Abstract

Melanoma is the most aggressive and malignant form of skin cancer. Current melanoma treatment methods generally suffer from frequent drug administration as well as difficulty in direct monitoring of drug release. Here, a self-monitoring microneedle (MN)-based drug delivery system, which integrates a dissolving MN patch with aggregation-induced emission (AIE)-active PATC microparticles, is designed to achieve light-controlled pulsatile chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy of melanoma. The PATC polymeric particles, termed D/I@PATC, encapsulate both of chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (DOX) and the photothermal agent indocyanine green (ICG). Upon light illumination, PATC gradually dissociates into smaller particles, causing the release of encapsulated DOX and subsequent fluorescence intensity change of PATC particles, thereby not only enabling direct observation of the drug release process under light stimuli, but also facilitating verification of drug release by fluorescence recovery after light trigger. Moreover, encapsulation of ICG in PATC particles displays significant improvement of its photothermal stability both in vitro and in vivo. In a tumor-bearing mouse, the application of one D/I@PATC MN patch combining with two cycles of light irradiation showed excellent controllable chemo-photothermal efficacy and exhibited ∼97% melanoma inhibition rate without inducing any evident systemic toxicity, suggesting a great potential for skin cancer treatment in clinics.

Keywords: Microneedle, Controlled release, Melanoma, AIE, Photothermal therapy, Chemotherapy

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A self-monitoring MN patch is developed to enable direct visualizing of drug release.

-

•

A dissolvable MN patch achieves light-controlled chemo-photothermal therapy of melanoma by using AIE-active polymers.

-

•

AIE-active PATC particles can enhance the ICG reliability and stability both in vitro and in vivo.

1. Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer in humans, while malignant melanoma is the most aggressive and treatment-resistant skin cancer [1,2]. Melanoma accounts for about 1% of skin cancer cases but is responsible for the majority of skin cancer deaths [3,4]. Although surgical resection is one of the most common methods for melanoma treatment, there are still some disadvantages related with this therapy, such as difficulty in completely examining the resection margin, high risk of local recurrence, as well as poor patient compliance associated with the invasive surgical procedure [5]. Chemotherapy, a classic cancer treatment strategy, is not satisfactory for malignant melanoma treatment and usually induces multi-organ toxicity due to systemic administration [6,7]. Over the past years, external micro-energy has emerged as potential therapeutic modalities for anti-tumor activities, such as phototherapy [[8], [9], [10]], ultrasound therapy [[11], [12], [13]], and magnetic response therapy [14,15]. Among them, phototherapy, which includes photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT), has attracted considerable interest owning to the unique properties, such as noninvasiveness, high spatiotemporal resolution, great selectivity, and low toxicity [[16], [17], [18]]. Whereas, due to the complex and changeable tumor microenvironment, it is difficult to inhibit tumor development by a single therapy [19]. The combination of chemotherapy and phototherapy has been proved to possess great synergetic therapeutic effects that can achieve tumor eradication with a low dosage of drug [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. However, the combined systems for skin tumor treatment still face some challenges, either requiring multiple administration of chemical drug, or lacking satisfactory resolution to precisely control drug release, or difficult to directly monitor the release behavior of drug carriers. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore a new strategy that not only has great efficacy to treat melanoma with a single dose by accurate and pulsatile delivery of anti-cancer drugs coupling with photothermal effect, but also enables direct visualization and verification of drug release from the delivery system.

MN is a new type of minimally invasive transdermal drug delivery system that can pierce below the skin surface and achieve bolus or sustained release of drugs in skin without damaging blood vessels or touching nerve endings, thereby causing no pain and significantly increasing patient compliance [[24], [25], [26], [27]]. By using MNs, various kinds of drugs, ranging from small chemicals to biological macromolecules, have been successfully delivered in skin, either for local therapy or for systemic treatment [[28], [29], [30]].

Herein, by taking advantage of the beneficial properties of MNs, we developed a self-monitoring MN-based pulsatile drug release system based on visualized phase-transition polymer for real-time monitoring of drug release and chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy of melanoma. The polymer, termed Poly-AM-TPE-CAA (PATC), is biocompatible and thermal-responsive [31], and can aggregate with strong fluorescence under cool condition, while dissociating into smaller particles with decreased fluorescence at high temperature (Fig. 1a), which makes it suitable for direct fluorescence monitoring of the phase transition process during drug release and verification of drug release after thermal trigger. To demonstrate the efficient anti-melanoma efficacy as well as the admirable AIE property of the MN-based drug delivery system, two model drugs, including the chemotherapeutic drug, DOX, and the photothermal agent, ICG, were co-encapsulated in PATC polymers to obtain D/I@PATC microparticles, and these microparticles were subsequently concentrated at the MN tips to form a D/I@PATC MN patch with improved delivery efficiency (Fig. 1b). The D/I@PATC MN patch developed in this study, which integrated the beneficial properties of MNs with AIE-active microparticles, not only enabled the visualization and verification of drug release from MNs, but also facilitated the improvement of photothermal stability and reliability both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro studies showed that D/I@PATC microparticles had excellent light-controlled drug release ability and a strong antitumor effect at low doses. In vivo anticancer experiment demonstrated that a single administration of D/I@PATC MN patch could achieve spatiotemporally controlled chemo-photothermal therapy and almost completely inhibit tumor growth, without causing any evident systemic toxicity (Fig. 1c). These encouraging results of D/I@PATC MN patches raise the possibility of a new strategy for melanoma treatment in clinics.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the D/I@PATC MN patch for melanoma therapy. a) Preparation of D/I@PATC polymeric particles and laser-triggered visualized drug release. b) The fabrication process of D/I@PATC MN patches. c) Schematic illustration of D/I@PATC MN patches for laser-triggered chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy of melanoma.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Fabrication and characterization of D/I@PATC particles

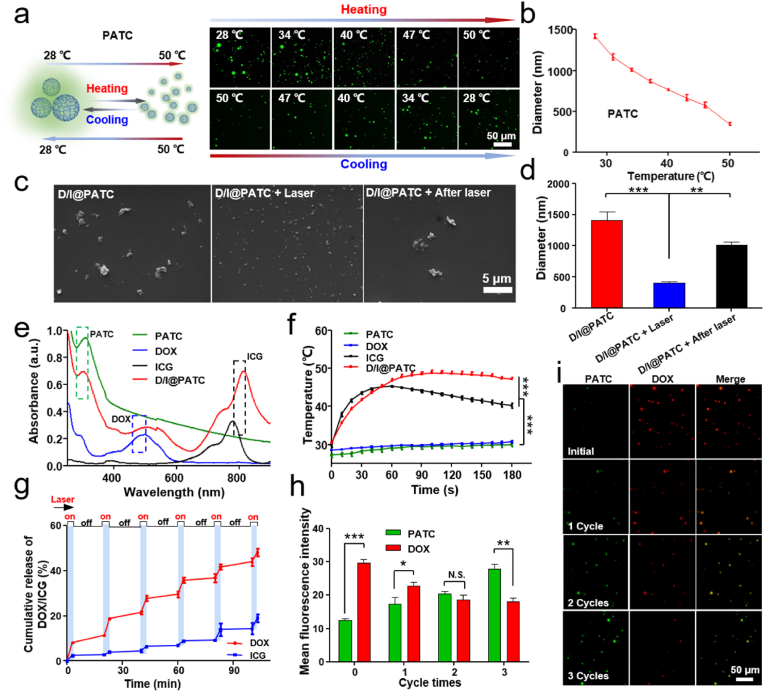

The PATC microparticles were prepared according to the reversible addition and fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) copolymerization method as previously described [32]. As the temperature raised above the critical point, the fluorescence intensity of PATC polymer gradually decreased due to its dissociation (Fig. 2a), and the average hydrodynamic diameter of D/I@PATC reduced from 1416 ± 50 nm to 344 ± 31 nm with temperature increasing from 28 °C to 50 °C (Fig. 2b). Such phase transition process of PATC polymer was reversible, and the polymer would reassemble again when they cooled down, resulting in the fluorescence intensity recovery of the PATC polymeric particles (Fig. 2a). The aqueous PATC suspension underwent insoluble-to-soluble transition when heating from 28 °C to 50 °C, and went back to the insoluble status after cooling down (Fig. S1), further demonstrating the reversible transition property of the PATC microparticles. The encapsulation of DOX and ICG in PATC polymer via hydrophobic interaction endowed the polymeric microparticles (i.e., D/I@PATC) with the property of light sensitivity. Upon 808 nm light irradiation, the encapsulated ICG gradually absorbed light and converted light energy to heat, inducing the dissociation of D/I@PATC particles. After switching off light, D/I@PATC particles got cooling and aggregated to big particles again. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images exhibited that the size of D/I@PATC polymer changed from 1408 ± 239 nm–407 nm ± 35 nm under 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2) irradiation for 3 min, and returned to 1012 ± 90 nm with particles aggregation after turning off the laser (Fig. 2c and d). In addition, the D/I@PATC particles remained very stable when incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at 37 °C for up to 72 h, indicating that the particles possessed great stability (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of visualized phase-transition of D/I@PATC particles. a) Schematic and CLSM images of the reversible visualized phase transition process of AIE-active PATC microparticles. b) Hydrodynamic diameters of PATC suspension at different temperatures. c) SEM images and d) related diameter quantification of D/I@PATC with or without laser irradiation. e) UV–vis absorption spectra of PATC, DOX, ICG, and D/I@PATC. Green, blue and black dashed boxes indicate characteristic peaks of PATC, DOX and ICG, respectively. f) Photothermal effect of D/I@PATC particles under 808 nm irradiation (0.5 W/cm2) with PATC, DOX and ICG as control samples. g) Cumulative DOX and ICG release in vitro from D/I@PATC in PBS solution under 808 nm laser on (3 min)/off (17 min) cycles irradiation (0.5 W/cm2). i) Representative fluorescence images and h) corresponding quantitative fluorescence intensity of D/I@PATC particles before and after repeated 808 nm laser “on/off” cycles irradiation (3 min, 0.5 W/cm2). Green fluorescence: PATC; red fluorescence: DOX. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. N.S. indicates no significance.

To investigate whether both of DOX and ICG were successfully encapsulated inside PATC polymers, ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy was performed to analyze the particles. The UV–vis absorption spectra exhibited obvious absorption peaks of PATC (∼300 nm), DOX (∼500 nm) and ICG (∼800 nm), which indicated the co-existence of PATC, DOX and ICG in the polymeric particles (Fig. 2e). Then, the encapsulation efficiency (EE) and drug loading capacity (DLC) of DOX and ICG inside particles were also determined by UV–vis absorption spectra, which was 50.3%, 47.6% for EE, and 9.6%, 3.6% for DLC, respectively (Fig. S3). When preparing the D/I@PATC particles, the EE and DLC of DOX or ICG were accurately controlled by precisely controlling the synthesis conditions, such as the loading ratio and reaction time of DOX/ICG and PATC.

2.2. In vitro photothermal effect and controlled release from D/I@PATC

D/I@PATC microparticles possessed chemo-photothermal effects, due to the increase of temperature during light illumination and the release of DOX during phase transition of particles. The photothermal effect of D/I@PATC particles was assessed by a thermal imaging instrument. The temperature of the D/I@PATC aqueous suspension (100 μg/mL) steadily increased from 30.3 ± 1.1 °C to 47.1 ± 0.8 °C within 180 s under 808 nm laser irradiation (Fig. 2f), with a photothermal conversion efficiency of 17.2% (Fig. S4), and such photothermal effect of D/I@PATC aqueous dispersion was in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S5). In comparison, the temperature of equivalent free ICG rapidly increased to 46.7 ± 1.0 °C within 60 s but started to decrease to 40.2 ± 1.0 °C due to its poor photostability, and the PATC suspension and DOX solution only gave a temperature increase of less than 3 °C. These results showed that the prepared D/I@PATC had better photothermal stability than free ICG. By taking advantage of such photothermal effect, the D/I@PATC particles could achieve controlled release of DOX by using alternate light on (3 min) and off (17 min) cycles. A burst DOX release from D/I@PATC particles was observed during the first cycle of laser irradiation, and there was almost no DOX release after switching off the laser, demonstrating the feasibility of controlled release of DOX from PATC particles using remote light. After 2 irradiation cycles, the cumulative release of DOX reached 21.4 ± 1.5% and approximately half amount of DOX could be delivered after 6 irradiation cycles (Fig. 2g). The release rate of ICG was much slower than that of DOX during the photothermal heating, which was probably ascribed to the interaction between ICG and PATC polymers as well as the consumption during light irradiation [33,34].

Notably, the phase transition process of D/I@PATC for controlled DOX release can be directly monitored by fluorescence change. PATC has been proven to have fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) with DOX [32]. Due to the FRET effect between PATC and DOX, strong red fluorescence was observed when temperature of D/I@PATC particles was below the upper critical solution temperature (UCST) (Fig. 2i). After using repeated laser on (3 min) and off (17 min) cycles, the red fluorescence intensity of D/I@PATC was decreased, while the green fluorescence intensity was enhanced, which was ascribed to DOX release and polymeric particles re-aggregation (Fig. 2h and i).

2.3. In vitro cellular uptake and intracellular drug release

To investigate cellular uptake of the released DOX by melanoma cells after NIR light trigger, D/I@PATC particles were cocultured with B16–F10 cells for 8 h. Compared with untreated cells, B16–F10 cells that cultured with D/I@PATC particles showed strong red fluorescence in the nuclei after 808 nm laser irradiation (0.5 W/cm2) for 3 min (Fig. 3a), which was ∼3.2 times higher than that in cells cultured with D/I@PATC particles but without light irradiation (Fig. 3b), demonstrating the controlled release of DOX from D/I@PATC particles and subsequent uptake by melanoma cells.

Fig. 3.

Cellular uptake of DOX released from D/I@PATC and the chemo-photothermal effects on cells in vitro. a) B16–F10 cellular uptake of DOX after incubation with D/I@PATC for 8 h without or with 808 nm laser irradiation (0.5 W/cm2, 3 min). b) Corresponding quantitative red fluorescence intensity of B16–F10 cells with different treatments. c) Cell viability of B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cells after incubation with ICG and PATC of various concentrations for 24 h. d) Cell viability of B16–F10 cells treated with DOX, D/I@PATC, I@PATC with laser and D/I@PATC with laser. These four treatments had equivalent DOX concentration. e) Live/dead assay of B16–F10 cells incubation with various samples with equivalent drugs concentration (100 μg/mL). Green fluorescence: calcein-AM; red fluorescence: propidium iodide (PI). Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. N.S. indicates no significance.

2.4. In vitro cytotoxicity and anti-tumor efficacy

The cytotoxicity was next studied on B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cells by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The viability of B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cells were greater than 90% after 24 h incubation with different concentrations of ICG or PATC under dark conditions, indicating the superior biocompatibility of ICG and unloaded PATC particles (Fig. 3c). The hemolysis assay further demonstrated the satisfactory biocompatibility and biosafety of the PATC microparticles (Fig. S6). In contrast, the groups of DOX, D/I@PATC and D/I@PATC with laser displayed cytotoxicity in a concentration-dependent manner. Free DOX exhibited high cytotoxicity with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 9.1 ± 0.9 μg/mL, while D/I@PATC showed a significant decrease in cytotoxicity with a IC50 of 76.0 ± 7.3 μg/mL when there was no light irradiation (Fig. 3d), revealing that the cytotoxicity of DOX was significantly inhibited after being loaded into PATC, which is supposed to reduce side effects of the drug delivery system. However, under laser irradiation, DOX was explosively released from D/I@PATC particles, and the D/I@PATC system presented very effective anti-tumor activity by the combination of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy (Fig. 3d and e), suggesting excellent anti-cancer efficacy of D/I@PATC particles in vitro. There was certain cytotoxicity of D/I@PATC without laser irradiation, which might be ascribed to the diffusion of a little DOX from the microparticles (Fig. 3e). Although a lot of tumor cells were killed after being treated with I@PATC combined with laser irradiation, such treatment still displayed less cytotoxicity compared with the application of D/I@PATC with laser light (Fig. 3e), further demonstrating the superior anticancer capability of D/I@PATC to that of single chemotherapy or photothermal therapy.

2.5. Fabrication and characterization of D/I@PATC MN patches

After fabrication and characterization of D/I@PATC microparticles, we next loaded these particles in MN patches. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and sucrose were selected as the structural polymer materials of MNs due to their outstanding biocompatibility and solubility. D/I@PATC particles were loaded in MN tips by multiple centrifugation to finally obtain D/I@PATC MN patches (Fig. 4a). The D/I@PATC MN patch contained 100 needles with a center-to-center interval of 700 μm in a 0.7 × 0.7 cm2 area. The SEM image showed that the morphology of the MN was in a conical shape, with 400 μm in diameter at the base and 850 μm in height (Fig. 4b). The fabricated D/I@PATC MN patch possessed enough mechanical strength (Fig. 4e), and could puncture rat skin ex vivo (Fig. 4c), achieving efficient transdermal delivery of D/I@PATC particles (Fig. 4d). D/I@PATC particles were mainly concentrated in the front of MN tips, so most D/I@PATC particles could be delivered after the application of MN patch to skin, with the drug delivery efficiency of 84.1 ± 12.1% (Fig. S7).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of D/I@PATC MN patches. a) Representative optical microscopy images of a D/I@PATC MN patch before (left and top right) and after (bottom right) insertion into the skin. D/I@PATC particles concentrated in the front of MN tips. b) SEM images of D/I@PATC MN array. c) Representative bright-field microscopy image of rat skin after MN patch insertion ex vivo. d) Representative image of a histological section of rat skin after MN patch insertion imaged by bright-field microscopy. Blue arrowheads indicate the delivered D/I@PATC particles under skin. e) Mechanical behavior of the D/I@PATC MN patch. f) Temperature change profiles and g) corresponding stereoscopic photomicrographs/thermal images of the blank MN patch, DOX MN patch, ICG MN patch and D/I@PATC MN patch under 808 nm laser irradiation (0.5 W/cm2). Time-temperature curves of h) ICG MN patch and i) D/I@PATC MN patch under 5 repeated laser “on/off” cycles irradiation. j) Fluorescence images of D/I@PATC MNs after insertion into an agar gel and irradiation with repeated laser light. k) Fluorescence intensity change of the D/I@PATC MNs in the gel after light irradiation. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3). ***p < 0.001.

To evaluate the photothermal effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in vitro, MN patches were irradiated under 808 nm laser. Temperature of D/I@PATC MN patch and ICG MN patch rapidly increased from about 25 °C to over 55 °C after laser exposure (0.5 W/cm2) for 3 min, compared to the negligible temperature increment in blank MN patch or DOX MN patch, indicating satisfactory photothermal effect of MN patches when encapsulating ICG (Fig. 4f and g). We further used repeated light cycles to irradiate D/I@PATC MN patch and ICG MN patch, respectively. The maximum temperature of ICG MN patch gradually decreased during cycled light irradiation (Fig. 4h), while the highest temperature of D/I@PATC MN patch remained very stable (Fig. 4i), suggesting that D/I@PATC MN patch had more reliable and stable photothermal performance than ICG MN patch, due largely to the good encapsulation and protection of ICG inside the PATC microparticles. To investigate the self-monitoring property of the D/I@PATC MN patch, the patch was inserted into an agar gel in vitro and irradiated with repeated laser light for the release of drug. As shown in Fig. 4j and k, MNs displayed gradual fluorescence increase in the gel after the light-triggered release of encapsulated DOX, due to the AIE property and the FRET effect, which would be helpful for the monitoring of drug release from MNs.

2.6. Distribution of D/I@PATC particles after MN patch application in vivo

Next, we assessed the distribution of D/I@PATC particles after MN patch application in tumor mice. B16–F10 tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into three groups and administered with: (1) D/I@PATC MN patches; (2) blank MN patches; or (3) D/I@PATC particles via intravenous (I·V.) injection (Fig. 5a). Mice treated with D/I@PATC MN patches exhibited strong fluorescence intensity at the tumor site that lasted for 24 h (Fig. 5a and b). In contrast, in the mice that received D/I@PATC particles via I.V. injection, apparent fluorescence signal was only observed in the liver and spleen instead of tumor (Fig. 5a). This result indicated that the application of D/I@PATC MN patches could achieve increased accumulation of D/I@PATC particles in the tumor and cause decreased systemic toxicity during melanoma treatment. Major organs (tumor, heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) were collected 24 h post-treatments (Fig. 5a), and the result of these isolated organs fluorescence intensity further confirmed the above conclusion (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Biodistribution and photothermal effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in B16–F10 melanoma mice. a) Near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence images of mice and major organs 24 h post administration with different treatments. White dashed circles indicate tumor sites. NIR signal intensity of b) tumors and c) major organs post administration of mice. ROI indicates the region of interest. d) Photothermal images of blank MN patch, ICG MN patch or D/I@PATC MN patch treated mice under 808 nm laser irradiation (0.5 W/cm2) and e) corresponding time-temperature curves of the tumor site. Time-temperature curves of the tumor site under 808 nm laser irradiation immediately and 24 h after the application of D/I@PATC MN patch f) or ICG MN patch g). h) The time-temperature curve of tumor site treated with D/I@PATC MN patch under 5 repeated laser “on/off” cycles irradiation. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3). ***p < 0.001. N.S. indicates no significance.

2.7. Photothermal effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo

We next investigated the photothermal effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in B16–F10 tumor-bearing mice. Under 808 nm light irradiation for 3 min, the local tumor temperature of mice treated with D/I@PATC MN patches or ICG MN patches was increased from 26.4 ± 1.3 °C to 49.8 ± 0.6 °C or from 29.5 ± 0.89 °C to 50.2 ± 1.2 °C respectively, while the temperature at tumor site only increased from 24.7 ± 2.2 °C to 35.5 ± 2.2 °C in mice that received blank MN patches (Fig. 5d and e), which suggested satisfactory photothermal effect of D/I@PATC MN and ICG MN patches in vivo. However, 24 h post MN patches application, the tumor temperature of mice receiving D/I@PATC MN patch could still reach 47.7 ± 0.56 °C under 808 nm laser irradiation for 3 min, but the tumor temperature of mice treated with ICG MN patch could only rise to 39.4 ± 1.8 °C, suggesting that the D/I@PATC MN patch had stronger PTT stability and longer tumor retention time (Fig. 5f and g). Such improved stability and reliability were further validated by the incubation of ICG MN patches or D/I@PATC MN patches in PBS solution at 37 °C for 24 h, which displayed much less decomposition of ICG in D/I@PATC MN patches than that in ICG MN patches (Fig. S8). Importantly, consistent with the in vitro result (Fig. 4i), D/I@PATC particles delivered by MN patches maintained very stable photothermal property in vivo during repeated laser irradiation cycles (Fig. 5h), showing reliable photothermal efficiency.

2.8. Monitoring of drug release from D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo

Beneficial from the AIE property of PATC polymer, light-controlled release of drug from D/I@PATC MN patches can be directly monitored in vivo by visualization and verification of fluorescence changes. After application of the D/I@PATC MN patch in B16–F10 tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6c), a weak green fluorescence (i.e., PATC) and strong red fluorescence (i.e., DOX) could be clearly observed in vivo at initial time due to the FRET effect. However, with the use of repeated cycles of 808 nm light irradiation, the green fluorescence gradually enhanced and red fluorescence steadily decreased, owing to the controlled-release of DOX from D/I@PATC particles triggered by light cycles (Fig. 6a, d); In contrast, there was no obvious dynamic fluorescence changes in the mice group that were treated with D/I@PATC MN patches but didn't receive light illumination (Fig. 6b, e), demonstrating the excellent capability of monitoring drug release from D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Monitoring of drug release from D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo. a) Representative fluorescence images and d) corresponding quantitative fluorescence intensity of PATC particles and DOX at tumor site before and after repeated 808 nm laser “on/off” cycles irradiation (0.5 W/cm2) post administration of D/I@PATC MN patches. b) Representative fluorescence images and e) corresponding quantitative fluorescence intensity of PATC particles and DOX at tumor site without laser irradiation post administration of D/I@PATC MN patches. c) Representative bright-filed image of a tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mouse and the enlarged view of tumor skin after insertion of a D/I@PATC MN patch. Red arrowheads indicate the penetration holes created by MNs at the tumor site skin. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. N.S. indicates no significance.

2.9. Anti-melanoma effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo

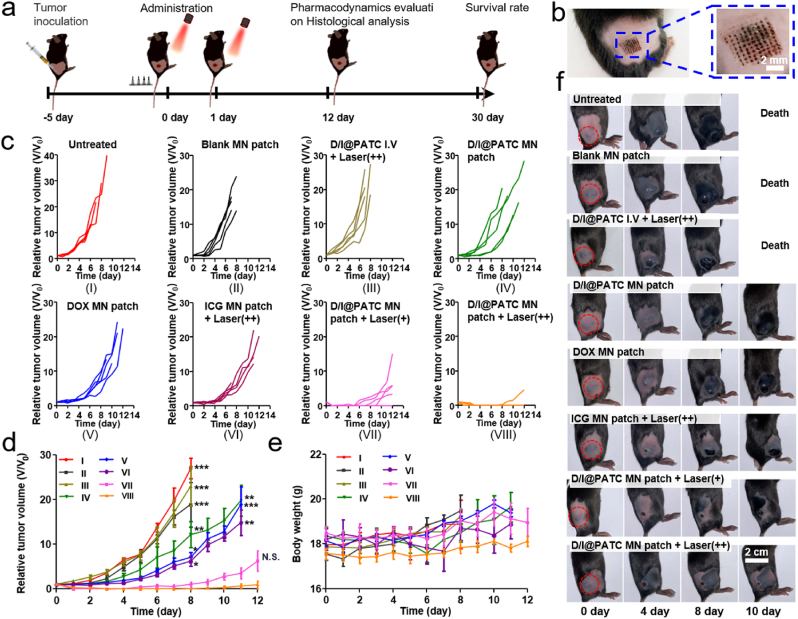

To investigate anti-melanoma effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo, B16–F10 tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into 8 groups, and received: (I) no treatment; (II) blank MN patches; (III) D/I@PATC particles via I.V. injection and laser irradiation for two cycles; (IV) D/I@PATC MN patches; (V) DOX MN patches; (VI) ICG MN patches with laser irradiation for two cycles; (VII) D/I@PATC MN patches with laser irradiation for only one cycle; or (VIII) D/I@PATC MN patches with laser irradiation for two cycles. For laser irradiation, 808 nm laser was applied to the tumor site 1 h post administration with the intensity of 0.5 W/cm2 for 3 min, and the distance between laser tip and tumor was about 15 mm. Mice received the treatments 5 days after tumor inoculation (Fig. 7a). D/I@PATC MN patches showed efficient penetration efficiency in mice (Fig. 7b), and the treatment of D/I@PATC MN patches with 1 cycle light irradiation presented a delay of tumor growth. In contrast, combination of D/I@PATC MN patch with 2 cycles of light irradiation showed noticeable tumor inhibition effects (Fig. 7c, d, f), without significant changes in body weight (Fig. 7e). The particles dosage in the D/I@PATC MN patch was determined as over 300 μg per patch for efficient anti-tumor effect (Fig. S9). Treatments of (II) to (VI) showed similar effects and were not superior to untreated control (Fig. 7c, d, f). When there was no application of D/I@PATC MN patches and only light irradiation was used in melanoma mice, there was no significant difference of tumor volume or tumor weight between the laser irradiation group with the untreated group (Fig. S10), further demonstrating the effective anti-melanoma efficacy of the combination of D/I@PATC MN patches with light illumination. The tumor sizes in mice had close correlation with their survival (Fig. 8c). Sixty percent of mice survived at least 30 days after treatment with D/I@PATC MN patch combined with two light irradiation cycles. In contrast, none of the mice survived in any of the groups (I) to (VI) after 15 days (Fig. 8c). Tumor tissues were excised from mice on the 12th day (Fig. 8a), and the tumor weight result validated the melanoma inhibition effects of the D/I@PATC MN patch when combing with light illumination (Fig. 8b). Furthermore, histological analysis including hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining confirmed the superior therapeutic effect of D/I@PATC MN patches in tumor cell apoptosis induction when combing with light illumination (Fig. 8d and e). Collectively, these results demonstrated that the chemo-photothermal therapy posed by the D/I@PATC MN patches had satisfactory efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth without obvious toxicity.

Fig. 7.

Antitumor activity of D/I@PATC MN patches in B16–F10 melanoma mice. a) Schematic diagram of the treatment process. b) Representative images of tumor site in a C57BL/6 mouse after insertion of a D/I@PATC MN patch. c) Individual and d) average tumor growth curves in 8 various treated groups. e) Body weight curves and f) tumor growth kinetics photographs of mice after different treatments as indicated. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. N.S. indicates no significance.

Fig. 8.

Antitumor efficacy evaluation of D/I@PATC MN patches in B16–F10 melanoma mice. a) Morphology of ex vivo tumors of these 8 groups on the 12th day. The red dashed circles stand for eliminated tumors. b) Tumor weights (red) and tumor inhibition ratios (blue) for mice in each treatment group. c) Survival rate curves of mice in each treatment group. d) TUNEL and e) H&E staining analysis of tumor histological sections in each group. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

2.10. Biosafety of D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo

Biosafety of D/I@PATC MN patches was further assessed in animals. After application of D/I@PATC MN patches and light irradiation in mice, there were some red puncture spots at the skin site, but the mice skin gradually recovered 5 days post administration (Fig. 9a). We performed H&E staining of mice skin that received blank MN patches, D/I@PATC MN patches, D/I@PATC MN patches with 2 cycles of light irradiation or no treatment. The staining result showed that there was no significant difference in the thickness of the skin epidermis among the 4 groups, indicating no skin damage during these treatments (Fig. 9b and c). In addition, histological analysis of major organs by H&E staining displayed no evident inflammatory or damage in the organs 12 days after treating melanoma mice with D/I@PATC MN patches and laser irradiation (Fig. S11), demonstrating great biosafety of D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo. Moreover, the level of ALT (alanine aminotransferase), AST (aspartate aminotransferase), BUN (blood urea nitrogen), and CR (creatinine) were measured for evaluating liver and kidney functions after application of D/I@PATC MN patches. The liver and kidney of mice that were treated with D/I@PATC MN patches and laser illumination did not show any abnormality compared with those of mice that received D/I@PATC MN patches only, or blank MN patches or no treatment (Fig. S12), further suggesting satisfactory biosafety of D/I@PATC MN patches for cancer treatment in vivo.

Fig. 9.

The biosafety evaluation of D/I@PATC MN patches in C57BL/6 mice. a) Skin recovery at administration sites (red dashed boxes) of healthy C57BL/6 mice with the treatments of a blank MN patch, a D/I@PATC MN patch or a D/I@PATC MN patch combined with laser irradiation. b) H&E staining and c) epidermal thickness of the skin in healthy C57BL/6 mice after receiving different treatments. Each point represents mean ± SD (n = 3), and N.S. indicates no significance.

3. Conclusion

In this study, we developed a self-monitoring D/I@PATC MN patch to enable direct monitoring of drug release by fluorescence change and achieve light-controlled chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy of melanoma. D/I@PATC microparticles possessed superior AIE property, which not only promoted direct fluorescence observation of the phase transition process during light trigger, but also facilitated verification of drug release by fluorescence recovery after light stimuli. In addition, the photothermal agent ICG showed more stability after encapsulation in the PATC polymeric particles and displayed reliable responsiveness to remote laser both in vitro and in vivo. In B16–F10 tumor-bearing mice, D/I@PATC MN patches displayed rapid and efficient delivery of D/I@PATC particles at the tumor site after skin insertion, and exhibited adequate chemo-photothermal effect on the tumor elimination without causing any systemic toxicity, demonstrating excellent efficacy of anti-tumor and satisfactory biosafety in vivo. These encouraging results indicate that the D/I@PATC MN patch holds a promising potential for skin cancer treatment in clinics.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Materials

All reagents were analytical grade and were purchased from commercial companies without further purification. ICG was provided by Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Japan). DOX hydrochloride was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich Company, and sucrose was purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was purchased from Dow Corning (Michigan, USA). DPBF was provided by Energy Chemical (Shanghai, China). 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Calcein-AM/PI double stain kit and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). All cell lines used in this project were from Procell Life Science&Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Cell cultures RPMI-1640 and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Wuhan Kerui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. PATC was synthesized according to the reported procedure.

4.2. Thermal-triggered phase transition of PATC

The PATC suspensions were incubated at different temperatures on a live cell workstation. The temperature of the live cell workstation was set from 28 °C to 50 °C, and the temperature was maintained for 5 min after every 3 °C of temperature increase, and the fluorescence changes of PATC were collected by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (A1+, NIKON, Japan) (λex = 405 nm, λem = 430–530 nm). The size changes of PATC after incubation at 28 °C–50 °C were detected by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Zeta-sizer Nano, Malvern Instrument, Britain).

4.3. Laser-triggered phase transition of D/I@PATC

The D/I@PATC suspensions were divided into three groups. The first group did not do any treatment, the second group was irradiated with 808 nm (0.5 W/cm2) laser (GX-808-2000-MM, Changchun Radium Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd, China) for 3 min, and the third group was irradiated with 808 nm laser for 3 min and then cooled to room temperature. The morphology of the three groups was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, VEGA 3 LMU, TESCAN, Czech).

4.4. Preparation and characterization of PATC and D/I@PATC

PATC was firstly dissolved in DMSO and stirred for 1 h at 70 °C. DOX and ICG were dissolved in DMSO and stirred for 1 h, and DOX was protonated by triethylamine (TEA). PATC and DOX/ICG were stirred at room temperature for 1 h, then dropped into deionized water and stirred for 6 h. The mixed solution was transferred to a dialysis bag (MWCO 3500 Da) and dialyzed for 48 h with deionized water at 37 °C to obtain D/I@PATC. The only difference in the preparation of PATC was adding deionized water directly to the DMSO solution of PATC. The concentration of DOX and ICG in the initial drug solution and D/I@PATC were measured by using a UV–visible based on their absorbance at 480 nm and 780 nm, respectively. The EE and DLC were calculated according to the following equations:

| EE (%) = Mdrug in D/I@PATC / Minitial drug × 100% |

| DLC (%) = Mdrug in D/I@PATC / MD/I@PATC × 100% |

The UV–Vis spectrum was measured by a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shi- Shimadzu, Japan).

4.5. Stability assay of D/I@PATC particles in vitro

Ten milliliter PBS solution was mixed with 10 mg D/I@PATC to obtain a suspension of D/I@PATC at the concentration of 1 mg/mL. The sample was then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h respectively, and the diameter of the D/I@PATC particles was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) at each time point.

4.6. The photothermal effect of D/I@PATC in vitro

D/I@PATC was prepared to aqueous dispersions with different concentrations (0, 25, 50, 100, 150, 200 μg/mL). The samples were then irradiated with 808 nm (0.5 W/cm2) laser for 3 min and the temperature was measured every 10 s by a thermal infrared camera.

4.7. Laser-controlled DOX release from D/I@PATC in vitro

The PBS suspension of D/I@PATC was irradiated with 808 nm (0.5 W/cm2) laser for 3 min, and then the laser light was kept off for 17 min. The suspension was centrifuged in an ultrafiltration tube to collect the filtrate and particles were dispersed with fresh PBS. The “on/off” light cycle was repeated for 6 times. The fluorescence changes of D/I@PATC particles were monitored by an inverted fluorescence microscope after each “on/off” cycle, and the DOX in the filtrate was measured by UV–vis spectrophotometer.

4.8. Cellular uptake of DOX released from D/I@PATC in vitro

B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cell lines were from Procell Life Science&Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 and dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 units/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cells were cultured in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After incubating B16–F10 cells in a glass-bottomed dish for 24 h, a fresh medium, medium containing D/I@PATC (100 μg/mL) or D/I@PATC + laser (0.5 W/cm2, 3 min, 100 μg/mL) was added, and the cells were incubated for another 8 h. The cells were then washed three times with PBS, and DAPI was used to stain the cell nuclei. Finally, intracellular fluorescence intensity was monitored by CLSM.

4.9. In vitro cytotoxicity assessment

B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cells were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of PATC/ICG. Briefly, B16–F10 and NIH/3T3 cells were incubated in 96-well plates for 24 h, respectively. Different concentrations (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μg/mL) of PATC and ICG in culture medium were added to the 96-well plates. After incubation for 24 h, the cell viability was evaluated by the colorimetric MTT.

4.10. Antitumor efficiency test in vitro

To study the antitumor performance of D/I@PATC in vitro, B16–F10 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and then treated with free DOX, D/I@PATC, D/I@PATC + laser (0.5 W/cm2, 3 min) with the equivalent DOX concentration. After additional 8 h incubation, the cell viability was determined by colorimetric MTT. Live/dead cell staining was used to further confirm the antitumor effect in vitro. Briefly, B16–F10 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h, followed by incubation with free DOX, D/I@PATC, and D/I@PATC + laser (0.5 W/cm2, 3 min) for 8 h, respectively. And then the cells were incubated with Calcein-AM (5 μg/mL) and PI (5 μg/mL) at 37 °C for 20 min. The cells were washed with PBS and monitored with an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73 DP80, Olympus, Japan).

4.11. Preparation and characterization of D/I@PATC MN patches

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Dow Corning) molds were used to fabricate the MN patches. To fabricate the D/I@PATC MNs, the suspensions of D/I@PATC (10 mg/mL) were first deposited into the PDMS micromold under centrifugation (4200 rpm for 5 min) and dried at room temperature. Subsequently, 18% (w/v) PVA (molecular weight: 9000–10,000 Da) and 18% (w/v) sucrose in deionized water were filled into the female mold under centrifugation at 4200 rpm for 5 min. Finally, 18% (w/v) PVA and 18% (w/v) sucrose were poured on the mold to form the backings of MN patch. For the fabrication of blank MN patches, no D/I@PATC suspensions were filled into the mold. For the fabrication of ICG MN patches and DOX MN patches, the D/I@PATC suspensions were replaced with equivalent ICG or DOX suspensions respectively. The morphology of D/I@PATC MN patch was observed using SEM, and optical microscopy (TL3000 Ergo, LEICA, Germany).

4.12. Photothermal properties of MN patches in vitro

To evaluate the NIR laser activation behavior of ICG and the photothermal stability of D/I PATC in MNs, blank MN patches, DOX MN patches, ICG MN patches, and D/I@PATC MN patches were irradiated with 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2). The real-time temperature change and thermal images of MNs were acquired and monitored by a thermal infrared camera (IVIS Lumina XRMS, PerkinElmer, America). In addition, D/I PATC MN patches and ICG MN patches were irradiated with 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2) for 5 on/off cycles. In each cycle, the MN patches were exposed to a NIR light source for 3 min and then cooled down for another 3 min. Temperature changes were recorded by a thermal infrared camera.

4.13. Mechanical behavior test of D/I@PATC MN patches

The mechanical strength of the D/I@PATC MN patch was tested using a force measurement system (ESM303, Mark-10, America). The D/I@PATC MN patch was fixed on the rigid stainless-steel platform positioned vertically with needle tips upward, and the sensor probe moved towards the MNs in the vertical direction at a constant speed of 2.1 mm/min. The change of the compressive force of the needle with the probe displacement was recorded. To evaluate the skin penetrating ability of D/I@PATC MN patch, D/I@PATC MN patch was applied to rat skin ex vivo for 15 min, and then the residual patch was removed. After removal, the D/I@PATC particles embedded under the skin were observed by optical microscopy. The MNs-applied skin was cryo-embedded with the OCT complex to assess the depth of insertion. Frozen specimens were cut into 10 μm thick sections using a freezing microtome (HM525 NX, Thermofisher, Germany), and then the skin tissue sections were observed under an inverted microscope.

4.14. In vivo imaging and biodistribution

All the animal studies were following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan University, and were approved by the animal ethics committee of Wuhan University. When the tumor volume of mice reached 60–80 mm3, the tumor-bearing C57BL/6 female mice were divided into 3 groups randomly: (1) blank MN patch group, (2) D/I@PATC MN patch group, and (3) D/I@PATC intravenous injection (I·V.) group. MN patch was pressed on the tumor site for 45 s by thumb, and kept for 15 min without pressure. Simultaneously, an equal amount of D/I@PATC was injected intravenously into B16–F10 tumor-bearing mice, and a near-infrared fluorescence imaging system (Series II 900/1700, Suzhou NIR Optics Technologies CO., Ltd, China) was used to monitor fluorescence signals in tumors after different treatments. 808 nm (90 mW/cm2) laser was used as the excitation light. The emitted light was filtered through 810–880 nm filter and the InGaAs camera was used to collect the fluorescence signal. NIRF images were collected at different times (0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h). All of the mice were sacrificed at 24 h, and the NIR fluorescence signal distributions in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and tumor were observed.

4.15. In vivo photothermal effect

The administration of D/I@PATC MN patch was almost similar to the aforementioned in the vivo imaging study. After receiving the administration of D/I@PATC MN patch, ICG MN patch or blank MN patch, the tumor site was irradiated by 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2), and the temperature changes were detected by the thermal infrared camera system (IVIS Lumina XRMS, PerkinElmer, America) and photothermal images were taken every 10 s. Twenty-four hours post MN patches application, the tumor sites were irradiation by 808 nm laser again and the temperature changes were recorded. To investigate the photothermal stability of D/I@PATC in vivo, the tumor site of mice treated with D/I@PATC MN patches were irradiated with 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2) for 5 on/off cycles. In each cycle, the tumors were exposed to a NIR light source for 3 min and then cooled down for another 3 min. The temperature changes curve was measured by the thermal infrared camera.

4.16. Monitoring of drug release from D/I@PATC MN patches in vivo

C57BL/6 tumor-bearing mice were divided into two groups and received the same D/I@PATC MN patch administration. Then, one group was given multiple laser “on/off” irradiation cycles (laser on 3 min and off 17 min), and the fluorescence at the tumor site was photographed after each cycle by a fluorescence microscope. The other group was treated with the same MN patch, but didn't receive laser irradiation. Fluorescence images were taken at the same time points with the first group.

4.17. In vivo antitumor efficacy

The tumor-bearing C57BL/6 female mice were randomly divided into 8 groups (n = 5) after the tumor volume reached 60–100 mm3: (1) untreated, (2) blank MN patches, (3) D/I@PATC intravenous injection (I·V.) + Laser (++), (4) D/I@PATC MN patches, (5) DOX MN patches, (6) ICG MN patches + Laser (++), (7) D/I@PATC MN patches + Laser (+), (8) D/I@PATC MN patches + Laser (++). The administration method of MN patch was the same to the aforementioned in vivo imaging study. After 1 h, the tumor site was irradiated by an 808 nm laser (0.5 W/cm2) for 3 min for laser groups. Subsequently, tumor volume and body weight were measured and recorded every day. Finally, the mice were euthanized on day 12, and the tumor and main organs were sectioned for TUNEL or H&E staining.

4.18. Safety evaluation

To evaluate biosafety of D/I@PATC MN patches, healthy C57BL/6 mice were divided into 3 groups: (1) untreated; (2) D/I@PATC MN patches without laser irradiation; (3) D/I@PATC MN patches with laser irradiation for 3 min (808 nm, 0.5 W/cm2). The skin recovery of the mice was recorded at 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 days after MN patches administration. To further evaluate biocompatibility, blood was collected from the orbital vein of mice in each group to evaluate the level of blood parameters.

4.19. Statistical analysis

The experimental results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Student's t-test or ANOVA. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). All statistical analysis were carried out with Prism software (PRISM 5.01 GraphPad Software).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal studies were following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Wuhan University, and were approved by the animal ethics committee of Wuhan University (reference number: WP20210461).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chenyuan Wang: Writing – original draft, performed the experiments. Yongnian Zeng: Writing – original draft. Kai-Feng Chen: performed the experiments. Jiawei Lin: performed the experiments. Qianqian Yuan: also made contributions to the, Writing – original draft. Xue Jiang: also made contributions to the, Writing – original draft. Gaosong Wu: also made contributions to the, Writing – original draft. Fubing Wang: designed the project, also made contributions to the, Writing – original draft. Yong-Guang Jia: designed the project, also made contributions to the, Writing – original draft. Wei Li: designed the project, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the following fundings: National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 52103182, 21704026, 22075087), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (No. 2021CFB103) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2042021kf0073).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.03.016.

Contributor Information

Fubing Wang, Email: wfb20042002@sina.com.

Yong-Guang Jia, Email: ygjia@scut.edu.cn.

Wei Li, Email: weili.mn@whu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Apalla Z., Nashan D., Weller R.B., Castellsague X. Skin cancer: epidemiology, disease burden, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic approaches. Dermatol. Ther. 2017;7:S5–S19. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0165-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo J.A., Fisher D.E. The melanoma revolution: from UV carcinogenesis to a new era in therapeutics. Science. 2014;346(6212):945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1253735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saginala K., Barsouk A., Aluru J.S., Rawla P., Barsouk A. Epidemiology of melanoma. Med. Sci. 2021;9(4):63. doi: 10.3390/medsci9040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulson K.G., Gupta D., Kim T.S., Veatch J.R., Byrd D.R., Bhatia S., Wojcik K., Chapuis A.G., Thompson J.A., Madeleine M.M., Gardner J.M. Age-specific incidence of melanoma in the United States. Jama Dermatol. 2020;156(1):57–64. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poklepovic A.S., Luke J.J. Considering adjuvant therapy for stage II melanoma. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1166–1174. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyebally S., Abiodun A., Slater S., Ghosh A.K. Treating the treatment: chemotherapy-induced multi-organ toxicity. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(3) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chabner B.A., Roberts T.G. Timeline - chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng M.B., Yue C.X., Ma Y.F., Gong P., Zhao P.F., Zheng C.F., Sheng Z.H., Zhang P.F., Wang Z.H., Cai L.T. Single-step assembly of DOX/ICG loaded lipid-polymer nanoparticles for highly effective chemo-photothermal combination therapy. ACS Nano. 2013;7(3):2056–2067. doi: 10.1021/nn400334y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C.L., Zhang Z.M., Guo Q., Zhang L., Fan F., Qin Y., Wang H., Zhou S., Ou W.B.Y., Sun H.F., Leng X.G., Pang X.B., Kong D.L., Zhang L.H., Zhu D.W. A dual-model imaging theragnostic system based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles for enhanced cancer phototherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(19) doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C.Y., Xiong C.X., Li Z.K., Hu L.F., Wei J.S., Tian J. Defect-engineered porphyrinic metal-organic framework nanoparticles for targeted multimodal cancer phototheranostics. Chem. Commun. 2021;57(33):4035–4038. doi: 10.1039/d0cc07903k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kremkau F.W. Cancer therapy with ultrasound: a historical review. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 1979;7(4):287–300. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870070410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho Y.J., Li J.P., Fan C.H., Liu H.L., Yeh C.K. Ultrasound in tumor immunotherapy: current status and future developments. J. Contr. Release. 2020;323:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu L., Liao Z., Luo Z., Wu Y.-L., Herrmann A., Huo S. Ultrasound-controlled drug release and drug activation for cancer therapy. Explorations. 2021;1(3) doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X.H., Wang L.C., Xu Y.J., Du W.X., Cai X.J., Wang F.J., Ling Y., Chen H.R., Wang Z.G., Hu B., Zheng Y.Y. A pH and magnetic dual-response hydrogel for synergistic chemo-magnetic hyperthermia tumor therapy. RSC Adv. 2018;8(18):9812–9821. doi: 10.1039/c8ra00215k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Miao Y., Li G., Su M., Chen X., Zhang H., Zhang Y., Jiao W., He Y., Yi J., Liu X., Fan H. Engineering ferrite nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic response for advanced biomedical applications. Mater Today Adv. 2020;8 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q., Wang C., Cheng L., He W.W., Cheng Z., Liu Z. Protein modified upconversion nanoparticles for imaging-guided combined photothermal and photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2014;35(9):2915–2923. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agostinis P., Berg K., Cengel K.A., Foster T.H., Girotti A.W., Gollnick S.O., Hahn S.M., Hamblin M.R., Juzeniene A., Kessel D., Korbelik M., Moan J., Mroz P., Nowis D., Piette J., Wilson B.C., Golab J. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. Ca - Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61(4):250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei S.H., Quan G.L., Lu C., Pan X., Wu C.B. Dissolving microneedles integrated with pH-responsive micelles containing AIEgen with ultra-photostability for enhancing melanoma photothermal therapy. Biomater Sci-Uk. 2020;8(20):5739–5750. doi: 10.1039/d0bm00914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H.X., Wang W.S., Li C.P., Xu A., Qiu B.S., Li F.F., Ding W.P. Flav7+DOX co-loaded separable microneedle for light-triggered chemo-thermal therapy of superficial tumors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;428 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Q., Chen G., Gong K.K., Wang J., Ge X.X., Liu X.Q., Guo S.J., Wang F. MnO2-Laden black phosphorus for MRI-guided synergistic PDT. PTT, and Chemotherapy, Matter-Us. 2019;1(2):496–512. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin W.B., Quan G.L., Sun Y., Chen M.L., Yang P.P., Feng D.S., Wen T., Hu X.Y., Pan X., Wu C.B. Dissolving microneedles with spatiotemporally controlled pulsatile release nanosystem for synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy of melanoma. Theranostics. 2020;10(18):8179–8196. doi: 10.7150/thno.44194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hao Y., Chen Y., He X., Yang F., Han R., Yang C., Li W., Qian Z. Near-infrared responsive 5-fluorouracil and indocyanine green loaded MPEG-PCL nanoparticle integrated with dissolvable microneedle for skin cancer therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2020;5(3):542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y., Zhou Y., Yang D., Gao X., Wen T., Fu J., Wen X., Quan G., Pan X., Wu C. Intelligent and spatiotemporal drug release based on multifunctional nanoparticle-integrated dissolving microneedle system for synergetic chemo-photothermal therapy to eradicate melanoma. Acta Biomater. 2021;135:164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prausnitz M.R. Microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56(5):581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larraneta E., McCrudden M.T., Courtenay A.J., Donnelly R.F. Microneedles: a new frontier in nanomedicine delivery. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2016;33(5):1055–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1885-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W., Terry R.N., Tang J., Feng M.H.R., Schwendeman S.P., Prausnitz M.R. Rapidly separable microneedle patch for the sustained release of a contraceptive. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2019;3(3):220–229. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnelly R.F., Singh T.R.R., Woolfson A.D. Microneedle-based drug delivery systems: microfabrication, drug delivery, and safety. Drug Deliv. 2010;17(4):187–207. doi: 10.3109/10717541003667798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu T., Chen M.L., Fu J.T., Sun Y., Lu C., Quan G.L., Pan X., Wu C.B. Recent advances in microneedles-mediated transdermal delivery of protein and peptide drugs. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2021;11(8):2326–2343. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W., Tang J., Terry R.N., Li S., Brunie A., Callahan R.L., Noel R.K., Rodriguez C.A., Schwendeman S.P., Prausnitz M.R. Long-acting reversible contraception by effervescent microneedle patch. Sci. Adv. 2019;5(11) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J.C., Zhang Y.Q., Ye Y.Q., DiSanto R., Sun W.J., Ranson D., Ligler F.S., Buse J.B., Gu Z. Microneedle-array patches loaded with hypoxia-sensitive vesicles provide fast glucose-responsive insulin delivery. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(27):8260–8265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505405112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K.F., Zhang Y., Lin J., Chen J.Y., Lin C., Gao M., Chen Y., Liu S., Wang L., Cui Z.K., Jia Y.G. Upper critical solution temperature polyvalent scaffolds aggregate and exterminate bacteria. Small. 2022;18(11) doi: 10.1002/smll.202107374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia Y.G., Chen K.F., Gao M., Liu S., Wang J., Chen X.H., Wang L., Chen Y.H., Song W.J., Zhang H.T., Ren L., Zhu X.X., Tang B.Z. Visualizing phase transition of upper critical solution temperature (UCST) polymers with AIE. Sci. China Chem. 2021;64(3):403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraft J.C., Ho R.J. Interactions of indocyanine green and lipid in enhancing near-infrared fluorescence properties: the basis for near-infrared imaging in vivo. Biochemistry. 2014;53(8):1275–1283. doi: 10.1021/bi500021j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engel E., Schraml R., Maisch T., Kobuch K., Koenig B., Szeimies R.M., Hillenkamp J., Baumler W., Vasold R. Light-induced decomposition of indocyanine green. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49(5):1777–1783. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.