Abstract

Background

Migration is a present and pressing global phenomenon, as climate change and political instability continue to rise, more populations will be forced to relocate. Efficient strategies must be in place to aid the transition of vulnerable populations - such as children - and strategic interventions designed based on an understanding of their particular needs and risks.

Aim of the review

This article reviewed recent research regarding the mental health of migrant children identifying a wide array of common characteristics to their emotional and behavioral responses following a migration, and compiled an extensive list of protective and risk factors. 48 studies were selected from Proquest, WOS, SCOPUS, and Pubpsych published between 2015 and 2022 covering studies of children around the world.

Findings

The migration-related factors that most negatively impacted children's mental health were experiences such as discrimination, loss of access to governmental and educational resources, premigration trauma, loss of community, cultural distance and acculturation, the burden on the family unit, and socioeconomic difficulties. Thus, with the right interventions and policy changes, it is possible to make migration a non-traumatic experience in order to avoid the common emergence of depressive symptoms, PTSS (post-traumatic stress symptoms), anxiety, and other mental health issues. Supporting the family unit's transition, encouraging peer connections, and directing government aid to expedite resources upon arrival will serve as protective factors for children while they integrate into their new environment.

Keywords: Migration, Children, Depression, Review, Mental health

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Reports by the UN estimate there are 31 million child migrants globally - 13 million refugees, 936,000 asylum-seekers, and 17 million internally forcibly displaced (IOM, 2019). Most of them are traveling through the migration corridors that tend to form towards the nearest perceived stable nations, each trajectory has its own set of characteristics and challenges which must be taken into account when comparing their experiences. In addition, there have been significant changes that occurred to the nature of migrations after economic and political events throughout the last century, such as, the end of WWII, the fall of the Berlin wall, the signing of NAFTA (1993) (de Haas et al., 2019), 9/11 (MPI, 2022), the 2008 economic crisis (de Haas et al., 2019), and the COVID-19 pandemic Chakraborty & Maity (2020). Thus, as immigration increases due to political conflict, economic volatility, and climate change, countries will need to update their policies to handle large influxes of some of the most vulnerable groups of people, particularly children. The necessity for established resources and efficient introductory systems was made apparent with the recent emigration from Ukraine, European countries responded quickly through practical aid and streamlined visas (UNHCR, 2022), however, more remains to be done.

1.2. Factors in studying migration

Determining the premigratory factors included in an analysis of the impact of a migration is crucial to a granular understanding of the postmigratory emotional response and the acculturation process. The first dimension to consider is the diversity of characteristics pertaining to geographic movements, such as if the journey is international (northward, southward, etc) or internal, which determines the type of arrival experience at a destination country, such as the legal process (visas, border crossings, citizenship, access to government-funded resources), the cultural distance to the place of origin (process, ease, and speed of acculturation), language barriers, etc. Considering all types of migratory movements was important to this review in order to obtain a panoramic picture of the experiences, obstacles, and potential trauma children may face when migrating, and in so adding to the review by Belhadj, Koglin, & Petermann (2015) which was limited to migrations into North America.

A second important dimension is the person's motivation for choosing to migrate - the reason for leaving their home. This dimension speaks to what their hopes in migrating are, their future outlook, sense of self-efficacy, premigratory traumas, etc. Here, personal motivation was considered under two main umbrellas - economic and political. A third scenario is that of refugees, where the person had less choice in the matter and was forced to move against their will, such as in fleeing political conflict or natural disaster. However, the question of motivation applies differently to children, who are rarely consulted or included in the decision if they are accompanying a parent or guardian.

Finally, demographic factors such as age, gender, religion, and ethnicity are usually considered in studying adult migrations, but there are a few more to add such as family composition and education in the case of children's migrations.

1.3. Migration and psychology

For all migrants, regardless of age, migration is lived as a complex loss triggering a grief period (Wang et al., 2015). The overlap of migration and psychological research in children is the main focus of this review. Acculturation is not just an internal emotional process, but it is affected by systemic obstacles, environmental factors, and family dynamics that add to the psychological impact of leaving home. Lack of stability, safety, acceptance, warmth, and connection to community at such pivotal ages are considered as potential experiences for emotional wounds that can lead to feelings of depression, anxiety, or other mental health issues.

Further research is needed to ascertain the impact of migration on children, if they are in greater danger of trauma than their adult counterparts due to the vulnerability of the development process, or if, as some have suggested, the plasticity of their age may provide increased resilience Fuligni & Tsai (2015). Future lines of study should include comparative studies on the impact of migration on adults and children and long-term studies of how children who have experienced the phenomenon of migration develop into adults. For now, the purpose of this article is to identify the characteristics of children's emotional responses after migrating by reviewing current studies in order to specify symptomatology common to said population, and to identify the protective and risk factors that play a role in recovering from emotional distress by addressing the following questions:

-

•

What are children's emotional and behavioral symptomatology after having migrated to a new city or country?

-

•

What are current migratory characteristics contributing as risk or protective factors to affect children's response?

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

This article follows the methodology set out by Arksey and O'Malley in the International Journal of Social Research Methodology (2005). The systematic search began by consulting the following databases: ProQuest, WOS, SCOPUS, and PubPsych, conducted by A.S.A. and independently checked by both J.S.R. and S.R.P. Studies were compiled into Mendeley for screening.

Relevant studies were located through the use of the following keywords:

· Sample population age groups: [child* OR adolesc* OR youth* OR boy OR girl OR infan* OR childhood]

AND

· Migratory experience: [migration* OR national OR international OR immigration OR mobility OR migratory OR foreign-born OR first-generation OR resettl* OR relocat*]

AND

· Symptomatology: [identity OR anxiety OR stress* OR behavioral OR depressi* OR emotion* OR mental OR health OR behavior OR psychopathology OR psychiatric OR affective OR disorder OR conduct OR delinquency OR substance OR violence or well-being OR post-traumatic-stress OR suicide OR self-esteem OR resilience OR psychosomatic OR loneliness]

2.2. Data extraction

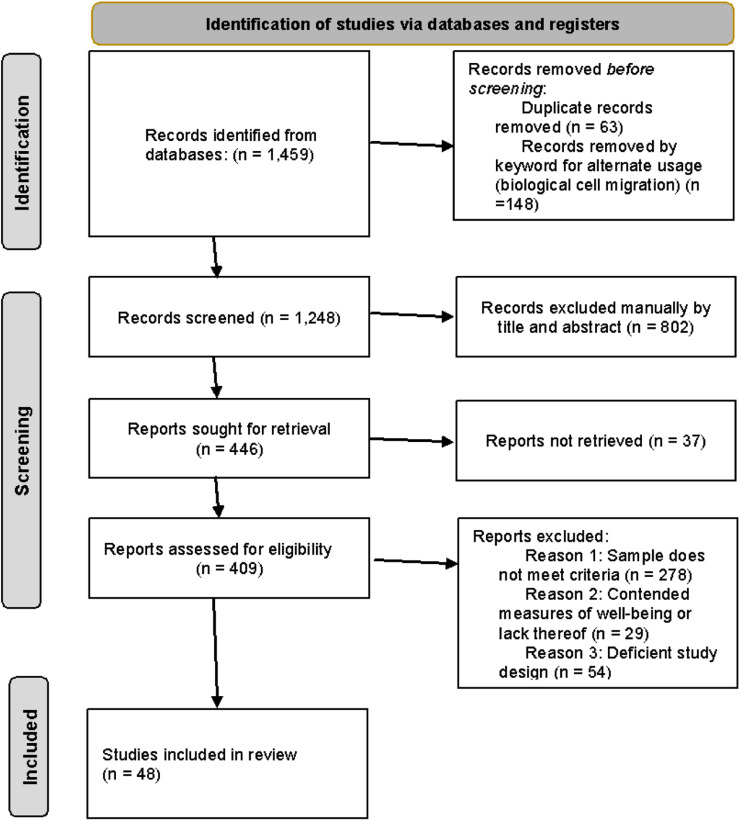

The search process resulted in a total of 1459 articles. 63 articles were immediately eliminated because they were duplicates. The term migration is used in a different context in the field of biology of which 148 articles were removed. Next, a screening was conducted through a preliminary reading of the title and abstract which resulted in the elimination of 802 more articles due to differing subject matter or because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. After a full-text review, 361 articles were considered ineligible according to the criteria detailed in Table 1. The studies' quality was assessed through the use of the Q-SSP tool Protogerou & Hagger (2020), and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for qualitative studies. The studies that did not meet a minimum quality rating of 3 out of 4 were eliminated.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

Sample Characteristics |

· Children ages 0 to 25 at the time of the study (aligning with age brackets of previous research into refugee children (McEwen et al., 2022) and the age at which a person is neurologically and developmentally adult). · Children who migrated alone or accompanied by family. · Children who migrated nationally (rural to urban) or internationally. · Refugees and asylum-seekers. |

· Children who migrated under the context of international adoption. · Children moving within the same city or otherwise called “residential mobility”. · Second and third-generation migrants, or children of a migratory or ethnic background who did not migrate. · “Left behind” children. |

| Article Characteristics | · Articles in English were included. · Articles published from 2015 to 2022. |

· Articles published before 2015 because they do not represent current characteristics of migration. |

| Study Characteristics | · Studies with only migrant populations. · Studies comparing migrant populations to their local peers. · Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. · Studies with unbalanced gender distributions were included due to the recurring lack of female participants in refugee samples. |

· Studies that mixed first- and second-generation migrants in their sample into one group. · Studies with unreliable, biased, or flawed designs. · Studies with unclear age brackets, such as studies that collected population samples by college-level or school grade. · Studies about psychological interventions’ results. · Case studies. |

| Measures of Mental Health | ·Studies focusing on postmigratory emotional problems such as loneliness, hopelessness, stress, etc. ·Studies focusing on postmigratory behavioral problems such as substance abuse, suicide, violence, risky sexual behavior, etc. · Studies focusing on postmigratory mental health diagnoses such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, PTSD, etc. · Studies focusing on cognitive well-being such as self-esteem, resilience, mindfulness, etc. |

· Studies that used children's academic achievement as a measure of emotional well-being. · Studies using cannabis use as an indicator of psychological problems. · Studies using BMI as a wellness measure. |

48 studies were organized in a table in Microsoft Excel according to the sample's characteristics (age, country of origin, country of destination,), the study's characteristics (sample size and measures used) and the results (protective and risk factors, comparisons to local peers, mental health diagnoses, and acculturation levels). Data was extracted by identifying the symptomatology analyzed and the premigratory or postmigratory factors impacting or mitigating the children's responses to their specific type of migration. Studies were compared according to their objectives, their migratory movement, and the symptomatology to extract similarities or contradictions. Finally, the most recurring themes were highlighted such as issues of discrimination, peer relationships, family relationships, legal obstacles, and depressive symptoms, which were the most common response identified Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram, (Page et al., 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Objectives of reviewed studies

The studies covered different objectives regarding migrant children's mental health (seen in Table 3):

-

1

Postmigratory protective factors: to identify the child's personal internal (psychological and emotional) and external resources (relationships with caregivers, peers, teachers, parents) to cope with the transition,

-

2

Premigratory risk factors: to identify the impact of premigratory conditions and the circumstances of their migration (forced migration, violence, loss of family members) that affect their adaptation process,

-

3

Postmigratory risk factors: to identify environmental factors that affect children's acculturation (discrimination, socioeconomic status, legal status, access to medical, educational, and mental resources, language barriers, exposure to illegal activity),

-

4

Group comparisons: to compare migrants’ mental health to refugees or their local peers,

-

5

Symptomatology: to identify emotional, behavioral, or psychological responses in children at their country of destination after migrating.

Table 3.

Result summary table.

| Author & Year | Location | Migrant Origins | Sample | Ages | Measure | Risk Factors | Protective Factors | Mental/ Emotional/ Behavioral symptoms | Relevant Findings | Objectives (listed 3.1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Akkaya-Kalayci, et al. (2015) | Turkey | Turkey | 165 internal migrants, 45 locals | 6–18 | Clinical Records Emergency Psychiatric Clinic | Cultural distance | Suicide, depression | 21.05% of patients born in Istanbul. 78.95% migrated internally. 32.06% from Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia, areas with highest cultural differences to Istanbul. | 4 | |

| 2 | Akkaya-Kalayci, et al. (2017) | Austria | Turkey, Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia | 800 locals, 293 migrants | 4–18 | Clinical Records Emergency Psychiatric Clinic | Cultural distance, language barrier, family conflict, acculturation stress | Medical resources | Suicide, depression, acute stress disorder, behavioral problems | Significant differences found in reason for referral by nationality (p<.001). Austrian children referred for acute stress disorder (20.9%), Turkish patients for attempted suicide (23.1%), and Serbian/ Croatian/ Bosnian children for acute stress disorder (19.0%). | 4, 5 |

| 3 | Axelsson et al. (2020) | Sweden | Various | 1267,938 locals; 6133 unaccompanied migrant minors; 54,326 accompanied migrant minors | 18.33 mean | National databases | Limited access to social system | Unaccompanied minor status | ADHD, depression, PTSD, OCD, anxiety | Unaccompanied children had a higher likelihood and quicker average time to seek psychiatric help than accompanied migrants (p<.001), as well as outpatient care (p<.001). Unaccompanied refugee children have closer ties to the healthcare system and less barriers to access care. | 1, 4 |

| 4 | Beiser, Puente-Duran, & Hou (2015) | Canada | Various | 2074 migrants | 11–13 | Self-report questionnaires | Cultural distance, resettlement stress, low parental mental health, SES | Social skills, warm parenting, resilience | Stress, depression | Larger cultural differences between country of origin and destination correlate with more negative emotions than smaller cultural distances (p<.001). Migrations with larger cultural distances characterized by higher resettlement stress (p<.001). Social competence skills and warm parenting mitigated some of the adverse effects. No significant differences between two subgroups found in depression scores. | 3 |

| 5 | Bianchi et al. (2021) | Italy | Various | 201 locals, 48 migrants | 9–18 | Global Negative Self-Evaluation Scale, Classmate Social Isolation Questionnaire, Academic Achievement | School dropout intention, low school achievement, low SES | Social support, group belonging | Self-esteem | Peer acceptance at school was a protective factor to reduce school dropout intention (p=.02) and negative self-esteem (p<.001) among migrants. | 1 |

| 6 | Blázquez et al. (2015) | Spain | Various | 43 migrants | 14.59 mean | Psychiatric assessment | Parental separation, family breakdown, sexual abuse, physical abuse, verbal abuse, premigration trauma | Psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, affective disorder, depression, eating disorders, conduct disorders, PTSD | Migrants from Latin America displayed primarily diagnoses in psychotic disorders (27.6%), depressive disorder (20.7%), and bipolar disorder (17.3%). Migrants from Africa were primarily diagnoses with psychotic disorders (40%). Migrants from Asia were primarily diagnosed with psychotic disorders (50%) and anxiety disorders (50%). | 5 | |

| 7 | Buchanan et al. (2018) | Australia | Various | 106 refugees, 223 migrants | 13–21 | Self-report questionnaires | Premigratory trauma, low parental education levels, school adjustment, discrimination, language barriers, forced migration | Peer community, positive future outlook | Low self-esteem | Pre-migratory environment and migratory motivation differentiated groups of migrants and refugees significantly. Refugee children reported lower levels of self-esteem (p=.001) and school adjustment (p<.001) than migrant children. | 2 |

| 8 | Cameron, Frydenberg, & Jackson (2018) | Australia | Various | 38 refugees, 19 migrants, 20 locals | 12–18 | Self-report questionnaires | Discrimination, peer conflict, premigratory trauma | Group belonging, peer support, religious beliefs | Stress, nonproductive coping strategies | Refugees were more likely to refer to others (peers, professionals, and deities) to cope with stressful situations like interpersonal conflict and discrimination than other groups (p=.001). Previous exposure to stressful life events was significantly associated with nonproductive coping strategies in interpersonal conflict (p<.001). | 2, 4 |

| 9 | Caqueo-Urízar et al. (2021) | Chile | Latin America | 292 migrants | 8–18 | Child and Adolescent Assessment System, Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-12), Acculturation Stress Source Scale (FEAC) | Acculturation stress | Resilience, integration, interpersonal skills | Stress | Integration and social competence have significant associations with resilience (p <0.001) and indirect associations with acculturation stress (p=.009). | 1 |

| 10 | Celik et al. (2019) | Turkey | Syria | 125 migrants, 168 locals | 7–10 | Demographic data form, Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory, Koppitz Draw-A-Person Test | Premigratory trauma, witnessing warfare | Anxiety | Migrants had higher anxiety scores than locals (p=.001). Locals displayed higher levels of shyness (p<.005). | 4, 5 | |

| 11 | Cleary et al. (2018) | USA | Latin America | 101 migrants | 12–17 | Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for Children (TESI-C), PHQ-9-Spanish, Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS), Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) (all in Spanish) | Premigratory trauma, postmigratory trauma | PTSD, depression, anxiety | 44% experienced at least one traumatic event, 23% experienced two or more traumatic events. 59% experienced the traumatic event in their country of origin, 20% experienced a traumatic event during migration, 18% experienced it in the USA. 39% experienced a natural disaster, 34% experienced an injury/accident, 21% witnessed violence. There were significant correlations between experiencing traumatic events during and postmigration and PTSD (p<.001) and depression (p<.01). There was a significant correlation between premigratory trauma and anxiety (p<.01). | 2, 3 | |

| 12 | Cotter et al. (2019) | Ireland | Various | 8110 locals, 458 migrants | 9–13 | Open access data of GUI (2006–7 study “Growing up in Ireland”) | Early life stressors, parents in prison, death of close family member, language barrier | Psychopathology, ADHD | No significant difference in psychopathology reports. Migrant children experienced significantly more stressful life events than non-migrant counterparts (p<.01). A greater proportion of migrant children showed hyperactivity problems in childhood (p =0.04). | 3, 4 | |

| 13 | Duinhof et al. (2020) | Netherlands | Various | 5283 locals, 1054 migrants | 11–16 | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Dutch Health and Behavior in School Aged Children (HBSC) data | Family affluence, peer conflict | Behavioral problems, ADHD | Migrant children reported lower family affluence than locals (p<.001) more conduct problems (p<.001), more peer relationship problems (p<.001), less hyperactivity-inattention problems (p<.001). | 3, 4 | |

| 14 | Elsayed et al. (2019) | Canada | Syria | 103 refugees | 5–13 | Self-report questionnaires, individual interviews with children and mothers | Daily hassles, premigratory stressors, parent life stressors | Family routines | Emotional regulation, stress | Children who engaged in more family routines after migrating scored better in anger regulation to stressors and daily hassles (p<.05). No significant difference in sadness regulation, authors suggest a larger impact of pre-migratory factors than their post-migratory experiences. | 1, 5 |

| 15 | Fang, Sun, & Yuen (2016) | China | China | 301 internal migrants | 10–18 | Self-report questionnaires | Economic stress, access to resources, school resources | Friendships, school satisfaction, self-esteem, hope | Positive future outlook, acculturation | Hope for the future and teacher support were significant mediators to school satisfaction (p<.001 and p<.001). Positive academic outcomes were most influenced by positive family relationships (p<.01). | 1 |

| 16 | Gao et al. (2015) | China | China | 808 migrants in private school, 211 migrants in public school, 447 locals in public school | 9–15 | Self-report questionnaires | Parental education level, SES, access to resources, school resources | Educational resources, family satisfaction, school satisfaction | Externalizing and internalizing problems, depression | Migrant children attending private schools reported significantly more externalizing problems (p<.001), more internalizing problems (p<.001), lower family satisfaction (p<.001), lower friend satisfaction (p<.001), lower school satisfaction (p<.001), lower environment satisfaction (p<.001), and lower self-satisfaction (p<.001). Migrant children attending public schools and local children did not differ in scoring for items: externalizing problems, friend satisfaction, and school satisfaction. | 3, 4 |

| 17 | Grasser et al. (2021) | USA | Iraq | 48 refugees | 6–17 | Self-report questionnaires, UCLA PTSD RI, SCARED | Forced migration | Post-traumatic stress, anxiety | 38% scored possible anxiety score. 87.5% scored positive for separation anxiety. 9.5% had positive PTSD scores. 37.5% scored possible panic/somatic symptoms. No significant correlation between symptoms and age. | 5 | |

| 18 | Jia & Liu (2017) | China | China | 854 rural migrants | 13.34 mean | Perceived Discrimination Scale for Chinese Migrant Adolescents, Classmate Climate Inventory, Child Behavior Checklist-Youth-Self-Report | Perceived discrimination, access to resources, school resources | Social support | Antisocial behavior | Perceived discrimination for rural migrants was positively correlated with antisocial behavior (p<.001) and negatively correlated with teacher support (p<.001) and classmate support (p<.001). Antisocial behavior was negatively associated with teacher support (p<.001) and classmate support (p<.001). | 3, 5 |

| 19 | Jore, Oppedal & Biele (2020) | Norway | Various | 557 unaccompanied refugees | <18 | Self-report questionnaire, Revised Social anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Youth Culture Competence Scale (YCSS) | Premigratory trauma, discrimination | Cultural competence | Social anxiety, depression | 79% reported at least 1 premigratory traumatic event and 50.9% reported experiencing 3 or more. There was no significant relation between premigration traumatic events and social anxiety. Social anxiety was significantly related to discrimination (p<.001) and depression (p<.001). | 2, 3 |

| 20 | Keles et al. (2017) | Norway | Various | 229 refugees | 13–18 | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for adolescents, YCC Hassles Battery | Acculturation hassles, unaccompanied minor, economic hardship, peer conflict, achievement conflict, perceived discrimination, ethnic identity crisis, premigratory trauma | Length of stay | Depression | Significant relation between depressive symptoms and acculturation hassles remaining strong over each of the three observations over time (p<.001 each time). Relationship between depressive symptoms and premigratory war-related trauma decreased each time participants were observed (p<.001, p.<01, and then insignificant). | 2 |

| 21 | Keles et al. (2018) | Norway | Various | 918 refugees | 13–18 | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for adolescents, YCC Hassles Battery, Host Culture Competence and Heritage Culture Competence | Acculturation hassles, premigratory trauma, unaccompanied minors | Host culture competence, heritage culture competence, length of stay | Depression | Participants were classified as resilient (142), vulnerable (148), clinical (212), and healthy (362) (50 as inconclusive) according to scores in a combination of measures. 58% of participants were in healthy and resilient clusters. Healthy group participants had stayed significantly longer in Norway (p=.021) and had less acculturation hassle experiences (p=.030). | 3 |

| 22 | Khamis (2019) | Lebanon, Jordan | Syria | 1000 refugees | 7–18 | Interviews: Trauma Exposure Scale, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF), Kidcope, Family Environment Scale, School Environment Scale (SES) | Premigratory traumatic events | time in host country, family relationships, school environments | PTSD, emotion dysregulation | 45.6% of the refugees developed PTSD with excessive risk for comorbidity with emotion dysregulation. PTSD was associated with the host country, 3.31 times more children resettled in Lebanon tested positive for PTSD than those in Jordan (p<.0001). The prevalence of PTSD diagnoses was lower in children who had spent more time in their host country. | 2, 4, 5 |

| 23 | Kumi-Yeboah & Smith (2017) | USA | Ghana | 60 migrants | 16–20 | Semi-structured individual interviews and focus group interviews | Discrimination, language barrier, educational system | Social support, resilience | Acculturation | Migrant students reported positive attitudes toward school, holding high aspirations, and being optimistic about the future. Participants reported the importance of teachers’ and counselors’ support in helping them adjust to new academic demands and cultural environment to improve their academic work. Children reported tense relations with peers, specifically with African American classmates, which contributed to cultural challenges and minimal social integration. | 1 |

| 24 | Liu & Zhao (2016) | China | China | 798 internal migrants | 12–17 | Self-report questionnaire, Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale | Perceived discrimination, parental education levels, access to resources, school resources | Group identity and belonging | Low self-esteem, low levels of life satisfaction | Psychological well-being measured through two variables (life satisfaction and self-esteem) and found they correlated negatively with perceived discrimination (p<.001 for both) and positively with “group identity affirmation and belonging” (p<.001 and p<.01 respectively). The length of residence in the city was positively associated with life satisfaction and self-esteem (p<.001 for both), and negatively with perceived discrimination (p<.01). Children in private schools perceived more discrimination (p<.001) and had lower levels of self-esteem (p<.001) and life satisfaction (p<.001) than children in public schools. | 1, 3 |

| 25 | Lo et al. (2018) | China | China | 741 urban locals, 497 rural migrants | 13–14 | Self-report questionnaires | Conflictual parental relationship, conflict with peers, economic strain, educational strain, access to resources, school resources | Social support | Emotional distress, depression, delinquent behavior | Chinese students’ delinquency level was low in both groups. No statistically significant differences between the two groups were found in measures of either minor or serious delinquency. Rural migrants generated significantly higher measures for community disorganization (p=.04), mistreatment by teachers (p=.01), violent victimization (p=.03), educational strain (p=.04), and emotional distress (p<.01). They also had weaker parent-child relationships (p<.01) and knew a greater number of delinquent peers (p<.01). | 3, 4 |

| 26 | Longobardi, Veronesi, & Prino (2017) | Italy | Northern Africa | 19 migrants | 16–17 | Strengths and difficulties questionnaire, Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children, ISPCAN Child abuse screening tool, Child and Youth Resilience Measure | Conflict with peers, premigratory trauma, postmigratory trauma, unaccompanied minors | Resilience, religious beliefs, social skills | Post-traumatic stress, anxiety, dissociation, depression | Participants had average scores in questionnaires regarding conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, prosocial behavior, anger, sexual concerns, resilience, and experiences of abuse. Scores in peer problems, post-traumatic stress, dissociation, anxiety, and depression differed from mean scores of the average Italian population by more than 1 SD. | 1, 5 |

| 27 | Martínez García & Martín López (2015) | Spain | Latin America | 19 migrants | 16–19 | Semi-structured interviews | Conflict with peers, discrimination, low SES, conflict with parents, gang participation | Feelings of lack of safety | Young male members of violent gangs reported leaving their countries between 8 and 14 years old. None were consulted about the decision to emigrate; some were against it. The children reported difficulties integrating into the new culture due to doubts about emigration, loss of emotional reference points in country of origin, and weak relations with relatives living in Spain. Participants reported one or both of two reasons for joining violent groups: the group would facilitate positive relationships and/or it would increase their sense of safety. | 2, 3 | |

| 28 | McEwen, Alisic, Jobson (2022) | Australia | Various | 85 refugees | 16–25 | PMLD, Everyday Discrimination Scale, SLE, MIAS, RATS, HSCL-37A, CYRM-R | Discrimination, male gender | Resilience | PTSD, internalizing behavior | 80% of participants scored high in PTSD symptoms. 55.29% scored high on internalizing symptoms. 84.42% scored low resilience. Males had more experiences than females of discrimination (p=.02). Males reported significantly lower resilience than females (p=.03). | 5, 3 |

| 29 | Müller et al. (2019) | Germany | Various | 98 refugees | 16.28 mean | Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS), Hopkins Symptom Checklist-37 (HSCL-37A), Everyday Resources and Stressors Scale | Witnessing violence, experiencing war, premigratory trauma, migratory trauma | PTSD | All children had experienced at least 1 traumatic event. Children reported on average 8.82 traumatic experiences. The most common traumatic event (96.6%) was a dangerous migration such as traveling in a small, crowded boat. 75% witnessed low level violence, 78.6% witnessed medium level of violence, 76.5% witnessed high level of violence. 76.5% experienced hunger and thirst for several days. 64.3% experienced war. 85.7% experienced interpersonal violence (such as within their family). 56.1% scored in clinical levels of PTSS, and 29.6% fulfilled criteria for PTSD. | 2, 5 | |

| 30 | Ni et al. (2016) | China | China | 1306 rural migrants | 9–19 | Self-report questionnaire, Bicultural Identity Integration Scale (BIIS- 1), Index of Sojourner Social Support, Subjective Happiness Scale | SES, access to resources, school resources | Social support, identity integration | Well-being | Identity integration significantly related to social support (p<.01) and subjective well-being (p<.01). Social support positively associated with subjective well-being (p<.01). Migrant children attending public schools reported higher identity integration compared to children attending private schools (p<.01), and higher scores in subjective well-being (p<.01). | 1 |

| 31 | O'Donoghue et al. (2021) | Australia | Various | 277 migrants, 853 locals | 15–24 | Clinical psychosis diagnosis | Geographic area, cultural distance, drug use, premigratory trauma, asylum seeking | Psychotic disorder, schizophrenia | 23.1% of migrants received a schizophrenia diagnosis compared to only 15.5% of locals. Migrants (15.5%) reported less methamphetamine abuse than locals (30.8%). Migrants from North Africa and the Middle East presented an increased risk for developing psychotic disorder (p=.06). Migrants from New Zealand showed no increased risk in being diagnosed with psychotic disorder. | 4, 5 | |

| 32 | Öztürk & Güleç Keskin (2021) | Turkey | Syria, Iraq | 200 migrants | 6–17 | CDI, Demographic information form | Forced migration | Depression | 35% lost their relatives before and during migration. 35.5% stated that they missed their country. Participant scores did not indicate levels of depression. There was a significant relation between high depression scores and death of their father (p=.011), mother who was the primary breadwinner (p=.003), poor academic scores (p=.000), poor relationships with peers (p=.000), loss of a relative (p=.000), low satisfaction with new environment (p=.000), low adaptation (p=.000). | 2, 4, 5 | |

| 33 | Pfeiffer et al. (2019) | Germany | Various | 419 refugees | 8–21 | Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) | Premigratory trauma, unaccompanied migration | PTSD, psychosomatic symptoms | 90.7% of participants were male. Children had experienced an average of 7.47 traumatic events. The average CATS score was above the clinical cut-off. PTSD symptoms such as nightmares, psychological reactivity, and concentration problems were highly connected to exposure to traumatic events. | 2, 3, 5 | |

| 34 | Posselt et al. (2015) | Australia | Various | 30 refugees | 12–25 | Semi-structured interviews | Premigratory trauma, family conflict, acculturation, language barrier, educational strain, employment obstacles, access to resources | Maladaptive coping strategies, self-medication | Participants reported barriers in finding employment due to differences in language, culture, and education. Refugees reported high availability of substances, which led to ease of use as maladaptive coping strategies and self-medication. Reported changes in intra-family roles, father could no longer provide, and children had to work. Reported experiences of discrimination. | 3 | |

| 35 | Salas-Wright et al. (2016) | USA | Various | 23,334 locals; 1723 migrants | 12–17 | National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) | Exposure to drugs, alcohol, delinquency, age of arrival, family income | School engagement, cohesive parental relationships, length of stay | Externalizing behavior | Migrants who had been in the US for five or more years were less likely to attack to injure (p<.05), to sell drugs (p<.05), and to use substances (p<.05). Those who arrived age 12 or older were less likely to get into serious fights (p<.05), to attack to injure (p<.05), to sell drugs (p<.05), and to use illicit drugs (p<.05). Those who arrived before turning 12 were less likely to attack to injure (p<.05), to sell drugs (p<.05), to carry a handgun (p<.05), to bring on alcohol or drugs (p<.05). Migrants who had lived in the US for five years or more had lower levels of parental conflict (p<.05), more school engagement (p<.05), and higher levels of disapproval of marijuana use (p<.05). | 3, 4 |

| 36 | Samara et al. (2020) | UK | Various | 149 refugees, 120 locals | 6–16 | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Self-report questionnaire | Premigratory trauma, bullying | Friendships | PTSD, behavioral problems, self-esteem, psychosomatic | Young refugee children reported more peer problems (p<.001), functional impairment (p<.001), physical illness (p<.01), and psychosomatic problems (p<.01) compared to locals. But older refugee children had lower self-esteem compared to the younger children (p<.05). The differences were explained by friendship quality and number of friends. | 4 |

| 37 | Sánchez-Teruel et al. (2020) | Spain | Africa | 326 unaccompanied males | 18–23 | 14 Item Resilience Scale (RS-14), Hope Herth Index, General Self-efficacy Scale GSE, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (in Spanish) | Unaccompanied minors | Employment | Resilience, self-efficacy, depression, anxiety | Having a job was the best predictor of high resilience (p<.01) and high self-efficacy (p<.01). Hope was related to interconnectedness (p<.01) and social support (p<.01). High resilience was related to hope (p<.05), and negatively correlated to anxiety (p<.01) and depression (p<.05). | 1, 3 |

| 38 | Schapiro et al. (2018) | USA | Latin America | 56 migrants | 15.5 mean | Health screening questionnaire | Premigratory trauma, caseworker language barriers, death of family member, lack of social support, unaccompanied minors | Early health and psychological screening, family | Adjustment disorder, depressive mood, anxiety | 28 (50%) reported academics as an asset to adapting, 15 (26.8%) mentioned sports, 14 (25%) pointed to good family relationships. 10 (17.9%) thought their good personality or feeling happy was their strong point. 39 children (69.9%) stated they were living with parents and 17 (30.1%) with older siblings or other relatives because they had migrated alone. | 1 |

| 39 | Schlaudt, Suarez-Morales, & Black (2021) | USA | Latin America | 89 migrants | 10–16 | Revised Children's Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS), Acculturative Stress Inventory for Children (ASIC), Children's Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS), Children's Acceptance and Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) | Negative automatic thoughts, language barriers, acculturative stress, SES, educational resources | Mindfulness | Anxiety | There was a relation between automatic thoughts and anxiety (p<.0001), introducing mindfulness did not have a significant moderating effect. Mindfulness reduced the relationship of acculturative stress to automatic thoughts (p<.0001), but it increased the connection of acculturative stress with anxiety. Acculturative stress and anxiety were significantly related (p=.0005). Mindfulness moderated the relationship (p=.048). | 1, 3 |

| 40 | Sleijpen et al. (2016) | Netherlands | Northern Africa | 111 migrants | 12–17 | Posttraumatic Growth Inventory for Children, Children's Impact of Event Scale, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, The Life Orientation Test, and the Satisfaction with Life Scale. | Traumatic events, negative future outlook, length of stay | Social support, perceived posttraumatic growth | Life satisfaction | Participants experienced on average 8 potentially traumatic events. They reported high levels of PTSD. Perceived posttraumatic growth and PTSD symptoms were not found to be related. Perceived posttraumatic growth was positively associated with dispositional optimism (p<.01) and social support (p<.01). Dispositional optimism (p<.05) and social support (p<.05) positively predicted perceived posttraumatic growth. Perceived posttraumatic growth was positively related to satisfaction with life (p<.01). Length of stay had a negative relationship with satisfaction with life (p<.01). | 3, 5 |

| 41 | Spaas et al. (2022) | Belgium, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Norway | Various | 883 refugees, 483 non-refugee migrants | 11–24 | CRIES-8, SDQ (2001), questionnaire designed for study about overall well-being, family separation, and questions extracted from "Daily Stressors Scale for Young Refugees", questions extracted from Brief PErceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire (PEDQ) | family separation, perceived discrimination, female gender, older age, daily material stress, refugee experience | PTSD, internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior, stress | Refugees were more likely than non-refugee migrants to score within clinical range of PTSS (p=.001). 44.7% of refugees scored in the clinical range and 32.4% of non-refugees. 7.6% of refugees and 10.3% scored high in behavioral difficulties. 8.9% of refugees and 10.5% of non-refugees scored high on emotional problems, 6.2% of refugees and 8.2% of non-refugees scored high on conduct problems, 10.3 % of refugees and 11.3% of non-refugees scored high on peer problems, and 3.3% of refugees and 5.1% of non-refugees scored low on prosocial behavior with no significant differences between groups. 5.5% of refugees and 8.8% of non-refugees scored in hyperactivity, non-refugee migrants were more likely to score within a high range (p=.025). Perceived discrimination was associated with PTSS, internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior for all participants (p<.001 for all). | 2, 3, 4 | |

| 42 | Stark et al. (2022) | USA | Various | 205 locals, 152 migrants | 15.65 mean | Survey | Stressful life events | Hope, school belonging, resilience | Suicidal ideation | Suicide ideation and resilience were negatively correlated (p<.001). Children with greater hope (p<.001) and school belonging (p<.001) reported higher resilience, while lower levels of school belonging correlated with higher levels of suicide ideation (p=.009). More stressful life events were associated with suicide ideation (p<.001), while fewer were correlated with resilience (p=.003). Being born outside the United States was associated with suicide ideation (p<.015), with this finding driven by those from the Middle East and North Africa region, who faced significantly increased risk of suicide ideation (p=.036). | 3, 4, 5 |

| 43 | Stevens et al. (2015) | Europe, North America | Various | 4053 migrants; 42,941 locals | 11–15 | Self-report questionnaire | Conflict with peers | Family affluence | Violent behavior, psychosomatic symptoms, life satisfaction | More emotional and behavioral problems were found in migrant sample than locals, as well as experiences of bullying. Migrant male children reported higher levels of physical fighting than local peers (p<.01). Differences in indicators of emotional and behavioral problems between migrant and native children did not vary significantly by receiving country. Lower levels of life satisfaction were found in migrants than locals (p<.01). | 4 |

| 44 | Tello et al. (2017) | USA | Central America | 16 refugees | 10–23 | Counseling sessions | Unaccompanied minors, premigratory trauma, traumatic migration, delayed postmigration resettlement, discrimination | Early psychological intervention, religious beliefs, social support | Feelings of powerlessness, PTSD, depression, emotional and behavioral problems | The study identified three themes about what led participants to leave home: to help the family financially, to escape gang violence and death, and feelings of powerlessness. Participants described feeling loss of control and fleeing to take hold of their future. Present concerns included fear that discrimination would impact their ability to stay in the U.S. or cause them to be deported. Participants considered these concerns about their future to be directly related to a loss of future hope. | 2 |

| 45 | Titzmann & Jugert (2017) | Germany | Various | 480 recent migrants, 483 longtime migrants | 11–19 | Self-report questionnaires | Discrimination | Language proficiency, academic achievement, social support, parental education, length of stay | Self-efficacy | Newcomers reported lower family financial security (p<.01), less social support (p<.01), less language use (p<.01), and more discrimination hassles (p<.01) than experienced migrants. Authors conclude that the transition to another country is related to a drop in self-efficacy, but with a subsequent recovery period. | 3 |

| 46 | Yayan & Düken (2019) | Turkey | Syria | 738 refugees | 7–18 | CPTS‐RI, CDI, STAIC‐T (in Arabic) | Parental illiteracy, socioeconomic status, poor physical health, parental death | State support | PTSD, depression, anxiety | Boys had significantly higher depression scores than girls (p<.005). Children without health problems had lower depression scores than children suffering from respiratory disease or anemia (p<.001). Anxiety, depression, and PTSD scores were higher in children who had lost a parent (p<.001), as well as for those whose mothers or fathers were illiterate (p<.001), and for those who had lower socioeconomic status (p<.001). There was a highly significant relationship between anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress (p<.01). | 2, 3, 5 |

| 47 | Ye et al. (2016) | China | China | 384 migrants in public school, 337 migrants in private school | 10.22 mean | Self-report questionnaires | Access to government resources, school resources, peer conflict, discrimination | Resilience, social support | Depression, well-being | Migrant children who could only enroll in the private school reported more verbal victimization (p=.01), more property victimization (p=.00), more depressive symptoms (p=.00), less social resources (p=.00), and less personal assets (capacity to cope with difficulties) (p=.00) than migrant children in public school. Peer victimization was positively associated with depressive symptoms (p<.001) and negatively associated with resilience (p<.001). Depressive symptoms and resilience were negatively correlated (p<.001). | 3, 5 |

| 48 | Ying et al. (2019) | China | China | 437 internal migrants | 10.87 mean | Self-report questionnaires | Access to resources, school resources, low SES, loneliness | Parental warmth, parent communication | Loneliness, depression | Economic pressure was positively correlated with loneliness (p<.01) and negatively correlated with parental warmth (p<.01). Loneliness was negatively correlated with parental warmth (p<.01). Maternal education level was positively correlated with parental warmth (p<.05) and mutual understanding of communication (p<.05), and negatively correlated with economic pressure (p<.05) and loneliness (p<.05). | 3 |

3.2. Study Characteristics

The 48 studies reviewed here included different types of geographical movements: 39 were international migrations, and nine were national migrations [1, 15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 30, 47, 48] Table 2.

Table 2.

Geographic focus of studies.

| Area of Emigration | Area of Immigration | Significant Geographical Pairings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 23, 26, 37, 40 | North America | 4, 11, 14, 17, 23, 35, 38, 39, 42, 43, 44 | China (rural) – China (urban) | 15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 30, 47, 48 |

| Eastern Europe | 1, 2 | Western Europe | 2, 3, 5, 6, 12, 13, 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, 29, 33, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43, 45 | South America - USA | 11, 38, 39, 44 |

| Asia | 15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 30, 47, 48 | Asia | 15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 30, 47, 48 | Africa – Western Europe | 26, 37, 40 |

| South America | 9, 11, 27, 38, 39, 44 | Eastern Europe | 1, 10, 22, 32, 46 | Syria - Turkey | 10, 32, 46 |

| Middle East | 10, 14, 17, 22, 32, 46 | Australia | 7, 8, 28, 31, 34 | ||

| Various (Studies with more than 5 countries of origin) | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 19, 20, 21, 28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 41, 42, 43, 45 | South America | 9 | ||

In terms of the family composition of the population samples, most covered migrations as a family unit, only a few studies involved only unaccompanied minors [3, 19, 20, 21, 26, 33, 37, 38, 44]. Most studies managed to include samples with both boys and girls despite difficulties in accessing female migrant participants, in studies of unaccompanied minors, only two studies had solely male participants [27, 37]. Often genders were not equally distributed, but the studies included all required clear gender distributions. For example, one study had 90.7% males in their sample which was accounted for in the results [33]. One study in particular to highlight, included the option for children to select the option “nonbinary” as their gender in its survey [42]. It was unclear if gender differentiated the emotional response of migrant children, some studies found no difference between genders [4, 7, 8, 12, 21, 30, 40, 48], and yet others found significant differences [1, 2, 14, 15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 28, 41]. Studies identified girls as better at emotional regulation [14], had more hope for their future [15], and displayed more resilience [28]; however, other studies found they were more likely to be patients in clinics treated for attempting suicide [1, 2], and they scored lower in life satisfaction [24] although study found the opposite [16]. Boys were found to engage in antisocial behavior more often [18], had higher depression scores [46], externalizing behavior [16], delinquent behavior [25], and violent behavior [43]. Boys also reported more perceived discrimination than girls [28].

Most studies found no significant variance in symptomatology according to participants’ ages [4, 7, 8, 12, 14, 21, 40, 48]. There was some evidence that the older children were when they migrated the more they showed more externalizing behavior, lower family satisfaction, and lower school satisfaction than children [16, 35], and that life satisfaction was negatively related to age [24].

3.3. Summary of the study results

3.4. Postmigratory environmental factors and acculturation

A factor that became evident across studies was the impact of limited access to resources that migrants suffer upon arrival, varying by destination and each country's particular requirements and policies. Although many migrants choose their destination seeking the safety and economic opportunities a country has to offer, they do not enjoy the same benefits as locals, encountering obstacles such as legal issues, complicated visa paperwork, detention centers, language barriers, and restricted job opportunities (see Table 4). These bureaucratic obstacles impact their acculturation process and consequently their mental health, with many migrants reporting lower life satisfaction, stress, and depression than locals. Fear of deportation or complications to their visa applications can keep them from seeking help. Language barriers impact children's education and parents’ access to jobs. Migrants may also struggle with difficult relationships with caseworkers, difficulty navigating or accessing government health systems, and lack of funds were common hassles and stressors. Sometimes children had to step in to help their parents by translating documents or working to support the family, thus they were subjected to parentification. Overall migrant children experienced more bullying in school [43] and in general, significantly more traumatic events than local children (p<.01) [12].

Table 4.

Symptomatology and response studied related to migration.

| Emotional | Behavioral | Cognitive | Psychological | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hope | 15, 37, 42, 44 | Suicide (ideation or attempt) | 1, 2, 42 | Self-esteem | 5, 7, 15, 24, 36 | Depression | 1, 2, 3 4, 6, 11, 16, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 32, 37, 38, 39, 44, 46, 47, 48 |

| Loneliness | 48 | Violence | 35, 43 | Resilience | 4, 9, 23, 26, 28, 37, 42, 47 | Anxiety | 3, 6, 10, 11, 17, 19, 26, 37, 38, 39, 46 |

| Feelings of Powerlessness | 44 | Externalizing behavior | 13, 16, 35, 41 | Identity integration | 20, 24, 30 | PTSD | 3, 6, 11, 17, 22, 26, 28, 29, 33, 36, 40, 41, 44, 46 |

| Feelings of group belonging | 5, 8, 24, 42 | Internalizing behavior | 16, 28, 41 | Self-Efficacy | 37, 45 | ADHD | 3,12, 13, 26, 41 |

| Satisfaction | 15, 16, 24, 32, 40, 43 | Drug use | 31, 34, 35 | Mindfulness | 39 | OCD | 3 |

| Feeling lack of safety | 27 | Conduct problems | 6, 13 | Acculturation | 9, 15, 20, 21, 23, 34, 39 | Psychosomatic symptoms | 33, 36, 43 |

| Stress | 2, 4, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15, 20, 21, 39, 41, 42, 45 | Self-medicating | 34 | Adjustment Disorder | 7, 38 | ||

| Anger | 14, 26 | Delinquency | 25, 35 | Dissociation | 26 | ||

| Antisocial behavior | 18 | Psychotic disorder | 6, 31 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 6 | ||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 6 | ||||||

| Eating disorder | 6 | ||||||

| Conduct disorder | 6 | ||||||

| Stress disorders | 2 | ||||||

A particular example of the limitations placed upon migrants through public policies emerged in many studies in China - the HuKou household registration status, where restrictions on rural to urban migrations try to keep families from moving to the city, they must get permission to do so. Due to economic necessities, many migrate despite the difficulties they encounter accessing public education, job opportunities, unemployment aid, maternity benefits, food services, healthcare, retirement funds, and other public subsidies mirroring a status similar to illegal migration. Migrant children's sense of belonging in the city was highly related to feelings of well-being at school, and thus the level of hope for the future, happiness scores, and academic achievement. But most of them could not enter public schools and were left to attend illegal, unfunded, and unregulated private schools with other migrant children [16, 24, 30, 47]. In some cases, wealth could mitigate some of these obstacles, sidestepping some restrictions, setting wealthy migrant families apart with significantly fewer mental health problems and higher life satisfaction.

Thus, the studies that compared child migrant populations to local peers often highlighted increased negative emotional and psychological symptoms. In terms of emotional symptoms, migrants were found to experience more depression [1, 3], anxiety [10], lower life satisfaction [43], lower self-esteem [5], and distress [25]. Behavioral symptoms also emerged from the studies, migrant children had higher rates of suicide [1, 2, 42], hyperactivity [12], conduct problems [13, 43], and violent behavior [43]. The rates of official psychological diagnoses was also higher, with migrant children testing more often for schizophrenia and psychotic disorder [31].

3.5. Symptomatology and the mental health of migrant children

Migrant children were consistently found to be a significantly emotionally vulnerable population, with symptoms such as PTSD, OCD, suicide attempts, anxiety, emotional distress, and dissociation. The children reported feelings of powerlessness, low self-esteem, behavioral problems, feeling unsafe, low levels of life satisfaction, and loneliness. But, as can be seen from Table 4, depression and depressive symptoms were the most common and significant throughout most studies. Although, one study found levels of depression to be less related to premigratory trauma rather than postmigratory experiences [14], many other studies reported that cultural distance was positively correlated to levels of depression [1, 2, 4, 6, 31], the larger the cultural adjustment, the more emotionally affected the children were, as cultural negotiation was accompanied by stressful events and daily hassles such as learning a new language, adapting to new academic structures, discrimination, figuring out how to find a job, religious differences, etc.

3.6. Postmigratory risk factors and social support

Because migration is characterized by significant and permanent changes to their nuclear family, neighborhood, school peers, extended family, teachers, and religious communities it constitutes a loss of children's emotional reference points. The new configurations of social support at their destination impact their acculturation, their hope for the future, and current life satisfaction as well as their capacity to deal with the daily hassles and stressful events the process of migration can incur [20]. Migrants frequently showed high aspirations for their future and a positive outlook at arrival [7, 15, 23, 44]. However, over time a negative outlook could replace it when faced with isolation, loneliness, lack of acceptance from new communities, and discrimination, which compounding with premigratory issues or trauma could lead to depressive symptoms [4, 27, 20, 40]. On the other hand, children who experienced social support in the form of family unity, positive peer relationships, and supportive teachers had a more positive future outlook, more ambition, higher levels of satisfaction, and an increase in academic achievement [20, 21, 24].

The family environment, children's primary source of social support, is inevitably destabilized after a migration due to family separation, death of a family member, parental trauma, and changes to their socioeconomic status because a parent is unable to find work [6, 7, 12, 14, 16, 24, 25, 27, 35, 38, 45, 46, 48]. Migration circumstances bring new struggles and conflicts for families, studies found migrant children had reported more negative parent-child relationships than local children [25]. Conflictive relationships with parents were a risk factor for their mental health and acculturation [1, 25, 27, 34]. Whereas, parental warmth, cohesive family routines, and good communication with parents served as protective factors [4, 14, 16, 35, 38, 48].

Discrimination, racism, bullying, and xenophobia were the most common experiences for most migrants and were thus the focus of many studies (see Table 5). In schools, bullying was an obstacle to integration, several studies highlighted how feeling excluded at school was detrimental to children's mental health, whereas feelings of group belonging correlated to better acculturation and well-being [5, 8, 24, 42]. Specifically, cultural discrimination significantly related to depression and suicidal behavior [1, 2, 20], antisocial behavior [18], lower self-esteem [5, 7, 24, 36], and lower life satisfaction [24, 43]. Discrimination is part of migrants' experiences because of their ethnic differences and cultural distance - skin color, religion, accent, language, clothing, academic background, and/or lack of social connections. These differences tended to be larger and more marked in more culturally distant migrations [1, 2, 4, 31]. Protective factors such as appealing to help from teachers, peers, parents, or religious beliefs emerged as children's coping strategies and responses to discrimination [8, 15, 23, 25, 26, 44].

Table 5.

Findings types.

| Protective Factors | Risk Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| School engagement | 5, 7, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, 24, 30, 35, 38, 42, 47 | Substance Use | 31, 34, 35 |

| Access to government and educational resources | 16, 24, 30, 47 | Cultural distance | 1, 2, 4, 6 |

| Parental warmth and positive family relationships | 4, 14, 15, 22, 38, 48 | Educational strain | 25, 32 |

| Teacher support | 15, 18, 23, 25 | Daily hassles | 14, 20, 21, 45 |

| Religious beliefs | 8, 26, 44 | Peer conflict or bullying | 13, 20, 23, 25, 27, 32, 36, 41, 43, 47 |

| Relationships with case workers | 8, 38 | Experiencing or witnessing violence | 10, 11, 44 |

| Hopeful future outlook | 15, 37, 42, 44 | Experiencing natural disaster | 11 |

| Unaccompanied migration | 3 | Detention centers | 7, 8, 28, 34 |

| Social competence skills and friendships | 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 36 | Unaccompanied migration | 19, 20, 21, 26, 33, 37, 38, 41, 44 |

| Length of time since arrival | 20, 22, 35, 45 | Stressful life events (SLEs) | 11, 12, 19, 22, 29, 33, 40, 42 |

| Mindfulness exercises | 39 | Refugee status | 7, 8, 14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 28, 29, 33, 34, 36, 41, 44, 46 |

| Acculturation stress | 2, 9, 15, 20, 21, 23, 34, 39 | ||

| Discrimination | 7, 8, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24, 27, 28, 34, 41, 44, 45, 47 | ||

| Low socioeconomic status | 13, 43, 44, 45, 46 | ||

| Conflict with parents | 16, 27, 34, 35 | ||

| Death of family member | 12, 29, 32, 38, 44, 46 | ||

| Language barrier | 2, 7, 12, 23, 34, 38, 39, 45 | ||

4. Discussion

This review aimed to identify symptomatology in children responding to migration, as well as the protective and risk factors characterizing the circumstances around different types of migrations. This review found a significant pattern between the difficult experiences of premigration and postmigration that primarily manifested as symptoms of depression, regardless of the migratory movement, age, gender, or cultures involved. One study reviewing psychiatric hospital records found internal migrants made up the majority of their patients (78.95%) receiving emergency services (Akkaya-Kalayci, et al., 2015). The convergence of several negative experiences characteristic of most migrations (Sandstrom & Huerta, 2013) and underdeveloped coping skills at vulnerable developmental stages (Fuligni & Tsai, 2015), make children susceptible to experiencing mental health problems after migrating, specifically in light of the safety nets migration removes and the social support lost, as well as cultural and political threats added depending on how open a country is to welcoming migrants. Migration is a relevant and present phenomenon, an essential one, but it is not an issue or a problem in and of itself, rather it is the circumstances surrounding it that are more likely to compound into mental health problems.

Policy obstacles can look like procedural hoops many migrants have to jump through in visa applications that routinely change, unclear processes, or denying access to paperwork that provides access to essential resources (medical, educational, psychological, occupational, and nutritional). Children can face these legal hurdles for years, spending time in detention centers (Buchanan et al., 2018), they may have to navigate this without the help of a lawyer or translating important paperwork for their parents. Unsurprisingly, this can result in feelings of uncertainty, despair, depression, hopelessness, decreasing hope and future outlook, unable to move backward or forward (Ball & Moselle, 2016).

Several articles included in this review detail a particular type of national migration in China closely mirroring illegal international migrations due to restrictive internal movement policies (Hukou). These studies can help examine the acculturation struggles created by a lack of access to resources specifically without cultural factors intermingling into the risk factors children face. Children whose parents moved to the city without the approved paperwork displayed more depressive symptoms than those who had the right permits, in large part due to the inability to access government-funded education (Ye et al., 2016). Interestingly, internal migrants still experience significant discrimination and the multitude of psychological difficulties it produces (Jia & Liu, 2017). Internal migrations should not be discarded as easier than international migrations, any type of environmental change for a child is accompanied by many difficulties.

Racism and bullying are dangerously common experiences for migrant children; it is a most aggressive form of social rejection (Verkuyten & Thijs, 2006). Prolonged feelings of rejection were psychologically harmful to children, whereas developing friendships with peers, social support, and a sense of group belonging were among the most important protective factors (Bianchi et al., 2021; Liu & Zhao, 2016). Discrimination does not only come in the form of verbal violence but can also escalate to physical violence. Children who migrated to find safety encounter a new environment that does not meet their expectations and they must learn to navigate new dangers. This can lead to a loss of hope, a negative future outlook, or looking for safety in dangerous connections such as joining a gang (Martínez García & Martín López, 2015; Tello et al., 2017). In addition to behavioral responses such as turning to delinquency or violence, a significant emotional response to perceived discrimination was high post-traumatic stress symptoms (Spaas et al., 2022). Peer victimization was negatively correlated to resilience and positively associated with depressive symptoms (Ye et al., 2016), some children experienced discrimination even from teachers (Lo et al., 2018). Designing interventions for this particular risk factor might be the most difficult; widespread cultural change takes time, in the meantime migrants can be warned and prepared about how to deal with these negative experiences, education in schools may help reduce bullying. Providing children with the tools to process racism and bullying is important to protect their mental health.

Although relationships to their new environment, such as with peers or teachers, are important, their primary source of support and possibly the primary protective factor if healthy, is the child's family. In most instances, migrating accompanied by their parents helped children negotiate cultural differences, find emotional support, overcome academic hurdles, and have access to better economic opportunities. In a few studies, however, the opposite results emerged - parental depression, difficulty with language acquisition, barriers to finding economically sustainable and legal jobs, or conflictive home environments produced further stress for the child [3]. The family may become a burden to the child and a risk factor to their acculturation and mental well-being, in cases where they are the sole source of financial support for their family unit (Ponizovsky Bergelson, Kurmanb, & Roer-Strier, 2015). Culturally conservative parents could also present as an impediment to children's integration if the parent demanded the child reject the host culture for fear they might lose their traditions or religion (Oznobishin & Kurman, 2016), lack of acculturation and incapacity to negotiate acculturation hassles are detrimental to children's mental health (Berry, 2001; Keles et al., 2018). Children can develop a unique multicultural perspective and identity that helps them navigate the increasingly globalized world (Ball & Moselle, 2016), and allowing for an integrative acculturation process will benefit them, not only on a psychological level but could also give them an edge later in the job market. Parental warmth and good communication can be the foundation from which the child explores and discovers the new culture. Attachment theory expert advice has focused so far on urging governments to protect the family unit (Juang et al., 2018). There are different characteristics of parental support and the relationship to the child which can give contradictory results and require further study. Parental warmth was a protective factor in the face of economic pressure and loneliness (Ying et al., 2019). But illegal migrant children reported weaker parent-child relationships (Lo et al., 2018) and lower family satisfaction than non-migrant children or legal migrant children (Gao et al., 2015). Concerning access to resources, in Sweden, unaccompanied minors got more help from the government and had quicker access to mental health resources than accompanied minors (Axelsson et al., 2020). A third scenario where children can only migrate with one parent also creates unique emotional responses, for example, where children may lose one parent during the migration. Öztürk & Güleç Keskin (2021) found depression symptoms correlated with having only their mother and their mother having to work.

Further research is required to understand all the factors that go into family migrations. The family unit inevitably suffers under the conditions of migrations around the world, so the authors suggest schools can be a focal point for aid directed at children. To target aid to parents, another centralized location must be designed where parents can receive language support, health services, help finding a job, assistance applying for visas, help navigating other government systems, and legal aid. Migration services should be prepared to offer psychological aid in a manner that does not affect their visa applications, available throughout the process of adjustment, not just at arrival.

Interventions need to be designed and ready for implementation before migratory corridors begin to form, for them to be effective and efficient. Climate change, food shortage, and rising political conflicts will not decrease over the next few years, it is a certainty that we will see a marked increase in migrations of entire families and large communities (IOM, 2019). Recent UN data shows more migrants are fleeing natural disasters than war (UN, 2022), and yet 7405,590 Ukrainian refugees were recorded across Europe (UNHCR, 2022). 2 million children exited Ukraine and 2.5 million were internally displaced (UNICEF, 2022). It is important to follow up on the well-being of both, internal migrations can be just as impacting, particularly considering the premigration trauma they share. There are inherent difficulties in studying the experience of certain migrant samples, such as illegal migrants or unaccompanied minor girls, but further research is important to protect these particularly vulnerable populations. In addition, more longitudinal studies are needed to understand the long-term factors that impact acculturation. China already, recognizing the need to reevaluate its practices for the sake of its young internal migrants, has begun loosening its approach to its Hukou system (Wang, 2020).

Conflict with peers, witnessing or experiencing violence, leaving home, adjusting to a new culture, changing schools, a liminal legal status, isolation, separation from family (physical, emotional, or cultural), change or strain to the relationship with parents, parental depression, trauma, financial instability, and racial or cultural discrimination are risk factors and are all, unfortunately, characteristic of most types of migration. These produce a period of destabilization that children go through upon arrival, but over time they can learn to handle the changes, the acculturation hassles, and show an increase in self-efficacy (Titzmann & Jugert, 2017). The longer migrants had been in a country the more they reported more positive mental conditions and overall well-being (Keles et al., 2018; Salas-Wright et al., 2016). A migration does not have to add up to complex trauma with the right social support and access to resources.

4.1. Limitations

In order to provide a fully panoramic view into the current state of the factors affecting migrant children, it was important to consider a truly global perspective, so no geographical limitations were set for this review. However, this meant it was necessary to limit the time bracket from which articles were selected in order to keep the results pertinent to the aim of the study. A review of a more historical perspective should go back further to capture past trends, but this was beyond the scope of the present analysis. Time parameters were thus set from 2015 to 2022. This still resulted in a large collection of results which were reviewed by authors manually, which opens the results to human error and limits the article language that can be reviewed, here only articles in English were included, whereas migration being a global phenomenon should be studied in all languages. In terms of the studies included, the availability of results from certain geographical areas were lacking. Migration from a developing nation to a developing nation abounds, however there is a lack of funding for studies in said countries and thus there were more results about immigrants in Europe and North America than in South America, Africa, or South-East Asia despite large migration corridors that have been forming in these areas in the last ten years.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review examined articles reporting on studies into children's mental health by identifying emotional and behavioral symptomatology as a response to migration. The authors gathered this literature in order to provide an overview of available evidence in the intersecting fields of child psychology and migration, to identify knowledge gaps in said research and identify key characteristics and factors related to the fields in hopes that this summary can offer guidance into future lines of study into what is yet unknown of the effects of migration and the responses children have to the experience in order to create more efficient interventions, design helpful policies that direct aid effectively and quickly to those who need it most urgently. As the policies in most countries currently stand, legal obstacles currently serve as risk factors to children's acculturation and subsequently their mental health. Cultural attitudes towards migrants also impact children's sense of safety. However, multiple protective factors were found, particularly of the positive effect social support can have to mitigate those negative experiences.

Further research is needed to follow the development of migrant children through long-term studies to track their acculturation, specifically those who have received psychological diagnoses, as well as those who receive aid to measure and improve interventions. More studies focused on the experience of migrant girls are necessary to illustrate their particular experience, or what factors may be hindering their migration to safer countries.

The authors declare no known competing personal or financial interests that may have influenced the work reported. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Akkaya-Kalayci T., Popow C., Waldhör T., Winkler D., Özlü-Erkilic Z. Psychiatric emergencies of minors with and without migration background. Neuropsychiatrie. 2017;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s40211-016-0213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkaya-Kalayci T., Popow C., Winkler D., Bingöl R.H., Demir T., Özlü Z. The impact of migration and culture on suicide attempts of children and adolescents living in Istanbul. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2015;19(1):32–39. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2014.961929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Article: Two Decades after 9/11, National Security.. | migrationpolicy.org. (n.d.). Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/two-decades-after-sept-11-immigration-national-security.

- Axelsson L., Bäärnhielm S., Dalman C., Hollander A.-C. Differences in psychiatric care utilisation among unaccompanied refugee minors, accompanied migrant minors, and Swedish-born minors. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020;55(11):1449–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01883-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J., Moselle S. Forced migrant youth's identity development and agency in resettlement decision-making: liminal life on the Myanmar-Thailand border. Migration, Mobility Displacement. 2016;2(2):110–125. doi: 10.18357/mmd22201616157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M., Puente-Duran S., Hou F. Cultural distance and emotional problems among immigrant and refugee youth in Canada: Findings from the New Canadian Child and Youth Study (NCCYS) Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015;49:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belhadj Kouider E., Koglin U., Petermann F. Emotional and behavioral problems in migrant children and adolescents in American countries: a systematic review. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2015;17(4):1240–1258. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. A psychology of immigration. J. Soc. Issues. 2001;57(3):615–631. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi D., Cavicchiolo E., Lucidi F., Manganelli S., Girelli L., Chirico A., Alivernini F. School dropout intention and self-esteem in immigrant and native students living in poverty: the protective role of peer acceptance at school. School Mental Health. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09410-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez A., Castro-Fornieles J., Baeza I., Morer A., Martínez E., Lázaro L. Differences in psychopathology between immigrant and native adolescents admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2015;17(6):1715–1722. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan Z.E., Abu-Rayya H.M., Kashima E., Paxton S.J., Sam D.L. Perceived discrimination, language proficiencies, and adaptation: Comparisons between refugee and non-refugee immigrant youth in Australia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2018;63:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron G., Frydenberg E., Jackson A. How young refugees cope with conflict in culturally and linguistically diverse urban schools. Australian Psychologist. 2018;53(2):171–180. doi: 10.1111/ap.12245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caqueo-Urízar A., Urzúa A., Escobar-Soler C., Flores J., Mena-Chamorro P., Villalonga-Olives E. Effects of resilience and acculturation stress on integration and social competence of migrant children and adolescents in Northern Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(4):2156. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik R., Altay N., Yurttutan S., Toruner E.K. Emotional indicators and anxiety levels of immigrant children who have been exposed to warfare. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019;32(2):51–60. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty I., Maity P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment, and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary S.D., Snead R., Dietz-Chavez D., Rivera I., Edberg M.C. Immigrant trauma and mental health outcomes among latino youth. J. Immigrant Minority Health. 2018;20(5):1053–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0673-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter S., Healy C., Ni Cathain D., Williams P., Clarke M., Cannon M. Psychopathology and early life stress in migrant youths: an analysis of the ‘Growing up in Ireland’ study. Irish J. Psychol. Med. 2019;36(3):177–185. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2018.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]