Abstract

Introduction and importance

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (SLCT) are a rare sex cord–stromal tumors, accounting for <0,2 % of all ovarian malignancies. As these tumors are found at an early stage in young women, the whole management dilemma is finding the right balance between a treatment efficient enough to prevent recurrences but that still enables fertility-sparing.

Case presentation

We report the case of a 17 years old patient hospitalized in the oncology and gynecology ward of the university hospital Ibn Rochd in Casablanca, presenting a moderately differentiated Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor in the right ovary, our aim is to analyze the clinical, radiological and histological characteristics of this rare tumor that can be tricky to diagnose and review the different management therapies available and the challenges they present.

Clinical discussion

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (SLCT) are rare sex cord–stromal tumors that should not be misdiagnosed. The prognosis of patients with grade 1 SLCT is excellent without adjuvant chemotherapy. Intermediate and poorly differentiated SLCTs require a more aggressive management. Complete surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered.

Conclusion

Our case reaffirms that in the presence of a pelvic tumor syndrome and signs of virilization, SLCT should be suspected. The treatment is essentially surgical, if diagnosed early on, we can offer an effective treatment that preserves their fertility. Efforts should be focused on the creation of regional and international registries of SLCT cases in order to achieve greater statistical power in future studies.

Keywords: Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, Ovarian rare tumor, Virilization ovarian tumor, Fertility-sparing, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (SLCT) are a rare sex cord–stromal tumors that should not be misdiagnosed.

-

•

In the presence of a pelvic tumor syndrome and signs of virilization, SLCT should be suspected.

-

•

The treatment is essentially surgical, if diagnosed early on, we can propose an effective treatment that preserves their fertility.

-

•

The prognosis of patients with grade 1 SLCT is excellent without adjuvant chemotherapy.

-

•

Intermediate and poorly differentiated SLCTs require more aggressive management.

1. Introduction

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors (SLCT) are a rare sex cord–stromal tumors, accounting for <0,2 % of all ovarian malignancies [1]. They are more common in young women around 23 years, but can be found in women of all age [2], [3]. It is the most common virilizing ovarian tumor. The majority of these tumors are classified as stage I at the time of diagnosis. The age of the patient and stage of the disease are the most important factors in considering therapeutic management. As these tumors are found at an early stage in young women, fertility-sparing surgery is usually recommended [4].

Our aim is to report the case of a 17 years old patient hospitalized in the oncology and gynecology ward of the university hospital Ibn Rochd in Casablanca, presenting a moderately differentiated Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor in the right ovary, and to analyze the clinical, radiological and histological characteristics of this rare tumor that can be tricky to diagnose, and establish the therapeutic principles to be proposed to these patients of childbearing age to avoid recurrence and preserve fertility. We ensure that the work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [5].

2. Presentation of the case

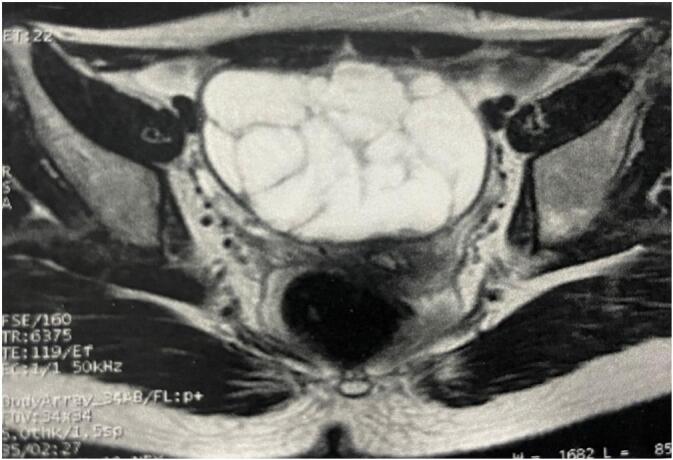

We present the case of a 17-year-old female patient, having no underlying medical condition, no drug history, who consulted for chronic pelvic pain, with progressive abdominal distension, an irregular menstrual cycle, and excessive hair growth on her face, chest, and limbs for the last 3 months. She was referred by her family physician. The clinical examination revealed a patient in good general condition, apyretic, with normal blood pressure and the presence of an abdominal mass. The rest of the physical examination revealed a hirsutism on her face, chest and limbs. At admission, her vital signs were normal. Pelvic ultrasound showed a pelvic cystic mass measuring 10 × 9 cm of probable adnexal origin suggesting an ovarian tumor. Doppler didn't reveal vascular invasion (Fig. 1). MRI showed a centro-pelvic right ovarian mass, multi-cystic, with well-defined walls and incomplete folds, measuring 102 × 87 mm classified ORADS 4; absence of abdomino-pelvic peritoneal effusion, absence of significant carcinosis nodule (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The MRI findings were suggestive of right ovarian epithelial neoplasm, and did not show significant abdominal lymphadenopathy or peritoneal deposits. A hormonal assessment showed excessive androgenic activity in the form of elevated serum testosterone level (2,5 ng/mL) however, levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), CA 125, CA 19-9, CA 15-3 and alphafetoprotein (AFP) were normal. Based on these findings, a provisional diagnosis of androgen-producing ovarian tumor was made. The patient was discussed at the gynecology multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting and the decision was to proceed to surgery and do an ovariectomy with staging surgery.

Fig. 1.

Echography showing a pelvic cystic mass measuring 10 × 9 cm of probable adnexal origin with doppler.

Fig. 2.

Transverse view of MRI showing a centro-pelvic right ovarian mass, multi-cystic, with well-defined walls and incomplete folds, measuring 102 × 87 mm classified ORADS 4.

Fig. 3.

Sagittal view of MRI showing a centro-pelvic right ovarian mass, multi-cystic, with well-defined walls and incomplete folds, measuring 102 × 87 mm classified ORADS 4.

3. Surgical technique and findings

The patient was admitted for laparoscopic exploration revealing a large solido-cystic right ovarian cyst with a thick wall, the right fallopian tube was of normal appearance as well as the left one, the left ovary and uterus, there were no pelvic adhesions, the abdominal cavity was regular, and no signs of carcinosis. The appendix, the liver, spleen, kidneys were normal on palpation, with no peritoneal nodules, but the presence of a small amount of ascites fluid.

We performed an omentectomy, peritoneal cytology and peritoneal biopsy by laparoscopy. This was undertaken by an experienced surgeon. Intra-operative frozen section was not done due to its reported controversy with the frequent diagnostic discordance between the frozen section and final pathology. Post-operative period was uneventful and the patient recovered smoothly, pain management accomplished via morphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) which was stopped on the first day, she started full diet on the first day also, and was discharged on the second post-operative day with no complains. A month after surgery, a hormonal assessment showed a return to normal testosterone levels, as well as the disappearance of signs of hirsutism, and a resumption of regular menstrual cycles in the months that followed. Her histopathology report showed a moderately differentiated Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor in the right ovary, the omentectomy, peritoneal biopsy and peritoneal cytology were free of malignant cells (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). It has been classified as stage IA (figo). The patient was once again discussed at the MDT meeting and it was decided to do a clinical, biological and radiological monitoring every three months for the first year. The patient was followed up for 3 years with no recurrence so far.

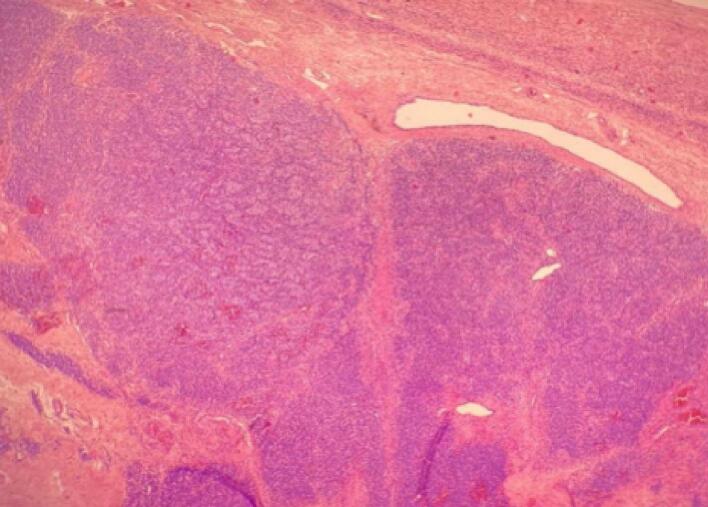

Fig. 4.

Leydig cellsorganized in cordons (magnification ×3).

Fig. 5.

Nest of Sertoli cells with some Leydig cells (magnification ×20).

4. Discussion

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are a rare sex cord–stromal tumors, accounting for <0,2 % of all ovarian malignancies [1]. They are more common in young women around 23 years, but can be found in women of all age [2], [3]. It is the most common virilizing ovarian tumor, with the usual and distinctive presenting complaints being abdominal pain and hormone-related symptoms.

4.1. When to suspect SLCT and how to diagnose it?

There is no pathognomonic symptom, it should be suspected in the presence of a tumor syndrome associated with signs of virilization, which can be found in 30 to 50 % of cases (hirsutism, hoarseness of the voice, defeminization of the figure and changes in psycho-sexual behavior, menstrual disorders such as oligo-menorrhea or even secondary amenorrhea, acne with hyperseborrhea, muscular hypertrophy, clitoral and labia majora hypertrophy) as was the case for our patient who presented hirsutism and menstrual disorders.

Much more rarely: patients in the prepubertal period may present manifestations of hyperestrogenism such as precocious pseudopuberty or menometrorrhagia and 50 % of the cases are asymptomatic, which can make it difficult to diagnose or suspect preoperatively [1], [2], [4], [6], [7]. This hypervirilization is reflected biologically by an increase in testosterone levels in nearly 80 % of cases. Blood testosterone levels above 200 ng/mL (7 nmol/L) are associated with androgen-secreting ovarian tumors, adrenal tumors or other origin [6], [7], [8].

Intraoperatively, these tumors are almost exclusively unilateral and limited to the ovary, about 10 % of cases present ovarian rupture and 4 % have ascites. Only 2 to 3 % of cases are metastatic at diagnosis, this mainly concerns poorly differentiated tumors. The size of the tumor is highly variable: up to 35 cm, with an average size of 12–14 cm [1], [6]. The imagery, in particular the ultrasound, is an efficient tool that can help with preoperative exploration without being able to confirm the type of tumor [9], [10], [11]. SLCTs appear as heterogeneous vascularized masses with solid areas; in pure Sertoli cell forms, they are frequently multiloculated, associated with anechoic fluid areas. CT, MRI and PET scans are mainly used to characterize the tumor and allow for an assessment of the tumor extension [9], [10], [11]. Macroscopically, SLCT most often present as a purely solid form, the external appearance is smooth. On section, the solid areas have a yellowish appearance with a soft, fleshy consistency. In large tumors, there is often an associated cystic contingent, in which case the external appearance remains smooth but lobulated. The cysts are multilocular with clear fluid liquid content. Their walls appear more rigid than in benign or borderline epithelial tumors. There may be necrotic-hemorrhagic areas [12]. There are four classifications of SLCT according to the World Health Organization (WHO): well, intermediate and poorly differentiated, and reform (those with heterologous element) [13].

4.2. What management can we propose our patients and what is the prognosis of SLCTs?

The majority of these tumors are classified as stage I at the time of diagnosis. The age of the patient and stage of the disease are the most important factors in considering the management of the case. As these tumors are found at an early stage and in young women, fertility-sparing surgery is usually recommended. Stage and grade of the disease are important prognostic factors for disease recurrence.

Management of patients with SLCT of the ovary can be challenging because there are no standard. Based on the review of the available literature, the following are the surgical recommendations [4]. It is well known that the well-differentiated forms of SLCTs are always benign and most of them are confined to one ovary, hence in young women where fertility is a concern, fertility sparing surgery such as unilateral oophorectomy is appropriate [14], [15]. A formal staging procedure should be considered in all patients, particularly with intermediate and high-grade tumors. Due to the rarity of the tumor, there have been no randomized trials to evaluate the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for SLCT of the ovary. Based on limited studies, it has been postulated that patients who have poor prognostic factors, such as tumor spread beyond the ovary, and those with intermediate and poor differentiation should be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [2], [4], [15]. Bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) appears to be an active combination regimen for first-line chemotherapy [16], [17]. Other chemotherapy regimens used in the literature are alkylating agents, adriamycin, CAP (cisplatin, adriamycin and cyclophosphamide) and PVB (cisplatin, vinblastine and bleomycin) [18], [19]. Regarding radiotherapy, there lacks definitive evidence if these tumors are radiosensitive. The prognosis for well-differentiated forms is excellent with a five-year survival of 100 %; in moderately to poorly differentiated forms, the five-year survival drops to 80 %. When the tumor remains localized to the ovary, the five-year survival is 95 %, whereas for metastatic forms it is close to 0 % [20]. Despite the good prognosis of SLCT, it has been reported that the relapse rate ranges from 0 % to 33.3 % [2], [4], [21], [22]. In contrast to other SCST such as ovarian granulosa cell tumors, SLCT tend to relapse early, usually in the pelvis or the abdomen, with a relapse rate of 95 % within 5 years [22]. The literature also reports a very poor prognosis for relapse, with a salvage rate of <20 % for clinically malignant and recurrent disease [22], [23]. Multi-modal treatment with surgery and chemotherapy appears to be the best approach. However, the best chemotherapy remains to be defined, and equivalence should be sought in terms of activity with reduced toxicity [22].

5. Conclusion

SLCT diagnosis can be challenging. They are mostly diagnosed at an early stage which makes their treatment essentially surgical, and the fertility sparing surgery possible. It's a tumor characterized by a good prognosis.

Multi-modal treatment with surgery and chemotherapy, when the tumor is advanced or poorly differentiated, appears to be the best approach. However, the best chemotherapy remains to be defined, and equivalence should be sought in terms of activity with reduced toxicity. Efforts should be focused on the creation of regional and international registries of SLCT cases in order to achieve greater statistical power in future studies.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

The case report was ethically approved by the ethical committee of our university Hassan 2 of Casablanca.

Sources of funding

We have no sources of funding.

Author contribution

Chadia Khalloufi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing Original draft preparation, Reviewing and Editing.

Imane Joudar: Writing, Reviewing and Editing.

Aya Kanas: Writing, Reviewing and Editing.

Mohammed Benhessou: Supervision.

Mohammed Ennachit: Supervision.

Mohammed El Kerroumi: Validation.

Guarantor

Khalloufi Chadia.

Research registration number

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Young R.H., Scully R.E. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. A clinicopathological analysis of 207 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1985;9:543–569. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth L.M., Anderson M.C., Govan A.D., Langley F.A., Gowing N.F., Woodcock A.S. Sertoli-leydig cell tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Cancer. 1981;48:187–197. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<187::aid-cncr2820480130>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan T.J., Leey S., Achesonz A.G., Hammond R.H. An ovarian stromal tumor with luteinized cells: an unusual recurrence of an unusual tumor. 2007 IGCS and ESGO. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:168–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat Rani Akhil, LIM Yong Kuei, Chia Yin Nin, et al. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor of the ovary: analysis of a single institution database. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2013;39:305–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. International Journal of Surgery. 2020;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandone N., Borrione C., Rome A., de Paula A.M. Annals of Pathology. Vol. 38. 2018. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig tumor: a tricky tumor; pp. 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prunty F.T. Hirsutism: virilism and apparent virilism and their gonadal relationship. II. J. Endocrinol. 1967;38:203–227. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0380203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meldrum D.R., Abraham G.E. Peripheral and ovarian venous concentrations of various steroid hormones in virilizing ovarian tumors. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979;53:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demidov V.N., et al. Imaging of gynecological disease (2): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of sertoli cell tumors, sertoli-leydig cell tumors and leydig cell tumors. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;31(1):85–91. doi: 10.1002/uog.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai S.-Q., Zhao S.-H., Qiang J.-W., Zhang G.-F., Wang X.-Z., et al. Ovarian Sertoli—Leydig cell tumors: MRI findings and pathological correlation. J. Ovarian Res. 2013;6:73. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung S.E., Rha S.E., Lee J.M., et al. CT and MRI findings of sex cord-stromal tumor of the ovary. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;185:207–215. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mory N., Juan C.F., Louis D. Histogenesis and histopathological characteristics of sertoli-leydig cell tumors. CME J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002;7:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen V.W., Ruiz B., Killeen J.L., Coté T.R., Wu X.C., Correa C.N. Pathology and classification of ovarian tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(10 Suppl):2631–2642. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson N., Osborn S., Youngh R.H. Sex cord-stromal tumours of the ovary: a review highlighting recent advances. Diagn. Histopathol. 2008;14:388–400. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietro L., Carlo S., Lorena C., et al. Sertoli-leydig cell tumors: current status of surgical management: literature review and proposal of treatment. Gynecol.Endocrinol. 2013;29(5):412–417. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.754878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen F.Y., Sheu B.C., Lin M.C., Chow S.N., Lin H.H. SertoliLeydig cell tumor of the ovary. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2004;103:388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sachdeva P., Arora R., Dubey C., Sukhija A., Daga M., Sing D.K. Sertoli-leydig cell tumor: a rare ovarian neoplasm. Case report and review of literature. Gynaecol. Endocrinol. 2008;24:230–234. doi: 10.1080/09513590801953465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddick R.L., Walton L.A. Sertoli-leydig cell tumor of the ovary with teratomatous differentiation.Clinicopathologic considerations. Cancer. 1982;50:1171–1176. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820915)50:6<1171::aid-cncr2820500623>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth B.J., Greist A., Kubilis P.S., Williams S.D., Einhorn L.H. Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy for disseminated germ cell tumors: long-term follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 1988;6:1239–1247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.8.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigismondi C., Gadducci A., Lorusso D., Candiani M., Breda E., Raspagliesi F., et al. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. a retrospective MITO study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:673–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.024. Epub 2012 Mar 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombo Nicoletta, et al. Management of ovarian stromal cell tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(20):2944–2951. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nef James, Huber Daniela Emanuela. Ovarian sertoli-leydig cell tumours: a systematic review of relapsed cases. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021;263:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouy S., Arfi A., Maulard A., et al. Results from a monocentric long-term analysis of 23 patients with ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Oncologist. 2019;24:702–709. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]