Abstract

Background

The triangular relationship between climate change-related events, patterns of human migration and their implications for health is an important yet understudied issue. To improve understanding of this complex relationship, a comprehensive, interdisciplinary conceptual model will be useful. This paper investigates relationships between these factors and considers their impacts for affected populations globally.

Methods

A desk review of key literature was undertaken. An open-ended questionnaire consisting of 11 items was designed focusing on three themes: predicting population migration by understanding key variables, health implications, and suggestions on policy and research. After using purposive sampling we selected nine experts, reflecting diverse regional and professional backgrounds directly related to our research focus area. All responses were thematically analysed and key themes from the survey were synthesised to construct the conceptual model focusing on describing the relationship between global climate change, migration and health implications and a second model focusing on actionable suggestions for organisations working in the field, academia and policymakers.

Results

Key themes which constitute our conceptual model included: a description of migrant populations perceived to be at risk; health characteristics associated with different migratory patterns; health implications for both migrants and host populations; the responsibilities of global and local governance actors; and social and structural determinants of health. Less prominent themes were aspects related to slow-onset migratory patterns, voluntary stay, and voluntary migration. Actionable suggestions include an interdisciplinary and innovative approach to study the phenomenon for academicians, preparedness and globalized training and awareness for field organisations and migrant inclusive and climate sensitive approach for policymakers.

Conclusion

Contrary to common narratives, participants framed the impacts of climate change-related events on migration patterns and their health implications as non-linear and indirect, comprising many interrelated individual, social, cultural, demographic, geographical, structural, and political determinants. An understanding of these interactions in various contexts is essential for risk reduction and preventative measures. The way forward broadly includes inclusive and equity-based health services, improved and faster administrative systems, less restrictive (im)migration policies, globally trained staff, efficient and accessible research, and improved emergency response capabilities. The focus should be to increase preventative and adaptation measures in the face of any environmental changes and respond efficiently to different phases of migration to aim for better “health for all and promote universal well-being” (WHO) (World Health Organization 1999).

Keywords: Migration, Climate change, Health systems, Migrant's health, Well-being, Disasters

1. Introduction

To achieve the vision of the 2030 agenda of Sustainable development, healthy lives, and well-being for all at all ages should be promoted (Goal 3). The seventieth World Health Assembly resolution (Assembly, 2017) urged the WHO Member States and Director General to promote the health of refugees and migrants and develop The Global Action Plan (2019–2023). The plan aims to address the health and well-being of migrants and refugees in an inclusive and comprehensive manner and through good-migration governance and refugee assistance in any given settings (Director-General 2019). This plan prioritizes public health interventions focusing on developing emergency and humanitarian health responses (Director-General 2019), which is very relevant to climate-related mobility.

In 2019, the highest mid-year figure ever reported for displacements associated with disasters was recorded (Director-General 2019). Environment-related displacements are now more common than conflict-related displacements (Director-General 2019) and this phenomenon incorporates both environmental and sociological consequences. Environmental changes impact on political, economic, and health dimensions of populations, in turn sometimes resulting in the need to migrate and potentially affecting the health of both migrating and host populations (Ridde et al., 2019). Migration is a determinant of health (Vearey, 2014), which means that environment-related migration can increase vulnerability or resilience, similar to other forms of migration and can affect human health and wellbeing in both positive and negative ways (Schwerdtle et al., 2018). Migration can be seen as an adaptation strategy of coping, a health seeking behaviour (McMichael et al., 2012) or resilience, and is not necessarily an indicator of vulnerability (McLeman and Smit, 2006). Because migration itself can cause health risks; the adaptive potential of migration cannot be assumed (Schwerdtle et al., 2018).

It is important that authorities working for health and migration sector are aware of the risks and opportunities faced by migrants affected by climate related events and those who are left behind, so they can intervene at different stages of migration (Schwerdtle et al., 2019). Migrants have diverse backgrounds, and risk and vulnerability are dependant on circumstances they are surrounded by (Veary et al., 2010). However, the global Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the gaps and inequalities of health care access to poor and rich (Jones, 2020) within countries and between countries. Global efforts to reach the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) health targets have so far shown a lack of sufficient progress likely aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic and to some extent by weak health information systems and large data gaps in different regions (World Health Organization 2020).

We briefly illustrated some more literature with the following published scenarios that draw attention to the challenges related to health and migration faced by populations affected by climate change associated events.

| Scenario 1: Inclusive Healthcare and Advisory Services |

| A physician in New York (Lawrence, 2020) shares the experience of a female patient who had migrated from a community from Northeast Africa where many people including her local doctor left due to drought, high-temperatures and resource-mismanagement. The patient wasn't eligible to apply for asylum in U.S.A. The physician highlights that most health service-providers report low self-assessed knowledge about this topic and there is a need of training on the health impact of climate change in relation to migration, so patients can be given informed-treatment and legal referrals (Lawrence, 2020). |

| Scenario 2: Integrated Support and Continuity of Care |

| A thematic analysis about the refugee and Ugandan nationals in Nakivale refugee camp (Uganda) reported severe disruption of their daily life due to uncertain climate events. Extreme rains ruined their home-grown farms and the heat made it difficult for people to walk for longer distances. Patients who needed to reach HIV clinics faced barriers to get timely and costly transportation. Choosing between the food and clinic appointment became a hard choice for many (O'Laughlin et al., 2021). |

| Scenario 3: Planned relocation and Support from authorities |

| Populations may need to plan more relocations in advance due to drought, crop failure or flooding etc. The government of Fiji has been efficiently working on adaptation measures, aiming to meet the basic human rights, thus preventing huge damages and losses. Support and health opportunities should continue post-relocation and during reintegration. A study on Fiji reports that increased usage of packaged food and alcohol, disruption to social ties and traditions (after relocation) can have negative consequences for overall health and mental wellbeing (McMichael and Powell, 2021). |

The health implications of climate-related migration have previously been explored (Schwerdtle et al., 2018) and informed the research and conceptual model presented in this paper. A systematic literature assessment suggests research community to adopt systems thinking to explore this nexus, to provide policy-relevant and actionable insights and incorporate climate change and health into migration research (Schwerdtle et al., 2020). Researchers are exploring the different drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change (Parrish et al., 2020). A study about this nexus has explored the perceptions of primary health care workers in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) (Scheerens et al., 2021). Participants perceive migration patterns in SSA as mainly economic and health motivated or conflict related, rather than uniquely motivated by climate change (Scheerens et al., 2021). Another study developed a pilot dynamic simulation model to project and understand relationships between variables related to climate migration and public health in different contexts (Reuveny, 2021). The author suggests to include expert opinions and empirical results to develop the parameters and functions of such social science-based models (Reuveny, 2021). One paper has applied a generalized climate-migration conceptual model to understand the local context of Malawi and has presented the method to illustrate key variables for future quantitative modelling and testing (Parrish et al., 2020).

This three-way relationship of the nexus of health, migration and climate change remains under-examined (Hunter et al., 2018) and a conceptual model guided by interdisciplinary expert's opinion is missing. This could be due to its interdisciplinary nature, lack of data, heterogeneity of groups or lack of agreement on common definitions (ProfSA et al., 2016), however previously noted: “without a framework to connect the three issues, research agendas are likely to expand in different directions and policy responses to develop in an inconsistent fashion” (Schütte et al., 2018). Moreover, due to the rapid and non-linear progression of global climate change, there is an urgency that is added (Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer, 2020; Turner, 2014) and a holistic understanding of the phenomenon, actionable suggestions, and an impact on the ground for the frontline field workers and most importantly the people who are experiencing these changes are needed. The aim of this paper is therefore to build a conceptual model connecting the given nexus, based on the interdisciplinary expert's opinions. The model would address the circumstances and factors leading to varying migratory patterns, the associated health implications due to climate-related events, and the role and implications of the governance systems in places of origin and host regions.

2. Methods

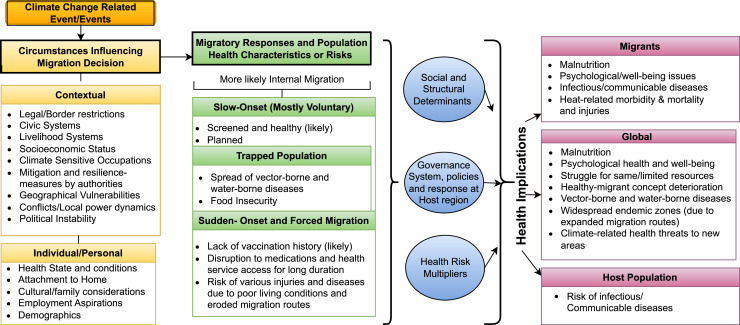

This is an exploratory study and follows a qualitative approach. The paper studies the views and facts about the key topics related to the nexus as presented by the key experts, and we further discussed it in the light of recent literature. The focus of the conceptual model in our study is global. The model (Fig. 1) visually portrays the concepts and elements of the phenomenon under study and their inter-relationships (Eriksson, 2003). Fig. 2 summarizes the actionable suggestions given by the experts.

Fig. 1.

A Conceptual Model of Climate Change, Migration and Health.

Fig. 2.

Suggestions given by the respondents about the Climate change, migration, and health nexus.

2.1. Selection of participants

We ensured the respondents were representative of various regional and disciplinary backgrounds, recruiting climate scientists, climate change migration experts, climate change and health experts, migration and health experts in research, academics and individuals working directly in the field. Initially 35 experts were identified and approached using purposive sampling via email on the criteria of experience level, expertise in different domains and qualification. From this initial sample, we narrowed down to nine expert participants (Appendix B) for the study based on our criteria and willingness on the behalf of the experts as Covid-19 had started and many of our participants were engaged in the response to it.

2.2. Open-ended survey questionnaire

A structured and open-ended questionnaire was used (Howitt and Cramer, 2011). The questionnaire tool with eleven questions (Appendix A) was piloted with two colleagues at the Regional Office of the International Organization of Migration (IOM) in Brussels. The questionnaire was divided up into key areas/themes that were identified by our literature review. First five items focused on the risks, characteristics and predictability of migrating populations in the light of climate change and other associated variables. The next theme had a total of 4 items which focused on the implications on the health state of the migrating and host populations in the light of global climate change. The last two questions were about actionable policy and research, which had a total of 2 items which focused on the opinion of the experts on the areas that need to be studied by researchers and how to best inform policymakers.

2.3. Data analysis and conceptual model building

Following the conceptual framework method developed by Ritchie, Spenser and O'Connor (Ritchie et al., 2014), we analysed the data starting with identifying codes, clustering them manually into broader themes, and then followed by synthesising the themes into models. Firstly, we generated codes of each answer by each participant, then used these codes to generate themes from each answer and used these themes to generate mini-models. These two steps are shown in Appendix B; the third step was to combine these mini-models into a conceptual model (Fig. 1) which is then discussed in the results section, highlighting the conceptual model of migration and health under the influence of global climate change. The same process was done to generate a second model, (Fig. 2), which shows the actionable suggestions based on expert's responses related to policy and research.

3. Results

According to the respondents global climate change represents a phenomenon that is going to have far reaching impacts both in the short and long run. As global climate firstly affects the environment it is likely to impact the liveability of certain areas and adversely affect the civic capabilities and systems of those regions. These are likely to have to affect the migration decision of populations who are directly impacted and most of the experts agree that the first likely scenario is going to be internal migration as it is accessible to people. We can see that for instance in Pakistan as record levels of flooding have affected nearly a quarter of the country, most of the movement has been internal (Joles, 2022). However, according to our respondents all types of migratory responses ranging from voluntary to forced are likely to increase due to global climate change. The process of migration and the conditions from which the population is moving is likely to impact their health as natural disasters are often associated with disease outbreaks and collapse of civic structures which exacerbate the problem. It is likely that the climate related changes are going to affect the healthcare systems of host populations as well such as warmer climates providing a better environment for pathogens and migration is going to add pressure upon that which requires a structural and government response to it. These steps are likely to be determinants of the health for both the host and particularly the migratory populations. In its entirety this process can have global health implications directly, as vector borne diseases, lapses of vaccinations, malnutrition can affect large populations and indirectly, as populations can be put into a state where they have to compete for limited resources. The model is described below in detail followed by actionable suggestions which focus on what can be done to address these issues both in the long and short run by organisations in the field, academia and policymakers.

The key themes and findings from the interviews are as follows:

3.1. Circumstances influencing migration decisions

Respondents emphasised that existing weak civic systems, reliance on natural livelihood resources and climate-sensitive occupations make a population more vulnerable against environmental risks. These civic insecurities can be related to food, water, and political insecurity, developmental factors, poverty, political factors, broader social factors, treatment, and assistance given in times of need, loss of infrastructure and livelihoods. Populations are more likely to migrate if authorities lack efforts to build resilience against direct and indirect effect of environmental impacts. These effects and changes can be slow-onset or sudden onset and they may amplify existing pressures to migrate. Some personal/individual factors that may play a role behind mobility decisions include employment aspirations, geographical vulnerabilities, socioeconomic status, age, gender, education, marital status, or disability. Furthermore, conflicts, local power dynamics and political instability may also influence the decision to stay or leave.

These impacts can also result in populations getting trapped due to demographic barriers/factors or the inability to afford mobility. Existing chronic health conditions, legal/border restrictions, age, gender, cultural values and emotional attachment with the homeland could be a factor due to which people stay behind.

3.2. Migratory responses and population health characteristics

The impact of climate change on migratory responses is largely heterogeneous, and there is lack of consensus on definitions. Some respondents report that predictions about migratory behaviours are challenging, nevertheless, others predicted that voluntary or forced cross-border migration will increase and will be more likely towards economically more advanced and more habitable areas, to adjacent countries, and to politically more liberal and securer countries, and from less developed to more developed countries. Migratory responses can also be influenced by mainstream media coverage of ongoing or predicted environmental events. However, most climate related migration is internal and would remain so; voluntary or forced.

“It is up to governments to determine who is most affected”, stated one respondent when asked who would be most affected by climate change-associated disasters. All respondents thought that population experiencing forced migration may lack access to health services and vaccinations for longer journeys and in their destination regions and could be at risk of various injuries and diseases (especially infectious) if their journey involves destroyed/eroded routes, poor living conditions and overcrowded areas of settlement. Populations are often healthier and are likely to be health-screened when they migrate after planning and voluntarily. Slow-onset climate events can often result in slow-onset migratory responses which could include circular labour migration and planned relocation, where populations may have time for thoughtful decision making. Migrants also tend to have attachments (emotional or tangible) with the places of origin, especially when they keep in touch with the people left behind.

3.3. Social and structural determinants and government's response

There are some social and structural factors that determine the health consequences for affected populations. It includes governance system at origin and host regions. Effective government response regarding adaptation and mitigation efforts in climate-sensitive areas including rehabilitation efforts, improvement of civic systems, legislation around health care of migrants, and coordinated emergency response will have positive impacts. The access to migrant inclusive health care, health mediation, awareness in communities about climate events, the socioeconomic status of migrants, resources and services at resettlement areas, and circumstances during different migration phases are some determinants of health. Restrictive policies in receiving countries are likely to have a negative impact on the health of migrants.

Some factors can aggravate health risks which include barriers accessing healthcare, fragile health care systems, warmer climates (pathogens can reproduce more effectively), lack of access to clean water, poor ventilation, lack of food security, sanitation and hygiene issues, migration to natural reserves, population density, regional conflicts, discrimination, and poor overall integration.

3.4. Health implications for migrants and host populations

Health implications depend on social and structural determinants and governments’ response. Health implications for the migrant populations are likely to be malnutrition, vector-borne diseases, infectious/communicable diseases, heat-related morbidity & mortality, and mental health and well-being issues. Mobile population is less likely to have possession of needed medications for longer durations. They may not have easy access to food and water security or sanitation services. There is also a danger of physical injuries while migrating through disrupted/eroded routes affected by climate disasters. Furthermore, already scarce health care resources and medical facilities in a host region can have negative health implications for all living there i.e., may cause to spread communicable diseases. This impact depends on the size of the arriving population, geographical area of origin, epidemiological gradients, capacity of the host region's health system, and host region's response capability. Possible reactionary civil or political moves by local populations may result in discrimination in accessing health care. Trapped populations might be at risk of the spread of vector-borne and water-borne diseases amongst other health issues they have in common with other migrants.

3.5. Global health implications

Some health implications can become a global problem if not attended to timely. It is possible that malnutrition-related health problems, psychological health issues, vector-borne as well as air and water-borne diseases, and newly emerging and re-emerging diseases may increase. Populations may have to compete for the same and limited resources and the health of migrants may be negatively affected.

3.6. Suggestions for field organizations, researchers and policy makers

Respondents suggest doing more research about migration-aware and climate-sensitive health systems, impact of slow-onset climate events on health, mental health care, effect of disturbed social networks and the idea of identity loss due to displacements. It is also suggested to research about adaptation measures to prevent forced migration and trapped populations. Respondents have endorsed interdisciplinary, neutral, empirical, mixed-methods approach and systems thinking to implement large-scale cohort studies, case-control studies, predictive and conceptual modelling, regional studies, and the use of artificial intelligence. It is very important to cover the social and structural determinants, be sensitive of the local population dynamics, avoid problematic terminology that regards migrants as ‘objects’, and understand previous patterns of mobility before working on regional policies and projects.

Suggestions for organizations working in the field include trainings at global level to prepare the staff for emergencies, sharing of resources and open access communications for better coordination, improved bureaucratic systems and public liaison.

Suggestions for policy makers given by respondents include improved health systems in origin and resettlement areas, strong policies for risk-reduction and adaptation, and migration-inclusive health policies. Policymakers would benefit from in-depth understanding of the effects of climate change, its health, economic, and ethical dimensions, and the effect on migration.

4. Discussion

4.1. ‘Natural’ disasters and human agency

Our study explored the complex and interdependent triangle of health, migration, and climate change related events. The findings support previous literature noting that climate change related impacts may increase the risks for populations due to their contextual and individual level vulnerabilities (Turral et al., 2011; Roncoli et al., 2001; MdM et al., 2014). We found that these issues may influence their migration choices (Warner et al., 2012). This may indicate a need to change the narrative about ‘natural’ disasters and focus more on resilience and lack of resources, and the role of human agency to prevent the disasters (Mizutori, 2020). Individuals already suffering from human-rights violations, chronic diseases, disabilities, unemployment, and people living in unsafe or marginal environments are also likely disproportionally affected by adverse human-rights consequences of climate adversities (Levy and Patz, 2015) and this poses a huge risk to their overall well-being. A recent study implies that the likelihood of conflicts and thus forced migration outflows may be reduced if adaptive policies to deal with the effects of climate-change are made in developing countries (Abel et al., 2019).

People may decide to voluntary stay at the place of disaster due to issues surrounding cultural identity and economics, and those trapped (involuntary stay) may occur due to some political factors and policies (Zickgraf, 2019). However, these complex and subjective aspirations regarding the decision to migrate or not to migrate in the face of an climate event could be elicited by reality-based research and policy approaches, (Zickgraf, 2019) which is currently lacking (Mallick and Schanze, 2020). Also, there is a variable pattern in the influence wealth, household levels and resources have during climate change events and migration, and the precise meaning of the concept of ‘household capability’ or ‘economic capacity’ is not consistent and comparable across studies, resulting in a research gap (Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer, 2020), calling to consider diverse community and regional factors.

4.2. Health implications

On the occasion of the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), International Organization for Migration (IOM), the World Health Organization (WHO) and Lancet Migration has emphasized the urgent need to address the dire consequences for migrants’ health and global public health due to climate crisis (Cornacchione, 2021). An environmental crisis in the place of origin can lead to the disruption of health-care services (Eichner and Brockmann, 2013; Khan et al., 2016), and our results imply that most climate-related migration is predicted to happen within low-income regions where populations already face health challenges (McMichael, 2020). A scientific research assessment defines three elements of vulnerability in the context of climate change and human health: exposure, sensitivity or susceptibility to harm, and capacity to adapt or to cope (U.S. Global Change Research Program (2009-) 2016). Our findings indicate that these elements can vary depending on certain demographic factors and geographical vulnerability. This puts some populations at risks of more adverse health consequences, and the risk may increase with diminishing options for mitigation, which is supported by literature (Levy and Patz, 2015). Forced displacement in such a situation may increase adverse health impacts (McMichael, 2015), which could be mitigated through adaptive responses (McMichael, 2015), respondents hope. Planning is key and we found in the interviews a consensus that slow onset environment effects allows better decision-making about migration (Dannenberg et al., 2019) and therefore should allow for timely adaptive measures.

Results highlight the research gap about the loss of relational networks due to climate related event, which could impact the well-being of migrants. There is a strong correlation between the loss of social capital and emotional conditions such as depression and anxiety (Michielin et al., 2020). The disruption of existing social ties and attachments may negatively impact mental health of the effected population (Torres and Casey, 2017). Such mental health and psychosocial dynamics of displaced communities should be a priority, as “social supports are essential to protect and support mental health and psychosocial well-being” (Inter-Agency Standing Committee 2007). Furthermore, mental health is linked to one's physical health, including chronic diseases and nutritional deficiencies that displaced migrants tend to experience (Padhy et al., 2015).

4.3. Integrated response mechanisms

The global compact for migration (UN General Assembly 2019) recognizes that it's important to develop and integrate assistance efforts and mechanisms at the sub-regional and regional levels. To address the health vulnerabilities of populations affected by sudden-onset and slow-onset environmental disasters, “Health systems should be climate-resilient and migrant inclusive” (Schwerdtle et al., 2018). Health systems tend to run by national governments, and populations impacted by disasters may not have same healthcare entitlements in another country or region. This is expected to impact many people because people displaced by climate-related reasons are not simply eligible to have refugee status (UNHCR 2016) evident from a case from Kiribati (OHCHR 2020). Therefore, health staff needs to be mindful of a patient's uncertain movement and changing legal status. “Our health systems are static, but people are not” (Farmer, 2019). Thus, continuity of care is important; for example portable therapies and integrated health systems can support mobile populations during their journeys and uncertain settlements and avoid disruptions. (Farmer, 2019). One effective example to follow is electronic Personal Health Record (e-PHR) platform that is implemented by IOM and adapted by some EU member states. (IOM. E-PHR [Internet] 2016).

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes access to health services while taking care of the dignity of all refugees and migrants (Khan et al., 2016). Migrants are a heterogeneous groups but even during national crisis and response plans, migrants are not always involved nor considered (Zenner and Wickramage, 2020). Due to their precarious working conditions, restricted health care access, restricted mobility due to border closures and disrupted remittances, excluding migrants from the warning system and preparedness plans could increase health vulnerabilities for many (Zenner and Wickramage, 2020). The host region's health system capacity and resources, if are non-inclusive or insufficiently prepared, may pose challenges for all. Literature reports that it may increase the risk of various diseases at different phases of migration, for example due to overcrowded and unhygienic conditions in transit or reception centres (Greenaway and Castelli, 2019; McMichael, 2015; Angeletti et al., 2020). Alert systems in risk areas, disaster preparedness, safer modes of transport, social acceptance for displaced people, capacity for increasing number of patients and medical facilities are some helpful actions. Civic responsibilities could also include training and awareness raising sessions. Unfortunately, several LMICs with displaced populations may lack the resources to implement needed actions.

Integrated support and coordination between the national governments, UN agencies, (I)NGOs and civil society organizations having the expertise of climate change adversities, migration, WASH facilities, and healthcare is needed to save limited resources and may improve the efficiency of actions taken, keeping in mind both cross-border and internal migrants. For example, destroyed or unattended camps, muddy roads, blocked pathways, looting, destroyed WASH facilities, limited food and health care resources and medical supplies, and a lack of education about healthcare and rights are some of the issues that can be addressed and prevented, especially if actions are integrated, and could result to accelerate services provision.

4.4. The way forward

Policymakers and organizations in the field may wish to consider investing in awareness, accessibility and availability of migrant inclusive health services, and risk reduction and adaptation towards changing climate. Conversely, restrictive policies in receiving countries by authorities often have a negative impact on health and service contact as demonstrated by a systematic review of vaccination coverage of migrants in Europe (Mipatrini et al., 2017). The Covid-19 pandemic has made health inequalities including healthcare access for refugees and migrants and the lack of coordination more visible (Bartovic et al., 2021).

Academic discussion and educational resources on the subject are suggested to be coherent and understandable for the public and stakeholders. Research and project collaborations with local communities should consider involving local, traditional, or religious representatives. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are strongly advised to be kept in consideration in research planning.

If populations and their livelihood resources are saved from the negative impact of climate adversities or if they have awareness and access to less risky routes to migrate; some risks and diseases can be prevented. In times of the COVID-19 pandemic, the necessity of migrant inclusive health care initiatives and coordinated health systems and service provision is more pertinent (Kluge et al., 2020). Insufficient actions can aggravate health implications, and this can turn global, as seen in the pandemic.

4.5. Limitations

Our study provides a unique multidisciplinary insight about the nexus. However, representatives of more regions and important stakeholders including migrants affected by environmental events could add to the inclusiveness of data and should be included in future studies. The conceptual model in the present study is made using respondent's views and further examined using literature, and empirical data, but empirical validation of the direction and local context of different aspects of the model has not yet been done, which is something for future quantitative as well as qualitative research to follow on. Another limitation could be that the data collection started during the uncertain starting months of Covid-19 pandemic, due to which most interviews had to be done remotely with less flexibility for follow up responses. But we kept our survey interview questions open-ended and gave the participants sufficient time to respond.

5. Conclusion

Our work supports a proactive approach as the nexus of global climate change, migration and health is likely to play out in a complex manner with both long and short term and direct and indirect consequences. Having such a wide perspective would ensure that access to health and mental health services would be treated as a right for all and timely delivered as a preventative method before it can become detrimental to global health across multiple populations.

The interaction between environmental events, mobility decisions and the migration process may depend on the level of exposure, rapidity of the event, contextual factors, and individual capacities to cope with the event, and this interaction is usually multidirectional and is likely to be non-liner as such it cannot be viewed in isolation from social, political, economic and geographical perspectives. An understanding of the interactions of various social and structural determinants in the context of different settings and regions is important for disaster preparedness, predict and prevent negative health outcomes, and this conceptual model would facilitate to highlight the key variables.

Our research suggests that it is advisable to forward plan and improving adaptive responses and the ability to mitigate against climate adversities including the establishment of climate sensitive infrastructure and provision of efficient and timely health services to all; based on the principles of equity, climate-sensitivity, global and regional coordination, inclusivity, and cultural competence. Hence, a useful strategy could be to shift the paradigm about climate change and its subsequent effects on migration and health implications towards a more evidence-based framework and to understand this nexus for what it is: global, therefore, provide an incentive for various stakeholders to make necessary changes and cooperate on the issue. These steps can enable policy makers to focus on higher accountability, increased efficiency and effectiveness from institutional responses towards the phenomena.

Ethical Approval Statement

"This research was approved in the proposal colloquium conducted by the Examination board of the Erasmus Mundus European Master in Migration and Intercultural Relations' (EMMIR) program consortium at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany."

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

One co-author Dominik Zenner is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Migration and Health.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the support of all key experts who contributed their time and expertise during the interviews.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2023.100172.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- World Health Organization, editor. Health21: the health for all policy framework for the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: world Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; 1999. 224 p. (European health for all series).

- World Health Assembly. Promoting the health of refugees and migrants: resolution, Seventieth World Health Assembly [Internet]. World Health Assembly; 2017 May. Report No.: WHA70.15. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/promoting-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants.

- Director-General. Promoting the health of refugees and migrants: draft global action plan, 2019–2023 [Internet]. 2019 May p. 13. (SEVENTY-SECOND WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY). Report No.: A72/25 Rev.1. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/promoting-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-draft-global-action-plan-2019-2023.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT FROM JANUARY TO JUNE 2019 Mid-year figures [Internet]. 2019. Available from: http://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2019-mid-year-figures_for%20website%20upload.pdf.

- Ridde V., Benmarhnia T., Bonnet E., Bottger C., Cloos P., Dagenais C., et al. Climate change, migration and health systems resilience: need for interdisciplinary research. F1000Res. 2019;8:22. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.17559.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vearey J. Healthy migration: a public health and development imperative for South(ern) Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014;104(10):663. doi: 10.7196/samj.8569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtle P., Bowen K., McMichael C. The health impacts of climate-related migration. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0981-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael C., Barnett J., McMichael A.J. An ill wind? climate change, migration, and health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(5):646–654. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeman R., Smit B. Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Clim. Change. 2006;76(1–2):31–53. doi: 10.1002/wcc.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtle P.N., Bowen K., McMichael C., Sauerborn R. Human mobility and health in a warming world. J Travel Med [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2019 Oct 24];26(1). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/doi/10.1093/jtm/tay160/5280412. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Veary, J., Wheeler B., Jurgens-Bleeker S. Migration and Health in SADC, A review of the literature [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://ropretoria.iom.int/sites/default/files/Lit_Review_WEB.pdf.

- Jones O. We're about to learn a terrible lesson from coronavirus: inequality kills [Internet]. The Gaurdian. 2020. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/14/coronavirus-outbreak-inequality-austerity-pandemic.

- World Health Organization. World health statistics 2020: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals [Internet]. 2020 May. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240005105.

- Lawrence K. Climate migration and the future of health care. Health Aff. 2020;39(12):2205–2208. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Laughlin K.N., Greenwald K., Rahman S.K., Faustin Z.M., Ashaba S., Tsai A.C., et al. A social-ecological framework to understand barriers to HIV clinic attendance in Nakivale refugee settlement in Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(6):1729–1736. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03102-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael C., Powell T. Planned relocation and health: a case study from Fiji. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(8):4355. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtle P.N., McMichael C., Mank I., Sauerborn R., Danquah I., Bowen K.J. Health and migration in the context of a changing climate: a systematic literature assessment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020;15(10) [Google Scholar]

- Parrish R., Colbourn T., Lauriola P., Leonardi G., Hajat S., Zeka A. A critical analysis of the drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change: a new conceptual model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(17):6036. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerens C., Bekaert E., Ray S., Essuman A., Mash B., Decat P., et al. Family physician perceptions of climate change, migration, health, and healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa: an exploratory study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(12):6323. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuveny R. Climate-related migration and population health: social science-oriented dynamic simulation model. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):598. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10120-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter L.M., Henry S., McMichael C., Bocquier P. Climate, Migration and Health: an Underexplored Intersection [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.populationenvironmentresearch.org/pern_files/papers/OverviewPaper.pdf.

- Matlin ProfSA, Depoux D.A., Schutte D.S., Schaeffner P.E., Kurth ProfT, Stöckemann S., et al. Climate migration and health Conference Report [Internet]. Université Paris Descartes, Paris: Université Sorbonne Paris Cité /Centre Virchow-Villermé for Public Health Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu (AP-HP) 1 place Parvis Notre-Dame, F-75004 Paris; 2016 [cited 2019 Oct 24] p. 1–45. Available from: http://virchowvillerme.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Climate-Migration-and-Health_2016.pdf.

- Schütte S., Gemenne F., Zaman M., Flahault A., Depoux A. Connecting planetary health, climate change, and migration. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(2):e58–e59. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczan D.J., Orgill-Meyer J. The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights. Clim. Change. 2020;158(3–4):281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Turner G. The University of Melbourne, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute; Parkville VIC: 2014. Is Global Collapse imminent? [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson D.M. A framework for the constitution of modelling processes: a proposition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003;145(1):202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Howitt D., Cramer D. 3. ed. Prentice Hall; Harlow: 2011. Introduction to Research Methods in Psychology; p. 449. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Lewis J., McNaughton Nicholls C., Ormston R. 2nd edition. Sage; Los Angeles: 2014. Qualitative Research practice: a Guide For Social Science Students and Researchers; p. 430. editors. [Google Scholar]

- Joles B. Pakistan's Climate Migrants Face Tough Odds. 2022 21; Available from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/21/pakistan-climate-change-migration-flood/.

- Turral H., Burke J.J., Faurès J.M. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome: 2011. Climate change, Water and Food Security; p. 174. (FAO water reports) [Google Scholar]

- Roncoli C., Ingram K., Kirshen P. The costs and risks of coping with drought: livelihood impacts and farmers’ responses in Burkina Faso. Clim. Res. 2001;19:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- MdM Islam, S Sallu, Hubacek K., Paavola J. Vulnerability of fishery-based livelihoods to the impacts of climate variability and change: insights from coastal Bangladesh. Reg. Environ. Change. 2014;14(1):281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Warner K., Afifi T., Henry K., Rawe T., Smith C., Sherbinin A de. Where the rain falls : climate change, food and livelihood security, and migration [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://ciesin.columbia.edu/documents/where-the-fall-falls.pdf.

- Mizutori M. Time to say goodbye to “natural” disasters [Internet]. Prevention Web. 2020. Available from: https://www.preventionweb.net/experts/oped/view/72768.

- Levy B.S., Patz J.A. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Ann. Glob. Health. 2015;81(3):310. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel G.J., Brottrager M., Crespo Cuaresma J., Muttarak R. Climate, conflict and forced migration. Glob. Environ. Change. 2019;54 Jan 239–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zickgraf Keeping people in place: political factors of (im)mobility and climate change. Soc. Sci. 2019;8(8):228. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick B., Schanze J. Trapped or voluntary? Non-migration despite climate risks. Sustainability. 2020;12(11):4718. [Google Scholar]

- Veronica Cornacchione. COP26 - Direct linkages between climate change, health and migration must be tackled urgently – IOM, WHO, Lancet Migration. 2021 Nov 9; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-11-2021-cop26-direct-linkages-between-climate-change-health-and-migration-must-be-tackled-urgently-iom-who-lancet-migration.

- Eichner M., Brockmann S.O. Polio emergence in Syria and Israel endangers Europe. The Lancet. 2013;382(9907):1777. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.S., Osei-Kofi A., Omar A., Kirkbride H., Kessel A., Abbara A., et al. Pathogens, prejudice, and politics: the role of the global health community in the European refugee crisis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16(8):e173–e177. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael C. Human mobility, climate change, and health: unpacking the connections. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- U.S. Global Change Research Program (2009-). The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: a scientific assessment. 2016. 25–42 p.

- McMichael C. Climate change-related migration and infectious disease. Virulence. 2015;6(6):548–553. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2015.1021539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg A.L., Frumkin H., Hess J.J., Ebi K.L. Managed retreat as a strategy for climate change adaptation in small communities: public health implications. Clim. Change. 2019;153(1–2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Michielin P., Di Giorgi E., Michielin D. Perception of climate change, loss of social capital and mental health in two groups of migrants from African countries. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanita. 2020;56(2):150–156. doi: 10.4415/ANN_20_02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J.M., Casey J.A. The centrality of social ties to climate migration and mental health. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):600. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4508-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva; 2007 doi: 10.1080/09540261.2022.2147420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhy S., Sarkar S., Panigrahi M., Paul S. Mental health effects of climate change. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015;19(1):3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.156997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. 73/195. Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration [Internet]. 2019 Jan. Report No.: Seventy-third session Agenda items 14 and 119. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/195.

- UNHCR. ‘Refugees’ and ‘Migrants’ – Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) [Internet]. UNHCR. 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/latest/2016/3/56e95c676/refugees-migrants-frequently-asked-questions-faqs.html.

- OHCHR. Historic UN Human Rights case opens door to climate change asylum claims [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25482&LangID=E.

- Farmer P.Paul Farmer: Economic Migration and Loss of Access to Medication [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.edx.org/course/the-health-effects-of-climate-change.

- IOM. E-PHR [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://www.re-health.eea.iom.int/e-phr.

- Zenner D., Wickramage K. National preparedness and response plans for COVID-19 and other diseases: why migrants should be included [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/blog/national-preparedness-and-response-plans-covid-19-and-other-diseases-why-migrants-should-be.

- Greenaway C., Castelli F. Infectious diseases at different stages of migration: an expert review. J. Travel Med. 2019;26(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taz007. https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/doi/10.1093/jtm/taz007/5307656 Feb 1 [cited 2020 Jul 14]. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeletti S., Ceccarelli G., Bazzardi R., Fogolari M., Vita S., Antonelli F., et al. Migrants rescued on the Mediterranean Sea route: nutritional, psychological status and infectious disease control. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020;14(05):454–462. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mipatrini D., Stefanelli P., Severoni S., Rezza G. Vaccinations in migrants and refugees: a challenge for European health systems. A systematic review of current scientific evidence. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2017;111(2):59–68. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2017.1281374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartovic J., Datta S.S., Severoni S., D'Anna V. Ensuring equitable access to vaccines for refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021;99(1) doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.267690. Jan 13-3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge H.H.P., Jakab Z., Bartovic J., D'Anna V., Severoni S. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet. 2020 Mar;S0140673620307911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.