Abstract

Inositol phosphates (InsPs) are ubiquitous in all eukaryotes. However, since there are 63 possible different phosphate ester isomers, the analysis of InsPs is challenging. In particular, InsP1, InsP2, and InsP3 already amass 41 different isomers, of which some occur as enantiomers. Profiling of these “lower” inositol phosphates in mammalian tissues requires powerful analytical methods and reference compounds. Here, we report an analysis of InsP2 and InsP3 with capillary electrophoresis coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (CE-ESI-MS). Using this method, the bacterial effector RipBL1 was analyzed and found to degrade InsP6 to Ins(1,2,3)P3, an understudied InsP3 isomer. This new reference molecule then aided us in the assignment of the isomeric identity of an InsP3 while profiling human samples: in urine and kidney stones, we describe for the first time the presence of defined and abundant InsP3 isomers, namely Ins(1,2,3)P3, Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or Ins(2,3,4)P3.

Kidney stones and patient urine contain inositol 1,2,3-trisphosphate as demonstrated by capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry with an internal heavy isotope reference.

Introduction

myo-Inositol phosphates (InsPs) are molecules with various numbers of phosphate groups modified on one to six of the OH groups of myo-inositol (hereafter Ins), which are present in all eukaryotes. By sequential phosphorylation, 63 different InsPs can in principle be generated, of which over one third are thought to be relevant to mammalian metabolism as signalling molecules.1,2

Analysis of these InsPs is important to better characterize InsP identity and abundance in mammalian metabolism, which might finally lead to a deciphering of the alleged “inositol phosphate code”.1,3,4 A variety of analytical methods have been reported, including, for example, strong anion exchange high performance liquid chromatography (SAX-HPLC), high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS), and capillary electrophoresis coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (CE-ESI-MS).5–13 Most of these methods are sensitive and efficient for the analysis of highly phosphorylated InsPs (e.g. InsP4, InsP5, InsP6).5–11 Moreover, CE-MS methods are powerful tools for profiling of inositol pyrophosphates (PP-InsPs), such as InsP7 and InsP8 that carry one or several diphosphate groups.6,14–16

Analyzing identity and abundance of InsP1, InsP2 and InsP3 isomers in biological samples remains a significant challenge for several reasons. First, due to the non-specificity of the current extraction and separation methods, it is difficult to identify InsP1 and InsP2 isomers from the isobaric and more abundant sugar mono- and diphosphates. Second, the number of possible InsP1 to InsP3 isomers amasses to 41 and out of these alone 20 isomers of InsP3 exist, including 8 enantiomeric pairs. Enantiomer separation on a chiral stationary phase remains an unsolved issue for these molecules. Additionally, it is generally assumed that the myo-configuration is the relevant one, but also other inositol configurations occur in biology.17 Moreover, the high negative charge density and the absence of a chromophore generate significant issues regarding sensitive detection. The most commonly used analytical methods for InsP2 and InsP3 separation are SAX-HPLC and HPLC-MS.9,18,19 The latter can profit from a heavy isotope labelling methylation strategy to enable ESI+ measurements.9 Ins(1,4,5)P3, the Ca2+ release factor,20 is the most characterized InsP3 and represents the textbook example of a second messenger. Other InsP3 isomers have been described in biology, such as Ins(1,3,4)P3 and Ins(1,2,3)P3.18 InsP(1–5) with a phosphate group in the 2-position are usually not described in mammalian metabolite overviews,2,21–24 although such esters of InsP2 and InsP3 have been found since 1995.18,25,26 Recently, using 13C enrichment and 2D-NMR analysis, it was discovered that Ins(2,3)P2 and Ins(2)P are major metabolites in immortalized mammalian cell lines, calling into question the general notion that InsPs with a phosphate in the axial 2-position are biologically irrelevant.27 A recent finding that 2-PP-InsP5 carrying a pyrophosphate in the 2-position is a biologically relevant species, further underscores the need to reassess inositol phosphate structures.16 Recently developed new analytical technologies are now able to reveal several ‘discarded’ isomers, whose biological importance must now be evaluated.

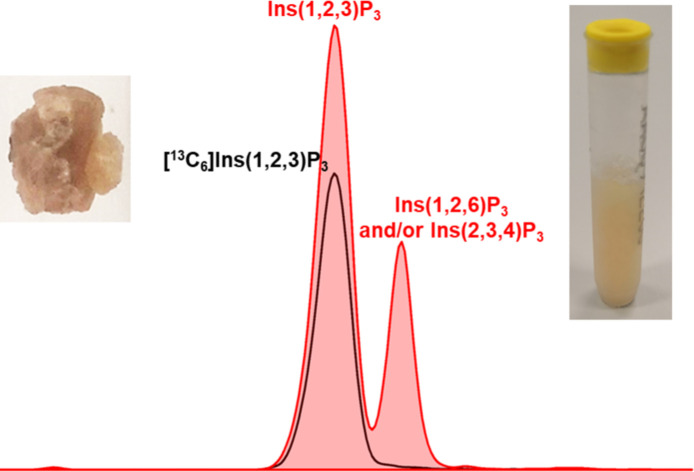

Our approach to analyze InsP4–6 and PP-InsPs by CE-ESI-MS is extended herein to study InsP2–3. We were interested to profile human samples and since the involvement of PP-InsPs in systemic human phosphate homeostasis has become clearer,28–31 we decided to analyze urine samples where excess phosphate is excreted. Surprisingly, we detected several InsP3 isomers in urine. This led us to postulate that these InsP3 might be structural components of kidney stones. If this would be the case, we could potentially use urine InsP presence as a biomarker for impending stone formation. To achieve our objectives, we reveal that RipBL1, a bacterial phytase effector protein,32 selectively dephosphorylates InsP6 to Ins(1,2,3)P3. Our CE-ESI-MS method combined with [13C6] InsP3 produced from [13C6] InsP633,34 by RipBL1 now enables us to assign InsP3 in human kidney stone and urine and demonstrates in patient samples (healthy vs. kidney stone formers) that the most abundant isomers host a phosphate in the 2-position.

Results

InsP2 and InsP3 isomers are well separated by CE-ESI-MS

The CE-ESI-MS analytical method has been originally developed to investigate inositol pyrophosphate metabolism and is a particularly effective separation platform for isomers of InsP4–6 and also for PP-InsPs.6 CE-ESI-MS was not further developed to analyze InsP1–3 in biological samples, despite the potential for the determination of spiked InsP3 in plasma by capillary zone electrophoresis-mass spectrometry.12 There are 15 isomers of InsP2 that include 6 enantiomeric pairs, and 20 InsP3 isomers that include 8 enantiomeric pairs. We disclose a CE-ESI-MS method for analyzing six commercially available isomers of InsP2 and seven commercially available isomers of InsP3 by baseline separation, other than enantiomers, which one cannot discriminate by using an achiral bare fused silica capillary.

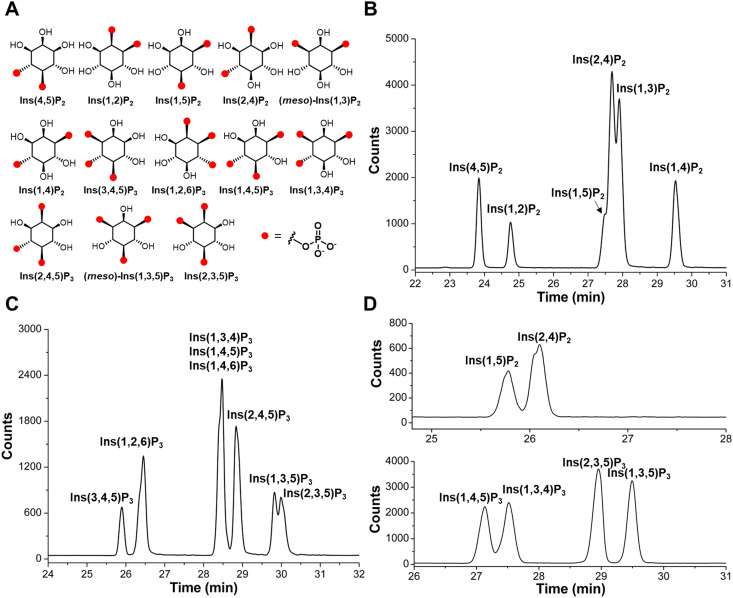

The set of commercial InsP2 and InsP3 are shown in Fig. 1A: Ins(4,5)P2, Ins(1,2)P2, Ins(1,5)P2, Ins(2,4)P2, Ins(1,3)P2, Ins(1,4)P2, Ins(3,4,5)P3, Ins(1,2,6)P3, Ins(1,3,4)P3, Ins(1,4,5)P3, Ins(2,4,5)P3, Ins(1,3,5)P3, Ins(2,3,5)P3. A bare fused silica capillary with a length of 100 cm was implemented for separations by applying 30 kV across the capillary (Agilent 7100 CE). Detection was achieved with an ESI-QQQ-MS (Agilent 6495C Triple Quadrupole with Agilent Jet Stream electrospray ionization source) in the negative ionization mode connected with an Agilent CE-ESI-MS interface. Initially, 35 mM ammonium acetate titrated with ammonium hydroxide to pH 9.75 was used as background electrolyte (BGE). With this BGE, separation of six InsP2 isomers is achieved, but Ins(1,5)P2, Ins(2,4)P2, and Ins(1,3)P2 were not baseline separated (Fig. 1B). Also, the separation of eight InsP3 isomers was achieved with the exception of Ins(1,3,4)P3, Ins(1,4,5)P3, and Ins(1,4,6)P3 (Fig. 1C). After pH optimization and BGE screening, a near baseline separation of Ins(1,5)P2 and Ins(2,4)P2 was achieved with 50 mM ethylamine titrated with formic acid to pH 10.0 (Fig. 1D). Separation of previously coeluting Ins(1,3,4)P3 and InsP(1,4,5)P3 was also resolved using this BGE (Fig. 1D) and a baseline separation of InsP(1,3,5)P3 and Ins(2,3,5)P3 was achieved as well (Fig. 1D). Ins(1,4,6)P3 still coeluted with Ins(1,4,5)P3.

Fig. 1. Separation of InsPs by CE-ESI-MS. (A) Structures of commercial InsP2 and InsP3 isomers. Achiral isomers are labeled as “meso”. (B and C) Separation of InsP2 and InsP3 standards by CE-ESI-MS, BGE: 35 mM ammonium acetate titrated with ammonium hydroxide to pH 9.75. (D) Separation of InsP2 and InsP3 standards by CE-ESI-MS, BGE: 50 mM ethylamine titrated with formic acid to pH 10.0.

Method validation was performed with InsP standards, including linearity, limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ). The external calibration curves of InsP2 and InsP3 were constructed at eight concentration levels by regression of concentrations against the analyte peak area (Fig. S1, ESI†). The calibration curves were linear and had a coefficient of determination >0.997 over the investigated range of 0.1–10 μg mL−1 for Ins(1,2)P2 and 0.4–40 μg mL−1 InsP(1,2,6)P3. With 20 nL sample injection, the LODs are 0.025 μg mL−1 for InsP2 (i.e. 1.3 fmol) and 0.020 μg mL−1 for InsP3 (i.e. 0.8 fmol), the LOQs are 0.05 μg mL−1 for InsP2 (i.e. 2.6 fmol) and 0.10 μg mL−1 for InsP3 (i.e. 4 fmol; Fig. S1, ESI†). The limit of detection of this method is significantly lower compared to other chromatography-related methods summarized in ref. 35.

RipBL1 degrades InsP6 to Ins(1,2,3)P3

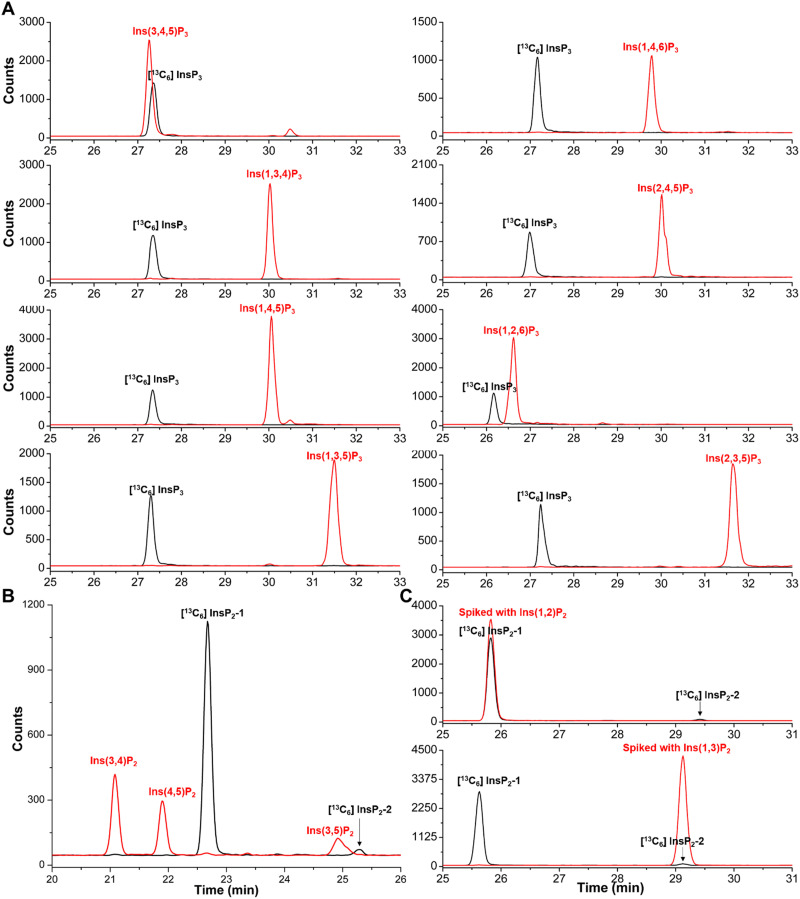

RipBL1 is an effector protein of the phytopathogenic Gram-negative bacteria Ralstonia solanacearum, that shares homology with the bacterial effector XopH from Xanthomonas campestris. Previous work demonstrated that XopH displays an unusual phytase activity that dephosphorylates InsP6 stereoselectively at the C1 position only, resulting in the generation of Ins(2,3,4,5,6)P5.32 We tested InsP6 dephosphorylation by phytases, such as RipBL1 in vitro, to see if we could generate more high-quality non-commercial standards. Importantly, after 45 min 100% of InsP6 was degraded by RipBL1, and one defined InsP3 was detected as constituting about 95% of the digestion product. There was very little dephosphorylation to InsP4 and InsP2 (Fig. S2B, ESI†). CE-qTOF-MS analyses of the enzymatic reaction product confirmed a main molecular ion peak at m/z 418.9551 corresponding to InsP3 (Fig. S2A, ESI†). To structurally assign the InsP3 product, we generated a [13C6] InsP3 by [13C6] InsP633 digestion with RipBL1, and then analyzed its identity through spiking-in of all commercially available InsP3 standards. As shown in Fig. 2A, the [13C6] InsP3 was baseline separated from all commercially available InsP3 standards, with the exception of Ins(3,4,5)P3 but also for this isomer, there was no perfect comigration. Previous work suggests that pyrohydrolysis can partially degrade “higher” InsPs and generate”lower” InsPs through dephosphorylation, and the pyrohydrolysis does not cause phosphate migration.19,36 Analysis of pyrohydrolysis products of Ins(3,4,5)P3 and the [13C6] InsP3 solution after heating to 100 °C for 2.5 h confirmed that [13C6] InsP3 is different from Ins(3,4,5)P3, as the labeled vs. non-labeled InsP2 products were different (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Identification of the InsP3 (black line) dephosphorylation product of [13C6] InsP6 by the RipBL1 enzyme. (A) CE-ESI-MS analysis of InsP3 individually spiked (red line) with Ins(3,4,5)P3 standard, Ins(1,4,6)P3 standard, Ins(1,3,4)P3 standard, Ins(2,4,5)P3 standard, Ins(1,4,5)P3 standard, Ins(1,2,6)P3 standard, Ins(1,3,5)P3 standard or Ins(2,3,5)P3 standard, as indicated. (B) Analysis of InsP2 generated from Ins(3,4,5)P3 and the [13C6] InsP3 isomer by heating to 100 °C for 2.5 h. Extracted ion electropherograms of [13C6]-labelled InsP2 (black lines) generated by [13C6] InsP3 and InsP2 (red trace) generated by Ins(3,4,5)P3. (C) [13C6] InsP2 (black line) generated from [13C6] InsP3 after heating to 100 °C for 2.5 h spiked with Ins(1,2)P2 standard or Ins(1,3)P2 standard as indicated (red line). Note that the [13C6] InsP2-1 isomer has the same migration time as the Ins(1,2)P2 standard and that the [13C6] InsP2-2 isomer has the same migration time as the Ins(1,3)P2 standard.

As Ins(4,5,6)P3, Ins(2,3,6)P3 (or its enantiomer Ins(1,2,4)P3), as well as the meso-compounds Ins(1,2,3)P3, and Ins(2,4,6)P3 were not readily available, the further assignment was performed differently. We compared the migration time of [13C6] InsP3 with the pyrohydrolysis products of Ins(2,3,5,6)P4 and Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 solution, respectively. The [13C6] InsP3 product of RipBL1 does not comigrate with any InsP3 isomers found as pyrohydrolysis products of Ins(2,3,5,6)P4 or Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 (Fig. S3, ESI†). These results provide evidence that the identity of the [13C6] InsP3 product is either Ins(1,2,3)P3 or Ins(2,4,6)P3, both of which are symmetric meso-compounds.

Pyrohydrolysis products of Ins(1,2,3)P3 and Ins(2,4,6)P3 are expected to be different. For Ins(1,2,3)P3, three InsP2, namely Ins(1,2)P2, Ins(2,3)P2 and Ins(1,3)P2, should be the pyrohydrolysis products. On the other hand, Ins(2,4)P2, Ins(2,6)P2, and Ins(4,6)P2 would be the expected pyrohydrolysis products of Ins(2,4,6)P3. By comparing the electrophoretic mobility with the commercially available InsP2 standards, two InsP2 peaks were identified as Ins(1,2)P2 and its enantiomer Ins(2,3)P2 (major product) as well as Ins(1,3)P2 (minor product) in the pyrohydrolysis solution of [13C6] InsP3 (Fig. 2C). Consequently, [13C6] InsP3 generated by RipBL1 treatment of [13C6] InsP6 represents Ins(1,2,3)P3.

Dephosphorylation of InsP6 by different types of phytases to produce Ins(1,2,3)P3, either as the final product or as intermediates, has been investigated.37–41 Ins(1,2,3)P3 as an intermediate in barley aleurone tissue was described as well.42 That InsP6 metabolism by phytase in plants and fungi might pass through Ins(1,2,3)P3 was discussed.18 Ins(1,2,3)P3 as the final product of InsP6 hydrolysis, as shown for RipBL1, is however unusual, only alkaline phytase from Lily Pollen is a candidate enzyme but the Ins(1,2,3)P3 purity was not described.38 Thus, to the best of our knowledge, RipBL1 is the first bacterial effector phytase that with high selectivity and yield generates Ins(1,2,3)P3.

Ins(1,2,3)P3, Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or its enantiomer Ins(2,3,4)P3 exist in human kidney stones and urine

Kidney stones are solid objects in the kidney or bladder that can cause different disease symptoms and consist of various low molecular weight compounds as well as proteins.43 Further, kidney stones can be categorized into calcium containing stones and non-calcium containing stones. Calcium containing stones are the most common forms of kidney stones, including calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) or dihydrate (COD) as well as calcium phosphate and mixtures of these.43 The formation of kidney stones is mainly driven by urinary supersaturation and crystallization. These processes are environment dependent, influenced by urine pH, concentration of specific substances and effective molecules (promoters, and inhibitors of kidney stone formation).44 Studies have shown that for example urinary InsP6 can inhibit crystallization during the process of kidney stone formation in a model system.45–48 Recently, InsP6 analogues with PEG modifications were reported to completely inhibit such crystallization processes in the nanomolar range.49 Additionally, studies with SNF472 (a hexasodium salt of InsP6) as an inhibitor of vascular calcification in a phase 2 clinical trial are ongoing,50 highlighting a strong relationship between InsP6 and calcification. Whether some other inositol phosphates might actually promote crystallization and whether these substances are then incorporated into the kidney stone has not been studied. We therefore asked the question if InsP6 or other InsPs could be structural components of kidney stones.

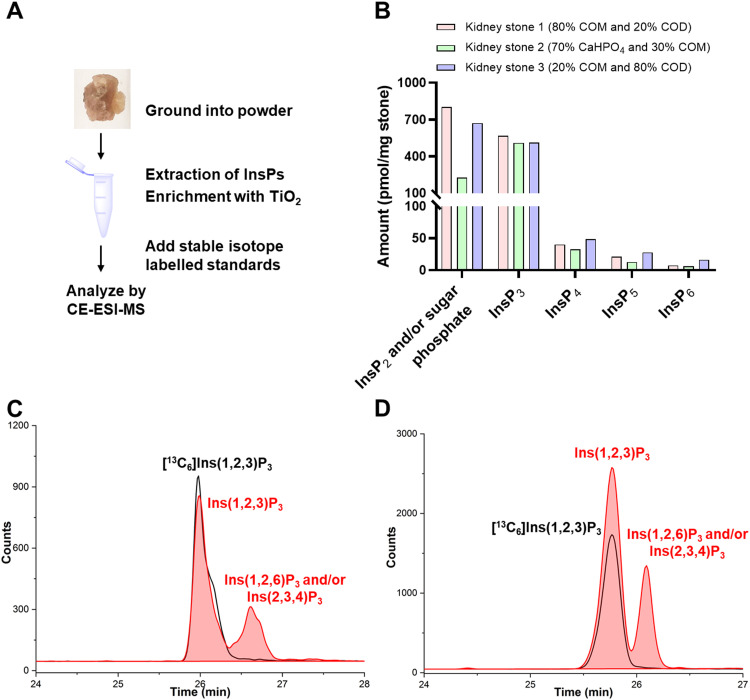

To investigate the presence and profiles of InsPs in kidney stones, different ground kidney stones of several compositions (calcium oxalate * xH2O (x = 1 COM, x = 2 COD) and calcium hydrogen phosphate (CaHPO4)), determined by IR spectroscopy, were extracted with perchloric acid according to the reported TiO2 purification method51 and then analyzed by CE-ESI-MS (Fig. 3A).6 We identify several InsPs as part of kidney stones providing the first such profiles (for a representative example see Fig. S4, ESI†). The high-resolution masses of the InsPs were confirmed by a CE-qTOF analysis (Fig. S5, ESI†). Some of the InsP isomers were identified with internal [13C6] labelled reference compounds. Fig. 3B summarizes the observed levels of different InsPs in calcium oxalate stones (kidney stone 1 contains 80% COM and 20% COD, kidney stone 3 contains 20% COM and 80% COD) and a calcium phosphate stone (kidney stone 2 contains 70% CaHPO4 and 30% COM), which roughly show the same trend in abundance of the analytes.

Fig. 3. Profiling of InsPs in human kidney stones. (A) Extraction and analysis workflow of kidney stones for CE-ESI-MS. (B) InsPs distribution in kidney stone 1 (contains 80% COM and 20% COD), kidney stone 2 (contains 70% CaHPO4 and 30% COM) and kidney stone 3 (contains 20% COM and 80% COD) from three different patients. (C) Extracted ion electropherograms of [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (black line) and InsP3 in kidney stone 1 (red area). (D) Extracted ion electropherograms of [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (black line) and InsP3 in kidney stone 2 (red area).

While inositol pyrophosphates were not detectable in these three types of calcium containing kidney stones, we noticed a decrease in InsP abundance proportional to the number of phosphate groups. InsP6 was the least abundant InsP followed by InsP5 and InsP4 isomers. One of the InsP5 isomers was assigned as 2-OH InsP5 (Fig. S4, ESI†) by spiking with an internal [13C6] reference. The most abundant InsP detected in kidney stone were InsP2–3 species and or isobaric sugar bisphosphates.

Full recovery for InsP6–7 and good recovery for 2-OH InsP5 from mammalian cell extracts were reported previously.6 Here our analysis shows good recovery for InsP6 (84%), 2-OH InsP5 (70%) and InsP3 (71%) from kidney stone extracts (kidney stone 2 is used as a representative example) by spiking with the [13C6] reference before extraction (pre-spiking) and after extraction but before measurement (post-spiking) (Fig. S6, ESI†). Since kidney stones are rich in Ca2+, which could affect InsP recovery, we reassessed TiO2 mediated InsP retrieval by adding 15 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) during extraction. However, the recovery of InsP6 and InsP3 did not critically rely on presence or absence of additional EDTA.

Three peaks belonging to InsP2 and/or isobaric sugar bisphosphates were separated in kidney stone (Fig. S7, ESI†). Spiking indicated that none of these three peaks represents glucose-1,6-bisphosphate. The most intense peak has an identical migration time with [13C6] Ins(1/3,2)P2 generated by pyrohydrolysis from [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (Fig. S7, ESI†), indicating Ins(1,2)P2 and/or Ins(2,3)P2 are present in kidney stones. This is in line with recent findings that Ins(2,3)P2 is present in the μM range in immortalized mammalian cells.27

InsP3 was also comparably abundant in the calcium containing stones. Two peaks of InsP3 were recorded and identified as Ins(1,2,3)P3, representing the most intense peak, and Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or its enantiomer Ins(2,3,4)P3. Identification was achieved by spiking with [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (Fig. 3C and D) and Ins(1,2,6)P3 (Fig. S8, ESI†). Ins(1,2,3)P3 was reported in mammalian cell models in a concentration range of 1–10 μM.18 A possible role for Ins(1,2,3)P3 as an intracellular iron chelator in the process of iron transport has been considered.52,53 Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or the enantiomer Ins(2,3,4)P3 was proposed in mammalian B-cells in 1992,54 however, as discussed above, since then very few studies have been conducted to characterize their identity and functional roles and these isomers are missing in discussions in recent literature reviews.21,22

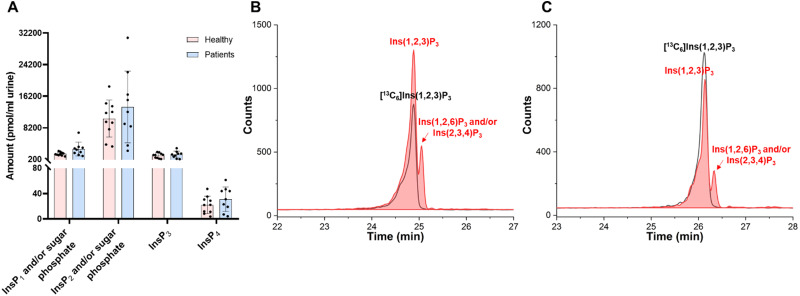

The formation of kidney stone is a result of urinary supersaturation and crystallization. To study potential correlations of the profiles of InsPs in kidney stones and urine, we additionally profiled InsPs in 0.4 mL urine samples both from patients who have kidney stones (9 urine samples from different donors) and matched healthy people (10 urine samples from different donors, Table S1, ESI†). The accurate masses of InsPs identified in urine samples were confirmed by a CE-qTOF analysis (for representative example see Fig. S9 and S10, ESI†). Since we cannot yet distinguish sugar mono and bisphosphates from InsP1 and InsP2 because of limitations of our current method, we must assume that m/z 259.0229 and m/z 338.9889 correspond to InsP1 and/or sugar phosphates and InsP2 and/or sugar bisphosphates, respectively. CE-QQQ was then used to profile InsP levels also in urine samples. The CE-QQQ results indicated that InsP2 and/or sugar bisphosphates are the most abundant species, followed by InsP1 and/or sugar phosphates. Interestingly, InsP3 was in the same concentration range as the sugar phosphates/InsP1 group of analytes and InsP4 was also present in the samples, but much less concentrated (ca. 7–8 fold) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. InsPs in urine samples from patients with kidney stones vs. healthy people. (A) InsPs distribution in urine samples: ten samples from healthy individuals, and nine samples from patients with kidney stones. (B) Extracted ion electropherograms of [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (black line) and InsP3 in urine from patients (red trace). (C) Extracted ion electropherograms of [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (black line) and InsP3 in urine from healthy individuals (red trace).

InsP6 was detectable in five of the urine samples from ten healthy people and only one of the urine samples from nine kidney stone patients. In all cases, the concentration of InsP6 was lower than the limit of quantification (LOQ). 2-OH InsP5 was also in between the LOD and LOQ in seven of the urine samples from ten healthy people and only three of the urine sample from nine kidney stone patients. According to the signal-to-noise of spiked 1 μM [13C6] InsP6 and [13C6] 2-OH InsP5, we determined limits of detection (LOD) of InsP6 and 2-OH InsP5 in the urine samples analyzed were approx. 7.5 nM and 1.5 nM InsP5, respectively. Limits of quantitation (LOQ) of InsP6 and 2-OH InsP5 were approx. 22.5 nM and 4.5 nM, respectively. Therefore, less than 7.5 nM of InsP6 exist in most of these urine samples, which is in accordance with the reported detection using InsPs specific assays.51,55,56 In half of these samples, approx. 1.5 nM to 4.5 nM 2-OH InsP5 exist. InsP4 were also present in urine samples. InsP5 and InsP4 received little attention so far in human urine, and our results provide an initial overview of these species. A study of InsPs in rat urine after giving InsP6 dietary treatment indicated that InsP6 as well InsP2, InsP3, InsP4 and InsP5 is excreted in the urine.55 The source of those isomers remains obscure.

Similar to the results obtained for kidney stones, InsP2 and/or sugar bisphosphates are most abundant. The most intense species comigrates with [13C6] Ins(1/3,2)P2 generated by pyrohydrolysis of [13C6] Ins(1,2,3)P3 (Fig. S9, ESI†). Also in agreement with the results found in kidney stones, two peaks corresponding to the mass of InsP3 in urine samples can be identified as Ins(1,2,3)P3 and Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or the enantiomer Ins(2,3,4)P3 (Fig. 4B, C and Fig. S11, ESI†). According to our current data set, there is no significant difference of InsPs and/or sugar phosphates in urine from patients and healthy people regarding levels of InsP1 to InsP4. For InsP5–6 the picture is less clear as the measured concentrations were in between our current LOD and LOQ for most samples.

Conclusions

We have developed a CE-MS method to separate “lower” InsPs, particularly focusing on InsP2 and InsP3. Using this method combined with a pyrohydrolysis strategy, we were able to delineate the identity of a major human InsP3, i.e. Ins(1,2,3)P3 in urine and kidney stones. To achieve this goal, a phytase (RipBL1) was used that selectively degrades InsP6 to Ins(1,2,3)P3 and that also served for production of a 13C labelled Ins(1,2,3)P3 internal reference. Our profiling of InsPs in human kidney stone and urine also unveiled Ins(1,2,6)P3 and/or the enantiomer Ins(2,3,4)P3 besides the major Ins(1,2,3)P3. Importantly, the assignments of InsP3 are based on an accurate mass determination and comigration with standards. As a next step, further studies must delineate the stereoisomeric identity of the newly identified InsP3, since chiral selectors have already been developed for certain InsP enantiomers for assignments by 31P NMR spectroscopy.32 Additionally, methods to distinguish InsP1 and InsP2 from sugar (bis)phosphates will have to be developed. Derivatization of sugar phosphates to separate them from InsPs could be considered.57 Further improvements in LOQs will be helpful to establish, if potentially InsP5 or InsP6 concentrations in urine can be used as biomarkers for kidney stone formation.

Ins(1,2,3)P3 was described in mammalian cells more than 25 years ago18,26 and other inositol phosphates with a phosphate ester in the 2-position clearly exist. However, the interest in these isomers in human biology has faded over time, and recent literature is not reporting on them anymore so their roles remain unresolved. Our study in combination with work from the Fiedler group27 demonstrates that Ins(2)Ps are abundant cellular, kidney stone and body fluid components. These discoveries warrant reassessment of the classically discussed InsP metabolism. New attention must be given to noncanonical InsP species to fully and properly appreciate the inositol phosphate code.

Author contributions

G. L., A. S., and H. J. J. designed research and wrote the paper. G. L., D. Q. and H. J. J. analyzed data, E. R., R. S., G. S., A. S., T. L. cloned and analyzed RipBL1, D. C., O. B., C. A. W., J. P. J., T. K. provided materials and analyzed data. All authors discussed the paper and provided input for the final version. Further Swiss Kidney Stone Cohort investigators are listed in the acknowledgments.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under Germany's excellence strategy (CIBSS-EXC-2189-Project ID 390939984, and DFG projects SCHA 1274/5-1 and LA 1338/12-1). HJJ and GL acknowledge funding from the Volkswagen Foundation (VW Momentum Grant 98604). AS acknowledges funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) grant MR/T028904/1. The Swiss Kidney Stone Cohort (SKSC) is sponsored by Swiss National Science Foundation through the National Center of Competence in Research Kidney.CH (grant number 183774). OB is supported by a SNF grant (number 182312). The authors wish to thank Dorothea Fiedler (Leibniz Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie, Berlin) and particularly Minh Nguyen Trung und Robert Harmel for providing 13C-labeled reference compounds. We are thankful to Nathalie Dufour and Iryna Bottcher who prepared the urine samples from SKSC. List of SKSC investigators: Harald Seeger and, Alexander Ritter, University Hospital Zurich; Olivier Bonny, Gregoire Wuerzner and Beat Roth, University Hospital Lausanne; Daniel Fuster and Nasser Dahyat, University Hospital Bern; Florian Buchkremer and Stephan Segerer, Kantonspital Aarau; Thomas Ernandez and Catherine Stoermann-Chopard, University Hospital Geneva; Carsten A. Wagner, University of Zurich.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cb00235c

References

- York J. D. Regulation of nuclear processes by inositol polyphosphates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1761(5–6):552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine R. F. Schell M. J. Back in the water: the return of the inositol phosphates. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2(5):327–338. doi: 10.1038/35073015. doi: 10.1038/35073015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto J. C. Kelly P. Chiou S. T. York J. D. Alterations in an inositol phosphate code through synergistic activation of a G protein and inositol phosphate kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(40):15653–15658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705729104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705729104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey C. M. Diep J. Clarke B. P. Hale A. T. McNamara D. E. Guo H. Brown, Jr. N. W. Cao J. Y. Grace C. R. Gough P. J. Bertin J. Dixon S. J. Fiedler D. Mocarski E. S. Kaiser W. J. Moldoveanu T. York J. D. Carette J. E. MLKL Requires the Inositol Phosphate Code to Execute Necroptosis. Mol. Cell. 2018;70(5):936–948 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.010. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Fujii N. Wittwer C. Sasaki A. Tanaka M. Bittner T. Jessen H. J. Saiardi A. Takizawa S. Nagata E. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the quantitative analysis of mammalian-derived inositol poly/pyrophosphates. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1573:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.08.061. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D. Wilson M. S. Eisenbeis V. B. Harmel R. K. Riemer E. Haas T. M. Wittwer C. Jork N. Gu C. Shears S. B. Schaaf G. Kammerer B. Fiedler D. Saiardi A. Jessen H. J. Analysis of inositol phosphate metabolism by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):6035. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19928-x. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. S. C. Saiardi A. Importance of Radioactive Labelling to Elucidate Inositol Polyphosphate Signalling. Top Curr Chem (Cham) 2017;375(1):14. doi: 10.1007/s41061-016-0099-y. doi: 10.1007/s41061-016-0099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprigg C. Whitfield H. Burton E. Scholey D. Bedford M. R. Brearley C. A. Phytase dose-dependent response of kidney inositol phosphate levels in poultry. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0275742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P. Gawaz M. Chatterjee M. Lämmerhofer M. Isomer-selective analysis of inositol phosphates with differential isotope labelling by phosphate methylation using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021:339286. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.339286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. Fridy P. C. Ribeiro A. A. Choi J. H. Barma D. K. Vogel G. Falck J. R. Shears S. B. York J. D. Mayr G. W. Structural analysis and detection of biological inositol pyrophosphates reveal that the family of VIP/diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate kinases are 1/3-kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(3):1863–1872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805686200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805686200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert C. Safrany S. T. Bembenek M. E. Reddy K. M. Reddy K. Falck J. Brocker M. Shears S. B. Mayr G. W. Biological variability in the structures of diphosphoinositol polyphosphates in Dictyostelium discoideum and mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 2):553–560. doi: 10.1042/bj3270553. doi: 10.1042/bj3270553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher B. A. P. Vanderhoeven R. A. M. Tjaden U. R. Andersson E. Vandergreef J. Analysis of Inositol Phosphates and Derivatives Using Capillary Zone Electrophoresis Mass-Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 1995;712(1):235–243. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00202-X. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00202-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher B. A. P. Hofte A. J. P. Tjaden U. R. vanderGreef J. On-line electrodialysis capillary zone electrophoresis mass spectrometry of inositol phosphates in complex matrices. J. Chromatogr. A. 1997;777(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00449-4. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00449-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riemer E. Qiu D. Laha D. Harmel R. K. Gaugler P. Gaugler V. Frei M. Hajirezaei M. R. Laha N. P. Krusenbaum L. Schneider R. Saiardi A. Fiedler D. Jessen H. J. Schaaf G. Giehl R. F. H. ITPK1 is an InsP6/ADP phosphotransferase that controls phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2021;14(11):1864–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.07.011. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D. Eisenbeis V. B. Saiardi A. Jessen H. J. Absolute Quantitation of Inositol Pyrophosphates by Capillary Electrophoresis Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Vis Exp. 2021;174:e62847. doi: 10.3791/62847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D. Gu C. Liu G. Ritter K. Eisenbeis V. B. Bittner T. Gruzdev A. Seidel L. Bengsch B. Shears S. B. Jessen H. J. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry identifies new isomers of inositol pyrophosphates in mammalian tissues. Chem. Sci. 2023;14:658–667. doi: 10.1039/D2SC05147H. doi: 10.1039/D2SC05147H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. P. Mills S. J. Potter B. V. The “Other” Inositols and Their Phosphates: Synthesis, Biology, and Medicine (with Recent Advances in myo-Inositol Chemistry) Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55(5):1614–1650. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502227. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker C. J. French P. J. Moore A. J. Nilsson T. Berggren P. O. Bunce C. M. Kirk C. J. Michell R. H. Inositol 1,2,3-trisphosphate and inositol 1,2- and/or 2,3-bisphosphate are normal constituents of mammalian cells. Biochem J. 1995;306(Pt 2):557–564. doi: 10.1042/bj3060557. doi: 10.1042/bj3060557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. C. Li B. W. Separation of phytic acid and other related inositol phosphates by high-performance ion chromatography and its applications. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;1018(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.08.040. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb H. Irvine R. F. Berridge M. J. Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306(5938):67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. Park S. J. Hong S. Kim K. Kim S. Inositol Polyphosphate Multikinase Signaling: Multifaceted Functions in Health and Disease. Mol. Cells. 2021;44(4):187–194. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2021.0045. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2021.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatree S. Thongmaen N. Tantivejkul K. Sitticharoon C. Vucenik I. Role of Inositols and Inositol Phosphates in Energy Metabolism. Molecules. 2020;25(21):5079. doi: 10.3390/molecules25215079. doi: 10.3390/molecules25215079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shears S. B. A Short Historical Perspective of Methods in Inositol Phosphate Research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2091:1–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0167-9_1. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0167-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale A. T. Clarke B. P. York J. D. Metabolic Labeling of Inositol Phosphates and Phosphatidylinositols in Yeast and Mammalian Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2091:83–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0167-9_7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0167-9_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker C. J. Wright J. Hughes P. J. Kirk C. J. Michell R. H. Complex changes in cellular inositol phosphate complement accompany transit through the cell cycle. Biochem J. 2004;380(Pt 2):465–473. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031872. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker C. J. Wright J. Kirk C. J. Michell R. H. Inositol 1,2,3-trisphosphate is a product of InsP6 dephosphorylation in WRK-1 rat mammary epithelial cells and exhibits transient concentration changes during the cell cycle. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1995;23(2):169S. doi: 10.1042/bst023169s. doi: 10.1042/bst023169s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Trung M. Kieninger S. Fandi Z. Qiu D. Liu G. Mehendale N. K. Saiardi A. Jessen H. Keller B. Fiedler D. Stable Isotopomers of myo-Inositol Uncover a Complex MINPP1-Dependent Inositol Phosphate Network. ACS Cent. Sci. 2022;8(12):1683–1694. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01032. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. S. Jessen H. J. Saiardi A. The inositol hexakisphosphate kinases IP6K1 and -2 regulate human cellular phosphate homeostasis, including XPR1-mediated phosphate export. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294(30):11597–11608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritoh Y. Abe S. I. Akiyama H. Kobayashi A. Koyama R. Hara R. Kasai S. Watanabe M. The enzymatic activity of inositol hexakisphosphate kinase controls circulating phosphate in mammals. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):4847. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24934-8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24934-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Gu C. Hostachy S. Sahu S. Wittwer C. Jessen H. J. Fiedler D. Wang H. Shears S. B. Control of XPR1-dependent cellular phosphate efflux by InsP8 is an exemplar for functionally-exclusive inositol pyrophosphate signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117(7):3568–3574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908830117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908830117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez U. Tury S. Nicolas G. Wilson M. S. Jurici S. Ayrignac X. Courgnaud V. Saiardi A. Sitbon M. Battini J. L. Interplay between primary familial brain calcification-associated SLC20A2 and XPR1 phosphate transporters requires inositol polyphosphates for control of cellular phosphate homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(28):9366–9378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher D. Laha D. Thieme S. Hofer A. Eschen-Lippold L. Masch A. Balcke G. Pavlovic I. Nagel O. Schonsky A. Hinkelmann R. Worner J. Parvin N. Greiner R. Weber S. Tissier A. Schutkowski M. Lee J. Jessen H. Schaaf G. Bonas U. A 1-phytase type III effector interferes with plant hormone signaling. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(1):2159. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02195-8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puschmann R. Harmel R. K. Fiedler D. Scalable Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Inositol Pyrophosphates. Biochemistry. 2019;58(38):3927–3932. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00587. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmel R. K. Puschmann R. Nguyen Trung M. Saiardi A. Schmieder P. Fiedler D. Harnessing (13)C-labeled myo-inositol to interrogate inositol phosphate messengers by NMR. Chem. Sci. 2019;10(20):5267–5274. doi: 10.1039/c9sc00151d. doi: 10.1039/c9sc00151d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marolt G. Kolar M. Analytical Methods for Determination of Phytic Acid and Other Inositol Phosphates: A Review. Molecules. 2020;26(1):174. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010174. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. Ion-exchange chromatography of inositol polyphosphates. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1969;165(2):677–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1970.tb56434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P. E. Tate M. E. The phytases. II. Properties of phytase fractions F 1 and F 2 from wheat bran and the myoinositol phosphates produced by fraction F 2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1973;302(2):316–328. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(73)90160-5. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(73)90160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos L. Scott J. J. Murthy P. P. Specificity of hydrolysis of phytic acid by alkaline phytase from lily pollen. Plant Physiol. 1994;106(4):1489–1495. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1489. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund W. D. Mayr G. W. Tietz C. Schultz J. E. Metabolism of inositol phosphates in the protozoan Paramecium. Characterization of a novel inositol-hexakisphosphate-dephosphorylating enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;207(1):359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17058.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kaay J. Van Haastert P. J. Stereospecificity of inositol hexakisphosphate dephosphorylation by Paramecium phytase. Biochem J. 1995;312(Pt 3):907–910. doi: 10.1042/bj3120907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T. Joh T. Narita K. Hayakawa T. The pathway of dephosphorylation of myo-inositol hexakisphosphate by phytases from wheat bran of Triticum aestivum L. cv. Nourin #61. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2000;64(5):995–1003. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.995. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brearley C. A. Hanke D. E. Inositol phosphates in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) aleurone tissue are stereochemically similar to the products of breakdown of InsP6 in vitro by wheat-bran phytase. Biochem J. 1996;318(Pt 1):279–286. doi: 10.1042/bj3180279. doi: 10.1042/bj3180279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alelign T. Petros B. Kidney Stone Disease: An Update on Current Concepts. Adv. Urol. 2018;2018:3068365. doi: 10.1155/2018/3068365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Zhang Y. Zhang J. Deng Q. Liang H. Recent advances on the mechanisms of kidney stone formation (Review. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021;48(2):149. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2021.4982. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2021.4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakier S. Rodgers A. Jackson G. Potential thermodynamic and kinetic roles of phytate as an inhibitor of kidney stone formation: theoretical modelling and crystallization experiments. Urolithiasis. 2019;47(6):493–502. doi: 10.1007/s00240-019-01117-1. doi: 10.1007/s00240-019-01117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw N. K. Chow K. Rao P. N. Kavanagh J. P. Effects of inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on calcium binding, calcium oxalate crystallization and in vitro stone growth. J. Urol. 2007;177(6):2366–2370. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.113. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grases F. Costa-Bauza A. March J. G. Artificial simulation of the early stages of renal stone formation. Br. J. Urol. 1994;74(3):298–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb16614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantl A. E. Verhulst A. Neven E. Behets G. J. D'Haese P. C. Maillard M. Mordasini D. Phan O. Burnier M. Spaggiari D. Decosterd L. A. MacAskill M. G. Alcaide-Corral C. J. Tavares A. A. S. Newby D. E. Beindl V. C. Maj R. Labarre A. Hegde C. Castagner B. Ivarsson M. E. Leroux J. C. Inhibition of vascular calcification by inositol phosphates derivatized with ethylene glycol oligomers. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):721. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14091-4. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kletzmayr A. Mulay S. R. Motrapu M. Luo Z. Anders H. J. Ivarsson M. E. Leroux J. C. Inhibitors of Calcium Oxalate Crystallization for the Treatment of Oxalate Nephropathies. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(8):1903337. doi: 10.1002/advs.201903337. doi: 10.1002/advs.201903337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S. Gould L. J. Nigwekar S. U. Serena T. E. Brandenburg V. Moe S. M. Aronoff G. Chatoth D. K. Hymes J. L. Miller S. Padgett C. Carroll K. J. Perello J. Gold A. Chertow G. M. The CALCIPHYX study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 clinical trial of SNF472 for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(1):136–144. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab117. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. S. Bulley S. J. Pisani F. Irvine R. F. Saiardi A. A novel method for the purification of inositol phosphates from biological samples reveals that no phytate is present in human plasma or urine. Open Biol. 2015;5(3):150014. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150014. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala M. Makuc D. Kolar J. Plavec J. Pihlar B. Potentiometric and (3)(1)P NMR studies on inositol phosphates and their interaction with iron(III) ions. Carbohydr. Res. 2011;346(4):488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.12.021. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga N. Torres J. Mansell D. Freeman S. Dominguez S. Barker C. J. Diaz A. Kremer C. “Chelatable iron pool”: inositol 1,2,3-trisphosphate fulfils the conditions required to be a safe cellular iron ligand. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009;14(1):51–59. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0423-2. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell F. M. Shears S. B. Lane P. J. Scheibel M. S. Clark E. A. Relationships between the degree of cross-linking of surface immunoglobulin and the associated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and Ca2+ signals in human B cells. Biochem J. 1992;284(Pt 2):447–455. doi: 10.1042/bj2840447. doi: 10.1042/bj2840447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grases F. Costa-Bauza A. Berga F. Rodriguez A. Gomila R. M. Martorell G. Martinez-Cignoni M. R. Evaluation of inositol phosphates in urine after topical administration of myo-inositol hexaphosphate to female Wistar rats. Life Sci. 2018;192:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.023. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher A. J. Schell M. J. Irvine R. F. Do mammals make all their own inositol hexakisphosphate. Biochem. J. 2008;416(2):263–270. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende U. Niittyla T. Moritz T. Two-step derivatization for determination of sugar phosphates in plants by combined reversed phase chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Methods. 2019;15:127. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0514-9. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.