Abstract

The small molecule erastin inhibits the cystine-glutamate antiporter, system xc-, which leads to intracellular cysteine and glutathione depletion. This can cause ferroptosis, which is an oxidative cell death process characterized by uncontrolled lipid peroxidation. Erastin and other ferroptosis inducers have been shown to affect metabolism but the metabolic effects of these drugs have not been systematically studied. To this end, we investigated how erastin impacts global metabolism in cultured cells and compared this metabolic profile to that caused by the ferroptosis inducer RAS-selective lethal 3 or in vivo cysteine deprivation. Common among the metabolic profiles were alterations in nucleotide and central carbon metabolism. Supplementing nucleosides to cysteine-deprived cells rescued cell proliferation in certain contexts, showing that these alterations to nucleotide metabolism can affect cellular fitness. While inhibition of the glutathione peroxidase GPX4 caused a similar metabolic profile as cysteine deprivation, nucleoside treatment did not rescue cell viability or proliferation under RAS-selective lethal 3 treatment, suggesting that these metabolic changes have varying importance in different scenarios of ferroptosis. Together, our study shows how global metabolism is affected during ferroptosis and points to nucleotide metabolism as an important target of cysteine deprivation.

Keywords: Cysteine, nucleotide, ferroptosis, erastin, glutathione, metabolism

Cysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid which is essential for glutathione biosynthesis and redox homeostasis (1, 2, 3). It can be synthesized from methionine through the transsulfuration pathway (4) or imported as its oxidized form cystine via the system xc- amino acid antiporter which exchanges cystine for glutamate (5). It can also enter cells to a certain extent through other amino acid transporters (6, 7). However, many cancer cells cannot meet their requirements for cysteine through the transsulfuration pathway (8) and certain cancers have shown increased reliance on the system xc- transporter (9, 10, 11, 12).

Inhibition of system xc- can lead to ferroptosis, which was described over 10 years ago as an oxidative, iron-dependent form of cell death that was induced by the small molecule erastin (13). Erastin inhibits system xc- and causes cysteine and glutathione depletion (13, 14, 15). Because glutathione is a cofactor for the glutathione peroxidase enzyme GPX4, decreased levels of glutathione can diminish the ability of GPX4 to detoxify potentially destructive lipid peroxide species (16). Ferroptosis is defined as the cell death that occurs when cells are unable to adequately detoxify these species, whether that be due to glutathione depletion or direct loss of GPX4 function. This classical view of ferroptosis has been added to over the years and more recent studies have shown that cysteine depletion can lead to ferroptosis through glutathione-independent mechanisms such as through impaired GPX4 expression (17, 18) and that in some settings glutathione is dispensable for ferroptosis protection due to GPX4’s ability to use other reducing substrates (19).

Additional study of ferroptosis is warranted as it contributes to pathological cell death in numerous disease models including those of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity, Huntington’s disease, periventricular leukomalacia, renal tubular injury and acute renal failure, ischemia/reperfusion injury, and liver damage (13, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Additionally, ferroptosis has shown considerable significance in the context of cancer (27, 28, 29). This is partially due to studies showing many drug-resistant cell types are sensitive to erastin and the GPX4 inhibitor RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3) or that erastin can enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (14, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). There are also data which suggests certain cancers have increased reliance on system xc-9-11, prompting the investigation of whether its blockade could be a selective cancer therapy (36).

Altered metabolism particularly from the mitochondria has been shown to influence ferroptosis providing additional aspects of the process (37) but whether this picture is complete is unknown. To investigate this question, we used our metabolomics platform, which offers a broad coverage of cellular metabolism by measuring over 300 metabolites from more than 40 different metabolic pathways (38, 39) and found that changes in nucleotide metabolism accounted for many of the largest ferroptosis-induced alterations observed. Alterations in central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis and the citric acid cycle were also observed and suggest that defective energy production may lead to altered nucleotide levels.

Results

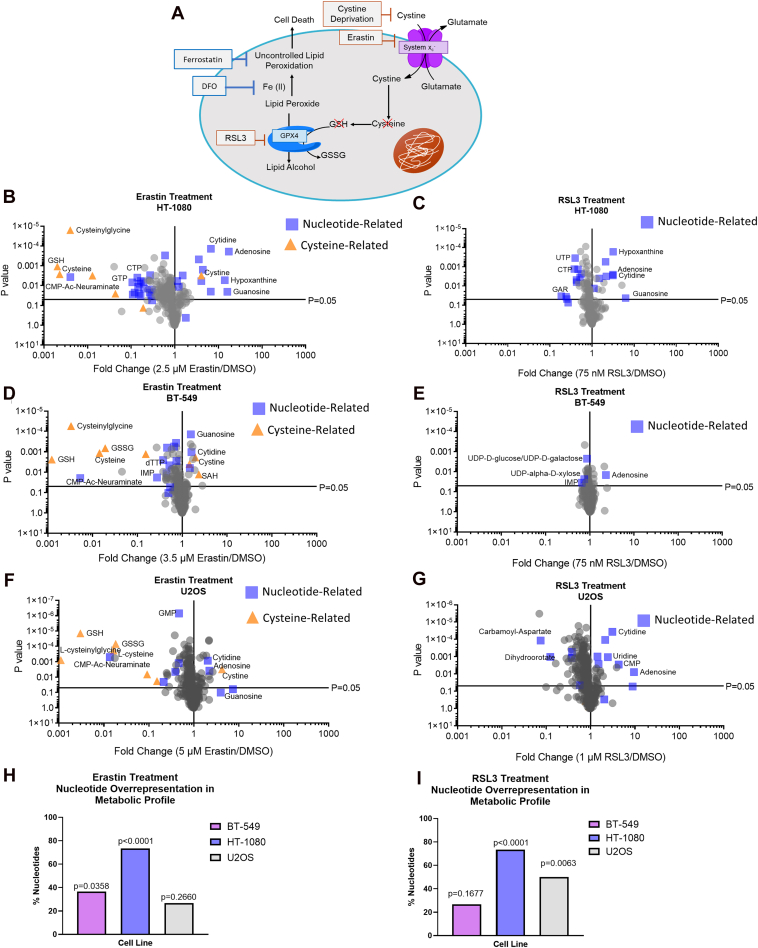

Alterations in nucleotide metabolism are overrepresented in metabolic profile of ferroptosis

To determine how global metabolism is affected when cells are undergoing system xc- or GPX4 inhibition, we treated three different ferroptosis-sensitive cell lines with an IC50 dose of ferroptosis inducers erastin or RSL3 (Fig. 1A) for 15 h (before the onset of cell death) and then extracted polar metabolites for LC-MS based metabolomics and metabolic profiling. As expected, alterations in cysteine-related metabolites were observed in the metabolic profile of erastin-treated cells (Fig. 1, B, D, and F). However, all three cell lines also showed many alterations in the levels of nucleotide-related metabolites including nucleotides, nucleotide precursors and breakdown products, and/or nucleotide-sugars in both erastin and RSL3-treated cells and these were some of the largest metabolic alterations observed (Fig. 1, B–G). To determine whether nucleotide-related metabolites were statistically overrepresented in the metabolic profile of erastin and RSL3-treated cells, metabolites with p < 0.05 on each volcano plot were sorted by the absolute value of the logarithm of the fold-change and the largest 30 were categorized as nucleotide-related or not (this is equivalent to the selecting and sorting the 30 metabolites furthest to the left and the right that are also over the p = 0.05 line on each volcano plot, which is approximately the 10% most-altered metabolites in the metabolic profile). The percentage of these that were classified as nucleotide-related (which includes nucleotides, nucleosides, nucleobases, nucleotide precursors and breakdown products, and nucleotide-sugars/lipids) is shown in Figure 1, H and I. Statistical overrepresentation of nucleotide-related metabolites was determined by comparing this percentage to the percentage of nucleotide-related metabolites that would be expected based on chance. Nucleotide-related metabolites were statistically overrepresented in erastin-treated BT-549 and HT-1080 cells and in RSL3-treated HT-1080 and U2OS cells (Fig. 1, H and I). In erastin-treated U2OS and RSL3-treated BT-549 cells, nucleotide-related metabolites were not statistically overrepresented but nucleotide changes were still observed in the metabolic profile (Fig. 1, E and F). Common nucleotide alterations observed included increased nucleoside levels, decreased levels of nucleotide synthesis intermediates, and decreased nucleotide di- and triphosphate levels (Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1). Many of these alterations were also visible in the metabolic profile after 6 h of drug treatment (Fig. S4).

Figure 1.

Alterations in nucleotide metabolism are overrepresented in metabolic profile of ferroptosis.A, schematic of ferroptosis pathway B–I, results from polar metabolomics shown as volcano plots using p-values generated from multiple unpaired t-tests on log-transformed ion intensity values. H and I, statistical overrepresentation of nucleotides and related metabolites in the metabolic profile was calculated by sorting metabolites with p < 0.05 from each volcano plot by the absolute value of the logarithm of the fold-change and the largest 30 were categorized as nucleotide-related or not. The percentage of these that were classified as nucleotide-related is graphed and the p-value was calculated by a one-sided Fisher’s exact test comparison of this percentage versus the expected number of nucleotide-related metabolites that would be expected based on chance.

To determine whether these alterations could be the result of off-target effects of either drug, we cotreated HT-1080 cells with erastin or RSL3 and ferroptosis inhibitors deferoxamine (DFO), ferrostatin-1 (ferrostatin), or the lipophilic antioxidant Trolox, and assessed what percentage of significantly altered nucleotide-related metabolites were at least partially rescued by each rescue agent. (See figure legend for statistical criteria for partial rescue designation and Tables S2 and S3 for means and p-values for each metabolite. Briefly, a partial rescue meant the rescue agent significantly moved an affected metabolite towards the control level). We found that nearly all nucleotide-related metabolites that were significantly altered by erastin or RSL3 were at least partially rescued by ferrostatin treatment and most of the alterations were also at least partially rescued by DFO or Trolox treatment (Fig. S5A and Tables S2 and S3).

We also assessed whether each rescue agent caused a “full” rescue towards metabolites significantly affected by erastin or RSL3, which meant that the level of the metabolite in the rescue condition was not significantly different than the level of the metabolite in the control condition. We found that ferrostatin fully rescued the majority of RSL3-induced nucleotide alterations (76%) and fully rescued 48% of erastin-induced nucleotide changes, while DFO fully rescued 40 and 43% of RSL3 and erastin-induced nucleotide changes, respectively (Fig. S5B and Tables S2 and S3). DFO was notably less effective than ferrostatin at rescuing nucleotide alterations, however this is unsurprising as DFO has been shown to affect nucleotide metabolism itself (40). The lesser effectiveness of Trolox compared to ferrostatin was also not surprising, as ferrostatin has been shown to more efficiently suppress lipid peroxidation in the context of ferroptosis than Trolox (41). Ferrostatin was also more effective at fully rescuing RSL3-induced nucleotide alterations than erastin-induced nucleotide alterations, which suggests that cysteine deprivation may affect nucleotide metabolism in additional ways to those caused by lipid peroxidation. However together, these data show that most of the observed nucleotide alterations were reversed by validated ferroptosis inhibitors and are unlikely the result of off-target effects of either drug.

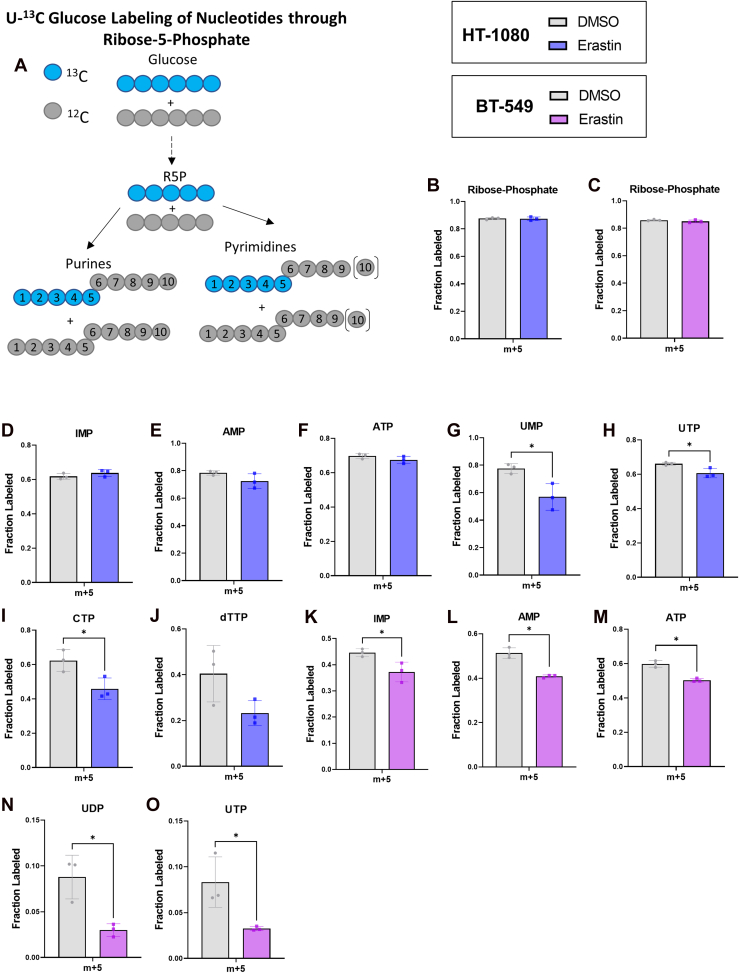

Erastin decreases nucleotide biosynthesis

Decreased nucleotide levels could result from insufficient nucleotide biosynthesis, insufficient energy levels, or both. To better understand how the ferroptosis inducer erastin causes this pattern of nucleotide changes, we performed 13C-glucose tracing in BT-549 and HT-1080 cells treated with erastin and examined how nucleotide biosynthesis and energy producing pathways were affected. Universally labeled 13C glucose (U- 13C glucose) labels purines and pyrimidines through conversion to ribose-5-phosphate (R5P) via the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. 2A). M + 5 R5P showed no differences in fractional labeling between dimethyl sulfoxide- and erastin-treated cells (Fig. 2, B and C), suggesting that pentose phosphate pathway defects are not responsible for any decreased m + 5 nucleotide labeling. In BT-549 cells both purines and pyrimidines showed decreased m + 5 fractional labeling (Fig. 2, K–O). In HT-1080 cells, purines did not show decreased m + 5 fractional labeling at the time point tested (Fig. 2, D–F) but pyrimidines did (Fig. 2, G–J). U-13C glucose can also label purines through conversion to serine, which can potentially produce m+6-9 isotopomers (42). However, these isotopomers are very low abundant and can be difficult to measure. We were able to measure m + 6 inosine monophosphate and ATP in HT-1080 cells and m + 6 ATP in BT-549 cells and found a general trend of decreased m + 6 labeling despite increased serine labeling from glucose (Fig. S6). Together, these results show that erastin disrupts nucleotide biosynthesis, which may partially explain why some nucleotides are depleted in cells treated with erastin.

Figure 2.

Erastin decreases nucleotide biosynthesis.A, Schematic showing U-13C Glucose nucleotide labeling through m+ 5 ribose-5-phosphate. B and D–H,. M + 5 fractional labeling plotted for relevant nucleotides and precursors from HT-1080 cells treated with 2.5 μM erastin. C and K–O, M + 5 fractional labeling plotted for relevant nucleotides and precursors collected from BT-549 cells treated with 3.5 μM erastin. B–O, an unpaired t test was performed to compare dimethyl sulfoxide to erastin for each metabolite. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 for this test, no stars shown indicates p > 0.05.

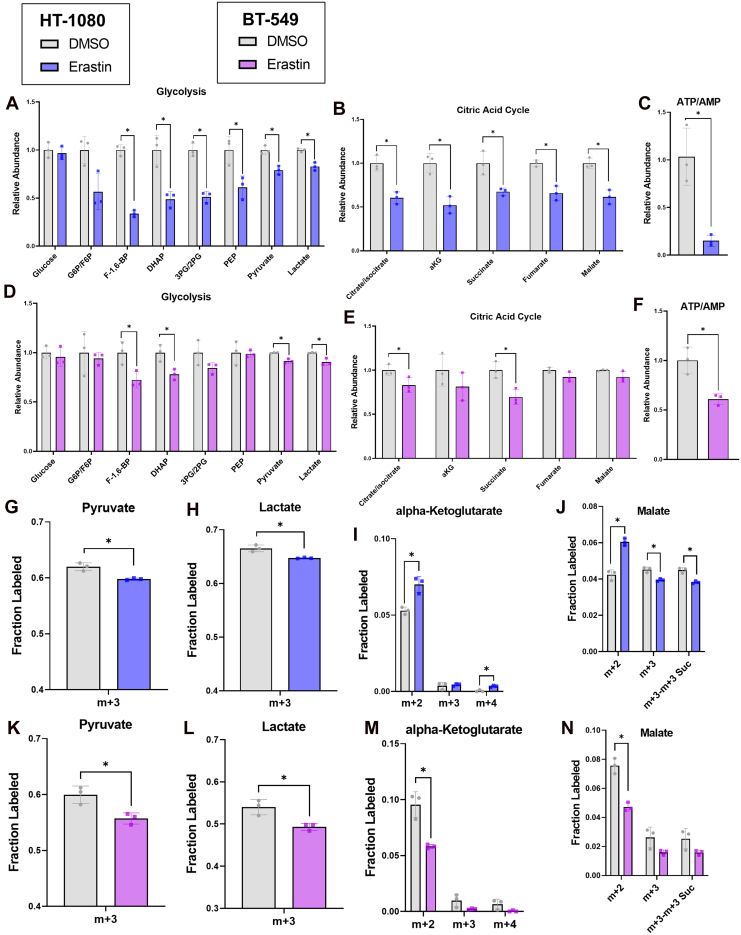

Erastin alters glycolysis and citric acid cycle activity and decreases energy levels

Insufficient energy levels may also explain why high-energy nucleotide di- and triphosphates were the type of nucleotide most often depleted under erastin treatment (Fig. S1, J–O), while low-energy nucleotide monophosphate (Fig. S1, G–I) and nucleoside (Fig. S1, A–C) levels either increased or showed smaller fold-changes than the di- and triphosphates. To determine whether this could be occurring, we first looked at the total levels of metabolites in the energy-producing pathways glycolysis and the citric acid (TCA) cycle. Erastin-treated HT-1080 and BT-549 cells showed significant depletions in many glycolytic intermediates (Fig. 3, A and D) and in TCA intermediates (Fig. 3, B and E). The ratio of ATP/AMP, an indicator of cellular energy status, was also significantly decreased in both cell lines (Fig. 3, C and F). The NADH/NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced/oxidized) ratio, another indicator of energy status was also decreased, although not significantly (Fig. S7, B and F), and increased protein levels of phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (pAMPK) were observed along with increased expression levels of AMPK (Fig. S7J), further suggesting there is an energy depletion under erastin treatment. U-13C glucose tracing (Fig. S7A) showed that pyruvate and lactate had significantly decreased m + 3 fractional labeling under erastin treatment in both cell lines (Fig. 3, G, H, K and L) and a decreased m + 3 pool size (Fig. S7, C, D, G and H), which indicates less glycolytic activity over time.

Figure 3.

Erastin alters glycolysis and citric acid cycle activity and decreases energy levels.A–F, relative levels of metabolites from relevant pathways in HT-1080 cells treated with 2.5 μM erastin or BT-549 cells treated with 3.5 μM erastin. G–N, fractional labeling plotted for relevant isotopomers in glycolysis and TCA in HT-1080 cells treated with 2.5 μM erastin or BT-549 cells treated with 3.5 μM erastin and subjected to U-13C Glucose tracing. J, N m+3-m+3 Suc represents the m + 3 fraction of malate minus the m + 3 fraction of succinate, which represents glucose entry into the TCA via pyruvate carboxylase. A, B and D–E a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed on log-transformed values and followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test if interaction term or main effect of treatment p < 0.05. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 when comparing dimethyl sulfoxide to Erastin treatment in Fisher’s LSD test, no stars shown indicates p > 0.05. C, F, and G–N an unpaired t test was performed to compare dimethyl sulfoxide to erastin treatment. If more than one isotopomer is shown on the graph, a separate uncorrected t test was performed for each. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 for this test, no stars shown indicates p > 0.05.

TCA cycle labeling showed a different pattern in the two different cell lines, with significantly increased 13C glucose-derived m + 2 labeling on the TCA cycle intermediates alpha-ketoglutarate and malate in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells (Fig. 3, I and J) and significantly less in erastin-treated BT-549 cells (Fig. 3, M and N). M + 2 aspartate, which is produced from the TCA cycle, also showed increased m + 2 fractional labeling in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells and decreased m + 2 fractional labeling in erastin-treated BT-549 cells (Fig. S3, E and I). M + 4 alpha-ketoglutarate, which is produced in the second turn of the TCA cycle (Fig. S7A), was also significantly increased in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells (Fig. 3I) and non-significantly decreased in erastin-treated BT-549 cells (Fig. 3M). Before entering the TCA cycle, glucose is converted to pyruvate, which can enter the TCA via two enzymes, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and pyruvate carboxylase (PC) (Fig. S7A). Pyruvate entry into the TCA via PC serves an anaplerotic role and can be distinguished from PDH-derived pyruvate labeling by subtracting the m + 3 fraction of succinate from the m + 3 fraction of malate or aspartate (43, 44). Interestingly, the m + 3 malate fraction minus the m + 3 succinate fraction was decreased in both cell lines treated with erastin, although only significantly in HT-1080 cells (Fig. 3, J and N). The m + 3 aspartate minus the m + 3 succinate fraction was not decreased in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells (Fig. S7E) but the labeling pattern of malate is more reliable to interpret since aspartate labeling is confounded by aspartate in the culture media (44). Together, these results show that erastin-treated HT-1080 cells increase glucose usage into the TCA via PDH, while decreasing anaplerotic glucose entry into the TCA via PC. Erastin-treated BT-549 cells show decreased glucose usage in the TCA cycle through both PDH and PC indicating mitochondrial plasticity.

Exogenous nucleosides rescue diminished cell proliferation under erastin treatment

To understand whether depleted nucleotide levels have a functional significance in erastin-induced cell death and/or growth reduction, we cotreated cells with erastin and a nucleoside cocktail (Fig. 4A) that has previously been used to increase viable cell number in cells with diminished nucleotide production (42). We found that cotreating with exogenous nucleosides caused a small increase in relative viable cell number in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells (Fig. 4B) but a larger nucleoside rescue effect was seen in HT-1080 cells when directly depleting cystine in the media (Fig. 4C). Nucleosides also partially rescued relative viable cell number and restored proliferation in erastin-treated BT-549 cells (Fig. 4, D–F). Because nucleosides increased the number of viable cells 3 days after treatment in erastin-treated cells but not 1 day after treatment (Fig. 4E) the nucleosides likely increase viable cell number by restoring proliferation rather than by inhibiting cell death in erastin-treated cells. Nucleosides did not show any rescue effect in in erastin-treated U2OS cells (Fig. S8G) or in RLS3-treated HT-1080 or BT-549 cells (Fig. S8, H and I), while ferrostatin cotreatment caused a large rescue effect in every cell line tested that was treated with erastin and RSL3 (Fig. S8, A–F). This suggests that the importance of nucleotide-related changes in affecting cellular fitness during ferroptosis is likely secondary to other factors and plays a role in certain circumstances. To understand how nucleosides increase cell proliferation in these circumstances, we measured cysteine, glutathione, and nucleotide levels in BT-549 cells treated with erastin with or without nucleoside cotreatment for 15 h and found that nucleosides do not alter the level of cysteine or glutathione depletion that is caused by erastin (Fig. 4G). Additionally, methionine sulfoxide levels, which are an indicator of oxidative stress (45), were elevated in nucleoside-treated cells, suggesting nucleoside cotreatment does not alleviate oxidative stress (Fig. 4G). Nucleoside cotreatment did significantly increase the levels of certain nucleotides, including guanosine monophosphate, cytidine monophosphate (Fig. 4H), cytidine diphosphate (Fig. 4I), and cytidine triphosphate (Fig. 4J), while others including ADP, uridine diphosphate, ATP, and thymidine triphosphate were unaffected. While the levels of several nucleosides tended to increase when cells are treated with ferroptosis inducers alone (Fig. S1, A–C), this amount of increase is small in comparison to when exogenous nucleosides are supplemented into the media (Fig. S8J), suggesting that the higher nucleoside levels in the erastin only condition are not enough to provide sufficient nucleotide salvage material. These results show that exogenous nucleosides can partially rescue nucleotide levels and cell proliferation which are decreased by erastin in certain cell lines and conditions, suggesting that nucleotide depletion plays a role in the loss of cellular fitness caused by erastin.

Figure 4.

Exogenous nucleosides rescue diminished cell proliferation under erastin treatment.A, identity and concentration of nucleosides in “1× Nucleosides” cocktail. B, relative viable cell number in HT-1080 cells treated ± 2.5 μM erastin and 1× nucleosides for 48 h. C, relative viable cell number in HT-1080 cells cultured in control media or media containing low cystine ± 1× nucleosides for 48 h. D, relative viable cell number in BT-549 cells treated ± 3.5 μM erastin and 1× nucleosides for 48 h. E, cell number as determined by an automated cell counter 24 and 72 h after treatment with 3.5 μM erastin ± 1× nucleosides and 0.5 μM Ferrostatin. F, pictures of BT-549 cells taken after 48 h ± 3.5 μM erastin and 1× nucleosides. The scale bar shown is equal to 100 μm. G–J, relative levels of selected metabolites from BT-549 cells treated with 3.5 μM erastin ± nucleosides. B–D, a one-way ANOVA was performed and followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test when p < 0.05 for ANOVA. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 in Fisher’s LSD test. E, a two-way ANOVA was performed and followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD comparing erastin to erastin + nucleosides and erastin + ferrostatin at each timepoint. Erastin and Erastin + Nucleosides at Day 1 was also compared to Day 3. G–J, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed on log-transformed values and followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test if interaction term or main effect of treatment p < 0.05. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 when comparing Erastin to dimethyl sulfoxide or to Erastin + Nucleosides. Bar is plotted at mean and error bars show standard deviation. Each dot represents one biological replicate.

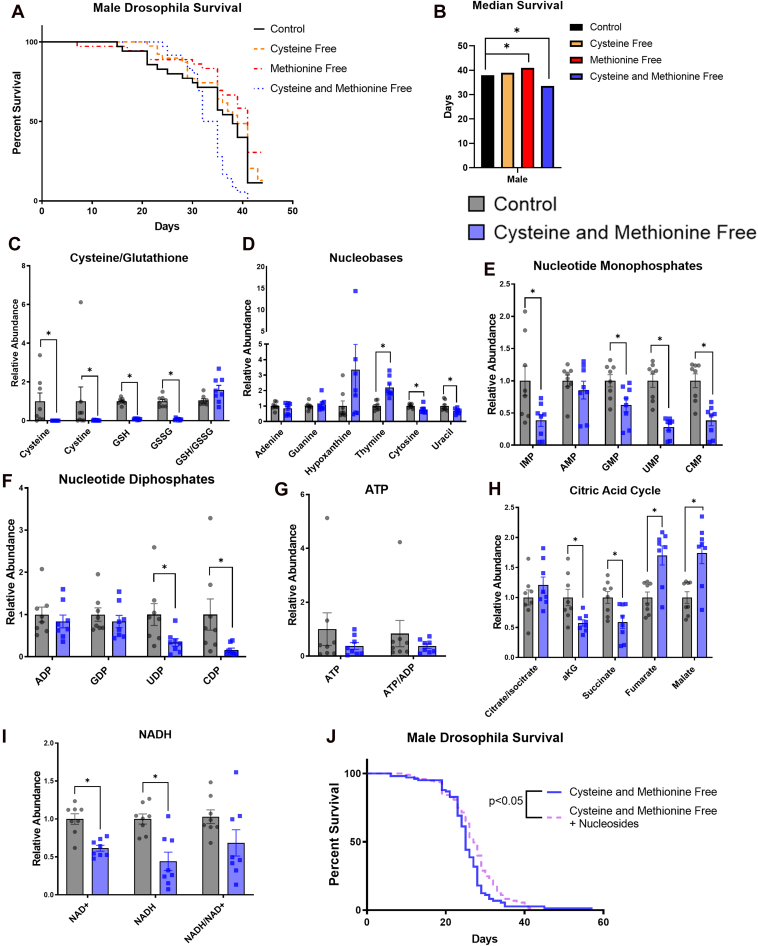

Nucleotide and central carbon metabolism are altered in flies fed a cysteine-deprived diet

We next sought to explore an in vivo model of cysteine and glutathione depletion, which could be relevant to ferroptosis, to determine the following: (1) whether glutathione depletion can be achieved through dietary means and (2) whether similar nucleotide alterations are observed in vivo when cysteine and glutathione are depleted. We speculated that long-term cysteine and glutathione depletion would decrease fly lifespan. Since cysteine is a conditionally essential amino acid and can be synthesized from methionine, we did not know whether dietary cysteine depletion alone would affect fly survival. We therefore depleted cysteine, methionine, or both in the food of male or virgin female w1118 Drosophila melanogaster and assessed survival as compared to flies fed a control chemically defined diet. In male flies, cysteine depletion alone did not affect survival and methionine depletion alone slightly increased median survival but the depletion of both dietary cysteine and methionine significantly decreased median survival (Fig. 5, A and B). In female flies, we saw similar patterns but changes were not statistically significant (Fig. S9, A and B), so we decided to investigate potential dietary-induced metabolic changes in male flies. We fed male flies a control or cysteine- and methionine-free chemically defined diet for 3 weeks and then collected fly bodies and heads for separate metabolic profiling. Fly bodies and heads from flies fed the cysteine- and methionine-free diets showed significantly depleted cysteine and glutathione levels (Figs. 5C and S9C), demonstrating that diet-mediated glutathione depletion is possible. Next, we assessed whether nucleotide alterations occurred in cysteine- and methionine-deprived flies and found significant depletions in nucleotide monophosphates in both the fly head (Fig. S9E) and body (Fig. 5E). We also found depletions in nucleotide diphosphates that were significant in the fly body (Fig. 5F) but not the head (Fig. S9F). ATP was the only nucleotide triphosphate that was measured in the flies and it was depleted in both the head and body but not to a statistically significant level (Figs. S9G and 5G). We also observed significant differences in the TCA3 cycle intermediates in both the head and body (Figs. 5H and S9H) and significantly depleted nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels in the body (Fig. 5I). We wondered whether supplementing nucleosides into the diet of cysteine- and methionine-deprived flies could alter survival. We did not know whether this strategy would be effective in vivo since it would depend on the digestion, absorption, and distribution of dietary nucleosides throughout the body, and because nucleotide depletions may only play a small role in the decreased survival observed in cysteine- and methionine-deprived flies. However, in light of these complications, supplementing 2.5 mM nucleosides into the diet caused a small but significant increase in survival of cysteine- and methionine-deprived male flies (Fig. 5J). Together, these data show that long-term dietary cysteine and glutathione depletion decrease survival and trigger similar in vivo metabolic alterations involving nucleotide metabolism and the TCA cycle as observed in cultured cells.

Figure 5.

Nucleotide and central carbon metabolism are altered in male w1118 Drosophila melanogaster fed a cysteine-deprived diet.A, male w1118 drosophila survival when fed chemically defined diets with or without cysteine and methionine. B, median survival of male flies from survival curves shown in Figure 4, A, C–I. The relative abundance of selected metabolites from male drosophila bodies fed the indicated diets for 3 weeks. Each dot represents one fly. J, male w1118 drosophila survival when fed chemically defined diets without cysteine and methionine ± nucleosides. Nucleosides added into the diet were Inosine, Uridine, Adenosine, Guanosine, Cytidine, and Thymidine (2.5 mM). B, multiple log-rank Mantel-Cox tests were performed to compare male fly survival differences on control versus cysteine/methionine-free diets. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 for these tests, while no star indicates p > 0.05. C–I, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA performed on log-transformed values and followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test if interaction term <0.05. ∗ indicates p < 0.05 for Fisher’s LSD test. J, a log-rank Mantel–Cox test was performed to compare fly survival on cysteine- and methionine-free versus cysteine- and methionine-free + nucleosides diets.

Discussion

Previous studies have linked ferroptosis to nucleotide metabolism through dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (46) and through ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) (47). Here, we show that alterations in nucleotide metabolism account for some of the largest changes in the metabolome of cells treated with ferroptosis inducers erastin and RSL3. This metabolic profile included alterations which have previously been observed in RSL3-treated cells including depleted pyrimidine precursor N-carbamoyl-L-aspartate and elevated uridine (46) but also showed a much wider set of nucleotide alterations in both erastin and RSL3-treated cells including elevated levels of other nucleosides such as adenosine, guanosine, and cytidine, and broadly depleted nucleotide di- and triphosphate levels. These results are also consistent with previously published erastin metabolomics, which showed increased levels of nucleosides in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells (16). This study also measured the levels of some nucleotide mono- and diphosphates, which did not significantly change but this may be due to differences in treatment time and dose.

We investigated two mechanisms through which the nucleotide alterations observed in erastin-treated cells could occur. Tracing with 13C glucose showed that erastin decreases m + 5 labeling on pyrimidines in HT-1080 and BT-549 cells, and on purines in BT-549 cells. Because m + 5 ribose was unaffected, decreased nucleotide biosynthesis under erastin treatment is not likely due to altered pentose phosphate pathway activity and because nucleotides upstream of RNR showed altered labeling, RNR is also unlikely to cause altered nucleotide biosynthesis during erastin treatment. Decreased nucleotide biosynthesis can partially explain why nucleotide depletions occur during erastin treatment but it does not explain why high-energy nucleotide di- and triphosphates were depleted while low-energy nucleotide monophosphates and nucleosides either accumulated or showed smaller depletions. Decreased levels of the ATP/AMP and NADH/NAD+ ratio in erastin-treated cells and induction of AMPK phosphorylation, which has been observed in response to erastin and RSL3 treatment previously (48, 49), can better explain why these nucleotides are depleted. Decreased energy production can also affect nucleotide production because nucleotide biosynthesis requires significant energy input (50).

Our study did not directly measure the source of energy depletion during erastin treatment but the altered 13C glucose labeling seen on glycolysis and TCA intermediates shows that these energy-producing pathways were affected by erastin. Both cell lines showed decreased glycolysis over time under erastin treatment as indicated by altered pyruvate and lactate m + 3 pools. This likely contributed to at least some of the energy depletion caused by erastin. Many metabolic enzymes, including several glycolytic and TCA enzymes, are affected by reactive oxygen species (51) and the significant glutathione depletion caused by erastin treatment is likely to affect one or more of these enzymes through loss of redox homeostasis (52). Lipid peroxidation has been observed in mitochondria (53, 54) and could also target enzymes in these and other pathways. Cysteine is also required for Co-A synthesis, which is used in the TCA cycle, fatty acid synthesis, and beta-oxidation, which could all affect energy levels in erastin-treated cells outside of lipid peroxidation. Notably, the ATP/AMP ratio was only partially rescued by ferrostatin in erastin-treated cells but fully rescued by ferrostatin in RSL3-treated cells, indicating that this could be the case. A limitation of the study was only focusing on possible mechanisms of erastin-induced nucleotide alterations and not those of other ferroptosis inducers such as RSL3 or of genetic methods of ferroptosis induction.

Previous studies have found that increased reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria can contribute to ferroptosis (55, 56) and that erastin-induced ferroptosis can be inhibited by suppressing the TCA (53). It has also been suggested that erastin increases mitochondrial metabolism through the opening of voltage-dependent anion channels in the outer mitochondrial membrane (55). Our study found that TCA intermediates were depleted in erastin-treated HT-1080 and BT-549 cells. However, the two cell lines had opposite patterns in terms of 13C glucose labeling of TCA intermediates through pyruvate dehydrogenase, with HT-1080 cells showing increased glucose usage in the TCA and BT-549 cells showing decreased. Increased glucose usage in the TCA in erastin-treated HT-1080 cells may partially compensate for loss of glycolytic activity or decreased use of other TCA fuel sources. We did not determine whether blocking mitochondrial metabolism contributed to or suppressed erastin-induced cell death, but our results do show that mitochondrial metabolism is affected differently in different cell lines, and caution should be used when generalizing the results obtained from a single model.

Our results show that a major effect of erastin-treated cells is nucleotide depletion and that supplementing cysteine-deprived cells with exogenous nucleosides can partially rescue diminished cell proliferation at intermediate doses of erastin. These results indicate that the nucleotide changes observed in the metabolic profile of erastin-treated cells have a functional impact on cellular fitness. Restored nucleotide levels likely improve the rates of macromolecule biosynthesis and repair (50). Glutathione depletion by erastin and other methods has shown to synergize with numerous chemotherapies including those that interfere with nucleotide synthesis (57). Our study offers a plausible mechanism for why these synergisms occur. RSL3-treated cells showed a very similar metabolic profile to erastin-treated cells but exogenous nucleosides did not rescue viable cell number under RSL3 treatment in any cell line tested. We did not investigate why this is but speculate that it may have to do with differences in the onset, strength, and location of lipid peroxidation caused by erastin versus RSL3. The efficacy of whether the exogenous nucleoside cocktail rescues viable cell number and nucleotide levels in erastin-treated cells likely depends on several factors including the extent to which nucleotide depletions are caused by insufficient nucleotide biosynthesis and salvage versus insufficient energy levels, the speed and ability of cells to salvage the nucleosides from the cocktail, and the role reduced nucleotide levels play in decreasing cellular fitness in different cell lines and conditions.

Our study also showed that glutathione depletion can be achieved through dietary methods. Long-term cysteine and methionine restriction significantly decreased the lifespan of male flies and had a similar effect on virgin female flies that was not statistically significant. We also observed similar nucleotide and TCA cycle changes in the metabolic profile of male flies subjected to a cysteine- and methionine-free diet as seen in cultured cancer cells treated with erastin. Drosophila have multiple GPX4 homologs, including one which uses thioredoxin instead of glutathione as a cofactor (58). Cysteine depletion would likely still affect thioredoxin, because thioredoxin also uses cysteine for its reduction ability but the relevance of Drosophila as a research model for ferroptosis still needs to be established. Cysteine restriction in flies could also potentially affect survival by limiting the production of cysteine-dependent metabolites such as hydropersulfides, Co-A, or protein synthesis. Drosophila also have a homolog to the xCT subunit of system xc-, which can influence behavior through its effects on extracellular glutamate concentrations in the brain (59). Because altered system xc- activity (5, 60) and ferroptosis has been implicated in neurological disease (24, 61), we questioned whether the metabolic profile of fly heads would differ from fly bodies but found almost identical metabolic changes. Supplementing nucleosides into the diet of the cysteine-deprived flies caused a small but statistically significant increase in median survival, suggesting that the nucleotide depletions observed in the metabolic profile of cysteine-deprived flies may play a role in their decreased survival.

Changes in nucleotide triphosphate levels and other changes to nucleotide metabolism have been connected to neurologic diseases such as Lesch–Nyhan disease (62, 63) and Huntington’s disease (64, 65, 66), the latter of which has also been connected to ferroptosis (20). Interestingly, elevated hypoxanthine levels were observed in patients with neurologic disease (63), which we also observed in the heads of cysteine-deprived flies and in erastin and RSL3-treated HT-1080 cells.

In summary, our study shows that nucleotide metabolism is linked to cysteine availability and erastin-induced ferroptosis which can play a role in diminished cell proliferation in certain contexts. Further, it also establishes that glutathione depletion causes alterations to nucleotide synthesis through several mechanisms but not entirely through a single step involving an enzyme such as RNR or dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Given these links many questions in disease biology such as cancer and neuropathology are open for further investigation.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture

BT-549, HT-1080, and U2OS cells were purchased from the Duke Cell Culture Facility and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, F2442). Cells were cultured in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 atmosphere. All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Cell viability assays

Cells were seeded at a density of 2 to 4 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates with water in the outside wells and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were treated the following day by replacing the seeding media with 100 μl treatment media containing drug treatments or nutrient restricted media and any rescue agents. Cells were incubated in treatment media for the indicated period of time and then MTS reagent ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium)) purchased from Abcam, (ab197010) was mixed 1:1 with sterile PBS and 20 μl of the mixture was added to each well. Cells were incubated with MTS reagent for 2 h and after brief shaking absorbance was read at 490 nm on a microplate reader.

IC50 dose determinations

For each cell line, IC50 doses of erastin and RSL3 were determined by seeding cells at a density of 2 to 4 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates with water in the outside wells. Doses of erastin ranging from 0 to 50 μM were added to wells in triplicate and doses of RSL3 ranging from 0 to 1.5 μM were added to wells in triplicate. Cells were incubated with erastin/RSL3 for 24 h and then MTS cell viability assays were performed as described. IC50 dose curves were plotted and an IC50 dose for each drug in each cell line was calculated based off the curve.

Drugs and rescue agents

Erastin (17754), RSL3 (19288), and Ferrostatin-1 (17729) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. The “1× nucleosides” were EmbryoMax Nucleosides purchased from MilliporeSigma (ES-008-D).

Cystine deprivation

Low cystine media was made from RPMI without L-glutamine, L-cystine, L-methionine, and L-cysteine (MP Biomedicals 1646454) supplemented with 10% dialyzed heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (VWR SH30079.03). L-methionine (Amresco E801) and L-glutamine (Amresco 0374) were added back to the media to the concentration found in RPMI 1640 and L-Cystine (Amresco J993) was added back to control media but not to cystine-free media. Both control and cystine-free media were adjusted to pH 7.4 and then sterilized using a 0.10 μm filter (MilliporeSigma S2VPU02RE). To find an equivalent level of cystine deprivation that matched the level of cell viability/proliferation reduction caused by erastin in HT-1080 cells, we added varying levels of control media to the cystine-free media and measured cell viability after 24 h (the same way IC50 doses of erastin were found) and selected 7.5% cystine for the low-cystine media used in the rescue experiment.

Cell counting

Cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were treated the following day by replacing media with 2 ml treatment media containing drug treatments and rescue agents. After 1 or 3 days of treatment, cells were trypsinized and then counted on a MOXI Z automated cell counter (Orflo).

Microscopy

Cells were seeded at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight prior to treatment. Cells were incubated in treatment media for 48 h prior to imaging. Images were captured using a Leica DM IL LED microscope equipped with a Leica MC170HD camera at ×10 objective using LAS EZ software (Leica, https://www.leica-microsystems.com/products/microscope-software/p/leica-las-ez/downloads/). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Western blotting

Total cell protein was extracted with lysis buffer (radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. R0278) containing 1% protease-phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. PI78440). Protein concentrations were measured with the bicinchoninic acid Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no.23224). Total protein was resolved on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 1704156) by Trans-Blot Turbo (Bio-rad). After 5% bovine serum albumin blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies containing AMPKα (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 2532), Phospho-AMPKα (AMP-activated protein kinase) (Thr172) (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 2531) and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 4970) overnight at 4 °C separately. Secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 7074) was probed for 1 h at room temperature. The chemiluminescence signal intensity of protein was detected with chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. PI34096) and the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-rad). The dilutions for the antibodies are as follows:

Anti-AMPK/pAMPK: 1:1000.

Anti-Actin: 1:5000.

Anti-Rabbit: 1:5000.

Stable isotope labeling

Cells were seeded at 8 × 104 cells per well into six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight prior to treatment. Treatment media was added to cells for 4 h and then replaced with U-13C glucose-containing treatment media, in which cells were cultured in for 12 h. The U-13C glucose-containing treatment media was made from glucose-free RPMI (Gibco 11,879–020) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, F2442) with [U-13C] glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, #CLM-1396) added at 2 g/L. Metabolites were then extracted and measured via LC-MS according to the protocols below.

Polar Metabolite Extraction from cells

Polar metabolite extraction was conducted as described (38, 39). Briefly, 8 to 12 × 104 cells per well were seeded into six-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight prior to treatment.

Cell confluence was equal across conditions at the time of extraction. Following treatment, medium was quickly aspirated, plates were placed on dry ice, and 1 ml of 80% methanol/water extraction solvent (Optima LC-MS grade, Fisher; methanol, #A456; water, #W6) precooled to −80 °C was immediately added to each well prior to transferring the plates to −80 °C for 15 min. The plates were then removed, placed on dry ice, and the cells were scraped into the extraction solvent and transferred to Eppendorf tubes. Metabolite extracts were then centrifuged at 20,000g at 4 °C for 10 min. The solvent in each sample was then transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and evaporated using a speed vacuum.

Polar metabolite extraction from flies

Flies were immobilized on ice and fly heads were separated from the thorax and abdomen (“body”) using tweezers, then both the head and both were flash-frozen in Eppendorf tubes using liquid nitrogen. Two heads a diet group were pooled together to have enough material for extraction. During extraction, the Eppendorf tubes were placed on dry ice and 200 μl 80% methanol precooled to −80 °C was added to each tube. The fly bodies and pooled heads were then homogenized using a tissue homogenizer. After homogenization, an additional 300 μl precooled 80% methanol was added to each tube and tubes were vortexed and then centrifuged at 20,000g at 4 °C for 10 min. The solvent in each sample was then transferred to a new Eppendorf tube and evaporated using a speed vacuum. (note: solvents were the same as used in polar metabolite extraction from Cells.

Liquid chromatography

For polar metabolite analysis, the evaporated cell extracts were first dissolved in 15 μl LC-MS grade water and then15 μl methanol/acetonitrile (1:1 v/v) (Optima LC-MS grade, Fisher; methanol, #A456; acetonitrile, #A955) was added. Finally, samples were centrifuged at 20,000g at 4 °C for 10 min and the supernatants were transferred to LC vials prior to HPLC injection (3 μl).

An XBridge amide column (100 × 2.1-mm inner diameter, 3.5 μm; Waters) was used on a Dionex (Ultimate 3000 UHPLC (ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography)) for compound separation at room temperature. Mobile phase A was water with 5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.9 and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. The gradient is linear as follows: 0 min, 85% B; 1.5 min, 85% B; 5.5 min, 35% B; 10 min, 35% B; 10.5 min, 35% B; 10.6 min, 10% B; 12.5 min, 10% B; 13.5 min, 85% B; and 20 min, 85% B. The flow rate was 0.15 ml/min from 0 to 5.5 min, 0.17 ml/min from 6.9 to 10.5 min, 0.3 ml/min from 10.6 to 17.9 min, and 0.15 ml/min from 18 to 20 min. All solvents are LC-MS grade and were purchased from Fisher.

Mass spectrometry

The Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) is equipped with a heated electrospray ionization probe, and the relevant parameters are listed as follows: evaporation temperature, 120 °C; sheath gas, 30; auxiliary gas, 10; sweep gas, 3; and spray voltage, 3.6 kV for positive mode and 2.5 kV for negative mode. Capillary temperature was set at 320 °C and S lens was 55. A full scan range from 70 to 900 (m/z) was used. The resolution was set at 70,000. The maximum injection time was 200 ms. Automated gain control was targeted at 3 × 106 ions.

Peak extraction and data analysis

Raw data collected from LC-Q Exactive Plus MS was processed on Sieve 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peak alignment and detection were performed according to the protocol described by Thermo Fisher Scientific. For a targeted metabolite analysis, the method “peak alignment and frame extraction” was applied. An input file of theoretical m/z and the detected retention time was used for targeted metabolite analysis and the m/z width was set to 5 ppm. An output file including detected m/z and relative intensity in different samples was obtained after data processing. If the lowest integrated mass spectrometer signal (MS intensity) was less than 1000 and the highest signal was less than 10,000, then this metabolite was considered below the detection limit and excluded for further data analysis. If the lowest signal was less than 1,000 but the highest signal was more than 10,000, then a value of 1000 was imputed for the lowest signals. For isotope tracing experiments, the mass isotopomer distributions were calculated and normalized by comparing the ratio of labeled to unlabeled metabolites in each sample.

Fly stocks and maintenance

w1118 stocks were kindly provided by Dr Don Fox. Flies were maintained on Nutri-fly food (Genesee Scientific 66–112) at room temperature.

Fly survival

Newly emerged adult male and virgin female flies were collected and sorted under CO2 anesthesia for 3 days prior to the start of survival experiments. On day 0, flies were again subjected to CO2 anesthesia to be randomized to their diet group and were put onto food containing their assigned diet (male and female flies were kept in separate vials with 30–40 flies/vial at the start of the experiment). During the experiment, flies were moved to a new vial of food every 3 to 4 days. Vials were visually inspected for dead flies and deaths were recorded daily each week from Monday to Friday. Flies were reared on benchtops at room temperature, with each different diet group subjected to the same conditions.

Drosophila chemically defined diets

Drosophila diet formulations have been published (67) and were derived from previous recipes (68, 69) with the following modifications: (1) the type of Agar (Micropropagation Agar-Type II; Caisson Laboratories #A037), (2) the final percentage of Agar (1%), (3) the amount of sucrose (25 g), (4) the amino acids that were added to stock solutions before or after autoclaving (70) whose order is described below, and (5) the exclusion of inosine and uridine from the all diets except for the “cysteine and methionine free + nucleosides diet,” which contained 2.5 mM inosine, uridine, adenosine, guanosine, cytidine, and thymidine added into the “Other Nutrients” solution. The amino acid composition of the diet was based on the exome-matched (i.e., the concentrations used for a given amino acid correspond with the prevalence of exons for that amino acid in the Drosophila genome) Drosophila diet formulation developed in a previous study (69) that was found to be optimal for growth and fecundity without compromising lifespan. The rationale for which amino acids were part of the autoclaving process was based on solubility considerations (70).

The complete procedure, formula, and stock solutions for food production are as follows:

(Note: the procedure below was used to create the “control diet.” The cysteine and methionine depleted diets were created the same way but without the addition of cysteine and/or methionine. For these diets, instead of adding the cysteine or methionine stock solution, we added an equal volume of the solution the amino acid would be suspended in to match water content and pH.)

Procedure

-

(1)

Prepare “Part 2” (see below) Mixture and set aside;

-

(2)

Prepare “Part 1” (see below) Mixture, adding everything but agar (not everything will go into solution at this point);

-

(3)

Add agar to “Part 1” Mixture, stir using stir bar;

-

(4)

Autoclave “Part 1” Mixture for 15 min;

-

(5)

Remove “Part 1” Mixture from autoclave, then combine with “Part 2” Mixture and stir;

-

(6)

Quickly pipette food into Drosophila vials (5–10 ml food/vial);

-

(7)

Allow food to solidify/cool for roughly an hour, then cover vials (either with cotton plugs or with plastic wrap), and store food at 4 °C.

Food is good for about 1 month at 4 °C (will shrink and pull away from sides of vials due to loss of water after this).

Note

After autoclaving, “Part 1” Mixture containing agar can start solidifying (both before and after the two mixtures are combined, but combining the two mixtures will cause food to cool down quite a bit and solidify faster). Quickly combine and pour food while autoclaved mixture is still hot to avoid this. Adding water to the autoclave tray and keeping the “Part 1” Mixture in this hot water until ready to combine and pour helps keep it hot and helps prevent premature solidification.

Formula

| Category | Ingredient | Amount of stock per liter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | |||

| Gelling agent | Agar-type II | 10 g | |

| Sugar | Sucrose | 25 g | |

| Metal ions | CaCl2∗6h2o | 1 mL | |

| CuSO4∗5h2o | 1 mL | ||

| FeSO4∗7h2o | 1 mL | ||

| MgSO4 (anhydrous) | 1 mL | ||

| MnCl2∗4h2o | 1 mL | ||

| ZnSO4∗7h2o | 1 mL | ||

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol | 15 mL | |

| Amino Acids | Tyrosine | 0.93 g | |

| Amino Acids | Histidine | 50 mL | |

| Isoleucine | 50 mL | ||

| Methionine | 50 mL | ||

| Phenylalanine | 50 mL | ||

| Threonine | 50 mL | ||

| Valine | 50 mL | ||

| Water | Water (milliQ) | 158 mL |

∗∗AUTOCLAVE 15 min

| Category | Ingredient | Amount of stock per liter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part 2 | |||

| Base | Buffer | 100 ml | |

| Amino Acids | Arginine | 10 mL | |

| Cysteine | 10 mL | ||

| Glutamate | 10 mL | ||

| Glycine | 10 mL | ||

| Lysine | 10 mL | ||

| Proline | 10 mL | ||

| Serine | 10 mL | ||

| Amino Acids | Alanine | 50 mL | |

| Asparagine | 50 mL | ||

| Aspartate | 50 mL | ||

| Glutamine | 50 mL | ||

| Leucine | 50 mL | ||

| Tryptophan | 50 mL | ||

| Vitamin Solution | 21 mL | ||

| Folic Acid | Folic Acid | 1 mL | |

| Other Nutrients Solution | 8 mL | ||

| Preservatives | Propionic acid | 6 mL | |

| methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate | 15 mL | ||

Stock solutions

| Amino acids | Catalog number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| L-Alanine | Sigma, A7469 | 1.10 | H2O |

| L-Asparagine | Amresco, 94,341 | 1.03 | H2O |

| L-Aspartic Acid | Alfa Aesar, A13520 | 1.17 | 0.5 N NaOH |

| L-Glutamine | Amresco, 0374 | 1.12 | H2O |

| L-Histidine | Amresco, 1B1164 | 0.65 | H2O |

| L-Isoleucine | Amresco, E803 | 1.12 | H2O |

| L-Leucine | Sigma, L8912 | 2.03 | 0.2 N HCl |

| L-Methionine | Amresco, E801 | 0.60 | H2O |

| L-Phenylalanine | Sigma, P5482 | 1.01 | H2O |

| L-Threonine | Sigma, T8441 | 1.11 | H2O |

| L-Tryptophan | Amresco, E800 | 0.32 | H2O |

| L-Valine | Amresco, 1B1102 | 1.20 | H2O |

| L-Arginine HCl | Amresco, 0877 | 8.16 | H2O |

| L-Cysteine | Sigma, 30089 | 1.71 | 1 N HCl |

| L-Glutamic acid | Alfa Aesar, A12919 | 7.59 | H2O |

| L-Glycine | Alfa Aesar, A13816 | 3.84 | H2O |

| L-Lysine HCl | Amresco, 0437 | 6.83 | H2O |

| L-Proline | Sigma, P5607 | 4.89 | H2O |

| L-Serine | Sigma, S4311 | 6.89 | H2O |

| L-Tyrosine | Sigma, T8566 | ∗∗add Tyr powder | |

| Vitamin solution | Catalog number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| Biotin | Sigma, B4501 | 0.001 | H2O |

| Ca pantothenate | Sigma, 21,210 | 0.039 | H2O |

| Nicotinic acid | Sigma, N4126 | 0.030 | H2O |

| Pyridoxine HCl | Sigma, P9755 | 0.006 | H2O |

| Riboflavin | Sigma, R4500 | 0.003 | H2O |

| Thiamine (aneurin) | Sigma, T4625 | 0.005 | H2O |

| Folic acid solution | Catalog number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| Folic acid | Sigma F8758 | 0.0250 | 0.004N NaOH |

| Other nutrients solution | Catalog number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| Choline chloride | MP biomedicals, 194,639 | 0.3125 | H2O |

| Myo-Inositol | Sigma, I7508 | 0.0315 | H2O |

| Methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate solution | Catalog Number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| Methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate | Sigma, H3647 | 5.0 | 95% EtOH |

| Buffer | Catalog Number | 50 ml stock | |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | Millipore, AX0074 | 1.5 mL | |

| KH2PO4 | JT Baker, 3246 | 1.5 g | |

| NaHCO3 | Sigma, S8875 | 0.5 g | |

| Water | Up to 50 mL | ||

| Metal ions | Catalog number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| CaCl2∗6h2o | Sigma, 21,108 | 12.5 | H2O |

| CuSO4∗5h2o | Sigma, C7631 | 0.125 | H2O |

| FeSO4∗7h2o | Sigma, F7002 | 1.25 | H2O (store −20C) |

| MgSO4 (anhydrous) | Sigma, M7506 | 12.5 | H2O |

| MnCl2∗4h2o | Sigma, M3634 | 0.05 | H2O |

| ZnSO4∗7h2o | Sigma, Z0251 | 1.25 | H2O |

| Cholesterol solution | Catalog Number | g/50 mL | Suspend in: |

| Cholesterol | Sigma, C8253 | 1 | EtOH |

Catalog Numbers for other reagents:

Sucrose: Sigma, S7903.

Agar: Caisson, A037.

Propionic acid: Sigma, P5561.

Inosine: Sigma, I4125.

Uridine: Sigma, U3003.

Adenosine: Sigma, A4036.

Guanosine: Sigma, G6264.

Cytidine: Sigma, C4654.

Thymidine: Sigma, T1895.

Stocks can be stored at 4 °C for several months unless otherwise specified.

Statistics

Details on individual statistical tests are described in figure legends. Unless stated otherwise, bar graphs plot the mean and error bars show standard deviation. Individual dots represent one biological replicate.

Data availability

All metabolomics datasets are available on GITHUB via https://github.com/LocasaleLab/Allen-et-al-2022.git. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

A. E. A. and J. W. L. conceptualization; A. E. A. validation; A. E. A., Y. S., and F. W. investigation; A. E. A. formal analysis; A. E. A. and J. W. L. writing-original draft; A. E. A. and J. W. L. writing-review and editing; A. E. A. visualization; A. E. A. and J. W. L. supervision; M. A. R. and J. W. L methodology; A. E. A. and J. W. L. project administration; A. E. A., M. A. R., and J. W. L. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

J. W. L. appreciates funding support from the American Cancer Society (129832-RSG-16–214–01-TBE) and the National Institutes of Health (R01CA193256). M. A. R. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society (131615-PF-17–210–01-TBE). A. E. A was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (F31CA232658) and the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) Pharmacological Science Training Program grant (5T32GM007105). J. W. L. advises Restoration Foodworks, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, and Nanocare Technologies.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Ursula Jakob

Supporting information

References

- 1.Sato H., Tamba M., Ishii T., Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith O.W. Biologic and pharmacologic regulation of mammalian glutathione synthesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:922–935. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad M., Sato H. The oxidative stress-inducible cystine/glutamate antiporter, system x (c) (-): cystine supplier and beyond. Amino Acids. 2012;42:231–246. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0867-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu J., Berisa M., Schwörer S., Qin W., Cross J.R., Thompson C.B. Transsulfuration activity can support cell growth upon extracellular cysteine limitation. Cell Metab. 2019;30:865–876.e865. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewerenz J., Hewett S.J., Huang Y., Lambros M., Gout P.W., Kalivas P.W., et al. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(-) in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;18:522–555. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arriza J.L., Kavanaugh M.P., Fairman W.A., Wu Y.N., Murdoch G.H., North R.A., et al. Cloning and expression of a human neutral amino acid transporter with structural similarity to the glutamate transporter gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:15329–15332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meira W., Daher B., Parks S.K., Cormerais Y., Durivault J., Tambutte E., et al. A cystine-cysteine intercellular shuttle prevents ferroptosis in xCT(KO) pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/cancers13061434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber R., Birsoy K. The transsulfuration pathway makes, the tumor takes. Cell Metab. 2019;30:845–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi S., Wada K., Toyooka T., Shinomiya N., Shimazaki H., Nakanishi K., et al. Increased xCT expression correlates with tumor invasion and outcome in patients with glioblastomas. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:33–41. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318276b2de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyoda M., Kaira K., Ohshima Y., Ishioka N.S., Shino M., Sakakura K., et al. Prognostic significance of amino-acid transporter expression (LAT1, ASCT2, and xCT) in surgically resected tongue cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;110:2506–2513. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji X., Qian J., Rahman S.M.J., Siska P.J., Zou Y., Harris B.K., et al. xCT (SLC7A11)-mediated metabolic reprogramming promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression. Oncogene. 2018;37:5007–5019. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0307-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polewski M.D., Reveron-Thornton R.F., Cherryholmes G.A., Marinov G.K., Cassady K., Aboody K.S. Increased expression of system xc- in glioblastoma confers an altered metabolic state and temozolomide resistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016;14:1229–1242. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon S.J., Lemberg K.M., Lamprecht M.R., Skouta R., Zaitsev E.M., Gleason C.E., et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato M., Kusumi R., Hamashima S., Kobayashi S., Sasaki S., Komiyama Y., et al. The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc- and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin's cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon S.J., Patel D.N., Welsch M., Skouta R., Lee E.D., Hayano M., et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W.S., SriRamaratnam R., Welsch M.E., Shimada K., Skouta R., Viswanathan V.S., et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Z., Naowarojna N., Pan Z., Zou Y. Multifaceted mechanisms mediating cystine starvation-induced ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4792. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y., Swanda R.V., Nie L., Liu X., Wang C., et al. mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21841-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weaver K., Skouta R. The selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase 4: from molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Biomedicines. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10040891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skouta R., Dixon S.J., Wang J., Dunn D.E., Orman M., Shimada K., et al. Ferrostatins inhibit oxidative lipid damage and cell death in diverse disease models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4551–4556. doi: 10.1021/ja411006a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linkermann A., Skouta R., Himmerkus N., Mulay S.R., Dewitz C., De Zen F., et al. Synchronized renal tubular cell death involves ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:16836–16841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415518111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedmann Angeli J.P., Schneider M., Proneth B., Tyurina Y.Y., Tyurin V.A., Hammond V.J., et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lőrincz T., Jemnitz K., Kardon T., Mandl J., Szarka A. Ferroptosis is involved in acetaminophen induced cell death. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2015;21:1115–1121. doi: 10.1007/s12253-015-9946-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao M.Y., Liu T., Zhang L., Wang M.J., Yang Y., Gao J. Role of ferroptosis in neurological diseases. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;747 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seibt T.M., Proneth B., Conrad M. Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019;133:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu B., Chen X.B., Ying M.D., He Q.J., Cao J., Yang B. The role of ferroptosis in cancer development and treatment response. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:992. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassannia B., Vandenabeele P., Vanden Berghe T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:830–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockwell B.R., Jiang X., Gu W. Emerging mechanisms and disease relevance of ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30:478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Y., Xie Y., Cao L., Yang L., Yang M., Lotze M.T., et al. The ferroptosis inducer erastin enhances sensitivity of acute myeloid leukemia cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2015;2 doi: 10.1080/23723556.2015.1054549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen L., Li X., Liu L., Yu B., Xue Y., Liu Y. Erastin sensitizes glioblastoma cells to temozolomide by restraining xCT and cystathionine-γ-lyase function. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:1465–1474. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hangauer M.J., Viswanathan V.S., Ryan M.J., Bole D., Eaton J.K., Matov A., et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature. 2017;551:247–250. doi: 10.1038/nature24297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L., Kon N., Li T., Wang S.J., Su T., Hibshoosh H., et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roh J.L., Kim E.H., Jang H.J., Park J.Y., Shin D. Induction of ferroptotic cell death for overcoming cisplatin resistance of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;381:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan X., Lin Z., Jiang D., Yu Y., Yang D., Zhou H., et al. Erastin decreases radioresistance of NSCLC cells partially by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis. Oncol. Lett. 2019;17:3001–3008. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.9888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin W., Wang C., Liu G., Bi C., Wang X., Zhou Q., et al. SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: biological functions and therapeutic implications. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020;10:3106–3126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng J., Conrad M. The metabolic underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 2020;32:920–937. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X., Ser Z., Cluntun A.A., Mentch S.J., Locasale J.W. A strategy for sensitive, large scale quantitative metabolomics. J. Vis. Exp. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X., Ser Z., Locasale J.W. Development and quantitative evaluation of a high-resolution metabolomics technology. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:2175–2184. doi: 10.1021/ac403845u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barankiewicz J., Cohen A. Impairment of nucleotide metabolism by iron-chelating deferoxamine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987;36:2343–2347. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miotto G., Rossetto M., Di Paolo M.L., Orian L., Venerando R., Roveri A., et al. Insight into the mechanism of ferroptosis inhibition by ferrostatin-1. Redox Biol. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reid M.A., Allen A.E., Liu S., Liberti M.V., Liu P., Liu X., et al. Serine synthesis through PHGDH coordinates nucleotide levels by maintaining central carbon metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5442. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jitrapakdee S., Vidal-Puig A., Wallace J.C. Anaplerotic roles of pyruvate carboxylase in mammalian tissues. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:843–854. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5410-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buescher J.M., Antoniewicz M.R., Boros L.G., Burgess S.C., Brunengraber H., Clish C.B., et al. A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moskovitz J., Bar-Noy S., Williams W.M., Requena J., Berlett B.S., Stadtman E.R. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is a regulator of antioxidant defense and lifespan in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12920–12925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231472998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao C., Liu X., Zhang Y., Lei G., Yan Y., Lee H., et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature. 2021;593:586–590. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03539-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarangelo A., Rodencal J., Kim J.T., Magtanong L., Long J.Z., Dixon S.J. Nucleotide biosynthesis links glutathione metabolism to ferroptosis sensitivity. Life Sci. Alliance. 2022;5 doi: 10.26508/lsa.202101157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X., Lu S., He C., Wang C., Wang L., Piao M., et al. RSL3 induced autophagic death in glioma cells via causing glycolysis dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;518:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang K., Zhang Z., Tsai H.I., Liu Y., Gao J., Wang M., et al. Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase 2 regulates ferroptotic cell death in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:1222–1236. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00644-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lane A.N., Fan T.W. Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucl. Acids Res. 2015;43:2466–2485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quijano C., Trujillo M., Castro L., Trostchansky A. Interplay between oxidant species and energy metabolism. Redox Biol. 2016;8:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lushchak V.I. Glutathione homeostasis and functions: potential targets for medical interventions. J. Amino Acids. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/736837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao M., Yi J., Zhu J., Minikes A.M., Monian P., Thompson C.B., et al. Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol. Cell. 2019;73:354–363.e353. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feng H., Stockwell B.R. Unsolved mysteries: how does lipid peroxidation cause ferroptosis? PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeHart D.N., Fang D., Heslop K., Li L., Lemasters J.J., Maldonado E.N. Opening of voltage dependent anion channels promotes reactive oxygen species generation, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;148:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H., Liu C., Zhao Y., Gao G. Mitochondria regulation in ferroptosis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2019.151058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niu B., Liao K., Zhou Y., Wen T., Quan G., Pan X., et al. Application of glutathione depletion in cancer therapy: enhanced ROS-based therapy, ferroptosis, and chemotherapy. Biomaterials. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Missirlis F., Rahlfs S., Dimopoulos N., Bauer H., Becker K., Hilliker A., et al. A putative glutathione peroxidase of Drosophila encodes a thioredoxin peroxidase that provides resistance against oxidative stress but fails to complement a lack of catalase activity. Biol. Chem. 2003;384:463–472. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grosjean Y., Grillet M., Augustin H., Ferveur J.F., Featherstone D.E. A glial amino-acid transporter controls synapse strength and courtship in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nn2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kigerl K.A., Ankeny D.P., Garg S.K., Wei P., Guan Z., Lai W., et al. System x(c)(-) regulates microglia and macrophage glutamate excitotoxicity in vivo. Exp. Neurol. 2012;233:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren J.X., Sun X., Yan X.L., Guo Z.N., Yang Y. Ferroptosis in neurological diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:218. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fairbanks L.D., Jacomelli G., Micheli V., Slade T., Simmonds H.A. Severe pyridine nucleotide depletion in fibroblasts from Lesch-Nyhan patients. Biochem. J. 2002;366:265–272. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pesi R., Micheli V., Jacomelli G., Peruzzi L., Camici M., Garcia-Gil M., et al. Cytosolic 5'-nucleotidase hyperactivity in erythrocytes of Lesch-Nyhan syndrome patients. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1827–1831. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ismailoglu I., Chen Q., Popowski M., Yang L., Gross S.S., Brivanlou A.H. Huntingtin protein is essential for mitochondrial metabolism, bioenergetics and structure in murine embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol. 2014;391:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toczek M., Pierzynowska K., Kutryb-Zajac B., Gaffke L., Slominska E.M., Wegrzyn G., et al. Characterization of adenine nucleotide metabolism in the cellular model of Huntington's disease. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucl. Acids. 2018;37:630–638. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2018.1481508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomczyk M., Glaser T., Slominska E.M., Ulrich H., Smolenski R.T. Purine nucleotides metabolism and signaling in huntington's disease: search for a target for novel therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6545. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gu X., Jouandin P., Lalgudi P.V., Binari R., Valenstein M.L., Reid M.A., et al. Sestrin mediates detection of and adaptation to low-leucine diets in Drosophila. Nature. 2022;608:209–216. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04960-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Piper M.D., Blanc E., Leitão-Gonçalves R., Yang M., He X., Linford N.J., et al. A holidic medium for Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Met. 2014;11:100–105. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Piper M.D.W., Soultoukis G.A., Blanc E., Mesaros A., Herbert S.L., Juricic P., et al. Matching dietary amino acid balance to the in silico-translated exome optimizes growth and reproduction without cost to lifespan. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davis R.W., Botstein D., Roth J.R., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Advanced Bacterial Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: Cold Spring Harbor; NY: 1980. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All metabolomics datasets are available on GITHUB via https://github.com/LocasaleLab/Allen-et-al-2022.git. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.