Abstract

Mobility patterns in South Asia are complex, defined by temporary and circular migration of low waged labourers within and across national borders. They move, live and work in conditions that expose them to numerous hazards and health risks that result in chronic ailments and physical and mental health problems. Yet, public policies and discourses either ignore migrants’ health needs or tend to pathologise them, framing them as carriers of diseases. Their structural neglect was exposed by the ongoing pandemic crisis. In this paper, we take stock of the evidence on the health of low-wage migrants in South Asia and examine how their health is linked to their social, political and work lives. The paper derives from a larger body of work on migration and health in South Asia and draws specifically on content analysis and scoping review of literature retrieved through Scopus from 2000 to 2021 on health of low-income migrants. Utilising the lens of precarity and building on previous applications, we identify four dimensions of precarity and examine how these influence health: i) Work-based, concerned with hazardous and disempowering work conditions, ii) Social position-based, pertaining to the social stratification and intersecting oppressions faced by migrants, iii) Status-based, derived from vulnerabilities arising from the mobile and transient nature of their lives and livelihoods, and iv) Governmentality-based, relating to the formal policies and informal procedures of governance that disenfranchise migrants. We illustrate how these collectively produce distinct yet interrelated and interlocking oppressive states of insecurity, disempowerment, dispossession, exclusion, and disposability that define health outcomes, health-seeking pathways, and lock migrants in a continuing cycle of precarity, impoverishment and ill-health.

Keywords: Precarity, Migration, Health, South Asia, Intersectionality, Covid-19, Pandemic

Introduction

COVID-19 unfolded a humanitarian tragedy globally, placing a disproportionate burden on mobile populations. The effect of the pandemic was particularly stark in resource-poor contexts in South Asia, where the ban on movement within countries, closure of inter-state and international borders and suspension of transport at short notice left millions stranded and starving (Kapilashrami et al., 2020a; Shome, 2021). The adverse socio-economic and health impacts of the pandemic on low-waged migrants is now well documented (Kapilashrami et al., 2020a; Shome, 2021; Ahamded, 2020; John and Kapilashrami, 2020; Sharma et al., 2021; Samaddhar, 2020). However, in the absence of social security and presence of coercive public health measures, migrants at once became “subjects of charity, objects of (mis)governance and bodies of disease and stigma” [(Ahamded, 2020), p.124].

The framing of migrants as disease-carriers is not new. Pathologising migrants has been central to public policy discourses (e.g. as high-risk and bridge populations identified as target groups for HIV/AIDS and TB interventions), migration health scholarship (with disproportionate focus on infectious diseases) as well as media discourses (John and Kapilashrami, 2020). To this end, the pandemic merely intensified existing stereotypes of migrants as vectors, reducing them to biological bodies bereft of human meaning. However, the pandemic was distinctive in turning the public gaze to the precarity in migrants’ daily lives in South Asian countries (Kapilashrami et al., 2020a; Shome, 2021; Ahamded, 2020; John and Kapilashrami, 2020; Sharma et al., 2021; Samaddhar, 2020).

Judith Butler explains precarity as denoting a “politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks of support and become differentially exposed to injury, violence and death” [(Butler, 2009), p.25]. While the concept of precarity has received growing attention in recent decades, its relationship with health and application to identify the pathways through which states of ill health are produced is an unchartered terrain. Further, the concept has been historically studied in relation to insecure labour conditions and relationships, and the accompanying “social positioning of insecurity and hierarchization” [(Puar, 2012), p.165] these create. This focus on labour conditions, and thereby the migrant ‘labour’ or ‘worker’ overlooks the dimensions of precarity associated with the socio-economic, cultural and political lives of migrants (e.g. their interface with or exclusion from public health and other systems, policy and programmes, everyday violence outside their workspace including abuse from public authorities or local residents).

This paper addresses these gaps in the context of the complex patterns of mobility that South Asia characterises. Specifically, we take stock of the regional evidence on the health of low-wage migrants in South Asia and their underlying determinants, in the process identifying how these relate to the different aspects of precariousness and marginality that defines the economic, political and social lives of low-income migrants.

South Asia has a long history of rural-urban migration and forced displacement from conflicts, persecution, disasters and the failures of neoliberal economic development projects. In 2019 alone, the region reported 498,000 new Internally Displaced Populations (IDP) fleeing conflicts and violence (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2020). The region also hosts one of the highest refugee populations in the world. Mobility patterns in South Asia are however defined primarily by temporary migration of low-wage, low-skilled migrant labourers within national borders (inter-state as well as rural-urban intra-state) and circular migration across borders in the region, brokered by middlemen and recruitment agencies (World Bank, 2020). South Asian economies benefit extensively from migrants’ labour. Around 10% of India's Gross domestic product (GDP) comes from an estimated 100 million-strong internal migrant workforce (Deshingkar, 2020), who form the backbone of various sectors, including construction, domestic work, agriculture, garment, mining, amongst others. South Asians, who constitute the largest expatriate population in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, also contribute significantly to their home economies through remittances – in Nepal, this constitutes 30% of the country's GDP, while in Pakistan and Bangladesh, these figures stand at 7.9% and 5.8% respectively (World Bank, 2020). In spite of their contribution, low-wage migrant workers in South Asia frequently find themselves caught in a cycle of precarity that spans contexts of destination and origin; both characterised by poverty, informality and insecurity of work (John and Kapilashrami, 2020; Piper et al., 2017).

Method

This study is part of a larger body of work undertaken to examine the volume, scope, nature and trends in migration health research in South Asia undertaken by the research team of the Migration Health South Asia (MiHSA) network. Following a joint workshop on bibliometric analysis organised by MiHSA, MHADRI network and UN-IOM in Manila with a group of international and regional migration health experts, a bibliometric analysis was conducted focusing on migrants within the South Asia region and in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which hosts 15 million migrants from South Asia. This bibliometric analysis utilised the Scopus database to identify all studies examining migrants’ health from 2000 up to 2020, with a total of 1335 results. The research team retrieved the documents using the search words “health”, “wellness” and “well-being” along with several migrant categories (“stateless people” OR “refugee” OR “asylum” OR “international student”) and geographical location (“Afghanistan” OR “Bangladesh” OR “India” OR “Nepal” OR “Pakistan” OR “Sri Lanka” OR “Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)” OR “Kuwait” OR “U.A.E” OR “Bahrain” OR “Singapore”). The methodology and findings on the bibliometric analysis are detailed in a forthcoming paper from the research team.

For the purpose of this study, we excluded studies on international students, migration of healthcare workers, non-South Asian immigrants in the region, South Asian emigrants in countries outside the geographical locations mentioned above, literature not directly linked to migrants’ health and well-being (for example, studies on migration and medical tourism, climate-related migration patterns, impact of migration on resources, migrant economy and improved tools and instruments for conducting research on migrants). After applying the exclusion criteria, 486 articles were found relevant. We extended the scope of the review by undertaking a further search and review of literature in 2020- 2021 using the same search words on Scopus used in the bibliometric analysis. We had 76 retrievals, with a majority of this literature focused on the impact of COVID-19 on the health, well-being and healthcare access of migrants. We excluded 37 studies as they didn't meet our inclusion criteria, leaving in total 523 papers for inclusion.

In the retrieved papers, we undertook content analysis to identify key health domains covered, and conducted a scoping review (Munn and Stern, 2018) of a sub-set of literature on healthcare access and social determinants of health. In synthesising this body of evidence, we identified four broad and overlapping themes related to work, social inequities and structural conditions, migrant status, and governmentality, which we use to refer to restrictive laws or poor implementation of existing legislative measures to protect migrants. These themes build on earlier frameworks on precarity, which we adapt and extend for the purpose of this article. For instance, Verna Viajar (Viajar, 2017), in her study of migrant domestic workers in Malaysia, explores three dimensions of precarity – the devaluation of their work (work-based precarity) which reproduces the productive-reproductive and formal-informal labour dichotomies; deportability of migrants (status-based precarity); and the specific political economic context of Malaysia, including non-recognition of domestic work that prevents workers from enjoying labour rights (national-based precarity).

We extend this analysis to examine precarity not only in relation to labour conditions, but also with respect to the wider social and economic lives of migrants and refugees in South Asia, and their health. Using the lens of precarity, we examine the health status and healthcare access of low-income migrants, including IDP and refugees in the region.

Findings

Five health domains were identified in the literature retrieved. Infectious diseases represented the largest proportion of studies (n = 137/523) followed by psychosocial and mental health (n = 117/523), non-communicable diseases (n = 106/523), maternal and reproductive health (n = 92/523), and access to healthcare and wider determinants (n = 71/523)). For the purpose of this paper, we further examined the evidence on the determinants (and pathways) of poor healthcare access and outcomes. Of the 71 articles, we excluded five as they were either reflections from the field or were not specific to migrants’ health status or access to healthcare. In total, we reviewed 66 articles – of this a majority were primary research (n = 44/66), followed by systematic or scoping reviews (n = 12/66) and commentaries (n = 10/66) especially on the impact of covid-19.

Most of the studies were situated in India (n = 41/66) (See Table 1.1), followed by Bangladesh (n = 9/66), and GCC countries (n = 4/66), which see a high footfall of migrants from South Asia. Three of the studies covered multiple countries within the region or had at least one of the study sites based in South Asia. A majority (70%) of the scholarship was on internal migrants, with 46 of the 66 papers focused on this group. While analysing this body of evidence, we identified four broad and overlapping themes related to: work (n = 27), social inequities experienced by migrants (24), migrant status (19), and governmentality (9), which we use to refer to restrictive laws or poor implementation of existing legislative measures to protect migrants.

Table 1.1.

| Total studies reviewed | 66 |

|---|---|

| Type of Article | |

| Primary research (Quantitative & Qualitative) | 44 |

| Reviews | 12 |

| Commentary including on impacts of covid-19 | 10 |

| Study Location | |

| India | 41 |

| Bangladesh | 9 |

| GCC (U.A.E, Qatar) | 4 |

| Pakistan | 3 |

| Nepal | 4 |

| Sri Lanka | 2 |

| Multiple countries | 3 |

| Migrant Categories | |

| Internal labour migrants | 46 |

| Cross-border migrants | 13 |

| Refugees | 9 |

We now describe these themes, their characteristics, and the evidence on their influence on migrants health.

Work-based precarity and migrants’ health

The nature of work, terms of employment and contractual relations, and associated conditions emerged as a prominent determinant of migrants’ health. Low-income migrants in South Asia inhabit the large informal economy that accounts for nearly 80% of total employment in the region (International Labour Organisation, 2018). The informal sector comprises a diversified set of economic activities and jobs – construction, scavenging, factory work on piece rates, vending, domestic work - that remain unregulated and thereby associated with sub-optimal and often hazardous conditions of work, including, for instance, protracted exposure to wastes (Malik et al., 2020; Masood et al., 2014), and poor safety standards and security. Migrants’ work is thus often marked by uncertainty, restrictive conditions, poor remuneration leading to increased exploitation and insecurity of the migrant workforce as well as poor protection and dignity at work. (Piper et al., 2017; Saraswati et al., 2016)

Association of migrants’ health with their work environment is the most common theme in the literature. Studies report a high prevalence of undiagnosed chronic diseases caused or aggravated by the nature of work migrants perform (Solinap et al., 2019) and their exposure to harsh climatic and hazardous conditions. Pradhan et al. (Pradhan et al., 2019) found a strong correlation between heat stress and cardiac mortality amongst Nepali migrants in the Gulf States. Studies examining health of migrant workers in the construction sector in India (Adsul et al., 2011), the garment sectors in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka (Solinap et al., 2019; Senarath et al., 2016) and manual scavenging in Pakistan (Malik et al., 2020) report that a majority develop respiratory problems, gastro-intestinal illnesses, kidney and liver (e.g. jaundice) ailments and musculo-skeletal problems from repetitive strains and heavy lifting, and routinely suffer from falls and accidents (Schenker, 2010). Authors attribute these effects to dangerous working conditions, toxic wastes handled, and poor safety standards observed by employers. A 2018 survey of repeat internal migrants in India reported 83% worked in dusty, smoke-filled rooms with inadequate ventilation, 42% worked without safety gear, and a quarter were in contact with potentially infectious and dangerous materials daily. Injuries and illness from unprotected work may result in long-term disabilities, which may in turn force the children of these workers into entering similarly hazardous work (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2018). Most of these workers enter the job market at a very early age, experience no upward mobility and remain stuck in hazardous jobs for their entire work-life span (Samaddhar, 2020). Another study (Hameed et al., 2013) amongst internal migrants in India found that those with a history of migration had double the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and cardiac complaints compared to those with no history of migration. Here, employment-related stressors were identified as key risk factor. Similar heightened risks are reported by studies on infectious diseases (e.g. HIV infection) amongst migrants; with some estimates indicating HIV prevalence being three times higher amongst male migrants than the general population (Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), 2015). Scholars associate these risks with the condition and structure of the migration process, which involve type of occupation and work that influenced mobility pattern, sexual structure, and power relationship (Chowdhury et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Poor health also results from exploitative terms and conditions of employment, such as longer work hours without break, repetitive tasks, difficult sustained postures, inability to change one's place of work or to take leave. Studies on the work conditions of Nepali migrants in the Gulf States note that working long hours in the sun were significantly associated with dehydration and heat stroke (Simkhada et al., 2018; Pradhan et al., 2019). Women migrant workers in Bangladesh's garment sector suffer from anxiety, stress, restlessness and thoughts of suicide due to the work burden, exacerbated by separation from their children and family support (Akhter et al., 2017). All three studies found that migrant workers’ access to healthcare is limited by their long work hours and limited medical services provided at the workplace. Absence of contracts, which is common practice in the unorganized sector, also limits access to employee benefits such as healthcare or sick leave (Bhattacharyya and Korinek, 2007). Precarious work often goes hand in hand with intermittent access to basic services (Babu et al., 2017), widespread discrimination and ill-treatment (Sharma et al., 2021; Samaddhar, 2020; Acharya, 2021), combined with an inability to demand rights and justice (e.g. compensation for accidents); all contributing to poorer health outcomes (Kusuma and Babu, 2018).

Migrants’ intersectional identities and social determinants

Diverse aspects of migrants’ social location also influence their mobility, work as well as other social determinants of health and healthcare access (Kapilashrami and Hankivsky, 2018). Social stratification based on caste, tribal/ indigenous status and gender were most conspicuous in the literature and linked to the exploitative labour migration system in South Asia predicting distinct health outcomes.

In India, tribal status was found to be strongly related to poor nutritional outcomes (Mohan et al., 2016), and being a tribal from a high outmigration area heightening vulnerabilities faced by these families. Another study of internal seasonal migrants in three Indian states (Shah and Lerche, 2020) found schedule castes (Dalits) and tribal (Adviasis) migrant workers from central and eastern India to be the most vulnerable and exploited of the migrant workforce; engaging in work that local populations, including most marginalised caste groups, were moving away from. The study reports a high incidence of malaria amongst these workers, high reliance on shamans (religious or spiritual figures who function as healers in many indigenous faiths) and quacks for treatment and medication, and high debts incurred from taking loans from contractors to meet their medical expenses. Healthcare expenditure was also reported as leaving them poorer and without sustenance money. Authors found a qualitative difference between the working and living conditions of Adivasis and Dalits and that of other backward castes and Muslims; the former relying exclusively on irregular income from piecemeal daily wages.

Only one study examined nationality and citizenship-based differences in health vulnerabilities by contrasting Nepali and Bangladeshi migrants in India and the health status of return migrants in these countries (Saraswati et al., 2016). Authors found a higher burden of psychological distress, hypertension, and moderate to severe anaemia in Bangladeshi migrants than the Nepali migrants, and less likelihood of their accessing public health facilities. A range of factors including more open migration corridors between India and Nepal, relatively better socio-economic position of Nepali migrants were identified as potential explanations.

Gender emerged as another critical factor shaping patterns of mobility, work and the resulting differences in health risks and vulnerabilities. Mazumdar et al. (Mazumdar et al., 2013) found a distinctive gendered pattern in labour migration across India – most women migrants were concentrated in the paid domestic and garment sectors, and male migrants dominated services and industries. While this increased men's exposure to accidents and injuries from heavy machinery work, women migrants faced a double burden of occupational hazards and gender-based discrimination (including wage differences, sexual harassment, and lack of privacy for sanitation) (Tiwary and Gangopadhyay, 2011). Refugee status heightened these vulnerabilities especially in the context of deteriorating protection environment. Research on Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar found that women and girls were at high risk of multi-dimensional sexual and gender-based violence at the household and community level; risk that was exacerbated by displacement (UNHCR, 2020). Trans people in this community faced additional risks, social exclusion and discrimination based on their gender, which impeded their access to even basic healthcare services.

It is noteworthy though that most migrant women workers in India who are concentrated in short-term and circular migration, generally involving hard labour, come from historically and socially disadvantaged communities of Adivasis and Dalits (Mazumdar et al., 2013; Nimble and Chinnasamy, 2020). Studies show that women in these sectors are more prone to multiple occupation health hazards, harassment, and poor maternal and mental health (Bhattacharyya and Korinek, 2007; Kusuma and Babu, 2018; Jatrana and Sangwan, 2004).

‘Migrant’ status-based precarity and health

The vulnerabilities arising from the transient and temporary status associated with being a migrant are regarded as influencing migrants’ health. Literature suggests this influence may be constituted via two pathways- direct and indirect. First, displacement and mobility to new cities can itself cause significant psychological stress, which is aggravated by the insecure and exploitative nature of their livelihoods. Their ‘outsider’ status in a locality exposes them to widespread abuse and ill-treatment from local residents, landlords, and authorities, that “rarely ends with compensation and justice” (Sharma et al., 2021). This stress is shown to manifest as substance abuse, domestic violence, and poor mental and physical health (National AIDS Control Organisation, 2019; Borhade, 2011; Mander and Sahgal, 2008). While these vulnerabilities are common to other marginalised groups (e.g. urban poor), the precarity linked to mobility and migrant status produces excess burden on health. A cross-sectional survey in a slum in New Delhi found that 80% migrants showed indications of poor psycho-social health compared to 45% long-term residents in the same setting (Virupaksha et al., 2014). Most of these migrants were single, male temporary workers, experiencing poor living and work conditions, loneliness, and ‘othering’ by local residents. Legal and social marginalisation based on citizenship / nationality was reported in few studies focused on select refugee populations (for e.g. Rohingyas in Bangladesh (Chynoweth et al., 2020), Chin and Burmese refugees in India (Parmar et al., 2014; Jops et al., 2016)). All studies report higher neglect, abuse and poorer access and financial barriers to utilising healthcare resulting from a lack of comprehensive protection and recognition systems (Roy and Mir, 2020).

Second, their temporariness and the ‘outsider’ status in a locality yields poor awareness of their entitlements (healthcare, education and other welfare schemes) and the location of healthcare facilities, which combined with a lack of documentation is associated with poor utilisation of healthcare and poor outcomes (Babu et al., 2017; Borhade, 2011; Siddaiah et al., 2018). For instance, studies on immunization patterns amongst children of rural–urban migrants in India reveal that a large proportion of children, particularly those in recently migrated and temporary migrant families, did not receive the full course of immunization (Kusuma et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2020). Researchers attribute the higher than national average rates of partial/non-immunization to the isolation migrant families face in their new sociocultural environment as well as the under-served work sites such as brick-kilns (in terms of vaccination centres) and poor levels of literacy and awareness. Poor healthcare access also results from non-portability of entitlements (such as health insurance). In a study on maternal healthcare access amongst migrant women workers in brick-kilns in Haryana, India, Siddaiah et al. (2018) report only one third had ever received cash benefit under Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) or used free ambulance service (Siddaiah et al., 2018). Adhikary et al. (Adhikary et al., 2020) found Nepali migrants in India, most of whom work as daily-wage labourers, being denied access to healthcare services without an Aadhaar card (an Indian identification card linked to individual biometrics). Even internal migrants in India often refer to their destination states as ‘foreign’ (Rogaly et al., 2002), and they struggle to access elementary citizenship rights like the right to vote and welfare measures (Sharma et al., 2021).

Another characteristic associated with the temporariness of their livelihood and sociability is the treatment of migrant bodies as carriers of infections (John and Kapilashrami, 2020; Samaddhar, 2020), and thereby a threat to local populations’ health. This justifies their subjection to coercive public health measures. Scholarship from the region during covid-19 report selective quarantining measures, public health surveillance and state actions to disinfect migrants, ostracising and vigilantism of return migrants (Shanker and Raghavan, 2020; Jha and Lahiri, 2020; Adhikary et al., 2020), as well as deportations following routine screenings for other infectious diseases (Samaddhar, 2020). In the case of cross-border labour migrants, this is also shown to disrupt care pathways. In the context of GCC countries, scholars report migrants being subjected to compulsory periodic medical examinations and risk deportation without diagnosis and treatment, if found to be HIV positive (Wickramage and Mosca, 2014).

Migration governmentality and health

Migration governmentality, the multi-layered, heterogeneous set of formal and informal institutions, procedures, policies, actions and discourses through which migration (and migrants) are governed, reinforces migrants’ precarity and implicates their health. Three key dimensions of governmentality was evidenced in the literature.

First, the systematic neglect and invisibility of migrants were exposed during the state-imposed lockdown following the COVID-19 pandemic in various countries in South Asia. In India, closure of work sites and eviction forced 10.4 million domestic migrant workers to return to their home states (Down To Earth, 2020a), by undertaking weeks-long journeys on foot, with no provision for their food, shelter and health (Samaddhar, 2020). By early May 2020, 30% of families in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh engaged in tourism, construction, and service sectors, which employ millions of migrant workers, had lost their income (UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, 2021). Job losses, restrictions on movement and long work hours without wages were common across countries in the region. The closure of the Nepal-India border left workers returning to Nepal stranded in crowded temporary shelters at the border (Down To Earth, 2020). Evidence and media reports suggest increased deaths and burden of infection, as well as high levels of stigmatisation that led to significant physical and mental health impacts (Samaddhar, 2020; Shanker and Raghavan, 2020; Jha and Lahiri, 2020). Yet, most countries were unable to trace the number of migrants affected, or target relief measures to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on their lives and livelihoods. States failed to consider the disruption in migration patterns induced by the pandemic, which increased the risk of concentrated outbreaks in areas of return, a majority of which were ill-equipped to offer even general care (Kapilashrami et al., 2020a). In Qatar, migrant workers from Nepal were deported under the pretence of Covid-19 testing after being detained in overcrowded quarters without adequate food or water (Budhathoki, 2020).

Where introduced, mitigation measures failed to reach low-income migrants. For instance, foreign workers were excluded from the financial relief introduced by GCC states to businesses to maintain workers’ salaries and jobs and from overall Covid-19 policy responses (UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, 2021). Such systemic neglect of migrants’ needs in pandemic policies was also revealed in an assessment of the influenza preparedness plans in 21 countries in the Asia Pacific region, (Wickramage et al., 2018) with only three countries (Thailand, Papua New Guinea, and the Maldives) including at least one migrant group in their respective national plans. Likewise, where legislative measures to protect migrants exist, these are poorly enforced. A case in point is the Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) Act 1996 and the Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act 2008 in India, which provide social security benefits to migrant workers for work-related injuries, sicknesses, maternity, and pension for those above 60 years (Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India, 2018). In addition, the Workmen Compensation Act of 1923 provides a list of diseases which, if contracted by the employee, will be considered an occupational disease liable for compensation (NCEUS, 2007). However, a survey of migrant workers (Aajeevika Bureau, 2014) across three employment sectors in Rajasthan found that the majority were unable to avail full benefits as they were not on payroll i.e. not registered by contractors or employers. During Covid-19, this meant that, albeit delayed, the furlough schemes and benefits that were offered to factory workers failed to reach labour migrants who suffered job losses. Contractors and employers refuse liability for deaths, lay-off in case of accidents, and either not compensate or deduct medical compensation and treatment expenditures from workers’ wages (Sharma et al., 2021; Samaddhar, 2020; Prayas, 2009).

Second, precarity is also constituted by the relegation of responsibility by the State, and outsourcing/ privatising migration management. A case in point is the ‘Kafala’ system in the GCC States, where a migrant's employment, wage and immigration (legal) status are tied to a single sponsor or employer to whom the State has relegated this responsibility. This forces the international migrant labourers into an exploitative relationship and cycle of dependency with the employer that is difficult to break (Fernandez, 2021). Viajar (2017) examines this relationship in the context of the guest worker program in Malaysia, wherein any confrontation with or act of reporting an abusive employer can be viewed as a breach of contract and lead to the cancellation of work permits making workers liable to deportation. The fear of losing their job and legal status refrains migrants from seeking recourse. Berg (2016) describes the process as engineering the fear to be “detected, detained and deported”, thereby ensuring they do not complain, protest or mobilise. Such relegation is also evident in the case of refugee and asylum seeking management in India, which is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol; nor has a national asylum framework. In the absence of formal laws and frameworks, over 200,000 refugee groups that reside in India are dealt with on ‘ad-hoc and arbitrary’ basis. Few studies that focused on refugee settlements in India show how this results in different documents, differential treatment and heightned insecurity (Parmar et al., 2014; Jops et al., 2016; Roy and Mir, 2020; Shanker and Raghavan, 2020). Living and labouring in such precarious conditions comes with increased exposure to a gamut of labour rights violations and accompanying health risks (Piper and Segrave, 2015).

Finally, restrictive (and gender-blind) immigration regimes, changing citizenship policies and surveillance systems also yield the systematic production of migrants as “outcastes” (Banki, 2013) and undermine migrants’ sexual and reproductive health rights (Lee and Piper, 2017). Restrictions applied by the Sri Lankan government on women migrating for domestic work and introducing additional approvals/ endorsements from husband, government officials and employment agents not only discriminate but also push women migrants into irregular and dangerous migration routes and exploitative arrangements (Henderson, 2020). Regressive immigration and citizenship laws instil fear of violence, detention and deportation, which directly affect utilisation of services. This was evidenced in the case of Assam, a state in the North-Eastern region of India where the National Registration of Citizenship process that coincided with the pandemic rendered 1.9 million people stateless and ‘illegal’. Scholars highlight how detention of these groups resulted in adverse health consequences including severe trauma, suicides, and deaths (Kapilashrami et al., 2020; Zachariah and Jesani, 2020).

Discussion

Migration as a social and structural determinant of health is well established. However, the complex pathways through which migration impacts migrants’ mental and physical health and wellbeing is less understood. Much less attention is given to how the states of health and well-being are linked to migrants’ social, economic, and political lives and the precarity that defines these.

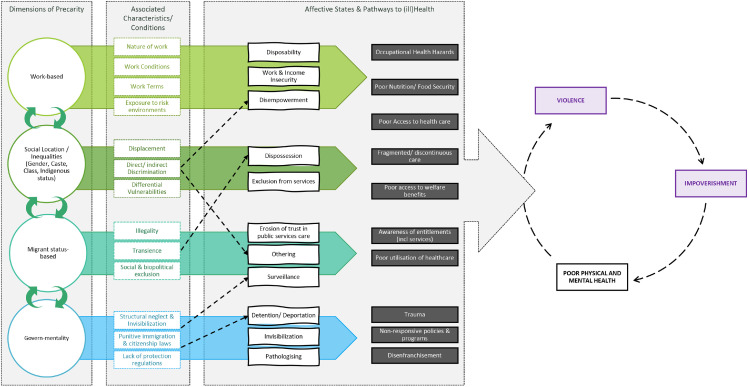

Our review of literature on the health of low waged migrants and factors and processes that determine states of health (i.e. the processes of determination) revealed four distinct dimensions of precarity and associated conditions that produce ill-health. These, we argue, produce distinct yet inter-related and interlocking oppressive states of insecurity, disempowerment, dispossession, neglect, exclusion, othering, and disposability, locking migrants in a continuing cycle of impoverishment and ill-health. These dimensions, their characteristics, and pathways of health determination are illustrated in the figure below Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Framework on precarity and ill-health amongst low-waged migrants.

Examining work-based precarity, we reveal how restrictive contracts and terms of employment, poor wages and work conditions create insecurity and disempowered states of being. Their disempowered state precludes them from being able to negotiate safer workspaces leaving them exposed to different health risks and occupational hazards, and abuse without compensation or recourse to justice. Besides growing evidence on health risks associated with informal and hazardous work (and work environments) migrants engage in, the exploitative and restrictive environment created by the neoliberal Market-State complex actively functions to dispossess them of their social-economic rights. Ferguson and McNally (Ferguson and McNally, 2014) view this as a deliberate strategy to keep them vulnerable and controllable as they become “cheap labour” and thereby profitable. Their insecure legal and residential status further limit their capacity to negotiate secure employment or demand better wages and safer workspaces. Consequently, migrants remain stuck in precarious jobs for their entire work-life span putting them at risk of poor health, and unaffordable healthcare.

A second dimension of precarity we identify in this review is migrants’ exclusion from services and policies based on the interaction of diverse aspects of their social position that are unique to low-waged migrants in South Asia. These aspects reflect economic and social inequalities in society that shape risk environments and health vulnerabilities. Evidence establishes the heterogeneity amongst migrants in South Asia, and, where examined, the gendered and racialised differences in determination of health. A few studies indicate that migrants’ experience of insecurity, dispossession and ill-health is mediated by gender, minority caste, ethnic and indigenous status. Caste and indigeneity-based inequalities that structure migrants socio-economic lives are underpinned by uneven development, marked by a history of neoliberal domination and subjection, a process Shah & Lerche (Shah and Lerche, 2020) describe as “internal colonialism”. These factors interact to create and reinforce a rigid social hierarchy on the basis of which some migrant groups cluster in low-dignity and insecure work and face greater ‘othering’ and exclusion. Social and biopolitical exclusion often translates into adverse living and working conditions, poverty, the perpetual fear of state violence resulting in chronic stress and heightened vulnerability to illness and injuries. Systematic and prolonged exclusion also results in an erosion of trust in public services (including health) resulting in lower uptake of preventive interventions such as immunisation, and avoidance of healthcare (Kusuma et al., 2010). Yet, research and policy have tended to study risks and vulnerabilities under distinct administrative and legal labels (e.g. migrant labour, IDP, climate refugees, asylum-seekers). Kapilashrami and Hankivsky (Kapilashrami and Hankivsky, 2018) remind us that these identity groups are not homogenous with uniform health and healthcare seeking experiences and framing them as such masks differential risks and precarities resulting from migrants’ unique social position at different stages of their journeys.

Attention to these social divisions and structural conditions gains particular salience in South Asia, where patterns of labour migration are often steered by gender and class relations defined by rigid social hierarchies of caste, ethnicity and tribe (indigeneity), which impact the health and wellbeing of migrants and their families (Samaddhar, 2020). Studying this multi-dimensional socioeconomic ordering and the interactions of these structural positions demands an explicit adoption of intersectionality lens as it can provide valuable insights into how different axes of power intersect with each other to place migrants in different situations of discrimination and disadvantage as well as leverage, potentially guiding more targeted and effective health policies (Kapilashrami and Hankivsky, 2018).

The third dimension unpacks the vulnerabilities arising from the trans-locality associated with being a ‘migrant’. The transient nature of migrants’ social and economic lives resulting from the neoliberal restructuring of global and domestic labour markets, renders them in a constant state of circulation between villages and cities, neither of which provide the necessary livelihoods and conditions for them to settle (de Haan, 2020). Further, their status as ‘non-citizens’ (Ferguson and McNally, 2014), or ‘lesser’ or ‘inferior’ citizens in the case of internal migrants whose constitutional rights are often violated (or not protected) by States, predicates their ‘hyper-precarity’ and reinforces their disposability. This disposability not only directly affects their physical and mental health but erodes trust in public services, thereby adversely shaping their interaction with health systems and reducing their uptake of services (as evident with contraceptive and maternal healthcare).

The fourth dimension of precarity foregrounds institutional and systemic neglect and discrimination (direct and indirect) meted out to migrants through the various structures and process of migration governance. In unpacking this dimension, we go beyond Viajar's reference to the political-economy of the nation, and instead use ‘governmentality’ to examine the range of institutions and policies and changing state-citizenship relationship that affect health. Migration governance and associated precarity has been studied mostly in the context of undocumented migrants and with regards to border regimes. However, we demonstrate its salience to internal migrants, who on migrating are treated as de facto non‐citizens (Mander and Sahgal, 2008) or ‘lesser’ citizens, invisible to planners and policy makers in destination cities, or subjected to violations of their constitutional rights. On the one hand, active vilification from media and pathologizing in health interventions (as seen in the case of COVID-19) makes them particularly prone to abuse and subjects of invasive interventions. This was evident during the pandemic crisis which, as Samaddar (Samaddhar, 2020) observes, effectively transformed a labour migrant from a “productive body” generating capital for families and communities to a “body of disease”, justifying coercive public health surveillance and quarantine measures. On the other, invisibility in public policies (social protection and health) undermines their fundamental rights, further distancing them from, and eroding their trust in, public systems. Here, tenuous legal status, deteriorating protection environment and the failure to establish comprehensive rights-based migration policies creates the conditions for the systematic exploitation of migrants. A focus on governmentality thus allows capturing the paradox of systemic invisibility in public policy and planning and pathologized visibility in public health interventions as carriers of diseases. Analysis of these pathways also highlight the mutually constituting crises of development and governance that underpin the multiple systematic production of migrants’ precarity in the region and how it locks migrants in a vicious cycle of structural violence, impoverishment and poor states of health and well-being.

In summary, the conditions in which migrants move, live, and work carry exceptional risks to their physical and mental well-being (Zimmerman et al., 2011). While there's mounting scholarship on migration in South Asia, migrants’ health continues to be a relatively neglected area, in research and policy (Kapilashrami et al., 2020). Studies are concentrated on specific work sectors and occupational health of migrants, or on specific health risk environments (trafficking) and domains e.g. infectious diseases. Studies reporting on migrants’ health tend to be stripped off analysis of the socio-economic and political determinants and the pathways through which their health states are produced (i.e. determination of health). They are largely cross-sectional, assessing states of ill-health and violence, with limited attention to causal pathways. The lens of precarity and intersectionality can potentially help correct this bias. By reviewing evidence on migrants’ health, however limited, in this paper we address these gaps and contribute to a deeper understanding of the different dimensions of precarity characterising migrants’ lives, and how those in turn affect healthcare entitlements and well-being of migrants and refugees in South Asia. The four interacting dimensions of precarity and associated conditions generate several distal and proximal determinants, which result in poor health access, experiences and outcomes.

The study's distinctive contribution to the field of migration health are limited by the scope of the review conducted, and limitations in data. We adopted a content and scoping review of literature in an emergent field of scholarship. Global and regional bibliometric analysis of the field have established the limited empirical work that has examined migrants’ health, especially in the region (Sweileh et al., 2018). We were thus constrained by the limite evidence. A further limitation is our focus on literature published in peer reviewed journals (on Scopus) and in English, with particular attention to terminologies used in ‘migration health’ field. Elsewhere, we reflect on the body of literature this may exclude as studies with migrant populations have in the past not explicitly used the term ‘migrant’ but study these populations in other contexts such as specific labour sectors (e.g. domestic work, factory workers) or as urban poor in slum and other residential sites (Kapilashrami et al., 2020b). A further limitation is linked to the methodology, which excludes grey literature and rapid empirical studies conducted by civil societies and other local institutions during the pandemic. Finally, the framework derived from the findings is limited by the cross-sectional study designs, and their focus on risk factors and vulnerabilities (not on agency and resilience, nor on explanations of causal pathways). The framework is therefore largely conceptual and requires further studies to test and explicitly examine causal pathways to health outcomes.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aajeevika Bureau. Their own country: a profile of labour migration from Rajasthan, 2014. http://www.aajeevika.org/assets/pdfs/Their%20Own%20Country.pd.

- Acharya A.K. Caste-based migration and exposure to abuse and exploitation: dadan labour migration in India. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2021;16(3):371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary P., Aryal N., Dhungana R.R., et al. Accessing health services in India: experiences of seasonal migrants returning to Nepal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020:992. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05846-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adsul B.B., Laad P.S., Howal P., R.M Chaturvedi. Health problems among migrant construction workers: a unique public-private partnership project. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011;15(1):29–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.83001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamded S. In: Borders of an Epidemic – Covid-19 and Migrant Workers. Samaddhar R., editor. Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group; Calcutta: 2020. Epilogue: counting and Accounting for Those on the Long Walk Home; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter S., Rutherford S., Kumkum F.A., et al. Work, gender roles, and health: neglected mental health issues among female workers in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Int. J. Women's Health. 2017;9:571–579. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S137250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu B.V., Kusuma Y.S., Sivakami M., M et al. Living conditions of internal labour migrants: a nationwide study in 13 Indian cities. Int. J. Migrat. Border Stud. 2017;3(4) [Google Scholar]

- Banki S. Precarity of place: a complement to the growing precariat literature. Global Discourse. 2013;3(3–4):450–463. doi: 10.1080/23269995.2014.881139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg L. Routledge; 2016. Migrant Rights at Work: Law's Precariousness At the Intersections of Immigration and Labour. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S.K., Korinek K. Opportunities and vulnerabilities of female migrants in construction work in India. Asian Pacific Migrat. J. 2007;16(4):511–531. [Google Scholar]

- Borhade A. Health of internal labour migrants in India: some reflections on the current situation and way forward. Asia Europe J. 2011;8(4):457–460. [Google Scholar]

- Budhathoki, A. Middle East Autocrats Target South Asian Workers, Foreign Policy. April 23, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/23/middle-east-autocrats-south-asian-workers-nepal-qatar-coronavirus/.

- Butler J. Verso; London and New York: 2009. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury D., Saravanamurthy P.S., Chakrabartty A., Machhar U., Purohit S., Iyer S., Mishra P. Profile characteristics of migrants, especially occupation and HIV status, accessing targeted interventions in Mumbai and Thane in India. Int. J. HIV-Related Problems. 2018;17(3):189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury D., Saravanamurthy P.S., Chakrabartty A., Machhar U., Purohit S., Iyer S., Mishra P.K. Vulnerabilities and risks of HIV infection among migrants in the Thane district, India. Public Health. 2018;164:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chynoweth S.K., Buscher D., Martin S., et al. A social ecological approach to understanding service utilization barriers among male survivors of sexual violence in three refugee settings: a qualitative exploratory study. Confl Health. 2020;14(43) doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00288-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan A. Labour Migrants During the Pandemic: a comparative perspective. Indian J. Labour Econ. 2020;63(4) doi: 10.1007/s41027-020-00283-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshingkar, P. Why India's Migrants deserve a better deal, Mint. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-india-s-migrants-deserve-a-better-deal-11589818749274.html, 2020. (accessed 30 March 2021).

- Down To Earth, As told to Parliament: some 10.4 million jobless migrant workers returned home post-lockdown, September 14, 2020. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/economy/astold-to-parliament-september-14-2020-some-10-4-million-jobless-migrant-workers-returnedhome-post-lockdown-73363.

- Down To Earth, COVID-19: around 800 Nepali workers stranded in Dharchula, Uttarakhand, 2020 https://www.downtoearth.org.in/video/health/covid-19-around-800-nepaliworkers-stranded-in-dharchula-uttarakhand-70135.

- Ferguson S., McNally D. Precarious migrants: gender, race and the social reproduction of a global working class. Socialist Register. 2014;51(51) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez B. Racialised institutional humiliation through the Kafala. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021;47(19):4344–4361. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1876555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed S.S., Kutty V.R., Vijayakumar K., et al. Migration status and prevalence of chronic diseases in Kerala State, India. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2013;4(23):23–27. doi: 10.1155/2013/431818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S. State-sanctioned structural violence: women migrant domestic workers in the Philippines and Sri Lanka. Violence Against Women. 2020;26(12–13):1598–1615. doi: 10.1177/1077801219880969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). National AIDS Control Organization. India HIV Estimations. Technical Report, 2015. pp 17–35.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Global Report on Internal Displacement. https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2020-IDMCGRID.pdf , 2020. (accessed 30 March 2021).

- International Labour Organisation . Women and Men in the Informal economy: A statistical picture. 3rd ed. International Labour Office; Geneva: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jatrana S., Sangwan S.K. Living on site: health experiences of migrant female construction workers in North India. Asian Pacific Migrat. J. 2004;13(1):61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jha S.S., Lahiri A. Domestic migrant workers in India returning to their homes: emerging socioeconomic and health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rural Remote Health. 2020;20(4) doi: 10.22605/RRH6186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John E.A., Kapilashrami A. Victims, villains and the rare hero: analysis of migrant and refugee health portrayals in the Indian print media. Indian J. Med. Ethics. 2020:01–12. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2020.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jops P., Lenette C., Breckenridge J. A context of risk: uncovering the lived experiences of chin refugee women negotiating a livelihood in Delhi. Refuge. 2016;32(3) [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami A., Hankivsky O. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2589–2591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami A., Issac A., Sharma J., et al. Neglect of low-income migrants in Covid-19 response. BMJ. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami A., Wickramage K., Asgari-Jirhandeh N., Issac A., Borhade A., Gurung G., Sharma J.R. Vol. 9. WHOO South-East Asia J Public Health; 2020. pp. 107–110.http://www.who-seajph.org/text.asp?2020/9/2/107/294303 (Migration Health Research and Policy in South and South-East Asia: Mapping the Gaps and Advancing a Collaborative Agenda). Available online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Ranjan A., Kumar D., Pandey S., Singh C.M., Agarwal N. Factors associated with Immunisation coverage in children of migrant brick kiln workers in selected districts of Bihar, India. Indian J. Community Health. 2020;32(1):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma Y.S., Babu B.V. Migration and health: a systematic review on health and health care of internal migrants in India. Int. J. Health Plan. Manage. 2018;33(4):775–793. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma S., Kumari R., Pandav C.S. Migration and immunization: determinants of childhood immunization uptake among socioeconomically disadvantaged migrants in Delhi, India'. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2010;15(11):1326–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Piper N. Migrant domestic workers as ‘agents’ of development in Asia: an institutional analysis of temporality. Eur. J. East Asian Stud. 2017;16(2):220–247. doi: 10.2307/26572826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, The occupational health and safety of migrant workers in Odisha, India. Study on Work in Freedom Transnational (SWiFT) Evaluation. India briefing Note. No.3. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/files/swift-india-brief-no.3-occupationalhealth-and-safety-dec18.pdf, 2018 (accessed 30 March 2021).

- Malik B., Lyndon N., Chin Y. Health status and illness experiences of refugee scavengers in Pakistan. Sage Open. 2020;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- Mander H., Sahgal G. G, Internal Migration in India: distress and Opportunities. UNESCO Gender Youth and Migration; New Delhi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Masood M., Barlow C.Y., Wilson D.C. An assessment of the current municipal solid waste management system in Lahore, Pakistan. Waste Manage. Res. 2014;32(9):834–847. doi: 10.1177/0734242X14545373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar I., Neetha N., Agnihotri I. Migration and gender in India. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2013;10(54) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Law and Justice, Govt of India . Government of India; New Delhi: 2018. The Unorganised workers’ Social Security Act. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan P., Agarwal K., Jain P. Child malnutrition in rajasthan study of tribal migrant communities. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2016;51(3):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Stern M.D.J., et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organisation . NACO; New Delhi: 2019. NACP III To Halt and Reverse the HIV Epidemic in India; pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- NCEUS . Report On Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganized sector. Government of India; New Delhi: 2007. pp. 1–107. [Google Scholar]

- Nimble O.J., Chinnasamy A.V. Financial Distress and healthcare: a study of migrant dalit women domestic helpers in Bangalore, India. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2020;21:5. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss5/4/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar P., Aaronson E., Fischer M., O'Laughlin K.N. Burmese refugee experience accessing health care in New Delhi: a qualitative study. Refugee Survey Q. 2014;33(2):38–53. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdu006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piper N., Segrave M. Contemporary Forms of Forced Labour: processes, institutions and actors. Anti-Trafficking Rev. 2015;(no.5) [Google Scholar]

- Piper N., Rosewarne S., Withers M. Migrant precarity in Asia: ‘networks of labour activism’ for a rights-based governance of migration, development and change. Int. Inst. Soc. Stud. 2017;48(5):1089–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan B., Kjellstrom T., Atar D., et al. Heat stress impacts on cardiac mortality in Nepali migrant workers in Qatar. Cardiology. 2019;143:37–48. doi: 10.1159/000500853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prayas. Situational analysis of construction labour market in Ahmedabad city. Prayas Centre for Labor Research and Action, 2009. http://www.clra.in/files/documents/Construction-Workers-study-2009.pdf.

- Puar J. Precarity talk: A virtual roundtable with Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Bojana Cvejić, Isabell Lorey, Jasbir Puar, and Ana Vujanović. TDR (1988-) 2012;56(4):163–177. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23362779 [Google Scholar]

- Rogaly B., et al. Seasonal migration and welfare/illfare in eastern India: a social analysis. J. Developmental Med. 2002;5(23):89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Mir R. The Afghan refugees of Lajpat Nagar: the boundaries between them and Delhi. Crossings. 2020;11:201–216. 10.1386/cjmc_00025_1. [Google Scholar]

- Samaddhar R. In: Borders of an Epidemic – Covid-19 and Migrant Workers. Samaddhar R., editor. Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group; Calcutta: 2020. Border of an Epidemic - Introduction; pp. 1–24. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Saraswati L., Sarna A., Rob U., Puri M., Singh R., Sharma V., Kundu A. South–south mobility: economic and health vulnerabilities of Bangladeshi and Nepalese migrants to India. Area Develop. Policy. 2016;1:2 doi: 10.1080/23792949.2016.1194723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker B. A global perspective of migration and occupational health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010;53(4):329–337. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senarath U., Wickramage K., Peiris S. Health issues affecting female internal migrant workers: a systematic review. J. Coll. Comm. Physicians Sri Lanka. 2016;21(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- Shah A., Lerche J. Migration and the invisible economies of care: production, social reproduction and seasonal migrant labour in India. Trans. Inst. British Geographers. 2020;45(4):719–734. [Google Scholar]

- Shanker R., Raghavan P. The Invisible Crisis: refugees and COVID-19 in India. Int. J.Refugee Law. 2020;32(4) doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eeab011. pp 680 684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma J., Sharma A., Kapilashrami A. COVID-19 and the precarity of low-income migrant workers in Indian cities. Soc. Cult. South Asia. 2021;7(1):48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shome R. The Long and deadly road: the covid pandemic and Indian migrants. Cult. Stud. 2021;35(2–3):319–335. doi: 10.1080/09502386.2021.1898033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddaiah A., Kant S., Haldar P., Rai S.K., Misra P. Maternal health care access among migrant women labourers in the selected brick kilns of district Faridabad, Haryana: mixed method study on equity and access. Int. J. Equity Health. 2018;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0886-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkhada P., van Teijlingen E., Gurung M., et al. A survey of health problems of Nepalese female migrants workers in the Middle-East and Malaysia. BMC Int. Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(4) doi: 10.1186/s12914-018-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinap G., Wawrzynski J., Chowdhury N., et al. A disease burden analysis of garment factory workers in Bangladesh: proposal for annual health screening. Int. Health. 2019;11(1):42–51. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihy064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweileh W.M., Wickramage K., Pottie K., et al. Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000–2016) BMC Public Health. 2018;18:777. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5689-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwary G., Gangopadhyay P.K. A review on the occupational health and social security of unorganized workers in the construction industry. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011;15(1):18–24. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.83003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR, CARE and ActionAid, An Intersectional Analysis of Gender amongst Rohingya Refugees and Host Communities in Cox's Bazar, An Inter-Agency Research Report, Bangladesh, 2020. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/gender_and_intersectionality_analysis_report_2020-19th_october_2020.pdf. (accessed 30 March 2021).

- UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, COVID-19 and Migration for Work in South Asia: private Sector Responsibilities. UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2021.

- Viajar V.D.Q. Dimensions of precarity of migrant domestic workers: Constraints and spaces in labor organizing in Malaysia. Labor and Globalization. 2017:197. [Google Scholar]

- Virupaksha H.G., et al. Migration and mental health: an interface. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2014;5(2):233–239. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.136141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramage K., Mosca D. Can migration health assessments become a mechanism for global public health good? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2014;11:9954–9963. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111009954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramage K., Gostin L.O., Friedman E., Prakongsai P., et al. Missing: where are the migrants in pandemic preparedness plans? Health Hum. Rights. 2018;20(1):251–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . World Bank; Washington D.C: 2020. Towards Safer and More Productive Migration for South Asia. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah, A. Atkuri, R., Jesani, A. 2020. Health professionals must call out the detrimental impact .on health of India's new citizenship laws, BMJ Opinion. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/01/14/health-professionals-must-call-out-the-detrimental-impact-on-health-of-indias-new-citizenship-laws/.

- Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS medicine. 2011;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]