Abstract

Background

Legalization of assisted dying (AD), including euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, remains a highly contentious issue as more jurisdictions around the world consider AD laws. Important concerns exist related to legalization of AD with regard to vulnerable populations and monitoring and reporting systems.

Methods

A selective literature review was performed to explore the developments under assisted dying laws globally. An array of issues and key publications were selected based on the authors’ previous research and knowledge.

Results

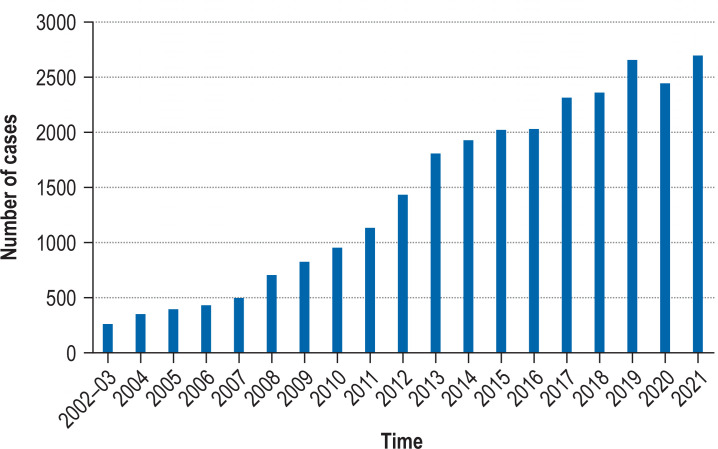

The experience in Belgium can provide an instructive example about the evolution of AD laws. Since legalization, AD practice has increased gradually (0.2% of all deaths in 2002–2003 to 2.4% in 2021), accompanied by a diversification of the patient groups and by broadening acceptance among physicians and the public. Fears relating to disregard of regulatory safeguards and thwarted palliative care development have largely been allayed. Nonetheless, there are important points that require continued attention, for which ongoing monitoring and research is essential.

Conclusion

Research in Belgium has not found evidence of suicide contagion, expansion to minors, or an increase in non-voluntary forms of life-ending. AD legislation should always be accompanied by careful consideration for integration into the health care system, physician training and support, possible conscientious objection, availability of palliative care services, clinical guidelines, public education, and monitoring systems.

Many jurisdictions are debating legalization of assisted dying (AD), which can include euthanasia—i.e. intentionally ending the life of a patient by a physician administering medications at the patient’s explicit request—and physician-assisted suicide (PAS)—i.e. a physician prescribing or providing medications for a patient to use to end their own life (1). Currently, euthanasia is legal in twelve jurisdictions: the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Colombia, Canada, New Zealand, five Australian states, and Spain (1). Physician-assisted suicide without the option for euthanasia, is legally practiced in Switzerland, Austria and eleven US jurisdictions (1). In Italy and Germany, courts recently declared the criminalization of assisted suicide unconstitutional, though Italy has extremely narrow eligibility criteria, and the German high court ordered a reform of the current legislation (1, 2) (table 1). While most AD legislation is limited to those with terminal illness due to somatic disorders, the Benelux countries and Canada (from 2023 onwards) allow requests based on psychiatric illness or dementia, provided the patient is competent (3, 4).

Table 1. Jurisdictions with AD laws and frequency of reported euthanasia and assisted suicide.

| Jurisdiction | Year of law passage or decision | Euthanasia and/or PAS | Type of legislation or decision | Latest year with known number of deaths | Number of annual deaths by euthanasia and/or PAS | Percentage of all deaths |

| Europe | ||||||

| Austria | 2021 | PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Germany | 2020 | PAS | Decriminalization | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Italy | 2019 | PAS | Decriminalization | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Spain | 2021 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Switzerland | 1942 | PAS | Decriminalization | 2015 | 965 | 1.4% |

| Netherlands | 2002 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 2019 | 6361 | 4.2% |

| Belgium | 2002 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 2021 | 2699 | 2.4% |

| Luxembourg | 2009 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 25 | *1 |

| America | ||||||

| Canada | 2016 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 2019 | 5631 | 2.0% |

| Colombia | 1997 | Euth., PAS | Court ruling | 2021 | 47 | *1 |

| USA | ||||||

| – Oregon | 1997 | PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 245 | *1 |

| – Washington | 2009 | PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 252 | *1 |

| – Montana | 2009 | PAS | Court ruling | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| – Vermont | 2013 | PAS | Legislation | 2017–2019 | 28*2 | *1 |

| – California | 2015 | PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 435 | 0.1% |

| – Colorado | 2016 | PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 145 | *1 |

| – District of Columbia | 2016 | PAS | Legislation | 2018 | 2 | *1 |

| – Hawaii | 2018 | PAS | Legislation | 2019 | 23 | *1 |

| – Maine | 2019 | PAS | Legislation | 2019 | 1*3 | |

| – New Jersey | 2019 | PAS | Legislation | 2019 | 12*4 | *1 |

| – New Mexico | 2021 | PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Australia | ||||||

| Victoria | 2017 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 2020 | 175 | *1 |

| Western Australia | 2019 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Northern Territory | 1995 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | 1996–1997 | 7 | *1 |

| Queensland | 2021 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| South Australia | 2021 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| Tasmania | 2021 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

| New Zealand | 2019 | Euth., PAS | Legislation | *1 | *1 | *1 |

*1 Data not (yet) available

*2 Number of medical aid in dying cases between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2019

*3 Number of medical aid in dying cases between 19 September 2019 and 31 December 2019

*4 Number of medical aid in dying cases between 1 August 2019 and 31 December 2019

Euth., Euthanasia; PAS, physician-assisted suicide

It is important to examine the evolution of AD practices in countries with long-standing laws and evaluate practical arguments for and against legalization. Based on official statistics and independent research, broad trends after legalization are described. Experiences from Belgium feature predominantly, primarily due to the combination of available empirical data and the authors’ detailed knowledge of regional and historical developments. Data cited here is based on referenced research and reporting to government bodies and is likely representative for all obvious euthanasia cases in Belgium.

Evolution of euthanasia practice following legalization

In Belgium, there has been continuous increase of AD practice since legalization, from 235 cases (0.2% of all deaths) in 2003 (5, 6) to 2699 cases (2.4% of all deaths) in 2021 (7) (figure 1). Evolutions refer to an initial phase where acceptance and uptake of euthanasia practice increase only incrementally and a second phase when there is broader implementation as physicians and health systems collectively become more familiar and comfortable with what is legally allowed and acceptable.

Figure 1.

Evolution of number of annually reported euthanasia cases to the Federal Control and Evaluation Commission for Euthanasia (FCECE) 2002–2021

A survey in Flanders, Belgium, which included 3750 physicians, estimated that the general rise in prevalence in this sample is due to a rise in number of euthanasia requests or PAS (3.5% of deaths in 2007 to 6.0% in 2013), as well as a rise in the granting rate (56.3% in 2007 to 76.8% in 2013) (6). The rate of euthanasia increased in this period by a factor of >2 (6). Several factors likely contributed to these trends: a reduction in barriers such as prohibitive institutional policies and physicians’ conscientious objections; evolving attitudes and cultural shifts, which prioritize autonomy and self-determination; along with higher levels of acceptance of euthanasia among medical professionals and the population, growing familiarity with AD practice among physicians, and education and training (8, 9). Additional factors include professional support systems and less concern about prosecution when due care criteria are followed (10– 12). However, controversies have also occurred. In 2019, three Belgian physicians were put on trial in a euthanasia case contested by the bereaved family (12). No physicians were convicted. In the Netherlands and in Oregon, there are few instances of physicians being convicted in AD cases, some resulting in symbolic or suspended sentences (13, 14). The 2007–2013 trend is based on the Flemish survey (6, 8) which includes: reported cases, unreported gray zone cases (those not clearly identified as euthanasia or PAS), and requests not leading to AD, while the statistics in Table 1 include all of Belgium and is limited to reported cases.

The profiles of people requesting and receiving euthanasia have also changed in Belgium 8. While initially largely restricted to cancer patients, the practice gradually broadened to include other medical conditions such non-malignant lung disease, cardiovascular disease, old age-related multimorbidity (5), even early-onset dementia and psychiatric conditions. While cancer groups continue to have the largest absolute and relative access, research shows a trend towards more equal granting rates in other conditions (5). Also, older people and people with lower educational attainment are requesting and receiving euthanasia more often than during the first years of the law (5).

The proportion of euthanasia cases based on psychiatric disorders or dementia also increased (0.5% [n=10] of all cases in 2002–2007 to 3.0% [n=54] in 2013) (3), though it remains limited as assessment presents complex clinical-ethical challenges, regarding e.g. competence and irremediable suffering (3, 15). This has necessitated the establishment of clinical guidelines as the law provides scant concrete guidance on evaluating legal criteria in such cases (15).

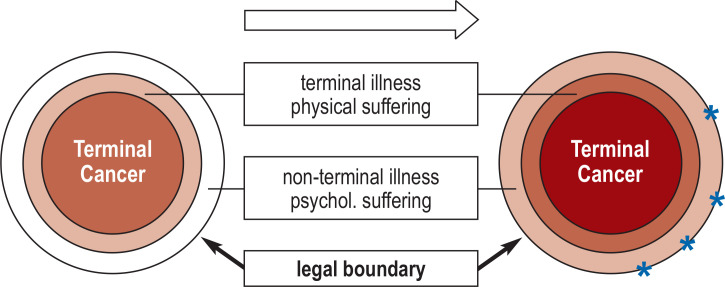

Having years of experience with the law is thought to have increased awareness and acceptance about the legal options in cases involving groups such as the non-terminally ill, minors and those with predominantly mental suffering (3). This process of adoption and expansion represents a conceptual gradual “filling” of the existing legal space, with the practice starting with patients who are the most obviously eligible candidates (most notably, terminally ill and imminently dying cancer patients), then gradually moving towards eligibility requirements which are no longer as clear, to include groups with non-terminal illness and/or psychological suffering, such as people with psychiatric conditions (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gradual expansion of AD practice in Belgium 2002

Darkest colors represent the most frequent patient groups, lighter colors represent the less frequent patient groups. Peripheral stars represent extreme cases heavily discussed in academic and public debate.

Occasionally, extreme cases are reported in popular media, of people requesting or having received euthanasia but with conditions or in contexts which are highly controversial. These cases fuel the ethical debate about the limits of euthanasia legislation (15). The gradual expansion described here largely runs parallel to experiences in the Netherlands (16).

The impact of AD laws on medical professionals varies and is influenced by whether euthanasia or PAS is legalized, or both. Although PAS is rarely chosen by patients over euthanasia in jurisdictions where both options are available, PAS might be preferred as it places less burden on the physician and the responsibility rests with the patient (17). In those jurisdictions where only PAS is legalized, the prevalence and rate of increase is much lower than in those jurisdictions where euthanasia is also an option, e.g. the frequency of PAS in Oregon is significantly less than the AD numbers in the Netherlands (18). In Belgium, the frequency of PAS was 0.05% of all deaths, while in the Netherlands it was 0.1% (17). The physician involved in deaths with euthanasia or PAS is a general practitioner in 93% of cases in the Netherlands, 60% in Belgium and 71% in Switzerland (17). Although physicians can exercise conscientious objection and decline to participate in AD, concerns related to the wellbeing of physicians involved in AD practices exist as participation can potentially contrast with personal expectations about professional roles and responsibilities (19). Research has shown that some physicians experience emotional burden or discomfort, while findings also identified satisfaction in meeting the needs of patient (20).

Specific ‘slippery slope’ debates

The “slippery slope” argument suggests that inevitable expansion will occur after legalization and will result in error, misuse and harm to vulnerable populations such as older people, minors and people with disabilities or psychiatric conditions (1). We review some of the specific arguments for which data is available.

Suicide contagion

Opponents of AD legalization frequently raise concerns about the potential for suicide contagion: a phenomenon where exposure to the option of AD would trigger suicidal ideation and behavior in vulnerable individuals (21). However, statistics in Belgium before and since the implementation of Euthanasia Law of 2002 do not indicate any association between enactment of legislation and suicide rates among the general population, nor has such a link been established empirically elsewhere (21).

Minors

There has been worldwide attention on Belgium’s legal extension to non-emancipated minors in 2014, and some have asserted the amendment was evidence of a “slippery slope” (22). However, it was disputed that using calendar age for eligibility was arbitrary and minors with terminal illness mature more rapidly (22). The extension was ultimately approved with stricter eligibility criteria, limiting access to patients who possess the capacity for discernment, have a short life expectancy, and physical, not mental suffering. The capacity for discernment is not defined, which results in some level of subjectivity and interpretation. Between 2014 and 2020, there have been four cases since the implementation of this law and it has been argued that in light of the political environment and legislative outcome, the amendment was mainly of symbolic value (22).

Life ending acts without explicit request. Another concern relates to the demonstrated existence of physicians’ practice of administering medications to dying patients with the intention of hastening death without the explicit request of the patient (23). Critics condemn this prohibited practice and often point to the euthanasia law as being responsible for this phenomenon. However, several facts contradict this conclusion (box 1). Also, a study in Belgium challenged the idea that these acts are unambiguously equal to nonvoluntary termination of life, as most cases reported in a physician survey were actually in line with patients’ wishes, were probably misinterpreted by physicians to have had a life-shortening effect, and/or had the primary goal of symptom management (24). Nonetheless, the practice has persisted after AD legalization, leading to the conclusion that AD legislation does not eradicate this practice completely (6).

BOX 1. Euthanasia laws and life ending acts without explicit request.

Factors contradicting an association between euthanasia laws and life ending acts without explicit request:

The practice was found to occur before the euthanasia law (e.g. in the Netherlands it was responsible for 0.8% of all deaths in 1990 and 0.7% in 1995 and 2001) (25)

The rate decreased substantially after implementation of the euthanasia law (e.g. in Belgium it preceded 3.2% of all deaths in 1998 and it fell to 1.8 in 2007 and 1.7 in 2013) (6, 25)

The practice also occurs in other countries without AD laws (e.g. Denmark, Italy, Sweden, UK) (25)

Reporting, monitoring & safeguards

There is wide consensus that AD should be closely monitored to ensure compliance with all legal requirements, though opponents referring to the ‘slippery slope’ argue that over time AD safeguards will be more loosely followed and reporting failures will increase 26. In Belgium, euthanasia requests must be evaluated by an attending physician as well as a consulting physician, and performed cases reported to the Federal Control and Evaluation Commission for Euthanasia (FCECE) (27). While every jurisdiction to pass AD legislation has implemented similar procedural requirements and safeguards, there are persistent concerns about adherence (1). A Belgian survey found that 15–23% of physicians hold negative attitudes toward procedural requirements in euthanasia practice, i.e. consulting with a second independent physician when dealing with a request and reporting the case to the federal review committee (highest among French-speaking physicians) (28). Nonetheless, a 2013 study found that peer consultation was conducted in over 90% of cases (6, 28). More information on the process for requesting and evaluating euthanasia cases has been detailed (29).

The rate of legal reporting of euthanasia cases—estimated through mortality follow-back surveys—increased, from 54% in 2007 to 64% in 2013 in Flanders, Belgium (30). In the Netherlands, legal reporting also increased over time and has remained stable at over 80% (29).

Concerns have been raised about unreported and therefore unevaluated cases, inadequate monitoring of reported cases, inaction on cases not complying with requirements, and the FCECE’s composition and authority, which positions it to interpret the law without significant constraint 27. The issue of unreported cases is of key concern: research using rigorous anonymity procedures indicates that these cases are typically not reported because physicians do not consider the case as euthanasia but rather as intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms or as palliative sedation using non-recommended drugs such as opioids and benzodiazepines (30– 32). In Belgium, death certificates have been found to significantly underestimate the frequency of euthanasia as a cause of death in Belgium (33). Further research, including mortality follow-back studies, are critical for monitoring assisted dying practices.

Impacts on palliative care (PC)

Critics raise concerns that AD legislation diminishes the focus on the need for adequate PC, thwarting its development as a young discipline (34). This concern is intensified by perceptions of intrinsic ethical and philosophical incompatibilities (35). Moreover, many fear that patients would request and receive AD in the absence of good PC. Though it is difficult to establish the ripple effects, policy makers in Belgium chose to enact a twin law to boost capacity and ensure universal coverage of PC services (36). The Federation for Palliative Care Flanders argued for compatibility between PC and AD and promoted integration, i.e. the option of AD at the end of an extensive PC trajectory (37). Belgium is unique as such a ‘close’ relationship is not found in other countries implementing AD laws, with many PC physicians and organizations firmly in opposition of AD (19, 35).

That said, data from the Benelux countries suggests that PC development has advanced under AD legislation (34). In Flanders, the evidence points toward a considerable involvement of PC workers in patients receiving AD (5): 71% of AD cases took place within or after a PC trajectory (37). However, the long-term effects of legalization are still unknown, and nations considering legalization should strongly consider concurrently enhancing PC services (34).

Conclusion

The Belgian experience teaches us that AD practice gradually increases and diversifies in terms of the groups accessing it. Continued research has informed the ethical and policy debate, specifically around practical ‘slippery slope’ arguments and impacts on the wider end-of-life landscape, with the intermediate conclusion that fears have been largely unconfirmed, though probable limitations in the documentation must be considered. Yet, such effects are extremely difficult to establish, particularly without a systematic approach or formal mandate for longitudinal monitoring. Adequate knowledge of evolutions and problems in AD practice should always inform discussions of potential adjustment or expansion of AD legislation. Therefore, we recommend the installment of adequate monitoring and evaluation systems and of independent research to evaluate AD practice and wider end-of-life care. In order to address knowledge gaps, specific recommendations for future AD research have been outlined (38). Finally, the implementation of AD laws should always be accompanied by careful consideration for integration into the health care system, physician training and support, possibility of conscientious objection, availability of PC services, clinical guidelines and public education. A high level of transparency and engagement with medical professionals and the public is paramount.

BOX 2. Euthanasia request and procedural requirements in Belgium & The Netherlands.

-

Patient request

The patient request must be voluntary and well-considered

The physician must inform the patient about his/her health condition and treatment possibilities

The physician and patient must come to the belief that there is no reasonable prospect of improvement

-

Procedural requirements

The treating physician must consult another independent physician who provides a formal advice*

Following the euthanasia, the physician must notify the case for review by an Evaluation Committee by means of a legally defined registration form

The Committee evaluates the notified case and determines whether euthanasia was performed in accordance with the legal due care requirements

If the Committee judges that the due care requirements have been met, the case is closed. If it believes the due care requirements have been violated, the case is forwarded for further investigation

* In Belgium: if the patient‘s death is not expected in the foreseeable future, a second independent physician who is a specialist in the disease must also provide advice.

Table 2. Euthanasia evaluation and control procedures in Belgium and the Netherlands (29).

| Belgium | The Netherlands |

| Committees | |

| 1 Federal Control and Evaluation Committee Euthanasia | 5 Regional Euthanasia Review Committees |

| 16 members | 3 members of each committee |

| Committee members are appointed for 4 years, renewable | Committee members are appointed for 6 years, renewable once |

| Composition of committee | |

| 8 physicians | 1 physician |

| 4 professors of law or lawyers | 1 lawyer who is also chairperson |

| 4 persons from the field of palliative care | 1 expert on ethical issues |

| Substitute members are arranged | Substitute members are arranged |

| Balance criteria: – Language parity (half French and half Dutch speakers) – At least three candidates of each gender – Pluralistic representation (members with different life stances) |

Each committee is chaired by a lawyer |

| Procedure | |

| The committee examines the registration forms sent in by the physician | The committees examine the registration forms sent in by the physicians |

| The committee assesses each case on the basis of whether the euthanasia complies with the due care requirements | The committees assess whether each case of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide complies with the due care requirements |

| The committee can make remarks or requests, but a majority vote is required for the anonymity of further information from the physician concerned to be lifted | The committees can make remarks or request further information (orally or in writing) from the physician concerned |

| The committees can initiate an inquiry with the medical examiner, consultant, or caregivers to evaluate the physician's actions | |

| Judgment and report | |

| The committee passes judgement within 2 months | The committees pass judgement within 6 weeks |

| No notification to the physician | Written notification to the physician |

| The case will be closed if the due care requirements are met | The case will be closed if the due care requirements are met |

| The case is forwarded to the King's Prosecutor for further investigation if a two-thirds majority judges the due care requirements to be violated | The case is forwarded to the Assembly of Prosecutors-General and the Regional Inspector for health care for further investigation if two of the three committee members judge the due care requirements to have been violated |

eTable. Assisted dying requirements and safeguards.

| Jurisdiction | Euthanasia | PAS | Diagnosis/prognosis required | Waiting period required | Peer consultation required | Committee review |

| Europe | ||||||

| Switzerland | No | Yes | None specified | None specified | None specified | None specified |

| Netherlands | Yes | Yes | None specified | None specified | Yes | Yes |

| Belgium | Yes | Not legal (but condoned) | Adults: incurable condition Minors: terminal |

None, terminal 1 month, non-terminal |

Yes | Yes |

| Luxembourg | Yes | Yes | Incurable condition | None specified | Yes | Yes |

| Germany | No | Yes | None specified | None specified | Not specified | None specified |

| Italy | No | Yes | Irreversible disease and being kept alive with life support | None specified | Not specified | None specified |

| Spain | Yes | Yes | Incurable disease or serious, chronic and impossible condition | Two written or otherwise recorded requests,15 days apart | Yes | Yes |

| America | ||||||

| Canada | Yes | Yes | Grievous and irremediable medical condition | 10 days written request |

Yes | No |

| Colombia | Yes | Yes | Terminal | Within 15 days after committee approval |

Committee approval required | Yes, before euthanasia or PAS performed |

| USA | ||||||

| – Oregon | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 15 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – Washington | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 15 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – Montana | No | Yes | None specified | None specified | Not specified | None specified |

| – Vermont | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 15 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – California | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 15 days oral request | Yes | None specified |

| – Colorado | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | None specified | Yes | None specified |

| – District of Columbia | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 15 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – Hawaii | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 20 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – Maine | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 17 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – New Jersey | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 18 days oral request, 48 hours written request |

Yes | None specified |

| – New Mexico | No | Yes | Terminal, <6 months | 48 hours after prescription written, *unless death expected sooner |

Yes | None specified |

| Australia | ||||||

| Queensland | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months and unbearable suffering | 9 days, request verbally, or by gestures or other means available | Yes | Yes |

| South Australia | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months (or 12 months for neurodegenerative conditions) | 9 days, request verbally, or by gestures or other means available | Yes | Yes |

| Tasmania | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months (or 12 months for neurodegenerative conditions) | Written request, no wait time specified | Yes | Yes |

| Victoria | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months (or 12 months for neurodegenerative conditions) | 9 days written | Yes | Yes |

| Western Australia | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months (or 12 months for neurodegenerative conditions) | 9 days written | Yes | Yes |

| New Zealand | Yes | Yes | Terminal, <6 months and irreversible decline and unbearable suffering | 48 hours after prescription written and registrar informed | Yes | Yes |

PAS, Physician-assisted dying

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Mroz S, Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Assisted dying around the world: a status quaestionis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:3540–3553. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delbon P, Maghin F, Conti A. Medically assisted suicide in Italy: the recent judgment of the constitutional court. Clin Ter. 2021;72:193–196. doi: 10.7417/CT.2021.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Euthanasia for people with psychiatric disorders or dementia in Belgium: analysis of officially reported cases. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Government of Canada. Medical assistance in dying. www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying.html (last accessed on 30 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Euthanasia in Belgium: trends in reported cases between 2003 and 2013. CMAJ. 2016;188:E407–E414. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Cohen J, Deliens L. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1179–1181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FOD Volksgezondheid, Veiligheid van de Voedselketen en Leefmilieu. Federale controle en evaluatiecommissie euthanasie. https://overlegorganen.gezondheid.belgie.be/nl/advies-en-overlegorgaan/commissies/federale-controle-en-evaluatiecommissie-euthanasie (last accessed on 24 October 2022) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Comparison of the expression and granting of requests for euthanasia in Belgium in 2007 vs 2013. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1703–1706. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smets T, Cohen J, Bilsen J, van Wesemael Y, Rurup ML, Deliens L. Attitudes and experiences of Belgian physicians regarding euthanasia practice and the euthanasia law. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:580–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vissers S, Dierickx S, Chambaere K, Deliens L, Mortier F, Cohen J. Assisted dying request assessments by trained consultants: changes in practice and quality—Repeated cross-sectional surveys (2008-2019) BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022 doi: 10.1136/spcare-2021-003502. DOI: 10.1136/spcare-2021-003502. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Wesemael Y, Cohen J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Bilsen J, Distelmans W, Deliens L. Role and involvement of life end information forum physicians in euthanasia and other end-of-life care decisions in Flanders, Belgium. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:2180–2192. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson R. Assisted dying: Belgian doctors stand trial in landmark case. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m259. m259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen ML. Crossing the rubicon: The Netherlands’ steady march towards involuntary euthanasia Brook J. Int‘l L. www.brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol31/iss2/5 . 2006;31 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leenen HJJ. Euthanasia, assistance to suicide and the law: developments in the Netherlands. Health Policy. 1987;8:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(87)90062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verhofstadt M, van Assche K, Sterckx S, Audenaert K, Chambaere K. Psychiatric patients requesting euthanasia: guidelines for sound clinical and ethical decision making. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2019;64:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Legemaate J, van der Heide A. Derde evaluatie wet toetsing levensbee¨indiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. ZonMw, Den Haag. https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/derde-evaluatie-wet-toetsing-levensbeeindiging-op-verzoek-en-hulp-bij-zelfdoding/ (last accessed on 24 October 2022) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dierickx S, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Penders Y, et al. Commonalities and differences in legal euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in three countries: a population-level comparison. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00038-019-01281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borasio GD, Jox RJ, Gamondi C. Regulation of assisted suicide limits the number of assisted deaths. Lancet. 2019;393:982–983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32554-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernheim JL, Raus K. Euthanasia embedded in palliative care Responses to essentialistic criticisms of the Belgian model of integral end-of-life care. J Med Ethics. 2017;43:489–494. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly B, Handley T, Kissane D, Vamos M, Attia J. An indelible mark The response to participation in euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among doctors: a review of research findings. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18:82–88. doi: 10.1017/S1478951519000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanner H. The effect of assisted dying on suicidality: a synthetic control analysis of population suicide rates in Belgium. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42:86–97. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raus K, Deliens L, Chambaere K. The extension of the Belgian euthanasia law to minors in 2014 International Perspectives on End-of-Life Law Reform: 40-62. Cambridge University Press. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas CD, Kerridge IH, Rainbird KJ, McPhee JR, Hancock L, Spigelman AD. The intention to hasten death: a survey of attitudes and practices of surgeons in Australia. Med J Aust. 2001;175:511–515. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambaere K, Bernheim JL, Downar J, Deliens L. Characteristics of Belgian “life-ending acts without explicit patient request”: a large-scale death certificate survey revisited. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:E262–E267. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rietjens JAC, Bilsen J, Fischer S, et al. Using drugs to end life without an explicit request of the patient. Death Stud. 2007;31:205–221. doi: 10.1080/07481180601152443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lerner BH, Caplan AL. Euthanasia in Belgium and the Netherlands on a slippery slope? J Med Ethics. 2015;41:592–598. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raus K, Vanderhaegen B, Sterckx S. Euthanasia in Belgium: shortcomings of the law and its application and of the monitoring of practice. J Med Philos. 2021;46:80–107. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhaa031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J, van Wesemael Y, Smets T, Bilsen J, Deliens L. Cultural differences affecting euthanasia practice in Belgium: one law but different attitudes and practices in Flanders and Wallonia. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smets T, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Rurup ML, de Keyser E, Deliens L. The medical practice of euthanasia in Belgium and The Netherlands: legal notification, control and evaluation procedures. Health Policy (New York) 2009;90:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dierickx S, Cohen J, vander Stichele R, Deliens L, Chambaere K. Drugs used for euthanasia: a repeated population-based mortality follow-back study in Flanders, Belgium, 1998-2013. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robijn L, Cohen J, Rietjens J, Deliens L, Chambaere K. Trends in continuous deep sedation until death between 2007 and 2013: a repeated nationwide survey. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158188. e0158188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Overbeek A, van de Wetering VE, van Delden JJM, et al. Classification of end-of-life decisions by dutch physicians: findings from a cross-sectional survey. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:3554–3562. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J, Dierickx S, Penders YWH, Deliens L, Chambaere K. How accurately is euthanasia reported on death certificates in a country with legal euthanasia: a population-based study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:689–693. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chambaere K, Bernheim JL. Does legal physician-assisted dying impede development of palliative care? The Belgian and Benelux experience. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:657–660. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J, Chambaere K. Increased legalisation of medical assistance in dying: relationship to palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2022-003573. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2022-003573. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smets T, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Rurup ML, Deliens L. Legal euthanasia in Belgium: characteristics of all reported euthanasia cases. Med Care. 2010;48:187–192. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4dde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Involvement of palliative care in euthanasia practice in a context of legalized euthanasia: a population-based mortality follow-back study. Palliat Med. 2018;32:114–122. doi: 10.1177/0269216317727158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dierickx S, Cohen J. Medical assistance in dying: research directions. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9:370–372. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]