Abstract

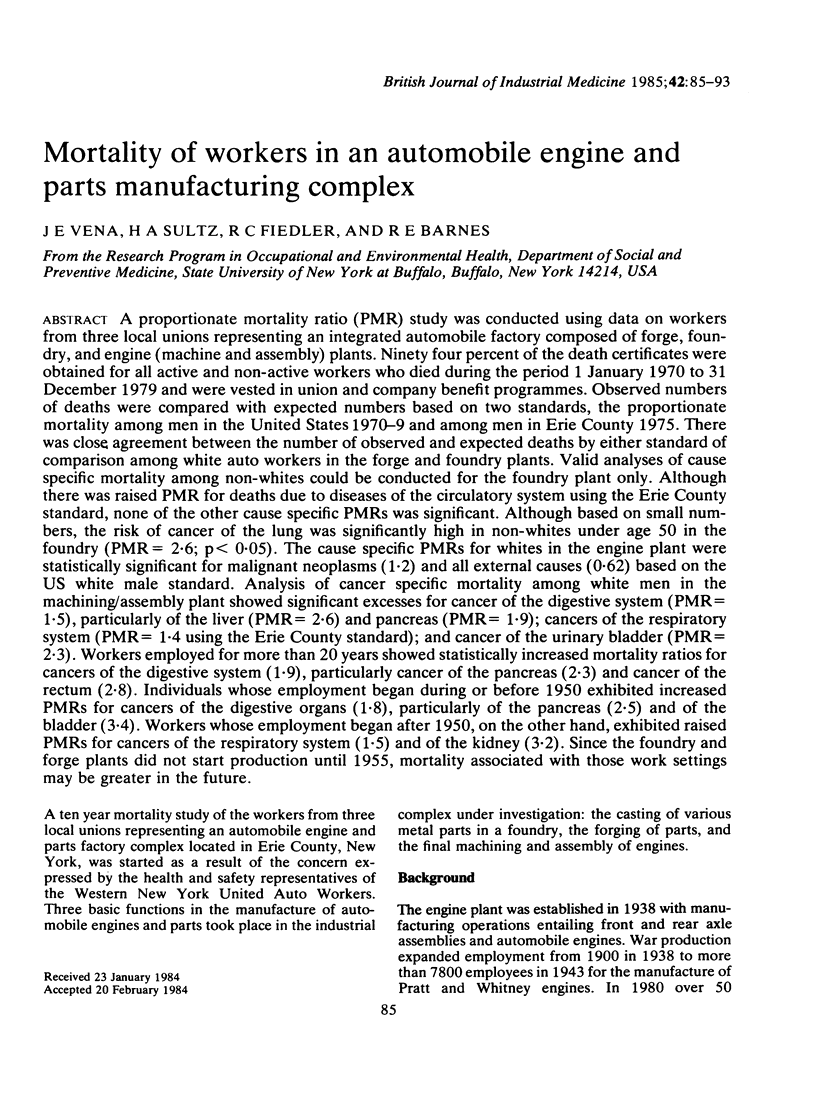

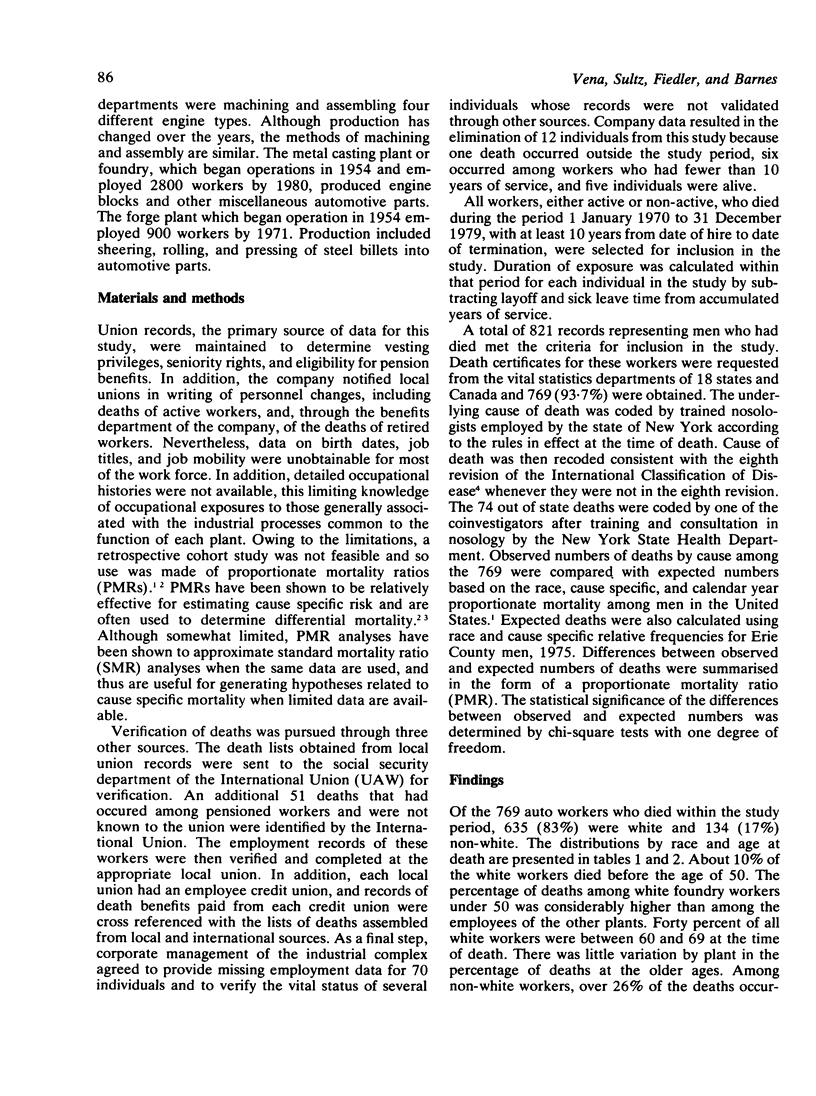

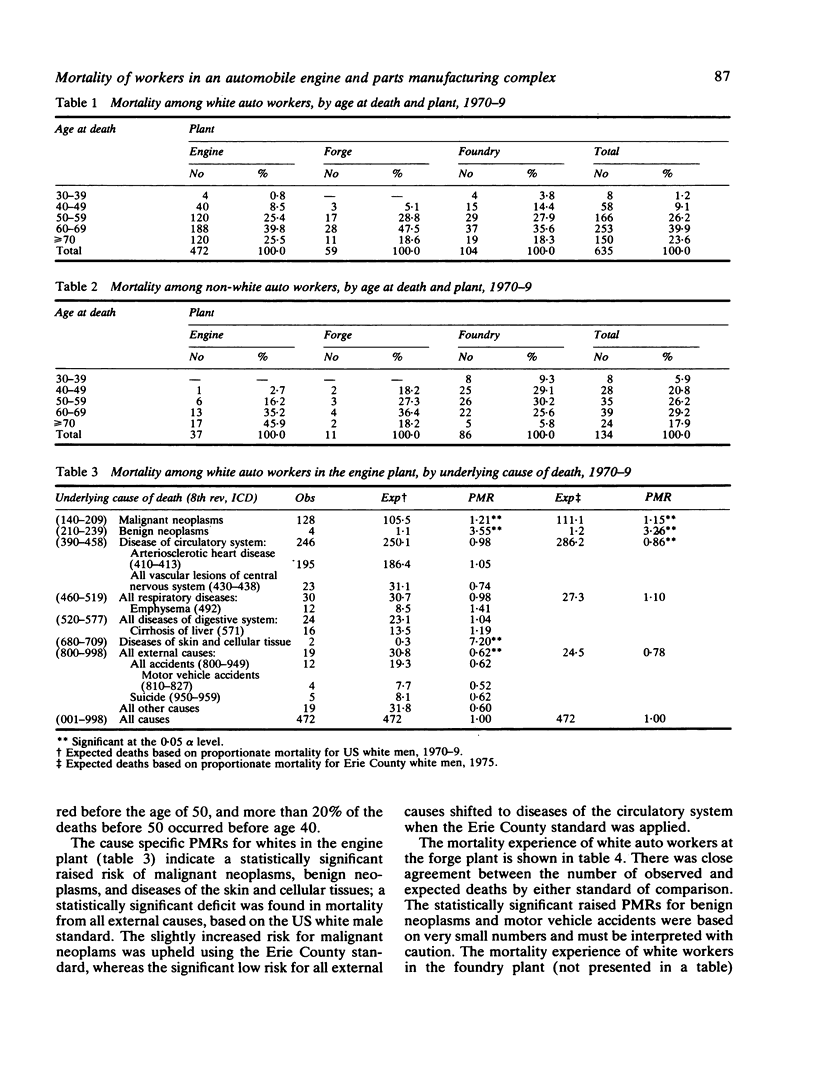

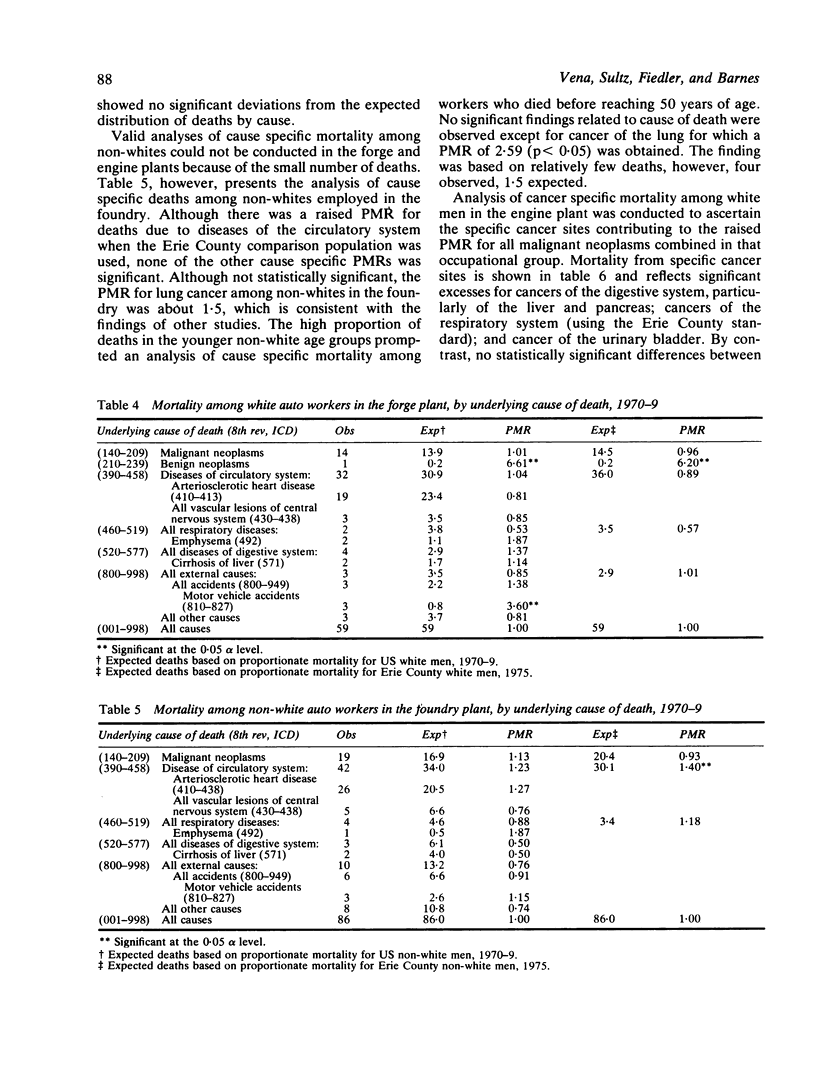

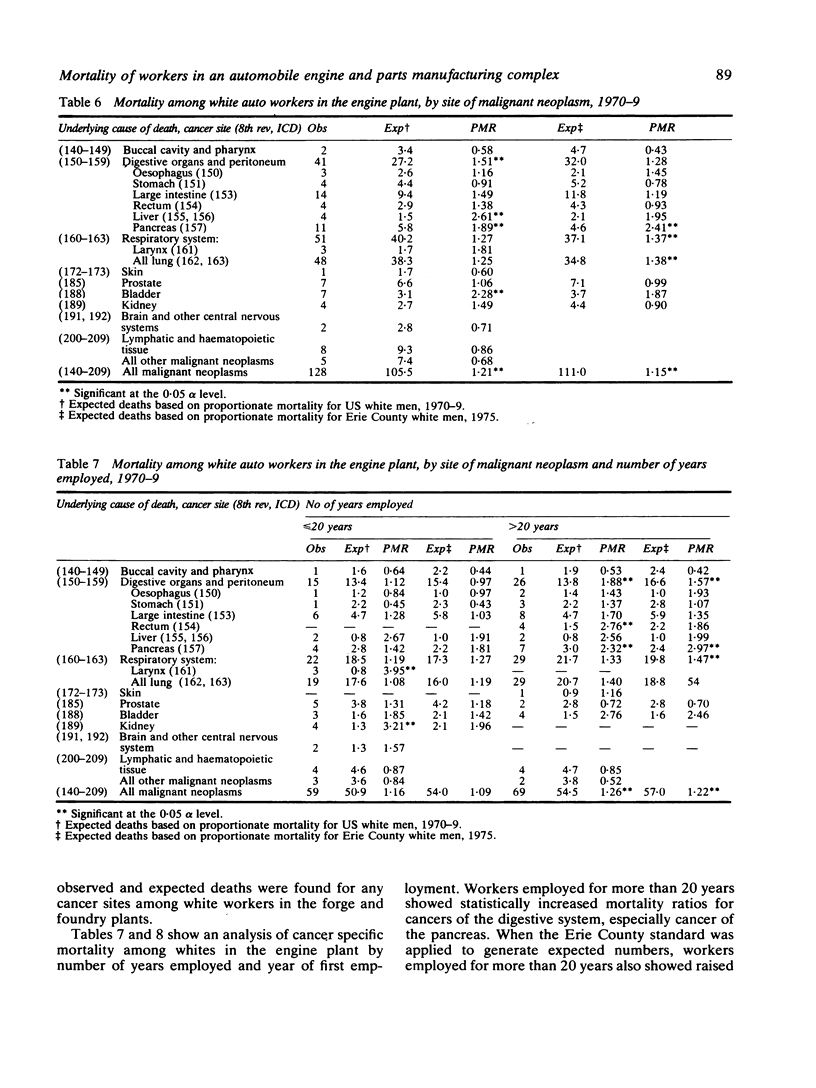

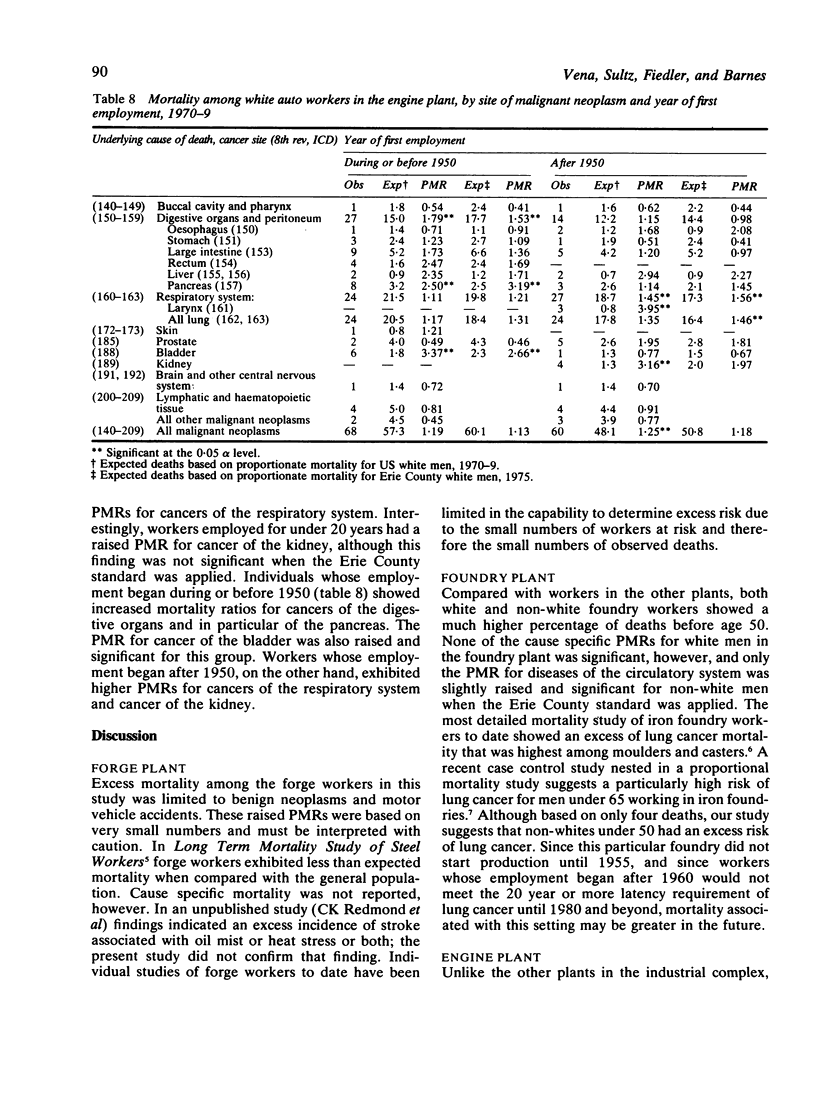

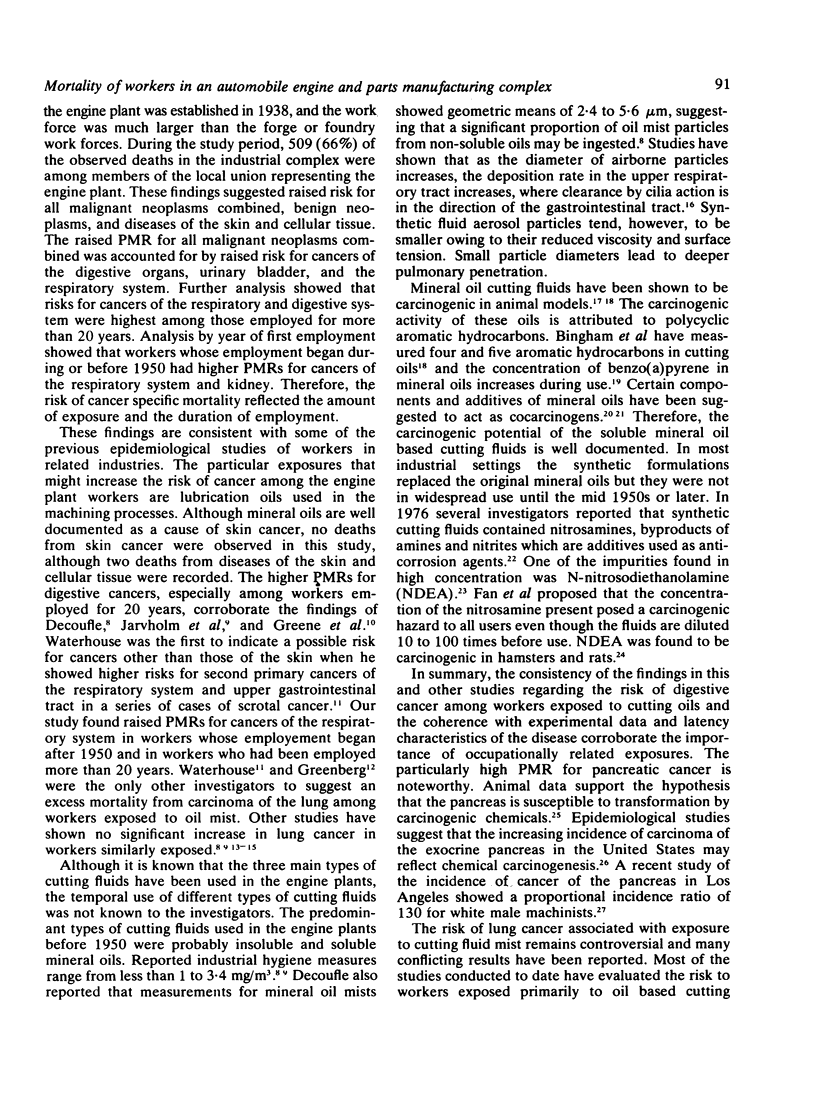

A proportionate mortality ratio (PMR) study was conducted using data on workers from three local unions representing an integrated automobile factory composed of forge, foundry, and engine (machine and assembly) plants. Ninety four percent of the death certificates were obtained for all active and non-active workers who died during the period 1 January 1970 to 31 December 1979 and were vested in union and company benefit programmes. Observed numbers of deaths were compared with expected numbers based on two standards, the proportionate mortality among men in the United States 1970-9 and among men in Erie County 1975. There was close agreement between the number of observed and expected deaths by either standard of comparison among white auto workers in the forge and foundry plants. Valid analyses of cause specific mortality among non-whites could be conducted for the foundry plant only. Although there was raised PMR for deaths due to diseases of the circulatory system using the Erie County standard, none of the other cause specific PMRs was significant. Although based on small numbers, the risk of cancer of the lung was significantly high in non-whites under age 50 in the foundry (PMR = 2.6; p less than 0.05). The cause specific PMRs for whites in the engine plant were statistically significant for malignant neoplasms (1.2) and all external causes (0.62) based on the US white male standard. Analysis of cancer specific mortality among white men in the machining/assembly plant showed significant excesses for cancer of the digestive system (PMR=1.5), particularly of the liver (PMR=2.6) and pancreas (PMR=1.9); cancers of the respiratory system (PMR=1.4 using the Erie County standard); and cancer of the urinary bladder (PMR=2.3). Workers employed for more than 20 years showed statistically increased mortality ratios for cancers of the digestive system (1.9), particularly cancer of the pancreas (2.3) and cancer of the rectum (2.8). Individuals whose employment began during or before 1950 exhibited increased PMRs for cancers of the digestive organs (1.8), particularly of the pancreas (2.5) and of the bladder (3.4). Workers whose employment began after 1950, on the other hand, exhibited raised PMRs for cancers of the respiratory system (1.5) and of the kidney (3.2). Since the foundry and forge plants did not start production until 1955, mortality associated with those work settings may be greater in the future.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BINGHAM E., HORTON A. W., TYE R. THE CARCINOGENIC POTENCY OF CERTAIN OILS. Arch Environ Health. 1965 Mar;10:449–451. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1965.10664027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoufle P. Further analysis of cancer mortality patterns among workers exposed to cutting oil mists. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1978 Oct;61(4):1025–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decouflé P., Thomas T. L., Pickle L. W. Comparison of the proportionate mortality ratio and standardized mortality ratio risk measures. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Mar;111(3):263–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan-Baum E., Miller B. A., Waxweiler R. J. Lung cancer and other mortality patterns among foundrymen. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1981;7 (Suppl 4):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely T. S., Pedley S. F., Hearne F. T., Stille W. T. A study of mortality, symptoms, and respiratory function in humans occupationally exposed to oil mist. J Occup Med. 1970 Jul;12(7):253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. J., Collier P. F. Low mortality rates in industrial cohort studies due to selection for work and survival in the industry. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976 Dec;30(4):225–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.4.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILMAN J. P., VESSELINOVITCH S. D. Cutting oils and squamous-cell carcinoma. II. An experimental study of the carcinogenicity of two types of cutting oils. Br J Ind Med. 1955 Jul;12(3):244–248. doi: 10.1136/oem.12.3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M. A proportional mortality study of a group of newspaper workers. Br J Ind Med. 1972;29(1):15–20. doi: 10.1136/oem.29.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M. H., Hoover R. N., Eck R. L., Fraumeni J. F., Jr Cancer mortality among printing plant workers. Environ Res. 1979 Oct;20(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(79)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfrich J., Schmeltz I., Hoffmann D. Effects of N-nitrosodiethanolamine and 1,1-diethanolhydrazine in Syrian golden hamsters. Cancer Lett. 1978 Jan;4(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(78)93412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton A. W., Bingham E. L., Burton M. J., Tye R. Carcinogenesis of the skin. 3. The contribution of elemental sulfur and of organic sulfur compounds. Cancer Res. 1965 Nov;25(10):1759–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvholm B., Lillienberg L., Sällsten G., Thiringer G., Axelson O. Cancer morbidity among men exposed to oil mist in the metal industry. J Occup Med. 1981 May;23(5):333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski R., Geissert K. S., Dacey E. Mortality analysis of plumbers and pipefitters. J Occup Med. 1980 Mar;22(3):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipling M. D., Waldron H. A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mineral oil, tar, and pitch, excluding petroleum pitch. Prev Med. 1976 Jun;5(2):262–278. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(76)90044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper L. L., McMichael A. J., Symons M. J., Most B. M. On the utility of proportional mortality analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1978 Jan;31(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longnecker D. S. Environmental factors and diseases of the pancreas. Environ Health Perspect. 1977 Oct;20:105–112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7720105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack T. M., Paganini-Hill A. Epidemiology of pancreas cancer in Los Angeles. Cancer. 1981 Mar 15;47(6 Suppl):1474–1484. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810315)47:6+<1474::aid-cncr2820471406>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson R. R. Analysis of relative survival and proportional mortality. Comput Biomed Res. 1974 Aug;7(4):325–332. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(74)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternack B., Ehrlich L. Occupational exposure to an oil mist atmosphere. A 12-year mortality study. Arch Environ Health. 1972 Oct;25(4):286–294. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1972.10666175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C. K., Breslin P. P. Comparison of methods for assessing occupational hazards. J Occup Med. 1975 May;17(5):313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tola S., Koskela R. S., Hernberg S., Järvinen E. Lung cancer mortality among iron foundry workers. J Occup Med. 1979 Nov;21(11):753–759. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197911000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley P. V., 3rd, Pinsky S. D. Binding of N-nitroso carcinogens in pancreatic tissue. Cancer. 1981 Mar 15;47(6 Suppl):1485–1489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810315)47:6+<1485::aid-cncr2820471408>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]