Summary

Physical activity in the form of aerobic exercise has many beneficial effects on brain function. Here, we aim to revisit the effects of exercise on brain morphology and neurovascular organization using a rat running model. Electrocorticography (ECoG) was integrated with laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) and applied to simultaneously detect CSD propagation and the corresponding neurovascular function. In addition, blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) signal in fMRI was used to observe cerebral utilization of oxygen. Results showed significant decrease in somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) and deceleration of CSD propagation in the EXE group. Western blot results in the EXE group showed significant increases in BDNF, GFAP, and NeuN levels and significant decreases in neurodegenerative disease markers. Decreases in SSEP and CSD parameters may result from exercise-induced increases in cerebrovascular system function and increases in the stability and buffering of extracellular ion concentrations and cortical excitability.

Subject areas: Cardiovascular medicine, Neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

ECoG-LSCI simultaneously measures cerebral blood flow and electrophysiological signal

-

•

Exercise increases cerebrovascular system function and cortical excitability

-

•

Exercise increases nerve conduction, and the CSD speed decreases

-

•

Regular exercise increases in levels of BDNF, NeuN, GFAP, and VEGF in the hippocampus

Cardiovascular medicine; Neuroscience

Introduction

Many studies have shown that regular exercise can improve cardiovascular health, reduce the risk of metabolic diseases, and prolong life. Regular exercise has also been shown to improve a person’s mood, relieve stress, and reduce the risk of dementia and depression.1 Aerobic exercise uses aerobic metabolism to meet energy demand during exercise, enhances endurance, expands cardiopulmonary function, and provides more oxygen and energy to the whole body.2 One of the most popular forms of exercise is intermittent exercise3 since this exercise method saves time, mitigates chronic diseases related to sedentary habits, and brings maximum oxygen content to the body. Aerobic training is very important for maintaining brain health because it may exert exercise-related effects throughout the nervous system via changes in blood flow, neurotransmitter concentrations, growth factors, neurotrophic factors, angiogenesis, glial cell health, and neurogenesis.4

Exercise also has an impact on cognitive behavior. Cognitive functions usually involve various synaptic proteins and neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus. The benefits of neurotrophic factors and brain function are well known in the literature.5 Moreover, hippocampal volume is related to spatial memory and an increase in hippocampal volume due to exercise will translate to an improvement in memory. BDNF plays an important role in synaptic plasticity, synaptogenesis, neurogenesis, and cell survival.6 The literature points out that after exercise, BDNF levels are increased in the hippocampus, which subsequently increases levels of full-length tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB), phosphorylated TrkB, and hippocampal synaptotagmin, leading to increases in neuroplasticity.7 BDNF has been shown to be necessary for long-term potentiation (LTP), a neural analog of long-term memory formation, and the growth and survival of new neurons.8 Inhibition of or defects in BDNF/TrkB signaling can impair memory function and eliminate LTP and neurogenesis. Physical exercise was also shown to be able to increase glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression as well as the number of GFAP-positive astrocytes in the frontoparietal cortex and striatum and stimulate the proliferation of astrocytes in the subgranular zone of the hippocampus of rodents.9 The mechanisms at these cellular and molecular levels are indicative of the signaling pathways from exercised muscles to the brain.

Cell proliferation in the brain is accompanied by an increase in nutritional requirements, which is met by stimulating the growth of new blood vessels in the cortex, cerebellum, striatum, and hippocampus. Vasculogenesis is indicated by the presence of molecules such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1). Previous research results have shown that systemic injection of IGF1 can effectively stimulate cerebral angiogenesis, while inhibition of IGF1 can reduce angiogenesis. IGF1 induces the formation of new blood vessels by regulating VEGF, which is a growth factor mainly involved in the formation and development of blood vessels. Aerobic exercise increases the production and release of IGF1 and VEGF in young mice, leading to the formation of new blood vessels.10

While mitochondrial biogenesis increases mitochondrial content in response to exercise, it is also vital to eliminate damaged mitochondria via mitophagy to maintain a healthy mitochondrial pool. Mitophagy is particularly important for the maintenance of vascular health, and accumulating evidence suggests that impaired mitophagy contributes to the pathogenesis of vascular diseases.11 Recent studies have demonstrated that PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy is enhanced after treadmill exercise, resulting not only in increased resistance to age-related and doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial alterations but also in attenuated amyloid-β (Aβ)-induced cognitive decline and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease (AD) animal models.12

Exercise can also prevent age-related degeneration in the hippocampus and maintain neuronal health.13 The hippocampus is a brain area that is particularly sensitive to age-related decline. The hippocampus shrinks with age, and this shrinkage indicates a shorter time to progress from mild cognitive impairment to AD. Studies have pointed out that compared with people with lower health levels, elderly people (i.e., 55–80 years old) with higher aerobic fitness levels generally have a larger hippocampus and show better spatial memory performance. In AD mouse models, running exercise can induce neurogenesis and protect myelin sheath in the mouse dentate gyrus. In mice evaluated using the Morris water maze, the AD mice that engaged in running exhibited better learning and spatial memory performance, an increased CA1 volume, and a greater CA1 area myelin volume than the control AD mice.14

Neurovascular function involves changes in regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) driven by neuronal activity in the same area. During nerve stimulation, local cerebral blood flow is affected by a variety of vasoactive substances around the nerve. These substances (such as adenosine, nitric oxide, and lactic acid) act on neurons, glial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, causing a series of complex physiological changes in neurovascular function. Neurovascular function is clinically important for understanding pathological brain imaging data in the context of, for example, cardiovascular diseases, vascular dementia, and AD.15 Through neurovascular function, localized changes in neuronal activity can be reliably mapped using changes in hemodynamics, such as CBF or blood oxygenation. Optical imaging techniques, such as laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) and fMRI, provide the necessary tools to detect and analyze regional hyperemic changes. Blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) imaging, a method commonly used in diagnostics to assess brain function, measures signal differences in the magnetic properties of oxygenated versus deoxygenated hemoglobin, indirectly reflecting neural activity based on the key principle of neurovascular coupling.16 LSCI can image cortical CBF changes in mobile animals, and this technique for imaging awake and active animals may provide critical information about currently unknown cerebral neuroscience issues in these animals. In this study, we used LSCI to assess cerebral flow velocities with excellent resolution.

Other studies have pointed out that physical exercise is related to migraine prevention, and the benefits of different types of exercise may vary. Moderate-intensity exercise (e.g., moderate continuous training) can prevent migraine17 better than high-intensity exercise. The phenomenon of cortical spreading depression (CSD) was first described by Leão et al.18 During the recording of brain electrical activity in anesthetized rabbits, Leão et al.18 noticed that strong electrical stimulation of a certain point on the surface of the cortex would cause a reversible reduction or inhibition of the cortical waves, which would fully recover after a few minutes. From the point of stimulation on the cortex, CSD reversibly propagates in all directions to increasingly distant cortical areas, accompanied by vasodilation of cortical blood vessels.19 In addition, a direct current (DC) slow potential change occurs in the cortical tissue, and this slow all-or-nothing type of DC signal is considered a sign of CSD.20,21 According to available animal and human experimental data, electrical silencing of the brain associated with CSD is caused by the depolarization of neurons and glial cells.22 The propagation speed of CSD in cortical tissue is approximately 2–5 mm/min, while the propagation speed of electrical signals in neurons is much faster at approximately tens of meters per second.23 The pathogenesis of some neurological diseases is presumed to be causally related to CSD. This is the case for migraine, traumatic brain injury,24 and stroke.25 Exercise has been shown to induce angiogenesis in the rat motor cortex, increase the cerebral blood volume, increase cerebral glycolysis and metabolism, alter glial and neuronal morphologies, and increase neuronal and synaptic connections. It also causes angiogenesis to increase the distance between cells, which may be responsible for the decreased number/velocity of CSD. Physical exercise promotes metabolism and oxidative reactions, which also lead to a decrease in the speed of CSD transmission. In addition, physical exercise stimulates increased serotonin release in the brain, which exerts an antagonistic effect on the spread of CSD. These changes in ion homeostasis all affect the speed of CSD propagation.26 Many nutritional, pharmacological, environmental, and hormonal manipulations have been shown to increase or decrease the rate of CSD in the study by 23,27Shabir et al.28 This evidence supports the conclusion that CSD propagation velocity is a useful indicator for assessing the electrophysiological aspects of brain signals. To simultaneously examine neurovascular function in target brain regions, electrocorticography (ECoG) is an ideal approach that can be used to acquire real-time neurological signals from specific large-scale brain areas to evaluate somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) changes. In addition, cutting-edge optical imaging technologies, such as diffuse optical imaging (DOI) and LSCI, have been utilized to evaluate the hemodynamics of relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in stroke pathology.29 The DOI technique has been shown to be capable of measuring blood flow and oxygenation.30

In this study, we used potassium chloride (KCl)-induced CSD as a marker of neurovascular responses in the brain and revealed differences in the brain functions of sedentary (SED) and exercised (EXE) animals.21,22,23 We integrated ECoG recording into the developed LSCI system (hereafter referred to as ECoG-LSCI) to comprehensively assess neurovascular functions. The forepaw electrical stimulation response was recorded using ECoG, and 4 M KCl was used to induce CSD to observe neurovascular responses in the brains of rats in the SED and EXE groups. In addition, we used western blotting to analyze changes in neurotrophic factors and neurodegenerative disease markers in the brains of SED and EXE rats from the perspective of identifying cellular and molecular mechanisms.

Results

Treadmill exercise and ECoG-LSCI changes in rats

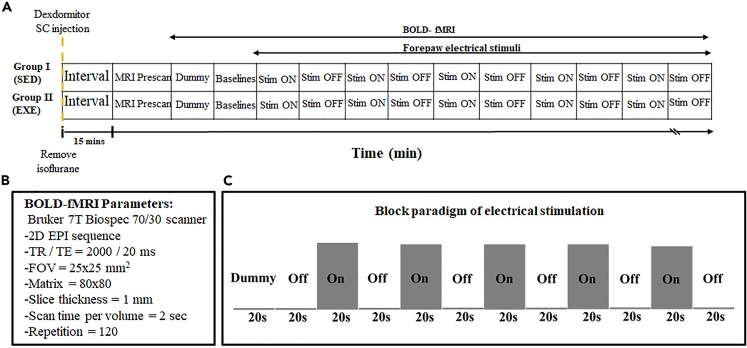

To investigate whether treadmill exercise improves brain function, we used an ECoG-LSCI system (Figure 1) to assess a rat running model (Figure 2; Video S1). After 4 weeks of training, a craniotomy was performed on the rats for ECoG-LSCI data recording. BOLD-fMRI (Figure 3) was used to confirm LSCI results. Representative SSEP waveforms,31 including the P1 amplitude, N1 amplitude, P1 latency, and N1 latency, from one SED animal and one EXE animal, are shown in Figures 4A and 4C. Average evoked potentials are shown in Figures 4B and 4D and were as follows: SED group: P1 amplitude, 2107.93; N1 amplitude, −1437.37; P1 latency, 4.80; N1 latency 36.14; EXE group: P1 amplitude, 557.96; N1 amplitude, −732.37; P1 latency, 6.31; and N1 latency, 33.73.

Figure 1.

ECoG-LSCI system and electrode schematic diagram

The ECoG-LSCI neurovascular imaging system was used to assess ECoG signals, CBF, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation levels. The system uses electrical stimulation to detect changes in brain wave signals as electric shocks are delivered to the rat’s front paws, and ECoG recordings from the implanted screws in the S1FL cortex can receive neural activity signals. At the same time, through the LSCI imaging system, wavelength 660 nm laser source systems are used to irradiate the light source on the cortex after the craniotomy. The CCD camera is used to capture the image to the computer, and MATLAB is used to further analyze the cerebral blood flow and hemoglobin oxygen saturation. The shape of the skull and the position of the spiral electrode is shown; the figure includes an ECoG record from the S1FL (AP = +1.0 mm, ML = +4.0 mm) cortex, the position of a reference electrode, and the position where KCl is administered (upper right of the reference electrode shown at the bottom right).

Figure 2.

ECoG-LSCI recording and experimental schedule of peripheral sensory stimulation

(A) Rats were divided into two groups: SED and EXE. The EXE group underwent a three-day adaptation period at a speed of 30 cm/s. The treadmill exercise was performed five times a week for a period of four weeks. The inclination of the treadmill is 0°. The end of each treadmill channel was supplied with 0.5 mA of electricity, the speed was 35 cm/s in the first two weeks, and the speed was 40 cm/s in the next two weeks. The training program included two periods of exercise, 15 min each time, with a 10-min rest period in between.

(B) Physiological system and laser speckle contrast imaging system, combined with electrical stimulation to detect S1FL, uses 4 M KCl to induce CSD, followed by collecting CSD data for 40 min, including the brain blood flow response.

(C) The hemisphere was revealed, and the position of S1FL was determined. There were three main holes: the ECoG electrode, the reference electrode, and hole to deliver KCl.

(D) Detection of electrical signals in the S1FL, following a 30-s 6-mA electrical stimulation.

(E) Electrophysiological system and laser speckle contrast imaging system, combined with electrical stimulation produced S1FL activity included delivery of a total of three repetitions, with each 60-s repetition containing 30-s of 6-mA electrical stimulation.

Figure 3.

Experimental design of electrical stimulation

(A) The task paradigm in the SED and EXE groups. After injecting dexmedetomidine, the fMRI scan was started with a 25-min waiting interval. Then, the isoflurane supply was stopped, and the MRI prescan was approximately 10 min.

(B) The BOLD-fMRI parameters.

(C) The fMRI paradigm including the block-design pattern of electrical stimulation. In the electrical stimulation, we designed 5 blocks in each scan session after a 20-s dummy scan, and each block encompassed 20-s rest (Off) and 20-s electrical stimulation (On) on left front paw. The electrical stimulation parameters were 4 mA with 12 Hz during the On period using stainless steel electrodes.

Figure 4.

ECoG recorded electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulation was detected in the S1FL, and a total of three 60-s repetitions were delivered. MATLAB was used to analyze these data to obtain calibration evoked potential and average evoked potential graphs to determine the baseline and average shock responses, respectively. Electrical stimulation parameters included an amplitude of 4 mA, a pulse width of 0.2 ms, a frequency of 3 Hz, and a duration of 30 s; the calibration evoked potential was determined and the start of electrical stimulation for 30 s occurred at the 10th s.

(A) Calibration evoked potential in the SED group.

(B) Average evoked potential in the SED group.

(C) Calibration evoked potential in the EXE group.

(D) Average evoked potential in the EXE group.

Our data show examples of changes in rCBF during KCl-induced CSD in SED and EXE animals, as shown in Figures 5B and 5D. The ROIs selected for the rCBF calculations are shown in Figures 5A and 5C. The CSD speed in an EXE animal (3.90 mm/min) was lower than the CSD speed in an SED animal (7.32 mm/min).

Figure 5.

CSD metabolism time and speed calculations

LSCI detects changes in cortical blood flow using KCL-induced CSD. Before adding KCl, LSCI and ECoG signals were recorded for 10 min as the baseline level, and 4 M KCl-induced CSD for 60 min. The left half of the figure is centered on bregma, and the 2 points are marked with P1 and P2. The distance of 3 mm is the scale used to calculate CSD speed, and two circular ROIs in the cerebral cortex are used to calculate the blood in this area. The amount of flow change with time is based on the distance between the two points and the time difference between the peaks in this cortical spot; the actual distance is divided by the time to calculate the speed. The arrow represents the direction of CSD movement.

(A) LSCI photo of the brain of a rat in the SED group.

(B) CSD over time in the SED group.

(C) LSCI photo of the brain of a rat in the EXE group.

(D) CSD over time in the EXE group.

Example images of changes in rCBF during KCl-induced CSD in SED and EXE animals before smoothing for speed calculation are shown in Figures 6A and 6C. The images in Figures 6B and 6D (Videos S2 and S3) show the corresponding rCBF distribution calculated from speckle images over a time period during CSD. In this example, 10 peaks were generated during CSD in the SED animal, while only 5 peaks were generated in the EXE animal. Comparisons of the SSEP amplitudes and latencies are shown in Figures 7A and 7B, respectively. The SSEP amplitude in the EXE group was significantly lower than that in the SED group (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the latency in the SED group and the EXE group. A comparison of the CSD count and CSD speed is shown in Figures 8A and 8B, respectively. Both CSD count (p < 0.05) and CSD speed (p < 0.01) were significantly lower in the EXE group than in the SED group.

Figure 6.

LSCI records of KCl-induced CSD cerebral blood flow

KCl-induced CSD cerebral blood flow changes were recorded through LSCI, and 2 images per second (frame rate 2) were recorded for a total of 2400 s. All images were analyzed and values calculated using MATLAB to analyze CBF to determine CSD generating conditions.

(A) Analysis of cerebral blood flow in the SED group.

(B) Dynamic changes in blood flow in the SED group.

(C) Analysis of cerebral blood flow in the EXE group.

(D) Dynamic changes in blood flow in the EXE group. The red arrow represents the occurrence of a CSD event over time. The area of low blood perfusion is dark blue, and the area of high blood perfusion is dark red. The red circles in (B) and (D) indicate the selected ROI for the analysis and yellow frame indicates the bright-field photo. Videos of the changes in blood flow are shown in Videos S2 and S3 for (B) and (D), respectively.

Figure 7.

Exercise is good for optimizing brain conditions

The electrophysiological results were analyzed by MATLAB. Column analyses (SED and EXE; N = 6 in each group) were analyzed by GraphPad Prism, and the difference between the SED and EXE groups was analyzed by an unpaired t test.

(A) Differences in potential between the SED group and the EXE group; SED vs. EXE, ∗∗p < 0.01.

(B) Conduction latency; SED vs. EXE, p = 0.2398, no significant difference. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Figure 8.

Exercise is good for optimizing brain conditions

After KCl-induced CSD was analyzed by MATLAB, GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis of the data in columns (SED and EXE; N = 6 in each group). Unpaired t-tests were used to analyze the differences between the SED and EXE groups. (A) CSD number; SED vs. EXE, ∗p < 0.05. (B) CSD speed in the SED group and EXE group; SED vs. EXE, ∗∗p < 0.01. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Brain activation maps assessed by BOLD-fMRI after forepaw electrical stimulation

The activated regions during electrical stimulation were in the S1 for both the SED and EXE groups (p < 0.01), as shown in Figures 9A and 9B. Changes in BOLD signals over time in the EXE group showed less percent signal change (0.51 ± 0.08%) than that in the SED group (1.14 ± 0.45%). There was a significant difference between the EXE and SED groups according to the t test (p < 0.0038).

Figure 9.

Representative fMRI results showing the exercise effect

(A and B) The electrical stimulation-induced fMRI activation maps in the SED and EXE groups; ∗∗p < 0.01. The arrow indicates that the significantly active region is the somatosensory cortex (S1). The words in green mark the left (L) and right (R) hemispheres. The z axis number, from negative to positive, represents the anatomical orientation from caudal to rostral.

(C) The time course of BOLD signal changes from the significantly active region in the two groups; the regions with the green background indicate the time of electrical stimulation. Blue line: EXE group; Red line: SED group.

Treadmill exercise increased the relative protein levels of neurotrophic factors in the cortex and hippocampus

In addition to analyzing the effects of exercise on the brain from a neurovascular perspective, we also analyzed it at the cellular level. An example western blot of protein expression in the cortex and hippocampus of an SED vs. EXE animal is shown in Figure 10A. The quantified data are shown in Figures 10B and 10C for the EXE and SED groups (N = 4). Multiple t test results showed significantly increased NeuN (p < 0.001) in the cortical tissue from the EXE group (Figure 10B). There were no significant differences in neurotrophic factor (i.e., BDNF) and GFAP levels in the cortex. Mitophagy plays a key role in maintaining mitochondrial quality by degrading aged, damaged, or dysfunctional mitochondria. The PINK1 antibody was used in this study to detect the PINK1/Parkin pathway, which plays a pathogenic role in neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Parkinson disease. Exercise can enhance mitophagy activity in the hippocampus, which efficiently ameliorates pathological phenotypes of amyloid precursor protein (APP)/PS1 transgenic mice. For example, it has been shown that PINK1 levels were significantly increased in the hippocampal mitochondria fractions of APP/PS1 transgenic mice, and exercise significantly reduced the level of PINK1 in the APP/PS1 transgenic mice but not in the wild-type animals. Our results showed that PINK1 was not significantly different in the cortical tissue from the SED and EXE groups. Exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis requires VEGF. Declines in learning and memory functions have been related to decreased adult hippocampal neurogenesis.32 VEGF is an important element of the somatic regulator of adult neurogenesis. These somatic signal networks can be independent of the central regulatory network. However, our results showed that there was no significant difference between cortical tissue VEGF levels in the SED and EXE groups. The literature points out that the process of addition or replacement of adult hippocampal neurons is closely related to hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory.33 Physical activity has also been shown to cause a robust increase in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, a brain area important for learning and memory. Consistent with these findings, our results showed that hippocampal expression levels of many proteins, including BDNF, GFAP, NeuN, and VEGF, were significantly higher in the EXE group than in the SED group (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the hippocampal expression of PINK1 between the SED and EXE groups (Figure 10C).

Figure 10.

Effects of running on the expression of neurotrophic factors vary in the cortex and hippocampus

(A) Representative western blot images of BDNF, GFAP, NeuN, PINK1, VEGF, and beta-actin (N = 4 in each group).

(B and C) Quantification of BDNF, GFAP, NeuN, PINK1, VEGF, and beta-actin levels. Beta-actin was probed as an internal control. In the western blot images, “-” indicates the SED group and “+” indicates the EXE group. Multiple t tests, one per row; ∗∗∗p < 0.001 and ∗p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Effects of treadmill exercise on neurodegenerative disease-related proteins

Exercise can increase neurogenesis and promote the production of nutrient factors in the brain. Physical exercise has been suggested as one of the best lifestyle interventions for both healthy aging individuals and patients with neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and Parkinson disease (PD). Cerebral amyloidosis is the first marker used to detect the possibility of AD. It is known that α-secretase (ADAM10) will compete with β-secretase (BACE1) for APP,34 and the nonamyloid pathway will be affected by β-secretase. These secretases contribute to AD. The literature points out that the induction of neurogenesis alone cannot improve cognition in AD mice, but exercise can improve the neuronal environment and induce neurogenesis.35 Although most of the literature uses gene-deficient mice as a model to study the effects of exercise training, our study uses normal rats that underwent exercise training to study the effects of exercise-induced neuronal secretases that cleave APP to produce sAPPα. sAPPα can provide beneficial neurotrophic substances, while the amyloid pathway is cleaved by β-secretase to produce sAPPβ. sAPPβ is released to the extracellular matrix, then γ-secretase will continue to cleave the protein, and finally aggregates of Aβ-like protein will be produced. Aggregation of Aβ plaques stimulates upstream- and downstream-related proteins. We analyzed the expression levels of the AD-related proteins ADAM10, BACE1, sAPPα, and sAPPβ in the cortex and hippocampal tissues, as shown in Figure 11A. Multiple t-tests showed that sAPPα expression in the cortical tissue was significantly higher in the EXE group than in the SED group (p < 0.01), and sAPPβ expression in the EXE group was significantly lower than that in the SED group (p < 0.01). Cortical BACE1 in the EXE group was significantly higher than that in the SED group (p < 0.05) (Figure 11B). However, hippocampal ADAM10, BACE1, sAPPα, and sAPPβ levels were not significantly different between the EXE and SED groups, although the trend was similar to that in the cortical tissue (Figure 11C).

Figure 11.

Effects of running on the expression of neurodegenerative disease-related factors in the cortex and hippocampus

(A) Representative western blot images of ADAM10, BACE1, sAPPα, sAPPβ, and beta-actin (N = 4 in each group).

(B and C) Quantification of ADAM10, BACE1, sAPPα, sAPPβ, and beta-actin levels. Beta-actin was probed as an internal control. In the western blot images, “-” indicates the SED group and “+” indicates the EXE group. Multiple t tests, one per row; ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

Neurovascular effects of treadmill exercise

SSEPs can be used to evaluate pathological changes in the entire motor neural network of the brain. Exercise can increase the reception and release of neurotransmitters by neurons, which internally transmit information using action potentials and then relay information to other neurons at synapses. After exercise, the number of neurons in the cerebral cortex increases. Neurons propagate information in the form of electrical signals. Ion channels in the cell membrane allow the movement of potassium and sodium ions, causing changes in the membrane potential. Our results showed that the SSEP amplitude was decreased in the EXE group (P1 amplitude: 557.96, N1 amplitude: −732.37) compared to the SED group (P1 amplitude: 2107.93, N1 amplitude: −1437.37). The literature suggests that high SSEP amplitude is a poor indicator in epilepsy research because it is associated with increased excitability and a lowered seizure threshold. In the case of epilepsy, an exercise-induced reduction in SSEP amplitude would be beneficial. In a kindling model of epilepsy, exercise was shown to reduce excitability and increase the number of stimuli required to induce seizures.36 In EXE animals, a model in which signaling from motor networks is increased in frequency, synaptic plasticity may reduce excitability, which is reflected in reduced SSEP amplitudes.

In addition to the effects on SSEPs, we demonstrated that exercise had an effect on KCl-induced CSD. Both CSD count and speed were significantly lower in the EXE group than in the SED group (Figure 8). Since CSD has been observed in diseases such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, and migraine,37 we questioned whether exercise exerts neuroprotective benefits through its suppression of CSD. In patients with TBI, recurring CSD has been observed.38 CSD has been correlated with depletion of brain glucose levels, which contributes to poor neurologic outcomes.39 In a TBI animal model, the frequency of CSD was related to trauma intensity.40 Following ischemic stroke, the CSD number41 and total duration of CSD42 were shown to be related to tissue damage. Migraine has also been associated with CSD, and migraine medication has been shown to suppress CSD.43 CSD in migraine is proposed to be an indicator of neuronal hyperexcitability,44,45 which is increased in patients with migraine. Exercise, however, can reduce neuronal excitability and has been shown to decrease CSD speed.46 Although these findings may lead us to hypothesize that the suppression of CSD is beneficial, Yanamoto et al. have shown that CSD preconditioning is neuroprotective against ischemic stroke47 and that CSD stimulates neurogenesis.48 Thus, additional studies are necessary to determine the role of exercise-induced suppression of CSD in disease models.

Exercise effects revealed by BOLD-fMRI

Electrical stimulation in the rat forepaw induced BOLD activation in the S1, which is the brain region associated with sensory-discriminative aspects of pain.49 The BOLD-fMRI signal originates from neurovascular coupling and indirectly reflects neural activity. In the aging process, the senescent deterioration of blood vessels, glia, and neurons influences the neurovascular relationship that alters the BOLD signal.50 Previous studies have observed a compensatory effect in the hemodynamic signal with increasing spatial extents of oxyhemoglobin concentrations in the aging brain, which might be associated with vessel compliance.51 Physical training affects cognition via improvements in cardiovascular fitness, whereas motor training directly affects cognition. Exercise improves vascular function in both health and disease. Another study using a 5-week exercise program in a rat model revealed that exercise led to sprouting angiogenesis and increased capillary diameter.52 Therefore, these studies supported our findings that the exercise intervention enhanced blood circulation efficiency in task engagement with lower signal changes in the EXE group (Figure 9).

Effects of treadmill exercise on cellular protein levels

The hippocampus shrinks in the later stages of adulthood, leading to impaired memory and an increased risk of dementia. There have been studies in which the size of the hippocampus of elderly people who exercised increased by 2, thereby improving spatial memory.53 Exercise stimulates cardiovascular growth in the cortex, cerebellum, striatum, and hippocampus to meet nutritional needs.54 The growth of the new vascular system may depend on the presence of molecules such as VEGF and IGF1. The literature points out that IGF1 may induce the formation of new blood vessels by regulating VEGF, a growth factor54 that is mainly involved in the formation and development of blood vessels. Our western blot results showed that VEGF was significantly higher in the EXE group than in the SED group (p < 0.05) (Figure 10). In addition to IGF1 and VEGF, BDNF is another molecule that has been consistently shown to be upregulated by exercise therapy. BDNF has been shown to be related to LTP, a neural analog of long-term memory formation, and necessary for the new growth and survival of neurons. Blocking the binding of BDNF to TrkB eliminates LTP and neurogenesis. Our data showed that the EXE group also had significantly higher BDNF expression in the hippocampal gyrus than the SED group (p < 0.05) (Figure 10). The increase in BDNF levels after exercise therapy may be an important finding because serum and cortical concentrations of BDNF are reduced in AD, PD, depression, anorexia, and many other diseases. Aerobic exercise may have neuroprotective effects by regulating the secretion of BDNF to prevent the development of certain cognitive and neurological symptoms associated with these diseases.55 Increased secretion of neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF and VEGF) promotes the proliferation, differentiation, maturation (i.e., NeuN), and survival of neural stem cells in the hippocampus. NeuN was significantly higher in the cortex (p < 0.01) and hippocampal gyrus (p < 0.05) in the EXE group than in the SED group (Figure 10).

Physical exercise exerts an essential effect on brain plasticity and modulates neuron-glia interactions. GFAP is a factor in plasticity, can induce and stabilize synapses, can regulate the concentration of various molecules, and can support neuronal energy metabolism. GFAP provides sufficient metabolic support for neurons by regulating redox potential, neurotransmitter release, and ion concentrations (e.g., K+), regulating the production of nutritional factors (i.e., BDNF), and providing antioxidant defense mechanisms, which play different roles to maintain the best environment for neuron function. Physical exercise promotes significant changes in GFAP levels, and GFAP is involved in regulating neural activity and plasticity.9 Our study found that GFAP significantly increased in the EXE group (p < 0.05) (Figure 10). Our data show that GFAP and NeuN are relevant to CSD because neurovascular coupling is observed during CSD progression, which is controlled by the neurovascular unit. CSD is a side effect due to ionic disturbances in the brain such that increased metabolic demands on neurons lead to further increases in CBF. Therefore, neurovascular coupling must be controlled by glial cells, and GFAP is a marker of astrocytes that has been used to observe the changes in astrocyte function during CSD progression. Repetitive CSDs may damage neurons in the brain, as evidenced by the downregulation of the neuronal marker NeuN.

Aging is accompanied by a decline in memory and other brain functions. Physical exercise can alleviate this decline by adjusting factors involved in crosstalk between skeletal muscle and the brain (such as neurotrophic factors and oxidative stress parameters). Exercise increases mitochondrial PINK1 function and mitochondrial autophagy. PINK1 regulates mitochondrial function, inhibits the synthesis of reactive oxides, and achieves neuroprotective effects. Mitochondrial autophagy degrades damaged mitochondria, which may lead to neurodegenerative diseases if this pathway is compromised. We used normal rats in our experiment. They did not have genetic defects, and no drugs were administered; therefore, the effect of short-term high-intensity exercise on PINK1 was less significant. We evaluated neurodegenerative disease-related proteins to prove the advantages of exercise. One of these pathways involves BDNF enhancing the processing of APP by ADAM10. APP is cleaved by ADAM10 and releases sAPPα, which has a neuroprotective effect, thereby inhibiting BACE1-cleaved APP to release sAPPβ and reducing the production of toxic molecules.56 Our western blot results also showed that BDNF was higher in the EXE group than in the SED group (p < 0.05), there was a trend for higher ADAM10 in the EXE group than in the SED group, the downstream molecule sAPPα was higher in the EXE group than in the SED group (p < 0.01), and sAPPβ showed a trend of being lower in the EXE group (p < 0.01) (Figure 11). These data showed that exercise increased BDNF levels and, when mediated by ADAM10, released sAPPα and inhibited BACE1 from cleaving sAPPβ. Since Aβ is not found in normal rats,57 we will not discuss it in this study.

Interestingly, the BACE1 protein levels in our rats did not decrease as we expected, and the levels in the EXE group were higher than those in the SED group (p < 0.05) (Figure 11). In addition to its role in the disease process, BACE1 also participates in other cell functions. It is not only expressed by neurons but also expressed by other cell types (such as Schwann cells). Schwann cells are the main cells that make up peripheral nerve cells, which can be regulated by movement, and these interactions with movement are related to SSEP58; here, the SSEP amplitudes in the EXE group were smaller (P1 amplitude: 557.96, N1 amplitude: −732.37), and those in the SED group were larger (P1 amplitude: 2107.93, N1 amplitude: −1437.37).

Effects of treadmill exercise on behavioral function

Physical activity generated through exercise is beneficial to brain function and affects cognitive function (attention or memory) and performance. Cognitive functioning refers to the process that enables a person to process tasks, reason, and solve problems. A number of tests have been used to assess cognitive function. Passive avoidance learning and significantly facilitated active avoidance learning have been used to observe improvement in memory function. The Morris water maze is used to assess details related to learning and memory styles, learning needs, basic abilities such as full vision and motor skills (swimming), basic strategies (learning to swim from walls and learning to climb platforms), and similar motivation (escape from water) as the program. Human studies have shown that physical activity affects cognition in children and youth: at this stage of the life cycle, there is little room for improvement in cognitive function related to exercise, but there is a greater impact on health; regarding the cognitive impact after adulthood, physical activity has a positive effect on cognition. Regarding normal adults and patients with early symptoms of AD (among which memory or cognitive abilities are slightly impaired), there is a significant relationship between physical exercise training and cognitive improvement.59 Exercise-mediated results are different during development and aging because the brains of children are still developing and organizing, while the brains of adults are not. However, physical activity in childhood may promote optimal cortical development and promote lasting changes in brain structure and function. Another study has shown that physical exercise prevents the development of cognitive impairment, AD, and other types of dementia and that the incidence of these problems in the highest activity group was reduced by 60%.60 Human studies have shown that physical activity in children and the elderly can improve cognitive abilities. However, the extent to which neuroimaging techniques can be used to examine the human brain clearly has limitations. Therefore, nonhuman animal research is essential. Nonhuman animal research can directly examine the cellular and molecular reactions triggered by exercise, while in humans, it can only be indirectly measured and inferred. Exercise can enhance learning abilities and improve memory. In rodents, the proliferation and survival rate of cells in the hippocampus were shown to increase,61 and these new cells may help learning and memory. Degeneration in the hippocampus can cause memory impairments in later adulthood.62 Among neurodegenerative diseases, AD is characterized by a significant decrease in the number of neurons in the hippocampus, which may be alleviated by exercise-induced neurogenesis. It has been pointed out in the literature that long-term voluntary exercise by AD model rats can reduce Aβ levels in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus and improve learning efficiency55 in the Morris water maze. Physical exercise may have a strong overall enhancing effect on learning.

Overall benefits of exercise for the brain

Physical exercise slows cognitive aging and neurodegeneration in humans and animals.63 Exercise affects the brain in many ways (Figure 12): 1) increasing the size of the hippocampus, 2) reducing stress hormones that suppress brain activity, 3) improving sleep quality, and 4) stimulating the release of growth factors. Regular exercise slows brain aging; both aerobic and anaerobic exercise can maintain a healthy brain; exercise can improve the concentration, executive function, and memory of people with mild cognitive impairment; and weight-bearing exercise was shown to be more effective in improving overall cognitive ability than physical and mental exercises.53 Exercise can improve cognitive function in elderly individuals, stroke survivors, patients with PD, and patients with AD.64 In addition, some literature shows that male and female individuals, due to the gender/sex differences in physiology, hormones, and metabolism, may exhibit differences in neurovascular and behavioral performance. Previous studies have suggested that sex-related differences in physical and metabolic parameters are manifested when men and women have increased energy demands during exercise (adrenaline levels during exercise or estrogen levels during menstrual cycles). Women have a lower cardiac output and hemoglobin oxygen-binding capacity, and women use more lipids for energy as fuel than men. Potential reasons for sex differences in exercise responses are that men metabolize more protein and glycogen during exercise and have different body sizes, body compositions, and muscle characteristics. Men have greater skeletal muscle mass, and women have more body fat. Men also have an overall increase in left ventricular end-diastolic volume during exercise compared with women. Different levels of exercise also exert different effects on men and women. Switching from sedentary behavior to low-level exercise provides significant health benefits for both sexes, while health benefits are greater for men than women when the intensity is increased to vigorous levels.65,66 In the future, we will also take gender into consideration in our experiments and discuss this topic in greater depth.

Figure 12.

Summary of exercise effects on the brain’s message-transmitting molecules

Exercise can provide the brain with blood and nutrients, increase neurotrophic factors (BDNF), neurotransmitters, number of neural stem cells (NeuN, GFAP), and cerebrovascular plasticity (VEGF), affect neuron-glia interactions, and regulate various molecules. Ion homeostasis has a protective effect on the brain and slows cognitive degradation caused by neurodegenerative diseases and aging. BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; NeuN: neuronal nuclei; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; ADAM10: a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10; BACE1: beta-secretase 1; sAPPα, soluble amyloid precursor protein.

Exercise exerts protective effects on the brain; the more an individual exercises, the larger the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex become. Brain imaging studies have found that exercise habits are closely related to brain structure and volume, and our fMRI results also revealed significant differences (Figure 9). Exercise increases the flow of blood and oxygen in the body, increases blood circulation in the brain, increases BDNF, stimulates neuron growth, increases nerve conduction, and strengthens the connections between nerve cells, all of which are beneficial for the brain.67 The literature points out that a single bout of exercise can temporarily improve physical and mental states, and long-term, regular exercise can improve the brain, cardiopulmonary function, and muscle abilities. Our results are consistent with the literature and show that exercising for four weeks (for 30 min per day) increased the number of neurons and BDNF in the rat brain (Figure 10C). Our overall data indicate that converging evidence at the molecular, cellular, behavioral, and systems levels shows that physical activity is beneficial to cognition (Figure 12).

Different types and timing of exercise also affect different brain regions. Activity in the prefrontal cortex is regulated by physical and cognitive loads, and cerebral blood flow and oxygenation are increased during low- to moderate-intensity exercise, which may facilitate nutrient distribution throughout the brain. Exercise increases BDNF levels in the hippocampus, the memory center of the brain, and regular exercise increases the number and branches of blood vessels in the hippocampus, which together improve blood flow to the brain. The hippocampus is also the only specific area of the brain that produces new nerve cells; the other area is the subventricular region. When the hippocampus has a complete blood supply, the brain will produce more BDNF to help nerve cells grow and survive. An increase in the number of neurons and synaptic connections may increase the distance of intercellular communication, thereby affecting ECoG and CSD parameters. The results of the ECoG-LSCI system showed a lower cerebral blood flow signal in response to intravascular CSD. One possible explanation is that the numbers of neurons and synaptic connections in the brain increase after exercise intervention, resulting in longer blood flow travel distance and slower CSD. In the electrophysiological experiment, we used the same electrical stimulation parameters (4 mA) and found a significant reduction in neurophysiological intensity as an effect of the exercise intervention. As exercise increases nerve conduction frequency, electrophysiological intensity decreases, and CSD velocity decreases as well. We used the ECoG-LSCI system to simultaneously observe intracerebral electrophysiological and blood flow-related changes, a novel CSD marker, to reinterpret the brain’s neurovascular response.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we used ECoG-LSCI, electrical stimulation, and KCl-induced CSD to assess the effects of exercise on brain function. Since these methods require exposing the brain surface, they can only be used to observe neuronal function in a limited area of the brain. However, neurodegenerative diseases may occur in other areas of the brain, and we have not determined whether we can apply our results for the effect of exercise on neural function to different brain areas. Our western blotting results suggest that exercise exerts different effects on protein levels in different brain areas. Although MRI and western blotting have been used to assess neural function in deeper areas of the brain, they are unable to provide simultaneous measurements of neurovascular coupling, which can be performed using ECoG-LSCI.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-BDNF | Abcam | Cat# ab108319; RRID:AB_10862052 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-GFAP | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-6170; RRID:AB_641021 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-NeuN | Abcam | Cat# ab177487; RRID:AB_2532109 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-PINK1 | Abcam | Cat# ab23707; RRID:AB_447627 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGFA | Elabscience | Cat# E-AB-64001; RRID:N/A |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ADAM10 | Abcam | Cat# ab124695; RRID:AB_10972023 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-BACE1 | Abcam | Cat# ab183612; RRID:N/A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-sAPPα 2B3 | IBL | Cat# JP11088; RRID:AB_1630819 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-sAPPβ | IBL | Cat# JP18957; RRID:AB_1630824 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-actin | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-47778; RRID:AB_626632 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG - H&L Polyclonal antibody, Hrp Conjugated | Abcam | Cat# ab6721; RRID:AB_955447 |

| Goat polyclonal Secondary Antibody to Mouse IgG - H&L | Abcam | Cat# ab6789; RRID:AB_955439 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| RIPA buffer | Visual Protein | Cat# RP05-100 |

| Protease inhibitor | Roche | Cat# 04693132001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| BCA protein assay kit | ThermoFisher | Cat# 23225, 23227 |

| Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate | Millipore | WBKLS0500 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Rat: Sprague–Dawley | LASCO | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | ImageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html |

| GraphPad Prism v.8.0.1 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism |

| SPM 12 | www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Lun-De Liao (ldliao@nhri.edu.tw).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

High-intensity interval training (HIIT)

All procedures were performed in accordance with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the National Health Research Institute (NHRI), Taiwan (approved protocol number: NHRI-IACUC-109134-A). A total of 24 male adult Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (LASCO, Taipei, Taiwan) (N = 12 for ECoG-LSCI/western blot tests, N = 12 for MRI tests), weighing from 280 to 450 g, were allocated to two groups, i.e., SED or EXE groups, with N = 6 in each group. All animals were housed in a 12-h dark/light cycle environment at a constant temperature and humidity with free access to food and water.

The animals in the EXE group exercised on a treadmill made for animal use (LE8706TS, Letica Scientific Instruments, Barcelona, Spain) once daily, five days per week for 4 consecutive weeks. During the 4 weeks, the animals were subjected to the treadmill for 30 min/day. During acclimation, the treadmill running velocity was 30 cm/s (3 days). After acclimation, the treadmill running velocity was 35 cm/s (weeks 1 and 2) and 40 cm/s (weeks 3 and 4).2 Each day, the training program included exercise for 15 min, rest for 10 min, and exercise for 15 min (Figure 2A). In rare cases, animals were excluded from this study if they refused to run. The SED rats did not receive any exercise training and spent the entire time in their home cages.

Method details

Electrocorticography-laser speckle contrast imaging (ECoG-LSCI) system

We integrated ECoG recording and fine-resolution LSCI (ECoG–LSCI) to simultaneously measure rCBF and neuronal activity, as shown in Figure 1. rCBF was assessed using LSCI. A laser module (660 nm; 100 mW; RM-CW04-100, Unice E-O Service Inc., Taoyuan, Taiwan) was used to illuminate the region of interest (ROI). The laser beam was expanded with a Plano-convex lens ( = 75 mm; LA1608-A, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) to a size of approximately 40 × 30 mm to provide proper illumination to the exposed area of the cortex. The illuminated area was imaged using a 16-bit charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (pixel size: 4.65 × 4.65 μm; DR2-08S2M/C-EX-CS, Point Gray Research Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) via an adjustable magnification lens (0.3–1×; ∕ 4.5 max) with a 2× extender. A linear polarizer was placed before the CCD image collection lens, and the working distance was approximately 5 cm to eliminate scattering. Laser speckle images (1032 × 776 pixels) were acquired at 25 fps (exposure time T = 10 ms).

The LSCI system was controlled using a custom LabVIEW program (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA), while the analysis was implemented using MATLAB (MATLAB R2018a, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). A graphics processing unit (GPU) was also introduced into our LSCI data processing framework to achieve real-time, high-resolution blood flow visualization on the PC. This method is a parallel computing platform and programming model invented by NVIDIA (Santa Clara, CA, USA). It allows for dramatic increases in computing performance by harnessing the power of the GPU (GeForce GTX 650 Ti, NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

SSEPs were simultaneously measured using a multichannel data acquisition system (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA). The ECoG signals were recorded through a head-stage amplifier (gain of 2) and filtered by a bandpass filter from 0.5 Hz to 7,500 Hz. The signals were then digitized at a sampling rate of 1 kHz and sent through a 100-Hz lowpass filter.

Animal preparation and surgery

Craniotomy was performed on the rats to create a window for ECoG-LSCI. The rats were given 2% isoflurane (Panion & BF Biotech Inc., Taoyuan, Taiwan) in oxygen for anesthesia. Using the bregma as a landmark, a window was created that covered anterior-posterior (AP) ±3.0 mm and medial-lateral (ML) ±3.5 mm using a surgical drill. For ECoG recording, two epidural electrodes were placed at the forelimb region of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1FL) (AP = +1.0 mm, ML = +4 mm), and a reference electrode was placed at ML = +4 mm posterior to the lambda (Figure 1). After surgery, the rats were switched from isoflurane to dexmedetomidine (Zoetis, Taiwan) sedation for monitoring of electrical stimulation and KCl-induced CSD. An initial bolus of dexmedetomidine was given subcutaneously at 0.025 mg/kg while still under 1.5% isoflurane anesthesia. Over a 15-min interval, the isoflurane dosage was gradually decreased to 0%. Using an infusion pump, a maintenance dosage of 0.05 mg/kg/h dexmedetomidine was injected continuously at the end of the 15-min interval. The surgeons were professionally trained to ensure the survival of all rats during surgery. Therefore, in this study, from the craniotomy to the completion of the experiment, the mortality rate of the rats was approximately 2%.

Peripheral electrical stimulation

For the electrical stimulation procedure, two stainless steel acupuncture needles were inserted into the left forelimb, one in the palm and the other in the proximal forelimb muscle. The limb was stimulated by applying rectangular pulse trains of a 0.2-millisecond width at 3 Hz supplied using a DS3 isolated current stimulator (Digitimer Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, Herforshire, UK). The maximum current amplitude was 4 mA. The single-session stimulation paradigm consisted of three blocks. Each block included 30 s of stimulation, which contained 90 stimulation pulses and was bordered by 30-s rest periods (Figure 2).

KCl-induced CSD

The KCl-induced CSD experimental protocol (Figure 2B) was performed after SSEP measurements. To calculate CSD speed, two points 3 mm apart were marked for scale next to the imaging window using a stereotaxic system. During the craniotomy, a hole was drilled at the bottom right to add KCl for CSD induction (Figure 2C). Before adding KCl, the LSCI and ECoG signals were recorded for 5 min as the baseline. Another 40 min were subsequently recorded after the addition of KCl. The number of CSD events, the times of CSD occurrence, and the CSD speed were obtained from the LSCI images. MATLAB was used to calculate the rCBF over time in a circular ROI. This graph was used to obtain the number of CSD events and the time of CSD occurrences. The CSD threshold was based on the first peak that appeared in 5 min. To calculate the speed of CSD, two regions of interest were compared, and the distance between the ROIs was divided by the time difference between peaks in the two ROIs (X mm/Δt min). MATLAB calculated the speed between the two points of the CSD based on the difference between the two points, the time difference between the two ROIs of the CSD, and the time difference between the peak of the cortical light spot. The CSD propagation direction moved from the KCl hole (the arrow indicates the direction of the wave peak, from ROI1 black line t1 to ROI2 blue line t2). When the craniotomy occurred, P1 (X, Y) and P2 (X, Y), which were 3 mm apart, were marked on the left side of the skull. According to the coordinate formula , the distance C between the two points was defined and then the two specific ROIs in the image were identified (circled by the CSD peak direction) to obtain the distance Z. Then, the actual distance between the two ROIs X (mm) was calculated (C:3 = Z:X), and this distance was divided by the time difference to obtain the CSD speed (mm/s), which was finally converted to speed in mm/min.

Data analysis for LSCI

A normalized ratio of rCBF (rCBFN) was calculated using the following equation to quantify the changes in rCBF at different time points of CSD in the cortical region:

| (Equation 1) |

where is the baseline corresponding to the mean value of resting rCBF fluctuations before CSD, and is the mean value of resting rCBF fluctuations at the time window in the SED and EXE groups.

The linear correlation of resting rCBF fluctuations in the cortical regions at each frequency was evaluated using the following magnitude-squared coherence function:

| (Equation 2) |

where A and M represent speckle flow index signals of the anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery in the cortex, respectively, and represents the cross power spectral density of the cortex. and represent the power spectral densities of the cortex. Note that the power spectral density was estimated by Welch’s overlapped averaged periodogram method.

In this study, the two rCBF signals were coherent at the frequency band between 0.05 and 0.15 Hz, where the coherence values were larger than 0.5.68 Therefore, the phase of at frequencies between 0.05 and 0.15 Hz was used to indicate the relative lag between the coherent components, which was calculated to describe the temporal relationship of rCBF between the cortical regions and is defined as follows:

| (Equation 3) |

where a positive phase difference () indicates the cortex as the blood in the cortical region is perfused through that cortical region, while a negative indicates that the cortex lags the cortical region as the blood is perfused through another cortical region.69 Then, the time difference can be calculated by the following equation:

| (Equation 4) |

Data analysis of ECoG recordings

The SSEPs induced by forepaw electrical stimulation were recorded and analyzed offline using MATLAB. The SSEP amplitudes of individual sweeps were averaged over 90 sweeps to generate an averaged SSEP over a 0.2-ms period after the stimulus pulse. Afterward, the averaged SSEP was subdivided into the two most commonly observed SSEP components: P1 (the first maximum voltage after stimulation) and N1 (the minimum voltage). The changes in SSEP components, including the amplitude and peak latency, were used to evaluate the variations in the evoked responses induced by forepaw stimuli in SED and EXE animals.

fMRI data acquisition and imaging

The MRI experiment was conducted using a 7-Tesla scanner (Bruker Biospec 7030 USR, Ettlingen, Germany) with a linear volume coil for radio frequency (RF) pulse transmission and a receiving four-element phased-array coil. Images were acquired using T2-weighted rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence to localize the head position (10 slices, thickness = 1 mm, repetition time (TR) = 2500 ms, echo time (TE) = 11 ms, matrix size = 128 × 128, field of view (FOV) = 25 × 25 mm, and average = 1) and a single-shot gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence for the fMRI session with electrical stimulation. The imaging parameters for the fMRI scans are shown in Figures 3A and 3B. A real-time pressure sensor was placed below the abdomen of the rats to monitor respiration rate (30–50 breaths/min), and a circulating hot water bed was used to maintain body temperature.

Rats were initially anesthetized with 3% isoflurane in oxygen for 7 min followed by an intramuscular injection of dexmedetomidine (0.5 mL; 0.025 mg/kg; Dexdormitor, Orion, Espoo, Finland) mixed in 1:4 ratios with the saline solution into the inner thigh of the hindlimb. The isoflurane concentration was adjusted according to the respiration rate during shimming and spatial localization. Afterward, the isoflurane supply was turned off, and an fMRI session with electrical stimulation was conducted after 10 min. The total waiting time for dexmedetomidine action was approximately 35 min (Figure 3A).

Regarding the electrical stimulation, stainless steel electrodes stimulated the left forepaw of the rats with constant current pulses, and monophasic square-wave electrical stimulation was produced from an isolated stimulator (S48 Square Pulse Stimulator with Stimulus Isolation Unit, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, USA).70 As shown in Figure 3C, the block design of electrical stimulation included a 20-s dummy scan and 20-s additional baseline periods, followed by five electrical stimulation blocks. Each block contained 20 s for both on and off times, and the electrical stimulation parameters were 4 mA and 12 Hz during the on-time.

Protein extraction

After completion of the KCl-induced CSD protocol, the animals were sacrificed. The brain was removed and placed on ice, and the two hemispheres were separated. The hippocampus and cortex were dissected from each hemisphere and stored at −80°C.71 For protein extraction, hippocampal and cortical tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer (Visual Protein, Taiwan) with protease-inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, Germany). The homogenates were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C.72 Protein concentrations in the supernatant were measured using a protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) and then samples were stored at −80°C.

Western blotting analysis

Samples were thawed on ice and then denatured in sample buffer (0.0625 M Tris, 2% [v/v] glycerol, 5% [w/v] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.001% [w/v] bromophenol blue, pH 6.8) at 95 °C for 10 min. Samples (20 μg) were separated through gel electrophoresis using a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel at 60 V for 3 h and were then transferred onto PVDF membranes via wet transfer (30 V at 4 °C overnight).

Membranes were blocked using 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. All primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer. The primary antibodies included anti-BDNF (Abcam; RRID: AB_10862052), anti-GFAP (Santa Cruz; RRID: AB_641021), anti-NeuN (Abcam; RRID: AB_2532109), anti-PINK1 (Abcam; RRID: AB_447627), anti-VEGFA (Elabscience; E-AB-64001), anti-ADAM10 (Abcam; RRID: AB_10972023), anti-BACE1 (Abcam; ab183612), anti-sAPPα 2B3 (IBL; RRID: AB_1630819), anti-sAPPβ (IBL; RRID: AB_1630824) and anti-actin (Santa Cruz; RRID: AB_626632) for a 1-h incubation. Membranes were incubated for 2 h with the peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit (Abcam; RRID: AB_955447) or anti-mouse (Abcam; RRID: AB_955439) IgG antibodies and then immunoblotted using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore).

Statistical analysis

For the analysis of the SSEP and CSD data, column analyses of the experimental design parameters were performed using unpaired t-tests. For analyses of western blot data, grouped analyses with multiple t-tests (one per row) were performed. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The significance level was set to p < 0.05.

SPM 12 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) was used to process fMRI images using the following sequence: (1) motion correction, (2) smoothing, and (3) normalization. The activation maps for electrical stimulation were calculated using a general linear model (GLM). For the group analysis, we conducted one-sample t-test to generate the group-level activation maps of the EXE and SED groups, as shown in Figures 9A and 9B, respectively. Next, the time series from the activated regions were quantified as percent change in the signal and then averaged across subjects in each group,73 as shown in Figure 9C. The percent change in the signal was compared between the EXE and SED groups using a two-sample t-test, with a significance level of p < 0.01.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under grant numbers 110-2221-E-400-003-MY3 and 110-2314-B-075-085 and the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan under grant numbers NHRI-EX108-10829EI, NHRI-EX111-11111EI, and NHRI-EX111-11129EI.

Author contributions

S.Y.Y., C.W.W., and L.D.L. conceived the project and designed the experiments. S.Y.Y., H.Y.W., and Y.W. performed the experiments. S.Y.Y., H.Y.W., and L.D.L. analyzed the data. S.Y.Y., H.Y.W., Y.W., C.M.H., C.W.W., J.H.C., and L.D.L. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Published: March 9, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106354.

Data and code availability

-

•

Original western blot images reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

All original code will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

Any addition information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact Lun-De Liao (ldliao@nhri.edu.tw) upon request.

References

- 1.Carek P.J., Laibstain S.E., Carek S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011;41:15–28. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lan Y., Huang Z., Jiang Y., Zhou X., Zhang J., Zhang D., Wang B., Hou G. Strength exercise weakens aerobic exercise-induced cognitive improvements in rats. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0205562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillen J.B., Gibala M.J. Is high-intensity interval training a time-efficient exercise strategy to improve health and fitness? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39:409–412. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voss M.W., Soto C., Yoo S., Sodoma M., Vivar C., van Praag H. Exercise and hippocampal memory systems. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019;23:318–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaynman S., Ying Z., Gomez-Pinilla F. Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:2580–2590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P.Z., Nusslock R. Exercise-mediated neurogenesis in the Hippocampus via BDNF. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:52. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Q., Ying Z., Gómez-Pinilla F. Exercise influences hippocampal plasticity by modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor processing. Neuroscience. 2011;192:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer J., Zhao X., van Praag H., Wodtke K., Gage F.H., Christie B.R. Effects of voluntary exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo. Neuroscience. 2004;124:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saur L., Baptista P.P.A., de Senna P.N., Paim M.F., do Nascimento P., Ilha J., Bagatini P.B., Achaval M., Xavier L.L. Physical exercise increases GFAP expression and induces morphological changes in hippocampal astrocytes. Brain Struct. Funct. 2014;219:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillman C.H., Erickson K.I., Kramer A.F. Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:58–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bravo-San Pedro J.M., Kroemer G., Galluzzi L. Autophagy and mitophagy in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2017;120:1812–1824. doi: 10.1161/Circresaha.117.311082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao N., Xia J., Xu B. Physical exercise may exert its therapeutic influence on Alzheimer's disease through the reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction via SIRT1-FOXO1/3-PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy. J. Sport Health Sci. 2021;10:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firth J., Stubbs B., Vancampfort D., Schuch F., Lagopoulos J., Rosenbaum S., Ward P.B. Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2018;166:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao F.L., Zhang L., Zhang Y., Zhou C.N., Jiang L., Xiao Q., Luo Y.M., Lv F.L., He Q., Tang Y. Running exercise protects against myelin breakdown in the absence of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of AD mice. Brain Res. 2018;1684:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iadecola C. The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron. 2017;96:17–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sloan H.L., Austin V.C., Blamire A.M., Schnupp J.W.H., Lowe A.S., Allers K.A., Matthews P.M., Sibson N.R. Regional differences in neurovascular coupling in rat brain as determined by fMRI and electrophysiology. Neuroimage. 2010;53:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Tye A.E., Zhao J., Ma D., Raddant A.C., Bu F., Spector B.L., Winslow N.K., Wang M., Russo A.F. Induction of calcitonin gene-related peptide expression in rats by cortical spreading depression. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:333–341. doi: 10.1177/0333102416678388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leao A.A.P. A.A.P. Cc/Life Sci; 1992. Remarkable Reaction of the Brain Gray-Matter - a Citation-Classic Commentary on Spreading Depression of Activity in the Cerebral-Cortex by Leao; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan X.Q., Smith T.L., Prough D.S., Dewitt D.S., Dusseau J.W., Lynch C.D., Fulton J.M., Hutchins P.M. Long-term effects of nimodipine on pial microvasculature and systemic circulation in conscious rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:H1395–H1401. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.5.H1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui Y., Toyoda H., Sako T., Onoe K., Hayashinaka E., Wada Y., Yokoyama C., Onoe H., Kataoka Y., Watanabe Y. A voxel-based analysis of brain activity in high-order trigeminal pathway in the rat induced by cortical spreading depression. Neuroimage. 2015;108:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seghatoleslam M., Ghadiri M.K., Ghaffarian N., Speckmann E.-J., Gorji A. Cortical spreading depression modulates the caudate nucleus activity. Neuroscience. 2014;267:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancio L.C. Building on the legacy of Dr. Basil A. Pruitt, Jr., at the US Army Institute of Surgical Research during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:755–760. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu X., Chen M., Lu J., Li P. Cortical spreading depression induces propagating activation of the thalamus ventral posteromedial nucleus in awake mice. J. Headache Pain. 2022;23:15. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartings J.A., Watanabe T., Bullock M.R., Okonkwo D.O., Fabricius M., Woitzik J., Dreier J.P., Puccio A., Shutter L.A., Pahl C., et al. Spreading depolarizations have prolonged direct current shifts and are associated with poor outcome in brain trauma. Brain. 2011;134:1529–1540. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takano K., Latour L.L., Formato J.E., Carano R.A., Helmer K.G., Hasegawa Y., Sotak C.H., Fisher M. The role of spreading depression in focal ischemia evaluated by diffusion mapping. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:308–318. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro H.M.C., de Lima e Silva D., de França J.P.B.D., Maia L.M.S.d.S., Angelim M.K.C., dos Santos A.A., Guedes R.C.A. Differential effects of physical exercise and L-arginine on cortical spreading depression in developing rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2011;14:112–118. doi: 10.1179/1476830511Y.0000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathew A.A., Panonnummal R. Cortical spreading depression: culprits and mechanisms. Exp. Brain Res. 2022;240:733–749. doi: 10.1007/s00221-022-06307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shabir O., Pendry B., Lee L., Eyre B., Sharp P.S., Rebollar M.A., Drew D., Howarth C., Heath P.R., Wharton S.B., et al. Assessment of neurovascular coupling and cortical spreading depression in mixed mouse models of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Elife. 2022;11:e68242. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armitage G.A., Todd K.G., Shuaib A., Winship I.R. Laser speckle contrast imaging of collateral blood flow during acute ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1432–1436. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Culver J.P., Durduran T., Furuya D., Cheung C., Greenberg J.H., Yodh A.G. Diffuse optical tomography of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation, and metabolism in rat during focal ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:911–924. doi: 10.1097/01.Wcb.0000076703.71231.Bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakatani K., Iizuka H., Young W. Somatosensory evoked-potentials in rat cerebral-cortex before and after middle cerebral-artery occlusion. Stroke. 1990;21:124–132. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.21.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mu Y., Gage F.H. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and its role in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2011;6:85–89. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng W., Aimone J.B., Gage F.H. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:339–350. doi: 10.1038/nrn2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Wang C., Pei G. alpha-secretase ADAM10 physically interacts with beta-secretase BACE1 in neurons and regulates CHL1 proteolysis. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018;10:411–422. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjy001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi S.H., Bylykbashi E., Chatila Z.K., Lee S.W., Pulli B., Clemenson G.D., Kim E., Rompala A., Oram M.K., Asselin C., et al. Combined adult neurogenesis and BDNF mimic exercise effects on cognition in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Science. 2018;361:eaan8821. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arida R.M., de Jesus Vieira A., Cavalheiro E.A. Effect of physical exercise on kindling development. Epilepsy Res. 1998;30:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauritzen M., Dreier J.P., Fabricius M., Hartings J.A., Graf R., Strong A.J. Clinical relevance of cortical spreading depression in neurological disorders: migraine, malignant stroke, subarachnoid and intracranial hemorrhage, and traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:17–35. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabricius M., Fuhr S., Bhatia R., Boutelle M., Hashemi P., Strong A.J., Lauritzen M. Cortical spreading depression and peri-infarct depolarization in acutely injured human cerebral cortex. Brain. 2006;129:778–790. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feuerstein D., Manning A., Hashemi P., Bhatia R., Fabricius M., Tolias C., Pahl C., Ervine M., Strong A.J., Boutelle M.G. Dynamic metabolic response to multiple spreading depolarizations in patients with acute brain injury: an online microdialysis study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1343–1355. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogatsky G.G., Sonn J., Kamenir Y., Zarchin N., Mayevsky A. Relationship between intracranial pressure and cortical spreading depression following fluid percussion brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1315–1325. doi: 10.1089/089771503322686111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mies G., Iijima T., Hossmann K.A. Correlation between peri-infarct DC shifts and ischaemic neuronal damage in rat. Neuroreport. 1993;4:709–711. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199306000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dijkhuizen R.M., Beekwilder J.P., van der Worp H.B., Berkelbach van der Sprenkel J.W., Tulleken K.A., Nicolay K. Correlation between tissue depolarizations and damage in focal ischemic rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;840:194–205. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayata C., Jin H., Kudo C., Dalkara T., Moskowitz M.A. Suppression of cortical spreading depression in migraine prophylaxis. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:652–661. doi: 10.1002/ana.20778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aurora S.K., Barrodale P., Chronicle E.P., Mulleners W.M. Cortical inhibition is reduced in chronic and episodic migraine and demonstrates a spectrum of illness. Headache. 2005;45:546–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebetanz D., Fregni F., Monte-Silva K.K., Oliveira M.B., Amâncio-dos-Santos A., Nitsche M.A., Guedes R.C.A. After-effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on cortical spreading depression. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;398:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]