Abstract

Background

Sutures (stitches), staples and adhesive tapes have been used for many years as methods of wound closure, but tissue adhesives have entered clinical practice more recently. Closure of wounds with sutures enables the closure to be meticulous, but the sutures may show tissue reactivity and can require removal. Tissue adhesives offer the advantages of an absence of risk of needlestick injury and no requirement to remove sutures later. Initially, tissue adhesives were used primarily in emergency room settings, but this review looks at the use of tissue adhesives in the operating room/theatre where surgeons are using them increasingly for the closure of surgical skin incisions.

Objectives

To determine the effects of various tissue adhesives compared with conventional skin closure techniques for the closure of surgical wounds.

Search methods

In March 2014 for this second update we searched the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL. We did not restrict the search and study selection with respect to language, date of publication or study setting.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted screening of eligible studies, data extraction and risk of bias assessment independently and in duplicate. We expressed results as random‐effects models using mean difference for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. We investigated heterogeneity, including both clinical and methodological factors.

Main results

This second update of the review identified 19 additional eligible trials resulting in a total of 33 studies (2793 participants) that met the inclusion criteria. There was low quality evidence that sutures were significantly better than tissue adhesives for reducing the risk of wound breakdown (dehiscence; RR 3.35; 95% CI 1.53 to 7.33; 10 trials, 736 participants that contributed data to the meta‐analysis). The number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome was calculated as 43. For all other outcomes ‐ infection, patient and operator satisfaction and cost ‐ there was no evidence of a difference for either sutures or tissue adhesives. No evidence of differences was found between tissue adhesives and tapes for minimising dehiscence, infection, patients' assessment of cosmetic appearance, patient satisfaction or surgeon satisfaction. However there was evidence in favour of using tape for surgeons' assessment of cosmetic appearance (mean difference (VAS 0 to 100) 9.56 (95% CI 4.74 to 14.37; 2 trials, 139 participants). One trial compared tissue adhesives with a variety of methods of wound closure and found both patients and clinicians were significantly more satisfied with the alternative closure methods than the adhesives. There appeared to be little difference in outcome for different types of tissue adhesives. One study that compared high viscosity with low viscosity adhesives found that high viscosity adhesives were less time‐consuming to use than low viscosity tissue adhesives, but the time difference was small.

Authors' conclusions

Sutures are significantly better than tissue adhesives for minimising dehiscence. In some cases tissue adhesives may be quicker to apply than sutures. Although surgeons may consider the use of tissue adhesives as an alternative to other methods of surgical site closure in the operating theatre, they need to be aware that sutures minimise dehiscence. There is a need for more well designed randomised controlled trials comparing tissue adhesives with alternative methods of closure. These trials should include people whose health may interfere with wound healing and surgical sites of high tension.

Plain language summary

Tissue adhesives for closure of surgical skin incisions

Tissue adhesives or glues are increasingly used in place of stitches (sutures) or staples to close wounds. It has been suggested that tissue adhesives may be quicker and easier to use than sutures for closing surgical wounds. Tissue adhesives carry no risk of sharps injury ‐ unlike needles that are used for sutures ‐ and are thought to provide a barrier to infection. This may mean that they also promote healing, and the need for removal of sutures is avoided.

The researchers searched the medical literature up to March 2014, and identified 33 medical studies that investigated the use of tissue adhesives for closure of wounds. They compared tissue adhesive with another method of closure such as sutures, staples, tape, or another type of tissue adhesive. The main outcomes of interest were whether wounds stayed closed ‐ and did not break down ‐ and whether they became infected. The results of the review showed clearly that fewer wounds broke down when sutures were used. Studies also reported that some types of tissue adhesives might be slightly quicker to use than other types. There was no clear difference between tissue adhesives and the alternative closure methods for cosmetic results or costs. Results regarding surgeons' and patients' preferred skin closure method were mixed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Tissue adhesive compared to sutures for surgical incisions.

| Tissue adhesive compared to sutures for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: Tissue adhesive Comparison: Sutures | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks*4 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sutures | Tissue adhesive | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | Study population | RR 3.35 (1.53 to 7.32) | 736 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 13 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (21 to 99) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 1.72 (0.92 to 3.16) | 744 10 studies | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | ||

| 38 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (14 to 397) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Possible unit of analyses issues. A sensitivity analysis changes a statistically significant difference to a non‐statistically significant difference 2 Study 95% CIs are wide 3 Possible unit of analysis issues 4 Median control (suture) group risk across studies

Summary of findings 2. Tissue adhesive compared to adhesive tape for surgical incisions.

| Tissue adhesive compared to adhesive tape for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: tissue adhesive Comparison: adhesive tape | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks*3 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Adhesive tape | Tissue adhesive | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.06 to 14.55) | 50 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| 42 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (2 to 606) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 1.37 (0.39 to 4.81) | 190 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 43 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (17 to 209) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Study 95% CIs are very wide 2 Evidence of inconsistency in point estimates. With the point estimate from one study lying outside the 95% CIs of another 3 Control (tape) group risk in included study

Summary of findings 3. Tissue adhesive compared to staples for surgical incisions.

| Tissue adhesive compared to staples for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: tissue adhesive Comparison: staples | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks*3 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Staples | Tissue adhesive | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | Study population | RR 0.53 (0.05 to 5.33) | 37 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| 105 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (5 to 561) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 1.39 (0.3 to 6.54) | 250 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 71 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (21 to 463) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Study 95% CIs are very wide. 2 Evidence of point estimates lying in opposite directions with the estimate for one study lying outside the 95% CI of another. 3 Control (staples ) group risk for included study.

Summary of findings 4. Tissue adhesive compared to other methods for surgical incisions.

| Tissue adhesive compared to other methods for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: tissue adhesive Comparison: other methods | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Other methods | Tissue adhesive | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | Study population | RR 0.55 (0.13 to 2.38) | 209 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 49 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (6 to 117) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 0.41 (0.11 to 1.6) | 209 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 66 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (7 to 105) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Study 95% CIs are very wide 2 Single study with low event rate

Summary of findings 5. High viscosity tissue adhesive compared to low viscosity tissue adhesive for surgical incisions.

| High viscosity tissue adhesive compared to low viscosity tissue adhesive for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: high viscosity tissue adhesive Comparison: low viscosity tissue adhesive | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Low viscosity tissue adhesive | High viscosity tissue adhesive | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | Study population | RR 3.74 (0.21 to 67.93) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| Could not be calculated | Could not be calculated | |||||

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.16 to 4.31) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | ||

| 47 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (7 to 200) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Study 95% CIs are very wide 2 Single study with low event rate

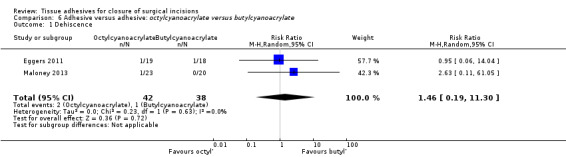

Summary of findings 6. Octylcyanoacrylate compared to butylcyanoacrylate for surgical incisions.

| Octylcyanoacrylate compared to butylcyanoacrylate for surgical incisions | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with surgical incisions Settings: Intervention: octylcyanoacrylate Comparison: butylcyanoacrylate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks*2 (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Butylcyanoacrylate | Octylcyanoacrylate | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | 26 per 1000 |

38 per 1000 (5 to 297) |

RR 1.46 (0.19 to 11) |

80 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Wound infection | Study population | RR 0.63 (0.21 to 1.88) | 37 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| 333 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (70 to 627) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 The 95% CI estimate around the RR of 1.46 is very wide 2 Median control group risk across studies

Background

Description of the condition

Millions of surgical procedures are conducted around the world each year. The majority of procedures result in surgical wounds that will heal by primary intention ‐ this is where wound edges are brought together (re‐approximated) and held together, e.g. with sutures, to facilitate tissue healing.

Description of the intervention

In the past the options for wound closure have been limited largely to sutures (needle and thread) with other alternatives such as staples, adhesive tapes and tissue adhesives entering clinical practice more recently. Closure of wounds with sutures enables meticulous closure, but skin may react to sutures and they usually require removal. Tissue adhesives (glues) offer the advantages that suture removal is not required at a later date and there is no risk of needlestick injury to the surgeon or assistant.

Tissue adhesives have been used in various forms for many years since the first cyanoacrylate adhesives were synthesised (Coover 1959). The early adhesives were appropriate for small superficial lacerations and incisions, but their limited physical properties prevented use in the management of other wounds. There were also reports of acute and chronic inflammatory reactions (Houston 1969). Further development led to the introduction of the n‐2‐butylcyanoacrlyates that were purer and stronger, but did not receive widespread acceptance because their clinical performance was limited by their low tensile strength and brittleness (Bruns 1996; Quinn 1993). More recently stronger tissue adhesives have been developed by combining plasticisers and stabilisers to increase flexibility and reduce toxicity (Quinn 1997).

Tissue adhesives have been used primarily in emergency rooms and there is increasing support in the literature for their effectiveness in the closure of various traumatic lacerations (Farion 2001; Osmond 1999; Perron 2000; Quinn 1997). Surgeons now also use tissue adhesives in the operating room for the closure of surgical skin incisions.

How the intervention might work

The introduction of tissue adhesives was received enthusiastically as they may produce equivalent tensile strength, improved cosmetic appearance of the scar and a lower infection rate when compared with sutures, staples and adhesive tapes, while avoiding many of the risks and disadvantages of alternative methods (Osmond 1999). As with standard adhesives, tissue adhesives are applied to the wound in a liquid form ‐ following application they undergo polymerisation and bonding and setting occurs.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important that clinical decision‐makers are able to make evidence‐informed decisions regarding the use of tissue adhesives to close surgical incisions. This review was first published in 2004. As tissue adhesives become more widely used, more randomised controlled trials are conducted, and this update is required to incorporate this new evidence.

Objectives

To determine the effects of various tissue adhesives compared with conventional skin closure techniques for the closure of surgical wounds.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

People of any age and in any setting requiring closure of a surgical skin incision of any length.

Types of interventions

Surgical skin incision closure with tissue adhesive compared with another tissue adhesive or any alternative conventional closure device such as sutures, staples or adhesive tapes (e.g. Steri‐Strips/butterfly stitches).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of wounds that break down (wound dehiscence).

Secondary outcomes

Proportion of infected wounds (using the study investigator's diagnosis of infection).

Cosmetic appearance at or after three months where the investigator has used a validated measure.

Patient (or in the case of studies performed with participants under the age of 16 years, parents') general satisfaction with skin incision closure technique (this is more than cosmetic appearance as other factors such as suture removal experience may have an input).

Surgeon satisfaction with skin incision closure technique (this may take into account the time for surgeon to close skin incision amongst other factors).

Relative cost of materials required for the skin incision closure techniques being compared (this will be reported in a narrative form).

Time taken to wound closure (at end of surgery) has been added to the review as a post hoc outcome measure. The review authors believe this to be a contributory factor towards both cost‐effectiveness and satisfaction.

Search methods for identification of studies

For an outline of the search methods used in the original version of this review see Appendix 1 For an outline of the search methods used in the first update of this review see Appendix 2.

Electronic searches

For this second update in March 2014 we searched the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 13 March 2014);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2014 Issue 1);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to March Week 1 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, 12 March 2014);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 12 March 2014);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 13 March 2014).

The following strategy was used to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL):

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Wounds and Injuries] explode all trees 15958 #2 surgical next wound* 3679 #3 #1 or #2 19357 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Tissue Adhesives] explode all trees 387 #5 MeSH descriptor: [Fibrin Tissue Adhesive] explode all trees 329 #6 tissue next adhesive* 655 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Cyanoacrylates] explode all trees 154 #8 octylcyanoacrylate* 52 #9 Dermabond 44 #10 MeSH descriptor: [Enbucrilate] explode all trees 42 #11 enbucrilate 62 #12 butylcyanoacrylate* 7 #13 MeSH descriptor: [Acrylates] explode all trees 1757 #14 acrylate* 254 #15 MeSH descriptor: [Bucrylate] explode all trees 0 #16 bucrylate* 6 #17 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 2397 #18 #3 and #17 225

The search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE and Ovid CINAHL can be found in Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5 respectively. The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE filter developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2011).

Searching other resources

The reviewers checked the bibliographies of new studies included in this updated review for potentially eligible references that had not been identified in the electronic searches outlined above.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently examined the titles and abstracts of all the articles identified by the search to identify potentially relevant trials and then assessed the full text of these articles independently using a standardised form to check for eligibility in the review. Disagreements about inclusion were resolved by consensus or a further review author where necessary. Two review authors performed validity assessment and data extraction on all studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Studies rejected at this stage were recorded in a table of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion recorded.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by at least two review authors independently using specially designed data extraction forms. The data extraction forms were piloted on several papers and modified as required before use. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and third review author consulted where necessary. All study authors were contacted for clarification, or to request missing information where necessary. Data were excluded if further clarification could not be obtained.

For each trial the following data were recorded:

year of publication, country of origin and source of study funding;

details of the participants including demographic characteristics and criteria for inclusion;

details of the type of intervention (adhesive, suture, staples or adhesive tape) and type of adhesive (butylcyanoacrylate or octylcyanoacrylate);

details of the outcomes reported, including method of assessment and time intervals. Cosmetic appearance was included if the authors stated that was measured on a validated scale.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

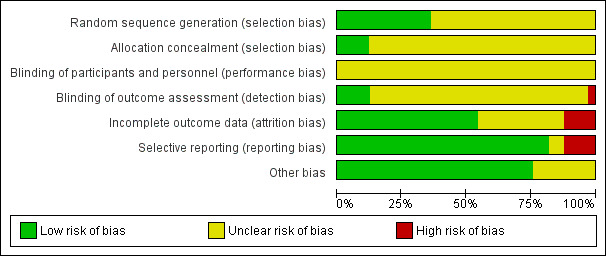

Two review authors independently assessed each eligible study for risk of bias using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias assessment tool’. The tool addresses six specific domains (see Appendix 6), namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues that may potentially bias the study (Higgins 2011). They completed a ‘Risk of bias’ table for each eligible study, and a separate assessment of blinding and completeness of outcome data for each outcome. Discrepancies between review authors were resolved through discussion. Findings are presented using the ‘Risk of bias’ summary figure, which presents all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by risk of bias domain.

Assessment of heterogeneity

This assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity will be supplemented by information regarding statistical heterogeneity ‐ assessed using the Chi² test (a significance level of P less than 0.10 will be considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity in conjunction with I² measure; Higgins 2003). I² examines the percentage of total variation across RCTs that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. In general I² values of 25%, or less, may mean a low level of heterogeneity, and values of 75%, or more, indicate very high heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Data synthesis

For dichotomous outcomes, the reviewers used risk ratios (RR) to express estimates of effect of an intervention, together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous outcomes, the reviewers used mean differences and standard deviations to summarize the data for each group. Where there were studies of similar comparisons reporting the same outcome measures, we attempted a meta‐analysis. Risk ratios were combined for dichotomous data, and weighted mean differences (WMD) for continuous data, using a random‐effects model (indicated as RE in the results section) as some heterogeneity between studies was anticipated. We planned to analyse time taken to close wound (after surgery) as survival (time‐to‐event) data, using the appropriate analytical method (as per the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook guidance Deeks 2011), or as a continuous outcome, if data from all participants were available.

The reviewers intended to meta‐analyse the results of trials with a split wound (different parts of the same wound randomised to alternate treatments), and split body designs (different wounds on the same participant randomised to alternative treatments) using the inverse variance method for paired data if appropriate data were available.

'Summary of findings' tables

In this second update we also present the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We present the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables:

wound dehiscence;

wound infection.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The reviewers intended to undertake a subgroup analysis of age (under 18 years and 18 years or older), location of incision on body (face and body), length of incision (less than 4 cm and 4 cm or greater), and patient characteristics such as diabetes and source of trial funding (commercially or independently funded), however there were insufficient studies reporting these data to undertake these analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

Where possible we planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinded outcome assessment on the overall estimates of effect. In addition, we also planned a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of including unpublished literature on the review's findings.

In this second update of the review we conducted a post‐hoc sensitivity analysis where we removed studies from key analyses where we had concerns about possible unit of analysis issues (i.e. where dehiscence and infection had been recorded over multiple time periods and it was not clear from the analyses whether some participants had more than one event).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification .

Characteristics of the trial setting and investigators

In the original review, of the 22 potentially eligible studies of which eight were excluded (Alhopuro 1976; Gorozpe‐Calvillo 1999; Jaibaji 2000; Kuo 2006; Orozco‐Razon 2002; Singer 2002; Silvestri 2006; Steiner 2000) and 14 were included (Blondeel 2004; Cheng 1997; Dowson 2006; Greene 1999; Keng 1989; Maartense 2002; Ong 2002; Ozturan 2001; Ridgway 2007; Shamiyeh 2001; Sinha 2001; Sniezek 2007; Switzer 2003; Toriumi 1998). We excluded one study because no data were presented and none were received after we sent a written request to the authors (Alhopuro 1976). Another study was excluded as we could not use the data for incision closure because they were combined with data for laceration closure (Singer 2002); we wrote to the authors to request data separated by group, but received no reply. The third study was excluded because after full translation we discovered not to be a randomised trial (Gorozpe‐Calvillo 1999). We excluded two papers because their methodology was flawed. The first of these was excluded because the intervention group had a subcuticular suture in place that was thought to bias the outcome in favour of the intervention (Jaibaji 2000). The second was excluded because all participants had a subcuticular suture placed and the review authors thought this adjunct method of closure would invalidate an independent assessment of the primary interventions (Kuo 2006). Three further studies were excluded, as two were not randomised (Silvestri 2006; Steiner 2000), and the third did not appear to be randomised, and although we sought clarification from the trial authors, no reply was received (Orozco‐Razon 2002). In the current update of this review we obtained full text for a total of 36 potentially eligible new studies. Twelve of these were excluded: three because they did not assess a relevant wound type ‐ e.g. lacerations (Ak 2012; Quinn 1998; Wong 2011); three because the studies did not report relevant outcomes (Chen 2010; Chow 2010; Sun 2005); five were not considered to be RCTs (Giri 2004; Matin 2003; Maw 1997; Spencker 2011; Sajid 2009), and one study because the closure approach was not the only systematic difference between groups (Ong 2010). We included 19 new studies in this update, which led to a total of 33 included studies. Five additional studies are awaiting assessment.

The 33 included studies were conducted in Austria (Shamiyeh 2001), Hong Kong (Cheng 1997), the Netherlands (Maartense 2002; van den Ende 2004), Turkey (Avsar 2009; Ozturan 2001), Ireland (Amin 2009), Italy (Chibbaro 2009; Pronio 2011), Austalia (Khan 2006), Mexico (Millan 2011), Portugal (Mota 2009), Germany (Romero 2011), China (Ong 2002); UK (Dowson 2006; Jallali 2004; Keng 1989; Kent 2014; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Livesey 2009; Ridgway 2007; Sinha 2001), USA (Brown 2009; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Kouba 2011; Maloney 2013; Sebesta 2004; Sniezek 2007; Switzer 2003; Tierny 2009; Toriumi 1998), and one was multicentre and international (Blondeel 2004). All studies included adults, except for six that included children (Brown 2009; Cheng 1997; Ong 2002; Romero 2011; Toriumi 1998; van den Ende 2004). All trials were of parallel group design except for two that had a split body design (different wounds on same participant randomised; Greene 1999; Kouba 2011), and two that had a split wound design (different portions of the same wound randomised; Sniezek 2007; Tierny 2009). Kent 2014 randomised participants with multiple wounds (port sites) to treatments ‐ with all wounds on the participant receiving the same intervention. Some outcome data were presented by wound rather than at the participant level, thus potentially failing to account for clustering.

Five included trials had more than two arms: Eggers 2011 had four arms and compared two tissue adhesives, staples and sutures for skin closure; Khan 2006 had three arms comparing tissue adhesive, sutures and staples; Maartense 2002 and Shamiyeh 2001 had three arms comparing tissue adhesive, sutures and adhesive tape, and Blondeel 2004 compared two types of tissue adhesive with each other and also other non‐tissue adhesive closure techniques (a mixed comparison group). These studies are thus included in multiple comparisons.

Characteristics of interventions

In total 24 of the 33 included studies compared tissue adhesive with sutures for incision closure (Avsar 2009; Brown 2009; Cheng 1997; Dowson 2006; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Jallali 2004; Keng 1989; Khan 2006; Kouba 2011; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Maartense 2002; Millan 2011; Mota 2009; Ong 2002; Ozturan 2001; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Sinha 2001; Sniezek 2007, Switzer 2003; Tierny 2009; Toriumi 1998; van den Ende 2004). Three trials compared tissue adhesive with adhesive tape (Maartense 2002; Romero 2011; Shamiyeh 2001). One of these studies also compared tissue adhesive with sutures (Maartense 2002). Six trials compared adhesives with staples (Amin 2009; Eggers 2011; Khan 2006; Livesey 2009; Pronio 2011; Ridgway 2007). Three trials compared one type of tissue adhesive with another type (Blondeel 2004; Kent 2014; Maloney 2013). Chibbaro 2009 compared a tissue adhesive with a comparison arm where staples or sutures were used and Blondeel 2004 compared tissue adhesives with any other skin closure techniques. These comparisons are summarised in Table 7.

1. Summary of study comparisons.

|

Tissue adhesive vs tissue adhesive (Comp 5) |

Mixed control (Comp 4) |

Butyl‐2‐ cyanoacrylate vs staples (Comp 3) |

2‐octyl cyanoacrylate vs staples (Comp 3) |

2‐octyl cyanoacrylate vs tape (Comp 2) |

Butyl‐2‐ cyanoacrylate vs sutures (Comp 1) |

2‐octyl cyanoacrylate vs sutures (Comp1) |

Trial ID |

2‐octyl cyanoacrylate |

Butyl‐2‐ cyanoacrylate |

Sutures | Staples | Adhesive tape/strips | Mixed sutures and staples | All non‐tissue adhesive closure methods |

Other viscosity 2‐octyl cyanoacrylate |

| 3 | Amin 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Avsar 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 4 | Blondeel 2004 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 1 | Brown 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Cheng 1997 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Chibbaro 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Dowson 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Eggers 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 1 | Greene 1999 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Jallali 2004 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Keng 1989 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Kent 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | Khan 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 1 | Kouba 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Krishnamoorthy 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Livesey 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | Maartense 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 5 | Maloney 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Millan 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Mota 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Ong 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Ozturan 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Pronio 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Ridgway 2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Sebesta 2004 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | Shamiyeh 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 1 | Sinha 2001 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Sniezek 2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Switzer 2003 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Tierny 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Toriumi 1998 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Romero 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| 1 | van den Ende 2004 | ✓ | ✓ |

Abbreviation

Comp = comparison

Comparison 1: Tissue adhesive compared with sutures

Butylcyanoacrylate versus sutures

Seven studies investigated the use of butylcyanoacrylate compared with sutures (Cheng 1997; Dowson 2006; Eggers 2011; Keng 1989; Ozturan 2001; Sinha 2001; van den Ende 2004).

Cheng 1997 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with 4.0 catgut suture in boys under 12 years of age requiring elective circumcision.

Dowson 2006 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with interruptible, non‐absorbable suture after laparoscopic procedures.

Eggers 2011 was a four‐arm trial in participants undergoing total knee arthroplasty, with one arm receiving butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive and one receiving Monocryl sutures.

Keng 1989 investigated butylcyanoacrylate in patients requiring groin incisions. Skin incisions were closed with either butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or Dexon subcuticular sutures. Three of the 43 patients had bilateral operations when the left side was closed with adhesive (butylcyanoacrylate) and the right with sutures.

Ozturan 2001) compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with 6.0 polypropylene sutures for columellar skin closure after the majority of the tension had been taken up using 5.0 chromic catgut.

Sinha 2001 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with 4.0 monofilament suture in adult patients requiring hand or wrist surgery.

van den Ende 2004 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with polyglactin 5‐0 (Vicryl) suture in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair.

Octylcyanoacrylate versus sutures

Eighteen studies investigated the use of octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives versus sutures (Avsar 2009; Brown 2009; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Jallali 2004; Khan 2006; Kouba 2011; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Maartense 2002; Millan 2011; Mota 2009; Ong 2002; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Sniezek 2007; Switzer 2003; Tierny 2009; Toriumi 1998).

Avsar 2009 compared high viscosity octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with polypropylene sutures in women undergoing the Pfannenstiel incision in the abdomen.

Brown 2009 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with Monocryl sutures in children undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy.

Eggers 2011 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with monocryl sutures in people undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Greene 1999 and Kouba 2011 randomised participants requiring bilateral blepharoplasty. This model with two identical skin sites on the same patient allowed a split‐body study design and each participant to act as his or her own control. The left or right upper eye lid was closed with octylcyanoacrylate and the other eyelid closed with 6.0 suture.

Jallali 2004 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with absorbable sutures in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Khan 2006 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with Monocryl sutures in people undergoing either a total knee arthroplasty or a total hip arthroplasty.

Krishnamoorthy 2009 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with absorbable sutures in people undergoing saphenous vein harvesting.

Maartense 2002 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with intracutaneous poliglecaprone interrupted sutures in people requiring elective laparoscopic procedures.

Millan 2011 compared cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive (no further details available) compared with monofilament sutures in people undergoing skin biopsies.

Mota 2009 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with rapidly absorbably polyglactin sutures in women undergoing mediolateral episiotomy after a vaginal delivery.

Sebesta 2004 compared octylcyanoacrylate with subcuticular suture in people who had undergone laparoscopic surgery.

Shamiyeh 2001 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with 5.0 monofilament sutures in patients requiring mini‐phlebectomy with the Muller technique. This study also compared tissue adhesive with adhesive tape.

Switzer 2003 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with a subcuticular Monocryl suture for the elective repair of inguinal hernias. Ong 2002 also compared octylcyanoacrylate with a Monocryl subcuticular suture, but in children requiring herniotomies.

Sniezek 2007 followed a split wound design comparing octylcyanoacrylate with a cuticular polypropylene suture on head and neck surgical sites following the removal of carcinomas using the Mohs technique.

Tierny 2009 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with rapid absorbing gut sutures in people undergoing surgery for non‐melanomas skin cancer.

Toriumi 1998 investigated incisions with and without subcutaneous sutures and then randomised for closure with octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or 5.0 or 6.0 nylon suture in people over one year of age and over requiring elective surgery for benign skin lesions predominantly in the face and neck.

Comparison 2: Tissue adhesives compared with adhesive tape

Octylcyanoacrylate versus adhesive tape

Three studies compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with adhesive tapes.

Shamiyeh 2001 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with tape in adults requiring mini‐phlebectomy with the Muller technique.

Maartense 2002 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive to 76 mm x 6 mm adhesive paper (Steri‐Strips) in people undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery.

Romero 2011 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with standard adhesive strips (strips applied in star‐shaped manner) in children undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy.

Comparison 3: Tissue adhesives compared with staples

Butylcyanoacrylate versus staples

Two studies compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with staples.

Livesey 2009 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with staples in people undergoing a total hip replacement.

Eggers 2011 compared butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with staples in people undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Octylcyanoacrylate versus staples

Five studies compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples.

Ridgway 2007 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples in people requiring thyroid and parathyroid surgery.

Eggers 2011 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples in participants undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Amin 2009 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples in people undergoing minimally invasive thyroidectomy.

Khan 2006 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples in people undergoing either a total knee arthroplasty or a total hip arthroplasty.

Pronio 2011 compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesives with staples in people undergoing thyroid surgery.

Comparison 4: Tissue adhesives compared with other techniques

Octylcyanoacrylate versus mixture of other closure approaches

Blondeel 2004 was the only study that investigated the use of tissue adhesives in incisions of 4 cm or longer. High viscosity octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive was compared with any other commercially available device such as sutures, staples or tapes and also compared with low viscosity octylcyanoacrylate. The high viscosity formulation is six‐times more viscous than the normal adhesive and designed to reduce run‐off of pre‐polymerised adhesive from the application site.

Butylcyanoacrylate versus mixture of other closure approaches

Chibbaro 2009 compared a group allocated to butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with a group allocated to receive either sutures or staples for skin closure ‐ based on clinician choice ‐ in people undergoing elective cranial supratentorial surgery.

Comparison 5: Tissue adhesive compared with tissue adhesive

High versus low viscosity adhesives

Blondeel 2004 compared high and low viscosity adhesive in the trial described above.

Octylcyanoacrylate versus butylcyanoacrylate

Three studies compared octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive with butylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive for skin closure.

Eggers 2011 compared these tissue adhesives in people undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Kent 2014 compared these tissue adhesives in people undergoing a range of laparoscopic procedures.

Maloney 2013 compared these tissue adhesives in people undergoing a skin incision to remove skin cancer.

Characteristics of outcome measures

Wound dehiscence

Twenty‐three studies reported wound dehiscence. The time of post‐operative wound examination for dehiscence varied between studies. Cheng 1997 reported dehiscence at days 1, 2, 3, 7 and 30; Toriumi 1998 reported dehiscence at 5 to 7 days; Chibbaro 2009, Ozturan 2001, Pronio 2011, Sniezek 2007 and Tierny 2009 at 7 days; Shamiyeh 2001 and van den Ende 2004 at 10 days; Greene 1999 at weeks 1, 2 and 4; and Sinha 2001 at 10 days, 2 weeks and 6 weeks. Ong 2002 assessed dehiscence at 2 to 3 weeks; Keng 1989 and Sebesta 2004 at 2 weeks; Dowson 2006 at day 1, 2 and at 4 to 6 weeks; Switzer 2003 at 2 and 4 weeks; Blondeel 2004 at day 10; Brown 2009 at 6 weeks; Eggers 2011 at 24 hours, 3 weeks and 6 weeks; Maloney 2013 at 2 weeks and 3 months; Mota 2009 from 42 hours to 68 hours; Romero 2011 at day 10 and day 90; and Millan 2011 on days 5, 7, 10 and 14.

We felt there were potential unit of analysis issues in four studies where it was not clear whether one person had more than one episode of dehiscence over multiple time periods (Cheng 1997; Eggers 2011; Millan 2011; Sinha 2001). We acknowledged this in the 'Risk of bias' assessment and sensitivity analysis we conducted.

Wound infection

In total 25 studies measured wound infection. One study noted infection, defined as wound discharge with positive bacterial culture, at days 1, 2, 3, 7 and 30 (Cheng 1997). A second study defined infection as the presence of pus (Keng 1989), and examined wounds at 1 and 4 weeks postoperatively. A third study defined infection as an abscess that required drainage (Ozturan 2001), and examined wounds at 1 week. A fourth study defined infection as a spontaneous drainage of purulent fluid (Maartense 2002), and noted this at 2 weeks and 3 months. Blondeel 2004 defined infection as redness more than 3 mm to 5 mm from the wound margin, swelling, purulent discharge, pain, increased skin temperature, fever or other signs of infection and assessed this at day 10. Switzer 2003 described an infection as a draining sinus. Avsar 2009 assessed infection at 2, 7 and 40 days postoperatively using a definition of infection that was thought to be purulence and accompanying erythema, but the translation we used was not completely clear about this definition. Livesey 2009 defined wound infection as a participant requiring antibiotics specifically for suspected wound infection, this was assessed at 24 hours, 3 weeks and 6 weeks postoperatively. Khan 2006 classed follow‐up as early, which seemed to be the first 3 days after surgery, and then late, which was between 8 weeks and 12 weeks postoperatively; where cultures were positive or there was clinical evidence of cellulitis, the participants were treated with a course of antibiotics and recorded as having an ‘infection'. Romero 2011 assessed wounds at the 10th and 90th days postoperatively and defined infection as an abscess or redness more than 3 mm perpendicular to the wound. One study simply referred to wound complications (Dowson 2006). A further 14 studies reported upon infection, but did not describe how infection would be defined for diagnosis and reporting in the study (Chibbaro 2009; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Kent 2014; Ong 2002; Maloney 2013; Pronio 2011; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Sinha 2001; Sniezek 2007; Tierny 2009; Toriumi 1998; van den Ende 2004).

We felt there were potential unit of analysis issues in two studies where it was not clear whether one person had more than one episode of infection over multiple time periods (Eggers 2011; Khan 2006). While we have reported the total number of infections reported by group it was not clear whether some participants reported more than one infection, as the number of infections was reported rather than number of people having at least one infection. We have acknowledged this in the 'Risk of bias' assessment and sensitivity analysis we conducted.

Cosmetic appearance

Eleven studies reported cosmetic appearance with data that could be used for further analyses. One study asked participants to score their own cosmetic result using a validated visual analogue scale (VAS; Maartense 2002). Participants in the Dunker 1998 trial were also asked to complete the cosmetic scale of the Body Image Questionnaire. Surgical residents who were blinded to the wound closure method also scored the cosmetic appearance with a VAS and the Hollander Wound Evaluation Score (Hollander 1995). These assessments were undertaken at two weeks and three months (with three month data presented). Ozturan 2001 reported cosmetic appearance at 3 months by blinded assessment of photographs using VAS, with best possible scar rated as 100 and worst possible scar as 0 (Quinn 1995), and the Hollander Scale. A third study also reported surgeon‐assessed cosmetic appearance at three months using a modified Hollander Wound Evaluation scale ‐ this was a blinded assessment (Kent 2014). Livesey 2009, Maloney 2013 and Romero 2011 reported surgeon‐assessed cosmetic appearance at three months using a 100 mm VAS, where 0 represented the worst outcome and 100 the best outcome ‐ in all cases the surgeon‐assessed outcome was blinded. Livesey 2009 and Maloney 2013 also used the same VAS scale to assess participant data on cosmetic appearance, but it was unclear whether these assessments were blinded.

Pronio 2011 asked participants to assess cosmetic appearance using the Stony Brook scar evaluation scale composed of five dichotomous, evenly weighted categories. Mean data presented here were calculated by the review authors from data included in the study report. Kouba 2011 reported surgeon‐assessed cosmetic appearance at one month and three months (we report three month data). The cosmetic presence of the wound was scored on a scale of 1 (excellent wound healing, scar matches surrounding skin) to 5 (poor scar wound healing, does not match surrounding skin); this was a blinded assessment.

A number of studies reported data that could not be used further. Toriumi 1998 assessed cosmetic appearance at three months and one year using a modified Hollander scale at three months and a VAS of photographs at one year using two surgeons blinded to treatment group. However, we could not use the data from this study at three months as the standard deviation was not reported and one participant dropped out from an unspecified group. Data at one year could not be used, as the group(s) from which 11 participants had dropped out was not clear. Ong 2002 evaluated cosmesis using a VAS and the Hollander Scale at three weeks and three months, but the first data could not be used as it was too early, and the data at three months could not be used due to large and unspecified loss to follow‐up. Dowson 2006 assessed cosmetic outcome using the Hollander scale at six weeks and three months. The six‐week data were not included as it was too early and the three‐month data did not report mean and standard deviation statistics; we contacted the authors but they did not respond, therefore the data could not be included. Sniezek 2007 also assessed cosmesis at three months using a VAS, but there were insufficient data for inclusion. Amin 2009, Chibbaro 2009 and Tierny 2009 also reported cosmetic appearance at three months, but the data were not clear and were also not used.

Several studies evaluated cosmetic appearance less than three months after surgery (Avsar 2009; Blondeel 2004; Brown 2009; Cheng 1997;Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Keng 1989; Khan 2006; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Ong 2002; Ridgway 2007; Sebesta 2004; Sinha 2001; Switzer 2003).

Patient/parent satisfaction

Thirteen studies reported satisfaction outcomes. Patient satisfaction interviews in one study included questions about comfort, presence of a pulling sensation and appreciation of lack of suture removal at weeks one, two and four (Greene 1999). Wound comfort at one and four weeks was assessed in another study (Keng 1989). A third study assessed participants at one year using a scale of satisfaction with scar (Shamiyeh 2001). One study assessed patient satisfaction by using a questionnaire that included ratings for cosmetic appearance, overall comfort, ability to shower, dressing changes, tension at the wound, hygienic problems or allergic reaction and overall satisfaction (Blondeel 2004). Amin 2009 assessed patient satisfaction at three months using a self‐completed 10 cm VAS line where 0 was poor and 10 was excellent. Avsar 2009 assessed patient satisfaction at day 40 when participants were asked how satisfied they were with their skin closure and could choose from the following responses: very bad, poor, average, good, very good. Ong 2002 and Khan 2006 assessed participant/parent satisfaction using a VAS scale that ran from 0 to 100, where 100 represented maximal satisfaction. Data for Khan 2006 were presented as median values, and separately for different types of arthroplasty, and are not reported further in this review. Dowson 2006 and Romero 2011 reported patient satisfaction as a simple 'satisfied' or 'not satisfied', but gave little information about the criteria used. Likewise, Kent 2014 report participants' satisfaction with incisional wound closure ‐ options were 'satisfied' or 'dissatisfied'. Pronio 2011 assessed participants' satisfaction with wound management at a seven‐day follow‐up when participants were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with the early postoperative management of the wound (regarding the requirement of a return visit for medications, the possibility of washing oneself, and suture removal) using a numerical scale ranging from 0 to 10. Data were reported in merged categories (e.g. percentage of participants reporting a score of 10 to 9, 8 to 7 etc.), which limited further use of these data. One paper reported upon participant satisfaction as an outcome measure in the text (Sniezek 2007), but no results were reported in the analyses. We attempted to contact the authors, but received no reply.

Surgeon satisfaction

In one study (Greene 1999), surgeon satisfaction included quality of wound closure by assessment of eversion, regularity, approximation and any difficulties in attaining approximation. This was reported at weeks one, two and four. Another study reported surgeon satisfaction at 10 days using a scale of satisfaction with the scar on a five‐point score (where 1 was a 'perfect cosmetic result' to 5 'unsatisfactory result'; Shamiyeh 2001). A third study reported surgeon satisfaction immediately after closure, when the surgeon was asked to give his or her opinion on the time needed for wound closure and the practicality of the materials used by answering multiple choice questions (potential responses included: 'far too long', 'a little too long', 'not too long', 'not practical', 'not very practical' and 'very practical'; Maartense 2002). Due to differences in methods used to measure this outcome, these studies were not included in the meta‐analysis. One study did report surgeon satisfaction via a questionnaire that included ratings for wound cosmetic appearance, safety, effectiveness, applicability for a wide range of incisions, perceived patient satisfaction and overall satisfaction (Blondeel 2004). Kent 2014 assessed surgeons' satisfaction with wound (considering expression, application, delivery and ease of use for product); the options were 'satisfied' or 'dissatisfied'. Maloney 2013 assessed surgeon satisfaction (at time of wound closure) using 100 mm VAS scales for: ease of use (0 'impossible' to 10 'very easy to use') and satisfaction with device and the closure achieved (0 'completely dissatisfied' to 10 'completely satisfied').

Relative cost of materials

Costs of closure devices were reported in five studies (Brown 2009; Eggers 2011; Maartense 2002, Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001).

Time for wound closure following surgery

Time for closure was reported in 24 studies (Avsar 2009; Brown 2009; Blondeel 2004; Cheng 1997; Chibbaro 2009; Dowson 2006; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Jallali 2004; Keng 1989; Kent 2014; Khan 2006; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Livesey 2009; Maartense 2002; Maloney 2013; Ong 2002; Ozturan 2001; Ridgway 2007; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Switzer 2003; Toriumi 1998; van den Ende 2004). The data from 15 of these studies were excluded as they were insufficient (Avsar 2009; Cheng 1997; Chibbaro 2009; Dowson 2006; Eggers 2011; Greene 1999; Jallali 2004; Keng 1989; Khan 2006; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Livesey 2009; Maartense 2002; Switzer 2003; Toriumi 1998; van den Ende 2004). Data from the remaining nine studies were eligible for inclusion (Blondeel 2004; Brown 2009; Kent 2014; Maloney 2013; Ong 2002; Ozturan 2001; Ridgway 2007; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001). The time was recorded as a continuous variable in seconds or minutes elapsed from beginning of wound closure to completion of wound closure. Mean time to closure times were only used in the review if this was measured on all participants, thereby avoiding concerns about time to event data being analysed incorrectly.

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the quality assessment for included trials is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation was performed adequately in twelve studies (Amin 2009; Blondeel 2004; Eggers 2011; Khan 2006; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Maartense 2002; Mota 2009; Ong 2002; Romero 2011; Shamiyeh 2001; Sniezek 2007; Switzer 2003). All studies used a random sequences generated by computerised randomisation programmes except for Sniezek 2007, which used coin tossing.

In the remaining 20 studies, the risk of bias in the random sequence generation was unclear. This was largely because, although there was mention of the participants being randomised into different intervention arms, there was no mention of the methods used to achieve this (Brown 2009; Cheng 1997; Chibbaro 2009; Dowson 2006; Greene 1999; Jallali 2004; Keng 1989; Kent 2014; Kouba 2011; Livesey 2009; Maloney 2013; Millan 2011; Ozturan 2001; Pronio 2011; Ridgway 2007; Sebesta 2004; Sinha 2001; Tierny 2009; Toriumi 1998). The partial translation of Avsar 2009 was such that no conclusion could be derived about whether there was adequate evidence of random sequence generation, therefore the judgement remained unclear.

Allocation concealment

Four studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for the domain of allocation concealment: Amin 2009, Dowson 2006, and Ong 2002 reported that they used sealed, sequential envelopes, that were opened shortly before the intervention was given. Livesey 2009 did not indicate that numbered envelopes were used, but stated that envelopes were opened by independent personnel. All remaining studies were deemed to be at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. Some studies gave evidence that they used envelopes that were sealed and opaque, but lacked sufficient evidence that they were sequentially numbered or that the process was undertaken by an independent person. Many other studies provided no information on allocation of the randomisation sequence at all.

Blinding of participants and personnel

The risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel was judged to be unclear in all studies. It was difficult to see how the operating surgeon could be completely blinded to an intervention he/she was supposed to undertake. Only Dowson 2006 and Mota 2009 suggest that participants remained blinded to the intervention they received. Given the difficulties faced in blinding participants (in most cases) and personnel to the intervention, we felt it reasonable to judge all of the included studies as being at unclear risk of bias, as it is uncertain how this influenced the performance of the personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment

Risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment was undertaken for each relevant outcome, and thus was often characterised as being at both unclear and high risk of bias within the same study. This was often because numbers of wounds breaking down and wound infection were assessed in a way that was not obviously blinded, but cosmesis was deemed to be blinded. Such examples of studies where blinding of dehiscence was unclear and blinding of cosmesis was adequate were: Blondeel 2004, Dowson 2006, Kent 2014, Livesey 2009, Maloney 2013, Ong 2002, Ozturan 2001, Romero 2011, Shamiyeh 2001, and Toriumi 1998.

There were studies that did give enough evidence for us to infer a low risk of detection bias. These were Amin 2009, Brown 2009, and Maartense 2002, all of which revealed adequate blinding of outcome assessment for all measures extracted for this review. In one study, there was evidence to suggest a high risk of bias (Mota 2009), as the study report indicated that those assessing the wounds were the authors of the paper.

The remaining studies did not provide evidence of adequate blinding of outcome assessments at any stage and were classed as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies were classed as having a high risk of attrition bias (Dowson 2006; Kent 2014; Ong 2002; Sinha 2001). This was often due to high proportional rates of drop out, or unclear reasons for large numbers of drop outs, or both.

Eleven studies were judged as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain, as reasons for drop out were not clear, or the extent to which the drop‐out rates affected the results were unclear (Amin 2009; Avsar 2009; Eggers 2011; Kouba 2011; Krishnamoorthy 2009; Livesey 2009; Millan 2011; Mota 2009; Ridgway 2007; Romero 2011; Toriumi 1998).

The remaining 18 studies suffered fewer losses to follow‐up and, where these did occur they were fully explained in the literature, so these studies were judged to be at low risk of bias for this domain.

Selective outcome data

Amin 2009, Kouba 2011, Livesey 2009 and Ozturan 2001 were reported to be at high risk of bias due to possible selective reporting of outcomes.Twenty‐seven studies were deemed to have a low risk of reporting bias as they reported on all the outcomes that were outlined in the methodology,

Two studies were judged as unclear, either due to an unclear English translation (Avsar 2009), or because outcomes that were outlined as being assessed were not clearly reported (Sebesta 2004).

Other sources of bias

Eight studies were classed as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain, including six studies where it was it was not possible to exclude unit of analysis issues, for example, we could not establish whether dehiscence or other data, or both, were reported per person, or if the same wounds had more than one infection during the period of the trial (Cheng 1997; Eggers 2011; Jallali 2004; Kent 2014; van den Ende 2004). Avsar 2009 and Millan 2011 were classed as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain, as we could not make a judgement using the translations that we had. The remaining 25 studies were deemed not to offer any other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Comparison 1. Tissue adhesives compared with sutures

Primary outcome

Data from 17 trials compared the use of tissue adhesive with sutures for dehiscence, however as seven trials had no cases of dehiscence, only data from the remaining ten trials contributed to the meta‐analysis (Cheng 1997; Dowson 2006; Eggers 2011; Millan 2011; Mota 2009; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Sinha 2001; Switzer 2003; van den Ende 2004). Overall a significant difference was detected between the proportion of wounds with dehiscence (RR 3.35, 95% CI 1.53 to 7.33; Analysis 1.1), that favoured closure by suture with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2= 0). Taking an assumed control risk of 0.01 (10 per 1000) this returns a number needed to harm of 43. Only one study was deemed to be at low risk of bias for blinded outcome assessment for this outcome (Sinha 2001; Figure 1; Figure 2). Dowson 2006, Mota 2009 and Sinha 2001 had one domain at high risk of bias. The remaining studies had domains classed at low or unclear risk of bias.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 1 Dehiscence: all studies.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we removed studies that were at unclear risk of bias for this outcome due to possible unit of analysis issues: these studies were Cheng 1997, Millan 2011, and Sinha 2001 (these authors were contacted where possible to request clarification regarding their data) and also van den Ende 2004, as we were not clear whether this trial reported data at the participant level. When this analysis was undertaken a similar effect size was found, however, there was reduced precision and the findings were no longer statistically significant (RR 2.70, 95% CI 0.95 to 7.68; P value 0.06; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 2 Dehiscence: sensitivity analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Infection

Eighteen trials that compared the use of tissue adhesives with sutures reported wound infection data, however, as eight of these had no cases of infection, only data from the remaining ten studies contributed to the meta‐analysis (Avsar 2009; Cheng 1997; Eggers 2011; Khan 2006; Maartense 2002; Ozturan 2001; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001; Switzer 2003; van den Ende 2004). There was no evidence of a difference in the proportion of participants developing infection in the individual trials, or when data from the trials were pooled (RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.94 to 3.16; Analysis 1.3); again there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2= 0).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 3 Infection: all studies.

Three studies were considered to have the potential for unit of analysis issues for this outcome (Eggers 2011; Khan 2006; van den Ende 2004). We conducted a sensitivity analysis removing these studies from the meta‐analysis. Again there was no evidence of a difference in the proportion of participants developing infection between groups (RR 2.03, 95% CI 0.80 to 5.12; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 4 Infection: sensitivity analysis.

Cosmetic appearance

There was no evidence of a difference in the participants' assessment of cosmetic appearance (MD ‐2.12, 95% CI ‐7.20 to 2.95; Analysis 1.5). Likewise there was no evidence of a difference for the surgeons' assessment of cosmetic appearance based on a 0 to 100 VAS (MD 3.00, 95% CI ‐3.30 to 9.30), or a scar assessment scale (MD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 0.06; Analysis 1.6; Kouba 2011).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 5 Cosmetic appearance rated by patient.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 6 Cosmetic appearance rated by surgeon.

Patient/surgeon satisfaction

There was no evidence of a difference in patient, surgeon or patient/parent satisfaction with treatment (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Dowson 2006; Maartense 2002; Ong 2002; Shamiyeh 2001). In one further study 13/20 participants stated that they preferred the tissue adhesive while the remaining seven preferred the sutures (Greene 1999). Avsar 2009 reported that 6/20 participants in the adhesive group reported average satisfaction; 5/20 good and 9/20 very good. This was compared to 13/20 recording good and 7/20 very good in the suture arm.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 7 Patient/parent satisfaction (% satisfied).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 8 Patient/parent satisfaction (VAS Scale 0 to 100).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 9 Surgeon satisfaction (% satisfied).

Costs

Four studies reported costs. Shamiyeh 2001 reported that one tube of tissue adhesive at USD 11.00 could be used to close 3.5 incisions of 5 mm mean length, while one suture at USD 1.10 could be used to close five incisions, and one package of tape (six pieces) at USD 0.24 could be used to close three incisions ‐ this calculation assumes multiple incisions on the same patient. A second study reported that for closure of laparoscopic trocar wounds the costs were EUR 13.90 for one ampoule of octylcyanoacrylate, EUR 2.47 for one package of poliglecaprone suture (used together with a dressing at EUR 0.42 each) and EUR 1.15 per package of adhesive paper tape (Maartense 2002). Eggers 2011 reported that the total cost associated with surgery for each of the closure groups (including all aspects of surgery associated with materials, labour, and operating room expenses) was USD 993.20 for octylcyanoacrylate; USD 878.27 for butylcyanoacrylate and USD 1056.32 for staples. No measures of variation were presented. Sebesta 2004 reported that the mean tissue adhesive cost per patient was USD 65.10 (range USD 40.60 to USD 101.5; standard deviation (SD) USD 13.70) whilst the total cost for surgery in the octylcyanoacrylate group (i.e. cost for operating room time, cost and cost of suture material) was USD 193.32 (range USD 130 to USD 365; SD USD 49.40). For the suture group the mean suture cost per patient was USD 7.74 (range USD 3.60 to USD 10.80; SD USD 2.05) and the total mean cost was USD 497 (range USD 295 to USD 835; SD USD 139.70).

Time for wound closure following surgery

Five studies reported the time taken for closure (Brown 2009; Ong 2002; Ozturan 2001; Sebesta 2004; Shamiyeh 2001). Pooling these trials was not appropriate due to massive heterogeneity (I2 = 100%; Analysis 1.10). Two of the trials suggested that adhesive took longer to apply than sutures, and in one of these trials the difference was statistically significant (Shamiyeh 2001), although the units for this were unclear ‐ if measured in seconds then the difference, although significant, could be small in terms of total time saved with one method compared to the other. In remaining three trials, suturing took significantly more time than adhesive (Brown 2009; Ozturan 2001; Sebesta 2004). Sebesta 2004 reported that application of adhesive took on average 3.7 minutes compared with 14 minutes on average in the suture group. Ong 2002 and Ozturan 2001 were both deemed to be at high risk of bias for one domain (Figure 1; Figure 2).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Adhesive versus suture, Outcome 10 Time taken for wound closure.

Summary: tissue adhesives compared with sutures

There was an overall difference favouring sutures over tissue adhesives in that sutures led to a reduced risk of dehiscence, though several studies that contributed data to this analysis had at least one risk of bias domain that was classed as being at high risk. Removal of studies with a possible unit of analysis issue reduced the precision and the results then lay just outside the standard definition of statistical significance.There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of developing a wound infection in trial groups ‐ although the comparison is underpowered and confidence intervals are wide. One study was at both low and unclear risk of bias across domains: its results were statistically significant and suggested that using sutures for closure was slightly faster than using tissue adhesives. However, a second study had opposite findings, which were also statistically significant, suggesting that closure with tissue adhesive was significantly faster than sutures by over 10 minutes on average.

Comparison 2. Tissue adhesives compared with adhesive tape

Three trials provided data comparing tissue adhesives with adhesive tape (Maartense 2002; Romero 2011; Shamiyeh 2001). These trials were rated as being at low or unclear risk of bias for domains (Figure 1; Figure 2).

Primary outcome

There was no significant difference between closure techniques in the single trial that contributed data to this comparison for dehiscence (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.06 to 14.55; Analysis 2.1; Shamiyeh 2001): this comparison was underpowered, as only one participant experienced dehiscence in each group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 1 Dehiscence.

Secondary outcomes

Infection

All three trials reported wound infection, but there was no evidence of a difference between the groups in the proportion of participants with infection (RR 1.37 95% CI 0.39 to 4.81; Analysis 2.2). Again this comparison was underpowered, with only 10 infection events in total.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 2 Infection.

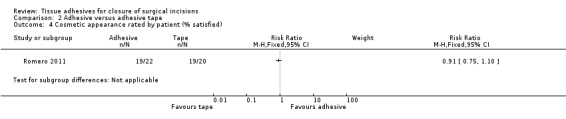

Cosmetic appearance

Maartense 2002 and Romero 2011 found no statistically significant difference for participants' assessment of cosmetic appearance (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4), however both studies reported evidence of a difference for the surgeons' blinded assessment using a VAS favouring closure by adhesive tape (pooled estimate MD 9.56, 95% CI: 4.74 to 14.37; I2 = 14%; Analysis 2.5).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 3 Cosmetic appearance rated by patient (VAS).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 4 Cosmetic appearance rated by patient (% satisfied).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 5 Cosmetic appearance rated by surgeon (VAS).

Patient/surgeon satisfaction

Shamiyeh 2001 found no difference between the groups for patient satisfaction (Analysis 2.6). Similarly, Maartense 2002 and Shamiyeh 2001 found no evidence of a difference between the groups with respect to surgeons' satisfaction (Analysis 2.7).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 6 Patient satisfaction.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 7 Surgeon satisfaction.

Time to wound closure following surgery

Shamiyeh 2001 presented data for time to closure and demonstrated that tapes were significantly faster to use than adhesives (MD 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.70; Analysis 2.8). (Review authors' note: units not reported in trial, we assumed that units are minutes).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adhesive versus adhesive tape, Outcome 8 Time taken for wound closure.

Summary: tissue adhesive compared with adhesive tape

There were limited data for wound dehiscence and wound infection for the comparison of tissue adhesive against adhesive tape. Only one trial reported dehiscence as an outcome, and this was underpowered. Three trials reported wound infection as an outcome, and these were also underpowered. Based on these small studies there is currently no evidence of a difference in the incidence of dehiscence or wound infection when wounds are closed with tissue adhesive or tape. Surgeons' assessment (blinded) of the cosmetic outcome was better in the tape group. One study reported a significant difference in time taken for closure and this favoured adhesive tape (time units not clear).

Comparison 3. Tissue adhesives compared with staples

Six studies compared a tissue adhesive with staples for wound closure (Amin 2009; Eggers 2011; Khan 2006; Livesey 2009; Pronio 2011; Ridgway 2007).

Primary outcome

Two trials that compared the use of tissue adhesives with staples presented data for dehiscence (Eggers 2011; Pronio 2011). As there were no cases of dehiscence in one trial, only one trial contributed data to the comparison (Eggers 2011). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of wounds that dehisced in the tissue adhesive group compared to the staples group (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.33; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Adhesive versus staples, Outcome 1 Dehiscence.

Secondary outcomes

Infection