Abstract

A range of neurodegenerative and related aging diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes, are linked to toxic protein aggregation. Yet the mechanisms of protein aggregation inhibition by small molecule inhibitors remain poorly understood, in part because most protein targets of aggregation assembly are partially unfolded or intrinsically disordered, which hinders detailed structural characterization of protein-inhibitor complexes and structural-based inhibitor design. Herein we employed a parallel small molecule library-screening approach to identify inhibitors against three prototype amyloidogenic proteins in neurodegeneration and related proteinopathies: amylin, Aβ and tau. One remarkable class of inhibitors identified from these screens against different amyloidogenic proteins was catechol-containing compounds and redox-related quinones/anthraquinones. Secondary assays validated most of the identified inhibitors. In vivo efficacy evaluation of a selected catechol-containing compound, rosmarinic acid, demonstrated its strong mitigating effects of amylin amyloid deposition and related diabetic pathology in transgenic HIP rats. Further systematic investigation of selected class of inhibitors under aerobic and anaerobic conditions revealed that the redox state of the broad class of catechol-containing compounds is a key determinant of the amyloid inhibitor activities. The molecular insights we gained not only explain why a large number of catechol-containing polyphenolic natural compounds, often enriched in healthy diet, have anti-neurodegeneration and anti-aging activities, but also could guide the rational design of therapeutic or nutraceutical strategies to target a broad range of neurodegenerative and related aging diseases.

Keywords: Protein misfolding diseases, Aggregation modifying inhibitors, Drug library screening, Catechol-containing compounds, Redox regulation, HIP rats

1. Introduction

Protein aggregation diseases represent some of the most debilitating and increasingly more common aging-related human diseases. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, prion diseases, and type 2 diabetes all fall under this category [1–5]. While currently there is no FDA approved drug treatment available, data over the years continue to support the notion that one of the attractive therapeutic targets against amyloidosis are the misfolding protein amyloids themselves [6–8]. Insights gained from several latest high-resolution amyloid structures, and atomic details on their interactions with amyloid inhibitors have provided potentially exciting new paths towards the identification, characterization, and optimization of clinically viable inhibitor candidates [9–15]. Key to this development is achieving a better understanding of protein aggregation inhibition mechanisms and processes. Recent investigations have begun to elucidate some of the covalent and non-covalent mechanisms for small molecules or peptide-based inhibitors interacting with amyloidogenic proteins at various stages of protein aggregation formation [12,14,16,17]. Examples include stabilizing the soluble native confirmations of some amyloidogenic proteins [18], perturbing or “remodeling” unaggregated or pre-aggregated amyloid species towards forming presumably innocuous, non-amyloidogenic aggregates [19–21], or even accelerating amyloid formation [22]. However, in many cases, chemical classes of the inhibitors and a clear link between the chemical mode of action of an inhibitor and its macromolecular partner are poorly defined. Moreover, the biochemical, biophysical and pharmacological underpinnings of inhibitor-perturbed amyloid aggregation pathways or alternative aggregate assemblies are not always clear.

To systematically identify broad classes of small molecules and chemical structure scaffolds of protein aggregation modifying inhibitors, we screened a US National Institutes of Health Clinical Collection (NIHCC) drug-repurposing library of 700 drugs and investigational compounds with diverse molecular scaffolds of chemical structures. We employed the thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence-based assay to monitor toxic amyloid formation utilizing a 384-well plate semi high-throughput screening platform [12,23,24] (Fig. S1D). To make our findings broadly applicable, we screened in parallel against three prototype amyloidogenic proteins: amylin (or islet amyloid polypeptide, IAPP), Aβ (Fig. S1A) as well as 2N4R tau [25]. Amylin amyloidosis and plaque deposition in the pancreas are hallmark features of type 2 diabetes [1,26], whereas Aβ plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles are well-established neuropathogenic biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.

Our parallel screens enabled us to identify several classes of compounds that displayed inhibitory effects against all three amyloidogenic targets. One salient feature of significant percentage of identified inhibitors is that they are catechol-containing compounds. Multiple secondary assays were used for validation. As a proof-of-principle study, we further selected one catechol compound, rosmarinic acid, and demonstrated its in vivo efficacies in a diabetic animal model relevant to amylin amyloid. On mechanism of inhibition, we serendipitously discovered that autoxidation significantly enhanced this broad class of catechol-containing amyloid inhibitors. Our work revealed that redox status is a critical factor affecting the activities of this broad class of amyloid inhibitors.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Peptides and chemicals

Synthetic amidated human amylin was purchased from AnaSpec Inc. (Fremont, CA) and its purity was ≥ 95% based on peak area by HPLC. The peptide quality was further validated by the Virginia Tech Mass Spectrometry Incubator. Synthetic Aβ42 was also purchased from AnaSpec Inc. and its purity was ≥ 95% based on peak area by HPLC. Hexafluroisopropanol (HFIP) and thioflavin T (ThT) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Small molecule amyloid inhibitors and relevant control compounds were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada), Fisher Scientific Inc. (Hampton, NH), Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) or Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline (DBPS) pH 7.4, was purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). Black 96-well non-stick-clear-bottom plates and optically clear sealing film were purchased from Greiner Bio-one (Germany) and Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA) respectively. 300-mesh formvar-carbon-coated copper grids and uranyl acetate replacement solution (UAR) were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfeild, PA).

Lyophilized amylin powder (0.5 mg) was initially dissolved in 100% HFIP at a final concentration of 1–2 mM. The additional lyophilizing step was employed to eliminate traces of organic solvents, which have been shown to affect amylin aggregation. Aliquots were dissolved directly into DPBS, 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 or 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 for all amylin amyloid-related in vitro assays. All remaining 1–2 mM stocks in 100% DMSO were stored at – 80 °C until later use. The lyophilized powder from all compounds and ThT were dissolved in DMSO (10 mM) and distilled water or relevant buffer (1–4 mM). These stocks were stored at – 20 °C until later use. Residual DMSO in the final samples used for all in vitro assays ranged from 0% to 9.5%. We determined that these DMSO concentrations had negligible effects on amylin amyloid aggregation as reflected by ThT fluorescence, TEM, PICUP assay, and inhibitor-induced amylin amyloid remodeling assays. UV-Vis absorption spectra were collected on a Varian Cary 50 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Equal concentration of catechol, norepinephrine, and rosmarinic acid was used for each compound. Aerobic and anaerobic conditions referred in each case as exposure to air or incubation in an anaerobic chamber (described below) at the specified duration.

2.2. Thioflavin-T fluorescence screening assays

Fluorescence experiments were performed using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) as described in our previous works [27,28]. All kinetic reads were taken in non-binding all black clear bottom Greiner plates covered with optically clear sheets to minimize the evaporation of the solution in each well and stirred for 10 s prior to each reading. All experiments were repeated three times using peptide stock solutions from the same lot. Experimental conditions of the ThT fluorescence screening assays (such as protein concentration, compound to protein concentration ratio etc.) were optimized for each protein using EGCG as a reference control.

-

Screening against amylin amyloid

Amylin stock preparation was initiated by dissolving lyophilized human amylin powder in 100% HFIP. After at least 2 h of incubation at room temperature, HFIP was removed and the resulting amylin powder was re-dissolved in 100% DMSO and quantified by a standard BCA micro plate assay (i.e. HFIP is extremely volatile and difficult to accurately pipette; thus, DMSO is a better solvent for peptide transfer. Initial HFIP dissolution was employed because it has been suggested to aid in removal of trace contaminants that may be present within lyophilized batches of peptide). Solutions of 400 μM amylin (100% DMSO) were subsequently diluted with ThT in 1X DPBS and aliquoted to reading plate wells containing 0.45 μL of compound or vehicle buffer controls to a final volume of 15 μL. Final concentrations prior to amylin amyloid aggregation were 10 μM amylin, 30 μM compound and 30 μM ThT. Aggregation reactions were incubated at 25 °C until the approximated plateau fluorescent readings. All plates were continuously monitored for ThT fluorescence every 10 min (plates were shaken briefly prior to each read) at excitation 444 nm and emission 490 nm until the plateau phase was reached.

-

Screening against 2N4R tau

Recombinant 2N4R tau (the longest and the most studied human tau isoform) was purified to homogeneity (>90% in purity) as previously described [29]. Purified 2N4R tau was initially dissolved in 100% 1X PNE buffer, was buffer exchanged with 1X HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES, 30 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Amyloid aggregation was initiated in the presence or absence of compound by diluting tau protein into the wells of the reading plates to a final 34.4 μM of tau, 12.5 μM ThT and 0.06 mg/mL of heparin (served to promote tau amyloid formation) in each well. For compound treated wells, final molar concentration of compound to tau was 2:1. Tau aggregation reactions were incubated at 37 °C and the fluorescent readings were taken at excitation 444 nm/emission 490 nm.

-

Screening against Aβ42 peptide

In contrast to the ThT fluorescence assays for amylin and 2N4R tau, non-continuous, two-point measurements were taken to represent starting and ending (at plateau) fluorescent signals for Aβ42. Unaggregated solutions of Aβ42 were typically prepared by dissolving lyophilized Aβ42 powder with 100% HFIP. Subsequent peptide quantification of this solution was estimated based on a standard micro plate BCA assay. Initial stock solution preparation of Aβ42 for the ThT assay were prepared by evaporating HFIP treated stocks followed by a modified two-step aqueous dissolution process as previously described: Herein, HFIP evaporated stocks of Aβ42 were dissolved in 60 mM NaOH. Next, these solutions were further diluted in 1X DPBS such that the final solution consisted of approximately 2.4 mM NaOH (i.e. 4% 60 mM NaOH, 96% 1X DPBS). Immediately after the addition of 1X DPBS, 6.48 μL aliquots of Aβ42 and 0.52 μL aliquots of compound or buffer treated controls were distributed to the ThT reading plates. All plates were sealed to prevent evaporation and allowed to incubate at 37 °C until the estimated plateau of aggregation (24 h). Next, the reading plates were centrifuged prior to receiving 14 μL of a 45 μM ThT solution prepared in 50 mM Glycine-NaOH, pH 8.6. Finally, all plates were read at excitation 444 nm/emission 490 in order to estimate plateau phase amyloid aggregation as indicated by ThT fluorescence. Note, the final concentration of Aβ42 prior to being titrated with ThT, was approximately 12 μM, at a 3:1 molar ratio of compound to Aβ42.

The NIH Clinical Collection (NIHCC) library contains a total of 700 FDA-approved drugs and investigational compounds with diverse chemical structures. These small molecules have a history of use in human clinical trials. The collection was assembled through the NIH Molecular Libraries and Imaging Initiative. The library was supplied in 96-well plates in DMSO. For screening, 384-well plate was used. Bravo liquid handler with 96-channel disposable tip head (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE) was used to aid sample transfer. Total volume in each well was 15 μL. Highest residual DMSO in any well was < 5.4%, which has negligible effect on the fluorescent signals.

2.3. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis

TEM images were obtained by a JEOL 1400 microscope operating at 120 kV. Samples consisting of 30 μM amylin (20 mM Tris-HCl, 2% DMSO, pH 7.4) in the presence of drug or vehicle control were incubated for ≥ 48 h at 37 °C with agitation. Prior to imaging, 2–5 μL of sample were blotted on a 200-mesh formvar-carbon coated grid for 5 min and then stained with uranyl acetate (1%). Both sample and stain solutions were wicked dry (sample dried before addition of stain) by filter paper. Qualitative assessments of the amounts of fibrils or oligomers observed were made by taking representative images following a careful survey of each grid (>15–20 locations on each grid were surveyed).

2.4. Photo-induced crosslinking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) assay

Amylin aliquots from a master mix in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 were added separately to 0.6 mL eppendorf tubes containing small molecule inhibitors or DMSO vehicle loaded controls. Crosslinking for each tube was subsequently initiated by adding tris(bipyridyl)Ru(II) complex (Ruby) and ammonium persulfate (APS) (Typical amylin: Rubpy:APS ratios were fixed at 1:2:20, respectively, at a final volume of 15–20 μL), followed by exposure to visible light, emitted from a 150-Watt incandescent light bulb, from a distance of 5 cm and for a duration of 5 s. The reaction was quenched by addition of 1X SDS sample buffer. PICUP results were visualized by SDS-PAGE (16% acrylamide gels containing 6 M urea), followed by silver staining. Final concentrations for all PICUP reactions included 30 μM of amylin and 150 μM of each compound.

2.5. ThT fluorescence-based amyloid remodeling assays

Similarly with regular ThT fluorescence amyloid formation assays, remodeling assays extended the monitoring of the fluorescence signals continuously after an inhibitor or a control compound was spiked into the aggregation system (amyloidogenic protein, ThT, buffer, heparin). The maximum volume of spiked compound was limited to 5% of total sample volume in each well so that the baseline fluorescence signal was minimally changed.

2.6. Aggregation assays in anaerobic chamber

All reagents including buffers, protein and compounds were made anaerobic by flushing with nitrogen prior to being placed within an anaerobic chamber (glove box). H2 gas mixed with inert gas is circulated through metal catalyst to remove O2 gas in the chamber. Oxygen level was maintained between 15 and 50 ppm within the anaerobic chamber. Typical aggregating conditions within the chamber were maintained at room temperature (25–30 °C). All anaerobic chamber-based ThT fluorescence assays were discontinuous, two-point measurements (starting point, ending or plateau point).

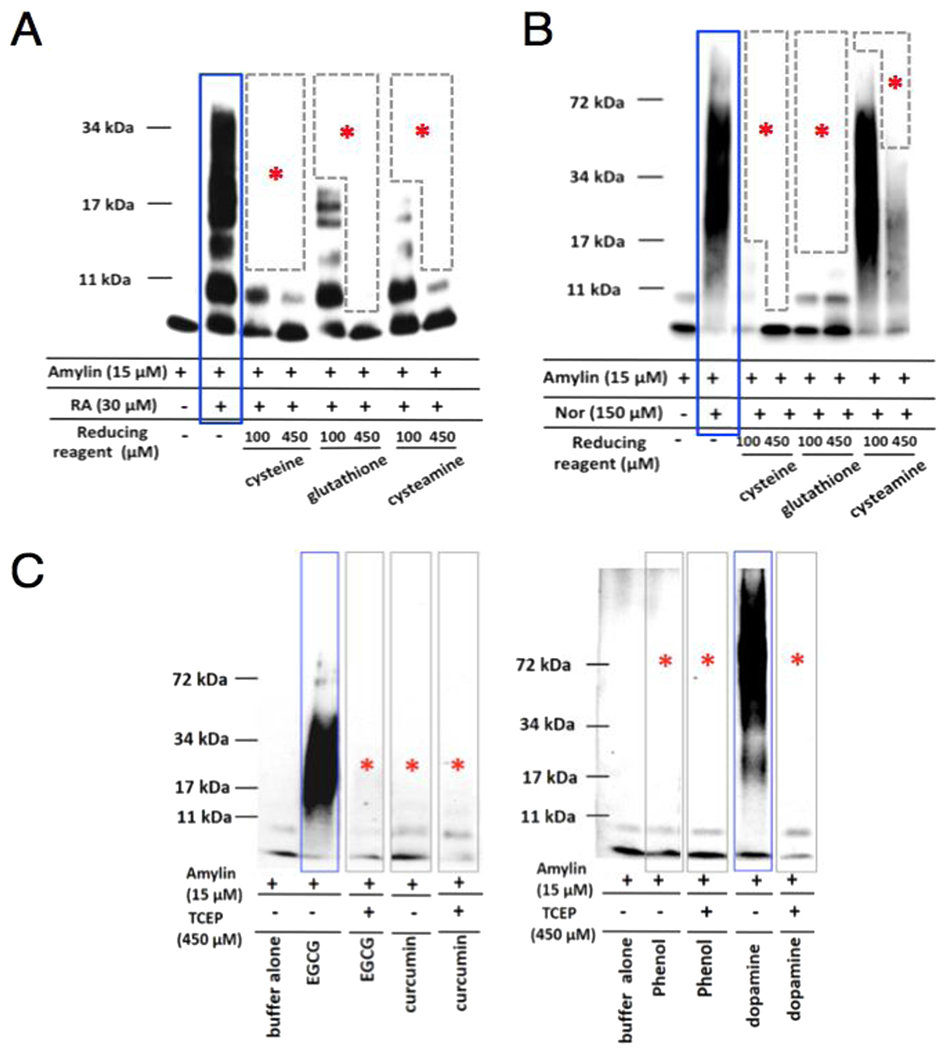

2.7. Gel-based amyloid remodeling assay

Vehicle control or specified compounds were spiked into freshly dissolved amylin samples (containing amylin and buffer) with or without reducing reagents cysteine, glutathione, cysteamine or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Thereafter amylin aggregation was allowed to proceed for 3 days. Final amylin concentration was 15 μM that included specified concentrations of a compound and reducing agent. After 3 days, these samples were vacuum dried and re-dissolved in 6.5 M urea containing 15 mM Tris and 1X SDS Laemmeli sample buffer, boiled at 95 °C for 5–10 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with anti-amylin primary antibody (T-4157, 1:5000, Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA). All gel-based amyloid remodeling assays were repeated at least twice.

2.8. Liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis

Analyses were performed on a Waters Synapt G2-S HDMS interfaced with an Acquity I-Class UPLC system. Freshly dissolved (time 0) or aged (exposure to air for 72 or 96 h) norepinephrine samples at a concentration of 37.5 μM (diluted in a mixed solvent of 2:98, acetonitrile:water, v/v) were characterized by positive mode LC-MS for its oxidative products. Norepinephrine was reliably detected on the reverse phase column with a retention time of 0.7 min. Visual inspection of the chromatograms showed a new peak at retention time between 0.85 and 0.95 min in the 72- and 96-hour samples that was not present at 0 h. Oxidized species (new peaks) were characterized by MS/MS analysis.

The binary solvent system was composed of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). A 10-minute gradient was used for the analysis with the following conditions: initial and hold for 30 s at 1%B, a linear gradient to 90%B at 8 min, hold at 90%B to 8.5 min and return to initial condition at 9 min. Sample volumes for MS analysis were between 2 and 4 μL and injected onto a Waters UPLC BEH C18 (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) held at 35 °C for MS analysis. Source conditions for the mass spectrometer were: capillary 2.8 kV, source temperature 125 °C, sample cone 30 V, source offset 80 V, desolvation gas 500 L/Hr, desolvation temperature 400 °C, cone gas 50 L/Hr, and nebulizer gas 6 par. The m/z scan range was 50–1800 for MS analysis and 50–600 for MS/MS analysis and a collision energy ramp of 15–40 eV was used for MS/MS analysis.

2.9. Animal studies

Transgenic HIP rats (RIP-HAT) and wild-type Sprague–Dawley (SD) control rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). We used dietary supplementation approach to study the in vivo effects of RA on HIP rat amylin amyloid islet deposition and diabetic pathology. Dietary supplemental treatments were initiated when HIP rats were at prediabetic stage (5 –6 months old), and the preventative treatment lasted for 4 months. Diet supplementation with RA (0.5% w/w) was prepared by Envigo Inc. (Madison, WI). Bulk RA was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON), and its identity and purity were further validated at Virginia Tech Mass Spectrometry Incubator Facilities. Standard rodent chow diet (without RA) was used for the untreated HIP rats and wild-type SD control rat groups. All animals were housed in temperature- (23 ± 2 °C) and light-controlled, pathogen-free animal quarters and were provided ad libitum access to diet. Animal protocol was approved by institutional IACUC committee. Sera samples for glucose and insulin analyses were collected from the tail veins of the rats. Glucose levels were measured with an Agamatrix presto meter (AgaMatrix Inc., Salem, NH). Insulin concentrations were quantified by a rat insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

2.10. Islet immunohistochemistry and amyloid staining

At the end of animal studies, rats were euthanized, and the pancreas tissues were dissected and fixed in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde buffer (pH 7.2). Pancreas samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned by AML Laboratories Inc. (St. Augustine, FL). A series of tissue section (5 μm thickness at 200 μm interval) were prepared, mounted on glass slides, and stained with Congo Red dye (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or with rabbit anti-amylin primary antibody (T-4157, Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA) followed by a rabbit ImmPRESS HRP anti-rabbit IgG (peroxidase) polymer detection kit and Vector NovaRED substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). Images were visualized by microscopy (Zeiss Axio Observer, Thornwood, NY) or Nikon Eclipase Ti–U and were analyzed with Zeiss 2 (blue edition) or NIS-Elements AR 411.00.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M and the differences were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance followed by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons (amylin kinetics) or unpaired Student’s t test. These tests were implemented within GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0). p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Library screening identifies catechol-containing compounds are a broad class of protein aggregation inhibitors

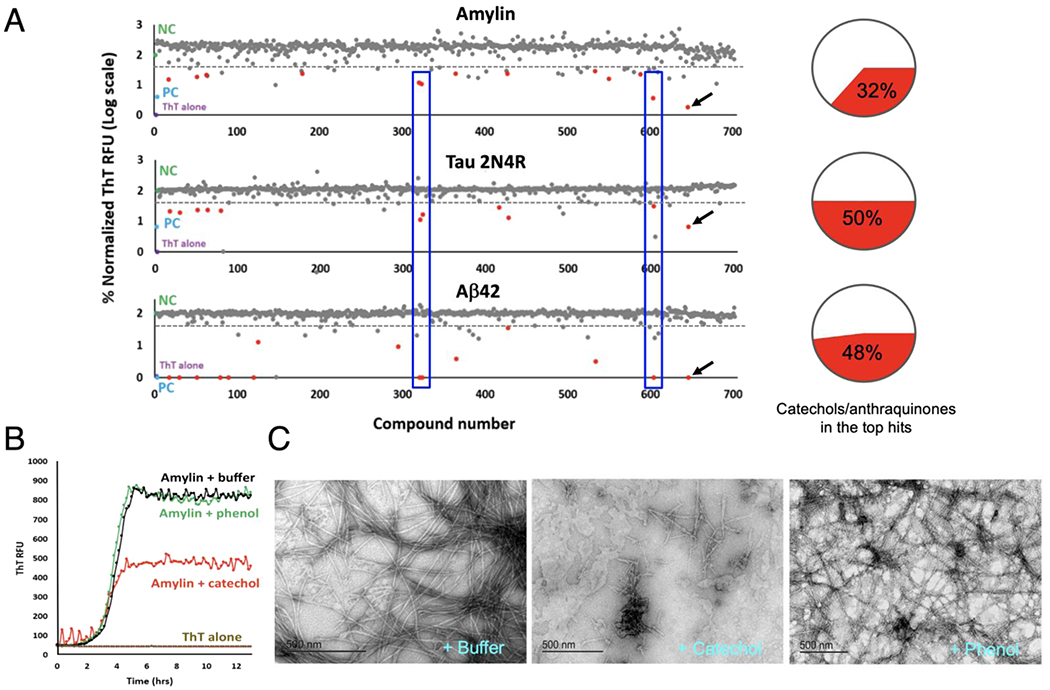

One of the most salient findings from the screening is that catechols and redox-related quinones/anthraquinones represent a broad class of amyloid inhibitors. As shown in Fig. 1A, these molecules (highlighted as red dots in each of the three screens) made up a substantial portion of the identified strong inhibitors, which were defined as exhibiting greater than three standard deviation units below the ThT RFU observed for buffer treated individual amyloidogenic protein controls (dotted line). In total, 13 out of 41 strong inhibitors (32%) for amylin, 11 out of 22 (50%) for tau (2N4R isoform) [29], and 14 out of 29 (48%) for Aβ were catechols or quinone/anthraquinones (Fig. 1A). In the screens against amylin amyloid, out of 22 catechols and quinones/anthraquinones from the NIHCC library, 21 of them exhibited significant amyloid inhibitory activities (<70% normalized RFU; Table S1) with isoproterenol being the exception, with only weak inhibitory activities.

Fig. 1.

Diversity drug library screening identifies catechols and redox-related anthraquinones as a broad class of amyloid inhibitors. (A) Catechol-containing compounds or redox-related anthraquinones (shown as red dots) were observed to comprise 32% of the top hits (13 out of total 41 top hits) against amylin amyloid formation, 50% of the top hits (11 out of total 22 top hits) against 2N4R isoform of human tau protein, and 48% of the top hits (14 out of total 29 top hits) against Aβ42 amyloid. Top hits were defined by exhibiting a ThT fluorescent signal ≥ three standard deviations below buffer treated negative controls. Each dot represents a drug in the NIH Clinical Collection drug library (total 700 compounds). Buffer treated negative controls (NC), are shown in green. Positive controls (PC), amyloidogenic proteins treated with EGCG, are shown in blue. ThT alone, the assay background, is shown in cyan. Notice y-axis is shown in log-scale. A drug with a value of 2 in y-axis in the figure indicates that it has no inhibitory activity. Examples of common hits (drugs #318, #321, and #601) for all three amyloid proteins are shown in blue boxes. One compound in the library was EGCG (red dots with black arrows), providing collaborating evidence of consistency of the screening method. (B) Catechol, but not phenol, demonstrates moderate yet significant anti-amylin amyloid effects as exhibited by ThT fluorescence assay. (C) TEM analyses validate that catechol, but not phenol, significantly reduces amylin fibril formation. Catechol’s effect is moderate as reflected by the presence of some short fibrils. Typical molar ratios of compound to amyloidogenic protein were 3:1 for amylin and Aβ42 ThT assays and 2:1 for tau ThT assays. Due to catechol’s weak anti-amyloid effect, 50:1 drug:amylin ratios were used for the TEM assays shown.

Similar with amylin screening results, 19 out of 22 catechols and quinones/anthraquinones showed significant activities against either tau 2N4R or Aβ42 amyloid respectively (Tables S2 and S3). Chemical structures of catechols and quinones/anthraquinones of the top hits are shown (Fig. S2). Numerous hits such as idarubicin (Compound #318), daunorubicin (Compound #321), and rifapentine (Compound #601), showed strong inhibitory effects to all three amyloidogenic proteins (boxed red dots in Fig. 1A), whereas a few hits displayed preferential inhibition, such as rutin (Compound #548; Tables S1–S3), which preferentially inhibited amylin amyloid formation.

To test the hypothesis whether the catechol functional group alone inhibits amyloid formation, we tested catechol in secondary assays and compared it with its control analog phenol. Catechol demonstrated moderate yet significant activities in amylin amyloid inhibition in both ThT fluorescence assays and TEM analyses, whereas phenol showed no such inhibitory effects in both assays (Figs. 1B and 1C). Catechol’s modest activity was reflected in that 50:1 catechol:amylin molar ratio of the compound was required to see clearly effect of reduced fibril amounts in the TEM studies in comparison with buffer or phenol treatment controls (Fig. 1C), These data demonstrate that the catechol functional moiety possesses general anti-amyloid activities. Our finding is supported not only by individual catechol-containing inhibitor examples in the literature [5,27,28,30,31], but also by a large-scale computational data mining study: In a fragment-based combinatorial library screening to identify molecular scaffolds to target certain amyloidogenic proteins in neurodegeneration [32], the catechol group was identified as the fragment with the highest observed occurrence, present in nearly 4,500 compounds among the 16,850 (27%) in the Aβ small molecule library.

Another class of chemical structures enriched in our screens was the anthraquinones/quinones (redox-related to catechols) and tetracyclines. Anthraquinones were previously observed to inhibit tau aggregation [33] and quinones were reported to inhibit insulin oligomerization as well as fibril formation [34]. With respect to tetracycline, our screen revealed that several variants were active in amyloid inhibition. This class of compounds was reported to inhibit Aβ and β2-microglobulin amyloid fibrils [35,36].

3.2. Secondary validation of inhibitor candidates

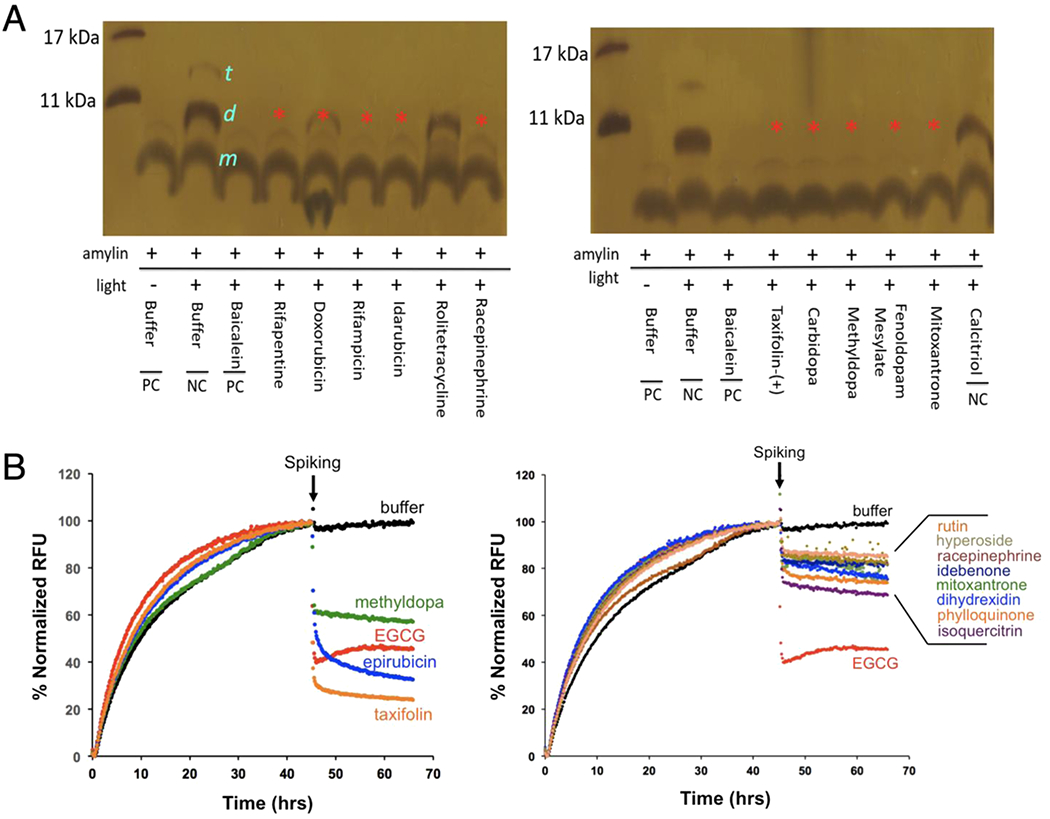

Fluorescence-based ThT or ThS aggregation assay is a commonly used primary screening assay for identification of amyloid inhibitors [33,37,38]. Multiple secondary assays are necessary to exclude occasional false positives [39] and to minimize potential compounding factors in the complex situations that different polymorphic fibrils may exhibit distinct binding activity to ThT. For inhibitor candidates against amylin amyloid, the majority of the catechols and quinones/anthraquinones (16 out of 22 drugs) were further validated by an orthogonal biochemical assay, photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP), which identified cross-linked oligomers (dimers and trimers; Fig. 2A and S1B), or by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Fig. 1C and S1C). For 2N4R tau aggregation inhibitor screen hits, a majority of them were further validated by a ThT fluorescence-based tau amyloid remodeling assay, accomplished by spiking testing compounds into pre-formed tau amyloids (Fig. 2B; Table S2). The concept of “amyloid remodeling” was proposed in the literature and defined as “the compound/inhibitor directly binds to β-sheet-rich aggregates and mediates the conformational change without their disassembly into monomers or small diffusible oligomers as exemplified by the case of EGCG [19,21,40]. Taxifolin, epirubicin, methyldopa showed relatively strong inhibitory activities, similar to the known inhibitor EGCG. Rutin, hyperoside, racepinephrine, idebenone, mitoxantrone, dihydrexidin, phylloquinone, and isoquercitrin displayed relatively weak activities based on our fluorescence-based tau remodeling assays (Fig. 2B). For Aβ amyloid inhibition, total 19 out of 22 catechols and quinones/anthraquinones exhibited significant inhibition against Aβ amyloid, with nine of them validated previously by assays including TEM and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Secondary validation of selected top hits of catechols and quinones/anthraquinones from NIHCC library. (A) Secondary validation of amylin amyloid inhibitor hits by PICUP analysis. Amylin concentration was 30 μM and compound to amylin molar ratio was 5:1. Buffer and two drugs, rolitetracycline and calcitriol, were used as negative controls. Sizes of amylin monomer (”m”), dimer (“d”), and trimer (“t”) are indicated. Baicalein served as a positive control [27]. Absence (or reduced intensity in the case of doxorubicin) of dimer formation bands (red asterisks) indicates their significant activities in blocking amylin oligomer formation. (B) Secondary validation of selected tau amyloid inhibitors by ThT fluorescence-based remodeling assay. Tau 2N4R isoform concentration was 30 μM and compound to tau 2N4R molar ratio was 2:1. Drugs are spiked at the indicated time (black arrows). Buffer (black lines) was used as a negative control. EGCG (red lines) served as a positive control. Compounds with strong remodeling effects were shown in the left panel and compounds with moderate remodeling effects were shown in the right panel.

One commonly used in vitro characterization/validation of amyloid inhibitor is the quantitation of IC50 based on dose dependence analysis. We have characterized several catechol-containing compounds, including baicalein and rosmarinic acid (RA) [5,27]. Baicalein was determined that the apparent IC50 was estimated to be 1 μM under the condition of 10 μM amylin in 1X DPBS buffer [27]. RA was estimated to have an IC50 between 200 and 300 nM, more potent than control EGCG (IC50 = 1 μM) [5]. We also performed cell-based validation of selected catechol-containing compounds for their neutralizing effects on protein amyloid-induced cytotoxicity. Baicalein neutralized amylin-induced cytotoxicity in INS-1 β-cells in a dose-dependent fashion whereas RA showed significant cell rescue effect against amylin-amyloid-induced cytotoxicity in both pancreatic INS-1 cells and neuronal Neuro2A cells [5,27].

3.3. In vivo efficacy studies of a selected catechol for further validation

To further validate our screening results and to demonstrate proof-of-principle in vivo efficacies of identified inhibitors, we selected one catechol-containing compound RA and performed in vivo animal studies. HIP rats had been established as an excellent model to study amylin-amyloid-induced islet pathology and to test novel inhibitors in the prevention and treatment of T2D and related complications [41–43]. Hemizygous HIP rats spontaneously developed midlife diabetes (6 –12 month of age) associated with islet amyloids [44]. To test RA’s effects in reducing amylin amyloid oligomer in rat serum, in pancreatic amyloid deposition, and in ameliorating islet diabetic pathology, we carried out in vivo efficacy tests in hemizygous HIP rats via diet supplementation of RA at a dose of 0.5% (w/w). The dose was chosen based on literature where several phenolic compounds were tested against Aβ amyloids in Tg2576 mice and showed in vivo efficacies [45]. The dietary treatment was initiated at prediabetic stage (at the age of 6 month) [44], and the treatment lasted for 4 months. Due to significantly delayed of phenotype in female rats, only male HIP rats were used [43].

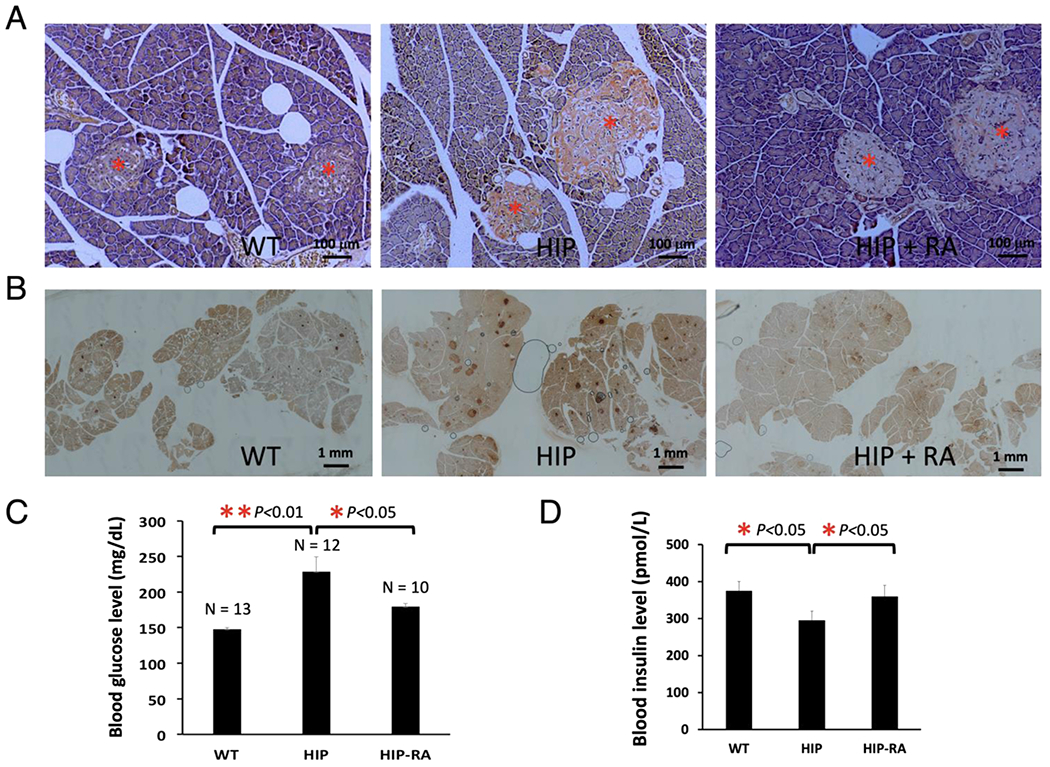

RA showed strong efficacies in anti-amyloid formation and anti-diabetic activities in vivo that were consistent with its strong in vitro activities [5]: (I) As expected, diabetic HIP rats (at the age of 10 –12 month) showed severe amylin amyloid deposition in the pancreatic islets as visualized by Congo Red staining (Fig. 3A, middle panel). The extensive amyloid islet deposition was reminiscent of a clinical ThS staining of the islets from a human with T2D [26]. In contrast, wild-type age-matched Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats showed no amyloid deposition in the islets (Fig. 3A, left panel). Amylin amyloid deposition in islets was significantly reduced in RA-treated, age-matched HIP rats (Fig. 3A, right panel); however, residual amyloid deposition was evident, suggesting that RA treatment regimen did not completely block amylin aggregation and deposition on the pancreas. (II) Immunohistochemistry analysis of islet tissues provided additional evidence that amylin deposition levels were significantly higher in the islets of untreated HIP rats (stained in dark brown; Fig. 3B, middle panel) in comparison with those of wild-type SD rats (Fig. 3B, left panel) and RA-treated HIP rats (Fig 3B, right panel). (III) We further evaluated diabetic pathology of each group of rats. Wild-type SD rats have an average nonfasting blood glucose level of 146.8 mg/dL. Untreated HIP rats have an average nonfasting blood level of 242.3 mg/dL that is highly diabetic. Such spontaneous diabetes development in HIP rats and hyperglycemia are consistent with what have been reported [44,46]. Remarkably, RA-treated HIP rats have a significantly reduced average nonfasting blood glucose level of 181.0 mg/dL (Fig. 3C). Consistently, serum insulin levels were significantly lower in untreated HIP rats than those in wild-type SD rats or RA-treated HIP rats at the age of 10 months (Fig. 3D). Hypoinsulinemia state of HIP rats at this age had been reported [42]. We do not find any significant differences between RA-treated versus nontreatment HIP groups on body weight and food intake (data not shown). (IV) In further collaboration with current data, we evaluated amylin oligomer levels in HIP rat blood by Western blots using amylin-specific antibody T-4157 in recently published work [5]. Sera samples from untreated HIP rats showed strong intensities of amylin oligomers (estimated to be 32 and 52 kDa, respectively), whereas corresponding amylin oligomer levels in RA-treated HIP rats were either significantly reduced (52 kDa band) or fully abrogated (32 kDa band). RA also showed efficacies in ex vivo experiments with HIP rat blood samples and diabetic human sera samples at μM concentration of dosage [5].

Fig. 3.

Animal studies demonstrated that RA strongly reduced amylin amyloid islet deposition and ameliorated diabetic pathology in transgenic diabetic HIP rats. Prediabetic HIP rats (6-month-old) were treated (HIP+RA) or untreated (HIP) with dietary supplementation of 0.5% (w/w) RA in regular chow diet for 4 months. Age-matched wild-type Sprague–Dawley rats with regular chow diet served as negative controls (WT). At the end of the treatments, rats were euthanized, and pancreatic tissues and sera were collected for immunohistochemistry and biochemical analysis. (A) Representative Congo red staining demonstrated strong amyloid staining in untreated HIP rat pancreatic tissue slices (orange-red color in the islets, middle panel). Congo red staining was significantly reduced in the islets of RA-treated HIP rats with only residue staining remaining (right panel). No Congo red staining was observed in islets in control wild-type SD rats (left panel). All pancreatic islets are marked by red asterisks. These qualitative results represent multiple samples from RA-treated or untreated HIP rats or WT Sprague–Dawley controls (n = 4), and at least 50 islets from pancreatic head, body, and tail for each group were examined. Scale bar in each panel is 100 μm. (B) Representative amylin deposition in the pancreatic tissue slice using amylin antibody staining from different rat groups. Pancreatic tissue slices were stained with amylin-specific antibody (T-4157) followed by secondary antibody and NovaRED substrate (Vector Lab) treatment. Stained islets are shown in dark brown color. Islets in the pancreatic slices from untreated HIP rats were intensely stained, whereas those from RA-treated and control SD rats were only weakly stained. At least 10 tissue slices were observed from each group. Scale bar in each panel as indicated is 1 mm. (C) Serum glucose levels were quantified for each group of rats. Significant reduction of serum glucose concentration was observed, indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) comparing the untreated HIP rats with those of RA-treated HIP rats or control SD rats. (D) Insulin levels were measured for each group of rats. Statistically lower levels of insulin were observed and indicated by asterisks (p < 0.05) comparing the untreated HIP rats with those of RA-treated HIP rats or control SD rats (n = 4).

3.4. Redox state is a key determinant of the inhibitory activities

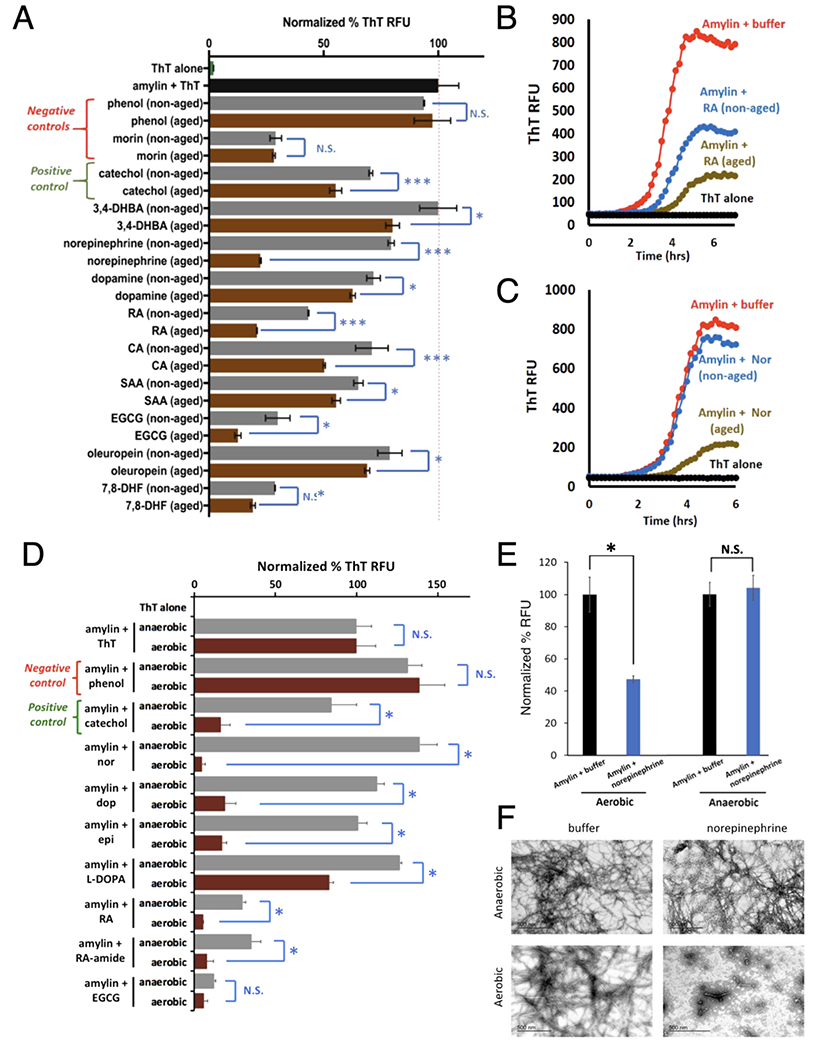

Based on the fact that catechol-containing compounds and multiple anthraquinone/quinone compounds (redox related to catechols) exhibited strong anti-amyloid activities, we hypothesized that catechol autoxidation may be part of the general mechanism that significantly enhances the anti-amyloid activities of the catechol-containing compounds. To test this hypothesis, we compared the anti-amyloid activities of a collection of oxidized (or “aged” - exposed to the air for 48 h) with non-oxidized (“non-aged” or freshly prepared) catechol-containing compounds. In virtually all cases, aged samples exhibited significantly greater activities than their identically prepared non-aged counterparts (Fig. 4A). Oxidation-induced activity enhancement was not observed with phenol nor a structurally similar but non-catechol amyloid inhibitor, morin. These combined results strongly suggested a catechol-dependent enhancement specificity, which was recapitulated under stringently defined aerobic/anaerobic conditions using an anaerobic chamber. Aerobic, but not anaerobic conditions, significantly enhanced anti-amyloid activities of several catecholamines and other catechol-containing inhibitors (Fig. 4D). The kinetic profiles of ThT fluorescence-based amylin amyloid inhibition showed significantly stronger inhibition with aged RA versus non-aged RA, with an even more dramatic inhibition activity enhancement was observed with aged norepinephrine (Fig. 4B & C). Consistently, enhanced inhibition by norepinephrine occurred only under aerobic conditions (Fig. 4E), with marked reduction in fibril formation (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Autoxidation (or aerobic exposure), but not anaerobic conditions, significantly enhanced anti-amyloid activities associated with catechol-containing compounds. (A) Aged catechol-containing compounds (in brown), but not negative controls phenol (a non-inhibitor) or morin (an amylin amyloid inhibitor but with no catechol moiety) display enhanced anti-amyloid activities compared to their non-aged counterparts (in grey). All aged and non-aged treated amylin aggregation reactions were normalized to buffer treated amylin controls (black bar) indicated by the dashed red line. Abbreviations: 7,8-dihydroxy flavone (7,8-DHF), rosmarinic acid (RA), caffeic acid (CA), salvanic acid A (SAA), 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (3,4-DHBA). Statistics were conducted using one-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons test; * p < 0.05 or *** p < 0.01. (B,C) Representative ThT fluorescence assay time course of aged versus non-aged RA (panel B) and norepinephrine (panel C) treatments in amylin aggregations reactions shown in panel A. (D) Catechol-containing compounds (in brown), showed significantly higher anti-amyloid activities under aerobic exposure compared to their anaerobic condition treated counterparts (in grey). All aerobic exposed and anaerobic condition treated amylin aggregation reactions were normalized to buffer treated amylin controls (amylin + ThT). Phenol served as a negative control and catechol as a positive control. Abbreviations: norepinephrine: nor; dopamine: dop; epinephrine: epi; rosmarinic acid: RA; rosmarinic acid analog with an amide link, RA-amide; epigallocatechin gallate, EGCG. Statistics were conducted using one-way ANOVA, multiple comparisons test; * p < 0.05. (E,F) ThT and TEM assays confirm that the anti-amylin amyloid activities of norepinephrine require aerobic exposure. Notice lack of fibril presence under aerobic condition with norepinephrine treatment.

Multiple small molecule amyloid inhibitors, many of which are catechol-containing polyphenols, perturb or “remodel” unaggregated and/or pre-aggregated amyloid species into denaturant-resistant aggregates that displayed broad-range molecular weights; characterized as “smear-type” distributions on SDS-PAGE gels [19,21,28,40]. Using RA and norepinephrine as two representative cases, treatment with a reducing reagent such as cysteine nearly eliminated their amyloid remodeling activities in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5A & 5B). Similar effect was observed with glutathione, cystamine, and TCEP as well, and importantly, with other catechol-containing compounds including epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and dopamine, but not negative controls phenol and a non-catechol amyloid inhibitor, curcumin (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Blockage of amyloid remodeling activities of selective catechol-containing inhibitors by reducing agents. (A) Dose response effects of reducing agents cysteine, glutathione, and cysteamine on inhibiting RA (panel A) and norepinephrine (panel B) amyloid remodeling activities. Two different doses, 100 μM and 450 μM of reducing agents were used. (C) Control experiments demonstrate that reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) completely prevented the remodeling activities of amylin amyloid by catechol-containing inhibitors EGCG and dopamine but by neither a negative control, phenol, nor non-catechol inhibitor, curcumin. Amylin concentration used was 15 μM. The concentrations of reducing agent to inhibitors or control were 10:1 molar ratio (i.e., 450 μM TCEP, 45 μM of phenol, EGCG, or dopamine). In all panels, positive remodeling activities are highlighted in blue boxes and negative or mitigated remodeling activities are indicated by red asterisks.

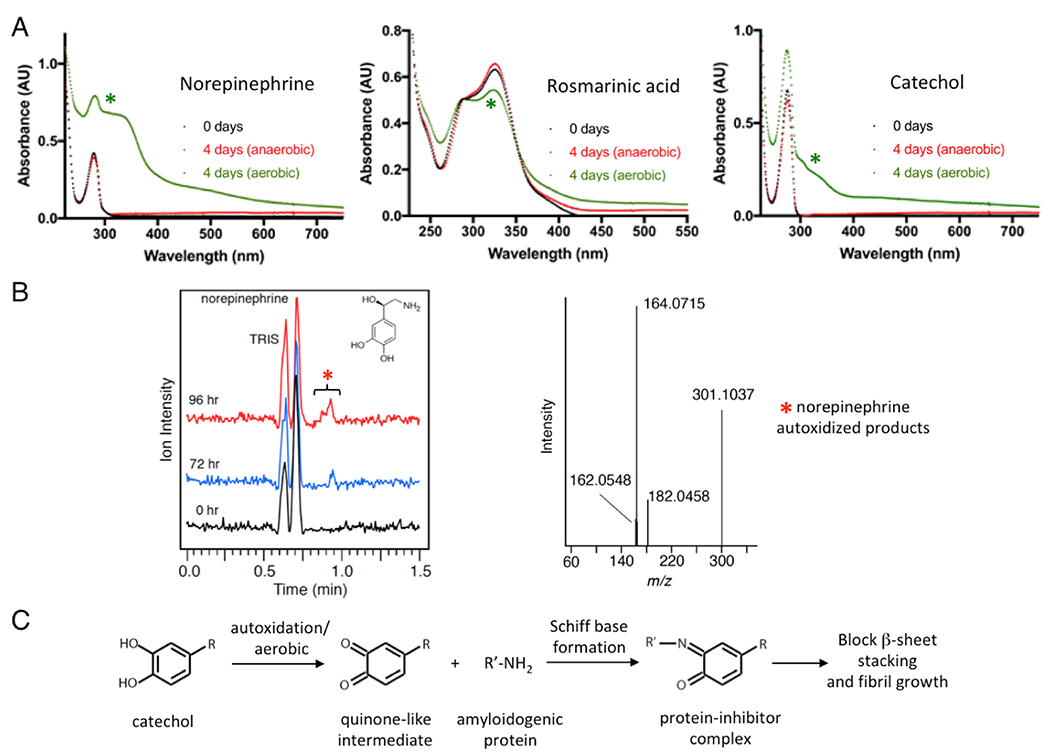

3.5. Characterization of selected autoxidized catechol-containing compounds

The chemical changes that occur during autoxidation were investigated by both UV-Vis and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) approaches. UV-Vis time course spectra confirmed that chemical changes were only detectable under aerobic conditions, and occurred coincidently with their enhanced anti-amyloid activities (Fig 6A; highlighted by green asterisks). Such chemical changes were reflected in broad UV absorption spectra changes, particularly in the region of 300–350 nm (Fig. 6A). In an effort to identify the oxidized chemical species that contribute to the enhanced amyloid inhibition, we performed LC-MS analyses of aged norepinephrine. New species/peaks with increasing ion intensities over time (elution was collected at 0–96 h) were detected in LC at the elution time between 0.85 min and 1.0 min (Fig 6B). High-resolution MS identified four main ions within the norepinephrine sample (m/z peaks at 162.0548, 164.0715, 182.0458, and 301.1037 in Fig. 6B). While the known oxidized product of norepinephrine, noradrenochrome (C8H5NO3, 164.0342, [M+H]+) was the anticipated product [47,48], the mass difference of 0.0373 from the observed 164.0715 does not support its presence. Thus, all species remain unidentified. These ions may result from the acidic conditions of the LC separation as well as in-source reactions that may occur during the ionization process. Hence the features observed by LC-MS are presently considered signatures of the oxidation process and not the inhibitory species present in solution at neutral buffered pH. Nonetheless, these ions were present in the time course of autoxidation that correlate with norepinephrine anti-amyloid activities as exhibited by both ThT and TEM assays (Fig. 4E & 4F). These data agree well with studies that showed catecholamine oxidation products were effective anti-amyloidogenic agents against α-synuclein and tau [49,50]. Collectively, our data demonstrate that autoxidation is a general pathway enhancing the anti-amyloid activities of catechol-containing compounds (Fig. 6C). In supporting this covalent inhibition model, we demonstrated the covalent conjugate adduct by high-resolution mass spectrometry in our specific investigation on baicalein [27]. Redox state is therefore a key factor that modulates the activities of a large number of catechol-containing amyloid inhibitors.

Fig. 6.

UV-Vis and LC-MS characterization of oxidized products of selected catechols and model for amyloid inhibition by autoxidized catechol compounds. (A) Significant oxidative changes incurred for norepinephrine, rosmarinic acid, and catechol with 4 days exposure to aerobic condition, but not in anaerobic condition, in UV-Vis absorption spectra (indicated by green asterisks). (B) Freshly dissolved (time 0) or aged norepinephrine samples (72 or 96 h) were characterized by LC-MS. Visual inspection of the chromatograms showed a new peak (highlighted by red asterisk) at 0.85 – 1.0 min in the 72 and 96 h sample that was not present at 0 h. MS (positive mode) of this fraction identifies three species that are likely norepinephrine oxidized byproducts that include [M+H+] 164.0715, 182.0458 and 182.0458. (C) A general model of how autoxidation or aerobic conditions enhance the activities of catechol-containing protein amyloid inhibitors, as we originally proposed in our specific investigation on baicalein [27].

4. Discussion

Catechol-containing compounds identified from our screens included two catecholamines, dopamine and norepinephrine. Dopamine and norepinephrine are two physiological neurotransmitters and hormones with many important physiological functions. As a neurotransmitter, dopamine is involved in neurological functions such as movement, memory, pleasurable reward and motivation. High or low dopamine levels are associated with diseases including Parkinson’s, restless leg syndrome, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Norepinephrine plays important roles in body’s “fight-or-flight” responses under stress conditions to increase blood flow and pressure as a hormone, and increases alertness, arousal, and attention as a neurotransmitter. Normal range for dopamine and norepinephrine concentrations in blood are estimated to be 0–0.196 nM for dopamine and 0.414–10.0 nM for norepinephrine [51]. In brain, dopamine concentration is 4.8 ± 1.5 nM in the ventral tegmental area, where it is produced, while in red nucleus, it is 0.5 ± 1.5 nM [52]. In rat brain, norepinephrine concentration is 2.09 nM in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens [53]. It is currently unclear but is of significant interest to investigate if low nM physiological concentrations of dopamine and norepinephrine can elicit any effects in prevention of protein amyloid formation.

A variety of covalent mechanisms can readily explain the observed effects of autoxidation for catechol-mediated remodeling and the corresponding strong stability of the observed remodeled aggregates. Free radical cycling occurring during catechol autoxidation could directly cycle through nearby interacting amyloid proteins that subsequently lead to protein-protein and/or protein-compound adducts [54]. Alternatively, remodeled aggregates may also form through covalent interactions between electrophilic o-quinone oxidized byproducts of catechol parent compounds and amyloid protein side chain amines [20,27,31,49,54–56]. Regardless of the exact mechanism, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that the presence of oxygen facilitates autoxidation, which in turn enables catechol-containing compounds to engage in amyloid remodeling activities that leads to what are presumably innocuous off-pathway, non-toxic aggregates [19,21,28,40]. It remains to be determined whether amyloid remodeling is merely phenomenological in nature or if it represents a key mechanism essential for inhibitor-mediated anti-amyloid activities. Built from previous work [5,16,27,28,32,33,49,54,55], our data suggest that (i) catechol-containing compounds as well as redox related anthraquinones represent a broad class of amyloid inhibitors capable of targeting amyloid from multiple sequence-unrelated amyloidogenic proteins, and (ii) the redox states of catechol-containing compounds are a key determinant of their anti-amyloid activities.

We and several other research groups have shown that catechol groups in the catechol-containing polyphenols and flavonoids play key roles in amyloid inhibition [5,27,28,30,31,50]. Significantly beyond from individual compounds, we have shown here systematically that catechols and redox-related quinones/anthraquinones are a broad class of amyloid inhibitors. To our knowledge, identification of a class of compounds using systematic screens against multiple prototype amyloidogenic proteins has not been reported. The catechol moiety is a common structural component of many natural products, broadly classified as polyphenols, many of which have anti-amyloid and anti-aging activities [16,23,57,58]. Our results thus provide mechanistic insight into why this class of large number of natural compounds, often enriched in healthy diet, is active in neutralizing toxic amyloids, suggesting a combination of redox and structural modeling is a viable path to new anti-amyloid structures with enhanced activities. Catechol-containing natural products offer the advantage of low cost and potentially low side effects, inasmuch offering significant potential as anti-neurodegeneration, anti-aging nutraceuticals.

Catechol and related quinone motifs are classified by Baell et al. as Pan Assay INterference compounds (or PAINS) in drug discovery [59–61]. However, validity of such overly broad classification is debatable as the authors conceded that about 5% of FDA-approved drugs contain PAINS-recognized substructures [61]. For an example, EGCG, a well-established amyloid inhibitor [19,21,40] that has undergone numerous clinical trials, falls into the PAINS category, because it contains the catechol motif. Nevertheless, caution has been exercised in our work to validate with multiple orthogonal in vitro and cell-based assays. ThT fluorescence assays for example, one of the most commonly used assays for screening amyloid inhibitors, could lead to false positives with certain hydroxyflavones or competitive binding on fibrils [39,62]. Orthogonal secondary assays, such as TEM analysis, PICUP, and cell-based assays, allowed us to follow up on the hits generated from ThT fluorescence-based primary screenings, minimizing such false positives.

Multiple structural studies suggest that there are different conformers and/or molecular polymorphism in multiple amyloidogenic proteins including amylin, Aβ, tau, α-synuclein, and TDP-43 [12,63–68]. Moreover, many studies indicate that unique amyloid conformers may faithfully propagate morphologically and biochemically between cells and tissues, in a prion-like manner [69–71]. These experimental observations suggest that the accumulation and assembly of various protein aggregates in many protein misfolding diseases is not totally driven by the amino acid sequences of aggregation-prone molecules; instead, they may be governed by the precise cellular and pathological environment of aggregation conditions. It will be interesting to identify different conformers, key environmental factors, protein modifications, and correlate them with their cytotoxicity. Such structure and function classification will greatly facilitate the identification of specific pharmacophores for structure-based inhibitor design in the future.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we applied a molecular screening platform and identified catechol-containing compounds as a broad class of protein aggregation inhibitors against three prototypes of amyloidogenic proteins. Beyond validation of identified catechol compounds with multiple secondary assays, we demonstrated in vivo efficacies of rosmarinic acid, a selected catechol-containing compound, in reducing amylin amyloid pancreatic deposition and ameliorating diabetic pathology in HIP rat model. We further discovered that the redox state is a key determinant of this broad class of aggregation inhibitor activities as part of a covalent conjugation mechanism. These molecular mechanistic insights not only explain why a large number of catechol-containing natural compounds, often enriched in healthy diet, have anti-neurodegeneration and anti-aging activities, but also could guide the rational design of therapeutic or nutraceutical strategies to target a broad range of increasingly prevalent neurodegenerative and related proteinopathies aging diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Kathy Lowe at Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine for her excellent technical assistance in collecting TEM data. We thank Shradha Lad for assistance with 2N4R tau recombinant protein purification. We thank Virginia Tech Center for Drug Discovery and Dr. Pablo Sobrado for instrument and NIHCC library access. We thank Prof. Jianyong Li for constructive discussions.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R03AG061531 (BX), R01AG067607 (BX), and R01AG058673 (SZ), Alzheimer’s Association/Michael J. Fox Foundation grant BAND-19-614848 (BX), Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 20150601 (SZ), the Hatch Program of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA (BX and RFH), Commonwealth Health Research Board Grant 208-01-16 (BX and SZ), Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation Grant #497 (BX), and the Alzheimer’s and Related Diseases Research Award Fund of the Commonwealth of Virginia (Awards No. 16-1, 18-2 and 18-4 to BX, LW, and SZ).

Abbreviations:

- 3,4-DHBA

3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- 7,8-DHF

7,8-dihydroxy flavone

- Aβ

amyloid β-peptide

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- CA

caffeic acid

- EGCG

epigallocatechin gallate

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- NIHCC

the NIH Clinical Collection library

- Nor

norepinephrine

- PICUP

photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins

- RA

rosmarinic acid

- RFU

relative fluorescence unit

- SAA

salvanic acid A

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- ThT

thioflavin T

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106409.

Data Availability

Data will be made available upon request.

References

- [1].Westermark P, Andersson A, Westermark GT, Islet amyloid polypeptide, islet amyloid, and diabetes mellitus, Physiol. Rev 91 (2011) 795–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Knowles TPJ, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15 (2014) 384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chiti F, Dobson CM, Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade, Annu Rev. Biochem 86 (2017) 27–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang Z, Manca M, Foutz A, Camacho MV, Raymond GJ, Race B, Orru CD, Yuan J, Shen P, Li B, Lang Y, Dang J, Adornato A, Williams K, Maurer NR, Gambetti P, Xu B, Surewicz W, Petersen RB, Dong X, Appleby BS, Caughey B, Cui L, Kong Q, Zou WQ, Early preclinical detection of prions in the skin of prion-infected animals, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wu L, Velander P, Brown AM, Wang Y, Liu D, Bevan DR, Zhang S, Xu B, Rosmarinic acid potently detoxifies amylin amyloid and ameliorates diabetic pathology in a transgenic rat model of type 2 diabetes, ACS Pharm. Transl. Sci 4 (4) (2021) 1322–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Eisenberg D, Jucker M, The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases, Cell 148 (2012) 1188–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Selkoe DJ, Hardy J, The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years, EMBO Mol. Med 8 (2016) 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li C, Gotz J, Tau-based therapies in neurodegeneration: opportunities and challenges, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16 (2017) 863–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW, Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease, Nature 547 (2017) 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Krotee P, Rodriguez JA, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Reyes FE, Shi D, Hattne J, Nannenga BL, Oskarsson ME, Philipp S, Griner S, Jiang L, Glabe CG, Westermark GT, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS, Atomic structures of fibrillar segments of hIAPP suggest tightly mated β-sheets are important for cytotoxicity, Elife (2017) 6, 10.7554/eLife.19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li B, Ge P, Murray KA, Sheth P, Zhang M, Nair G, Sawaya MR, Shin WS, Boyer DR, Ye S, Eisenberg DS, Zhou ZH, Jiang L, Atomic structures of fibrillar segments of hIAPP suggest tightly mated β-sheets are important for cytotoxicity, Elife (2017), 6, 10.7554/eLife.19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Seidler PM, Boyer DR, Rodriguez JA, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Murray K, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS, Structure-based inhibitors of tau aggregation, Nat. Chem 10 (2018) 170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Spanopoulou A, Heidrich L, Chen HR, Frost C, Hrle D, Malideli E, Hille K, Grammatikopoulos A, Bernhagen J, Zacharias M, Rammes G, Kapurniotu A, Designed macrocyclic peptides as nanomolar amyloid inhibitors based on minimal recognition elements, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 57 (2018) 14503–14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Griner SL, Seidler P, Bowler J, Murray KA, Yang TP, Sahay S, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Rodriguez JA, Philipp S, Sosna J, Glabe CG, Gonen T, Eisenberg DS, Structure-based inhibitors of amyloid beta core suggest a common interface with tau, Elife 8 (2019), e46924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Armiento V, Hille K, Naltsas D, Lin JS, Barron AE, Kapurniotu A, The human host-defense peptide cathelicidin LL-37 is a nanomolar inhibitor of amyloid self-assembly of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 59 (2020) 12837–12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Velander P, Wu L, Henderson F, Zhang S, Bevan DR, Xu B, Natural product-based amyloid inhibitors, Biochem Pharm. 139 (2017) 40–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Armiento V, Spanopoulou A, Kapurniotu A, Peptide-based molecular strategies to interfere with protein misfolding, aggregation, and cell degeneration, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 59 (2020) 3372–3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johnson SM, Connelly S, Fearns C, Powers ET, Kelly JW, The transthyretin amyloidoses: from delineating the molecular mechanism of aggregation linked to pathology to a regulatory-agency-approved drug, J. Mol. Biol 421 (2012) 185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, Herbst M, Masino L, Lurz R, Engemann S, Pastore A, Wanker EE, EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 15 (2008) 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hong DP, Fink AL, Uversky VN, Structural characteristics of alpha-synuclein oligomers stabilized by the flavonoid baicalein, J. Mol. Biol 383 (2008) 214–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, Ehrnhoefer DE, Wobst H, Neugebauer K, Wanker EE, EGCG remodels mature α-synuclein and amyloid-β fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107 (2010) 7710–7715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jha NN, Ghosh D, Das S, Anoop A, Jacob RS, Singh PK, Ayyagari N, Namboothiri IN, Maji SK, Effect of curcumin analogs on alpha-synuclein aggregation and cytotoxicity, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 28511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cao P, Raleigh DP, Analysis of the inhibition and remodeling of islet amyloid polypeptide amyloid fibers by flavanols, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 2670–2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brumshtein B, Esswein SR, Salwinski L, Phillips ML, Ly AT, Cascio D, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg DS, Inhibition by small-molecule ligands of formation of amyloid fibrils of an immunoglobulin light chain variable domain, Elife 4 (2015), e10935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Tau pathology and neurodegeneration, Lancet Neurol. 12 (2013) 609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Verchere CB, D’Alessio DA, Palmiter RD, Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S, Baskin DG, Kahn SE, Islet amyloid formation associated with hyperglycemia in transgenic mice with pancreatic beta cell expression of human islet amyloid polypeptide, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 (1996) 3492–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Velander P, Wu L, Ray WK, Helm RF, Xu B, Amylin amyloid inhibition by flavonoid baicalein: key roles of its vicinal dihydroxyl groups of the catechol moiety, Biochemistry 55 (2016) 4255–4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu L, Velander P, Liu D, Xu B, Olive component oleuropein promotes beta-cell insulin secretion and protects beta-cells from amylin amyloid-induced cytotoxicity, Biochemistry 56 (2017) 5035–5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wu L, Wang Z, Ladd S, Dougharty DT, Marcus M, Henderson F, Gilyazova N, Ray WK, Siedlak S, Li J, Helm RF, Zhu X, Bloom GS, Wang SJ, Zou WQ, Xu B, Selective detection of misfolded tau from post-mortem Alzheimer’s diease brains, Front Aging Neurosci. 14 (2022), 945875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Caruana M, Högen T, Levin J, Hillmer A, Giese A, Vassallo N, Inhibition and disaggregation of a-synuclein oligomers by natural polyphenolic compounds, FEBS Lett. 585 (2011) 1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sato M, Murakami K, Uno M, Nakagawa Y, Katayama S, Akagi K, Masuda Y, Takegoshi K, Irie K, Site-specific inhibitory mechanism for amyloid beta42 aggregation by catechol-type flavonoids targeting the Lys residues, J. Biol. Chem 288 (2013) 23212–23224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Joshi P, Chia S, Habchi J, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, Fragment-Based A, Method of creating small-molecule libraries to target the aggregation of intrinsically disordered proteins, ACS Comb. Sci 18 (2016) 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pickhardt M, Gazova Z, von Bergen M, Khlistunova I, Wang Y, Hascher A, Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Mandelkow E, Anthraquinones inhibit tau aggregation and dissolve Alzheimer’s paired helical filaments in vitro and in cells, J. Biol. Chem 280 (2005) 3628–3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gong H, He Z, Peng A, Zhang X, Cheng B, Sun Y, Zheng L, Huang K, Effects of several quinones on insulin aggregation, Sci. Rep 4 (2014) 5648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Forloni G, Colombo L, Girola L, Tagliavini F, Salmona M, Anti-amyloidogenic activity of tetracyclines: studies in vitro, FEBS Lett. 487 (2001) 404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Giorgetti S, Raimondi S, Pagano K, Relini A, Bucciantini M, Corazza A, Fogolari F, Codutti L, Salmona M, Mangione P, Colombo L, De Luigi A, Porcari R, Gliozzi A, Stefani M, Esposito G, Bellotti V, Stoppini M, Effect of tetracyclines on the dynamics of formation and destructuration of beta2-microglobulin amyloid fibrils, J. Biol. Chem 286 (2011) 2121–2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Xue C, Lin TY, Chang D, Guo Z, Thioflavin T as an amyloid dye: fibril quantification, optimal concentration and effect on aggregation, R. Soc. Open Sci 4 (2017), 160696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Crowe A, Huang W, Ballatore C, Johnson RL, Hogan AM, Huang R, Wichterman J, McCoy J, Huryn D, Auld DS, Smith AB 3rd, Inglese J, Trojanowski JQ, Austin CP, Brunden KR, Lee VM, Identification of aminothienopyridazine inhibitors of tau assembly by quantitative high-throughput screening, Biochemistry 48 (2009) 7732–7745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Noor H, Cao P, Raleigh DP, Morin hydrate inhibits amyloid formation by islet amyloid polypeptide and disaggregates amyloid fibers, Protein Sci. 21 (2012) 373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Palhano FL, Lee J, Grimster NP, Kelly JW, Toward the molecular mechanism (s) by which EGCG treatment remodels mature amyloid fibrils, J. Am. Chem. Soc 135 (2013) 7503–7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Matveyenko AV, Butler PC, Islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) transgenic rodents as models for type 2 diabetes, ILAR J. 47 (2006) 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Matveyenko AV, Butler PC, Beta-cell deficit due to increased apoptosis in the human islet amyloid polypeptide transgenic (HIP) rat recapitulates the metabolic defects present in type 2 diabetes, Diabetes 55 (2006) 2106–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ly H, Verma N, Wu F, Liu M, Saatman KE, Nelson PT, Slevin JT, Goldstein LB, Biessels GJ, Despa F, Brain microvascular injury and white matter disease provoked by diabetes-associated hyperamylinemia, Ann. Neurol 82 (2017) 208–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Butler AE, Jang J, Gurlo T, Carty MD, Soeller WC, Butler PC, Diabetes due to a progressive defect in beta-cell mass in rats transgenic for human islet amyloid polypeptide (HIP Rat): a new model for type 2 diabetes, Diabetes 53 (2004) 1509–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hamaguchi T, Ono K, Murase A, Yamada M, Phenolic compounds prevent Alzheimer’s pathology through different effects on the amyloid-beta aggregation pathway, Am. J. Pathol 175 (2009) 2557–2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Srodulski S, Sharma S, Bachstetter AB, Brelsfoard JM, Pascual C, Xie XS, Saatman KE, Van Eldik LJ, Despa F, Neuroinflammation and neurologic deficits in diabetes linked to brain accumulation of amylin, Mol. Neurodegener 9 (2014) 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jimenez M, Garcia-Canovas F, Garcia-Carmona F, Lozano JA, Iborra JL, Kinetic study and intermediates identification of noradrenaline oxidation by tyrosinase, Biochem. Pharmacol 33 (1984) 3689–3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Manini P, Panzella L, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M, Oxidation chemistry of norepinephrine: partitioning of the O-quinone between competing cyclization and chain breakdown pathways and their roles in melanin formation, Chem. Res. Toxicol 20 (2007) 1549–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Li J, Zhu M, Manning-Bog AB, Di Monte DA, Fink AL, Dopamine and L-dopa disaggregate amyloid fibrils: implications for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, FASEB J. 18 (2004) 962–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Soeda Y, Yoshikawa M, Almeida OFX, Sumioka A, Maeda S, Osada H, Kondoh Y, Saito A, Miyasaka T, Kimura T, Suzuki M, Koyama H, Yoshiike Y, Sugimoto H, Ihara Y, Takashima A, Toxic tau oligomer formation blocked by capping of cysteine residues with 1,2-dihydroxybenzene groups, Nat. Commun 6 (2015) 10216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chernecky CC, Berger BJ, Catecholamines - plasma, in: Chernecky CC, Berger BJ (Eds.), Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures, sixth ed., Elsevier Saunders, St Louis, MO, 2013, pp. 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Slaney TR, Mabrouk OS, Porter-Stransky KA, Aragona BJ, Kennedy RT, Chemical gradients within brain extracellular space measured using low flow push-pull perfusion sampling in vivo, ACS Chem. Neurosci 4 (2013) 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Léna I, Parrot S, Deschaux O, Muffat-Joly S, Sauvinet V, Renaud B, Suaud-Chagny MF, Gottesmann C, Variations in extracellular levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate, and aspartate across the sleep–wake cycle in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats, J. Neurosci. Res 81 (2005) 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Meng X, Munishkina LA, Fink AL, Uversky VN, Molecular mechanisms underlying the flavonoid-induced inhibition of alpha-synuclein fibrillation, Biochemistry 48 (2009) 8206–8224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhu M, Rajamani S, Kaylor J, Han S, Zhou F, Fink AL, The flavonoid baicalein inhibits fibrillation of alpha-synuclein and disaggregates existing fibrils, J. Biol. Chem 279 (2004) 26846–26857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Popovych N, Brender JR, Soong R, Vivekanandan S, Hartman K, Basrur V, Macdonald PM, Ramamoorthy A, Site specific interaction of the polyphenol EGCG with the SEVI amyloid precursor peptide PAP(248-286), J. Phys. Chem. B 116 (2012) 3650–3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ono K, Li L, Takamura Y, Yoshiike Y, Zhu L, Han F, Mao X, Ikeda T, Takasaki J, Nishijo H, Takashima A, Teplow DB, Zagorski MG, Yamada M, Phenolic compounds prevent amyloid β-protein oligomerization and synaptic dysfunction by site-specific binding, J. Biol. Chem 287 (2012) 14631–14643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yamada M, Ono K, Hamaguchi T, Noguchi-Shinohara M, Natural phenolic compounds as therapeutic and preventive agents for cerebral amyloidosis, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 863 (2015) 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Baell JB, Holloway GA, New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays, J. Med. Chem 53 (2010) 2719–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Baell JB, Feeling nature’s PAINS: natural products, natural product drugs, and pan assay interference compounds (PAINS), J. Nat. Prod 79 (2016) 616–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Baell JB, Nissink JWM, Seven year itch: pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) in 2017-utility and limitations, ACS Chem. Biol 13 (2018) 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Suzuki Y, Brender JR, Hartman K, Ramamoorthy A, Marsh EN, Alternative pathways of human islet amyloid polypeptide aggregation distinguished by (19)f nuclear magnetic resonance-detected kinetics of monomer consumption, Biochemistry 51 (41) (2012) 8154–8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wiltzius JJ, Landau M, Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Apostol MI, Goldschmidt L, Soriaga AB, Cascio D, Rajashankar K, Eisenberg D, Molecular mechanisms for protein-encoded inheritance, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 16 (2009) 973–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tycko R, Amyloid polymorphism: structural basis and neurological relevance, Neuron 86 (2015) 632–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Qiang W, Yau WM, Lu JX, Collinge J, Tycko R, Structural variation in amyloid-β fibrils from Alzheimer’s disease clinical subtypes, Nature 541 (2017) 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Guenther EL, Ge P, Trinh H, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Boyer DR, Gonen T, Zhou ZH, Eisenberg DS, Atomic-level evidence for packing and positional amyloid polymorphism by segment from TDP-43 RRM2, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25 (2018) 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cao Q, Boyer DR, Sawaya MR, Ge P, Eisenberg DS, Cryo-EM structures of four polymorphic TDP-43 amyloid cores, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 26 (2019) 619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Arakhamia T, Lee CE, Carlomagno Y, Duong DM, Kundinger SR, Wang K, Williams D, DeTure M, Dickson DW, Cook CN, Seyfried NT, Petrucelli L, Fitzpatrick AWP, Posttranslational modifications mediate the structural diversity of tauopathy strains, Cell 180 (2020) 633–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Frost B, Diamond MI, Prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11 (2010) 155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Watts JC, Condello C, Stöhr J, Oehler A, Lee J, DeArmond SJ, Lannfelt L, Ingelsson M, Giles K, Prusiner SB, Serial propagation of distinct strains of Aβ prions from Alzheimer’s disease patients, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 (2014) 10323–10328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Strang KH, Croft CL, Sorrentino ZA, Chakrabarty P, Golde TE, Giasson BI, Distinct differences in prion-like seeding and aggregation between Tau protein variants provide mechanistic insights into tauopathies, J. Biol. Chem 293 (2018) 2408–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.