and testosterone production16 or adipocyte obesity-associated metabolic complication17; however, neither pregnenolone nor progesterone is dependent on ACSL4.16 In addition, the ubiquitous mitochondrial inner membrane protein, ATAD3A, promotes organelle development and regulates cellular functions in multicellular organisms by modification through the nucleoids.18,19,20,21 The absence of ATAD3A disrupts metabolism but does not play a crucial role in acute steroid regulation in mitochondrial cholesterol transport in adrenals and gonads.22 Therefore, StAR is the only critical and central protein in the cytoplasm to initiate the mitochondrial cholesterol transport for acute regulation of steroidogenesis.

The ER and mitochondria are both membrane-bound organelles; however, the ER comprises a nuclear envelope as well as a dynamic peripheral network of tubules and sheets. ER and mitochondria are physically connected23 by electron-dense structures,24 forming a protein complex that tethers the two organelles.25 In many mammalian cells, the ER contains a specialized subdomain, the mitochondrial-associated ER membrane (MAM)24 that physically connects it to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and provides a mitochondrial-ER axis that initiates metabolic signaling.26,27 Structurally, the MAM has the characteristics of an intracellular lipid raft, a membrane domain rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids with liquid-ordered structures interacting with various signaling proteins involved in a number of key metabolic processes.7,28,29 Therefore, the MAM is central for cholesterol loading onto the mitochondrial membrane and trafficking to inner mitochondria to initiate the steroidogenic and metabolic process.

Within membranes, cholesterol interacts with phospholipids and sphingolipid fatty acyl chains, resulting in increased membrane bilayer rigidity and reduced permeability to water and ions.30 Within “lipid rafts,” cholesterol concentrations can reach at least 10%; therefore, cholesterol is critical for the organization and function of the plasma membrane.31 Although it is less than that observed in the ER, a large amount of plasma cholesterol is transported into the inner mitochondria to initiate steroid metabolism by an unknown mechanism.32

Mitochondrial translocases present at the OMM or IMM and intermembrane space (IMS) are central for importing and sorting proteins to the appropriate subcompartments; however, the physiological role of these translocases is mostly unknown. The TOM complex consists of several smaller Tom proteins where Tom40 is the primary import channel,33 with an apparent molecular weight of the complex 400–600 kDa.33 Tom40 forms a pore with a negatively charged surface, attracting positively charged presequences to initiate translocation, including MAM proteins.34 For the first time, we show that Tom40 directly regulates mitochondrial cholesterol transport in the gonads. Using purified organelles isolated from rat testes, we showed the MAM complexes with Tom40. Next, Tom40 facilitates cholesterol transport into the mitochondria to initiate steroid metabolism. In the absence of Tom40, the MAM complex fails to assemble and mitochondrial cholesterol transport is ablated and thus the complete metabolic activity.

Results

Cholesterol-StAR moves cholesterol from the MAM to mitochondria

Membrane contact between the ER and mitochondria is crucial for lipid translocation between these organelles35; cholesterol also remains in the lipid rafts connecting the MAM. We examined whether the MAM can foster cholesterol into mitochondria by measuring pregnenolone synthesis. Rafts and MAM were isolated from rat testes (Figure S1A). Incubation of isolated testicular mitochondria with and without rafts resulted in 46 ng/mL pregnenolone synthesis (Figure 1A). However, the metabolic activity increased to 443 ± 23 ng/mL pregnenolone following incubation with MAM and mitochondria, which was 50% greater than that observed with StAR and mitochondria. The amount of mitochondrial extract applied in each sample was identical as evaluated by VDAC2 expression (Figure 1A, bottom panel). Because mitochondrial resident StAR is actively folded in the cytoplasm,7 minimal pregnenolone was synthesized by MAM isolates in the absence of mitochondria (17 ng/mL), suggesting that cholesterol associated with the MAM-resident StAR is likely transported into mitochondria. To further confirm this hypothesis, we overexpressed full-length StAR, N-62 StAR that cannot be imported without its targeting sequence and is present only in the MAM, and a mutant R182L StAR in nonsteroidogenic COS-1 cells co-expressing the F2-vector. F2 is a fusion of P450scc, ferredoxin, and ferrodoxin reductase.36 As a positive control, we also incubated the cells with 22R-hydoxycholesterol, which bypasses the need for StAR and shows the maximum capacity of a cell to synthesize pregnenolone. As shown in Figure 1B, N-62 StAR synthesizes 558 ± 39 ng/mL pregnenolone, which was nearly identical to that synthesized by full-length StAR (542 ± 28 ng/mL). Almost no activity was observed with the mutant R182L StAR (40 ± 9 ng/mL) (Figure 1B). Western blot of the transfected cells with a VDAC2 antibody showed almost similar expression, suggesting a similar number of cells were used in transfection (Figure 1B, bottom panel).

Figure 1.

Cholesterol transport through the MAM

(A) Top, Pregnenolone synthesis initiated by the MAM, mitochondria, and ER fractions following incubation with isolated mitochondria from rat testes. Bottom, Western blot of the mitochondrial extract used for pregnenolone synthesis with a VDAC2 antibody.

(B) Measurement of activity by transfection of full-length and N-62 StAR in COS-1 cells cotransfected with the F2 factor. 22R-hydroxy cholesterol, which bypasses the need of StAR and shows the maximum activity of a cell, was a positive control. Bottom, Western blot of the transfected cells with a VDAC2 antibody.

(C–E) Direct visualization of StAR localization through immunostaining of rat testes. StAR was mostly concentrated in the MAM within clusters (D); an enlarged version (red arrow) depicts StAR at the MAM, connecting to mitochondria (E).

(F) Analysis of the localization of MAM with a distance of 8, 11 and 18 nm of StAR clusters.

(G) Intensity analysis of the expression of different StAR forms in the MAM (37- and 32-kDa) and ER (37-kDa) fractions through Percoll density gradient fractionation and Western blotting with a StAR antibody.

(H) Cholesterol transport measured by activity (progesterone synthesis) following addition of different vesicle or lipid concentrations to the mix of MAM and mitochondria.

(I) Schematic presentation showing cholesterol transport to mitochondria from the MAM associated StAR with the lipid vesicles. The scale bars of the original figures in panels C and D are 200 nm. Data in panels A, B, G and H represent the means plus standard errors of the means (SEM) for three independent experiments performed at three different times.

Although cells tightly regulate cholesterol, it is not uniformly distributed.37,38 Nonvesicular transport helps to maintain organelle lipid levels39 and can move cholesterol quickly from rafts to the MAM and ultimately mitochondria. During an acute response, StAR fosters a large amount of cholesterol into mitochondria40; therefore, we hypothesized that it is associated with cholesterol rafts at the MAM. Immuno-EM experiments visualizing testicular OMM, IMM, and matrix (Figure 1C) showed that StAR was present in small clusters on the cytoplasmic side close to mitochondria (Figure 1D) suggestive of small rafts separated by 18 nm (Figure 1E shown in red arrow and Figure 1F). StAR gradually moves from MAM into mitochondria (Figures S1A–S1C). Western blotting of purified rafts and MAM with a StAR antibody showed 37-kDa and 32-kDa StAR in the MAM but only 37-kDa StAR in the raft (Figures 1G and S1C). The 30-kDa StAR was in mitochondria (Figure S1D). The 37 kDa StAR is a precursor present at the cytoplasm, but the 32-kDa protein is at the MAM and 30-kDa StAR is imported into mitochondria.7,9,15 Because raft-associated 37-kDa StAR is metabolically inactive (Figure 1A), cholesterol transport is likely due to 32-kDa StAR at the MAM or folded 37-kDa StAR at the MAM. To confirm that the MAM-associated cholesterol was transported, we next added lipid vesicles (1-palmitosyl-2 oleoyl-glycero-3 phosphocholine or POPC) or OMM-associated lipids externally onto the MAM and mitochondria mix and observed an increase in activity by 18-fold with vesicles than IMM lipids with cardiolipin or mitochondria only (Figure 1H), confirming that cholesterol molecules from the MAM were transported into mitochondria. To understand the duration of active StAR in the MAM available for cholesterol transport, we first isolated MAM and mitochondria from mouse Leydig cells (MA-10) and found higher levels of 32-kDa protein within 30 min after the addition of cAMP (Figure S1E). Levels of 37-kDa StAR appeared at 1h with an increase in 30-kDa protein at the same time (Figure S1E, top and bottom panel). The levels of 32-kDa StAR were unchanged with the appearance of newly synthesized 37-kDa protein in the MAM and 30-kDa StAR in the mitochondria, suggesting that the 32-kDa StAR is not imported immediately into mitochondria (Figure S1E, bottom panel). The levels of 37-kDa StAR gradually decreased with time (Figure S1F), corresponding with an increase in 30-kDa protein (Figure S1E, bottom panel). Until 30-kDa StAR within mitochondria is disposed, the newly formed 32-kDa protein may not be imported and may remain active for cholesterol transport, suggesting that there is a continuous and slow processing of cholesterol after an immediate surge during acute regulation (Figure 1I).

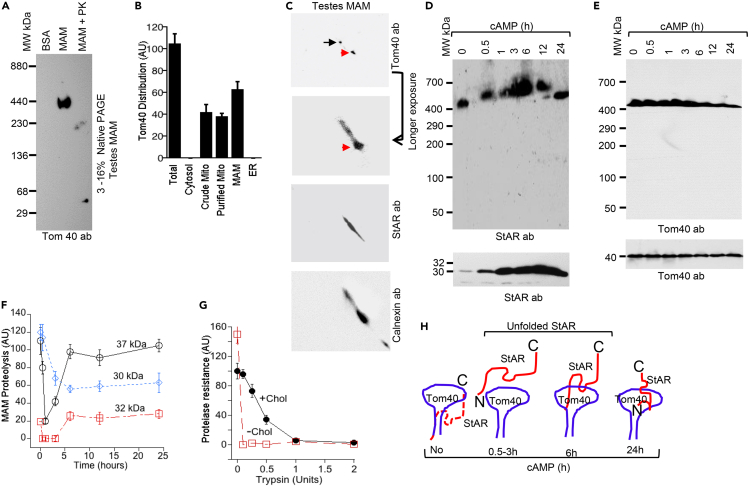

Tom40 maintains the network of interaction

ER and mitochondria are tethered, generating an undefined MAM organelle.41,42 To understand the role of Tom40 in association with the MAM, purified MAM from testicular tissues was solubilized with digitonin, and the complexes were separated by native gradient PAGE. A 450-kDa complex was detected by Western blotting with a Tom40 antibody (Figure 2A). The high molecular weight may be due to multiple small protein complexes resulting from MAM tethering, which occurs in clusters of six or more, incrementally spaced 13–22 nm apart spanning distances of 6–15 nm23 and thus easily proteolyzed (50 ng/mL PK; Figure 2A). Mass spectrometry of the MAM proteins observed in the 450-kDa Tom40-containing complex identified both ER- and mitochondrial-resident proteins (Table 1). Western blotting of organelle fractions and the MAM complex confirmed that Tom40 was at the mitochondria and MAM (Figures 2B and S2A). To determine the integrity of the complex, we used 2D native gradient PAGE (Figure 2C) followed by mass spectrometric analysis. Western blotting with Tom40 and StAR antibodies showed a predominant 140-kDa complex (Tables 2 and 3), confirming that the two proteins are associated in smaller complexes at the MAM.

Figure 2.

Tom40 complex is stabilized with cholesterol

(A) Analysis of rat testes MAM complex by Western blotting with a Tom40 antibody through native gradient PAGE.

(B) Quantitative analysis of Tom40 distribution pattern in the MAM complex detected by Western blotting with a Tom40 antibody.

(C) The Tom40 complex was excised from 1D native PAGE, Panel A, and was further analyzed through 2D native PAGE by Western blotting with Tom40, StAR, and calnexin antibodies independently. Enhanced exposure for 20 min (indicated with an arrow) showed the presence of a major complex of 230 kDa and the minor complex of 140 kDa (second from the top). Similar 2D native PAGE analysis and Western blotting with a StAR antibody showed only one major complex of 140 kDa (third from the top). Similar 2D analysis of the native PAGE of the MAM fraction and staining with calnexin antibody showed one major complex of 100 kDa and another complex of 240 kDa (bottom).

(D and E) Top, Kinetics of antibody shift experiment after stimulation with cAMP following incubation of StAR (D) and Tom40 antibodies with the MAM fraction isolated from rat testes, analysis through a native gradient PAGE, and staining with StAR (D) and Tom40 antibodies independently. Bottom (D) Western blot analysis of the MAM fraction following cAMP-stimulated MAM fractions and staining with a StAR and Tom40 antibody.

(F) Quantitative analysis of the total MAM complex, isolated after stimulation with cAMP for different times, were solubilized with digitonin and then proteolyzed with 0.5U of trypsin for 10 min followed by Western blotting with StAR antibody. The intensity of the protection of specific StAR expression is indicated directly.

(G) Analysis of CFS 35S-StAR import kinetics into isolated mitochondria for 30 min in the presence (black solid line, -·-) and absence (broken red line, --□--) of cholesterol followed by proteolysis with the indicated concentrations of trypsin for 10 min.

(H) Schematic presentation of mitochondrial import of StAR through Tom40 during acute regulation, where the red line indicates StAR and blue line indicates Tom40. In the absence of stimulation or prior to acute stress, StAR is not imported or formed a complex with Tom40. During acute regulation, newly synthesized StAR remains close to mitochondria and in a partially unfolded but stable conformation associated with cholesterol. As a result, the protein is partially proteolyzed quickly. Once the newly synthesized StAR is imported, further import continues for up to 6 h. The solid red lines are the newly synthesized StAR that will be imported. Data in panels B, F and G represent the means plus standard errors of the means (SEM) for three independent experiments performed at three different times.

Table 1.

Mass Spectrometric analysis of the 450-kDa complex isolated from 1D native gradient page

| Protein accession # | Description | Score | Protein coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI |10716563 | calnexin precursor | 450 | 10.5 |

| GI |51452 | heat shock protein 65 | 376 | 12.6 |

| GI |1304157 | 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein | 273 | 9.6 |

| GI |6735452 | B-ind1 protein | 255 | 12.2 |

| GI |5453832 | hypoxia up-regulated protein 1 precursor | 209 | 4.9 |

| GI |1922287 | enoyl-CoA hydratase | 199 | 12.4 |

| GI |238427 | VDAC1 | 171 | 14.5 |

| GI |488838 | CaBP1 | 165 | 9.7 |

| GI |188492 | heat shock-induced protein | 155 | 7 |

| GI |4191556 | RD114/simian type D retrovirus receptor | 153 | 6.8 |

| GI |114373 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha | 140 | 3.8 |

| GI |7657134 | dihydroxyacetone phosphate acyltransferase isoform 1 | 138 | 4.3 |

| GI |28336 | mutant beta-actin (beta ∼ -actin) | 121 | 12 |

| GI |6755967 | VDAC3 | 116 | 8.1 |

| GI |5174723 | TOM40 | 116 | 4.7 |

| GI |35493916 | dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 isoform 1 precursor | 106 | 5.4 |

| GI |292059 | MTHSP75 | 98 | 5.4 |

| GI |801893 | leucine-rich PPR-motif containing protein | 97 | 2 |

| GI |4506675 | dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase subunit 1 precursor | 89 | 4.1 |

| GI |2865466 | heat shock protein 75 | 84 | 4.8 |

| GI |727253a GI |1304314 |

Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthetase | 83 82 |

1.2 1.5 |

| GI |177216 | 4F2 heavy chain antigen | 76 | 4.7 |

| GI |4557303 | ALDH | 76 | 6 |

| GI |7657347 | mitochondrial carrier homolog 2 isoform 1 | 75 | 4.6 |

| GI |595280 | Rap1b | 70 | 6.5 |

| GI |131804 | Ras-related protein Rab-10 | 68 | 5.5 |

| GI |206553 | ras protein | 66 | 7.8 |

| GI |499158 | acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase | 66 | 4 |

| GI |34670 | hexokinase type 1 | 65 | 2.4 |

| GI |1050551 | rab7 | 65 | 6.3 |

| GI |8923415 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MARCH5 | 61 | 4.7 |

| GI |4758714 | microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 | 60 | 8.6 |

| GI |22209028 | Thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein 1 | 56 | 4.3 |

NOTE: Hits for common contaminants trypsin and keratin not included.

Observed 50% time.

Table 2.

Mass spectrometric analysis of the 230-kDa complex isolated from 2D native PAGE

Table 3.

Mass spectrometric analysis of the 140-kDa complex isolated from 2D native PAGE

We hypothesized that StAR remains in a dynamic folding state at the MAM for interaction with the lipid vesicles, as it is expressed on acute stimulation. To identify an intermediate state of folding, we performed antibody shift experiments of digitonin lysates of MAM isolated from cAMP-stimulated MA-10 cells by native gradient PAGE and Western staining with Tom40 and StAR antibodies independently. StAR-associated complexes were rapidly supershifted at 30 min, reaching a maximum level at 3 h and then folded (Figure 2D). As no high molecular weight was observed with the Tom40 antibody (Figure 2E), we concluded that StAR went through an early folding prior to its interaction with Tom40.7 To understand if the cholesterol present in the cytoplasm is responsible for the MAM complex formation, we stimulated MA-10 cells with cAMP for a different time from 30 min to 24h, isolated the total MAM, and incubated with 0.5U of trypsin for 10 min followed by Western blotting with StAR and Tom40 antibodies independently. The MAM complex formed within 30 or 60 min of cAMP stimulation was proteolyzed quickly as compared to the MAM complex resulted after longer stimulation, indicating that the newly synthesized StAR was partially unfolded for a limited time and thus proteolyzed (Figures 2F and S2B, top panel). Tom40 was not proteolyzed under these conditions, which may be due to its integration at the OMM (Figure S2B, bottom panel).

A cholesterol reservoir is maintained in the cytoplasm within vesicular membranes, modulating the function of membrane proteins.11,40,43 We reproduced similar membrane conditions by incubating cell-free synthesized (CFS) 35S-StAR with mitochondrial membrane and cholesterol followed by proteolysis with various concentrations of trypsin for 30 min. Cholesterol-containing StAR was significantly resistant to proteolysis with trypsin (Figure 2G, black solid line and Figure S2C, top panel). In the absence of cholesterol, StAR was proteolyzed immediately, suggesting that cholesterol helps StAR to associate with OMM (Figure 2G, red broken line and Figure S2C, bottom panel).40 These results are summarized showing different states of StAR folding during acute stimulation with the OMM prior to association and mitochondrial import in the presence of cholesterol (Figure 2H).

Tom40 is the rate limiting step for cholesterol metabolism

Cholesterol cannot pass through a proteinaceous import channel. To understand the role of Tom40 in cholesterol transport, we knocked down its expression in COS-1 cells overexpressing StAR and F2,10 and measured cholesterol transport by evaluating pregnenolone synthesis. Two Tom40 siRNAs reduced their expression by more than 90% (Figures 3A and S3A) without affecting GAPDH and VDAC2 expression (Figures 3A and S3A middle and bottom panels); it reduced 30-kDa StAR completely and also reduced the expression of 37-and 32-kDa StAR (Figure 3A top panel and Figure S3C). The absence of 30-kDa StAR suggests that mitochondrial import is dependent on Tom40. As mitochondrial metabolic activity is independent of StAR import,6 cholesterol transport should be uninterrupted in the absence of Tom40. StAR overexpression increased pregnenolone synthesis to 682 ± 34 ng/mL as compared to 25 ± 1.5 ng/mL in the absence of Tom40 or 62 ± 12 ng/mL after addition of mCCCP (Figure 3B), which dissipates mitochondrial membrane potential (-ΔΨ), accelerating StAR degradation. Activity in the presence of negative control siRNA was similar to that observed in absence of siRNA (671 ± 48 ng/mL). Thus, OMM-associated StAR is likely inactive due to misfolding in the absence of Tom40, preventing insertion of the incoming N-terminal protein.44 Western blot of the transfected cells confirmed minimal or no StAR expression with siRNA or mCCCP; however, expression with negative control siRNA was similar to cells overexpressing StAR (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Tom40 participation in cholesterol metabolism

(A) Top, Western blotting of COS-1 transfected cells with and without Tom40 knockdown with a StAR antibody. Second, Third and Bottom, Western blot of the StAR-transfected cells with or without Tom40 knockdown probed with Tom40 (Second), GAPDH (Third) and VDAC2 (Bottom) antibodies independently.

(B) Metabolic activity as measured by pregnenolone synthesis in StAR-transfected COS-1 cells with and without Tom40 knockdown.

(C) StAR expression following incubation of negative control siRNA, Tom40 siRNA and mCCCP in COS-1 cells by staining with a StAR antibody. Middle and Bottom, Western blot of the same transfected cells with Tom40 (Middle) and GAPDH (Third) antibodies independently.

(D) Localization of Tom22 through immunoelectron microscopy. Right hand panel (Figure Db) is the enlargement of a mitochondrion from left panel (Figure Da).

(E) Simultaneous localization of Tom40 (55 nm, red arrow) and Tom22 (15 nm, blue arrow) is the knockdown (Ec) and wild-type (Ea) cells probing with the antibodies together. Panel Eb and Ed is the enlargement of from panel Ea and Ec showing Tom40 and Tom22. The panels Da, Ea and Ec scale bars are 200 nm.

(F) Cell viability assay using MA-10 (Solid black line with open round circle, ⸺○⸺), ΔTom40 MA10 (Broken green lines with diamond, - - ◊- -), COS-1 (solid pink line with solid cross, ⸺×⸺) and ΔTom40 COS-1 (Red dotted line with solid dot … · …) cells over 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, 72 and 96 h. MCF-7 (Large broken blue line with blue square, ⸺□⸺) cells incubated with zeranol were a positive control showing toxicity after 24 h.

(G and H) Import of CFS 35S-SCC into the mitochondria of MA-10 (G) and ΔTom40 MA-10 (H) cells. Bottom panels (G, H) are the Western blots with a VDAC2 antibody showing total amount of mitochondria in both import experiments.

(I) Western blot of the Tom22 knockdown MA-10 cells with Tom40 (Top), VDAC2 (middle), and GAPDH antibodies independently.

(J) Activity of mitochondria isolated from MA-10 and Tom-40 knockdown MA-10 cells following incubation of the same amount of biosynthetic StAR. The water soluble 22R-hydroxy cholesterol, which bypasses the need of StAR to foster cholesterol into mitochondria and shows maximum activity, was a positive control. Data in panels B, F and J are the mean ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments.

Tom40 is crucial in mitochondrial protein import and its absence might alter mitochondrial architecture. Therefore, using Tom40 (with 55 nm gold particle) and Tom22 (with 15 nm gold particle) antibodies together and independently, we analyzed the impact of Tom 40 knockdown through immunoelectron microscopy. Tom22 was localized at the OMM (Figure 3Da) with an enlarged view of a mitochondrion showed Tom22 was at the OMM (Figure 3Db). In the absence of knockdown, Tom40 was highly labeled (Figure 3Ea), covering most Tom22 molecules at the OMM (Figure 3 Eb) as Tom22 was less visible independently (Figure 3Ec). With Tom40 knockdown, 15 nm Tom22 gold particles were most apparent (Figure 3Ec). An enlargement of Figure 3Ec shows dividing mitochondria with two Tom22 gold particles. Moreover, Tom40 knockdown did not significantly impact the viability of the steroidogenic MA-10 or nonsteroidogenic COS-1 cells over 96 h (Figure 3F). To validate the viability experiment, we also incubated tumorigenic MCF-7 cells with an estrogen stimulator (50 nM zeranol), showing decreased viability after 26 h (Figure 3F), consistent with a previous study.45 Therefore, loss of Tom40 did not impact mitochondrial structure or cell viability.

To understand the role of Tom40, we imported CFS 35S-labeled mitochondrial matrix resident cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (SCC) into mitochondria isolated from wild-type and Tom40 knockdown MA-10 cells. The 61-kDa wild-type 35S-SCC was imported and processed into 57- and 51-kDa proteins (Figure 3G, top panel) as observed previously.14,46 In Tom40 knockdown cells, 61-kDa SCC (Figure 3H top panel) could not be imported as no smaller protein fragment was observed. Expression of mitochondrial OMM resident, VDAC2, as well as GAPDH was unchanged irrespective of Tom22 knockdown (Figure 3I), confirming that the absence of translocase did not affect the mitochondrial structure. Therefore, Tom40 is responsible for the import of SCC (Figure 3H) and StAR into mitochondria (Figure 3C).

To further confirm that Tom40 knockdown ablated complete cholesterol transport and therefore metabolizing capacity, we purified the mitochondria from the knockdown and wild-type MA-10 cells and determined pregnenolone synthesis in the presence of biosynthetic StAR.47,48,49,50 We also incubated these mitochondria with 22R-hydroxycholesterol. As shown in Figure 3J, mitochondria from MA-10 cells with biosynthetic StAR synthesized 780 ± 32 ng/mL as compared to 921 ± 51 ng/mL with the incubation with 22R-hydroxy cholesterol. In contrast, incubation of StAR with mitochondria isolated from Tom40 knockdown cells produced only 110 ± 21 ng/mL pregnenolone, which is very similar to that observed with heat-inactivated MA-10 mitochondria or buffer alone (Figure 3J). Western blotting of all samples with a VDAC2 antibody showed a similar level of expression, confirming the presence of similar mitochondrial proteins in each reaction (Figure S3F). In summary, our data suggest that in the absence of Tom40, no cholesterol is transported into mitochondria for metabolic activity.

Tom40-StAR interaction is direct

To understand if Tom40 association with StAR is necessary for cholesterol transport, we performed an import experiment with CFS 35S-StAR protein into mitochondria isolated from wild-type and Tom40 knockdown cells. The imported mitochondrial complex was purified, solubilized with digitonin, and analyzed through a native gradient PAGE. We observed a 450-kDa complex (Figure 4A) with the wild-type cells but not with the Tom40 knockdown cells (Figure 4A). To further confirm that Tom40 and StAR interact directly, we performed in vitro chemical crosslinking with mitochondria isolated from rat testes and detected by Western blotting with StAR and Tom40 antibodies independently. We identified a 70-kDa band immediately with a 0.5 mM crosslinker. The intensity of the 70-kDa band increased with increasing crosslinker concentrations (Figure 4B). The amount of mitochondrial protein was similar in all the reactions as seen by similar levels of VDAC2 expression (Figure 4B, bottom panels). LC-MS/MS analysis (Figure 4C) of the 70-kDa band excised from the gel identified MAIQTQQSK for Tom40 (Figure 4D), confirming Tom40-StAR interaction during mitochondrial import.

Figure 4.

Direct identification of Tom40-StAR interaction

(A) StAR association with Tom40 followed by import. CFS 35S-StAR was imported into the isolated mitochondria from MA-10 cells with and without Tom40 knockdown. The import reaction complex was solubilized with digitonin and analyzed through 4–16% native gradient PAGE. The right panel is the longer exposure of the left.

(B) Direct interaction of Tom40 and StAR. In vitro chemical crosslinking with the indicated concentration of BS3 (crosslinker) for 30 min with mitochondria isolated from MA-10 cells and detected by Western blotting with Tom40 and StAR antibodies independently.

(C and D) LC MS/MS analysis of the Tom40 complex from panel B, confirming the presence of Tom40 in the complex.

(E and J) Localization of StAR and Tom40 by electron microscopy using antibodies specific for StAR (E, Red arrow) and Tom40 (G, Cyan arrow) or together (I). The right panels (F, H and J) are the enlarged images from left panels (E, G and I). The nanogold particle size 15 nm is for Tom40 and 55 nm for StAR. The scale bars in all the panels (E, F and H) are 200 nm.

(K) Electron microscopic characterization with no antibody (K). Right hand panel (L) is the enlargement of a mitochondrion from left panel (L).

(M) Schematic presentation showing that StAR (red solid line) is associated with the Tom40 import channel during mitochondrial import.

We next analyzed the specific localization of StAR and Tom40 in mitochondria using immunoelectron microscopy using a StAR antibody (Figure 4E) in combination with a Tom40 antibody (Figure 4G). As shown in Figure 4E, StAR was localized to mitochondria, and an enlarged view (Figure 4F) showed that the protein was specifically localized at the OMM and also in the IMS (Figure 4F). However, Tom40 was localized only at the OMM (Figure 4G), which was confirmed at higher magnification (Figure 4H). For colocalization analyses, we used 55-nm gold particles for StAR and 15-nm gold particles for Tom40. Probing with both antibodies simultaneously showed that Tom40 is localized only at the OMM, and StAR is mostly at the OMM or near the OMM with a few in the mitochondria, indicating that these proteins are present at similar locations (Figures 4I and 4J). In summary, these results suggest that StAR and Tom40 are present at the OMM, mostly overlapping with one another (Figure 4M).

Cholesterol transport depends on the folding state of its carrier protein(s)

Vesicles facilitate protein insertion into the lipid bilayer.51,52 We hypothesize that the StAR passenger sequence is folded upon N-terminal leader association with Tom40. In an α-helix, there are 3.6 amino acids per turn,53 but proteins with a rigid conformation have an average of 3.2 residues per turn.54 Approximately, 12 amino acids are present in an amphipathic helix, which is necessary to target a protein for mitochondrial import.55 To better understand the amino acids responsible for the integration of the StAR N-terminus via Tom40, we mutated the 10th residue, alanine, to threonine, creating A10T StAR. Alanine is a small, hydrophobic molecule while threonine is a polar molecule with a hydroxyl group capable of adapting to changes in folding. Because of the small change in the amino acid sequence of the N-terminus, the folding of the protein may be altered, which may affect the mitochondrial import process. Also, the speed of StAR import is related to the amount of cholesterol fostering into mitochondria.47 Therefore, we overexpressed A10T StAR and wild-type StAR in COS-1 cells and compared cholesterol transport capacity as measured by pregnenolone synthesis. A10T StAR produced 353 ± 28 ng/mL pregnenolone as compared to wild-type StAR that produced 509 ± 34 ng/mL pregnenolone (Figure 5A), suggesting that the cleavable N-terminal mutant interacted differently with Tom40, thereby reducing cholesterol transport. To validate these results, we analyzed the import kinetics of the CFS 35S-A10T StAR and 35S-StAR (wild-type) into isolated mitochondria. As shown in Figure 5B, the import efficiency of A10T StAR was higher than wild-type StAR, confirming that the N-terminal cleavable sequence is responsible for folding of the passenger protein.

Figure 5.

Import into the mitochondria is regulated through amino terminal folding

(A) Activity as measured by pregnenolone synthesis following wild-type StAR and A10T StAR overexpression in COS-1 cells cotransfected with F2 vector. Trilostane was added to inhibit 3βHSD2 activity.

(B) Import kinetics analysis of the mutant A10T (broken line in blue with open square, ---□---) and wild-type StAR (solid lines in red in open circle, ⸺○⸺) into the isolated mitochondria of MA-10 cells with the indicated time.

(C) Comparison of simultaneous competition of import between 35S-A10T StAR with wild-type StAR (---□---) and A10T StAR with 35S-StAR (⸺○⸺) into isolated mitochondria for 2 h, where both the A10T and StAR were incubated at the same time with the indicated pattern.

(D) Competition of import from panel C. Top, mitochondria (open cylinder) were incubated with cold StAR (red solid circle, •) and 35S-A10T StAR (blue solid circle, •) together performed from 5 min to 2 h 35S-A10T StAR was imported fast and thus occupied most of the matrix side leaving very little room for StAR. Signal of the imported fragment was high. Bottom, Mitochondria (open cylindrical box) were incubated with 35S-StAR (open circle, ○) and cold A10T StAR (•) for 5 min to 2 h. Cold A10T StAR was imported rapidly, resulting in limited 35S-StAR import. The imported signal was very weak as indicated by low intensity.

(E) Determination of import saturation limit. Mitochondria were incubated first with cold StAR for 30, 60 and 90 min and then 35S-A10T-StAR was added for 90, 60 and 30 min for a total of 2 h. In another set of experiments, 35S-StAR was imported for 30, 60 and 90 min and then A10T-StAR was added for 90, 60 and 30 min for a total of 2 h. The import efficiency was determined with the intensity of 30-kDa StAR. Data in panels A-C and E represent the means plus standard errors of the means (SEM) for three independent experiments performed at three different times.

To confirm further that the N-terminal cleavable amino acids dictate folding of the passenger protein, we performed competition experiments between 35S-StAR and A10T StAR into the isolated mitochondria that showed limited 35S-StAR mitochondrial import that may be due to faster A10T StAR import (Figure 5C, red solid line and Figure S4A). As expected, competition between 35S-A10T StAR with StAR showed increased A10T StAR import, which may be due to greater flexibility in folding (Figure 5C, blue broken line and Figure S4B). These results strongly support the view that mitochondrial cleavable sequences can interact differently with Tom40, impacting import kinetics (Figure 5D).

To confirm that mitochondrial import sites can be saturated in a variable fashion, we first imported unlabeled proteins for 30, 60, and 90 min, removed the unimported unlabeled proteins and then imported 35S-labeled proteins for 2 h (Figures 5E and S4C). Import of StAR first followed by 35S-A10T StAR import showed maximal StAR import at 30 min, but minimal import was observed at 90 min (Figure 5E). The StAR mitochondrial pause that coincides with amino acids 31–62 facilitates specific interaction with VDAC2,9 but a change in small nonpolar amino acid (alanine) to neutral threonine is likely to induce a minor change in folding thereby resulting a reduction in interaction with Tom40. To confirm these results, we performed the reverse experiment. As expected, the faster import efficiency of A10T StAR decreased 35S-StAR import even at 60 min, and at the end of 90 min, the import was minimal. Thus, increased occupancy of A10T StAR reduced availability of the transport machinery, resulting in minimal 35S-StAR import (Figures 5E and S4D). In summary, these results suggest that transport through Tom40 dependent on N-terminal folding of the import protein; rigid folding results in a slow unfolding and longer interaction with Tom40. Flexible A10T StAR may unfold faster, resulting in rapid mitochondrial import (Figure S4E).

Folding requirement for transport and activity through Tom40

Cholesterol molecules are crucial for StAR folding and stability.6,40 Analyzing the amino acid sequence, we hypothesized that the first 30 amino acids go through Tom40, while the next 32 amino acids, which have turn-helix-turn organization slow down during their entry through the Tom40. Thus, after inserting the N-terminus of StAR into the OMM, insertion pauses, resulting in slower mitochondrial entry (Figure 6A). To examine this further, we built several deletional constructs (Δ31-62) that retained the full or partial turn-helix-turn organization. For import analysis, we isolated mitochondria following the import of the 35S-labelled constructs and separated the unimported and imported fractions by centrifugation. To examine membrane integration, we extracted the mitochondria with 100 mM sodium carbonate, which interferes with protein-protein interactions but not lipid-protein interactions. Wild-type 35S-StAR was imported and integrated with lipid as shown in the pelleted fraction after carbonate extraction (Figure 6B). However, a similar analysis with 35S-Del-StAR (Δ31-62) showed no smaller molecular weight protein (Figure 6C), and it was present in the supernatant following extraction with buffer or sodium carbonate, suggesting that Del-StAR was not imported into mitochondria and unable to integrate into the mitochondrial membrane. Furthermore, Del StAR was largely inactive, synthesizing 48 ng/mL or 10% of the pregnenolone produced compared to wild-type StAR (Figure 6H) and a similar amount as the vector control. Therefore, these data suggest that the N-terminal folding plays a crucial role in fostering cholesterol into mitochondria.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of interaction of Tom40 with the turn-helix-turn sequence

(A) Schematic presentation of the helical region of the amino acids at the mitochondrial pause sequence of StAR. The amino acids generating the specific folding are shown in the arrow where 1–30 amino acids have no specific folding. The lipid binding passenger protein sequence from 63–285 has a turn-helix-turn folding.

(B–G) Wild-type (WT) and deletional mutagenesis of the indicated StAR fusions employed in mitochondrial import were labeled with 35S-methionine synthesized in cell-free system. Membrane association was analyzed first by washing with the buffer and separation via centrifugation. Membrane integration was analyzed by incubation of the membrane association fractions with sodium carbonate followed by separation by centrifugation. The pelleted fraction is denoted by P, supernatant fraction is S, and de novo CFS methionine-labeled proteins are labeled as CFS. The constructs included full-length (WT), Del StAR (Δ31-62), Mut 1 StAR (Δ31-45), Mut2 (Δ47-62), Del2 StAR (Δ38-62), and Del 11 StAR (Δ34-58).

(H) Metabolic activity of the wild-type and internal deletional mutants. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated deletion mutants and F2 factor.

(I) Summary of the mitochondrial import of wild-type and different N-terminal deletional mutants and their activity, as determined by pregnenolone synthesis. The broken lines show the deletion of amino acids from the indicated region, and the solid lines show the unchanged amino acids. The symbol Y denotes as a cleavage (Y), and no cleavage following mitochondrial import is denoted as N. The activity of the deletion mutants were compared with full-length StAR, which was set as 100. Data in panel H represent the means plus standard errors of the means (SEM) for three independent experiments performed at three different times.

To understand further the specificity of amino acids of this region essential for cholesterol fostering, we deleted several amino acids but retained either one turn one helix or two helixes and then examined mitochondrial import and activity. CFS 35S-labeled wild-type and different internal mutants Mut-1 (Δ31-45), Mut-2 (Δ47-62), Del2 (Δ38-62) and Del 11 (Δ34-48) StAR proteins were imported as observed with the cleaved smaller imported band (Figures 6D–6G). All other mutants showed no import into isolated mitochondria. Overexpression of wild-type and mutant StAR proteins in COS-1 cells showed that deletion of 47–62, 31–45, and 38–62 StAR retained 80% activity (Figure 6H). However, activity was reduced to 40% with the 35–62 deletion and was reduced further with the 34–62 deletion (Figure 6H), which retained only one turn. All other deletions retained at least one turn-helix combination. Therefore, these results suggest that N-terminal folding together with turn-helix might play a crucial role for retaining minimal activity, suggesting that the region might form a loop, providing a flexible portion to interact with Tom40 for a longer time during mitochondrial import (Figure 6I).

Discussion

Cholesterol flux in the adrenals and gonads is highly regulated.47 During an acute stress response, the immediate need for mitochondrial cholesterol is accompanied by the rapid mobilization of intracellular cholesterol stores in addition to enhanced hydrolysis of stored cholesterol esters, increased uptake of plasma cholesterol, and transport of free cholesterol into the mitochondria. Because StAR is responsible for fostering cholesterol into mitochondria, the presence of chaperones at the MAM ensures proper folding of StAR56,57 and, therefore, steroidogenesis.7 Unimported StAR is proteolyzed with the cysteine proteases.8 VDAC2, Tom40, and GRP78 are all part of the MAM complex and thus StAR is folded with these MAM proteins gradually prior to its import. Partially unfolded StAR is the most active form prior to entry into the mitochondria.47,58 During its transient residency at the MAM, StAR requires interaction with the Sigma-1 receptor,59 which facilitates interaction with VDAC2.59 The presence of a pause sequence in StAR is essential for interactions with Tom40, which, in turn, is retained at the OMM, thus increasing cholesterol fostering capacity into mitochondria.47,58 In the absence of the pause sequence, StAR (del-StAR) had no interaction with GRP78, VDAC1, and VDAC2, and finally Tom40. Because del-StAR was not folded properly, it was not imported into the mitochondria (Figure 6C); therefore, cholesterol was not transported as measured by pregnenolone synthesis (Figure 6H). The pause sequence requires a specific region or a combination of amino acids, which associates with Tom40 in the mitochondria (Figure 6I).

The two Tom40 β-barrel channels and α-helical transmembrane subunits play a central role not only for translocation but also regulation of metabolic activity.4,44 StAR picks up cholesterol from a source in the OMM with each molecule of cholesterol producing one molecule of pregnenolone. A large number of cholesterol molecules is associated with one molecule of StAR,40 suggesting that a change in folding is associated with the fostering process. Furthermore, cholesterol-containing rafts are central for Tom40 and StAR association, which stabilizes the MAM complex60 (Figure 2H). Therefore, fostering cholesterol requires interaction with lipid binding proteins, and Tom40 plays a central role for appropriate folding and thus cholesterol transport into the mitochondria. This network of interaction is essential as neutralization of negatively charged patches in the pore markedly impaired the function of the TOM complex.61

β-barrel proteins possess signals that can target the protein to mitochondria and can be recognized by mitochondrial machinery that have a β-hairpin element.62 Amphipathic helices are involved in different biological processes mediated by protein-protein interactions, where the ability to sense or induce curvatures is important for mitochondria that constantly undergo fusion and fission processes.41 The N-terminal portion of StAR is responsible for targeting it to mitochondria, but it is not the driving force to get into the Tom40 channel. A StAR pause produces favorable folding for optimal cholesterol fostering. During acute metabolic regulation, activity is delayed to accommodate the appropriate folding for interaction with cholesterol-trapped lipids. In the absence of Tom40, mitochondrial processing of StAR is inhibited, resulting in unimported, misfolded, and nonproteolyzsed StAR.8 The interaction remained specific where the folding of the pause region requires flexibility for interaction (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic presentation of the gradual integration of StAR into the mitochondrial Tom40 channel

StAR is initially folded at the MAM via GRP78 and then targeted to mitochondria. The pause sequence (amino acids 31–62) of StAR interacts with Tom40 in a loop formation, resulting in slower processing and changes in folding that are essential to gradually pass through the import channel. Once the pause sequence is completely inserted, StAR finally enters into the mitochondria.

The central receptor for initiating steroid hormone synthesis has been unknown for decades. StAR cannot foster cholesterol independent of GRP78 in the cytoplasm, VDAC1, VDAC2 and Tom22 at the OMM. GRP78 helps facilitate StAR folding in the MAM region of cytoplasm and requires interaction independently with VDAC1, VDAC2 and Tom22 at the OMM. However, the central protein capable of cholesterol transport regulating metabolic activity had not been identified. Therefore, we conclude that Tom40 is central for properly orienting StAR so that it can participate in cholesterol transport and in metabolic activity.

Limitations of the study

The study has been carried out with the mitochondria isolated from tissues or from mammalian cells for import experiments. All knockdown experiments were conducted with siRNA oligonucleotides with mammalian cell lines. Further studies examining Tom40 knockdown in specific organs followed by analysis of cholesterol movement through the mitochondria via a fluorescence tag are necessary to confirm these findings. We anticipate that targeted disruption of Tom40 in adrenals and gonads will abolish StAR expression and therefore limiting steroids synthesis. Because these molecules are necessary for survival, we expect the either the newborns would die prematurely after birth or will require steroid supplements immediately. However, it will difficult to knockdown Tom40 in both the adrenal and gonadal tissues. Despite these limitations, our study is the first evidence to lay the foundation of the essential role of Tom40 in steroidogenesis using cellular model.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER/CAT NO |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody resources | ||

| StAR | Home made | Ref: PNAS 96: 7250–7255, 1999. |

| VDAC2 | Home made | Ref: J Biol Chem 290: 2604–2616, 2015 |

| Calnexin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | CAT# sc-23954 |

| GAPDH | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | CAT# sc-47724 |

| Tom40 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | CAT# sc-365466 & sc-11414 |

| GRP78 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | CAT# sc-53472 & sc-13539 |

| Biological samples and buffers | ||

| Mitochondria | Homemade | Ref: STAR Protoc 4: 101996, 2023 |

| Mitoplast | Homemade | Ref: STAR Protoc 4: 101996, 2023 |

| Rat testis | Mercer University | IACUC # A1707013 (Dr. Z-Q Zhao) |

| Chemicals | ||

| Sucrose | FISHER SCIENTIFIC | CAT# 84097 |

| HEPES | SIGMA | CAT# H3375 |

| EGTA | CALBIOCHEM/SIGMA | CAT# 324628 |

| Na2HO4 | FISHER SCIENTIFIC | CAT# S375-500 |

| KH2PO4 | FISHER SCIENTIFIC | CAT# P380-12 |

| NaCl | FISHER SCIENTIFIC | CAT# AC447302500 |

| KOH | FISHER SCIENTIFIC | CAT# 501118107 |

| ATP | SIGMA | CAT# A26209 |

| Trilostane | SIGMA | CAT# SML 0141 |

| Percoll | SIGMA | CAT# GE17544502 |

| Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenylhydrazone (mCCCP) | Calbiochem | CAT# 555-60-2 |

| Oligofectamine | Thermo Fisher | CAT# 12252011 |

| Lipofectamine | Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher) | CAT# 18324–012 (New number 15338030) |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Calbiochem | CAT# 60-24-2 |

| DTT | SIGMA | CAT# D9779 |

| PMSF | Millipore Sigma | CAT# 329-98-6 |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Fisher | CAT# J61852.XF |

| EDTA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | CAT# 147865000 |

| Acrylamide | BioRad | CAT# 1610107 |

| Bis Acrylamide | BioRad | CAT# 1610201 |

| SDS | BioRad | CAT# 1610302 |

| Tris HCl [tris(hydroxymethyl)] aminomethane hydrochloride | VWR (JT Baker) | CAT# JT4107-05 |

| Tris (hydroxymethyl)aminomethane | VWR (JT Baker) | CAT# JT4102-05 |

| Cardiolipin (CL) | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAT# 710335 |

| 1,2-dipropionyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC) | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAT# 850302 |

| 1,2-diheptadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PE) | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAT# 830756 |

| 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAT# 850457P |

| Commercial reagents (kits) | ||

| Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kit | MP Biomedicals | CAT# 07170102 |

| Quick Start Bradford 1X Dye | BIO-RAD | CAT# 5000205 |

| Cell Viability Assay | Promega | CAT# G8081 |

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | Promega | CAT# L4600 |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set | Calbiochem | CAT# 539132 |

| Chemiluminescent Reagent | Thermo Fisher | CAT# 34579 |

| Recombinant DNA vectors and cDNAs | ||

| pSP64 -Vector | Promega | CAT# P1241 |

| pCMV4 -Vector | Stratagene | CAT# 211174 |

| StAR cDNA | Home made | Ref: PNAS 92: 4778,1995 |

| pcDNA™3.1 Mammalian Expression Vector | ThermoFisher | CAT# V79520 |

| Cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (SCC) | Home made | Ref: PNAS 83: 8962, 1986 |

| F2 (Cytochrome P450scc-Ferredoxin reductase-Ferredoxin) vector | Personal communication with Dr. Walter Miller | Ref: PNAS 91: 7247, 1994 |

| Biosynthetic StAR | Home made | Ref: Biochemistry 37:9762,1998 |

| Tom22 siRNA | Custom (Ambion/Invitrogen) | Ref: J Biol Chem 286:39130, 2011 |

| pSP64 -Vector | Promega | CAT# P1241 |

| pCMV4 -Vector | Stratagene | CAT# 211174 |

| Buffers | ||

| Glycerol Buffer | This paper | NA |

| Native Page Sample buffer | This paper | NA |

| Native complex isolation buffer | This paper | NA |

| Import Buffer | Home made | Ref: STAR Protoc 4, 101996, 2023 |

| Energy Regeneration Buffer | This paper | NA |

| Mitochondria Isolation Buffer | Home made | Ref: STAR Protoc 4, 101996, 2023 |

| Density gradient buffer | Home made | J Biol Chem 290: 2604–2616, 2015 |

| Mammalian cells and bacterial organisms/cells | ||

| E. coli DH 5α | Invitrogen (Thermo-Fisher) | 34210 (Now EC0111) |

| COS-1 | ATCC | CAT# CV-1 CCL-70 |

| MA-10 | ATCC | CAT# CRL-3050 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Himangshu S Bose (bose_hs@mercer.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate any new unique reagents. Reagents request will be made readily fulfilled following materials transfer policies of Mercer University School of Medicine.

Experimental model and subject details

Plasmid construction, cell culture, mitochondria isolation and transfection

Plasmid construction

For subcloning, human StAR cDNA was used as the template for PCR with specific combinations of sense and antisense primers as described previously.8 The accuracy of the constructs was determined by sequencing both strands of each clone.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats, 12 weeks of age, were purchased from Harlan/Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) and fed Purina chow (Harlan Teklad Global Diets) and water. The animals were housed and mechanically ventilated with oxygen-enriched room air using a rodent respirator (Harvard Rodent Ventilator Model 683); the rate was adjusted to 30 to 40 breaths/min, and tidal volume was set to 1.1 to 1.3 mL/100 g body weight. The body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a heating pad. Procedures for the isolation of testes were performed under sterile conditions (Mercer University IACUC number A1707013 to Dr. Z-Q Zhao).

Cell culture, transfection and activity

Both the MA-10 and COS-1 cells were purchased from ATCC prior to start of the project. It is the policy of the institution to have mycoplasma tested in every six months and update all the investigators to take necessary steps. Because of endogenous expression of StAR in MA-10 cells, we selected COS-1 cells for determination of activity through transfection of StAR expression vectors. Prior to transfection the cells were maintained in serum free media for 20 hours. Cells were cotransfected with F2 and plasmids expressing StAR, R182L StAR and all deletions mutants using lipofectamine reagent.10 The catalytically active fusion protein termed F2 consists of the cholesterol side chain enzyme, P450scc, and its electron-transport proteins, ferredoxin reductase and ferredoxin. As a positive control, the cells were incubated in the presence or absence of water soluble 22R-hydroxycholesterol (5 μg/mL) and 5 pmol of trilostane for 40 h. 22R-hydroxycholesterol bypasses the need for StAR and shows the maximum capacity of a cell to metabolize pregnenolone.10 Trilostane was incubated to inhibit 3βHSD2 activity to stop conversion of pregnenolone to progesterone. Media from transfected cells were collected after 48 h and assayed for pregnenolone by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (MP Biochemicals, CA).8,10,47,48

Method details

Compartmental fractionation of ER, MAM and mitochondria

To isolate mitochondria, the tissues were transferred to mitochondrial isolation buffer (250mM sucrose, 10mM HEPES, 1mM EGTA, pH 7.4), and diced into small pieces at 4°C. Tissue fractions were homogenized in a hand-held all-glass Dounce homogenizer with ten gentle up and down strokes, and the debris was removed by centrifugation at 3,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C and then followed procedure similar to fractionation from cells. In brief, steroidogenic MA-10 or nonsteroidogenic COS-1 cells were washed twice with PBS at room temperature and collected by centrifugation at 600 ×g for 10 min and then resuspended in 500 μL of 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4 for 30 min. Next, the cells were diluted further with 800 μL of mitochondrial isolation buffer and homogenized using 45 strokes in an all-glass Dounce homogenizer. The large debris and nuclei were separated by centrifugation twice at 600 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. Further centrifugation of the supernatant for 10 min at 10,300 ×g was performed to isolate the crude mitochondria. For the isolation of ER, the supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 ×g for 1 h.

To isolate pure mitochondrial fractions, the crude mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer to a final volume of 2.0 mL and layered the crude mitochondrial suspension on top of a medium containing density gradient buffer9 (225mM mannitol, 25mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1mM EGTA, 0.1% BSA and 30% Percoll [v/v]). After centrifugation at 95,000 ×g for 30 min, the mitochondrial fraction was isolated two-thirds of the way down the tube, and the MAM complex was found directly above the mitochondrial fraction. The mitochondrial fractions were isolated using a thin glass Pasteur pipette and washed to remove the Percoll by first diluting them with mitochondria isolation buffer followed by centrifugation twice at 6,300 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in mitochondria isolation buffer and stored at -86°C. For isolation of the MAM fraction, the complex was washed with isolation buffer to remove the Percoll by centrifugation at 6,300 ×g for 10 min followed by further centrifugation of the supernatant at 100,000 ×g. The resultant MAM fraction was resuspended in 0.5 mL of buffer containing 0.25M sucrose, 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 and 0.1mM PMSF, and stored at -86°C.

In vitro crosslinking

Isolated MAM or mitochondrial fractions were incubated with various concentrations of BS3 solubilized in water and crosslinking was performed at 4°C or at room temperature with varying crosslinker concentrations.7,8,9 The crosslinking reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 μL of 1.0 M Tris buffer pH 9.0.

In vitro protein import into mitochondria and protein complex on native gradient-PAGE

StAR, SCC or the different deletional mutant cDNA plasmids were cloned in pSP64 vector (Promega), translated with 35S-methionine or with cold methionine in TNT-rabbit reticulocyte system (Promega/Thermo Fisher) with SP6 polymerase at 30°C for 2 h.47 Ribosomes and associated incompletely synthesized polypeptide chains were removed by ultracentrifugation at 148,000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. Next, the import experiments were carried out with 100 μg isolated mitochondria resuspended in mitochondrial import buffer (125mM sucrose, 1mM ATP, 1mM NADH, 50mM KCl,0.05mM ADP, 2mM DTT, 5mM Na-succinate, 2mM Mg(OAc)2, 2mM KH2PO4 and10mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4.) and 2 μL of cell-free synthesized proteins incubated in a 26 °C water bath to a final volume of 100 μL for 2h. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1.0 μL 1mM mCCCP and an equal volume of 2× SDS-sample buffer. Partial proteolysis was done with 10 μg/mL PK for 15 min at 4°C, terminated by PMSF and heat inactivation followed by transferring to a boiling water bath. The import assays were analyzed by electrophoresing through SDS–PAGE, fixed in methanol/acetic acid (40:10), dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen.

For native gradient PAGE, the cell-free synthesized proteins were imported for 20 min at 26°C and mitochondria were reisolated extracting with digitonin buffer (1% [w/v] digitonin, 20mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1mM EDTA, 50mM NaCl, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 1mM PMSF) for 15 min on ice.63 An equal volume of native–PAGE sample buffer (100mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0, 500mM 6-amino-caproic acid) was added to the complex and subjected to gradient native-PAGE (4–16%) at 4°C at 100 V overnight. For identification of proteins in the complex, the native gel was then fixed in methanol/acetic acid (40:10), dried and exposed to a phosphorimager screen. To excise the complex, following overnight electrophoresis the gel was fixed in 10% acetic acid, washed with water, dried at 80°C for 45 min and then exposed to an X-ray film. The film and dried gels were clearly marked on all sides for excising the complex matching with the X-ray film after development. The native gels were also transferred to a PVDF membrane for western blotting.

Western blotting

After the protein samples or complexes were transferred to a polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane, they were blocked with 3% nonfat dry milk for 45 min, probed overnight with the primary antibodies, and then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or anti mouse IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Signals were developed with a chemiluminescent reagent (ThermoFisher). For direct visualization of the complexes, the gels were stained with Serva blue or Coomassie blue overnight at 4°C. Unless otherwise indicated, antibodies to Tom40, Tom22 and GAPDH were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX) or AbCam (Boston, MA) and the dilution were made as per company specification. StAR58 (1:5000),VDAC29 (1:3000) were homemade and SCC (1:1000) was a kind gift from Dr. Bon-Chu Chung (Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan).

Bioactivity of the Tom40 knockdown cells

The Tom40 knockdown experiments were carried out with the three different siRNA oligonucleotides with 30 or 60 pmol using oligofectamine as a carrier (Thermo fisher) following our procedure7 using the following siRNAs: siRNA 1 sense 5’GGAGCUGUUUCCAGUUUCAGtt3’ and antisense 5’CUGAACUGGAAACAGCUCCtt3’; siRNA2 sense 5’GGUGUCAAACUUACAGUCAtt3’ and antisense 5’UGACUGUUUGACACCtt3’; and siRNA 3 sense 5’GGCCAACUUCCUUUUUAAtt3’ and antisense 5’UUUAAAAAGGAAGUUGGCCtt3’. Following are the Tom22 siRNAs: siRNA 1 sense 5’GGUUAGCCUACUCUCUAAUtt3’ and antisense 5’AUUAGAGAGUAGGCUAACtt3’; siRNA2 5’GAAGAUGUACAGAUUUUCCtt3’ and antisense 5’GGAAAAUCUGUACAUCUUCtg3’; siRNA3 sense 5’CCUUGGCACAUGGAUCUAUtt3’ and antisense 5’AUAGAUCCAUGUGCCAAGGtt3’ used for knockdown expression and activity in MA-10 and COS-1 cells.9 Cholesterol transport was measured by determining pregnenolone synthesis as a measure of metabolic activity by RIA.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay using a commercially available kit59 (Promega, Madison, WI). MA-10, MA-10 Tom40 knockdown, COS-1, and COS-1 Tom40 knockdown cells were plated in a 96-well plate at an initial density of 3 × 103 cells per well for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 24 h of serum starvation, the culture media was changed to serum-free media, and the cells were incubated with MTT reagent for 3h and lysed with DMSO. As positive control, MCF-7 cells were incubated with 50μM zeranol for 24h45 with serum removed 2h prior. The absorbance at 550 nm was measured with the FlexStation3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Three independent set of experiments were performed; the results were normalized with respect to the number of cells.

In vitro steroidogenic activity with biosynthetic StAR

To isolate the biologically active form of N-62 StAR capable of transporting cholesterol into mitochondria was over expressed in E.coli following the procedure described before.48,64 The bacterial pellet was sonicated in a glycerol buffer48 (10mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol and 1mM PMSF) on ice for 1 min multiple times. The lysate underwent centrifugation at 18,000 ×g for 10 min and purified as described previously.48,64 To determine the activity, we incubated 1 μg biosynthetic StAR or MAM or ER with 20 μg isolated mitochondria in an energy regeneration buffer (125mM sucrose, 2mM ATP, 2mM NADH, 50mM KCl, 0.05mM ADP, 2mM DTT, 5mM Na-succinate, 2mM Mg(OAc)2, 2mM KH2PO4, 10mM creatine, 10 μL creatine kinase phosphate [4 mg/mL], 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37°C and measured pregnenolone synthesis by RIA.

Mass spectrometric analysis of the native gel complex

Digitonin-solubilized samples were electrophoresed in duplicate loading in the same orientation for overnight at 4 °C. Following electrophoresis, one part of duplicate was excised, wrapped in parafilm, and stored at −86 °C in a flat condition. Following Western blotting of the other part of the duplicate, the bands were excised matching with the autoradiogram. Next, the excised gel bands were destained, reduced with 10 mM DTT and alkylated with dithiothreitol and iodoacetamide, respectively. The peptides were extracted from the gel bands and dried followed by digestion overnight as described before.14,65 Next the samples were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (aq.). An aliquot of 5-μL was injected onto a Waters Symmetry trapping column (5 μM C18, 180 μm ID x 20 mm) (Waters, MA) and de-salted for 2 min at a flow rate of 10 μL/min followed by transfer to a Waters nanoAcquity column (3 μm Atlantis dC18, 100 Å pore size, 75 μm ID x 10 cm) (Waters). A linear gradient from 98% of 0.1% formic acid (aq.) to 45% acetonitrile (with 0.1% formic acid) was used to elute the peptides onto the Waters QTOF Premier mass spectrometer (Waters) in 40 min. The Waters nanoAcquity UPLC was used to provide a continuous flow rate of 0.35 μL/min. Data-dependent acquisition was utilized to acquire MS and MS/MS spectra. Peak lists were generated with ProteinLynx Global Server (version 2.2.5, Waters) and submitted to Mascot MS/MS Ion Search (version 2.3) using a mass tolerance of 0.1Da for MS spectra and 0.2Da for MS/MS spectra. Two missed trypsin cleavages were allowed for searching of the NCBI non-redundant protein database with consideration of oxidation of methionine and carbamidomethylated cysteine.

Isolation of lipid rafts and preparation of vesicles

To isolate the raft from testis, four testes were pooled from the same group of animals, and the tissues were transferred immediately to the mitochondrial isolation buffer [250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Hepes, and 1 mM EGTA (pH 7.4)] and chopped into small pieces in a petri-dish on ice. Tissue fractions were homogenized in a all-glass handheld Dounce homogenizer with 10 gentle up and down strokes, and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 3500g for 10 min and then by a procedure similar to fractionation from cells. When the MA-10 cells reached 80% confluency, they were transferred on ice, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and pelleted by centrifugation at 300 ×g for 5 min. Next, the cells or the cellular fractionation from tissues were incubated with 1.0 mL of 0.5M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 11) for 10 min and lysed with 1 mL of lysis buffer (1.0% (W/V) Triton X-100 in 25mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4 and 100mM NaCl) directly onto the plate. After the plates were placed in a gyrotary rocker for 20 min at room temperature, the lysate was transferred to a 2 mL all-glass homogenization tube followed by 15 up and down strokes and sonication for 10 seconds. Optiprep (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was diluted with the isolation buffer (150mM NaCl, 5mM DTT, 5mM EDTA, 25mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4 with a protease inhibitor cocktail). The density gradient at the bottom contained 35% and decreased to 30%, 25% and 20%. After 167 μL of cell lysate was gently laid on the bottom and centrifuged at 160,000 ×g in a TLA55 rotor (Beckman, Model TL-100) for 4 h at 4°C, the lipid raft fraction formed a white ring in the top layers and was collected with a very sharp Pasteur pipette.66,67 Testicular mitochondrial outer membrane and MAM lipid compositions were prepared maintaining their lipid composition.26,68

Transmission electron microscopy

Rat testes were gently washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, dehydrated with a graded ethanol series through 95% and embedded in LR white resin.7 The sections were blocked in 0.1% BSA in PBS for 4 h at room temperature in a humidified atmosphere and incubated with Tom40 (1:1,000) or StAR (1:2,000) antibodies in 0.1% BSA overnight at 4°C and performed semiquantitative analysis of the expression of StAR and Tom40.7 To avoid any error, we counted each image five times (n = 5), and SD was determined. Results were expressed as the number of gold particles per field of view. Field of view sizes were calculated using the quantitation function of the Gatan Microscopy Suite software (Gatan Inc, Pleasanton, CA).7

Figure preparation

Radioactive images were obtained from autoradiographic films or scanning with a phosphorimager (GE Health care/Amersham Biosciences) and no computer manipulation was applied or enhancement was performed on any figure.

Quantitation

The data were analyzed using Kalidagraph or Microsoft Excel and reported as mean ± standard error. Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate three different times and indicated in the figure legend. To compare quantitated images, we used one-way ANOVA. The p-values generated from each set of statistical tests were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05; the highest of the p-values are reported.

Acknowledgments

The work was previously supported by Startup package from the Department of Physiology and Functional Genomics, U of Florida, Gainesville; American Heart Foundation, March of Dimes, Navicent Foundation, Seed Grants from the Mercer U School of Medicine and a grant from National Institutes of Health, Savannah, GA. HSB is thankful to all the lab member and especially Dr. Brendan Marshall and Ms. Elizabeth (Libby) Perry for the all EM experiments.

Author contributions

HSB hypothesized, designed all the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper; HSB, MB, and RMW performed experiments. MB edited and performed all the experiments when HSB was in the Department of Physiology and Functional Genomics at the University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Published: March 11, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106386.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

This study did not generate any new computational program or sequence data.

References

- 1.Miller W.L., Bose H.S. Early steps in steroidogenesis: intracellular cholesterol trafficking. J. Lipid Res. 2011;52:2111–2135. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R016675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark B.J., Wells J., King S.R., Stocco D.M. The purification, cloning and expression of a novel luteinizing hormone-induced mitochondrial protein in MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cells. Characterization of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28314–28322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsujishita Y., Hurley J.H. Structure and lipid transport mechanism of a StAR-related domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:408–414. doi: 10.1038/75192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artemenko I.P., Zhao D., Hales D.B., Hales K.H., Jefcoate C.R. Mitochondrial processing of newly synthesized steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), but not total StAR, mediates cholesterol transfer to cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme in adrenal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46583–46596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X., Liu Z., Eimerl S., Timberg R., Weiss A.M., Orly J., Stocco D.M. Effect of truncated forms of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein on intramitochondrial cholesterol transfer. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3903–3912. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arakane F., Sugawara T., Nishino H., Liu Z., Holt J.A., Pain D., Stocco D.M., Miller W.L., Strauss J.F., III Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) retains activity in the absence of its mitochondrial targeting sequence: implications for the mechanism of StAR action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13731–13736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad M., Pawlak K.J., Burak W.E., Perry E.E., Marshall B., Whittal R.M., Bose H.S. Mitochondrial metabolic regulation by GRP78. Sci. Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bose M., Whittal R.M., Miller W.L., Bose H.S. Steroidogenic activity of StAR requires contact with mitochondrial VDAC1 and phosphate carrier protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:8837–8845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad M., Kaur J., Pawlak K.J., Bose M., Whittal R.M., Bose H.S. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane (MAM) regulates steroidogenic activity via steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)-voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (VDAC2) interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:2604–2616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.605808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose H.S., Sugawara T., Strauss J.F., III, Miller W.L., International Congenital Lipoid Adrenal Hyperplasia Consortium The pathophysiology and genetics of congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1870–1878. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612193352503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caron K.M., Soo S.-C., Wetsel W.C., Stocco D.M., Clark B.J., Parker K.L. Targeted disruption of the mouse gene encoding steroidogenic acute regulatory protein provides insights into congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11540–11545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bose H.S., Whittal R.M., Marshall B., Rajapaksha M., Wang N.-P., Bose M., Perry E.W., Zhao Z.-Q., Miller W.L. A novel mitochondrial complex of P450c11AS, StAR and Tom22 synthesizes aldosterone in the rat heart. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021;377:108–120. doi: 10.1124/jpet.120.000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajapaksha M., Kaur J., Prasad M., Pawlak K.J., Marshall B., Perry E.W., Whittal R.M., Bose H.S. An outer mitochondrial translocase, Tom22, is crucial for inner mitochondrial steroidogenic regulation in adrenal and gonadal tissues. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;36:1032–1047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01107-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose H.S., Gebrail F., Marshall B., Perry E.W., Whittal R.M. Inner mitochondrial translocase Tim 50 is central in adrenal and testicular steroid synthesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;39 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00484-00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stocco D.M., Clark B.J. Regulation of the acute production of steroids in steroidogenic cells. Endocr. Rev. 1996;17:221–244. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-3-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W., Hao X., Han L., Yan Z., Shen W.J., Dong D., Hasbargen K., Bittner S., Cortez Y., Greenberg A.S., et al. Tissue-specific ablation of ACSL4 results indisturbed steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 2019;160:2517–2528. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Killion E.A., Reeves A.R., El Azzouny M.A., Yan Q.W., Surujon D., Griffin J.D., Bowman T.A., Wang C., Matthan N.R., Klett E.L., et al. A role for long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase-4 (ACSL4) in diet-induced phospholipid remodeling and obesity-associated adipocyte dysfunction. Mol. Metab. 2018;9:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geuijen C.A.W., Bijl N., Smit R.C.M., Cox F., Throsby M., Visser T.J., Jongeneelen M.A.C., Bakker A.B.H., Kruisbeek A.M., Goudsmit J., de Kruif J. A proteomic approach to tumour target identification using phage display, affinity purification and mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arguello T., Peralta S., Antonicka H., Gaidosh G., Diaz F., Tu Y.T., Garcia S., Shiekhattar R., Barrientos A., Moraes C.T. ATAD3A has a scaffolding role regulating mitochondria inner membrane structure and protein assembly. Cell Rep. 2021;37:110139. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H., Kim D.-W. Deletion of ATAD3A inhibits osteogenesis by imparing mitochondrial structure and function in pre-osteoblast. Dev. Dyn. 2022;251:1982–2000. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilquin B., Taillebourg E., Cherradi N., Hubstenberger A., Gay O., Merle N., Assard N., Fauvarque M.-O., Tomohiro S., Kuge O., Baudier J. The AAA+ ATPase ATAD3A controls mitochondrial dynamics at the interface of the inner and outer membranes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:1984–1996. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00007-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murayama K., Shimura M., Liu Z., Okazaki Y., Ohtake A. Recent topics: the diagnosis, molecular genesis, and treatment of mitochondrial diseases. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;64:113–125. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannella C.A., Buttle K., Rath B.K., Marko M. Electron microscopic tomography of rat-liver mitochondria and their interaction with the endoplasmic reticulum. Biofactors. 1998;8:225–228. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Csordás G., Renken C., Várnai P., Walter L., Weaver D., Buttle K.F., Balla T., Mannella C.A., Hajnóczky G. Structural and functional features and significance of the physical linkage between ER and mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:915–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]