Summary

The manufacturing and consumption of plastic products have steadily increased over the past decades due to rising global demand, resulting not only in the depletion of petroleum resources but also increased environmental pollution due to the non-biodegradable nature of conventional plastics. Moreover, despite being introduced into the market as an alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics, biobased plastics are mainly manufactured from agricultural crop-based sources, which has negative impacts on the environment and the livelihoods of people. Marine-derived bioplastics are becoming a promising and cost-effective solution to the rising demand for plastic products. The physicochemical, biological, and degradation properties of marine-derived bioplastics have made them promising substances for many applications. However, more research is required for their large-scale implementation. Therefore, this review summarizes the raw materials of marine-derived bioplastics such as algae, animals, and microorganisms, as well as their extraction processes and properties. These insights could thus accelerate the production of marine-derived bioplastics as a novel alternative to prevailing bioplastics by taking advantage of marine biomass.

Subject areas: Natural resources, Aquatic science, Oceanography

Graphical abstract

Natural resources; Aquatic science; Oceanography

Introduction

Plastics derived from petrochemicals, coal, natural gas, or oil, are among the most useful synthetic materials produced in the 20th century. These materials have revolutionized our lives in many ways by opening avenues for significant developments in several industries. Plastic production has grown exponentially due to population growth and technological advancements, in addition to its remarkable versatility, stability, strength, durability, resistance to corrosion and heat, lightness, and low cost.1,2 According to the global plastic industry statistics, global plastic production is projected to reach 445 million tons in 2025 and further increase to 589 million metric tons by 2050.3 Despite their various advantages, plastics have become the main environmental concern of the 21st century due to the depletion of petroleum resources and the high resistance of plastics to biological degradation. Due to the hydrophobic nature and lack of naturally occurring microorganisms with enzymes capable of their degradation, the accumulation of plastic residues has become a major environmental issue.4,5

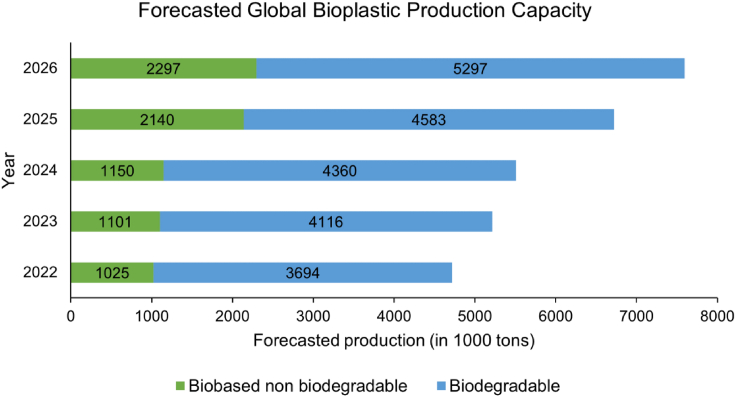

Therefore, there is a critical need to overcome these challenges and promote sustainable ways to manufacture bioplastics from natural renewable biomass sources such as terrestrial plants, marine sources, and microorganisms. Bioplastics feature a minimal carbon footprint, high recycling ability, and biodegradability or compostability. According to the “Green Guides” issued by the United States Federal Trade Commission, biodegradable products will completely decompose into the elements found in nature within a short or long period, and the term “compostability” applies to organic materials that break down in certain environments within a defined period.6 Biobased plastics with C-O, and C-N inter-unit chemical bonds are easily accessible and heteroatom-rich, contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption during production compared to petroleum-derived feedstocks over their lifetime.7 The main types of commercially available bioplastics (Table 1) include starch-based plastics, cellulose-based plastics, polylactic acid (PLA), polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), and bio-polybutylene succinate (PBS). According to 2021 market data collected by European Bioplastics in cooperation with the nova-Institute, the global bioplastics production capacity will increase from 2.4 million tons in 2022 to 7.5 million tons by 2026 as an alternative to traditional plastics (Figure 1).8 Nevertheless, bioplastics manufactured from terrestrial plant-based sources such as corn starch, sugar cane, potato, and banana peels represent less than 1% of the total annual plastic production due to their drawbacks such as brittleness, inferior toughness, structural integrity, and thermal stability, low strength, and high production cost.9,10 Terrestrial plant sources have many limitations that make them unsuitable for large-scale bioplastic production. For example, their growth rate depends largely on weather conditions and seasons, and the cultivation process often requires large amounts of fertilizer and pesticides. Additionally, allocating lands for bioplastic production would inevitably compete with the production of food crops, thus jeopardizing food security.11 Furthermore, the biodegradability of these biobased plastics is limited to specific conditions such as temperature, pressure, moisture, airflow, and other environmental factors.

Table 1.

Classification of commercial bioplastics

| Basis of Source | Source Material | Bioplastic Name | Monomer | Bioplastic manufacturers | Degradability | Tensile strength (MPa) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial plant-based | Corn starch, potato peels, banana peels, and cassava | Mater-Bi, Solanyl BP (Starch-based plastic) | Glucose | Novamont, Solanyl |

Completely biodegrade after six months (industrial composting) | 8.2 | Lackner, 201512 |

| Lactic acid, wastepaper | Polylactic acid (PLA) | Lactic acid (LA) | NatureWorks | Industrial compostability within 6-9 weeks at 60°C and in ocean for more than 1 year. | 21-60 | Lackner, 2015, Mensch, 201812,13 | |

| Glucose, microorganisms | Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) | Hydroxyalkanoates | Danimer Scientific, Nodax, ENMAT | Industrial compostability within 4-6 weeks at 60°C and in seawater within 1-6 months at 30 °C. | 15-40 | Lackner, 201512 | |

| Sugarcane, cassava, corn | Bio-Polybutylene succinate (Bio-PBS) | Succinic acid (SA), 1,4-butanediol | Mitsubishi Chemicals | Industrial compostability within more than 3 months and in seawater within 1-6 months at 30 °C. | 31 | Morinval and Averous, 202114 | |

| Marine-based | Seaweeds | Seaweed-based bioplastics | – | Evoware, Marine Innovation, Notpla, B’Zeos, SWAY, C-Combinator, FlexSea, Oceanium, Loliware, SoluBlue, and Kelpi | Dissolves in water | >9.6 | Evoware, 15 |

| Shrimp shell and silk protein | Shrilk | Glucosamine | Shrilk | Degrades rapidly when placed in compost, releasing nitrogen-rich nutrient fertilizer. | 119 | Fernandez and Ingber, 201216 | |

| Langoustine shells | CuanSave | Glucosamine | CuanTec | Degrade within 3 months in soil | – | CuanTec, 202217 | |

| Chitosan from seafood waste | Shellmer | Glucosamine | Shellworks | Dissolves in hot water | – | Shellworks, 202318 | |

| Fish skin, scale, and red algae | Marinatex | Galactose and collagen | Marinatex | Degrade within 4-6 weeks in a soil environment | >32 | MarinaTex, 19 |

Figure 1.

Forecast of global bioplastic production capacity from 2022 to 2026, adapted with modification from European Bioplastics

The above-described factors lead to high production costs and the accumulation of plastic waste. This highlights the need for the development of bioplastics derived from more sustainable and renewable biomass with a fast growth rate, easy cultivation, reduced cost, and easy biodegradability, whose consumption rate does not exceed the rate of replenishment.20,21 Considering the disadvantages of prevailing bioplastics, marine sources such as marine algae, marine animal waste, and marine-derived microorganisms, represent a promising alternative due to their rapid growth rates and easy cultivation, in addition to not interfering or competing with food resources.22 This review includes an overview of marine sources, extraction processes, and marine-derived bioplastics and their properties. Finally, discuss the limitations of marine-derived bioplastics and future perspectives to reduce plastic-induced pollution and its environmental impacts.

Marine sources

Oceans cover more than 70% of the surface of the Earth and serve as habitats for marine organisms. The incredible diversity of marine organisms compared to freshwater and terrestrial species has recently fueled many innovative applications. Marine sources have great potential to serve as feedstock to produce biofuels, biomaterials, and bioactive compounds. Harnessing marine sources for the development of these technologies could greatly decrease the use of crop feedstock that could otherwise be used as food and mitigate the carbon footprint of fossil fuels. Marine-derived algae, marine animal waste, and microorganisms are the marine sources discussed in this paper and their chemical structures are illustrated in Figure 2.

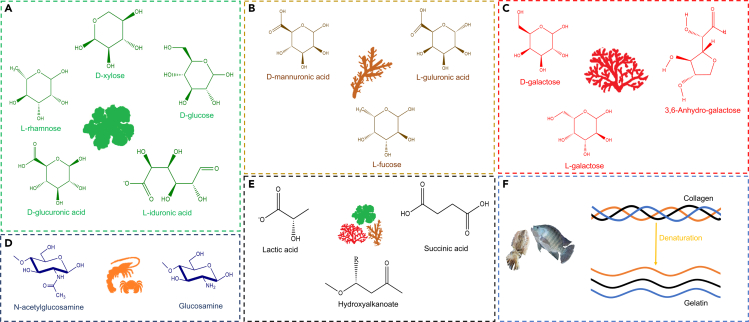

Figure 2.

Chemical and physical structures of marine-derived monomers and polymers

Chemical structures of Monomer units of (A) Green, (B) Brown, and (C) Red macro-algae, (D) Chitin and Chitosan (E) PLA, PBS, and PHA. (F) Structure of Collagen and Gelatin.

Marine algae

Marine algae are a major component of the marine ecosystem and comprise macroalgae (seaweed) and microalgae, which share common traits and photosynthetic ability, but are different in size and morphology. Marine algae grow in a wide range of marine environments throughout the year and can achieve high growth without depending on arable lands, chemicals, or fertilizers.23 Seaweeds are categorized as green macroalgae (Chlorophyta), red macroalgae (Rhodophyta), and brown macroalgae (Phaeophyta) depending on their pigments’ composition. Seaweed cultivation is a relatively simple process that can remove excess nutrients from the surrounding environment, which helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater consumption, and potential deforestation. Red algae are small compared to brown algae, but they are a rich source of complex sulfated galactan, carrageenan, agar, and agarose. The starch granules of red algae share structural similarities with those of vascular plants but without amylose.24,25 Microalgae are unicellular organisms whose sizes range from approximately 5 μm (e.g., Chlorella sp.) to more than 100 μm (e.g., Spirulina sp.) and can grow rapidly even in polluted environments. Microalgae naturally accumulate carbohydrates in the form of starch granules, which is the major component of marine microalgae biomass and shows similar characteristics to those of starch sources derived from terrestrial plants.26,27 Marine algae are rich in polysaccharides such as ulvan, cellulose, alginate, carrageenan, agar, and fucoidan. Marine algae-derived bioplastic production mainly depends on polysaccharides (Table 2) extracted from marine algae. The polysaccharide content in Chlorophyta ranges from 4 to 68% (Sargassum, Ulva), in Rhodophyta 63-76% (Gracilaria, Porphyra), and in Phaeophyta, it ranges from 66 to 70% (Fucus, Ascophyllum).28 The polysaccharide content of algae may change depending on the species dependent or seasonal variations which can in turn affect the per-unit price of the final product. However, seaweed waste can also be utilized for bioplastic production, thus minimizing the use of raw seaweed required for other products and reducing waste accumulation.29,30 Due to the increase in the demand for natural products, as well as the recent technological breakthroughs that make their production and commercialization feasible, the global market for algae products is projected to reach $4,286.8 million by 2031, assuming a compound annual growth rate of 4.88% from 2022 to 2031.31 Marine algal polysaccharide extraction processes are depicted in Figure 3.32 The large-scale development of marine-derived bioplastics is still being researched, and significant advancements are expected in the bioplastic industry. However, reaching the desired production levels to meet demand will take some time. A schematic of marine-derived-bioplastic production processes is represented in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Marine-derived sources for bioplastic production

| Marine Source | Biopolymer | Monomer unit | Method of extraction | Yield (dry weight basis) | Properties/Findings | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algae-derived |

Green Algae: Ulva lactuca, Ulva fasciata |

Ulvan | L-rhamnose, D-xylose, D-glucose, D-glucuronic acid, iduronic acid | Acid extraction (AE), enzymatic extraction (EE) | From EE a 17.95% (Ulva lactuca) 28.86% (Ulva fasciata) |

Glass transition temperature (Tg) AE at 80 °C - pH 2: 76.74°C, AE at 90 °C - pH 1.5: 56.75 EE 58.99 |

Guidara et al., 2019, Ramu Ganesan et al., 2018, Guidara et al., 202033,34,35 |

|

Green Algae: Ulva fasciata Brown Algae: Sargassum fluitans, Laminaria japonica Sargassum natans |

Cellulose | Glucose | AE | 14.7% | Mass loss starts around 100-120 °C | Lakshmi et al., 2017, Doh and Whiteside, 2020, Doh et al., 202036,37,38 | |

|

Brown Algae: Macrocystis pyrifera, Sargassum fulvellum Laminaria japonica Sargassum natans Sargassum turbinarioides |

Alginate | D-mannuronic acid and L-guluronic acid | AE | 16.9% | Unique colloidal properties Yield increases with the temperature. | Torres et al., 200739 | |

|

Red Algae: Kappaphycus alvarezii, Furcellaria lumbricalis, Acanthophora spicifera |

Carrageenan | D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-galactose copolymer | Water extraction and solvent precipitation. | 20.26% (A. spicifera) 31.55% (semi-refined carrageenan) |

All carrageenan types are soluble in hot (80 °C) water. | Ramu Ganesan et al., 2018, Sudhakar et al., 2021, Abdul Khalil et al., 2018, Zaimis, 2021, Ganesan et al., 201834,40,41,42,43 | |

|

Red Algae: Gelidium sesquipedale, Gelidium corneum, Gracilaria vermiculophylla Gracilaria corticate, Melanothamnus afaqhussainii |

Agar | D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-L-galactopyranose (agarose) D-galactose and L-galactose (agaropectin) |

Hot water extraction (HWE) | 11.9% | Antioxidant capacity in unpurified agar | Martínez-Sanz et al, 201944 | |

|

Brown Algae: Padina tetrastromatica |

Fucoidan | Fucose, galactose, uronic acid, xylose | HWE, AE | – | Antioxidant, anticoagulant, and anti-inflammatory properties. | Govindaswamy et al., 201845 | |

| Animal-derived | Fish skin collagen Starry triggerfish A. stellatus, Unicorn leatherjacket Aluterus Monocero, Mustelus |

Collagen | Collagen molecules | Chemical or enzymatic hydrolysis | Acid solubilized collagen 7.1% and pepsin solubilized collagen 12.6% wet weight basis | Nontoxicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability | Sommer and Kunz, 2012, Wang, et al., 2017, Ahmad et al., 2016, Ben Slimane and Sadok, 2018, Ahmad et al., 201646,47,48,49,50 |

| Crab (Chionoecetes opilio) Lobster (Nephro, Homarus) Shrimp (Crangon crangon) Mollusks |

Chitin | N-Acetyl-Aminoglucose | Chemical and biological extraction | – | Biocompatibility Nontoxicity Antioxidant activity Nontoxicity |

Priyadarshi and Rhim, 202051 | |

| Chitosan | Glucosamine (deacetylated monomer) and N-acetyl-glucosamine (acetylated monomer) | Acetylation of chitin | - |

||||

| Microorganism derived |

Red Macroalgae: Gracilaria sp. Brown Macroalgae: Sargassum siliquosum Green Macroalgae: Ulva lactuca Green Microalgae: Nannochloropsis salina Chlorella vulgaris |

PLA | LA | Acid extraction, cellulase hydrolysis | – | Biodegradability | Lin et al., 2020, Nagarajan et al., 2022, Nagarajan et al., 2020, Hirayama and Ueda, 2004, Talukder et al., 2012, Chen et al., 202052,53,54,55,56,57 |

|

Red Algae: Eucheuma denticulatum |

Poly (L-Lactic Acid) (PLLA) | L-Lactic Acid | Acid thermal hydrolysis | – | Biocompatibility Biodegradability |

Tong et al., 202158 | |

|

Green Microalgae: Chlorella vulgaris Micractinium sp. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

PBS | SA | Acid thermal hydrolysis | – | Biodegradability | Sorokina, 2020, Chiang et al., 2021, Knoshaug et al., 2018, Lee et al., 201459,60,61,62 | |

|

Algae: Ulva sp. Gelidium amansii Sargassum sp. Marine Microorganism: Alcaligenes eutrophus Halomonas campisalis Methylobacterium rhodesianum Phaeodactylum tricornutum Pseudomonas oleovorans Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pseudodonghicola xiamenensis Sphaerotilus natans Streptomyces coelicolor Streptomyces halstedii Streptomyces anulatus Vibrio azureus |

PHA | Hydroxyalkanoate | Acid treatment of algae. Flask, batch, fed-batch processing |

– | Biocompatibility Biodegradability |

Verma et al., 2002, Sasidharan et al., 2015, Ray and Kalia, 2017, O’Connor et al., 2013, Chmelová et al., 202163,64,65,66,67 | |

| Solvent extraction | - |

Park et al., 2020, Arun et al., 2009, Ojha and Das, 2020, Tan et al., 2011, Don et al., 2006, Shrivastav et al., 2010, Dubey and Mishra, 2022, Gnaim et al., 2021, R., R. et al., 2017, Han et al., 2014, Ghosh, 201968,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78 | |||||

Figure 3.

Flowchart of biopolymer extraction processes

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of Marine derived-bioplastic production processes

Marine algae-derived bioplastic

Ulvan

Sulfated polysaccharide ulvan, extracted from cell walls of green seaweeds is commonly available in Ulva species, and it consists of rhamnose, xylose, glucuronic acid, and iduronic acid monomers. A study was carried out using Ulva compressa, Ulva ohnoi, Cladophora pellucida, Nemalion helminthoides, Galaxaura rugosa, Gracilaria sp., Padina pavonica, and Sargassum vulgare which are commonly found in the Eastern Mediterranean shores. It has shown that Ulva sp. has an economic potential between $1,733 kg− 1 and $3,140 kg− 1 of Ulva biomass.79 Ulvan is an anionic polymer known for its high glass transition temperatures. Ulvan yields vary species-dependently and are also influenced by the method of extraction and purification.33 In most studies, washing, drying, and milling processes are used to convert seaweed into powder, which is typically followed by water and solvent precipitation methods to extract the polysaccharides, after which filtration methods are used to purify the sulfated polysaccharides. In one study using Ulva lactuca, a 26% ulvan yield in dry matter, was achieved through enzymatic chemical extraction compared to acid extraction at 80 °C at pH 2.33 In another study, a 28.86% higher ulvan polysaccharide yield was obtained from green seaweed Ulva fasciata via the water and solvent precipitation extraction process.(Table 2)34 Moreover, although extraction conditions do not affect the overall chemical structure of ulvans, they do affect their transition temperature and surface charge.80 Depending on the pH conditions (pH 1.5 to 2), alcohol precipitate yields have varied from 21.68% to 32.7%. Therefore, pH was found to have the greatest impact on the alcohol precipitate production and monosaccharide composition of ulvan extracts.81 Ulvan films are typically prepared by dissolving dried extracts in distilled water and then adding plasticizers such as glycerol or sorbitol.33 The unique gelling mechanisms of ulvan polysaccharides make them suitable for film production, where the concentration and type of plasticizer are the main factors affecting the properties of the final ulvan-derived product. It has been observed that an increase in plasticizer content has raised the thickness of films to a maximum of 40%, regardless of the plasticizer glycerol or sorbitol.35 The optical, thermal, structural, and antioxidant properties of ulvan films are dependent on the extraction conditions and procedures. But ulvans are potential in giving film formulations regardless of extraction procedure.33 Edible film developed using a combination of Kappaphycus alvarezii and U. fasciata has indicated a tensile strength of 49.12 MPa, an elongation of 11.02%, and a thickness of 0.118 mm. Films prepared only using ulvan polysaccharide (70%) and glycerol can inhibit hydroxyl radicals within the range of 3.05-68.26%.34 Generally, the thickness of bioplastic depends on the chemical structure and fabrication method. The study demonstrated that the complex structures and functional properties of films are dependent on the extraction procedure, as well as the selection of suitable plasticizer type, and concentration.35

Cellulose

The extracellular matrix of several marine green algae, red algae species, and some phyla of brown algae has been reported to contain cellulose and hemicellulose. Marine-derived cellulose is abundant and has better diversity and functional properties compared to terrestrial biomass-derived cellulose.82 Using a solvent evaporation technique, 14.7% cellulose content on a dry weight basis was extracted from the green seaweed U. fasciata, after which the extract was used to synthesize carboxymethyl cellulose and prepare thin films.36 Moreover, another study has reported, the extraction of less purified cellulose fractions from the brown seaweed species Alaria esculenta, Saccharina latissimi, and Ascophyllum nodosum via simple alkaline extraction to produce food packaging films. The obtained films exhibited high cellulose purity and excellent mechanical properties.83

Agar

Agar is a polysaccharide extracted from membranal components of red algae, consisting of disaccharide-repeating units of 3-linked β-D-galactose and 4-linked 3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactose (3,6-AG) residues. It consists of two fractions: agarose and agaropectin, where the gelling fraction of agarose, is responsible for gelling properties, whereas the non-gelling fraction of agaropectin is responsible for thickening properties. Its chemical structure is directly responsible for the physical properties such as gel strength and melting temperature. Low contents of anionic sulfates promote the formation of strong gels because high sulfate content inhibits the gel network formation.84 In a previous study, the hot water extraction method was used to extract agar from the red seaweed Gracilaria corticata, with a high yield of 18.5%. Extracted agar was mixed with plasticizers such as glycerol and sorbitol to prepare eco-friendly bioplastics using the film-casting method. Glycerol contributes to maximizing the elasticity of films, whereas sorbitol enhances their tensile strength. Bioplastic samples prepared using the lowest agar concentration blended with glycerol exhibited the highest solubility and biodegradation rates. These results indicated that increasing the amount of agar in the mixture had a direct impact on film thickness and tensile strength.85 The low hygroscopic nature of agar is advantageous in the bioplastic production process. Unpurified agar-based extracts are used for sustainable and cost-effective film production because the process does not require any additional plasticizers for film production, as the impurities of agar exert a plasticization effect. Heat and sonication techniques are often incorporated into the extraction process to decrease the extraction time without affecting the extraction yield and its properties.86 Marine microorganisms such as Vibrio sp. and Pseudomonas atlantica are responsible for the degradation of agar. Specifically, these bacteria produce enzymes that can cleave the molecular structure of agar into agarotetraose or neoagarotetraose, which can be further broken down into agarobiose and finally galactose.87

Carrageenan

Carrageenan is a water-soluble linear polysaccharide, found in the cell walls of red algae based on the repetition of the disaccharide sequence of β-D-galactose bonded at position 3, and α-D-galactose bonded at position 4. Isomers of carrageenan, κ- (kappa), λ- (lambda), and ι- (iota) differ depending on the number and position of sulfate ester groups on galactose, and the degree of sulfation. Carrageenan has a greater potential to be used as a gel-forming material due to its versatility. For example, λ-carrageenan creates viscous solutions that do not form gels, whereas κ-carrageenan forms hard, strong, and brittle gels, and ι-carrageenan forms soft, elastic, and weak gels.84 Marium et al.88 used the hot water extraction method to release carrageenan from dried red seaweed (Solieria robusta) and the film casting method was used to prepare malleable and smooth textured films. The thickness, tensile strength, and elongation properties of films were enhanced with the increasing biopolymer content, and the addition of sorbitol rendered the films more resistant to deformation, solubility, and biodegradation compared to glycerol blends. Inexpensive semi-refined κ-carrageenan can be used as an alternative to costly refined carrageenan to prepare edible films. The addition of plasticizers significantly improves the tensile strength and elongation at the break of carrageenan-derived films.89

Alginate

Alginate is a polysaccharide found in the cell walls of brown algae, which is a linear copolymer of (1-4)-linked β-D mannuronic acid (M) and α-L-guluronic acid (G) residues. Alginates with a higher number of G blocks have stronger gelling properties and alginates with a higher number of M blocks are viscous.90 Alginate films are prepared using plasticizers such as glycerol, and crosslinking with calcium chloride.91 The addition of reinforcing agents into alginate films has greatly contributed to overcoming the poor mechanical and barrier properties of unmodified alginate films.37 Alginate degradation occurs naturally through the activity of alginate hydrolases and lyases produced by marine bacteria such as Cobetia sp. These enzymes act on the glycosidic linkage of alginate and form saturated and unsaturated uronic acid.92

Starch

Similar to terrestrial plants, starch is a major storage carbohydrate in marine algae. However, the starch composition and amylose-to-amylopectin ratios of algae are largely species-, environment-, and season-dependent. The amylose-to-amylopectin ratio plays an important role in starch gelation, which occurs through gelatinization and retrogradation mediated by the heating and cooling cycle. The marine macroalgae U. ohnoi cultivated offshore for 13 months produced an average starch yield of 3.43 ton/hectare/year, proving its potential to be used as an alternative to agricultural crop-based starch, which requires arable lands and freshwater.93 The characteristics of starch obtained from marine microalgae Klebsormidium flaccidum are quite similar to those of commercial corn starch. The amylose and amylopectin content of microalgae was found to be 25.52% and 74.48% respectively, which was similar compared to the 23.04% and 76.96% contents in corn starch. Marine microalgae-derived starch is considered a better alternative for the production of various sustainable bioplastic products due to its superior mechanical and biological properties compared to terrestrial plant sources.94

Polylactic acid

Lactic acid (LA) has become a key commodity chemical due to the high demand for biodegradable polymers such as PLA as an alternative to petroleum-based plastics. LA is produced by either chemical synthesis or microbial fermentation. Many studies have demonstrated that microbial fermentation is a more efficient alternative to chemical LA synthesis because the latter involves high manufacturing costs and is unsuitable for large-scale production.95 Inexpensive and economic carbon sources play a major role in reducing the production cost of fermentation processes. Marine algae (Table 3) can be used as an attractive potential carbon source not only because they are rich in carbohydrates, have a short life cycle, and contain less lignin than terrestrial plants, which enables easy saccharification without the need for complex pretreatment processes. Hwang et al.96 demonstrated that the green seaweed Enteromorpha prolifera could be effectively used for LA production. The highest LA yield was produced when hydrolysates of the E. prolifera were fermented by Lactobacillus salivarius.96 Moreover, 37.7 g/L of high optical purity L-lactate was obtained by fermenting hydrolysates of the brown seaweed Laminaria japonica with Escherichia coli. These findings demonstrate the promising potential of brown seaweed as a feedstock for LA production.97 Likewise, 97.9% higher optical purity L-lactic acid was produced using L. japonica hydrolysate when fermented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus.98 There are three main methods through which high molecular weight bio-PLA can be produced from LA: direct condensation polymerization, direct polycondensation in an azeotropic solution, and polymerization through lactide formation. The obtained high molecular weight PLA resin can be converted into end products using the melt processing technique, where the material is heated above its melting temperature, shaped, and finally cooled.99 Biobased LA production processes may thus be useful in the production of algae-derived PLA. Thus, marine algae can be used as a promising alternative to produce PLA bioplastic using cost-effective processing methods.

Table 3.

LA, SA, and PHA production using marine-derived sources

| Carbon source | Bacterial Strain | Yield | Final product | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gracilaria sp | L. acidophilus and L. plantarum | Lactic Acid (LA) concentration of 19.32 g/L | LA | Lin et al., 202052 |

| L. plantarum | LA yield 0.94 g/g | LA | Nagarajan et al., 202253 | |

| Eucheuma denticulatum | Bacillus coagulans | L-LA yield of 89.4% (compared to initial galactose g/L) | LLA | Tong et al., 202158 |

| Sargassum siliquosum | L. acidophilus and L. plantarum | – | LA | Lin et al., 202052 |

| Sargassum cristaefolium | L. plantarum | LA yield 0.81 g/g | LA | Nagarajan et al., 202253 |

| Ulva lactuca | L. acidophilus and L. plantarum | – | LA | Lin et al., 202052 |

| Ulva sp. | L. plantarum | LA yield of 0.91 g/g and 0.85 g/g | LA | Nagarajan et al., 2022, Nagarajan et al., 202053,54 |

| Nannochloropsis salina | L. pentosus | LA yield 92.8% (lactic acid production compared to sugar consumption) | LA | Talukder et al., 201256 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | L. plantarum | LA yield of 0.91 g/g sugars and LA productivity 9.93 g/L/h | LA | Nagarajan et al., 2020, Chen et al., 202054,57 |

| Scenedesmus acutus | Actinobacillus succinogenes | Succinic acid (SA) yield of 60% (mass of SA eluted compared to the dry weight of SA) | SA | Knoshaug et al., 201861 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Actinobacillus succinogenes | SA yield of 0.72 g/g | SA | Chiang et al., 202160 |

| Micractinium sp. | Actinobacillus succinogenes | SA yield of 0.67 g/g | SA | Sorokina, 202059 |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Succinate 0.28g (succinate/g of total sugars including starch) | SA | Lee et al., 201462 |

| Gelidium amansii | Bacillus megaterium | 51–54% of DCW | PHA | Alkotaini et al., 2016100 |

| Ulva sp. | Haloferax mediterranei | 77.8% of DCW | PHA | Steinbruch et al., 2020101 |

| - | Halomonas campisalis | 36.82% on DCW | PHA | Kulkarni et al., 2011102 |

| Sucrose | Halomonas pacifica and Halomonas salifodiane | Content of 6.9g and 7.1g of DCW | PHA | El-malek et al., 2020103 |

| Sargassum sp. | Cupriavidus necator | 74.4% of DCW | PHB | Azizi et al., 2017104 |

| Glucose | Vibrio azureus | 0.48 g/L production | PHB | Sasidharan et al., 201564 |

| Date syrup | Pseudodonghicola xiamenensis | 38.85% of date syrup DCW | PHB | Mostafa et al., 2020105 |

| Fructose syrup | Halomonas sp. YLGW01 | 95.26% of DCW | PHB | Park et al., 202068 |

Polybutylene succinate

PBS is among the most important biodegradable polyesters. This is synthesized via the polycondensation between succinic acid (SA) and butanediol. SA is widely used as a surfactant in medical, food, and chemical applications. However, although the biobased production of SA via fermentation processes has recently attracted increasing attention, this approach is costly compared to petroleum-based processes. To achieve sustainable and cost-effective SA production, costly carbon and nitrogen sources need to be replaced with inexpensive, feasible sources. Previous studies have demonstrated that marine algae (Table 3) can be used as inexpensive carbon sources in the production of SA. Olajuyin et al.106 were the first to explore the applicability of hydrolysates from red algae Palmaria palmata red macroalgae as a novel cost-effective alternative feedstock for SA production using E. coli. A higher concentration of 22.4 g/L was obtained after 72 h of dual-phase fermentation.106 In a similar process, SA was produced from L. japonica fermented by E. coli, which yielded a final SA concentration of 17.44 g/L after a 24-h dual-phase fermentation process.107 Moreover, hydrolysates of microalgae Micractinium sp. were fermented by Actinobacillus succinogenes to produce SA.59 Most of the studies have shown that higher yields and concentrations of SA can be produced when marine algae are used. A previous study reported the production of 1,4-butanediol using SA through a hydrogenation process. The produced 1,4-butanediol and SA then underwent esterification followed by polycondensation to produce bio-based PBS.108 Collectively, these findings demonstrated that bio-based production processes may be advantageous for marine algae-derived PBS production in the future.

Polyhydroxyalkanoate

PHAs are environmentally friendly and biodegradable plastics that accumulate inside a diverse range of microbial cells as an intracellular storage material.109 Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) is a short-chain PHA that belongs to the PHA family and is naturally produced by several microorganisms. However, the use of PHA in many commercial applications has declined because its production requires expensive carbon sources and fermentation processes.110 Several studies have suggested that seaweed-containing medium is a promising substrate for PHA production at a low cost (Table 3). Researchers have used hydrolysates of the green macroalgae Ulva sp. to produce PHA. When the hydrolysate was fermented by Haloferax mediterranei, a maximum volumetric PHA productivity with a maximum PHA content was produced from an initial cell culture density of 50 gL−1.111 In another study, the inexpensive, and abundant red algae Gelidium amansii, was processed using a simple acid pretreatment approach without enzymatic hydrolysis and inhibitor removal, after which it was used to produce PHA by batch and fed-batch cultivation of Bacillus megaterium.100 In a similar study, PHA was produced by the marine bacterium Saccharophagus degradans, using G. amansii as the carbon source.112 Furthermore, different strains of Cobetia sp. isolated from seaweeds and cultured in a nitrogen-limiting mineral salt medium containing alginate as the sole carbon source were found to be able to accumulate PHB. When these bacteria were cultured for two days in a nitrogen-limiting mineral salt medium at pH 5.0 containing 6% NaCl and 3% (W/V), alginate was found to be the optimum culture condition for PHB production.113 Bera et al.114 explored whether large-scale microbial synthesis of PHA could be achieved using seaweed-derived crude levulinic acid as a co-nutrient. These studies demonstrate that polysaccharide-rich algae can be utilized without harsh pretreatments and procedures for large-scale inexpensive bioplastic production in the future. Certain by-products produced in biomass pretreatment processes such as furfural, acetate, vanillin, and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde act as inhibitors of microbial fermentation and affect microbial growth and PHB yields. Effective pretreatment methods must thus be carefully selected to increase production yields. Nevertheless, performing these optimization tests increases production costs, which constitutes a noteworthy disadvantage.21

Marine animal waste

More than 50% of fish tissues such as fins, skin, scales, viscera, the shells of shrimp and crabs, and by-catch products end up wasted without any advantage.115 These waste materials can be used to their full potential by extracting collagen, gelatin, chitin, or chitosan for the production of value-added bioplastics.116

Marine animal waste-derived bioplastic

Marine animal waste-derived products are widely available in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and agricultural industries. There is a growing interest in utilizing marine animal waste products in the seafood industry, as novel materials for bioplastic production.

Chitin and chitosan

Chitin is the main structural polysaccharide in shells of crustaceans such as crabs, shrimp, mollusks, and lobsters, made of N-Acetyl-Amino glucose. Chitosan is the deacetylated form of chitin, which consists of glucosamine the deacetylated monomer, and N-acetyl-glucosamine the acetylated monomer. Chitin and its derivatives have become promising polymers due to their abundance and low cost. Moreover, these compounds have been found to possess antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, in addition to being biocompatible and biodegradable. Chitin is typically extracted through chemical or biological methods, and the properties of chitosan are often enhanced using plasticizers, cross-linkers, or the incorporation of other polymers. Chitin is considered a suitable polymer to produce non-absorbable surgical sutures to overcome the drawbacks of synthetic sutures, such as inflammatory and tissue reactions. However, chitin-derived sutures are often crosslinked or reinforced with nanofillers such as graphene oxide to improve their mechanical properties.117 In another study, researchers successfully fabricated chitin-based bioplastics by drying chitin hydrogels under negative pressure, after which hydroxyapatite (HAP) was incorporated. The prepared chitin bioplastics without HAP were transparent, flexible, tough, and had a thickness of 0.30 mm, a tensile strength of 51.5 MPa, and an elongation at break of 34.1%. HAP incorporation into the chitin bioplastic improved the absorption of proteins, cell adhesion, and tensile strength up to 99.2 MPa, which satisfies the tensile strength required for cortical bone and trabecular bone regeneration. The multilayered structure of chitin bioplastic provides superior mechanical strength and flexibility, selective permeability, and bioactivity for bone tissue repair.118 Fernandez and Ingber119 used marine chitosan produced with different processing techniques and analyzed its properties. Additionally, the authors explored different manufacturing strategies such as casting and injection molding for the development of large-scale three-dimensional objects that could be rapidly and efficiently recycled.119 Chitosan-derived edible and biodegradable films have been reported to possess antimicrobial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, the incorporation of nanosized chitosan affects their mechanical strength and stiffness.120 These studies have demonstrated that chitin and chitosan can be used to produce valuable bioplastics. Chitin biodegradation occurs in marine environments in either the chitinolytic pathway or the chitosan pathway. In the chitinolytic pathway, chitin is hydrolyzed by chitinase resulting in oligosaccharides, after which exochitinase transforms chitin into chitobiose. These disaccharides are then converted into N acetyl-glucosamine and finally to glucosamine. In the chitosan pathway, chitin is deacetylated to chitosan and hydrolyzed to oligomers of glucosamine via the activity of glucosaminidase. Chitinase and chitobiose are produced by marine microorganisms such as Listonella anguillarum and Vibrio mimicus.121

Collagen

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body, accounting for approximately 30% of total body protein mass. Moreover, collagen is also the most important structural protein, constituting the extracellular matrix of connective tissues. Marine sources such as fish biomass and by-catch organisms, such as jellyfish, sharks, starfish, and sponges, have become promising sources of collagen due to their high collagen content. Additionally, unlike bovine, porcine, and other animal collagen types, marine-derived collagen does not transmit diseases.122 The marine collagen isolation process includes preparation, extraction, and recovery steps. The preparation step includes washing, cleaning, cutting, and pretreatment before extraction to remove non-collagenous materials and increase extraction efficiency. Collagen extraction is conducted mainly through acid extraction or by pepsin-aided extraction because collagen is insoluble in water due to its triple helical structure with inter and intra-molecular hydrogen bond crosslinks.123 Song et al.124 extracted a novel form of acid-soluble collagen from Stomolophus nomurai meleagris edible jellyfish. The extracted collagen was freeze-dried and crosslinked to prepare porous scaffolds. The resulting scaffolds exhibited high porosity and an interconnected pore structure, which was well suited for high-density cell seeding and efficient nutrient supply to cells. Therefore, this material can be used in tissue engineering (TE) applications.124 In a similar process, Ramanathan et al.125 extracted collagen from starry puffer fish (Arothron stellatus) to fabricate a bilayer matrix of cellulose acetate nanofibers over a collagen 3D matrix. The 3D matrix exhibited better porosity and swelling behavior, and its 3D architecture provided good cell adhesion and proliferation.125 Despite its many advantages, the main drawback of collagen is its low mechanical strength. Therefore, collagen is blended with other biopolymers to overcome these limitations. In a study, chitosan/collagen 3D porous scaffolds were fabricated through a freeze-drying technique using different compositions of chitosan, collagen extracted from tilapia fish scales, and glycerin. The scaffolds prepared with higher amounts of fish collagen and glycerin exhibited high porosity, appropriate mechanical strength, and excellent cytocompatibility.126 In another study, chitosan was incorporated into a collagen scaffold to improve its mechanical and biological properties of the scaffold. Chitosan addition increased the compressive strength and swelling ratio of the collagen scaffold, in addition to prolonging its degradation ratio. However, the bovine-derived collagen scaffold still performed better than its marine fish-derived counterpart.127 Feng et al.128 prepared a hydrogel using fish scale-derived collagen extracted from the scales of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) and sodium alginate for full-thickness wound healing. The prepared hydrogel successfully accelerated re-epithelialization, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis. These inexpensive and easy-to-process structures can be converted into valuable bioplastics for future applications. Marine microorganisms such as Pseudomonas sp. produce collagenases that can digest the collagen in the triple helix region and break down collagen molecules into collagen fragments.129

Marine microorganism

Compared to plants and animals, microorganisms participate in a much wider variety of ecological functions. However, until recently, microbes were generally not recognized for polymer production due to their low conversion rates of raw materials into polymers, and high energy requirements.20 Marine microorganisms can withstand high salt concentrations, which prevents the growth of other non-halophilic microorganisms.130,131 Moderate halophiles can grow at salt concentrations of 3%-15% (W/V) but can tolerate concentrations between 0% and 25% (W/V).132 Microorganisms adapted to survive in extreme environmental conditions are considered important polymer sources because their properties do not change during extreme production processes. These factors prevent the need for strict sterile conditions during the PHA production process.130,131 The unexploited vast marine environment provides a wide variety of resources and opportunities to isolate new microorganisms, that can be utilized for industrial-scale production with minimal environmental consequences.

Marine microorganism-derived bioplastic

Typically, commercial PHA production is based on pure culture-based fermentation under sterile conditions. PHA has become a promising bioplastic due to its many desirable properties including its biodegradability, biocompatibility, and outstanding mechanical properties. However, compared to synthetic plastics, the demand for PHA has declined due to its sensitivity to thermal degradation, the higher cost of carbon sources, and the need for complex processing steps such as fermentation, sterilization, and isolation.51,46 To overcome these limitations, researchers have focused on utilizing low-cost renewable carbon sources and new bacterial strains (Table 3), in addition to optimizing fermentation conditions to reduce production costs, and improve performance.133 Exploratory studies in marine environments are currently being conducted to isolate new marine microorganisms capable of producing low-cost PHA under open, unsterile conditions at low temperatures. Marine microorganisms pose a low risk of microbial contamination due to their capacity to withstand high salt concentrations and as well as their adaptability to low temperatures.68,134 Studies have demonstrated that microorganisms such as Alcaligenes latus, Bacillus licheniformis,135 Vibrio sp.,69 Ralstonia eutropha136,105, Shewanella marisflavi,137 and Pseudomonas putida found in marine habitats, and Pichia kudriavzevii yeast isolated from marine seaweed70 are potential PHA producers that can accumulate high PHA contents under minimum nutrient requirements.71,72 Halophiles are a type of microorganism that can grow and survive in extreme conditions, thus preventing other microbial growth without requiring strict sterile conditions. Therefore, halophilic bacteria such as Halomonas hydrothermalis,73,74 and Halomonas venusta138 are potential low-cost PHA-producing microorganisms, that can be grown using open, unsterile, and continuous fermentation processes, thus reducing the high cost associated with sterile and batch or fed-batch fermentation processes.130 A previous study used the Halomonas TD01 bacterium strain to produce PHB in a simple, open, unsterile, and continuous fermentation process. After 14 days of fermentation, cells grew to an average of 40 g/L dry cell weight (DCW) containing 60% PHB in a fermenter containing glucose salt medium. This open, unsterile, and continuous process contributed significantly to reduce the cost of PHB production.71 Stanley et al.138 studied the PHA production capacity of H. venusta, a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from marine habitats. In a shake flask test, a maximum PHA content of 70.56% was obtained when glucose and ammonium citrate were used as carbon and nitrogen sources. In the high-concentration single-pulse method, a maximum PHA content of 33.4 g/L was obtained, which corresponded to 88.12% of DCW. In contrast, a PHA content of only 26 g/L was achieved using the pH-based feeding method, which corresponded to 39.15% of DCW. The efficient single-pulse method can thus be used instead of pH-based feeding for future PHA production improvements.138 Dubey et al.74 optimized the culture conditions of the wild marine bacterium H. hydrothermalis by manipulating seawater rather than freshwater to enhance PHA production and reduce production costs. The authors reported that the maximum PHA productivity was achieved by utilizing 3% glycerol, 3% dry seawater mix, and 0.55% peptone, which reduces the cost of carbon sources to produce low-cost PHA.74 In another study, an integrated process was designed for low-cost simultaneous production of ε-polylysine polymer and PHA in the same fermentation broth. For polymer production, Jatropha biodiesel waste residue was used as the carbon source and was fermented by the marine bacterial strain Bacillus licheniformis PL26. These processes not only reduce production costs but also utilize waste residues, thereby reducing waste disposal.135 Several marine bacteria were recently reported to produce PHA at low cost, including Cobetia, Sulfitobacter, and Pseudoalteromonas bacterial strains isolated from the seaweed Ulva sp. in the presence of various sugars and acid hydrolysates as carbon sources,75 as well as Bacillus cereus and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes bacterial strains isolated from the seaweeds in the presence of industrial waste as substrate.76 Intracellular PHA contents of 30.3% and 27.2% (w/w) were respectively obtained using starch-containing Massilia strain UMI-21 isolated from green algae Ulva sp. and cultivated under nitrogen-limiting conditions with corn starch or soluble starch as the carbon sources.77 Bacillus sp. YHY22 strain was reported to produce PHB yields of 4.05 g/L with 6.25 g/L DCW in a non-sterilized culture medium of 8% NaCl and 2% lactate, which is a byproduct of bacterial fermentation from sugar.139 These facts demonstrate the ability of marine-derived microorganisms to produce PHA, thus providing an inexpensive and environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic and bio-based plastic sources.

Some startup companies such as MarPlast have sought to identify at developing marine microorganisms that can be cultivated using different carbon sources at the commercial level for the efficient, abundant, and sustainable production of PHAs.140

Applications of marine-derived bioplastic

Marine-derived bioplastics have recently garnered increasing attention in a variety of fields including the food, agricultural, industrial, and biomedical industries, as described in Table 4. The preferred applications depend on the properties of the final product, which may vary depending on the species, synthesis methods, and environmental conditions. Properties such as ductility, stiffness, solubility, water vapor permeability, transparency, and moisture content should be considered when using bioplastics for food coating applications. The excellent optical, mechanical, and barrier properties of marine ulvan, cellulose, alginate, fucoidan, carrageenan, agar, collagen, and chitosan-derived films make them promising materials for food and biomedical packaging applications, edible cups, sachets, and plastic bags. Moreover, marine algae-derived thermoplastic starch is used to produce drug capsules due to its ability to absorb humidity. Sole algae-derived products are often mixed with other cost-effective hydrophobic synthetic polymers such as polyethylene and polypropylene or plasticizers such as glycerol or sorbitol. Alternatively, they can also be blended with different algae species to improve their mechanical and water barrier properties and make them suitable for commercial applications.33,35,141,142 TE is an emerging multidisciplinary field focusing on creating alternative tissue substitutes to restore, maintain, and improve normal or impaired tissue function.126 Marine seaweed-derived scaffolds possess several properties that are essential for TE applications such as biocompatibility, thermo-sensitivity, and biodegradation in addition to promoting cell proliferation.143 Marine fish collagen scaffolds are mainly used in skin, bone, and cartilage TE due to their extracellular matrix-mimicking properties. Additionally, these scaffolds rarely induce inflammatory responses and are unlikely to transmit diseases. Moreover, they can be applied to patients with religious restrictions, and are a low-cost alternative to bovine and porcine collagen.124 Biocompatible chitin bioplastics can be potentially used for various TE applications including bone TE, due to their outstanding histocompatibility, hemocompatibility, and biodegradability.118 Moreover, the viscoelasticity, water retention ability, biocompatibility, and wound healing properties of hyaluronan scaffolds make them uniquely well suited for drug delivery, surgical, and ophthalmological applications.116,144 PHAs are used in a wide variety of applications in the packaging, agriculture, and biomedical industries such as sutures, stents, and wound dressings. However, marine-derived PHA is still being actively researched. Due to their unique properties, bioplastics derived from marine sources have a high potential to lead the bioplastic industry. Seaweed-based bioplastics are commercialized by several manufacturers such as Evoware, Marine Innovation, Notpla, B’Zeos, SWAY, C-Combinator, FlexSea, Oceanium, Loliware, SoluBlue, and Kelpi (Table 1). In addition, some companies such as Shrilk and Marinatex produce bioplastics using marine-animal waste at the commercial level. Evoware’s seaweed-based edible packaging, food wrappings, and sachets contain high levels of fiber, vitamins, and minerals and are biodegradable within 30 days.15 Biodegradable Shrilk bioplastic is made of chitosan extracted from shrimp shells and fibroin from silk protein and can be used for medical applications such as dissolvable sutures, and scaffolds because both materials are FDA-approved. Additionally, these materials can be used in a wide variety of manufacturing applications due to their tunable mechanical properties and low weight. The transparent and flexible Marinatex sheet material is made of proteins extracted from fish skin and scales bound by agar extracted from red algae and is stronger than low-density polyethylene at the same thickness. It is ideal for single-use applications because it can be naturally biodegraded in 4-6 weeks in a soil environment without requiring special methods of disposal.

Table 4.

Applications of biopolymers

| Marine Source | Biopolymer | Applications | Tensile strength (MPa) | Thickness (μm) | Properties/Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Algae (Chlorophyta) | ||||||

| Ulva armoricana | Ulvan | Scaffold for bone TE, as resorbable bone graft substitutes | – | – | Non-toxic | Dash et al., 2014145 |

| Better cell proliferation | ||||||

| Ulvan/chitosan scaffold for TE | – | – | Non-toxic | Dash et al., 2018146 | ||

| Promote cell adhesion and differentiation toward the osteogenic phenotype. | ||||||

| Dense extracellular matrix | ||||||

| Ulvan methacrylate hydrogels for TE and biomedical applications. | – | – | Stable under physiological conditions. | Morelli and Chiellini, 2010147 | ||

| Injectable (in situ) hydrogels for biomedical applications. | – | – | Thermo-sensitivity | Morelli et al., 2016148 | ||

| Solid to gel transition at 30–31°C | ||||||

| Ulva lactuca | 3D porous structures for biomedical applications | – | – | Highly porous and interconnected structure | Alves et al., 2013149 | |

| Non-toxic degradation | ||||||

| Better cell viability | ||||||

| High water uptake ability | ||||||

| Antioxidant packaging | 0.1–3.5 | 11–17 | Elongation 9%–39% | Guidara et al., 2019, Guidara et al., 202033,35 | ||

| Biomedical edible capsule | Thickness and solubility depend on the plasticizer content | |||||

| Packaging | High transparency | |||||

| High antioxidant activity | ||||||

| Ulva pertusa | Ulvan/chitosan hydrogel as a biocompatible ion exchanger | – | – | More stable than alginic acid/chitosan under both acidic and basic conditions | Kanno et al., 2012150 | |

| Ulva fasciata | Packaging | 36.78 | 88 | Elongation 7.98% | Ramu Ganesan et al., 201834 | |

| Ulva rigida and crab shells | Ulvan/chitosan | Nanofibrous membranes for biomedical applications | – | – | Promotes cell attachment | Toskas et al., 2012151 |

| Proliferation of osteoblasts | ||||||

| Maintain cell morphology and viability | ||||||

| Ulva sp. and Cladophora sp. | Cellulose |

TE applications | – | – | Non-toxic | Bar-Shai et al., 2021152 |

| Cladophora sp. scaffold promotes elongated cells spreading along its fiber’s axis and gradual linear cell growth. | ||||||

| Ulva sp. scaffold promotes rapid cell growth in all directions. | ||||||

|

Ulva fasciata |

Cosmetic | – |

– |

70% transparency | Lakshmi et al., 201736 |

|

| Food | Biodegradable | |||||

| Textile | ||||||

| Medical, pharmaceutical | ||||||

| Agricultural applications | ||||||

| Brown Algae (Phaeophyta) | ||||||

| Sargassum fluitans | Cellulose | Biomedical applications | 123–168 | 71–75 | Elongation 3.4–7.9% | Doh and Whiteside, 202037 |

| Food packaging | ||||||

| Laminaria japonica and Sargassum natans | Cellulose and alginate | Alginate film for Packaging | 3.96–19.54 | 39–58 | Mechanical and physical properties depend on the percentage addition of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) | Doh et al., 202038 |

| Macrocystis pyrifera | AlginateAlginate | Agriculture | 49–57 | 39–49 | Mechanical and physical properties depend on Ca2+- H+ cross-linking ratios, concentrations, and time. | Zhao et al., 2017153 |

| Laminaria hyperborean | Wound dressing | 24–26 | 9.3–18.7 | Flexible | Wang et al., 2002154 | |

| Thin | ||||||

| Transparent | ||||||

| Non-toxic | ||||||

| Brown algae | Bioink | – | – | Promotes cellular behavior and degradation. | Yao et al., 2019155 | |

| Biocompatible | ||||||

| Low stiffness | ||||||

| High porosity | ||||||

| Addition of alginate lyase improves the degradation properties and effects on cellular behavior. | ||||||

| Brown algae | 3D cell-laden scaffolds potential for bone tissue repair and regeneration | – | – | Compressive moduli 1.5 kPa (0.8% alginate) - 14.2 kPa (2.3% alginate) | Zhang et al., 2019156 | |

| Lower the alginate concentration higher the viability and morphology, and higher the concentration higher the fidelity and mechanical properties. | ||||||

| Sargassum sp. | Carrageenan/alginate film for packaging | 2.83–43 | 37–84 | Tensile strength and solubility increase at high concentrations of alginate and low concentration of polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Giyatmi et al., 2020157 | |

| Thickness increases at high concentrations of alginate and PEG. | ||||||

| Sargassum fulvellum | Food packaging | 18.74–31.66 | 60–70 | Elongation ranges between 10.20 and 21.38% | Kim et al., 201891 | |

|

Padina tetrastromatica |

Fucoidan |

Gelatin/fucoidan (GF) films for food packaging |

55.37–63.37 |

62.50–66.25 |

Highest tensile strength at 3% fish gelatin with 30% sorbitol and 20% fucoidan concentration of protein (GF-20) | Govindaswamy et al., 201845 |

| Highest antioxidant activity in GF-20 | ||||||

| Red Algae (Rhodophyta) | ||||||

| Red microalgae | κ-carrageenan | Thermosensitive hydrogels as injectable bone fillers | – | – | Gelation temperature increases with the addition of potassium ions | Kim et al., 2011158 |

| Nanoengineered κ-carrageenan-nano silicate bio-inks for 3D printing and regenerative medicine. | – | – | Ability to print physiologically relevant scale tissue constructs without requiring secondary supports. | Wilson et al., 2017159 | ||

| Hydrogels for regenerative applications, fast cell/bioactive molecules delivery | – | – | Cytocompatibility | Popa et al., 2014160 | ||

| Biocompatibility | ||||||

| Low inflammatory responses | ||||||

| Red microalgae | κ-carrageenan | Injectable and sprayable hydrogels for in situ soft TE applications | – | – | Methacrylate carrageenan concentration and degree of methacrylation control the properties of the hydrogel. | Tavakoli et al., 2019161 |

| Biocompatible | ||||||

| Hydrogel for extrusion-type bioprinting | – | – | Shear-thinning behavior | Lim et al., 2020162 | ||

| Less viscosity compared to κ-carrageenan and stability against temperature. | ||||||

| Kappaphycus alvarezii | Carrageenan hydrogel as a scaffold for skin-derived multipotent stromal cells delivery | – | – | Multipotent stromal cells maintain its morphology, growth, and viability for at least one week in culture. | Rode, et al., 2018163 | |

| Improved extracellular matrix deposition | ||||||

| Acanthophora spicifera | λ-carrageenan | Carrageenan film for Antibacterial food packaging | 47.56 | 124 | Elongation 10.24% | Ganesan et al., 201843 |

| Kappaphycus alvarezii | Carrageenan | Carrageenan film for packaging, agriculture applications | 13.78 | 806 | Solubility 89–91% | Ramu Ganesan et al., 2018, Sudhakar et al., 2021, Abdul Khalil et al., 201834,40,41 |

| Furcellaria lumbricalis | Spoons, cups, packaging boxes | – | – | Soft and flexible | Zaimis et al., 202142 | |

| Improve properties by adding potato starch and glycerin | ||||||

| Gelidium sesquipedale | AgarAgar |

Agar film for food packaging | 2.4–68 | 68–82 | Tensile strength and elongation vary depending on the extraction method and plasticizer | Martínez-Sanz et al., 201986 |

| Gelidium corneum | Agar film for food packaging | 38.1 | 90 | Highest tensile strength when mixed with pure chitosan | Go and Song, 2020164 | |

| Gracilaria vermiculophylla | Agar film for food and antioxidant packaging | 41.39 | 37.59 | Tensile strength and thickness increase and solubility decrease with increased zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs). | Baek and Song, 2018165 | |

| Fish | ||||||

| Larimichthys crocea (fish scale) | Collagen | Collagen/sodium alginate hydrogels for full thickness wound healing | – | – | Promote full-thickness wound healing | Feng et al., 2020128 |

| Excellent ductility and flexibility | ||||||

| Marine Eel fish | Collagen/alginate scaffolds for TE applications using 3D printing | – | – | Enhance metabolic activity and cell proliferation | Govindharaj et a., 2019166 | |

| Excellent 3D printability and biocompatibility | ||||||

| Arothron stellatus fish | Nanofibrous spongy dressing material for wound-healing applications | – | – | High porosity, swelling, and stability | Ramanathan et al., 2020125 | |

| Good cell adhesion and proliferation | ||||||

| Prionace glauca blue shark skin | 3D printable cell-laden hydrogels | – | – | More collagens have better results in a short-term 3D culture. | Diogo et al., 2020167 | |

| Tilapia skin | Fish collagen scaffolds as a material for engineering cartilage | – | – | Superior cartilage repair effect. | Li et al., 2020168 | |

| Increase in the fish collagen concentration results in better biodegradability, biocompatibility, increase in water absorption capacity, and mechanical properties and a decrease in pore size and porosity. | ||||||

| Starry triggerfish (A. stellatus) | Biodegradable packaging film | 34,46 | 28 | Elongation 28% when acid solubilized | Ahmad et al., 201650 | |

| Elongation 40% when pepsin solubilized | ||||||

| Unicorn leatherjacket (Aluterus Monoceros) | Collagen |

Bioactive Film Composite | 20–40 | 21–57 | Ahmad et al., 201648 | |

| Mustelus | Food packaging applications | 55–70 | 15–17 | Good mechanical strength | Ben Slimane and Sadok, 201849 | |

| Suitable water solubility | ||||||

| UV barrier properties | ||||||

|

Paralichthys olivaceus (flat fish skin) |

Fish collagen/alginate/COS integrated scaffold for skin TE |

– |

– |

Porous architecture with 160-260 μm pore size and 90% porosity. | Chandika et al., 2015169 |

|

| Best cytocompatibility in scaffolds containing 1–3 kDa (Fish collagen alginate/chitooligosaccharides) | ||||||

| Shrimp | ||||||

| Shrimp waste | Chitosan | Chitosan–silver oxide nanocomposite film Food wrappings, surface coating | – | – | Biodegradable | Tripathi et al., 2011170 |

| Antibacterial properties | ||||||

| Biocompatible | ||||||

| Non-toxic | ||||||

| Shrimp shells | Bags | 18.73 | 28 | Similar tensile resistance compared to Egyptian plastic bags. | D’Angelo et al., 2018171 | |

Challenges of marine-derived biopolymers

Marine-derived polymers have numerous benefits but also some drawbacks. In some previous studies, they have demonstrated the seasonal variation in the nutritional composition of brown seaweed, Sargassum oligocystum, and green seaweed, Ulva prolifera. Physiological and environmental aspects during seasonal fluctuations significantly impact algal growth and polysaccharide content. Temperature, salinity, illuminance, nutrients, and natural disasters may interfere with the distribution of marine algae. To improve mass production, seasonal harvesting is required, and an understanding of physiological and environmental conditions is essential.172,173 The rapid decomposition of algae is also a challenge in algae mass production. Optimized storage facilities may reduce the rate of decomposition. Algal species selection plays a crucial role in the economical aspects of algal-derived polymer production.174 Strain isolation, harvesting, extraction, and residual biomass utilization are some major challenges in microalgae-derived polymer production.175 Chemical processes involved in the chitosan production process such as acidic and alkali treatments are hazardous to the environment. Rather than using conventional chemical and enzymatic methods, ultrasound and microwave technologies should be utilized to overcome the drawbacks. Marine animal waste currently accounts for the majority of chitin and chitosan-derived plastic production, which may restrict its scale-up due to the impurities that necessitate expensive purification and refining of the final product.176

Conclusion and future perspective

The global production of synthetic plastics that ultimately become mismanaged plastic waste amounts to millions of tons every year, resulting in negative impacts on land and marine ecosystems. Biobased plastics were introduced into the market as an alternative to synthetic plastics. However, the agricultural crop-based biomass required for commercial biobased plastic competes with edible food crops for arable lands, freshwater, and limited fertilizer. As an alternative to commercial bioplastics, marine-derived bioplastics have been proposed to meet the current demand for plastic products. Adopting this strategy would be particularly favorable for biodiversity conservation, slowing down the depletion of oil reserves, and limiting greenhouse gas emissions. Bioplastics could be produced from a wide array of marine-derived raw materials including marine micro- and macroalgae, waste generated from marine animals such as fish, crabs, shrimp, mollusks, and lobsters, and marine microorganisms such as halophiles. Additionally, algae waste can also be utilized for plastic production. For instance, low-cost PHA can be produced using marine algae sources or marine microorganisms, as an alternative to commercial high-cost PHA, which requires high-cost carbon sources and sterilization processes. Degradability is another crucial factor that must be considered when manufacturing marine-derived plastics because the main drawback of synthetic plastics is their non-biodegradability. Algae-based bioplastics will not degrade into microplastics and typically degrade in soil within four to six weeks.142,177

Despite the advantages of marine-derived bioplastics, some drawbacks continue to limit their large-scale commercialization and production. Even if the marine raw materials are affordable, the cultivation techniques, pretreatment requirements, extraction processes, and bioplastic conversion technologies needed for bioplastic production are still under development. Therefore, still, the production of bioplastics from marine materials continues to be less cost-effective and efficient compared to synthetic plastics. Conventional seaweed hydrocolloid extraction processes are not cost-efficient because they require the use of high amounts of chemicals and water, and the production method is time-consuming. Every algal species possess different properties and their yields depend largely on the extraction conditions, which also affect the properties of the final bioplastic. Therefore, the identification and selection of the most suitable species and optimum conditions, and the appropriate polymer content are critical. More research must thus be conducted to overcome these limitations before commercialization. Several green extraction processes such as ultrasound-assisted (UAE), microwave-assisted (MAE), enzyme-assisted (EAE), and extrusion-assisted (ExAE) extraction have been developed to reduce costs and chemical usage in conventional processes. Most of these green processes require low amounts of solvents, are environmentally friendly, and non-toxic, achieve fast extraction rates, and are easy to implement compared to conventional processes. Nevertheless, UAE requires additional equipment costs and the enzymes required in EAE are expensive and sensitive to extraction conditions. Additionally, these processes must be further optimized to increase yields and decrease production time.178

Despite the promising potential of marine source-derived bioplastics as an alternative to synthetic plastics and prevailing bioplastics, fully replacing synthetic plastics will take many years. Further research needs to be conducted on novel cultivation techniques, extraction methods, optimal environmental conditions, and degradation ability to overcome the obstacles. Moreover, there are economic issues, clinical rules, and regulations preventing these bioplastics from reaching global market production, and their properties must be optimized for specific applications including biomedical and tissue engineering applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2019R1A2C1007218, 2021R1A6A1A03039211) for financial support. The views presented are of the authors and have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Writing – original draft, P.T.; writing – review & editing and visualization, P.T. and P.C.; conceptualization and validation, P.T., P.C., M.Y. and W.J; funding acquisition and supervision, M.Y. and W.J.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this review paper.

Contributor Information

Myunggi Yi, Email: myunggi@pknu.ac.kr.

Won-Kyo Jung, Email: wkjung@pknu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Sankhla I.S., Sharma G., Tak A. Fungal degradation of bioplastics: an overview. New Futur. Dev. Microb. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020:35–47. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-821007-9.00004-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devi R.S., Kannan V.R., Natarajan K., Nivas D., Kannan K., Chandru S., Antony A.R. In: Environmental Waste Management. Chandra R., editor. CRC Press; 2016. The role of microbes in plastic degradation; pp. 341–370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Plastics Industry - Statistics & Facts | Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/5266/plastics-industry/#dossierKeyfigures.

- 4.Gadhave R.V., Das A., Mahanwar P.A., Gadekar P.T. Starch based bio-plastics: the future of sustainable packaging. OJPChem. 2018;08:21–33. doi: 10.4236/ojpchem.2018.82003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng Y., Wu P., Schartup A.T., Zhang Y. Plastic waste release caused by COVID-19 and its fate in the global ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2111530118. e2111530118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green Guides | Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/truth-advertising/green-guides.

- 7.Cywar R.M., Rorrer N.A., Hoyt C.B., Beckham G.T., Chen E.Y.X. Bio-based polymers with performance-advantaged properties. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021;7:83–103. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00363-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global bioplastics production will more than triple within the next five years Eur. Bioplastics e.V. https://www.european-bioplastics.org/global-bioplastics-production-will-more-than-triple-within-the-next-five-years/.

- 9.Bastos Lima M.G. Toward multipurpose agriculture: food, fuels, flex crops, and prospects for a bioeconomy. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2018;18:143–150. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato N. Production of crude bioplastic-beads with microalgae: proof-of-concept. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019;6:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biteb.2019.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parikh J., Biswas C.D., Singh C., Singh V. Natural Gas requirement by fertilizer sector in India. Energy. 2009;34:954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2009.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lackner M. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.); 2015. Bioplastics; pp. 1–41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mensch F. 2018. Extensive Review of Biodegradation of Most Relevant Bioplastics, Including Their Biodegradation Times in Various Environments. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morinval A., Averous L. Systems based on biobased thermoplastics: from bioresources to biodegradable packaging applications. Polym. Rev. (Phila. Pa). 2021;62:653–721. doi: 10.1080/15583724.2021.2012802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evoware. https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/evoware.

- 16.Fernandez J.G., Ingber D.E. Unexpected strength and toughness in chitosan-fibroin laminates inspired by insect cuticle. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:480–484. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CuanTec . 2022. CuanTec. הארץ.https://www.cuantec.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shellworks . 2023. Shellworks.https://www.theshellworks.com/materials [Google Scholar]

- 19.MarinaTex. https://www.marinatex.co.uk/.

- 20.Bhatia S.K., Otari S.V., Jeon J.M., Gurav R., Choi Y.K., Bhatia R.K., Pugazhendhi A., Kumar V., Rajesh Banu J., Yoon J.J., et al. Biowaste-to-bioplastic (polyhydroxyalkanoates): conversion technologies, strategies, challenges, and perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;326:124733. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatia S.K., Gurav R., Choi T.R., Jung H.R., Yang S.Y., Moon Y.M., Song H.S., Jeon J.M., Choi K.Y., Yang Y.H. Bioconversion of plant biomass hydrolysate into bioplastic (polyhydroxyalkanoates) using Ralstonia eutropha 5119. Bioresour. Technol. 2019;271:306–315. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2018.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satyanarayana K.G., Arizaga G.G., Wypych F. Biodegradable composites based on lignocellulosic fibers—an overview. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009;34:982–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayu A., Handayani T. High-value chemicals from marine macroalgae: opportunities and challenges for marine-based bioenergy development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018;209:012046. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/209/1/012046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usov A.I. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Academic Press; 2011. Polysaccharides of the red algae; pp. 115–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viola R., Nyvall P., Pedersén M. The unique features of starch metabolism in red algae. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2001;268:1417–1422. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Huang J., Che F. Biodiesel - Feedstocks and Processing Technologies. InTech; 2011. Microalgae as feedstocks for biodiesel production. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heimann K., Huerlimann R. Handbook of Marine Microalgae. Elsevier; 2015. Microalgal classification; pp. 25–41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keskinkaya H.B., Akköz C. In: Academic Studies on Natural and Health Sciences. Dalkılıç M., editor. 2019. Use of algae in production of renewable bioplastics; pp. 287–296. (Ankara)). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z., Li X., Xie W., Deng H. Extraction, isolation and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose from industrial kelp (Laminaria japonica) waste. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;173:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Achaby M., Kassab Z., Aboulkas A., Gaillard C., Barakat A. Reuse of red algae waste for the production of cellulose nanocrystals and its application in polymer nanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;106:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Algae Products Market Size, Share | Industry Analysis Report. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/algae-products-market.

- 32.Imeson A., editor. Food Stabilisers, Thickeners and Gelling Agents. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidara M., Yaich H., Richel A., Blecker C., Boufi S., Attia H., Garna H. Effects of extraction procedures and plasticizer concentration on the optical, thermal, structural and antioxidant properties of novel ulvan films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;135:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramu Ganesan A., Shanmugam M., Bhat R. Producing novel edible films from semi refined carrageenan (SRC) and ulvan polysaccharides for potential food applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;112:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guidara M., Yaich H., Benelhadj S., Adjouman Y.D., Richel A., Blecker C., Sindic M., Boufi S., Attia H., Garna H. Smart ulvan films responsive to stimuli of plasticizer and extraction condition in physico-chemical, optical, barrier and mechanical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;150:714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakshmi D.S., Trivedi N., Reddy C.R.K. Synthesis and characterization of seaweed cellulose derived carboxymethyl cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;157:1604–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doh H., Whiteside W.S. Isolation of cellulose nanocrystals from brown seaweed, <scp> Sargassum fluitans </scp> , for development of alginate nanocomposite film. Polym. Cryst. 2020;3:e10133. doi: 10.1002/pcr2.10133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doh H., Dunno K.D., Whiteside W.S. Preparation of novel seaweed nanocomposite film from brown seaweeds Laminaria japonica and Sargassum natans. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;105:105744. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres M.R., Sousa A.P.A., Silva Filho E.A.T., Melo D.F., Feitosa J.P.A., de Paula R.C.M., Lima M.G.S. Extraction and physicochemical characterization of Sargassum vulgare alginate from Brazil. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:2067–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sudhakar M.P., Magesh Peter D., Dharani G. Studies on the development and characterization of bioplastic film from the red seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021;28:33899–33913. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10010-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdul Khalil H.P.S., Chong E.W.N., Owolabi F.A.T., Asniza M., Tye Y.Y., Tajarudin H.A., Paridah M.T., Rizal S. Microbial-induced CaCO3 filled seaweed-based film for green plasticulture application. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;199:150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaimis, U., Ozolina, S., and Jurmalietis, R. (2021). Production of seaweed derived bioplastics. In 10.22616/ERDev.2021.20.TF370