Abstract

Purpose

Support implementation fidelity in intervention research with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and sexual and gender diverse (LGBTQ+) populations, this study explores the systematic development of a fidelity process for AFFIRM, an evidence-based, affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy group intervention for LGBTQ+ youth and adults.

Method

As part of a clinical trial, the AFFIRM fidelity checklist was designed to assess clinician adherence. A total of 151 audio-recorded group sessions were coded by four trained raters.

Results

Adherence was high with a mean fidelity score of 84.13 (SD = 12.50). Inter-rater reliability was 81%, suggesting substantial agreement. Qualitative thematic analysis of low-rated sessions identified deviations from the manual and difficulties in group facilitation, while high-rated sessions specified affirmative and effective clinical responses.

Discussion

Findings were integrated into clinical training and coaching. The fidelity process provides insights into the challenges of implementing social work interventions effectively with LGBTQ+ populations in community settings.

Keywords: LGBTQ+, implementation fidelity, affirmative practice, social work intervention research

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and sexual and gender diverse (LGBTQ+) populations are at greater risk of developing serious mental health issues such as depression, suicidality, and anxiety; necessitating tailored clinical interventions that address their unique stressors (McConnell et al., 2015; Lothwell et al., 2020; Levenson et al., 2021). Affirmative practice is a clinical intervention stance that places LGBTQ+ individuals’ identities, and their culturally specific needs, at the forefront of mental health interventions. Affirmative practice asserts that LGBTQ+ identities are equal to cisgender and heterosexual expressions, incorporates an understanding of minority stress, the unique stress experienced by LGBTQ+ populations, and strives to address the impact of structural inequities through the cultivation of positive self-regard (Craig et al., 2013; Meyer, 2003). Despite an increase in interventions designed for LGBTQ+ populations, there is a paucity of social work research that systematically describes the implementation of affirmative practice (O'Shaughnessy & Speir, 2018).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an empirically supported psychological approach with an extensive evidence base that is effective for a variety of mental health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance use) for adults and adolescents (Weaver et al., 2022; Creed et al., 2011; Hedman et al., 2014; Hofmann et al., 2012). Drawing from cognitive theory, which suggests that emotions and behaviors are influenced by how events are perceived, CBT focuses on identifying, evaluating, and modifying maladaptive thoughts, which in turn prompts emotional and behavioral changes (Beck, 2021). By addressing underlying problematic cognitions and behaviors, more helpful patterns can be fostered, resulting in improved coping and mental health and a reduction in problem behaviors. The purpose of this study is to explore the implementation fidelity of an affirmative CBT group intervention delivered to LGBTQ+ youth and young adults as part of a clinical trial.

Implementation fidelity, critical to intervention research, refers to methodological strategies that enhance the reliability and validity of interventions by assessing adherence to the treatment protocol (Ascienzo et al., 2020; Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli, 2011; Simmons et al., 2014). Treatment fidelity has been historically understudied, with only 3.5% of intervention research in the early 2000s addressing fidelity issues (Perepletchikova et al., 2007) and only 30% of the studies measuring fidelity in a recent systematic review (Walton et al., 2017). Fidelity typically includes the development of concise, comprehensive manuals, extensive training of clinicians, and monitoring of treatment delivery (Gearing et al., 2011). Evaluating fidelity is critical to establish evidence and to ensure that the results of the intervention reflect a true test of the program (Feely, Seay, Lanier, Auslander, & Kohl, 2018). Further, fidelity monitoring promotes external validity by enabling the identification of critical parameters that can be generalized across sessions (Stains & Vickrey, 2017).

Despite a preponderance of manualized CBT intervention research, there is often an implicit assumption that fidelity is maintained, however many studies fail to report fidelity adequately (Waltman et al., 2017). Research examining CBT interventions have measured implementation fidelity most commonly though observational coding; however, differences in the definitions of fidelity components and gaps in the descriptions of training, reliability, and coding processes make comparisons difficult (Rodriguez-Quintana & Lewis, 2018). These processes generally consist of observers rating of CBT sessions with observational adherence scales specialized to the treatment issue (Husabo et al., 2022) or modality (Haddock et al., 2012; Jahoda et al., 2013). Adherence scale development has been described as the construction of a scale for a novel intervention from components of established adherence scales for various modalities assessing therapist behaviors and therapy practices, from which a fidelity score is attained (Segal et al., 2002).

Other research has described using a multi-pronged approach to measuring CBT fidelity, through examining study design, training, intervention delivery, receipt of the intervention, and enactment of intervention skills (Keles et al., 2021). As observational methods of recording fidelity with trained raters are considered the gold standard, research processes generally include the selection of raters familiar with therapy practices, double coding of recorded sessions (i.e., two raters per session), and a process to achieve inter-rater reliability through regular research team meetings and the calculation of reliability metrics (Rodriguez-Quintana et al., 2021). Fidelity research most commonly differs based on its purpose; with efficacy research demonstrating more controlled adherence measures, while effectiveness and feasibility studies may be more methodologically flexible (Naleppa & Cagle, 2010).

Within social work research, Corley and Kim (2015) found that only 2.3% of published intervention research adequately addressed fidelity. In their systematic review, Naleppa and Cagle (2010) found that intervention research did not comprise a significant amount of most social work journals’ overall publications and in those limited studies that addressed fidelity only a third described monitoring processes such as protocol deviation. While the use of treatment manuals facilitates intervention replication, without adequate oversight they cannot alone promise consistent implementation, particularly in multi-site or large-scale intervention research that includes multiple clinicians or treatment sites. While social work measurements of intervention fidelity do not differ significantly from other cognate disciplines measuring treatment adherence, the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics (2017) emphasizes the use of evidence-based practices, necessitating the use of fidelity assessments when establishing an empirical foundation for interventions. Generally, for the field of social work, it is recommended that fidelity research involve the use of treatment manuals, implementer training, supervision of implementation, and measurements of adherence to treatment protocols (Naleppa & Cagle, 2010).

Despite an increased awareness of the importance of implementing evidence-based practices (EBPs) in community settings (Bornheimer et al., 2019), such EBPs are underutilized and often delivered without adequate fidelity to the treatment model (Bond et al., 2011). Establishing implementation fidelity is an important guarantee to organizations that an EBP can be reliably replicated across clinical sites, with diverse populations, by clinicians with varied expertise (Forgatch et al., 2005). The use of an established intervention protocol by clinicians can impact the effectiveness of treatment, yet in a recent study only 66% of trained clinicians reported implementing all steps of interventions (Allen & Johnson, 2015). Fidelity can assist in determining an accurate dosage of training and coaching, provide guidelines on the level of clinical experience and expertise needed to deliver a specialized intervention, and permit research on the standardization of an intervention to limit outcome variability (Miller & Rollnick, 2014). The measurement of treatment fidelity can indicate whether a lack of client improvement is attributed to the clinicians’ delivery of the intervention, the intervention itself, or other external factors, thereby increasing organizational accountability in treatment delivery (Schoenwald et al., 2011). An understanding of intervention fidelity that informs best practices to train and support clinicians is critical to effective EBP (Marques et al., 2019). Research that explores the barriers and facilitators to effective intervention implementation in “real world” settings can contribute to improved outcomes (Schoenwald et al., 2011) as diminished fidelity is often found when implementing successful controlled trials in community settings (Breitenstein et al., 2010).

Proctor and colleagues (2011) recommend five dimensions to attend to when developing fidelity: adherence, exposure to intervention (or dose), quality of delivery (provider skill), component differentiation (between the intervention under study and other modality), and participant responsiveness (or active engagement of participants). Schoenwald et al. (2011) elaborated on the components of clinician adherence, clinician competence, and treatment differentiation. Adherence is defined as the clinician’s close following of prescribed procedures (e.g., intervention manuals), while competence refers to the clinician’s skill and judgment in the delivery of the intervention. Treatment differentiation refers to the extent to which intervention sessions or iterations differ in content and focus. It is recommended that all three components are measured within and across treatment sessions (Perepletchikova et al., 2007).

A fidelity tool can be designed and evaluated once intervention-specific approaches that integrate core components of the training manual have been determined (Feely et al., 2018). Fidelity typically includes indirect observation methods (e.g., review of detailed case notes or evaluations completed by participants) or direct observational methods (e.g., video or audio-recording, an outsider observer during sessions, or the unobtrusive viewing of sessions through a one-way mirror), which assess the degree to which the material was applied and integrated by clinicians and how well they process the intervention components (Gupta & Aman, 2012).

Despite the importance of measuring intervention fidelity in EBP, there is a paucity of research describing the development and implementation of fidelity measures and processes (Corley & Kim, 2015). This gap is particularly apparent in community-based research with marginalized populations. The processes of measuring intervention fidelity in the current study draw from the available literature on CBT fidelity, and are similar in its creation of an adherence scale based on the modality and theoretical components of the intervention, observational raters, and the measurement of inter-rater reliability. This study presents an overview of the development of a fidelity process for AFFIRM, an evidence-based affirmative CBT group intervention in a clinical trial. Delivered across multiple community sites, AFFIRM has been found to significantly reduce LGBTQ+ youth depression and improve coping (Craig et al., 2021a; 2021b). Specifically, this study explores the iterative development of the AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist, a fidelity tool designed to assess clinicians’ adherence to the AFFIRM intervention model and present the results of an initial fidelity assessment. This study differs from the available research in that it provides a detailed breakdown of the fidelity measurement creation, study methodology, and the goal of examining a CBT intervention that specifically affirms the LGBTQ+ population.

Method

The intervention fidelity of the AFFIRM group intervention was studied over a 2-year implementation (2018–2020), delivered face-to-face, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The AFFIRM clinical trial employs a stepped wedge wait-list crossover design with community implementation, in which LGBTQ+ youth and young adults were allocated in a 2:1 ratio to either the AFFIRM intervention at a collaborating agency site, or a wait-list control (Craig et al., 2019).

Surveys measuring depression (Becks Depression Inventory—II; Beck et al., 1996), stress (Stress Appraisal Measure for Adolescents; Rowley et al., 2005), coping (Brief Cope; Carver, 1997) and hope (Snyder et al., 1991) were collected online (using Qualtrics) at four time points (pretest, immediate post treatment), at 6-month, and 12-month follow up (Craig et al., 2019; 2021b). All AFFIRM sessions were audio-recorded. The study, including fidelity measures, was approved by the blinded Research Ethics Board (Protocol ID# 35 229).

The AFFIRM Intervention

AFFIRM is an affirmative CBT group intervention designed to improve coping and reduce depression among LGBTQ+ youth and young adults. AFFIRM has been systematically adapted (Austin & Craig, 2015) for the LGBTQ+ population in order to incorporate an LGBTQ+ affirmative clinical stance and recognition of the external source of anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination that lead to minority stress and resultant mental health disparities (Craig et al., 2013). Therefore, the AFFIRM intervention focuses on helping participants understand how they have internalized (that is, incorporated into their thinking patterns) external systemic anti-LGBTQ+ oppression, and teaches CBT techniques (such as thought records, ABCD method, thought stopping) and activities (exp. self-compassion, connecting to affirmative resources) to embrace an LGBTQ+ affirming worldview (Craig et al., 2021). AFFIRM consists of eight two-hour group sessions: Session 1–2: Introduction to CBT and exploring minority stressors; Session 3–4: cognitive restructuring; Sessions 5–6: coping skills, behavioral activation, setting goals and building hope; Sessions 7–8: social support, self-compassion and integration of new skills.

Participant Description

Although the clinical trial results are detailed elsewhere (Craig et al., 2021b), the total sample of participants (n = 97) in the AFFIRM treatment groups included in the fidelity analysis ranged between the ages of 14 and 29 (M = 21.88 years). Participants’ gender identities included transgender (22.7%), cisgender (19.6%), non-binary (18.6%), gender queer (11.3%), agender (5.2%), and sexual orientations as gay (26.8%), queer (19.6%), pansexual (17.5%), bisexual (12.4%), and lesbian (12.4%). Participants’ ethnic/racial identities included white (47.4%), Asian (20.6%), Black (18.6%), Latinx (6.2%), multi-ethnic (5.2%), Middle Eastern and North African descent (4.1%), and Indigenous Peoples (4.1%). Community organizations that hosted AFFIRM included community health centers, schools, youth centers, HIV service organizations, and hospitals.

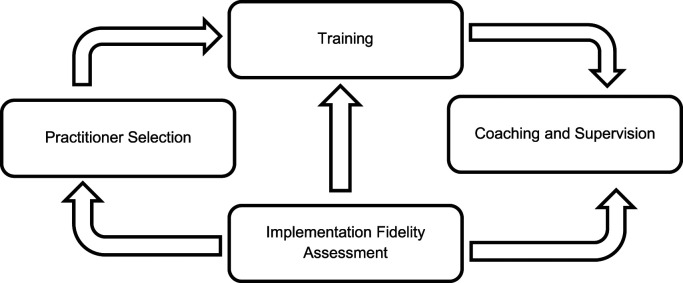

Overall, AFFIRM implementation fidelity followed the processes outlined by Breitenstein et al. (2010), detailed below and in Figure 1. This study has systematically addressed three key aspects of implementation fidelity: adherence, competence and differentiation. This process informed the development of the fidelity checklist, along with the recruitment of qualified experienced clinicians, their training, and ongoing clinical support.

Figure 1.

AFFIRM implementation processes (adapted from Breitenstein, et al., 2010).

Practitioner Rater Selection

Our fidelity process integrated the selection of practitioners, a skilled internal team of clinicians trained in the AFFIRM program and able to offer support and clinical consistency across sites in collaboration with a community clinician. AFFIRM clinicians were selected based on their clinical expertise with LGBTQ+ youth and adults, group facilitation, and CBT training from the social work and psychology fields. For this study, AFFIRM clinicians identify as female (50%), male (33%), transgender (8%), and non-binary (8%), as well as bisexual and/or pansexual (41%), gay (25%), lesbian (16%), straight (16%), and asexual (8%). Clinicians also identify predominantly as white (50%), Asian (42%), and Latinx (8%). AFFIRM community facilitators were experienced case managers or community workers with knowledge of group process and experience providing direct services to LGBTQ+ youth and young adults. Community facilitators were paired with internal AFFIRM clinicians for training purposes. Both internal clinicians and facilitators participated in all training and supervision activities.

Training

The extensive training of AFFIRM clinicians is critical to implementation, with a requirement for completion of a standardized experiential 14-hour training. Described elsewhere, the AFFIRM training led to 94% of participants significantly increasing their clinical competence (Craig et al., 2021c).

Coaching and Supervision

Multiple initiatives support effective implementation: (a) weekly coaching and clinical supervision during a clinician’s first two implementation cycles is provided, and monthly thereafter; (b) internal clinician email communications regarding emerging issues in AFFIRM delivery; (c) quarterly full AFFIRM team meetings are held in which significant clinical cases and events are discussed and feedback is integrated into current implementation, and; (d) regular clinical consultation with the AFFIRM clinical research coordinator and principal investigator to troubleshoot clinical issues. Supervision has also included the auditing of audio-recordings and files to ensure that clinicians are using adequate clinical competencies and to provide directed coaching in individual and group supervision sessions.

Implementation Fidelity Assessment (AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist)

The AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist was iteratively developed by community and academic stakeholders (AFFIRM Fidelity Team) using the processes described by Feely et al. (2018) involving: (1) defining the purpose/scope of fidelity assessment; (2) identifying essential components of the fidelity monitoring system; (3) developing the fidelity tool; (4) monitoring fidelity, and (5) using the fidelity ratings in analyses.

Step 1

Purpose and Scope

Initially the fidelity team defined the purpose and scope of the assessment as monitoring the adherence of clinicians to the AFFIRM model to determine consistency across community sites and iterations. The primary purpose was identified as ensuring the intervention was delivered as intended consistently and that the evaluation measures were assessing the same intervention to ensure comparable results. In order to assess fidelity across different sites and clinicians, three key areas were addressed in the development of the fidelity checklist: (1) affirmative practice (Crisp & McCave, 2007; Craig et al., 2013); (2) CBT (Beck, 1976), and; (3) group facilitation (Wendt & Gone, 2018). Specifically, these components included adherence to the CBT material, demonstration of an affirmative practice stance, and group therapy processing skills. As the checklist was designed to be rated by observers listening to recordings of completed group therapy sessions, the tool needed to be easy to use, with clear and comprehensive indicators.

Step 2

Essential Components of the Monitoring System

According to Feely et al. (2018), an intervention is comprised of the individual skills and ingredients of content delivered to participants, while the process includes the way the content is facilitated. The content of the AFFIRM intervention was comprised generally of CBT skills provided in progressive weekly sessions, in which content builds upon previous weeks, indicating differentiation. Content includes description and application of CBT (e.g., the use of the CBT triangle, description of the influence of thoughts, behaviors, and feelings on mood, and multiple activities related to goal setting). Behaviors demonstrating this essential component include the use of CBT strategies to respond to group members’ experiences of discrimination, reinforcing the critical role of affirmative activities on feelings, and review of sessions’ action plans. AFFIRM also requires that clinicians adopt an affirmative stance, which integrates the CBT content within the context of minority stress and articulates the ways that a discriminatory society affects individuals’ mental health. Key behaviors demonstrating this component include using research and best practice material from the AFFIRM manual and training to respond to participant questions, as well as describing the roots of negative self-concept as influenced by societal discrimination. Group facilitation was identified as an essential component of AFFIRM program integrity, given the impact that effective group skills have on the success of intervention implementation (Wendt & Gone, 2018). Examples of behaviors demonstrating this component were identified as consistent use of active interpersonal skills to build therapeutic alliance, the management of group dynamics, and balancing individual and group needs while also teaching new skills. A paucity of research exists regarding the importance of LGBTQ+ affirmative skills-based group therapy facilitation skills (Lefevor & Williams, 2021), necessitating further examination of these fidelity components.

Step 3

Developing the Fidelity Tool

A fidelity checklist was developed based on the AFFIRM clinician manual, consultation with the clinical and research teams, and a review of relevant methodological literature (see Table 1). In particular, Beck’s CBT rating scales were used to guide the development of the CBT components of the scale (Barber et al., 2003; Young & Beck, 1980). The fidelity tool was intended to measure adherence to the key constructs of the AFFIRM intervention, namely affirmative practice, use of CBT, and group facilitation.

The final version of the checklist included eight key fidelity indicators: (1) delivers the AFFIRM intervention as intended; (2) demonstrates an affirmative stance towards diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions; (3) presents psychoeducational material (on LGBTQ+ identities, minority stress, health/mental health outcomes, trauma, resilience, coping) using best available evidence and an affirmative stance; (4) enhances participant knowledge about the importance of key sources of coping and resilience for LGBTQ+ youth and adults, including engaging in identify affirming activities, receiving identity affirming support (online and offline), finding and maintaining hope; (5) effectively utilizes the CBT model to help participants engage in behaviors that affirm their LGBTQ+ identities and improve their mood; (6) effectively utilizes group facilitation skills; (7) utilizes a global session rating, and; (8) completes and integrates session activities (see Table 2). The fidelity checklist also includes an optional open-ended section for raters to explain or justify scores.

Table 1.

AFFIRM Implementation Fidelity Checklist.

| Indicator Number | Description |

|---|---|

| Fidelity indicator 1 | Delivers the AFFIRM intervention as intended |

| Fidelity indicator 2 | Demonstrates an affirmative stance toward diverse sexual orientations and gender identities and expressions (SOGIE) (e.g., validation, support and celebration of LGBTQ+ identities, non-binary conceptualization of gender, absence of heterosexism/cissexism) |

| Fidelity indicator 3 | Presents psychoeducational material (on LGBTQ+ identities, minority stress, health/mental health outcomes, trauma, resilience, coping) using best available evidence and an LGBTQ+ affirmative stance |

| Fidelity indicator 4 | Enhances participant knowledge about the importance of key sources of coping and resilience for LGBTQ+ youth including: engaging in identify affirming activities (online and offline), receiving identity affirming support (online and offline), finding and maintaining hope |

| Fidelity indicator 5 | Effectively utilizes the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model to help participants engage in behaviors that affirm their LGBTQ+ identity and improve their mood |

| Fidelity indicator 6 | Effectively utilizes group facilitation skills |

| Fidelity indicator 7 | Global session rating |

| Fidelity indicator 8 | Effectively completes and integrates session activities |

Table 2.

AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist Description.

| Examples | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Behaviors | Inadequate | Excellent |

| Indicator 1: Delivers the AFFIRM intervention as intended | • Does the facilitator follow and complete all materials associated with the session in order? | Not all materials associated with session were completed, facilitators use only some talking points to guide discussion | Facilitators did a great job using talking points |

| • Does the facilitator use the facilitator talking points to guide implementation of the session? | |||

| • Does the facilitator complete session delivery in time allotted? | |||

| Indicator 2: Demonstrates an affirmative stance toward diverse sexual orientations and gender identities and expressions | • Does the facilitator explicitly express value for diverse LGBTQ+ identities? | One participant advised another participant during an activity that “LGBT” is a new acronym. Facilitators did not address this misinformation | Facilitators were affirming of LGBTQ+ identities |

| • Does the facilitator model appropriate use of names, pronouns, terminology, and language? | |||

| • Does the facilitator identify when biased language has been used? | |||

| • Does the facilitator correct misinformation? | |||

| • Does the facilitator consistently avoid perpetuating heterosexist or cissexist ideas? | |||

| Indicator 3: Presents psychoeducational material (on LGBTQ+ identities, minority stress, health/mental health outcomes, trauma, resilience, coping) using best available evidence and an LGBTQ+ affirmative stance | • Does the facilitator use research and best practice information from the AFFIRM training and manual? | Facilitators could integrate more best practice information from the AFFIRM manual | Great use of research and best practice information to implement the session and respond to participants |

| • Does the facilitator use research and best practice information from the AFFIRM training and manual to respond to questions/concerns within sessions? | |||

| • Does the facilitator present material in a clear, understandable appropriate | |||

| • Does the facilitator articulate the roots of negative views of self/LGBTQ+ identity? | |||

| Indicator 4: Enhances participant knowledge about the importance of key sources of coping and resilience for LGBTQ+ youth including: engaging in identify affirming activities (online and offline), receiving identity affirming support (online and offline), finding and maintaining hope | • Does the facilitator use research and best practice information from the manual to present information on LGBTQ+ specific sources of coping and resilience? | Facilitators did not discuss LGBTQ+ specific sources of coping and resilience, and was limited in exploration of coping strategies. Did not focus on challenging negative messages | Facilitators did a great job and used research and best practices from the AFFIRM manual |

| • Does the facilitator explore participants’ coping strategies and make clear the importance of LGBTQ+ specific sources of coping and resilience? | |||

| • Does the facilitator help or teach participants challenge negative messages about self particularly (but not limited to) LGBTQ+ identities? | |||

| Indicator 5: Effectively utilizes the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model to help participants engage in behaviors that affirm their LGBTQ+ identity and improve their mood | • Does the facilitator consistently use strategies rooted in the CBT framework to help youth express their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to discrimination? | Facilitator did not consistently use strategies rooted in a CBT framework. | Facilitator was very effective at using strategies rooted in CBT. |

| • Does the facilitator consistently reinforce the critical role of affirmative activities on feelings? | |||

| • Does the facilitator review and process the action plan from the previous session? | |||

| • Does the facilitator review the expectations for the action plan for the upcoming session? | |||

| Indicator 6: Effectively utilizes group facilitation skills | • Does the facilitator consistently use active listening/interpersonal skills to form an alliance with participants and group (reflections, affirmations, validation, summaries) | There was lots of participant side talk and joking that interfered with the session activities. Facilitators did not cue participants which resulted in frequent interruptions. | Facilitators did a good job with structure, and teaching content to participants |

| • Does the facilitator effectively manage group dynamics (e.g., conflict, overtalkers or undertalkers)? | |||

| • Does the facilitator effectively balance both individual and group needs (i.e., the two client system of a group)? | |||

| • Does the facilitator demonstrate an ability to structure each specific segment of the group session (group norms/check in/group reflection, agenda and goals, skills building, check out, group reflection)? | |||

| • Does the facilitator demonstrate an ability to teach new skills or content to participants? | |||

| Indicator 7: Global session ratings | • Facilitator is able to engage participants as evidenced by participant engagement (the degree to which participants are engaged or actively participating; for example, cues of agreement with facilitator from participants) | The session was confusing. Explanations regarding activities were not concise or clear. Participants did not engage actively with session material | Facilitator was charismatic and engaging. The facilitators provided a supportive, affirmative environment for the participants |

| • Overall session quality (how well a session was delivered- can include clarity, conciseness, charisma, facilitation skills, etc.) | |||

| Indicator 8: Effectively completes and integrates session activities | • Session activities Example: Explaining CBT, effects of Anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, thought stopping activity, hope box activity |

The closing activity was abruptly cut off because the session had gone overtime. One participant dominated this activity and others did not have an opportunity to share. One participant was cut off in the midst of sharing and this did not seem to be addressed | Facilitator did a great job integrating CBT and focusing on participant’s sources of coping and resilience. Facilitator was supportive and did great with relating to and normalizing participant’s experiences |

Step 4

Monitoring Fidelity and Rating Procedures

Each session was rated using the AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist. The ratings were completed by four raters, who were enrolled in a Social Work program (three Master’s level, one Bachelor’s level). Raters were selected based on their clinical and research experience working with LGBTQ+ populations and their knowledge of affirmative practice. Raters were not trained AFFIRM facilitators, but had worked as research assistants on the AFFIRM project. Prior to being assigned to rate sessions using the Fidelity Checklist the four raters received 16 hours of coding training by the first and third authors. Raters coded the sessions independently and as a group to establish agreement. Four raters were randomly assigned to rate 151 audio-recorded sessions of AFFIRM, totaling 302 hours of coding. Inter-rater reliability estimates were generated by randomly selecting 35% of sessions (n = 53) using the randomization feature on SPSS software version 26 (IBM Corp Released, 2019). These sessions were rated independently by two raters, which resulted in 106 separate coded sessions (i.e., 212 hours of groups). The inter-rater agreement was examined by calculating the proportion of observed agreement between raters, and the Cohen’s Kappa Statistic. Importantly, full AFFIRM intervention series (eight sessions) were coded so that raters could identify session differentiation and progression. For each behavior, sessions were given a score from 0 (low) to 3 (high) and an overall session score from 0 to 5, as suggested by previous research (Landis & Koch, 1977). For each indicator a summary score was calculated by totaling behavior scores, and finally the indicator scores were combined to create an overall fidelity score (out of 100). The overall fidelity score indicates the strength of the session’s affirmative CBT approach. The approach of using a fidelity checklist with a calculated fidelity score has been relatively standard practice across research studies, in which data is aggregated to a specified unit of analysis, and can be replicated and specialized for various interventions, yet some variations in the use of the fidelity score exist across studies (Mowbray, 2003). The fidelity score can be calculated through the total measurement of scales examining occurrence–nonoccurence (simply rating an item as present or absent), or through frequency ratings (rating the extensiveness of interventions during the session), depending on the needs of the researchers (Waltz et al., 1993). Fidelity scores, typically reporting on adherence, dose, or participant responsiveness, have seen a decrease in quality and reporting in intervention research over time, perhaps due to a lack of interest in the complexity of fidelity assessment, a lack of agreement on the definition of fidelity, or even space limitations in publications (Slaughter et al., 2015). However, given the benefit to implementation and the important processes underpinning the creation and application of fidelity tools, this important aspect of intervention research is a recommended practice in the social work literature (Naleppa & Cagel, 2010).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the fidelity rating and adherence to the study protocol. The inter-rater agreement was examined by calculating the proportion of observed agreement between raters, and Cohen’s Kappa Statistic. To calculate Cohen’s Kappa statistic and the observed agreement, the score was transformed into five categories—Poor Fidelity to High Fidelity (Landis & Koch, 1977). Correlational analysis was used to examine the inter-correlations among the eight fidelity indicators. Qualitative data was obtained from notes that raters made justifying scores. Notes more commonly followed low-rated sessions; however, some justified high fidelity-scoring sessions. Thematic analysis connected to each fidelity rating was utilized for the 73 notes justifying scores found in the AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist. Although not necessarily unique in social work fidelity research (Powers, et al., 2017; Odden, et al., 2019; Palmer, et al., 2019), the mixed-methods approach allowed for a richer understanding of the causes of low and high fidelity scores for particular sessions and was a holistic method to capture the implementation processes and context, the multimodal (audio and written data) (Craig et al., 2021), and triangulate raters’ assigned scores and their notes on their scoring process.

Results

Quantitative

AFFIRM Fidelity Adherence

Adherence was generally high as the mean fidelity score is 84.13 (SD = 12.50), suggesting high fidelity and alignment with extant implementation fidelity literature (Hepner et al., 2011).

Inter-Rater Reliability

Cohen’s Kappa statistic resulted in an alpha of 0.6, with the proportion of observed agreement between raters resulting in 81%, suggesting substantial fidelity agreement.

Inter-Correlations

All fidelity indicators showed a moderate to strong correlation with the total fidelity score (r= 0.21–0.82). Most indicators scores were strongly correlated with two to eight other indicator scores (see Table 3). Indicator two, demonstrating an affirmative stance toward diverse sexual orientations and gender identities and expressions, had the least number of correlations with other indicators.

Table 3.

Inter-Correlations for Fidelity Indicators.

| Indicator | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Delivers as intended | — | ||||||||

| 2. Demonstrates an affirmative stance | −0.02 | — | |||||||

| 3. Uses best available evidence | 0.38*** | 0.31*** | — | ||||||

| 4. Enhances knowledge of coping and resilience | 0.37*** | 0.23* | 0.62*** | — | |||||

| 5. Effectively utilizes CBT affirming behaviors | 0.35*** | 0.19* | 0.60*** | 0.51*** | — | ||||

| 6. Effective group facilitation | 0.39*** | 0.16 | 0.71*** | 0.38*** | 0.62*** | — | |||

| 7. Global session ratings | 0.50*** | 0.18 | 0.60*** | 0.40*** | 0.59*** | 0.80*** | — | ||

| 8. Session content | 0.39*** | 0.05 | 0.34*** | 0.33*** | 0.37*** | 0.34*** | 0.47*** | — | |

| 9. Total score | 0.66*** | 0.21* | 0.78*** | 0.65*** | 0.74*** | 0.80*** | 0.82*** | 0.52*** | — |

| Total possible score | 9 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 20 | 100 |

| Mean score (SD) | 7.38 (1.47) | 14.82 (0.60) | 9.96 (1.99) | 7.61 (1.63) | 9.54 (1.88) | 13.07 (2.29) | 7.06 (1.30)) | 15.32 (7.3) | 84.13 (12.50) |

***p>0.001 ** p>0.05 * p>0.01.

Qualitative

Qualitative analysis yielded themes connected to fidelity items and served to provide additional mixed-methods data that supplemented and further explored the quantitative findings. An analysis of the raters’ notes for low scores in the AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist showed that raters attributed low scores to a lack of adherence to the manual, holding discussions that were “off-topic,” and required session activities not being fully described, which resulted in some confusion for participants. Other reasons for low scores included clinicians presenting material out of order and not completing key curricular activities, and a lack of adequate time spent on intervention core concepts (e.g., minority stress, thinking traps). Deviations from the manual were attributed to clinicians’ time management. Time constraints appeared to be a commonly cited factor for low fidelity adherence and raters attributed this to several causes including adequate pacing of activities and discussions, group members not engaging well with the material, and a variance in required activities between sessions.

Additional issues impacting low scores included a lack of attention given to group processing by the clinicians, including inattention to mutual aid. Some low fidelity rated notes discussed how group sessions appeared to be too informal, and more like social time for members instead of a clinical intervention. Sessions that were rated with low fidelity were also explained as not facilitated affirmatively, such as clinicians using gendered language to refer to group members or presenting material without attention to the diverse learning needs and abilities of group members. Raters also noted deviations from the intervention manual that were interpreted as flexible minor adaptations that were made deliberately by clinicians to address the group’s needs. Such changes and deviations included the clinicians drawing on material from other weeks’ sessions, or by spending time on debriefing and processing in a group when the members required it before returning to the facilitation of content. Generally, raters noted that clinicians were able to facilitate consistently with the manual, however they did notice instances when facilitation could have been improved through a more meaningful application of the theoretical content to the group participants’ current needs. For instance, one rater comments stated: “Facilitators did a great job incorporating research and best practice to present educational material and respond to participants in session. Facilitators could have used more talking points to elevate presentation of psychoeducational material and respond to participants in session.”

These notes are indicative of sessions in which the group was facilitated consistently with the manual, incorporating the spirit of the intervention (affirmative practice), while providing a baseline responsiveness to the clinical needs of the participants. Raters noted that sessions with higher fidelity scores were more likely to have clinicians completing the entirety of the intervention consistently with the manual, adhered to CBT in sessions even when it was not explicitly emphasized in the manual session content, responded appropriately to participant questions and concerns, facilitated group participation, and managed time well. These findings underscore the need for skilled and adept clinicians in the delivery of manualized interventions.

Discussion

This study described the development and application of a fidelity monitoring tool and process for an affirmative group CBT intervention (AFFIRM) for LGBTQ+ youth and young adults. The results of this research suggest that clinicians highly adhered to the AFFIRM intervention protocol, with good treatment fidelity and inter-rater reliability. The AFFIRM fidelity score (M=84.13) is relatively consistent with other intervention research. Similarly, in their application of affirmative CBT to individual therapy with gay and bisexual young men, Pachankis and colleagues (2015) achieved a mean fidelity rating of 84.6% in a review of 23.5% of their sessions. However, only sessions in which clinicians requested clinical supervision were rated by one coder placing limits on the comparability of these results to the present study which rated all intervention sessions with multiple coders.

The inter-correlation analysis found that all indicators showed a moderate to strong correlation. While high correlations with some deviations are expected, these results demonstrate good internal consistency, suggesting that this fidelity measures checklist is a valuable contribution to the evaluation of the AFFIRM program. The indicator with the least number of inter-correlations was Indicator Two: Demonstration of an affirmative stance toward diverse sexual orientations and gender identities and expressions. This may be because evaluating affirmative practice can be especially nuanced and more difficult to observe or measure than the other items present on the checklist such as the presence or absence of CBT skill delivery. Another possible reason indicator two had the least number of inter-correlations may be due to a ceiling effect given the skills and experience most clinicians have working with the LGBTQ+ population; a finding shared by other research examining clinician LGBTQ+ cultural competence (Alessi et al., 2015; Leitch et al., 2021). These findings may also point to the difference between psychotherapeutic processing and delivering psychoeducation. As the indicator regarding affirmative practice concerns the processing stance of the clinician, it appears not to be significantly correlated with indicators that focus exclusively on the delivery of content (such as Indicator 8: Session Content). The affirmative practice indicator also differs from Indicator six: Group facilitation, potentially demonstrating that competency in LGBTQ+ affirmative practice is a distinctive practice skill that requires training and supervision (Dillon & Worthington, 2003).

The qualitative analysis provided specific information related to fidelity ratings that can inform ongoing implementation. Findings suggest the importance of adequately preparing clinicians to provide affirmative group therapy interventions. Clinician readiness is best addressed through the recruitment of qualified clinicians that have experience delivering EBPs in addition to knowledge of the LGBTQ+ community, comprehensive training and intensive supervision and coaching throughout intervention delivery (Cannata & Marlowe, 2017). Clinicians who are best suited to facilitate AFFIRM have been extensively trained in the model, are proficient in group therapy and CBT, and have experience working with the LGBTQ+ communities. In sessions with low fidelity ratings, clinicians who did not demonstrate the baseline clinical social work competencies required to practice with the LGBTQ+ population or deliver CBT struggled to deliver AFFIRM consistently with the manual, which speaks to the importance of ongoing monitoring. Higher scores may have been attributed to the extensive AFFIRM clinical supervision available to clinicians and the mentoring process (e.g., reviewing of recorded sessions, quarterly team check-ins, and the availability of a senior clinician providing clinical support). In response to the findings from this study, the frequency of session review and coaching increased.

Clinicians and facilitators who hold affirmative attitudes demonstrate greater self-efficacy in working with LGBTQ+ clients in affirmative practice (Alessi et al., 2015). Affirmative clinical approaches are an important element of treatment fidelity (Craig et al., 2021a; 2021b; Packankis, 2018). In this study, affirmative approaches identified by the raters included demonstrating cultural competence (e.g., by addressing participants’ intersectional needs, and using correct pronouns), ensuring accessibility of session material, and tailoring discussions to participant experiences and identities. Providing affirmative CBT in a group therapy format is a way to effectively offer EBP that integrates the benefits of groups for marginalized populations (Söchting et al., 2010; Malekoff, 2015) with the strengths-based affirmative approach found to support LGBTQ+ youth mental health (Craig et al., 2013). During this study, fidelity was particularly high when clinicians demonstrated strong group facilitation skills and flexibly responded to participant input while guiding them through the manualized intervention. Demonstrating clinician flexibility in addressing the needs of the group can be an important and necessary component of making the treatment relevant and accessible (Anyon et al., 2019), thus flexibility can be considered a necessary component of optimal social work intervention delivery (Washington et al., 2014).

The results of this study contribute to our understanding of intervention fidelity in community-based research and practice. Although fidelity protocols have been critiqued for their resource requirements (McHugh et al., 2009), they can ensure effective replication and improved impact in real world settings (Wolery, 2011). The AFFIRM Fidelity Checklist is a relatively simple tool that captures the critical elements of affirmative group CBT implementation. Such a checklist may enhance monitoring during a clinical trial or may help improve clinical training, and supervision, and generate specific implementation strategies to enhance program materials. For example, the results of this study (e.g., specific information on group facilitation, affirmative clinical strategies and the importance of adherence) were integrated into the AFFIRM training model and manual as well as clinical coaching and supervision approaches.

Finally, the utility of using a mixed-methods approach to analysis allowed the researchers a more nuanced understanding of the specific factors impacting low or high fidelity-scoring sessions. Themes gleaned from raters’ interpretations of results could result in solutions to low fidelity scores, thus allowing for targeted clinical feedback and supervision with specific examples that could enable the AFFIRM intervention to be delivered more consistently and with fidelity. The mixed-methods fidelity approach provided a more holistic perspective of the intervention implementation, which seems particularly important for social work research, which considers the person (clinician, client) in the environment (group) when evaluating manualized interventions. Although the mixed-methods approach to analyzing fidelity is not a standard approach, this present study found that the addition of a qualitative analysis is an accessible means to provide more insight and context to the fidelity scores and contribute to improved intervention fidelity if integrated into clinical supervision.

Limitations

Several limitations of this research must be noted. While most of the fidelity raters were graduate student research assistants, which is considered optimal for coding fidelity (Rodriguez-Quintana & Lewish, 2018), the raters were not trained in AFFIRM and were novice clinicians. It is unknown whether more experienced clinicians would yield different results. As well, the groups coded in this study were sessions completed in the first half of a 5-year clinical trial and only captured the sessions delivered in person, prior to the COVD-19 pandemic. Therefore, the findings may be an underestimation of fidelity, as the training, clinical consultation and supervision may have improved as the research progressed. As affirmative practice was the fidelity indicator least inter-correlated, future studies should focus on refining our understanding of affirmative skills in the context of CBT groups. Only two coders analyzed the qualitative data, potentially limiting rigor. As well, the concept of a fidelity score is applied inconsistently in the literature and requires further study (Slaughter et al., 2015). Finally, these findings may have limited applicability to affirmative CBT delivered to individuals.

Conclusion

This research details the development and monitoring of program fidelity for a tailored intervention for LGBTQ+ youth and adults delivered in community. This study specifically examines affirmative therapy practices for a population that has previously been neglected in the provision of evidence-based programming (Wheeler & Dodd, 2011). Conducting fidelity checks on affirmative care ensures that interventions are effectively delivered to LGBTQ+ youth and adults. The creation of a specific fidelity measure that is consistent with the theoretical principles of a program is important to describe as affirmative interventions become more embedded into the social work practice landscape and can serve as an approach for the development of intervention research with marginalized populations.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada through a Partnership Grant (SSHRC #895–2018-1000) and by the Public Health Agency of Canada through their Community Action Fund (PHAC #1718-HQ-000,697). The funders had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analyses, interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

ORCID iD

Dr. Shelley Craig https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7991-7764

Rachael V. Pascoe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3784-5571

Dr. Gio Iacono https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5285-7020

Nelson Pang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6399-8272

Ali Pearson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3566-0186

References

- Alessi E. J., Dillon F. R., Kim H. M. (2015). Determinants of lesbian and gay affirmative practice among heterosexual clinicians. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 298–307. 10.1037/a0038580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B., Johnson J. (2015). Utilization and implementation of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of maltreated children. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 80–85. 10.1177/1077559511418220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyon Y., Roscoe J., Bender K., Kennedy H., Dechants J., Begun S., Gallager C. (2019). Reconciling adaptation and fidelity: Implications for scaling up high quality youth programs. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(1), 35–49. 10.1007/s10935-019-00535-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascienzo S., Sprang G., Eslinger J. (2020). Disseminating TF‐CBT: A mixed methods investigation of clinician perspectives and the impact of training format and formalized problem‐solving approaches on implementation outcomes. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 26(6), 1657–1668. https://doi-org/10.1111/jep.13351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A., Craig S. L. (2015). Empirically supported interventions for sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 12(6), 567–578. https://doi-org/10.1080/15433714.2014.884958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. P., Liese B. S., Abrams M. J. (2003). Development of the cognitive therapy adherence and competence scale. Psychotherapy Research, 13(2), 205–221. 10.1093/ptr/kpg019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. S. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R. A., Brown G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory manual. : Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bellg A. J., Borrelli B., Resnick B., Hecht J., Minicucci D. S., Ory M., Ogedegbe G., Owig D., Ernst D., Czajkowski S., Treatment (2004). Fidelity workgroup of the NIH behavior change consortium enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond G., Becker D., Drake R. (2011). Measurement of fidelity of implementation of evidence-based practices: Case example of the IPS Fidelity Scale. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(2), 126–141. https://doi-org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01244.x [Google Scholar]

- Bornheimer L. A., Acri M., Parchment T., McKay M. M. (2019). Provider attitudes, organizational readiness for change, and uptake of research supported treatment. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(5), 584–589. https://doi-org/10.1177/1049731518770278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fielity in public health clinical trials. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71(S1), S52–S63. https://doi-org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein S. M., Gross D., Garvey C. A., Hill C., Fogg L., Resnick B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing and Health, 33(2), 164–173. 10.1002/nur.20373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannata E., Marlowe D. B. (2017). Building strong clinicians: Education strategies to promote interest and readiness for evidence-based practice. Families in Society, 98(1), 35–43. https://doi-org.ca/10.1606/1044-3894.2017.7 [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavoral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley N.A., Kim I. (2015). An assessment of intervention fidelity in published social work intervention research studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(1), 53–60. https://doi-org/10.1177/1049731515579419 [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., Austin A., Alessi E. (2013). Gay affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual minority youth: A clinical adaptation. Clinical Social Work Journal, 41(3), 258–266. 10.1007/s10615-012-0427-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., Eaton A. D., Leung V. W., Iacono G., Pang N., Dillon F., Austin A., Pascoe R., Dobinson C. (2021. a). Efficacy of affirmative cognitive behavioural group therapy for sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults in community settings in Ontario, Canada. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–15. https://doi-org.ca/10.1186/s40359-021-00595-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., Iacono G., Austin A., Eaton A. D., Pang N., Leung V. W., Frey C. J. (2021. c). The role of facilitator training in intervention delivery: Preparing clinicians to deliver AFFIRMative group cognitive behavioral therapy to sexual and gender minority youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 33(1), 56–77. 10.1080/10538720.2020.1836704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., Leung V. W., Pascoe R., Pang N., Iacono G., Austin A., Dillon F. (2021. b). AFFIRM online: Utilising an affirmative cognitive–behavioural digital intervention to improve mental health, access, and engagement among LGBTQA+ youth and young adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1541. 10.3390/ijerph18041541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., McInroy L. B., Eaton A. D., Iacono G., Leung V. W. Y., Austin A., Dobinson C. (2019). Project youth AFFIRM: Protocol for implementation of an affirmative coping skills intervention to improve the mental and sexual health of sexual and gender minority youth. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(6), e13462. 10.2196/13462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig S. L., McInroy L., Goulden A., Eaton A. (2021). Engaging the senses: Triangulating qualitative data analysis using transcripts, audio, and video. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–12. 10.1177/16094069211013659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creed T.A., Reisweber J., Beck A. (2011). Cognitive therapy for adolescents in school settings. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp C., McCave E. L. (2007). Gay affirmative practice: A model for social work practice with gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Child Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(4), 403–421. 10.1007/s10560-007-0091-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon F. R., Worthington R. L. (2003). The lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative counseling self-efficacy inventory (LGB-CSI): Development, validation, and training implications. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 235–251. https://doi-org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.235 [Google Scholar]

- Feely M., Seay K. D., Lanier P., Auslander W., Kohl P. L. (2018). Measuring fidelity in research studies: A field guide to developing a comprehensive fidelity measurement system. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(2), 139–152. https://doi-org/10.1007/s10560-017-0512-6 [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch M. S., Patterson G. R., DeGarmo D. S. (2005). Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 3–13. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80049-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing R. E., El-Bassel N., Ghesquiere A., Baldwin S., Gillies J., Ngeow E. (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 79–88. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A. K., Aman H. (2012). An evaluation of training in a brief cognitive-behavioral therapy in a non-English-speaking region: Experience from India. International Psychiatry: Bulletin of the Board of International Affairs of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 9(3), 69–71. 10.1017/S174936760000326X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock G., Beardmore R., Earnshaw P., Fitzsimmons M., Nothard S., Butler R., Eisner E., Barrowclough C. (2012). Assessing fidelity to integrated motivational interviewing and CBT therapy for psychosis and substance use: The MI-CBT fidelity scale (MI-CTS). Journal of Mental Health, 21(1), 38–48. 10.3109/09638237.2011.621470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., El Alaoui S., Lindefors N., Andersson E., Rück C., Ghaderi A., Kaldo V., Lekander M., Andersson G., Ljótsson B. (2014). Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of internet-vs. group-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: 4-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 59, 20–29. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner K.A., Howard S., Paddock S.M., Hunter S.B., Osilla K.C., Watkins K.E. (2011). A fidelity coding guide for a group cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. RAND Corporation. http://119.78.100.173/C666/handle/2XK7JSWQ/3329. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S. G., Asnaani A., Vonk I. J., Sawyer A. T., Fang A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi-org.ca/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husabo E., Haugland B.S.M., McLeod B.D., Baste V., Haaland Å.T., Bjaastad J.F., Hoffart A., Raknes S., Fjermestad K.W., Rapee R.M., Ogden T., Wergeland G.J. (2022). Treatment fidelity in brief versus standard-length school-based interventions for youth with anxiety. School Mental Health, 14(1), 49–62. https://doi-org/10.1007/s12310-021-09458-2 [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda A., Willner P., Rose J., Kroese B. S., Lammie C., Shead J., Woodgate C., Gillespie D., Townson J., Felce D., Stimpson A., Rose N., MacMahon P., Nuttall J., Hood K. (2013). Development of a scale to measure fidelity to manualized group-based cognitive behavioural interventions for people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(11), 4210–4221. 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keles S., Bringedal G., Idsoe T. (2021). Assessing fidelity to and satisfaction with the “adolescent coping with depression course” (ACDC) intervention in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 1–20. https://doi-org.ca/10.1186/s12888-016-0954-y [Google Scholar]

- Landis J. R., Koch G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/2529310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevor G. T., Williams J. S. (2021). An interpersonally based, process-oriented framework for group therapy with LGBTQ clients. In Lund E. M., Burgess C., Johnson A. J. (Eds), Violence against LGBTQ+ persons (pp. 347–359). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch J., Gandy-Guedes M., Messinger L. (2021). The psychometric properties of the competence assessment tool for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(11), 1785–1812. https://doi-org/10.1080/00918369.2020.1712138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J. S., Craig S. L., Austin A. (2021). Trauma-informed and affirmative mental health practices with LGBTQ+ clients. Advance online publication. Psychological Services 10.1037/ser0000540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothwell L. E., Libby N., Adelson S. L. (2020). Mental health care for LGBT youths. Focus, 18(3), 268–276. 10.1176/appi.focus.20200018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malekoff A. (2015). Group work with adolescents (3rd Edition). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marques L., Valentine S. E., Kaysen D., Mackintosh M., Dixon De Silva L. E., Ahles E. M., Youn S. J., Shtasel D. L., Simon N. M., Wiltsey-Stirman S. (2019). Provider fidelity and modifications to cognitive processing therapy in a diverse community health clinic: Associations with clinical change. Journal of Consultations in Clinical Psychology, 87(4), 357–369. 10.1037/ccp0000384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell E. A., Birkett M. A., Mustanski B. (2015). Typologies of social support and associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health, 2(1), 55–61. 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R. K., Murray H. W., Barlow D. H. (2009). Balancing fidelity and adaptation in the dissemi- nation of empirically supported treatments: The promise of transdiagnostic interventions. Behavior Research and Therapy, 47(11), 946–953. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin, 129(5), 674-697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Rollnick S. (2014). The effectiveness and ineffectiveness of complex behavioral interventions: Impact of treatment fidelity. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 37(2), 234–241. 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray C.T., Holter M.C., Teague G.B., Bybee D. (2003). Fidelity criteria: Development, measurement, and validation. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(3), 315–340. 10.1016/S1098-2140(03)00057-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naleppa M. J., Cagle J. G. (2010). Treatment fidelity in social work intervention research: A review of published studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(6), 674–681. 10.1177/1049731509352088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers . (2017). NASW Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy T., Speir Z. (2018). The state of LGBQ affirmative therapy clinical research: A mixed-methods systematic synthesis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 82–98. https://doi-org/10.1037/sgd0000259 [Google Scholar]

- Odden S., Landheim A., Clausen H., Stuen H.K., Heiervang K.S., Ruud T. (2019). Model fidelity and team members’ experience of assertive community treatment in Norway: A sequential mixed-methods study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13, 1–12. 10.1186/s13033-019-0321-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis J., Hatzenbuehler M., Rendina H., Safren S., Parsons J. (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behvioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. 10.1037/ccp0000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packankis J. E. (2018). The scientific pursuit of sexual and gender minority mental health treatment: Toward evidence-based affirmative practice. American Psychological, 73(9), 1207–1219. 10.1037/amp0000357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J.A., Parker V.A., Barre L.R., Mor V., Volandes A.E., Belanger E., Loomer L., McCreedy E., Mitchell S.L. (2019). Understanding implementation fidelity in a pragmatic randomized clinical trial in the nursing home setting: A mixed-methods examination. Trials, 20, 1–10. https://doi-org.ca/10.1186/s13063-019-3725-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F., Treat T. A., Kazdin A. E. (2007). Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 829–841. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power K., Hagans K., Linn M. (2017). A mixed-method efficacy and fidelity study of check and connect. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 1019–1033. https://doi-org./10.1002/pits.22038 [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi-org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp Released . (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk. Version 26.0. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Quintana N., Lewish C. C. (2018). Observational coding training methods for CBT treatment fidelity: A systematic review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(4), 358–368. https://doi-org/10.1007/s10608-018-9898-5 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Quintana N., Walker M.R., Lewis C.C. (2021). In search of reliability: Expert-informed training methods for conducting observational coding of cognitive behavioural therapy fidelity. Journal of Cognitive Psychotheray: An International Quaterly, 35(4), 308–329. 10.1891/JCPSY-D-20-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley A.A., Roesch S.C., Jurica B.J., Vaughn A.A. (2005). Developing and validating a stress appraisal measure for minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 28(4), 547–557. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald S. K., Garland A. F., Chapman J. E., Frazier S. L., Sheidow A. J., Southam-Gerow M. A. (2011). Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration Policy and Mental Health, 38(1), 32–43. https://doi-org/10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z.V., Teasdale J.D., Williams J.M., Gemar M.C. (2002). The mindfulness-based genitiveve therapy adherence scale: Inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clinical Psychology and Psychotheray, 10(1), 131–138. https://doi-org./10.1002/cpp.320 [Google Scholar]

- Simmons R., Pappas L., Boucher K., Boonyasiriwat W., Gammon A., Vernon S., Burt R.M., Stroup A.M., Kinney A. (2014). Implementation of best practices regarding treatment fidelity in the family colorectal cancer awareness and risk education randomized controlled trial. SAGE Open, 4(4), 1–13. https://doi-org/10.1177/2158244014559021 [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter S.E., Hill J.N., Snelgrove-Clarke E. (2015). What is the extent and quality of documentation and reporting of fidelity to implementation strategies: A scoping review. Implementation Science, 10(1), 129. 10.1186/s13012-015-0320-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder C. R., Harris C., Anderson J. R., Holleran S. A., Irving L. M., Sigmon S. T., Yoshinobu L., Gibb J., Langelle C., Harney P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi-org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söchting I., Wilson C., De Gagné T. (2010). Cognitive behavioral group therapy (CGBT): Capitalizing on efficiency and humanity. In Bennett-Levy J., Richards D., Farrand P., Christensen H., Griffiths K., Kavanagh D., Klein B., Lau M.A., Proudfoot J., Ritterband L., White J., Williams C. (Eds), Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions (pp. 323–330). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stains M., Vickrey T. (2017). Fidelity of implementation: An overlooked yet critical construct to establish effectiveness of evidence-based instructional practices. CBE Life Sciences Education, 16(1), 1–10. 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltman S. H., Sokol L., Beck A. T. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy treatment fidelity in clinical trials: review of recommendations. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 13(4), 311–315. 10.2174/1573400514666180109150208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton H., Spector A., Tombor I., Michie S. (2017). Measures of fidelity of delivery of, and engagment with, complex face-to-face health behavior change interventions: A systmatic review of measure quality. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(4), 872–903. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1111/bjhp.12260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J., Addis M.E., Koerner K., Jacobson N.S. (1993). Testing the integrity of a psychotherapy protocol: Assessment of adherence and competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 16(4), 620–630. https://doi.org/0022-006X/9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington T., Zimmerman S., Cagle J., Reed D., Cohen L., Beeber A.S., Gwyther L.P. (2014). Fidelity decision making in social and behavioral research: Alternative measures of dose and other considerations. Social Work Research, 38(3), 154–162. 10.1093/swr/svu021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A., Zhang A., Landry C., Hahn J., McQuown L., O’Donnell L.A., Harrington M.M., Buys T., Tucker K.M., Pfeiffer P., Kilbourne A.M., Grogan-Kaylor A., Himle J.A. (2022). Technology-assisted, group-based CBT for rural adults’ depression: Open pilot trial results. Research on Social Work Practice, 32(2), 131–145. 10.1177/10497315211044835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt D. C., Gone J. P. (2018). Complexities with group therapy facilitation in substance use disorder specialty treatment settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 88, 9–17. https://doi-org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D. P., Dodd S. J. (2011). LGBTQ capacity building in health care systems: A social work imperative. Health and Social Work, 36(4), 307–310. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A275852176/AONE?u=anon∼c8f438d7&sid=googleScholar&xid=cdc08b51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery M. (2011). Intervention research: The importance of fidelity measurement. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(3), 155–157. https://doi-org/10.1177%2F0271121411408621 [Google Scholar]

- Young J., Beck A. T. (1980). Cognitive therapy scale: Rating manual. Center for Cognitive Therapy, University of Pennsylvania. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]